Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Avaliação Da Eficácia Da Intervenção em Grupo Com Mulheres Vítimas...

Avaliação Da Eficácia Da Intervenção em Grupo Com Mulheres Vítimas...

Uploaded by

dana1520Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Intentional Change Model: Discover A Personal Vision and Ideal Vision of MyselfDocument2 pagesIntentional Change Model: Discover A Personal Vision and Ideal Vision of MyselfAkriti DangolNo ratings yet

- The Historical Origins of Psychology: Dr. Sasmita MishraDocument21 pagesThe Historical Origins of Psychology: Dr. Sasmita MishraRAJ KUMAR YADAVNo ratings yet

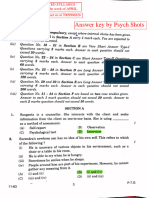

- Answer Key Psychology Cbse Board Exam 2024 by Psych ShotsDocument9 pagesAnswer Key Psychology Cbse Board Exam 2024 by Psych Shotsjay752689No ratings yet

- FGD Sample.Document3 pagesFGD Sample.Md. YousufNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Objectives of Psychodiagnostic AssessmentDocument6 pagesChapter 5 Objectives of Psychodiagnostic Assessmentrinku jainNo ratings yet

- History of Mental Health CareDocument25 pagesHistory of Mental Health CareDewi IriantiNo ratings yet

- (Đề thi có 05 trang)Document18 pages(Đề thi có 05 trang)Lan Anh TạNo ratings yet

- Shs The Nursing Process and The Nursing Care PlanDocument35 pagesShs The Nursing Process and The Nursing Care PlanAnne Margarette Claire ChungNo ratings yet

- FLCT Chapter 2Document7 pagesFLCT Chapter 2rhealyn8lizardoNo ratings yet

- KDK Case Report 2 - Group BDocument13 pagesKDK Case Report 2 - Group BFUZNA DAHLIA MUDZAKIROH 1No ratings yet

- Concept, Need and Function of TeachingDocument6 pagesConcept, Need and Function of TeachinganandNo ratings yet

- Hallucinations Behavior Experience and Theory R K Siegel and J J 1976Document2 pagesHallucinations Behavior Experience and Theory R K Siegel and J J 1976Guilhermin GRMNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 - Creation of Healthy and Caring Relationships: A Scientific Approach To Health AEC 26Document23 pagesUnit 3 - Creation of Healthy and Caring Relationships: A Scientific Approach To Health AEC 26akash DongeNo ratings yet

- Pooja Joshi PDFDocument64 pagesPooja Joshi PDFHarshita TiwariNo ratings yet

- The Power Of: Human ImaginationDocument414 pagesThe Power Of: Human ImaginationAngelika SomogyiNo ratings yet

- Holistic Development of Adolescent.Document30 pagesHolistic Development of Adolescent.JM Favis CortezaNo ratings yet

- Module 7 VolunteerismDocument12 pagesModule 7 VolunteerismAngel Calipdan ValdezNo ratings yet

- Psychological Assessment AssignmentDocument33 pagesPsychological Assessment AssignmentFatima AbdullaNo ratings yet

- Intercambio Idiomas Online: Word Formation: PeopleDocument3 pagesIntercambio Idiomas Online: Word Formation: PeopleMariia KaverinaNo ratings yet

- Functional Assessment Interview Form-Young Child: Module 3aDocument8 pagesFunctional Assessment Interview Form-Young Child: Module 3aNBNo ratings yet

- Qualities of Health Care ProviderDocument8 pagesQualities of Health Care ProviderBenedic ClevengerNo ratings yet

- Law of Developmental MotivationDocument17 pagesLaw of Developmental MotivationRegie Arceo BautistaNo ratings yet

- The Schooler and The FamilyDocument30 pagesThe Schooler and The FamilyGrace EspinoNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal Template SampleDocument26 pagesResearch Proposal Template SampleFrace RojoNo ratings yet

- Anti-Ligature Nozzle - Open Type: HydramistDocument2 pagesAnti-Ligature Nozzle - Open Type: HydramistalbertoNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Benefits of Laughter in Mental HealthDocument8 pagesTherapeutic Benefits of Laughter in Mental HealthYanti HarjonoNo ratings yet

- Social Support For Families Tested Positive For Covid-19: Dukungan Sosial Pada Keluarga Yang Divonis Positif Covid-19Document9 pagesSocial Support For Families Tested Positive For Covid-19: Dukungan Sosial Pada Keluarga Yang Divonis Positif Covid-19toto ekosantosoNo ratings yet

- Andrew Tate - Fix Your BrainDocument14 pagesAndrew Tate - Fix Your BrainnanyafnanNo ratings yet

- Final Case Study: Louise BourgeoisDocument6 pagesFinal Case Study: Louise Bourgeoisapi-545911118No ratings yet

- Module 1 and 2 Diass PDF FreeDocument24 pagesModule 1 and 2 Diass PDF FreeSheena May QuizmundoNo ratings yet

Avaliação Da Eficácia Da Intervenção em Grupo Com Mulheres Vítimas...

Avaliação Da Eficácia Da Intervenção em Grupo Com Mulheres Vítimas...

Uploaded by

dana1520Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Avaliação Da Eficácia Da Intervenção em Grupo Com Mulheres Vítimas...

Avaliação Da Eficácia Da Intervenção em Grupo Com Mulheres Vítimas...

Uploaded by

dana1520Copyright:

Available Formats

675226

research-article2016

SGRXXX10.1177/1046496416675226Small Group ResearchSantos et al.

Article

Small Group Research

1–28

Effectiveness of a Group © The Author(s) 2016

Reprints and permissions:

Intervention Program sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1046496416675226

for Female Victims sgr.sagepub.com

of Intimate Partner

Violence

Anita Santos1,2, Marlene Matos3, and

Andreia Machado3

Abstract

Group intervention has been widely used with female victims of intimate

partner violence (IPV). However, efficacy studies are scarce due to several

research limitations. This study evaluates the effectiveness of an 8-week

group intervention program, with a cognitive-behavioral orientation and

attended by 23 female victims of IPV. Self-report psychological assessment

was conducted at pre-test, post-test, and follow-up. Results revealed that the

group intervention had a positive impact on participants, showing a decrease

in re-victimization and in beliefs toward legitimizing IPV. A decrease in levels

of depression and a significant improvement in general clinical symptoms

were also evident. Self-esteem and social support were enhanced throughout

group intervention. The changes were confirmed through follow-up after

3 months, suggesting that this group intervention has important effects on

female victims. The implications of the findings for practice are also discussed.

Keywords

group intervention, effectiveness, intimate partner violence, women victims

1ISMAI—Maia University Institute, Portugal

2Center for Psychology at University of Porto, Portugal

3University of Minho, Braga, Portugal

Corresponding Author:

Anita Santos, Maia University Institute, Av. Carlos Oliveira Campos, Castelo da Maia

4475-690 Avioso S. Pedro, Portugal.

Email: anitasantos@ismai.pt

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

2 Small Group Research

Group intervention has been widely used with female victims of intimate

partner violence (IPV). However, in Portugal, no study on the efficacy of this

type of intervention has been performed. This study presents a group inter-

vention proposal with 23 female victims of IPV and its longitudinal assess-

ment via a pre-test, post-test, and follow-up test.

