Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Canine Pancreatitis: Profile

Canine Pancreatitis: Profile

Uploaded by

Lorena TomoiagăOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Canine Pancreatitis: Profile

Canine Pancreatitis: Profile

Uploaded by

Lorena TomoiagăCopyright:

Available Formats

Consultant on Call Emergency Medicine / Gastroenterology / Hepatology Peer reviewed

Canine Pancreatitis

Andrew Linklater, DVM, DACVECC

Lakeshore Veterinary Specialists

Glendale, Wisconsin

Profile tent) and some toxins (eg, zinc, castor

beans) are generally accepted causes.

Definition ■ Other causes include pancreatic

■ Pancreatitis (ie, inflammation of the ischemia (result of hypotension from

pancreas) can be acute, chronic, or fluid loss or anesthesia); surgical

acute on chronic. manipulation (poorly described); bil- 2 + 1+

iary, pancreatic duct, and intestinal

Systems disease; and pancreatic trauma.

■ Effects range from mild GI signs (eg, ■ The inciting cause may be idiopathic.

decreased appetite, occasional vomit- +

ing) to systemic inflammatory response risk Factors +

syndrome (SIRS) and multiple-organ ■ Patients that are obese or have other

dysfunction syndrome. endocrine disease or systemic illness 1

may be at risk.

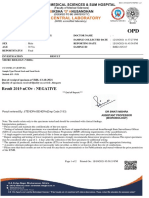

Incidence & Prevalence ■ Hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, Ultrasound of the right upper quadrant of a

hypothyroidism, and hyperadreno- dog’s abdomen showing changes often noted

■ Increasing diagnostic sensitivity and

with pancreatitis (eg, thickened, hypoechoic

specificity may result in an increased corticism have been associated with pancreas [yellow arrow], surrounding

incidence of pancreatitis diagnosis. pancreatitis. hyperechoic mesentery [white arrow])

❏ Whether these are comorbidities

signalment or causing factors is unknown.

Breed Predilection

■ Any breed can be affected. Pathophysiology leukin-1) production, and result in

■ Several breeds (eg, schnauzer, York- ■ Results from activation of potent pan- subsequent neutrophil recruitment

shire terrier, spaniels, boxer, Shetland creatic enzymes and local and sys- and exacerbation of the inflamma-

sheepdog, collies) are overrepresented.1 temic consequences of the ensuing tory cascade.

❏ Whether genetic mutations of serine inflammation. ■ In severe cases, this may result in

protease inhibitors in schnauzers ❏ Several homeostatic mechanisms systemic consequences (eg, SIRS)

contributes to the development of prevent intrapancreatic activation of with devastating effects: focal or

pancreatitis has not been determined. these enzymes. diffuse peritonitis, respiratory

■ In healthy states, these enzymes difficulty (eg, acute respiratory

Age & Range are stored as zymogens in an inac- distress syndrome [ARDS]), renal

■ Typically affects middle-aged to older tive form and segregated in the injury, hepatobiliary dysfunction,

patients that may be overweight or endoplasmic reticulum. and coagulopathic disease (eg, dis-

have history of dietary indiscretion ❏ When enzymes are abnormally acti- seminated intravascular coagula-

vated in the pancreas, the ensuing tion [DIC]).

Causes proteolysis activates the inflamma- ❏ Local inflammation can lead to

■ Underlying causes are poorly understood. tory cascade and production of free increased capillary permeability,

■ Several veterinary medications have radicals and phospholipase, which edema, necrosis, and hemorrhage.

been implicated to cause pancreatitis. can disrupt cellular membranes,

■ Dietary indiscretion (± high-fat con- cause cytokine (eg, TNF-α, inter- MORE

ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome, DIC = disseminated intravascular coagulation, SIRS = systemic inflammatory response syndrome

October 2013 • clinician’s brief 83

Consultant on Call

History, Physical Examination, & from vomiting (eg, hypochloremic/ often identify characteristic ultra-

Clinical signs hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis). sonographic changes consistent with

■ Common presenting complaints ❏ Azotemia can be present and is most pancreatitis (eg, enlarged hypoe-

include decreased appetite or anorexia, commonly associated with prerenal choic or mixed echogenic pancreas

lethargy, vomiting, diarrhea, and dehydration, which may also be with surrounding hyperechoic

abdominal pain. reflected in elevated total protein. mesenteric tissue, variable disten-

