Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 viewsDeath by Negligence

Death by Negligence

Uploaded by

SAURABH DUBEYCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- CRPC hv1Document13 pagesCRPC hv1SAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- CRPC HVDocument13 pagesCRPC HVSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Whether The Order Issued by The Government of Rashtra Was Ultra Vires With Respect To The Provisions of The Disaster Management Act, 2005 ItselfDocument2 pagesWhether The Order Issued by The Government of Rashtra Was Ultra Vires With Respect To The Provisions of The Disaster Management Act, 2005 ItselfSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- 10 NALSAR BR Sawhney Moot, 2016 Best Team Memorial - PetitionerDocument10 pages10 NALSAR BR Sawhney Moot, 2016 Best Team Memorial - PetitionerSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- HIS Extract IS Taken From Harat Ydro Ower Orporation Imited V Tate OF SsamDocument13 pagesHIS Extract IS Taken From Harat Ydro Ower Orporation Imited V Tate OF SsamSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- 28 M.C. Chagla Memorial Government Law College National Online Moot Court Competition, 2021 Memorial For The PetitionersDocument40 pages28 M.C. Chagla Memorial Government Law College National Online Moot Court Competition, 2021 Memorial For The PetitionersSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Statement of JurisdictionDocument30 pagesStatement of JurisdictionSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- SAARC Script R (AutoRecovered)Document9 pagesSAARC Script R (AutoRecovered)SAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- May It Please The CourtDocument7 pagesMay It Please The CourtSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- ASU Ommentary ON THE Onstitution OF NdiaDocument7 pagesASU Ommentary ON THE Onstitution OF NdiaSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- 9NJALJ135Document35 pages9NJALJ135SAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 14.139.213.147 On Sat, 23 Apr 2022 14:13:08 UTCDocument39 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 14.139.213.147 On Sat, 23 Apr 2022 14:13:08 UTCSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Env TestDocument7 pagesEnv TestSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Principle of Unnecessary SufferingDocument25 pagesPrinciple of Unnecessary SufferingSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Rise of Nationalism in Europe Chapter-1 (History) Class-10Document28 pagesRise of Nationalism in Europe Chapter-1 (History) Class-10SAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Handbook Wildlife Law Enforcement IndiaDocument100 pagesHandbook Wildlife Law Enforcement IndiaSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Contract Assignment On BailmentDocument8 pagesContract Assignment On BailmentSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

Death by Negligence

Death by Negligence

Uploaded by

SAURABH DUBEY0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views8 pagesOriginal Title

Death by negligence

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views8 pagesDeath by Negligence

Death by Negligence

Uploaded by

SAURABH DUBEYCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 8

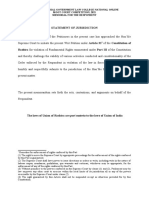

Deatu By NEGLIGENCE

Section 304A. Causing death by negligence.—Whoever causes the death of any

person by doing any rash or negligent act not amounting to culpable homicide, shall

be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to

two years, or with fine, or with both.

‘The original IPC had no provision providing punishment for causing death by negligence

Section 304A was inserted in the Code in 1870 by the Indian Penal Code (Amendment) Act

1870. It does not create a new offence. This section is directed at offences, which fall outside

the range of ss 299 and 300, where neither intention nor knowledge to cause death is present.

This section deals with homicide by negligence and covers that class of offences, where death

is caused neither intentionally nor with the knowledge that the act of the offender is likely to

cause death, but because of the rash and negligent act of the offender. This clause limits itself

to rash and negligent acts which cause death, but falls short of culpable homicide of either

description. When any of these two elements, namely, intention or knowledge, is present, s

304A has no application.

In fact, if this section is also taken into consideration, there are three types of homicides

which are punishable under the IPC, namely, (i) culpable homicide amounting to murder; (i)

calpable homicide not amounting to murder, and (iii) homicide by negligence.

