Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Computerized Tool To Manage Dental Anxiety: A Randomized Clinical Trial

Computerized Tool To Manage Dental Anxiety: A Randomized Clinical Trial

Uploaded by

Sung Soon ChangOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Computerized Tool To Manage Dental Anxiety: A Randomized Clinical Trial

Computerized Tool To Manage Dental Anxiety: A Randomized Clinical Trial

Uploaded by

Sung Soon ChangCopyright:

Available Formats

vol. XX • issue X • suppl no.

X JDR Clinical Research Supplement

Clinical Trials

Computerized Tool to Manage Dental

Anxiety: A Randomized Clinical Trial

M. Tellez1*, C.M. Potter2, D.G. Kinner2, D. Jensen2, E. Waldron2, R.G. Heimberg2, S. Myers Virtue1,

H. Zhao3, and A.I. Ismail1

Abstract: Anxiety regarding dental tal anxiety, fear, avoidance, and over- injection fear has been evaluated (the

and physical health is a common and all severity of dental phobia in favor CARL Program; Coldwell et al. 1998;

potentially distressing problem, for both of immediate treatment at the follow- Heaton et al. 2013), the current study

patients and health care providers. up assessment. Of the patients who met tests the efficacy of a computerized

Anxiety has been identified as a bar- diagnostic criteria for phobia at base- treatment for a broader range of dental

rier to regular dental visits and as an line, fewer patients in the immediate concerns.

important target for enhancement of treatment group continued to meet cri- Cognitive-behavioral interventions have

oral health–related quality of life. The teria for dental phobia at follow-up as garnered strong support in the treatment

study aimed to develop and evaluate compared with the wait-list group. A of dental anxiety. A meta-analysis of 38

a computerized cognitive-behavioral new computer-based tool seems to be studies focusing on cognitive-behavioral

therapy dental anxiety intervention efficacious in reducing dental anxi- therapy (CBT; Kvale et al. 2004) provides

that could be easily implemented in ety and fear/avoidance of dental pro- support for its efficacy in reducing

dental health care settings. A cognitive- cedures. Examination of its effective- dental anxiety among adults, even when

behavioral protocol based on psycho- ness when administered in dental administered in a limited number of brief

education, exposure to feared dental offices under less controlled condi- sessions (de Jongh et al. 1995; Thom

procedures, and cognitive restructur- tions is warranted (ClinicalTrials.gov et al. 2000; Jöhren et al. 2007; Haukebø

ing was developed. A randomized con- NCT02081365). et al. 2008; Wannemueller et al. 2011).

trolled trial was conducted (N = 151) A recent review that critically appraised

to test its efficacy. Consenting adult Key Words: dental phobia, dental fear, 22 randomized treatment trials aimed at

dental patients who met inclusion cri- cognitive behavioral therapy, dental reducing dental anxiety and avoidance in

teria (e.g., high dental anxiety) were attendance, efficacy, psychoeducation. adults (Gordon et al. 2013) also

randomized to 1 of 2 groups: imme- provided support for brief CBT

diate treatment (n = 74) or a wait-list Introduction interventions. Furthermore, a recent

control (n = 77). Analyses of covari- study demonstrated that a brief

ance based on intention-to-treat anal- Dental anxiety and specific phobia cognitive-behavioral intervention

yses were used to compare the 2 groups of dental procedures are prevalent performed by practicing dentists may

on dental anxiety, fear, avoidance, conditions that can result in substantial help fearful patients overcome their

and overall severity of dental phobia. distress and oral health impairment, fear and attend dental treatments

Baseline scores on these outcomes were affecting 10% to 20% of adults in various more regularly (Spindler et al. 2015).

entered into the analyses as covariates. US population groups (Locker et al. However, this intervention would

Groups were equivalent at baseline but 1999; Sohn and Ismail 2005; Tellez et al. require dentists to receive training in

differed at 1-mo follow-up. Both groups 2015). Few computer-aided interventions psychotherapy, be comfortable with

showed improvement in outcomes, tested in randomized clinical trials have performing the intervention, and have

but analyses of covariance demon- targeted dental anxiety. Although 1 the necessary tools to distinguish

strated significant differences in den- computer-based treatment for dental patients who may need more intensive

DOI: 10.1177/0022034515598134. 1Maurice H. Kornberg School of Dentistry, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 2Adult Anxiety Clinic of Temple, Department of

Psychology, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA; and 3School of Medicine, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA; *corresponding author, marisol@temple.edu

© International & American Associations for Dental Research

1S

Downloaded from jdr.sagepub.com at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIV FRESNO on July 27, 2015 For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

© International & American Associations for Dental Research

JDR Clinical Research Supplement Month XXXX

treatment elsewhere. Self-administered scheduled a dental treatment appointment scheduled. One month after the dental

treatments have also shown promise at the TUKSoD Faculty Practice Clinic, be appointment, participants were contacted

(Getka and Glass 1992), and the utility willing and able to give informed written by phone and asked to complete

of computerized or online interventions consent, participate responsibly in the follow-up assessments. If a participant

should be investigated. study protocol, meet criteria for high dental did not respond to study staff’s initial

This study aimed to develop and anxiety based on the MDAS, and endorse at contact attempt for the follow-up

evaluate a computerized CBT (C-CBT) least some oral health–related impairment assessment, research assistants continued

dental anxiety intervention that could be at the administration of a semistructured to call that participant weekly for 1 mo.

easily implemented in dental health care diagnostic interview. Participants received Participants who never responded to

settings. a $25 money order for completing the these requests for follow-up assessment

baseline questionnaires and telephone were considered lost to follow-up.

Materials and Methods interview and, if randomized to IT, for

Intervention

coming to their dental appointment

Design 1.5 h early to complete C-CBT. C-CBT consisted of a single-session 1-h

This was a single-center parallel Furthermore, all participants received an computerized intervention that assisted the

study with randomization to either an additional $25 payment for completing participant in building skills for managing

immediate treatment (IT) group or a their 1-mo follow-up questionnaires. The his or her dental anxiety. Participants

wait-list (WL) control group (allocation trial was stopped when recruitment targets completed C-CBT in a research office near

ratio:1:1). IT participants received C-CBT were reached. The study was approved the TUKSoD Faculty Practice Clinic on a

immediately preceding their scheduled by the Institutional Review Board at desktop computer with headphones. The

dental appointments. WL participants Temple University (protocol 13928). All intervention was delivered with the aid

attended their scheduled dental patients provided informed consent. The of a research assistant who was available

appointments without receiving C-CBT trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov to answer any questions and to assist

and were offered the same intervention (NCT02081365). participants with any aspect of C-CBT that

following all assessments. Data from the they found difficult.