It was during the last century that IPV became recognized, and was

socially and judicially condemned, and studied (e.g., Eckhardt et al., 2013;

Gordon, 1996; McBride, 2001), acquiring the status of global and social

problem (e.g., Abel, 2000; Crespo & Arinero, 2010; Kim & Kim, 2001;

Matos, Santos, & Dias, 2013). In recent decades, worldwide, we saw several

changes in criminal law, a proliferation of information on the subject, an

upsurge of cases in the criminal justice system, and increased media exposure

on this issue.

However, despite the various approaches developed to stop and prevent

IPV, this social problem still endures. For instance, results from the recent

National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey reveal that, during

their lifetime, one in four women in the United States experience severe

physical violence, one in two are psychologically abused, and one in 10 are

raped, perpetrated by the intimate partner (Breiding, Chen, & Black, 2014).

In Europe, recent data reveal that victimization of women cannot also be

underestimated: one in three women have experienced physical and/or sexual

victimization after the age of 15 (European Union Agency for Fundamental

Rights, 2014). In Portugal, where this study took place, IPV is acknowledged

as a prominent issue since the 1990s (e.g., Commission for Citizenship and

Gender Equality—Presidency of the Council of Ministers, 2015); it has been

a public crime since 2000. Still, the Portuguese criminal statistics in 2015

indicated that IPV was the second most reported crime in the category of

crimes against people (N = 22,569), and 84% of the victims were women

(Ministério da Administração Interna, 2016). Moreover, a wide survey in

Europe revealed that there is a high level of women victimization, with 24%

reporting having experienced physical and/or sexual abuse perpetrated by a

partner and/or by another person (European Union Agency for Fundamental

Rights, 2014).

Psychological interventions with female victims have been considered

very important to reduce the high personal, interpersonal, and societal costs

that are usually associated with IPV (e.g., Pico-Alfonso et al., 2006; Sartin,

Hansen, & Huss, 2006; Stover, Meadows, & Kaufman, 2009). In particular,

female victims reported high levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, disso-

ciation, substance abuse, sexual problems, cognitive disorders, low self-

esteem, and somatization (e.g., Briere & Jordan, 2004; Coker et al., 2002;

Constantino, Kim, & Crane, 2005; Iverson, Shenk, & Fruzzeti, 2009; Lundy

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

Santos et al. 3

& Grossman, 2001). Alongside are behavioral and relational difficulties, as

well as the destructive aspect (homicide and suicide) and highly disabling

consequences of maltreatment (e.g., Abel, 2000; Lundy & Grossman, 2001;

Pico-Alfonso et al., 2006).

Currently, there are different expert responses on this issue (e.g., Abel,

2000; Bennett, Riger, Schewe, Howard, & Wasco, 2004; Stover et al., 2009).

In Portugal, victims can be referred to support agencies and eventually admit-

ted to shelters. In terms of intervention, the most common is individual crisis

intervention. Some support agencies and shelters provide individual therapy,

while few provide group intervention; no standardized type of intervention

has been implemented. Female victims can seek help on their own, or can be

referred by public institutions or criminal police bodies. On the other hand,

group intervention for male perpetrators is usually court mandated, with

recent evidence of efficacy (e.g., Cunha & Gonçalves, 2015).

However, while literature has been accumulating knowledge on the sub-

ject, research about the effectiveness of the psychological interventions and

the processes involved in women’s positive changes remained philosophical

rather than empirical. Consequently, little is known about the effectiveness of

the interventions available (e.g., Eckhardt et al., 2013; Ramsay, Rivas, &

Feder, 2005; Stover et al., 2009).

Group Intervention With Female Victims of IPV

Group intervention has emerged internationally as the most common type of

intervention with female victims of intimate violence. This type of interven-

tion has been considered to have a positive impact on women (e.g., Abel,

2000; Gordon, 1996; Tutty, Bidgood, & Rothery, 1993). Participation in a

group intervention with victims of IPV often derives from the need, usually

expressed by women, to share their experience with other women with simi-

lar life journeys (Tutty & Rothery, 2002). Group therapy has shown great

pragmatism in addressing the problems brought by this population, and

allows significant efficacy in the consolidation of the results achieved at indi-

vidual level (e.g., Machado & Matos, 2001).

This type of intervention is innovative in Portugal and may provide sev-

eral potential gains, in addition to cost-effectiveness. On one hand, it may

allow participants to validate their experience of victimization, offering them

encouragement, support, and information (e.g., Fritch & Linch, 2008; Iverson

et al., 2009; Liu, Dore, & Amrani-Cohen, 2013). On the other hand, women

who participate in this form of intervention reduce their social isolation, a

problem common to this population, as it enables a new network of relation-

ships (e.g., Fritch & Linch, 2008; Iverson et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2013). It can

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

4 Small Group Research

also provide an opportunity to learn from other women, identifying common

difficulties and sharing strategies for problem solving (e.g., Fritch & Linch,

2008; Iverson et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2013). The group context can help

women “to realize that she is not alone and that her feelings of confusion, fear

and despair are real and shared by other women” (Webb, 1992, p. 209). Thus,

clinical symptomatology, beliefs toward violence, personal and social skills,

social support, and self-esteem are important indicators of change in this type

of intervention.

Although scarce, international literature has highlighted the success of

group intervention, especially in reducing female victims’ tolerance toward

violence and abuse, as well as increasing their personal and social skills (e.g.,

Bennett et al., 2004; Gordon, 1996; Tutty et al., 1993). Efficacy studies have

found significant improvements in areas such as self-esteem (e.g., Crespo &

Arinero, 2010; Kubany et al., 2004; Tutty, Babins-Wagner, & Rothery, 2016),

attitudes comparable to those found in a healthy marriage and family (e.g.,

McWhirter, 2011; Ramsay et al., 2005; Schwartz, Magee, Griffin, & Dupuis,

2004), an increase in social support and coping (e.g., Crespo & Arinero,

2010; Iverson et al., 2009; McWhirter, 2011), and a decrease in violence,

anger, depression, and stress (e.g., Iverson, Gradus, Resick, Suvak, & Smith,

2011; McWhirter, 2011; Tutty et al., 2016). Other group interventions have

been used to assist with dating relationships, and risk factors have provided

positive evidence supporting group intervention (Constantino et al., 2005;

McBride, 2001; Schwartz et al., 2004). The available studies conducted about

group intervention reveal that most of the interventions are based in several

different theoretical frameworks: (a) psychoeducational (e.g., Cox &

Stoltenberg, 1991; Crespo & Arinero, 2010; Holiman & Schilit, 1991;

McBride, 2001; McWhirter, 2011; Schwartz et al., 2004), (b) cognitive-

behavioral (e.g., Cox & Stoltenberg, 1991; Crespo & Arinero, 2010; Holiman

& Schilit, 1991; Kubany et al., 2004; McBride, 2001; McWhirter, 2011,

Rinfret-Raynor, & Cantin, 1997), (c) feminist (e.g., Cox & Stoltenberg, 1991;

Holiman & Schilit, 1991; McBride, 2001; Rinfret-Raynor & Cantin, 1997),

and also (d) narrative approach (Tutty et al., 2016). Psychological interven-

tion with groups tend to last between eight and 12 sessions (e.g., Crespo &

Arinero, 2010; McBride, 2001; Constantino et al., 2005), as recommended in

the literature (e.g., Yalom, 1995). Nevertheless, there are studies that utilize

short-term therapy (Cox & Stoltenberg, 1991; McWhirter, 2011; Schwartz

et al., 2004) and others that adhere to alternative therapies, such as Dialectical

Behavior Therapy (cf. Iverson et al., 2009), achieving equally positive results.

