Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Luara Ferracioli: Morality in Migration: A Review Essay

Luara Ferracioli: Morality in Migration: A Review Essay

Uploaded by

Jo CCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- FOE ReviewerDocument80 pagesFOE ReviewerNikko Tolentino100% (10)

- Blake, Michael, Immigration, Jurisdiction and Exclusion PDFDocument28 pagesBlake, Michael, Immigration, Jurisdiction and Exclusion PDFIvaan' Alekqine100% (2)

- Do States Have A Moral Obligation To ObeyDocument21 pagesDo States Have A Moral Obligation To Obeypocotopc1No ratings yet

- The Challenge of Globalization On Citizenship: Topic 10Document26 pagesThe Challenge of Globalization On Citizenship: Topic 10Eleonor ClaveriaNo ratings yet

- Representative Democracy: The Constitutional Theory of Campaign Finance ReformDocument136 pagesRepresentative Democracy: The Constitutional Theory of Campaign Finance ReformRob streetmanNo ratings yet

- Political Obligation Short NotesDocument4 pagesPolitical Obligation Short NotesDivya SkaterNo ratings yet

- The Promise of Human Rights: Constitutional Government, Democratic Legitimacy, and International LawFrom EverandThe Promise of Human Rights: Constitutional Government, Democratic Legitimacy, and International LawNo ratings yet

- International Law.Document3 pagesInternational Law.Mehak FatimaNo ratings yet

- Globalization and The Theory of International LawDocument13 pagesGlobalization and The Theory of International LawMidha MoeenNo ratings yet

- Political ObligationDocument4 pagesPolitical Obligationtejukaki0No ratings yet

- Souverei Global WorldDocument14 pagesSouverei Global WorldЕкатерина ЦегельникNo ratings yet

- Direct Democracy - Government of The People by The People and FoDocument9 pagesDirect Democracy - Government of The People by The People and FoHuy NguyenNo ratings yet

- Why Do States Mostly Obey International LawDocument11 pagesWhy Do States Mostly Obey International Lawsurajalure44No ratings yet

- Carens - Who Should Get inDocument16 pagesCarens - Who Should Get inJoel CruzNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Global Justice: Central QuestionsDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Global Justice: Central QuestionsRangoli NagendraNo ratings yet

- Migration+and+Justice+ +a+Reply+to+My+CriticsDocument11 pagesMigration+and+Justice+ +a+Reply+to+My+CriticsDanyNo ratings yet

- Migration in Legal and Political Theory, Eds. Sarah Fine and Lea Ypi (Oxford, Forthcoming)Document17 pagesMigration in Legal and Political Theory, Eds. Sarah Fine and Lea Ypi (Oxford, Forthcoming)text7textNo ratings yet

- The Authority of Human RightsDocument34 pagesThe Authority of Human Rightswanjiruirene3854No ratings yet

- Critics To The Critical Legal StudiesDocument9 pagesCritics To The Critical Legal StudiesJuan MateusNo ratings yet

- Transnational Human Rights ObligationsDocument18 pagesTransnational Human Rights ObligationsAngraj SeebaruthNo ratings yet

- The War of Law - How New International Law Undermines Democratic SovereigntyDocument14 pagesThe War of Law - How New International Law Undermines Democratic SovereigntyGul BarecNo ratings yet

- LiberalismDocument4 pagesLiberalismIsrar AhmedNo ratings yet

- Introduction: Human Rights in The Study of Politics: David BeethamDocument9 pagesIntroduction: Human Rights in The Study of Politics: David BeethamHafiz ShoaibNo ratings yet

- Int J Constitutional Law 2013 Hirschl 1 12Document12 pagesInt J Constitutional Law 2013 Hirschl 1 12jjjvvvsssNo ratings yet

- The Limits of International LawDocument272 pagesThe Limits of International LawClifford Angell Bates100% (2)

- Introduction To The History, Theory and Politics of Constitutional LawDocument14 pagesIntroduction To The History, Theory and Politics of Constitutional LawsamiNo ratings yet

- Public International Law NoteDocument67 pagesPublic International Law NoteKalewold GetuNo ratings yet

- State Sovereignty Research PapersDocument6 pagesState Sovereignty Research Papersc9kb0esz100% (1)

- Global Justice: HistoryDocument7 pagesGlobal Justice: HistorymirmoinulNo ratings yet

- The Ancient and Modern Thinking About JusticeDocument22 pagesThe Ancient and Modern Thinking About JusticeAditi SinhaNo ratings yet

- 2 AcDocument15 pages2 AcChristian GinesNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Human Rights: Feature ReviewDocument14 pagesThe Politics of Human Rights: Feature ReviewFareha Quddus KhanNo ratings yet

- LD - JanFebDocument112 pagesLD - JanFebGilly FalinNo ratings yet

- The Critical Legal Studies Movement: Another Time, A Greater TaskFrom EverandThe Critical Legal Studies Movement: Another Time, A Greater TaskRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Constitutional LawDocument4 pagesConstitutional LawYassir MalikNo ratings yet

- Critical Legal StudiesDocument3 pagesCritical Legal StudiesPriyambada Das50% (2)

- Miller-2008-Journal of Political PhilosophyDocument20 pagesMiller-2008-Journal of Political PhilosophyfaignacioNo ratings yet

- S S: W H I L W W C: Ymmetry and Electivity HAT Appens in Nternational AWDocument52 pagesS S: W H I L W W C: Ymmetry and Electivity HAT Appens in Nternational AWNyasclemNo ratings yet

- ELE AffirmativeDocument6 pagesELE AffirmativeCedric ZhouNo ratings yet

- American Government (2pg)Document9 pagesAmerican Government (2pg)Kevin KibugiNo ratings yet

- Colonization and The Rule of Law - Comparing The Effectiveness ofDocument46 pagesColonization and The Rule of Law - Comparing The Effectiveness ofdip-law-70-22No ratings yet

- We Affirm The Resolution Today: Resolved: Birthright Citizenship Should Be Abolished in The United StatesDocument4 pagesWe Affirm The Resolution Today: Resolved: Birthright Citizenship Should Be Abolished in The United StatesRyan JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Do States Have A Moral Obligation To Obey International LawDocument20 pagesDo States Have A Moral Obligation To Obey International LawNatalia Torres ZunigaNo ratings yet

