Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Narrating Truths of Turmoil: 'Metanarratives' From A Con Ict Analysis Perspective

Narrating Truths of Turmoil: 'Metanarratives' From A Con Ict Analysis Perspective

Uploaded by

Desi NoobsOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Narrating Truths of Turmoil: 'Metanarratives' From A Con Ict Analysis Perspective

Narrating Truths of Turmoil: 'Metanarratives' From A Con Ict Analysis Perspective

Uploaded by

Desi NoobsCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/335338027

Narrating Truths of Turmoil: 'Metanarratives' from a Conflict Analysis

perspective

Chapter · August 2017

CITATIONS READS

0 201

2 authors, including:

Maneesha Wanasinghe-Pasqual

University of Colombo

3 PUBLICATIONS 1 CITATION

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Women, Trauma and Peacebuilding Research Project View project

Could your love last their lifetime?: an exploration into challenges faced by parents of disabled children in Sri Lanka View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Maneesha Wanasinghe-Pasqual on 23 August 2019.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Narrating Truths of Turmoil: ‘Metanarratives’ from a Conflict Analysis perspective

By

Dr. Maneesha S. Wanasinghe – Pasqual

Every conflict has a history, or metanarratives, and personal narratives that tell of direct or indirect

experiences that have emotional resonance with the conflict. While a war is waged in a particular

present, it must be remembered that it is also being waged with the past using the emotions and

memories of the people. Strategically enhancing, excluding, and ignoring certain experiences and

aspects of history, conflicts attempt to create, increase, and continue an ‘us’- ‘them’ dichotomy.

The more intense the conflict, the more emotionally charged is this fight to inculcate the people

with what is acceptable as the history of the people.

Main Questions

This article deals predominantly with an explanation of the term ‘Metanarrative’ with

regard to its different meanings. Moreover, this article attempts to introduce the term ‘competing

metanarratives’. Broadly, a ‘competing metanarrative’ can emerge due to the need of one group to

have an identity separate from another. Indeed, developing one’s own identity in itself is not

negative since most of these narratives are intertwined and help create a sense of unity. Rather,

metanarratives that emphasize the differences between the groups, deliberately highlighting certain

events and justify one group’s claims over another, can create and increase stereotypes. This occurs

even prior to the escalation of tensions to the point of conflict, when the hegemonic metanarrative

– the history of the people or of the nation – is challenged by these groups.

DR. MANEESHA S. WANASINGHE – PASQUAL 1

What are Narratives?

It is possible to say that a narrative “is what constitutes the community, its activities, and

its coherence in the first place” (Carr, 1997: 20). Van Peer and Chatman describe narrative as “texts

about events structured in time. They are about agents who act in real or fictional worlds,

responding to their inner drives as well as to external circumstances” (van Peer and Chatman,

2001: 2). They do not mirror (Carr, 1997: 20). Narratives are thus relative, anchored by both

temporal and special concerns. And it also “depends on the storyteller and the audience” (Carr,

1997: 13). But here, there arises questions regarding the storyteller and the audience. For example,

who defines these narratives? Should there always be a storyteller and, if so, is this storyteller

always someone in a position of power? For example, is the storyteller a political or religious

leader, or an academic, as was Prof. Thambaiah whose seminal work on the Buddhism in Sri Lanka

still influences how the international community views the conflict within the island nation (1992).

The legitimacy granted to him stemmed not only from being a respected academic but also because

of his ethnicity, religion and citizenship.

Accordingly, “narrativists like to emphasize the crucial role that stories play in socializing

people into accepted ways of acting, thinking, and perceiving. (…) [and t]he narratives of the

powerful tend to be, by definition, privileged and hegemonic” (Hinchman and Hinchman, 1997:

235). Furthermore, every “narrative constructions typically require a supporting case ……”

(Gergen and Gergen, 1997: 178) and therefore requires an audience. In Thambiah’s case, the

audience was not the Buddhists within Sri Lanka but the international community, to compel them

to abhor the actions committed against Tamils in Sri Lanka. According to Carr, there are actually

three features of narrative – the set of events, the audience and the authority or legitimacy of the

storyteller (1997).

DR. MANEESHA S. WANASINGHE – PASQUAL 2

Then again, at times the storyteller can have a quasi-future, a notion of belonging above or

beyond the story. So while the position of the teller of the story is essential, it is as important as

that of the characters and the audience (Carr, 1997). Yet, in answering the question, should there

always be an author to a narrative, it is cautiously presented here that an author is not a pre-requisite

for narrative to function. Ethnography, for example, is “a form of collaborative storytelling which

has no real author” (Hinchman and Hinchman, 1997: 237). However, while narratives may not

always have a specific author, there is an author, an audience, and a story. In searching for textual

sources, both primary and secondary, it was found that some narratives did not have an author as

such but did certainly have an audience.

What are Metanarratives

The term Metanarrative is used in this article to describe the history of a people or a nation.

