Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Acupuntura para Enxaqueca

Acupuntura para Enxaqueca

Uploaded by

Esmeraldino NetoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Acupuntura para Enxaqueca

Acupuntura para Enxaqueca

Uploaded by

Esmeraldino NetoCopyright:

Available Formats

Acupuncture for Patients With Migraine: A Randomized

Controlled Trial

Klaus Linde; Andrea Streng; Susanne Jürgens; et al.

Online article and related content

current as of October 5, 2008. JAMA. 2005;293(17):2118-2125 (doi:10.1001/jama.293.17.2118)

http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/293/17/2118

Correction Contact me if this article is corrected.

Citations This article has been cited 73 times.

Contact me when this article is cited.

Topic collections Neurology; Headache; Migraine; Complementary and Alternative Medicine;

Randomized Controlled Trial

Contact me when new articles are published in these topic areas.

Subscribe Email Alerts

http://jama.com/subscribe http://jamaarchives.com/alerts

Permissions Reprints/E-prints

permissions@ama-assn.org reprints@ama-assn.org

http://pubs.ama-assn.org/misc/permissions.dtl

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on October 5, 2008

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

Acupuncture for Patients With Migraine

A Randomized Controlled Trial

Klaus Linde, MD Context Acupuncture is widely used to prevent migraine attacks, but the available

Andrea Streng, PhD evidence of its benefit is scarce.

Susanne Jürgens, MSc Objective To investigate the effectiveness of acupuncture compared with sham acu-

puncture and with no acupuncture in patients with migraine.

Andrea Hoppe, MD

Design, Setting, and Patients Three-group, randomized, controlled trial (April 2002-

Benno Brinkhaus, MD

January 2003) involving 302 patients (88% women), mean (SD) age of 43 (11) years,

Claudia Witt, MD with migraine headaches, based on International Headache Society criteria. Patients

Stephan Wagenpfeil, PhD were treated at 18 outpatient centers in Germany.

Volker Pfaffenrath, MD Interventions Acupuncture, sham acupuncture, or waiting list control. Acupunc-

ture and sham acupuncture were administered by specialized physicians and con-

Michael G. Hammes, MD sisted of 12 sessions per patient over 8 weeks. Patients completed headache diaries

Wolfgang Weidenhammer, PhD from 4 weeks before to 12 weeks after randomization and from week 21 to 24 after

randomization.

Stefan N. Willich, MD, MPH

Main Outcome Measures Difference in headache days of moderate or severe in-

Dieter Melchart, MD tensity between the 4 weeks before and weeks 9 to 12 after randomization.

Results Between baseline and weeks 9 to 12, the mean (SD) number of days with

M

IGRAINE IS A COMMON AND

headache of moderate or severe intensity decreased by 2.2 (2.7) days from a baseline

disabling condition that of 5.2 (2.5) days in the acupuncture group compared with a decrease to 2.2 (2.7) days

typically manifests as at- from a baseline of 5.0 (2.4) days in the sham acupuncture group, and by 0.8 (2.0)

tacks of severe, pulsat- days from a baseline if 5.4 (3.0) days in the waiting list group. No difference was de-

ing, 1-sided headaches, often accompa- tected between the acupuncture and the sham acupuncture groups (0.0 days, 95%

nied by nausea, phonophobiaor or confidence interval, −0.7 to 0.7 days; P=.96) while there was a difference between

photophobia. Population-based studies the acupuncture group compared with the waiting list group (1.4 days; 95% confi-

suggest that 6% to 7% of men and 15% dence interval; 0.8-2.1 days; P⬍.001). The proportion of responders (reduction in head-

ache days by at least 50%) was 51% in the acupuncture group, 53% in the sham

to 18% of women experience migraine

acupuncture group, and 15% in the waiting list group.

headaches.1,2 Although in most cases it

is sufficient to treat acute headaches, Conclusion Acupuncture was no more effective than sham acupuncture in reduc-

many patients require interval treat- ing migraine headaches although both interventions were more effective than a wait-

ing list control.

ment as attacks occur often or are insuf-

JAMA. 2005;293:2118-2125 www.jama.com

ficiently controlled. Drug treatment with

-blockers, calcium antagonists, or other

agents has been shown to reduce the fre- ture, about a third of these had mi- Author Affiliations: Centre for Complementary Medi-

graine or tension-type headaches. In this cine Research, Department of Internal Medicine II (Drs

quency of migraine attacks; however, the Linde, Streng, Hoppe, Weidenhammer, and Mel-

success of treatment is usually modest study, the Acupuncture Randomized chart and Mrs Jürgens), Institute of Medical Statistics

and tolerability often suboptimal.3 Trial (ART-Migraine), we investigated and Epidemiology (Dr Wagenpfeil), and Department

of Neurology (Dr Hammes), Technische Universität

Acupuncture is widely used for pre- whether acupuncture reduced head- München, Munich, Germany; Institute of Social Medi-

venting migraine attacks although its ef- ache frequency more effectively than cine, Epidemiology, and Health Economics, Charité Uni-

sham acupuncture or no acupuncture in versity Medical Center, Berlin, Germany (Drs Brinkhaus,

fectiveness has not yet been fully estab- Witt, and Willich); Munich, Germany (Dr Pfaffenrath);

lished.4 Since 2001, German social health patients with migraines. and Division of Complementary Medicine, Depart-

insurance companies have reimbursed ment of Internal Medicine, University Hospital Zurich,

accredited physicians who provide acu- METHODS Zurich, Switzerland (Dr Melchart).

Corresponding Author and Reprints: Klaus Linde, MD,

puncture treatment for chronic pain. By Design Centre for Complementary Medicine Research, De-

partment of Internal Medicine II, Technische Univer-

December 2004 more than 2 million pa- The methods of this trial have been sität München, Kaiserstrasse 9, 80801 Munich, Ger-

tients had been treated with acupunc- described in detail elsewhere.5 The many (Klaus.Linde@lrz.tu-muenchen.de).

2118 JAMA, May 4, 2005—Vol 293, No. 17 (Reprinted) ©2005 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on October 5, 2008

ACUPUNCTURE TO TREAT MIGRAINE HEADACHES

ART-Migraine was a randomized, mul- Main exclusion criteria were interval group were the same as for the acu-

ticenter trial comparing acupuncture, headaches or additional tension-type puncture group. In each session, at least

sham acupuncture, and a no-acupunc- headache on more than 10 days per 5 out of 10 predefined distant nonacu-

ture waiting list condition. The addi- month; inability to distinguish be- puncture points (see Melchart et al5 for

tional no-acupuncture waiting list con- tween migraine attacks and additional details) were needled bilaterally (at least

trol was included because sham tension-type headache; secondary head- 10 needles) and superficially using fine

acupuncture cannot be substituted for aches; start of headaches after age 50 needles (ie, minimal acupuncture). “De

a physiologically inert placebo. Pa- years; use of analgesics on more than Qi” and manual stimulation of the

tients in the acupuncture groups were 10 days per month; prophylactic head- needles were avoided. All acupunctur-

blinded to which treatment they re- ache treatment with drugs during the ists received oral instructions, a video-

ceived. Analysis of headache diaries was last 4 weeks; and any acupuncture treat- tape, and a brochure with detailed in-

performed by 2 blinded evaluators. The ment during the last 12 months or at formation on sham acupuncture.

study duration per patient was 28 weeks: any time if performed by the partici- Patients in the waiting list control

4 weeks before randomization, the base- pating trial physician. group did not receive any prophylac-

line; 8 weeks of treatment; and 16 weeks Most participants were recruited tic treatment for their headaches for a

of follow-up. Patients allocated to the through reports in local newspapers; period of 12 weeks after randomiza-

waiting list received true acupuncture some patients spontaneously con- tion. After that period they received 12

after 12 weeks and were also followed tacted the trial centers. sessions of the acupuncture treatment

up for 24 weeks after randomization (to described above.

investigate whether changes were simi- Interventions All patients were allowed to treat

lar to those in patients receiving imme- Study interventions were developed by acute headaches as needed. Attack treat-

diate acupuncture). consensus of acupuncture experts and ment should follow the guidelines of the

After the baseline period patients societies and were provided by physi- German Migraine and Headache Soci-

meeting the inclusion criteria were ran- cians trained (at least 140 hours, me- ety8 and had to be documented in the

domly stratified by center (block size dian 500 hours) and experienced (me- headache diary.

