Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Alexander's Generalship at Gaugamela Author(s) : G. T. Griffith Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 67 (1947), Pp. 77-89 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 28/03/2013 14:18

Alexander's Generalship at Gaugamela Author(s) : G. T. Griffith Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 67 (1947), Pp. 77-89 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 28/03/2013 14:18

Uploaded by

Rafael PinalesCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Alexander The Great: Historical Sources in Translation - Waldemar Heckel, J. C. YardleyDocument373 pagesAlexander The Great: Historical Sources in Translation - Waldemar Heckel, J. C. YardleySonjce Marceva91% (22)

- Taking Sides - Alexander The GreatDocument18 pagesTaking Sides - Alexander The GreatMaubarak Boodhun100% (1)

- The Archers of IslamDocument24 pagesThe Archers of IslamZainab Bagodonuts100% (1)

- Alexander The Great and The Macedonian Empire - Professor Kenneth W. HarlDocument212 pagesAlexander The Great and The Macedonian Empire - Professor Kenneth W. HarlSonjce Marceva60% (5)

- MorrisonJames PatternsOfDeathScenesDocument17 pagesMorrisonJames PatternsOfDeathScenesanimumbraNo ratings yet

- The Genre of The Atlantis StoryDocument18 pagesThe Genre of The Atlantis StoryAtlantisPapers100% (1)

- Badian. HarpalusDocument29 pagesBadian. HarpalusCristina BogdanNo ratings yet

- Ashton, The Lamian War-Stat Magni Nominis UmbraDocument7 pagesAshton, The Lamian War-Stat Magni Nominis UmbraJulian GallegoNo ratings yet

- Josephus 3Document1,209 pagesJosephus 3Jose Pablo Nolasco QuinteroNo ratings yet

- The Excavations at Dura-Europos conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters 1928 to 1937. Final Report VII: The Arms and Armour and other Military EquipmentFrom EverandThe Excavations at Dura-Europos conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters 1928 to 1937. Final Report VII: The Arms and Armour and other Military EquipmentNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 2 For Unit Plan - Group 5Document9 pagesLesson Plan 2 For Unit Plan - Group 5api-260695988No ratings yet

- The Johns Hopkins University Press The American Journal of PhilologyDocument11 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University Press The American Journal of PhilologySorina ŞtefănescuNo ratings yet

- Richardson 1943 ΥΠΗΡΕΤΗΣDocument8 pagesRichardson 1943 ΥΠΗΡΕΤΗΣVangelisNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press, The Society For The Promotion of Hellenic Studies The Journal of Hellenic StudiesDocument12 pagesCambridge University Press, The Society For The Promotion of Hellenic Studies The Journal of Hellenic StudiesDanNo ratings yet

- The Weight of Trireme Rams and The Price of Bronze in Fourth-Century AthensDocument10 pagesThe Weight of Trireme Rams and The Price of Bronze in Fourth-Century AthensfwgfssgNo ratings yet

- CASSIUS, Dio. Roman History III, Books 36-40Document536 pagesCASSIUS, Dio. Roman History III, Books 36-40elsribeiroNo ratings yet

- Retro AnalysisDocument24 pagesRetro Analysisflandry2_flNo ratings yet

- Ferguson OrgeonikaDocument36 pagesFerguson OrgeonikaInpwNo ratings yet

- (Hesperia 15) Marcellus T. Mitsos-An Inscription From Mycenae (1946)Document6 pages(Hesperia 15) Marcellus T. Mitsos-An Inscription From Mycenae (1946)ariman5678582No ratings yet

- C. Gill, The Genre of The Atlantis StoryDocument19 pagesC. Gill, The Genre of The Atlantis StoryMariano MeloneNo ratings yet

- The Augment in Homer (Continued)Document18 pagesThe Augment in Homer (Continued)Georgios TsamourasNo ratings yet

- Lorimer-The Hoplite Phalanx With Special Reference To The Poems of Archilochus and TyrtaeusDocument66 pagesLorimer-The Hoplite Phalanx With Special Reference To The Poems of Archilochus and TyrtaeusnicasiusNo ratings yet

- Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees For Harvard University Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Dumbarton Oaks PapersDocument9 pagesDumbarton Oaks, Trustees For Harvard University Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Dumbarton Oaks PaperssophieannebreizhNo ratings yet

- R G Austin Roman Board Games IDocument12 pagesR G Austin Roman Board Games IrhgnicanorNo ratings yet

- Riess 1896Document6 pagesRiess 1896mishaiolandaNo ratings yet

- The Johns Hopkins University Press The American Journal of PhilologyDocument9 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University Press The American Journal of Philologymichael_baroqNo ratings yet

- Chase 1902 - The Shield Devices of The GreeksDocument68 pagesChase 1902 - The Shield Devices of The GreeksVLADIMIRONo ratings yet

- Rapid Article: Iiiiihiiiiiii Iiiiw 111111Document23 pagesRapid Article: Iiiiihiiiiiii Iiiiw 111111EmmanuelNo ratings yet

- Pisistratus and HomerDocument20 pagesPisistratus and HomerAlvah GoldbookNo ratings yet

- TM 30-546 1956 Obsolete) Glossary of Soviet Military and Related AbbreviationsDocument184 pagesTM 30-546 1956 Obsolete) Glossary of Soviet Military and Related AbbreviationsBob Andrepont100% (2)

- Ring-Composition in Catullus 64Document11 pagesRing-Composition in Catullus 64Sergio Embleton MárquezNo ratings yet

