Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 154.59.125.17 On Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 154.59.125.17 On Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

Uploaded by

John GalbraithOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 154.59.125.17 On Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 154.59.125.17 On Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

Uploaded by

John GalbraithCopyright:

Available Formats

Music, Image and Ideology in Britten's 'Owen Wingrave': Conflict in a Fissured Text

Author(s): Shannon McKellar

Source: Music & Letters , Aug., 1999, Vol. 80, No. 3 (Aug., 1999), pp. 390-410

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/855029

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/855029?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Music & Letters

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

(? Oxford University Press

MUSIC, IMAGE AND IDEOLOGY IN BRITTEN'S

'OWEN WINGRAVE': CONFLICT IN

A FISSURED TEXT

BY SHANNON McKELLAR

THE CASE put forward in Britten's opera Owen Wingrave is plain: it argue

and extols the virtues of peace.' In the wake of deconstruction

endorsement of pacifist values by contemporary society, today's

typically pays less attention to the widely accepted message than

various textual elements in the work argue the point.2 Within these b

that what has held commentators' interest in particular is a considera

we as the audience find tonal and dramatic resolution-'narrative closure' is a close

literary equivalent-in the process of the argument for peace. Representative accounts

are those that-after finding little 'closure' in plot-turn to musical structures: both

short- and long-range tonal progressions, as well as smaller motifs, that might plausibly

contain-or at least work themselves towards-convincing resolution.3 On balance,

here too Owen Wingrave is often found wanting in that critics consider the opera one of

Britten's less successful in musical, structural and dramatic terms. Commentators most

often identify the problem as one that originates in the Henry James novella on which

the opera is based: Britten and his librettist Myfanwy Piper did much to expunge the

'flaw' in the original, but not enough to eradicate it entirely.4

' Benjamin Britten, Owen Wingrave: an Opera in Two Acts, Op. 85, London, 1995. All references to locations within the

score of the opera cite the figure numbers printed in the vocal score (London, 1970) in the form 'vs fig. 2'; additional

superscript numbers preceded by minus or plus signs indicate respectively the number of bars before or after the figure

number. I am grateful to Pam Wheeler for facilitating my study of film procedures in this opera.

2 However, there is one notable exception that has looked beyond surface meaning. In his 'Benjamin Britten, Owen

Wingrave and the Politics of the Closet; or, "He Shall be Straightened Out at Paramore"', Cambridge Opera Journal, viii

(1996), 59-75, Stephen McClatchie argues that Owen Wingrave, through its overt pacifism, is also 'Britten's exploration

of the possibility of coming out [as a homosexual]' (p. 61): 'because the figure of "coming out" forms the basis for the

conflict in [the] opera (Owen comes out as a pacifist) it seems reasonable, given the close intertwining of pacifism and

homosexuality in Britten's life, to suggest that the latter is displaced on to the former in Owen Wingrave' (p. 74). In this

regard, see also Philip Brett, 'The Authority of Difference', The Musical Times, cxxxiv (1993), 633-6, at p. 634; 'Owen

Wingrave', Brett's notes to the CD reissue of the complete recording, conducted by Britten (London 433 200-2 (1993));

and Humphrey Carpenter, Benjamin Britten: a Biography, London, 1992, p. 513. These are compelling readings,

convincingly argued. This article, which explores forms, rather than the subject, of address, in no way attempts to

contradict these arguments. Indeed one could, if one so wished, substitute 'gayness' for 'pacifism' throughout; the tenor

of the article remains the same.

3 See, for example, Stanley Sadie, 'Owen Wingrave', The Musical Times, cxii (1971), 663-6, at p. 665; Peter Evans, The

Music of Benjamin Britten, rev. edn., Oxford, 1996, p. 603; Arnold Whittall, The Music of Britten and Tippett: Studies in

Themes and Techniques, Cambridge, 1982, pp. 250-55; Carpenter, Benjamin Britten, loc. cit.; and McClatchie, 'Benjamin

Britten, Owen Wingrave and the Politics of the Closet', p. 72.

4Virginia Woolf, 'The Ghost Stories', in Henry James: a Collection of Critical Essays, ed. Leon Edel, Englewood Cliffs,

1963, pp. 47-54; Leon Edel, The Life of Henry James, ii (Harmondsworth, 1977), 664-8 (containing George Bernard

Shaw's criticism of James's stage version of Owen Wingrave, entitled The Saloon); Evans, The Music of Benjamin Britten,

loc. cit; Whittall, The Music of Britten and Tippett, pp. 249-50; Sandra Corse, Opera and the Uses of Language: Mozart, Verdi

and Britten, London, 1987, p. 111; Roland Jordan & Emma Kafalenos, 'The Double Trajectory: Ambiguity in Brahms

and Henry James', 19th Century Music, xii (1988-9), 129-44, at p. 130; Carpenter, Benjamin Britten, p. 508; and Michael

Kennedy, Britten, rev. edn, London, 1993, pp. 249-50.

390

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I aim to readdress this 'problem' of irresolution in the opera but to angle the

argument differently, using an approach that combines an examination of music and

text with a further set of ideas. For what the audience experienced as the premiere on

16 May 1971 was not an opera but a musical-dramatic assignment written for

television. In one sense, my approach may be described as textual: as other essays

have done with various compositions, this article reads the contents of a work which is

now accessible on video as 'text'. However-and specific to Owen Wingrave-the

argument also suggests contextual insight into the time of the making of a particular

film-opera. Film-makers' unspoken attitudes perhaps intrude more on the work than

they are often given credit for, and by considering the opera as text crucially intersected

by non-musical techniques of film, the article turns up signifying conventions that

potentially have their own story to tell of the Snape Maltings (the BBC's studio for the

opera) in the last months of 1970.

While Owen Wingrave was not Britten's first brush with film, it was his first and last

unequivocal 'television opera', composed expressly as a BBC commission. Today it still

holds a special place among the most idiomatic of all the early operatic compositions for

this medium. In 1951 NBC transmitted Menotti's Amahl and the Night Visitors,s the first

opera composed specifically for television. Owen Wingrave and Amahl are alike in their

straightforward plots and small casts. However, with music arguably more suited to

electronic reproduction, and the presence of sophisticated film techniques, Owen Win-

grave is a more televisually-inspired composition than Amahl. Menotti did not think

particularly of television when he wrote his opera, but more of an ideal stage, and this is

doubtless one of the reasons why it has seen over 3,000 stage productions since its first

transmission. Owen Wingrave, on the other hand, presents the producer of the stage

version with difficult obstacles, such as the cross-cutting technique used to portray

Coyle's conversation with Miss Wingrave simultaneously with Owen's monologue in

Hyde Park (Act I scene 2). For these reasons and others outlined below-and not-

withstanding current distrust for the word-it is useful to think of an 'original' Owen

Wingrave 'opera' as the one now captured on film. Moreover, by virtue of what H. Marshall

Leicester calls 'the video revolution',6 it is this version that can most easily be reread.

While film-as-genre has had an attendant academic focus since at least the late

1960s, and film with operatic beginnings has more recently attracted commentary from

musicologists and others,7 commentators on Owen Wingrave have thus far been wary of

incorporating any new system of codes into their interpretations. Perhaps this is

because, despite the production difficulties mentioned above, Owen Wingrave, like

Amahl, can stand alone as 'pure' opera and maintain its status (tellingly, it too has seen

many more live performances than commercial transmissions). And unlike the many

well-known film adaptations of the Carmen story, which are themselves mostly 'read-

ings' of Merimee's and Bizet's versions,8 even as 'television opera' Owen Wingrave still

remains in one sense a 'composer's' rather than a 'producer's' work. Britten's presence

s NBC premiered Amahl on 24 December 1951. Other early operas transmitted by NBC were Martinu's The Mamiage

(1953), Lukas Foss's Grifflkin (1955), Stanley Hollingsworth's La grande Bretiche (1957) and Menotti's Maria Golovin

(1958) and Labyrinth (1963). From 1956, the BBC also began commissioning operas for television, including Bliss's

Tobias and the Angel and Britten's Owen Wingrave (1971).