- The 4th Branch of GovernmentDocument16 pagesThe 4th Branch of GovernmentAndrei-Valentin BacrăuNo ratings yet

- Fedarel Goverment of IndiaDocument6 pagesFedarel Goverment of IndiaMarsum Akther HossainNo ratings yet

- What Are Human RightsDocument3 pagesWhat Are Human RightsAlejandro GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Constitution Research Paper TopicsDocument4 pagesConstitution Research Paper Topicsxfeivdsif100% (1)

- Colle Anglais 1Document3 pagesColle Anglais 1yanil2005No ratings yet

- A Political Theology For A Civil Religion - Paul KahnDocument28 pagesA Political Theology For A Civil Religion - Paul KahnAnonymous eDvzmvNo ratings yet

- Libfile - Repository - Content - Law, Society and Economics Working Papers - 2013 - WPS2013-12 - ThomasDocument33 pagesLibfile - Repository - Content - Law, Society and Economics Working Papers - 2013 - WPS2013-12 - ThomasDoreen AaronNo ratings yet

- CSS Criminology Notes - Basic Concept in CriminologyDocument6 pagesCSS Criminology Notes - Basic Concept in CriminologyMurtaza Meer VistroNo ratings yet

- Midterm EIP KastratiDocument4 pagesMidterm EIP KastratiYllka KastratiNo ratings yet

- From Parchment to Dust: The Case for Constitutional SkepticismFrom EverandFrom Parchment to Dust: The Case for Constitutional SkepticismNo ratings yet

- Studying PoliticsDocument20 pagesStudying PoliticsRicardo Aníbal Rivera GallardoNo ratings yet

- Barney's Lay NCDocument5 pagesBarney's Lay NCGiovanni GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Internat PDFDocument11 pagesInternat PDFfisicanasserNo ratings yet

- Ghai - Ethnic Diversity and ConstitutionalismDocument23 pagesGhai - Ethnic Diversity and ConstitutionalismOllivellNo ratings yet

- Cards 1Document4 pagesCards 1moaokkNo ratings yet

- Democracy On The LamDocument21 pagesDemocracy On The LamVth SkhNo ratings yet

- What Is ArtDocument3 pagesWhat Is ArtJo CNo ratings yet

- How To Analyse A PoemDocument2 pagesHow To Analyse A PoemJo CNo ratings yet

- Objective: To Analyse The Writer's Intentions Through The Representations of Characters in The Context of The NarrativeDocument9 pagesObjective: To Analyse The Writer's Intentions Through The Representations of Characters in The Context of The NarrativeJo C100% (1)

- LDP Sparks Tle - Worksheets Et Pistes de Réponse Vierges - Chap 15Document9 pagesLDP Sparks Tle - Worksheets Et Pistes de Réponse Vierges - Chap 15Jo CNo ratings yet

- MYP4-5 War-Photographer-Annotated - Correction War PoetryDocument1 pageMYP4-5 War-Photographer-Annotated - Correction War PoetryJo C100% (1)

- Practice Paper Revision SocialDocument2 pagesPractice Paper Revision SocialHussain AbbasNo ratings yet

- SouthWest Candidates For European Elections 2009Document2 pagesSouthWest Candidates For European Elections 2009James Barlow100% (1)

- PSI Facility - CordesDocument2 pagesPSI Facility - CordesMichael EvermanNo ratings yet

- Commercial Law (Dean Sundiang)Document17 pagesCommercial Law (Dean Sundiang)Gee GuevarraNo ratings yet

- LT E-Bill Shop 7 17sept 2019Document2 pagesLT E-Bill Shop 7 17sept 2019John Smith0% (1)

- The Benefit of The Doubt TextDocument11 pagesThe Benefit of The Doubt TextAreen KumarNo ratings yet

- 4th Year SDP Seating PlanDocument1 page4th Year SDP Seating PlanShuvendu ShilNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Officer Taking Deposition - SAMPLE FOR ACADEMIC USE ONLYDocument4 pagesCertificate of Officer Taking Deposition - SAMPLE FOR ACADEMIC USE ONLYEJ CruzNo ratings yet

- ETHICSDocument4 pagesETHICSReginald AgcambotNo ratings yet

- 1ST-NMCC-BROCHURE 20231123 165119 0000 CompressedDocument31 pages1ST-NMCC-BROCHURE 20231123 165119 0000 CompressedEshanNo ratings yet

- CGH AS BUILT Floor PlanDocument1 pageCGH AS BUILT Floor PlanMary FelicianoNo ratings yet

- Land Sale AgreementDocument4 pagesLand Sale AgreementHollyfatNo ratings yet

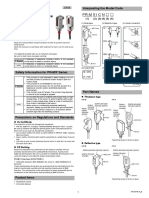

- PR-M/PR-F Series: Self-Contained Miniture Photoelectric SensorDocument3 pagesPR-M/PR-F Series: Self-Contained Miniture Photoelectric SensorThinh phan thanhNo ratings yet

- Power and Influence Case THOMAS GREEN Fall 2018 1Document29 pagesPower and Influence Case THOMAS GREEN Fall 2018 1suggestionboxNo ratings yet

- 151-Article Text-953-2-10-20230105Document8 pages151-Article Text-953-2-10-20230105indilstree22No ratings yet

- Geutebrueck Solutions Overview (Vestera)Document41 pagesGeutebrueck Solutions Overview (Vestera)Ahmad ImranNo ratings yet

- Companies Act 2013: Meaning of A CompanyDocument7 pagesCompanies Act 2013: Meaning of A CompanyMohit RanaNo ratings yet

- Transportation Laws: Instructions: Read Each Item Carefully Before Answering. Answer TheDocument5 pagesTransportation Laws: Instructions: Read Each Item Carefully Before Answering. Answer TheRikka ReyesNo ratings yet

- 1204 1980Document6 pages1204 1980Fabio MiguelNo ratings yet

- Topic 9 ThermodynamicsDocument4 pagesTopic 9 ThermodynamicsTengku Lina IzzatiNo ratings yet

