Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Class TCM CVM

Class TCM CVM

Uploaded by

shubham0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

48 views34 pagesThe travel cost method values environmental goods and services based on the costs people incur to visit them. It assumes that travel costs are a proxy for the minimum value of visiting a site. The method involves collecting data on visits from different distances to estimate the demand function for the site. Regression analysis is used to relate visits to travel costs and other variables to estimate consumer surplus, the total economic benefit people receive from visiting the site. The travel cost method can be extended to value specific site characteristics using a hedonic travel cost model.

Original Description:

Original Title

Class Tcm Cvm

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe travel cost method values environmental goods and services based on the costs people incur to visit them. It assumes that travel costs are a proxy for the minimum value of visiting a site. The method involves collecting data on visits from different distances to estimate the demand function for the site. Regression analysis is used to relate visits to travel costs and other variables to estimate consumer surplus, the total economic benefit people receive from visiting the site. The travel cost method can be extended to value specific site characteristics using a hedonic travel cost model.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

48 views34 pagesClass TCM CVM

Class TCM CVM

Uploaded by

shubhamThe travel cost method values environmental goods and services based on the costs people incur to visit them. It assumes that travel costs are a proxy for the minimum value of visiting a site. The method involves collecting data on visits from different distances to estimate the demand function for the site. Regression analysis is used to relate visits to travel costs and other variables to estimate consumer surplus, the total economic benefit people receive from visiting the site. The travel cost method can be extended to value specific site characteristics using a hedonic travel cost model.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 34

Valuation of Environmental Goods

ENVIRONMENTAL ECONOMICS

Mrinal Kanti Dutta

mkdutta@iitg.ac.in

Department of Humanities and Social Sciences

Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati

Guwahati – 781039

2

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

One of the oldest approaches to environmental valuation

Proposed in a letter from Harold Hotelling to the US Forest

Service in the 1930’s, first used by Wood and Trice in 1958,

popularized by Clawsen and Knetsch (1966)

Premises

• People bear cost to visit regions or sites (national park or

estate)

• Hypothesis : These costs are at least equal to the minimum

value of the benefit people get when visiting the sites and their

environmental goods or services. Thus these travel costs can

be used as a proxy for the price of visiting outdoor recreational

sites . (In other words, the recreational benefits at a specific site

can be derived from the demand functions that relate observed

user’s behaviour to the cost of visit.)

3

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

Steps of analysis

• Estimate the cost of travel and visit for each regions

of origin

• Questionnaire : visitors trip, expenses and

characteristics

•Estimate of the demand for the site (and

environmental goods and services) depending on

the cost of travel and visit and other characteristics

4

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

Options for Applying the Travel Cost Method

1. A simple zonal travel cost approach, using mostly secondary

data, with some simple data collected from visitors. The

zonal travel cost method is applied by collecting information

on the number of visits to the site from different distances.

2. An individual travel cost approach, using a more detailed

survey of visitors. The individual travel cost approach is

similar to the zonal approach, but uses survey data from

individual visitors in the statistical analysis, rather than data

from each zone. This method thus requires more data

collection and slightly more complicated analysis, but will

give more precise results.

5

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

3. Hedonic Travel Cost Model which attempts to place

values on the characteristics of recreational resources.

4. A random utility approach using survey and other data,

and more complicated statistical techniques. The

random utility approach assumes that individuals will

pick the site that they prefer, out of all possible sites.

Individuals make tradeoffs between site quality and the

price of travel to the site. Hence, this model requires

information on all possible sites that a visitor might

select, their quality characteristics, and the travel costs

to each site.

6

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

The travel cost method is applied by collecting

information on the number of visits to the site from

different distances. Because the travel and time costs

will increase with distance, this information allows the

researcher to calculate the number of visits purchased

at different prices: the demand function and the

consumer surplus or economic benefits, for the

recreational services of the site.

