Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

36 viewsJane Eyre, The Skeptic Penny Dreadful: Charlotte Brontë'S Realistic Incorporation of The Gothic Tradition, Carolina Do Nascimento de Sousa

Jane Eyre, The Skeptic Penny Dreadful: Charlotte Brontë'S Realistic Incorporation of The Gothic Tradition, Carolina Do Nascimento de Sousa

Uploaded by

Quake11This document discusses Charlotte Bronte's novel Jane Eyre and how it incorporates elements of both realism and Gothic fiction. In the 19th century, Britain underwent rapid social, scientific, and religious changes that led to new literary genres like Gothic fiction emerging. While many novels of the time were realistic, some authors like Bronte incorporated Gothic elements to explore themes of religious uncertainty, spiritualism, and the unknown. Jane Eyre features settings and characters reflective of Victorian society, but also includes supernatural occurrences reflecting the spiritual questioning of the time. The essay analyzes how Bronte's own plural religious views are reflected in her blending of realism with Gothic conventions in Jane Eyre.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Whitall N. Perry, Marco Pallis, Huston Smith - The Spiritual Ascent A Compendium of The World's WisdomDocument2,141 pagesWhitall N. Perry, Marco Pallis, Huston Smith - The Spiritual Ascent A Compendium of The World's WisdomCaio Cardoso100% (3)

- The Crisis of Reason (Burrow) PDFDocument370 pagesThe Crisis of Reason (Burrow) PDFFrancisco Reyes100% (1)

- Heiland D. - Gothic and The Generation of IdeasDocument18 pagesHeiland D. - Gothic and The Generation of IdeasStanislav GladkovNo ratings yet

- A List of John Meadows Programs Sstmodpdf CompressDocument3 pagesA List of John Meadows Programs Sstmodpdf CompressQuake11No ratings yet

- Characteristics of Victorian LiteratureDocument2 pagesCharacteristics of Victorian LiteratureDabe Zine81% (16)

- Aristotle's Children: How Christians, Muslims, and Jews Rediscovered Ancient Wisdom and Illuminated the Middle AgesFrom EverandAristotle's Children: How Christians, Muslims, and Jews Rediscovered Ancient Wisdom and Illuminated the Middle AgesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Origins of the English Novel, 1600–1740From EverandThe Origins of the English Novel, 1600–1740Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Flex UK - September 2018 PDFDocument148 pagesFlex UK - September 2018 PDFQuake11100% (1)

- Flex USA July-August 2017Document235 pagesFlex USA July-August 2017Quake11100% (2)

- Victorian NovelDocument14 pagesVictorian Novelluluneil100% (1)

- 396 1542 1 PBDocument7 pages396 1542 1 PBFlorentina TeodoraNo ratings yet

- Sacred Tears: Sentimentality in Victorian LiteratureFrom EverandSacred Tears: Sentimentality in Victorian LiteratureRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Victorian AgeDocument7 pagesVictorian AgeKris Belea100% (2)

- Man and the Divine: New Light on Man's Ancient Engagement with God and the History of ThoughtFrom EverandMan and the Divine: New Light on Man's Ancient Engagement with God and the History of ThoughtNo ratings yet

- A Catholic Approach To HistoryDocument18 pagesA Catholic Approach To HistoryLuis FelipeNo ratings yet

- Topic 50 Victorian NovelDocument5 pagesTopic 50 Victorian NovelCris BravoNo ratings yet

- Hayden White A Portrait in Seven PosesDocument25 pagesHayden White A Portrait in Seven Posespopmarko43No ratings yet

- Hobbit Virtues: Rediscovering J. R. R. Tolkien's Ethics from The Lord of the RingsFrom EverandHobbit Virtues: Rediscovering J. R. R. Tolkien's Ethics from The Lord of the RingsRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Survey The Prominent Literary Trends of The Victorian Age.Document7 pagesSurvey The Prominent Literary Trends of The Victorian Age.নিজন্ম সূর্য89% (9)

- What Are The Main Features of PostmodernismDocument4 pagesWhat Are The Main Features of PostmodernismSMCNo ratings yet

- About ModernismDocument86 pagesAbout Modernismmivascu23No ratings yet

- Legacy of Westcott & Hort (& The Occult Revival)Document27 pagesLegacy of Westcott & Hort (& The Occult Revival)Jesus LivesNo ratings yet

- AbstractDocument21 pagesAbstractInma Puntas SerranoNo ratings yet

- Political Factors As The Catalyst of The EnlightenmentDocument5 pagesPolitical Factors As The Catalyst of The EnlightenmentLaura Guo (Han)No ratings yet

- Danny PraetDocument10 pagesDanny PraetskimnosNo ratings yet

- Myths History and The Construction of NaDocument10 pagesMyths History and The Construction of NarojetasatNo ratings yet

- Aspell, Patrick J - Medieval Western PhilosophyDocument350 pagesAspell, Patrick J - Medieval Western Philosophyapi-3738033No ratings yet

- How Are Gothic Themes Shown in British Literature?Document9 pagesHow Are Gothic Themes Shown in British Literature?api-444969952No ratings yet

- Sanders - U3 Late Victorian and Edwardian LiteratureDocument12 pagesSanders - U3 Late Victorian and Edwardian LiteratureMelanie HadzegaNo ratings yet

- Christopher S. Celenza. The Lost Italian Renaissance - Humanists, Historians, and Latin's Legacy (Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 58, Issue 2) (2005)Document2 pagesChristopher S. Celenza. The Lost Italian Renaissance - Humanists, Historians, and Latin's Legacy (Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 58, Issue 2) (2005)Joshua AlfaroNo ratings yet

- 01 Church - of - England - Spiritualism - and - The - Decline - of - Religious - Belief PDFDocument17 pages01 Church - of - England - Spiritualism - and - The - Decline - of - Religious - Belief PDFExalumnos Instituto AlonsodeErcillaNo ratings yet