12 not known to trial centers) in a 2:1:1 dian 10 years) in acupuncture. Both the Patients were informed with respect

ratio (acupuncture:sham acupuncture: acupuncture and sham acupuncture to acupuncture and sham acupuncture

waiting list) using a centralized tele- treatment consisted of 12 sessions of 30 in the study as follows: “In this study, dif-

phone randomization procedure (ran- minutes’ duration, each administered ferent types of acupuncture will be com-

dom list generated with Sample Size over a period of 8 weeks (preferably 2 pared. One type is similar to the acu-

2.0).6 The 2:1:1 ratio was used to fa- sessions in each of the first 4 weeks, fol- puncture treatment used in China. The

cilitate recruitment and increase the lowed by 1 session per week in the re- other type does not follow these prin-

compliance of trial physicians. All study maining 4 weeks). ciples, but has also been associated with

participants provided written in- Acupuncture treatment was semistan- positive outcomes in clinical studies.”

formed consent. The study was per- dardized. All patients were treated at

formed according to common guide- what are called basic points (gallblad- Outcome Measurement

lines for clinical trials (Declaration of der 20, 40, or 41 or 42, Du Mai– All patients completed headache dia-

Helsinki, International Conference on governing vessel 20, liver 3, San Jiao 3 ries for 4 weeks before randomization

Harmonization–Good Clinical Prac- or 5, extra point Taiyang) bilaterally un- (baseline phase), during the 12 weeks

tice including certification by external less explicit reasons for not doing so after randomization, and during the

audit). The protocol had been ap- were given. Additional points could be weeks 21 to 24 after randomization. In

proved by all relevant local ethics re- chosen individually, according to pa- addition, patients were asked to com-

view boards. tient symptoms.5 Sterile disposable plete a modified version of the pain

1-time-use needles had to be used, but questionnaire of the German Society for

Patients physicians could choose needle length the Study of Pain9 before treatment, af-

To be included, patients had to have a and diameter. Physicians were in- ter 12 weeks, and after 24 weeks. The

diagnosis of migraine, with or without structed to achieve “de Qi” (in which pa- questionnaire includes questions on so-

aura, according to the criteria of the In- tients experience an irradiating feeling ciodemographic characteristics, nu-

ternational Headache Society7; 2 to 8 considered to be indicative of effective merical rating scales for pain inten-

migraine attacks per month during the needling) if possible, and needles were sity, questions on workdays lost, global

last 3 months and during the baseline stimulated manually at least once dur- assessments, etc, as well as the follow-

period; be aged 18 to 65 years; had had ing each session. The total number of ing validated scales: (1) the German ver-

migraines for at least 12 months; had needles was limited to 25 per treatment. sion of the Pain Disability Index10; (2)

completed baseline headache diary; and Number, duration, and frequency of a scale for assessing emotional aspects

provided written informed consent. the sessions in the sham acupuncture of pain (Schmerzempfindungsskala

©2005 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, May 4, 2005—Vol 293, No. 17 2119

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on October 5, 2008

ACUPUNCTURE TO TREAT MIGRAINE HEADACHES

SES)11; (3) the depression scale Allge- ondary outcomes included the num- end of the study, patients were asked

meine Depressionskalla12; (4) the Ger- ber of migraine attacks (episodes of mi- whether they thought that they had re-

man version of the Medical Outcomes graine headaches separated by pain- ceived acupuncture following the prin-

Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Sur- free intervals of at least 48 hours), total ciples of Chinese medicine or the other

vey (SF-36) to assess health-related number of headache days, proportion type of acupuncture.

quality of life.13 of treatment responders, and days with Physicians documented acupunc-

Primary outcome measure was the medication. ture treatment, serious adverse events

difference in number of days with head- To test blinding to treatment and to and adverse effects for each session. Ad-

ache of moderate or severe intensity be- assess the credibility of the respective verse effects were also reported by pa-

tween the 4 weeks before randomiza- treatment methods, patients com- tients at the end of week 12.

tion (baseline phase) and weeks 9 to 12 pleted a credibility questionnaire after

after randomization. Predefined sec- the third acupuncture session.14 At the Statistical Analysis

Confirmatory testing of the primary out-

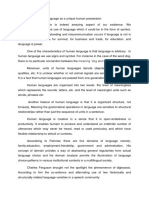

Figure 1. Trial Flow Diagram come measure (using SPSS 11.5, SPSS

Inc, Chicago, Ill) was based on the in-

2000 (Approximately) Patients tention-to-treat population, replacing

Contacted missing data by baseline values (thus,

setting differences compared with base-

1500 (Approximately) Not Interested

in Participation or Had Obvious

line to zero). A priori ordered 2-sided

Violation of Inclusion Criteria null hypotheses to be tested were (1) the

primary outcome measure in the acu-

472 Entered Baseline Period puncture group=outcome in waiting list;

and (2) outcome in the acupuncture

168 Excluded

159 Did Not Meet Inclusion Criteria

group=outcome in the sham acupunc-

9 Recruitment Goal Reached ture group. For each of the hierarchical

hypotheses, we used the t test with a sig-

304 Randomized

nificance level of P⬍.05, thus testing in

2 Erroneously Randomized∗ a first step whether acupuncture is more

efficacious in reducing the number of

days with moderate or severe headache

145 Assigned to Receive 81 Assigned to Receive 76 Assigned to Waiting List

Acupuncture Sham Acupuncture (Control) than no treatment and in a second step

(only if the first null hypothesis was re-

138 Followed Up 12 Weeks 78 Followed Up 12 Weeks 66 Followed Up 12 Weeks jected) whether acupuncture is more ef-

6 Dropped Out 2 Dropped Out (Reason Unclear) 6 Dropped Out

3 Reason Unclear 1 Lost to Follow-up 3 Did Not Accept Assignment

ficacious than sham acupuncture. More-

1 Unsatisfied 1 Change of Residence over, an analysis of covariance with

1 Personal Reasons 1 Disappointment

1 Change of Residence 1 Unclear

additional covariates of age at random-

1 Lost to Follow-up 4 Lost to Follow-up ization and sex was performed to ac-

count for potential baseline differ-

131 Followed Up 24 Weeks 72 Followed Up 24 Weeks ences. Exploratory analyses (2-sided t

7 Lost to Follow-up After Week 12 6 Lost to Follow-up After Week 12

tests and Fisher exact test for pairwise

comparisons of groups without adjust-

145 Included in Primary Analysis 81 Included in Primary Analysis 76 Included in Primary Analysis

132 With Data for the Main 76 With Data for the Main 64 With Data for the Main ment for multiple testing) based on all

Outcome Measure Outcome Measure Outcome Measure available data without replacing miss-

13 Missing Values Replaced 5 Missing Values Replaced 12 Missing Values Replaced

6 Missing Main Outcome 2 Missing Main Outcome 2 Missing Main Outcome ing data are reported for secondary out-

Measure Data Measure Data Measure Data come measures. An additional per-

7 Dropouts Lost to 3 Dropouts Lost to 10 Dropouts Lost to

Follow-Up Follow-Up Follow-Up protocol analysis was performed

including only patients without major

116 Included in per Protocol Analysis 57 Included in per Protocol Analysis 52 Included in per Protocol Analysis protocol violations until week 12.

