Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2015 Serbia Kosovo

2015 Serbia Kosovo

Uploaded by

Florian BieberCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Pope Francis Apologizes To Indigenous Peoples For Grave Sins' of Colonialism - Indian Country Media NetworkDocument2 pagesPope Francis Apologizes To Indigenous Peoples For Grave Sins' of Colonialism - Indian Country Media Network:Aaron :Eil®©™86% (7)

- Between Serb and Albanian A History of KosovoDocument331 pagesBetween Serb and Albanian A History of KosovoIgor Spiric100% (1)

- The Silent Unseen by Amanda McCrinaDocument22 pagesThe Silent Unseen by Amanda McCrinaMacmillan KidsNo ratings yet

- Kosovo, The Declaration of IndependenceDocument17 pagesKosovo, The Declaration of IndependenceKajjea KajeaNo ratings yet

- ABAZI, E. A New Power Play in The Balkans-Kosovo's IndependenceDocument14 pagesABAZI, E. A New Power Play in The Balkans-Kosovo's IndependenceGrigor BoykovNo ratings yet

- Article - Kosovo's Declaration of IndependenceDocument8 pagesArticle - Kosovo's Declaration of IndependenceKaye MendozaNo ratings yet

- DIALOGUE KOSOVO - SERBIANormalization of Reports or Mutual Recognition? Bekim Baliqi, PH.DDocument8 pagesDIALOGUE KOSOVO - SERBIANormalization of Reports or Mutual Recognition? Bekim Baliqi, PH.DBekimNo ratings yet

- Self Determination Recognition and The PDocument28 pagesSelf Determination Recognition and The PKazorlaMuletaNo ratings yet

- No 50 51 RrecajDocument6 pagesNo 50 51 RrecajDardan AbaziNo ratings yet

- Building A New State and A New Society in Kosovo Roland Gjoni FinalDocument13 pagesBuilding A New State and A New Society in Kosovo Roland Gjoni FinalRoland GjoniNo ratings yet

- CFR - Kosovo Future StatusDocument6 pagesCFR - Kosovo Future StatusMrkva2000 account!100% (1)

- The Trouble With Kosovo: DR Simon DukeDocument18 pagesThe Trouble With Kosovo: DR Simon Dukekayex44816No ratings yet

- Succession, Kosovo Case, MA. Shkodran REXHAJ, MA. Armend KRASNIQIDocument16 pagesSuccession, Kosovo Case, MA. Shkodran REXHAJ, MA. Armend KRASNIQIArmend KrasniqiNo ratings yet

- Kosovo Foreign Policy Weller Final EnglishDocument21 pagesKosovo Foreign Policy Weller Final EnglishKoha Net100% (1)

- Odbačene Tužbe Za GenocidDocument43 pagesOdbačene Tužbe Za GenocidAndrejaKošanskiHudikaNo ratings yet

- Cottey KosovoWarPerspective 2009Document17 pagesCottey KosovoWarPerspective 2009Elene KobakhidzeNo ratings yet

- A Study of International Conflict Management With An Integrative Explanatory Model: The Case Study of The Kosovo ConflictDocument11 pagesA Study of International Conflict Management With An Integrative Explanatory Model: The Case Study of The Kosovo ConflictpedalaroNo ratings yet

- Stroschein Making or Breaking KosovoDocument20 pagesStroschein Making or Breaking KosovoΓιώτα ΠαναγιώτουNo ratings yet

- Reading Response, Ker-LindsayDocument3 pagesReading Response, Ker-LindsayTeun LitjensNo ratings yet

- Cazul KosovoDocument57 pagesCazul KosovoTodor Eleonora100% (1)

- Cap5 Kosovo ENG Oct9Document40 pagesCap5 Kosovo ENG Oct9Nutsa TsamalashviliNo ratings yet

- The Kosovo CaseDocument24 pagesThe Kosovo CaseAlinaIlieNo ratings yet

- Univerza V Ljubljani Fakulteta Za Družbene Vede: Martinič Sandra 21080320Document13 pagesUniverza V Ljubljani Fakulteta Za Družbene Vede: Martinič Sandra 21080320Sandra MartiničNo ratings yet

- SAIS FPI, WWICS Report, From Crisis To Convergence, Strategy To Tackle Balkans InstabilityDocument67 pagesSAIS FPI, WWICS Report, From Crisis To Convergence, Strategy To Tackle Balkans InstabilityСињор КнежевићNo ratings yet

- Symposium: Recent Developments in The Practice of State RecognitionDocument30 pagesSymposium: Recent Developments in The Practice of State RecognitionS. M. Hasan ZidnyNo ratings yet

- Kosovo & UsDocument15 pagesKosovo & Usrimi7alNo ratings yet

- Neha Sachdeva, 9078Document3 pagesNeha Sachdeva, 9078Ved BhaskerNo ratings yet

- CERES Country Profile - KosovoDocument18 pagesCERES Country Profile - KosovoCenter for Eurasian, Russian and East European StudiesNo ratings yet

- HHRG 114 FA14 Wstate VejvodaI 20160315Document7 pagesHHRG 114 FA14 Wstate VejvodaI 20160315mercurio324326No ratings yet

- NEURALGIC HOTSPOTS AS AN OBSTACLE TO REGIONAL STABILITY? THE CASE OF NORTHERN KOSOVOerDocument13 pagesNEURALGIC HOTSPOTS AS AN OBSTACLE TO REGIONAL STABILITY? THE CASE OF NORTHERN KOSOVOerSandra MartiničNo ratings yet

- Xiv. Supervised IndependenceDocument5 pagesXiv. Supervised IndependenceSabin DragomanNo ratings yet

- Inner Problems Facing Kosovo: Ibid. IbidDocument4 pagesInner Problems Facing Kosovo: Ibid. Ibidnjomzamehani1503No ratings yet

- Jović - SlovenianCroatian Confederation ProposalDocument32 pagesJović - SlovenianCroatian Confederation ProposalJerko BakotinNo ratings yet

- Serbia's Non-Recognition of Kosovo's Independence Sets New Precedence in International LawDocument4 pagesSerbia's Non-Recognition of Kosovo's Independence Sets New Precedence in International LawJacinda ChanNo ratings yet

- The Transdniestrian Settlement Process - Steps Forward, Steps Back: The OSCE Mission To Moldova in 2005/2006Document20 pagesThe Transdniestrian Settlement Process - Steps Forward, Steps Back: The OSCE Mission To Moldova in 2005/2006Rafael DobrzenieckiNo ratings yet

- Kosovo & The UNDocument4 pagesKosovo & The UNharshtulsyan2703No ratings yet

- Comparative Analysis On Nagorno-Karabagh and KosovoDocument18 pagesComparative Analysis On Nagorno-Karabagh and KosovoMustafayevNo ratings yet

- Socialist YugoslaviaDocument3 pagesSocialist YugoslaviaJaksha87No ratings yet

- Muhamet Hamiti Interview Studies in Ethnicity and Nation All Ism Volume9 No2 2009Document10 pagesMuhamet Hamiti Interview Studies in Ethnicity and Nation All Ism Volume9 No2 2009Fjala e LireNo ratings yet

- Recognition of StateDocument6 pagesRecognition of StatetamtikoNo ratings yet

- The Vain Attempts of The European Community To Mediate in YugoslaviaDocument4 pagesThe Vain Attempts of The European Community To Mediate in YugoslaviaNICOLAS BUJAN CASTRONo ratings yet

- From The Carrington-Cutileiro Plan To W PDFDocument37 pagesFrom The Carrington-Cutileiro Plan To W PDFbbbNo ratings yet

- Kulenovic Sasa (2013), Temperanter - IV - 3-4, Kosovo's Changed Attitude Throughout Negotiations With BelgradeDocument71 pagesKulenovic Sasa (2013), Temperanter - IV - 3-4, Kosovo's Changed Attitude Throughout Negotiations With BelgradeSaša KulenovicNo ratings yet

- EU and Western Balkans ConflictDocument7 pagesEU and Western Balkans Conflictskribi7No ratings yet

- The Ahtisaari Plan and North KosovoDocument18 pagesThe Ahtisaari Plan and North KosovoArtan MyftiuNo ratings yet

- Can Crimea Claim Secession and Accession to Russian Federation in Light of Kosovo’S Independence?From EverandCan Crimea Claim Secession and Accession to Russian Federation in Light of Kosovo’S Independence?No ratings yet

- Ryngaert - Recognition of States2011Document24 pagesRyngaert - Recognition of States2011bhupendra barhatNo ratings yet

- Uva-Dare (Digital Academic Repository) : The Unfinished Trial of Slobodan Milošević: Justice Lost, History ToldDocument25 pagesUva-Dare (Digital Academic Repository) : The Unfinished Trial of Slobodan Milošević: Justice Lost, History ToldMladen MrdaljNo ratings yet