Rast or Necuicenr Act

Section 304A deals with ‘death’ caused by a ‘rash’ or ‘negligent’ act.'’ However, in both the

cases, the death caused should not amount to culpable homicide.** The doing of a rash or

negligent act, which causes death, is the essence of s 304A. There is a distinction between

a rash act and a negligent act. ‘Rashness’ conveys the idea of recklessness or doing of an act

without due consideration and ‘negligence’ connotes want of proper care.®” A rash act implies

an act done by a person with recklessness or indifference as to its consequences. The doer

being conscious of the mischievous or illegal consequences, does the act knowing that his

act may bring some undesirable or illegal results but without hoping or intending them to

occut.** A negligent act, on the other hand, refers to an act done by a person without raking

sufficient precautions or reasonable precautions to avoid its probable mischievous or illesi

consequences. it implies an omission to do something, which a reasonable man, in che given

circumstances, would not do.”

83. Raghunath Babesa v State of Orissa (1968) Cr LJ 851 (Ori); State of Gujarat v Haidarali AIR. 1976 SC 1012.

84. Shankar Narayan Bhadotkar v State of Maharashtra AIR 2004 SC 1966, (2005) 9 SCC 71; Prabhakanen

ile (2007) 14 SCC 269, AIR 2007 SC 2378; Kuldeep Singh v State of Himachal Pradesh AUR 200!

Mahadev Prasad Kaushik v State of Usiar Pradesh (2008) 14 SCC 479, AIR 2009 SC 1

85. By virtue of s 32, IPC, the rerm ‘act’ also includes an ‘illegal omission’. Therefore d

‘omission resulting from negligence comes within the purview of s 304A. S

Sarkar (1968) Cr L} 405 (Cal),

86 State of Gujarat v Haiderali AIR 1976 SC 1012,

87 Emperor v Abdul Latif AVR 1944 Lah 163,

88 See Pitala Yadagiri v State of Andina Pradesh (1991) 2 Cris

Cr LJ 2142 (Del).

See Re JC May AIR 1960 Mad 50; Padmacharan v State of Orissa (1982) Cr LJ (NOC) 192 (Ori); Mahadew

Prasad Kaushik v State of Uttar Pradesh (2008) 14 SCC 479, AIR 2009 SC 125.

nes 359 (AP); Shiv Dev Singh v State (Delbi) (1995)

89

588

Scanned with CamScann

Fromiciae

The term ‘negligence’ as used in this section does not mean mere aon

or negligence must be of such nature so a5 (0 be termed as a criminal act of

vachness, Section 80 of the IPC provides ‘nothing is an offence which is done by

wrfortune and without any criminal knowledge or intention in the doing of a las

a lawfal manner by a lawful means and with proper care and caution’, It is absent

proper care and caution, which is required of a reasonable man in doing an act, which

punishable under this action.

Ieis the degree of negligence that really determines whether a particular act would amor

coa rash and negligent act as defined under this section. I is only when the rash and negligent

act is of such a degree that the risk run by the doer of the act is very high or is done with

such recklessness and with total disregard and indifference to the consequences of this act,

the act can be constituted as a rash and negligent act under this section. Negligence is the

grass and culpable neglect or failure to exercise reasonable and proper care, and precaution £0

guard against injury, either to the public generally or to an individual in particular, which a

reasonable man would have adopted.”

In Cherubin Gregory v State of Bihar?" the deceased was an inmate of a house near that

of the accused. The wall of the latrine of the house of the deceased had fallen down a week

prior to the day of occurrence, with the result that his latrine had become exposed to public

view, Consequently, the deceased, among others, started using the latrine of the accused. The

accused resented this and made it clear to them that they did not have his permission to use

it and protested against their coming there. The oral warnings, however, proved ineffective.

Therefore, the accused fixed a naked arid uninsulated live wire of high voltage in the passage

to the latrine, to make entry into his latrine dangerous to intruders. There was no warning put

up that the wire was live. The deceased managed to_pass into the latrine without contacting

the wire, but as she came out, her hand happened to touch it, she got « shock and died because

of.