16 Excluded 19 Excluded 12 Excluded

6 Incomplete Data 4 Incomplete Data 7 Incomplete Data

Due to the positive previous evi-

6 Treatment Protocol Violation 6 Treatment Protocol Violation 5 Other Protocol Deviations dence regarding acupuncture for head-

4 Other Protocol Deviations 9 Other Protocol Deviations

ache4 and the nature of the question

*Although 2 patients assigned to the acupuncture group came only to the initial examination but did not re-

posed by the German health authorities

turn at the end of the baseline phase, one of the large study centers erroneously registered them for random- (See “Role of the Sponsor” in the Ac-

ization. According to the analysis plan the intent-to-treat population comprised only patients with baseline knowledgment section) original sample-

data.

size calculations were based on 1-sided

2120 JAMA, May 4, 2005—Vol 293, No. 17 (Reprinted) ©2005 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on October 5, 2008

ACUPUNCTURE TO TREAT MIGRAINE HEADACHES

testing. Under this premise the study was highly and almost identically (TABLE 2). P=.96; acupuncture vs waiting list, 1.4

planned to have a power of 80% to de- By the end of the study, patients’ ability days, 95% CI, 0.8 to 2.1 days; P⬍.001;

tect a group difference of 1 day with mod- to guess correctly their allocation status 2-sided confirmatory testing, intent-

erate or severe headache with assumed differed significantly between the groups. to-treat population with missing val-

SDs of 2.5 days (thus an effect size of 0.4), Between baseline and week 9 to 12 ues replaced). The results were simi-

assuming a 20% dropout rate.5 How- the number of days with headache of lar if the analysis was restricted to

ever, we later decided to use 2-sided moderate or severe intensity de- patients providing diary data and if

testing to comply better with common creased by a mean (SD) of 2.2 (2.7) days baseline values were entered in the

standards. in the acupuncture group vs 2.2 (2.7) analysis of covariance as covariates. Ad-

days in the sham acupuncture group ditionally, the per-protocol analysis

RESULTS and 0.8 (2.2) days in the waiting list showed similar results. The propor-

Between April 2002 and January 2003 group (difference acupuncture vs sham tion of responders (reduction of head-

approximately 2000 patients with head- acupuncture, 0.0 days; 95% confi- ache days with moderate or severe pain

aches expressed interest in participat- dence interval [CI], −0.7 to 0.7 days; by at least 50%) was 51% in the acu-

ing in the study (FIGURE 1), 472 en-

tered the 4-week baseline period, and

304 were randomly assigned. At one of Table 1. Baseline Characteristics

the large study centers, 2 patients were Sham

All Patients Acupuncture Acupuncture Waiting List

randomly assigned erroneously be- (N = 302) (n = 145) (n = 81) (n = 76)

cause they had only come to the initial Women, No. (%) 267 (88) 129 (89) 73 (90) 65 (86)

examination and never returned for the Age, mean (SD), y 42.6 (11.4) 43.3 (11.8) 41.3 (10.2) 42.5 (11.8)

end of the baseline phase. The intent- Body mass index, mean (SD) 24.0 (4.1) 23.9 (4.1) 23.6 (4.0) 24.7 (4.4)

to-treat population comprised all re- Migraine, No. (%)*

maining 302 patients (145 acupunc- Diagnosis

Migraine without aura 226 (75) 109 (75) 62 (77) 55 (72)

ture, 81 sham acupuncture, 76 waiting

Migraine with aura 87 (29) 40 (28) 23 (28) 24 (32)

list) recruited in 18 outpatient cen-

Duration of disease, mean (SD), y 20.2 (11.8) 20.9 (12.1) 19.2 (11.7) 19.7 (11.3)

ters. Seven patients (5%) in the acu-

Previous acupuncture 121 (40) 63 (43) 30 (37) 28 (37)

puncture group, 3 (4%) in the sham (for any condition), No. (%)

acupuncture group, and 10 (13%) in the Headache symptoms, mean (SD), d

waiting list group withdrew or were lost Moderate to severe headache 5.2 (2.6) 5.2 (2.5) 5.0 (2.4) 5.4 (3.0)

to follow-up at week 12 (P=.03, 2 test). Headache 8.2 (3.7) 8.3 (3.4) 8.3 (3.6) 8.0 (4.3)

Another 10 patients (6 acupuncture, 2 Accompanying symptoms 4.7 (3.0) 4.7 (2.8) 4.7 (3.0) 5.0 (3.3)

sham acupuncture, 2 waiting list) did Activities impaired 2.8 (2.2) 2.7 (2.2) 3.0 (2.1) 2.9 (2.5)

not complete the headache diary in a Medication needed 4.9 (2.8) 5.0 (2.8) 4.8 (2.6) 4.9 (2.8)

manner that allowed extraction of the Migraine attacks 2.8 (1.2) 2.8 (1.2) 2.8 (1.2) 2.8 (1.2)

primary outcome measure, so valid data Attack medication use during

baseline phase, No. (%)

at week 12 were available for 132 pa- Triptans 91 (30) 40 (28) 24 (30) 27 (36)

tients (91%) in the acupuncture group, Ergotamines 6 (2) 2 (1) 2 (2) 2 (3)

76 (94%) in the sham acupuncture Analgesics 220 (73) 103 (71) 64 (79) 53 (70)

group, and 64 (84%) in the waiting list Combinations 55 (18) 30 (21) 11 (14) 14 (19)

group. At week 24, headache diary data Pain, mean (SD), SES,

were available for 131 (90%) of pa- t standard score

Affective 55.9 (8.8) 55.4 (9.0) 56.5 (8.9) 56.1 (8.3)

tients in the acupuncture group and 72

Sensoric 55.1 (8.7) 54.7 (8.7) 54.8 (8.2) 56.2 (9.2)

(89%) in the sham acupuncture group.

Disability, mean (SD), PDI 34.4 (16.6) 32.8 (15.5) 35.8 (17.9) 36.2 (16.9)

Groups were comparable at baseline

Health status, mean (SD)

(TABLE 1). A significant difference was Physical, SF-36† 42.1 (7.5) 41.6 (7.7) 44.0 (6.6) 41.2 (7.8)

only found for the physical health sum- Mental, SF-36† 47.5 (9.9) 47.6 (10.1) 47.2 (10.0) 47.5 (9.5)

mary scale of the SF-36 (less impair- Depression, ADS, 49.4 (8.9) 50.3 (8.6) 48.5 (9.0) 48.6 (9.5)

ment in the sham acupuncture group). t standard score

The mean (SD) number of needles used Average pain rating scale, 5.6 (1.7) 5.6 (1.6) 5.6 (1.6) 5.8 (1.8)

mean (SD)‡

per session was 17 (5) in the acupunc-

Abbreviations: ADS, Allgemeine Depressionsskala, a depression scale; PDI, pain disability index; SES, Schmerzempfind-

ture group and 11 (3) in the sham acu- ungsskala, a questionnaire for assessing the emotional aspects of pain; SF-36, Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item

Short-Form Health Survey.

puncture group. After 3 treatment ses- *Eleven patients had both migraine with and without aura.

sions patients rated the credibility of †Higher values indicate better status.

‡Rating scale 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain and 10 being excruciating.

acupuncture and sham acupuncture very

©2005 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, May 4, 2005—Vol 293, No. 17 2121

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on October 5, 2008

ACUPUNCTURE TO TREAT MIGRAINE HEADACHES

puncture group, 53% in the sham acu- nificantly better for most secondary came apparent after the first 4 weeks

puncture group, and 15% in the wait- outcome measures; however, there were of treatment and increased until week

ing list group. no significant differences between the 12 (FIGURE 2).

Compared with the waiting list con- acupuncture group and the sham acu- The improvements observed in the

trol group, patients receiving acupunc- puncture group (TABLE 3). Response acupuncture groups persisted during

ture or sham acupuncture fared sig- differences in the waiting list group be- the follow-up period (TABLE 4). Re-

sults in the sham acupuncture group

Table 2. Patient Rating of Treatment Credibility and Guess of Treatment Type* tended to be slightly better than those

Acupuncture Sham Acupuncture

in the acupuncture group, but the dif-

ferences were not significant. The pa-

No. of No. of P tients in the waiting list group who re-

Patients Mean (SD) Patients Mean (SD) Value†

ceived acupuncture in weeks 13 to 20

Credibility After Third Session

showed similar improvements after

Improvement expected 142 4.9 (0.9) 80 4.9 (0.9) .88

Recommendation to others 142 5.5 (0.9) 80 5.5 (0.8) .66

treatment as those who had received

Treatment logical 142 4.9 (1.1) 80 4.9 (1.1) .98

immediate treatment (Figure 2).

