Professional Documents

Culture Documents

TK RS 2018 - Editorial, Clinical Governance - A Statutory Duty For Quality Improvement

TK RS 2018 - Editorial, Clinical Governance - A Statutory Duty For Quality Improvement

Uploaded by

nadia nuraniCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- T363 GCIS House Rules - Part I (IaaS DBaaS) v1.0Document23 pagesT363 GCIS House Rules - Part I (IaaS DBaaS) v1.0Linus Harri0% (1)

- 1 - Chapter 1. Introduction To Healthcare FinanceDocument1 page1 - Chapter 1. Introduction To Healthcare Financenadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- 15 - Came - Ek.50.001 PDFDocument91 pages15 - Came - Ek.50.001 PDFabu720% (1)

- Universal Declaration of Human RightsDocument8 pagesUniversal Declaration of Human RightselectedwessNo ratings yet

- TK RS 2018 Chapter 3 - Pressure For Change, in Hospitals in A Changing Europe, Open University Press, Buckingham, 2002Document23 pagesTK RS 2018 Chapter 3 - Pressure For Change, in Hospitals in A Changing Europe, Open University Press, Buckingham, 2002nadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Aw-Kars2020-1-Desain Kualitatif-Mei 152020Document89 pagesAw-Kars2020-1-Desain Kualitatif-Mei 152020nadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Residensi Kajian Swot RS Karsui Jusuf 2020Document40 pagesResidensi Kajian Swot RS Karsui Jusuf 2020nadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Health System Resilience in Managing Pandemic Covid-19Document8 pagesHealth System Resilience in Managing Pandemic Covid-19nadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Hospital Marketing Hospital Marketing: Wahyu SulistiadiDocument32 pagesHospital Marketing Hospital Marketing: Wahyu Sulistiadinadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Pembelajaran EpidDocument23 pagesPembelajaran Epidnadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Structure Literature Review Business ProcessDocument28 pagesStructure Literature Review Business Processnadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- TK RS 2018 Cambridge Memorial Hospital By-Laws (Canada)Document33 pagesTK RS 2018 Cambridge Memorial Hospital By-Laws (Canada)nadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Hospital Marketing: Concept & ImplementationsDocument46 pagesHospital Marketing: Concept & Implementationsnadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Health Policy Brief: Telehealth Parity LawsDocument5 pagesHealth Policy Brief: Telehealth Parity Lawsnadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- 4.analisis Situasi, FKK-SWOTDocument93 pages4.analisis Situasi, FKK-SWOTnadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Inventory Is Considered To Be One of The Most Important Assets of A BusinessDocument3 pagesInventory Is Considered To Be One of The Most Important Assets of A Businesselaiza armeroNo ratings yet

- Domesticana RasquachismoDocument11 pagesDomesticana RasquachismoBlanca Caldas ChumbesNo ratings yet

- 1 - SchoolisDead - ReimerDocument29 pages1 - SchoolisDead - ReimerKarmen RežekNo ratings yet

- Learning Basic Grammar Book 2 WithDocument9 pagesLearning Basic Grammar Book 2 Withpsycho_psychoNo ratings yet

- Civil Case Digest NotebookDocument401 pagesCivil Case Digest NotebookHarrison sajorNo ratings yet

- Space Frontier Conference 10: in Search of 2001Document9 pagesSpace Frontier Conference 10: in Search of 2001Space Frontier FoundationNo ratings yet

- Manager Training & Quality - Chennai - Aegis Customer Support Services Private Limited. - 8 To 12 Years of ExperienceDocument3 pagesManager Training & Quality - Chennai - Aegis Customer Support Services Private Limited. - 8 To 12 Years of ExperienceSelecticaDeepshikha AroraNo ratings yet

- Persepolis: The Story of A Childhood and The Story of A ReturnDocument9 pagesPersepolis: The Story of A Childhood and The Story of A ReturnJihan MankaniNo ratings yet