- Braeckman, Niklas Luhmann's Systems Theoretical Redescription of The Inclusionexclusion Debate, 2006Document24 pagesBraeckman, Niklas Luhmann's Systems Theoretical Redescription of The Inclusionexclusion Debate, 2006Juan AhumadaNo ratings yet

- Code of Practice For Temporary Traffic Management (Copttm) : Traffic Control Devices ManualDocument114 pagesCode of Practice For Temporary Traffic Management (Copttm) : Traffic Control Devices ManualBen SuttonNo ratings yet

- Intellectual CapitalDocument3 pagesIntellectual CapitalMd Mehedi HasanNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Computation of MarksDocument5 pagesGuidelines For Computation of MarksLoolik SoliNo ratings yet

- The Criminal Law of The Consumer Protection On Sale Buy Online Through Mass MediaDocument9 pagesThe Criminal Law of The Consumer Protection On Sale Buy Online Through Mass MediaMaica ManguiatNo ratings yet

- Marketing Schedule: JanuaryDocument14 pagesMarketing Schedule: JanuaryKen CarrollNo ratings yet

- Sample AgreementDocument26 pagesSample AgreementSteamhouse InternNo ratings yet

- (U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictDocument5 pages(U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictFauquier NowNo ratings yet

- Sayani 19 WBCSDocument3 pagesSayani 19 WBCSSayonie BoseNo ratings yet

Luara Ferracioli: Morality in Migration: A Review Essay

Luara Ferracioli: Morality in Migration: A Review Essay

Uploaded by

Jo COriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Luara Ferracioli: Morality in Migration: A Review Essay

Luara Ferracioli: Morality in Migration: A Review Essay

Uploaded by

Jo CCopyright:

Available Formats

REVIEW

LUARA Morality in Migration:

FERRACIOLI A Review Essay*

Christopher H. Wellman and Phillip Cole’s discussion in Debating

the Ethics of Immigration (Oxford: Oxford University Press,

2011) Ryan Pevnick’s Immigration and the Constraints of Justice

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011)

For as long as our world remains one in which states employ coercive force to

guard their borders, and where prospective immigrants often risk their lives to

cross them, immigration will remain a contested practical and moral topic. In

recent decades philosophers have defended various answers to the question of

whether states are morally justified, or act legitimately, when they stop foreigners

from entering or acquiring membership of the state. Some have advocated a

world of open borders, while others have defended the full sovereignty of states

in matters of immigration. Christopher H. Wellman and Phillip Cole’s discussion

in Debating the Ethics of Immigration and Ryan Pevnick’s Immigration and the

Constraints of Justice are both valuable contributions to this body of literature.

Debating the Ethics of Immigration presents two opposing views: Wellman

defends the right of legitimate states to exclude prospective immigrants, while

Cole defends open borders. Both authors seek to answer the fundamental

question of whether states act legitimately when they exclude non-members,

while also exploring such practical topics as the ethics of guest worker programs,

the selection criteria for authorized entrance, and the global governance of

immigration. Pevnick’s Immigration and the Constraints of Justice defends a

position that falls in between that of Cole and Wellman’s. On Pevnick’s view,

the state’s prima facie right to exclude is trumped by the claims of refugees and

desperately poor people. While each of these works offer important insights to

the debate, a plausible justification for the right to exclude is still needed, as well

as a more nuanced understanding of how morality imposes limits on this right.

On the right to exclude

In his contribution to Debating the Ethics of Immigration, Wellman restates

and develops the case he has made in his previous work for the right of legitimate

* I would like to thank Christian Barry, Ryan Cox and Robert O. Keohane for helpful comments and criticisms.

GLOBAL JUSTICE : THEORY PRACTICE RHETORIC (4) 2011

LUARA FERRACIOLI 121

states to exclude prospective immigrants.1 His account rests on three basic

premises: (1) legitimate states have a right to political self-determination, (2)

freedom of association is an essential component of political self-determination,

and (3) freedom of association allows one not to associate with others. From these

three premises, he concludes that “legitimate states may choose not to associate

with foreigners, including potential immigrants, as they see fit” (p. 13).

In support of the first premise, Wellman offers a couple of intuitive examples.

The first example involves the aftermath of the Second World War, when the

Allied Powers sought to prosecute and punish Nazi leaders by establishing the

Nuremberg Trials. He recounts the controversy at the time, when, among other

things, critics questioned the Nuremberg court’s jurisdiction over crimes that

were committed by Germans against their fellow citizens. While Wellman agrees

that crimes against compatriots are paradigmatically a case for a state’s internal

legal system, he ultimately rejects this view on the grounds that it fails to take

into account the distinction between legitimate and illegitimate states.2 Because

Germany was not a legitimate state, Wellman argues, it was not entitled to exercise

dominion over its internal affairs.

Wellman introduces a second case, one in which the state in question is clearly

legitimate. He imagines a scenario in which contemporary Norway becomes lax

in prosecuting and punishing drivers who exceed the speed limit, leading to an

increase in fatal car accidents. Wellman then asks if it would be right for Sweden

to take it upon itself to prosecute and punish Norwegian offenders. The answer,

he concludes, must surely be negative, given that such unilateral action on the

part of Sweden would violate Norway’s right to govern its domestic affairs, which

it enjoys by virtue of being a legitimate state.

Having argued for the view that legitimate states have a robust right to self-

determination, Wellman turns to defend his second and third premises. In order to

elicit our intuitions about the importance of freedom of association, he constructs

a scenario in which a hypothetical government agency decides on behalf of its

citizenry who should marry whom and how many children each couple should

have. As he notes, such an arrangement by the state would be deeply problematic

because self-determination entails “being the author of one’s life, and these

individuals’ lives clearly have vital parts of their scripts written by the government

rather than autobiographically, as it were” (p. 31). Wellman goes on to argue that

we must always start our moral judgments with a “presumption in favor of freedom

of association” (p. 34), and this is true with respect to determining membership

1 Christopher Wellman, ‘Immigration and Freedom of Association’, Ethics 119 (2008), pp. 109-141.

2 For Wellman, legitimate states are those that adequately protect the human rights of their members and the rights of

others (p. 16).