- WWUE Roth Opening of The Mouth Ritual 2Document24 pagesWWUE Roth Opening of The Mouth Ritual 2Timothy SmithNo ratings yet

- Hickey-Ast P.Messeri17 ShorthandCommDocument3 pagesHickey-Ast P.Messeri17 ShorthandCommRodney AstNo ratings yet

- Astronomicon Vol. 2Document164 pagesAstronomicon Vol. 2Garga100% (1)

- Tabula GameDocument5 pagesTabula GameMAVillarNo ratings yet

- Brooke-The OT in Greek (II, 2) - 1930 PDFDocument208 pagesBrooke-The OT in Greek (II, 2) - 1930 PDFphilologusNo ratings yet

- Franz Steiner VerlagDocument3 pagesFranz Steiner VerlagvescapuntesNo ratings yet

- Greek Coins Acquired by The British Museum in 1929 / (G.F. Hill)Document23 pagesGreek Coins Acquired by The British Museum in 1929 / (G.F. Hill)Digital Library Numis (DLN)100% (1)

- Bain AudienceAddressGreek 1975Document14 pagesBain AudienceAddressGreek 197544KarateNo ratings yet

- Borthwick - 2001 - Socrates, Socratics, and The Word +Æ+ +ò+á+ò+ö+æ+ö+ + +Document5 pagesBorthwick - 2001 - Socrates, Socratics, and The Word +Æ+ +ò+á+ò+ö+æ+ö+ + +alba.sanchez.varelaNo ratings yet

- The American School of Classical Studies at Athens Hesperia: The Journal of The American School of Classical Studies at AthensDocument22 pagesThe American School of Classical Studies at Athens Hesperia: The Journal of The American School of Classical Studies at AthensJornadaMentalidadesNo ratings yet

- EDGERTON - Ancient Egyptian Ships and Shipping PDFDocument28 pagesEDGERTON - Ancient Egyptian Ships and Shipping PDFSebastián Francisco MaydanaNo ratings yet

- Epic and Empire. D. QuintDocument33 pagesEpic and Empire. D. QuintSandraNo ratings yet

- Smither Old Kingdom Letter SabniDocument5 pagesSmither Old Kingdom Letter SabniInpwNo ratings yet

- Strabo On Acrocorinth - The American School of Classical Studies at ...Document6 pagesStrabo On Acrocorinth - The American School of Classical Studies at ...Javier Martinez EspuñaNo ratings yet

- Oared Warships (Oxford 1996), 317Document12 pagesOared Warships (Oxford 1996), 317mfalc128457372No ratings yet

- Archmedial Dimension of A Circle by KnorrDocument45 pagesArchmedial Dimension of A Circle by Knorrarun rajaramNo ratings yet

- Kanawati - Report 8 Part 1 TextDocument74 pagesKanawati - Report 8 Part 1 Textmenjeperre100% (1)

- Two Textual Problems in Euripides' Antiope, Fr. 188 - E. K. Borthwick (The Classical Quarterly, 1967)Document8 pagesTwo Textual Problems in Euripides' Antiope, Fr. 188 - E. K. Borthwick (The Classical Quarterly, 1967)Đoàn DuyNo ratings yet

- The Cynic and The StatueDocument6 pagesThe Cynic and The StatueGEORGE FELIPE BERNARDES BARBOSA BORGESNo ratings yet

- The Earliest Triobols of Megapolis / Jennifer WarrenDocument15 pagesThe Earliest Triobols of Megapolis / Jennifer WarrenDigital Library Numis (DLN)No ratings yet

- B 23983139Document122 pagesB 23983139Branko NikolicNo ratings yet

- The Hoplite Reform and History - SnodgrassDocument14 pagesThe Hoplite Reform and History - SnodgrassFelipe NicastroNo ratings yet

- The Johns Hopkins University Press Transactions and Proceedings of The American Philological AssociationDocument35 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University Press Transactions and Proceedings of The American Philological AssociationSorina ŞtefănescuNo ratings yet

- Marathon Epigrams PDFDocument6 pagesMarathon Epigrams PDFmortiz4716No ratings yet

- Remarks On The Pahlavi Ligatures X 1 and X 2Document15 pagesRemarks On The Pahlavi Ligatures X 1 and X 2loki1983No ratings yet

- Three Centuries of Late Roman PotteryDocument29 pagesThree Centuries of Late Roman PotteryBiljanaLučićNo ratings yet

- Franz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteDocument26 pagesFranz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- 44002541Document7 pages44002541Shreyans MishraNo ratings yet

- Dio Cassius - Roman History II - (Loeb) PDFDocument534 pagesDio Cassius - Roman History II - (Loeb) PDFLuca CremoniniNo ratings yet

- Franz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteDocument13 pagesFranz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Franz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteDocument26 pagesFranz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Notices of Books: of The Macedonian Army. Berkeley Etc.: UniverDocument2 pagesNotices of Books: of The Macedonian Army. Berkeley Etc.: UniverRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Seleukos Self-Appointed General Stratego PDFDocument85 pagesSeleukos Self-Appointed General Stratego PDFRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- GAUGAMELA 331 BC The Triumph of TacticsDocument27 pagesGAUGAMELA 331 BC The Triumph of TacticsRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Kleanthis Zouboulakis Carrying The GloryDocument32 pagesKleanthis Zouboulakis Carrying The GloryRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Aurelian and Probus. The Soldier Emperor PDFDocument1 pageAurelian and Probus. The Soldier Emperor PDFRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Doomed Men of Distinction: The Battle of Gaza, 312 BCDocument8 pagesDoomed Men of Distinction: The Battle of Gaza, 312 BCRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Las Mujeres Mongolas en Los Siglos XII yDocument27 pagesLas Mujeres Mongolas en Los Siglos XII yRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Daily Life in The Hellenistic AgeDocument253 pagesDaily Life in The Hellenistic Agemarnat13100% (5)