Step 1: The first step is to define a set of zones

surrounding the site. These may be defined by

concentric circles around the site, or by geographic

divisions that make sense, such as metropolitan areas

or counties surrounding the site at different distances.

7

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

Step 2: The second step is to collect information on the

number of visitors from each zone, and the number of

visits made in the last year.

Step 3: The third step is to calculate the visitation rates

per 1000 population in each zone. This is simply the

total visits per year from the zone, divided by the

zone’s population in thousands.

Step 4: The fourth step is to calculate the average

round-trip travel distance and travel time to the site for

each zone, using average cost per mile (km) and per

hour of travel time. What is the opportunity cost of

time?

8

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

Step 5: The fifth step is to estimate, using regression

analysis, the equation that relates visits per capita to

travel costs and other important variables.

From this, the researcher can estimate the demand

function for the average visitor. In this simple model,

the analysis might include demographic variables,

such as age, income, gender, and education levels,

using the average values for each zone

9

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

Step 6: The sixth step is to construct the demand

function for visits to the site, using the results of the

regression analysis. The first point on the demand

curve is the total visitors to the site at current access

costs (assuming there is no entry fee for the site)

Step 7: The final step is to estimate the total economic

benefit of the site to visitors by calculating the

consumer surplus, or the area under the demand

curve.

10

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

Simple Travel Cost Model:

If the price (p) is the only sacrifice made by a

consumer, the demand function for a good with no

substitutes is x=f(p), given income and preferences.

However, the consumer often incurs other costs (c),

such as travel expenses and loss of time. In this

case, the demand function is expressed as x = f(p, c).

Under these conditions, the utility maximising

consumer’s behaviour should be reformulated in

order to take such costs into account.

11

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

Simple Travel Cost Model:

Given two goods or services (x1, x2), their prices (p1, p2), the

access costs (c1, c2) and income (R), the utility maximizing

choice of the consumer is:

MaxU = u(x1,x2)

Subject to: (p1 + c1) x1 + (p2 + c2)x2 = R (1)

Now, let 'x1' denote the aggregate of priced goods and

services, x2 the number of annual visits to a recreational site,

and assume for the sake of simplicity that the cost of access to

the market goods is negligible '(c1=0)' and that the recreational

site is free (p2=0).

12

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

Under these assumptions, equation [1] can be written

as:

MaxU = u(x1,x2))

Subject to: p1x1 + c2x2 = R (2)

Under these conditions, the utility maximizing

behaviour of the consumer depends on:

a) His preferences [u(x1, x2)],

b) His budget (R),

c) The prices of the private goods and services

(p1) and

d) The access cost to the recreational site (c2).

13

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

The TCM is based on the assumption that changes in the costs

of access to the recreational site (c2) have the same effect as a

change in price: the number of visits to a site decreases as the

cost per visit increases.

Under this assumption, the demand function for visits to the

recreational site is x2=f(c2) and can be estimated using the

number of annual visits as long as it is possible to observe

different costs per visit and up to the cost at which visits

become equal to zero.

This simple model can be extended to include the effect of

other substitute sites.

Alternatively, same model can be used to estimate visits per

time be an individual to site with c and p becoming specific to

the individual only.

14

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

The basic TCM model is completed by the weak

complementarity assumption, which states that trips

are a non-decreasing function of the quality of the site,

and that the individual forgoes trips to the recreational

site when the quality is the lowest possible

15

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

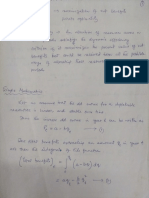

c2 The Figure depicts

cp the expected

relationship

between the

number of visits

and cost per visit,

c2p given other

variables, showing

that the number of

visits decreases as

c2c

the cost per visit

increases.

o x2p x2c

x2

16

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

Hedonic Travel Cost Model:

On many occasion, we are interested in the value of

changing characteristics of a site rather than in the

value of the site in toto.

In this respect, hedonic travel cost model attempts

to place values on the characteristics of recreational

resources.