It is actually used interchangeably. This history is neither the personal history of an individual

(since it is far larger in scope than that of a single person) nor is it limited to the lifetime of a single

person. Metanarratives are mostly expressed chronologically, sometimes as myth and sometimes

as chronicles, epics or annals. They are preserved through written texts or oral traditions and

usually presented as stories of kings and great generals, of religious leaders, of gods, and of wars

and victories. But nonetheless, the history or metanarrative is the history of a people, a social

group. At times, archeological findings help re-interpret or emphasize the ‘truth’ in the traditional

metanarrative.

A history or metanarrative is believed to be factual, to be real, and is often undisputed by

the people whose history it depicts. Often, a metanarrative of a country or of a nation tells the

history of a specific people, an ethnic group or of a religious group. It does not emphasize the

DR. MANEESHA S. WANASINGHE – PASQUAL 3

historical background of all the people that constitute the country. This history of one group, often

the majority of the population, is therefore hegemonic. This hegemonic history is often considered

the ‘national history’ or the ‘official history’ or the ‘true history’ of nation or of the people. It

enlightens the people of their origin and their past, of wars fought to protect the people and the

land, of victories and losses, of traitors, heroes and enemies. This is then inculcated to children

through formal, informal and non-formal education (Wanasinghe – Pasqual, 2002 unpublished).

Hence, it is often synonymous with the identity of that group’s members but is accepted and learnt

others living within that society.

It is important to note that a history does not belong to all the people in a multi-cultural

society. That is, there are many groups whose histories are not included in the official

metanarrative. Their histories are marginalized and their own history, of their own kings or of their

own victories is excluded. In Sri Lanka, for example, the history of aborigine Veddas is not

incorporated in the official history. This is due primarily to the fact that the Vedda history has been

an oral history. Their history however is related from the perspective of the official history and

that is primarily taken from the ancient epic Mahavamsa (tr. Geiger, 1912), written between the

5th and 6th centuries A.D. This national history includes stories of wars fought between the kings

and invaders from India and stresses the endurance of Theravada Buddhism and of the influences

of Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism. It also includes stories of the Tamil kingdom in Jaffna and

of the colonization of maritime areas by the Portuguese, the Dutch, and colonization of the while

country by the British. And it informs of the heroes of the independence movement and the social,

economic, and political changes since gaining independence in 1948. This history is presented as

an unbroken history, dating from approximately 2500 B.C. to the present.

DR. MANEESHA S. WANASINGHE – PASQUAL 4

But even in such a detailed history as the above, the hegemonic metanarrative is flexible

and open to different interpretations. Firstly, over the centuries, the audience of the epic has

changed from whom the author wrote it for. So have the circumstances. And along with this, the

current understanding of the history of that era has also changed as a result of archeological

findings and through comparison with other source books, both within the island and outside of it.

Now, archeological evidence and inscriptions have allowed for different interpretations of the

original data. Questioning the authenticity of an event or a statement or the action of an ancient

king or of a renowned nation builder by itself will not result in being called a traitor. Rather, in

times of relative peace, history is placed in the sidelines. Yet, in times of conflict, especially in

internal conflicts, history takes the center stage and is automatically accepted. This is especially

true when it is the metanarrative itself that is being targeted by the ‘other’ side. In Sri Lanka, for

example, one Tamil metanarrative (there are a number of them) inform of an independent Tamil

kingdom in the Northern area of the island that existed between the 12th century and the 16th

century. However, Sinhalese metanarrative informs of a Tamil kingdom, which existed under the

tutelage of the Sinhalese kings. For each group, complexities have disappeared and, for the

Sinhalese history tells of a united Sri Lanka while for the Tamils, it informs of a divided country.

Thus, when a conflict emerges, especially if that conflict is between two groups of people

in a de-facto nation, it can result in the development of ‘competing’ metanarratives – between the

original hegemonic metanarrative and that of the former marginalized or ignored narratives of the

minority or the suppressed. And each side may use the same source material to provide different

interpretations or one side may use other material to discredit the legitimacy of the other’s

narrative. This creates competing metanarratives. But what are metanarratives?

DR. MANEESHA S. WANASINGHE – PASQUAL 5

In a literal sense, metanarrative is a ‘holistic story’ or ‘the big story’ that attempts to explain

everything from a specific perspective. In conflict situations, one side does not accept the existence

of other metanarratives, even though some may have a similar origin and a strong link between

them. Such an all-encompassing holistic metanarrative tradition, a highly modernist notion of a

single narrative that explains society or identity in its entirety will not be used in defining

metanarratives in this thesis. This notion of a holistic story counters the claims made in this article,

that there are competing metanarratives as well as micro, personal narratives. The research

indicated that there were two types of competing narratives – between the competing

metanarratives and within each metanarrative, between the metanarrative and the personal

narratives. But the emphasis here is that they compete in that they do not ignore the existence of

the other. The metanarratives of this analysis are not worldviews but conceptual memories of the

people, traditions, cultures, religions and of cause, identity.

