Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

11 viewsVolcano Historiees

Volcano Historiees

Uploaded by

Kissha TayagCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- How Do Volcanoes Form?: Popular StoriesDocument5 pagesHow Do Volcanoes Form?: Popular Storiesshuraj k.c.No ratings yet

- What Is A Volcano?Document4 pagesWhat Is A Volcano?Sriram SusarlaNo ratings yet

- What Happens Before and After Volcanoes Erupt? Geology for Kids | Children's Earth Sciences BooksFrom EverandWhat Happens Before and After Volcanoes Erupt? Geology for Kids | Children's Earth Sciences BooksNo ratings yet

- VulcanosDocument2 pagesVulcanosdarinholmesxNo ratings yet

- Activity 1 Volcano EssayDocument1 pageActivity 1 Volcano EssayMariel ParagasNo ratings yet

- Volcanic EruptionsDocument4 pagesVolcanic EruptionsLovey MasilaneNo ratings yet

- All About VolcanoDocument7 pagesAll About VolcanoRi RiNo ratings yet

- The Beauty and Danger of A Volcano by ChiongDocument3 pagesThe Beauty and Danger of A Volcano by ChiongCHIONG, ABEGAIL, T.No ratings yet

- Kaboom! What Happens When Volcanoes Erupt? Geology for Beginners | Children's Geology BooksFrom EverandKaboom! What Happens When Volcanoes Erupt? Geology for Beginners | Children's Geology BooksNo ratings yet

- VolcanoesDocument6 pagesVolcanoesRoger Corre RivaNo ratings yet

- 06/17/2021 Add A Footer 1Document40 pages06/17/2021 Add A Footer 1Roccie Dawn MisaNo ratings yet

- Fun Facts About Tectonic Plates For KDocument8 pagesFun Facts About Tectonic Plates For KViorel MaresNo ratings yet

- Volcano ReadingsDocument16 pagesVolcano Readingsapi-251355123No ratings yet

- VolcanoesDocument5 pagesVolcanoesapi-590510818No ratings yet

- The Explosive World of Volcanoes with Max Axiom Super Scientist: 4D An Augmented Reading Science ExperienceFrom EverandThe Explosive World of Volcanoes with Max Axiom Super Scientist: 4D An Augmented Reading Science ExperienceNo ratings yet

- Types of VolcanoesDocument21 pagesTypes of VolcanoesAgaManlapazMacasaquitNo ratings yet

- Dramatic VolcanicDocument2 pagesDramatic VolcanicbNo ratings yet

- English Songs For Children Book 3a English Songs For Children 2aDocument12 pagesEnglish Songs For Children Book 3a English Songs For Children 2asusannatitusNo ratings yet

- What I KnowDocument2 pagesWhat I KnowAcademic ServicesNo ratings yet

- P PPPPPP P: P PP PP P' P P PP' P $P' P P ('P P"Document4 pagesP PPPPPP P: P PP PP P' P P PP' P $P' P P ('P P"bpmojapeloNo ratings yet

- Ring of FireDocument3 pagesRing of FireBen Hemert G. Jumao-asNo ratings yet

- VolcanoDocument88 pagesVolcanoumzzNo ratings yet

- ESCI Plate Tectonics and The Ring of FireDocument2 pagesESCI Plate Tectonics and The Ring of FireSam VilladelgadoNo ratings yet

- What Happens When A Volcano Erupts 4151722Document17 pagesWhat Happens When A Volcano Erupts 4151722Amay SuryadiNo ratings yet

- How Many Volcanoes Are There in The World?: This Question Look HereDocument4 pagesHow Many Volcanoes Are There in The World?: This Question Look HereNhoj Kram AlitnacnosallivNo ratings yet

- Term Paper About Volcanic EruptionDocument8 pagesTerm Paper About Volcanic Eruptionafdtnybjp100% (1)

- I and S Volcano ReportDocument7 pagesI and S Volcano ReportJASMSJS SkskdjNo ratings yet

- Volcanic EruptionsDocument4 pagesVolcanic Eruptionspatrick201050428No ratings yet

- Volcanic Hazards NotesDocument8 pagesVolcanic Hazards NotesDorilly BullecerNo ratings yet

- Earth Science Midterm Lesson 2-2022Document44 pagesEarth Science Midterm Lesson 2-2022April Rose MarasiganNo ratings yet

- Distribution of VolcanoesDocument9 pagesDistribution of VolcanoesRavi MothoorNo ratings yet

- Geography?Document13 pagesGeography?haneefa yusufNo ratings yet

- Mount Pinatubo's Eruption On June 15, 1991: Where Does This Kind of Event Occur?Document4 pagesMount Pinatubo's Eruption On June 15, 1991: Where Does This Kind of Event Occur?Angela HabaradasNo ratings yet