Hedonic travel cost model was first proposed by

Brown and Mendelsohn (1984) and was later

applied to forest characteristics by Englin and

Mendelsohn (1991) and coastal water quality by

Bockstael et. al. (1987)

17

Valuation of Environmental Goods

Hedonic Travel Cost Model:

Steps:

1. Respondents to a number of sites (e.g. forest) are

sampled to determine their zone of origin.

The levels of physical characteristics are recorded

for each site

A travel cost function is estimated for each zone, as

C(Z) = c0 + c1z1 + c2z2 + … cmzm (1)

Where, C(Z) are travel costs, z1 . . . zm are

characteristics and c0 . .. cm are coefficients to be

estimated.

18

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

Hedonic Travel Cost Model:

Steps:

A separate regression is performed for each zone

of origin such that each will have a vector of

coefficients {c0… cm}. For a given characteristics m,

the utility maximising individual will choose visits

such that the marginal costs of characteristics (the

coefficient cm) is just equal to the marginal benefit

to him.

19

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

Hedonic Travel Cost Model:

Steps:

2. Estimate a demand curve for each

characteristics regressing a site characteristic

levels (dependent variable) against the predicted

marginal cost of that characteristic and

socioeconomic variables for each zone of origin.

A separate regression is run for each

characteristics.

The expectation is that the coefficient on the

marginal cost variable will be negative implying that

as the level of a characteristics rises people are

unwilling to pay as much for each further increment.

20

Valuation of Environmental Goods

Issues and Limitations of the TRAVEL COST METHOD

The travel cost method assumes that people perceive and

respond to changes in travel costs the same way that they

would respond to changes in admission price.

Defining and measuring the opportunity cost of time, or the

value of time spent on traveling, can be problematic. Because

the time spent on traveling could have been used in other

ways, it has an "opportunity cost." This should be added to the

travel cost, or the value of the site will be underestimated.

However, there is no strong consensus on the appropriate

measure: the person’s wage rate, or some fraction of the

wage rate and the value chosen can have a large effect on

benefit estimates.

21

Valuation of Environmental Goods

Issues and Limitations of the TRAVEL COST METHOD

If people enjoy the travel itself, then travel time

becomes a benefit, not a cost, and the value of the

site will be overestimated. The availability of

substitute sites will affect values.

The most simple models assume that individuals

take a trip for a single purpose: to visit a specific

recreational site.

Interviewing visitors on site can introduce sampling

biases to the analysis.

22

Valuation of Environmental Goods

Issues and Limitations of the TRAVEL COST METHOD

Measuring recreational quality, and relating

recreational quality to environmental quality can be

difficult.

Standard travel cost approaches provide information

about current conditions, but not about gains or losses

from anticipated changes in resource conditions.

In order to estimate the demand function, there needs

to be enough difference between distances travelled

to affect travel costs and for differences in travel costs

to affect the number of trips made. Thus, it is not well

suited for sites near major population centers where

many visitations may be from "origin zones" that are

quite close to one another.

23

Valuation of Environmental Goods

TRAVEL COST METHOD

The travel cost method is limited in its scope of

application because it requires user participation. It

cannot be used to assign values to on-site

environmental features and functions that users of the

site do not find valuable.

Most importantly, it cannot be used to measure non-

use values. Thus, sites that have unique qualities that

are valued by non-users will be undervalued.

As in all statistical methods, certain statistical

problems can affect the results. These include choice

of the functional form used to estimate the demand

curve, choice of the estimating method, and choice of

variables included in the model.

24

Valuation of Environmental Goods

CONTINGENT VALUATION METHOD

Contingent Valuation Method (CVM) was first used

by Davis (1963) in a study of hunters in Maine and

it was widely developed with Bohm (1972), Randal

et.al. (1974), Brookshire et. al., (1976) etc.

The essence of CVM method involves asking

individual to imagine some situation that is

typically outside the individual’s experience and

speculate on how he or she would act in such a

situation.