Effective also for other diseases 142 5.5 (0.8) 80 5.6 (0.7) .35

Within the 24 weeks after random-

ization, 7 participants experienced seri-

Treatment Guess at End of Week 24, No. (%)

ous adverse events (4 acupuncture, 1

No. of patients 129 72

sham acupuncture, 2 waiting list). All

Chinese acupuncture 82 (64) 30 (42)

cases were hospital stays considered

Other type of acupuncture 17 (13) 26 (36) ⬍.001

unrelated to study condition and inter-

Don’t know 30 (23) 16 (22)

*Credibility rating scale with 0 for sham and 6 for maximal agreement.

vention (3 had elective surgery, knee

†P values derived from 2-sided t tests or 2 tests. surgery after household injury, salpin-

Table 3. Secondary Outcomes

Acupuncture vs Acupuncture

Sham Waiting Sham Acupuncture, P vs Waiting List, P

Acupuncture Acupuncture List ⌬ (95% CI) Value* ⌬ (95% CI) Value*

Headache Diary Weeks 9 to 12

Symptoms experienced, mean (SD), d

Moderate to severe headache 2.8 (2.3) 2.6 (2.4) 4.3 (2.2) 0.2 (−0.5 to 0.9) .58 −1.5 (−2.2 to −0.8) ⬍.001

Headache 4.9 (3.4) 4.7 (3.4) 6.3 (3.6) 0.1 (−0.8 to 1.1) .76 −1.4 (−2.5 to −0.4) .008

Medication use 3.2 (3.0) 3.4 (2.9) 4.4 (3.6) −0.2 (−1.0 to 0.6) .65 −1.2 (−2.2 to −0.2) .01

Accompanying symptoms 2.3 (2.5) 2.3 (2.6) 3.9 (2.6) 0.0 (−0.7 to 0.7) .99 −1.6 (−2.4 to −0.9) ⬍.001

Activities impaired 1.2 (1.6) 1.3 (1.8) 2.3 (1.9) 0.2 (−0.6 to 0.3) .53 −1.2 (−1.7 to −0.7) ⬍.001

No. of mean (SD) migraine attacks 1.5 (1.2) 1.6 (1.3) 2.3 (1.1) −0.1 (−0.5 to 0.2) .48 -0.8 (−1.1 to −0.4) ⬍.001

RR (95% CI) RR (95% CI)

Symptom reduction, No. (%)

ⱖ50% Days of moderate to 74 (51) 43 (53) 11 (15) 0.96 (0.74 to 1.25) .78 3.53 (2.00 to 6.23) ⬍.001

severe headache†

ⱖ50% Of migraine attacks† 78 (54) 43 (53) 13 (17) 1.01 (0.79 to 1.31) ⬎.99 3.14 (1.87 to 5.28) ⬍.001

Questionnaire Responses at End of Week 12

⌬ (95% CI) ⌬ (95% CI)

Pain, mean (SD,) SES, t standard scores

Affective 49.3 (10.9) 49.6 (10.7) 54.6 (9.6) −0.3 (−3.3 to 2.8) .85 −5.3 (−8.5 to −2.1) .001

Sensoric 51.5 (10.4) 50.7 (10.0) 56.1 (10.5) 0.8 (−2.1 to 3.7) .60 −4.6 (−7.8 to −1.4) .005

Disability, mean (SD), PDI 20.7 (16.6) 20.2 (5.7) 32.9 (17.1) 0.5 (−4.1 to 5.1) .82 −12.2 (−17.3 to −7.1) ⬍.001

Health status, mean (SD)

Physical, SF-36‡ 46.7 (7.5) 47.5 (7.0) 42.5 (6.6) −0.8 (−2.9 to 1.3) .44 4.3 (2.0 to 6.5) ⬍.001

Mental, SF-36‡ 48.6 (8.8) 47.6 (9.6) 47.7 (10.6) 0.9 (−1.6 to 3.5) .47 0.8 (−2.0 to 3.7) .56

Depression, mean (SD) ADS, t standard scores 46.4 (8.6) 47.2 (10.9) 48.4 (9.8) −1.9 (−4.8 to 0.9) .18 −0.7 (−3.5 to 2.1) .60

Average pain rating scale, mean (SD)§ 3.7 (2.0) 3.6 (2.1) 5.6 (2.1) 0.1 (−0.5 to 0.6) .87 −1.9 (−2.5 to −1.3) ⬍.001

Abbreviations: ADS, Allgemeine Depressionsskala depression scale; CI, confidence interval; ⌬, mean difference between groups; PDI, Pain Disability Index; RR, responder ratio,

proportion responders acupuncture/proportion responders control; SES, Schmerzempfindungsskala, a questionnaire for assessing the emotional aspects of pain; SF-36, Medi-

cal Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey.

*Exploratory P values from 2-sided t tests or Fisher exact test; percentages are column percentages.

†Responder proportions were calculated considering all patients with missing data as nonresponders (145 acupuncture group, 81 sham acupuncture group, and 76 waiting list

group.

‡Higher values indicate better status; minor discrepancies between differences calculated from group means presented in the table and ⌬ are due to rounding.

§Rating scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain and 10 being excruciating.

2122 JAMA, May 4, 2005—Vol 293, No. 17 (Reprinted) ©2005 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on October 5, 2008

ACUPUNCTURE TO TREAT MIGRAINE HEADACHES

gitis, hypertensive crisis, diagnostic pro-

Figure 2. Number of Days With Moderate to Severe Headache

cedures). Thirty-six of 144 (25%)

patients who had received at least 1 acu- 7

puncture treatment reported a total of Acupuncture

Sham Acupuncture

37 adverse effects, and 13 of 81 (16%) 6

Waiting List

receiving sham acupuncture reported 5 Waiting List (With Treatment)

Days With Moderate

or Severe Headache

a total of 14 adverse effects (P = .13,

Fisher exact test). Ten participants in 4

the acupuncture vs 2 in the sham acu- 3

puncture groups reported that the treat-

ment triggered migraine attacks or head- 2

ache, 6 vs 1 reported fatigue, and 4 vs 1

2 reported hematoma, respectively

0

COMMENT Baseline 1 to 4 5 to 8 9 to 12 13 to 16 17 to 20 21 to 24

Week

In this randomized trial, acupuncture

was no more effective than sham acu- Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

puncture in reducing migraine head-

aches although both interventions were

more effective than a waiting list con-

trol. Our study is, to date, one of the

Table 4. Follow-up Data

largest and most rigorous trials on the

Acupuncture vs

efficacy of acupuncture. The advan- Sham Sham Acupuncture, P

tages to this study include a protocol Acupuncture Acupuncture ⌬ (95%CI) Value*

based on current guidelines for mi- Headache Diary Weeks 21 to 24

graine trials,15 strictly concealed cen- Symptoms experienced, mean (SD), d

Moderate to severe headache 3.2 (2.5) 2.6 (2.1) 0.5 (−0.2 to 1.2) .13

tral randomization, assessment of the

Headache 5.2 (3.3) 4.8 (3.1) 0.4 (−0.6 to 1.3) .42

credibility of interventions, blinded di-

ary evaluation, interventions based on Medication 3.6 (3.7) 3.4 (2.5) 0.1 (−0.8 to 1.1) .76

expert consensus, and provision of care Accompanying symptoms 2.3 (2.5) 2.5 (2.5) −0.1 (−0.8 to 0.6) .72

delivered by qualified and experi- Activities impaired 1.3 (1.8) 1.5 (2.0) −0.2 (−0.7 to 0.3) .44

enced medical acupuncturists. Our Migraine attacks, mean (SD) 1.8 (1.4) 1.6 (1.2) 0.2 (−0.3 to 0.5) .55

study also had high follow-up rates. RR (95%CI)

Symptom reduction, No. (%)†

One potential limitation of the study ⱖ50% Days of moderate to 66 (46) 42 (52) 0.88 (0.67 to 1.16) .41

is that participants probably had a more severe headache

positive attitude toward acupuncture ⱖ50% Days of migraine attacks 64 (44) 39 (48) 0.92 (0.69 to 1.23) .58

than the typical patient with migraines Questionnaire Response at the End of Week 24

although experiences from ongoing re- ⌬ (95%CI)

imbursement programs in Germany Pain, mean (SD), SES,

t standard scores

show that a large number of patients Affective 48.6 (11.3) 47.0 (10.3) 1.56 (−1.6 to 4.8) .33

with chronic pain seek acupuncture Sensoric 51.7 (11.2) 49.6 (9.8) 2.0 (−1.1 to 5.2) .20

treatment. Dropout rates in our study Disability, mean (SD), PDI 17.4 (15.5) 15.5 (14.6) 2.0 (−2.4 to 6.4) .38

were low compared with other mi-

Health status, mean (SD)‡

graine prevention trials.3 However, more Physical, SF-36 46.7 (7.0) 48.8 (7.3) −2.1 (−4.2 to 0.0) .05

patients in the waiting list group dis- Mental, SF-36 49.4 (9.0) 47.7 (9.8) 1.7 (−1.0 to 4.4) .22

continued participation in the study af- Depression, mean (SD), ADS, 45.8 (9.1) 46.1 (9.7) −0.3 (−3.1 to 2.4) .82

ter randomization than did those in the t standard scores

other 2 groups. This was probably due Average pain, mean (SD), 3.8 (2.1) 3.4 (2.0) 0.4 (−0.2 to 1.0) .24

to disappointment about having to wait rating scale

Abbreviations: ADS, Allgemeine Depressionsskala, depression scale; CI, confidence interval; ⌬, mean difference between

another 12 weeks for treatment after the groups; PDI, pain disability index; RR, responder ratio (proportion responders acupuncture/proportion responders con-

4-week baseline phase. trol); SES, Schmerzempfindungsskala, questionnaire for assessing the emotional aspects of pain; SF-36, Medical Out-

comes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey.