- Alexander The Great Conquest Map, Collins Military HistoryDocument1 pageAlexander The Great Conquest Map, Collins Military HistoryOm SANTOSNo ratings yet

- History of MacedoniaDocument50 pagesHistory of MacedoniaPavle Siljanoski Macedonia-timeless100% (2)

- Pagan PakistanDocument71 pagesPagan PakistanmasterminddNo ratings yet

- RC History AlexanderDocument5 pagesRC History Alexanderanon-753112No ratings yet

- Alexander The GreatDocument41 pagesAlexander The GreatGirish NarayananNo ratings yet

- Theteachinganddevelopmentof GreatnessDocument20 pagesTheteachinganddevelopmentof Greatnesskhghrvb6r9No ratings yet

- Alexander The GreatDocument2 pagesAlexander The GreatErik SimkoNo ratings yet

- (Essential Histories) Waldemar Heckel - The Wars of Alexander The Great-Osprey PDFDocument97 pages(Essential Histories) Waldemar Heckel - The Wars of Alexander The Great-Osprey PDFJorel Fex100% (3)

- Granicus 334 BC - Alexander's Fi - Michael ThompsonDocument97 pagesGranicus 334 BC - Alexander's Fi - Michael ThompsonNick Stathis67% (3)

- The Battle of IssusDocument2 pagesThe Battle of IssusvademecumdevallyNo ratings yet

- Alexander The Great-Beddall FionaDocument67 pagesAlexander The Great-Beddall FionaJordan Cabaguing50% (2)

- The Conquests of ALEXANDER (336-323 B.C.E.) : TOHL-eh-meeDocument15 pagesThe Conquests of ALEXANDER (336-323 B.C.E.) : TOHL-eh-meeOlivier UwamahoroNo ratings yet

- Commanders History S Greatest Military Leaders DK Publishing 2011 PDFDocument362 pagesCommanders History S Greatest Military Leaders DK Publishing 2011 PDFMatheus Benedito100% (1)

- On Greek Matters - Macedonia Name Dispute (By Galanos Ilios)Document131 pagesOn Greek Matters - Macedonia Name Dispute (By Galanos Ilios)Macedonia - The Authentic TruthNo ratings yet

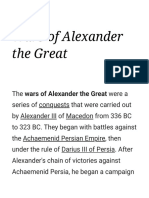

- Wars of Alexander The Great - Wikipedi1Document106 pagesWars of Alexander The Great - Wikipedi1NicholasNo ratings yet

- The Battle of Issus-Albrecht AltdorferDocument10 pagesThe Battle of Issus-Albrecht AltdorfermuleitaliaNo ratings yet

- Alexandar The GreatDocument2 pagesAlexandar The GreatMaja MakicaNo ratings yet

- Alexander The Great TimelineDocument5 pagesAlexander The Great Timelinepelister makedonNo ratings yet

- Alexander's Last Days: Articles On Ancient HistoryDocument9 pagesAlexander's Last Days: Articles On Ancient HistoryJose De Arimateia Y JesusNo ratings yet

- Alex Act 2 Sc1 Site 2Document5 pagesAlex Act 2 Sc1 Site 2El-Sayed MohammedNo ratings yet

- Rzepka ConspiratorsDocument13 pagesRzepka Conspiratorsapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Alexander The GreatDocument3 pagesAlexander The GreatmanjuNo ratings yet

- 10 - Greek Civilization Lessons 1-4 Reading EssentialsDocument16 pages10 - Greek Civilization Lessons 1-4 Reading Essentialsapi-332589860100% (1)

- Alexander The Great by Thomas R. MartinDocument51 pagesAlexander The Great by Thomas R. MartinAwais AhmedNo ratings yet

- Classical Greece Activity PDFDocument12 pagesClassical Greece Activity PDFBrandon AndreasNo ratings yet

Alexander's Generalship at Gaugamela Author(s) : G. T. Griffith Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 67 (1947), Pp. 77-89 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 28/03/2013 14:18

Alexander's Generalship at Gaugamela Author(s) : G. T. Griffith Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 67 (1947), Pp. 77-89 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 28/03/2013 14:18

Uploaded by

Rafael PinalesOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Alexander's Generalship at Gaugamela Author(s) : G. T. Griffith Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 67 (1947), Pp. 77-89 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 28/03/2013 14:18

Alexander's Generalship at Gaugamela Author(s) : G. T. Griffith Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 67 (1947), Pp. 77-89 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 28/03/2013 14:18

Uploaded by

Rafael PinalesCopyright:

Available Formats

Alexander's Generalship at Gaugamela

Author(s): G. T. Griffith

Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 67 (1947), pp. 77-89

Published by: The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/626783 .

Accessed: 28/03/2013 14:18

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The Journal of Hellenic Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 137.149.3.15 on Thu, 28 Mar 2013 14:18:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALEXANDER'S GENERALSHIP AT GAUGAMELA

IT is agreed that of the extant accounts of the battle of Gaugamela, that of Arrian is by

far the best, the only one, in fact, that permits of a coherent reconstructionof what took place.