- Victorian Literature Research Paper TopicsDocument7 pagesVictorian Literature Research Paper Topicsnbaamubnd100% (1)

- Elias MetahistoricalRomanceDocument15 pagesElias MetahistoricalRomanceMoh FathoniNo ratings yet

- The Stoic View of LifeDocument17 pagesThe Stoic View of LifeCarlos IsacazNo ratings yet

- Invisible Worlds: Death, Religion And The Supernatural In England, 1500-1700From EverandInvisible Worlds: Death, Religion And The Supernatural In England, 1500-1700Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Ethics through Literature: Ascetic and Aesthetic Reading in Western CultureFrom EverandEthics through Literature: Ascetic and Aesthetic Reading in Western CultureRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Age of Enlightenment Influencing Neoclassicism PDFDocument9 pagesAge of Enlightenment Influencing Neoclassicism PDFvandana1193No ratings yet

- Fantasia MedievalDocument8 pagesFantasia MedievalDaniel WolterNo ratings yet

- Gothic LiteratureDocument5 pagesGothic Literatureandrew irunguNo ratings yet

- Modes of Faith: Secular Surrogates for Lost Religious BeliefFrom EverandModes of Faith: Secular Surrogates for Lost Religious BeliefNo ratings yet

- Literature Test Revision NotesDocument4 pagesLiterature Test Revision Notesbryan6920No ratings yet

- Review PaperDocument4 pagesReview PaperChristian AlfornonNo ratings yet

- Intro The Victorian PeriodDocument7 pagesIntro The Victorian Periodabeer.hussien1296No ratings yet

- Scared Monsters: The Gothic Nineteenth Century and The Theology of EvilDocument30 pagesScared Monsters: The Gothic Nineteenth Century and The Theology of EvilBijaylaxmi Sahoo100% (1)

- Jordan, Michael - Myths of The World, A Thematic EncyclopediaDocument228 pagesJordan, Michael - Myths of The World, A Thematic Encyclopediamas2004100% (1)

- EarnestnessDocument4 pagesEarnestnessnicole91403No ratings yet

- History Compass - 2022 - Milne Smith - Gender and Madness in Nineteenth Century BritainDocument10 pagesHistory Compass - 2022 - Milne Smith - Gender and Madness in Nineteenth Century BritainLaura MoreiraNo ratings yet

- (The Sociology of Religion) The SAGE Handbook of Sociology (Craig Calhoun, Chris Rojek and Bryan S. Turner)Document18 pages(The Sociology of Religion) The SAGE Handbook of Sociology (Craig Calhoun, Chris Rojek and Bryan S. Turner)nev.thomas96No ratings yet

- MythologyDocument4 pagesMythologymikasaackermannn23No ratings yet

- The Lotus and LionDocument287 pagesThe Lotus and Lionsd76123No ratings yet

- Hayden White Narrative DiscourseDocument66 pagesHayden White Narrative DiscourseAmalia IoneLaNo ratings yet

- Essay - Experiencing EnculturationDocument8 pagesEssay - Experiencing EnculturationIsha NisarNo ratings yet

- Wilkie Collins, The Woman in WhiteDocument6 pagesWilkie Collins, The Woman in WhiteAnik KarmakarNo ratings yet

- Boethius and SophiaDocument20 pagesBoethius and SophiaRosa.MarioNo ratings yet

- JV CultDocument10 pagesJV Cultmingeunuchbureaucratgmail.comNo ratings yet

- The Victorian Spirit of UncertaintyDocument15 pagesThe Victorian Spirit of UncertaintyVarunVermaNo ratings yet

- Bradshaw. On UtopiaDocument28 pagesBradshaw. On UtopiaCarlos VNo ratings yet

- Kelley 2005Document14 pagesKelley 2005Gabriel CidNo ratings yet

- Bevir-Historicism, Human Sciences Victorian BritainDocument20 pagesBevir-Historicism, Human Sciences Victorian BritainrebenaqueNo ratings yet

- Brochure RESIDENCES Legacy F&C Low Res CompressedDocument31 pagesBrochure RESIDENCES Legacy F&C Low Res CompressedQuake11No ratings yet

- Finalmente CaralhoDocument1 pageFinalmente CaralhoQuake11No ratings yet

- Voynich Manuscript PDFDocument209 pagesVoynich Manuscript PDFQuake11100% (2)

- Bell and Another Appellants Lever Brothers, Limited, And!Document1 pageBell and Another Appellants Lever Brothers, Limited, And!Quake11No ratings yet

- Cubicost Tas & TRB Elementary Quiz - AnswerDocument9 pagesCubicost Tas & TRB Elementary Quiz - AnswerChee HernNo ratings yet

- Expect Respect ProgramDocument2 pagesExpect Respect ProgramCierra Olivia Thomas-WilliamsNo ratings yet

- L2 - Cryptococcus NeoformansDocument44 pagesL2 - Cryptococcus Neoformansdvph2fck6qNo ratings yet

- Great by Choice - Collins.ebsDocument13 pagesGreat by Choice - Collins.ebsShantanu Raktade100% (1)

- Ra 10868Document11 pagesRa 10868Edalyn Capili100% (1)

- The Literary Comparison Contrast EssayDocument7 pagesThe Literary Comparison Contrast EssayThapelo SebolaiNo ratings yet

- Company Profile: TML Drivelines LTD (Tata Motors, Jamshedpur)Document5 pagesCompany Profile: TML Drivelines LTD (Tata Motors, Jamshedpur)Madhav NemalikantiNo ratings yet

- BBB October 2023 Super SpecialsDocument4 pagesBBB October 2023 Super Specialsactionrazor38No ratings yet

- HorrorDocument25 pagesHorrorYasser Nutalenko100% (2)