- VOLCANO NotesDocument17 pagesVOLCANO NotesAlexander LahipNo ratings yet

- Volcanoes The Ultimate Book: Experience the Heat, Power, and Beauty of VolcanoesFrom EverandVolcanoes The Ultimate Book: Experience the Heat, Power, and Beauty of VolcanoesNo ratings yet

- VolcanoesDocument49 pagesVolcanoesJuan Sebastian Bohorquez RozoNo ratings yet

- Volcanoes - The Fiery Wonders of The EarthDocument2 pagesVolcanoes - The Fiery Wonders of The EarthMarcos MartinezNo ratings yet

- Volcanic Eruption - BrochureDocument5 pagesVolcanic Eruption - BrochureAngelo Justine ZaraspeNo ratings yet

- Mountains of Fire: Exploring the Science of Volcanoes: The Science of Natural Disasters For KidsFrom EverandMountains of Fire: Exploring the Science of Volcanoes: The Science of Natural Disasters For KidsNo ratings yet

- Hazardous EnvironmentsDocument2 pagesHazardous Environmentstanatswagendere1No ratings yet

- VolvanoDocument6 pagesVolvanoZarinaNo ratings yet

- VolcanoDocument5 pagesVolcanokirthmolosNo ratings yet

- Geography Note Grade 8Document7 pagesGeography Note Grade 8hasanNo ratings yet

- Volcanoes, Earthquakes & TsunamisDocument115 pagesVolcanoes, Earthquakes & TsunamisKarl Ó Broin100% (1)

- Pacific Ring of FireDocument20 pagesPacific Ring of FireDwi Mulyono100% (1)

- Sust2701 GalapexDocument24 pagesSust2701 Galapexapi-283747608No ratings yet

- DISASTER-MANAGEMENT NotesDocument75 pagesDISASTER-MANAGEMENT NotesDeepak PrajapatNo ratings yet

- Natural Disasters: Investigate Earth's Most Destructive Forces with 25 ProjectsFrom EverandNatural Disasters: Investigate Earth's Most Destructive Forces with 25 ProjectsNo ratings yet

- Yashi Projecy On DisasterDocument11 pagesYashi Projecy On DisasterAnuj BaderiyaNo ratings yet

- Volcanoes - CSS General Science & Ability NotesDocument4 pagesVolcanoes - CSS General Science & Ability NotesajqaziNo ratings yet

- Ring of FireDocument4 pagesRing of Firemira01No ratings yet

- Mall of Asia ManilaDocument43 pagesMall of Asia ManilaEmil BarengNo ratings yet

- Bio and HealthDocument5 pagesBio and HealthKissha TayagNo ratings yet

- BiodiversityDocument3 pagesBiodiversityKissha TayagNo ratings yet

- SCIDocument3 pagesSCIKissha TayagNo ratings yet

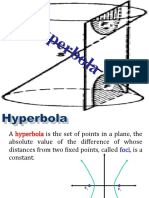

- HyperbolaDocument45 pagesHyperbolaKissha TayagNo ratings yet

- Week 013 Graphs of Circular Functions and SituationalDocument24 pagesWeek 013 Graphs of Circular Functions and SituationalKissha TayagNo ratings yet

- Week 005-Presentation Key Concepts of Inverse Functions, Exponential Functions and Logarithmic Functions Part 002Document26 pagesWeek 005-Presentation Key Concepts of Inverse Functions, Exponential Functions and Logarithmic Functions Part 002Kissha TayagNo ratings yet

- Week 001-Presentation Key Concepts of FunctionsDocument28 pagesWeek 001-Presentation Key Concepts of FunctionsKissha TayagNo ratings yet

Volcano Historiees

Volcano Historiees

Uploaded by

Kissha Tayag0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

11 views4 pagesOriginal Title

volcano historiees

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

11 views4 pagesVolcano Historiees

Volcano Historiees

Uploaded by

Kissha TayagCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 4

REFERENCE

Volcanoes, explained

These fiery peaks have belched up molten rock, hot ash, and gas

since Earth formed billions of years ago.

BY MAYA WEI-HAAS

PUBLISHED JANUARY 15, 2018

The Tungurahua volcano erupts in the night. Tungurahua, also called the Black Giant, is one of

Ecuador's most active volcanoes.

PHOTOGRAPH BY AMMIT/ ALAMY

Volcanoes are Earth's geologic architects. They've created more than 80

percentof our planet's surface, laying the foundation that has allowed

life to thrive. Their explosive force crafts mountains as well as craters.

Lava rivers spread into bleak landscapes. But as time ticks by, the

elements break down these volcanic rocks, liberating nutrients from

their stony prisons and creating remarkably fertile soils that have

allowed civilizations to flourish.

