Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 viewsConsumer Behaviour: Part 7: Consumer Decision Making (Ch. 9 & 10)

Consumer Behaviour: Part 7: Consumer Decision Making (Ch. 9 & 10)

Uploaded by

Erik CarlströmThis document discusses consumer decision making and how choices can be simplified. It notes that people face many choices but have limited cognitive resources, so they may opt out or use heuristics. Providing too many choices can increase stress and lead consumers to focus on attributes like price. The document recommends helping consumers narrow options and reach a decision threshold before fatigue sets in. It also discusses how nudges and default options can guide choices but may backfire if people feel manipulated.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Report On Reckitt BenchiserDocument26 pagesReport On Reckitt Benchiserprotonpranav77% (13)

- Consumer MarketingDocument9 pagesConsumer MarketingatlcelebrityNo ratings yet

- Ahead of the Curve: Using Consumer Psychology to Meet Your Business GoalsFrom EverandAhead of the Curve: Using Consumer Psychology to Meet Your Business GoalsNo ratings yet

- Hooked (Review and Analysis of Eyal and Hoover's Book)From EverandHooked (Review and Analysis of Eyal and Hoover's Book)No ratings yet

- Absolute Value: What Really Influences Customers in the Age of (Nearly) Perfect InformationFrom EverandAbsolute Value: What Really Influences Customers in the Age of (Nearly) Perfect InformationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- Differentiate or Die (Review and Analysis of Trout and Rivkin's Book)From EverandDifferentiate or Die (Review and Analysis of Trout and Rivkin's Book)No ratings yet

- Sonali Vitha IdpDocument4 pagesSonali Vitha Idpapi-549475006No ratings yet

- Conduct DisorderDocument11 pagesConduct Disorderleftbysanity100% (2)

- Customer Service ESL WorksheetDocument4 pagesCustomer Service ESL WorksheetPatricia Maia50% (2)

- Thomas GordonDocument3 pagesThomas GordonDzairi Azmeer67% (3)

- Williams How Do Consumers Really Do DecisionsDocument9 pagesWilliams How Do Consumers Really Do Decisionsallan61No ratings yet

- Conceptual: Session 1Document101 pagesConceptual: Session 1Advaita NGONo ratings yet

- Course SummaryDocument4 pagesCourse SummarymargaridamgalvaoNo ratings yet

- By DR - Genet Gebre: 5. Consumer Decision Making Process (Mbam 641)Document32 pagesBy DR - Genet Gebre: 5. Consumer Decision Making Process (Mbam 641)Legesse Gudura MamoNo ratings yet

- WARC Article What We Know About Consumer Decision MakingDocument8 pagesWARC Article What We Know About Consumer Decision MakingAngira BiswasNo ratings yet

- Consumer BehaviourDocument18 pagesConsumer BehaviourMituj - Vendor ManagementNo ratings yet

- Project On Small Car Marketing-NanoDocument84 pagesProject On Small Car Marketing-NanoMohammed YunusNo ratings yet

- Consumer Decision-MakingDocument3 pagesConsumer Decision-MakingaccaliaNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour and Rural Marketing AssignmentDocument15 pagesConsumer Behaviour and Rural Marketing Assignmentjainpiyush_1909No ratings yet

- Summary 7Document4 pagesSummary 797zds2kpbcNo ratings yet

- Consumer Decision MakingDocument3 pagesConsumer Decision Makingvipinpsrt7706No ratings yet

- Consumer Behavior PP Chapter 9Document23 pagesConsumer Behavior PP Chapter 9tuongvyvy100% (1)

- A Study On The Impact of Advertisement in Taking Buying Decision by ConsumerDocument44 pagesA Study On The Impact of Advertisement in Taking Buying Decision by Consumeralok006100% (2)

- Consumer Behavior Dissertation PDFDocument8 pagesConsumer Behavior Dissertation PDFHelpWritingAPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Chapter 9&10Document13 pagesChapter 9&10uyenle.31221024325No ratings yet

- Ôn CBehaviorDocument8 pagesÔn CBehaviortruyenhtk22No ratings yet

- World of Marketing - Module 3 - BookletDocument43 pagesWorld of Marketing - Module 3 - BookletGift SimauNo ratings yet

- (Chap 9) Consumer BehaviourDocument10 pages(Chap 9) Consumer BehaviourNGA MAI QUYNHNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Buyers Decision Making ProcessDocument7 pagesAssignment On Buyers Decision Making ProcessPooja Dubey100% (1)

- A) Law of Diminishing Marginal UtilityDocument5 pagesA) Law of Diminishing Marginal UtilityRACSO elimuNo ratings yet