Procedure

later treatment of WL patients are not C-CBT began with a psychoeducation

included in the present analyses. No Participation in the study involved module, which provided participants

changes were made to outcomes after completing 1) self-report questionnaires with basic education about the nature

commencement of the trial. online (or, for individuals without of dental anxiety. Next, patients were

Internet access, by telephone) and guided through a brief motivational

Sample Selection

2) a telephone diagnostic interview. interviewing exercise that helped them

The main hypothesis to be tested (H0: The research assistants at the clinic consider the benefits and drawbacks

There are no significant differences administered the randomization of of working on their dental anxiety.

between IT and WL) was subjected to participants (computer generated) and Thereafter, patients were guided through

power analysis. Assuming an average distribution of appointments. The file the exposure exercises, which included

change in Modified Dental Anxiety Scale was secured and restricted to the time of opportunities to practice coping with

(MDAS; Humphris et al. 1995) mean randomization. Randomization was done their dental anxiety. For the exposure

scores of 5 ± 10 in the IT group and no after baseline assessments for two-thirds exercises, patients were first asked

change in the WL group, with a power of the sample, while for one-third, it was to select their 3 most feared dental

of 0.80, an α level of 0.05, and a 2-tailed done before the assessments. procedures from a list of 6 (drilling and

test, we determined that 150 participants For practical and ethical reasons related having a cavity filled, cleaning, anesthetic

should be recruited. Recruitment was to the fact that participants were paying injection, root canal, oral X-ray, and tooth

carried out through the Faculty Practice for the dental treatment themselves and extraction) and rank them from least to

Clinic at the Temple University Kornberg the immediacy of treatment to which they most anxiety provoking. Patients then

School of Dentistry (TUKSoD) in 2014. All were allocated, we could not blind them watched video recordings of their top-3

new patients were identified through the to the outcome of the randomization. feared procedures, starting with the least

clinic’s electronic scheduling software and After randomization, each participant anxiety provoking and working up to

invited to participate before their dental was instructed to complete the self-report the most. For each selected procedure, 3

appointments if they met screening criteria assessments and the diagnostic interview videos were presented:

on the MDAS. There were no restrictions before coming in for their dental

on enrollment in terms of sex, economic appointment. IT participants were asked 1) The first video depicted a dentist

status, or ethnic group. to come in 1.5 h before their dental and/or hygienist conducting the

To be included, patients had to be appointment to complete C-CBT, whereas procedure with a patient and

between 18 and 70 y of age, be fluent those in the WL group simply attended provided a basic explanation of the

in spoken and written English, have their dental appointment as normally procedure. Animations of aspects of

2S

Downloaded from jdr.sagepub.com at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIV FRESNO on July 27, 2015 For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

© International & American Associations for Dental Research

vol. XX • issue X • suppl no. X JDR Clinical Research Supplement

the procedure that occur within the Humphris 2010); however, concerns Client Satisfaction Questionnaire

mouth were included, as were close- have been raised about this cutoff, as it The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire

ups of the dental tools employed. could exclude individuals who are very (CSQ-8; Larsen et al. 1979) is an 8-item

2) The second video presented similar or extremely anxious about only 1 of 2 self-report questionnaire designed to

visuals of the dental procedure but types of dental procedures (Dailey et al. assess client/patient satisfaction in

was more focused on the patient’s 2002). Therefore, in the present study, we health and human services. Each item is

emotional experience during the pro- considered patients who scored ≥19 on rated on a 4-point scale. Individual item

cedure. The voiceover provided basic the MDAS at baseline or endorsed at least scores are summed, resulting in a total

training in the nature and use of cog- 2 MDAS items ≥4 to have high dental score ranging from 8 to 32, with higher

nitive coping skills for dental anxiety. anxiety. This method has demonstrated scores indicating higher satisfaction. The

3) The third video was filmed from the superior sensitivity and specificity CSQ-8 has demonstrated high internal

perspective of the patient in the den- compared with the conventional scoring consistency in multiple clinical samples in

tal chair and provided more intensive procedure (Schulman et al. 2014). mental health settings (α = 0.92 to 0.93,

exposure to the feared dental proce- Larsen et al. 1979; split-half reliability

Secondary Measures: Semistructured

dure. Furthermore, the voiceover was Diagnostic Interview r = 0.82, Nguyen et al. 1983). The CSQ-8

a “dialogue” between the patient from was administered immediately after

the first 2 videos, who demonstrated The Anxiety Disorders Interview patients completed C-CBT to assess their

how to effectively cope with anxious Schedule (ADIS-IV; Brown et al. 1994) satisfaction with the program.

thoughts, and the participant, who is a semistructured diagnostic interview

Statistical Analyses

was led through the steps to develop designed to assess criteria per the fourth

coping thoughts for his or her own edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Differences between the groups on

dental anxiety. Manual of Mental Disorders (American baseline sociodemographic, clinical, and

Psychiatric Association 1994) for current psychological measures were examined

The intervention closed with a brief anxiety, depressive, somatoform, and using χ2 (Pearson) or Student’s t tests,

module providing additional motivational substance use disorders. The ADIS-IV has as appropriate (see Table 1). Moreover,

enhancement for attending future dental demonstrated good to excellent interrater differences on the variables listed above

appointments. Upon completing the reliability for the diagnosis of all assessed among completers and dropouts were

intervention, participants attended their disorders (k = 0.56 to 0.81; Brown et al. also explored, but no differences were

scheduled dental appointments and were 2001), with the exception of dysthymic found. Both per-protocol and intention-

encouraged to use the skills that they disorder (k = 0.31). All diagnosticians to-treat (ITT) analyses were then

learned from C-CBT to cope with any were advanced doctoral students or conducted, but only ITT analyses are

anxiety that they experienced during that research assistants who were trained reported in the Results section.