- C TS410 2020-SampleDocument5 pagesC TS410 2020-Samplerahulg.sapNo ratings yet

- HinilawodDocument3 pagesHinilawodJennifer Joy CortezNo ratings yet

- FNCPDocument3 pagesFNCPFatima Ysabelle Marie RuizNo ratings yet

- 2016 List of Committees & Organization Reports PDFDocument2 pages2016 List of Committees & Organization Reports PDFPonnilavan SibiNo ratings yet

- Industrial and Commercial Training - Values Based LeadershipDocument8 pagesIndustrial and Commercial Training - Values Based LeadershipJailamNo ratings yet

- Joachim Hagopian v. Major General William Knowlton, 470 F.2d 201, 2d Cir. (1972)Document14 pagesJoachim Hagopian v. Major General William Knowlton, 470 F.2d 201, 2d Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Nominal Pipe Size NPS, Nominal Bore NB, Outside Diameter ODDocument5 pagesNominal Pipe Size NPS, Nominal Bore NB, Outside Diameter ODRama Krishna Reddy DonthireddyNo ratings yet

- Ultimate Frisbee HandoutsDocument4 pagesUltimate Frisbee HandoutsTinTin Laud TangcoNo ratings yet

- De 3.2Document6 pagesDe 3.2minh trungNo ratings yet

- 12109722Document4 pages12109722Hanabusa Kawaii IdouNo ratings yet

- 2015 SALN FormDocument3 pages2015 SALN FormMiamor NatividadNo ratings yet

- Ec6 JharkhandDocument103 pagesEc6 JharkhandSunilNo ratings yet

- DTM4420Document9 pagesDTM4420Cube7 GeronimoNo ratings yet

- Practice QuestionsDocument11 pagesPractice QuestionsMichaella PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Obama Illinois Attorney RegistrationDocument2 pagesObama Illinois Attorney RegistrationPamela BarnettNo ratings yet

- Daniel Lewis Lee - Preliminary Injunction LiftedDocument10 pagesDaniel Lewis Lee - Preliminary Injunction LiftedLaw&CrimeNo ratings yet

- Drinking Water Sludge Recovery Feb 2011Document2 pagesDrinking Water Sludge Recovery Feb 2011Fernando GarcíaNo ratings yet

- The Federal Polytechnic, IdahDocument3 pagesThe Federal Polytechnic, Idahwisdomeneojoufedo0147No ratings yet

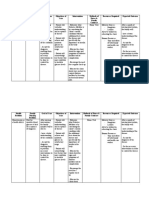

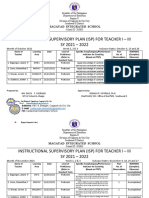

- ISP For Teacher 1Document25 pagesISP For Teacher 1Carlz BrianNo ratings yet

- Basil-Great On The Holy SpiritDocument23 pagesBasil-Great On The Holy SpiritThomas Aquinas 33100% (3)

TK RS 2018 - Editorial, Clinical Governance - A Statutory Duty For Quality Improvement

TK RS 2018 - Editorial, Clinical Governance - A Statutory Duty For Quality Improvement

Uploaded by

nadia nuraniOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

TK RS 2018 - Editorial, Clinical Governance - A Statutory Duty For Quality Improvement

TK RS 2018 - Editorial, Clinical Governance - A Statutory Duty For Quality Improvement

Uploaded by

nadia nuraniCopyright:

Available Formats

J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:73–74 73

Editorial

Clinical governance: a statutory duty for quality

improvement

A frequently aired concern of health profes- ment strategies—such as total quality

sionals throughout the world is the extent to management6—which have been so important

which financial issues dominate the health care to the success of the world’s leading manufac-

agenda. If most of the time of the senior man- turing and service industries, professionally

agement of health care organisations is directed based approaches to quality have also been

towards finance, it is argued, how can a developing. Notably, the evidence-based medi-

commitment towards quality be anything other cine movement7 has rapidly become interna-

than rhetoric? tional in its scope as doctors and other health

Since the beginning of the present decade, care professionals have recognised that a failure

the British National Health Service (NHS) has to make day to day use of the lessons of

operated as an internal market.1 In it, the forces research was producing wasteful variation in

and incentives of a market were seen as creating clinical decision making and unacceptable

an environment within a public sector, non- departures from best practice.