- The Buying Decision ProcessDocument4 pagesThe Buying Decision ProcessAbdullah FaisalNo ratings yet

- CB Assignment01Document8 pagesCB Assignment01Hira RazaNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature of Consumer Buying BehaviorDocument6 pagesReview of Related Literature of Consumer Buying BehaviorafmzwrhwrwohfnNo ratings yet

- Commentaries On Katona, "Psychology and Consumer Economics"Document7 pagesCommentaries On Katona, "Psychology and Consumer Economics"Rupesh JainNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Consumer BehaviorDocument4 pagesDissertation Consumer BehaviorWritingServicesForCollegePapersSingapore100% (1)

- Factors Affecting Consumer Buying BehaviourDocument12 pagesFactors Affecting Consumer Buying BehaviourAsghar ALiNo ratings yet

- 7, NotesDocument8 pages7, Notesdenise borisadeNo ratings yet

- 08 销售策展悖论Document1 page08 销售策展悖论frejasong11No ratings yet

- Consumer Decision Making ProcessDocument9 pagesConsumer Decision Making ProcessKhudadad NabizadaNo ratings yet

- UCI Mod 3Document32 pagesUCI Mod 3sajalNo ratings yet

- PrateeshPChandra 20121120Document18 pagesPrateeshPChandra 20121120PRATEESH P CHANDRA 20121120No ratings yet

- 5 Tips For Consumer Choice Models - by Isha Gupta - Towards Data ScienceDocument9 pages5 Tips For Consumer Choice Models - by Isha Gupta - Towards Data SciencewegwerfNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour Assignment-2: Submitted To Prof. Anupam NarulaDocument15 pagesConsumer Behaviour Assignment-2: Submitted To Prof. Anupam NarulaAmansapraSapraNo ratings yet

- BBBBDocument57 pagesBBBBAkila ganesanNo ratings yet

- Part A: Cottle Taylor: Expanding The Oral Care Group in IndiaDocument14 pagesPart A: Cottle Taylor: Expanding The Oral Care Group in Indiashivani khareNo ratings yet

- Research Challenges in Recommender Systems: 1 Modest GoalsDocument4 pagesResearch Challenges in Recommender Systems: 1 Modest Goalsazertytyty000No ratings yet

- Consumer BehaviorDocument8 pagesConsumer Behaviortaco222No ratings yet

- BBBBDocument57 pagesBBBBAkila ganesanNo ratings yet

- Assignment ECS804 MISDocument6 pagesAssignment ECS804 MISAyush jainNo ratings yet

- BE 3 FinalDocument9 pagesBE 3 Finalchandru.v5210No ratings yet

- The Consumer Decision Making Process: Chapter-4Document23 pagesThe Consumer Decision Making Process: Chapter-4akmohideenNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behavior Decision Process: What Is Decision MakingDocument14 pagesConsumer Behavior Decision Process: What Is Decision Makinggul_e_sabaNo ratings yet

- Note CNSMR BhvirDocument19 pagesNote CNSMR Bhvirdominic3586No ratings yet

- InnovationDocument25 pagesInnovationolmezestNo ratings yet

- Consumer Decision Making Process (Reference)Document9 pagesConsumer Decision Making Process (Reference)May Oo LayNo ratings yet

- Modelf Consumer BehaviorDocument3 pagesModelf Consumer BehaviormadhurendrahraNo ratings yet

- 6 Guidelines For Structured Decision Making by ECDocument9 pages6 Guidelines For Structured Decision Making by ECMarcelo Bernardino AraújoNo ratings yet

- (CONSUMER BEHAVIOR) How To Market at Each Stage of The Buying Decision Process Using The Howard Sheth ModelDocument15 pages(CONSUMER BEHAVIOR) How To Market at Each Stage of The Buying Decision Process Using The Howard Sheth ModelSidharth KumarNo ratings yet

- Consumer Decisiion MakingDocument4 pagesConsumer Decisiion MakingJitendra SinghNo ratings yet

- Note On Consumer Behavior: John R. HauserDocument18 pagesNote On Consumer Behavior: John R. HauserAKNo ratings yet

- Cheat SheetDocument14 pagesCheat SheetBlauman074No ratings yet

- Consumer Decision Making Module 5Document15 pagesConsumer Decision Making Module 5abhishekmalusare07No ratings yet

- The New Positioning (Review and Analysis of Trout and Rivkin's Book)From EverandThe New Positioning (Review and Analysis of Trout and Rivkin's Book)No ratings yet

- The Change Function (Review and Analysis of Coburn's Book)From EverandThe Change Function (Review and Analysis of Coburn's Book)No ratings yet