Tc was contended on behalf of the accused that he had a right of private defence of property

and death was caused in the course of the exercise of thar right, as the deceased was a trespasser.

The Supreme Court rejected the contention stating thar the mere fact that the person entering

sland is 2 trespasser does not entitle the owner or occupier to inflict on him personal injury

by direct violence. The court observed that it is no doubt true that the trespasser enters the

property at his own tisk and the occupier owes no duty to take any reasonable care for his

protection, but at the same time, the occupier is not entitled ro wilfally do any act, such as

setting a trap of naked live wire of high voltage, with the deliberate intention of causing harm

to trespassers or in reckless disregard of the presence ofthe trespasser. Ie was held thar since the

trespasser died soon after the shock, the owner who set up the trap was guilty under s 304A,

IPC. The Supreme Court upheld the conviction of the accused,

“An assistant station master gave a ‘line clear’ signal to a passenger train with the knowledge

that a goods train was standing, at a particular point, where the train might collide, hoping

to remove the goods train before the arrival of the passenger train, ‘The goods train was not

removed in time and a collision occurred which was attended with loss of life, The assistant

Jn act punishable under this section.’

station master was held guilty of ar

90 SN Husain v State of AP AIR 1972 SC 685; State of Himachal Pradesh v Mobinder Singh (1989) 2 Crimes 159%

Rayan v State of AP (1994) Cx L} 78 (AP): Surender Kumar v Stae of Urear Pradesh (1996) Ce 13 94 (All).

91 AIR 1964 SC 205, (1964) Cr L] 138 (SC).

99 amp rove All 470

scanned witn Gamscann

asl SED SRLS Sa 8 ogg ee

2 /ABSENCE OF INTENTIONAL ‘VIOLENCE

/ 1 he ees aaa isha the act which has resulted in the death ofa person, should not

bape ee tention of causing cleath, Voluntary and intentional acts either wich

ae neo ae death or the knowledge that the at is likely to cause death, will meune

In Sarabjeet Singh v State of Uttar Pradesh the accused was part of an unlawful assembly

and attacked the opposite party. He had come to attack the father of the deceased (who we

a small child of about four years). With a view of causing some harm and raking vengeance

on the father of the young child, he threw the innocent child on the ground. The Supreme

Court held that the act of throwing the child on the ground could not be called as rash with

the meaning of s 304A, as he had knowledge that his act was likely to cause death. Under the

circumstances, it would amount to culpable homicide under s 299 and punishable under +

304, Pr Il, IPC.

DearH Most Be THE Direct REsutt

In order to impose criminal liability under this section, itis essential to establish that death is

the direct result of the rash and negligent act of the accused. It must be cause causans—the

immediate cause, and it is not enough that it may be causa sine qua non—the proximate

cause.95

In Suleman Rahiman Mulam v State of Maharashtra, the accused, who was driving 2 jeep

struck the deceased, as a result of which he sustained serious injuries. The accused put the

injured person in the jeep for medical treatment, but he died. Thereafter, the accused cremated

the body. The accused was charged under ss 304A and 201, IPC. As per s 304A, there must

be a direct nexus between the death of a person and rash and negligent act of the accused

that caused the death of the deceased. It was the case of the prosecution that the accused had

possessed only a learner’ licence and hence, was guilty of causing the death of the deceased.

‘The Supreme Court held that there was no presumption in law that a person who possesses

only a learner's licence or possesses no licence at all does not know driving. A person could,

for various reasons, including sheer indifference, might not have taken a regular licence. There

was evidence to show that the accused had driven the jeep to various places on the previous day

of the occurrence. So, before the accused is convicted under s 304A, there must be proof that

the accused drove in a rash and negligent manner and the death was a direct consequence of

such rash and negligent driving, In the instant case, there was absolutely no evidence chat the

accused had driven in a rash and negligent manner. In the absence of such evidence, no offence

under s 304A was made out. The accused was acquitted of the charges

In Ambalal D Bhatt v State of Gujarat,” the accused was a chemist in charge of the injection

department of Sanitax Chemical industries Limited, Baroda, The company prepared glucose in

normal saline, a solution containing dextrose, distilled water and sodium chloride. The sodium

93 AIR 1983 8C 529,

94 Kurban Husain v State of Maharashtra (1965) 2 SCR 622; Satya Prakash Choudhary v State of Madhya Pradeb

(1990) Cr LJ (NOC) 132 (MP).

