Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Karani 2022 The Influence of Screen Time On Chi

Karani 2022 The Influence of Screen Time On Chi

Uploaded by

Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Hospital Bill FormatDocument2 pagesHospital Bill Formatsandee1910100% (2)

- A Student Will Lead A PrayerDocument11 pagesA Student Will Lead A PrayerEsther Joy Perez100% (3)

- Death of A Parent - Transition To A New Adult IdentityDocument264 pagesDeath of A Parent - Transition To A New Adult IdentityYuanitaDSNo ratings yet

- Scoping Review+naulDocument8 pagesScoping Review+naulJared LeyrosNo ratings yet

- PR Chapter 1Document23 pagesPR Chapter 1JAMES ROLDAN HUMANGITNo ratings yet

- Effects of Screen Timing On ChildrenDocument7 pagesEffects of Screen Timing On ChildrenWarengahNo ratings yet

- Mupalla 2023Document5 pagesMupalla 2023Merry BearrNo ratings yet

- Cureus 0015 00000045396Document9 pagesCureus 0015 00000045396Halisyah HasyimNo ratings yet

- Malaysian Parents Perceptionof How Screen Time Affectstheir Childrens LanguageDocument11 pagesMalaysian Parents Perceptionof How Screen Time Affectstheir Childrens LanguageJerryNo ratings yet

- Language Acquisition and Infant's Exposure To Television in Pakistan: Phenomenological Study of Mother's ExperiencesDocument11 pagesLanguage Acquisition and Infant's Exposure To Television in Pakistan: Phenomenological Study of Mother's ExperiencesSky AerisNo ratings yet

- Health ScreenDocument8 pagesHealth ScreenNadia hasibuanNo ratings yet

- Apa 14176Document24 pagesApa 14176LeticiaNo ratings yet

- Raising The Child Do Screen Media Help or Hinder The Quality Over Quantity HypothesisDocument15 pagesRaising The Child Do Screen Media Help or Hinder The Quality Over Quantity HypothesisjosuedsmaximoNo ratings yet

- PXX 123Document8 pagesPXX 123Anonymous h0DxuJTNo ratings yet

- 2019 - JSLHR S 18 0301Document17 pages2019 - JSLHR S 18 0301Andreia TavaresNo ratings yet

- ConclusionDocument3 pagesConclusionAlthea Gwyneth MataNo ratings yet

- A Goal Theoretic Framework For Parental Screen Time Monitoring BehaviorDocument15 pagesA Goal Theoretic Framework For Parental Screen Time Monitoring BehaviorDaniel WogariNo ratings yet

- CHILD - Impact of Screen Viewing On Cognitive Development - For Circulation DigitalDocument4 pagesCHILD - Impact of Screen Viewing On Cognitive Development - For Circulation DigitalyunielescazNo ratings yet

- British J of Dev Psycho - 2022 - Medawar - Early Language Outcomes in Argentinean Toddlers Associations With Home LiteracyDocument18 pagesBritish J of Dev Psycho - 2022 - Medawar - Early Language Outcomes in Argentinean Toddlers Associations With Home LiteracyXimena LanosaNo ratings yet

- Detailing The Digital Experience - Parent Reports of Children's Media Use in The Home Learning EnvironmentDocument13 pagesDetailing The Digital Experience - Parent Reports of Children's Media Use in The Home Learning Environmentgalih wiratmokoNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Screen Time On The Academic Performance of Grade 10-Antonio Luna at Bacoor National High School Tabing-Dagat S.Y. 2022-2023Document12 pagesThe Effect of Screen Time On The Academic Performance of Grade 10-Antonio Luna at Bacoor National High School Tabing-Dagat S.Y. 2022-2023jianmahinay76No ratings yet

- PXX 123Document8 pagesPXX 123Manzur al MatinNo ratings yet

- Herodotou 2017Document9 pagesHerodotou 2017Nicole BroccaNo ratings yet

- Penggunaan Smart Phone Terhadap Motorik Halus Dan Bicara BahasaDocument22 pagesPenggunaan Smart Phone Terhadap Motorik Halus Dan Bicara BahasaYossy RosmalasariNo ratings yet

- 2023 Qu EnfantstroublesdvptDocument10 pages2023 Qu EnfantstroublesdvptWil HelmNo ratings yet

- Processess of Children'S Learning and Speech Development in Early YearsDocument10 pagesProcessess of Children'S Learning and Speech Development in Early YearsSophia CatalanNo ratings yet

- Screen Time and Speech and Language Delay in Children Aged 12-48 Months in UAE A Case-Control StudyDocument8 pagesScreen Time and Speech and Language Delay in Children Aged 12-48 Months in UAE A Case-Control StudyGautam BehlNo ratings yet

- Screen Time PaperDocument6 pagesScreen Time PaperBrittany Wright PruittNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 - Lesson 1Document6 pagesUnit 1 - Lesson 1Debbie BaniquedNo ratings yet

- Artikel Bahasa Pert 14Document4 pagesArtikel Bahasa Pert 140029NurfenitaNo ratings yet

- Relation Between Executive Functions and Screen Time Exposure in Under 6Document10 pagesRelation Between Executive Functions and Screen Time Exposure in Under 6eup_1983No ratings yet

- Porster Board PresentationDocument1 pagePorster Board Presentationapi-320557969No ratings yet

- Media Children Indpendent Study-4-2Document21 pagesMedia Children Indpendent Study-4-2api-610458976No ratings yet

- Australian Early Childhood Education and Care Sector Adults' PerspectivesDocument9 pagesAustralian Early Childhood Education and Care Sector Adults' PerspectivesJia Qi YaoNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Pola Komunikasi Orang Tua Dengan Perkembangan Bahasa Anak Prasekolah (Usia 2-5 Tahun) Rina Nur Hidayati, Umu MaslahahDocument9 pagesHubungan Pola Komunikasi Orang Tua Dengan Perkembangan Bahasa Anak Prasekolah (Usia 2-5 Tahun) Rina Nur Hidayati, Umu MaslahahhusniawatiNo ratings yet

- What Do We Know About Children and Technology?Document20 pagesWhat Do We Know About Children and Technology?Lucienne100% (1)

- Writing Assignment 1 Edu 315Document6 pagesWriting Assignment 1 Edu 315api-608884374No ratings yet

- The Glow GenerationDocument17 pagesThe Glow Generationapi-609525895No ratings yet

- Literature Review 2Document5 pagesLiterature Review 2Madina MalikNo ratings yet

- Research in Spec Educ Needs - 2019 - Roberts-Tyler - Evaluating A Computer Based Reading Programme With Children WithDocument13 pagesResearch in Spec Educ Needs - 2019 - Roberts-Tyler - Evaluating A Computer Based Reading Programme With Children WithIngrid Rovira BonjornNo ratings yet

- Introduction First DraftDocument3 pagesIntroduction First Draftk09768456935No ratings yet

- The Association Between Screen Time and Attention in Children A Systematic ReviewDocument19 pagesThe Association Between Screen Time and Attention in Children A Systematic ReviewAdinda Ratna PuspitaNo ratings yet

- CHILDREN AND TECHNOLOGYeditededitedDocument13 pagesCHILDREN AND TECHNOLOGYeditededitedJully OjwandoNo ratings yet

- Significance On The Relationship Between Screen Time and MetamemoryDocument2 pagesSignificance On The Relationship Between Screen Time and MetamemoryAlthea Gwyneth MataNo ratings yet

- A Study of Time Use and Academic Achievement AmongDocument16 pagesA Study of Time Use and Academic Achievement Amongcosya7021No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0193397314001439 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0193397314001439 MainRene van SchalkwykNo ratings yet

- Screentime Academic Productivity Auxtero 2Document41 pagesScreentime Academic Productivity Auxtero 2kuroimnotherNo ratings yet

- Playing Mobile Educational Games and Its Impact To Students' Spelling and Vocabulary CapabilityDocument6 pagesPlaying Mobile Educational Games and Its Impact To Students' Spelling and Vocabulary CapabilityAila AgapitoNo ratings yet

- HHIS PR 1 RESEARCH Nyek2Document15 pagesHHIS PR 1 RESEARCH Nyek2HehehNo ratings yet

- Association of Screen Time With Parent - Reported Cognitive Delay in Preschool Children of Kerala, IndiaDocument8 pagesAssociation of Screen Time With Parent - Reported Cognitive Delay in Preschool Children of Kerala, IndiaAris BayuNo ratings yet