profit making system that would yield greater Specialist electronic data bases, greater

eYciency and improved quality. The new access to information through the internet,

Labour Government that came to power in the reorientation of traditional medical libraries,

spring of 1997 brought to an end this ethos for training in critical appraisal skills, clinical prac-

the health care system in Britain. Many had tice guidelines, and computerised clinical

come to see it as engendering division and decision-support systems are only part of a new

rivalry between hospitals, which, far from pro- infrastructure that health care organisations

moting eYciency, had encouraged duplication, must put in place if they are to give proper sup-

overcapacity and had slowed down badly port to the development of evidence-based

needed rationalisation of services. In publish- practice at local level. The multi-faceted nature

ing a white paper2 that seeks to dismantle this of these changes is posing a particular chal-

internal market and to replace competition lenge for the leaders of health care organisa-

with collaboration, the Government has also tions who must comprehend how they fit

given an important new status to quality. By together to comprise an integrated quality

creating a statutory duty for quality, through strategy.8

“clinical governance” at local level, the NHS is Set alongside this lack of clarity in a complex

seeking to create a new rigour and accountabil- and developing field, are traditional barriers

ity for the standard of care provided to patients between managerial and professional ap-

in hospitals and in primary care. proaches to quality. For example, clinical audit

The term clinical governance introduced in can be portrayed by the professionals as their

the white paper resonates with that of corpo- exclusive domain with an emphasis on educa-

rate governance, a set of financial duties, tional approaches to change and improvement.

accountabilities, and rules of conduct that were Managers often perceive it as a secretive activ-

recommended3 for private sector companies in ity that does not yield tangible benefits for the

the aftermath of a number of high profile mis- organisation. The obstacles to moving forward,

demeanours in the financial markets of the City therefore, are probably much more attitudinal

of London. Later, formal corporate governance than conceptual as models of integrating

policies also became a requirement for health continuous quality improvement programmes

care organisations in Britain.4 A commitment are not complicated.9 10

to good corporate governance brings with it the Despite the enthusiasm and commitment to

certainty that financial issues will be taken very quality improvement by health services and

seriously and will assume a central role in the health professionals over the past decade, pub-

business of the boards of directors that govern lic confidence is still very susceptible to media

hospitals and other health care institutions. coverage of problems in the delivery of health

Responsibility for quality in healthcare has services. Thus, reports of inquiries into lapses

developed along a more informal route. Hospi- in standards of care in particular hospitals

tals and other organisations have increasingly often recount a catalogue of failures in

had to meet specific targets (for example in management and clinical leadership as well as

relation to patient response times5) for quality errant individual behaviour. Worse still is the

improvement but accountability within this enormously negative public impact of recur-

field of healthcare has sometimes seemed frag- rences of similar failures, giving an impression

mented. While the management of many pub- that health services are unable to correct prob-

lic sector bodies in the 1990s has sought to lems reliably and conveying a sense of history

embrace organisation wide quality improve- repeating itself. The issue of poor professional

74 Donaldson

practice and the so called “problem doctor”11 ies in Britain, the new Labour Government is

has also come to prominence in recent years in harmony with the task of rethinking the role

and is a further source of public disquiet about of the state the world over.14 Its white paper2

the quality of healthcare. Although this has led seeks to create a new National Health Service

to strengthening of the professional regulatory that can command the confidence of the public

machinery in Britain,12 there is still a need for that it serves. Clinical governance is a big idea

the prevention, early detection and resolution that deserves to take central stage in the quest

of such problems at local level.13 for high standards in the quality of healthcare.

The new duty for clinical governance in the

LIAM J DONALDSON

local NHS will tackle these quality issues. It is NHS Executive: Northern and Yorkshire Regional OYce,

envisaged that there will be an “accountable John Snow House, Durham University Science Park,

oYcer” in each hospital and other healthcare Durham, DH1 3YG

organisations, that boards will receive monthly

reports, and that annual reports will be made 1 Working for patients. London: HMSO, 1989.