- World Red Cross DayDocument17 pagesWorld Red Cross DayAshwani K SharmaNo ratings yet

- 8.b SOAL PAT B INGGRIS KELAS 8Document6 pages8.b SOAL PAT B INGGRIS KELAS 8M Adib MasykurNo ratings yet

- GenEd - Lumabas Jan 2022Document4 pagesGenEd - Lumabas Jan 2022angelo mabulaNo ratings yet

- The African Essentials - Presentation - O - 2019Document34 pagesThe African Essentials - Presentation - O - 2019Fatima SilvaNo ratings yet

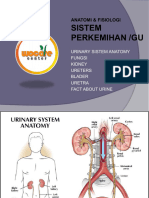

- Anatomy GuDocument13 pagesAnatomy Gujefel umarNo ratings yet

- The Wholly BibleDocument10 pagesThe Wholly BibleFred_Carpenter_12No ratings yet

- Mauro Giuliani: Etudes Instructives, Op. 100Document35 pagesMauro Giuliani: Etudes Instructives, Op. 100Thiago Camargo Juvito de Souza100% (1)

- 11 Ultimate Protection Video Charitable Religious TrustsDocument12 pages11 Ultimate Protection Video Charitable Religious TrustsKing FishNo ratings yet

- Hot Vs Cold Lab Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesHot Vs Cold Lab Lesson Planapi-497020000No ratings yet

- Doctorine of Necessity in PakistanDocument14 pagesDoctorine of Necessity in Pakistandijam_786100% (9)

- Book SoftDocument318 pagesBook SoftBrian Takudzwa MuzembaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Alternatives NotesDocument10 pagesComparison of Alternatives NotesLibyaFlowerNo ratings yet

- Azkoyen Technical Guide AN8000Document38 pagesAzkoyen Technical Guide AN8000pastilhasNo ratings yet

- Sun Pharma ProjectDocument26 pagesSun Pharma ProjectVikas Ahuja100% (1)

- Effect of Bolt Pretension in Single Lap Bolted Joint IJERTV4IS010269Document4 pagesEffect of Bolt Pretension in Single Lap Bolted Joint IJERTV4IS010269ayush100% (1)

- Draft Local Budget Circular Re Grant of Honorarium To SK Officials - v1Document4 pagesDraft Local Budget Circular Re Grant of Honorarium To SK Officials - v1rodysseusNo ratings yet

- Maribelle Z. Neri vs. Ryan Roy Yu (Full Text, Word Version)Document11 pagesMaribelle Z. Neri vs. Ryan Roy Yu (Full Text, Word Version)Emir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Note On F3 SC C2 TransportationDocument4 pagesNote On F3 SC C2 Transportationgan tong hock a.k.a ganosNo ratings yet

- FSA Enrollment Form - English PDFDocument1 pageFSA Enrollment Form - English PDFLupita MontalvanNo ratings yet

- (Promotion Policy of APDCL) by Debasish Choudhury: RecommendationDocument1 page(Promotion Policy of APDCL) by Debasish Choudhury: RecommendationDebasish ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- By Laws Amended As at 1 July 2022 PDFDocument364 pagesBy Laws Amended As at 1 July 2022 PDFJING YI LIMNo ratings yet

Jane Eyre, The Skeptic Penny Dreadful: Charlotte Brontë'S Realistic Incorporation of The Gothic Tradition, Carolina Do Nascimento de Sousa

Jane Eyre, The Skeptic Penny Dreadful: Charlotte Brontë'S Realistic Incorporation of The Gothic Tradition, Carolina Do Nascimento de Sousa

Uploaded by

Quake110 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

36 views1 pageThis document discusses Charlotte Bronte's novel Jane Eyre and how it incorporates elements of both realism and Gothic fiction. In the 19th century, Britain underwent rapid social, scientific, and religious changes that led to new literary genres like Gothic fiction emerging. While many novels of the time were realistic, some authors like Bronte incorporated Gothic elements to explore themes of religious uncertainty, spiritualism, and the unknown. Jane Eyre features settings and characters reflective of Victorian society, but also includes supernatural occurrences reflecting the spiritual questioning of the time. The essay analyzes how Bronte's own plural religious views are reflected in her blending of realism with Gothic conventions in Jane Eyre.

Original Description:

Original Title

Plgfin

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document discusses Charlotte Bronte's novel Jane Eyre and how it incorporates elements of both realism and Gothic fiction. In the 19th century, Britain underwent rapid social, scientific, and religious changes that led to new literary genres like Gothic fiction emerging. While many novels of the time were realistic, some authors like Bronte incorporated Gothic elements to explore themes of religious uncertainty, spiritualism, and the unknown. Jane Eyre features settings and characters reflective of Victorian society, but also includes supernatural occurrences reflecting the spiritual questioning of the time. The essay analyzes how Bronte's own plural religious views are reflected in her blending of realism with Gothic conventions in Jane Eyre.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

36 views1 pageJane Eyre, The Skeptic Penny Dreadful: Charlotte Brontë'S Realistic Incorporation of The Gothic Tradition, Carolina Do Nascimento de Sousa

Jane Eyre, The Skeptic Penny Dreadful: Charlotte Brontë'S Realistic Incorporation of The Gothic Tradition, Carolina Do Nascimento de Sousa

Uploaded by

Quake11This document discusses Charlotte Bronte's novel Jane Eyre and how it incorporates elements of both realism and Gothic fiction. In the 19th century, Britain underwent rapid social, scientific, and religious changes that led to new literary genres like Gothic fiction emerging. While many novels of the time were realistic, some authors like Bronte incorporated Gothic elements to explore themes of religious uncertainty, spiritualism, and the unknown. Jane Eyre features settings and characters reflective of Victorian society, but also includes supernatural occurrences reflecting the spiritual questioning of the time. The essay analyzes how Bronte's own plural religious views are reflected in her blending of realism with Gothic conventions in Jane Eyre.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 1

Os Fazedores de Letras

Jornal dos Estudantes da Faculdade de Letras da

Universidade de Lisboa

! MENU ! ! ! ! !