- Developing YoungChildren Learning Through PlayDocument18 pagesDeveloping YoungChildren Learning Through PlaykrisnahNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Mobile Application Features On Children's Language and Literacy Learning: A Systematic ReviewDocument30 pagesThe Impact of Mobile Application Features On Children's Language and Literacy Learning: A Systematic ReviewsolsharNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Early Child Care and Development Education On Cognitive, Psychomotor, and Affective Domains of LearningDocument10 pagesThe Impact of Early Child Care and Development Education On Cognitive, Psychomotor, and Affective Domains of LearningPhub DorjiNo ratings yet

- DR - SalwaSAl Harbi46522 160160 1 PBDocument6 pagesDR - SalwaSAl Harbi46522 160160 1 PBGiemer HerreraNo ratings yet

- Early Childhood Care and Education Scenario in Preschools: Simegn Sendek YizengawDocument26 pagesEarly Childhood Care and Education Scenario in Preschools: Simegn Sendek Yizengawdagim addisNo ratings yet

- Screen Time - Implications For Early Childhood Cognitive Development - ScienceDirectDocument5 pagesScreen Time - Implications For Early Childhood Cognitive Development - ScienceDirectJoana MauricioNo ratings yet

- Goopio Pura Tismo Velarde - 2nd Interim AssessmentDocument24 pagesGoopio Pura Tismo Velarde - 2nd Interim AssessmentTEOFILO PALSIMON JR.No ratings yet

- Screen Time and Problem Behaviors in Children: Exploring The Mediating Role of Sleep DurationDocument10 pagesScreen Time and Problem Behaviors in Children: Exploring The Mediating Role of Sleep Durationdwi putri ratehNo ratings yet

- JFMPC 8 1999Document4 pagesJFMPC 8 1999Manzur al MatinNo ratings yet

- Action Research ProposalDocument8 pagesAction Research Proposaljinky p.palomaNo ratings yet

- Research On Visual Media and Literacy 4Document6 pagesResearch On Visual Media and Literacy 4api-703568654No ratings yet

- UTS - Estuningtyas MahananiDocument14 pagesUTS - Estuningtyas MahananimahananityasNo ratings yet

- Make Early Learning Standards Come Alive: Connecting Your Practice and Curriculum to State GuidelinesFrom EverandMake Early Learning Standards Come Alive: Connecting Your Practice and Curriculum to State GuidelinesNo ratings yet

- Holt 2013Document9 pagesHolt 2013Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Hudziak 2004Document9 pagesHudziak 2004Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Siu 2008Document12 pagesSiu 2008Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Impact of Socio-Cultural Factors On Senior Secondary School Students" Academic Achievement in PhysicsDocument7 pagesImpact of Socio-Cultural Factors On Senior Secondary School Students" Academic Achievement in PhysicsAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Kendall 2000Document13 pagesKendall 2000Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Arslan 2021Document18 pagesArslan 2021Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Harter 1984 The Pictorial Scale of Perceived CoDocument15 pagesHarter 1984 The Pictorial Scale of Perceived CoAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- American Educational Research Association Review of Educational ResearchDocument36 pagesAmerican Educational Research Association Review of Educational ResearchAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Block-Oriented Programming With Tangibles: An Engaging Way To Learn Computational Thinking SkillsDocument4 pagesBlock-Oriented Programming With Tangibles: An Engaging Way To Learn Computational Thinking SkillsAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- TheEffectOfAgeAtSchoolEntryOn PreviewDocument44 pagesTheEffectOfAgeAtSchoolEntryOn PreviewAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Kindergarten Retention: Academic and Behavioral Outcomes Through The End of Second GradeDocument17 pagesKindergarten Retention: Academic and Behavioral Outcomes Through The End of Second GradeAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Birthdates of Medical School ApplicantsDocument6 pagesBirthdates of Medical School ApplicantsAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Educational Research: To Cite This Article: Angus H. Thompson, Roger H. Barnsley & James Battle (2004) The RelativeDocument9 pagesEducational Research: To Cite This Article: Angus H. Thompson, Roger H. Barnsley & James Battle (2004) The RelativeAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0190740916304467 Main PDFDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0190740916304467 Main PDFAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- A Crossover Randomised and Controlled Trial of TheDocument15 pagesA Crossover Randomised and Controlled Trial of TheAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Alpha-Synuclein Locus Triplication Causes Parkinson's DiseaseSingleton 2003Document1 pageAlpha-Synuclein Locus Triplication Causes Parkinson's DiseaseSingleton 2003Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Health Service Provider 10Document28 pagesHealth Service Provider 10Gian Calimon100% (1)

- Research DefendDocument4 pagesResearch DefendRian Hanz AlbercaNo ratings yet

- Matrix Bands For Perfect, Predictable ContactDocument25 pagesMatrix Bands For Perfect, Predictable Contactabcder1234No ratings yet

- IRN 125-200H-Of Operation & Maintenance Manual (150 Multi LaDocument1,075 pagesIRN 125-200H-Of Operation & Maintenance Manual (150 Multi LaANDRESNo ratings yet

- Horizon HV Course Presentation Course Overview MasterDocument12 pagesHorizon HV Course Presentation Course Overview MasterJohn LioNo ratings yet

- Research ProjectsDocument2 pagesResearch Projectsapi-143464694No ratings yet

- Duchenne Muscular DystrophyDocument9 pagesDuchenne Muscular DystrophyNurul MaghfirahNo ratings yet

- Mayo Scissors CurvedDocument20 pagesMayo Scissors CurvedASHISH KUMAR YADAV100% (1)

- Energy BalanceDocument22 pagesEnergy BalanceMa Mayla Imelda LapaNo ratings yet

- Guessing Word Meaning: Finding Clues From ContextDocument13 pagesGuessing Word Meaning: Finding Clues From Contextcitra dewiNo ratings yet

- Bahasa Inggris Kelas 9Document10 pagesBahasa Inggris Kelas 9Lusiana HerawatiNo ratings yet

- Wakefield (2013) DSM-5 and The General Definition of Personality DisorderDocument17 pagesWakefield (2013) DSM-5 and The General Definition of Personality Disordermariella_manzanaresNo ratings yet

- Hearing ImpairmentDocument10 pagesHearing Impairmentapi-500041382No ratings yet

- Cleland Et. Al. (2009) - CPR para MobilizaDocument15 pagesCleland Et. Al. (2009) - CPR para MobilizaFrancieleNo ratings yet

- Primer Manifiesto Mundial Contra PseudocienciasDocument124 pagesPrimer Manifiesto Mundial Contra PseudocienciasTita AlvAlvNo ratings yet

- A Truly National Plumbing CodeDocument4 pagesA Truly National Plumbing Codeshaimaa mamdouhNo ratings yet

- Chandima de Alwis Seneviratne Healthcare ResumeDocument1 pageChandima de Alwis Seneviratne Healthcare Resumechandima.senevi23No ratings yet

- Nascop Indicators ManualDocument85 pagesNascop Indicators Manualjwedter1No ratings yet

- A Framework For Ethical Decision Making: What Is Ethics?Document4 pagesA Framework For Ethical Decision Making: What Is Ethics?Patriot NJROTCNo ratings yet

- UPM - Industrial Training ReportDocument53 pagesUPM - Industrial Training Reportady dya100% (1)

- Chapters 1 3Document44 pagesChapters 1 3Azriel Mae BaylonNo ratings yet

- Cardio Case StudyDocument2 pagesCardio Case StudyEkamjot Kaur GillNo ratings yet

- Francois Magendie 1783-1855Document4 pagesFrancois Magendie 1783-1855Hadj KourdourliNo ratings yet

- Examples of The Subjunctive Mood in English: Common ExpressionsDocument13 pagesExamples of The Subjunctive Mood in English: Common Expressionsabhishek_9990No ratings yet

- Teachers Report Form (TRF) - ProfileDocument5 pagesTeachers Report Form (TRF) - ProfileCoachNo ratings yet

- B2 - Wcet - Inwocna 2017Document37 pagesB2 - Wcet - Inwocna 2017Anis SartikaNo ratings yet

- Kes Pencemaran Udara Di DuniaDocument10 pagesKes Pencemaran Udara Di DuniaDannesa ValenciaNo ratings yet

Karani 2022 The Influence of Screen Time On Chi

Karani 2022 The Influence of Screen Time On Chi

Uploaded by

Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Karani 2022 The Influence of Screen Time On Chi

Karani 2022 The Influence of Screen Time On Chi

Uploaded by

Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteCopyright:

Available Formats

South African Journal of Communication Disorders

ISSN: (Online) 2225-4765, (Print) 0379-8046

Page 1 of 7 Original Research

The influence of screen time on children’s language

development: A scoping review

Authors: Background: An exponential increase in screen time amongst children and adults, has given

Nazeera F. Karani1 rise to a plethora of studies exploring the influences that this exposure may have on children’s

Jenna Sher1

Munyane Mophosho1 development.