- The Kosovo CaseDocument21 pagesThe Kosovo CasePrerna SinghNo ratings yet

- Milanovic - 2014 - Arguing The Kosovo CaseDocument45 pagesMilanovic - 2014 - Arguing The Kosovo Casemiki7555No ratings yet

- Belgrade and Pristina: Lost in Normalisation?: by Donika Emini and Isidora StakicDocument8 pagesBelgrade and Pristina: Lost in Normalisation?: by Donika Emini and Isidora StakicRaif QelaNo ratings yet

- Accelerated Expansion of Nato Into The Balkans As A Consequence of Euro Atlantic DiscordDocument24 pagesAccelerated Expansion of Nato Into The Balkans As A Consequence of Euro Atlantic DiscordbiljanaNo ratings yet

- The Organization For Security and Co-Operation in Europe (OSCE)Document8 pagesThe Organization For Security and Co-Operation in Europe (OSCE)ribdsc23No ratings yet

- Van-Der-borgh - 2012 - Resisting International State Building in KosovoDocument13 pagesVan-Der-borgh - 2012 - Resisting International State Building in Kosovomiki7555No ratings yet

- Multi-Level Games: The Serbian Government's Strategy Towards Kosovo and The EU Under The Progressive PartyDocument23 pagesMulti-Level Games: The Serbian Government's Strategy Towards Kosovo and The EU Under The Progressive PartyBoris KaličaninNo ratings yet

- MacedoniaDocument17 pagesMacedoniaapi-413768025No ratings yet

- Xiii. Establishing A de Facto State Through An International ProcessDocument3 pagesXiii. Establishing A de Facto State Through An International ProcessSabin DragomanNo ratings yet

- Ups and Downs of The Operation Allied ForceDocument10 pagesUps and Downs of The Operation Allied ForceOndřej MelichaříkNo ratings yet

- Ex Injuria Jus Non Oritur, Ex Factis Jus Oritur, and The Elusive Search For Equilibrium After UkraineDocument31 pagesEx Injuria Jus Non Oritur, Ex Factis Jus Oritur, and The Elusive Search For Equilibrium After UkraineHamdi TuanNo ratings yet

- (UN Court Says Kosovo Independence Legal) - (Radio Free Europe - Radio Liberty © 2014)Document4 pages(UN Court Says Kosovo Independence Legal) - (Radio Free Europe - Radio Liberty © 2014)yannie11No ratings yet

- De Facto S Outh Ossetia Is Not Kosovo, Abkhazia-Georgia, Kosovo-Serbia, Parallel WorldDocument9 pagesDe Facto S Outh Ossetia Is Not Kosovo, Abkhazia-Georgia, Kosovo-Serbia, Parallel WorldarielNo ratings yet

- Editorial From Kenny KeeneDocument1 pageEditorial From Kenny Keeneapi-209483832No ratings yet

- The Black Panther Party Ten Point PlanDocument3 pagesThe Black Panther Party Ten Point PlanDäv OhNo ratings yet

- Organisation Chart NDMCDocument1 pageOrganisation Chart NDMCAr Ayoushika AbrolNo ratings yet

- Custom Legal MethodDocument20 pagesCustom Legal MethodLarry Coleman100% (2)

- 001 - ComplaintDocument26 pages001 - ComplaintThắng AnthonyNo ratings yet

- (WWW - Entrance-Exam - Net) - List of Schools in MumbaiDocument14 pages(WWW - Entrance-Exam - Net) - List of Schools in MumbaiSiddhesh KolgaonkarNo ratings yet

- Tertiary Learning Module: Mrs. Viriginia BorjaDocument6 pagesTertiary Learning Module: Mrs. Viriginia Borjajoniel ajeroNo ratings yet

- BS BuzzDocument6 pagesBS BuzzBS Central, Inc. "The Buzz"No ratings yet

- Amazon 2020Document1 pageAmazon 2020Lavish SoodNo ratings yet

- FOOTBALLDocument48 pagesFOOTBALLjaiscey valenciaNo ratings yet

- Part 4 International Transactions, Ch.14 Treaties, Character and Function of TreatiesDocument19 pagesPart 4 International Transactions, Ch.14 Treaties, Character and Function of TreatiesTemo TemoNo ratings yet

- Pagsulat NG BalitaDocument36 pagesPagsulat NG BalitaRasec NilotNa56% (9)

- Aerodynamics ProjectDocument45 pagesAerodynamics ProjectRj JagadeshNo ratings yet

- WEST INDIAN HURRICANE OF SEPTEMBER 1-12, 1900 - The Galveston Hurricane of 1900Document1 pageWEST INDIAN HURRICANE OF SEPTEMBER 1-12, 1900 - The Galveston Hurricane of 1900Gage GouldingNo ratings yet

- Gujarat Technological UniversityDocument1 pageGujarat Technological UniversityCode AttractionNo ratings yet

- Censorship in Saudi ArabiaDocument97 pagesCensorship in Saudi ArabiainciloshNo ratings yet

- Notes - Equal ProtectionDocument16 pagesNotes - Equal ProtectionArwella GregorioNo ratings yet

- Kelas: 1 A Khalid WALI KELAS: Siti Nurjanah, S. PD: Targetan Pembelajaran Hadits Semester 1Document54 pagesKelas: 1 A Khalid WALI KELAS: Siti Nurjanah, S. PD: Targetan Pembelajaran Hadits Semester 1Zalia Izzati AzkadinaNo ratings yet

- AdverbsDocument6 pagesAdverbsVanessa Rose L. PomantocNo ratings yet

- Aiims Rishikesh LoaDocument1 pageAiims Rishikesh LoaashkuchiyaNo ratings yet

- 7 Banko Filipino vs. BSPDocument1 page7 Banko Filipino vs. BSPmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- Karhfw - gov.in-JRO-Counseling of KPSC Selected Specialist, Dentist & GDMO For The Selection of PlacesDocument18 pagesKarhfw - gov.in-JRO-Counseling of KPSC Selected Specialist, Dentist & GDMO For The Selection of PlacesAnonymous AuJncFVWvNo ratings yet

- Counter Affidavit SampleDocument5 pagesCounter Affidavit Sampleonlineonrandomdays100% (6)

- Chicana Cyborg EssayDocument22 pagesChicana Cyborg EssayVileana De La RosaNo ratings yet

- Techniques of Free Throws in BasketballDocument2 pagesTechniques of Free Throws in BasketballNawazish FaridiNo ratings yet

- Aarav PatelDocument51 pagesAarav PatelShem GamadiaNo ratings yet

- Proprietry EstoppelDocument4 pagesProprietry Estoppelmednasrallah100% (1)

- FRM Epay Echallan PrintDocument1 pageFRM Epay Echallan PrintSanket PatelNo ratings yet

2015 Serbia Kosovo

2015 Serbia Kosovo

Uploaded by

Florian BieberCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2015 Serbia Kosovo

2015 Serbia Kosovo

Uploaded by

Florian BieberCopyright:

Available Formats

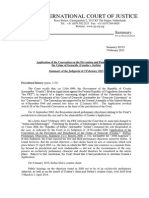

review of central and east european law

40 (2015) 285-319

brill.com/rela

The Serbia-Kosovo Agreements:

An eu Success Story?

Florian Bieber

Centre for Southeast European Studies, University of Graz, Graz, Austria

<florian.bieber@uni-graz>

Abstract

The agreements between Serbia and Kosovo—mediated by the eu since 2011—consti-

tute a major step toward the normalization of relations between the two countries

following Kosovo’s declaration of independence in 2008. They are also a test case for

eu mediation and its ability to utilize the prospect of accession to address protracted

conflicts. This article argues that the eu used creative ambiguity, as well direct pres-

sure, in facilitating a number of agreements between Serbia and Kosovo. While this

approach has yielded concrete results, it also bears risks, as the process was top-down

and, also, left considerable room for divergent and conflicting interpretations of key

provisions. This article will trace the negotiations and identify the particular features

of the process.