When patients were asked at the end *Exploratory P values from 2-sided t tests or Fisher exact test.

†Responder proportions were calculated considering all patients with missing data as nonresponders (145, acupuncture

of the trial to guess to which group they group; 81, sham acupuncture group).

had been assigned, the patients’ an- ‡Higher values indicate better status; minor discrepancies between differences calculated from group means presented in

the table and ⌬ are due to rounding.

swers differed significantly between the

©2005 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, May 4, 2005—Vol 293, No. 17 2123

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on October 5, 2008

ACUPUNCTURE TO TREAT MIGRAINE HEADACHES

acupuncture and sham acupuncture sensus-based, semistandardized strategy whether skin penetration matters but

groups, which indicates some degree of in our multicenter trial represents a suit- whether adherence to the traditional

unblinding. However, the results of the able intervention. Another potential concepts of acupuncture makes a dif-

credibility assessment and overall find- explanation for the discrepancy in find- ference. For this purpose, our minimal

ings of our trial make it unlikely that ings could be an overestimation of effects acupuncture intervention was clearly an

the comparison between acupuncture over sham controls in the smaller, older appropriate sham control although it

and sham acupuncture has been se- studies due to bias or chance. might not be an inert placebo.

verely biased by unblinding. An interesting finding of our trial is the Another explanation for the improve-

In this study, it was not possible to strong response to sham acupuncture. ments that we observed could be that

blind waiting list patients. Therefore, The improvement over and the differ- acupuncture and sham acupuncture are

we cannot rule out that the difference ences compared with the waiting list associated with particularly potent pla-

between acupuncture and sham acu- group are clearly clinically relevant. The cebo effects. There is some evidence that

puncture is overestimated due to bias. number of days with moderate or severe complex medical interventions or medi-

However, there are several arguments headache and the frequency of migraine cal devices have higher placebo effects

that could explain why the influence of attacks were reduced by 50% or more than medication.22 Furthermore, acu-

bias should be limited. There was a sig- compared with baseline in half of the puncture treatment has characteristics

nificant improvement over time in the patients and the improvement persisted that are considered relevant in the con-

waiting list group in the first 12 weeks. over several months. This response rate text of placebo effects,23,24 including

This was probably due to the natural is comparable with that observed dur- exotic conceptual framework, empha-

course of the disease or the general ing treatment with medications proven sis on the “individual as a whole,” fre-

effect of being in a study (Hawthorne to be effective migraine prophylaxis, quent patient-practitioner contacts, and

effect). This improvement, however, whereas response rates in placebo groups the repeated “ritual” of needling.

makes it unlikely that patients in the are typically around 30%.3,16-18 Also, the A recent large, pragmatic trial from

waiting list group reported negatively effect of sham acupuncture over wait- the United Kingdom has shown that pa-

biased data in their diary. Analgesic use ing list in our trial is larger than that found tients receiving acupuncture for chronic

was lower in the acupuncture group and in a recent meta-analysis of pain trials headache in addition to care from a gen-

sham acupuncture group, thereby mak- including both a placebo and a no treat- eralist physician did significantly bet-

ing an influence of effective cointer- ment control.19 The strong response to ter than patients receiving care from

ventions unlikely. Follow-up data con- sham acupuncture in our trial could be generalist physician alone at little ad-

firmed the improvements observed after a chance finding. It could also be that the ditional cost.25,26 Preliminary results of

treatment. After completion of the treat- study patients with high expectations of a large, clinical trial from Germany seem

ment, patients had no further contact acupuncture treatment reported posi- to confirm these findings.27 However,

with acupuncturists. In addition, pa- tively biased data. However, the validity these studies did not include a sham

tients received and sent diaries and of our results is supported by the con- control group. Given the uncertain-

questionnaires directly to the study cen- sistency of findings as judged by a vari- ties regarding the potential physiologi-

ter, decreasing the likelihood of posi- ety of instruments including a head- cal effects of sham interventions and the

tively biased diary data. ache diary and validated questionnaires question of enhanced placebo effects,

The lack of differences between acu- on quality of life, disability, and emo- it is crucial that direct head-to-head

puncture and sham acupuncture in our tional aspects of pain. comparisons of acupuncture and

study indicates that point location and The sham acupuncture intervention proven standard drug treatments are

other aspects considered relevant for acu- in our study was designed to minimize conducted in addition to sham-

puncture did not make a difference. To potential physiological effects by nee- controlled trials. Until now, only 2 rig-

some extent, this finding contradicts cur- dling superficially at points distant from orous trials have been published that

rent evidence in the literature. A num- the segments of “true” treatment points compared acupuncture with metopro-

ber of small, mostly single-center trials and by using fewer needles than in the lol28 or flunarizine.29 Their results sug-

have compared acupuncture with a vari- acupuncture group. However, we can- gest that acupuncture might be simi-

ety of sham interventions.4 Although the not rule out that this intervention may larly as effective as medication. Two

results of these trials were not fully con- have had some physiological effects. The other trials with head-to-head compari-

sistent, they suggested that, overall, acu- nonspecific physiological effects of nee- sons of acupuncture and standard drug

puncture is superior to sham interven- dling may include local alteration in cir- treatment are currently under way.30,31

tions. We cannot rule out that the culation and immune function as well Such trials are also desirable to assess

acupuncture interventions used in some as neurophysiological and neurochemi- the aspects of safety and compliance.

of the older studies were more appro- cal responses.20,21 The question investi- In our study, only minor adverse ef-

priate for the treatment of migraine. Nev- gated in our comparison of acupunc- fects were reported and no patient with-

ertheless, we are confident that the con- ture and sham acupuncture was not drew due to adverse effects. This com-

2124 JAMA, May 4, 2005—Vol 293, No. 17 (Reprinted) ©2005 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on October 5, 2008

ACUPUNCTURE TO TREAT MIGRAINE HEADACHES

pares favorably to findings in trials burg; Gmünder Ersatzkasse, Schwäbisch Gmünd; HZK Behinderungseinschätzung bei chronischen

Krankenkasse für Bau-und Holzberufe, Hamburg; Schmerzpatienten. Schmerz. 1994;8:100-110.

studying drug treatment. In the larg- Brühler Ersatzkasse, Solingen; Krankenkasse Ein- 11. Geissner E. Die Schmerzempfindungsskala (SES).

est published randomized trial on mi- tracht Heusenstamm, Heusenstamm; Buchdrucker Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe; 1996.