Objectives: This review is specifically concerned with understanding the influence of screen

Affiliations:

1

Department of Speech time on children’s language development.

Pathology, Faculty of

Humanities, University of

Method: A scoping review was conducted to explore the available literature relating to the

the Witwatersrand, impact of screen time on children’s language development. The scoping review was based on

Johannesburg, South Africa the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for Scoping

Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) framework and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) framework. The data

Corresponding author:

were analysed using thematic content analysis.

Jenna Sher,

jenna.sher@wits.ac.za Results: This review identified 12 articles. It made an argument for the multifactorial

relationship between screen time and language development, given the associated positive

Dates:

Received: 15 Feb. 2021 and negative effects. The results revealed core themes such as the influence of screen time

Accepted: 28 Sept. 2021 being dependent on various factors and the diverse effects of screen time on children’s

Published: 10 Feb. 2022 language development, with the inclusion of parents’ monitoring of and participation in

viewing, playing a vital role in language development.

How to cite this article:

Karani, N.F., Sher, J., & Conclusion: The review indicated that an increase in the amount of screen time and an early

Mophosho, M. (2022). The

age of onset of viewing have negative effects on language development, with older age of

influence of screen time on

children’s language onset of viewing showing some benefits. Video characteristics, content and co-viewing also

development: A scoping influences language development. This study demonstrates that the negative influences of

review. South African Journal screen time appear to outweigh the positive influences.

of Communication Disorders,

69(1), a825. https://doi. Keywords: language development; screen time; children; positive effects, negative effects.

org/10.4102/sajcd.v69i1.825

Copyright:

© 2022. The Authors. Background

Licensee: AOSIS. This work The fourth industrial revolution (4IR) has led to an increased exposure to screen time in both

is licensed under the

Creative Commons

children and adults globally (Kardefelt-Winther, 2017; Rideout & Hamel, 2006). South Africa has

Attribution License. similarly shown an escalated usage of screen time amongst children and adults (Muthuri et al.,

2014). The increased screen exposure may influence the overall development of children.

According to Nurturing Care: For Early Childhood Development (2020), 38% of children were at

risk of poor development in 2015. In addition, no data is available in South Africa relating to early

stimulation, children’s books and playthings in the home environment (Nurturing care: For early

childhood development, 2020). These are especially vital for children’s language development in

the first 1000 days (3 years) of life, as this is a critical stage for brain development and maturation,

and is the most intensive period of acquiring speech and language skills (Cusick & Georgieff,

2016). However, because of the increase in screen time in children, its influence on language

development may be an area that needs to be explored.

According to current literature, ‘screen time’ can be defined as the duration of time that is spent

with any screen such as phones, video games, televisions, computers, laptops and tablets (Ponti

et al., 2017). In addition, ‘screen time’ may refer to either active or passive screen time (Sweetser,

Johnson, Ozdowska, & Wyeth, 2012). Active screen time is the child’s ability to engage cognitively

or physically in digital activities (Sweetser et al., 2012), whereas passive screen time includes

inactive screen-based activities and/or obtaining digital (screen-based) information in a passive

Read online: manner (Sweetser et al., 2012). It is important to distinguish between active and passive screen time

Scan this QR as it will assist in understanding the specific effects of screen time (i.e. either positive or negative).

code with your

smart phone or

mobile device According to a review of research on physical activity, sedentary behaviour, nutrition, and

to read online.

overweight in children and adolescents (3–18 years old) from South Africa conducted by

http://www.sajcd.org.za Open Access

Page 2 of 7 Original Research

the Sports Science Institute of South Africa (2018), children in

rural areas spend 70% of the day sedentary, which is

Methodology

comparable to children attending preschools in low- and A scoping review was conducted to explore the available

high-income urban areas spending approximately 73% of the literature, on the influence of screen time on language

preschool day sedentary (Draper et al., 2019). Children in development (Munn et al., 2018). The scoping review

low- and high-income urban areas, as well as rural areas in methodology allowed for the broad exploration of the topic

South Africa exceeded the limit of two hours of screen time and allowed the researchers to be more versatile when reporting

per day (with pre-schoolers having a limit of 1 h per day) and on the diverse literature present (Colquhoun et al., 2014).

are exposed to over three hours daily, excluding that for

schoolwork (Draper et al., 2019). According to the studies in The research team followed the methods advised by Levac,

the United States (US), this may be because of parents in the Colquhoun and O’Brien (2010) and involved two researchers.

rural and urban areas allowing their children to watch These two researchers decided on the study issue, the search

television as it acts as a ‘babysitter’ while the parents are at terms, keywords, and the databases to be searched. The

work or occupied. Furthermore, screen time may be perceived researchers followed Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) five-

to be educational and beneficial to their child’s brain phase approach, which included the following steps: (1)

development (Ruangdaraganon et al., 2009). defining the research question, (2) locating relevant

publications, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5)

The review of the literature revealed both positive and compiling, summarising, and publishing the results.

negative effects of screen time on children’s development According to Peters et al. (2015), data extraction enables the

(Ruangdaraganon et al., 2009). The link between screen time researcher to create a logical and systematic summary of the

and speech and language development is not straightforward, literature that is related to the scoping review’s purpose,

and several factors need to be considered. These factors objectives, and research question. The researchers created a

include the duration of screen time, the presence of a co- data extraction table to extract and retain pertinent

viewer, video characteristics, and additional factors that may information relating to the effects of screen usage on language

affect language. This will be elaborated on further under development. It must be noted that this process was limited

discussion. because of the university almanac and scheduling. The table

contains information on the article number, the title of each

The positive effects include educational value, expansion of research/source, author(s), year in which the source was

vocabulary, exposing children to various experiences and published, the country, study’s aims and objectives, study

cultural and linguistic diversity, and keeping them occupied design, participant description, sample size, and findings.

in a safe manner (Balton, Uys, & Alant, 2019; Jordan, 2005;

Rideout & Hamel, 2006). While these studies have reported

positive effects, others have reported negative effects on

Data sources and eligibility criteria

speech, language, motor, cognitive and social development. The initial search was carried out in July 2020 across the

Children begin understanding information after the age of following electronic databases: Google Scholar, PubMed,

two and may have trouble transferring information learnt EBSCO, JSTOR, Wiley Online Library, ScienceDirect, SAGE

from a device’s screen (Ponti et al., 2017). Therefore, it is Journals, and SpringerLink. The eligibility criteria included

important for children to be stimulated and that they interact studies published in English from 2000 onwards (until 2020),

with family members and caregivers through face-to-face with an emphasis on language development and screen time.

interactions to facilitate learning more efficiently. Television Because of a lack of translation resources, only English-

with the purpose of educating children can allow for the language publications were included. Inclusion criteria also

learning of language, literacy, and cognitive development. included full-text publications and sources.

Adults should be cognizant of background television in the

presence of children as studies have shown that an increase The titles and abstracts of the articles were obtained from the

in background television can adversely affect a child’s above databases and a search was conducted on these

language usage, executive functioning, quality of their play, databases using the following keywords and combinations:

language acquisition, attention, and cognition in children (child OR children) AND (‘screen time’ OR ‘digital devices’

younger than 5 years of age. In addition, excessively watching OR ‘media use’ OR television OR technology) AND ‘language

television may also affect mathematic skills, language and development’ AND ‘speech development’.

reading at a young age (Ponti et al., 2017).