In a psychoeducational intervention program of Cox and Stoltenberg

(1991), with 21 women, an experimental design was used, with both a pre-

and a post-test assessment and control groups, which lasted 2 weeks (3 times

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

Santos et al. 5

a week, for a total of 12 hr). Holiman and Schilit (1991) assessed 12 victims,

in a psychoeducational and support group through 10 sessions, with a pre-

and a post-test. Rinfret-Raynor and Cantin (1997) compared three forms of

feminist intervention—group, individual, and treatment as usual—with 60

women, with pre- and post-test assessment, and follow-up after 6 and 12

months. Support groups of 12 weeks, were also assessed by Tutty and col-

leagues (1993) in a quasi-experimental design, with pre-test, post-test, and

follow-up assessment of 76 victims. McBride (2001) evaluated support group

intervention, over 24 sessions with a total of 189 women. Despite the large

sample size, there was no control group and no follow-up assessment was

implemented. Schwartz and colleagues (2004) used a similar approach with

28 women, without a follow-up assessment. A pilot study with an experimen-

tal design (Constantino et al., 2005) was conducted in which intervention

groups were implemented with 24 women to promote social support, over 8

weeks. Crespo and Arinero (2010) evaluated two types of group intervention

that lasted 8 weeks, with 53 women in an experimental design, with pre- and

post-test assessment, and follow-up after 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. Liu,

Morrison, and Amrani-Cohen (2013) compared two very different models of

group intervention: a support group and a self-defense group. The first lasted

12 weeks, and the second lasted 10 weeks. The researchers evaluated 69

women for depression and self-esteem. The design had a pre- and post-test

assessment. There were no differences between groups; however, women had

improved in self-esteem and decreased depressive symptoms. Group therapy

with a narrative approach was implemented during 14 weeks and was evalu-

ated through a pre- and a post-test (Tutty et al., 2016).

Regarding the aims of the intervention, the majority of these studies pre-

sented outlined the following as the most common goals: to validate the per-

sonal stories of victimization, to stimulate empowerment, to restore control

over daily life, to reduce social isolation, to develop problem solving and

decision making, and to promote personal and social skills (e.g., Matos &

Machado, 2011).

In the composition of such intervention groups, there is usually at least

one facilitator that leads the group discussion. Regarding participants, a cer-

tain degree of homogeneity among the group members is necessary in the

early recovery stages. This homogeneity allows the facilitator to structure

the program to the specific needs of each participant. In contrast, during the

later stages of group interventions, participants may even benefit from a

degree of heterogeneity in the composition of the groups (e.g., Fritch &

Linch, 2008).

In terms of the structure of the intervention programs and strategies, the

literature provides considerable variability of program guidelines. Fleming

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

6 Small Group Research

(1979) recommended the simultaneous use of didactic techniques (e.g., bib-

liotherapy), training skills (e.g., role-playing, relaxation), and less structured

intervention activities, such as group discussions or venting anger sessions.

Meanwhile, Cox and Stoltenberg (1991) propose a structure of five modules,

integrating several techniques: (a) cognitive therapy, oriented to improve

women’s self-concept about their relational skills and their preparation for

work; and (b) assertiveness and communication skills to recognize their

rights and practicing self-defense skills. Seeing that the victim’s assertive-

ness may increase the risk of aggression, this module can also include (a)

safety skills, such as identifying signs of abuse, developing escape plans and

training emotional self-control; (b) problem-solving involving questions

about the definition of the problem, the production of alternative answers,

decision making, and verifying the adequacy of those decisions; (c) voca-

tional counseling and job search training; and finally (d) awareness of self

and body, encouraging women to discuss issues related to self-image, par-

ticularly in terms of physical image. In the implementation of these programs

a variety of strategies are used, including group discussions, teaching strate-

gies, and techniques involving cognitive restructuring. However, despite

multiple recommendations regarding group intervention, this method is not

immune to criticism. In fact, research on the outcomes of group therapy with

women reveals some significant methodological limitations. Limitations and

controversies underlying group intervention include the scarcity of published

studies about intervention results, small sizes ranging from 12 (Holiman &

Schilit, 1991) to 21 participants (Cox & Stoltenberg, 1991), and a lack of

control groups and follow-up assessment. This study hopes to address some

of these limitations and highlights the benefits of group intervention.

Specifically, this study aims to provide initial evidence of the effectiveness of

group intervention with female victims of intimate violence (e.g., Tutty &

Rothery, 2002; Matos & Machado, 2011).

Study Context

In Portugal, community services and formal help-sources are available to

female victims of IPV. These include both professional services (e.g., judi-

cial, criminal, medical) and social support organizations, such as agencies for

victims’ support and shelters. However, these answers are predominantly

based on crisis intervention as a first response and an individual intervention

in the support agencies. Although shelters or support agencies sometimes

offer group intervention, it is often unsystematic and fail to assess the effec-

tiveness of the intervention. Taking into account the limited availability of

psychological interventions for female victims of IPV in Portugal, along with

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

Santos et al. 7

lacking empirical evidence of intervention efficacy, a group intervention pro-

posal with female victims of IPV was designed, implemented, and evaluated

in Portuguese public institutions. Furthermore, the longitudinal assessment

allows the efficiency regarding each woman to be identified and to determine

whether the changes achieved are sustained over time.

This study has three primary research goals. First, this study will assess

the effectiveness of a group intervention with female victims of IPV. Second,

the study aims to understand the amplitude of change and its main domains

(e.g., clinical symptoms, level of social support, and personal and social

skills) throughout the intervention process. Finally, this study is unique in

that will evaluate whether the evidenced changes were maintained after the

end of group intervention by taking a longitudinal approach. Overall, we

hypothesize that women who participated in the treatment group would dem-

onstrate statistically significant differences on outcomes measured at post-

intervention when compared with their own pre-intervention scores and that

gains would be maintained in the follow-up.

Method

Participants

The study was conducted with a convenience sample of 23 female victims of

IPV. Participants were gathered based on inclusion criteria, namely, being a

victim of IPV or having left an abusive relation recently (within the last 12

months). Exclusion criteria included clinical diagnosis of a personality disor-

der, severe depressive disorder with suicidal thoughts and/or attempts, psy-

chotic symptoms, and/or substance abuse. Prior to joining the intervention

group, women were individually interviewed and assessed to serve as a

screening process. An initial assessment of clinical symptoms was made with

the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV disorders–Axis I (SCID-I;

First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002), which covers the disorders diag-

nosed by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.;

DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and allows the diagnosis

to be identified. From a total of 36 female victims assessed, 10 were excluded

because they did not match the inclusion criteria (e.g., they had left the abu-

sive partner more than 12 months prior to intake assessment) and three were

redirected to an individual intervention because their primary turmoil was

due to issues that were unrelated to domestic violence (e.g., abusive behavior

of their children). When screening participants, an assessment was created to

assess whether group intervention was the best response for these women.

Only in this case were the women selected to enter the group. Moreover, if at

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

8 Small Group Research

the end of the group intervention any participant demonstrated clinical symp-

tomatology that required further psychological intervention, other help alter-

natives were discussed with them.

Twenty-three women participated in one of three intervention groups (first

group, n = 8; second group, n = 8; third group, n = 7). All participants com-

pleted the intervention program, and there were no dropouts. The women’s

age ranged between 26 and 52 years (M = 38.33, SD = 6.86), they were pre-

dominantly divorced from (34.8%) or married to (30.4%) the perpetrator, and

had between one and four children (M = 1.87, SD = 0.81). In terms of national-

ity, most participants were Portuguese (87%), one was Brazilian (4.3%), and

two were from African countries (8.7%), although all were native Portuguese

speakers. With regard to their academic qualifications, most had completed

primary education (fourth grade, 21.7%; sixth grade, 21.7%; ninth grade,

21.7%). Finally, 60.9% of the participants were unemployed while the remain-

der had a wide variety of jobs, ranging from unskilled to skilled occupations.