It is called 'contingent valuation' because the

valuation is contingent on the hypothetical

scenario put to respondents.

25

Valuation of Environmental Goods

CONTINGENT VALUATION METHOD

CVM exercise can be split in to five stages:

Setting up the hypothetical market

Obtaining bids

Estimating mean WTP and or WTAC

Estimating bid curves

Aggregating the data

26

Valuation of Environmental Goods

CONTINGENT VALUATION METHOD

As Carson (1991) noted, there are six main

component of a successful CV study:

1. Define Market Scenario

2. Choose elicitation method

3. Design market administration

4. Design sampling

5. Design of experiment

6. Estimate willingness-to-pay function

27

Valuation of Environmental Goods

CONTINGENT VALUATION METHOD

1. Define Market Scenario:

Is the information to be conveyed to a respondent?

(i.e. one who will be asked about willingness to

pay)

To place the respondent in the right time frame of

mind to give meaning response to questions

Description of the market should be realistic to the

respondent and

Defining appropriate payment mechanism

28

Valuation of Environmental Goods

CONTINGENT VALUATION METHOD

2. Choosing Elicitation Method:

Having properly defined the market scenario, the next step is

to decide how best to obtain the valuation process.

There are four ways of eliciting value: direct question, bidding

game, payment card and referendum choice.

2.1 Under direct questioning the main task is to ask the

respondents about their willingness to pay for the good.

However, this suffers from a great demerit in the sense that

there are few real markets in which we ask the respondent

to generate data and in most occasion people may not

spend much effort in determining their willingness to pay

which may result in extreme response (either zeroes and

very large numbers)

29

Valuation of Environmental Goods

CONTINGENT VALUATION METHOD

2.2 Bidding Game:

Bidding game approach was first used by Randal

et.al (1974).

This approach involves a WTP number and seeks a

yes-no response.

If the respondent replies yes, the amount is gradually

increased until a no response is received. Similarly, if

the respondent replies no, the amount is gradually

decreased until a yes is received. The main problem

with this approach is the starting-point bias.

30

Valuation of Environmental Goods

CONTINGENT VALUATION METHOD

2.3 Payment Card: A card with a number of figures, spanning

the range of responses that might be expected. Each card has

payment amounts along with several reference expenditure

amount.

The basic problem with the payment card is that they can not be

used for telephone surveys.

2.4 Referendum or discrete choice:

Under this approach a willingness to pay figure is offered to the

respondent who is asked if he or she would be willing to pay that

amount, ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

This approach although has the merit of minimizing possible

bias and is also familiar to the people in that people often vote

yes/no on public referenda. One problem with referenda is that

more data are needed to obtain statistically significant results

which raised cost of the survey.

31

Valuation of Environmental Goods

CONTINGENT VALUATION METHOD

3. Design Market Administration:

Three approaches to survey administration: mail,

telephone and in-person

Mail Survey: cheaper to administer but suffers from

the problem of acute non-response

Telephone Survey: relatively inexpensive to

administer but limited by the availability of telephone

within the population being surveyed.

In-person Survey: Most expensive to administer but

can be more reliable. However it suffers from the

problem of interviewer bias.

32

Valuation of Environmental Goods

CONTINGENT VALUATION METHOD

4. Sample Design:

It involves two steps: First, select the group (relevant

for the study) from which to draw the sample.

Second, draw the random sample.

5. Experimental Design:

Experimental design requires careful design of

survey instrument, its administration and its ultimate

statistical analysis.

33

Valuation of Environmental Goods

CONTINGENT VALUATION METHOD

6. Estimation of Willingness to Pay Function:

The last step of the Contingent Valuation Method is

to take the survey results and correctly estimate the

WTP functions.

Problems with the Contingent Valuation Methods:

Despite significant application of CV technique in

eliciting values of environmental goods, the method

has been scrutinized and found to suffer from a large

number of limitations. Following are the important

limitations of this method:

34

Valuation of Environmental Goods

The value elicited in CV surveys are not based on real

resource decisions - they are hypothetical.