■ Examination findings are often non- ■ Hypoalbuminemia may result from tion/functional obstruction of the

specific but may include evidence of GI losses, potential third space fluid biliary system, small amounts of free

nausea (eg, lip licking, ptyalism, regur- accumulation, and/or development fluid in the abdomen consistent

gitation/vomiting with abdominal of peritonitis; albumin is a negative with focal peritonitis, thickened or

palpation, eructation), dehydration, acute-phase protein. corrugated appearance to the duo-

altered gut sounds (increased/ ■ Lipase and amylase have poor sensi- denum, intestinal ileus).

decreased borborygmi), abdominal tivity and specificity for pancreatitis ❏ A normal ultrasound does not rule

pain, fever, icterus, and hypovolemic (amylase, 14%–73%; lipase, 18%–69%). out pancreatitis.

shock. ❏ Commercial laboratory and point- ■ Advanced imaging (eg, CT) is likely

❏ Similar signs may result from other of-care canine pancreas-specific more sensitive but is often not pur-

causes of acute abdomen: gastro- lipase (cPLI) tests have demonstrated sued because of cost.

enteritis, hemorrhagic gastroenteri- sensitivity of ≥82% and specificity of

tis, toxin ingestion, hepatobiliary 96% for diagnosing pancreatitis, Other Diagnostics (if applicable)

disease, primary infiltrative or although false-negative and false- ■ Laparoscopically obtained biopsy

obstructive GI disease, renal disease, positive results may occur.1 may be an alternative to celiotomy for

lower urinary tract disease, liver ■ The sensitivity of other diagnostic gathering histopathologic evidence of

failure, organ torsion. testing is much lower: trypsin-like pancreatitis when other imaging tech-

immunoreactivity (cTLI) has a niques are unavailable or unclear.

Diagnosis sensitivity of 36%–47% and

abdominal ultrasonography, 68%.1 Treatment

■ Histopathologic examination of the ■ Further studies comparing cPLI

pancreas is the gold standard. with histopathologic and imaging Inpatient or Outpatient

❏ Most patients do not require sur- findings are warranted. ■ Inpatient or outpatient treatment is

gery, and diagnosis is often based on ■ Additional routine diagnostics (eg, largely based on severity of clinical

historical and physical examination urinalysis) may be necessary. signs.

findings with clinical pathology and ■ Secondary systemic complications ❏ Patients that fail outpatient therapy

abdominal imaging. may indicate coagulation times, blood should be hospitalized.

■ However, many of these findings gas analysis, urine culture, and cytologic ■ The mainstay of therapy is to treat or

have relatively poor sensitivity and clinicopathologic evaluation of eliminate the underlying cause and pro-

and/or specificity for pancreatitis. abdominal fluid (if present), along with vide symptomatic and supportive care.

thoracic radiography. ❏ The author recommends Kirby’s

Laboratory Findings Rule of 20 to monitor patient

■ CBC data for diagnosis include: Imaging requirements.2,3

❏ Elevated PCV from dehydration ■ Abdominal radiographic findings are

❏ Inflammatory leukogram (± left shift) usually nonspecific but may demon- Medical

❏ Thrombocytopenia strate detail loss or ground glass ■ Crystalloid fluid supplementation

■ Serum biochemistry profile abnormal- appearance in the right upper quad- should be used to correct perfusion

ities may include mild-to-moderate rant and a wide angle between the deficits and dehydration with ongoing

elevation of cholestatic or specific duodenum and stomach antrum. supplementation to account for main-

hepatocellular liver enzymes and ■ Ultrasonography (Figure 1, previous tenance and continued losses.

bilirubin. page) remains one of the most com- ❏ Patients with fevers have mildly

❏ Electrolyte and blood gas abnormal- mon methods to diagnose pancreatitis. increased fluid requirements (~7%

ities are often secondary to fluid loss ❏ A skilled ultrasonographer can more than normal for each degree).4

COP = colloid osmotic pressure, cPLI = canine pancreas-specific lipase, cTLI = canine trypsin-like immunoreactivity, SIRS = systemic inflammatory response syndrome

84 cliniciansbrief.com • October 2013

■ Colloid management with hydroxy- Radiograph confirming appropriate postoperative placement of a nasogastric tube in

ethyl starches is often used to sup- 2 a dog

plement patients with SIRS presenta-

tions (that lead to capillary leak and

protein losses) to help maintain

colloid osmotic pressure (COP).