95. Ma Rangawalla v State of Maharashtra AIR 1965 SC 1616.

96 AIR 1968 SC 829, (1968) Cr LJ 1013 (sc).

97 AIR 1972 SC 1150,

scanned witn Gamscann

chloride sometimes contained quantities of lead nitrate, the permissible limit for lead nitrate

being five parts in one million. The saline solution, which was supplied by the company, was

found to have lead nitrate higher than the permissible limits and hence was dangerous to

human life. The bottles, which were sold by the company, were purchased by different hospitals

and nursing homes and were administered to several patients of whom 12 patients died, As

per the Drugs Act 1940, and the rules framed thereunder, a chemist of a chemical company

has to give a batch number to every lot to bottles containing preparation of glucose in normal

saline. The accused, who was responsible for giving the batch numbers, failed to do so. He gave

asingle batch number to four lots of saline. Ic was the contention of the prosecution that had

the appellant given separate batch numbers to each lot as requited under the rules, the chief-

analyst would have separately analysed each lot and would have certainly discovered the heavy

deposits of lead nitrate in the sodium chloride and the lot which contained lead would have

been rejected, As the accused had been negligent in conforming to the rules, the deaths were

the direct consequence of the negligence. The Supreme Court held that for an offence under

8304A, the mere fact that an accused contravened certain rules or regulations in the doing of

an act which caused death of another, does not establish that the death was the result of a rash

or negligent act or that any such act was a proximate and sufficient cause of the death. It was

established in evidence that it was the general practice prevalent in the company of giving one

batch number to different lots manufactured in one day. This practice was to the knowledge

of the drug inspector and to the production superintendent, The coust held that the drug

inspector himself knew fully well chat this was the practice, but did not lifta finger to prohibie

the practice and instead turned his blind eye(to a serious contravention of the drug rules. To

hold the accused responsible for the contravention of the rule would be to make an attempt to

| somehow find the scapegoat for the deaths of the 12 persons. Accordingly, the conviction of

| theaccused under s 304A was set aside.”

i

{

|

|

Difference Between Rashness and Negligence

Arash act is primarily an overhasty act.” Negligence is a breach of a duty caused by omission

to do something, which a reasonable man guided, by those considerations which ordinarily

regulate the conduct of human affairs would do.'

In Bhalachandra Waman Pathe v State of Maharashtra," the Supreme Court explained che

distinction between a rash and a negligent act in the following manner:

There is a distinction between a rash act and a negligent act. In the case of a rash act, the criminality

lies in running the tisk of doing such an act with recklessness or indifference as to the consequence

Criminal negligence is the gross and culpable neglect or failure to exercise that reasonable and

proper care and precaution to guard against injury either to the public generally or to an individual

in particular, which, having regard to all the circumstances out of which the charge his arisen, it

was the imperative duty of the accused person to have aclopeed. Negligence is an omission co do

something which a reasonable man, guided upon those considerations which ordinarily regulate

the conduct of human affairs would do, or doing something which a prudent and reasonable man

98 See also Baijnath Singh v State of Bihar AIR 1972 SC 1485.

99. Balwant Singh v State of Punjab 1994 SCC (Cri) 84,

100 Hi: igh Gour, Penal Law of India, vol 3, 11th edn, Law Publishers, Allahabad, 1998, p 3028.

101 (1968) 71 Bom LR 634 (SC), (1968) SCD 198,

Scanned with CamScanne

would not do. A culpable rashness is acting with the consciousness that the mischievous and illegal

consequences may follow, but with the hope that they will not, and often with the belief that the

actor has taken sufficient precautions to prevent their happening, The imputability arises from

acting despite the consciousness, Culpable negligence is acting without the consciousness that the

illegal and mischievous effect will follow, but in circumstances which show that the actor has not

exercised the caution incumbent upon him and if he had, he would have had the consciousness,