It is also possible to compare metanarrative with macro-narratives, which deal more with

the temporal aspect of narrative rather than the vastness of the narrative itself. As Gergen and

Gergen comments, macro-narrative, and micro-narratives indicate the duration of the narrative

(1997: 171). The macro-narrative in one sense is similar to metanarrative in that both focus on the

temporal aspect of narrative. However, the definition of metanarratives cannot be limited the issue

of time. Some metanarratives endure for thousands of years. They are equally salient as the

metanarratives concerning events of three decades. History, as it impacts people, is how

metanarratives differ from macro-narratives. In criticizing modernists, postmodernist Lyotard

introduced a notion of metanarratives, with its complex mini-narratives (Lyotard, 1984). While

agreeing that there are mini-narratives, this analysis postulates that these cannot exist without the

metanarratives. A multitude of mini-narratives do not make a metanarrative in the definition put

DR. MANEESHA S. WANASINGHE – PASQUAL 6

forward by Lyotard. And these mini-narratives, which are not impervious to time, space, or

context, is often suppressed by a larger metanarrative when conflicts emerge. Negating the

existence of metanarrative makes it difficult to present a ‘history’ of a people since a ‘history’ is a

metanarrative and not a compilation of mini-narratives. Another argument against the acceptance

of mini-narratives is the author’s belief that in times of conflict, these mini-narratives are

consumed by the emergence of hegemonic metanarrative. Moreover, it is necessary to take the

essence of ideas – the existence of grand or meta-narrative and the existence of mini-narratives –

and come up with the notion of metanarratives.

The definition of metanarrative is closer in meaning to that of ‘Public Narratives’, which

are “stories we hear everyday in the news media and the stories that we consume in books, films,

plays, soap operas, and so forth [which] (…) have (…) been important engines of major historical

transitions and of reconfiguration of peoples ‘worldviews’.” (Brock, Strange, Green, 2002: 1).

Public narrative could be viewed as collective narrative (Jacobs, 2002: 205 – 228; Brock, Strange,

Green, 2002: 343 – 348) and therefore, could be used instead of the term metanarratives. However,

metanarratives explore the impact of larger narratives – oral histories, chronicles, annals, myths,

religious texts, current texts that argue about the legitimacy of histories – which mold the identity

in times of crisis. Moreover, Public Narratives as a term does not help shed light on the impact of

the narrative on diverse groups or explain how there can be more than one metanarrative.

The word metanarrative, therefore, intends to be a description of a country’s, a nation’s,

or a peoples’ history. The term “meta” is used here to shed light on how history is all-encompassing

in power rather than all-encompassing in view. The term ‘narrative’ is used to portray history as a

story, with plots, actors, and scenarios. It is therefore the history or the story of a large group of

people, accepted by them as fact and is hegemonic by nature. This controlling role of society is

DR. MANEESHA S. WANASINGHE – PASQUAL 7

especially evident in times of conflict. It is therefore similar in meaning to the term ‘collective

memory’ (Zelizer, 2001: 1850). A metanarrative can be defined as a story about a people. The

larger that story, as in a history of a people, which is temporal, vast and often detailed, becomes a

metanarrative. Thus, a metanarrative is a history. A critical factor about this definition of

metanarrative is that the term ‘meta’ is used here to indicates a ‘hegemonic’ narrative which are

non-the-less not fixed. A metanarrative is flux, changing its character overtime as new evidence

emerges, arguments are accepted, the narrative is challenged, or when new enemies or friends

emerge. Therefore, a metanarrative is not fixed. Rather, inherent in its character is its flexible,

ever-changing nature. A metanarrative or a history is not stagnant or static like a block with its

borders opaque. It is more flexible, its borders often obscure and ever changing.

The primary argument in this article so far is that history is a metanarrative and that there

is more than one history within a multi-cultural, multi-ethnic, multi-religious society. A secondary

argument is that history or metanarratives are not static. They change over time as one aspect is

stressed over another, or re-evaluated, or a specific king is idolized and a certain battle is

highlighted. A third argument is that in times of conflict within that society, it is evident that there

is more than one metanarrative within a single social group or a country. These histories can be

part of an oral tradition or be written down; they can be proven through archeological findings and

inscriptions or part of myths and religion; they can speak predominantly of gods or about kings;

and they could have one author or many authors over time. What is obvious about these histories

is that they are numerous. These are the metanarratives that exist in societies. They are the histories

of that people, that society, that group, or that profession. These metanarratives can influence

culture, identity and thought.

DR. MANEESHA S. WANASINGHE – PASQUAL 8

What are Competing Metanarratives

Competing metanarratives are not similar to the replacement of one narrative with another.

Rather, it deals with the acceptance of a new, competing narrative by one segment of the people

who previously accepted the older narrative. Thus, as the Figure 1 below indicate, in times of

conflict, the metanarrative of one group is challenged.

