Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Solving A2J Problem-Replace Cottage Industry Production Legal Services With Support Services Production

Solving A2J Problem-Replace Cottage Industry Production Legal Services With Support Services Production

Uploaded by

Eve AthanasekouCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Challenges in Introducing Adr System in IndiaDocument23 pagesChallenges in Introducing Adr System in Indiaakshansh1090% (10)

- AB V Tapton School Academy Trust Approved JudgmentDocument15 pagesAB V Tapton School Academy Trust Approved JudgmentTim BrownNo ratings yet

- AI For Lawyers: How Artificial Intelligence is Adding Value, Amplifying Expertise, and Transforming CareersFrom EverandAI For Lawyers: How Artificial Intelligence is Adding Value, Amplifying Expertise, and Transforming CareersNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethics ProjectDocument24 pagesProfessional Ethics ProjectManashwi Sahay29% (7)

- Contemporary Canadian Business Law 10th Canadian Edition EbookDocument755 pagesContemporary Canadian Business Law 10th Canadian Edition Ebookohgoody89% (9)

- Reinventing The Agmut and Danics Cadre - A Civil Service For Indian Union Territories.Document34 pagesReinventing The Agmut and Danics Cadre - A Civil Service For Indian Union Territories.rpmeena_12No ratings yet

- Fture LawyerDocument6 pagesFture LawyerPatrick ChanNo ratings yet

- Legal Week 2019 FINALDocument2 pagesLegal Week 2019 FINALshankarjmc7407No ratings yet

- Professional Ethics ProjectDocument24 pagesProfessional Ethics ProjectGhanashyam100% (3)

- Tecnologia para Empresas LawDocument20 pagesTecnologia para Empresas LawMuriel JaramilloNo ratings yet

- The State of Legaltech in Africa Report 1Document22 pagesThe State of Legaltech in Africa Report 1Mobolaji AdebayoNo ratings yet

- Module 3b AI ImpactDocument49 pagesModule 3b AI Impactsehar Ishrat SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- The End of Lawyers? Rethinking The Nature of Legal ServicesDocument14 pagesThe End of Lawyers? Rethinking The Nature of Legal ServicesDusan PavlovicNo ratings yet

- The Most Recommended Law Firms To Watch in 2021Document40 pagesThe Most Recommended Law Firms To Watch in 2021The Business FameNo ratings yet

- Global N Profession KunwarDocument17 pagesGlobal N Profession KunwarBhan WatiNo ratings yet

- Elaine - Individual AssignmentDocument6 pagesElaine - Individual AssignmentElaine van SteenbergenNo ratings yet

- Global N Profession - KunwarDocument17 pagesGlobal N Profession - Kunwarparish mishraNo ratings yet

- ADR ProjectDocument15 pagesADR ProjectshivamNo ratings yet

- Problems With The Advocates (Amendment) Bill, 2017: Pallavi MohpalDocument3 pagesProblems With The Advocates (Amendment) Bill, 2017: Pallavi MohpalsolomonNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethics Project: Amity University, NoidaDocument24 pagesProfessional Ethics Project: Amity University, NoidaEbadur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Legal Aid Project - Alternative Dispute Resolution Semes 6 - ManishaDocument19 pagesLegal Aid Project - Alternative Dispute Resolution Semes 6 - ManishaManisha VermaNo ratings yet

- Consumer Perceptions of Online Legal Service ProvidersDocument29 pagesConsumer Perceptions of Online Legal Service Providers8sw9kq4htpNo ratings yet

- CLAT 2025 Legal Current Affairs May MonthDocument13 pagesCLAT 2025 Legal Current Affairs May Monthroyalrajiit1108No ratings yet

- LJG 3Document14 pagesLJG 3itskevingautamNo ratings yet

- Escoin WhitePaper v1 6 PDFDocument30 pagesEscoin WhitePaper v1 6 PDFFernando Zacarias CauNo ratings yet

- Recent Developments in The Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)Document5 pagesRecent Developments in The Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)aashishgupNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethics Project RichDocument21 pagesProfessional Ethics Project RichAbhijeet Talwar0% (1)

- Future of The Profession EngDocument110 pagesFuture of The Profession EngasdfosadjfNo ratings yet

- YJcF9blYvckhJVcUUOtn7agutHbUyT1TPEka8R4c PDFDocument20 pagesYJcF9blYvckhJVcUUOtn7agutHbUyT1TPEka8R4c PDFrafin71No ratings yet

- Group 1 Final AssignmentDocument5 pagesGroup 1 Final AssignmentCindy CheryaNo ratings yet

- McGinnis, John O - The Great Disruption - How Machine Intelligence Will Transform The Role of Lawyers in The Delivery of Legal ServicesDocument27 pagesMcGinnis, John O - The Great Disruption - How Machine Intelligence Will Transform The Role of Lawyers in The Delivery of Legal ServicesFrancisco AraujoNo ratings yet

- (Faculty For Professional Ethics) : Iability FOR Deficiency IN Service AND Other Wrongs Committed BY LawyersDocument22 pages(Faculty For Professional Ethics) : Iability FOR Deficiency IN Service AND Other Wrongs Committed BY LawyersMukesh TomarNo ratings yet

- Amity University, Uttar Pradesh: Submitted To: Submitted byDocument14 pagesAmity University, Uttar Pradesh: Submitted To: Submitted byManas AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Can Lawyers Stay in The Driver's Seat - Currell & Henderson - SSRN-Id2201800Document46 pagesCan Lawyers Stay in The Driver's Seat - Currell & Henderson - SSRN-Id2201800BillLudley5No ratings yet

- Applying Business Sense in The Legal Market-1Document17 pagesApplying Business Sense in The Legal Market-1Thanh ThưNo ratings yet

- How Technology Is Changing The Practice of LawDocument6 pagesHow Technology Is Changing The Practice of LawJacq LinNo ratings yet

- The Provision of Legal ServicesDocument2 pagesThe Provision of Legal Servicesjosh_stylianouNo ratings yet

- Niharika Khanna 18010324093Document5 pagesNiharika Khanna 18010324093Niharika khannaNo ratings yet

- Proposal LLB, 102,19Document24 pagesProposal LLB, 102,19Sheldon AtambaNo ratings yet

- A Project Report Submitted To: Ms. Priyanka Ghai Subject: Professional EthicsDocument20 pagesA Project Report Submitted To: Ms. Priyanka Ghai Subject: Professional EthicsAnirudh VermaNo ratings yet

- N L U O: Ational AW Niversity DishaDocument15 pagesN L U O: Ational AW Niversity DishaHitarth SharmaNo ratings yet

- Innovation and Technology in Legal ServicesDocument24 pagesInnovation and Technology in Legal ServicesVishal LohareNo ratings yet

- Cyber Law FDDocument14 pagesCyber Law FDShalini DwivediNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Lawtech October 2019Document37 pagesIntroduction To Lawtech October 2019Asma ElmangoushNo ratings yet

- LAW AND ECO FINAL ProjectDocument17 pagesLAW AND ECO FINAL Projectawesum.faizanNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethics Project: Amity University, NoidaDocument25 pagesProfessional Ethics Project: Amity University, NoidaMeghanath PandhikondaNo ratings yet

- Minimizing Pending Cases in Indian Courts Using Artificial Intelligence Techniquespredict The Outcome of Consumer ComplientsDocument15 pagesMinimizing Pending Cases in Indian Courts Using Artificial Intelligence Techniquespredict The Outcome of Consumer ComplientsMadhu MandavaNo ratings yet

- Digital Court Reform Conference: David Gauke SpeechDocument3 pagesDigital Court Reform Conference: David Gauke SpeechMarcoNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3308168Document42 pagesSSRN Id3308168Kiran NadeemNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethics Project O - : Nature of Legal Profession'Document18 pagesProfessional Ethics Project O - : Nature of Legal Profession'Vivek KashyapNo ratings yet