Because of the increased exposure of screen time in children Search strategy

and the lack of research in this area, the current study aimed The researchers analysed the titles and abstracts of the articles

to gain a deeper understanding of the relationship between obtained from the databases and thereafter conducted a

screen time (exposure) and the impact on language search on these databases using the following keywords and

development (outcome) in children (population). Thus, this combinations: ‘child/children, screen time’ OR ‘digital

study aimed to answer the following research question: devices’ OR ‘media use’ OR television OR technology AND;

What effects does screen time have on children’s language language development. The articles were required to present

development? research on children’s exposure to screen time, television,

http://www.sajcd.org.za Open Access

Page 3 of 7 Original Research

and media, with one of the study’s objectives or components The screening protocols were then utilised when going

addressing the influence of screen time on language through the search results.

development. Finally, publications were to report on research

completed globally between 2000 and 2020, to ensure that the

Data charting and analysis

literature was current, as concerns about screen time are new

and growing as technology advances (Hawi & Rupert, 2015). Thematic analysis was used since it is the most powerful and

Two reviewers blindly retrieved specific information from effective method of qualitative data analysis because it

the studies to ensure their reliability. captures the complex meanings contained within texts (Guest

et al. 2011). Clarke and Braun’s (2013) six-phase theme

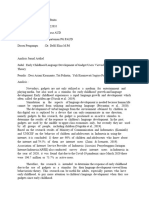

According to Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Arksey and analysis plan was employed in this investigation.

O’Malley (2005), the first level review looked at titles, the

second at abstracts, and the third at full-text articles (refer to Ethical considerations

Figure 1). Entries that did not match the study’s minimum

This article followed all ethical standards for research without

inclusion requirements were omitted. An abstract relevance

direct contact with human or animal subjects.

screening spreadsheet with high level reviewer agreement

(overall kappa) more than 0.8 was employed by the

researchers (Viera & Garrett, 2005). Source selection was Results

done blindly to improve inter-rater consistency. Two Search results

reviewers searched relevant databases for sources and

evaluated them against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Figure 1 depicts the PRISMA-ScR flow diagram showing the

When a disagreement emerged, the third reviewer was data collected by searching through the various databases. A

consulted for conflict resolution to make a final decision. The total of 930 articles were identified in the initial searches. After

reviewers screened the sources’ reference lists prior to removing the duplicate studies, the total number of studies to

examining the titles and abstracts for inclusion and removal. be screened was 546. Following the title and abstract screening,

385 and 136 articles were excluded, respectively, as they did

not meet the inclusion criteria and the screening criteria.

The Internet browser (Google Chrome was recommended)

Therefore, 25 full-text articles were screened with 13 of these

was to be opened on a personal computer (PC) and the name

articles being excluded as certain articles were grey literature,

of the database (Google Scholar, PubMed, EBSCO, JSTOR,

which falls part of the exclusion criteria, and because of the

Wiley Online Library, ScienceDirect, SAGE Journals or

articles containing minimal information relating to language

SpringerLink) to be entered. The ‘advanced’ search option

development. The remaining 12 articles included in the

was selected and the reviewer typed the following key

review for analysis are summarised in the data extraction

terms: (child OR children) AND (‘screen time’ OR ‘digital

table (Figure 1) and Table 1. The researchers analysed the data

devices’ OR ‘media use’ OR television OR technology)

gathered from the literature and identified themes. The

AND ‘language development’ AND ‘speech development’.

reviewers utilised Mendeley Data for data management and

Thereafter under filters, the years between 2000 and 2020

to arrange the various sources obtained.

were selected under the publication date, with English

and ‘peer-reviewed’ being selected before clicking search.

Characteristics of the included sources

Majority of the sources aimed at evaluating the relationship

Records identified through

Identification

database searching (n = 930) between language and screen time. Two sources examined the

language used by children when communicating through

Records after duplicates technology and evaluated television and young children in

removed (n = 546) relation to the American Academy of Paediatrics (AAP)

guidelines that state that children below 2 years of age should

Titles (n = 546) and Records excluded title

Screening

abstracts (n = 161) screened (n = 385) and abstract (n = 136) not be exposed to screen time. These two sources differed from

the other sources, that is, screen time was not accounted for.

Full-text articles assessed Full-text articles

for eligibility (n = 25) excluded, (n = 13) A summary of the study locations and study designs utilised

in the included studies is provided in Table 1. Majority of the

Eligibility

Studies included in

qualitative analysis (n = 12) n = 13 articles were sources reported on television as the type of screen media;

excluded for these reasons: one source reported on videos and another source reported

- Some sources were from on television and videos. It can be inferred that screen time

grey-literature. not only involves television but also computers, smart

Included

- Some sources included

phones, videos, DVDs, etc.

minimal information

relating to speech and

language development. Discussion

Recently a rise in screen time has occurred. Parents use screen

FIGURE 1: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

extension for scoping reviews flow diagram of article search results. time when concerned about their infant’s development,

http://www.sajcd.org.za Open Access

Page 4 of 7 Original Research

TABLE 1: Summary of the location and study designs of the included studies.

Title of study Authors and year of publication Country Study design

A preliminary study on the relationship between Kanako Okuma and Masako Tanimura (2009) Tokyo, Japan (Asia) Observational study

characteristics of television content and delayed speech

development in young children

Association of screen time use and language development Helena Duch, Elisa M. Fisher, Ipek Ensari, Marta Font, - Cross-sectional and

in Hispanic toddlers: A cross-sectional and longitudinal Alison Harrington, Caroline Taromino, Jonathan Yip and longitudinal study

study Carmen Rodriguez (2013)

Association between media viewing and language Frederick J. Zimmerman, Dimitri A. Christakis and United States of America Survey-based

development in children under age 2 years Andrew N. Meltzoff (2007) (North America)

Do hours spent viewing television at ages 3 and 4 predict A. Nayena Blankson, Marion O’Brien, Esther M. Leerkes, - Longitudinal study

vocabulary and execution functioning at age 5? Susan D. Calkins and Stuart Marcovitch (2015)

Duration of watching television and child language Silva Audya Perdana, Bernie Endyami Medise and Emi Jakarta, Indonesia (Asia) Cross-sectional study

development in young children Hemawati Purwaningsih (2017)

How does the use of modern communication technology Helen J. Watt (2010) United Kingdom (Europe) Review

influence language and literacy development? A review

Infants’ and toddlers’ television and language outcomes Deborah L. Linebarger and Dale Walker (2005) United States of America A longitudinal

(North America) process-product design

Relationship between television viewing and language Haewon Byeon and Saemi Hong (2015) Korea (Asia) Cross-sectional survery

delay in toddlers: Evidence from a Korea national

cross-sectional survey

Screen media and language development in infants and Deborah L. Linebarger, Sarah E. Vaala (2010) United States of America Developmental review

toddlers: An ecological perspective (North America)

Television and very young children Daniel R. Anderson and Tiffany A. Pempek (2005) United States of America Review

(North America)

Television viewing associates with delayed language Weerasak Chonchaiya and Chandhita Pruksananonda Thailand (Asia) Case-control study

development (2008)

Television viewing in Thai infants and toddlers: impacts to Nichara Ruangdaraganon, Jariya Chuthapisith, Ladda Thailand (Asia) Longitudinal birth

language development and parental perceptions Mo-suwan, Suntree Kriweradechachai, Umapom cohort study (birth–2

Udomsubpayakul and Chanpen Choprapawon (2009) years old)

development. The study by Perdana et al. (2017) concurred

• Theme 1: the influence of • Theme 2: the diverse with the study by Duch et al. (2013) and Zengin-Akkus et al.

screen time is dependent on influence that screen

a number of factors time has on language

(2018) which stated that no relationship exists between a

development child’s sex, the existence of a television in children’s

1.1) The duration of screen time bedrooms, and delayed language development. Furthermore,

matters child characteristics (existing vocabulary, age, etc.) and

1.2) Adult-directed vs child-directed

viewing: the importance of environmental contexts (interacting with the same content

2.1) Positive

adult co-viewing influences repeatedly and for a long period of time, adult co-viewing

1.3) Video characteristics used 2.2) Negative

in children’s screen time and the quantity and quality of adult–child interactions) can

influences

1.4) Additional factors may also influence language (Linebarger & Vaala, 2010).

affect language delay

Videos may refer to YouTube videos, videos on various

screens, etc. Several studies show that stimulus characteristics

FIGURE 2: Diagram of themes and sub-themes identified.

can also influence language development. It is advisable to

consider video characteristics when deciding on a programme

when parental interaction is reduced (Blankson et al., 2015;

for children. Videos that are rapidly paced with fewer close-

Byeon & Hong, 2015; Perdana, Medise, & Purwaningsih, ups, flashing/changing images, reduced language, and

2017), and to provide opportunities for learning and to increased frame rate can cause language delays. Rapidly

improve cognition (Hinkley & McCann, 2018). paced videos may be cognitively burdening for children