GLOBAL JUSTICE : THEORY PRACTICE RHETORIC (5) 2012

MORALITY IN MIGRATION: A REVIEW ESSAY 122

in all sorts of associations, such as clubs, religious groups, and states. Given that

freedom of association also entails the right not to associate with others, Wellman

concludes that legitimate states have a presumptive right not to associate with

prospective immigrants.

While Wellman’s arguments have merit on their own terms, the application

of freedom of association as the pertinent moral value at the state level remains

controversial. Ultimately, the value of political autonomy, and not that of

freedom of association, provides a rationale for a robust right to exclude. Liberal

societies take freedom of association seriously because of how much they care

about personal autonomy, which entails, among other things, the ability to decide

unilaterally whether to associate, disassociate, or not to associate with others.

But the reason we care about self-determination at the state level is that we care

about the political autonomy of the citizenry, which entails, among other things,

the ability to decide collectively on matters of political membership.

In arguments about a right to exclude, political autonomy and not freedom

of association is the relevant value, because political autonomy can ground

a right to self-determination. To make better sense of how political autonomy

grounds self-determination, imagine a situation in which, due to environmental

reasons, Canada refuses visas to U.S. workers even though Canada would benefit

economically from accepting them. Imagine further that the United States objects

to this policy and decides to help smuggle these workers into Canada. After

designing a plan that ensures no one is harmed in the process, the United States

carries out this plot, thereby making both U.S. immigrants and Canadians better

off economically. Is there anything wrong about this? My intuition is that there is

something wrong: by unilaterally assigning such a role to itself, the United States

undermines the political autonomy of Canadian citizens. Given that Canadians

are not only autonomous individuals but also autonomous political agents, they

have a right to decide for themselves what sort of migration arrangement best

suits their collective aspirations.

Rights of freedom of association at the state level are also limited in important

ways. For instance, we do not typically think that citizens have the right to

disassociate from the state, thereby returning to the state of nature. And as Sarah

Fine has pointed out, “states are neither intimate nor expressive associations,”3

which makes them qualitatively different from the collectives where freedom of

association seem to matter the most (marriage being a paradigm example). In

a sense, political communities are simply different sorts of collectives, and the

reason we must respect the right of citizens to exercise control over immigration

3 Sarah Fine, ‘Freedom of Association is Not the Answer,’ Ethics 120 (2010), p. 353.

GLOBAL JUSTICE : THEORY PRACTICE RHETORIC (5) 2012

LUARA FERRACIOLI 123

is that we must respect their political autonomy. Indeed, there is nothing that

sets immigration apart from other domestic issues that primarily affect citizens

and residents, but also have spillover effects on outsiders. As with questions

regarding the usage of natural resources, trade policies, and budget allocations,

we must strike the right balance between the political autonomy of the citizenry

and the moral claims of foreigners. The upshot here is that a plausible account

of the ethics of migration must carve out enough space for the right of citizens to

determine their own political future, while simultaneously ensuring that morality

bears on matters of migration.

Another reason to think that freedom of association can only play a limited

role (if any) in determining rights in immigration is that it seems to trivialize the

necessity of political membership. As Phillip Cole reminds us in his contribution

to Debating the Ethics of Immigration, “When one leaves a club, or a marriage,

or even a job, one does not need to have another similar association to enter into

in order to exercise that right…. But to exercise the right to leave a state, one

needs another state to exit into” (p. 209). Following Cole, we should understand

states as “meta-associations,” where all other sorts of association can flourish,

and where autonomous human lives are made possible. By focusing on freedom

of association, Wellman’s arguments for a right to exclude obscure the role of

political autonomy in grounding self-determination, while undermining what is

really at stake for those fleeing political persecution, dire economic circumstances

and severe human rights violation: the inability to lead minimally decent lives

in their countries of citizenship rather than their interest in associating with a

different set of people.

Given that the right to political self-determination is only presumptive, in what

cases can it be overridden? One might think that refugees would be a clear-cut

case. Wellman, however, rejects this claim. He argues instead that a “state can

entirely fulfill its responsibilities to persecuted refugees without allowing them to

immigrate into its political community” (p. 123). For Wellman, refugees can most

likely be helped in their own state of citizenship through aid and/or humanitarian

intervention; and when that is not the case, the most that they have a right to is

some sort of temporary inclusion in the receiving state.

To be sure, assistance can take many shapes, including the shape of financial

assistance and humanitarian intervention. If such actions can, in fact, assist

refugees and similarly vulnerable individuals to lead minimally decent lives, then

states should be able to discharge their duty of assistance in whatever way they

deem fit. However, in case that assistance cannot take place at the sender state, the

temporary protection of refugees by receiving states is not enough to discharge the

duty. Temporary protection is not enough because it becomes merely a stop-gap

GLOBAL JUSTICE : THEORY PRACTICE RHETORIC (5) 2012

MORALITY IN MIGRATION: A REVIEW ESSAY 124

solution that fails to take the basic interests of refugees adequately into account.

Refugees are not only seeking a safe haven but the opportunity to start a new

life. And when they lack the knowledge of how long it will take for the situation

in their state of citizenship to improve, and cannot permanently settle in their

state of temporary residence, they are unable to plan and pursue important life

goals. A morally defensible account of the ethics of immigration must therefore

entail a duty to permanently include, at least in some cases, refugees and similarly

vulnerable individuals if they cannot be assisted in their own state of citizenship.

The case for open borders

Against Wellman, Phillip Cole defends a presumptive obligation on the part of

states to include prospective immigrants. He makes both a case for open borders

and a case against closed borders, putting forth important challenges to those

who subscribe to liberal values and wish to defend the right of states to control

membership.

Cole’s case for open borders relies on the value of the immigrant’s autonomy,

and on the idea that immigration is “an essential component of human agency,

such that it is a crucial part of the ability of people to be free and equal choosers,

doers and participators in their local, national and global communities” (p. 297).

The case against closed borders, on the other hand, rests on the alleged tension

between liberal values and exclusion. Given that the idea that persons are free

and equal is central to liberalism, Cole argues that liberal theorists who defend

the right of states to exclude “are left with two unpalatable choices: either a liberal

universalism that contradicts itself into incoherence, or a liberal realism that is

coherent and consistent, but only at the cost of abandoning the quest for morality

altogether” (p. 311).