Keywords

conflict resolution – European Union – interethnic relations – Kosovo – Serbia

1 Introduction

The conflict in Kosovo and between Kosovan Albanians and Serbs over the

status of the province (and now a country) has been a defining feature of deep

tensions in the region: first in Yugoslavia and, subsequently, in Serbia and

Kosovo. These tensions preceded the conflicts for independence (and terri-

tory) in both Croatia and in Bosnia and Herzegovina by nearly a decade and

have continued to linger for almost two decades since the end of the war in

Bosnia in 1995. While tensions remain between Serbia and Croatia and within

Bosnia and Herzegovina, their international status is undisputed in the region

© koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2015 | doi 10.1163/15730352-04003008

0002622495.INDD 285 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

286 Bieber

(and beyond), and their borders are clear. The emergence of Kosovo as an

independent country has been incomparably more difficult and challenging

than that of the other states emerging from the former Yugoslavia. Not having

been a republic in Socialist Yugoslavia denied it the possibility to claim inde-

pendence on the grounds of the rules laid out by the Badinter Arbitration

Commission1 in 1991–1992 and based on the premise that Yugoslavia, as a state,

had dissolved and that its constituent units would become its successor

states.2 This transfer of the principle of uti possidetis from the post-colonial

context to Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union was not without its critics—among

them political scientists and legal scholars3—but it did prevail. No newly

crafted territorial unit received international recognition, and the two entities

of Bosnia and Herzegovina—the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and

Republika Srpska—only were recognized as units of a larger state. In fact, the

un Security Council explicitly rejected the independence of Republika Srpska

during the war.4

Kosovo’s claim for independence was first made in 1991, following the model

of Slovenia and Croatia, including an informal referendum.5 Unlike the for-

mer Yugoslav republics, Kosovo received no more international recognition or

acceptance than other comparable state projects that lacked the institutions

and legitimacy of a republic.6 Yet the war in 1998–1999 and subsequent inter-

national administration made independence the only plausible option for

Kosovo. Neither the international administrators and mediators nor, for that

1 The Badinter Arbitration Commission’s opinions 1–3 are reproduced in 3(1) European

Journal of International Law (ejil) (1992), 182ff., available at <http://ejil.oxfordjournals.org/

content/3/1/178.full.pdf+html>; and opinions 4–10 are in 4(1) ejil (1993), 74ff., available at

<http://ejil.oxfordjournals.org/content/4/1/66.full.pdf+html>.

2 Enver Hasani, “Uti Possidetis Juris: From Rome to Kosovo”, 27(2) The Fletcher Forum of World

Affairs (2003), 85–97, at 92–3.

3 Peter Radan, The Break-up of Yugoslavia and International Law (Routledge, London, 2002);

Steven R. Ratner, “Drawing a Better Line: Uti Possidetis and the Borders of New States”,

90(4) The American Journal of International Law (1996), 590–624; and Hurst Hannum, “Self-

Determination, Yugoslavia, and Europe: Old Wine in New Bottles”, 3(1) Transnational Law

and Contemporary Problems (1993), 58–69.

4 un Security Council, Resolution (16 November 1992) No.787, §3, available at <http://daccess

-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N92/723/03/IMG/N9272303.pdf?OpenElement>.

5 Wolfgang Petritsch, Karl Kaser, and Robert Pichler, Kosovo. Kosova. Mythen, Daten, Fakten

(Wieser Verlag, Klagenfurt, 1999), 189–190.

6 Be they in the former Yugoslavia, such as Republika Srpska, Krajina in Croatia, or Ilirida in

Macedonia, or their post-Soviet counterparts, such as Transnistria, South Osetiia, or

Abkhaziia. See Nina Caspersen, Unrecognized States: The Struggle for Sovereignty in the

Modern International System (Polity Press, London, 2011).

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 286 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

The Serbia-kosovo Agreements 287

matter, Serbia (or the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia) made any effort to offer

a valid alternative. Adem Demaçi’s idea of Balkania, some form of loose federa-

tion, was never seriously considered in Kosovo or Serbia. While, Kosovo’s inde-

pendence (or enhanced status within Yugoslavia until the late 1980s) was the

goal of the national movement of Kosovan Albanians from the early 1980s, this

goal was not shared by international mediators. Rather, as noted herein above,

it arose due to the absence of any plausible alternative. This ‘independence by

default’ also was striking because of the absence of a formal referendum7 on

independence, making Kosovo the only territory of former Yugoslavia—

together with Serbia—that did not vote on its status between 1991 and 2006 in

an internationally recognized referendum. Yet, its independence was probably

the least contested within the country itself (i.e., Kosovo) and, also, was better

prepared in advance of the declaration due to the Ahtisaari plan8 than in any

other successor state to the former Yugoslavia. In fact, the internationally

imposed institutional hurdles and requirements were greater than the con-

ditions for international recognition required from either Montenegro in

2006 or the other republics in 1991–1992. However, the very process of

Kosovo’s independence—not based on uti possidetis—and the opposition of

Serbia, from which it declared independence, meant that the process was con-

tested and difficult. In addition, it was further complicated by renewed ten-

sions between Russia and Western powers. While the non-recognition of

Kosovo often has been framed in the context of international law, domestic

political considerations often carried greater weight. It is, thus, unsurprising

that four out of the five countries9 among the eu member states not recogniz-

ing Kosovo either have real or imagined secessionist conflicts of their own.

7 This informal referendum was held in 1991, organized by the Kosovo ‘parallel institutions’

which were established in 1990–1991 by Kosovo Albanian parties following Serbia’s abolition

of Kosovo’s autonomy in 1989. More than 99 percent of those voting supported indepen-

dence, but the referendum result was not internationally recognized. Miranda Vickers,

Between Serb and Albanian: A History of Kosovo (Columbia University Press, New York, ny,

1998), 251; On the establishment and functioning of the parallel institutions see Howard

Clark, Civil Resistance in Kosovo (Pluto Press, London, Sterling, va, 2000), 95–119; and Vickers,

op.cit. supra, 259–264.

8 United Nations Office of the Special Envoy for Kosovo, “Comprehensive Proposal for the

Kosovo Status Settlement” (26 March 2007) S/2007/168/Add.1, available at <http://www

.unosek.org/unosek/en/statusproposal.html>.

9 Cyprus, Greece, Romania, Slovakia, and Spain. For more on the background of the countries

not recognizing Kosovo’s independence, see Kosovo Foundation for Open Society and British

Council, “Kosovo Calling” (2012), available at <http://kfos.org/kosovo-calling-position-papers

-on-kosovos-relation-with-eu-and-regional-non-recognising-countries/>.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 287 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

288 Bieber

Since Kosovo declared its independence in 2008, the number of countries

recognizing it has gradually increased. By 2015, some 112 countries had recog-

nized Kosovo, with the majority of them doing so in 2008–2009, followed by a

steady trickle that appears unperturbed by either Serbia’s request to the un

General Assembly, in the fall of 2008,10 for an advisory opinion from the

International Court of Justice (icj) or the opinion itself rendered by the icj in

mid-2010.11 Nevertheless, membership in key international organizations, in

particular in the un, has been elusive: not only does Serbia refuse to recognize

Kosovo but, also, key un Security Council members (Russia and China) like-

wise have opposed its diplomatic recognition.

A key obstacle (albeit not the only one) for Kosovo’s independence was

Serbia’s rejection of any status for Kosovo more than autonomy within Serbia.

This position was held by subsequent Serbian governments after 2000 and

enshrined in the 2006 Serbian Constitution.12 Serbia continued to adhere to

this policy after rejecting the 2007 Ahtisaari plan—proposing conditional

independence for Kosovo—and Kosovo’s 2008 declaration of independence.

While key Western countries took a position different from that of Serbia on

Kosovo’s independence, there was a reluctance among a number of those

countries to push Serbia to accept independence for fear (real or imaginary) of

derailing Serbia’s fragile democratization process after the fall of Milošević in

10 General Assembly, Press Release, “Backing Request by Serbia, General Assembly Decides

to Seek International Court of Justice Ruling on Legality of Kosovo’s Independence”

(8 October 2008) ga/10764, available at <http://www.un.org/press/en/2008/ga10764.doc

.htm>.

11 International Court of Justice, “Accordance with International Law of the Unilateral

Declaration of Independence in Respect of Kosovo (Request for Advisory Opinion)”

(22 July 2010), icj Reports (2010), 403, available at <http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/index.php?

p1=3&p2=4&case=141&p3=4>. See, also, “Who Recognized Kosova [sic] as an Independent

State?” (n.d.), available at <http://www.kosovothanksyou.com/>.

12 Ustav Rеpublikе Srbijе, Sluzhbeni glasnik Rеpublikе Srbijе (2006) No.98. The Constitution

declares in its preamble that:

“Considering also that the Province of Kosovo and Metohija is an integral part of

the territory of Serbia, that it has the status of a substantial autonomy within the

sovereign state of Serbia and that from such status of the Province of Kosovo and

Metohija follow constitutional obligations of all state bodies to uphold and protect the

state interests of Serbia in Kosovo and Metohija in all internal and foreign political

relations.”

Translation into English from the Serbian Parliament (n.d.), available at <http://www

.parlament.gov.rs/upload/documents/Constitution_%20of_Serbia_pdf.pdf>.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 288 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

The Serbia-kosovo Agreements 289

2000. Successive Serbian governments, since 2000, have failed to confront the

legacy of the wars of the 1990s and to address the question of wartime respon-

sibility, allowing for a more nuanced approach towards Kosovo.