Presence of ambiguity in what people are valuing

Problem of embedding. This problem generally pertains

to the inconsistencies that people face when they are to

value an environmental good (e.g. park) versus a group

of environmental goods (several parks in our case) when

they are substitutes.

Another related problem is the valuation of existence

value.

You might also like

- UP System Administration Citizen's Charter Handbook - FINAL PDFDocument631 pagesUP System Administration Citizen's Charter Handbook - FINAL PDFCSWCD Aklatan UP DilimanNo ratings yet

- NikeprimeDocument35 pagesNikeprimeapi-283961218No ratings yet

- Travel Cost MethodDocument68 pagesTravel Cost Methodyayaskyu0% (1)

- Trip Generation Analysis - FHWA 1975 - ProcesatDocument184 pagesTrip Generation Analysis - FHWA 1975 - ProcesatBogdanTeodoroiuNo ratings yet

- Travel Cost MethodDocument14 pagesTravel Cost MethodjackNo ratings yet

- Selectively Applicable Techniques of Valuing Environmental ImpactsDocument44 pagesSelectively Applicable Techniques of Valuing Environmental ImpactsNahid MuffeinNo ratings yet

- RDIFFDocument35 pagesRDIFFANDREA CORREA PONCENo ratings yet

- Travel Cost Method (TCM)Document34 pagesTravel Cost Method (TCM)Ayub NurNo ratings yet

- Penilaian Ekonomi Barang Dan Jasa SDAL - Travel Cost MethodDocument27 pagesPenilaian Ekonomi Barang Dan Jasa SDAL - Travel Cost Methodpuput indah sari100% (1)

- Other Revealed Preference MethodsDocument30 pagesOther Revealed Preference Methodsagrawalrohit_228384No ratings yet

- Module 4Document11 pagesModule 4Abhishek BiradarNo ratings yet

- Environmental Economics Chapter Fifteen 2252013Document10 pagesEnvironmental Economics Chapter Fifteen 2252013Mariem Ben SalahNo ratings yet

- Module 4Document11 pagesModule 4monika hcNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Transportation Planning OverviewDocument168 pagesChapter 4 - Transportation Planning OverviewAqsha RaufinNo ratings yet

- TranspoDocument6 pagesTranspoEri EliNo ratings yet

- TransportationDocument129 pagesTransportationFaith Rezza Mahalia F. BETORIONo ratings yet

- Estimation of The Recreation Values of Some Romanian Parks by Travel Cost MethodDocument4 pagesEstimation of The Recreation Values of Some Romanian Parks by Travel Cost MethodDevi Yanti Rahayu SitorusNo ratings yet

- Cee350 TP 6Document10 pagesCee350 TP 6Rafsanul HaqueNo ratings yet

- Architectural Design of Tourist Areas From The Perspective of Ecological Environmental ProtectionDocument6 pagesArchitectural Design of Tourist Areas From The Perspective of Ecological Environmental Protectionitsasj1No ratings yet

- Trip Distribution Synthetic Models: 1. Gravity ModelDocument11 pagesTrip Distribution Synthetic Models: 1. Gravity ModelManjunatha A GoudaNo ratings yet

- Rangkuman Halaman 84-91 CBA AkmanDocument5 pagesRangkuman Halaman 84-91 CBA AkmanHaryo BagaskaraNo ratings yet

- ICDE2019 ContextAwareEmbeddingforTripRecommendationsDocument12 pagesICDE2019 ContextAwareEmbeddingforTripRecommendationsniezhinie2002No ratings yet

- Urban Transportation Planning ProcessDocument44 pagesUrban Transportation Planning ProcessGomadevi DarjiNo ratings yet