6 H. Marshall Leicester, Jr., 'Discourse and the Film Text: Four Readings of Carmen', Cambridge Opera Journal, vi

(1994), 245-82, at p. 247.

7 The most prominent remain Jeremy Tambling, Opera, Ideology and Film, Manchester, 1987; Susan McClary, Georges

Bizet: 'Carmen', Cambridge, 1992, pp. 130-46; and Leicester, 'Discourse and the Film Text'.

8 Such as Charles Vidor's Loves of Carmen, Jean-Luc Godard's Prinom Carmen, Carlos Saura's Carmen, Peter Brook's

La tragidie de Carmen and Francesco Rosi's Bizet's 'Carmen'. For a full listing, see Tambling, Opera, Ideology and Film,

pp. 13-40, and McClary, Georges Bizet: 'Carmen' loc. cit.

391

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

was felt in more ways than one by all who were involved in recording the production;

but more important, critics habitually tend to regard the music alone as rich enough to

sustain investigation on purely thematic and technical grounds.

It is here that the boundary between a televised Owen Wingrave and opera-films

such as those inspired by Carmen might most usefully be drawn. In the latter, Bizet's

(or any other opera composer's) music-now chopped up, ironized, reinvented-joins

a soundtrack composed of much more.9 In Owen Wingrave, on the other hand, Britten's

music comprises all the sound, and conventions of Hollywood film, where 'diegetic'

and 'non-diegetic' music combine with speech and non-vocal, concrete sounds to

make up the soundtrack, are absent. This article departs in one crucial way from other

studies that concern reading opera-film. For while, as objects of study that give

commentators the space to pursue readings of readings, the Carmen films are

themselves already a step away from 'opera', Owen Wingrave remains above all a

stylized musical spectacle. Consequently, while commentaries on celluloid versions of

Carmen attend to signifying conventions in film only as part of larger, non-related

argument, in this article, given that techniques of filming are an integral part of

Britten's work, a consideration of the codification of the image is the main focus of a

broader musico-visual-dramatic analysis.

Of course, seeking and detecting narrative closure (or resolution) is an altogether ill-

defined musicological sport. Considerations with a toe in the shark-infested phenom-

enological waters-where senses, feelings even, are under the spotlight-turn out most

often as reception studies. How else, except, as traditional Britten criticism proves,

through analysis of 'the music itself', might one identify a convincing conclusion? Film

theory deriving from psychoanalytic criticism provides one alternative. By stepping into

the realms of the unconscious, where formalism makes space for a more phenomeno-

logical approach that takes into account so-called unstable viewpoints, and where, as

theorists such as Stephen Heath and Colin MacCabe argue, film should be viewed as

an 'ideological' operation,'1 this article will explore interactions between spectators'

perspectives and textual figurations.

After a summary of criticism that largely explores the music of the opera, I focus on

the 'Ballad' story that frames the second and final act. This narrative structure presents

the listener with a tonality wholly in contrast to the overall sound of the opera and is a

section of music that has figured strongly in commentary thus far. Its form, its position

at the end of the opera, and the presence of a narrator, weigh heavily on any

conclusions connected with tonal conflict and resolution. I then turn to a second

point of focus for many critics: the so-called Peace Aria sung by the protagonist in A

II. It is in this pivotal aria that most commentators discern maximum resolution

pinpointing the passage as the moment where the 'peace' message-the raison d'etre o

the opera-comes through most clearly.1 Yet even here, analysis of the music alone,

and a consideration of the aria's position within the dramatic structure, seem to sugge

9 See Leicester, 'Discourse and the Film Text', p. 248.

10 See for instance Jean-Louis Baudry, 'Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus', Film Quarterly

xxviii (1974-5), trans. Alan Williams, repr. in Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings, ed. Gerald Mast, Marsh

Cohen & Leo Braudy, 4th edn., New York & Oxford, 1992, pp. 302-12; Stephen Heath, 'Narrative Space', in Questio

of Cinema, London, 1981, pp. 19-75; and idem, 'Screen Images, Film Memory', Edinburgh Magazine, i (1976), 33-4

For a summary, see Film Theory: an Introduction, ed. Robert Lapsley & Michael Westlake, Manchester, 1988, pp. 67-

104, 129-55.

" Evans, The Music of Benjamin Britten, pp. 504-5, 509, 513, 515-17; John Evans, 'Owen Wingrave: a Case fo

Pacifism?', The Britten Companion, ed. Christopher Palmer, London, 1984, pp. 227-37, at pp. 235-7; Carpenter, Benjami

Britten, p. 512; and McClatchie, 'Benjamin Britten, Owen Wingrave and the Politics of the Closet', pp. 69-72.

392

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

something different-perhaps the ambivalence that characterized Britten generally.'2

In the second part of this essay I concentrate on this passage and the message it is

designed to portray. The aria's pacifist text is transparent enough, but do other forces

interfere?

[Cinema is] a language to the extent that it orders signifying elements within ordered

arrangements different from those of spoken idioms-and to the extent that these elements

are not traced on the perceptual configurations of reality itself (which does not tell stories).

Filmic manipulation transforms what might have been a mere visual transfer of reality into

discourse.'3

Christian Metz's ideas are familiar now-even well-rehearsed-but for the purposes of

this article it is as well to bear in mind that it was the influence of semiology and the

radical 'Left' theorists of the 1960s combined with the post-Brechtian counter-cinema

movement, one which emphasized the artificial and illusionist nature of film, that first

sparked interest in the then unspoken 'codification' of the image. Studies of films in the

Hollywood mould, where levels of camera effacement are high but film techniques still

constitute 'language' able to manipulate and be manipulated, are indebted to these

origins. The differences and correlations between the two types of cinema are also a

springboard from which to begin the present reading.

By February 1969, Britten was well ahead with the composition of his latest opera.

Perhaps because of his experience of having composed for the GPO Film Unit in

1935-6, and having completed a BBC recording of Peter Grimes, Britten had strong

views on relationships between mechanical reproduction and opera on television. In a

conversation with Donald Mitchell, he was adamant that his aim was to compose an

opera for television that emphasized rather than effaced the conventional signs of

operatic 'mechanism'. He argued that 'a successful television opera is more likely to

succeed in so far as specifically musical forms predominate, and the drift away from

realism is pronounced'.14 (This, of course, is where Owen Wingrave departs so radically

from Carmen-type 'realist' films.) Indeed, arias, vocal ensembles and coloratura-all

elements contrary to the realism demanded by the classic film genre-are still present

in Owen Wingrave.

Yet the 'television opera', of course, is not a conventional production for the stage,

for despite its obvious basis in such a form, as a filmed spectacle it calls many more

forces suddenly into play. While Britten was satisfied that he had upheld opera's side

of the bargain throughout the various stages of its composition, he had less control

over the forces that were to create and transmit the impression of 'opera' on-screen. By

choosing to emphasize and elevate 'opera', but at the same time not wishing the film

to be merely an ephemeral document of a one-off staged performance, Britten, the

producer John Culshaw and co-directors Brian Large and Colin Graham opted to

obliterate any evidence of the 'proscenium arch' (e.g., when filmed operas include live

applause, or when the camera pans over the auditorium), as well as to de-emphasize

the signs of mechanical reproduction involved in the 'capturing' of the opera on film.

'2 For a discussion of Britten's ambivalence about his own sexuality-a characteristic of the composer that supports

McClatchie's reading of Owen Wingrave-see Carpenter, Benjamin Britten, pp. 178-9. For a related discussion, see Brett,

'The Authority of Difference', p. 634, in which the author writes of Britten's 'discretionary approach' to disclosing his

sexuality.

13 Christian Metz, Film Language: a Semiotics of the Cinema, New York, 1974, p. 105.

'4 Donald Mitchell, 'Mapreading', The Britten Companion, ed. Palmer, pp. 87-96, at p. 90.