There are volcanoes on every continent, even Antarctica. Some 1,500

volcanoes are still considered potentially active around the world

today; 161 of those—over 10 percent—sit within the boundaries of the

United States.

But each volcano is different. Some burst to life in explosive eruptions,

like the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo, and others burp rivers of lava

in what's known as an effusive eruption, like the 2018 activity of

Hawaii's Kilauea volcano. These differences are all thanks to

the chemistry driving the molten activity. Effusive eruptions are more

common when the magma is less viscous, or runny, which allows gas to

escape and the magma to flow down the volcano's slopes. Explosive

eruptions, however, happen when viscous molten rock traps the gasses,

building pressure until it violently breaks free.

How do volcanoes form?

The majority of volcanoes in the world form along the boundaries of

Earth's tectonic plates—massive expanses of our planet's lithosphere

that continually shift, bumping into one another. When tectonic plates

collide, one often plunges deep below the other in what's known as a

subduction zone.

As the descending landmass sinks...

Read the rest of this article on NatGeo.com

FOLLOW US

CHILDREN'S ONLINE PRIVACY POLICY

DO NOT SELL MY PERSONAL INFORMATION

INTEREST-BASED ADS

PRIVACY POLICY - UPDATED

TERMS OF USE

YOUR CALIFORNIA PRIVACY RIGHTS

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society.

Copyright © 2015-2022 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Subscribe for full access to read stories from National Geographic.

You might also like

- How Do Volcanoes Form?: Popular StoriesDocument5 pagesHow Do Volcanoes Form?: Popular Storiesshuraj k.c.No ratings yet

- What Is A Volcano?Document4 pagesWhat Is A Volcano?Sriram SusarlaNo ratings yet

- What Happens Before and After Volcanoes Erupt? Geology for Kids | Children's Earth Sciences BooksFrom EverandWhat Happens Before and After Volcanoes Erupt? Geology for Kids | Children's Earth Sciences BooksNo ratings yet

- VulcanosDocument2 pagesVulcanosdarinholmesxNo ratings yet

- Activity 1 Volcano EssayDocument1 pageActivity 1 Volcano EssayMariel ParagasNo ratings yet

- Volcanic EruptionsDocument4 pagesVolcanic EruptionsLovey MasilaneNo ratings yet

- All About VolcanoDocument7 pagesAll About VolcanoRi RiNo ratings yet

- The Beauty and Danger of A Volcano by ChiongDocument3 pagesThe Beauty and Danger of A Volcano by ChiongCHIONG, ABEGAIL, T.No ratings yet

- Kaboom! What Happens When Volcanoes Erupt? Geology for Beginners | Children's Geology BooksFrom EverandKaboom! What Happens When Volcanoes Erupt? Geology for Beginners | Children's Geology BooksNo ratings yet

- VolcanoesDocument6 pagesVolcanoesRoger Corre RivaNo ratings yet

- 06/17/2021 Add A Footer 1Document40 pages06/17/2021 Add A Footer 1Roccie Dawn MisaNo ratings yet

- Fun Facts About Tectonic Plates For KDocument8 pagesFun Facts About Tectonic Plates For KViorel MaresNo ratings yet

- Volcano ReadingsDocument16 pagesVolcano Readingsapi-251355123No ratings yet

- VolcanoesDocument5 pagesVolcanoesapi-590510818No ratings yet

- The Explosive World of Volcanoes with Max Axiom Super Scientist: 4D An Augmented Reading Science ExperienceFrom EverandThe Explosive World of Volcanoes with Max Axiom Super Scientist: 4D An Augmented Reading Science ExperienceNo ratings yet

- Types of VolcanoesDocument21 pagesTypes of VolcanoesAgaManlapazMacasaquitNo ratings yet

- Dramatic VolcanicDocument2 pagesDramatic VolcanicbNo ratings yet

- English Songs For Children Book 3a English Songs For Children 2aDocument12 pagesEnglish Songs For Children Book 3a English Songs For Children 2asusannatitusNo ratings yet

- What I KnowDocument2 pagesWhat I KnowAcademic ServicesNo ratings yet

- P PPPPPP P: P PP PP P' P P PP' P $P' P P ('P P"Document4 pagesP PPPPPP P: P PP PP P' P P PP' P $P' P P ('P P"bpmojapeloNo ratings yet

- Ring of FireDocument3 pagesRing of FireBen Hemert G. Jumao-asNo ratings yet

- VolcanoDocument88 pagesVolcanoumzzNo ratings yet

- ESCI Plate Tectonics and The Ring of FireDocument2 pagesESCI Plate Tectonics and The Ring of FireSam VilladelgadoNo ratings yet

- What Happens When A Volcano Erupts 4151722Document17 pagesWhat Happens When A Volcano Erupts 4151722Amay SuryadiNo ratings yet