JANE EYRE, THE SKEPTIC

PENNY DREADFUL:

CHARLOTTE BRONTË’S

REALISTIC INCORPORATION

OF THE GOTHIC TRADITION,

CAROLINA DO NASCIMENTO DE

SOUSA

! 08/02/2021 ! Ensaio ! Deixe um

comentário

Ensaio de Carolina do Nascimento de Sousa.

Revisão de Lauro Reis. Imagem: pexels.com.

How can a novel be analyzed and

studied when removed from its

historical and literary context? This

essay aims to demonstrate that the key

to complete and utter understanding of

even the most concealed aspects of a

literary piece is indeed to look at it from

a contextualized perspective. As is the

case with some specific features of Jane

Eyre (1847), oftentimes authors can

stray from their era’s conventions.

However, in the instance of Charlotte

Brontë, most of the novel is aligned

with what is expected from Victorian

Literature in the nineteenth century,

from the feminist narrative to religious

plurality. Nevertheless it is a staple for

harboring genres such as Realism and

elements from Gothic Fiction.

In order to contextualize literary works

during the nineteenth century it is

crucial to understand how, in a short

period of time, Britain underwent a

series of progresses and changes in

paradigm. The themes that once

inspired the medieval word ‘gothic’

were in this period modernized and

adapted to an age of religious

questioning, advances in medicine and,

overall, the desire to know more.

This desire is well described as a new

sort of epistemology that is no longer

held back by the restraints of religion,

as explained by Michael Timko’s article.

« For although all ages are ages of

transition, never before had men

thought of their own time as an era of

change from the past to the future (…)

Second, this was the period in which

epistemological rather than

metaphysical concerns began to

predominate (…) ».(1)

Experience and knowledge freed from

metaphysical rules led to the advances

this period is known for, considering

formal education advances never before

seen that led to a reform of social

norms rarely questioned before. The

questions arise? as a result of a

collective need to an individual sense of

identity that Timko identifies as self-

(2).

consciousness A better sense of self

resulted in the search for its true

essence and, particularly in literature,

this search resulted in the need to

perfect how that is portrayed. The act of

describing and narrating objects, people

and thoughts in a realistic manner

paved way for most of Victorian literary

works of this century, especially

novels.

Despite the relevance Realism had on

the literary scene, for many authors, it

was integrated with a twist. Although

Gothic art first made its appearance

during medieval times mostly through

architecture, it later resurged as a

literary genre during the second half of

the eighteenth century. During the

Victorian Era it gained a new meaning.

There was a great amount of realistic

novels the nineteenth century saw

published and curiously enough a big

number of them are actually hybrids

(3).

between the two genres It is

interesting to observe how the desire to

narrate things exactly how they happen

sets an expectation for a realistic novel

that, as is the case with Jane Eyre (1847),

will fall short of realistic expectations

and actually happen to integrate a

series of Gothic elements.

It is interesting to explain the

Victorian’s reinterest in Gothic Fiction

when considering the changes and

advances of the century.

In an age of increasing religious

uncertainty, spiritualistic experiment

and imperial fears, Gothic provided a

safe space for both ancient demons and

modern psychological anxiety. Writers

were able to privilege mystery over

explanation (…) capturing the dark side

of the Victorian soul in all its energetic

and self-revealing doubt. (4)

The themes previously identified as

traditionally Gothic « (…)ruined castles,

helpless heroines, and evil villains (…) »

(5) shifted towards elements common to

the Victorian society. The settings were

recognizable, the moral values and

beliefs as well as the mindsets of the

characters were the same as the

average Victorian’s and that altogether

was the key to how engaging Gothic

fiction became.(6)

As discussed before, the Gothic

underwent a series of changes that

resulted in its progressive adaptation to

Victorian society. This adaptation

resulted from a series of societal

changes that included women’s fight

for equality not only for academic

opportunities but also inside their own

families. While focusing on better

developing their own particular

interests, many concepts such as

“house wife” or “nuclear family” simply

started to lose the meaning and

importance they once had.(7)

To what do we owe the alteration of a

paradigm that was centuries old?

Paradigms change according to the rate

of a society’s advance. In the nineteenth

century the key advance was scientific

discovers. Theories as important as

Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species

led people from all walks of life to

question their beliefs, especially when

it came to the Old Testament and how

Christianity explained the way humans

came to be. As it has always been, the

more people had access to education

the more they had a general capacity to

question established beliefs, this being

one of the reasons women fought to

access formal and higher education.

Although the veracity of the Bible was

oftentimes questioned, religion is

nevertheless an important staple

during the Victorian era. Many no

longer identified with common

Christian values and became atheists

(8), others turn to a different conviction,

Spiritualism. It consists on the belief

that some humans have the ability to

communicate with the dead and

therefore establish ethereal

connections. It is interesting that in a

century that saw the birth of progresses

like the Periodic Table, there was a

tendency to strain from science into

spiritualism and the partial desertion

of organized religion. In Spiritualism,

Science and Atavism, Charlotte Barret

theorizes the connection to be a

consequence of the « (…) abandonment

of conventional religion. In the search

for meaning, people were prepared to

suspend reason. »

Spiritualism played an important role

in contributing to the themes of Gothic

Fiction. The common themes changed

from the previous enumeration of

medieval elements such as castles and

battles to an emotional realm that

deeply represented the advances of

medicine, specifically in psychology

and the function of the mind.

Continuous discoveries were relevant in

the sense that they revealed how much

is still to be studied. The Gothic

proliferated with the mindset of

intellectual uncertainty and doubt.

Spiritualism was, in a way, a form of

comfort to fill in the void caused by

religion and the hard truth that

knowledge continuously improved

itself.