At intake and at the end of the intervention, the majority of women (82.6%)

were no longer in the abusive relationship. However, the duration of the abu-

sive relationships ranged from 2 to 35 years (M = 16.74, SD = 8.39). Twenty

(87%) participants were subjected to prolonged victimization (more than 5

years) and only three (13%) had ceased victimization sooner (less than 5

years). Six of the participants lived in shelters (26.1%), three (13%) were liv-

ing with the abusive partner/husband, two were living with their daughters

(8.7%), and the remaining participants (52.2%) lived alone. Psychological

violence was present in all cases. Four women were simultaneously victims

of physical, psychological, and sexual abuse (17.4%) and 15 participants

were victims of physical and psychological violence (65.2%). Table 1 dis-

plays a sociodemographic characterization of the participants. All partici-

pants had pressed charges for domestic violence.

Measures

Clinical symptoms. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, &

Brown, 1996, adapted by Coelho, Martins, & Barros, 2002) and OQ-45 (Out-

come Questionnaire—Lambert et al., 1996, adapted by Machado & Klein,

2006) were used in the assessment of clinical psychological symptoms.

The BDI-II is a self-report instrument consisting of 21 items. Respondents

select from four or five evaluative statements ranked from neutral (0) to

severe (3) to describe how they felt in the prior week (e.g., mood, sense of

failure, social withdrawal). This instrument allowed the diagnosis of minimal

symptoms (score 0 to 13), mild depression (14 to19), moderate depression

(20 to 28), and severe depression (29 to 63). This appears to be a reliable test,

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

Santos et al. 9

Table 1. Sociodemographics of the participants.

Sociodemographic characteristics M SD

Age 38.33 6.8

Number of children 1.87 0.8

Duration of the relationship (years) 16.74 8.4

n %

Nationality

Portugal 20 87.0

Brazil 1 4.3

African country 2 8.7

Marital Status

Single 2 8.7

Married 7 30.4

Unmarried partner 2 8.7

Divorced 8 34.8

Separated 4 17.4

Educational level

No literacy 1 4.3

Fourth grade 5 21.7

Sixth grade 5 21.7

Ninth grade 5 21.7

12th grade 3 13

Graduation 4 17.4

Employment status

Unemployed 14 60.9

Employed 9 39.1

Relationship status

Out of the relationship 19 82.6

In the relationship 4 17.4

Type of violence suffered

Psychological 3 13

Psychological and physical 15 65.2

Physical and sexual 1 4.3

All types 4 17.4

Length of exposure to violence

Continued (> 5 years) 20 87

Non-continued (< 5 years) 3 13

Living conditions

Shelters 6 26.1

With abusive partner 3 13

With children 2 8.7

Alone 12 52.2

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

10 Small Group Research

revealing a high internal consistency (α = 0.89). In this sample, an internal

consistency score of .92 was found at pre-test for this scale.

In terms of the improvement of clinical symptoms, the Reliability Change

Index (RCI) was used to compute individual clinical significance, using the

outcomes of pre- and post-test assessment. A reliable change, as proposed by

Seggar, Lambert, and Hansen (2002) is achieved when there is a difference of

8.46 points between two assessment events.

Regarding OQ-45, this instrument is a general measure of wellness or

psychological discomfort. It has 45 items, from which a 5-point Likert-type

scale can be answered: never, rarely, sometimes, often, and always. It evalu-

ates the following subscales: Subjective Discomfort, Interpersonal

Relationships, and Social Role Performance. The total score can range from

0 to 180. Any individual whose total score lies between 0 and 62 reveals no

relevant clinical symptomatology. The questionnaire has high internal con-

sistency (α = .93) and good test–retest reliability (α = .84; Lambert et al.,

1996). The Portuguese version, adapted by Machado and Klein (2006), has

good internal consistency (α = .89; Machado & Fassnacht, 2014). A clinical

significant change from OQ-45 is achieved when there is a difference higher

than 15 points between two assessments. The internal consistency for this

sample was .87 for the pre-test.

Victimization perpetrated by the partner. The Marital Violence Inventory

(Inventário de Violência Conjugal [IVC]; Machado, Matos, & Gonçalves,

2007) aims to identify victimization and/or perpetration of abusive behavior

in marriage or similar relationships. It consists of 21 items, which involve

physically abusive behaviors (e.g., kicking, slapping), emotionally abusive

behaviors (e.g., insult or slur), and coercion/intimidation behaviors (e.g.,

avoiding contact with other people, breaking things to cause fear). For each

of the behaviors listed in Part A of the inventory, the subject is asked whether,

during the past year (a) he or she adopted those practices in the context of his

or her current affective relationship; and (b) their current partner adopted

those practices. If the answer to any of these questions is yes, the subject is

asked whether that behavior occurred just once or more than once. In this

sample, the internal consistency was .61 for victimizations and .98 for perpe-

tration of violence, at pre-test.

IPV beliefs. The Scale of Beliefs About Marital Violence (Escala de Crenças

sobre a Violência Conjugal [ECVC]; Machado et al., 2007) was used to eval-

uate participants’ beliefs about IPV. This scale has 25 items, which consist in

statements that refer to marital violence legitimacy. Participants’ answer in a

Likert-type scale from 1 to 5 (totally disagree to totally agree). This range

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

Santos et al. 11

reflects a high degree of internal consistency (α = 0.90), and previous studies

have demonstrated a strong positive association between acts of aggression

by the partner and the overall score on the scale. This scale also explains 56%

of the four-factor score. The factors are (a) legitimizing and trivialization of

minor violence, (b) legitimization of violence by the woman’s conduct, (c)

legitimization of violence by its attribution to external causes, and (d) legiti-

mization of violence by the preservation of family privacy. The total score is

obtained by calculating the sum of direct responses to each item. The score

for each factor can also be calculated by summing item responses. Total score

had an internal consistency of .954 for this sample at pre-test.

Social support. The Scale of Satisfaction with Social Support (Escala de Sat-

isfação com o Suporte Social [ESSS], Ribeiro, 1999) consists of 15 items

over four dimensions or factors: satisfaction with friends (five items), inti-

macy (four items), family satisfaction (three items), and social activities

(three items). Items are organized in a Likert-type scale from 1 to 4 (totally

disagree to totally agree). Cronbach’s alpha of the total scale is .85, and the

overall load factor of items of ESSS is high (above 50%). The total score is

the sum of all items. The score for each dimension is the sum of items in each

scale or subscale. The result for the total scale can vary between 15 and 75,

and the highest scores correspond to a greater perception of social support. In

this sample, an internal consistency of .88 was found at pre-test.

Self-esteem. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1965,

adapted by Santos & Maia, 2003) is a 10-item Likert-type self-rating measure

of global assessment of self-esteem. There are four alternative responses

from 1 to 4 (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree). Five items

tend toward the positive and five toward the negative; total scores range from

10 to 40, with higher results showing higher levels of self-esteem. This scale

shows good levels of internal consistency, measured by Cronbach’s alpha,

with mean values situated, in most cases, above .80. In the current study,

internal consistency was .92, at the pre-test.