appointment. to strict reliability standards established To address our aim, analysis of

by Brown et al. (2001). For the present covariance (ANCOVA) was used to

Measures

investigation, only the specific phobia compare the 2 groups on primary and

Primary Measure: Dental Anxiety module of the ADIS-IV was administered secondary outcome measures. Baseline

Dental anxiety was measured with to assess the presence and severity of a scores on the outcome of interest were

the MDAS, a 5-item self-report measure current diagnosis of dental phobia. Details entered into the analyses as covariates,

that assesses fear of dental procedures, regarding the assessment and computation as was sex in the analysis of the MDAS

including drilling, scaling and polishing of each variable are provided below. scores, as sex differed between IT and

(i.e., cleaning), and local anesthetic WL groups at baseline (P = 0.032; Table

Dental Phobia

injections. Sample items include “If 1). Data were analyzed with SPSS 22.0

you went to your dentist for treatment Various aspects of dental phobia were (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

tomorrow, how would you feel?” and assessed using the specific phobia

Multiple Imputation

“If you were about to have your tooth module of the ADIS-IV. Interviewers

drilled, how would you feel?” Items assessed participants’ anxiety and Multiple imputation (MI) was used to

are rated on a 5-point Likert-type avoidance of dental procedures on scales handle missing follow-up data. There

scale ranging from 1 (not anxious) to that ranged from 0 (none) to 8 (very were 3 steps in the multiple-imputation

5 (extremely anxious). The MDAS has severe). They also rated patients’ overall procedure:

demonstrated good internal consistency distress and impairment due to their

(α = 0.89) and test-retest reliability (r = dental phobia symptoms and assigned a 1) The missing follow-up data were

0.82, interval unspecified; Humphris clinician’s severity rating that also ranged filled in 100 times to generate 100

et al. 1995). A total MDAS score ≥19 has from 0 (none) to 8 (very severe); a rating complete data sets.

been used as an indicator of high dental ≥4 indicated that the participant met 2) The 100 data sets were analyzed by

anxiety (Humphris et al. 1995; King & criteria for diagnosis of dental phobia. ANCOVAs with follow-up scores as

3S

Downloaded from jdr.sagepub.com at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIV FRESNO on July 27, 2015 For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

© International & American Associations for Dental Research

JDR Clinical Research Supplement Month XXXX

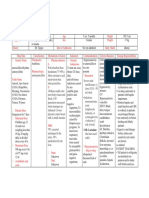

Table 1.

Baseline Differences by Condition

Immediate Treatment Wait-list Control Total P Valuea

Patient meets criteria for phobia 0.191

Yes 46 (62.2) 50 (64.9) 96 (63.6)

No 6 (8.1) 13 (16.9) 19 (12.6)

Missing 22 (29.7) 14 (18.2) 36 (23.8)

Race 0.533

White 20 (27.0) 18 (23.4) 38 (25.2)

Black or African American 34 (45.9) 44 (57.1) 78 (51.7)

Asian 2 (2.7) 2 (2.6) 4 (2.6)

Other 6 (8.1) 3 (3.9) 9 (6.0)

Missing 12 (16.2) 10 (13.0) 22 (14.6)

Ethnicity 0.891

Hispanic or Latino 5 (6.8) 5 (6.5) 10 (6.6)

Not Hispanic or Latino 53 (71.6) 58 (75.3) 111 (73.5)

Missing 16 (21.6) 14 (18.2) 30 (19.9)

Sex 0.032

Male 22 (29.7) 36 (46.8) 58 (38.4)

Female 52 (70.3) 41 (53.2) 93 (61.6)

Age, y, mean ± SD 44.7 ± 12.8 44.6 ± 13.6 44.7 ± 13.1 0.936

Values are presented as n (%) unless noted otherwise.

a

P from chi-square / Fisher’s exact test / t test. P values excluded missing data.

outcomes and with the treatment Of the remaining 105 participants who avoidance, and overall severity of dental

group as the independent variable completed the baseline assessment, 5 phobia in favor of IT at the follow-up

(IT vs WL), controlling for baseline WL and 2 IT participants were lost to assessment.

scores. follow-up. The total sample comprised

Primary Measure

3) The results from the 100 complete 151 adults seeking dental care at the

data sets were combined for the TUKSoD Faculty Practice Clinic (female, MDAS scores decreased from baseline

multiple-imputation inference (Rubin 61.6%; mean age, 44.7 ± 13.1 y; range, 18 (19.5 ± 0.34) to 1-mo follow-up (15.4

1987). to 70 y). The racial/ethnic composition of ± 0.74) for the IT group (see Table 2).

the sample was generally consistent with An ANCOVA with the ITT sample (N =

SAS PROC MI and PROC MIANALYZE that of north Philadelphia (U.S. Census 151) confirmed that the IT group had

were used for multiple-imputation Bureau 2010): approximately 51.7% of MDAS scores that were 2.2 points (95%

analysis using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., participants identified as black, 25.2% as confidence interval [95% CI]: 0.74, 3.55)

Cary, NC, USA). white/Caucasian, 2.6% as Asian or Pacific lower than those of the WL group (P =

Islander, and 6.0% as other. As noted 0.019) after controlling for the effect of

Results above, no significant differences between baseline MDAS scores and sex.

groups on baseline demographic or

Secondary Measures

Demographics clinical measures were found, except for

Of 961 new patients who received sex (see Table 1). ADIS-IV ratings of dental fear (baseline:

recruitment calls, 354 expressed interest 5.6 ± 0.17, follow-up: 3.8 ± 0.26),

Efficacy of C-CBT

and were assessed for eligibility. A total dental avoidance (baseline: 4.6 ± 0.31,

of 151 patients were eligible, consented Groups were equivalent at baseline but follow-up: 1.3 ± 0.31), and overall

to participate, and were randomized to differed at 1-mo follow-up. Both groups severity of dental phobia symptoms

IT (n = 74) or WL (n = 77; Fig.). Eighteen showed improvement in outcomes, (baseline: 5.3 ± 0.19, follow-up: 3.4 ±

WL participants and 28 in the IT group but ANCOVAs demonstrated significant 0.27) decreased from baseline to 1-mo

did not receive the allocated intervention. differences in dental anxiety, fear, follow-up for the IT group (see Table 2).