- Commercial Laws ProposalDocument4 pagesCommercial Laws ProposalSHASWAT DROLIANo ratings yet

- Best Practice in Construction AdjudicationDocument1 pageBest Practice in Construction Adjudicationb165No ratings yet

- (Faculty For Professional Ethics) : Iability FOR Deficiency IN Service AND Other Wrongs Committed BY LawyersDocument23 pages(Faculty For Professional Ethics) : Iability FOR Deficiency IN Service AND Other Wrongs Committed BY LawyersMalay PathakNo ratings yet

- Legal Tech StartupsDocument5 pagesLegal Tech StartupsSiva KakulaNo ratings yet

- Eassay Assignment - Law102 - Truongvnhe141641 - IB1504Document9 pagesEassay Assignment - Law102 - Truongvnhe141641 - IB1504Trưởng Vũ NhưNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Legal Tech On Law Firms Business ModelDocument76 pagesThe Impact of Legal Tech On Law Firms Business Model289849849852984721No ratings yet

- Practicing Law Without An Office Address: How The Bona Fide Office Requirement Affects Virtual Law PracticeDocument28 pagesPracticing Law Without An Office Address: How The Bona Fide Office Requirement Affects Virtual Law PracticeStephanie L. KimbroNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Topics Property LawDocument6 pagesDissertation Topics Property LawScientificPaperWritingServicesUK100% (1)

- LAZ PAPER Ethics Ethical Conduct Challenges and Opportunities in Modern PracticeDocument15 pagesLAZ PAPER Ethics Ethical Conduct Challenges and Opportunities in Modern PracticenkwetoNo ratings yet

- PLE0042 Reading Project T3 2021Document4 pagesPLE0042 Reading Project T3 2021Sareen BharNo ratings yet

- Principles of Public Administration 2023Document44 pagesPrinciples of Public Administration 2023Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4001899Document9 pagesSSRN Id4001899Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3958442Document63 pagesSSRN Id3958442Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3938810Document9 pagesSSRN Id3938810Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3938734Document8 pagesSSRN Id3938734Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4005612Document35 pagesSSRN Id4005612Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4269121Document66 pagesSSRN Id4269121Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- ACTA The Ethical Analysis of A FailureDocument14 pagesACTA The Ethical Analysis of A FailureEve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4281275Document50 pagesSSRN Id4281275Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- The Early Jesus Prayer and MeditationDocument38 pagesThe Early Jesus Prayer and MeditationEve Athanasekou100% (1)

- Religious Travel and Pilgrimage in MesopotamiaDocument24 pagesReligious Travel and Pilgrimage in MesopotamiaEve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3997378Document46 pagesSSRN Id3997378Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4220270Document67 pagesSSRN Id4220270Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- Luxury and Wealth in Sparta and The PeloponeseDocument19 pagesLuxury and Wealth in Sparta and The PeloponeseEve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4256518Document37 pagesSSRN Id4256518Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4196062Document28 pagesSSRN Id4196062Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4279162Document37 pagesSSRN Id4279162Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- The West Hurrian Pantheon and Its BackgroundDocument27 pagesThe West Hurrian Pantheon and Its BackgroundEve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4249282Document20 pagesSSRN Id4249282Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- Wisdom of Former Days - The Manly HittiteDocument29 pagesWisdom of Former Days - The Manly HittiteEve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4253256Document23 pagesSSRN Id4253256Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4190073Document12 pagesSSRN Id4190073Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4181471Document19 pagesSSRN Id4181471Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3925085Document18 pagesSSRN Id3925085Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4180729Document41 pagesSSRN Id4180729Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4185120Document5 pagesSSRN Id4185120Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3942151Document58 pagesSSRN Id3942151Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4223391Document21 pagesSSRN Id4223391Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- Divinus Plato Is Plato A Religious Figure?Document15 pagesDivinus Plato Is Plato A Religious Figure?Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4225805Document10 pagesSSRN Id4225805Eve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For EWS Certificate Issued by BCW DepttDocument14 pagesGuidelines For EWS Certificate Issued by BCW DepttWrickNo ratings yet

- DAO No 5 s2007Document5 pagesDAO No 5 s2007Hazel HormillosaNo ratings yet

- Sample Performance Bond Claim LetterDocument7 pagesSample Performance Bond Claim LetterNur Fateen NabilahNo ratings yet

- (Nutshell Series) Louis Sohn, Kristen Juras, John Noyes, Erik Franckx - The Law of The Sea in A Nutshell-West Academic (2010)Document469 pages(Nutshell Series) Louis Sohn, Kristen Juras, John Noyes, Erik Franckx - The Law of The Sea in A Nutshell-West Academic (2010)Mehedi Hasan SarkerNo ratings yet

- Tesla Solar Roof SettlementDocument5 pagesTesla Solar Roof SettlementSimon AlvarezNo ratings yet

- 2nd Sem Previous Yr. Question Papers (5 Subjects)Document44 pages2nd Sem Previous Yr. Question Papers (5 Subjects)Muhammed Muktar0% (1)

- Emma MSC Dissertation Corrected-1Document88 pagesEmma MSC Dissertation Corrected-1Ma'aku Bitrus AdiNo ratings yet

- The Implementation of Uti PossidetisDocument14 pagesThe Implementation of Uti PossidetisAsz OneNo ratings yet

- SOCIAL STUDIES GC 4Document11 pagesSOCIAL STUDIES GC 4Lanz CuaresmaNo ratings yet

- The Subjective Objective Theory of Contract Interpretation and GoogleDocument4 pagesThe Subjective Objective Theory of Contract Interpretation and GoogleshiviNo ratings yet

- NTP 1994Document15 pagesNTP 1994Harshit ChopraNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Acsms Nutrition For Exercise Science First Edition Ebook PDF PDF FREEDocument32 pagesInstant Download Acsms Nutrition For Exercise Science First Edition Ebook PDF PDF FREEamy.rodgers967No ratings yet

- Marcus Aurelius BiographyDocument3 pagesMarcus Aurelius BiographyFiras ZahmoulNo ratings yet

- Craap TestDocument7 pagesCraap Testapi-611923181No ratings yet

- PEOPLE Vs JOSEPH ESTRADA - ASTIDocument1 pagePEOPLE Vs JOSEPH ESTRADA - ASTIRamon Khalil Erum IVNo ratings yet

- Church of Ambrosia and Zide Door vs. City of Oakland, Oakland Police Department, and John RomeroDocument62 pagesChurch of Ambrosia and Zide Door vs. City of Oakland, Oakland Police Department, and John RomeroNoor Al-SibaiNo ratings yet

- Pogrome in Rußland 1903-1905 - 6Document39 pagesPogrome in Rußland 1903-1905 - 6Ab SamuelNo ratings yet

- MonthlyDocument2 pagesMonthlyLemuel JanerolNo ratings yet

- Reyes 3a Diplomacy-FinalsDocument10 pagesReyes 3a Diplomacy-FinalsJayson ReyesNo ratings yet

- Raisin in The Sun Essay QuestionsDocument8 pagesRaisin in The Sun Essay Questionsd3gpmvqw100% (2)

- Practical Business Math Procedures 12th Edition Slater Test BankDocument35 pagesPractical Business Math Procedures 12th Edition Slater Test Bankhollypyroxyle8n9oz100% (33)

- CFLM 200Document32 pagesCFLM 200Tabaosares JeffreNo ratings yet

- 3 - Etchemendy Lodola - 2023 NGLESDocument73 pages3 - Etchemendy Lodola - 2023 NGLESJulieta SimariNo ratings yet

- Yash Paul Nargotra, J.: Equiv Alent Citation: 2007 (3) JKJ202Document8 pagesYash Paul Nargotra, J.: Equiv Alent Citation: 2007 (3) JKJ202Sanil ThomasNo ratings yet