Cole maintains that autonomy is what grounds a right to freedom of movement

at the international level, and that a state unduly infringes upon a person’s

autonomy when it refuses to include her as a member. Cole’s first point can hardly

be denied for it seems true that when we prevent a person from joining our state,

we take an option away from her, thereby reducing the range of options from

which she can autonomously choose. But we cannot conclude from this that states

must open their borders, since this depends on whether a prospective immigrant

actually has a moral claim that her autonomy be so expanded. Do all prospective

migrants have such a claim?

To begin with, it is important to note that this putative right for inclusion would

not be simply the exercise of a liberty-right on the part of the immigrant (that

is, to move freely within the recipient state), but the exercise of a claim-right

on her part—one that would create a duty for inclusion in all sorts of goods and

GLOBAL JUSTICE : THEORY PRACTICE RHETORIC (5) 2012

LUARA FERRACIOLI 125

services that are provided within the recipient state: service provisions, welfare

benefits, non-excludable goods, political participation, and so on. Given the costs

involved, the question is whether her situation creates a compelling moral case

for the citizenry to bear the costs associated with her inclusion.4 Whether or not

she has such a case depends in my view very much on the circumstances of the

political community in which she currently resides. If a prospective immigrant

can already exercise a sufficient degree of autonomy in her country of citizenship,

the simple expansion of her autonomy that is entailed by membership in a second

state does not seem to create a moral duty on the citizens of that state. The same

considerations apply to interpersonal cases. If an assailant has kidnapped you,

and I (a stranger) happen to be in a position such that I can, at moderate cost to

myself, assist you to escape, then it seems obvious that I should bear such costs

and help you. If, however, you have not been kidnapped but would instead like

my financial assistance so that you can buy a second house by the sea (thereby

expanding the choices available to you), then it does not seem that I have a duty

to expand your autonomy, even if I am rich and can assist you at very little cost

to myself.

In sum, Cole’s positive case for open borders does not take adequately into

account the distinction between the claims of those who lack the resources to

lead minimally decent lives and those who have enough to lead decent lives but

lack resources that would expand the opportunities available to them. Insofar

as inclusion gives rise to costs on the recipient state and its citizens, they would

seem to have a right to refuse to take on such costs unless doing so is necessary to

protect others from severe deprivation of autonomy.

Does Cole’s case against closed borders successfully rebut the presumptive

right to exclude? According to Cole, when liberal theories presuppose the control

of borders by the state, they become inconsistent with their moral commitment

regarding the treatment of all persons as free and equal. As he explains, “There

is no ethically grounded distinction between citizens and migrants that the

liberal state can appeal to in order to morally justify this discrimination, but as

the exclusion is necessary in order to protect self-interest, no ethically grounded

distinction is needed” (p. 310). In light of this alleged inconsistency on the part

of liberal states, he claims that only open borders will allow for liberal citizens to

realize their moral commitments.

This is an important challenge to both liberal theory and practice, and Cole’s

quest for a liberal philosophy that takes the idea of equality and freedom to its

4 For a discussion on the specific costs associated with cultural change and population grow, see David Miller, ‘Immigration:

The Case for Limits’, Contemporary Debates in Applied Ethics, eds. A. I. Cohen and C. H. Wellman (Malden, MA:

Blackwell, 2005), pp. 193-206.

GLOBAL JUSTICE : THEORY PRACTICE RHETORIC (5) 2012

MORALITY IN MIGRATION: A REVIEW ESSAY 126

radical conclusions deserves recognition. The problem with this argument is that

the alleged tension between liberal values and exclusion is substantially reduced

once we recognize that no liberal state can in fact treat all persons as free and equal.

This is because, in reality, states are incapable of providing membership to such a

large group of human beings. In other words, if ought implies can, then no state

ought to treat all human beings equally through the provision of membership. As

a matter of fact, the best the international community can hope to do is ensure

that each state does a sufficiently good job of treating its own citizens as free and

equal, and of assisting foreigners whose own states of citizenship have failed in

this task. To expect more from each state—liberal or otherwise—is to expect more

than what citizens can feasibly provide to their fellow human beings.

It is certainly true that states privilege their own interests and goals. But why

should this be problematic? The important normative point here is not that

states should never seek to protect their interests, but that they should recognize

that such aims must sometimes give way to other considerations. In the area

of immigration, for example, states can recognize a duty to take on the cost of

protecting refugees and similarly vulnerable individuals. There is no need to also

include prospective immigrants who already enjoy decent standards of living

elsewhere.

An intermediate position

In Immigration and the Constraints of Justice, Ryan Pevnick’s strategy is

twofold. First, he offers a justification for self-determination that departs from

freedom of association. Second, he advocates the right of refugees and poor

people to cross international borders. Taken together, these commit him to an

intermediate position between Wellman and Cole’s.

Pevnick follows Wellman in accepting that there is a prima facie right to exclude,

derived from the right to self-determination. But he departs from Wellman when

he claims that the right to exclude is actually grounded in a group’s ownership of

public institutions, and that the citizenry of a state has a relationship of ownership

to their institutions that is not shared by foreigners. Such a relationship evolves

from the efforts of previous members, who “passed on its institutions to current

generations as part of a trust to be taken forward to future generations” (p. 39).

Because “outsiders did not play a fundamental role in the creation of the relevant

institutions” (p. 36), they do not currently have a claim for inclusion.

However, Cole’s point that we must remember the history of racism and

colonialism when thinking about the status of our current immigration

arrangements is pertinent here (p. 160). After all, many states have the institutions

that they currently have precisely because of the direct contribution of those who

GLOBAL JUSTICE : THEORY PRACTICE RHETORIC (5) 2012

LUARA FERRACIOLI 127

have colonized them. One thinks of Brazil and Australia, for example, where

previous generations of Portuguese and British subjects played an essential role

in creating the relevant national institutions.5 Or consider contemporary Iraq,

where Britain and the United States have played a crucial role in the establishment

of the current institutional order in Iraq. If we accept Pevnick’ account, it then

follows either that American and British citizens have claims to citizenship in

Iraq, or that Iraq simply lacks the right to exclude non-members.