Krankenkasse, Hannover. 12. Hautzinger M, Bailer M. Allgemeine Depres-

graine prevention, the drop-out rate due Study activities at the Institute for Social Medicine, Epi- sionsskala (ADS): Die deutsche Version des CES-D.

to adverse effects was 6.7% for 160 mg demiology and Health Economics, Berlin were funded Weinheim, Germany: Beltz; 1993.

of propranolol, 6.9% for 10 mg of flu- by the following social health insurance funds: Tech- 13. Bullinger M, Kirchberger I. SF-36 Fragebogen zum

niker Krankenkasse, Hamburg; Betriebskranken- Gesundheitszustand. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe;

narizine, and 8.0% for 5 mg of flunari- kasse, Bosch; Betriebskrankenkasse, Daimler Chrysler; 1998.

zine.19 A recent large randomized trial Betriebskrankenkasse, Bertelsmann; Betriebskranken- 14. Vincent C. Credibility assessments in trials of

kasse, BMW; Betriebskrankenkasse, Siemens; Betrieb- acupuncture. Complement Med Res. 1990;4:8-11.

of topiramate reported a drop-out rate skrankenkasse, Deutsche Bank; Betriebskranken- 15. International Headache Society Clinical Trials

of more than 20%.20 kasse, Hoechst; Betriebskrankenkasse, Hypo Subcommittee. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs

Vereinsbank; Betriebskrankenkasse, Ford; Betriebsk- in migraine: second edition. Cephalalgia. 2000;20:765-

In conclusion, in our trial, acupunc- rankenkasse, Opel; Betriebskrankenkasse, Allianz; Be- 786.

ture was associated with a reduction of triebskrankenkasse, Vereins-und Westbank; Handel- 16. Linde K, Rossnagel K. Propranolol for migraine pro-

skrankenkasse. phylaxis [Cochrane Review on CD-ROM]. Oxford, En-

migraine headaches compared with no Role of the Sponsors: The trial was initiated due to a gland: Cochrane Library, Update Software; 2004; is-

treatment; however, the effects were request from German health care authorities (Fed- sue 2.

similar to those observed with sham eral Committee of Physicians and Social Health Insur- 17. Diener HC, Matias-Guiu J, Hartung E, et al. Effi-

ance Companies, German Federal Social Insurance Au- cacy and tolerability in migraine prophylaxis of flu-

acupuncture and may be due to non- thority) and sponsored by German Social Health narizine in reduced doses: a comparison with pro-

specific physiological effects of nee- Insurance Companies. The health authorities had re- pranolol 160 mg daily. Cephalalgia. 2002;22:209-221.

quested a randomized trial including a sham control 18. Brandes JL, Saper JR, Diamond M, et al. Topira-

dling, to a powerful placebo effect, or condition with an observation period of at least 6 mate for migraine prevention: a randomized con-

to a combination of both. months to decide whether acupuncture should be in- trolled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:965-973.

cluded into routine reimbursement. All other deci- 19. Hrobjartsson A, Gotzsche PC. Is the placebo pow-

Author Contributions: Dr Linde had full access to all sions on design, data collection, analysis, and inter- erless? an analysis of clinical trials comparing placebo

of the data in the study and takes responsibility for pretation, as well as publication were the complete with no treatment. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1594-1602.

the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data responsibility of the researchers. 20. Sandkühler J. The organization and function of

analysis. Acknowledgment: We thank Joseph Hummels- endogenous antinociceptive systems. Prog Neurobiol.

Study concept and design: Linde, Streng, Jürgens, berger, MD, Munich, and Dominik Irnich, MD, De- 1996;50:49-81.

Brinkhaus, Witt, Wagenpfeil, Pfaffenrath, Hammes, partment of Anaesthesiology, Ludwig-Maximilians- 21. Irnich D, Beyer A. Neurobiologische Grundlagen

Weidenhammer, Willich, Melchart. University, Munich, for developing the acupuncture der Akupunkturanalgesie Schmerz. 2002;16:93-102.

Acquisition of data: Linde, Streng, Jürgens, Hoppe, treatment protocols together with Dr Hammes, and 22. Kaptchuk TJ, Goldman P, Stone DA, Stason WB.

Wagenpfeil. for their input at various levels of the protocol devel- Do medical devices have enhanced placebo effects?

Analysis and interpretation of data: Linde, Brinkhaus, opment. We would like to thank Albrecht Neiss, PhD, J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:786-792.

Witt, Wagenpfeil, Weidenhammer, Willich, Melchart Institute of Medical Statistics and Epidemiology, Tech- 23. Kaptchuk TJ. The placebo effect in alternative medi-

Drafting of the manuscript: Linde. nische Universität München, for statistical advice. cine: can the performance of a healing ritual have clini-

Critical revision of the manuscript for important in- cal significance? Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:817-825.

tellectual content: Linde, Jürgens, Hoppe, Brinkhaus, REFERENCES 24. Walach H, Jonas WB. Placebo research: the evi-

Witt, Pfaffenrath, Hammes, Weidenhammer, Willich, dence base for harnessing self-healing capacities. J Al-

Melchart. 1. Stewart WF, Shechter A, Rasmussen BK. Mi- tern Complement Med. 2004;10(suppl 1):S103-S112.

Statistical analysis: Linde, Streng, Wagenpfeil, graine prevalence: a review of population-based 25. Vickers AJ, Rees RW, Zollmann CE, et al. Acupunc-

Weidenhammer. studies. Neurology. 1994;44(suppl 4):S17-S23. ture for chronic headache in primary care: large, prag-

Obtained funding: Willich, Melchart. 2. Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, Diamond ML, matic, randomised trial. BMJ. 2004;328:744-746.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Streng, Reed M. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the 26. Wonderling D, Vickers AJ, Grieve R, McCarney R.

Jürgens, Hoppe, Brinkhaus, Witt, Hammes. United States: data from the American Migraine Study Cost effectiveness analysis of a randomised trial of acu-

Study supervision: Streng, Wagenpfeil, Pfaffenrath, II. Headache. 2001;41:646-657. puncture for chronic headache in primary care. BMJ.

Willich, Melchart. 3. Gray RN, Goslin RE, McCrory DC, Eberlein K, Tul- 2004;328:747-749.

Financial Disclosures: None reported. sky J, Hasselblad V. Drug treatments for the preven- 27. Jena S, Becker-Wtt C, Brinkhaus B, Selim D, Wil-

Participating Trial Centers: Hospital outpatient units: tion of migraine headache: technical review 2.3. 1999; lich SN. Effectiveness of acupuncture treatment for head-

Centre for Complementary Medicine Research, De- Prepared for the Agency of Health Care Policy and Re- ache—the Acupuncture in Routine Care Study (ARC

partment of Internal Medicine II, Technische Univer- search. Available at: http://www.clinpol.mc.duke Headache). Focus Altern Complement Ther. 2004;

sität München, Munich (A. Eustachi, N. Gerling, J. J. .edu. Accessibility verified March 31, 2005. 9(suppl 1):17.

Kleber); Department Complementary Medicine and 4. Melchart D, Linde K, Fischer P, et al. Acupuncture 28. Hesse J, Mogelvang B, Simonsen H. Acupuncture

Integrative Medicine, Knappschafts-Krankenhaus Es- for recurrent headaches: a systematic review of ran- vs metoprolol in migraine prophylaxis: a randomized trial

sen (G. Dobos, A. Füchsel, I. Garäus, C. Niggemeier, domized controlled trials. Cephalalgia. 1999;19:779- of trigger point inactivation. J Intern Med. 1994;235:451-

T. Rampp, L. Tan); Department of Anaesthesiology, 786. 456.

Kreiskrankenhaus Altötting (H. Bettstetter, N. Schraml); 5. Melchart D, Linde K, Streng A, et al. Acupuncture 29. Allais G, De Lorenzo C, Quirico P, et al. Acupunc-

Hospital for Traditional Chinese Medicine Kötzting (S. randomized trials (ART) in patients with migraine or ture in the prophylactic treatment of migraine without

Hager, U. Hager, S. Ma, T. Yangchun); Pain Unit tension-type headache—design and protocols. For- aura: a comparison with flunarizine. Headache. 2002;42:

Marien-Krankenhaus Lünen (A. Lux). sch Komplementarmed Klass Naturheilkd. 2003; 855-861.

Private practices: G. Ahrens, Hausham; C. Ammann, 10:179-184. 30. Molsberger A, Diener HC, Krämer J, et al. GERAC-

Berlin; J. Bek, Berlin; K. J. Driller, Dortmund; I. Eiswirth, 6. Machin D, Campbell MJ, Fayers PM, Pinol APY Akupunktur-Studien—Modellvorhaben zur beur-

Velbert; C. H. Hempen, J. Hummelsberger, H. Leon- Sample Size Tables for Clinical Studies. 2nd ed. Ox- teilung der Wirksamkeit [GERAC acupuncture trials—a

hardy, and R. Nögel, München; A. Jung, Berlin; U. ford, England: Blackwell; 1997. program to assess effectiveness]. Dt Ärztebl. 2002;99:

Kausch, Bogen; B. Kersting, Hasbergen; V. Lerke, Prien; 7. International Headache Society. ICH-10 guide for A1819-A1824.