The best modern accounts derive mainly from Arrian, and it may perhaps be felt that modern

criticism has resolved satisfactorily the two or three important obscurities in his story, and

that everything is now plain.1 With this opinion I cannot agree. To me Arrian's story is

not obscure, but, equally, it is not complete; and what he omits is of such importance that

without it I cannot see clearly why Alexander, and not the Persians, won this battle. I am

not suggesting that really the Persians did win it; but my aim is to supply that part of the

picture which (in my view) Arrian has left blank, and without which the manner of Alexander's

victory is still not fully explained.

With Arrian's description of the order of battle adopted by the two commanders there is

now no serious quarrel. It is best shown by means of a plan, which in respect of the flank-

guards of Alexander represents a compromise between the two interpretations previously

regarded as possible. The one interpretation 2 makes the flank-guards (5 ,ET'Kap-rrTiV,

Arrian III 12. 2 and 4) take up positions which merely extend the Macedonian front on each

wing; this does violence alike to the Greek 3 and to the natural conception of what a flank-

guard is intended to do, and moreover it disregards Arrian's careful distinction between (a)

Alexander's 'front' and (b) his second line (rear-guard) and his flank-guards, Arrian's

passing from (a) to (b) being clearly marked by the words p~v-Irr T&t 'AAE?v&pcp

TPETrcSTrovou

8CE TTJDT0rc E i -- -- (ibid.I). The other T1

interpretation

4 makes of the flank-

KEK6"TEIO'

the two sides of a ' ' the more

guards opposite square (in military sense), or, exactly, the two short

sides of a rectangle of which the two long sides are on the one hand Alexander's ' front ' and on

the other hand his second line (rear-guard): this meets the military requirements perfectly,

though the idea of a defensive 'square' or rectangle was impossible to execute completely

because the infantry of the second line were too few to fill up the second long side of the

rectangle. Alexander's instructions to Menidas on the right were: Ei TerrEptiflTrE1OIEV ol

-TrOhIPlo T7 Ki4pcs (cyp)V, 5

TrAcxyioUS To1KYCpyaVTCXs,5 where

E'pXAAElVCIToS

i-rmK~yxav-rTas

(I take it), does not agree with aC0IroIs(the enemy) but with the subject of ?p~AdxEv (Menidas

and his men): I should translate ELfpp3dxELv m'rKcapycv-r'charge at an angle'. My

reason for preferring a slanting (rather than a rectangular) -rrmK&rmrlov is that it gives to

Menidas a better chance of an early interceptionof the enemy Ei TEpU1TrTrVEio0Ev, without

surrendering entirely his chance of wheeling round to the rear if the enemy got right round

behind the army.

1 All references to Arrian in this

paper are to the to Professor D. S. Robertson for kindly giving me his

Anabasis. The best modern work on this battle is by opinion on a point of Greek translation.

W. W. Tarn, CambridgeAncientHistory VI 379 ff., and 595 2

CJ:Judeich loc. cit.

(Bibliography), and now in Alexander the Great, Part I 3 There can be no serious doubt that the words ftKrFmart,

Narrative,and Part II Sourcesand Studies (Cambridge, I947), rlmK&riov, iK&W-rTi)c in this military connexion denote

references to which will be shown by the abbreviations a bend or angle in a line of battle, whether a bend forward

Tarn AGN and Tarn AGSS. Indispensable also are J. in the case of the outflankers, or a bend backward in the

Kromayer, Antike SchlachtfelderIV 377 if.; W. Judeich, case of the outflanked (as here): cf. Arrian II 9. 2 and

in Schlachtenatlaszur antiken Kriegsgeschichte,griechische Ii. I (Issus); Xen. Hell. IV 2. 20 (Corinth); Cyr. VII

Abteilung, Blatt 7 (ed. J. Kromayer and G. Veith, Leipzig I. 6 (Croesus and Cyrus); Anab. I 8. 23 (Cunaxa);

1922); K. J. Beloch, GriechischeGeschichteIII2 I. 642 ff., Diodorus XVII 57. 5 (Gaugamela); Polybius V 82. 9

IV2 2. 290 ff. These versions contain some important (Raphia); VI 31. 2 (lay-out of a Roman camp). The

differences of opinion. defensive was called by the later tacticians

I am greatly indebted to Dr. Tarn for allowing me to 0irrordts,a 'rr•K•W-rrov

definition of which seems to illustrate Alexander's

see his most recent work (AGN and AGSS) while it was dispositions here; Aelian, Tactica XXXI 4- 8

still in proof, and for reading this paper in MS.: his detailed oTrilv, itv T1r TOr6T KipawtTa

o•rordo?s

Tr1KmapTriOUv

comments and criticism led me to make a nimber of TroS• •ulhovs 6Aov

-rT&tv gXovTras CtOr p rpTrvrhoEI8S

Xia~ j-TrOTO'O

iva. The

additions, omissions and alterations. My thanks are also meaning of rTrr6 is 'behind': for (a three-piece

due to Professor F. E. Adcock, who read my MS. and gate), see Liddell and Scott,9 s.v. rpi'rrvAov

helped me greatly by his suggestions, particularly in the 4 Tarn, AGSS p. 184.

interpretation of several difficult passages of Arrian: and 5 Arrian III 12. 4.

77

This content downloaded from 137.149.3.15 on Thu, 28 Mar 2013 14:18:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

78 G. T. GRIFFITH

VIII

V/////////A

MAZAEUS DARIUS BESSUS

1.7zz7

TTzzzz

VII VI

1Tz777zzz 7 7zzz zz

X

IX

IV IV

Mza

077-/772

I

zza9 7 IV

z7

III II

XI V

ORIGINAL

' PERSIAN 'TOF

ORDER . 1.3.