- The 24-Hour Customer (Review and Analysis of Ott's Book)From EverandThe 24-Hour Customer (Review and Analysis of Ott's Book)No ratings yet

- Hva Ting Betyr I Spss ObligDocument2 pagesHva Ting Betyr I Spss ObligErik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- Descriptive Statistics: Vacation Type: OccupationDocument7 pagesDescriptive Statistics: Vacation Type: OccupationErik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- International Business Kompendie Ord Og SpørsmålDocument93 pagesInternational Business Kompendie Ord Og SpørsmålErik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour: Part 2: Perception (Chapter 3)Document46 pagesConsumer Behaviour: Part 2: Perception (Chapter 3)Erik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour: Part 3: Learning and Memory (Chapter 4)Document36 pagesConsumer Behaviour: Part 3: Learning and Memory (Chapter 4)Erik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- 5 Personality SelfDocument37 pages5 Personality SelfErik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- Teori Og Begreper ForbrukeratferdDocument11 pagesTeori Og Begreper ForbrukeratferdErik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- Øving BA 2Document12 pagesØving BA 2Erik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology in Information Technology: Dr. Naji Shukri AlzazaDocument45 pagesResearch Methodology in Information Technology: Dr. Naji Shukri Alzazamuhammed100% (1)

- Conceptual and Operational DefinitionsDocument7 pagesConceptual and Operational DefinitionsLDRRMO RAMON ISABELANo ratings yet

- Level 3 Supervisor Lesson Plan 1Document5 pagesLevel 3 Supervisor Lesson Plan 1api-322204740No ratings yet

- I. Objectives: Grade 11 DLPDocument4 pagesI. Objectives: Grade 11 DLPJomar MacapagalNo ratings yet

- Get The Edge Day 1 SessionDocument9 pagesGet The Edge Day 1 Sessionjordansiegel1984100% (1)

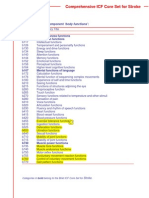

- Comprehensive and Brief ICF Core Sets Stroke1Document4 pagesComprehensive and Brief ICF Core Sets Stroke1robins kumarNo ratings yet

- Functions of CommunicationDocument1 pageFunctions of CommunicationMohitNo ratings yet

- Effective Time Management and Avoiding Procrastination LeafletDocument4 pagesEffective Time Management and Avoiding Procrastination LeafletOnerous ChimsNo ratings yet

- Charismatic and Transformational LeadershipDocument12 pagesCharismatic and Transformational LeadershipTejas DesaiNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Year 5 EnglishDocument5 pagesLesson Plan Year 5 EnglishMuhd HirdziNo ratings yet

- VdV2020 VygotskystheoryDocument7 pagesVdV2020 VygotskystheoryAndrés Santamaría AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Shaping Customer Satisfaction Through SelfDocument17 pagesShaping Customer Satisfaction Through SelfArief AccountingSASNo ratings yet

- Acculturation ModelDocument17 pagesAcculturation ModelLibagon National High School (Region VIII - Southern Leyte)No ratings yet

- Raksha Karki: Career ObjectiveDocument2 pagesRaksha Karki: Career ObjectiveKumar SonalNo ratings yet

- Assessing A Couple Relationship and Compatibility Using MARI Card Test and Mandala DrawingDocument7 pagesAssessing A Couple Relationship and Compatibility Using MARI Card Test and Mandala DrawingkarinadapariaNo ratings yet

- T H E Metaphysics of Brain Death: Jeff McmahanDocument36 pagesT H E Metaphysics of Brain Death: Jeff McmahandocsincloudNo ratings yet

- Conducting A Brainstorming Session ChecklistDocument4 pagesConducting A Brainstorming Session ChecklistNilesh KurleNo ratings yet

- Scenario Based Learning - PappasDocument25 pagesScenario Based Learning - PappasCreators CollegeNo ratings yet

- E F CarritDocument7 pagesE F CarritAnonymous lviObMpprNo ratings yet

- The Role of Symbol in A Streetcar Named DesireDocument7 pagesThe Role of Symbol in A Streetcar Named DesireDebdeep RoyNo ratings yet

- SUBIECT PENTRU OLIMPIADA DE LIMBA ENGLEZĂ - ETAPA LOCALĂ - Manuela PanescuDocument6 pagesSUBIECT PENTRU OLIMPIADA DE LIMBA ENGLEZĂ - ETAPA LOCALĂ - Manuela PanescuAdoptedchildNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Inclusive Education: Click For UpdatesDocument15 pagesInternational Journal of Inclusive Education: Click For UpdatesfadhNo ratings yet