2 The new NHS: modern and dependable. London: HMSO,

available to the public. The clinical governance 1997.

role will be wide ranging and include ensuring 3 Report of the Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate

Governance. London: Gee and Co, 1992.

that: quality improvement processes are in 4 Committee on Standards in Public Life. Report of the Com-

place and integrated with the quality pro- mittee on Standards in Public Life. London: HMSO, 1995.

5 Secretary of State for Health. The patient’s charter: raising the

gramme for the organisation as a whole; that standard. London: HMSO, 1991.

evidence-based practice is in day to day use 6 Deming WE. Out of the crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press, 1986.

with the infrastructure to support it; that good 7 Evidence-based Medicine Work Group. Evidence-based

practice ideas and innovations are systemati- medicine: a new approach to teaching the practice of medi-

cine. JAMA 1992;268:2420–5.

cally disseminated and applied; that poor clini- 8 Donaldson LJ. Impact of management on outcomes. In:

cal performance is promptly recognised and Peckham M, Smith R, eds. Scientific basis of health services.

London: BMJ Publishing Group, 1986.

dealt with to prevent harm to patients; and, that 9 Berwick DM. Continuous improvement as an ideal in

the quality of data collected to monitor clinical healthcare. N Engl J Med 1982; 307:343–7.

10 Donaldson LJ, Thomson RG. Medical audit and the wider

care is itself of a high standard.2 Two new quality debate. J Public Health Med 1990;12:149–51.

external quality bodies will help to facilitate 11 Donaldson LJ. Doctors with problems in an NHS

workforce. BMJ 1994;308:1277–82.

and reinforce this local duty: a National 12 General Medical Council. The new performance procedures:

Institute for Clinical Excellence and a Com- consultative document. London: GMC, 1997.

13 Donaldson LJ. Doctors with problems in a hospital

mission for Health Improvement. workforce. In: Lens P, Wal G van der, eds. Problem doctors: a

In seeking a fundamental redefinition of the conspiracy of silence. Amsterdam: 10S Press, 1997.

14 World Bank. World Development Report: The state in a chang-

duties and accountability of public sector bod- ing world. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- T363 GCIS House Rules - Part I (IaaS DBaaS) v1.0Document23 pagesT363 GCIS House Rules - Part I (IaaS DBaaS) v1.0Linus Harri0% (1)

- 1 - Chapter 1. Introduction To Healthcare FinanceDocument1 page1 - Chapter 1. Introduction To Healthcare Financenadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- 15 - Came - Ek.50.001 PDFDocument91 pages15 - Came - Ek.50.001 PDFabu720% (1)

- Universal Declaration of Human RightsDocument8 pagesUniversal Declaration of Human RightselectedwessNo ratings yet

- TK RS 2018 Chapter 3 - Pressure For Change, in Hospitals in A Changing Europe, Open University Press, Buckingham, 2002Document23 pagesTK RS 2018 Chapter 3 - Pressure For Change, in Hospitals in A Changing Europe, Open University Press, Buckingham, 2002nadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Aw-Kars2020-1-Desain Kualitatif-Mei 152020Document89 pagesAw-Kars2020-1-Desain Kualitatif-Mei 152020nadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Residensi Kajian Swot RS Karsui Jusuf 2020Document40 pagesResidensi Kajian Swot RS Karsui Jusuf 2020nadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Health System Resilience in Managing Pandemic Covid-19Document8 pagesHealth System Resilience in Managing Pandemic Covid-19nadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Hospital Marketing Hospital Marketing: Wahyu SulistiadiDocument32 pagesHospital Marketing Hospital Marketing: Wahyu Sulistiadinadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Pembelajaran EpidDocument23 pagesPembelajaran Epidnadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Structure Literature Review Business ProcessDocument28 pagesStructure Literature Review Business Processnadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- TK RS 2018 Cambridge Memorial Hospital By-Laws (Canada)Document33 pagesTK RS 2018 Cambridge Memorial Hospital By-Laws (Canada)nadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Hospital Marketing: Concept & ImplementationsDocument46 pagesHospital Marketing: Concept & Implementationsnadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Health Policy Brief: Telehealth Parity LawsDocument5 pagesHealth Policy Brief: Telehealth Parity Lawsnadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- 4.analisis Situasi, FKK-SWOTDocument93 pages4.analisis Situasi, FKK-SWOTnadia nuraniNo ratings yet