Pevnick’s associative ownership account could lead to two potential

interpretations, both of which seem to lead to counterintuitive results. One

interpretation suggests that current citizens of former colonial powers have a right

to become members of their former colonies, due to the contributions of previous

generations. In contrast, on a broader interpretation, only countries that have

not been colonized or whose institutions have not been shaped in some relevant

measure by outsiders have the right to exclude prospective immigrants. In either

case, we are left with the implication that the citizenry of former colonies now

have a somewhat weaker claim to self-determination in the area of immigration

than countries that were not colonized.

Pevnick’s intermediate position could become sounder, if he were to ground it

in the importance of political autonomy. However, he rejects this possibility due

to the fact that states are not voluntary associations (pp. 28–30). But note the

analogy he offers when discussing the claims of unauthorized immigrants:

A group of childhood friends each month wire money into a bank account

under an agreement that when they reach the needed sum of money, they

will together purchase a vacation home which they will then share. John,

who is not a friend of the group, seeks access to a vacation home but cannot

afford one on his own. Hearing of the above scheme, he begins to wire

money into the bank account without the agreement of the group. After the

group has raised the requisite amount of money and purchased the home,

John steps forward – produces receipts documenting his contributions –

and demands an equal place in the group (p. 165).

Pevnick concludes that, like John, unauthorized immigrants have no right

to inclusion. But note that his example suggests that what really grounds self-

determination is the value of autonomy and not past or present contribution. It is

the autonomy of members of the group that was violated by John’s contributions,

and this is true irrespective of whether he contributed in small or large amounts,

or whether “voluntary” childhood friends or “non-voluntary” family members

5 For a similar critique, but focusing on the scope of duties of distributive justice, see Lea Ypi, Robert E. Goodin & Christian

Barry, ‘Associative Duties, Global Justice and the Colonies’, Philosophy and Public Affairs 37 (2009), pp. 103-135.

GLOBAL JUSTICE : THEORY PRACTICE RHETORIC (5) 2012

MORALITY IN MIGRATION: A REVIEW ESSAY 128

were responsible for setting up the bank account. If contribution really did the

work, then John would have a claim for inclusion, as would illegal immigrants

who contribute, through labor and taxation, to the maintenance of the relevant

public institutions.

Notwithstanding problems with Pevnick’s justification of the right to self-

determination, his acknowledgement that the claims of foreigners can at times be

strong enough to trump the right of states to exclude adds an important insight to

the literature. That is, by resisting extremes of open and closed borders, Pevnick

puts forth a more nuanced account that succeeds in showing respect for both

citizens and foreigners in need. He goes even further by defending a desirable

and feasible guest worker program that, if implemented, would certainly realize

these moral goals.

Pevnick’s account focuses only on the claims of those who wish to immigrate,

and thus neglects those in the sending countries who are harmed by the departure

of their fellow citizens. While he acknowledges that “by focusing on skilled

applicants, immigration policy demonstrates disrespect for citizens of developing

countries” (p. 74), he does not take the point far enough. The account fails to

notice that by including skilled immigrants from countries where their departure

will lead to severe deprivation, recipient states foreseeably enable harm to occur

in those countries. If morality is to set limits to the right of states to develop their

own immigration policies, then surely the foreseeable harm that is enabled by

immigration policies must also constrain the amount of freedom recipient states

can legitimately exercise. The upshot here is that the right of recipient states to

include prospective immigrants can, at times, be trumped by a negative duty not

to contribute to harm in resource-deprived countries.

But how about the negative implications of this duty to those skilled workers who

would cease to enjoy the benefit of immigration? There are a couple of reasons to

think that there are no grounds for complaint here. First, these workers would not

be denied something that everybody else already enjoys, but rather, they would

be denied what is already not available to other kinds of prospective immigrants,

namely the privilege of migration (recall how the fact of political autonomy entails

that, in general, migration is a privilege and not a moral right). Second, and most

importantly, the possession of skills in resource-deprived settings endows one

with a greater capacity to assist, and this gives one a more stringent responsibility

to protect the basic interests of those in need. In other words, by denying skilled

workers entrance, recipient states would not be treating prospective immigrants

unfairly. Rather, doing so simply puts their moral claim on a par with the claim

of other kinds of prospective immigrants (un-skilled and low-skilled workers).

GLOBAL JUSTICE : THEORY PRACTICE RHETORIC (5) 2012

LUARA FERRACIOLI 129

The ethics of migration is most certainly a pressing topic in international

relations. Tackling the normative question of whether states have the right to

exclude is essential for the implementation of desirable migration arrangements

at the global level. In this essay I have illustrated that the right to exclude is best

grounded in the political autonomy of the citizenry. I have also suggested that

states have not only a positive duty to include refugees and similarly vulnerable

individuals, but that they also need to set limits on the inclusion of prospective

immigrants whose departures would lead to foreseen harm in their countries

of origin. Taken together, these duties of migration give due weight to the

basic interests of foreigners without simultaneously undermining the political

autonomy of citizens.

Dr Luara Ferracioli

Postdoctoral Research Associate

Woodrow Wilson School of Public and

International Affairs

Princeton University

email: luaraf@princeton.edu

GLOBAL JUSTICE : THEORY PRACTICE RHETORIC (5) 2012

You might also like

- FOE ReviewerDocument80 pagesFOE ReviewerNikko Tolentino100% (10)

- Blake, Michael, Immigration, Jurisdiction and Exclusion PDFDocument28 pagesBlake, Michael, Immigration, Jurisdiction and Exclusion PDFIvaan' Alekqine100% (2)

- Do States Have A Moral Obligation To ObeyDocument21 pagesDo States Have A Moral Obligation To Obeypocotopc1No ratings yet

- The Challenge of Globalization On Citizenship: Topic 10Document26 pagesThe Challenge of Globalization On Citizenship: Topic 10Eleonor ClaveriaNo ratings yet

- Representative Democracy: The Constitutional Theory of Campaign Finance ReformDocument136 pagesRepresentative Democracy: The Constitutional Theory of Campaign Finance ReformRob streetmanNo ratings yet

- Political Obligation Short NotesDocument4 pagesPolitical Obligation Short NotesDivya SkaterNo ratings yet