This newfound interest in the occult

inspired many of the literary pieces of

the nineteenth century that each

represent not only the impact of Gothic

Spiritualism but also how it mixed with

realism. Charles Dickens’s ghost in A

Christmas Carol (1843), the ever-

changing painting of The Picture of

Dorian Gray (1890), Bram Stoker’s

Dracula terrorizing England (1897), the

supernatural study of anatomy in Mary

Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), and the

many hauntings of Charlotte Brontë’s

Jane Eyre (1847) are just some examples

of the novels that illustrated the plural

religious and spiritual beliefs of the

nineteenth century.

The topics and elements that define

Jane Eyre as a Realistic novel with a

Gothic and Spiritualistic antilogy are

aligned not only with the Victorian

religious and scientific beliefs but also

Charlotte Brontë’s own.

The fact that the novel integrates

several distinct religious threads, some

hints at supernaturalism but at the

same time skepticism, is a result of the

author’s multiple influences and ideas.

As discussed before, the nineteenth

century was a decisive period in the

matter of faith and religion and the

plurality of religious discourses during

this era is the key to understanding

how Charlotte Brontë combines

Calvinism, Evangelism and

Spiritualism in the same novel without

it losing reliability. (9)

Religion is present all throughout the

novel, from being enforced on the girls

(10)

at Lowood to St John’s proposal to

Jane. The idea that the plurality of

faiths of the century was represented in

the novel is well illustrated in the

comparison between characters

explored in The Merging of

Spiritualities: Jane Eyre as Missionary of

Love. Even when only considering

Christianity, the essay exemplifies how

Mr. Brocklehurst, St John Rivers and

Helen Burns are the pinnacle of

religious representation for Jane Eyre

and how distinct this representation is.

Helen is Jane’s lifeline from the

oppressions of Mr. Brocklehurst. It is

discussed how the author grew up

surrounded by many religious

(11),

influences namely an Anglican

father, where she might have gotten

the inspiration to create Helen’s

character in the religious realm.

Writing Mr. Brocklehurst as

emotionally abusive and strict was

Charlotte’s own way of criticizing what

she considered to be the absurd

Calvinistic doctrine of predestination

and the belief that individual faith is

established regardless of one’s actions

through life: « Further evidence of

Brocklehurst’s Calvinism is his reliance

on the doctrines of innate human

corruption » (12).

The author strongly denounced the

belief in « next‐worldly over this‐

(13)

worldly rewards and punishments »

as well as even biblical conceptions of

the nuclear family and the

representation of what a woman’s roles

should be, and that led to some

critiques of Jane Eyre as opposing

Christian values.

Helen was the embodiment of

endurance, love and patience. Helen

served as one of the key characters for

Jane’s development and maturity. Her

calm demeanor puzzled Jane’s childlike

behavior and temperament, it also

helped form many of the behaviors and

tolerance Jane has as an adult. Helen’s

promise of « (…) an invisible world and

a kingdom of spirits (…) » [JE: VIII, p. 78

doesn’t make sense to Jane yet, but as

stated before, Helen’s influence on Jane

is much clearer after she reaches

adulthood and something to wonder is

whether the encryption on Helen’s

gravestone is proof that Jane might

have reached her own personal belief in

the concept of Heaven, as Helen did, as

a place where she could reach ultimate

happiness. « (…) a grey marble tablet

marks the spot, inscribed with her

name, and the work ‘Resurgam’. » [JE:

VI, p. 94] (14)

St John Rivers is another predominant

religious figure in Jane’s life, once again

demonstrating the downsides of the

Christian mentality. Suffering from

false righteousness, it is clear how,

when Jane does not do as she is told, by

turning down his marriage proposal, «

he ultimately proves to possess the

most negative qualities of Brocklehurst

(15)

» and turns to punishment as a way

to manipulate Jane into a loveless

marriage.

What stops Jane from accepting St

John’s proposal is the first and only

manifestation of the supernatural in

the novel. Charlotte Brontë hints at

various sinister happenings since Jane’s

childhood. The events Jane experiences

in the Red Room are explained by J.

Jeffrey, in The Merging of Spiritualities:

Jane Eyre as Missionary of Love, as the

manifestation of “childhood trauma”

and abuse and it can also be associated

to Jane’s need to feel the presence of a

loved one, like Mr. Reed. The matter of

the supernatural can be seen also in the

creatures that Jane is named after by

Rochester – such as “troubled spirit”,

“fairy”, “specter” and “elf”. Jane’s

hauntings materialize and accompany

her in the way that the Red Room is

parallel to the happenings of the Third

Floor of Thornfield Hall.

The most relevant manifestation of the

Gothic in Brontë’s work is the life and

portrayal of Bertha Mason. She first

appears as laugh, « (…) in its low,

syllabic tone, and terminated in an odd

murmur. » [JE: XI, p. 124].

And for some time, there aren’t any

humanlike characteristics used to

describe her. Upon discovering Bertha

as a caged human and until her death,

for a brief moment, until she is « (…)

dead as the stones on which her brains

and blood were scattered. »

[JE: XXXVI, p. 519]

Jane feels guilt after realizing Bertha’s

sanity was stripped from her after

being encaged by her husband-to-be.

Bertha represents “the stereotypes that

have plagued Gothic anti-heroines”(16) of

a woman who abandons conventions

regarding sexual liberation to a point of

being considered animalistic, to being

pitied for being mentally ill, to being

described as organic matter. The fact

that her sin is carnal and promiscuous

makes for the fact that she is

oftentimes described as “vampiric” and

“cannibalistic”, and she contrasts Jane’s

“small”, “white” and childlike”

bourgeois appropriate demeanor(17). The

mad wife’s ominous warning to Jane is

made by ripping her wedding veil in

half, but it is not the only presage of her

and Rochester’s interrupted marriage.