■ Potassium supplementation is often

necessary.

■ Administration of fresh frozen plasma

has shown no benefit.

■ Analgesic therapy may improve

appetite, ventilatory capacity, and

mobility.

❏ Opioid analgesics (eg, fentanyl,

methadone, hydromorphone [see

Table]) may help resolve abdominal

pain.

❏ Infusions of ketamine and lidocaine

or local therapies (eg, epidural injec-

tions) may be used to treat pain. Drugs Commonly Used During Pancreatitis Therapy

❏ NSAIDs and steroids may exacer-

Table

bate GI ulceration, renal injury, and

pancreatitis. Drug Function Dose Route Frequency

■ Antiemetics for vomiting or nausea

Chlorpromazine Antiemetic/sedative 0.2–0.5 mg/kg IV, IM, SC q8h

are commonplace; newer available

drugs (eg, maropitant, dolasetron, Dolasetron Antiemetic 0.5–1 mg/kg IV or PO q24h

ondansetron [see Table]) can decrease Fentanyl Analgesic 5–10 mcg/kg/h IV CRI

vomiting. Hydromorphone Analgesic 0.1–0.2 mg/kg IV, IM, SC q6–8h

❏ Recent studies have shown that maro-

Ketamine Analgesic 10–20 mcg/kg/min IV CRI

pitant is more effective than meto-

Lidocaine Analgesic 1–5 mg/kg/h IV CRI

clopramide and chlorpromazine.5,6

■ Proton pump inhibitors (pantoprazole) Maropitant Antiemetic 1 mg/kg SC q24h

or histamine-2 receptor antagonists 2–8 mg/kg PO q24h

(ie, famotidine) and sucralfate can (max

help treat associated gastric ulcers. 2–5d)

■ Because most pancreatitis cases are Methadone Analgesic 0.1–0.5 mg/kg IV, IM, SC q6–8h

not associated with bacterial infection, Metoclopramide Antiemetic/prokinetic 0.1–0.4 mg/kg IM, SC q8h

antibiotic therapy is rarely warranted. 1–2 mg/kg/d IV CRI

❏ However, select cases may benefit

Ondansetron Antiemetic 0.5–1 mg/kg PO q8–24h

from antibiotics.1

■ Plasma transfusions (to deliver colloid

support via antitrypsin/antiproteases)

have shown little benefit and can be

costly. (to supposedly rest GI systems). function and decrease bacterial

❏ Villous atrophy occurs within hours translocation.

nutritional of discontinuing oral alimentation ■ Easy-to-place tubes (eg, esophagos-

■ Nutritional supplementation is para- and may prolong recovery if not tomy tubes) are well tolerated, allow

mount to recovery. addressed early. enteral nutrition, and are associated

■ Little evidence supports outdated ■ Early enteral nutrition is often well with few complications.

therapies involving no PO food or tolerated with few complications. ❏ Nasogastric tubes allow aspiration

water in patients with pancreatitis ❏ This may improve gut barrier

MORE

October 2013 • clinician’s brief 85

Consultant on Call

Nasogastric tube sutured to the nasal philtrum (A) and to the skin ventral to the antiemetics, pain medication): $

3 zygomatic arch (B). ■ Mild-to-moderate cases may require

hospitalization with IV fluids and

pain medication, management with

a temporary feeding tube, or IV

nutrition: $$$$

■ Severe cases (eg, biliary obstruction,

pancreatic neoplasia, abscessation)

may require surgical intervention:

$$$$$

❏ Severe cases can develop secondary

systemic consequences, as pancre-

atitis is an inciting cause of SIRS

and may require multiple days in

a B hospital with aggressive supportive

care: $$$$$

of gastric contents, which may surgical

decrease nausea and vomiting and ■ Surgical treatment is rarely indicated Cost Key

help prevent aspiration pneumonia but may be necessary if the diagnosis $ = up to $100

(Figures 2, previous page, and 3). is unclear or in patients that develop $$ = $101–$250