- The Promise of Human Rights: Constitutional Government, Democratic Legitimacy, and International LawFrom EverandThe Promise of Human Rights: Constitutional Government, Democratic Legitimacy, and International LawNo ratings yet

- International Law.Document3 pagesInternational Law.Mehak FatimaNo ratings yet

- Globalization and The Theory of International LawDocument13 pagesGlobalization and The Theory of International LawMidha MoeenNo ratings yet

- Political ObligationDocument4 pagesPolitical Obligationtejukaki0No ratings yet

- Souverei Global WorldDocument14 pagesSouverei Global WorldЕкатерина ЦегельникNo ratings yet

- Direct Democracy - Government of The People by The People and FoDocument9 pagesDirect Democracy - Government of The People by The People and FoHuy NguyenNo ratings yet

- Why Do States Mostly Obey International LawDocument11 pagesWhy Do States Mostly Obey International Lawsurajalure44No ratings yet

- Carens - Who Should Get inDocument16 pagesCarens - Who Should Get inJoel CruzNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Global Justice: Central QuestionsDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Global Justice: Central QuestionsRangoli NagendraNo ratings yet

- Migration+and+Justice+ +a+Reply+to+My+CriticsDocument11 pagesMigration+and+Justice+ +a+Reply+to+My+CriticsDanyNo ratings yet

- Migration in Legal and Political Theory, Eds. Sarah Fine and Lea Ypi (Oxford, Forthcoming)Document17 pagesMigration in Legal and Political Theory, Eds. Sarah Fine and Lea Ypi (Oxford, Forthcoming)text7textNo ratings yet

- The Authority of Human RightsDocument34 pagesThe Authority of Human Rightswanjiruirene3854No ratings yet

- Critics To The Critical Legal StudiesDocument9 pagesCritics To The Critical Legal StudiesJuan MateusNo ratings yet

- Transnational Human Rights ObligationsDocument18 pagesTransnational Human Rights ObligationsAngraj SeebaruthNo ratings yet

- The War of Law - How New International Law Undermines Democratic SovereigntyDocument14 pagesThe War of Law - How New International Law Undermines Democratic SovereigntyGul BarecNo ratings yet

- LiberalismDocument4 pagesLiberalismIsrar AhmedNo ratings yet

- Introduction: Human Rights in The Study of Politics: David BeethamDocument9 pagesIntroduction: Human Rights in The Study of Politics: David BeethamHafiz ShoaibNo ratings yet

- Int J Constitutional Law 2013 Hirschl 1 12Document12 pagesInt J Constitutional Law 2013 Hirschl 1 12jjjvvvsssNo ratings yet

- The Limits of International LawDocument272 pagesThe Limits of International LawClifford Angell Bates100% (2)

- Introduction To The History, Theory and Politics of Constitutional LawDocument14 pagesIntroduction To The History, Theory and Politics of Constitutional LawsamiNo ratings yet

- Public International Law NoteDocument67 pagesPublic International Law NoteKalewold GetuNo ratings yet

- State Sovereignty Research PapersDocument6 pagesState Sovereignty Research Papersc9kb0esz100% (1)

- Global Justice: HistoryDocument7 pagesGlobal Justice: HistorymirmoinulNo ratings yet

- The Ancient and Modern Thinking About JusticeDocument22 pagesThe Ancient and Modern Thinking About JusticeAditi SinhaNo ratings yet

- 2 AcDocument15 pages2 AcChristian GinesNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Human Rights: Feature ReviewDocument14 pagesThe Politics of Human Rights: Feature ReviewFareha Quddus KhanNo ratings yet

- LD - JanFebDocument112 pagesLD - JanFebGilly FalinNo ratings yet

- The Critical Legal Studies Movement: Another Time, A Greater TaskFrom EverandThe Critical Legal Studies Movement: Another Time, A Greater TaskRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Constitutional LawDocument4 pagesConstitutional LawYassir MalikNo ratings yet

- Critical Legal StudiesDocument3 pagesCritical Legal StudiesPriyambada Das50% (2)

- Miller-2008-Journal of Political PhilosophyDocument20 pagesMiller-2008-Journal of Political PhilosophyfaignacioNo ratings yet

- S S: W H I L W W C: Ymmetry and Electivity HAT Appens in Nternational AWDocument52 pagesS S: W H I L W W C: Ymmetry and Electivity HAT Appens in Nternational AWNyasclemNo ratings yet

- ELE AffirmativeDocument6 pagesELE AffirmativeCedric ZhouNo ratings yet

- American Government (2pg)Document9 pagesAmerican Government (2pg)Kevin KibugiNo ratings yet

- Colonization and The Rule of Law - Comparing The Effectiveness ofDocument46 pagesColonization and The Rule of Law - Comparing The Effectiveness ofdip-law-70-22No ratings yet

- We Affirm The Resolution Today: Resolved: Birthright Citizenship Should Be Abolished in The United StatesDocument4 pagesWe Affirm The Resolution Today: Resolved: Birthright Citizenship Should Be Abolished in The United StatesRyan JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Do States Have A Moral Obligation To Obey International LawDocument20 pagesDo States Have A Moral Obligation To Obey International LawNatalia Torres ZunigaNo ratings yet

- The 4th Branch of GovernmentDocument16 pagesThe 4th Branch of GovernmentAndrei-Valentin BacrăuNo ratings yet

- Fedarel Goverment of IndiaDocument6 pagesFedarel Goverment of IndiaMarsum Akther HossainNo ratings yet

- What Are Human RightsDocument3 pagesWhat Are Human RightsAlejandro GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Constitution Research Paper TopicsDocument4 pagesConstitution Research Paper Topicsxfeivdsif100% (1)

- Colle Anglais 1Document3 pagesColle Anglais 1yanil2005No ratings yet

- A Political Theology For A Civil Religion - Paul KahnDocument28 pagesA Political Theology For A Civil Religion - Paul KahnAnonymous eDvzmvNo ratings yet

- Libfile - Repository - Content - Law, Society and Economics Working Papers - 2013 - WPS2013-12 - ThomasDocument33 pagesLibfile - Repository - Content - Law, Society and Economics Working Papers - 2013 - WPS2013-12 - ThomasDoreen AaronNo ratings yet