‘The imputability arises from the neglect of the civic duty of circumspection,

nes

In the instant case, the appellant was drivin,

¢ g his car at a speed of 35 miles an hour, the speed

permiss

le under the rules. No other circumstance was pointed out to show that he was drivin

ina teckless manner. Therefore, he cannot be said to have been running the risk of doing an act

wich recklessness or indifference as to the consequences. However, he was undoubtedly guilty

of negligence. He had a duty to look ahead and see whether there was any pedestrian in the

Pedestrian crossing, Its likely chat while driving the car, he was engrossed in talking with the

Person who was sitting by his side. By doing so, he failed to exercise the caution incumbent

upon him. His culpable negligence and failure to exercise that reasonable and proper care and

caution required of him resulted in the occurrence. He was therefore held guilty of the offence

punishable under s 304A.

Rast AND Necuicenr Act in Driving ALonG 4 Pusuic Hichway

Generally, a person who is driving a motor vehicle is expected to always be in control of the

vehicle in such a manner as to enable him to prevent hitting against any other vehicle or

running over any pedesttian, who may be on the road. In Baldeyji v State of Gujarat,” the

accused had run over the deceased while the deceased was trying to cross over the road, The

accused did not attempt to save the deceased by swerving to the other side, when there was

sufficient space. This was a result of his rash and negligent driving. His conviction under

304A, IPC, was upheld.

In Dui Chand v Dethi Administration,!® the accused was driving a public transport bus,

and he had reached a crossroad. At that time, although he was not going at a great speed,

he failed to look co his right and thus did not see the deceased, who was coming from his

right and was crossing the toad, The main road was 42 feet wide and had the accused been

reasonably alert and careful, he would have seen the deceased coming from his right trying to

cross the road, and in that event he could have immediately, applied the brake and brought

the bus to a grinding hale. The act of the accused in failing to look to his right, although he

was approaching a crossroad, amounted to culpable homicide on his part and hence, he was

convicted under s 304A, IPC.!

In Thakur Singh v State of Punjab," the Supreme Court held the driver of a bus, carrying 41

passengers, while crossing a bridge, fell into a nearby canal resulting death ofall che passengers,

guilty of rash and negligent driving. Refuting his plea that the prosecution failed to prove

negligence on his part, the court invoked the doctrine of res ipsa loguitur to shift che onus of

proof to him to prove that the accident did not happen due to his negligence. In view of the

102

103 ALR 1975 Si

104 Bur see State v

lus (2003) 9 S

1327.

1960.

fohammad Yusuf (2001) Cr LJ 5 (SC).

208,

scanned witn Famscann

errno

aalloping trend in road accidents in India and the devastating consequences thereof ond

a ioc ead their families, the apex court refused to give benefits of benevolent provisions 0

ys bation of Offenders Act 1958. Ic also stressed the need to impose deterrent punishment

ai aaite and callous drivers of automobiles to make them careful drivers and thereby

‘dents.

bring down the high rate of motor accidents." =

ip Nano Girt» State of Madhya Pradesh wherein death and injury caused to passengers

wen the bus driver attempted to cross a unmanned railway ctossing and hit by a passing

«ain, the Supreme Court altered the charges from s 304 to 304A on the ground that his gross

negligence,

Rast on NEGLIGENT ACT IN MEDICAL TREATMENT

Courts have repeatedly held that great care should be taken before impuiting criminal rashness

or negligence to a professional man acting in the course of his professional duties. A doctor is

not criminally liable for a patient's death, unless his negligence or incompetence passes beyond

amere matter of competence and shows such a disregard for life and safety, as to amount to a

atime against the state.