BATLE(ARRIAN

PERSIAN POSITION AT ARRIAN III. 13. I.

W

A./. 14.1 -3

1i1A13.2

r

9 8 =7 6 5 4 3

0987654 2

6 4 i

I 2- X

D 4Z9N~ REFERENCE

22 The approach of the armies

The final movements which

ALEXANDER'S ORDER OF BATTLE takeents intactiono

ORIGINAL

ARRIAN I Menidas, the

-Alexander andthefirstfour

hypaspists,

Taxeis of the phalanx

XXXX The action described in

E the camp ,Ar , 13.3-4of the chariots

the carge

anrian-

Suggested area for the meeting

of Alexanderand Menidas

? Suggested area for the action

have beThe ind.

action

describeddescribed

in Arrianl,15.1-2

23

FIG. I.-PLAN OF BATTLE OF GAUGAMELA.

This content downloaded from 137.149.3.15 on Thu, 28 Mar 2013 14:18:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALEXANDER'S GENERALSHIP AT GAUGAMELA 79

Key to the Plan (basedon ArrianIII. ii and 12).1

Macedonians. Persians.

A i.* 'Companion' cavalry (Philotas: led in the battle I. Bactrian, Dahae, and Arachosian cavalry: Persians

by.Alexander himself). cavalry and infantry mixed: Susians: Cadusians.

2. Hypaspists (Nicanor). II. Scythian (Saca) cavalry.

3-* Phalanx ist Taxis (Koinos). III. iooo Bactrian cavalry.

4. ,, 2nd Taxis (Perdiccas). IV. 200 chariots.

5. ,, 3rd Taxis (Meleager). V. Elephants.

6. ,, 4th Taxis (Polyperchon). VI. Personal Troops of Darius.

7- ,, 5th Taxis (Simmias). VII. Greek mercenary infantry.

8. ,, 6th Taxis (Craterus). VIII. Second-line Troops: Uxii, Babylonians, Red Sea

9. Allied cavalry (Erigyius). peoples, Sitacenians.

Io. Thessalian cavalry (Philip). IX. Syrians, Mesopotamians, Medes, Parthians and

I1. Agrianians, Archers, and Javelin-men (Balacrus). Sacae, Tapurians and Hyrcanians, Albanians

B 12.* Mercenary cavalry (Menidas). and Sacasinians.

13. Paeonian cavalry (Ariston). X. Cappadocian cavalry.

14.* ' Prodromoi' cavalry (Aretes). XI. Armenian cavalry.

I5. Mercenary infantry (Cleander).

I6. Macedonian archers (Brison).

I7. Agrianians (Attalus).2

C I8. Thracians (Sitalces).

19. Allied cavalry (Koiranos).

20. Odrysian cavalry (Agathon).

21. Mercenary cavalry (Andromachus). * These 4 units are specially mentioned in

my text,

D 22. Greek infantry. and their movements are of special importance for my

E 23. Thracian infantry, guarding the Camp. argument.

FOOTNOTES TO PLAN I.

1 A small but awkward difficulty is a doubt which must turned, and become a line-of-battle, ol rpo-re-raygivoi

present itself as to the meaning to be attached to the pre- have become the people on one wing. As for the mere

positions Trp6 and trri when they are prefixed to -r~~aac. paradox of meaning 'on the flank', it can easily be

r9p6

paralleled, or even surpassed, in contemporary military

1TTCr&aacaclearly can mean either 'post behind' or 'post

next to ' (cf. Liddell and Scott 9 s.v. for the two groups of language. What recruit has not heard the command

examples), and only the context can indicate which meaning 'Company will advance-about turn'? It sounds like

is to be preferred in each case. But I am inclined to think nonsense, but it makes good sense when you know what

that we must look for a similar ambiguity when we meet has gone before; and this is true also of my proposed

7rpord&aaao too, though I do not know that anyone previously paradoxical meaning for

has felt this doubt (Liddell and Scott' s.v. gives only the It will be objected thatrp96.

here at Gaugamela Alexander

obvious meaning). The fact is that whereas (for example) had units 7rpo-re-rayctbvoi on both wings. But the objection

the Persian scythe-chariots must certainly have been disappears when it is realised that in the preceding

'posted in front' (-rposETET&XCao, Arrian III I1. 7), the paragraph it is only for the sake of simplicity that I have

word is used also of certain cavalry units of Alexander, spoken of one column as forming the line-of-battle. Anyone

and seems to me to give better sense if translated 'posted familiar with the movements of troops will realise that an

on the extremeflank ' (Arrian id. I1. 8, I2. 3 and 5): this is army of even 20,000 men in one column would take hours

particularly so of its application to Alexander's K~

PaactXKi r to get anywhere or form anything. In practice an army

in relation to the remaining mass of the 'Companion' deploying for battle would often deploy in a number of

cavalry at a moment when they are quite clearly in line, columns, to each of which individually my remarks above

not in column ( I1.8-9). The plan shows in which cases will apply. At Issus, Alexander brought his whole army

I have thought that npp6= ' on the flank ' gives the better into the plain of Issus in one column, but only because

sense, and a careful reading of the cited passages in Arrian the narrow pass through which he had to march gave him

will (I hope) indicate why. no choice: as soon as the plain broadened out enough to

Although it is not easy in individual cases to interpret give him room, the several contingents 'peeled off' from

-this ambiguity (if I am right in thinking it exists), it is also the single column under his direction and went the shortest

not difficult to see its origin, if we remember that a line- way to their battle stations (Arrian II 8. I ff.). Neverthe-

of-battle is really only a column-of-route in which each less a clear reminiscence of occasions when the whole

man has obeyed an order 'Right (or left) turn'. This phalanx moved in one column can be seen in the later

must, in fact, have been the commonest (because the practice of calling the right wing the ' head' and the left

simplest) way of getting into line-of-battle, by moving wing the 'tail' of the phalanx (Arrian Tactica VII. 2),

in column on to the required position, halting, right (or where 'head' and 'tail' becoming 'right' and 'left'

left) turning, and then making any necessary adjustments correspond exactly to these alternative meanings of rrp6

(such as 'dressing' spacing, and deepening the phalanx and twi.

if desired). In a force moving in column, ot rTpoTETayvpvot 2 For the

probable strengths of these units of the right

are the people in front; but when the column has halted, flank-guard, see p. 83, n. 20 below.