- Examiners' Report 2012: LA1031 Common Law Reasoning and Institutions - Zone ADocument10 pagesExaminers' Report 2012: LA1031 Common Law Reasoning and Institutions - Zone AJUNAID FAIZANNo ratings yet

- INGAN ThesisPPTDocument18 pagesINGAN ThesisPPTCorie Emmanuel TilosNo ratings yet

- جريمة التعدي على الملكية العقارية الخاصةDocument20 pagesجريمة التعدي على الملكية العقارية الخاصةKhaledSoufianeNo ratings yet

- Golden Rule of InterpretationDocument15 pagesGolden Rule of InterpretationvarshiniNo ratings yet

Solving A2J Problem-Replace Cottage Industry Production Legal Services With Support Services Production

Solving A2J Problem-Replace Cottage Industry Production Legal Services With Support Services Production

Uploaded by

Eve AthanasekouOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Solving A2J Problem-Replace Cottage Industry Production Legal Services With Support Services Production

Solving A2J Problem-Replace Cottage Industry Production Legal Services With Support Services Production

Uploaded by

Eve AthanasekouCopyright:

Available Formats

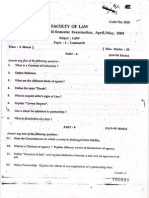

Solving A2J Problem-Replace Cottage Industry Production Legal Services with Support Services

Production

Ken Chasse1

No. Table of Contents Page

1. Introduction to the Access to Justice Problem of Unaffordable Legal Services 1

2. Law Societies Don’t Try to Solve the A2J Problem—It’s Not Theirs to Solve They Say 4

3. Support Services Take Advantage of the “Fixed Costs Factor” and Greater Specialization 6

4. Recommended Improvements Cannot Produce Affordability for Legal Services 8

5. Lawyers Are Giving Up Their Connection with Middle-Income and Lower-Income People 10

6. A Civil Service for Law Societies 15

7. The Application of the Support Services Method to Establish a Legal Services Support Services 16

8. Lawyers’ Technological Competence as to Electronically-Produced Evidence 23

9. Legal Aid Ontario’s 80 Clinics as a Network of Interdependent Support Services 27

10. Paying for a national civil service for law societies 29

11. LAO LAW is Now a Different Kind of Research Service 31

12. The Solution to the A2J Problem Will Not Happen in the Near Future 31

13. The Big Law Firms Will Develop Their Own Support Services Method of Production 34

14. Conclusion 35

1. Introduction to the Access to Justice Problem of Unaffordable Legal Services

The solution to the access to justice problem (the A2J problem) of unaffordable lawyers’ services is to

transition the legal profession from its present very obsolete cottage industry method of production to a support

services method, as has all of the production of all other goods and services for more than 120 years. “Cottage

industry method” means the producer of the finished product makes all parts of it itself.2 The production of

medical services and automobiles are examples of production by way of support services methods, i.e., many

parts of the finished product are made externally by special parts producers that each produce different ones

of the several or many parts of the work and materials necessary to the manufacturing of the finished product.

1

Ken Chasse, J.D., LL.M., member of the Law Societies of Ontario and British Columbia, Canada.

2

The use of the phrase, “cottage industry” in describing the legal profession’s method of producing legal services is

also used by Richard Susskind, a well-established authority on the present and future disruptions to the practice of

law and to lawyers, caused by machine technology (artificial intelligence). His several books emphasize the fact that

solo and small law firms are under considerable threat of soon being replaced (all published by Oxford University

Press (OUP)); see: Online Courts and The Future of Justice (2019); The Future of the Professions (2015), with his

son, Daniel Susskind); Tomorrow’s Lawyers (2013); The End of Lawyers (2008); Transforming the Law (2000); and

the, CBA Legal Futures Initiative’s, A Guide to Strategy for Lawyers, by Richard Susskind (2012, but no longer

available online). See also Wikipedia

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

2

Such comparisons of such very different products are valid because the A2J problem is not one concerning the

contents of various goods and services in comparison with legal services, but rather their different methods of

production. They should be analyzed, each one with the other for their similarities, methods of achieving cost-

efficiency, and thereby, their needed economies-of-scale that affordability requires. Most important of all is,

how to maximize the benefit obtained from the fixed-costs factor, along with the greatest cost-efficiency from

the highest degree of specialization.

And, I discovered in creating and operating a highly specialized, high volume legal research support service,

producing several thousands of legal opinions per year for lawyers in private practice, that my staff of research

lawyers did not get bored doing only legal research to write those legal opinions, and doing it only one major

area of the law. In fact, none of them wanted to switch to another area of law. Instead, they developed ever-

increasing pride in their very extensive knowledge within their field of expertise. That is the desired

combination necessary: the greatest speed of production, along with the greatest safety of production due a

very high degree of specialization. A higher degree of specialization of all major factors of production, beyond

what law firms can themselves afford, is mandatory if such problems as the A2J problem are to be solved. And

because all lawyers produce their legal services in the same very obsolete way, the A2J problem is every

lawyer’s production problem.

Without the use of support services, it is not possible to produce legal services affordably for middle- and

lower-income people. And, when the problem becomes a significant threat to their profits, the big law firms

will themselves gradually move to a support services method of production. But when those same lawyers

serve as law society managers (benchers)3, they will not have enough time free from serving their own clients

to bring about a support-services method for all lawyers, but only within their own law firms, for their own

clients. That is to say, the bencher-building-block of law society management, has become the justice system’s

“bencher-burden” that greatly impairs the justice system’s ability to do justice and ensure the rule of law.

Those lawyers won’t be helping-out the general practitioners, who are the lawyers that serve middle- and

lower-income people. But they could help them, because the bigger is the volume of production, the larger are

the economies-of-scale obtainable, and therefore, the bigger will be the profits made. Therefore, law societies,

working with the big law firms, should establish a much larger support service system that is able to serve all

lawyers and thereby, all of their clients.

For example, without the parts industry that serves the automobile industry, it would not be possible to

produce automobiles affordably for middle-income people. Volume matters! In the first decade of the 20th

3

“Bencher”-Canadian usage: the terms bencher and treasurer are in use by the legal profession in Canada. A

bencher in the Canadian context is a lawyer elected by the other lawyer-members of the law society, for a fixed

term, to be its board of directors (referred to as “Convocation”). The treasurer is elected by the benchers to function

as the chair. Paralegals are also elected as benchers in those provinces where the law societies govern the paralegal

profession.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

3

century, the “horseless carriages” that were the very first automobiles, were affordable only by wealthy people.

But then competition created a desire for larger markets, which forced the creation of the parts industry, which

in turn brought affordability for a much greater market.

Beginning in July 1979, I learned the cause and solution of the A2J problem “the hard way,” by establishing

a high-volume, highly specialized legal research support service for lawyers in private practice. There was no

precedent to follow or how-to-do-it manual to read. Described below are the methods and principles of

production used to achieve a greater cost-efficiency in production than is possible for a law firm to achieve,

because law firms cannot achieve the very high volumes of production that affordability requires. But support

services can. Several support services, each producing different parts of the work to produce legal services

would greatly reduce the costs of producing legal services. Thereby legal services would be rendered more

affordable for more people within all income levels of society, and lawyers would make more money, as has

all of the manufacturing of goods and services by adopting support services methods of production.

But instead, the suggestions made by lawyers and law societies to improve cost-efficiency to lower costs,

accept the traditional law firm as being the only production to be used. But affordability can never be achieved

by embellishing an obsolete method of production. The traditional law firm cannot make the necessary high

volumes of production needed for affordability. Going from cottage industry production to support-services

production is not merely improving the same old method of production. It is a different method and technology

of production.