2 International Mediation over Kosovo

The eu-led negotiations between Serbia and Kosovo since 2011—resulting in

the First Agreement on Principles, known as the 2013 Brussels Agreement13—

took place at the end of multiple international attempts to mediate a settle-

ment over Kosovo, first at Rambouillet and, later, through the final status talks

under un auspices presided over by former Finnish President Martti Ahtisaari.14

The challenge of both of those efforts was the rejection of the agreements by

the Serbian government. While the Milošević government never seriously

engaged in negotiations in Paris in the winter of 1999,15 his democratic succes-

sors did partake in the status talks in 2006–2007. However, the Serbian govern-

ment chose not to support the conclusion of Ahtisaari’s report to the un

Secretary General which proposed “conditional independence” for Kosovo. In

this way, the Ahtisaari report stood in contrast to Serbia’s position which

rejected any proposal that would have seen Kosovo become independent. The

main substance of Ahtisaari’s “Comprehensive Proposal” addressed an inter-

nal political and constitutional arrangement for Kosovo.16 It has been argued

that the self-government foreseen for Serbs in Kosovo—as well as the protec-

tion of Serbian Orthodox churches and monasteries—did reflect the media-

tors’ efforts to address concerns of the Serb community and of Serbia.17

13 “First Agreement of Principles Governing the Normalization of Relations” (19 April 2013),

available at <http://www.rts.rs/upload/storyBoxFileData/2013/04/20/3224318/Originalni%

20tekst%20Predloga%20sporazuma.pdf>.

14 They also include notable absences. Except for the 1991 Carrington Plan for Yugoslavia, no

international mediation between 1991 and 1995 explicitly dealt with Kosovo. The ignoring

of Kosovo—with the goal of facilitating a settlement in Croatia and Bosnia and

Herzegovina—contributed to the radicalization among Kosovan Albanians and the rise

of the Kosovo Liberation Army. See Marc Weller, Contested Statehood: Kosovo’s Struggle for

Independence (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2009), 41–54.

15 Petritsch, Kaser, and Pichler, op.cit. note 5, 278–351.

16 “Comprehensive Proposal for the Kosovo Status Settlement”, op.cit. note 8.

17 James Ker-Linday, Kosovo: The Path to Contested Statehood in the Balkans (ib Tauris,

London, 2009); and Weller, op.cit. note 14, 191–219.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 289 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

290 Bieber

Yet, the 2007 Ahtisaari plan was rejected not only by Serbia but, also, by

many Serbs in Kosovo; in particular by Serbs in the northern municipalities

adjacent to Serbia. The main reason for the rejection among Serbs was that it

was seen as ushering in independence for Kosovo.18 Thus, the north of

Kosovo—centered on the northern half of the city of Mitrovica—failed to

implement the plan and, instead, remained under direct Serbian control.

While the plan had offered a degree of local self-government, including

enhanced competences to North Mitrovica, the status quo best suited the elites

as well as most Serb citizens in northern Kosovo. Furthermore, the Ahtisaari

plan was largely viewed as being synonymous with independence, whereas the

details outlining the rights of Serbs in Kosovo were neglected and remained

largely unknown to Serbs in Kosovo.19 This rejection involved a complicated

combination of fear and resentment of Albanian domination in Kosovo, aver-

sion to Kosovo statehood, and practical advantages connected with the Serbian

state presence in Kosovo (e.g., employment in Serbian state institutions was at

considerably higher salaries than those offered by Kosovan institutions and

the de facto tax-free status of the region). The attitudes were different among

Serbs living south of the Ibar River, which separates the north from the rest of

Kosovo. Not living in geographically contiguous regions bordering Serbia,

these communities were more vulnerable and, also, more connected to

Kosovan Albanian society (albeit only precariously so). Furthermore, there

were few incidents in the south, where more than two-thirds of Serbs live. The

Ahtisaari plan offered the establishment of new Serb-majority municipalities

in the south that would have given Serbs a greater sense of demographic cer-

tainty and an ability to hand out jobs. In addition, and despite independence,

Serbian institutions have continued to operate in addition to the local admin-

istration working within the Kosovo framework.

The local context did not change significantly prior to eu mediation in 2011

and rather settled into an uneasy status quo. While many Serbs in the south

participated in the 2010 parliamentary elections, the elections were boycotted

in the north.20

18 Steve Crabtree, “Kosovo’s Albanians, Serbs Foresee No Compromises,” Gallup (23 May

2007), available at <http://www.gallup.com/poll/27661/kosovos-albanians-serbs-foresee

-compromises.aspx>.

19 Balkan Insight, “Kosovo Press Review” (27 April 2014), available at <http://www.balkanin

sight.com/en/article/kosovo-press-review-april-27-2012>.

20 European Union Election Expert Mission to Kosovo, Final Report (25 January 2011), 15–17,

available at <http://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/kosovo/documents/page_content/110125

_report_eu_eem_kosovo_2010_en.pdf>.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 290 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

The Serbia-kosovo Agreements 291

3 eu Mediation and State-Building

The European Union has a considerable record of mediating in former

Yugoslavia, although not always marked by success. In the 1990s, its efforts in the

region largely failed—being characterized by a lack of eu instruments, a lack of

unity, and a lack of enforcement mechanisms and experience.21 It was only once

the eu launched the Stabilization and Association Process22 in 2000 that its fur-

ther efforts in the region became embedded in the larger question of eu enlarge-

ment. Even if membership often seemed remote to many in the region, it could

become an incentive in the mediation process that had been impossible previ-

ously. Yet, it also created tensions between the more pragmatic considerations

of conflict resolution and the more stringent requirements for eu accession.

Thus, the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro was established under eu aus-

pices in 2002–2003 to both settle the dispute over the joint state between Serbia

and Montenegro and to postpone the status question of Kosovo.23 However, the

state union which it created lacked the institutional resources necessary to

engage effectively with the eu in accession discussions. For this reason, by early

2006, the European Commission had adopted a twin-track approach of negoti-

ating with Serbia and Montenegro separately and, thus, undermining the state

which the eu had helped to establish.24 Attempts to mediate in Bosnia and

Herzegovina met with even less success. The eu usually acted in concert with

the us, especially before 2003–2004. The efforts to reform the police failed under

the auspices of the eu and the High Representative,25 and the second attempt

21 See Josip Glaurdic, The Hour of Europe: Western Powers and the Breakup of Yugoslavia (Yale

University Press, New Haven, ct, 2011); and Richard Caplan, Europe and the Recognition of

New States in Yugoslavia (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007).

22 “Stabilisation and Association Process (sap)” (22 April 2015), available at <http://ec

.europa.eu/agriculture/enlargement/sap/index_en.htm>.

23 un Security Council Resolution (10 June 1999) No.1244 (available at <http://daccess-dds-

ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N99/172/89/PDF/N9917289.pdf?OpenElement>) linked the

status of Kosovo to the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (fry) and, even though Serbia

could have been designated Yugoslavia’s legal successor, the eu feared that a dissolution

of the fry would place Kosovo prematurely on the agenda. It was the riots in Kosovo in

2004 and the apparent reluctance of international officials to openly endorse indepen-

dence prior to the riots (including the un policy of “standards before status”) that forced

the status of Kosovo onto the international agenda.

24 Florian Bieber, “Building Impossible States? State-Building Strategies and eu Membership

in the Western Balkans”, 63(10) Europe-Asia Studies (2012), 1783–1802.

25 Daniel Lindvall, The Limits of the European Vision in Bosnia and Herzegovina (PhD thesis,

University of Stockholm, 2009).

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 291 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

292 Bieber

at constitutional reform (and the first initiated by the eu) also resulted in a

deadlock.26 These obstacles can be grouped into three categories:

First, while eu integration could have offered an incentive for parties to seek a

compromise, the prospect of membership remained remote (as highlighted

above). This meant that the reward was seen as being negligible in comparison

with apparent size of the trade-off sought. The eu also failed to offer tangible

interim measures to compensate for the distant nature of membership. Thus,

parties often could not agree upon a compromise (Bosnia and Herzegovina) or

sabotaged existing agreements (Serbia and Montenegro).

Second, the nature of symbolically charged statehood issues gives them

weight and a level of difficulty that to many cannot be overcome by the more

mundane offer of eu accession. This means, in practice, that political actors

shy away from compromise for the sake of being accused of “treason” or “sell-

ing out” by political opponents and, also, fear the loss of electoral support.