- Inventory Is Considered To Be One of The Most Important Assets of A BusinessDocument3 pagesInventory Is Considered To Be One of The Most Important Assets of A Businesselaiza armeroNo ratings yet

- Domesticana RasquachismoDocument11 pagesDomesticana RasquachismoBlanca Caldas ChumbesNo ratings yet

- 1 - SchoolisDead - ReimerDocument29 pages1 - SchoolisDead - ReimerKarmen RežekNo ratings yet

- Learning Basic Grammar Book 2 WithDocument9 pagesLearning Basic Grammar Book 2 Withpsycho_psychoNo ratings yet

- Civil Case Digest NotebookDocument401 pagesCivil Case Digest NotebookHarrison sajorNo ratings yet

- Space Frontier Conference 10: in Search of 2001Document9 pagesSpace Frontier Conference 10: in Search of 2001Space Frontier FoundationNo ratings yet

- Manager Training & Quality - Chennai - Aegis Customer Support Services Private Limited. - 8 To 12 Years of ExperienceDocument3 pagesManager Training & Quality - Chennai - Aegis Customer Support Services Private Limited. - 8 To 12 Years of ExperienceSelecticaDeepshikha AroraNo ratings yet

- Persepolis: The Story of A Childhood and The Story of A ReturnDocument9 pagesPersepolis: The Story of A Childhood and The Story of A ReturnJihan MankaniNo ratings yet

- C TS410 2020-SampleDocument5 pagesC TS410 2020-Samplerahulg.sapNo ratings yet

- HinilawodDocument3 pagesHinilawodJennifer Joy CortezNo ratings yet

- FNCPDocument3 pagesFNCPFatima Ysabelle Marie RuizNo ratings yet

- 2016 List of Committees & Organization Reports PDFDocument2 pages2016 List of Committees & Organization Reports PDFPonnilavan SibiNo ratings yet

- Industrial and Commercial Training - Values Based LeadershipDocument8 pagesIndustrial and Commercial Training - Values Based LeadershipJailamNo ratings yet

- Joachim Hagopian v. Major General William Knowlton, 470 F.2d 201, 2d Cir. (1972)Document14 pagesJoachim Hagopian v. Major General William Knowlton, 470 F.2d 201, 2d Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Nominal Pipe Size NPS, Nominal Bore NB, Outside Diameter ODDocument5 pagesNominal Pipe Size NPS, Nominal Bore NB, Outside Diameter ODRama Krishna Reddy DonthireddyNo ratings yet

- Ultimate Frisbee HandoutsDocument4 pagesUltimate Frisbee HandoutsTinTin Laud TangcoNo ratings yet

- De 3.2Document6 pagesDe 3.2minh trungNo ratings yet

- 12109722Document4 pages12109722Hanabusa Kawaii IdouNo ratings yet

- 2015 SALN FormDocument3 pages2015 SALN FormMiamor NatividadNo ratings yet

- Ec6 JharkhandDocument103 pagesEc6 JharkhandSunilNo ratings yet

- DTM4420Document9 pagesDTM4420Cube7 GeronimoNo ratings yet

- Practice QuestionsDocument11 pagesPractice QuestionsMichaella PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Obama Illinois Attorney RegistrationDocument2 pagesObama Illinois Attorney RegistrationPamela BarnettNo ratings yet

- Daniel Lewis Lee - Preliminary Injunction LiftedDocument10 pagesDaniel Lewis Lee - Preliminary Injunction LiftedLaw&CrimeNo ratings yet

- Drinking Water Sludge Recovery Feb 2011Document2 pagesDrinking Water Sludge Recovery Feb 2011Fernando GarcíaNo ratings yet

- The Federal Polytechnic, IdahDocument3 pagesThe Federal Polytechnic, Idahwisdomeneojoufedo0147No ratings yet

- ISP For Teacher 1Document25 pagesISP For Teacher 1Carlz BrianNo ratings yet

- Basil-Great On The Holy SpiritDocument23 pagesBasil-Great On The Holy SpiritThomas Aquinas 33100% (3)