(Duch et al., 2013; Linebarger & Vaala, 2010). Linebarger and

In the current scoping review, two themes and six sub-themes Vaala (2010) stated that programmes like Blue’s Clues and

were generated (see Figure 2). Dora the Explorer have a positive effect on vocabulary, while

Teletubbies have a negative effect on expressive language

Many factors exist that may affect the link between screen because of the video characteristics present.

time and language development, which include the quantity

of home communication provided, genetics (Zengin-Akkus, Finance and neighbourhood safety influence the duration of

Celen-Yoldas, Kurtipek, & Ozmert, 2018), parent-child screen time which children are exposed to. A study conducted

interaction (Blankson, O’Brien, Leerkes, Calkins, & in Soweto, South Africa, and the US reported that children

Marcovitch, 2015; Byeon & Hong, 2015; Linebarger & Vaala, viewed a larger amount of television if the neighbourhood

2010), and male gender (Okuma & Tanimura, 2009). was perceived to be more dangerous as opposed to a safer

neighbourhood, as children were safer indoors compared to

Duch et al. (2013) reported that children who have a television playing outdoors where it could be unsafe (Balton et al., 2019).

in their room spend more time watching television compared

to their counterparts. This is important as the amount of time According to Perdana et al. (2017), as children grow older, the

spent exposed to screen time may influence language duration of screen time increases. This implies that a direct

http://www.sajcd.org.za Open Access

Page 5 of 7 Original Research

relationship exists between the duration of screen time and age. media which differs from the child’s first languages indicates

The duration of screen time is also dependent on cultural and that children may be negatively impacted and places the

socio-economic factors, and may be affected and influenced by child 14.7 times more at risk of a language delay. This is

the habits of family members and parents of the child. Several because of the difference in language and grammatical order

articles report a link between the duration of screen time and of the language which may be confusing for the child and

receptive and expressive language delays (Byeon & Hong, 2015; reduces the amount of guidance provided by the parents

Duch et al., 2013, Perdana et al., 2017). This shows that increased during co-viewing (Perdana et al., 2017).

exposure to screen time in children is not recommended.

The age of exposure to screen time may result in language

According to Hudon, Fennell and Hoftyzer (2013), the quality delay. According to the APA, children below the age of two

of the programme may affect language development more should not be watching television (Perdana et al., 2017). This

than the duration of time spent watching the programme. is because children should comprehend the concept of dual

Background television refers to content, which may not be representation which begins to develop around the age of

understandable, resulting in poorer cognition as little to no two and is not fully developed until after the child is 2 years

attention is paid to it, and parent-child interaction is reduced old (Linebarger & Vaala, 2010).

which is important for cognitive development (Anderson &

Subrahmanyam, 2017; Pempek, Kirkorian, & Anderson, 2014). Screen time has positive effects on a child’s cognitive abilities,

As previously mentioned, excessive background television higher-order language, and literacy skills (Blankson et al.,

may have adverse effects on children. It is distractive, disrupts 2015; Watt, 2010). Screen time may increase vocabulary and

playtime and results in slower language development and language production skills in two-and-a-half-year-old children

lower vocabulary scores as parent-child interaction is reduced. (Linebarger & Vaala, 2010). Several experiments show that

sufficient repetitive exposure to a programme improves a

Screen time may occur when supervised by an adult (adult- child’s problem-solving abilities, ability to imitate and the

directed) or by the child independently (child-directed). Adults ability to learn new words (Linebarger & Vaala, 2010).

are expected to ensure that their children have access to Repeated exposure allows for processing difficulties to be

linguistically and age-appropriate content (Watt, 2010). overcome and facilitates learning of vocabulary and content

Watching two or more hours of child-directed TV a day showed (Linebarger & Vaala, 2010). However, children below 22

6.25 times greater vulnerability to lower communication scores months old were not able to learn novel words with repeated

as compared to the same amount of adult-directed TV (Duch et exposure to a child-directed television programme, but were

able to learn similar new words within their natural

al., 2013). This implies that child-directed viewing may

environment (Krcmar, 2014). Increased exposure to stimuli

negatively impact a child making adult-directed viewing the

that is absorbed but not developmentally constructive may

preferred option. Co-viewing encourages language acquisition.

influence brain development and language acquisition (Watt,

Screen time can help promote learning, but not as much as what

2010). ‘Heavy’ use may negatively impact attention that may

can be learnt through social interactions (Strouse, Troseth,

affect the child’s literacy with these adverse effects outweighing

O’Doherty, & Saylor, 2018). The value of a competent adult, such

the advantages to cognition and literacy (Watt, 2010).

as parents, caregivers, or siblings, providing stimulation by

means of posing questions and interacting with the child during

Screen time can negatively affect language acquisition, early

screen media is highlighted as this will promote vocabulary,

language development (Byeon & Hong, 2015) and play (Lin,

vocalisations, and comprehension. Often televisions and screen

Cherng, Chen, Chen, & Yang, 2015). The first 3 years of a

media are used as ‘babysitters’ to distract children when parents

child’s development are important for brain development,

are busy or when they are not present (Nikken, 2019). This

which is affected by environmental influences (Watt, 2010).

implies that a competent adult may not always be present and

Literacy is also affected as spell-check gadgets reduce spelling

that viewing may be child-directed. This may influence

abilities with technological communication facilitating

children’s language development.

spelling errors to go unnoticed (Watt, 2010). It is the role of

Speech-language therapists (SLTs) to identify, assess and

According to Kemp (2021), 98.2% of people in South Africa

manage individuals presenting with speech and language

have a mobile phone, 98% have a smart phone, 85.4% have a

difficulties (Kathard et al., 2011).

laptop/computer, 43.2% have a tablet, 16.7% have a streaming

television or device, and 18.8% have a smart watch. These

statistics are important as it assists in understanding the Potential study implications

percentage of individuals who own the above devices. This study may contribute to limited research as the impact

of screen time on children’s language development has not

Language develops early through interaction with parents been sufficiently researched, and the sources included in the

and caregivers who provide the child with the means to learn analysis were not within the South African context. Current

the forms and features of the language (Blankson et al., 2015; guidelines relating to screen time are set by the World Health

Byeon & Hong, 2015). In South Africa, many people use Organization (WHO) and APA, and correlate with that from

English as a second language. Research on the impact of Canada, Australia, and South Africa. It states that children

http://www.sajcd.org.za Open Access

Page 6 of 7 Original Research

below 2 years of age should not be exposed to screen time, interpretation, revisions, and editing issues. All authors

children between the ages of 2 and 4 years should not exceed have given final approval to the published version of the

one hour daily, and 2 h per day should not be exceeded in 5- manuscript.

to 17-year-olds. This scoping review may contribute to

guidelines relating to language development of children

Funding information

exposed to screen time and will inform future research

exploring the relationship between screen time and language This research received no specific grant from any funding

development. Future studies could include specific socio- agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

economic factors and a range of languages and cultures. An

assessment could also be conducted with children to assess Data availability

the impact of screen time on their language development

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data

considering parents’ perceptions.

were created or analysed in this study.

This scoping review may have clinical implications and has

the potential to guide speech-language therapy. It could also Disclaimer

provide insight relating to guidance and recommendations The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of

for parents. Speech Language Therapists should provide the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of

parents with strategies and skills to promote language any affiliated agency of the authors.

stimulation and the importance of co-viewing (Canadian 24–

Hour Movement Guidelines, 2020; The Conversation, 2019;

WHO, 2019).

References

Anderson, D.R., & Subrahmanyam, K. (2017). Digital screen media and cognitive

development. Pediatrics, 140(Supplement 2), S57–S61. https://doi.org/10.1542/

As schools move away from paper-based activities (Shonfeld peds.2016-1758C

& Meishar-Tal, 2017), this study could inform education Arksey, H., & O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological

framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and

policies with regards to the increased duration of time spent Practice, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

with screen time which may have adverse effects on language Balton, S., Uys, K., & Alant, E. (2019). Family-based activity settings of children in a

low-income African context. African Journal of Disability (Online), 8, 1–14. https://

development. doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v8i0.364

Blankson, A.N., O’Brien, M., Leerkes, E.M., Calkins, S.D., & Marcovitch, S. (2015). Do

Conclusion

hours spent viewing television at ages 3 and 4 predict vocabulary and executive

functioning at age 5? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 61(2), 264–289. https://doi.

org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.61.2.0264

This review has provided valuable information on the Byeon, H., & Hong, S. (2015). Relationship between television viewing and language

delay in toddlers: Evidence from a Korea national cross-sectional survey. PLoS

influence of screen time on language development. The review One, 10(3), e0120663.

revealed that the influence of screen time is multifactorial and Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines: An Integration of Physical Activity, Sedentary

includes both positive and negative influences on children’s Behaviour, and Sleep. (2020). Retrieved from https://csepguidelines.ca/

language development. Majority of the studies analysed Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013). Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and

developing strategies for effective learning. The Psychologist, 26(2), 120–123.

indicate that an increase in the amount of screen time and the Colquhoun, H.L., Levac, D., O’Brien, K.K., Straus, S., Tricco, A.C., Perrier, L., & Moher, D.

early age of onset of viewing has negative effects on language (2014). Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting.

Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(12), 1291–1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

development, especially for the children under the age of two jclinepi.2014.03.013

with older age of onset of viewing showing some benefits. In Cusick, S. & Georgieff, M. (2016). The role of nutrition in brain development:

The golden opportunity of the ‘First 1000 Days’. The Journal of Pediatrics, 175(1),

addition, video characteristics, content and co-viewing also 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.05.013

influence language development. Parents play a critical role in Draper, C.E., Tomaz, S.A., Bassett, S.H., Harbron, J., Kruger, H.S., Micklesfield, L.K., ...

Lambert, E.V. (2019). Results from the healthy active kids South Africa 2018 report

language development. Although, there are both positive and card. South African Journal of Child Health, 13(3), 130–136. https://doi.

negative effects. It appears that the negative influences org/10.7196/SAJCH.2019.v13i3.1640

outweigh the positive influences, and the researchers invite Duch, H., Fisher, E.M., Ensari, I., Font, M., Harrington, A., Taromino, C., ... Rodriguez, C.

(2013). Association of screen time use and language development in Hispanic

further enquiry into this area. toddlers: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Clinical Pediatrics, 52(9),

857–865. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922813492881

Guest, G., MacQueen, K.M., & Namey, E.E. (2011). Applied thematic analysis.

Acknowledgements Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hawi, N.S., & Rupert, M.S. (2015). Impact of e-discipline on children’s screen time.

Competing interests Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(6), 337–342. https://doi.

org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0608

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal Hinkley, T., & McCann, J.R. (2018). Mothers’ and father’s perceptions of the risks

and benefits of screen time and physical activity during early childhood: A

relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/

in writing this article. s12889-018-6199-6

Hudon, T.M., Fennell, C.T., & Hoftyzer, M. (2013). Quality not quantity of television

viewing is associated with bilingual toddlers’ vocabulary scores. Infant Behavior

and Development, 36(2), 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.01.010

Authors’ contributions Jordan, A.B. (2005). Learning to use books and television: An exploratory study in the

ecological perspective. American Behavioral Scientist, 48(5), 523–538. https://

N.K. conceptualised and designed the topic, conducted the doi.org/10.1177/0002764204271513

scoping review, and authored the initial draft. J.S. and Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2017). How does the time children spend using digital

subsequently M.M. supervised this research project and technology impact their mental well-being, social relationships and physical

activity? An evidence-focused literature review. Florence: UNICEF Office of

contributed throughout, providing crucial input on analysis, Research-Innocenti.

http://www.sajcd.org.za Open Access

Page 7 of 7 Original Research

Kathard, H., Jordaan, H., Moonsamy, S., Wium, A.M., Du Plessis, S., Ramma, L., … Perdana, S., Medise, B., & Purwaningsih, E. (2017). Duration of watching TV and child

Pascoe, M. (2011). How can speech language therapists and audiologists enhance language development in young children. Pediatr Indones, 57(2), 99–103. https://

language and literacy outcomes in South Africa? (And why we urgently need to). doi.org/10.14238/pi57.2.2017.99-103

South African Journal of Communication Disorders, Special Edition, 53, 1–8.

https://doi.org/10.4102/sajcd.v58i2.27 Peters, M.D., Godfrey, C.M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C.B. (2020).

Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of

Kemp, S., (2021). Digital 2021: Global overview report – DataReportal – Global Digital Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/

Insights. DataReportal – Global Digital Insights. Retrieved from https:// XEB.0000000000000050

datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-global-overview-report?utm_

source=Reports&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=Digital_2021&utm_ Ponti, M., Bélanger, S., Grimes, R., Heard, J., Johnson Moreau, M., Norris, E., …

content=Data_Sources_Hyperlink Williams, J. (2017). Screen time and young children: Promoting health and

development in a digital world. Paediatrics and Child Health, 22(8), 461–477.

Krcmar, M. (2014). Can infants and toddlers learn words from repeat exposure to an https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxx123

infant directed DVD? Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 58(2), 196–214.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2014.906429 Rideout, V.J., & Hamel, E. (2006). The media family: Electronic media in the lives of

infants, toddlers, preschoolers and their parents. Henry J. Kaiser Family

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K.K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/

methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748- 7500.pdf

5908-5-69

Ruangdaraganon, N., Chuthapisith, J., Mo-Suwan, L., Kriweradechachai, S.,

Lin, L.Y., Cherng, R.J., Chen, Y.J., Chen, Y.J., & Yang, H.M. (2015). Effects of television Udomsubpayakul, U., & Choprapawon, C. (2009). Television viewing in Thai

exposure on developmental skills among young children. Infant Behavior and infants and toddlers: Impacts to language development and parental perceptions.

Development, 38(1), 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2014.12.005 BMC Pediatrics, 9(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-9-34

Linebarger, D.L., & Vaala, S.E. (2010). Screen media and language development in Shonfeld, M., & Meishar-Tal, H. (2017). The voice of teachers in a paperless classroom.

infants and toddlers: An ecological perspective. Developmental Review, 30(2), Interdisciplinary Journal of e-Skills and Lifelong Learning, 13(1), 185–196. https://

176–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2010.03.006 doi.org/10.28945/3899

Munn, Z., Peters, M.D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Sports Science Institute of South Africa. (2018). Healthy Active Kids South Africa

Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing [Ebook] (5th ed.). Retrieved from https://www.ssisa.com/files/wp-content/

between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research uploads/2018/11/HAKSA-2018-Report-Card-FINAL.pdf

Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Strouse, G.A., Troseth, G.L., O’Doherty, K.D., & Saylor, M.M. (2018). Co-viewing

Muthuri, S.K., Wachira, L.J.M., Leblanc, A.G., Francis, C.E., Sampson, M., Onywera, supports toddlers’ word learning from contingent and noncontingent video.

V.O., & Tremblay, M.S. (2014). Temporal trends and correlates of physical activity, Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 166, 310–326. https://doi.

sedentary behaviour, and physical fitness among school-aged children in Sub- org/10.1016/j.jecp.2017.09.005

Saharan Africa: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Sweetser, P., Johnson, D., Ozdowska, A., & Wyeth, P. (2012). Active versus passive

Research and Public Health, 11(3), 3327–3359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ screen time for young children. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 37(4),

ijerph110303327 94–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911203700413

Nikken, P. (2019). Parents’ instrumental use of media in childrearing: Relationships The Conversation. (2019). Why screen time for babies, children and adolescents needs

with confidence in parenting, and health and conduct problems in children. to be limited. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/why-screen-time-for-

Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(2), 531–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/ babies-children-and-adolescents-needs-to-be-limited-110630

s10826-018-1281-3

Viera, A.J., & Garrett, J.M. (2005). Understanding inter-observer agreement: The

Nurturing Care Framework for Early Childhood Development. (2020). Nurturing care Kappa statistics. Family Medicine, 37(5), 360–363.

framework for early childhood development: A framework for helping children

SURVIVE and THRIVE to TRANSFORM health and human potential. Retrieved from Watt, H.J. (2010). How does the use of modern communication technology influence

https://nurturing-care.org/about/what-is-the-nurturing-care-framework/ language and literacy development? A review. Contemporary Issues in

Communication Science and Disorders, 37, 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1044/

Okuma, K., & Tanimura, M. (2009). A preliminary study on the relationship between cicsd_36_F_141

characteristics of TV content and delayed speech development in young children.

Infant Behavior and Development, 32(3), 312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. World Health Organization. (2019). Guidelines on physical activity, sedentary

infbeh.2009.04.002 behaviour and sleep for children under 5 years of age. World Health Organization.

Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/311664

Pempek, T.A., Kirkorian, H.L., & Anderson, D.R. (2014). The effects of background

television on the quantity and quality of child-directed speech by parents. Zengin-Akkus, P., Celen-Yoldas, T., Kurtipek, G., & Ozmert, E.N. (2018). Speech delay in

Journal of Children and Media, 8(3), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/174827 toddlers: Are they only ‘late talkers?’. The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics, 60(2),

98.2014.920715 165–172. https://doi.org/10.24953/turkjped.2018.02.008

http://www.sajcd.org.za Open Access

You might also like

- Hospital Bill FormatDocument2 pagesHospital Bill Formatsandee1910100% (2)

- A Student Will Lead A PrayerDocument11 pagesA Student Will Lead A PrayerEsther Joy Perez100% (3)

- Death of A Parent - Transition To A New Adult IdentityDocument264 pagesDeath of A Parent - Transition To A New Adult IdentityYuanitaDSNo ratings yet

- Scoping Review+naulDocument8 pagesScoping Review+naulJared LeyrosNo ratings yet

- PR Chapter 1Document23 pagesPR Chapter 1JAMES ROLDAN HUMANGITNo ratings yet

- Effects of Screen Timing On ChildrenDocument7 pagesEffects of Screen Timing On ChildrenWarengahNo ratings yet

- Mupalla 2023Document5 pagesMupalla 2023Merry BearrNo ratings yet

- Cureus 0015 00000045396Document9 pagesCureus 0015 00000045396Halisyah HasyimNo ratings yet

- Malaysian Parents Perceptionof How Screen Time Affectstheir Childrens LanguageDocument11 pagesMalaysian Parents Perceptionof How Screen Time Affectstheir Childrens LanguageJerryNo ratings yet

- Language Acquisition and Infant's Exposure To Television in Pakistan: Phenomenological Study of Mother's ExperiencesDocument11 pagesLanguage Acquisition and Infant's Exposure To Television in Pakistan: Phenomenological Study of Mother's ExperiencesSky AerisNo ratings yet

- Health ScreenDocument8 pagesHealth ScreenNadia hasibuanNo ratings yet

- Apa 14176Document24 pagesApa 14176LeticiaNo ratings yet

- Raising The Child Do Screen Media Help or Hinder The Quality Over Quantity HypothesisDocument15 pagesRaising The Child Do Screen Media Help or Hinder The Quality Over Quantity HypothesisjosuedsmaximoNo ratings yet

- PXX 123Document8 pagesPXX 123Anonymous h0DxuJTNo ratings yet

- 2019 - JSLHR S 18 0301Document17 pages2019 - JSLHR S 18 0301Andreia TavaresNo ratings yet

- ConclusionDocument3 pagesConclusionAlthea Gwyneth MataNo ratings yet

- A Goal Theoretic Framework For Parental Screen Time Monitoring BehaviorDocument15 pagesA Goal Theoretic Framework For Parental Screen Time Monitoring BehaviorDaniel WogariNo ratings yet

- CHILD - Impact of Screen Viewing On Cognitive Development - For Circulation DigitalDocument4 pagesCHILD - Impact of Screen Viewing On Cognitive Development - For Circulation DigitalyunielescazNo ratings yet

- British J of Dev Psycho - 2022 - Medawar - Early Language Outcomes in Argentinean Toddlers Associations With Home LiteracyDocument18 pagesBritish J of Dev Psycho - 2022 - Medawar - Early Language Outcomes in Argentinean Toddlers Associations With Home LiteracyXimena LanosaNo ratings yet

- Detailing The Digital Experience - Parent Reports of Children's Media Use in The Home Learning EnvironmentDocument13 pagesDetailing The Digital Experience - Parent Reports of Children's Media Use in The Home Learning Environmentgalih wiratmokoNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Screen Time On The Academic Performance of Grade 10-Antonio Luna at Bacoor National High School Tabing-Dagat S.Y. 2022-2023Document12 pagesThe Effect of Screen Time On The Academic Performance of Grade 10-Antonio Luna at Bacoor National High School Tabing-Dagat S.Y. 2022-2023jianmahinay76No ratings yet

- PXX 123Document8 pagesPXX 123Manzur al MatinNo ratings yet

- Herodotou 2017Document9 pagesHerodotou 2017Nicole BroccaNo ratings yet

- Penggunaan Smart Phone Terhadap Motorik Halus Dan Bicara BahasaDocument22 pagesPenggunaan Smart Phone Terhadap Motorik Halus Dan Bicara BahasaYossy RosmalasariNo ratings yet

- 2023 Qu EnfantstroublesdvptDocument10 pages2023 Qu EnfantstroublesdvptWil HelmNo ratings yet

- Processess of Children'S Learning and Speech Development in Early YearsDocument10 pagesProcessess of Children'S Learning and Speech Development in Early YearsSophia CatalanNo ratings yet

- Screen Time and Speech and Language Delay in Children Aged 12-48 Months in UAE A Case-Control StudyDocument8 pagesScreen Time and Speech and Language Delay in Children Aged 12-48 Months in UAE A Case-Control StudyGautam BehlNo ratings yet

- Screen Time PaperDocument6 pagesScreen Time PaperBrittany Wright PruittNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 - Lesson 1Document6 pagesUnit 1 - Lesson 1Debbie BaniquedNo ratings yet

- Artikel Bahasa Pert 14Document4 pagesArtikel Bahasa Pert 140029NurfenitaNo ratings yet

- Relation Between Executive Functions and Screen Time Exposure in Under 6Document10 pagesRelation Between Executive Functions and Screen Time Exposure in Under 6eup_1983No ratings yet

- Porster Board PresentationDocument1 pagePorster Board Presentationapi-320557969No ratings yet

- Media Children Indpendent Study-4-2Document21 pagesMedia Children Indpendent Study-4-2api-610458976No ratings yet

- Australian Early Childhood Education and Care Sector Adults' PerspectivesDocument9 pagesAustralian Early Childhood Education and Care Sector Adults' PerspectivesJia Qi YaoNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Pola Komunikasi Orang Tua Dengan Perkembangan Bahasa Anak Prasekolah (Usia 2-5 Tahun) Rina Nur Hidayati, Umu MaslahahDocument9 pagesHubungan Pola Komunikasi Orang Tua Dengan Perkembangan Bahasa Anak Prasekolah (Usia 2-5 Tahun) Rina Nur Hidayati, Umu MaslahahhusniawatiNo ratings yet

- What Do We Know About Children and Technology?Document20 pagesWhat Do We Know About Children and Technology?Lucienne100% (1)

- Writing Assignment 1 Edu 315Document6 pagesWriting Assignment 1 Edu 315api-608884374No ratings yet

- The Glow GenerationDocument17 pagesThe Glow Generationapi-609525895No ratings yet

- Literature Review 2Document5 pagesLiterature Review 2Madina MalikNo ratings yet

- Research in Spec Educ Needs - 2019 - Roberts-Tyler - Evaluating A Computer Based Reading Programme With Children WithDocument13 pagesResearch in Spec Educ Needs - 2019 - Roberts-Tyler - Evaluating A Computer Based Reading Programme With Children WithIngrid Rovira BonjornNo ratings yet

- Introduction First DraftDocument3 pagesIntroduction First Draftk09768456935No ratings yet

- The Association Between Screen Time and Attention in Children A Systematic ReviewDocument19 pagesThe Association Between Screen Time and Attention in Children A Systematic ReviewAdinda Ratna PuspitaNo ratings yet

- CHILDREN AND TECHNOLOGYeditededitedDocument13 pagesCHILDREN AND TECHNOLOGYeditededitedJully OjwandoNo ratings yet

- Significance On The Relationship Between Screen Time and MetamemoryDocument2 pagesSignificance On The Relationship Between Screen Time and MetamemoryAlthea Gwyneth MataNo ratings yet

- A Study of Time Use and Academic Achievement AmongDocument16 pagesA Study of Time Use and Academic Achievement Amongcosya7021No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0193397314001439 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0193397314001439 MainRene van SchalkwykNo ratings yet

- Screentime Academic Productivity Auxtero 2Document41 pagesScreentime Academic Productivity Auxtero 2kuroimnotherNo ratings yet

- Playing Mobile Educational Games and Its Impact To Students' Spelling and Vocabulary CapabilityDocument6 pagesPlaying Mobile Educational Games and Its Impact To Students' Spelling and Vocabulary CapabilityAila AgapitoNo ratings yet

- HHIS PR 1 RESEARCH Nyek2Document15 pagesHHIS PR 1 RESEARCH Nyek2HehehNo ratings yet