For a law firm, worries as to the costs and cost-efficiency of producing legal services may begin with clients

saying “no more hourly billing; we want fixed-cost billing.” That transfers the onus and obligation to obtain

greater cost-efficiency to the law firm, which leads to greater interest in cost-efficiency to create greater

economies-of scale. In turn, that leads to law firms beginning to “contract out” parts of their lawyers’ work to

be done by lawyers of lower cost. If done with significant volume and regularity, lawyers working outside of

those law firms will come to depend upon such work which will evolve to become a support services method

of production. Without it, the practise of law will become increasingly financially unviable.

For example, in the U.S., and now beginning in Canada, the general practitioner is disappearing, and the

commercial producers of legal services are taking over their markets. But commercial producers have

customers, while lawyers have clients. If the gap between what lawyers’ services cost and what middle-income

people can afford could be made substantially smaller, then advertising the protections and safeguards provided

by the professional lawyer-client relationship that the buyer-seller relationship does not have, could become

very effective advertising. People know the difference, just as they know the different between their

relationship with their family doctor, and the risks of buying a commercial market. Unless there’s a special

contract between them, the duties between buyer and seller are merely to be honest and be legal, but after that,

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

4

each is free to try to get “the best of the deal.” Doctors and lawyers are much safer than that, if you can afford

them.

But regardless that it is very likely that law societies will remain deeply entrenched within and wedded to

their late 18th century and early 19th century origins, lawyers will not disappear. The big law firms and lawyers

in institutional law departments and lawyers who have highly specialized law practices serving the business

community and wealthy people, working together, will create their own support services method of production.

And they will do so when the consequences of remaining with a “cottage industry method” of production

become sufficiently threatening to their profits. History proves that, “organizations do not change until the fear

of the consequences of not changing, is greater than the fear of the consequences of not changing.” But they

don’t yet show those necessary fears of the consequences of not changing.

Governments are to blame for that. That is because, being political entities, governments live by the alleged

political wisdom that states, “there are not votes in justices,” meaning, that there are no significant quantities

of votes to be gained by spending significant quantities of taxpayers’ money on justice system problems. So

they don’t, with the result that they never hold law societies to account for the way in which they use their

powers and perform their duties. And so, law societies have in fact always lived above the law. The rule of

law does not apply to them in fact. As a result, being the product of the concept of the “gentlemen lawyer,”

which only in the earliest decade of the 20th century gave way to the concept of “the professional,” they still

act as would a private gentlemen’s club (that now includes ladies, of course). That is the mentality that

underlies the A2J problem, i.e., a gentlemen’s club is owned by its members, free to decide what they will do

and why they will do it. In fact, they exist unaccountable to the political-democratic process of rule by the

voting public.

2. Law Societies Don’t Try to Solve the A2J Problem—They Say It’s Not Theirs to Solve

Canada’s law societies—the regulators of its legal profession and therefore the regulators of lawyers’ and

paralegals’ responses to the A2J problem—have been allowed to live comfortably in the second half of that

proposition as to fearing merely the consequences of changing. And so it is that their management structure

has not changed since they were created, more than 220 years ago.4 That structure is the “bencher-building-

bloc of law society management.”5 In contrast, producers in truly competitive commercial markets must live

in the first half, coping with the ever-present, worrying about the consequences of not being able to keep pace

with the changes made to their products and pricing by their competitors. That requires taking chances and

4

To understand the history that has made all of Canada’s law societies as they are, see: Christopher Moore, The Law

Society of Upper Canada and Ontario’s Lawyers 1797-1997 (University of Toronto Press Inc., 1997). “Upper

Canada” was the province of Ontario’s British colonial name until Canada became a country on July 1, 1867.

5

“Bencher”-Canadian usage: supra note 3.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

5

accepting the risks that a new product will fail when brought to market, its long and expensive development

period thereby having been wasted. That is why commercial markets are so very productive in bringing us new

products with new forms of marketing etcetera—their producers are forced to take chances and accept the

uncertainty of success.

In contrast, because they are not effectively and sufficiently challenged by governments, or anyone else,

such as by the general practitioners who are disappearing, law societies’ management concept and structure

has left them no more capable than an early 19th century law society. As a result, the A2J problem exists

because law societies have gone unchallenged when they express their purpose and duty as in the following

very narrow terms:6

The role of the Law Society is not to “deliver access to justice.” That is the responsibility

of the government and the courts. The Law Society is to regulate legal services so as to

facilitate access to justice. This presumably means determining who may provide legal

services and determining the required competence and conduct of licensees with access to

justice being a central consideration.

The result is that law societies will do only that which they have always done, and if that isn’t enough to

produce justice, they say it’s the government’s problem. Decisions as to such necessary changes concerning

the production of legal services are to be left to law firms and not made by law societies.7 As a result, there is

no attempt being made to solve the A2J problem, nor to learn its cause.

Unfortunately, we cannot expect an early 19th century law society management structure to be a competent

21st century law society in a 21st century justice system. And so it is that: (1) no law society has a program the

purpose of which is to solve the A2J problem; and, (2) the general practitioner is disappearing because that

type of law practice is increasingly becoming financially unviable, even though needed more than ever before

by middle- and low-income people. But Canada’s law societies are doing nothing to make their legal services

affordable. The cottage industry method of production makes it so. But our law societies do not see the

obsolescence of the method by which lawyers produce legal services is a problem for them to solve. It is

something that lawyers within their own law firms are responsible for, with the aid of law society

recommendations of course. The end result will be that middle- and lower-income people will not have lawyers

to help them deal with their more serious, difficult, frightening, and potentially life-changing legal problems.

But, the very large, charitable “access to justice industry” relief effort has no presence or solution in regard to

those kinds of legal problems. And neither do law societies, which should not be tolerated. This great failure

6

This was stated as part of the published comment of the Treasurer of the Law Society of Ontario (its chief

executive officer), in response to my blog article, entitled, “Law Society Policy for Access to Justice Failure” (Slaw,

July 25, 2019). See also infra notes 19 and 20, and accompanying text.

7

See infra note 18 and accompanying text.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

6

justifies law societies being substantially reformed to be managed by permanently employed expertise in

addition to lawyers.

3. Support Services Take Advantage of the “Fixed Costs Factor” and Greater Specialization

Support services methods use a series of different external support services to produce various different

parts of the finished product, be it services or hard goods. They can each produce their different parts of a

compete legal service at a far greater volume than any law firm is capable of. Thereby, each achieves far greater

economies-of-scale than any law firm is capable of, and thereby a lower cost of production than any law firm

is capable of—meaning, scaling-up the volume of production to achieve a greater ability to spread costs that

are not increasing in proportion to those increasing volumes. That is what is called, “the fixed costs factor”:

“in the production of anything and everything, not all of the costs of production increase in proportion to the

volume of production.” It becomes progressively less expensive to produce more and more.

For example, if a law firm has 50 lawyers, it doesn’t buy 50 copies of every book for its law library.

Therefore, as the firm produces an ever-increasing volume of legal services, each legal service pays for an

ever-decreasing part of total law library costs because of the increasing ability to spread costs. But because

law library costs are but a very small part of the total costs of a law firm, that is but a small example of the

economic advantage gained by putting as much distance as possible between the volume of production of

finished work-product and the producer’s slowly increasing costs. But it does explain why commercial

producers want to quickly expand from being merely local, to national and then international producers, i.e.,

the greater the volume of production, the greater is the advantage gained from the fixed costs factor. The

producer’s profit-margins steadily increase as volume increases, which means that, that part of one’s price to

the consumer that is profit, steadily increases. And the other part, that pays for costs, steadily decreases.

Volume of production thereby determines the volume of profits. Such unaffordability is due to the constant

rapid increase in the volume of law, its complexity, speed at which it changes, and its increasing dependence

upon technology that has to be understood. In addition, the transition from paper-based to electronic records

has greatly increased the volume, convenience of making and using records, and greatly lowered the cost of

making, storing, and transmitting the records that everyone has to deal with. All of which has greatly increased

the time and therefore the cost of producing legal services and their unaffordability over the last several decades.