The Gothic elements in Jane Eyre such

as Jane’s own dreams, her

premonitions and even the natural

elements are often a warning as to

what is to come to the characters’ lives,

especially Jane’s. The night Rochester

proposes, underneath the chestnut tree,

has a strong manifestation of a gothic

omen that uses the natural elements to

sustain the novel’s extramundane

atmosphere. Jane describes how the

weather was opposing their encounter.

« (…) we were all in shadow (…). While

wind roared in the laurel walk, and

came sweeping over us. » [JE: XXIII, pg.

307]

Eventually, long before Bertha could

tore Jane’s veil in half, « (…) the great

horse chestnut at the bottom of the

orchard had been struck by lightning in

the night, and half of it split away. »

[JE: XXIII, pg. 308].

Despite Charlotte Brontë’s hinting at the

supernatural nature of Bertha, Jane’s

premonitions and the Red Room’s

occurrences, unlike some of the most

notorious novels of the nineteenth

century’s literary scene, all of these

events are scientifically explained and

debunked; all but one. The telepathic

phenomenon that is beyond scientific

explanation is responsible for impeding

Jane’s acceptance of St John’s proposal

and her eventual return to Thornfield

Hall. The question remains as to why

the author clarified every other event

rationally, but kept this one impossible

to decipher as anything other than

coincidental or paranormal. J. Jeffrey

offers a good explanation,

While she finds it necessary to use the

supernatural as a vehicle for bringing

Christian discourse in contact with the

discourse of spiritual love, revising the

former by the latter, she then feels

compelled to deny the supernatural,

leaving it (…) as the excluded term. (18)

[Notes]

1. Timko, Michael. “The Victorianism of

Victorian Literature.” New Literary

History, vol. 6, no. 3, 1975, pp. 610,

first paragraph. (Full citation of the

article in the list of references).

2. Further regarding the above article’s

question of self-consciousness “The

epistemological and Darwinian

awareness of the Victorians must be

seen, then, in terms of the changed

nature of the “imaginative

awareness” affected by “experience”;

and two key terms need to be

reexamined. (…) “Self-consciousness”

and, of course, “nature”. Self-

consciousness has always been

regarded as one of the chief

characteristics of nineteenth-century

writing (…).” Pp. 613.

3. Some examples enumerated by

Julian Thompson in Victorian Gothic;

An Introduction: “The results can be

seen in Tennyson’s fairy poems of

the early 1830s, Charlotte Brontë

hiding guilty secrets in the Gothic

towers of Thornfield in Jane

Eyre (1847), and the way Edgar Allan

Poe’s ‘The Pit and the Pendulum’

(1842) cruelly reconstructs the

torture-chambers of the Spanish

Inquisition.”

4. Victorian Gothic: An Introduction by

Julian Thompson

5. Spiritualism, Science and Atavism by

Charlotte Barrett

6. Further clarified in Barret’s essay

Spiritualism, Science and Atavism:

“(…) to situate the tropes of the

supernatural and the uncanny

within a recognizable environment.

This brings a sense of verisimilitude

to the narrative, and thereby renders

the Gothic features of the text all the

more disturbing.”

7. A Companion to the Brontës, p. 34.:

“Each novel examines various Gothic

feminist strategies— rejection of

motherhood, control of the

patriarchal estate, struggle with

tyrannous religious forces,

overthrow of the suffocating and

claustrophobic nuclear family, the

celebration of education or art for

women (…).”

8. Charlotte Brontë’s own

dissatisfaction as stated in A

Companion to the Brontës, p. 433. :

“The twentieth century saw feminist

readers like Sandra M. Gilbert and

Susan Gubar famously seizing on

Charlotte’s “rebellious feminism,”

with its apparently “‘irreligious’

dissatisfaction with the social order”.

You might also like

- Whitall N. Perry, Marco Pallis, Huston Smith - The Spiritual Ascent A Compendium of The World's WisdomDocument2,141 pagesWhitall N. Perry, Marco Pallis, Huston Smith - The Spiritual Ascent A Compendium of The World's WisdomCaio Cardoso100% (3)

- The Crisis of Reason (Burrow) PDFDocument370 pagesThe Crisis of Reason (Burrow) PDFFrancisco Reyes100% (1)

- Heiland D. - Gothic and The Generation of IdeasDocument18 pagesHeiland D. - Gothic and The Generation of IdeasStanislav GladkovNo ratings yet

- A List of John Meadows Programs Sstmodpdf CompressDocument3 pagesA List of John Meadows Programs Sstmodpdf CompressQuake11No ratings yet

- Characteristics of Victorian LiteratureDocument2 pagesCharacteristics of Victorian LiteratureDabe Zine81% (16)

- Aristotle's Children: How Christians, Muslims, and Jews Rediscovered Ancient Wisdom and Illuminated the Middle AgesFrom EverandAristotle's Children: How Christians, Muslims, and Jews Rediscovered Ancient Wisdom and Illuminated the Middle AgesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Origins of the English Novel, 1600–1740From EverandThe Origins of the English Novel, 1600–1740Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Flex UK - September 2018 PDFDocument148 pagesFlex UK - September 2018 PDFQuake11100% (1)

- Flex USA July-August 2017Document235 pagesFlex USA July-August 2017Quake11100% (2)

- Victorian NovelDocument14 pagesVictorian Novelluluneil100% (1)

- 396 1542 1 PBDocument7 pages396 1542 1 PBFlorentina TeodoraNo ratings yet

- Sacred Tears: Sentimentality in Victorian LiteratureFrom EverandSacred Tears: Sentimentality in Victorian LiteratureRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Victorian AgeDocument7 pagesVictorian AgeKris Belea100% (2)