Procedures

Participants were recruited through several means of referral: social work

and health institutions, safety agencies, and all institutions that specialize in

providing support regarding this social issue in the northern region of Portugal

(e.g., non-governmental organizations). After requesting their collaboration,

the program was publicized through letters, flyers, public presentations, press

releases, and through the media. Those that participated in the study came

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

12 Small Group Research

from treatment referrals by a shelter (n = 6), or victim support agencies (n =

14); some came on their own initiative (n = 3). These last women were self-

identified victims, and were prescreened to evaluate victimization status and

type of violence experienced. The advertisement and recruitment process

took place during 3 months.

In the initial assessment, all of the procedures were explained to the par-

ticipants. Women were informed about the confidentiality of the data col-

lected, and all of them signed an informed consent statement, which contained

the study objectives and main rules of the intervention program. Participation

was voluntary and the intervention was implemented free of charge.

The research design was based on a psychological assessments protocol

that included a pre-test (at the beginning of the intervention), post-test (after

the end of the intervention), and follow-up (3 months after the end). Women

filled out questionnaires on their own for all of the assessment events. The

intervention took place in Portuguese public institutions in the cities of Braga

and Oporto (North of Portugal).

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted by means of inferential statistical testing, with

an intrasubject design to compare the three assessment events. Parametric

tests (one-way ANOVA) were computed when variables had a normal distri-

bution, and non-parametric tests (Friedman test and Wilcoxon’s test, with

Bonferroni correction) were used when variables did not meet the assump-

tion of normal distribution. The calculation of the effect sizes was made

through the η2 (eta square) for ANOVA, and the Kendall’s W (Kendall’s coef-

ficient of concordance) for Friedman. The p value assumed was .05, with the

exception of the Bonferroni correction used with p < .017. Statistical testing

was computed with SPSS-IBM® (Statistical Package for Social Sciences,

Version 21) statistical software.

Description of the Group Intervention Program

The group intervention program for female victims of IPV, with a cogni-

tive-behavioral orientation, was implemented in public institutions over

the course of eight weekly sessions of 90 min each, under the acronym

GAM (Grupos de Ajuda Mútua; Mutual Help Groups). The program aimed

to reduce re-victimization, reduce the clinical effects of victimization, and

promote social and personal skills. Two facilitators conducted the ses-

sions, with prior training in cognitive-behavioral therapy and experience

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

Santos et al. 13

in psychotherapy with victims. Each session was divided into four parts,

starting with a brief review of the content of the previous session, proceed-

ing to questions and concerns of the subjects, objectives for the current

session, and ending with a summary of the session. In general, the inter-

vention goals were to (a) decrease victimization and to reduce tolerance

toward IPV; (b) reduce clinical symptoms; (c) help reduce social isolation;

(d) promote empowerment and social abilities; (e) promote alternative

ways of communication with the partner; and (f) develop new life projects.

To achieve the objectives, different strategies were implemented, such as

psychoeducation, relaxation techniques, cognitive restructuring, self-instruc-

tions, decision-making, problem-solving, assertiveness, and communication

skills training. Participants trained new abilities by role-play, case study visual-

ization, debate from videos and educational games, and brainstorming. Table 2

summarizes each session name, objectives, and key achievements for partici-

pants. The group intervention program had three main phases. The first

phase focused on the identification and comprehension of the phenomenon

and comprised three sessions. There were three primary goals during phase

one. First, participants were taught to understand the concept of IPV and its

impact (e.g., fear, sadness). The second aim of Phase 1 was to teach the

women how to understand the individual characteristics of the victim and

the abusive partner who supports the abuse, with the ultimate goal of clari-

fying that the only person responsible for the violence was the perpetrator.

Phase 1 concluded by working to identify cultural and social requirements

that legitimize violence against women (e.g., patriarchy, criticism of women

who leave relationships). The second phase included Sessions 4, 5, and 6

and relied on developing personal and social skills (e.g., self-esteem, asser-

tiveness, decision making). The final sessions (7 and 8) were, respectively,

about the prevention of violence in future relationships and the consolida-

tion of the gains achieved. Intervention was performed by four psycholo-

gists who constituted the team of facilitators; each had expertise in IPV and

master’s and/or PhD in psychology. Throughout all the stages of treatment,

individual needs of participants were addressed, as the group leaders were

looking for signs that other types of intervention could be needed.

The development and the dynamics of group intervention were evaluated

by means of a qualitative survey of the participants after the end of the inter-

vention. The main results (Matos, Santos, & Cunha, 2016) indicated the

women’s positive experience in the appropriate environment, satisfaction

with the activities, the facilitators, and the peers. They also pinpointed the

achievement of well-being and social support, as well as increased knowl-

edge about IPV dynamics. They also reported attitudinal change, specifically

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

14 Small Group Research

Table 2. Structure and Goals of Group Intervention Program.

Session name Session goals Key achievements

1. Participants Create a warm and safe The group as a space to share

and facilitators environment common experiences

presentation Promote a sense of The group as space of help and

belonging and group mutual learning

cohesion The group as a space with rights

Define rules and and duties

objectives of the group

Evaluate the expectations

of the participants with

the group

2. Grasp of the Define the different forms The definition of domestic

dynamics of of violence violence and the identification

violence Know the dynamics of of its forms

maintenance of victims The identification of the

in abusive relationships difficulties, challenges and

Identify the consequences meanings of IPV

of violence in women The identification of the

and their children, in the consequences of IPV to the

short and long term victims and their children

The recognition of the

strategies of power and

control used by the abusive

partner to keep the woman in

a relationship

To define that the origin and

maintenance of the violence

are of the sole responsibility

of the aggressor

3. News about Deconstruct the myths Deconstruction of the current

violence about violence cultural and social discourse

Identify and analyze the about the women’s role in

cultural discourses various areas of life and the

relating to marriage and impact that this discourse

the role of men and has in maintaining women in

women in the family violent relationships

and society Construction of alternative

Build alternative discourses and positions

discourses compared to be taken by women

to traditional to change the current

performances of mainstreaming

gender

(continued)

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

Santos et al. 15

Table 2. (Continued)

Session name Session goals Key achievements

4. Emotional Promote emotional There are common inadequate

coping differentiation (e.g., feelings that prevent

learned discouragement, the action of those who

guilt, anger) experience this problem

Modify maladaptive These same feelings can be

emotions managed and replaced by

Learn how to deal more appropriate feelings

adaptively with negative Formulation of alternative

emotions beliefs and thoughts

The importance of relaxing and

taking time for herself

5. Communication Recognize the assertive Recognition that talking is

skills style of interpersonal different from communicating

communication as the with someone

most appropriate and Advantages of being assertive

effective Importance of non-verbal

Promote assertive communication

communication Recognition of their rights

Knowledge of how to react in

different situations without

disrespecting others, but

without disrespecting herself

6. Self-esteem Develop self and hetero Importance of self-knowledge

knowledge and self-esteem for personal

Raise awareness of the well-being

role of self-esteem Importance of self-knowledge

Promote self-esteem and self-esteem in relational

and personal performance

7. Prevention of Distinguish the Warning signs of abusive

violence and characteristics of violent relationships

re-victimization relationships versus Base characteristics of healthy

healthy relationships relationships

Promote the ability of

decision making

Teach participants problem-

solving strategies

8. Back to the Reflect and share feelings Summary and consolidation of

future and thoughts about the all the lessons learned

group Importance of the group’s

Summarize the gains and goodbye but, above all, of

learned skills holding onto the support

network created in the group

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence.

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

16 Small Group Research

Table 3. Means, Standard Deviations, and ANOVA Repeated Measures for

Clinical Measures.