At present, it is well established that there are no economies-of-scale in the practice of law. That is the

cause of the A2J problem, i.e., no law firm has a sufficient volume of production in relation to each different

type of legal service produced to prevent its services becoming increasingly unaffordable.

Secondly, the higher the degree of specialization in relation to each cost-factor of production determines

the degree of cost-efficiency attainable. But the degree of specialization that is affordable is dependent upon

the volume of production. A producer is too specialized when it doesn’t have enough volume of specialized

work to pay for its specialists.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

7

To summarize: the costs of production are greatly reduced by high volumes of production, because: (1)

economies-of-scale are thereby maximized due to the fixed costs factor; and, (2) cost-efficiency is maximized

by making a higher degree of specialization affordable, which is determined by the volume of production.

It follows that the A2J problem is not one that a lawyer’s expertise is capable of solving unaided. It is not

a problem concerning issues of law and fact. It is a problem concerning the production of a service—lawyers

in private practice work in a service industry. Therefore, it is a problem for an economist specialized in the

interplay of simple economic factors in the production of various types of goods and services. But, given that

it is the duty of a law society to regulate the legal profession so as to make legal services adequately available,

it is a problem that law societies should have been attempting to solve by obtaining that necessary advice and

expertise. And, because it is a problem that is caused by the way in which lawyers do their work to produce

legal services, it is not a problem that law societies should expect governments to solve. It is law societies that

regulate lawyers, not governments. Lawyers’ problems as to, competence, ethics, and affordability, are all

produced by the way lawyers do their work. It is law societies that regulate lawyers and our legal profession

as a whole. Therefore, law societies should not be able to choose which ones of those three types of problems

they will deal with, and which they won’t.

Just as the need to use support services methods for the manufacturing of automobiles affordably for

middle-income people requires the existence of an auto-parts industry, similarly, the infrastructure whereby

medical services are produced is so very different and much more sophisticated than that used to produce legal

services. Choosing a law firm provides only the resources of the law firm chosen. But calling a specialist doctor

for an appointment, results in one being directed to see one’s family doctor first. The family doctor is also a

specialist—specialized in carrying out that sorting-triage process whereby the family doctor decides what

treatment he/she can provide, and where to send the patient for the rest of it, i.e., which specialist doctor,

technical test, technician, clinic or hospital service, the latest from medial science, drugs, etc. The innovation

in the way of doing the work for producing these various medical services never stops. In the legal profession,

it never started. Lawyers produce legal services in the same way that they have always produced them for the

last 300 years.

And all doctors’ work is specialized to a far greater degree than that of lawyers. For example, surgeons

confine their work to a single organ or system of the body, while a specialist lawyer does all the various types

of work within his/her specialty: interviewing clients; composing pleadings and proposals; negotiating; doing

legal research; going to court or tribunals; supervising subordinates; and perhaps having to do some law office

management work. Law firms don’t have the volume to afford a higher, more refined degree of specialization.

And so are the special-parts companies that collectively constitute the huge parts industry more specialized

than are the vendors of automobiles. A person works within a narrow specialty, but goes into it deeply, being

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

8

able to apply it in complex, demanding situations with greater efficiency and therefore greater volume of

production per unit of time.

4. Recommended Improvements Cannot Produce Affordability for Legal Services

But all of the recommendations that have been made in response to the present crises condition of the A2J

problem are restricted to improvements within the traditional law firm context as being the complete and sole

unit for the production of legal services, particularly so, making more use of computer programs.8 That means

attempting to obtain the desperately needed affordability that lawyers need by merely embellishing the very

obsolete cottage industry method of producing legal services. That is not possible. For example, no matter how

much one improves a bicycle’s performance by adding a motor, etcetera, it cannot solve a transportation

problem that requires an automobile or an airplane. Some improvement will be obtained in the use of the

bicycle, but a different technology of transportation will be required for the more demanding transportation

problems that require automobiles. Similarly, a different technology of production is required by lawyers if

their services are to remain affordable.

And such recommendations as to improving law office cost-efficiency come with no analysis as to what

impact such improvements will have on the state of the A2J problem, and, as to what additional efforts and

procedures are necessary to adequately cope with the problem. It is all well intentioned and commendable, but

it is driven forward with only a lawyer’s expertise. And therefore, there is no adequately expert analysis of

what the perpetuation of the present performance of law societies and governments within the justice system,

will do to the future of the legal profession.

Affordability cannot be achieved by merely embellishing an obsolete method of production, which is what

law societies recommend, e.g., lawyers should use more “apps” and other electronic technology within the law

office. Of course they should, but that is not going to re-establish affordability and an end the A2J problem. In

addition to achieving greater volumes of production than possible by law firms, there are procedures that

further maximize cost-efficiency that a support service can use that a law firm cannot use.

But no one within Canada’s justice system shows any interest in knowing the cause of the A2J problem, let

alone trying to solve and end it. The A2J effort being made is now huge, involving thousands of legally-trained

people who are involved with many different types of programs, government departments, law societies, retired

judges, and law professors and their students, and lawyers.9 Hereinafter, I refer to this consolidated body and

8

See infra note 30 and text.

9

For example, see the many, “Action Committee Members” of the Action Committee on Access to Justice in Civil

and Family Matters, and its prominent, “Justice Development Goals.” Its founder, in 2007, was the former Chief

Justice of Canada, Beverley McLachlin. There are other national projects such as, The National Self-Represented

Litigants Project providing assistance to civil and criminal court litigants without lawyers. And the Canadian Forum

on Civil Justice, produces its AJRN Roundup of summaries of published literature from several types of publications

and jurisdictions.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

9

its efforts as, “the A2J industry.” And in no part of the very large volume of literature that has been written

about the A2J problem does one see questions such as, “why is it that the way in which lawyers do their work

to produce legal services is not capable of producing affordable legal services for middle- and lower-income

people?” That would be the first thought of a new commercial producer of legal services, and of any person or

agency determined to solve the A2J problem.

That is to say, in relation to the more serious legal problems that require the services of lawyers, nothing

that is being done within the A2J industry seeks to: (1) control the growth of the A2J problem’s ability to cause

misery and damage by making lawyers’ services sufficiently affordable; and, (2) challenge the inadequate

performance of law societies and governments. For those thousands of people who are attaching themselves

and their careers to the efforts of the A2J industry, the above analysis of the A2J problem’s cause and cure is

irrelevant.

As a result, the per capita number of general practitioners of law is steadily decreasing, law society efforts,

and the efforts of the huge “A2J industry,” notwithstanding. As a result, the per capita number of lawyers in

private practice has been steadily decreasing for several decades—a process speeded-up by the growing

presence of the producers of commercially-produced legal services.10 It is a process that is leading to the de

facto de-regulation of the legal services market.11

The regulatory powers and resources of law societies cannot cope with all of the new competitors. But they

don’t try to cope. Their law practices are not yet sufficiently threatened by the unaffordability of their legal

services. Because there is no interest in knowing the cause of the problem, lawyers are not effective in making

themselves more competitive. Lawyers and law societies will not know how best to compete with all of the

10

For sources of statistics as to the shrinking per capita number of lawyers in private practice in the province of

Ontario; see: (1) Colin Lachance, “Law’s Reverse Musical Chair Challenge” (Slaw, June 16, 2016); see also the

many comments thereto, both ‘for’ and ‘against’); (2) the Law Society of Ontario’s, “Final Report of the Sole

Practitioner and Small Firm Task Force,” pages 50-54 (paragraphs 117-130) (March 24, 2005, reviewed in

Convocation, April 28, 2005, but no longer available online); and, (3) Christopher Moore, The Law Society of Upper

Canada and Ontario’s Lawyers 1797-1997, supra note 2 at p. 313, as to the decrease in lawyers in private practice

in the 1990s; and p. 380, as to the decrease in the number of lawyers in private practice between 1973 and 1982.