This content downloaded from 137.149.3.15 on Thu, 28 Mar 2013 14:18:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

80 G. T. GRIFFITH

Alexander's is a defensive formation, dictated by his inferior numbers and by the nature

of the ground, which (unlike the field of Issus) allowed Darius to use to the full his most

effective arm, a good and numerous cavalry, to say nothing of elephants and the scythe-

chariots resuscitated for the occasion (to no purpose, as it proved).6 Here, Alexander has

no sea to guard his left flank, no hills to insure his right against encirclement by enemy

cavalry: 7 he must make his own flank-guards for himself, and must begin by fighting a

defensive battle, at least till a safe moment should present itself for his own attack. Groups

B and C in the Plan are his flank-guards (Es TrlKcaprTlv)and Group D is a rear-guard, a

second line of infantry with orders to face about and repel an attack from the rear if the army

should be enveloped.8 So far Arrian is explicit and clear. Finally, it is important to notice

that the Persian line must have been about twice as long as Alexander's, since Darius in the

centre was opposite to Alexander on the Macedonian right wing: this implies a big Persian

overlap on the Macedonian right.9

It is in his account of the fighting itself that questions arise. It may be divided (though

he himself does not so divide it) into three phases:

PHASE I. The defensivebattle.

An attempt by the Persians to outflank and envelop where it was clearly easiest to do so,

on Alexander's right; easiest because it was here that the Persians started with a great overlap,

and though Alexander had moved to correct it, they too had moved to prevent him from

doing so. His answer was to move forward and engage two of the three cavalry units and

one of the three infantry units which formed his flank-guard (Group B). The danger was

averted for the moment, but only for the moment.10

I must point out here a fairly important difference between my interpretation and that

of Dr. Tarn. It is a question of the meaning of a single sentence of Arrian, summing up this

preliminary action on the flank before he goes on to describe the charge of the Persian chariots;

III 13. 4-dAA'a Kaci O5 Td TE rpoarpoA& cairv ~8Xov ro o0 McaxE66vEKac f3i KcrT'

'K i'A•5

•c60eouv

'pooTrr ovTresi5 T'5 d•EC•S.

First, who are the MaKE56VEs? The only true MaKE06VES who could be concerned in

this action are Alexander's 'Companions' themselves (see now Tarn, AGSS, pp. 157 ff., for

the Prodromoiof Aretes), and Dr. Tarn supposes that it is indeed the ' Companions ' who are

concerned here; that in fact the attack on the flank has penetrated through the flank-guard

and into their ranks, from which they succeed in repelling the enemy (~dce0ouv EK

-r~dEGco).11 But is this what is meant by ?cbeouv yEK Trfi T& EcoS? My own translationT"i5 of

this phrase would be ' they pushed them (sc. the enemy) out of their (sc. the enemy's) line '-

6 On the site of the

battle, see now Sir Aurel Stein, cavalry, which he could get. For these reasons I would

GeographicalJournal 1942, P. 155. The battlefield had suggest that an estimate of 25,ooo cavalry with Darius

been in part artificially levelled (Arrian III 8. 7). For here may not be too high. Beloch's estimate (op. cit. III2

the numbers of the Persian cavalry, see W. W. Tarn, I, 643, note I) was 12-15,000. Curtius (IV 12. 13)

HellenisticMilitary and Naval Developments,pp. 153 ff., where gives 45,000 (with 200,000 infantry); Arrian (III 8. 6)

a maximum figure for the Empire of 50,000 is proposed: gives 40,000 (with 1,000,000 infantry). Dr. Tarn is clearly

this is a paper strength, and not the number for this or right in his view that no Greek writer's total for a Persian

any other particular battle, and Dr. Tarn points out that army has any chance of being right, since the official

it may be an over-estimate. For his most recent views version is just as liable to exaggeration (for obvious reasons)

on the numbers of the cavalry at Gaugamela, see now as the vulgate.

AGSS p. 188, where he gives reasons for believing that the 7 The hills at Issus had provided this insurance, though

Persian cavalry units here were comparatively small. they did not relieve Alexander altogether of the necessity

This is evidently true of certain picked units, e.g., the picked of guarding his right flank, since they were already

Bactrians and the Royal Guard (each Iooo), and probably occupied by a Persian force (Arrian II 8. 1 I; 9.

also the Indians who operated with the Royal Guard, the 8 Arrian III 12. I. 2-3).