❏ Trickle feeding theoretically helps extrahepatic biliary obstruction, pan- $$$ = $251–$500

bypass cephalic, gastric, and intes- creatic abscessation, or peritoneal $$$$ = $501–$1000

tinal phases of pancreatic secretion. sepsis or that deteriorate despite $$$$$ = more than $1000

❏ Nasoesophageal tube feeding is aggressive therapy (Figure 4).

an alternative but does not allow ■ Surgical procedures may include

gastric suctioning. pancreatic or peritoneal lavage, Prognosis

❏ Jejunal or gastrostomy tubes require ■ Prognosis for both acute and chronic

debridement of necrotic tissue,

endoscopy or surgery to place and drainage, partial pancreatectomy, pancreatitis is good.

may be more expensive but should be ❏ Severe cases can lead to euthana-

and placement of a feeding tube.

considered for surgical intervention. sia because of cost or because of

*

■ Total parenteral nutrition may provide In General multiple-organ failure, sepsis, SIRS,

adequate calories and be useful in ARDS, and DIC (all rare).

select cases but requires strict aseptic relative Cost

delivery and does not promote GI ■ Many patients can be managed with

Future Considerations

(villous) recovery. ■ Clients should be informed that

outpatient therapy (eg, SC fluids,

pancreatitis is on a continuum;

patients may have chronic pancreatitis

or intermittent bouts of acute pancre-

atitis that require long-term manage-

Surgical explora- ment.

tion of a dog with a

■ Chronic or recurrent acute on chronic

pancreatic abscess

(arrow); note the pancreatitis may result in systemic

diffuse moderate consequences (eg, exocrine pancreatic

erythema/peritonitis

insufficiency, diabetes mellitus from

pancreatic fibrosis). ■ cb

See Aids & Resources, back page, for

references & suggested reading.

ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome,

4 DIC = disseminated intravascular coagulation,

SIRS = systemic inflammatory response syndrome

86 cliniciansbrief.com • October 2013

You might also like

- Rise of The Runelords (RotRL) D&D 5e ConversionDocument12 pagesRise of The Runelords (RotRL) D&D 5e Conversionhmareid100% (2)

- Case Scenario For Community Health NursingDocument5 pagesCase Scenario For Community Health Nursinghemihema100% (1)

- Patient Name Doctor Name Pat Reg Id Sample Collected Date SEX Reporting Date AGE Sample Id ReportstatusDocument2 pagesPatient Name Doctor Name Pat Reg Id Sample Collected Date SEX Reporting Date AGE Sample Id ReportstatusThushar P kumarNo ratings yet

- Ayurveda On The Cusp of ChangeDocument24 pagesAyurveda On The Cusp of ChangeHemal Majithia100% (2)

- Feline Pancreatitis: ProfileDocument5 pagesFeline Pancreatitis: ProfileMiruna ChiriacNo ratings yet

- Chapter 31 - Nausea and VomitingDocument7 pagesChapter 31 - Nausea and Vomitingjonalyn.mejellanoNo ratings yet

- Understanding Medical Surgical Nursing - 0831-0831Document1 pageUnderstanding Medical Surgical Nursing - 0831-0831Anas TasyaNo ratings yet

- Causes and Treatment of Nausea and Vomiting: Aaron Bhakta and Rishi GoelDocument7 pagesCauses and Treatment of Nausea and Vomiting: Aaron Bhakta and Rishi GoelVini SasmitaNo ratings yet

- Disorder of The Pancreas and DMDocument27 pagesDisorder of The Pancreas and DMJoshoua MalanaNo ratings yet

- By DR.: Haitham Mokhtar Mohamed Abd AllahDocument101 pagesBy DR.: Haitham Mokhtar Mohamed Abd AllahMohamed ElkadyNo ratings yet

- Esophageal DisordersDocument37 pagesEsophageal DisordersDanielle FosterNo ratings yet

- Acute PancreatitisDocument12 pagesAcute Pancreatitissho bartNo ratings yet

- 13 Pancreatisis - FinalDocument34 pages13 Pancreatisis - FinalBrhanu belayNo ratings yet

- Feline Hepatic Lipidosis: How I TreatDocument8 pagesFeline Hepatic Lipidosis: How I TreatDavid OliveraNo ratings yet

- GI ReviewDocument44 pagesGI Reviews129682No ratings yet

- 3rd-Yr Revalida NotesDocument9 pages3rd-Yr Revalida NotesJazel RomanoNo ratings yet