11

As to the extensive presence of commercial producers of legal services and the resulting de facto de-regulation of

the legal services market; see: (1) Suzanne Bouclin, Jena McGill, and Amy Salyzyn, “Mobile and Web-Based Legal

Apps: Opportunities, Risks and Information Gaps” (SSRN, June 16, 2017); (2) Ken Chasse, “Artificial Intelligence:

“Will it Help the Delivery of Legal Services but Hurt the Legal Profession?” (Slaw, November 21, 2018); (3)

University of Toronto Law Journal, vol. LXVI, No. 4, Fall 2016, “Focus Feature: Artificial Intelligence, Big Data,

and The Future of Law,” pp. 423-471; and, (4) University of Toronto Law Journal, vol. LXVIII, Supplement 1, 2018,

“Artificial Intelligence, Technology, and the Law,” pp. 1-124; and, Benjamin H. Barton, infra note 12, particularly

chapter 5, “LegalZoom and Death from Below”, pp. 85-103..

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

10

new sources of legal services—both those that exist now and will exist.12 Richard Susskind, an acknowledged

expert on the failings of law society management, provides this warning to the legal profession:13

In Tomorrow’s Lawyers,14 we predict that the legal world will change ‘more radically over the

next two decades’ than ‘over the last two centuries.’ Numerous commentators have echoed this view

of a legal profession on the brink of unprecedented upheaval. In truth, the working practices of lawyers

and judges have not changed much since the time of Charles Dickens [1812-1870].

[footnotes omitted]

5. Lawyers Are Giving Up Their Connection with Middle-Income and Lower-Income People

As a result, the legal profession, by way of the state of its law society leadership, is passively giving up

lawyers’ connection with middle- and lower-income people; they being the people who are the majority of

society, its taxpayers, and voters. As to the adequacy of that type of leadership of the legal profession,

Christopher Moore states:15

Around the world, legal scholars increasingly speculated that the century of the modern, self-

governing profession was coming to an end. The foremost local exponent, Professor Harry Arthurs of

Osgoode Hall Law School at York University, declared that self-governance by the legal profession

was quite simply ‘a dead parrot.’16 Since the drafting of the first Law Society Act in 1797, the one

central function of the Law Society has been to enable the profession to govern itself in the public

interest. If the Law Society is judged to have ceased to perform that function, then it perhaps ceases

to be an essential institution. As the Law Society of Upper Canada approached the end of its second

century, solid reasons could be found to doubt that it would complete its third.

What impact will that have upon the position of the legal profession within society? Won’t the profession’s

purpose, power, and prestige be significantly lessened? And in what state will we, the profession’s senior

lawyers, be leaving the legal profession in for the present young lawyers and law students who will be serving

the next 40-50 years or more, in the practice of law coping with that very poor legacy while we are comfortably

retired? Our law societies should have altered themselves to be able to do more, much more of what is

commendable than merely engaging in the very corrupt, self-interested work that being a bencher provides to

an ambitious practicing lawyer.

12

As to such competitors, see: (1) Richard and Danial Susskind, The Future of the Professions, (Oxford University

Press, 2015), at pp. 66-71; (2) Noel Semple, Legal Services Regulation at the Crossroads, (Edward Elgar Publishing

Limited, 2015); (3) Trevor C.W. Farrow, and Lesley A. Jacobs (eds.), The Justice Crisis-The Cost and Value of

Accessing Law, (UBC Press, 2020); (4) generally the other books authored by Richard Susskind, supra note 2; and,

(5) Benjamin H. Barton, Glass Half Full-The Decline and Rebirth of the Legal Profession, (Oxford University Press,

2015).

13

Susskind, The Future of the Professions, (2015), supra note 2, at p. 66.

14

Supra, notes 2 and 11 and texts.

15

Christopher Moore, The Law Society of Upper Canada and Ontario’s Lawyers 1797-1997, supra note 3, at p. 339.

“Upper Canada” being Ontario’s title while still a British colony until, July 1, 1867. “Upper Canada,” because it is

further up the St. Lawrence than is Lower Québec, the province of Quebec.

16

H.W. Arthurs, “The Dead Parrot: Does Professional Self-Regulation Exhibit Vital Signs?” (1995), 33, no. 4

Alberta Law Review.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

11

It is law societies that should be helping lawyers to make significantly smaller the gap between the size of

lawyers’ fees and what middle-income and lower-income people can afford. Then lawyers and law societies

could effectively advertise the substantial protections provided by the lawyer-client relationship, which are:

(1) the fiduciary duty devotion to the client, who is not a mere customer in the commercial

buyer-seller competitive world as are some of the other sources of legal services;

(2) law society financial oversight;

(3) law society discipline procedures, i.e., an investigation of a client’s complaint can lead

to a prosecution of the lawyer;

(4) a code of professional conduct to be obeyed;

(5) professional insurance to provide financial compensation for damage done by one’s

lawyer; and,

(6) continuing professional development requirements (CPD/CLE obligations) to maintain

competence and ethical practice.

Like the doctor-patient relationship, it has no equal competitor in the provision of legal services. People know

that, and make that comparison. Potential clients will pay a little more, or somewhat more for those safeguards

and protections. But most cannot pay a lot more as is too often required now by the size of lawyers’ fees.

In 2005, LSO acknowledged that A2J problem was in a “crises stage.”17 But the managers and workers of

the A2J industry are devoted to providing only legal information of various types including how to avoid legal

problems, and very simplistic legal services provided by paralegals and other persons of lesser legal training

than lawyers, and by lawyers doing short, simple cases pro bono. It is all a necessary part of coping-best with

the problem of unaffordable legal services, but only if one is somehow justified in not trying to solve the A2J

problem. The benefits obtained from such A2J industry efforts will be minor in comparison with the much

greater benefits that could be obtained from solving the A2J problem. The most necessary benefit being

affordable lawyers for the more difficult, threatening, and potentially life-altering legal problems. The A2J

industry’s efforts and large presence aids the law societies in their failure and refusal to seek a solution for

their unaffordability, i.e., a solution for the much greater part of the A2J problem’s ability to cause misery and

damage. Canada’s law societies always limit the scope of their activities and declared duties so that they do

not have to change, and most definitely not have to change their bencher-building-block management structure

because of its career-promoting purpose for ambitious lawyers.18

But there is no such solution of the problem being sought so as to help general practitioners be financially-

viable lawyers, e.g., no law society has a program the purpose of which is to solve the problem. General

practitioners are the lawyers who provide legal services for middle- and lower-income people, they being the

majority of the population. As a result, the A2J problem has made most lawyers short of clients because no

17

See: the Law Society of Ontario’s Minutes of Convocation, March 24, 2005.

18

See also supra note 7 and accompanying text.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

12

effort is being made by law societies and governments in Canada to understand the cause of the problem let

alone try to solve it. 19 The A2J industry’s efforts are necessary and commendable, but they should be

accompanied by equally diligent efforts to challenge law societies and governments to do what is ethically

required and necessary to solve and end the A2J problem. Because they don’t, the A2J industry in effect,

supports and helps to perpetuate a state of affairs in the management of the legal profession and of the justice

system that is frightening and sinister. Professor Emeritus Michael Trebilcock of the Faculty of Law of the

University of Toronto has stated it well:20

… . Fourth, in an era of widespread public cynicism about the competence and integrity of

government generally, the self-regulatory model of governance of the legal profession is increasingly

under challenge, fuelled by apprehensions that it is motivated less by regulation in the public interest

and more by regulation in the interests of members of the legal profession, and reflects an abdication

of responsibility by democratically elected governments.

Law societies should be replaced with permanently employed lawyers, other types of expertise and staff

members. Are not the present efforts being made by the vast A2J industry merely an attempt to provide

remedies without eliminating causes, which has the character of being “wilfully blind” to the need for a

complete solution?