Third, the combination of eu conflict resolution and eu accession policy has

empowered the ability of the eu to resolve major conflicts in potential eu mem-

bers. Yet, on the other hand, as outlined above, it resulted at times in mixed

messages with conflicting demands. Thus, efforts to centralize the police in

Bosnia represented a conflict-resolution measure aimed at weakening entities

and their political control over the police by ethno-national parties (at least this

was the hope). However, this approach was justified by the logic of eu acces-

sion. In the absence of eu-wide policing standards and, for that matter, widely

differing practices among eu member states, Bosnian Serb politicians called

the EU’s bluff, and eventually it had to back down.

Thus, when the eu began its mediation efforts in Kosovo in 2011, its record in

mediating conflicts in the Western Balkans over the previous decade was

mixed and based on structural difficulties. The 2007 Lisbon Treaty and the

2009 establishment of the European External Action Service (eeas) created

new structures and, thus, opportunities for eu engagement and mediation. At

the same time, the entry into force of the treaty shifted attention, at least at

first, inward and toward its own institution building.27 The foreign-policy

26 Sofia Sebastian, “The Role of the eu in the Reform of Dayton in Bosnia-Herzegovina”,

8(3–4) Ethnopolitics (2009), 341–354; and Robert Hayden, “The Continuing Reinvention of

the Square Wheel: The Proposed 2009 Amendments to the Bosnian Constitution”,

58(2) Problems of Post-Communism (2011), 3–16.

27 Steven Blockmans, “The European External Action Service One Year On: First Signs of

Strengths and Weaknesses”, cleer Working Paper (2012) No.2, available at <http://www

.asser.nl/upload/documents/1272012_11147cleer2012-2web.pdf>.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 292 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

The Serbia-kosovo Agreements 293

capacity available to most national governments dwarfed the new institutions

available to the eu. However, the conjunction of these foreign-policy instru-

ments and the offer of accession for Serbia and Kosovo provided the eu with

greater abilities to engage, effectively, most key actors in the region.

Yet, the fact that not all eu members had recognized Kosovo and that the

eu rule of law mission, eulex, only was deployed after becoming ‘status-

neutral’—i.e., not recognizing Kosovo’s declaration of independence—limited

the eu’s credibility in the eyes of Kosovo’s authorities. However, this did not

translate into greater support for eulex in particular and the eu in general

from Serbia, where nationalist parties had taken a strong anti-eu position fol-

lowing Kosovo’s declaration of independence and where the government,

dominated by President Boris Tadić, formally supported eu accession, but,

through its diplomacy, diverged considerably from eu policy.28

As we already have highlighted above, that eu engagement rested on the

dual tracks of conflict mediation, on the one hand, and eu accession on the

other, a complementary and at times conflicting strategy that the eu has utilized

in former Yugoslavia with varying degrees of success since the early 2000s.29

The unresolved dispute between Serbia and Kosovo at first seemed like an

unlikely candidate for eu conflict mediation. Serbia had been a reluctant

‘Europeanizer’ when it came to fulfilling the conditions set by the eu for acces-

sion for Kosovo, eu membership appeared more remote than for Serbia and,

thus, unlikely to provide sufficient incentives for enabling the mediation

between the two countries to yield tangible results.30 In particular, the litera-

ture on eu conditionality emphasizes the transformative effect of the eu

during accession negotiations.31 Unlike eu conditionality, the resolution of

bilateral issues between Kosovo and Serbia was not guided by the acquis per se

28 Mladen Mladenov, “An Orpheus Syndrome? Serbian Foreign Policy after the Dissolution

of Yugoslavia”, in Soeren Keil and Bernhard Stahl (eds.), The Foreign Policies of Post-

Yugoslav States: From Yugoslavia to Europe (Palgrave, London, 2014), 147-172, esp. 157–158;

and Florent Marciacq, Europeanisation of National Foreign Policy in Non-eu Europe: The

Case of Serbia and Macedonia (PhD dissertation, University of Vienna and University of

Luxembourg, 2014).

29 See Florian Bieber, “Building Impossible States? State-building Strategies and eu

Membership in the Western Balkans”, 63(10) Europe-Asia Studies (2011), 1783–1802.

30 Spyros Economides and James Ker-Lindsay, “Pre-Accession Europeanization: The Case of

Serbia and Kosovo”, 53(5) Journal of Common Market Studies (2015), 1027–1044.

31 Ulrich Sedelmeier, “Europeanization in New Member and Candidate States”, 6(1) Living

Reviews in European Governance (2011), 5–52; and Frank Schimmelfenning, “Europeani-

sation Beyond the Member States”, 8(3) Zeitschrift für Staats- und Europawissenschaften

(2010), 319–339.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 293 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

294 Bieber

and, thus, required the eu to act both as an incentive and as a mediator. The

risk of “fake compliance”—discussed in recent years in the context of eu con-

ditionality in the Western Balkans32—also applies to the dialogue between

Serbia and Kosovo, as we shall see in the context of the implementation of the

agreements.

For both Serbia and Kosovo, mediation came ahead of the beginning of

accession talks, with Serbia being offered the beginning of negotiations as

the main reward, while Kosovo was offered a Stabilisation and Association

Agreement. The success of the mediation process, as this article will argue,

rested on a combination of factors: the fortuitous timing following the icj’s

2010 advisory opinion, the strong domestic and international incentives in

both Serbia and Kosovo to demonstrate their willingness to move toward the

eu, and the particularities of the mediation that only gradually moved toward

more contested matters.

4 On the Path to a Serbia-Kosovo Dialogue

Negotiations between Kosovo and Serbia began in 2011, culminating in the 2013

Brussels Agreement.33 However, they continued thereafter with further agree-

ments, including another major implementation agreement in the summer of

2015.34

Between 2008 and 2011, Serbia’s foreign minister, Vuk Jeremić, devoted him-

self to limiting and even seeking to reverse Kosovo’s international recognition

following its declaration of independence.35 While the government, dominated

32 See Gergana Noutcheva, “Fake, Partial and Imposed Compliance: The Limits of the eu’s

Normative Power in the Western Balkans”, 16(7) Journal of European Public Policy (2009),

1065–1084. See, also, the different studies in Arolda Elbasani (ed.), European Integration

and Transformation in the Western Balkans: Europeanization or Business as Usual?

(Routledge, London, 2013), in particular Arolda Elbasani, “Europeanization Travels the

Western Balkans: Enlargement Strategy, Domestic Obstacles, and Divergent Reforms”,

3–22; and Milada Vachudova, “eu Leverage and National Interests in the Balkans: The

Puzzles of Enlargement Ten Years On”, 52(1) Journal of Common Market Studies (2014),

122–138.

33 Op.cit. note 13.

34 “Statement by High Representative/Vice-President Federica Mogherini Following the

Meeting of the eu-Facilitated Dialogue” (25 August 2015) No.150825_02, available at

<http://eeas.europa.eu/statements-eeas/2015/150825_02_en.htm>.

35 See his profile, Nicholas Kulish, “Recasting Serbia’s Image, Starting With a Fresh Face”,

The New York Times (15 January 2010), available at <http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/16/

world/europe/16jeremic.html?_r=0>.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 294 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

The Serbia-kosovo Agreements 295

by President Tadić, sought eu integration as its primary goal, Jeremić’s bellig-

erent engagement with Kosovo worsened relations with the eu.

The strategy of Jeremić involved extensive bilateral diplomacy with the goal

of preventing recognition of Kosovo. While many countries did not recognize

Kosovo at first, this mostly was a consequence of skepticism about the legality

thereof or for domestic reasons, rather than due to Serbian diplomacy. In fact,

some countries that were courted by both Serbia and Kosovo after 2008 prob-

ably failed to recognize Kosovo out of inertia. At the level of international orga-

nizations, Serbia invested considerable energy in preventing Kosovo from

joining any important organization and was relatively successful, mostly due to

support on the matter by some key countries, such as veto-yielding Russia and

China at the un. In addition, Serbia succeeded in 2008 in convincing the un

General Assembly to request an advisory opinion from the icj on whether the

declaration of independence was in line with international law in general and

with the 1999 un Security Resolution No.1244, in particular (which established

Kosovo’s international administration). The icj ruled in 2010, however, that

Kosovo’s declaration of independence did not violate international law:

“The Court has concluded above that the adoption of the declaration of

independence of 17 February 2008 did not violate general international law,

Security Council resolution 1244 (1999) or the Constitutional Framework.

Consequently the adoption of that declaration did not violate any appli-

cable rule of international law.”36

This opinion took both Kosovo and Serbia by surprise: while the Serbian media

and political elite interpreted the decision as a defeat and Kosovo saw it as a

victory, the court’s opinion was more complicated.37 The court only interpreted

the declaration itself, not the substance thereof, and thus provided no guid-

ance as to whether independence itself or secession from Serbia was in line

with international law. By taking a narrow focus on the declaration only, it

36 icj Advisory Opinion, op.cit. note 11.