- Utp-I ImpDocument8 pagesUtp-I ImpKvsrit AicteNo ratings yet

- Notes 8Document45 pagesNotes 8---No ratings yet

- MODULE 4 UnlockedDocument12 pagesMODULE 4 UnlockedRockstar AnilNo ratings yet

- Ieem23 12 06 2023Document5 pagesIeem23 12 06 2023biswajitkr82No ratings yet

- A Seminar On Tools and Techniques For EconomicDocument32 pagesA Seminar On Tools and Techniques For EconomicKeshav JasoriyaNo ratings yet

- Trip Recommendation With Multiple User Constraints by Integrating Point-of-Interests and Travel PackagesDocument10 pagesTrip Recommendation With Multiple User Constraints by Integrating Point-of-Interests and Travel Packagessarveswaran.mg2020No ratings yet

- Highway 1Document3 pagesHighway 1Cyrille CabungcalNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 11 05880 v2Document21 pagesSustainability 11 05880 v2joanna grandeNo ratings yet

- Modal Split TextDocument5 pagesModal Split Textbestebozkurt1No ratings yet

- Travel Demand ForecastingDocument14 pagesTravel Demand Forecastingpilipinas19No ratings yet

- Ilovepdf MergedDocument146 pagesIlovepdf MergedJoshua A. EboraNo ratings yet

- Module 3Document16 pagesModule 3Aldrin CruzNo ratings yet

- Regression Analysis For Transport Trip Generation EvaluationDocument6 pagesRegression Analysis For Transport Trip Generation EvaluationAJ SaNo ratings yet

- Module 4Document12 pagesModule 4RohithNo ratings yet

- IEEEDocument37 pagesIEEEShruti ReddyNo ratings yet

- Design of Urban Models: TransportationDocument20 pagesDesign of Urban Models: TransportationVincent CruzNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4.1 Trip GenerationDocument18 pagesLesson 4.1 Trip GenerationJoshua A. EboraNo ratings yet

- Last Mile Cost CalculationDocument14 pagesLast Mile Cost CalculationSandeep Bhaskar100% (1)

- Subject: Transport Economics Chapter Title: Travel Demand AnalysisDocument25 pagesSubject: Transport Economics Chapter Title: Travel Demand AnalysisIrfan ShinwariNo ratings yet

- Recreation - HS Chamang 27-9-2008Document16 pagesRecreation - HS Chamang 27-9-2008Awang Noor Abd GhaniNo ratings yet

- Models For Fare Planning in Public Transport: Konrad-Zuse-Zentrum Für Informationstechnik BerlinDocument24 pagesModels For Fare Planning in Public Transport: Konrad-Zuse-Zentrum Für Informationstechnik BerlinCarlos Alfredo Rodriguez LorenzanaNo ratings yet

- Resume Jurnal TransportasiDocument10 pagesResume Jurnal Transportasiyasrun17No ratings yet

- Part IV Chapter 15Document6 pagesPart IV Chapter 15MUNESH YADAVNo ratings yet

- Travel Demand ForecastingDocument51 pagesTravel Demand ForecastingGraciele Sera-RevocalNo ratings yet

- Location and The Demand For TravelDocument18 pagesLocation and The Demand For Travelmkusumawijaya247No ratings yet

- Topic 3.transportion ModellingDocument7 pagesTopic 3.transportion ModellingCivil EngineeringNo ratings yet

- Valuing Nature-Based Recreation Using A Crowdsourced Travel Cost Method A Comparison To Onsite Survey Data and Value TransferDocument9 pagesValuing Nature-Based Recreation Using A Crowdsourced Travel Cost Method A Comparison To Onsite Survey Data and Value Transferafief ma'rufNo ratings yet

- Transpoeng - 7.7 Modal Split AnalysisDocument4 pagesTranspoeng - 7.7 Modal Split AnalysisMarky ZoldyckNo ratings yet

- Regression Analysis For Transport Trip GenerationDocument6 pagesRegression Analysis For Transport Trip GenerationAlsya MangessiNo ratings yet