4S

Downloaded from jdr.sagepub.com at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIV FRESNO on July 27, 2015 For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

© International & American Associations for Dental Research

vol. XX • issue X • suppl no. X JDR Clinical Research Supplement

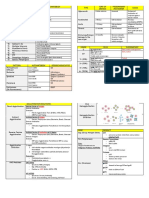

ANCOVAs with the ITT sample Figure.

(N = 115) revealed significant between- CONSORT flowchart.

group differences on the ADIS-IV—

dental fear, 1.23 points (95% CI: 0.61, Received a recruitment call (n = 961)

1.85), P = 0.0001; dental avoidance,

0.82 points (95% CI: 0.01, 1.64), P =

0.047; and overall severity of dental Not assessed for eligibility (n = 607)

phobia symptoms, 0.98 points (95% Could not be reached (n = 459)

Were not interested (n = 148)

CI: 0.39, 1.57), P = 0.0012—all favoring

the IT group after controlling for the

corresponding baseline scores. Of

Assessed for eligibility (n = 354)

patients meeting criteria for phobia at

baseline (n = 83), fewer IT patients

(51.4%) than WL patients (74.4%) met

criteria for dental phobia at follow-up Excluded (n = 203)

Did not meet inclusion criteria (n = 170)

(χ2 = 4.319, P = 0.038). No harms were Refused to participate (n = 33)

noted.

Client Satisfaction with C-CBT Randomized (n = 151)

The mean CSQ score was 26.4 ±

4.4. Almost 83% of patients were very

satisfied with C-CBT. Allocated to waitlist (n = 77) Allocated to immediate treatment (n = 74)

Received allocated intervention Received allocated intervention

(n = 59)* (n = 46)*

Discussion

Allocation

Did not receive allocated Did not receive allocated

intervention (n = 18) intervention (n = 28)

o Did not complete pre- o Did not complete pre-treatment

This study examined the effect of treatment phone phone interview (n = 9)

interview (n = 6)

a brief computerized dental anxiety o Missed dental

o Did not come to dental

appointment early enough to

intervention on patients seeking dental appointment (n = 12) complete intervention (n = 7)

care at a university setting. Compared o Missed dental

appointment (n = 11)

with a WL group, the IT group showed

a significant reduction in dental anxiety,

fear, avoidance, and the presence

of dental phobia as measured by a

reduction from baseline to follow-up on

Follow up

*Received allocated intervention (n = 59) *Received allocated intervention (n = 46)

the MDAS and ADIS-IV. Lost to follow up (n = 5) Lost to follow up (n = 2)

The use of computer-based therapy Received follow up (n = 54) Received follow up (n = 44)

reduces the reliance on in-person

clinician time (Marks et al. 2007), and

it may be as effective as face-to-face

psychotherapy for anxiety disorder The current results should be intervention in a sustainable way, it is

sufferers (Hedman et al. 2012), speeding interpreted with some caution. Only critical that dental personnel are trained

access to care. Many individuals dental treatment–seeking patients who in CBT so that they can provide this

with anxiety disorders do not seek initiated contact with the TUKSoD support to the patients in a regular dental

professional help (Bijl et al. 1998). When dental clinics were recruited into the setting, in which highly trained CBT

they do, they are commonly put on study, thereby excluding individuals therapists are generally not available.

long waiting lists (Lovell and Richards whose anxiety may be present at higher Last, in addition to reductions in dental

2000), and the treatment that they levels and thus prevent them from anxiety, increased attendance at future

eventually receive is often not evidence accessing dental care. There was also dental appointments is also an ultimate

based (Andrews et al. 2004). Much less considerable attrition from baseline goal. No analyses were conducted

is known about the efficacy of these assessment to the day of administration to evaluate this and other oral health

interventions in dental settings. It is of the dental anxiety protocol. Also, outcomes in the current study, as the

therefore important to develop evidence- in the current study, assistance from follow-up period was too brief; clearly,

based help that patients can access psychology personnel trained in CBT was further research is needed. In sum,

easily and that requires little time from a provided at some points in the delivery a new computer-based tool seems

therapist (Hirai and Clum 2006). of the intervention. To disseminate the to be efficacious in reducing fear of

5S

Downloaded from jdr.sagepub.com at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIV FRESNO on July 27, 2015 For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

© International & American Associations for Dental Research

JDR Clinical Research Supplement Month XXXX

Table 2.

Baseline and Follow-up Scores on Primary and Secondary Measures

Immediate Treatment Wait-list Control

Baseline Follow-up Baseline Follow-up

n Mean ± SE n Mean ± SE n Mean ± SE n Mean ± SE P Valuea

MDAS 74 19.5 ± 0.34 74 15.4 ± 0.74 77 19.6 ± 0.30 77 17.6 ± 0.63 0.0019

ADISb

Fear 52 5.6 ± 0.17 52 3.8 ± 0.26 63 5.2 ± 0.17 63 4.8 ± 0.23 0.0001

Avoidance 52 4.6 ± 0.31 52 1.3 ± 0.31 63 3.9 ± 0.32 63 1.0 ± 0.29 0.047

CSR 52 5.3 ± 0.19 52 3.4 ± 0.27 63 4.8 ± 0.20 63 4.0 ± 0.23 0.0012

ADIS, Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule; CSR, clinician’s severity rating; MDAS, Modified Dental Anxiety Scale.

a

P values from analysis-of-covariance models from intention-to-treat analysis.

b

Rating, 0 to 8.

session cognitive treatment of dental phobia:

dental procedures. Examination of its study was funded by a grant from the preparing dental phobics for treatment by

effectiveness when administered in dental Pennsylvania Department of Health. The restructuring negative cognitions. Behav Res

offices under less controlled conditions authors declare no potential conflicts of Ther. 33(8):947–954.

is warranted. It will also be important interest with respect to the authorship Getka EJ, Glass CR. 1992. Behavioral and

to determine which patients derive and/or publication of this article. cognitive-behavioral approaches to the

sufficient benefit and which require reduction of dental anxiety. Behav Ther.

more intense treatment; this protocol References 23(3):433–448.

might be considered as the first level of American Psychiatric Association. 1994. Gordon D, Heimberg RG, Tellez M, Ismail AI.

intervention in a stepped model of care. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental 2013. A critical review of approaches to the

disorders. 4th ed. Washington (DC): treatment of dental anxiety in adults.