- The Brand Safety Effect CHEQ Magna IPG Media LabDocument21 pagesThe Brand Safety Effect CHEQ Magna IPG Media LabAndres NietoNo ratings yet

- Qualitative-Research 111419Document11 pagesQualitative-Research 111419Cristian Rey AbalaNo ratings yet

- Song LyricsDocument1 pageSong LyricsRegina AbacNo ratings yet

Consumer Behaviour: Part 7: Consumer Decision Making (Ch. 9 & 10)

Consumer Behaviour: Part 7: Consumer Decision Making (Ch. 9 & 10)

Uploaded by

Erik Carlström0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views31 pagesThis document discusses consumer decision making and how choices can be simplified. It notes that people face many choices but have limited cognitive resources, so they may opt out or use heuristics. Providing too many choices can increase stress and lead consumers to focus on attributes like price. The document recommends helping consumers narrow options and reach a decision threshold before fatigue sets in. It also discusses how nudges and default options can guide choices but may backfire if people feel manipulated.

Original Description:

Original Title

7 Decision Making

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document discusses consumer decision making and how choices can be simplified. It notes that people face many choices but have limited cognitive resources, so they may opt out or use heuristics. Providing too many choices can increase stress and lead consumers to focus on attributes like price. The document recommends helping consumers narrow options and reach a decision threshold before fatigue sets in. It also discusses how nudges and default options can guide choices but may backfire if people feel manipulated.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views31 pagesConsumer Behaviour: Part 7: Consumer Decision Making (Ch. 9 & 10)

Consumer Behaviour: Part 7: Consumer Decision Making (Ch. 9 & 10)

Uploaded by

Erik CarlströmThis document discusses consumer decision making and how choices can be simplified. It notes that people face many choices but have limited cognitive resources, so they may opt out or use heuristics. Providing too many choices can increase stress and lead consumers to focus on attributes like price. The document recommends helping consumers narrow options and reach a decision threshold before fatigue sets in. It also discusses how nudges and default options can guide choices but may backfire if people feel manipulated.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 31

MF-205 Consumer Behaviour

Part 7: Consumer decision making (Ch. 9 & 10)

Dr Michal Krol

The Problem of Choice

We make a lot of choices every day, but consumer product choices are hard,

in that there are usually many alternatives, each characterised by several

attributes.

Faced with too many choices under a time

or cognitive resource constraint, many

people prefer to opt out (hyper- or

overchoice).

The optimal number of choices depends on

the product’s importance vs. complexity.

The Problem of Choice

Hyperchoice may not only increase

the stress and dissatisfaction of

consumers, but also increase the

likelihood that they might revert to

heuristics that are undesirable from

the sellers’ perspective, like

focusing on the price.

Thus, it is crucial to simplify the

consumer’s choice process!

The Cognitive Model of

Consumer Decision-Making

• People with a moderate level of product

knowledge exert most effort when

choosing.

• Experts know what to focus on and engage

in selective search and evaluation (narrow

attribute consideration sets).

• Novices rely on heuristics and the

opinions of others.

Simplifying the choice

According to sequential sampling, attentional drift-diffusion models of choice,

information is sampled until a decision threshold is reached.

It is important to help consumers to

narrow down the search, so that

they can accummulate enough

evidence on any single alternative,

or to nudge them towards the

threshold before decision fatigue

sets in.

The frames are made of plastic, which is why they are

very comfortable and more resistant to damage than

metal frames. Thanks to the the material they are made

of, they are much more expressive than metal frames.

The frames are made of metal, so are very light and

more comfortable than plastic frames. Metal frames are

chosen by men, as they express professionalism and

elegance, and are more subtle than plastic ones.

• Google helps people narrow down the search by ranking the results by

relevance. This is what makes search engine optimization so important for

firms.

• Similarly, product categorization is crucial: it is

best if the product can fit into several narrow

categories.

• The downside is that it is then harder to identify the

full set of potentially very different competitors.

• It is also harder for a multi-category product to

become a category exemplar.

The 'Save More Tomorrow' (SMarT) program

Interestingly, people often overestimate their ability to exert a choice effort

in the future, and underestimate their propensity for inertia.

Benartzi & Thaler (2004) asked workers to

join a saving scheme where part of their

next wage increase would be

automatically saved (it would be possible

to opt out at any time).

Savings quadrupled compared with asking

to save part of the existing wage.

from the FAQ section:

Why do I need a payment method to

start a free trial?

We ask for a payment method to ensure

you don't have any interruption in

service after the free trial.

Decision rules

Under high cognitive involvement, people follow compensatory decision

rules.

The fact that the product scores high (is

good) on some attribute dimensions

can compensate for the fact that scores

low (is bad) on others.