In Jobn Oni Akerele’ case," a medical: practitioner had administered a medical dose of

serbtal injection to a child, because of which the child died: The doctor was charged under s

5044, IPC. The contention of the accused doctor was thac the child was peculiarly susceptible

to the medicine and therefore unexpectedly succumbed to a dose which would have been

barmless in case of a normal child. The Privy Council held that the doctor was guilty of

criminal negligence.

In Juggan Khan v State of Madhya Pradesh the accused was a registered homeopath who

had administered co a patient suffering from guinea worm, 24 drops of stramonium and a leet

of dashura without properly studying its effect. The patient died as a result of the medicine

given by the accused. Stramonium and dathuna ate poisonous. So, giving the same withous

being aware of its effects was held to be a rash and negligent act. The accused was conviceed

under s 304A, IPC, and sentenced to two years rigorous imprisonment.

When a hakim gave a procaine penicillin injection to a patient because of which he died, it

was held that the hakim was guilty under s 304A.

In Ram Niwas v State of Uttar Pradesh" the accused, an unqualified doctor, treated a

five-year old boy who was suffering from fever. He administered an injection to the boy upon

which the boy turned blue and his condition worsened. Thereaeet, the boy died, Accorling

to the evidence, the accused did not administer the injection after giving any test dose to the

boy. In view of the fac that the accused was not a qualified medical practioner who had given

an injection to the boy without giving any test dose, the coure held that he hacl acted wich

tashness, recklessness, negligence and indifference to the consequences, Icamounted to taking

hazard of such degree that the injury was most likely to be occasioned thereby. ‘The court held

106 See also Murari v State of Madhya Pradesh (2001) Cr LJ 2968 (

SCC 82; Suyambu w State (2001) Cr LJ 1577 (SC).

107 AIR 2007 SC 7104, 2007 (13) SCALE 7

108 AIR 1943 PC 72, (1944) Cr LJ 569 (PC).

109 AIR 1965 SC 831

M0 (1998) Cr L} 635 (AID,

Dalbir Singh v State of Haryana (2000) 3

8 scannea witn Camscannt

that it was amply established that the accused catised

. , sect ca the death of ,

said rash and. negligent act which did not amount to culpable ee ost yy ding fe

accused was guilty under s 304A, IPC, cide and held that the

However, during the recent past the Sup

ae : ; ipteme Court has attributed a diffe

Heahietes when it on to a professional, particularly, a medical prcticioner | “andi

in Suresh Gupta (Dr) v Gout of NCT of Delhi & Anon! ;

ce ees rei of ior," the Supreme Court held that for

t the standard of negligence should not merely be lack of

necessary care, attention and skill. The standard of negligence required to be proved should

be so high as can be described as ‘gross negligence’ or ‘recklessness. With this perception, the

court observed:

---[W]hen a patient agrees to go for medical treatment or surgical operation, every careless act of

the medical man cannot be termed as ‘criminal’. It can be termed ‘criminal’ only when the medical

man exhibits a gross lack of competence or inaction and wanton indifference to his patient’ safety

and which is found to have arisen from gross ignorance oF gross negligence. Where a patient’ death

results merely from error of judgment or an accident, no criminal liability should be attached to it

Mere inadvertence or some degree of want of adequate care and caution might create civil liability

but would not suffice to hold him criminally liable." ... [T]he act complained against the doctor

must show negligence or rashness of such a higher degree as to indicate a mental state which can be

described as totally apathetic towards the patient. Such gross negligence alone is punishable."