37 For divergent views on the opinion see Marc Weller, “Modesty Can Be a Virtue: Judicial

Economy in the icj Kosovo Opinion?”, 24(1) Leiden Journal of International Law (2011),

127–147; Hurst Hannum, “The Advisory Opinion on Kosovo: An Opportunity Lost, or a

Poisoned Chalice Refused?”, 24(1) Leiden Journal of International Law (2011), 155–161;

Richard Falk, “The Kosovo Advisory Opinion: Conflict Resolution and Precedent”,

105(1) The American Journal of International Law (2011), 50–60; and Elena Cirkovic, “An

Analysis of the icj Advisory Opinion on Kosovo’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence”,

11 German Law Journal (2010), 895–912, available at <http://www.germanlawjournal.com/

index.php?pageID=11&artID=1275>.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 295 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

296 Bieber

bypassed larger political questions and avoided putting itself in conflict with

major powers. Although the opinion failed to trigger a new wave of recogni-

tions, as Kosovo had hoped, it also did not stem (nor did it reverse) the recogni-

tion of Kosovo’s independence, as Serbia had wished.38

The disappointment with the ruling was shared across much of Serbia’s

political and media spectrum. The government’s declaration to the parliament,

supported by mps in a vote on 26 July, condemned the icj and insisted that:

“The National Assembly expresses its full commitment to achieving […]

national and political unity on the issue of [the] preservation of Kosovo

and Metohija, and confirms that Serbia will never, […] explicitly [or]

implicitly, recognize the unilaterally declared independence of Kosovo

and Metohija.”39

For its part, the Serbian opposition blamed the government for pursuing the

wrong strategy in regard to Kosovo and called for its resignation.40

By the time the icj handed down its conclusions, nearly 70 countries had

recognized Kosovo, and the icj opinion put Serbia in a difficult position. After

initially lobbying for a separate statement at the un General Assembly—but

following eu pressure and because of Serbia’s weak position—the eu and

Serbia, jointly, proposed a un resolution welcoming eu mediation among the

‘parties’.41 The text of the resolution thus gave the eu a mandate to mediate,

although it provided little guidance as to what the mediation should focus on

or what the end result would be:

“The un General Assembly welcomes the readiness of the European

Union to facilitate a process of dialogue between the parties; the process

38 The 2008 Serbian initiative in the un General Assembly and the subsequent 2010 Advisory

Opinion of the icj are discussed in detail in Marko Milanović and Michael Wood (eds.),

The Law and Politics of the Kosovo Advisory Opinion (Oxford University Press, Oxford,

2015).

39 The original-language text of the resolution is available at <http://www.mfa.gov.rs/

sr/index.php/arhiva-saopstenja/saopstenja-2010/4736-2010-07-28-11-29-45?lang=lat>. The

translation is from Dwyer Arce, “Serbia Parliament Rejects Kosovo Independence in Per-

petuity”, Jurist (27 July 2010), available at <http://jurist.org/paperchase/2010/07/serbia

-parliament-rejects-kosovo-independence-in-perpetuity.php>.

40 Milan Milošević, “Između Prokletija, Haga i Ist Rivera”, Vreme (29 July 2010), available at

<http://www.vreme.com/cms/view.php?id=942891>.

41 The subsequent dialogue between Serbia and Kosovo provided another argument for

holding off recognition until the outcome of the dialogue became clear.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 296 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

The Serbia-kosovo Agreements 297

of dialogue in itself would be a factor for peace, security and stability in

the region, and that dialogue would be to promote cooperation, achieve

progress on the path to the European Union and improve the lives of the

people.”42

The resolution, thus, avoided further confrontation between the eu and Serbia

and, also, highlighted Serbia’s failure to sustain an active policy to resist

Kosovo’s independence. While the icj advisory opinion was more ambiguous

than the parties saw it, it provided an opportunity for the eu to pressure Serbia

to engage in dialogue if it wanted to proceed with eu integration and left the

Serbian government with few alternative strategies. The advisory opinion,

thus, inadvertently paved the way to eu mediation between Serbia and Kosovo.

5 The Beginning of eu-Mediated Talks

When talks between Serbia and Kosovo began in Brussels in March 2011, there

was no clear roadmap of the time line of the mediation or a defined goal for

the process. Rather, the eu—and in particular the eu High Representative of

the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Catherine Ashton—sought

to promote a dialogue between the two parties in an effort to reduce tensions

and produce a settlement of (at least some) key issues that constituted real

obstacles for Kosovo. Furthermore, the newly established External Action

Service (headed by Ashton) needed a success in its early days, and the Serbia-

Kosovo dialogue provided such an opportunity.43

The approach thus did not aim to resolve the different views on Kosovo’s

statehood but, rather, to set them aside in order to make modest progress on

the ground. The ambiguity, as I will discuss in more detail below, was one of the

42 un General Assembly Resolution “Request for an Advisory Opinion of the International

Court of Justice on Whether the Unilateral Declaration of Independence of Kosovo Is in

Accordance With International Law” (8 October 2008) No.63/3, available at <http://www

.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/

Kos%20A%20RES63%203.pdf>.

43 See Rosa Balfour, “Change and Continuity: A Decade of Evolution of eu Foreign Policy

and the Creation of the European External Action Service”, in Rosa Balfour, Caterina

Carta, and Kristi Raik (eds.), The European External Action Service and National

Foreign Ministries (Ashgate, Farnham, uk, Burlington, vt, 2015), 31–44; and Niklas Helwig,

“The High Representative of the Union: The Quest for Leadership in eu Foreign Policy”, in

David Spence and Jozef Bátora (eds.), The European External Action Service: European

Diplomacy Post-Westphalia (Palgrave, London, 2015), 87–104.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 297 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

298 Bieber

key features of the process that would ensue, allowing the eu to portray suc-

cess where, in fact, there was little. The focus of the negotiations was, thus, on

what at first were termed “technical issues”. The combination of the focus on

such seemingly minor issues with ambiguity was the only way to establish a

modicum of progress. In general, one can distinguish between negotiations

that focused on relations between Serbia and Kosovo and those that were pri-

marily concerned with relations between Kosovan Serbs and Kosovo. The tech-

nical nature of the talks was aimed at building a minimal level of confidence

between the two governments and, also, at avoiding discussion of topics that

required either Serbia to openly acknowledge Kosovo’s independence or (in)

action which could be considered in Kosovo to be a diminution of Kosovo’s

independence. Yet even when excluding the issue of status, the gap between

the two parties remained large.

Within Serbia, the environment for such talks, in principle, was not unfavor-

able, despite the confrontational policy pursued by Foreign Minister Jeremić.

The main opposition party until 2008—the extreme right-wing nationalist

Serbian Radical Party (srs)—had split, and the more moderate wing under the

joint leadership of Tomislav Nikolić and Aleksandar Vučić sought to build ties

with the eu and its member states and devoted little attention to the issue of

Kosovo. Furthermore, Vojislav Koštunica, the outgoing prime minister, lost

crucial elections in 2008 after positioning himself as a staunch opponent of

Kosovo’s independence and an increasingly radical critic of the eu. Thus, the

Serbian government and President Boris Tadić, had little opposition to a more

conciliatory policy in regard to Kosovo—even the protests at the time of the

declaration of independence were loud but brief.

Nevertheless, Vuk Jeremić’s policy—encouraged (or at least tolerated) by

Tadić—provided for an antagonistic environment between Serbia and

Kosovo. Robert Cooper, a key eu mediator, noted that some eu member states

sought a more constructive role for Serbia in relation to Kosovo as a prerequi-

site to accepting Serbia’s eu membership application.44 As a consequence,

the eu was in a position to link eu accession and the status of Kosovo. This

put an end to the Serbian government’s declared goal of decoupling eu acces-

sion from its policy toward Kosovo. The Serbian government feared that the

linkage would require Serbia to recognize Kosovo. However, the perceived

defeat at the icj weakened Serbia’s bargaining position, and Serbia’s 2009

membership application to the eu gave the eu integration process a specific

44 “The Brussels Agreement ‘Generated by Conversations, Not by Relentless Pressure’,

Interview with Robert Cooper”, lsee Blog (6 February 2015), available at <http://blogs.lse

.ac.uk/lsee/2015/02/06/robert-cooper-interview/>.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 298 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

The Serbia-kosovo Agreements 299

form. By engaging in dialogue, Serbia also sought to avoid pressure to recog-

nize Kosovo outright.

In Kosovo, on the other hand, the popular movement Vetëvendosje (Self-

Determination) competed in elections for the first time in 2010 and won 12.6

percent of the vote, making it the third-largest party in parliament. It rejected

dialogue with Serbia—arguing that dialogue would only be acceptable if

Kosovo participated as Serbia’s equal and only once Serbia formally apologized

for crimes committed in Kosovo—and demanded complete independence,

refusing the formal and informal mechanisms of international supervision.45

Thus, the domestic political context for negotiations was far from ideal.