Figure 1: Competing Metanarratives

Original Original

Hegemonic Hegemonic

Metanarrative Metanarrative Agreement New

Before the emergence & Between Competing

Strengthening of the competing Both Metanarrative

Metanarrative

Source: Author

According to McIntyre, it is possible to have multiple histories within a particular setting

(McIntyre, 1997: 244). And this competing metanarrative does not speak of the dichotomy

between traditional history, “where the old featured kings (…) the new takes as its subject the

anonymous masses.” (Himmelfarb, 1997: 20). Indeed, Novitz has attempted to explain the

emergence of counter – narratives by focusing on personal identity. It is, according to Novitz,

when personal identity is “threatened by a particular narrative identity (…) attempts are made to

undermine and replace the projected identity.” (Novitz, 1997: 152 – 153). According to MacIntyre,

“the rival premises are such that we possess no rational way of weighing the claims of one as

DR. MANEESHA S. WANASINGHE – PASQUAL 9

against another. For each premise employs some quite different normative or evaluative concept

from others, so that the claims made upon us are quite different.” (MacIntyre, 1984: 8). Yet, are

each of these competing metanarratives logically valid by itself or do they exist in relation to each

other, as almost mirror images of other? What this entails is to assume that the new hegemonic

metanarrative exists because of the limitations in the old hegemonic metanarrative. So, if “one

premise against another becomes a matter of pure assertion and counter-assertion” (MacIntyre,

1984: 8), each attempts to deny, explain, fill the gaps of the other hegemonic metanarrative.

It is perhaps possible to imagine that “the community exist by virtue of a story (Carr, 1997:

20). Then a group or a community must protect its own story or narrative from external and internal

conflict that can lead to fragmentation or destruction of that particular story

Personal Narratives

Personal narratives could be called life-narratives, which are “[s]tories about ourselves, in

which we figure as central subject (…) invite the sort of empathy we most desire.” (Novitz, 1997:

148). Yet this term ‘personal narrative’ is not synonymous with narratives of persons of

importance.

The fact that life-narratives [or personal narratives] then to guide and regulate our behavior

is of the greatest social significance (…) The notion of narrative-identity also helps explain

why people are often immune to reason and rational argument (…) or whatever else our

narrative identity does, it helps determine what we consider to be important (…) To accuse

[metanarrative] (…) is to attack their individual identity.” (Novitz, 1997: 151 – 152).

However, it is important to remember that “Narrative construction can never be entirely a private

matter. (…) [Its] an implicit social act.” (Gergen and Gergen, 1997: 176). It is dependent on the

current social evaluation, and “as narratives are realized in the public arena, they become subject

to social molding” (Gergen and Gergen, 1997: 176).

DR. MANEESHA S. WANASINGHE – PASQUAL 10

Narratives help us develop “a unified individual identity … [not that] we all enjoy such an

identity (…) narrative is integrally involved in our search for a coherent self – image (…) The

demand for such coherence seems (…) to be historically and culturally specific and is by no means

a feature of all societies.” (Novitz, 1997: 148). The competing metanarratives are found not only

in the public arena. The interactions between the metanarratives are played out in the private or

personal narrative arena as well. Moreover, “[t]he incidents woven into a narrative are not only the

actions of the single individual but interactions with others.” (Gergen and Gergen, 1997: 177).

It is important to understand that “[w]e are still a long way from identifying all the forms

of everyday discourse that connect the mind to the social world.” (Bennett, 1997: 75).

Because social movements are posited to create social identities by integrating personal

and collective narratives, there is an enormous challenge to the framers of the collective

narratives. (…) importance of narrative structure in meeting this challenge. The mobilizing

narrative must offer plot and character modules that can encompass the conflicting and/or

inconsistent personal identities of targeted adherents; these conflicts and inconsistencies

must be suppressed and replaced with a we-they feeling against nonadherents. Moreover,

a common past must be constructed as well as a set of heroes from the dominant group

within the movement. Finally, Jacobs’ (article 9, this volume) most interesting structural

proposal is that, in building collective identities, it is the genre of the mobilizing narrative

that makes most of the difference [i.e. comedy, tragedy, irony, and romance]. (Brock,

Strange, Green, 2002: 349)

Is it possible then for an individual to be his or her own subject? Connected to this is the question

of whether individuals are participants or agents or is it both or just passive recipients of the

narrative? Or is there a division of labor where some have the authority to tell the narrative while

others are the audience? [Carr, 1997]. It is better to describe this relationship as between the subject

of the narrative or the author of the narrative (Kerby, 1997: 125 - 142). In fact, adapting the notion

presented by McIntyre, the individuals “as not only an actor, but as an author (…) co-author our

own narratives (...) [But] We enter upon a stage which we did not design and we find ourselves

part of an action that was not of our making (…) exerts constraints…….” (McIntyre, 1997: 251).

DR. MANEESHA S. WANASINGHE – PASQUAL 11

Personal narratives could be termed memory and experiences. However, while experience

is important, “[w]ithout memory, (…) experience would have no coherence at all” (Crites, 1997:

20). Memory usually helps create a sequence of events, with an antecedent and an end to the story.

Memory could even be viewed as episodes in a film. Due to time, experience and new knowledge,

old stories may be told differently, “Yet the sophisticated new story … would be superimposed on

the … original … not replace the original without obliterating the very materials …” (Crites, 1997:

37). There is ‘truth’ in the personal narratives told by individuals. These ‘truths’ could be termed

primitive truths, which times help build on.

Conclusion

When conflicts emerge, as is the contention of this research, saw personal narratives that

presents a more complex view of the ‘other’ become unacceptable to society. Indeed, as du Toit

explains, when politicians’ claims are being made in the name of ethnic identity, then personal

identity is often subsumed (du Toit 2004). Yet it is not possible to state emphatically that all

personal narratives that run counter to the status-quo metanarrative die down. The articles that

follow attempt explain how such personal narratives continue to exist while at the same time

accepting the status-quo conflict metanarrative.