- Man and the Divine: New Light on Man's Ancient Engagement with God and the History of ThoughtFrom EverandMan and the Divine: New Light on Man's Ancient Engagement with God and the History of ThoughtNo ratings yet

- A Catholic Approach To HistoryDocument18 pagesA Catholic Approach To HistoryLuis FelipeNo ratings yet

- Topic 50 Victorian NovelDocument5 pagesTopic 50 Victorian NovelCris BravoNo ratings yet

- Hayden White A Portrait in Seven PosesDocument25 pagesHayden White A Portrait in Seven Posespopmarko43No ratings yet

- Hobbit Virtues: Rediscovering J. R. R. Tolkien's Ethics from The Lord of the RingsFrom EverandHobbit Virtues: Rediscovering J. R. R. Tolkien's Ethics from The Lord of the RingsRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Survey The Prominent Literary Trends of The Victorian Age.Document7 pagesSurvey The Prominent Literary Trends of The Victorian Age.নিজন্ম সূর্য89% (9)

- What Are The Main Features of PostmodernismDocument4 pagesWhat Are The Main Features of PostmodernismSMCNo ratings yet

- About ModernismDocument86 pagesAbout Modernismmivascu23No ratings yet

- Legacy of Westcott & Hort (& The Occult Revival)Document27 pagesLegacy of Westcott & Hort (& The Occult Revival)Jesus LivesNo ratings yet

- AbstractDocument21 pagesAbstractInma Puntas SerranoNo ratings yet

- Political Factors As The Catalyst of The EnlightenmentDocument5 pagesPolitical Factors As The Catalyst of The EnlightenmentLaura Guo (Han)No ratings yet

- Danny PraetDocument10 pagesDanny PraetskimnosNo ratings yet

- Myths History and The Construction of NaDocument10 pagesMyths History and The Construction of NarojetasatNo ratings yet

- Aspell, Patrick J - Medieval Western PhilosophyDocument350 pagesAspell, Patrick J - Medieval Western Philosophyapi-3738033No ratings yet

- How Are Gothic Themes Shown in British Literature?Document9 pagesHow Are Gothic Themes Shown in British Literature?api-444969952No ratings yet

- Sanders - U3 Late Victorian and Edwardian LiteratureDocument12 pagesSanders - U3 Late Victorian and Edwardian LiteratureMelanie HadzegaNo ratings yet

- Christopher S. Celenza. The Lost Italian Renaissance - Humanists, Historians, and Latin's Legacy (Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 58, Issue 2) (2005)Document2 pagesChristopher S. Celenza. The Lost Italian Renaissance - Humanists, Historians, and Latin's Legacy (Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 58, Issue 2) (2005)Joshua AlfaroNo ratings yet

- 01 Church - of - England - Spiritualism - and - The - Decline - of - Religious - Belief PDFDocument17 pages01 Church - of - England - Spiritualism - and - The - Decline - of - Religious - Belief PDFExalumnos Instituto AlonsodeErcillaNo ratings yet

- Victorian Literature Research Paper TopicsDocument7 pagesVictorian Literature Research Paper Topicsnbaamubnd100% (1)

- Elias MetahistoricalRomanceDocument15 pagesElias MetahistoricalRomanceMoh FathoniNo ratings yet

- The Stoic View of LifeDocument17 pagesThe Stoic View of LifeCarlos IsacazNo ratings yet

- Invisible Worlds: Death, Religion And The Supernatural In England, 1500-1700From EverandInvisible Worlds: Death, Religion And The Supernatural In England, 1500-1700Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Ethics through Literature: Ascetic and Aesthetic Reading in Western CultureFrom EverandEthics through Literature: Ascetic and Aesthetic Reading in Western CultureRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Age of Enlightenment Influencing Neoclassicism PDFDocument9 pagesAge of Enlightenment Influencing Neoclassicism PDFvandana1193No ratings yet

- Fantasia MedievalDocument8 pagesFantasia MedievalDaniel WolterNo ratings yet

- Gothic LiteratureDocument5 pagesGothic Literatureandrew irunguNo ratings yet

- Modes of Faith: Secular Surrogates for Lost Religious BeliefFrom EverandModes of Faith: Secular Surrogates for Lost Religious BeliefNo ratings yet

- Literature Test Revision NotesDocument4 pagesLiterature Test Revision Notesbryan6920No ratings yet

- Review PaperDocument4 pagesReview PaperChristian AlfornonNo ratings yet

- Intro The Victorian PeriodDocument7 pagesIntro The Victorian Periodabeer.hussien1296No ratings yet

- Scared Monsters: The Gothic Nineteenth Century and The Theology of EvilDocument30 pagesScared Monsters: The Gothic Nineteenth Century and The Theology of EvilBijaylaxmi Sahoo100% (1)

- Jordan, Michael - Myths of The World, A Thematic EncyclopediaDocument228 pagesJordan, Michael - Myths of The World, A Thematic Encyclopediamas2004100% (1)

- EarnestnessDocument4 pagesEarnestnessnicole91403No ratings yet

- History Compass - 2022 - Milne Smith - Gender and Madness in Nineteenth Century BritainDocument10 pagesHistory Compass - 2022 - Milne Smith - Gender and Madness in Nineteenth Century BritainLaura MoreiraNo ratings yet

- (The Sociology of Religion) The SAGE Handbook of Sociology (Craig Calhoun, Chris Rojek and Bryan S. Turner)Document18 pages(The Sociology of Religion) The SAGE Handbook of Sociology (Craig Calhoun, Chris Rojek and Bryan S. Turner)nev.thomas96No ratings yet

- MythologyDocument4 pagesMythologymikasaackermannn23No ratings yet

- The Lotus and LionDocument287 pagesThe Lotus and Lionsd76123No ratings yet

- Hayden White Narrative DiscourseDocument66 pagesHayden White Narrative DiscourseAmalia IoneLaNo ratings yet