- Pead 3 - Abdominal Pain and VommitingDocument22 pagesPead 3 - Abdominal Pain and Vommitingbbyes100% (1)

- Gastritis: Department of Gastroenterology General Hospital of Ningxia Medical University Si Cen MDDocument82 pagesGastritis: Department of Gastroenterology General Hospital of Ningxia Medical University Si Cen MDAvi Themessy100% (1)

- Lecture 1part 2Document50 pagesLecture 1part 2mashe1No ratings yet

- HematuriaDocument37 pagesHematuriaعبدالحكيم عمر عامر بن الزوعNo ratings yet

- PancreatitisDocument6 pagesPancreatitisreerwrr qeqweNo ratings yet

- Articulo Abdomen AgudoDocument12 pagesArticulo Abdomen AgudoAlejandra VelezNo ratings yet

- Surgery 2014.1Document25 pagesSurgery 2014.1Jayanti Neogi SardarNo ratings yet

- Acute Pancreatitis by Yuvaraj BSC Nursing Sec YearDocument9 pagesAcute Pancreatitis by Yuvaraj BSC Nursing Sec Yearvidhyasagar754No ratings yet

- Acute Glomerulonep Hritis: By: Edelrose D. Lapitan BSN Iii-CDocument29 pagesAcute Glomerulonep Hritis: By: Edelrose D. Lapitan BSN Iii-CEdelrose Lapitan100% (1)

- Nursing Care Plan For Inflammatory Bowel DiseaseDocument17 pagesNursing Care Plan For Inflammatory Bowel DiseaseLyka Joy DavilaNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis-Medicine-PancreatitisDocument39 pagesCase Analysis-Medicine-PancreatitisAleks MendozaNo ratings yet

- Pancreatitispptnitinm1st 181229090413Document58 pagesPancreatitispptnitinm1st 181229090413enam professorNo ratings yet

- Acute PancreatitisDocument11 pagesAcute Pancreatitispeter_soósNo ratings yet

- Salmonella, Campylobacter, and Mycobacterium TuberculosisDocument2 pagesSalmonella, Campylobacter, and Mycobacterium TuberculosisMalueth AnguiNo ratings yet

- Disorders of The StomachDocument26 pagesDisorders of The StomachAnnie Rose Dorothy MamingNo ratings yet

- Diarrhoea - MRCEM SuccessDocument7 pagesDiarrhoea - MRCEM SuccessGazi Sareem Bakhtyar AlamNo ratings yet

- Chronic PancreatitisDocument174 pagesChronic Pancreatitisdilekamunasinghe4No ratings yet

- Acute PancreatitisDocument25 pagesAcute PancreatitisSunil YadavNo ratings yet

- NCM 109 Maternal Lecture Lesson: CausesDocument2 pagesNCM 109 Maternal Lecture Lesson: CausesJanelle ArcillaNo ratings yet

- +nephrotic SyndromeDocument22 pages+nephrotic SyndromeDr. SAMNo ratings yet

- ConstipationDocument37 pagesConstipationHero StoreNo ratings yet

- Curs 2-3 2023Document115 pagesCurs 2-3 2023Andreea GuraliucNo ratings yet

- Mesay - Acute PancreatitisDocument67 pagesMesay - Acute PancreatitisMesay AssefaNo ratings yet

- Anorexia: Basic InformationDocument34 pagesAnorexia: Basic InformationcarlosNo ratings yet

- Pancreatitis PresentationDocument41 pagesPancreatitis Presentationak2621829No ratings yet

- Gastro Esophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)Document7 pagesGastro Esophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)MahaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 42: Nursing Management: Upper Gastrointestinal ProblemsDocument10 pagesChapter 42: Nursing Management: Upper Gastrointestinal ProblemsjefrocNo ratings yet

- Askep PankreatitisDocument48 pagesAskep PankreatitisYeni DwiNo ratings yet

- Acute Pancreatitis-A Clinical Update: Review ArticleDocument6 pagesAcute Pancreatitis-A Clinical Update: Review ArticleDương Ngọc DiệpNo ratings yet

- Approach To Vomiting: DR Vivek JhaDocument23 pagesApproach To Vomiting: DR Vivek JhaMukesh ThakurNo ratings yet