- CSS Criminology Notes - Basic Concept in CriminologyDocument6 pagesCSS Criminology Notes - Basic Concept in CriminologyMurtaza Meer VistroNo ratings yet

- Midterm EIP KastratiDocument4 pagesMidterm EIP KastratiYllka KastratiNo ratings yet

- From Parchment to Dust: The Case for Constitutional SkepticismFrom EverandFrom Parchment to Dust: The Case for Constitutional SkepticismNo ratings yet

- Studying PoliticsDocument20 pagesStudying PoliticsRicardo Aníbal Rivera GallardoNo ratings yet

- Barney's Lay NCDocument5 pagesBarney's Lay NCGiovanni GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Internat PDFDocument11 pagesInternat PDFfisicanasserNo ratings yet

- Ghai - Ethnic Diversity and ConstitutionalismDocument23 pagesGhai - Ethnic Diversity and ConstitutionalismOllivellNo ratings yet

- Cards 1Document4 pagesCards 1moaokkNo ratings yet

- Democracy On The LamDocument21 pagesDemocracy On The LamVth SkhNo ratings yet

- What Is ArtDocument3 pagesWhat Is ArtJo CNo ratings yet

- How To Analyse A PoemDocument2 pagesHow To Analyse A PoemJo CNo ratings yet

- Objective: To Analyse The Writer's Intentions Through The Representations of Characters in The Context of The NarrativeDocument9 pagesObjective: To Analyse The Writer's Intentions Through The Representations of Characters in The Context of The NarrativeJo C100% (1)

- LDP Sparks Tle - Worksheets Et Pistes de Réponse Vierges - Chap 15Document9 pagesLDP Sparks Tle - Worksheets Et Pistes de Réponse Vierges - Chap 15Jo CNo ratings yet

- MYP4-5 War-Photographer-Annotated - Correction War PoetryDocument1 pageMYP4-5 War-Photographer-Annotated - Correction War PoetryJo C100% (1)

- Practice Paper Revision SocialDocument2 pagesPractice Paper Revision SocialHussain AbbasNo ratings yet

- SouthWest Candidates For European Elections 2009Document2 pagesSouthWest Candidates For European Elections 2009James Barlow100% (1)

- PSI Facility - CordesDocument2 pagesPSI Facility - CordesMichael EvermanNo ratings yet

- Commercial Law (Dean Sundiang)Document17 pagesCommercial Law (Dean Sundiang)Gee GuevarraNo ratings yet

- LT E-Bill Shop 7 17sept 2019Document2 pagesLT E-Bill Shop 7 17sept 2019John Smith0% (1)

- The Benefit of The Doubt TextDocument11 pagesThe Benefit of The Doubt TextAreen KumarNo ratings yet

- 4th Year SDP Seating PlanDocument1 page4th Year SDP Seating PlanShuvendu ShilNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Officer Taking Deposition - SAMPLE FOR ACADEMIC USE ONLYDocument4 pagesCertificate of Officer Taking Deposition - SAMPLE FOR ACADEMIC USE ONLYEJ CruzNo ratings yet

- ETHICSDocument4 pagesETHICSReginald AgcambotNo ratings yet

- 1ST-NMCC-BROCHURE 20231123 165119 0000 CompressedDocument31 pages1ST-NMCC-BROCHURE 20231123 165119 0000 CompressedEshanNo ratings yet

- CGH AS BUILT Floor PlanDocument1 pageCGH AS BUILT Floor PlanMary FelicianoNo ratings yet

- Land Sale AgreementDocument4 pagesLand Sale AgreementHollyfatNo ratings yet

- PR-M/PR-F Series: Self-Contained Miniture Photoelectric SensorDocument3 pagesPR-M/PR-F Series: Self-Contained Miniture Photoelectric SensorThinh phan thanhNo ratings yet

- Power and Influence Case THOMAS GREEN Fall 2018 1Document29 pagesPower and Influence Case THOMAS GREEN Fall 2018 1suggestionboxNo ratings yet

- 151-Article Text-953-2-10-20230105Document8 pages151-Article Text-953-2-10-20230105indilstree22No ratings yet

- Geutebrueck Solutions Overview (Vestera)Document41 pagesGeutebrueck Solutions Overview (Vestera)Ahmad ImranNo ratings yet

- Companies Act 2013: Meaning of A CompanyDocument7 pagesCompanies Act 2013: Meaning of A CompanyMohit RanaNo ratings yet

- Transportation Laws: Instructions: Read Each Item Carefully Before Answering. Answer TheDocument5 pagesTransportation Laws: Instructions: Read Each Item Carefully Before Answering. Answer TheRikka ReyesNo ratings yet

- 1204 1980Document6 pages1204 1980Fabio MiguelNo ratings yet

- Topic 9 ThermodynamicsDocument4 pagesTopic 9 ThermodynamicsTengku Lina IzzatiNo ratings yet

- Braeckman, Niklas Luhmann's Systems Theoretical Redescription of The Inclusionexclusion Debate, 2006Document24 pagesBraeckman, Niklas Luhmann's Systems Theoretical Redescription of The Inclusionexclusion Debate, 2006Juan AhumadaNo ratings yet

- Code of Practice For Temporary Traffic Management (Copttm) : Traffic Control Devices ManualDocument114 pagesCode of Practice For Temporary Traffic Management (Copttm) : Traffic Control Devices ManualBen SuttonNo ratings yet

- Intellectual CapitalDocument3 pagesIntellectual CapitalMd Mehedi HasanNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Computation of MarksDocument5 pagesGuidelines For Computation of MarksLoolik SoliNo ratings yet

- The Criminal Law of The Consumer Protection On Sale Buy Online Through Mass MediaDocument9 pagesThe Criminal Law of The Consumer Protection On Sale Buy Online Through Mass MediaMaica ManguiatNo ratings yet

- Marketing Schedule: JanuaryDocument14 pagesMarketing Schedule: JanuaryKen CarrollNo ratings yet

- Sample AgreementDocument26 pagesSample AgreementSteamhouse InternNo ratings yet

- (U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictDocument5 pages(U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictFauquier NowNo ratings yet

- Sayani 19 WBCSDocument3 pagesSayani 19 WBCSSayonie BoseNo ratings yet