Arguably, the Kosovan government was in a weaker position than Serbia, but it

could count on more international, especially crucial us, support than Serbia.

Serbia’s support on Kosovo from Russia and China translated into little when it

came to dialogue under eu auspices; yet, Serbia could live easier with the

status quo than Kosovo could. In the context of eu mediation, the five coun-

tries not recognizing Kosovo became crucial, as they precluded a full eu per-

spective for Kosovo, whereas Germany and the uk clearly conditioned Serbia’s

progress toward the eu with visible progress in its dialogue with Kosovo. In

Kosovo, statehood was challenged externally through non-recognizers and

internally through territories not under state control, as well as openly by

Serbia, which identified Kosovo as its main security threat.46 However, the eu’s

intervention in the process was crucial, as it meant that the talks (and the will-

ingness of both parties to compromise) were embedded in eu accession: for

Serbia, the possibility of becoming a candidate and beginning accession talks

became the incentive offered by the eu. This offer was not fundamentally new.

Jelena Subotić already noted in 2010 that “[t]he earlier trade-off—Europe for

The Hague—was now replaced by a new one—Europe for Kosovo”.47 For

Kosovo, the reward was a Stabilization and Association Agreement, agreed by

45 The party remains opposed to dialogue, but modified its position after the 2014 elections, as

it anticipated participation in a post-election coalition with three other parties. “Agreement

on Principles between the ldk-aak-nisma coalition and Lëvizja vetëvendosje!”

(10 September 2014), available at <http://www.vetevendosje.org/en/news_post/agreement-on

-principles-between-the-ldk-aak-nisma-coalition-and-levizja-vetevendosje/>.

46 Republic of Serbia, “National Security Strategy of the Republic of Serbia” (October 2009),

available at <http://www.voa.mod.gov.rs/documents/national-security-strategy-of-the-republic

-of-serbia.pdf>. This position was reiterated in 2012 by the chief of staff of the Serbian Army.

See “Kosovo Poses Biggest Security Threat to Serbia”, B92.net (18 May 2012), available at <http://

www.b92.net/eng/news/politics.php?yyyy=2012&mm=05&dd=18&nav_id=80301>.

47 Jelena Subotić, “Explaining Difficult States: The Problems of Europeanization in Serbia”,

24(4) East European Politics and Societies (2010), 595–616.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 299 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

300 Bieber

the eu’s European Commission in spring of 2015,48 something that all the

other countries in the region already had concluded.

At first, the negotiations focused on resolving issues rather than on a long-

term mediation strategy, concentrating initially on resolving practical problems

not touching sensitive symbolic matters.49 The topics that were initially dis-

cussed included the return of land and civil registers to Kosovo (taken by Serbian

authorities in 1999) and the recognition of Kosovan diplomas—topics chosen

because they had real consequence for citizens in Kosovo but not laced with

symbolism or linked to statehood. The talks had two crucial features. First, they

were incremental seeking to produce interim agreements rather than aiming at

a comprehensive settlement. Second, each of these intermediate steps was

marked not with an agreement or a treaty but, rather, by the conclusion of the

talks.50 In fact, these conclusions were vague and offered few specific details.

Between March 2011 and February 2012, Kosovo and Serb negotiators met in

Brussels in nine rounds of negotiations, reaching a number of agreements each

time. The talks were led by Edita Tahiri (deputy prime minister of Kosovo) and

Borislav Stefanović (political director at the Serbian Ministry of Foreign Affairs).

The key points of consensus reached during these talks included Serbia’s

acceptance of Kosovan customs stamps, thus paving the way to legal trade

between Serbia and Kosovo and, also, within the Central European Free Trade

Agreement Area (cefta), with the much diminished un mission, unmik,

acting as an intermediary.51 In addition, Serbia agreed to accept university

degrees from Kosovo, which it had been rejecting since 2008 due to the

reference to the Republic of Kosovo on the degrees. Through intermediate cer-

tification by the European University Association, the degrees would become

recognized in Serbia. Such a measure was particularly important for the

Albanian minority in Serbia, as most of those pursuing higher education

48 “Stabilisation and Association Agreement Between the European Union, of the One Part,

and Kosovo, of the Other Part” (30 April 2015), available at <http://ec.europa.eu/enlarge

ment/news_corner/news/news-files/20150430_saa.pdf>.

49 “Serbia/Kosovo: The Brussels Agreements and Beyond,” seesox Workshop Report (January

2014), 3, available at <http://www.sant.ox.ac.uk/seesox/workshopreports/Serbia-Kosovo%

20Workshop%20report.pdf>.

50 Adem Beha, “Disputes over the 15-Point Agreement on Normalization of Relations

Between Kosovo and Serbia”, 43(1) Nationalities Papers: The Journal of Nationalism and

Ethnicity (2015), 102–121.

51 This also meant that products from Kosovo would need to be labeled as “unmik”, which

complicates exports, as this designation is meaningless elsewhere. Furthermore, the

implementation was complicated by the fact that the customs area for Kosovo is in South

Mitrovica, but there is no effective customs control north of the Ibar River.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 300 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

The Serbia-kosovo Agreements 301

among Albanians from Serbia enrolled in universities in Kosovo and only

would be able to obtain employment in Serbia as a teacher or a civil servant if

their diplomas were recognized by Serbia. It also mattered for the Serbian

minority, as Kosovo had not been willing to recognize degrees issues by the

Serbian university in North Mitrovica (officially designated as the University of

Prishtina in Mitrovica). As in other domains, the ambiguity of the agreement

translated into difficulties in terms of implementation, as the Serbian

University of Mitrovica was not explicitly mentioned. Thus, it remained

unclear whether its degrees would be recognized like those of other Serbian

universities (as the Serbian government argued) or whether it would require a

separate agreement (as the Kosovan side maintained).52

Other issues—still ‘technical’ but of greater significance—were those of

land records (or cadasters) and the civil register, which (as highlighted above)

the Serbian authorities had removed from Kosovo at the end of the war in

1999. This made property claims and real estate sales—along with personal

documentation—in Kosovo problematic. The agreement between Kosovo and

Serbia established a procedure by which Serbia would submit scanned copies

of the registers to Kosovo, a rather complicated and slow process. The talks also

touched on the freedom of movement for citizens of both countries. Unless

Serbia recognized Kosovan documents, travel through and to Serbia remained

difficult for many citizens of Kosovo. The agreement reached in this matter was

the mutual recognition of id cards for travel as well as of driver’s licenses.

These achievements notwithstanding, many practical obstacles remained, e.g.,

high road taxes and the need for temporary license plates when traveling

through Serbia if the vehicle had post-independence license plates along with

the issue of free movement for third-country nationals and, also, citizens with-

out id cards.53

There was a gradual movement in the negotiations from less sensitive topics

to more complex and controversial ones, such as management of the border

between Serbia and Kosovo. By incorporating these issues into the negotiations,

they also were removed from the question of recognition, which remained off

52 See “Agreements not to Agree Between Prishtina and Belgrade” (n.d.), available at <http://

internewskosova.org/en/Emisionet/Agreements-not-to-agree-between-Prishtina-and-

Belgrade—75>; and “Big Deal: Civilized Monotony. Civic Oversight of the Kosovo-Serbia

Agreement Implementation”, Balkan Insight (November 2014) No.1, available at <http://

www.balkaninsight.com/en/file/show/BIG%20DEAL%20FINAL%20ENG.pdf>.

53 Leon Malazogu, Florian Bieber, and Drilon Gashi, “The Future of Interaction Between

Prishtina and Belgrade”, Confidence Building Measures in Kosovo (September 2012) No.3,

available at <http://d4d-ks.org/assets/2012-10-17-PER_DialogueENG.pdf>.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 301 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

302 Bieber

the agenda. The Integrated Border Management (ibm) agreement concluded

in December 201154 marked the first significant step regarding the dialogue,

both complicated and both given urgency by clashes in the north of Kosovo in

the months preceding the end of the year (see below). The joint control of the

border through the ibm was crucial in reducing smuggling and other illegal

activities. By settling on the term “ibm”, the agreement enabled creative ambi-

guity: for Kosovo, it meant “integrated border management”; for Serbia, on the

other hand, it meant “integrated boundary management”. This creative ambi-

guity allowed the negotiation process to continue, but it could not resolve

different views that were not merely semantic. As a result, the implementation

process was considerably more difficult than reaching the agreements between

Serbia and Kosovo in the first place. Implementation was a sensitive process in

light of its symbolic significance: it meant that border controls would be estab-

lished between the north of Kosovo and Serbia (with a shared practical goal of

reducing smuggling).