As an example of a law society’s opinion of the scope of its duty to regulate the legal profession, in 2019

the Treasurer of the Law Society of Ontario (LSO’s chief executive officer), stated in effect, that the A2J

problem is the government’s problem.21 And, the Law Society is to regulate legal services so as merely to,

facilitate access to justice, so he said.22 But, shouldn’t “facilitate” include regulating the method by which

lawyers produce legal services so that it has the necessary cost-efficiency to produce affordable legal services

for middle- and lower-income people? If not, we should debate whether it is appropriate now in the 21st century,

for law societies to state their regulatory duties in such modest early 19th century terms, i.e., what interpretation

should be given to statutory statements as to a law society’s statutory and regulatory duties? 23 A rule of

19

As to lawyers’ shortage of clients, see for example, Nandini Ramanujam and Alexander Agnello (of McGill

University), “The Shifting Frontiers of Law: Access to Justice and Underemployment in the Legal Profession,

(2017), 54, Issue 4, Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 1091-1116 (article 6).

20

See Professor Trebilcock’s written “Foreword” to this book by Professor Noel Semple, Legal Services Regulation

at the Crossroads, supra note 11 at p. vi.

21

See supra note 6 and text.

22

As to such a limited formulation of law society duties, see: Ken Chasse, “Law Society Policy for Access to Justice

Failure,” Slaw, July 25, 2019. For my reply to the Treasurer’s comment, see: (1) “Law Society Policy for Access to

Justice Failure, Part Two,” Slaw, April 9, 2020. (2) “Society’s Income-Inequality Unrest and Law Society Access to

Justice Failure,” Slaw, May 29, 2020; and, (3) “Law Societies’ ‘Bencher Burden’ Causes the Access to Justice

Problem,” Slaw, August 6, 2020. And there are other relevant comments attached to those blog articles.

23

For example, in the province of Ontario, the Law Society Act, s. 4.2, states in relevant part:

In carrying out its functions, duties and powers under this Act, the Society shall have regard to the following

principles:

1. The Society has a duty to maintain and advance the cause of justice and the rule of law.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

13

statutory interpretation states: “the law is always speaking,” i.e., words in a statute don’t remain fixed like a

museum piece regardless of the need for a more modern interpretation.

That is to say, the duties stated in s. 4.2 of Ontario’s Law Society Act are not to remain fixed in their

interpretation to a 19th century era of “gentlemen’s club” type law societies wherein Canada’s law societies

wish to dwell. The Treasurer of the Law Society of Ontario choses only word, “facilitate,” among all of the

words used to express the four stated duties in s. 4.2. Law societies are required to regulate lawyers, particularly

so, the way lawyers do their work to produce legal services, i.e., lawyers are to be, competent, ethical, and

affordable. If law societies will not willingly broaden their scope of perceived duty, Canada’s Attorneys

General should replace them with institutions of much greater competence and devotion to serving the public.

Why don’t governments hold law societies to account for the performance of their statutory duties as to

regulating the legal profession? The answer is that elected governments want to spend that money on the more

fruitful vote-getting activities of the voters. So, the relevant politically-wise question is, how much does the

average voter think about his/her need for judges, courts, court administrative staff, law societies, prosecutors,

and Legal Aid’s funding? Not very much at all, if they think about it at all. And to put forward a creditable,

fear-inducing threat of replacing law societies would require governments to know: what to replace law

societies with; how much would it cost; how disruptive would it be; and, how long would such a threatening

government be tied up in the courts fighting desperate, outraged law societies that have been put in fear of the

extinction of their very cherished early 19th century gentlemen’s club, career-promotion existence. So it is that

governments leave law societies alone because there are no significant quantities of votes to be gained by

replacing them.

That has shaped the whole history and institutional culture of Canada’s law societies since they were created

more than 220 years ago. 24 They act like private gentlemen’s clubs, that now include lady lawyers. 25

2. The Society has a duty to act so as to facilitate access to justice for the people of Ontario.

3. The Society has a duty to protect the public interest.

4. The Society has a duty to act in a timely, open and efficient manner.

24

For example, the Law Society of Upper Canada (LSUC), was created on July 17, 1797, by ten practitioners at the

little town now known as, Niagara-on-the Lake, which is at the north end of the Niagara River where it flows into

Lake Ontario, bringing waters from the eastern end of Lake Erie. As of January 1, 2018, LSUC now has the title, the

Law Society of Ontario (LSO).

25

The concept of the “gentleman lawyer” in the British colony of Upper Canada (now the province of Ontario), and

within its Law Society of Upper Canada (LSUC), as being a gentlemen’s club, persisted from its beginning and

throughout the 19th century, i.e., being a “gentleman” appears to have been given priority over being a lawyer, which

was somewhat like having a hobby-farm. But thereafter, the concept of “professionalism” displaced” the

“gentleman” in priority. But law societies’ institutional culture of “the private gentleman’s club” persists with no

signs of being displaced; see: Christopher Moore, The Law Society of Upper Canada and Ontario’s Lawyers, 1797-

1997, supra notes 4 and 15, at: pp.20-26; 43-45; 144-147; and 152. LSUC moved into Osgoode Hall, in what is now

downtown Toronto, in 1832, which is when its construction by way of beautiful early-nineteenth century

architecture was completed; see: Moore, at p 82. William Osgoode became the first Chief Justice of Upper Canada

and established its courts system (1792-94); see Moore, pp. 20-26.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

14

Gentlemen’s clubs are self-owned, so it is that they will determine what in fact their purpose is, and what duties

they will perform. They live above the law. De facto, the rule of law does not apply to Canada’s law societies.

Putting into words what exactly has been their overriding purpose, a law society is to provide that career-

promoting and embellishing mechanism for an ambitious lawyer by serving as a bencher. Such service can

provide: greater prominence and name-recognition in the legal profession; proof of one’s popularity in the

profession which is what gets a lawyer elected to be a bencher; helping to provide the appearance of a

successful lawyer, which can impress some types of clients; and, it is a type of community service by helping

a law society to fulfill its purpose to serve the community. Therefore such “bencher-service,” can be helpful

in becoming a judge.

But a bencher is also a practising lawyer, and must always be careful to have enough time to be a good

lawyer for one’s clients or institutional employer. That also limits the kind of work that a bencher can do—

they don’t become involved in bringing about any significant innovation or large-scale change without

significant assistance from other sources. Such endeavors require development periods of uncertain length,

difficulty, and cost. One doesn’t become a bencher to risk being associated with an expensive failure. Such

conditions of uncertainty and risk-taking are incompatible with the working situation of a practising lawyer.

Therefore, the continuation of the concept of the bencher-building-block of law society management means

that law societies cannot change in any significant way. So, they don’t, and they won’t because history dictates

that, “organizations do not change until the fear of the consequences of not changing are greater than the fear

of the consequences of changing.” Canada’s governments clearly do not wish to instill that greatly needed

therapeutic fear, and its law societies show no signs of enduring that fear. Indeed, they evince a mentality and

institutional culture that is quite the contrary. And so it is that our law societies are no more competent they

have always been, i.e., since they were created more than 220 years ago. However, we cannot expect that what

is now at best, an early 19th century law society in fact, in mentality and motivation to be a competent 21st law

society in performance. But that has long been considered to be “business as usual,” what each new generation

finds to be normal, commendable, traditional, deserved, and most likely the only way to be a law society.