- Acute PancreatitisDocument2 pagesAcute PancreatitisChika JonesNo ratings yet

- Diseases of The Stomach:-ObjectivesDocument14 pagesDiseases of The Stomach:-Objectiveshussain AltaherNo ratings yet

- PancreatitisDocument18 pagesPancreatitisDr.Gutale AlmuqdishawiNo ratings yet

- Nur 322 Gi DisordersDocument113 pagesNur 322 Gi DisordersLovelights ZamoraNo ratings yet

- Study Guide 2 Management of Patients With Gastric, Intestinal and Colonic DisordersDocument19 pagesStudy Guide 2 Management of Patients With Gastric, Intestinal and Colonic DisordersKc Cabanilla LizardoNo ratings yet

- Hepatomegaly PDFDocument9 pagesHepatomegaly PDFKhadija IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Esophageal and Stomach Pathology-May+2019Document71 pagesEsophageal and Stomach Pathology-May+2019Karami Brutus0% (1)

- Problem 2 GI - VICKA AZWITADocument65 pagesProblem 2 GI - VICKA AZWITARana RickNo ratings yet

- Approach To The Infant or Child With Nausea and Vomiting - UpToDateDocument47 pagesApproach To The Infant or Child With Nausea and Vomiting - UpToDatemayteveronica1000No ratings yet

- Crohn's DiseaseDocument8 pagesCrohn's DiseaseShannen Madrid Tindugan100% (1)

- The Diseases of The PancreasDocument40 pagesThe Diseases of The PancreasAroosha IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Farmakologi Gastroenterohepatologi S1 FK Umi 09 June 2021Document23 pagesFarmakologi Gastroenterohepatologi S1 FK Umi 09 June 2021Fkumi 2019No ratings yet

- Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome - CASTILLO BELMARKDocument4 pagesZollinger-Ellison Syndrome - CASTILLO BELMARKBelmark CastilloNo ratings yet

- Sa Jun 2018 PDFDocument6 pagesSa Jun 2018 PDFdpcamposhNo ratings yet

- Printout Fever and Abd Pain - Causes and DiagnosiDocument10 pagesPrintout Fever and Abd Pain - Causes and DiagnosiMalar MannanNo ratings yet

- Nurseslabs Gi Diseases Nursing Quiz 4Document6 pagesNurseslabs Gi Diseases Nursing Quiz 4Yenny PepitoNo ratings yet

- Dysphagia, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandDysphagia, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Treatment And Related ConditionsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Diagnosis and TreatmentFrom EverandAcute Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Diagnosis and TreatmentKaren E. KimNo ratings yet

- Hammond Pierce 2023 Treatment of High Output Cardiac Failure Secondary To Anemia in Three CatsDocument5 pagesHammond Pierce 2023 Treatment of High Output Cardiac Failure Secondary To Anemia in Three CatsLorena TomoiagăNo ratings yet

- Sample ID Patient ID Name Test Date & Time 00518 2343 Susi 04 Mar. 2022 14:11 Mode Doctor Sex 360018736 Female LT CatDocument1 pageSample ID Patient ID Name Test Date & Time 00518 2343 Susi 04 Mar. 2022 14:11 Mode Doctor Sex 360018736 Female LT CatLorena TomoiagăNo ratings yet

- Sample ID Patient ID Name Test Date & Time 00514 1958 Smilla 03 Mar. 2022 12:09 Mode Doctor Sex 360018736 Female DogDocument1 pageSample ID Patient ID Name Test Date & Time 00514 1958 Smilla 03 Mar. 2022 12:09 Mode Doctor Sex 360018736 Female DogLorena TomoiagăNo ratings yet

- Sample ID Patient ID Name Test Date & Time 00512 2334 DOM 02 Mar. 2022 21:59 Mode Doctor Sex 360018736 Male Florin B DogDocument1 pageSample ID Patient ID Name Test Date & Time 00512 2334 DOM 02 Mar. 2022 21:59 Mode Doctor Sex 360018736 Male Florin B DogLorena TomoiagăNo ratings yet

- Sample ID Patient ID Name Test Date & Time 00515 2337 Ruru 03 Mar. 2022 13:46 Mode Doctor Sex 360018736 Female LT DogDocument1 pageSample ID Patient ID Name Test Date & Time 00515 2337 Ruru 03 Mar. 2022 13:46 Mode Doctor Sex 360018736 Female LT DogLorena TomoiagăNo ratings yet