393

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Thus, they recorded Owen Wingrave as an 'opera' but also-and in a sense

paradoxically-placed it within the boundaries of the classical Hollywood film

genre. To a large extent, the work's film techniques and apparatus remain those

one might have expected to find in the latest American movie. While the average

length of a single shot is long, and compares more with the European art film than the

Hollywood film of this era, we find all the conventions typical of this era in film-

making: a move towards the obliteration of the mediatory nature of the recording

process, comprising camera and mechanical effacement, realism, illusion, linearity,

continuity and code.15

Running through Owen Wingrave is thus a subterranean layer of meaning (film

theorists call it a 'discourse') that has not yet been fully tapped by those who consider

the opera in relation to audience reaction. The notion of film as agency, where

constructions of biases in perception offer spectators positions to accept or reject,

should surely be important in examinations of operas like this one where ideology is of

major concern. Regarding film, David Rodowick asks what forms of looking and

hearing are constructed by technology that projects images: 'what biases in perception

and identification are organized in the construction of cinematic images through the

devices of perspective, framing, editing, point of view, the relation of sound to image?'6

Some of these questions are the concerns of this article. In a work of art that contains

the mechanics of both realist Hollywood narrative film and an 'operatic' counter-

cinema, I return to my original question: how might we reread Owen Wingrave, the

film, as a multi-layered text of conflict and resolution? In terms of film techniques, are

there implicit signs advocating a favoured-'pacifist'-approach to the work?

The opera opens with a Prelude during which the orchestra provides a musical

description of a series of Wingrave portraits which hang on the walls of the family

house, Paramore. As the camera roves among the pictures, a different instrument or

instrumental group marks each visual pause with a cadenza based on a diminished

triad that at its end adds a new pitch to an accumulating twelve-note cluster. Near the

Prelude's close, Owen appears, adding the final pitch needed: a D. His instrumental

cadenza, though, is different, interspersing diminished triads with minor and then

major ones. The music already marks Owen as at odds with his past. Act I then opens

in a military establishment. Owen, destined for a career in battle, like generations of

his family before him, instead declares his stand against war. His tutor and fellow

student are horrified but do not react as strongly as his family. 'He will listen to the

House!', his grandfather, aunt and fiancee at Paramore intone when they find out, well

into the first act. Owen finds himself fighting not a national enemy, but his own kind-

and significantly, tradition as well. Act II begins with the opening stanzas of a 'Ballad'

in the Mixolydian mode: a narrator relates the story of a Wingrave ancestor who in a fit

of rage struck his son dead for refusing to defend himself in a fight with a friend. Soon

after, the story continues, the ancestor is found dead in a room of the family house. In

the closing stages of the opera, to music not significantly different from the 'diminished

15 In American and British 'Hollywood' cinema between the years 1964 and 1969, the mean value for the Average

Shot Length (ASL)-calculated by dividing the time of a section by the number of shots within it-was 7.7 seconds. The

long take is the standard mode in European art film of the same era, with common ASL's of 15-20 seconds. Statistics

are from Barry Salt, Film Style Technology: History and Analysis, London, 1992, p. 266.

16 David Rodowick, The Crisis of Political Modernism: Criticism and Ideology in Contemporary Film Theory, Berkeley, Los

Angeles & London, 1994, p. xiii.

394

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

triad' sound-world of the beginning, and which is also reminiscent of the military

rhythms in the Prelude's percussion and later martial patterns (e.g. at vs figs. 51, 99-',

109 and 139), Kate and Sir Philip exclaim upon the sight that lies before them. We

realize that history has repeated itself: Owen, too, in acceding to his fiancee's demand

to 'be a man', meets his end mysteriously in that same room.

Searches for satisfying dramatic resolution by musical means in the final eighteen

bars have never been very successful. After the family members' discovery of Owen's

inert body, the opera concludes with a brief recapitulation of the musically altered

'ballad'. But critics, including Peter Evans and Arnold Whittall, have not been wholly

satisfied. Evans compares the ending of Owen Wingrave with that of The Turn of the

Screw, the opera's counterpart, as he points out, in more than just plot, librettist and

original author. After what he describes as a 'mounting sense of foreboding', Evans

arrives at the concluding 'Ballad' stanza, to find questions he feels are left unanswered:

Whether this suffices to invert the denouement with as overwhelming a force as that of the

Screw must, however, be doubted ... The music at the crucial moment of Kate's discovery of

the body is neither as memorable in itself nor so palpably the crisis in a musical conflict

waged throughout the work ... When Owen finally has to settle his score with (we must

assume) ghosts as well as men, the shift of dramatic level comes too late, however steady the

musical accumulation of tension has been. The end of Owen Wingrave shocks, but it leaves

questions that are not brushed away by the return of the ballad.17

Whittall, on the other hand, following tonal progression through the work, picks out a

tritone which he labels, in Allen Forte's pitch-class terminology, 0,2,5. This set

characterizes both the beginning and end of the 'Ballad' and recurs through the

work at moments of crisis. Whittall describes the final motion from D through F to G

(this being the form in which it ends the opera) as portraying a 'multiple neutrality,

fitting in view of the enormous range of technical possibilities which the language of the

work has explored, and the bleak economy with which its most hopeful and expansive

aspirations are blocked and set aside'.18 Thus, Whittall finds that the 'Ballad' ends

without direct comment on the action that precedes it by drawing tonality and

meaning together. I believe this impression is borne out not only in the music itself

but also through the accumulation of other textual forces that figure in the opera.

The significance of the ballad form, for instance, as a text carried through history,

contributes greatly to the opera's resigned atmosphere. Britten made masterly use of an

oral musical structure (where story-telling is its very function) as an allegory of the

narrative of the opera writ small, to convey the relentless history of the family and

Owen's position within it. Just as the ballad form is strophic and cyclic, ploughing

resolutely to an ending with its traditionally repetitive words, phrases and refrain, so

too is this Owen's experience of the Wingrave tradition. To him, the family militarism

is a force of the past that persists-unwelcome and all too fatal-into his present. Like

the unfolding of the narrative in the 'Ballad', where the outcome of events is

predestined and controlled by the form within which they are presented, Owen

finds that he too cannot escape from his ancestry and has no choice but to resolve the

contest through death. What the opera offers us, then, is the idea that the conflict

caused by Owen's family and the past is resolved, ballad-like, only by tradition. This is

an ending at once pessimistic and appealing to fate; that commentators have been slow

to detect convincing narrative closure is in this context almost unremarkable.

This is not, however, the whole picture, for although the opera ends bleakly, its

7 Evans, The Music of Benjamin Britten, p. 503.

,8 Whittal, The Music of Britten and Tippett, p. 255.

395

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

affirmative pacifist leanings-as most commentators seem to agree-nevertheless carry

the day. How, one might ask, is this achieved? From a tonal perspective and via

consideration of the libretto in isolation, critics often settle on one other point in the

opera as the moment of maximum rest and resolution. It occurs in Act II and is

commonly known as Owen's 'Peace Aria', since it is here that Owen declares that his

stand against war has found him rest. Whittall, for one, describes the passage as

Owen's 'personal and brief moment of truth','9 and most hail the chordal under-

pinning of the aria (a series of major triads that unfold beneath broken chords played

by the glockenspiel, harp, vibraphone, xylophone and piano) as the positive alternative,

in musical terms, to the despondency and ambiguity of the ending.20 In considering

conflict and its resolution, let us turn, then, to the promise this scene seems to hold.

The aria falls dramatically at the moment when Owen has been snubbed,

disinherited and cast out by family, friends and fiancee. He has lost everything

material, but sings that he has 'found his peace'. Indeed, to match this musically,

the aria begins with a cadence (cadences are notable in Owen Wingrave for their scarcity)

on to an unequivocal B% major chord in the woodwind and brass (Ex. 1). As Owen sings

'In peace I have found my image, I have found myself. In peace I rejoice amongst men

and yet walk alone', a series of triads prompts the feeling of repose quite unlike any

music that has come before: the B6 chord gives way to a D minor triad and then an F

major one. This triad in turn 'resolves' on to C major, which is followed by E minor, G

and B. However, as Owen addresses the portraits not long after, at 'O you with your

bugbears, your arrogance, your greed', the diminished triad that characterizes much of

the rest of the opera again becomes prominent. The effect of the glowering family

pictures is to cut short the El chord that forms part of what, in retrospect, is another

twelve-note unfolding by the woodwind and brass. Furthermore, in the rhythm at vs fig.