DR. MANEESHA S. WANASINGHE – PASQUAL 12

References

Bennett, W. Lance. 1997. “Storytelling in Criminal Trials: a model of social judgement” in

Lewis P. Hinchman, and Sandra K. Hinchman, eds. Memory, Identity, Community: The

Idea of Narrative in the Human Sciences. New York: State University of New York

Press.

Brock, Timothy C., Melanie C. Green, and Jeffery J. Strange. 2002. “Power beyond reckoning:

an introduction to narrative impact.” in Melanie C. Green, Timothy C. Brock, and Jeffery

J. Strange, eds. Narrative Impact: social and cognitive foundations. New York:

Psychology Press.

Brock, Timothy C., Melanie C. Green, and Jeffery J. Strange. 2002. “Insights and Research

Implications: epilogue to narrative impact” in Melanie C. Green, Timothy C. Brock, and

Jeffery J. Strange, eds. Narrative Impact: social and cognitive foundations. New York:

Psychology Press.

Carr, David. 1997. “Narrative and the Real World: an argument for continuity” in Lewis P.

Hinchman, and Sandra K. Hinchman, eds. Memory, Identity, Community: The Idea of

Narrative in the Human Sciences. New York: State University of New York Press.

Crites, Stephen. 1997. “The Narrative Quality of Experience” in Lewis P. Hinchman, and Sandra

K. Hinchman, eds. Memory, Identity, Community: The Idea of Narrative in the Human

Sciences. New York: State University of New York Press.

Du Toit, Andre. 2004. “Founding and Crushing: narrative understandings of political violence in

pre-modern and colonial South Africa” in Journal of Natal and Zulu History. Volume 22.

Geiger, Wilhelm, tr. 1912. The Mahawamsa or te Great Chronicle of Ceylon. Oxford: OUP.

Gergen, Kenneth J. and Mary M. Gergen. 1997. “Narratives of the Self” in Lewis P. Hinchman,

and Sandra K. Hinchman, eds. Memory, Identity, Community: The Idea of Narrative in

the Human Sciences. New York: State University of New York Press.

Himmelfarb, Gertrude. 1997. “History with the Politics Left Out” in Lewis P. Hinchman, and

Sandra K. Hinchman, eds. Memory, Identity, Community: The Idea of Narrative in the

Human Sciences. New York: State University of New York Press.

Hinchman, Lewis P. and Sandra K. Hinchman 1997. “Part III: Community” in Lewis P.

Hinchman, and Sandra K. Hinchman, eds. Memory, Identity, Community: The Idea of

Narrative in the Human Sciences. New York: State University of New York Press.

Hinchman, Lewis P. and Sandra K. Hinchman, eds. 1997. Memory, Identity, Community: The

Idea of Narrative in the Human Sciences. New York: State University of New York

Press. ‘

DR. MANEESHA S. WANASINGHE – PASQUAL 13

Jacobs, Ronald N. 2002. “The Narrative Integration of Personal and Collective Identity in Social

Movements” in Melanie C. Green, Timothy C. Brock, and Jeffery J. Strange, eds.

Narrative Impact: social and cognitive foundations. New York: Psychology Press.

Kerby, Anthony Paul. 1997. “The Language of Self” in Lewis P. Hinchman, and Sandra K.

Hinchman, eds. Memory, Identity, Community: The Idea of Narrative in the Human

Sciences. New York: State University of New York Press.

Lyotard, Jean-Francois. 1982. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge

Translation from the French by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

MacIntyre, Alasdair. 1984. After Virtue: a study in moral theory. 3rd edition. South Bend:

University of Notre Dame.

MacIntyre, Alasdair. 1997. “The Virtues, the Unity of a Human Life, and the Concept of a

Tradition” in Lewis P. Hinchman, and Sandra K. Hinchman, eds. Memory, Identity,

Community: The Idea of Narrative in the Human Sciences. New York: State University

of New York Press.

Novitz, David. 1997. “Art, Narrative, and Human Nature” in Lewis P. Hinchman, and Sandra K.

Hinchman, eds. Memory, Identity, Community: The Idea of Narrative in the Human

Sciences. New York: State University of New York Press.

Thambiah, Stanley Jayaraja. 1992. Buddhism Betrayed?: religion, politics, and violence in Sri

Lanka. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

van Peer, Willie and Seymour Chatman, eds. 2001. New Perspectives on Narrative Perspectives.

New York: SUNY.

Wanasinghe – Pasqual, Maneesha S. 2002. “Speaking to Heart: Educating for peace in Sri

Lanka” Unpublished Master’s Thesis. University of Notre Dame, USA.

Zelizer, Barbie, ed. 2009. Visual Culture and the Holocaust. New Delhi: A&C Black.