American Psychiatric Association. J Anxiety Disord. 27(4):365–378.

Author Contributions

Andrews G, Issakidis C, Sanderson K, Corry J, Haukebø K, Skaret E, Ost LG, Raadal M, Berg

Lapsley H. 2004. Utilizing survey data to E, Sundberg H, Kvale G. 2008. One- vs.

M. Tellez, R.G. Heimberg, contributed inform public policy: comparison of the five-session treatment of dental phobia: a

to conception, design, data acquisition, cost-effectiveness of treatment of ten mental randomized controlled study. J Behav Ther

analysis, and interpretation, drafted disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 184(6):526–533. Exp Psychiatry. 39(3):381–390.

and critically revised the manuscript; Bijl RV, Ravelli A, van Zessen G. 1998. Prevalence Heaton LJ, Leroux BG, Ruff PA, Coldwell SE.

C.M. Potter, contributed to design, data of psychiatric disorder in the general 2013. Computerized dental injection fear

acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, population: results of the Netherlands treatment: a randomized clinical trial. J Dent

drafted and critically revised the Mental Health Survey and Incidence Res. 92(7):37S–42S.

Study (NEMESIS). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Hedman E, Andersson E, Ljótsson B, Andersson

manuscript; D.G. Kinner, D. Jensen, Epidemiol. 33(12):587–595.

E. Waldron, S. Myers Virtue, H. Zhao, G, Andersson E, Schalling M, Lindefors N,

Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Barlow DH. 1994. Anxiety Rück C. 2012. Clinical and genetic outcome

contributed to design, data analysis, Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. New determinants of Internet- and group-

and interpretation, drafted and critically York (NY): Oxford University Press. based cognitive behavior therapy for social

revised the manuscript; A.I. Ismail, Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell anxiety disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand.

contributed to conception, design, and LA. 2001. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety 126(2):126–136.

data interpretation, drafted and critically and mood disorders: implications for the Hirai M, Clum GA. 2006. A meta-analytic study of

revised the manuscript. All authors classification of emotional disorders. self-help interventions for anxiety problems.

gave final approval and agree to be J Abnorm Psychol. 110(1):49–58. Behav Ther. 37(2):99–111.

accountable for all aspects of the work. Coldwell SE, Getz T, Milgrom P, Prall CW, Humphris GM, Morrison T, Lindsay SJ. 1995. The

Spadafora A, Ramsay DS. 1998. CARL: a Modified Dental Anxiety Scale: validation

LabVIEW 3 computer program for the and United Kingdom norms. Community

Acknowledgments

treatment of dental injection fear. Behav Res Dent Health. 12(3):143–150.

Ther. 36(4):429–441. Jöhren P, Enkling N, Heinen R, Sartory G.

We thank Dr. Steve Ondersma for his

Dailey YM, Humphris GM, Lennon MA. 2002. 2007. Clinical outcome of a short-term

contribution to the programming of the Reducing patients’ state anxiety in general psychotherapeutic intervention for the

dental anxiety management intervention dental practice: a randomized controlled trial. treatment of dental phobia. Quintessence Int.

and the dental and psychology students J Dent Res. 81(5):319–322. 38(10):E589–E596.

who participated as actors in the videos de Jongh A, Muris P, Ter Horst G, Van Zuuren King K, Humphris GM. 2010. Evidence to

of the anxiety management program. This F, Schoenmakers N, Makkes P. 1995. One- confirm the cut-off for screening dental

6S

Downloaded from jdr.sagepub.com at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIV FRESNO on July 27, 2015 For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

© International & American Associations for Dental Research

vol. XX • issue X • suppl no. X JDR Clinical Research Supplement

phobia using the Modified Dental Anxiety Nguyen TD, Attkisson CC, Stegner BL. behavioral intervention on dental fear.

Scale. Soc Sci Dent. 1(1):21–28. 1983. Assessment of patient satisfaction: J Public Health Dent. 75(1):64–73.

Kvale G, Berggren U, Milgrom P. 2004. Dental development and refinement of a service

Tellez M, Kinner DG, Heimberg RG, Lim S,

fear in adults: a meta-analysis of behavioral evaluation questionnaire. Eval Program

Ismail AI. 2015. Prevalence and correlates

interventions. Community Dent Oral Plann. 6(3–4):299–313.

of dental anxiety in patients seeking dental

Epidemiol. 32(4):250–264. Rubin DB. 1987. Multiple imputation for care. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol.

Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA. 1979. nonresponse in surveys. New York (NY): 43(2):135–142.

Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Thom A, Sartory G, Jöhren P. 2000. Comparison

development of a general scale. Eval Schulman S, Potter C, Jensen D, Tellez M, between one-session psychological

Program Plann. 2(3):197–207. Ismail AI, Heimberg RG. 2014. Comparison treatment and benzodiazepine in

Locker D, Liddell A, Shapiro D. 1999. Diagnostic of standard and alternative methods of dental phobia. J Consult Clin Psychol.

categories of dental anxiety: a population- scoring the modified dental anxiety scale as 68(3):378–387.

based study. Behav Res Ther. 37(1):25–37. a screener for dental phobia. Philadelphia U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. 2010 census

(PA): Association for Behavioral and [accessed 2015 Mar 10]. http://www.census

Lovell K, Richards R. 2000. Multiple access

Cognitive Therapies. .gov/2010census/.

points and levels of entry (MAPLE):

ensuring choice, accessibility and equity Sohn W, Ismail AI. 2005. Regular dental Wannemueller A, Jöhren P, Haug S, Hatting M,

for CBT services. Behav Cogn Psychother. visits and dental anxiety in an adult Elsesser K, Sartory G. 2011. A practice

28(4):379–339. dentate population. J Am Dent Assoc. based comparison of brief cognitive

Marks IM, Cavanagh K, Gega L. 2007. Hands-on 136(1):58–66. behavioural treatment, two kinds of

help: computer-aided psychotherapy. Spindler H, Staugaard SR, Nicolaisen C, hypnosis, and general anaesthesia in

Hove (UK): Psychology Press. (Maudsley Poulsen R. 2015. A randomized controlled dental phobia. Psychother Psychosom.

monograph No. 49) trial of the effect of a brief cognitive- 80(3):159–165.