Attributes can be weighted in terms of

their relative importance.

Noncompensatory rules

• lexicographic: choose the product that is best

in terms of the most important attribute; in

case of a tie move to the next most

important attribute

• elimination-by-aspects: eliminate all

products that do not meet a specific cutoff

point on the most important attribute, then

move on to the next one

• conjunctive: pick a product that meets all

specified cutoff points across all attributes

Heuristics

Under low cognitive involvement, we may opt for

satisficing solutions, based on simple (System 1)

heuristics, in order to preserve cognitive

resources.

E.g., a common heuristic is to choose the same

product as usual (habitual decision making).

This form of inertia differs from brand loyalty, which

would entail choosing the brand even if that means

„Perfect is the enemy of good.”

more effort. Voltaire

A list of common market beliefs

(compiled in 1990)

Generic heuristics affecting consumer decisions...

I. Context effects: whereby the preference between options A

and B depends on what other options are present;

an example of this is the decoy effect, where an

inferior decoy increases preference for the

target it is superior to.

In fact, even an unavailable

(„phantom”) decoy works.

Generic heuristics affecting consumer decisions...

I. Context effects: a closely related phenomenon is the

compromise effect, where and option is popular as a

compromise between two

extreme options

e.g., iPhone 8 vs. 8+ vs. iPhone X

Generic heuristics affecting consumer decisions...

II. Loss aversion: whereby losing something (relative to the

expected status quo) is felt more strongly than gaining the

same thing

identified by Amos Tversky

and Daniel Kahneman

(prospect theory)

Generic heuristics affecting consumer decisions...

III. Sunk-cost fallacy: people are more determined to continue an

endeavor once they invested money, effort, or time into it, even if

it would make more sense to pull out.

Generic heuristics affecting consumer decisions...

IV. Confirmation bias:

the tendency to

search for, interpret,

favor, and recall

information in a way

that confirms prior

beliefs.

This means we will not

only seek to validate our

purchase decisions, but

also interpret new

evidence in favour of the

leading alternative prior

to choice.

Generic heuristics affecting consumer decisions...

V. Anchoring: where an initial piece of information forms an „anchor”

for subsequent judgments. Future negotiations, arguments,

estimates, etc. are discussed in relation to the anchor and are

overly dependent on its value.

e.g., in experiments, people estimate that:

1x2x3x4x5x6x7x8 ≈ 512

8x7x6x5x4x3x2x1 ≈ 2250

(actually, both are = 40,320)

AI nudging

The latest trend is to use AI to build chatbots

to interact with customers.

This can not only reduce customer service

costs, but the bots can potentially get much

better at reading customer behaviour

patterns and exploiting the humans’

heuristics to nudge them.

AI nudging

Though existing applications are quite primitive, Google recently built on their

previous, Duplex Assistant project, releasing the Meena chatbot in early 2020.

Meena is an open-domain bot that

doesn’t lose context and stays

meaningful until accomplishing the

task.

It is said to improve on OpenAI’s

GPT-2... but is dwarfed by GPT-3.

Bad news?

As early as 2013, it was already

estimated that AI would replace human

Advertising & Retail Salespeople, as well

as Market Research Analysts and

Marketing Specialists

(https://willrobotstakemyjob.com).

The impact of mood

When in a good mood, we process information in

a less effortful, heuristic manner, with less

attention to specifics. We tend to remain in this

state if allowed to:

• click on an item for a pop-up with more detail

• add the item to cart without leaving the page

• “feel” merchandise through better imagery

• enter all purchase data on one page

• mix and match product images on one page

Mobile shopping apps

Smartphone apps can be a useful decision-support tool, helping users locate

a product in a physical store, learn about it via augmented reality, but also get

targeted alerts (i.e., nudges).

Thus, they can be used by retailers

to stimulate spontaneous

(unplanned / impulse) buying, in

addition to traditional tricks like

placing impulse items at checkout.

The sharing economy

Another way of facilitating decisions (by lowering the decision threshold) is

to allow customers to rent items instead of buying (collaboartive

consumption).

Especially beneficial for items costly to

produce but infrequently used (like power

tools).

Knowing that others used and liked the

item can also reduce the cognitive cost of

information search.

Nudging can backfire

While nudging customers may be tempting, research shows it can also

produce the opposite of the desired behavior when people notice they are

manipulated.

It can also reduce postpurchase

satisfaction via expectancy

disconfirmation.

People will also be less likely to

rationalise a bad „nudge” purchase than

one made under high involvement.

Nudging can backfire

Finally, as usual, nudges can be based on non-replicable research.

E.g., in 2012, researchers showed (?) that when people sign at the START

of a tax form rather than the END, they are more likely to declare their

income truthfully.