DR. MANEESHA S. WANASINGHE – PASQUAL 14

View publication stats

You might also like

- HOL Holler CoreDocument260 pagesHOL Holler CoreHyperLanceite X100% (7)

- Year 11 English Advanced Module A: Narratives That Shape Our WorldDocument12 pagesYear 11 English Advanced Module A: Narratives That Shape Our WorldYasmine D'SouzaNo ratings yet

- (Key Ideas) Pavla Miller - Patriarchy-Routledge (2017)Document169 pages(Key Ideas) Pavla Miller - Patriarchy-Routledge (2017)Sergio Rodrigues RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Breaking Boundaries: Varieties of LiminalityFrom EverandBreaking Boundaries: Varieties of LiminalityAgnes HorvathNo ratings yet

- Queering Anarchism: Addressing and Undressing Power and DesireFrom EverandQueering Anarchism: Addressing and Undressing Power and DesireRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (7)

- The Secret History of Gender: Women, Men, and Power in Late Colonial MexicoFrom EverandThe Secret History of Gender: Women, Men, and Power in Late Colonial MexicoNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Types of Qualitative ResearchDocument5 pagesModule 1 Types of Qualitative ResearchMc Jansen Cadag0% (1)

- In Hands of TalibanDocument8 pagesIn Hands of TalibanAshraf Gondal100% (1)

- Ashta Karma - Eight Magical ActsDocument4 pagesAshta Karma - Eight Magical ActsGeetha Anand100% (5)

- Narrating Truths of Turmoil: 'Metanarratives' From A Con Ict Analysis PerspectiveDocument15 pagesNarrating Truths of Turmoil: 'Metanarratives' From A Con Ict Analysis PerspectiveDesi NoobsNo ratings yet

- Sav Soc Problemi - Prezentacija Literatura 1Document12 pagesSav Soc Problemi - Prezentacija Literatura 1Dara DjordjevicNo ratings yet

- Weber 2007merits and Motivations of An Ashéninka LeaderDocument26 pagesWeber 2007merits and Motivations of An Ashéninka LeaderJuanaNo ratings yet

- Eastmond 2007Document17 pagesEastmond 2007Alexander R.No ratings yet

- Research in Story Form: A Narrative Account of How One Person Made A Difference Against All OddsDocument29 pagesResearch in Story Form: A Narrative Account of How One Person Made A Difference Against All OddsElizabeth Manley DelacruzNo ratings yet

- Legends of People, Myths of State: Violence, Intolerance, and Political Culture in Sri Lanka and AustraliaFrom EverandLegends of People, Myths of State: Violence, Intolerance, and Political Culture in Sri Lanka and AustraliaNo ratings yet

- Kiik, Laur. 2016. Conspiracy, God's Plan, and National Emergency. Kachin Popular Analyses of The Ceasefire Era and Its Resource GrabsDocument31 pagesKiik, Laur. 2016. Conspiracy, God's Plan, and National Emergency. Kachin Popular Analyses of The Ceasefire Era and Its Resource GrabsMariaNo ratings yet

- Reading 1 (GE 2)Document6 pagesReading 1 (GE 2)JEIAH SHRYLE SAPIONo ratings yet

- Bacchilega NarrativeCulturesSituated 2015Document21 pagesBacchilega NarrativeCulturesSituated 2015Akvilė NaudžiūnienėNo ratings yet

- Journal Politic HistoryDocument2 pagesJournal Politic HistoryJennifer YongNo ratings yet

- Readings in Philippine History Assignment No. 1Document5 pagesReadings in Philippine History Assignment No. 1dolim.aizenNo ratings yet

- GE2 Lesson Proper For Week 1 To 5Document35 pagesGE2 Lesson Proper For Week 1 To 5Alejandro Francisco Jr.No ratings yet

- The Anthropology of Violence: Context, Consequences, Con Ict Resolution, Healing, and Peace-Building in Central and Southern AfricaDocument12 pagesThe Anthropology of Violence: Context, Consequences, Con Ict Resolution, Healing, and Peace-Building in Central and Southern AfricaAlexandra SCNo ratings yet

- Dont Get Job Blackman PDFDocument28 pagesDont Get Job Blackman PDFEl MarcelokoNo ratings yet

- Surviving State Terror: Women's Testimonies of Repression and Resistance in ArgentinaFrom EverandSurviving State Terror: Women's Testimonies of Repression and Resistance in ArgentinaNo ratings yet

- 088 Crousel B. TagayloDocument12 pages088 Crousel B. TagayloAnuarMustaphaNo ratings yet

- My Used Copy of Historical Trauma - Crawford-2014Document31 pagesMy Used Copy of Historical Trauma - Crawford-2014tmbsaydaNo ratings yet

- Fasulo Life Narratives in AddictionDocument17 pagesFasulo Life Narratives in AddictionalefaNo ratings yet

- Perspectives: Redemption, Economics, Law, Justice, Mediation, Human Rights: Redemption, Economics, Law, Justice, Mediation, Human RightsFrom EverandPerspectives: Redemption, Economics, Law, Justice, Mediation, Human Rights: Redemption, Economics, Law, Justice, Mediation, Human RightsNo ratings yet

- People Watching EssayDocument6 pagesPeople Watching Essayfz68tmb4100% (2)

- Essay On HomelessnessDocument5 pagesEssay On Homelessnessezkep38r100% (2)