In Jacob Mathew v State of Punjab & Anor!'* the Supreme Court not only approved the

principle laid down in the Dr Gupta case but also opined that ‘negligence in the context of

medical profession necessarily calls for a treatment with a difference...a case of occupational

nepligence is different from one of professional negligence.’ Delving into liabilicy of a doctor

for his rash or negligent act leading to death of his patient, it ruled that:

.. (A] professional may be held liable for negligence on one of the two findings: cither he was not

possessed of the requisite skill which he professed to have possessed, or, he did nor exercise, with

reasonable competence in the given case, the skill which he did possess. The standard co be applied

for judging, whether the person charged has been negligent or not, would be that of an ordinary

competent person exercising ordinary skill in that profession."'>

Recently, in Martin F D'Souza v Mohd, Ishfag,™® the Supreme Court, after making a suey

of thitherto judicial pronouncements on medical negligence, reiterated, with approval, chat

the Jacob Mathew dictum holds good in handling cases of medical negligence. It endorsed the

concept of gross negligence delved in Jacob Mathew and stressed that the degree of negligence

sufficient to fasten criminal liability for medical negligence has to be higher than that requited

to fasten civil liability. For holding a medical practitioner guilty under se 304A, gross negligence

on his part amounting to recklessness needs to be proved, For judicial determination of such

negligence, the court has to rely upon evidence of medical professionals,

111 AIR. 2004 SC 4091, (2004) 6 SCC 422, Followed in Karcherala Venkata Sunil v Dr. Vanguri Seshumamba (2008)

Cr Ly 853 (AP),

112 Ibid, para 20,

113 Ibid, para 25.

114 (2005) 6 SCC 1,

115. Ibid, para 53.

116 (2009) 3 SCC 1, AIR 2009 SC 2049.

scanned witn Famscann

PUNISHMENT

The punishment prescribed under this section is simple or rigorous imprisonment fora t

up to two years, or with fine, or with both, Sentence in cases arising under this section is a

matter of discretion of the trial court.'"” Sentence depends on the degree of carelessness seen

in the conduct of the accused,'"* Though, contributory negligence is not a factor, which can

be taken into consideration on the question of the guilt of the accused," it can be a factor for

consideration in determination of sentence.

Scanned with CamScann«

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- CRPC hv1Document13 pagesCRPC hv1SAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- CRPC HVDocument13 pagesCRPC HVSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Whether The Order Issued by The Government of Rashtra Was Ultra Vires With Respect To The Provisions of The Disaster Management Act, 2005 ItselfDocument2 pagesWhether The Order Issued by The Government of Rashtra Was Ultra Vires With Respect To The Provisions of The Disaster Management Act, 2005 ItselfSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- 10 NALSAR BR Sawhney Moot, 2016 Best Team Memorial - PetitionerDocument10 pages10 NALSAR BR Sawhney Moot, 2016 Best Team Memorial - PetitionerSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- HIS Extract IS Taken From Harat Ydro Ower Orporation Imited V Tate OF SsamDocument13 pagesHIS Extract IS Taken From Harat Ydro Ower Orporation Imited V Tate OF SsamSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- 28 M.C. Chagla Memorial Government Law College National Online Moot Court Competition, 2021 Memorial For The PetitionersDocument40 pages28 M.C. Chagla Memorial Government Law College National Online Moot Court Competition, 2021 Memorial For The PetitionersSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Statement of JurisdictionDocument30 pagesStatement of JurisdictionSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- SAARC Script R (AutoRecovered)Document9 pagesSAARC Script R (AutoRecovered)SAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- May It Please The CourtDocument7 pagesMay It Please The CourtSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- ASU Ommentary ON THE Onstitution OF NdiaDocument7 pagesASU Ommentary ON THE Onstitution OF NdiaSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- 9NJALJ135Document35 pages9NJALJ135SAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 14.139.213.147 On Sat, 23 Apr 2022 14:13:08 UTCDocument39 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 14.139.213.147 On Sat, 23 Apr 2022 14:13:08 UTCSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Env TestDocument7 pagesEnv TestSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Principle of Unnecessary SufferingDocument25 pagesPrinciple of Unnecessary SufferingSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Rise of Nationalism in Europe Chapter-1 (History) Class-10Document28 pagesRise of Nationalism in Europe Chapter-1 (History) Class-10SAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Handbook Wildlife Law Enforcement IndiaDocument100 pagesHandbook Wildlife Law Enforcement IndiaSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Contract Assignment On BailmentDocument8 pagesContract Assignment On BailmentSAURABH DUBEYNo ratings yet