Various government agencies have

adopted this practice.

In 2020, the same researchers failed

to replicate the effect.

Nudging can backfire

This can also lead to a perceived lack of social responsibility.

It is increasingly argued that the solution to the waste crisis is not recycling

but a change in consumer habits.

Rather than getting people to buy

products they do not really want,

incentivised nudges can assist in

responsible product disposal.

You might also like

- Report On Reckitt BenchiserDocument26 pagesReport On Reckitt Benchiserprotonpranav77% (13)

- Consumer MarketingDocument9 pagesConsumer MarketingatlcelebrityNo ratings yet

- Ahead of the Curve: Using Consumer Psychology to Meet Your Business GoalsFrom EverandAhead of the Curve: Using Consumer Psychology to Meet Your Business GoalsNo ratings yet

- Hooked (Review and Analysis of Eyal and Hoover's Book)From EverandHooked (Review and Analysis of Eyal and Hoover's Book)No ratings yet

- Absolute Value: What Really Influences Customers in the Age of (Nearly) Perfect InformationFrom EverandAbsolute Value: What Really Influences Customers in the Age of (Nearly) Perfect InformationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- Differentiate or Die (Review and Analysis of Trout and Rivkin's Book)From EverandDifferentiate or Die (Review and Analysis of Trout and Rivkin's Book)No ratings yet

- Sonali Vitha IdpDocument4 pagesSonali Vitha Idpapi-549475006No ratings yet

- Conduct DisorderDocument11 pagesConduct Disorderleftbysanity100% (2)

- Customer Service ESL WorksheetDocument4 pagesCustomer Service ESL WorksheetPatricia Maia50% (2)

- Thomas GordonDocument3 pagesThomas GordonDzairi Azmeer67% (3)

- Williams How Do Consumers Really Do DecisionsDocument9 pagesWilliams How Do Consumers Really Do Decisionsallan61No ratings yet

- Conceptual: Session 1Document101 pagesConceptual: Session 1Advaita NGONo ratings yet

- Course SummaryDocument4 pagesCourse SummarymargaridamgalvaoNo ratings yet

- By DR - Genet Gebre: 5. Consumer Decision Making Process (Mbam 641)Document32 pagesBy DR - Genet Gebre: 5. Consumer Decision Making Process (Mbam 641)Legesse Gudura MamoNo ratings yet

- WARC Article What We Know About Consumer Decision MakingDocument8 pagesWARC Article What We Know About Consumer Decision MakingAngira BiswasNo ratings yet

- Consumer BehaviourDocument18 pagesConsumer BehaviourMituj - Vendor ManagementNo ratings yet

- Project On Small Car Marketing-NanoDocument84 pagesProject On Small Car Marketing-NanoMohammed YunusNo ratings yet

- Consumer Decision-MakingDocument3 pagesConsumer Decision-MakingaccaliaNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour and Rural Marketing AssignmentDocument15 pagesConsumer Behaviour and Rural Marketing Assignmentjainpiyush_1909No ratings yet

- Summary 7Document4 pagesSummary 797zds2kpbcNo ratings yet

- Consumer Decision MakingDocument3 pagesConsumer Decision Makingvipinpsrt7706No ratings yet

- Consumer Behavior PP Chapter 9Document23 pagesConsumer Behavior PP Chapter 9tuongvyvy100% (1)

- A Study On The Impact of Advertisement in Taking Buying Decision by ConsumerDocument44 pagesA Study On The Impact of Advertisement in Taking Buying Decision by Consumeralok006100% (2)

- Consumer Behavior Dissertation PDFDocument8 pagesConsumer Behavior Dissertation PDFHelpWritingAPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Chapter 9&10Document13 pagesChapter 9&10uyenle.31221024325No ratings yet

- Ôn CBehaviorDocument8 pagesÔn CBehaviortruyenhtk22No ratings yet

- World of Marketing - Module 3 - BookletDocument43 pagesWorld of Marketing - Module 3 - BookletGift SimauNo ratings yet

- (Chap 9) Consumer BehaviourDocument10 pages(Chap 9) Consumer BehaviourNGA MAI QUYNHNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Buyers Decision Making ProcessDocument7 pagesAssignment On Buyers Decision Making ProcessPooja Dubey100% (1)

- A) Law of Diminishing Marginal UtilityDocument5 pagesA) Law of Diminishing Marginal UtilityRACSO elimuNo ratings yet

- The Buying Decision ProcessDocument4 pagesThe Buying Decision ProcessAbdullah FaisalNo ratings yet