- How Many Volcanoes Are There in The World?: This Question Look HereDocument4 pagesHow Many Volcanoes Are There in The World?: This Question Look HereNhoj Kram AlitnacnosallivNo ratings yet

- Term Paper About Volcanic EruptionDocument8 pagesTerm Paper About Volcanic Eruptionafdtnybjp100% (1)

- I and S Volcano ReportDocument7 pagesI and S Volcano ReportJASMSJS SkskdjNo ratings yet

- Volcanic EruptionsDocument4 pagesVolcanic Eruptionspatrick201050428No ratings yet

- Volcanic Hazards NotesDocument8 pagesVolcanic Hazards NotesDorilly BullecerNo ratings yet

- Earth Science Midterm Lesson 2-2022Document44 pagesEarth Science Midterm Lesson 2-2022April Rose MarasiganNo ratings yet

- Distribution of VolcanoesDocument9 pagesDistribution of VolcanoesRavi MothoorNo ratings yet

- Geography?Document13 pagesGeography?haneefa yusufNo ratings yet

- Mount Pinatubo's Eruption On June 15, 1991: Where Does This Kind of Event Occur?Document4 pagesMount Pinatubo's Eruption On June 15, 1991: Where Does This Kind of Event Occur?Angela HabaradasNo ratings yet

- VOLCANO NotesDocument17 pagesVOLCANO NotesAlexander LahipNo ratings yet

- Volcanoes The Ultimate Book: Experience the Heat, Power, and Beauty of VolcanoesFrom EverandVolcanoes The Ultimate Book: Experience the Heat, Power, and Beauty of VolcanoesNo ratings yet

- VolcanoesDocument49 pagesVolcanoesJuan Sebastian Bohorquez RozoNo ratings yet

- Volcanoes - The Fiery Wonders of The EarthDocument2 pagesVolcanoes - The Fiery Wonders of The EarthMarcos MartinezNo ratings yet

- Volcanic Eruption - BrochureDocument5 pagesVolcanic Eruption - BrochureAngelo Justine ZaraspeNo ratings yet

- Mountains of Fire: Exploring the Science of Volcanoes: The Science of Natural Disasters For KidsFrom EverandMountains of Fire: Exploring the Science of Volcanoes: The Science of Natural Disasters For KidsNo ratings yet

- Hazardous EnvironmentsDocument2 pagesHazardous Environmentstanatswagendere1No ratings yet

- VolvanoDocument6 pagesVolvanoZarinaNo ratings yet

- VolcanoDocument5 pagesVolcanokirthmolosNo ratings yet

- Geography Note Grade 8Document7 pagesGeography Note Grade 8hasanNo ratings yet

- Volcanoes, Earthquakes & TsunamisDocument115 pagesVolcanoes, Earthquakes & TsunamisKarl Ó Broin100% (1)

- Pacific Ring of FireDocument20 pagesPacific Ring of FireDwi Mulyono100% (1)

- Sust2701 GalapexDocument24 pagesSust2701 Galapexapi-283747608No ratings yet

- DISASTER-MANAGEMENT NotesDocument75 pagesDISASTER-MANAGEMENT NotesDeepak PrajapatNo ratings yet

- Natural Disasters: Investigate Earth's Most Destructive Forces with 25 ProjectsFrom EverandNatural Disasters: Investigate Earth's Most Destructive Forces with 25 ProjectsNo ratings yet

- Yashi Projecy On DisasterDocument11 pagesYashi Projecy On DisasterAnuj BaderiyaNo ratings yet

- Volcanoes - CSS General Science & Ability NotesDocument4 pagesVolcanoes - CSS General Science & Ability NotesajqaziNo ratings yet

- Ring of FireDocument4 pagesRing of Firemira01No ratings yet

- Mall of Asia ManilaDocument43 pagesMall of Asia ManilaEmil BarengNo ratings yet

- Bio and HealthDocument5 pagesBio and HealthKissha TayagNo ratings yet

- BiodiversityDocument3 pagesBiodiversityKissha TayagNo ratings yet

- SCIDocument3 pagesSCIKissha TayagNo ratings yet

- HyperbolaDocument45 pagesHyperbolaKissha TayagNo ratings yet

- Week 013 Graphs of Circular Functions and SituationalDocument24 pagesWeek 013 Graphs of Circular Functions and SituationalKissha TayagNo ratings yet

- Week 005-Presentation Key Concepts of Inverse Functions, Exponential Functions and Logarithmic Functions Part 002Document26 pagesWeek 005-Presentation Key Concepts of Inverse Functions, Exponential Functions and Logarithmic Functions Part 002Kissha TayagNo ratings yet

- Week 001-Presentation Key Concepts of FunctionsDocument28 pagesWeek 001-Presentation Key Concepts of FunctionsKissha TayagNo ratings yet