254 -, listeners are reminded of the opening twelve bars of the opera-distinguished by

uneasy, tense rhythms and linked in the film version to an image of a shield-but it is

not long before Owen reverts once more to his description of peace. He begins this

section accompanied by an F# minor triad, and then major triads on A and C": 'Peace is

not confused, not sentimental, not afraid', Owen sings. However, at fig. 257 the

portraits again interrupt his reverie and the unfolding diatonic chords. In a Sprech-

stimme, facing a portrait of the boy and man from the 'Ballad', Owen issues a challenge.

The two figures become alive and walk out of their frame towards the haunted room

where Owen will later die: 'Ah! I'd forgotten you!', Owen shouts, 'Come on, then,

come on, I tell you'. They disappear in silence through the door to the room. Owen,

having apparently exorcized the ghosts, sings the last two bars of his aria, 'and at last I

shall have peace'. He comes to comparative tonal rest on the final AI major triad with

added sixth. The Aria-albeit with some doubt by the end-is diatonic enough to push

home the message that Owen has found momentary inner peace.

Like the 'court sentence' sequence of chords for which Billy Budd is so well known,21

19 Ibid., p. 250.

"0 McClatchie (and others) go on to link the orchestration of this aria with other Britten operas (The Turn of the Screw,

A Midsummer Night's Dream and Death in Venice), and its effect to the Balinese gamelan. McClatchie is thus led to read

the 'Peace Aria' as representing Otherness, and, by association, a positive assertion of homosexuality.

21 What Britten is portraying in the 'missing' scene from Billy Budd, between Scenes 2 and 3 of Act II of the revised

1960 version, has been the subject of much debate and varying interpretation. The purely musical interlude made up of

34 chords of contrasting dynamic intensity covers the period of time, or a portion of it, when Captain Vere tells Billy the

verdict and the sentence of the court. Many commentators have offered interpretations of what these chords might

represent See Arnold Whittall, "'Twisted Relations": Method and Meaning in Britten's Billy Budd', Cambridge Opera

3ournal, ii (1990), 145-71, for a review of the literature; Barry Emslie, 'Billy Budd and the Fear of Words', Cambridge

Opera Journal, iv (1992), 43-59; and Shannon McKellar, 'Re-Visioning the "Missing" Scene: Critical and Tonal

Trajectories in Britten's Billy Budd', Journal of the Royal Musical Association, cxxii (1997), 258-80.

396

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

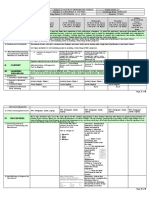

Ex. 1 Owen Wingrave, 'Peace Aria': description of shot composition before

and after each shot transition

2 -calm Clmo (J = c120)

-x - K?r r p r f

- well. In peace I have found my

glock.,

hp., vib.

9:. PP? _ rfrr :f rFrr rFr:rfr

-4 ' - 4 4 4 4

f'bf ( ?itlz pe

(with pedal)

Owen 247'7

-; 2 : i-nt t r n: r

i- mage, I have found my-self. In peace I re -joice

L i Lr

t'---- $ 3

-"--J-~~iS ; 4

Medium shot. Owen facing f

slightly left

Owen 248

a-mongst men and yet walk a-lone, in peace I will guard this

4 3 - 4$

V. t 2

397

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Owen

^ r r p I ? - i - r

ba - lance so that it is not bro- ken.

(t-, M'~ rr~L r 'rr n

4 1w T cregc.

f 3 r---- - 3---3 - - S

of

__ g' f7 ? ? - - - I*

f249|

Owen livelier

4:2f r ::r r __ For peace is not la - zy, but vi-gi-lant,

.P 0

[250]

Owen

Xt , r r p : :#Um; Y $ X

peace is not ac - qui - es-cent, but search -ing,

-3 3 3 l, 3

cresc. slowly

p:e 2.

O2511

Owen ___.------

398

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Owen . r- 3 3 - I _

- r r p n :- r rr - r r :?.^ _i

bird's wing bear - ing its weight in the daz - zling air.

3 3 ' 3 3 3 3

f -t

owe h yo .- ar ccel.

7 iz. ;T v il b f

Peace is not si-lent, it is the voice of love.

It *' J ^ 3W3

5 f f ^

-. . - -- -- -agitat:ed agitato

Oh you with your bug-bears, your ar-ro gance,

5 25s-

I^~ ' ^St

I

^^^ -*-^ ^

399

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Owen

l -C

f--- -- 3

f p a

short

your greed, your in - tol-er-ance, your self-ish mo-rals

fpp cresc.

f cresc.

Close up. Owen facing left, side view. Medium close up. Owen facing front,

slightly left.

C h rven"r L B f----I fr

and pet-ty vic - to-ries, peace is not won by your

w.w., bras perc

a A ?

- A . if l

ffQ

yP W

Close up. Owen facing front, slightly left. ()

A portrait behind.

400

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Owen A-:.i. . * 255- 1 f

^-p 7 v^-fr ? r - r-pip PT D r

- men-tal, not a - fraid. Peace is pos-i-tive, is

--- 4 t

up

_ ^f r p ?yy v ft * 1 4 r *

T I Iw Z X 7 1 1

t v ($X ) 3 i1. v vf5

Owen f

r ^^ ? "6r .p:^ - .i -. .r n

pas-sion - ate, com-mit-ting- more than war_ it- self. On - ly in

i 4 i

_1 IF J [ g Medium close up. Owen facing back,

slightly right He looks at a portrait

\ \I/ which fills most of the frame. - -

Medium shot. Owen

facing front, slightly

right. Same portrait

filling half of frame.

1256>

Owen 3 r --

r r I.' n r f

peace can I be free, And I am fin-ished, fin-ished with you all

', ,

v J

I dim.

MP

401

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The apparitiops of the old man and the boy slowly walk

Slow Lento

12571 speaking excitedly

Owen _ ( (J = 74\ f /-, -

y p Y ? - ! i u^t g Ahl_ I'd for-got-ten youl

gli' . t- bJJ- b-

[p\ FN F Ff , -" . -I

?v . S fA brass ( marked

v f t f , Portrait of boy and father 4 brass(muted),str.

occupies centre of frame.

v^~~ ~ Owen in frame facing back,

Big close up. Owen's bottom left, looking at portrait.

face fills entire frame.

across the hall, and up the stairs.

Owen r----

v U P t P pa pp p- p p pp pp

Come on then, come on, I tell you. You two will nev-er walk_ for me a-

i*b -b JT v. 6"

, 3,

Owen -3---- p f / B B P Pp

v r t p P 7 p 7 Y P p p p

- gain. I'm re-ject-ed, re-ject-ed- the Win-graves have turned me out and you

b--=sy -- - - - -r s ,

: f, (t), (i _ (, J) I 6

Very long shot Owen facing back,

down landing, with boy and father

Very long shot.

in his vision. A portrait behind.

Owen in front of

boy/father portrait,

facing left, down

landing.

402

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Owen The boy turns and looks at OWEN

r 3 ---- --3 I-- [2588 r- 3

: p PiPPP r , p pi r - - r , p p

don't be-long to me, _ nor I to you. Poor boy, you made your

ob. ,

|v4~~~ o4~~ ~~ratherf S

- . J R - - r. J* ~,. J. '-j

24l ' ) J) () (1,)

Very long shot. Owen looks through door at (O O

end of landing. Side view. Boy and father not le

in picture. what Owen sees. Door at end of passage.

Owen /

y P'

stand too young- but I have done it for you- for us all.

p Y

? L 5 cresc. 5 3 f f f

. - b b - b b , t

o, $

cresc.

,3 1I

t?: 'CY

(3g) ()> # (',

403

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The apparitions disappear into the room

Long shot. Owen in frame facing bad

Door in Owen's vision.