- Essay - Experiencing EnculturationDocument8 pagesEssay - Experiencing EnculturationIsha NisarNo ratings yet

- Wilkie Collins, The Woman in WhiteDocument6 pagesWilkie Collins, The Woman in WhiteAnik KarmakarNo ratings yet

- Boethius and SophiaDocument20 pagesBoethius and SophiaRosa.MarioNo ratings yet

- JV CultDocument10 pagesJV Cultmingeunuchbureaucratgmail.comNo ratings yet

- The Victorian Spirit of UncertaintyDocument15 pagesThe Victorian Spirit of UncertaintyVarunVermaNo ratings yet

- Bradshaw. On UtopiaDocument28 pagesBradshaw. On UtopiaCarlos VNo ratings yet

- Kelley 2005Document14 pagesKelley 2005Gabriel CidNo ratings yet

- Bevir-Historicism, Human Sciences Victorian BritainDocument20 pagesBevir-Historicism, Human Sciences Victorian BritainrebenaqueNo ratings yet

- Brochure RESIDENCES Legacy F&C Low Res CompressedDocument31 pagesBrochure RESIDENCES Legacy F&C Low Res CompressedQuake11No ratings yet

- Finalmente CaralhoDocument1 pageFinalmente CaralhoQuake11No ratings yet

- Voynich Manuscript PDFDocument209 pagesVoynich Manuscript PDFQuake11100% (2)

- Bell and Another Appellants Lever Brothers, Limited, And!Document1 pageBell and Another Appellants Lever Brothers, Limited, And!Quake11No ratings yet

- Cubicost Tas & TRB Elementary Quiz - AnswerDocument9 pagesCubicost Tas & TRB Elementary Quiz - AnswerChee HernNo ratings yet

- Expect Respect ProgramDocument2 pagesExpect Respect ProgramCierra Olivia Thomas-WilliamsNo ratings yet

- L2 - Cryptococcus NeoformansDocument44 pagesL2 - Cryptococcus Neoformansdvph2fck6qNo ratings yet

- Great by Choice - Collins.ebsDocument13 pagesGreat by Choice - Collins.ebsShantanu Raktade100% (1)

- Ra 10868Document11 pagesRa 10868Edalyn Capili100% (1)

- The Literary Comparison Contrast EssayDocument7 pagesThe Literary Comparison Contrast EssayThapelo SebolaiNo ratings yet

- Company Profile: TML Drivelines LTD (Tata Motors, Jamshedpur)Document5 pagesCompany Profile: TML Drivelines LTD (Tata Motors, Jamshedpur)Madhav NemalikantiNo ratings yet

- BBB October 2023 Super SpecialsDocument4 pagesBBB October 2023 Super Specialsactionrazor38No ratings yet

- HorrorDocument25 pagesHorrorYasser Nutalenko100% (2)

- World Red Cross DayDocument17 pagesWorld Red Cross DayAshwani K SharmaNo ratings yet

- 8.b SOAL PAT B INGGRIS KELAS 8Document6 pages8.b SOAL PAT B INGGRIS KELAS 8M Adib MasykurNo ratings yet

- GenEd - Lumabas Jan 2022Document4 pagesGenEd - Lumabas Jan 2022angelo mabulaNo ratings yet

- The African Essentials - Presentation - O - 2019Document34 pagesThe African Essentials - Presentation - O - 2019Fatima SilvaNo ratings yet

- Anatomy GuDocument13 pagesAnatomy Gujefel umarNo ratings yet

- The Wholly BibleDocument10 pagesThe Wholly BibleFred_Carpenter_12No ratings yet

- Mauro Giuliani: Etudes Instructives, Op. 100Document35 pagesMauro Giuliani: Etudes Instructives, Op. 100Thiago Camargo Juvito de Souza100% (1)

- 11 Ultimate Protection Video Charitable Religious TrustsDocument12 pages11 Ultimate Protection Video Charitable Religious TrustsKing FishNo ratings yet

- Hot Vs Cold Lab Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesHot Vs Cold Lab Lesson Planapi-497020000No ratings yet

- Doctorine of Necessity in PakistanDocument14 pagesDoctorine of Necessity in Pakistandijam_786100% (9)

- Book SoftDocument318 pagesBook SoftBrian Takudzwa MuzembaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Alternatives NotesDocument10 pagesComparison of Alternatives NotesLibyaFlowerNo ratings yet

- Azkoyen Technical Guide AN8000Document38 pagesAzkoyen Technical Guide AN8000pastilhasNo ratings yet

- Sun Pharma ProjectDocument26 pagesSun Pharma ProjectVikas Ahuja100% (1)

- Effect of Bolt Pretension in Single Lap Bolted Joint IJERTV4IS010269Document4 pagesEffect of Bolt Pretension in Single Lap Bolted Joint IJERTV4IS010269ayush100% (1)

- Draft Local Budget Circular Re Grant of Honorarium To SK Officials - v1Document4 pagesDraft Local Budget Circular Re Grant of Honorarium To SK Officials - v1rodysseusNo ratings yet

- Maribelle Z. Neri vs. Ryan Roy Yu (Full Text, Word Version)Document11 pagesMaribelle Z. Neri vs. Ryan Roy Yu (Full Text, Word Version)Emir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Note On F3 SC C2 TransportationDocument4 pagesNote On F3 SC C2 Transportationgan tong hock a.k.a ganosNo ratings yet

- FSA Enrollment Form - English PDFDocument1 pageFSA Enrollment Form - English PDFLupita MontalvanNo ratings yet

- (Promotion Policy of APDCL) by Debasish Choudhury: RecommendationDocument1 page(Promotion Policy of APDCL) by Debasish Choudhury: RecommendationDebasish ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- By Laws Amended As at 1 July 2022 PDFDocument364 pagesBy Laws Amended As at 1 July 2022 PDFJING YI LIMNo ratings yet