C. Luckas, Nussdorf; J. Schäfers, Mönchengladbach; headaches. Cephalalgia. 1997;17(suppl 19):1-82. 31. Melchart D, Streng A, Reitmayr S, Hoppe A,

A. Wiebrecht, Berlin. 8. Diener HC, Brune K, Gerber WD, Göbel H, Pfaffenrath Weidenhammer W, Linde K. Programm zur Evalua-

Funding/Support: Study activities at the Centre for V. Behandlung der Migräneattacke und tion der Patientenversorgung mit Akupunktur (PEP-

Complementary Medicine Research, Munich were Migräneprophylaxe. Dt Ärztebl. 1997;94:C2277-C2283. AC)—die wissenschaftliche Begleitung des Modell-

funded by the following social health insurance funds: 9. Nagel B, Gerbershagen HU, Lindena G, Pfingsten vorhabens der Ersatzkassen [Program to evaluate

Deutsche Angestellten-Krankenkasse, Hamburg; M. Entwicklung und empirische Überprüfung des Deut- acupuncture in the German health care system (PEP-

Barmer Ersatzkasse, Wuppertal; Kaufmännische Kran- schen Schmerzfragebogens der DGSS. Schmerz. 2002; AC)—the scientific concept of the program of a group

kenkasse, Hannover; Hamburg-Münchener Kranken- 16:263-270. of statutory sickness funds]. Z ärztl Fortbild Qual

kasse, Hamburg; Hanseatische Krankenkasse, Ham- 10. Dillmann U, Nilges P, Saile E, Gerbershagen HU. Gesundhwes. 2004;98:471-473.

©2005 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, May 4, 2005—Vol 293, No. 17 2125

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on October 5, 2008

You might also like

- CalAPA C2 S1 A ContextEdFocusCommunityPracDocument5 pagesCalAPA C2 S1 A ContextEdFocusCommunityPracCorinne Pysher100% (2)

- Tachyphylaxis in Major Depressive DisorderDocument10 pagesTachyphylaxis in Major Depressive DisorderAlvaro HuidobroNo ratings yet

- Perception of Grade 11 Students Towards The Need To Implement Comprehensive Sex Education in Leyte National High SchoolDocument65 pagesPerception of Grade 11 Students Towards The Need To Implement Comprehensive Sex Education in Leyte National High SchoolJhon AmorNo ratings yet

- Corporate Finance SyllabusDocument2 pagesCorporate Finance SyllabusaNo ratings yet

- Aapm 08 06 81688Document6 pagesAapm 08 06 81688Asti DwiningsihNo ratings yet

- Fneur 14 1193752Document10 pagesFneur 14 1193752Juliane Farinelli PanontinNo ratings yet

- Acm 2009 0376Document10 pagesAcm 2009 0376Dr Tanu GogoiNo ratings yet

- Aspirin in Episodic Tension-Type Headache: Placebo-Controlled Dose-Ranging Comparison With ParacetamolDocument9 pagesAspirin in Episodic Tension-Type Headache: Placebo-Controlled Dose-Ranging Comparison With ParacetamolErwin Aritama IsmailNo ratings yet

- An Algorithm of Migraine TreatmentDocument4 pagesAn Algorithm of Migraine TreatmentSnezana MihajlovicNo ratings yet

- Grazzi - Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For High Frequency Episodic Migraine Without Aura FindingsDocument11 pagesGrazzi - Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For High Frequency Episodic Migraine Without Aura FindingsPriscila CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Estudo InicialDocument16 pagesEstudo InicialChris RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Low-Dose Ketamine Does Not Improve Migraine in The Emergency Department A Randomized Placebo-Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesLow-Dose Ketamine Does Not Improve Migraine in The Emergency Department A Randomized Placebo-Controlled TrialRiza FirdausNo ratings yet

- Effects of Patient-Directed Music Intervention On Anxiety and Sedative Exposure in Critically Ill Patients Receiving Mechanical Ventilatory SupportDocument10 pagesEffects of Patient-Directed Music Intervention On Anxiety and Sedative Exposure in Critically Ill Patients Receiving Mechanical Ventilatory SupportIndahNo ratings yet

- Peripheralneuromodulation Fortreatmentofchronic MigraineheadacheDocument4 pagesPeripheralneuromodulation Fortreatmentofchronic MigraineheadacheCorin Boice TelloNo ratings yet

- JPR 15 2211Document11 pagesJPR 15 2211natneednutNo ratings yet

- Eptinezumab in Episodic Migraine: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study (PROMISE-1)Document14 pagesEptinezumab in Episodic Migraine: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study (PROMISE-1)JUAN MANUEL CERON ALVARADONo ratings yet

- Reflexology For Migraine HeadachesDocument12 pagesReflexology For Migraine Headachescharles100% (1)

- Diener May 2024 New Migraine Drugs A Critical Appraisal of The Reason Why The Majority of Migraine Patients Do NotDocument8 pagesDiener May 2024 New Migraine Drugs A Critical Appraisal of The Reason Why The Majority of Migraine Patients Do NotrenatoNo ratings yet

- 165 Clinical Trials Controlled Trials of Drugs in Migraine 1st Ed ChaDocument13 pages165 Clinical Trials Controlled Trials of Drugs in Migraine 1st Ed Chaนายฐิติภูมิ เพ็งชัยNo ratings yet

- VSC Poster ProjectDocument1 pageVSC Poster ProjectluckyNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: Complementary Therapies in Clinical PracticeDocument29 pagesAccepted Manuscript: Complementary Therapies in Clinical PracticearaliNo ratings yet

- Bronfort2001 2Document10 pagesBronfort2001 2Shaun TylerNo ratings yet

- HeadacheDocument2 pagesHeadachenomyname234No ratings yet

- Van DamDocument5 pagesVan Damapi-484194480No ratings yet

- Relaxation Techniques For People With Epilepsy:: Some Benefits and CautionsDocument3 pagesRelaxation Techniques For People With Epilepsy:: Some Benefits and CautionszingioNo ratings yet

- Migrraine Review 2017 NEJMDocument9 pagesMigrraine Review 2017 NEJManscstNo ratings yet

- Primary Care: Acupuncture For Chronic Headache in Primary Care: Large, Pragmatic, Randomised TrialDocument6 pagesPrimary Care: Acupuncture For Chronic Headache in Primary Care: Large, Pragmatic, Randomised TrialWassim Alhaj OmarNo ratings yet

- Multicenter, Prospective, Single Arm, Open Label, Observational Study of STMS For Migraine Prevention (ESPOUSE Study Starling2018Document11 pagesMulticenter, Prospective, Single Arm, Open Label, Observational Study of STMS For Migraine Prevention (ESPOUSE Study Starling2018CESAR AUGUSTO CARVAJAL RENDONNo ratings yet

- NeurologiaDocument216 pagesNeurologiaPietro BracagliaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Green Light Exposure On Laurent MartinDocument13 pagesEvaluation of Green Light Exposure On Laurent MartinYunita Christiani BiyangNo ratings yet

- Response of Cluster Headache To Kudzu (Complete)Document15 pagesResponse of Cluster Headache To Kudzu (Complete)Andy RotsaertNo ratings yet

- Clinical Reasoning For Manual Therapy Management of Tension Type and Cervicogenic HeadacheDocument7 pagesClinical Reasoning For Manual Therapy Management of Tension Type and Cervicogenic HeadacheMattiaNo ratings yet

- 27-ดวงกมลชนก - อภิสราวรรณ-Erenumab Versus Topiramate for the Prevention of Migraine - a Randomised, Double-blind, Active-controlled Phase 4 TrialDocument11 pages27-ดวงกมลชนก - อภิสราวรรณ-Erenumab Versus Topiramate for the Prevention of Migraine - a Randomised, Double-blind, Active-controlled Phase 4 TrialPleng DuangkamolchanokNo ratings yet

- Bai 2017Document4 pagesBai 2017kurnia fitriNo ratings yet

- High-Dosage Betahistine Dihydrochloride Between 28Document4 pagesHigh-Dosage Betahistine Dihydrochloride Between 28smdj1975No ratings yet

- DESPERTAR de TERCER OJO Samuel Sagan Awakening The Third EyeDocument3 pagesDESPERTAR de TERCER OJO Samuel Sagan Awakening The Third EyemedellincolombiaNo ratings yet

- Numero Agh IDocument7 pagesNumero Agh Ialvaedison00No ratings yet

- Cannabis Based Medicines and Medical Cannabis For Chronic Neuropathic PainDocument14 pagesCannabis Based Medicines and Medical Cannabis For Chronic Neuropathic PainRocio BeteluNo ratings yet