Owen not in

frame. Boy Medium long shot. Owen in frame. Boy and father

and father, in gone. Door in Owen's vision.

long shot, still

in Owen's field

of vision, closer

to door.

KATE comes down the

stairs sadly

She does not see OWEN

260 Gently Tranquilo KATE (sadhl PP9

6 -a - - ' 1

Owen Ah,

O PPa - ZAh,

peace

_: ^ ^^ ----^f . ____ pp cold _ -

Reproduced by kind permission of Faber Music Limited

404

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

these chords in Owen Wingrave have had their share of explanatory literature. Typical of

prevailing feeling, Evans describes the aria as follows:

In Owen's apostrophe to Peace, the articulation by richly spaced wind triads that cover a

span of all twelve roots . . . may suggest a parallel with the twelve transfigured triads of the

lovers' awakening [in A Midsummer Night's Dream]. Yet by the end of Owen Wingrave it is

possible to feel that the triads of the famous interlude in Billy Budd offer a closer emotional

parallel; in both contexts an innocent victim is vouchsafed a rarefied, even beatific vision

before he faces his ordeal.22

Whittall regards the chords (unfolding BK-d-F-C-e-G-B; then EF-F#-A-C#; then

AN) as harmonizations of the notes of the triads of B6, C, B and A major, but remarks

that this process breaks down at the last moment (AS major 'replaces' E major at the

end). To him, it is this faltering-played out on a larger scale by the breaking down of

the twelve-note inevitability set up in the very first bar of the opera (the three

tetrachords contain all twelve notes of the chromatic scale)-that portrays Owen's

state of calm and rest, yet paradoxically presages his defeat.23 Like Evans, he compares

the chords dramatically with the parallel series in Billy Budd, but to different-and for

me, intriguing-ends:

These chords range majestically across the tonal spectrum ... until the scheme breaks down

. . and is left incomplete; this confirms as surely as the celebrated chord-sequence in Billy

Budd, that what is 'resolved' is the fact that the hero must die. Owen has not defeated the

curse, but he has banished, if only temporarily, the mindless violence of the twelve-note

chords.24

Whittall's is a compelling reading, advocating a less pat interpretation of one of

Britten's best-known passages. What is more, another long-range tonal connection

between the chord series in the 'Peace Aria' and the three opening tetrachords of the

work suggests a further link that takes Whittall's harmonizations of the unfolding series

(as B6, C, B and A major triads) to its extremes. Stacked in thirds, the chords of the first

bar of the opera form dominant sevenths or ninths, on F, F# and G. 'Resolution' from

here, of course, would be to the major chords on B1, B and C, and these are precisely

the paradigmatic 'triads' outlined by the woodwind and brass in the 'Peace Aria'. But

only the opening chords on F and G find 'unadulterated' resolution.25 The ES triad

sounds amid Owen's first address to the portraits, where they interrupt his reverie.

Ancestry distracts Owen, and mars the hitherto neat (too neat?) tonal resolution of the

conflict set up in the first bar. Even here, in the resolution that is suggested, Owen

cannot escape his past. And a further consideration that takes into account the

intrusions of the 'Ballad' in the 'Peace Aria' by extra-musical means indicates still

other ways that this latter may be more paradoxical than it first appears.

As a starting-point we might compare Owen's narrative of events in the 'Peace Aria'

with the story from the 'Ballad' itself. In the latter's initial appearance at the start of Act

II, it is mostly a narrative account of an occasion in the Wingrave's family history. By

the end of the opera, however, it has accumulated significance beyond its status as

'tale' to reflect and parallel the plight of Owen. Like the boy in the 'Ballad', Owen, too,

comes to die in the same room making his stand for peace, killed through the force of

22 Evans, The Music of Benjamin Britten, pp. 515-16.

23 Whittall, The Music of Britten and Tippett, pp. 251-4.

24 Loc. cit.

25 Whittall (ibid., p. 254) follows a similar, but less metaphorical, line of thinking, to different ends. He points out that

the first of the three tetrachords recurs just before vs fig. 246, with an added G, and that it resolves on to the following B&

triad. However, 'the other two chords of the initial twelve-note complex are not treated in similar fashion'.

405

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

the 'father' figure. Owen really is the boy of the 'Ballad'.26 With Owen's 'Peace Aria',

however, we find at the same time a marked difference in the unfolding of their tales. In

what we might think of as 'Owen's story', the protagonist ends in a state of peace and

thus affirms his stand for pacifism. Conversely, in the 'Ballad' we witness a narrative of

violence and death. As an examination of the music suggests, the alignment of the boy

and Owen begins to conflict with Owen's testimony. Fissures creep into the greater

text. Underlying equivocation-running in parallel with the smooth, diatonic chord

progression-leaves it open, then, for the spectator to ask, at a point in the opera where

music and libretto on the one hand, and structural forms on the other, resist

correspondence, whether Owen's claim that he has found rest is convincing. Just

what topples the balance, steering us towards hearing this aria as an overriding

testimony for peace?

Jeremy Tambling's assertion that 'The ways in which different values permeate

narratives reflect ideological considerations; the dominant views of a society means

that a society gets the narratives its ideological presuppositions support'27 is difficult to

prove in general but provides an interesting springboard from which to approach the

problem of Owen Wingrave. It might, for example, suggest that in this opera

unacknowledged ideological sympathies drive our understanding as much as do

chord choice or text, and not only for critics and listeners but also for the band of

people involved in Owen Wingrave's conception: the film-makers or 'TV guys', as Colin

Graham once described the BBC team.28

I began by considering Britten's wish to preserve the status of 'opera' in the work he

was writing for television. Despite its two-dimensional existence, Britten was concerned

to retain the intangible 'aura'-like ambience of opera that arises only if the audience is

able to see visible signs of effort in live performance. Of course, in stage opera this is

especially noticeable in arias, where the character puts all of his or her powers into

expressing the emotion of the moment, temporarily stepping out of the realism of the

scene into a suspended state: pure expression of sound. What Britten was demanding

of the film-makers was sensitivity to the musical and dramatic flux. In practical terms,

the directors needed to match degrees of realism to the action and reflection of

respective moments in the opera. Britten seemed satisfied that this would be

achieved,29 and he was largely proved correct; in general, the patterns of shot transition

in Owen Wingrave mirror the changes in dramatic pace between the narrative

momentum of recitative and the static reflection of aria typical of opera since the

seventeenth century. A relatively faster rate of transition between shots-said to speed

up narrative momentum-characterizes the recitative and ensemble sections of Owen

Wingrave, while the lengths of shots in the arias are generally much greater. The

'inactivity' of the latter establishes a feeling of repose and generally allows the arias to

work their full operatic effect. As a normally unremarkable technique of setting opera

26 As Nicholas Marston has pointed out to me, this analogy is strengthened by the recurrence of the 'Ballad' at the

end of the opera. Because Act II essentially falls between stanzas of the 'Ballad', it is not inconceivable to 'hear' the

entire second act as an extended penultimate balladic stanza. This would make the events of Act II a mere episode in

the greater progression of the narratively stronger 'Ballad'. Placing Owen and the boy within the same narrative

framework creates even greater connection between them.

27 Jeremy Tambling, Narrative and Ideology, Milton Keynes, 1991, p. 8.

8 Carpenter, Benjamin Britten, p. 514. Along with Large, Graham and Culshaw, the BBC team included David

Myerscough-Jones as designer, advised by John Piper.

29 See Mitchell, 'Mapreading', pp. 87-90.

406

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

on film, this trend of shot-transition speed would hardly be worth further thought were

it not for Owen's 'Peace Aria'. Here, putting our expectations in disarray, conventions

are inverted.