7S

Downloaded from jdr.sagepub.com at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIV FRESNO on July 27, 2015 For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

© International & American Associations for Dental Research

You might also like

- NAPLEX Drugs TableDocument71 pagesNAPLEX Drugs Tablestarobin100% (3)

- Pediatric Nursing Clinical Objectives.Document2 pagesPediatric Nursing Clinical Objectives.edrinsne100% (4)

- Evaluation of Anxiety of Patients For Dental Procedures by Using CORAH'S Dental Anxiety ScaleDocument3 pagesEvaluation of Anxiety of Patients For Dental Procedures by Using CORAH'S Dental Anxiety ScaleNajwan AdilNo ratings yet

- Eos 130 0Document10 pagesEos 130 0Jacqueline FelipeNo ratings yet

- 2023 Lu - RCT MetaqDocument13 pages2023 Lu - RCT Metaqfabian.balazs.93No ratings yet

- Anxiety Before Dental Procedures Among PatientsDocument3 pagesAnxiety Before Dental Procedures Among PatientsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Appu Kutt An 2015Document7 pagesAppu Kutt An 2015Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Anxiety About Dental Treatment - A Gender IssueDocument6 pagesAnxiety About Dental Treatment - A Gender Issueyeniescamilla191213No ratings yet

- Adj 67 S3Document11 pagesAdj 67 S3Wallacy MoraisNo ratings yet

- Hey Man 2018Document7 pagesHey Man 2018Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Outcome of Chair-Side Dental Fear Treatment: Long-Term Follow-Up in Public Health SettingDocument7 pagesResearch Article: Outcome of Chair-Side Dental Fear Treatment: Long-Term Follow-Up in Public Health SettingAdriani PanjaitanNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Outcome of Chair-Side Dental Fear Treatment: Long-Term Follow-Up in Public Health SettingDocument7 pagesResearch Article: Outcome of Chair-Side Dental Fear Treatment: Long-Term Follow-Up in Public Health SettingAdriani PanjaitanNo ratings yet

- 2021 Lin - Translatipon ValidationDocument11 pages2021 Lin - Translatipon Validationfabian.balazs.93No ratings yet

- Nonpharmacologic Intervention On The Prevention of Pain and Anxiety During Pediatric Dental Care: A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesNonpharmacologic Intervention On The Prevention of Pain and Anxiety During Pediatric Dental Care: A Systematic ReviewJorge Luis Ramos MaqueraNo ratings yet

- 10 1111@jcpe 13362Document9 pages10 1111@jcpe 13362Dr.Niveditha SNo ratings yet

- Your Big IdeaDocument13 pagesYour Big Idea0 0No ratings yet

- Efficacy of Aromatherapy On Dental AnxietyDocument39 pagesEfficacy of Aromatherapy On Dental AnxietyDafne MendozaNo ratings yet

- JCM 09 03086Document15 pagesJCM 09 03086Faisal BudisasmitaNo ratings yet

- Satisfaction With Orthodontic Treatment Outcome: Original ArticleDocument7 pagesSatisfaction With Orthodontic Treatment Outcome: Original ArticleVANESA REYESNo ratings yet

- Effect of Audiovisual Distraction On The ManagemenDocument10 pagesEffect of Audiovisual Distraction On The Managemendwirabiatul adwiyahaliNo ratings yet

- Management of Dentinehypersensitivity Ef Cacy Ofprofessionally Andself-Administered AgentsDocument47 pagesManagement of Dentinehypersensitivity Ef Cacy Ofprofessionally Andself-Administered AgentsNaoki MezarinaNo ratings yet

- 2 Master Article 2Document5 pages2 Master Article 2neetika guptaNo ratings yet

- Patient Education and Counseling: Heide Glaesmer, Hendrik Geupel, Rainer HaakDocument4 pagesPatient Education and Counseling: Heide Glaesmer, Hendrik Geupel, Rainer HaakSung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Jurnal AntibiotikDocument5 pagesJurnal AntibiotikSela PutrianaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Verbal and Visual Information On The Level of Anxiety Among Dental Implant PatientsDocument6 pagesEffect of Verbal and Visual Information On The Level of Anxiety Among Dental Implant PatientsMarius MoroianuNo ratings yet

- AOM - Clinical Decision SupportDocument11 pagesAOM - Clinical Decision SupportfatiisaadatNo ratings yet

- Management of Dentine Hypersensitivity: Efficacy of Professionally and Self-Administered AgentsDocument47 pagesManagement of Dentine Hypersensitivity: Efficacy of Professionally and Self-Administered AgentsChristine HacheNo ratings yet

- 2005 Coolidge - Psychometric Properties of The Revised Dental Beliefs SurveyDocument9 pages2005 Coolidge - Psychometric Properties of The Revised Dental Beliefs Surveyfabian.balazs.93No ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Impact of Educational Status On The Anxiety Levels of Patients Undergoing Root Canal Therapy Using Modified Corah Dental Anxiety Scale-A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument11 pagesEvaluation of The Impact of Educational Status On The Anxiety Levels of Patients Undergoing Root Canal Therapy Using Modified Corah Dental Anxiety Scale-A Cross-Sectional Studykumar chandan srivastavaNo ratings yet

- British Dental Journal Volume 189 Issue 7 2000 (Doi 10.1038/sj - bdj.4800777) Cohen, S M Fiske, J Newton, J T - Behavioural Dentistry - The Impact of Dental Anxiety On Daily LivingDocument6 pagesBritish Dental Journal Volume 189 Issue 7 2000 (Doi 10.1038/sj - bdj.4800777) Cohen, S M Fiske, J Newton, J T - Behavioural Dentistry - The Impact of Dental Anxiety On Daily LivingrkotichaNo ratings yet

- How Decisions Are Made Antibiotic Stewardship in DentistryDocument6 pagesHow Decisions Are Made Antibiotic Stewardship in DentistryMuhammad SdiqNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Disorder and Alternative Medicine Therapies Among Dentists of North India: A Descriptive StudyDocument6 pagesPrevalence of Musculoskeletal Disorder and Alternative Medicine Therapies Among Dentists of North India: A Descriptive Studyjosselyn ayalaNo ratings yet