- Aug2018 NavajytoiDocument6 pagesAug2018 NavajytoiPrakrithi GowdaNo ratings yet

- Aporias of HistoryDocument9 pagesAporias of HistoryManoj.N.YNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 5 Ge2Document40 pagesLesson 1 5 Ge2Ella Jordan LoterteNo ratings yet

- Property and Social Relations in Melanesian Anthropology (J. Carrier)Document21 pagesProperty and Social Relations in Melanesian Anthropology (J. Carrier)Eduardo Soares NunesNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Ethnic ConflictDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Ethnic Conflicteryhlxwgf100% (1)

- Minority Histories, Subaltern PastsDocument7 pagesMinority Histories, Subaltern PastsShreyan MishraNo ratings yet

- KAPLAN, Caren. Deterritorializations, 1987Document13 pagesKAPLAN, Caren. Deterritorializations, 1987Vit Santos100% (1)

- WK 1 GE2 Readings in Philippine HistoryDocument8 pagesWK 1 GE2 Readings in Philippine HistoryDIANNA ROSE LAXAMANANo ratings yet

- Thesis WritingDocument40 pagesThesis WritingPau Jane Ortega Consul100% (2)

- Romantic narratives in international politics: Pirates, rebels and mercenariesFrom EverandRomantic narratives in international politics: Pirates, rebels and mercenariesNo ratings yet

- Readings in Phillippine History: General Education 2Document11 pagesReadings in Phillippine History: General Education 2Angelie Blanca PansacalaNo ratings yet

- Resistance FolkloreDocument22 pagesResistance FolkloreaalijahabbasNo ratings yet

- Storytelling As A Peacebuilding MethodDocument8 pagesStorytelling As A Peacebuilding MethodAlexandre GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- READINGS IN PHILLIPPINE HISTORY Topic 1Document7 pagesREADINGS IN PHILLIPPINE HISTORY Topic 1Angel Joy LunetaNo ratings yet

- On Race and Voice Challenges For Liberal Education in The 1990sDocument31 pagesOn Race and Voice Challenges For Liberal Education in The 1990sdiogopacherNo ratings yet

- 1422.full JSCOTT - Preguntas Sin RespuestaDocument9 pages1422.full JSCOTT - Preguntas Sin Respuestaclaudia_bacciNo ratings yet

- The Sublime of the Political: Narrative and Autoethnography as TheoryFrom EverandThe Sublime of the Political: Narrative and Autoethnography as TheoryNo ratings yet

- The Noisy Silence of Gukurahundi Truth Recognition and BelongingDocument24 pagesThe Noisy Silence of Gukurahundi Truth Recognition and BelongingPetronella MushanduNo ratings yet

- Literature and Cultural Production: AllegedlyDocument16 pagesLiterature and Cultural Production: AllegedlyDavidNo ratings yet

- Ruth BeharDocument37 pagesRuth BeharDaniel Bitter100% (2)

- Magnus Course - Birth of The WordDocument26 pagesMagnus Course - Birth of The WordJoaquinCastroNo ratings yet

- Islam and The West Narratives of Conflict and Conflict TransformationDocument29 pagesIslam and The West Narratives of Conflict and Conflict TransformationKhaled Aryan ArmanNo ratings yet

- The Value of Comparison by Peter Van Der VeerDocument34 pagesThe Value of Comparison by Peter Van Der VeerDuke University Press100% (2)

- Spirit Mediumship in Brazil: The Controversy About Semi-Conscious MediumsDocument17 pagesSpirit Mediumship in Brazil: The Controversy About Semi-Conscious MediumsamensetNo ratings yet

- Remembering Intergroup Con Ict: January 2012Document14 pagesRemembering Intergroup Con Ict: January 2012Trần NhiNo ratings yet

- Das - Specificities - Official Narratives, Rumour, and The Social Production of HateDocument23 pagesDas - Specificities - Official Narratives, Rumour, and The Social Production of HateDasheiwoeiowu F Kfgdf100% (2)

- Secondary Research: The Pervasiveness of Stories and Narratives in Organization LifeDocument4 pagesSecondary Research: The Pervasiveness of Stories and Narratives in Organization LifeSuyash JainNo ratings yet

- Lesson Proper For Week 1: Historiography and Its ImportanceDocument22 pagesLesson Proper For Week 1: Historiography and Its ImportanceFrahncine CatanghalNo ratings yet

- HM PRE Draft-Ali Abbas SoniDocument4 pagesHM PRE Draft-Ali Abbas SoniAli Abbas SoniNo ratings yet

- Interview Bellamy July 2018 WD 97 FINAL On WEBSITE ITALICSDocument15 pagesInterview Bellamy July 2018 WD 97 FINAL On WEBSITE ITALICSshaheenfakeNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Philippine HistoryDocument6 pagesLesson Plan Philippine HistoryEverything Under the sunNo ratings yet

- Coates 2018Document6 pagesCoates 2018blazNo ratings yet

- The Role of Narrative Fiction and Semi-Fiction in Organizational StudiesDocument35 pagesThe Role of Narrative Fiction and Semi-Fiction in Organizational StudiesDesi NoobsNo ratings yet