- Polytechnic University of The Philippines: Lecture # 5Document51 pagesPolytechnic University of The Philippines: Lecture # 5Daisy AstijadaNo ratings yet

- Three Factors That Affect Demand For TravelDocument20 pagesThree Factors That Affect Demand For TravelLeBron James100% (1)

- Forecasting Travel DemandDocument3 pagesForecasting Travel DemandCarl John GemarinoNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3Document21 pagesLecture 3Nicholas KinotiNo ratings yet

- Elasticity of Demand in Urban Traffic Case Study: City of RijekaDocument7 pagesElasticity of Demand in Urban Traffic Case Study: City of RijekaHarini SNo ratings yet

- 2022 Presentation 2Document54 pages2022 Presentation 2lehlabileNo ratings yet

- Transportation Planning System ContextDocument14 pagesTransportation Planning System ContextJUVIN SINGH KOYALNo ratings yet

- UTP Lecture-16 Text Part SourvDocument18 pagesUTP Lecture-16 Text Part SourvShivangi MishraNo ratings yet

- Road Pricing: Theory and EvidenceFrom EverandRoad Pricing: Theory and EvidenceGeorgina SantosNo ratings yet

- Marketing of Tourism Services - Methods, Measurement and Empirical AnalysisFrom EverandMarketing of Tourism Services - Methods, Measurement and Empirical AnalysisNo ratings yet

- Pollution Control KolstadDocument16 pagesPollution Control KolstadshubhamNo ratings yet

- Pollution ControlDocument62 pagesPollution ControlshubhamNo ratings yet

- 8 CL636Document20 pages8 CL636shubhamNo ratings yet

- Market Failure1Document37 pagesMarket Failure1shubhamNo ratings yet

- 5.etch - Part 3 (2) (21613)Document31 pages5.etch - Part 3 (2) (21613)shubhamNo ratings yet

- 10 CL636Document19 pages10 CL636shubhamNo ratings yet

- Valuation MethodsDocument73 pagesValuation MethodsshubhamNo ratings yet

- NRR QuantifiedDocument8 pagesNRR QuantifiedshubhamNo ratings yet

- Environmental Economics Pollution Control: Mrinal Kanti DuttaDocument253 pagesEnvironmental Economics Pollution Control: Mrinal Kanti DuttashubhamNo ratings yet

- Economics of Natural Resources: Resources, and (3) Resource EndowmentDocument31 pagesEconomics of Natural Resources: Resources, and (3) Resource EndowmentshubhamNo ratings yet

- NRR TransitionDocument6 pagesNRR TransitionshubhamNo ratings yet

- HSS MergedDocument140 pagesHSS MergedshubhamNo ratings yet

- MicroFabCH1 5Document168 pagesMicroFabCH1 5shubhamNo ratings yet

- CL 636 - Introduction - 1 (10500)Document11 pagesCL 636 - Introduction - 1 (10500)shubhamNo ratings yet

- 3.lithography - Part 2 (3) (17508)Document33 pages3.lithography - Part 2 (3) (17508)shubhamNo ratings yet

- Imported CSV Data: Exercise 1Document17 pagesImported CSV Data: Exercise 1shubhamNo ratings yet

- 3.CL 636 - Photolithography - Part 1 (4) (14932)Document33 pages3.CL 636 - Photolithography - Part 1 (4) (14932)shubhamNo ratings yet

- Week11 l01 MergedDocument205 pagesWeek11 l01 MergedshubhamNo ratings yet

- Beol - CL 636 (2) (10759)Document37 pagesBeol - CL 636 (2) (10759)shubham100% (1)

- Combined Hs229Document74 pagesCombined Hs229shubhamNo ratings yet

- TCS Big Data Global Trend Study 2013Document106 pagesTCS Big Data Global Trend Study 2013Nila Kumar0% (1)

- Types of Tests 2222Document12 pagesTypes of Tests 2222Akamonwa KalengaNo ratings yet