- Dor de Cabeça IIDocument11 pagesDor de Cabeça IIElisaLadagaNo ratings yet

- Gloster 2015Document10 pagesGloster 2015Cindy GautamaNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Medically Intractable Cluster Headache by Occipital Nerve Stimulation: Long-Term Follow-Up of Eight PatientsDocument8 pagesTreatment of Medically Intractable Cluster Headache by Occipital Nerve Stimulation: Long-Term Follow-Up of Eight PatientsareteusNo ratings yet

- MigraineDocument9 pagesMigraineTiago Gomes de PaulaNo ratings yet

- Analgesic Effects of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulationon Modified 2010 Criteria-Diagnosed FibromialgiaDocument7 pagesAnalgesic Effects of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulationon Modified 2010 Criteria-Diagnosed FibromialgiaarturohcuervoNo ratings yet

- Referensi 3Document9 pagesReferensi 3Agustin RiskiNo ratings yet

- J Pharep 2017 02 019Document8 pagesJ Pharep 2017 02 019Daniel Garcia del PinoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 32Document15 pagesJurnal 32Indah YoulpiNo ratings yet

- RCT Gua ShaDocument8 pagesRCT Gua ShairiantokamilaNo ratings yet

- Acupuncture - MeniereDocument4 pagesAcupuncture - MeniereTinnitus Man IndonesiaNo ratings yet

- Bahan Journal Reading MigraineDocument9 pagesBahan Journal Reading Migraineleviana aurelliaNo ratings yet

- MigraineDocument6 pagesMigraineNatália CândidoNo ratings yet

- 2014 TMO en Dolores de Cabeza, Revisión SistemáticaDocument8 pages2014 TMO en Dolores de Cabeza, Revisión Sistemáticaignacio quirogaNo ratings yet

- Arnadottir & Sigurdardottir, 2013 - Is Craniosacral Therapy Effective For Migrane - Tested With HIT - QuestionnaireDocument4 pagesArnadottir & Sigurdardottir, 2013 - Is Craniosacral Therapy Effective For Migrane - Tested With HIT - QuestionnaireFlávio GuimarãesNo ratings yet

- Osteopathy For Primary Headache Patients: A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesOsteopathy For Primary Headache Patients: A Systematic ReviewWanniely KussNo ratings yet

- Acute and Preventive Pharmacologic Treatment of Cluster HeadacheDocument12 pagesAcute and Preventive Pharmacologic Treatment of Cluster Headachelusi jelitaNo ratings yet

- The Combined Effect of AcupuncDocument7 pagesThe Combined Effect of AcupuncnsanbaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Mindfulness Meditation Vs Headache Education Rebecca WellsDocument12 pagesEffectiveness of Mindfulness Meditation Vs Headache Education Rebecca WellsYunita Christiani BiyangNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Relapse/Recurrence in Major Depression by Mindfulness-Based Cognitive TherapyDocument9 pagesPrevention of Relapse/Recurrence in Major Depression by Mindfulness-Based Cognitive TherapyElizabeth C VijayaNo ratings yet

- ClusterDocument9 pagesClusterLindenberger BoriszNo ratings yet

- Acupuncture (Reseach IonDocument17 pagesAcupuncture (Reseach IonRalph NicolasNo ratings yet

- Practice: A 32-Year-Old Woman With HeadacheDocument2 pagesPractice: A 32-Year-Old Woman With HeadacheFeliNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Management of Headache DisordersDocument14 pagesInterdisciplinary Management of Headache DisordersareteusNo ratings yet

- Klan Et Al 2023 Behavioral Treatment For Migraine Prophylaxis in Adults Moderator Analysis of A Randomized ControlledDocument11 pagesKlan Et Al 2023 Behavioral Treatment For Migraine Prophylaxis in Adults Moderator Analysis of A Randomized ControlledyennyNo ratings yet

- Trigeminal Nerve Pain: A Guide to Clinical ManagementFrom EverandTrigeminal Nerve Pain: A Guide to Clinical ManagementAlaa Abd-ElsayedNo ratings yet

- Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du ComportementDocument12 pagesCanadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportementrezaferidooni00No ratings yet

- Private Tutoring Among Secondary School Students A Systematic ReviewDocument6 pagesPrivate Tutoring Among Secondary School Students A Systematic ReviewInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Impact of Digital Technology and The Need For Periodical Review of Educational Curriculum in Nigeria Tertiary InstitutionsDocument6 pagesImpact of Digital Technology and The Need For Periodical Review of Educational Curriculum in Nigeria Tertiary InstitutionsEngr. Najeem Olawale AdelakunNo ratings yet

- Request Support TemplateDocument2 pagesRequest Support TemplateoctavioduranjrNo ratings yet

- 1-IRB Form 1 - Initial Application RevisedDocument17 pages1-IRB Form 1 - Initial Application Revisedtvaughan923No ratings yet

- Difficulties in Mathematics of The Education Students in The Polytechnic State College of Antique Bases For Modules DevelopmentDocument12 pagesDifficulties in Mathematics of The Education Students in The Polytechnic State College of Antique Bases For Modules DevelopmentInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Individuals With Disabilities Education ActDocument33 pagesIndividuals With Disabilities Education ActPiney Martin100% (1)

- Group 1 Ngik Moment Theoretical and Conceptual FrameworkDocument3 pagesGroup 1 Ngik Moment Theoretical and Conceptual FrameworktheoNo ratings yet

- How To Identify Industry ChampionsDocument3 pagesHow To Identify Industry ChampionsSantos JdNo ratings yet

- Answer Key Lewis ClarkDocument3 pagesAnswer Key Lewis ClarkAdrianna MartinNo ratings yet

- E-Choupal - An Initiative of ITC: IT For Change Case StudyDocument4 pagesE-Choupal - An Initiative of ITC: IT For Change Case StudyIT for Change100% (1)

- Importance of Project PlanningDocument7 pagesImportance of Project Planningpodder0% (1)

- Human Language As A Unique Human PossessionDocument2 pagesHuman Language As A Unique Human PossessionDahlia Galvan- MaglasangNo ratings yet

- Numerical Approaches To Combustion ModellingDocument851 pagesNumerical Approaches To Combustion ModellingRefik Alper Tuncer100% (1)

- Wu 2019 JCODocument9 pagesWu 2019 JCOluNo ratings yet

- Measure of Central TendancyDocument27 pagesMeasure of Central TendancySadia HakimNo ratings yet

- Colleges of Education Evaluation Form: National Accreditation BoardDocument33 pagesColleges of Education Evaluation Form: National Accreditation Boardsarah AKPONo ratings yet

- Bpharm 080715 PDFDocument28 pagesBpharm 080715 PDFMilind Kumar GautamNo ratings yet

- THE LEVEL OF AWARENESS AMONG THE TEENAGE MOTHERS OF TUBIGON, BOHOL IN RENDERING NEWBORN CARE (Part 1)Document13 pagesTHE LEVEL OF AWARENESS AMONG THE TEENAGE MOTHERS OF TUBIGON, BOHOL IN RENDERING NEWBORN CARE (Part 1)Wuawie MemesNo ratings yet

- Fashion Design Senior ThesisDocument8 pagesFashion Design Senior Thesisbkxk6fzf100% (2)

- PR1 Butil TRIAD17Document50 pagesPR1 Butil TRIAD17Patrick Carolino YbañezNo ratings yet

- Qualitative and QuantitativeDocument6 pagesQualitative and QuantitativeJacob Kennedy LipuraNo ratings yet

- REVISEDDocument63 pagesREVISEDAina De LeonNo ratings yet

- Switching Models: Introductory Econometrics For Finance' © Chris Brooks 2013 1Document33 pagesSwitching Models: Introductory Econometrics For Finance' © Chris Brooks 2013 1Zohra BelmaghniNo ratings yet

- U5 Evaluation JournalDocument6 pagesU5 Evaluation JournalAnonymous c0x6aZNo ratings yet

- Strategic - Management - Marathon - Revision NotesDocument40 pagesStrategic - Management - Marathon - Revision NotesAshmi UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- M-Arch Thesis Program Report-2020-FinalDocument31 pagesM-Arch Thesis Program Report-2020-FinalpalaniNo ratings yet