- 2.3. 2010. Kakudate. AutoeficaciaDocument6 pages2.3. 2010. Kakudate. AutoeficaciaEfräin GarciaNo ratings yet

- Emergency Dental Treatment Among Patients Waitlisted For The Operating RoomDocument5 pagesEmergency Dental Treatment Among Patients Waitlisted For The Operating RoomnatalyaNo ratings yet

- NAGARKAS S. 2023. - Evidence-Based Fact Checking For Selective Procedures in Restorative DentistryDocument14 pagesNAGARKAS S. 2023. - Evidence-Based Fact Checking For Selective Procedures in Restorative DentistryNicolás SotoNo ratings yet

- 26PNEFor - Web Munhoz MSPDocument14 pages26PNEFor - Web Munhoz MSPjordi4u8749No ratings yet

- Muscle AnksşiyeteDocument7 pagesMuscle Anksşiyetegerekligerekli3555No ratings yet

- Behavior Management (1-2)Document2 pagesBehavior Management (1-2)Megalia ArafahNo ratings yet

- Burghardt 2017Document10 pagesBurghardt 2017Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Listl 2015Document9 pagesListl 2015Gloria SequeiraNo ratings yet

- 2023 Andrade - REVIEWDocument4 pages2023 Andrade - REVIEWfabian.balazs.93No ratings yet

- Autoeficacia OralDocument6 pagesAutoeficacia OralANDREA VERONICA YANEZ MORANo ratings yet

- Brazilian Dentists' Perception of Dentin Hypersensitivity ManagementDocument8 pagesBrazilian Dentists' Perception of Dentin Hypersensitivity ManagementNaoki MezarinaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0099239919303565 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0099239919303565 MainCaio GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Patients Compliance On Removable OrthodoDocument5 pagesPatients Compliance On Removable OrthodoHasna HumairaNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion Interventions To Improve Oral Health of Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument12 pagesHealth Promotion Interventions To Improve Oral Health of Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisSarbu AndraNo ratings yet

- Measuring Children's Dental Anxiety: Oral Cancer /paediatric DentistryDocument2 pagesMeasuring Children's Dental Anxiety: Oral Cancer /paediatric DentistryManda JoanNo ratings yet

- La Lit Review-Jennifer Draper-2-2Document9 pagesLa Lit Review-Jennifer Draper-2-2api-653567856No ratings yet

- 1963 Some MotivesDocument9 pages1963 Some MotivesbaridinoNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For Anxious Paediatric Dental Patients: A Systematic ReviewDocument10 pagesCognitive Behaviour Therapy For Anxious Paediatric Dental Patients: A Systematic ReviewSung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Clinical Exp Dental Res - 2021 - Delgado - Evaluation of Children S Pain Expression and Behavior Using Audio VisualDocument8 pagesClinical Exp Dental Res - 2021 - Delgado - Evaluation of Children S Pain Expression and Behavior Using Audio Visualanonimo exeNo ratings yet

- Hesitance StudyDocument20 pagesHesitance StudydrpiyuporwalNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Children With Dental Anxiety: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument10 pagesCognitive Behavioral Therapy For Children With Dental Anxiety: A Randomized Controlled TrialLingga FhdsNo ratings yet

- Paper 12. Tomasi Et Al. (2007)Document9 pagesPaper 12. Tomasi Et Al. (2007)RodolfoDamásioNunesNo ratings yet

- Management of The Dentally Anxious Patient: The Dentist's PerspectiveDocument8 pagesManagement of The Dentally Anxious Patient: The Dentist's PerspectiveJoseph MeyersonNo ratings yet

- Choi 2020Document7 pagesChoi 2020Hammad AkramNo ratings yet

- Phadraig Et Al 2019 - Systematic DesensitizationDocument16 pagesPhadraig Et Al 2019 - Systematic DesensitizationCarlindo e CarlindoNo ratings yet

- The Use of Prophylactic Antibiotics Prior To Dental Procedures in Patients With Prosthetic JointsDocument14 pagesThe Use of Prophylactic Antibiotics Prior To Dental Procedures in Patients With Prosthetic JointsalikaNo ratings yet

- A Trial Examining An Advanced Practice Nurse Intervention To Promote Medication Adherence and Symptom Management in Adult Cancer Patients Prescribed Oral Anti-Cancer Agents - Study ProtocolDocument12 pagesA Trial Examining An Advanced Practice Nurse Intervention To Promote Medication Adherence and Symptom Management in Adult Cancer Patients Prescribed Oral Anti-Cancer Agents - Study ProtocolyawnerNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Interceptive Orthodontic Treatment in Reducing MalocclusionsDocument8 pagesEffectiveness of Interceptive Orthodontic Treatment in Reducing MalocclusionsAriana de LeonNo ratings yet

- Treatment Planning in Restorative Dentistry and Implant ProsthodonticsFrom EverandTreatment Planning in Restorative Dentistry and Implant ProsthodonticsNo ratings yet