- FPO BrochureDocument12 pagesFPO BrochureSOURAV ANANDNo ratings yet

- PHD Sophie RoelandtDocument221 pagesPHD Sophie RoelandtSophie RoelandtNo ratings yet

- A Contingency Approach To International Marketing Strategy and Decision-Making Structure Among Exporting FirmsDocument34 pagesA Contingency Approach To International Marketing Strategy and Decision-Making Structure Among Exporting FirmsRicky SanjayaNo ratings yet

- HandwashingDocument4 pagesHandwashingOxfamNo ratings yet

- Maintenance and Inspection of Bridge Stay Cable Systems: Conference PaperDocument13 pagesMaintenance and Inspection of Bridge Stay Cable Systems: Conference PaperikrusmostNo ratings yet

- The Forecasting Accuracy and Effectiveness of Complexity ManagerDocument124 pagesThe Forecasting Accuracy and Effectiveness of Complexity ManagerLindy-Jo SmartNo ratings yet

- CV and Cover Letter CVDocument8 pagesCV and Cover Letter CVSusan Sugiarti100% (1)

- Why Are Teachers Required of Lesson Plan/course Syllabi and Other Forms of Instructional Plan?Document13 pagesWhy Are Teachers Required of Lesson Plan/course Syllabi and Other Forms of Instructional Plan?Eva NolascoNo ratings yet

- Video-to-Video Synthesis: WebsiteDocument14 pagesVideo-to-Video Synthesis: WebsiteCristian CarlosNo ratings yet

- Name: - Date: - Score: - Section: - I. Multiple ChoicesDocument2 pagesName: - Date: - Score: - Section: - I. Multiple ChoicesChristian Lorenz EdulanNo ratings yet

- Surveying ErrorsDocument9 pagesSurveying ErrorsVikash PeerthyNo ratings yet

- Strategic Foresight 01 - Final PDFDocument54 pagesStrategic Foresight 01 - Final PDFAbhimanyu Singh GehlotNo ratings yet

- Swami Vivekanand Subharti University: Term End Examination Schedule June 2019Document4 pagesSwami Vivekanand Subharti University: Term End Examination Schedule June 2019JAIDEEP CHOUDHARYNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Summary Findings and RecommendationsDocument5 pagesChapter 5 Summary Findings and RecommendationsAnya EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- Cassandra Report On Gen ZDocument3 pagesCassandra Report On Gen Zdream_fancierNo ratings yet

- Mlsu PHD Course Work Result 2014Document7 pagesMlsu PHD Course Work Result 2014afjwoamzdxwmct100% (2)

- CV - Anil K Shukla (Nih, Usa)Document6 pagesCV - Anil K Shukla (Nih, Usa)Mehedi HossainNo ratings yet

- Managing Hostage Situations: 1. PlanningDocument3 pagesManaging Hostage Situations: 1. PlanningIvylen Gupid Japos CabudbudNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based Practice in Nursing (EBPN) : IntroduceDocument21 pagesEvidence Based Practice in Nursing (EBPN) : Introduce061Millenia putriNo ratings yet

- Currency Recognition and Fake Note DetectionDocument8 pagesCurrency Recognition and Fake Note Detectionرامي اليمنيNo ratings yet

- Lab Report 1Document3 pagesLab Report 1lihatt20No ratings yet

- A Stochastic Frontier Model With Correction For Sample SelectionDocument10 pagesA Stochastic Frontier Model With Correction For Sample SelectionNikos KadinosNo ratings yet

- Undergraduate Handbook CEE at UIUCDocument68 pagesUndergraduate Handbook CEE at UIUCBilal BatroukhNo ratings yet

- Guideline - Medical Equipment ManagementDocument16 pagesGuideline - Medical Equipment ManagementdvhoangNo ratings yet

- MR ReportDocument19 pagesMR ReportSakshi DixitNo ratings yet

- List of HospitalsDocument7 pagesList of HospitalsMeArshadNo ratings yet