- Chemical Coordination and Integration Handwriten Notes For Neet and JeeDocument5 pagesChemical Coordination and Integration Handwriten Notes For Neet and JeetechnosonicindiaNo ratings yet

- My LogDocument229 pagesMy Logsowpij290laslNo ratings yet

- Applying What We Know To Accelerate Cancer PreventionDocument10 pagesApplying What We Know To Accelerate Cancer PreventionSt. Louis Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Group 2 Case Study MergedDocument12 pagesGroup 2 Case Study MergedKobe Bryan GermoNo ratings yet

- Anatomy by DR Naser AlBarbariDocument24 pagesAnatomy by DR Naser AlBarbariTanmay JhulkaNo ratings yet

- Describe An Unpopular Opinion You Hold or HaveDocument4 pagesDescribe An Unpopular Opinion You Hold or Have091945029No ratings yet

- Latest Thesis. Rough Print12Document107 pagesLatest Thesis. Rough Print12Ajmal Hussain100% (1)

- Natural Aromatase InhibitorsDocument69 pagesNatural Aromatase InhibitorsIme Muško OsječkoNo ratings yet

- 2000+ MCQS With Solution: of Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Maths & EnglishDocument169 pages2000+ MCQS With Solution: of Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Maths & EnglishMuhammad UmairNo ratings yet

- Adolescence: Biosocial Development: The Developing Person Through AdolescenceDocument46 pagesAdolescence: Biosocial Development: The Developing Person Through AdolescenceHUMSS 12ANo ratings yet

- Final Research Essay DropboxDocument12 pagesFinal Research Essay Dropboxapi-584319388No ratings yet

- Hello Health, Goodbye Gray: Leslie KennyDocument9 pagesHello Health, Goodbye Gray: Leslie KennyfizzNo ratings yet

- Bronchial Asthma QuestionsDocument44 pagesBronchial Asthma QuestionsguevarrajanelleruthNo ratings yet

- Lecture 29 30 Thyroid TherapeuticsDocument3 pagesLecture 29 30 Thyroid TherapeuticsAhmed MashalyNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 IncidenceDocument12 pagesLesson 3 IncidenceKaren RamirezNo ratings yet

- Psy 2300 Exam ReviewDocument101 pagesPsy 2300 Exam Reviewerica1960No ratings yet

- Rajiv Gandhi College of Nursing BSC Nursing 1St Year 2020 Fundamental of Nursing Pathology SetbDocument3 pagesRajiv Gandhi College of Nursing BSC Nursing 1St Year 2020 Fundamental of Nursing Pathology SetbNeenu RajputNo ratings yet

- The Anxiety Symptoms Among Chronic Kidney Disease Patients Who Undergo Hemodialysis TherapyDocument5 pagesThe Anxiety Symptoms Among Chronic Kidney Disease Patients Who Undergo Hemodialysis TherapyIJPHSNo ratings yet

- Cervical Cancer in PregnancyDocument21 pagesCervical Cancer in Pregnancymineresearch100% (1)

- Aktiviti Latihan Terapi AirDocument2 pagesAktiviti Latihan Terapi Airas-suhairiNo ratings yet

- StemBook 2011 FinalDocument187 pagesStemBook 2011 Finalskeebs23No ratings yet

- 10 Larva MigransDocument8 pages10 Larva MigransDaniel JohnsonNo ratings yet

- EtatDocument121 pagesEtatBhoja Raj GAUTAMNo ratings yet

- The Stolen Bacillus and Other Incidents by Wells, H. G. (Herbert George), 1866-1946Document127 pagesThe Stolen Bacillus and Other Incidents by Wells, H. G. (Herbert George), 1866-1946Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- English10 q4 CLAS3 Giving The Expanded Extended Definition of Words Final-Carissa-CalalinDocument13 pagesEnglish10 q4 CLAS3 Giving The Expanded Extended Definition of Words Final-Carissa-CalalinSophia Erika LargoNo ratings yet

- (Livestock Health Ii (Livestock Parasites)Document5 pages(Livestock Health Ii (Livestock Parasites)Brian BrianNo ratings yet