Owen, Coyle, Mrs Coyle, Kate, Mrs Julian and Miss Wingrave have solos that, for

the purposes of this article, I am calling 'arias'. Coyle sings his, beginning 'Straight out

of school', immediately after Owen has announced his intention to leave military

training. Mrs Coyle reflects on her relationship to Owen and his fellow pupil

Lechmere, in 'After a long day'. Mrs Julian shows her agitation when she hears the

news of Owen's decision in her aria 'Oh, oh, how unforeseen'. So, too, does Miss

Wingrave in 'Wingraves are soldiers'. In moments of nostalgia and distress Kate sings

arias beginning 'How strange to abandon the dreams of our childhood' and, later, 'Ah,

Owen, what shall I do?'. Apart from the famous 'Peace Aria', already described, Owen

sings 'And now to face them' and 'Oh Kate, Kate, you too? Is there not one of you to

help me?'. A maximum of three shot transitions divide each of the arias of Coyle, Mrs

Coyle, Kate, Mrs Julian and Miss Wingrave; by contrast, Owen's 'Peace Aria' has

nine. Furthermore, the average shot length is at least twice as short as that of the other

characters' arias in all but three cases: two in which dramatic situation and character

take precedence (Mrs Julian and Miss Wingrave) and one in which a mirror's

reflection of the singer increases the number of shots (Mrs Coyle).30 While we might

liken the average shot length in Owen's 'Peace Aria' to the arias of Mrs Julian and Miss

Wingrave and explain away the faster rates of cutting as technical portrayals of

heightened emotional tension, other techniques which work a much subtler effect in

the positioning of the spectator caution against such easy explanation.

First, still working with the hypothesis that a long shot length contributes towards

slowing the momentum of the work, the contrast in average shot length between Owen

and his colleagues suggests shifts in the narrative texture of the opera. While most of

the characters sing arias-conspicuous 'art forms' from unmoving frames-that film

techniques work to abstract from the action, the unchanging narrative momentum

propelled by a constant and quickened change of shot finds Owen in the opposite

situation: he sings, instead, much more as part of the unfolding narrative's events and

of the realistic cinema of the Hollywood mould. His sentiments form part-indeed the

apex-of pacifism in both the plot and the opera as a whole. Not only shot length,

however, but the entire mechanism of the image here seems to work to this effect. The

multiply varied methods of shot transition, for instance, also contribute towards

embedding Owen's aria within the narrative energy of the text. While the other

characters' arias-where methods of change from one shot to another are limited-are

static and artificial, and thus removed from the momentum of the work, those in the

'Peace Aria' cover the gamut of Hollywood practice, ranging from the dissolve and fade

to the standard continuous cut, and a whip pan on cut 5 (see Fig. 1). The shots of the

arias of the minor characters, on the other hand, are generally joined by one, or at most

two, types of cut. In comparison to the dynamism in Owen's 'Peace Aria', their static

mode of change emphasizes, once again, the artifice of the aria as 'song'.

The larger number and variety of shots in Owen's aria also works in another way.

One could take into account the theory that asymmetries opened up by plot

30 The exact values of the average shot lengths of the arias in the work, in seconds, are as follows: Coyle, 'Straight out

of school', vs figs. 32-6: 52. 5; Mrs Coyle, 'After a long day', figs. 69-75: 33.3; Mrs Julian, 'Oh, oh, how unforeseen',

figs. 101-5: 16.25; Kate, 'How strange to abandon the dreams of our childhood', figs. 105-8'1: 65; Miss Wingrave,

'Wingraves are soldiers', figs. 110-1-12: 19; Owen, 'And now to face them', fig. 115-21-1: 13.125; Owen, 'Oh Kate,

Kate, you too? Is there not one of you to help me?', figs. 128 "-30: 15; Owen, the 'Peace Aria' 'In peace, I have found

my image', figs. 246-60: 25; Kate, 'Ah, Owen, what shall I do?', figs. 260-262+4: 85.

407

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

dissolve cut cut cut whip pan cut cut fade dissolve

l I

I I

l I

Fig.

prog

ries

(The

secu

shot

have

oper

is re

the

inst

mod

pers

tran

the

shot

tech

char

othe

Perh

aria

exis

take

effe

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

VI cn C cnA cA Ecn wCA X t) c *) c v cn

Fig. 2 Owen Wingrave, 'Peace Aria': camer

31 See Film Theory, ed. Lapsley & Westlake, p. 137.

3 Clearly it would be useful here to reproduce 'stills' of

prepared to grant me permission to do so. My thanks to

408

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Owen's sweeping gaze around the room, suggests a heightening of emotional tension.33

It is the point at which Owen has addressed the portraits of his ancestors and has

disavowed them as no longer having power over him: 'And I am finished, finished with

you all'. It is also, however, the point at which he turns to face the figures of the man

and his son from the 'Ballad' story ('Ah! I'd forgotten you!'). Together, they embody

not just ancestry but tradition: the force with which in the end Owen has most to

contend. By the closing bars of the opera, the spectator will realize that the turning-

point in Owen's aria created by camera techniques is also the crux around which the

opera revolves. Owen fights and dies having to prove his courage, not because of the

living Wingraves but because of tradition (formally encapsulated in the 'Ballad'), which

is inescapable and unchangeable.

Owen's ancestral figures in the portraits-and in the 'Ballad'-thus paradoxically

lend their own emphasis to the main character's ways of thinking, additionally leading

the spectator along this same path. Other devices also work to this effect. The Lacanian

psychoanalyst Michel Poizat is well known for his association of traditional 'aria' with

the qualities ofjouissance: the experience of ecstatic containment in a sound-world, and

a self-forgetfulness.3 This aspect of aria, in which the character experiences self-

enclosure and a corresponding suppression of critical awareness in relation to his or

her surroundings or the other characters, is represented as a type of leitmotiv

throughout Owen Wingrave. There is often a mirror or reflective pane of glass in the

background to a scene, especially in moments of pure 'song'. This idea is most

obviously played out in Mrs Coyle's aria when she stands, in close-up, in front of a

mirror. It reflects her image as she sings to herself in front of it. However, by

embedding Owen's song within the actual diegesis of the work-with symmetrical

design and shot length, and the greater amount of attention that the camera eye pays to

the portraits-film techniques deny Owen the very quality that characterizes solo song

as aria. His song for peace is neither reflective nor wholly enclosed; he builds

awareness only in relation to others, and sings, in effect, to the portraits and not to

himself. His voice echoes from within the narrative space of the film, and not, like the

others during moments of aria, from without.

The large percentage of shot/reverse-shot cutting itself works to emphasize Owen's

visual perspective and point of view. Instead of the subject looking voyeuristically at the

object, he or she takes up Owen's position, shadowing him and looking with his eyes at

the world he sees. Even in Mrs Julian's solo, an aria close in editing techniques and

average shot length to Owen's, there are no shot/reverse-shot patterns of cutting. The

almost motionless camera focuses on an unchanging singer for large parts of each shot.

Mrs Julian faces front or slightly right every time; the spectator finds less sympathy for

her cause than for Owen's.

With film techniques that register a favoured identification in Owen Wingrave and-

crucially-embed Owen's aria within the narrative, we begin to recognize 'ideal

consumption' pointers-ideological forces-at work that emphasize Owen's message

above any other and set the spectator to hear it most clearly. In the end, despite the

textual conflict of the 'Ballad' narrative that intrudes through both text and music in

the 'Peace Aria', various techniques present the spectator with a work that encourages

a certain perspective and fixed interaction. Rather than abstracting Owen's sense of

peace and fulfilment from the action of the opera, systems of filming make Owen's

pacifist thoughts the crucial point-indeed the apex-of the (pacifist) opera's

33 It is also close to the temporal mid-point of the aria, occurring at 2'14" of an aria 4'1" long.

4 See Michel Poizat, The Angel's Cry: beyond the Pleasure Principle in Opera, Ithaca & London, 1992.

409

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

progression. The climax offered by the 'Peace Aria' leads us to believe that at this

point there is indeed resolution in the work as a whole. Pacifism is tenable. In the

absence of a wholly convincing resolution at the end of the work, it is in the 'Peace

Aria' that this message comes through most clearly. Here, camera editing-a

language largely unwritten-displaces our feeling of irresolution and sets firm the

ideological basis on which the opera rests.