Here once more, the agreement was concluded notwithstanding the differ-

ing views of the parties on the status of Kosovo. Thus, rather than consolidat-

ing Kosovo’s independence, the process cemented the competing narratives

and gave Serbia strong formal and informal roles in Kosovo, leading to a de

facto degree of shared sovereignty in parts of Kosovo.

The agreement, first of all, foresaw the establishment of joint border cross-

ings staffed by Kosovo, Serbian, and eu (eulex) representatives; in the case of

the contested crossings in the north of Kosovo, eulex is the only authority.55

The second sensitive issue negotiated revolved around the regional repre-

sentation of Kosovo. Despite Kosovo’s independence, it had to continue to rely

on unmik to formally represent it in international regional organizations.

Following the 2012 agreement on the regional representation of Kosovo,56

54 See, for example, European Court of Auditors, “Special Report: European Union Assistance

to Kosovo Related to the Rule of Law” (2012) No.18, referencing inter alia the December

2011 ibm, available at http://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/SR12_18/SR12_18

_EN.PDF>.

55 Aubrey Hamilton, “From Technical Arrangements to Political Haggling”, A Policy Report

by the Group for Legal and Political Studies (February 2012) No.2, 18, available at <http://

legalpoliticalstudies.org/download/Policy%20Report%2002%202012%20english.pdf>.

See, also, International Crisis Group, “Serbia and Kosovo: The Path to Normalisation”,

Europe Report (19 February 2013) No.223, available at <http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/

regions/europe/balkans/kosovo/223-serbia-and-kosovo-the-path-to-normalisation

.aspx>.

56 “Agreement between Serbia and Kosovo (Pristina): Arrangements Regarding Regional

Representation and Cooperation” (24 February 2012), available at <https://inavukic.files

.wordpress.com/2012/02/agreement-between-serbia-and-kosovo.pdf>.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 302 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

The Serbia-kosovo Agreements 303

Kosovo was able not only to represent itself but, also, to sign agreements

directly. However, the agreement did not pave the way to comprehensive mem-

bership in international organizations, as it was limited to regional organiza-

tions and also required Kosovo to use a rather cumbersome qualifier: “This

designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with

unsc 1244 and the icj Opinion on the Kosovo Declaration of Independence.”57

As the details of its use were not fully specified in the agreement, a number of

regional meetings in the years following the agreement were fraught with ten-

sion, as either Serbia or Kosovo objected to the use of the qualifier.

The sensitive nature of the overall mediation process between Serbia and

Kosovo and the risks of failure became apparent at a number of junctures, as

could be seen when the issues of customs were discussed. In July 2011 Serbia

stayed away from negotiations, leading to an attempt by Kosovo‘s government

to force Serbia’s hand,58 i.e., that same month, the Kosovan government first

introduced a ban on Serbian goods based on reciprocity, not an insignificant

measure considering the significance of the Kosovan market for Serbian goods

(Serbia’s largest trade surplus is with Kosovo).59 A few days later, Kosovan

security forces sought to enforce the rule by taking control of the border cross-

ings in the north of Kosovo that had not been under government control.

During the operation, a member of a police unit was killed, and Kosovan Serbs

in the north erected barricades. After Kosovan forces retreated from the check-

points a few days after the operation, the border posts were demolished and

one was set ablaze by Serb protestors. This led to kfor taking over the posts.60

By September, Kosovo had lifted the ban on Serbian goods after a customs

agreement was reached in September 2011 that allowed Kosovo to use the term

‘Kosovo customs’. While formally Serbia had backed down, other obstacles

continued to prevent Kosovan products from entering Serbian market.

Nevertheless, in the north, the standoff between kfor and the Kosovan Serbs

who erected the barricades continued for months, and many in the north sup-

ported the barricades and participated personally.61 Over time, it became

apparent that the roadblocks, despite some support from Serbia, could not

57 European Union, Press Statement, “eu Facilitated Dialogue: Agreement on Regional

Cooperation and ibm Technical Protocol” (24 February 2012), No.5455/12, available at

<http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/EN/foraff/128138

.pdf>.

58 Hamilton, op.cit. note 55, 7.

59 “New Trouble in Kosovo,” The Economist (26 July 2011), available at <http://www.econo

mist.com/blogs/easternapproaches/2011/07/serbia-and-kosovo>.

60 Hamilton, op.cit. note 55, 8.

61 Ibid., 10.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 303 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

304 Bieber

prevent international control over the border between Serbia and Kosovo, and

the protests slowly petered out. On one side, the violence highlighted the risks

of the mediation and, also, the low levels of trust between the parties that

could result in such an escalation; it also underlined the need for further medi-

ation, as the status quo had become unsustainable. In particular northern

Kosovo, which had existed in legal limbo since 1999 and even more so after

2008, could not maintain its status after the events of the summer of 2011.

The barricades and an unofficial referendum organized in February 2012 in

the four largely Serb-populated municipalities in northern Kosovo highlighted

the alienation of Kosovan Serbs from both the Serbian government and the

authorities in Kosovo. In the referendum, citizens were asked the rather ten-

dentious question: “Do you accept the institutions of the so-called Republic of

Kosovo?” The answer was no surprise: of the purported 26,524 participants,

99.74 percent voted no. The referendum was locally organized and rejected by

both Serbia and Kosovo; yet, the opposition to the state of Kosovo and to talks

that would strengthen it in northern Kosovo was real.62

6 From Technical to Political Negotiations

By 2012, the technical negotiations had run their course, and it became appar-

ent that without a larger political settlement, the implementation of the tech-

nical agreements concluded in 2011 and 2012 would not be completed. The less

sensitive parts of the agreement were mostly implemented, but the controver-

sial aspects were stalling, in particular as a consequence of the crisis in north-

ern Kosovo.

While the Assembly of Kosovo voted to support talks as long as they did not

threaten Kosovo’s integrity and the Assembly would ratify any agreement,

Serbia argued for an autonomous region in northern Kosovo.63 After the tech-

nical dialogue appeared to have “exhausted itself”,64 it was unexpectedly

revived by the 2012 elections in Serbia.

The victory of the Serbian Progressive Party (sns) in parliamentary elections

and the defeat of Boris Tadić by Tomislav Nikolić in presidential elections

brought new interlocutors to power in Serbia, and the sns had several reasons

62 “Serben stimmen mit fast 100 Prozent gegen Prishtina”, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (16

February 2012), available at <http://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/ausland/volksabstim-

mung-im-kosovo-serben-stimmen-mit-fast-100-prozent-gegen-prishtina-11651469.html>.

63 Beha, op.cit. note 50, 108.

64 seesox, op.cit. note 49, 4.

review of central and east european law 40 (2015) 285-319

0002622495.INDD 304 301961 11/9/2015 7:57:02 PM

The Serbia-kosovo Agreements 305

to engage more energetically in the talks. First, the party was treated with sus-

picion by many eu officials due to the nationalist background of its leadership;

thus, it seized on the talks with Kosovo as a way to prove its transformation.

Second, it had no strong political challenger that could accuse the party of trea-

son. The Democratic Party of Serbia (dss) entered parliament but had declin-

ing levels of support despite (or because of) its focus on Kosovo and its rejection

of eu accession. The srs, from which the sns had split four years earlier, failed

to clear the 5 percent threshold. Third, the sns recognized Serbia’s declining

influence with regard to Kosovo and seized upon the opportunity to maximize

concessions for Serbia from the eu and Kosovo.65

The eu had provided clear guidelines over the direction of the dialogue by

late 2012. In the December 2012 conclusions of the European Council, it identi-

fied four conditions for Serbia to move to the next phase of eu integration,

i.e., (A) the implementation of the agreements reached to date; (B) the dis-

mantling of the Serbian police and judiciary institutions in Kosovo; (C) the

introduction of transparency into the spending for Kosovo; and (D) greater

cooperation with eulex.66

The conclusions were more specific than earlier eu statements in this field

and, also, highlighted the shift from technical questions to more sensitive mat-

ters that affected the status of the north of Kosovo. Thus, between October 2012

and June 2013, the negotiations shifted to a higher level, with the prime minis-

ters of Kosovo and Serbia, Hashim Thaçi and Ivica Dačić, respectively, partici-

pating. The first tangible agreements in December foresaw the establishment

of liaison officers who would act as representatives of the two countries in

the respective eu missions. While Kosovo treated this agreement as the equiv-

alent of the establishment of diplomatic relations and assigned a former

ambassador to the post, Serbia appointed a junior official without a diplomatic

background.67 Overall, the impact of the two officials has been limited. Another

agreement foresaw the establishment of a multiethnic police unit in Kosovo to

protect religious and cultural heritage sites, as well as an arrangement on the