- Association of Screen Time With Parent - Reported Cognitive Delay in Preschool Children of Kerala, IndiaDocument8 pagesAssociation of Screen Time With Parent - Reported Cognitive Delay in Preschool Children of Kerala, IndiaAris BayuNo ratings yet

- Developing YoungChildren Learning Through PlayDocument18 pagesDeveloping YoungChildren Learning Through PlaykrisnahNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Mobile Application Features On Children's Language and Literacy Learning: A Systematic ReviewDocument30 pagesThe Impact of Mobile Application Features On Children's Language and Literacy Learning: A Systematic ReviewsolsharNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Early Child Care and Development Education On Cognitive, Psychomotor, and Affective Domains of LearningDocument10 pagesThe Impact of Early Child Care and Development Education On Cognitive, Psychomotor, and Affective Domains of LearningPhub DorjiNo ratings yet

- DR - SalwaSAl Harbi46522 160160 1 PBDocument6 pagesDR - SalwaSAl Harbi46522 160160 1 PBGiemer HerreraNo ratings yet

- Early Childhood Care and Education Scenario in Preschools: Simegn Sendek YizengawDocument26 pagesEarly Childhood Care and Education Scenario in Preschools: Simegn Sendek Yizengawdagim addisNo ratings yet

- Screen Time - Implications For Early Childhood Cognitive Development - ScienceDirectDocument5 pagesScreen Time - Implications For Early Childhood Cognitive Development - ScienceDirectJoana MauricioNo ratings yet

- Goopio Pura Tismo Velarde - 2nd Interim AssessmentDocument24 pagesGoopio Pura Tismo Velarde - 2nd Interim AssessmentTEOFILO PALSIMON JR.No ratings yet

- Screen Time and Problem Behaviors in Children: Exploring The Mediating Role of Sleep DurationDocument10 pagesScreen Time and Problem Behaviors in Children: Exploring The Mediating Role of Sleep Durationdwi putri ratehNo ratings yet

- JFMPC 8 1999Document4 pagesJFMPC 8 1999Manzur al MatinNo ratings yet

- Action Research ProposalDocument8 pagesAction Research Proposaljinky p.palomaNo ratings yet

- Research On Visual Media and Literacy 4Document6 pagesResearch On Visual Media and Literacy 4api-703568654No ratings yet

- UTS - Estuningtyas MahananiDocument14 pagesUTS - Estuningtyas MahananimahananityasNo ratings yet

- Make Early Learning Standards Come Alive: Connecting Your Practice and Curriculum to State GuidelinesFrom EverandMake Early Learning Standards Come Alive: Connecting Your Practice and Curriculum to State GuidelinesNo ratings yet

- Holt 2013Document9 pagesHolt 2013Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Hudziak 2004Document9 pagesHudziak 2004Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Siu 2008Document12 pagesSiu 2008Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Impact of Socio-Cultural Factors On Senior Secondary School Students" Academic Achievement in PhysicsDocument7 pagesImpact of Socio-Cultural Factors On Senior Secondary School Students" Academic Achievement in PhysicsAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Kendall 2000Document13 pagesKendall 2000Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Arslan 2021Document18 pagesArslan 2021Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Harter 1984 The Pictorial Scale of Perceived CoDocument15 pagesHarter 1984 The Pictorial Scale of Perceived CoAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- American Educational Research Association Review of Educational ResearchDocument36 pagesAmerican Educational Research Association Review of Educational ResearchAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Block-Oriented Programming With Tangibles: An Engaging Way To Learn Computational Thinking SkillsDocument4 pagesBlock-Oriented Programming With Tangibles: An Engaging Way To Learn Computational Thinking SkillsAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- TheEffectOfAgeAtSchoolEntryOn PreviewDocument44 pagesTheEffectOfAgeAtSchoolEntryOn PreviewAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Kindergarten Retention: Academic and Behavioral Outcomes Through The End of Second GradeDocument17 pagesKindergarten Retention: Academic and Behavioral Outcomes Through The End of Second GradeAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Birthdates of Medical School ApplicantsDocument6 pagesBirthdates of Medical School ApplicantsAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Educational Research: To Cite This Article: Angus H. Thompson, Roger H. Barnsley & James Battle (2004) The RelativeDocument9 pagesEducational Research: To Cite This Article: Angus H. Thompson, Roger H. Barnsley & James Battle (2004) The RelativeAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0190740916304467 Main PDFDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0190740916304467 Main PDFAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- A Crossover Randomised and Controlled Trial of TheDocument15 pagesA Crossover Randomised and Controlled Trial of TheAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Alpha-Synuclein Locus Triplication Causes Parkinson's DiseaseSingleton 2003Document1 pageAlpha-Synuclein Locus Triplication Causes Parkinson's DiseaseSingleton 2003Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Health Service Provider 10Document28 pagesHealth Service Provider 10Gian Calimon100% (1)

- Research DefendDocument4 pagesResearch DefendRian Hanz AlbercaNo ratings yet

- Matrix Bands For Perfect, Predictable ContactDocument25 pagesMatrix Bands For Perfect, Predictable Contactabcder1234No ratings yet

- IRN 125-200H-Of Operation & Maintenance Manual (150 Multi LaDocument1,075 pagesIRN 125-200H-Of Operation & Maintenance Manual (150 Multi LaANDRESNo ratings yet

- Horizon HV Course Presentation Course Overview MasterDocument12 pagesHorizon HV Course Presentation Course Overview MasterJohn LioNo ratings yet

- Research ProjectsDocument2 pagesResearch Projectsapi-143464694No ratings yet

- Duchenne Muscular DystrophyDocument9 pagesDuchenne Muscular DystrophyNurul MaghfirahNo ratings yet

- Mayo Scissors CurvedDocument20 pagesMayo Scissors CurvedASHISH KUMAR YADAV100% (1)

- Energy BalanceDocument22 pagesEnergy BalanceMa Mayla Imelda LapaNo ratings yet

- Guessing Word Meaning: Finding Clues From ContextDocument13 pagesGuessing Word Meaning: Finding Clues From Contextcitra dewiNo ratings yet

- Bahasa Inggris Kelas 9Document10 pagesBahasa Inggris Kelas 9Lusiana HerawatiNo ratings yet

- Wakefield (2013) DSM-5 and The General Definition of Personality DisorderDocument17 pagesWakefield (2013) DSM-5 and The General Definition of Personality Disordermariella_manzanaresNo ratings yet

- Hearing ImpairmentDocument10 pagesHearing Impairmentapi-500041382No ratings yet

- Cleland Et. Al. (2009) - CPR para MobilizaDocument15 pagesCleland Et. Al. (2009) - CPR para MobilizaFrancieleNo ratings yet

- Primer Manifiesto Mundial Contra PseudocienciasDocument124 pagesPrimer Manifiesto Mundial Contra PseudocienciasTita AlvAlvNo ratings yet

- A Truly National Plumbing CodeDocument4 pagesA Truly National Plumbing Codeshaimaa mamdouhNo ratings yet

- Chandima de Alwis Seneviratne Healthcare ResumeDocument1 pageChandima de Alwis Seneviratne Healthcare Resumechandima.senevi23No ratings yet

- Nascop Indicators ManualDocument85 pagesNascop Indicators Manualjwedter1No ratings yet

- A Framework For Ethical Decision Making: What Is Ethics?Document4 pagesA Framework For Ethical Decision Making: What Is Ethics?Patriot NJROTCNo ratings yet

- UPM - Industrial Training ReportDocument53 pagesUPM - Industrial Training Reportady dya100% (1)

- Chapters 1 3Document44 pagesChapters 1 3Azriel Mae BaylonNo ratings yet

- Cardio Case StudyDocument2 pagesCardio Case StudyEkamjot Kaur GillNo ratings yet

- Francois Magendie 1783-1855Document4 pagesFrancois Magendie 1783-1855Hadj KourdourliNo ratings yet

- Examples of The Subjunctive Mood in English: Common ExpressionsDocument13 pagesExamples of The Subjunctive Mood in English: Common Expressionsabhishek_9990No ratings yet

- Teachers Report Form (TRF) - ProfileDocument5 pagesTeachers Report Form (TRF) - ProfileCoachNo ratings yet

- B2 - Wcet - Inwocna 2017Document37 pagesB2 - Wcet - Inwocna 2017Anis SartikaNo ratings yet

- Kes Pencemaran Udara Di DuniaDocument10 pagesKes Pencemaran Udara Di DuniaDannesa ValenciaNo ratings yet