Pre-test Post-test Follow-up ANOVA

M SD M SD M SD F df p ηp2

Beck Depressive Inventory-II

Total score 19.43 11.5 9.65 9.27 12.23 10.65 13.17 2,42 <.001 .39

Outcome Questionnaire–45

Total score 71.83 19.47 53.74 21.74 57.82 25.68 13.31 a 2,28 <.001 .39

Symptom 43.26 11.85 32.13 13.88 33.95 16.23 9.6a 2,31 .002 .31

distress

Interpersonal 17.70 6.20 13.48 6.30 13.59 8.16 6.47 2,42 .004 .24

relations

Social role 9.52 3.96 7.39 4.34 8.45 3.57 2,37 2,42 ns

aGreenhouse-Geisser adjustment was used to correct for violations of sphericity.

about the responsibility of the perpetrator and less tolerance toward violence.

Social skills and coping strategies were enhanced.

The “Results” section is divided into clinical symptoms, main results, violent

behaviors and beliefs, and other measures. These domains are analyzed by

comparing the three assessments made during the pre-test, post-test, and

follow-up.

Clinical Symptoms

Depressive symptoms, assessed by the BDI-II (Beck et al., 1996; adapted by

Coelho et al., 2002), showed a significant decrease as the intervention evolved.

Women seemed to change from mild depression in the pre-test, to minimal

symptoms in post-test and follow-up, in a statistically significant way, F(2,

42) = 13.17, p < .001, with a moderate effect size value (see Table 3). Pairwise

comparisons of Bonferroni were computed, showing that depressive symp-

toms significantly decreased from pre- to post-test (p = .001), and from pre-

test to follow-up test (p = .004), maintaining the gains from post-test to

follow-up after 3 months. In addition, from pre-test to post-test, there was a

clinical significant change, as assessed by the RCI. In this way, participants

seemed to fully recover from depressive symptoms by the end of group

intervention.

The OQ-45 (Lambert et al., 1996; adapted by Machado & Klein, 2006) data

showed that general clinical symptoms evolved from a clinical-relevant condi-

tion at pre-test to one of no clinical relevance in post-test. In these assessments,

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

Santos et al. 17

Table 4. Means, Standard Deviations, and Friedman Repeated Measures for Scale

of Beliefs About Marital Violence.

Pre-test Post-test Follow-up Friedman

M SD M SD M SD χ2(2) p W

Total score 45.43 17.62 39.91 13.63 37.59 13.64 12.54 .003 .285

Legitimation and banalization of 16.74 7.20 15.30 4.99 14.86 4.63 10.19 .006 .242

small violence

Legitimation of violence by 17.83 6.90 15.91 5.72 14.64 5.70 11.31 .004 .257

attribution to women’s

behavior

Legitimation of violence by 20.70 8.24 16.61 5.98 16.95 7.04 12.78 .002 .290

attribution to external causes

Legitimation of violence through 6.57 2.89 6.13 2.49 5.43 1.60 9.5 .009 .226

preservation of the intimate

family life

there was a reliable change, as suggested by RCI, reflecting a full recovery

from clinical symptoms by the participants. Gains were maintained at follow-

up assessment. Statistically significant differences were found throughout the

assessment events, Greenhouse-Geisser corrected, F(2, 28) = 13.31, p < .001,

with a moderate effect size (see Table 3). Results from pairwise comparisons of

Bonferroni showed that the decrease of clinical symptoms from pre-test to

post-test (p < .001) and follow-up (p = .016) events were statistically signifi-

cant. With regard to OQ-45 subscales, there was a general decrease from pre-

test to post-test, and maintained levels from post-test to follow-up, in terms of

mean values (Table 3). Subscales of symptom distress and interpersonal rela-

tions, which had values above the clinical cutoff score for the Portuguese popu-

lation, showed significant differences among the three assessment events.

Symptom distress showed statistically significant differences between pre-test

and post-test (p = .004). However, the interpersonal relations subscale pre-

sented statistically significant differences between pre-test and post-test (p =

.002), since the value at pre-test had no clinical relevance.

Violence Beliefs and Behaviors

This section examines how the intervention affected violence beliefs and

behaviors of the participants. From the Scale of Beliefs About Marital Violence

(Machado et al., 2007), data in the pre-test showed a global score of low toler-

ance to violence (see Table 4). This means that participants had a general ten-

dency to disagree with traditional beliefs about violence. However, the

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

18 Small Group Research

Table 5. Means, Standard Deviations, and Friedman Repeated Measures for

Marital Violence Inventory.

Pre-test Post-test Follow-up Friedman

M SD M SD M SD χ2(2) p W

Victimization 23.68 13.33 1.43 2.74 6.56 12.17 16.98 < .01 .566

Perpetration 3.29 4.98 0.09 0.42 0.31 0.70 11.53 .003 .384

intervention assisted participants to create beliefs more aligned with traditional

views of violence. Participant scores decreased, χ2(2) = 12.54, p = .003, as the

group process progressed toward the end. Kendall’s W indicated fairly strong

differences among the three events. According to Wilcoxon’s tests for paired

samples with the Bonferroni correction, total score reduced significantly from

pre-test to follow-up (p = .003). In regard to the questionnaire subscales, Factor

3, legitimization of violence by attribution to external causes, also reduced sig-

nificantly from pre-test to post-test (p = .004), and from pre-test to follow-up

(p = .012). Factor 4, legitimization of violence through preservation of the inti-

mate family life, showed statistical differences from the post-test to the follow-

up event (p = .012), as these types of beliefs reduced dramatically after group

intervention ended. Factor 1, legitimization and trivialization of small violence,

and Factor 2, legitimization of violence by attribution to women’s behavior,

also were reduced, but not at a statistically significant level.

Data from Marital Violence Inventory (IVC; Machado et al., 2007; see

Table 5) showed a clear prevalence of received victimization at intake. It

stated that violence in these couples was mainly perpetrated by men. Just a

small amount of violent behaviors were perpetrated by women against their

partners. These behaviors were understood, taking into consideration their

type and low prevalence, as reactive behaviors. In the post-test, there was a

clear decrease (p < .001) of the received behaviors, which translated into a

reduction of types of violent behaviors, frequency, and severity, that contin-

ued to decrease from pre-test to follow-up (p = .011), computing Wilcoxon’s

tests for paired samples with correction of Bonferroni. Perpetration also

dropped (p = .003) to near absence (M = .09), and continued to decrease from

pre-test to follow-up (p = .013), as computed by Wilcoxon’s tests for paired

samples with correction of Bonferroni.

Other Measures

Total scores from RSES (Rosenberg, 1965; adapted by Santos & Maia, 2000)

revealed that, at intake, women showed a medium level of self-esteem, which

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

Santos et al. 19

Table 6. Means, Standard Deviations, and ANOVA Repeated Measures for

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale.

Pre-test Post-test Follow-up ANOVA

M SD M SD M SD F df p ηp2

24.86 7.23 30.27 5.57 31.18 4.82 12.19a 1,30 <. 001 .37

aGreenhouse-Geisser adjustment was used to correct for violations of sphericity.

Table 7. Means, Standard Deviations and ANOVA Repeated Measures for Scale

of Satisfaction With Social Support.