For example, creating a support service system for the production of legal services is very incompatible

with the working situation of the bencher-lawyer. They would have to decide which parts of lawyers’ work

could be more cost-efficiently done by support services. Then they would have to marshal the necessary human

and physical resources to set them up and get them functioning, which would probably best be done by securing

some private financing and investment. But by applying investment money to the creation of such support

services instead of allowing law firms to become investment properties themselves (“Alternative business

structures” they are called), the legal problems as to non-lawyers owning law firms and thereby potentially

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

15

controlling the production of legal services, won’t happen.26 But then, benchers will have to perform what I

found to be the most difficult part of establishing a successful support service—the marketing function of

getting lawyers to use such support services. Difficult because being dependent upon something that is not

under a lawyer’s control in servicing a client’s needs, especially something as important as the doing of good

legal research, is contrary to the belief that a good lawyer has control of all of the work and assistance that

goes into the production of legal services. Especially so even though legal research done by a support service

can be the source of the necessary cost-saving in the production of legal services.

6. A Civil Service for Law Societies

All of that will involve a development period of an uncertain length, cost, and difficulty. Benchers cannot

afford the time necessary to carry out or endure such a development process. Therefore, given present

circumstances and entrenched thinking, it isn’t going to be made to happen for all lawyers. Nor is the A2J

problem ever going to be solved. But they could both be made to happen if there were a national civil service

for law societies. Our law societies operate as would an elected government without a civil service, which

makes the A2J problem inevitable.

But also, such a badly needed civil service is not going to happen as long as the present state of an

entrenched stasis of the major institutions of the justice system exists. It has created the A2J problem.

Governments don’t want to hold law societies to account for the performance of their duties, and law societies

don’t want to change in any significant way from their early 19th century origins and concepts of management.

And so far, the legal profession has no interest in changing its method of producing legal services—at least

not until lawyers fear the loss of their law practices because they have become very unaffordable, which will

happen because all lawyers practice law in the same very obsolete way. That will force a conversion to support

services methods of production. But by then, the general practitioner will have disappeared. And the vast A2J

industry shows no interest in challenging this situation of incompetent management of the justice system and

its legal profession. Therefore, the A2J industry doesn’t challenge law societies and governments as to the

need for them to work towards creating a solution to the A2J problem. Thus, this state of justice system affairs

will result in the permanent and ever-dynamic, fast moving and destructive presence of the A2J problem.

In other words, Canada’s law societies are managed by part-time amateurs and our law societies perform

as would an elected government without a civil service. So, for them and us, we should give them a civil

service—just one national civil service for all law societies because their major problems are the same national

problems. A civil service has the essential features for good government that an elected Cabinet government

does not have: (1) it is permanent; (2) it has all of the necessary different kinds of expertise; (3) it has a long-

26

See: Ken Chasse, “Alternative Business Structures’ ‘Charity Step’ to Ending the General Practitioner” (SSRN,

September 30, 2018.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

16

term knowledge of, and experience dealing with the justice system’s and legal profession’s most difficult,

intractable problems; and therefore, (4) it can carry out projects needing long-term development that can bridge

elections thereby maintaining a long-term continuity of knowledge and effort because its chief executive group

is permanent. It does not have much more important career commitments elsewhere, and a more substantial

source of income elsewhere as do benchers. But bencher-management cannot do that because it has only one

type expertise which it makes available only part-time, and only for an elected period (Ontario-4 years; British

Columbia-2 years). Instead, there needs to be 21st century permanent and competent administration. And,

bencher-management has no long-term experience as does a civil service. Such a civil service could do all the

various types of work and promotion necessary to establish a support-services method of producing legal

services. That will take some few or several years, plus on-going permanent maintenance duties, which bencher

self-interest is not motivated or able to provide. But a civil service for law societies would have both the

necessary skills and motivation, being a national institution for a very important profession.

The elected Cabinet ministers serve for only the short term between elections and don’t engage in

sophisticated long-term planning that a civil service can become very expert at providing. Thus, if benchers

can act like a government’s cabinet ministers without having also to be their own civil service, that would

remove much of, or all of the conflict of interest between benchers’ serving their personnel, career-promotion

interests, which are very incompatible with also being able to be competent managers of a law society lacking

a civil service. Financing the daily operations of this civil service for Canada’s law societies is described below.

7. The Application of the Support Services Method to Establish a Legal Research Support Service

I learned the above analysis of the cause and solution to the A2J problem by establishing a large volume,

highly specialized legal research support service that produced thousands of legal opinions for several

hundreds of lawyers per year. I was hired by what is now entitled, Legal Aid Ontario (LAO)27 to provide a

sufficient response to a government complaint that too much money was being paid out on lawyers’ accounts

for legal research hours billed to LAO.28 The service created, did the legal research for those lawyers instead

27

By way of the Legal Aid Services Act, 1998, the Law Society of Upper Canada (now entitled the Law Society of

Ontario as of January 1, 2018), was removed as the manager of the Ontario Legal Aid Plan (OLAP, “the Plan”), that

Act incorporating OLAP to become, Legal Aid Ontario. Such was the government’s reaction to two investigative

reports of the law society’s management of OLAP, both dated 1997: (1) the McCamus Report (by Professor

McCamus): Report of the Legal Aid Review – A Blue Print for Publicly Funded Legal Services, Executive

Summary; and, (2) Professors Zemans & Monaghan, From Crisis to Reform: A New Legal Aid Plan for Ontario

(available in hardcopy at the Osgoode Hall Law School Library, and, the Great Library at Osgoode Hall. Both

concluded that the law society should not be the manager of legal aid for reasons of, conflict of interest and failure

to innovate. As to the McCamus Report, see online: Volume 1; Volume 2; and, Volume 3. Ontario’s Legal Aid

Services Act, 1998, was replaced in October 2021, by the, Legal Aid Services Act, 2020.

28

The province of Ontario has a judicare system of legal aid, as distinguished from a public defender system. The

judicare system depends entirely on lawyers in private practice to provide the legal services. For a public defender

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3989039

17

of having them billing LAO for doing their own legal research. After several years of development, my staff

were producing close to 5,000 legal opinions per year for those lawyers in private practice willing to service

Legal Aid cases. Rare is the law firm that can produce that volume of legal services. The legal opinions were

meant to replace or supplement lawyers’ doing their own legal research.

I highly specialized these factors of production: (1) my staff of lawyer-legal researchers; (2) the volume

and kinds of analytical legal materials available; and, (3) the principles of database management. In addition,

there are procedures and materials that such a support service can use that a law firm cannot have. Thereby the

cost-efficiency that a support service can achieve is far greater than that of any law firm. That is why the legal

profession should use a support service method of production. Inter alia, law firms using a support-service

method of production will be able to serve their clients with greater convenience, and they will make more

money.

My lawyer-researchers did legal research all day; all year. And they did their research in only one major

area of law—most of which was in criminal and family law, as are the great majority of cases for which LAO

provides financial assistance by way of paying for services of lawyers in private practice. I had a group of

researchers doing only criminal law research, and another doing only family law research. And another lawyer

did research in other areas of law for the small number of cases for which LAO provides such assistance.29

Such a high degree of specialization provides a very high degree of cost-efficiency. Lawyers working in such

very narrow fields of specialization can produce a high volume of their type of work-product per unit time

because of the very high degree of efficiency thereby obtained by doing only one of the several types of work

required to produce any legal service.

No law firm can afford that degree of specialization. Specialized lawyers in law firms do all of the various

different types of work within their specialty, such as: drafting pleadings and proposals; negotiating;

interviewing; meeting with colleagues; going to court and tribunal proceedings; legal research; supervising

subordinates; and, perhaps carrying out some office management functions; etcetera. They do not do only one

of those types of work such as legal research. And similarly, is the work-pattern of any lawyers or law students

assisting each such specialized lawyer. And they won’t have the same degree of facility and cost-efficiency as

does a lawyer doing only legal research as a long-term specialization in only one major area of law. A large

law firm may have a legal research group of lawyers. But they will be on-call by all of the various practice

groups in the law firm. Therefore, they cannot confine their research work to only one major area of law. That

limits their cost-efficiency and therefore their speed of production. Perhaps a single practice group could afford

system, the legal aid organization has its own employee-lawyers. Most provinces in Canada use a mixed method of