- CB Assignment01Document8 pagesCB Assignment01Hira RazaNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature of Consumer Buying BehaviorDocument6 pagesReview of Related Literature of Consumer Buying BehaviorafmzwrhwrwohfnNo ratings yet

- Commentaries On Katona, "Psychology and Consumer Economics"Document7 pagesCommentaries On Katona, "Psychology and Consumer Economics"Rupesh JainNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Consumer BehaviorDocument4 pagesDissertation Consumer BehaviorWritingServicesForCollegePapersSingapore100% (1)

- Factors Affecting Consumer Buying BehaviourDocument12 pagesFactors Affecting Consumer Buying BehaviourAsghar ALiNo ratings yet

- 7, NotesDocument8 pages7, Notesdenise borisadeNo ratings yet

- 08 销售策展悖论Document1 page08 销售策展悖论frejasong11No ratings yet

- Consumer Decision Making ProcessDocument9 pagesConsumer Decision Making ProcessKhudadad NabizadaNo ratings yet

- UCI Mod 3Document32 pagesUCI Mod 3sajalNo ratings yet

- PrateeshPChandra 20121120Document18 pagesPrateeshPChandra 20121120PRATEESH P CHANDRA 20121120No ratings yet

- 5 Tips For Consumer Choice Models - by Isha Gupta - Towards Data ScienceDocument9 pages5 Tips For Consumer Choice Models - by Isha Gupta - Towards Data SciencewegwerfNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour Assignment-2: Submitted To Prof. Anupam NarulaDocument15 pagesConsumer Behaviour Assignment-2: Submitted To Prof. Anupam NarulaAmansapraSapraNo ratings yet

- BBBBDocument57 pagesBBBBAkila ganesanNo ratings yet

- Part A: Cottle Taylor: Expanding The Oral Care Group in IndiaDocument14 pagesPart A: Cottle Taylor: Expanding The Oral Care Group in Indiashivani khareNo ratings yet

- Research Challenges in Recommender Systems: 1 Modest GoalsDocument4 pagesResearch Challenges in Recommender Systems: 1 Modest Goalsazertytyty000No ratings yet

- Consumer BehaviorDocument8 pagesConsumer Behaviortaco222No ratings yet

- BBBBDocument57 pagesBBBBAkila ganesanNo ratings yet

- Assignment ECS804 MISDocument6 pagesAssignment ECS804 MISAyush jainNo ratings yet

- BE 3 FinalDocument9 pagesBE 3 Finalchandru.v5210No ratings yet

- The Consumer Decision Making Process: Chapter-4Document23 pagesThe Consumer Decision Making Process: Chapter-4akmohideenNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behavior Decision Process: What Is Decision MakingDocument14 pagesConsumer Behavior Decision Process: What Is Decision Makinggul_e_sabaNo ratings yet

- Note CNSMR BhvirDocument19 pagesNote CNSMR Bhvirdominic3586No ratings yet

- InnovationDocument25 pagesInnovationolmezestNo ratings yet

- Consumer Decision Making Process (Reference)Document9 pagesConsumer Decision Making Process (Reference)May Oo LayNo ratings yet

- Modelf Consumer BehaviorDocument3 pagesModelf Consumer BehaviormadhurendrahraNo ratings yet

- 6 Guidelines For Structured Decision Making by ECDocument9 pages6 Guidelines For Structured Decision Making by ECMarcelo Bernardino AraújoNo ratings yet

- (CONSUMER BEHAVIOR) How To Market at Each Stage of The Buying Decision Process Using The Howard Sheth ModelDocument15 pages(CONSUMER BEHAVIOR) How To Market at Each Stage of The Buying Decision Process Using The Howard Sheth ModelSidharth KumarNo ratings yet

- Consumer Decisiion MakingDocument4 pagesConsumer Decisiion MakingJitendra SinghNo ratings yet

- Note On Consumer Behavior: John R. HauserDocument18 pagesNote On Consumer Behavior: John R. HauserAKNo ratings yet

- Cheat SheetDocument14 pagesCheat SheetBlauman074No ratings yet

- Consumer Decision Making Module 5Document15 pagesConsumer Decision Making Module 5abhishekmalusare07No ratings yet

- The New Positioning (Review and Analysis of Trout and Rivkin's Book)From EverandThe New Positioning (Review and Analysis of Trout and Rivkin's Book)No ratings yet

- The Change Function (Review and Analysis of Coburn's Book)From EverandThe Change Function (Review and Analysis of Coburn's Book)No ratings yet

- The 24-Hour Customer (Review and Analysis of Ott's Book)From EverandThe 24-Hour Customer (Review and Analysis of Ott's Book)No ratings yet