Sacae who operated with the picked Bactrians, and the 9 Id. 13. I, with Ii. 5. Diod., XVII 58. I, says that in

Armenians and Cappadocians who did a similar job on the order of battle Darius was opposite to Alexander. He

the other flank. This does not account, however, for by later (59. 2) says that Darius commanded the Persian left,

any means all the cavalry, as a glance at the list will show: which must be a mistake in view of the Persian tradition

and Arrian's implication (III 13. I) that Darius' line of of the King in the centre. For a suggested explanation

battle was about twice as long as Alexander's does not of the mistake, see note 16 below.

suggest small numbers in general. Since Darius had no 10 Arrian III 13- 2-4.

means now of getting good infantry, his best policy would 11 Tarn, AGSS pp. 185 f.

seem to have been to make himself as strong as possible in

This content downloaded from 137.149.3.15 on Thu, 28 Mar 2013 14:18:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALEXANDER'S GENERALSHIP AT GAUGAMELA 81

i.e., they threw them into disorder. It appears to me that, for this phrase considered by

itself, either translation is possible. But the offensive idea conveyed by the participle

just previously makes me prefer the second translation to the first, and it

TrpoOnThTtrovTrE

be added that the verb E'coediv can certainly apply to an ofensive' pushing ', as is clear

may

from Arrian's use a little later of the noun cbeipooiSto describe the breaking of the Persian

line by the charge of the ' Companion' cavalry, and from a passage describing the crossing

of the Granicus where Eico0eEIis used of the offensive efforts of the Macedonians, as opposed

to for the defensive efforts of the Persians."

drccc•xaeat

But if this interpretation be accepted, I am then bound to explain ol MaKES6VES, whom

Dr. Tarn, using the other interpretation, takes to be the ' Companion' cavalry, engaged here

in restoring the battle of the flank by repelling the enemy from their own ranks which have

been penetrated. My translationmakes the flank-guardtroops alone responsiblefor' throwing

the enemy into disorder ': who, then, are oi Ma[KE56VE? Dr. Tarn has shown convincingly

that no other truly Macedonian unit was in the neighbourhood (loc. cit.). I conclude, there-

fore, that Arrian here uses oi MCKE56VES not ethnically but generally-' Alexander's troops':

and though elsewhere in this detailed description of the fighting Arrian appears to label the

units, both Alexander's and those of Darius, by their true ethnic names, three instances can

be cited later in this same battle where MaKE56VES refers quite obviously not to Macedonian

units but merely to ' Alexander's troops '.13

To sum up, either interpretation here raises a difficulty. On Dr. Tarn's interpretation,

the difficulty is that the ' Companions' are here described in action without any description

of how they got into action; we must assume, that is, that Arrian has ' telescoped ' his sources,

a thing that could happen, though it was less likely to happen (it seems to me) to the ' Com-

panions ' led by Alexander himself than to any other unit of the army. On my interpretation,

if the translation itself be accepted as the more likely of the two, the difficulty is that of explain-

ing oi M cmaK6vES,a difficulty which in my view is the less serious of the two. The reason

why I have thought it important to spend time on these linguistic minutiaeis because it is

important to follow as closely and exactly as possible the course of this battle on the right,

in view of what is to follow.

What follows immediately is the charge of the Persian scythe-chariots, an interlude which

might have been dangerous if Alexander had not foreseen it and taken the proper steps to

counter it. It was a failure, and it need not detain us now.14

Meanwhile the engaged units of the flank-guard were again being hard pressed, and

Alexander still refrained from reinforcing them further.15 A greater attack was developing,

and it was the beginning of another Persian attempt at encirclement, starting this time from

much nearer to the Persiancentre, that opened a momentary gap in their own ranksand invited

Alexander himself to charge cc rt' cXMJrbV av pEaov. A casual reading of Arrian's description

gives the impression, perhaps, that this second encircling move is a repetition of the first, in

the sense that it concerns the same Persian troops making a renewed effort. But a more

careful reading makes it certain that the second attempt is genuinely a new move involving,

this time, many more Persian units than before, and in fact developing on so grand a scale

that Darius himself in thecentrewas taking part in it when he received the charge of Alexander.

Arrian III 14. I-2--cbS 5 ACpsios rnTyEvfijSr Tiv pdi&cyya -rracrav, ivTcraUcx 'AM•avGpo&

'ApAl-rlv lV KE?•EXiEt T01i

IgfcXEW ToEP1iTrTrEri

OUU1 TO CA

COrE&

K~pc(• Cr)V Tr &iaOV KKACOO'IV"

12 Arrian III 14. 3. T"E TrTEisof &ll(p 'AMh(avpov

Kali use of t?gcoaavfor the ' pushing ' of an attacking force.

o" 13

acrr6s 'ANegav8poS vipcba-r•o S E KE1VTO CelOtoiSs -r Xp6OPvoi Ka III 14. 4-?~ 6 EAVpov l -?v MaKEB6voC = ' the left

rols (vaTrois -r irrp6acrwrra -rCv K6rrrov-rs .... wing of Alexander's army '.

The Granicus passage is Arrian TTIpcaav

I 15. 4--w1VEX61Evoty&p III 15. 5. ra = ' the baggage

OKE•\O6po Tr;V MCaKE86VOV

trrrrot

-re1TrrrroiKoXI &VIpow iycWVi3ov-ro,oli IV ~Seaat of Alexander's army '.

&vpPES

es d&narvd&r6ri- 6X0Ts Kai i sr6rr64toV Of III 14. 5 sub finem refers actually to

TOr1 flpOtCas, TotS MCKE•86cV

ol MaKEB6vES, iSpt acirE

o! b iac•&6eaio

rE v -rviv gKjCaiV, oi Flkpaai, Kca a Thracian unit (cf. III 12. 5). I am indebted to Dr. Tarn

is ro6vrworavcp6v

a6tS d&rrdctobeai.drrcduaaeaiis here the word himself for pointing out these instances to me in a letter:

used for the defensive'pushing', the repelling of an enemy I had not noticed them previously.

out of one's own line. See Thuc. V 72. 3 for a confirmatory 14 Arrian III 13 5-6.