- Master Narratives Beyond Postmodernity: Germany's "Separate Path" in Historiographical-Philosophical LightDocument34 pagesMaster Narratives Beyond Postmodernity: Germany's "Separate Path" in Historiographical-Philosophical LightDesi NoobsNo ratings yet

- ModernTruthandPostmodernIncredulity IJRMDocument14 pagesModernTruthandPostmodernIncredulity IJRMDesi NoobsNo ratings yet

- Narrating Truths of Turmoil: 'Metanarratives' From A Con Ict Analysis PerspectiveDocument15 pagesNarrating Truths of Turmoil: 'Metanarratives' From A Con Ict Analysis PerspectiveDesi NoobsNo ratings yet

- The Philippines A Century HenceDocument13 pagesThe Philippines A Century HenceGravy SiyaNo ratings yet

- Thought of Ibn Taymiyyah PDFDocument313 pagesThought of Ibn Taymiyyah PDFAli Asghar Shah100% (1)

- Dwnload Full Leading and Managing in Nursing 6th Edition Wise Test Bank PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Leading and Managing in Nursing 6th Edition Wise Test Bank PDFgallivatmetholhvwz0100% (9)

- Artifact01 3a Colloquium Program Sheet 2015Document12 pagesArtifact01 3a Colloquium Program Sheet 2015api-433599213No ratings yet

- About KaruneegarDocument17 pagesAbout KaruneegarBhaskar Karanam0% (2)

- AnushamDocument10 pagesAnushamhari.haran.mk6476No ratings yet

- Pastors Reference LetterDocument1 pagePastors Reference Letteroluwadamilareadeboye08No ratings yet

- Module 11 NORTH AMERICA No Activities Global Culture and Tourism Geography 11Document10 pagesModule 11 NORTH AMERICA No Activities Global Culture and Tourism Geography 11Mary Jane PelaezNo ratings yet

- Caed324 (Narrativereport)Document7 pagesCaed324 (Narrativereport)Kathreen MakilingNo ratings yet

- Advanced Rune EP 6.0 - Skill RuneDocument43 pagesAdvanced Rune EP 6.0 - Skill RuneMarcelo DinizNo ratings yet

- Srisailam & Ahobilam & Alampur Tourist Places1Document4 pagesSrisailam & Ahobilam & Alampur Tourist Places1phani raja kumarNo ratings yet

- The Scarlet Letter Literary AnalysisDocument4 pagesThe Scarlet Letter Literary AnalysisErica100% (2)

- Jeffery H B Three TreatmentsDocument14 pagesJeffery H B Three TreatmentsLeslie BonnerNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Economics Today The Micro View 18th Edition Miller Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument33 pagesInstant Download Economics Today The Micro View 18th Edition Miller Test Bank PDF Full ChapterCharlesChambersqtsp100% (11)

- THE TEACHINGS OF THE BUDDHA RewisedDocument33 pagesTHE TEACHINGS OF THE BUDDHA RewisedBeniram KocheNo ratings yet

- Gay Wilson Allen-Walt Whitman Handbook (LITERATURE, LITERARY HISTORY, REFERENCE) - Packard and Company (1946)Document340 pagesGay Wilson Allen-Walt Whitman Handbook (LITERATURE, LITERARY HISTORY, REFERENCE) - Packard and Company (1946)Zoobia AbbasNo ratings yet

- Biblical Figures and Traditional PersonificationsDocument3 pagesBiblical Figures and Traditional PersonificationsEricka RedoñaNo ratings yet

- Ziarat HzabbasDocument7 pagesZiarat HzabbasMaham QureshiNo ratings yet

- Inner Work Kundalini AwakeningDocument5 pagesInner Work Kundalini AwakeningThe Melanated Messenger100% (2)

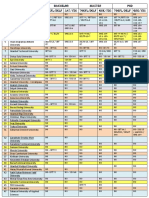

- NO University Name Bachelor Master PHD Toefl/Delf Sat/Yds Toefl/Delf Gre/Yds Toefl/Delf Gre/YdsDocument15 pagesNO University Name Bachelor Master PHD Toefl/Delf Sat/Yds Toefl/Delf Gre/Yds Toefl/Delf Gre/YdsU ConceptsNo ratings yet

- GED117 Quiz 3Document1 pageGED117 Quiz 3jhudielle imutan (jdimutan)No ratings yet

- University of Hawai'i Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Philosophy East and WestDocument21 pagesUniversity of Hawai'i Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Philosophy East and WestNishant YadavNo ratings yet

- Dark Souls 2 AlvaDocument3 pagesDark Souls 2 AlvaRafael BalbiNo ratings yet

- A Look Into Kendra Dhipati DoshaDocument10 pagesA Look Into Kendra Dhipati Doshadavis mathewNo ratings yet

- XMNNov 2021Document12 pagesXMNNov 2021Xaverian Missionaries USANo ratings yet

- Sponsored by The Benjamin and Anna E. Wiesman Family Endowment FundDocument28 pagesSponsored by The Benjamin and Anna E. Wiesman Family Endowment Fundutamar319No ratings yet

- UH PJOK Kelas 8 (Jawaban)Document48 pagesUH PJOK Kelas 8 (Jawaban)Thoriq FirdausNo ratings yet