Is there resolution? In the absence of a firm conclusion in the closing bars of the opera,

and leaving aside the influence the ballad form has on an overriding message, do we

find it in the 'Peace Aria', and, if so, does this affirmation have enough force to carry

through to the end of the work and beyond? Tambling draws attention to the fact that

these, in themselves, are questions typical of the commentator already immersed in

ideology:

The desire to find a resolution is a fine example of liberal-humanist criticism to wish to

suggest that the author of a text can solve some crises in his/her art: thus suggesting that the

terms in which the author sets up the debate are the appropriate ones to resolve it in, as

though those terms could be complete.35

Perhaps, though, one might counter that it is this very ideology within which we work

that allows and encourages the interaction of the spectator with the text; it is exactly

where the text differs most from itself, and thereby presents a puzzle, that the viewer is

most engaged; it is where the concept of a single, responsible authorial hand dissolves,

rather, into a web of interconnecting forces-where Britten's personal ambivalences

come to the fore and his works' well-known unanswerable questions remain-that the

aesthetic object attains its fullest form and makes the operas living texts, pertinent to

us now.

In general terms, Owen Wingrave also offers us the chance to look more

signifying conventions that contribute towards creating the aesthetic objec

to grips with most opera-on-film, camera techniques can be additiona

than-transparent hermeneutic windows on to interpretation. By paying a

signifying codes and foregrounding operations of film in screened opera,

even be able to suggest ways that might beneficially alter the balance in

scholarship. Stage opera is already diffuse and multi-authored, split betw

poser and librettist at the one end and producer, director, designer,

conductor at the other. Filmed opera and opera-film have added dim

mechanisms that perform significant perceptual functions. With the diss

such works, we may come to a richer appreciation of how cinematic tech

in muted but meaningful-perhaps even crucial-undertones.

3S Tambling, Opera, Ideology and Film, p. 123.

410

This content downloaded from

154.59.125.17 on Mon, 13 Dec 2021 14:44:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Screenplay Writing The Picture 2nd Edition PDFDocument791 pagesScreenplay Writing The Picture 2nd Edition PDFAna Luiza Bernardes100% (10)

- Packer - Movies-and-the-Modern-Psyche PDFDocument217 pagesPacker - Movies-and-the-Modern-Psyche PDFГлигор КондовскиNo ratings yet

- Pub - Choral Music On Record PDFDocument317 pagesPub - Choral Music On Record PDFDolhathai IntawongNo ratings yet

- Sample PDF Casting RevealedDocument20 pagesSample PDF Casting RevealedMichael Wiese Productions0% (1)

- (Textxet - Studies in Comparative Literature) Sabine Lichtenstein (Ed.) - Music's Obedient Daughter - The Opera Libretto From Source To Score-Rodopi (2014)Document505 pages(Textxet - Studies in Comparative Literature) Sabine Lichtenstein (Ed.) - Music's Obedient Daughter - The Opera Libretto From Source To Score-Rodopi (2014)Cesar Octavio Moreno ZayasNo ratings yet

- Anakreons GrabDocument19 pagesAnakreons GrabEugene Salvador100% (1)

- The Oral Testimony and The Embodied Witness - Orality IntersubjecDocument320 pagesThe Oral Testimony and The Embodied Witness - Orality IntersubjecNathaniel LozanoNo ratings yet

- Jaws Theatrical Film Poster AnalysisDocument2 pagesJaws Theatrical Film Poster AnalysisSGmediastudies100% (1)

- Ooozk Dkfdad CsDocument6 pagesOoozk Dkfdad CsOzan SarıkayaNo ratings yet

- 4 - Stage and ScreenDocument53 pages4 - Stage and ScreenMadalina HotoranNo ratings yet

- American Association of Teachers of German, Wiley The German QuarterlyDocument19 pagesAmerican Association of Teachers of German, Wiley The German QuarterlycarmenmatomasedaNo ratings yet

- Bordwell, David. "The Musical Analogy"Document16 pagesBordwell, David. "The Musical Analogy"Mario PMNo ratings yet

- Screen - Volume 15 Issue 4Document99 pagesScreen - Volume 15 Issue 4Krishn KrNo ratings yet

- Academia PDFDocument89 pagesAcademia PDFLigia FarcaselNo ratings yet

- CorrectedTHESIS FORPRINTERS FinalDocument332 pagesCorrectedTHESIS FORPRINTERS Finalমমিন মানবNo ratings yet

- Screening the Stage: Case Studies of Film Adaptations of Stage Plays and Musicals in the Classical Hollywood Era, 1914-1956From EverandScreening the Stage: Case Studies of Film Adaptations of Stage Plays and Musicals in the Classical Hollywood Era, 1914-1956No ratings yet

- KETTERER, Robert C. - Militat Omnis Amans. Ovidian Elegy in L'Incoronazione Di PoppeaDocument16 pagesKETTERER, Robert C. - Militat Omnis Amans. Ovidian Elegy in L'Incoronazione Di PoppeaRamiroGorritiNo ratings yet

- Jeremy Hicks - Dziga Vertov - Defining Documentary Film On EnthusiasmDocument34 pagesJeremy Hicks - Dziga Vertov - Defining Documentary Film On EnthusiasmarinaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 150.252.248.225 On Thu, 02 Dec 2021 19:58:09 UTCDocument33 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 150.252.248.225 On Thu, 02 Dec 2021 19:58:09 UTCKase BrantNo ratings yet

- Schreker 1Document59 pagesSchreker 1jordi_f_sNo ratings yet

- Benjamin BrittenDocument317 pagesBenjamin BrittenDiego Mauricio Alea Poveda0% (1)

- PACKER, E. (2014) - Leitmotif in Star WarsDocument21 pagesPACKER, E. (2014) - Leitmotif in Star WarsDmitry KalinichenkoNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press Cambridge Opera JournalDocument24 pagesCambridge University Press Cambridge Opera JournalJason ChingNo ratings yet

- Raymond Williams - Drama in Performance-C. A. Watts (1968)Document213 pagesRaymond Williams - Drama in Performance-C. A. Watts (1968)Manuel Botía75% (4)

- I - Cosě Fan Tutte - I - Brilliance or BuffooneryDocument12 pagesI - Cosě Fan Tutte - I - Brilliance or BuffooneryAna UdreaNo ratings yet

- Attfield, N., & Winters, B. (Eds.) - (2018) - Music, Modern Culture, and The Critical Ear A Festschrift For Peter Franklin (1st Ed.) - Routledge.Document289 pagesAttfield, N., & Winters, B. (Eds.) - (2018) - Music, Modern Culture, and The Critical Ear A Festschrift For Peter Franklin (1st Ed.) - Routledge.方科惠100% (1)

- What Is Film MusicDocument8 pagesWhat Is Film MusicKaslje ApusiNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument17 pagesPDFpiNo ratings yet

- Sinfonia CaracteristicaDocument20 pagesSinfonia CaracteristicaoliverhanceNo ratings yet

- Musicality in TheatreDocument320 pagesMusicality in TheatreOlya Petrakova100% (6)

- Music in FilmsDocument44 pagesMusic in FilmsprzegorzgotockiNo ratings yet

- At The Margins of The TelevisuDocument22 pagesAt The Margins of The TelevisuEstela Ibanez-GarciaNo ratings yet

- Pitch in Viols and Harpsichords in The Renaissance - Nicholas MitchellDocument20 pagesPitch in Viols and Harpsichords in The Renaissance - Nicholas Mitchellalsebal100% (1)

- Vostell TVRitualDocument11 pagesVostell TVRitualAnonymous y9IQflUOTmNo ratings yet

- Document PDFDocument60 pagesDocument PDFAdailtonNo ratings yet

- Unsung Voices: Opera and Musical Narrative in the Nineteenth CenturyFrom EverandUnsung Voices: Opera and Musical Narrative in the Nineteenth CenturyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- CanonDocument5 pagesCanonCarlos CalderónNo ratings yet