- Hva Ting Betyr I Spss ObligDocument2 pagesHva Ting Betyr I Spss ObligErik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- Descriptive Statistics: Vacation Type: OccupationDocument7 pagesDescriptive Statistics: Vacation Type: OccupationErik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- International Business Kompendie Ord Og SpørsmålDocument93 pagesInternational Business Kompendie Ord Og SpørsmålErik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour: Part 2: Perception (Chapter 3)Document46 pagesConsumer Behaviour: Part 2: Perception (Chapter 3)Erik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour: Part 3: Learning and Memory (Chapter 4)Document36 pagesConsumer Behaviour: Part 3: Learning and Memory (Chapter 4)Erik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- 5 Personality SelfDocument37 pages5 Personality SelfErik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- Teori Og Begreper ForbrukeratferdDocument11 pagesTeori Og Begreper ForbrukeratferdErik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- Øving BA 2Document12 pagesØving BA 2Erik CarlströmNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology in Information Technology: Dr. Naji Shukri AlzazaDocument45 pagesResearch Methodology in Information Technology: Dr. Naji Shukri Alzazamuhammed100% (1)

- Conceptual and Operational DefinitionsDocument7 pagesConceptual and Operational DefinitionsLDRRMO RAMON ISABELANo ratings yet

- Level 3 Supervisor Lesson Plan 1Document5 pagesLevel 3 Supervisor Lesson Plan 1api-322204740No ratings yet

- I. Objectives: Grade 11 DLPDocument4 pagesI. Objectives: Grade 11 DLPJomar MacapagalNo ratings yet

- Get The Edge Day 1 SessionDocument9 pagesGet The Edge Day 1 Sessionjordansiegel1984100% (1)

- Comprehensive and Brief ICF Core Sets Stroke1Document4 pagesComprehensive and Brief ICF Core Sets Stroke1robins kumarNo ratings yet

- Functions of CommunicationDocument1 pageFunctions of CommunicationMohitNo ratings yet

- Effective Time Management and Avoiding Procrastination LeafletDocument4 pagesEffective Time Management and Avoiding Procrastination LeafletOnerous ChimsNo ratings yet

- Charismatic and Transformational LeadershipDocument12 pagesCharismatic and Transformational LeadershipTejas DesaiNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Year 5 EnglishDocument5 pagesLesson Plan Year 5 EnglishMuhd HirdziNo ratings yet

- VdV2020 VygotskystheoryDocument7 pagesVdV2020 VygotskystheoryAndrés Santamaría AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Shaping Customer Satisfaction Through SelfDocument17 pagesShaping Customer Satisfaction Through SelfArief AccountingSASNo ratings yet

- Acculturation ModelDocument17 pagesAcculturation ModelLibagon National High School (Region VIII - Southern Leyte)No ratings yet

- Raksha Karki: Career ObjectiveDocument2 pagesRaksha Karki: Career ObjectiveKumar SonalNo ratings yet

- Assessing A Couple Relationship and Compatibility Using MARI Card Test and Mandala DrawingDocument7 pagesAssessing A Couple Relationship and Compatibility Using MARI Card Test and Mandala DrawingkarinadapariaNo ratings yet

- T H E Metaphysics of Brain Death: Jeff McmahanDocument36 pagesT H E Metaphysics of Brain Death: Jeff McmahandocsincloudNo ratings yet

- Conducting A Brainstorming Session ChecklistDocument4 pagesConducting A Brainstorming Session ChecklistNilesh KurleNo ratings yet

- Scenario Based Learning - PappasDocument25 pagesScenario Based Learning - PappasCreators CollegeNo ratings yet

- E F CarritDocument7 pagesE F CarritAnonymous lviObMpprNo ratings yet

- The Role of Symbol in A Streetcar Named DesireDocument7 pagesThe Role of Symbol in A Streetcar Named DesireDebdeep RoyNo ratings yet

- SUBIECT PENTRU OLIMPIADA DE LIMBA ENGLEZĂ - ETAPA LOCALĂ - Manuela PanescuDocument6 pagesSUBIECT PENTRU OLIMPIADA DE LIMBA ENGLEZĂ - ETAPA LOCALĂ - Manuela PanescuAdoptedchildNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Inclusive Education: Click For UpdatesDocument15 pagesInternational Journal of Inclusive Education: Click For UpdatesfadhNo ratings yet

- The Brand Safety Effect CHEQ Magna IPG Media LabDocument21 pagesThe Brand Safety Effect CHEQ Magna IPG Media LabAndres NietoNo ratings yet

- Qualitative-Research 111419Document11 pagesQualitative-Research 111419Cristian Rey AbalaNo ratings yet

- Song LyricsDocument1 pageSong LyricsRegina AbacNo ratings yet