- Clinical and Neurobiological Effects of Aerobic Exercise in Dental Phobia: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesClinical and Neurobiological Effects of Aerobic Exercise in Dental Phobia: A Randomized Controlled TrialSung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Is Dental Phobia A Blood-Injection-Injury Phobia?Document10 pagesResearch Article: Is Dental Phobia A Blood-Injection-Injury Phobia?Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Hea LTH S Urve Y: Research InsightsDocument2 pagesHea LTH S Urve Y: Research InsightsSung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Burghardt 2017Document10 pagesBurghardt 2017Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- The Oral Health of Individuals With Dental Phobia: A Multivariate Analysis of The Adult Dental Health Survey, 2009Document10 pagesThe Oral Health of Individuals With Dental Phobia: A Multivariate Analysis of The Adult Dental Health Survey, 2009Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Dental Fear and Phobia Relative To Other Fear and Phobia SubtypesDocument9 pagesPrevalence of Dental Fear and Phobia Relative To Other Fear and Phobia SubtypesSung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Hey Man 2018Document7 pagesHey Man 2018Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Frontal Late Positivity in Dental Phobia: A Study On Gender DifferencesDocument7 pagesFrontal Late Positivity in Dental Phobia: A Study On Gender DifferencesSung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Australian Dental Journal: The Extent and Nature of Dental Fear and Phobia in AustraliaDocument10 pagesAustralian Dental Journal: The Extent and Nature of Dental Fear and Phobia in AustraliaSung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Original Research: The Prevalence of Dental Phobia Among The Population in Riyadh CityDocument5 pagesOriginal Research: The Prevalence of Dental Phobia Among The Population in Riyadh CitySung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Blood-Injection-Injury Phobia in Older Adults: Beyon Miloyan and William W. EatonDocument6 pagesBlood-Injection-Injury Phobia in Older Adults: Beyon Miloyan and William W. EatonSung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Anxiety, Stress, & Coping: An International JournalDocument15 pagesAnxiety, Stress, & Coping: An International JournalSung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Lillehaugagdal 2008Document6 pagesLillehaugagdal 2008Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Dental Fear/Anxiety: Managing Anxious or Fearful PatientsDocument3 pagesDental Fear/Anxiety: Managing Anxious or Fearful PatientsSung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Patient Education and Counseling: Heide Glaesmer, Hendrik Geupel, Rainer HaakDocument4 pagesPatient Education and Counseling: Heide Glaesmer, Hendrik Geupel, Rainer HaakSung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Do Traumatic Events Have More Impact On The Development of Dental Anxiety Than Negative, Non-Traumatic Events?Document6 pagesDo Traumatic Events Have More Impact On The Development of Dental Anxiety Than Negative, Non-Traumatic Events?Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Beating Dental Phobia: ClinicalDocument1 pageBeating Dental Phobia: ClinicalSung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Changes in Heart Rate During Third Molar SurgeryDocument6 pagesChanges in Heart Rate During Third Molar SurgerySung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Appu Kutt An 2015Document7 pagesAppu Kutt An 2015Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Alex o Poulos 2018Document25 pagesAlex o Poulos 2018Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- 10.1186@s12903 018 0644 X 2Document9 pages10.1186@s12903 018 0644 X 2Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- 10.1186@s12903 018 0644 XDocument9 pages10.1186@s12903 018 0644 XSung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Schmid Leuz2007Document13 pagesSchmid Leuz2007Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Piis0901502714001611 2Document6 pagesPiis0901502714001611 2Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Seligman 2017Document16 pagesSeligman 2017Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Transfusion Medicine - RK SaranDocument80 pagesTransfusion Medicine - RK SaranAvinashNo ratings yet

- Affimed Presentation-Mar2020 Final-1 PDFDocument22 pagesAffimed Presentation-Mar2020 Final-1 PDFElio GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Menstrual CycleDocument24 pagesMenstrual CycleMonika Bagchi100% (5)

- Newer Modes of Ventilation1Document7 pagesNewer Modes of Ventilation1Saradha PellatiNo ratings yet

- Management of Endodontic Emergencies: Chapter OutlineDocument9 pagesManagement of Endodontic Emergencies: Chapter OutlineNur IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Seminar Prest UbthDocument19 pagesSeminar Prest UbthChioma PaschalineNo ratings yet

- A Patient 'S Guide To Refractive SurgeryDocument7 pagesA Patient 'S Guide To Refractive SurgeryJon HinesNo ratings yet

- MDS3 Ch30 Dispensing Mar2012 PDFDocument0 pagesMDS3 Ch30 Dispensing Mar2012 PDFyiemetieNo ratings yet

- Multi Bandage Presentation - URIEL Meditex LTDDocument9 pagesMulti Bandage Presentation - URIEL Meditex LTDIsrael ExporterNo ratings yet

- (MP 2004) (AIIMS May 2014) : H Ea LT H C Ar e in in Di A, H Ea LT H PL An Ni N G An D M AnDocument7 pages(MP 2004) (AIIMS May 2014) : H Ea LT H C Ar e in in Di A, H Ea LT H PL An Ni N G An D M AnDr-Sanjay SinghaniaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Awareness and Attitude Towards Organ Donation Among Undergraduate Medical Students of HaryanaDocument5 pagesKnowledge, Awareness and Attitude Towards Organ Donation Among Undergraduate Medical Students of HaryanaVinissha JeyarajNo ratings yet

- Drug Study Amoxicillin PDFDocument4 pagesDrug Study Amoxicillin PDFMc SantosNo ratings yet

- Mnemonic 3Document10 pagesMnemonic 3parackalphilipNo ratings yet

- TEST-20 Menopause: Part ADocument18 pagesTEST-20 Menopause: Part ANimisha akhil Akhil100% (1)

- Ministry of Absorption Health Services BookletDocument63 pagesMinistry of Absorption Health Services BookletEnglishAccessibilityNo ratings yet

- HemodialysisDocument2 pagesHemodialysisAr JayNo ratings yet

- The Tearing Patient: Diagnosis and Management: Ophthalmic PearlsDocument3 pagesThe Tearing Patient: Diagnosis and Management: Ophthalmic PearlsAnonymous otk8ohj9No ratings yet

- Journals-2 PDFDocument280 pagesJournals-2 PDFBhupendra Singh100% (1)

- CARMS Timeline 2023-2024Document3 pagesCARMS Timeline 2023-2024haykalkNo ratings yet

- ISBB Wall Notes PDFDocument8 pagesISBB Wall Notes PDFLynx EemanNo ratings yet

- RMC Meu Annual Report 2019 20Document14 pagesRMC Meu Annual Report 2019 20abcqwe123No ratings yet

- Law and Ethics in Medical PracticeDocument5 pagesLaw and Ethics in Medical Practiceandersonmack047No ratings yet

- 15 Antifungal Drugs-Notes-3Document43 pages15 Antifungal Drugs-Notes-3Sindhu BabuNo ratings yet

- Regina Eryka B. Dela Cruz: February - March 2020Document3 pagesRegina Eryka B. Dela Cruz: February - March 2020api-510887381No ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument9 pagesResearch ProposalAbiola IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Mothers Knowledge and Practices of Minor IllnessesDocument17 pagesMothers Knowledge and Practices of Minor IllnessesSTANN KAZIPETNo ratings yet

- Super Speciality Eye Hospital: Literature and Data CollectionDocument35 pagesSuper Speciality Eye Hospital: Literature and Data Collectionamir alamNo ratings yet

- Adhikari Suraksha Kavach ClauseDocument25 pagesAdhikari Suraksha Kavach Clauseapi-3777867No ratings yet