- Full Ebook of Music Modern Culture and The Critical Ear A Festschrift For Peter Franklin 1St Edition Nicholas Attfield Online PDF All ChapterDocument69 pagesFull Ebook of Music Modern Culture and The Critical Ear A Festschrift For Peter Franklin 1St Edition Nicholas Attfield Online PDF All Chapterjohnneely951108100% (5)

- Acting and Directing in The Lyric Theater An Annotated ChecklistDocument12 pagesActing and Directing in The Lyric Theater An Annotated Checklistvictorz8200No ratings yet

- M. Miller - Film Music The Material, Literature and Present State of ResearchDocument39 pagesM. Miller - Film Music The Material, Literature and Present State of ResearchMasha Kolga100% (1)

- Conversation With KrenekDocument10 pagesConversation With KrenekPencils of PromiseNo ratings yet

- Yudkin (1992) Beethoven's Mozart QuartetDocument46 pagesYudkin (1992) Beethoven's Mozart QuartetIma BageNo ratings yet

- Yudkin - 1992 - Beethoven's Mozart QuartetDocument46 pagesYudkin - 1992 - Beethoven's Mozart QuartetGilmario BispoNo ratings yet

- Dziga Vertov - Defining Documentary Film - 2007 PDFDocument209 pagesDziga Vertov - Defining Documentary Film - 2007 PDFJonathan FortichNo ratings yet

- Babitz Violin Staccato in The 18th Century 1955Document2 pagesBabitz Violin Staccato in The 18th Century 1955charles5townNo ratings yet

- Musical Times Publications LTDDocument6 pagesMusical Times Publications LTDРадош М.No ratings yet

- London, Proms 2012 (2) - Olga Neuwirth, Kaija SaariahoDocument4 pagesLondon, Proms 2012 (2) - Olga Neuwirth, Kaija Saariahostis73No ratings yet

- Ovenden SchumannsFirstSymphony 1929Document2 pagesOvenden SchumannsFirstSymphony 1929Lucía Mercedes ZicosNo ratings yet

- Cage Cunningham Collaborators PDFDocument23 pagesCage Cunningham Collaborators PDFmarialakkaNo ratings yet

- Revisiting The Historiography of Postwar Avant Garde Music 1st Edition Anne Sylvie Barthel Calvet Editor Christopher Brent Murray EditorDocument70 pagesRevisiting The Historiography of Postwar Avant Garde Music 1st Edition Anne Sylvie Barthel Calvet Editor Christopher Brent Murray Editortoddsalviejo945406100% (5)

- Double Horn ConcertoDocument29 pagesDouble Horn ConcertoJosef OtrhálekNo ratings yet

- Laughter Over Tears: John Cage, Experimental Art Music, and Popular TelevisionDocument16 pagesLaughter Over Tears: John Cage, Experimental Art Music, and Popular TelevisionmarcfmsenNo ratings yet

- Listening to Reason: Culture, Subjectivity, and Nineteenth-Century MusicFrom EverandListening to Reason: Culture, Subjectivity, and Nineteenth-Century MusicNo ratings yet

- Beethoven The Pianist by Tilman SkowroneckDocument6 pagesBeethoven The Pianist by Tilman SkowroneckMarc WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Richard Wagner's Reception of BeethovenDocument300 pagesRichard Wagner's Reception of Beethovenpascumal100% (1)

- Brecht SingingDocument25 pagesBrecht SingingJasmine BlundellNo ratings yet

- Final Paper First DraftDocument7 pagesFinal Paper First Draftledno_neuroNo ratings yet

- Meaning in The Motives: An Analysis of The Leitmotifs of Wagner's RingDocument11 pagesMeaning in The Motives: An Analysis of The Leitmotifs of Wagner's Ringshadhu_satanaNo ratings yet

- Attractively Packaged But Unripe Fruit: The Uk's Commercialization of Musical History in The 1980's.Document8 pagesAttractively Packaged But Unripe Fruit: The Uk's Commercialization of Musical History in The 1980's.Pipo PipoNo ratings yet

- Chopin's A-Minor Prelude and Its Symbolic Language - LeikinDocument15 pagesChopin's A-Minor Prelude and Its Symbolic Language - Leikincalcant2No ratings yet

- KNNKDocument300 pagesKNNKGabriel AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Who Wrote The Mozart Four-Wind ConcertanteDocument3 pagesWho Wrote The Mozart Four-Wind Concertantebotmy banmeNo ratings yet

- Godsall Music by Zbigniew Preisner Pre Copy Edited PDFDocument23 pagesGodsall Music by Zbigniew Preisner Pre Copy Edited PDFВладNo ratings yet

- Stefania Marghitu, PH.D.: EducationDocument10 pagesStefania Marghitu, PH.D.: EducationStefania MarghituNo ratings yet

- Cinema Space and Polylocality in A Globalizing ChinaDocument274 pagesCinema Space and Polylocality in A Globalizing China.No ratings yet

- Editor's Introduction: Toward A Feminist Politics of Comedy and HistoryDocument14 pagesEditor's Introduction: Toward A Feminist Politics of Comedy and HistoryApologistas de la CalamidadNo ratings yet

- Creative Critical ReviewDocument36 pagesCreative Critical ReviewManahil Azfar RanaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3: Types of Movies The Idea of A NarrativeDocument4 pagesChapter 3: Types of Movies The Idea of A NarrativesharrpieeNo ratings yet

- Media and Information Languages Genre Codes and ConventionsDocument33 pagesMedia and Information Languages Genre Codes and ConventionsStephanie Jessa ChinteNo ratings yet

- Harvard - Art of Film SyllabusDocument14 pagesHarvard - Art of Film SyllabusTitoNo ratings yet

- Thesis Paper - Prof. Erwin GlobioDocument43 pagesThesis Paper - Prof. Erwin GlobioPROF. ERWIN M. GLOBIO, MSITNo ratings yet

- Television Genres - IntertextualityDocument8 pagesTelevision Genres - IntertextualityAldy MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Unit12 PlanDocument1 pageUnit12 Planapi-201512422No ratings yet

- Emily Campbell Oct 2018 Resume - NDocument1 pageEmily Campbell Oct 2018 Resume - Napi-417241173No ratings yet

- Combined ArtsDocument11 pagesCombined ArtsJoshua Emmanuel Sibug56% (9)

- Topic: Media-Based Arts and Design in The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesTopic: Media-Based Arts and Design in The PhilippinesJesMae CastleNo ratings yet

- Sample of A Persuasive EssayDocument8 pagesSample of A Persuasive Essayhqovwpaeg100% (2)

- Barton Byg - Landscapes of Resistance The German Films of Daniele Huillet and Jean-Marie StraubDocument286 pagesBarton Byg - Landscapes of Resistance The German Films of Daniele Huillet and Jean-Marie StraubLuís Flores100% (1)

- Contemporary Arts q2Document28 pagesContemporary Arts q2Nhika Joyce JulioNo ratings yet

- Creating Broadcast Advertising: Chapter OutlineDocument37 pagesCreating Broadcast Advertising: Chapter OutlineFhelma Barrameda MalimbanNo ratings yet

- 2 MDB - Movies, TV and Celebrities - IMDbDocument4 pages2 MDB - Movies, TV and Celebrities - IMDbBala MuruganNo ratings yet

- DLL English q1 Week 4Document8 pagesDLL English q1 Week 4Alexandra HalasanNo ratings yet

- Tarkovsky and BrevityDocument16 pagesTarkovsky and BrevityEun Suh Rhee100% (1)

- Art ReviewDocument86 pagesArt ReviewJOANA MANAOGNo ratings yet

- 3D Computer AnimationDocument23 pages3D Computer AnimationdrajkumarceNo ratings yet

- Film - A Montage of TheoriesDocument388 pagesFilm - A Montage of TheoriesDebanjan BandyopadhyayNo ratings yet

- Vietnamese Cinema First ViewsDocument31 pagesVietnamese Cinema First ViewsHamza WaqasNo ratings yet

- Upcoming Movies 2021 List of Movies Releasing TDocument1 pageUpcoming Movies 2021 List of Movies Releasing TGanesh SelvarajNo ratings yet