Pre-test Post-test Follow-up ANOVA

M SD M SD M SD F df p ηp2

Total score 43.09 13.25 50.05 11.04 50.18 17.57 4.12a 2,32 .034 .17

Friendship 14.50 5.79 18.00 4.43 17.05 6.31 6.12 2,42 .005 .23

Intimacy 11.64 4.57 13.23 3.75 13.82 5.56 2.55 2,42 ns

Family 10.18 3.7 10.82 3.54 10.64 4.01 .403a 1,30 ns

Social activities 6.88 3.21 7.91 3.21 8.68 3.36 2.23 1,31 ns

aGreenhouse-Geisser adjustment was used to correct for violations of sphericity.

increased at post-test and was maintained at follow-up. The differences from

pre-test to post-test and follow-up are statistically significant, Greenhouse-

Geisser corrected, F(1, 30) = 12.19, p < .001 (see Table 6). Pairwise compari-

sons of Bonferroni were computed, showing statistically significant differences

from pre-test to post-test (p = .002) and from pre-test to follow-up (p < .001).

The total score according to the Social Support Satisfaction Scale (ESSS;

Ribeiro, 1999) indicated a decrease from pre- to post-test while maintaining

gains in follow-up at a statistically significant level, Greenhouse-Geisser cor-

rected, F(2, 32) = 4.12, p = .034 (see Table 7). Pairwise comparisons were

computed, showing no statistical significant differences between assessment

events, with the adjustments of Bonferroni. Among the subscales, the one

related to friendship is the one with the highest scores, meaning that partici-

pants perceive friends as an effective form of social support. Scores on this

subscale increased from pre-test to post-test (p = .001).

Discussion

This study examined the effectiveness of a group intervention program of

female victims of IPV in a relatively brief (eight sessions) group format.

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

20 Small Group Research

The main conclusion reveals that the intervention created effective out-

comes, as other studies had already observed (e.g., Briere & Jordan, 2004;

Coker et al., 2002; Constantino et al., 2005; Iverson et al., 2009; Lundy &

Grossman, 2001). At intake, women invited to participate in the interven-

tion presented clinical levels of symptomatology, and at the conclusion of

the group intervention, the women’s main symptoms were reduced in sever-

ity and intensity; the indexes of clinical significance of the intervention

were highly satisfactory. Thus, important and significant improvements in

depressive and general symptoms were achieved, as well as in women’s

self-esteem, social support, and tolerance for intimate violence. Furthermore,

improvements were consolidated and increased over time. These results

provide evidence that the design of the intervention met the demands and

needs of female victims of IPV, improving their psychological well-being.

Initial results showed high scores for depressive symptoms dominance in

female victims, along with general relevant symptoms. As intervention

evolved, the depressive symptoms decreased until the absence of depressive

symptoms in the end of the intervention. Regarding the general symptoms,

the path was similar. Women also evolved from a condition with clinical

symptoms to a condition of symptoms without clinical relevance at the end of

intervention. However, regarding the subscales of the measure used, the sub-

scale of social role did not decrease significantly. This might mean that

women still view themselves as dissatisfied or in conflict with their social

roles, family life, leisure, and work. It worth noting that some of them are

living in shelters and not able to perform these socially expected roles, or this

aspect of their lives was still affected by psychological problems (Lambert

et al., 1996). The absence of a control group prevents further discussion

regarding the prevention of severe mental health issues in women IPV.

However, group intervention seemed to be effective in reducing clinical

symptoms from pre-test to post-test, and gains were upheld at follow-up

assessment. Tutty, Bidgood, and Rothery (1996) found, in a follow-up assess-

ment 3 months after an intervention program in shelters, that women living

independently improved their assessment of support and self-esteem. The rat-

ers’ assessment was also very positive for the same variables and also for

coping abilities and safety. These results are very similar to several research

studies on group intervention that address clinical symptoms (cf. McBride,

2001; Constantino et al., 2005; Schwartz et al., 2004). These studies, com-

bined with the results of this study, emphasize the potential positive impact of

group intervention for female victims.

Generally, tolerance toward the use of violence in intimate relationships

decreased in the participants. Although that is not always an assessed dimen-

sion, some studies revealed a similar tendency (Rinfret-Raynor & Cantin,

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

Santos et al. 21

1993; Tutty et al., 1993). Sessions that allowed participants to reflect on partner

responsibility in the violence and myths about IPV might have contributed to

this decrease. However, violence tolerating beliefs do not seem to characterize

these women, due to the low score obtained at the beginning of the interven-

tion. This outcome brings to question whether females who have a low toler-

ance for violence were more likely to self select to participate in the intervention.

As the women had already realized that they could not tolerate violence, they

may have been more willing to enter group intervention, as a prior drive toward

change. Nevertheless, at the end of the group intervention, these beliefs changed

and women became even less tolerant to violent behaviors.

The group intervention also seemed to contribute to a decrease of violence

suffered by female victims and also perpetrated by women. The group ses-

sions as a whole might have contributed toward women holding the offender

responsible for their abusive behavior and also toward expanding the role of

strategies that women would usually adopt. Therefore, with the women’s par-

ticipation in the group, they seem to be better prepared to handle the violent

behaviors from their partners, and to control and defend themselves without

the use of violence. Other studies under a group format revealed a decrease

on violence suffered by women (e.g., McBride, 2001; Rinfret-Raynor &

Cantin, 1993; Tutty et al., 1993).

Self-esteem is commonly assessed in group effectiveness studies. In this

study, it revealed significant improvement, as the group intervention focused

on women’s empowerment and social reinforcement throughout the sessions.

At intake, self-esteem levels were not very low, which may be due to fact that

the majority of the participants were no longer in the abusive relationship.

Even with the initial moderate self-esteem scores, participation in the group

increased self-esteem levels significantly. Results from literature made this

result expectable, as an increase of self-esteem of women is a sustained

achievement following group treatments (e.g., Cox & Stoltenberg, 1991;

Rinfret-Raynor & Cantin, 1993; Tutty et al., 1993).

Some authors have found an increase in the perception of social support in

female victims involved in group intervention (cf. Constantino et al., 2005;

Tutty et al., 1993). Coherently, results showed that social support improved

total score and friendship levels. This subscale improvement might have been

promoted by the group experience and relationships that started in the inter-

vention. In fact, during the sessions, women started to form friendships and

to arrange get-togethers outside the scope of the group, which might explain

the higher score obtained in the subscale of friendship.

In summary, data reveal encouraging results achieved by women who ben-

efit from the program. Data showed that women evolved to a condition of

well-being characterized by no clinical symptoms, low tolerance to violence,

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

22 Small Group Research

sense of self-esteem, ability to seek social support, and no violence in their

lives. These results provide evidence that the developed group intervention

program is effective. A closer examination of data shows that although gains

were maintained at follow-up, total scores showed slight increases. This raises

the question of the time frame needed to bring about psychological changes

and also for these to endure over time. Although the literature omits this

aspect, we propose that intervention groups could be followed by booster ses-

sions. Also noteworthy is the fact that these programs are an economical and

effective way to raise women’s awareness regarding choosing risky partners

or situations (Iverson et al., 2011). In addition, clinical levels of symptomatol-

ogy revealed by women at intake may also interfere with their ability to pick

safe partners or to terminate an abusive relationship (Iverson et al., 2011).

This research addressed some concerns about intervention with battered

women also addressed by Abel (2000). The intervention was conducted

according to a specific theoretical framework and structured explicit treat-

ment process, which might contribute to the clients’ positive outcomes.

Along with treatment integrity, an effort was also made to make the assess-

ment protocol explicit and adequate. An interesting indicator of the treat-

ment’s adequacy was the inexistence of dropouts. Efforts were made to

develop a specific program tailored to the Portuguese context, and to per-

form an adequate assessment of its effectiveness, and disseminate the results.

A frequently described design limitation was surpassed by the inclusion of

the follow-up assessment. As Abel (2000) stated, “The ability to conduct

follow-up research on the women who participate in practice effectiveness

research is essential to increasing our confidence in the intervention effec-

tiveness” (p. 74). In future studies, it will be important to include follow-up

assessments during a period of, at least, 12 months. An additional contribu-

tion of this study is that it provided IPV female victims with treatment from

qualified workers who have experience with IPV victims.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the declared success of this intervention study, there are some limita-

tions that must be acknowledged. The first limitation is the small sample size,

which does not allow robust analyses and limits the generalizability of the

findings. Second, we rely only on self-report data. Both of these limitations

seem to be practically endemic in this field. In a prior literature research,

Matos, Machado, Santos, and Machado (2012) found that convenience sam-

ples are used in effectiveness research because women seek secure settings

and their problems need to take their security and confidentiality into account.

Random selection of participants would be a rather difficult task; however,

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

Santos et al. 23

future studies should use larger sample sizes and introduce new measures to

evaluate the changes of women.

In addition, this study does not include a control group, as it is considered

that is not ethical to have a waiting list, bearing in mind the needs of victim-

ized women. The change assessment was made taking in consideration the

differences between assessment events. Nevertheless, it is not taken for

granted that treatment gains were indeed a reflex of the group intervention.

They might be due to other factors, for instance, group cohesion, or even

some characteristics of the participants (e.g., not being in an abusive relation-

ship during intervention; institutional reference).

Finally, although there were statistically significant changes on some mea-

sures from pre-test to post-test and to follow-up, some of the women were still

facing clinical rates of symptomatology. It is possible that some women may

have benefited from additional treatment or that this format does not always

answer all the individual needs of its members. Although a longer program

might be favorable for some, it would use more resources and time, which

could jeopardize the women’s commitment to the group. Future research

should evaluate shorter versus longer programs to define optimal length of the

intervention. Also, a longer follow-up period would be important to fully

assess the impact of treatment on long-term risk for IPV victimization.

Nonetheless, despite the brevity of the group interventions, the extent of

change is encouraging. Another aspect worth taking into consideration in

future studies would be to evaluate the process of change through Innovative

Moments Coding System, as it was used in previous studies in individual

therapy (cf. Gonçalves, Matos, & Santos, 2009). Also, it would be important

to assess the women’s readiness to change, through the assessment of, for

instance, the stage of change prior entering the treatment (e.g., transtheoreti-

cal model from Prochaska & DiClemente, 1982).

In conclusion, the results from this study are promising regarding the

effectiveness of group intervention as a response for female victims of IPV.

Findings suggest that the current intervention has positive impact on female

victims of IPV, so more research investment in this area would be needed to

address women’s psychological well-being.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research,

authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research,

authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was partially conducted at

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

24 Small Group Research

Psychology Research Centre (UID/PSI/01662/2013), University of Minho, and sup-

ported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology and the Portuguese

Ministry of Education and Science through national funds and co-financed by FEDER

through COMPETE2020 under the PT2020 Partnership Agreement (POCI-01-0145-

FEDER-007653). Additional support was provided by the Commission for Citizenship

and Gender Equality (CIG) and the Presidency of the Council of Ministers (Portugal).

References

Abel, E. M. (2000). Psychosocial treatments for battered women: A review of empiri-

cal research. Research on Social Work Practice, 10, 55-77. Retrieved from http://

firstcontent.oclc.org/ECOPDFS/SAGEPUBL/B0497315/R10S1W5.PDF.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of men-

tal disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). BDI-2-Beck Depression Inventory.

San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Bennett, L., Riger, S., Schewe, P., Howard, A., & Wasco, S. (2004). Effectiveness of

hotline, advocacy, counseling, and shelter services for victims of domestic vio-

lence: A statewide evaluation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19, 815-829.

doi:10.1177/0886260504265687

Breiding, M. J., Chen, J., & Black, M. C. (2014). Intimate partner violence in the

United States—2010. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and

Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from http://www.

cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/cdc_nisvs_ipv_report_2013_v17_single_a.pdf

Briere, J., & Jordan, C. (2004). Violence against women: Outcome complexity and

implications for assessment and treatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19,

1252-1276. doi:10.1177/0886260504269682

Coelho, R., Martins, A., & Barros, H. (2002). Clinical profiles relating gen-

der and depressive symptoms among adolescents ascertained by the Beck

Depression Inventory II. European Psychiatry, 17, 222-226. doi:10.1016/S0924-

9338(02)00663-6

Coker, A. L., Davis, K. E., Arias, I., Desai, S., Sanderson, M., Brandt, H. M., &

Smith, P. (2002). Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence

for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23, 260-268.

doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00514-7

Commission for Citizenship and Gender Equality—Presidency of the Council of

Ministers. (2014). National Plans 2014-2017. Retrieved from http://www.cig.

gov.pt/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/CIG-VPNPCVDG_2014-2017_ENG.pdf

Constantino, R., Kim, Y., & Crane, P. (2005). Effects of a social support intervention

on health outcomes in residents of a domestic violence shelter: A pilot study.

Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 26, 575-590. doi:10.1080/01612840590959416

Cox, J. W., & Stoltenberg, C. D. (1991). Evaluation of a treatment program for bat-

tered wives. Journal of Family Violence, 6, 395-403. doi:10.1007/BF00980541

Crespo, M., & Arinero, M. (2010). Assessment of the efficacy of a psycho-

logical treatment for women victims of violence by their intimate male

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com by guest on November 8, 2016

Santos et al. 25

partner. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13, 849-863. doi:10.1017/

S113874160000250X

Cunha, O., & Gonçalves, R. A. (2015). Efficacy assessment of an inter-

vention program with batterers. Small Group Research, 46, 455-482.

doi:10.1177/1046496415592478

Eckhardt, C., Murphy, C., Whitaker, D., Sprunger, J., Dykstra, R., & Woodard, K.

(2013). The effectiveness of intervention programs for perpetrators and victims

of intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 4, 196-231. doi:10.1891/1946-

6560.4.2.196

Fleming, J. B. (1979). Stopping wife abuse. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. B. W. (2002). Structured

Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-

Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP). New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute,

Biometrics Research.

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2014). Violence against women:

An EU-wide survey. Vienna, Austria. Retrieved from http://fra.europa.eu/sites/

default/files/fra-2014-vaw-survey-main-results-apr14_en.pdf

Fritch, A., & Linch, S. (2008). Group treatment for adult survivors of interpersonal trauma.

Journal of Psychological Trauma, 7, 145-166. doi:10.1080/19322880802266797

Gonçalves, M. M., Matos, M., & Santos, A. (2009). Narrative therapy and the nature

of “innovative moments” in the construction of change. Journal of Constructivist

Psychology, 22, 1-23. doi:10.1080/10720530802500748

Gordon, J. (1996). Community services for abused women: A review of perceived

usefulness and efficacy. Journal of Family Violence, 11, 315-329. doi:10.1007/

BF02333420

Holiman, M., & Schilit, R. (1991). Aftercare for battered women: How to encour-

age the maintenance of change. Psychotherapy, 29, 345-353. doi:10.1037/0033-

3204.28.2.345

Iverson, K., Gradus, J., Resick, P., Suvak, M., & Smith, K. (2011). Cognitive-

behavioral therapy for PTSD and depression symptoms reduces risk for future

intimate partner violence among interpersonal trauma survivors. Journal of

Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 193-202. doi:10.1037/a0022512

Iverson, K., Shenk, C., & Fruzzeti, A. (2009). Dialectical behavior therapy for women