15 Id. 4.

VOL. LXVII. G

This content downloaded from 137.149.3.15 on Thu, 28 Mar 2013 14:18:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

82 G. T. GRIFFITH

pe

ci-rnS 6i TE-LO ETTiKEPCOSTO•s a"TOV TCoV 8 V ThOis

ea(•i' ri~yE'" EK30ine1•t•VVTe iTITECOV

TO TO' 8EioV T1 TiS

-rcov 3cappapcov,

KUKOUlPEVO15 K•P•S rrCapaCpprnvTCOv rrpc•m'&rS

&Xc2yyogS

TT iEXOV

ETTr1UTPa& TE T

KQr EvPOVEX o-rrEp loorroi-orja T7"S 1TTrro

C"UaTEo KCiT"IS

"rjS ETa•C•pKM

-

pc&cXyyo -Trf rcr"IrI TETarOYPEv)s,lyE Kai &?xaiyVi cWSE v The

8•p6pp 0Tr' arr"v AapEiOV.

words underlined are those which indicate that this 'battle of the flank' has now extended in

scope and scale to include the two kings themselves.16

I interpret this passage as meaning that Darius was now carrying the execution of his plan

to its second stage: now that a good part of Alexander's right flank-guard was already in action

(as indicated above), the time had come to engage heavily and from the flank the remainder

of the flank-guard, then the Macedonian cavalry and phalanx itself. The whole thing followed

logically upon what had been done hitherto: the initiative was still with the Persians, and still

followed the same aim, and it was to thwart this aim that Alexander threw the ' Companion'

cavalry, then the phalanx, into the battle at a point where momentarily a gap had been created

by Aretes.

PHASE 2. The general offensive.

Its spearhead was the charge of Alexander at the head of the 'Companion' cavalry,

which broke the Persian line and put Darius to flight. The Macedonian infantry of the phalanx

advanced too, but more rapidly on the right than elsewhere, because the right was nearest to

the break in the Persian line, and because of the right-hand bias (from the Macedonian point

of view) of the whole trend of the battle hitherto. The left of the phalanx was actually held

up, so that in its left-centre a gap presently appeared, through which some Indian and Persian

cavalry charged, and went on to rifle the camp. (Of this charge, more later.) 17 Finally,

the extreme left of Group A, and the left flank-guard Group C, were never able to make pro-

gress, being themselves from the first in danger from an outflanking movement by the cavalry

of Mazaeus.s1

PHASE 3. From local successto general victory.

Alexander achieved this development by switching his victorious 'Companions' over

(behind the Persian centre) to relieve his embarrassed left wing: this at least was his intention,

though in the event his left fought itself free from its difficulties before he had time to relieve

it, and Alexander with the cavalry of the right thereupon turned to pursue the beaten army.

But according to Arrian this movement of the 'Companions' to relieve the left had been

occasioned by an appeal for help from Parmenion, reaching Alexander when he had already

begun 'a pursuit' (Too pEv 5lCOKEIV ET d&rETp'rrrETO): this first 'pursuit ' he broke off in

answer to the message, and he renewed the pursuit only when he learned that Parmenion

no longer needed his help.19

It is this last piece of information that seems to deserve our criticism. Whom was Alexander

'pursuing' when he was recalled? Darius? (This is the natural inference from what has

gone before.) But how dared he even begin to pursue anybody when he knew nothing as

yet of the progress of the battle elsewhere? The premature pursuit after a local success was

one of the surest and most attractive ways of losing a battle, as Demetrius Poliorcetes was to

demonstrate at Ipsus to the next generation of soldiers. And especially, what was happening

to Alexander's right flank-guard (Group B) while all this was going on? We left it (at the

16 It is

possible perhaps that a hint of this development of the beginning of the outflankiing-attack of which I have

is to be found in the mistake of Diodorus (59. 2-see note 9 just quoted Arrian's version, one can see how Diodorus

above) in making Darius command the Persian left. The (or his source) could have got the idea of Darius' being in

mistake occurs just when Diodorus begins his description command of the Persian left.

of a cavalry battle on the Macedonian right in which the

Persians have the best of it, and in which the personal 7 Arrian ibid., 3.- 4 if.

18 Id., 14- 5 and 15. I ff.

troops of Darius are engaged. If this is really his version 19 Id.,?5. I ff.

This content downloaded from 137.149.3.15 on Thu, 28 Mar 2013 14:18:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALEXANDER'S GENERALSHIP AT GAUGAMELA 83

end of Phase i) momentarily holding its own against greatly superior numbers; but from

that moment it (and its opponents) seem almost to vanish into thin air.

The important thing is that, once Alexander had launched himself at the head of the

'Companions' in their charge against Darius, and until he had disengaged and re-formed

them, all the troops to the right of the ' Companions ' in the original order of battle (i.e., the

right flank-guard Group B) had to cope with all the Persian troops to the left of Darius in the

original Persian order of battle. The Plan (p. 78) indicates what a disparity of forces this

means. Arrian dismissesthe whole matter in the sentence s8 of

'

V'b KEpaSippah63vTcovcrO-ro0S @op[ei0raacrv this-rrEpfl'WrniEovTrE

is the charge

-rTv TTEP6co Epcba-rco T-rv wrrEpi'Ap?'rlv:

of Aretes already mentioned on p. 81 above. I find it very hard to accept this as a full explana-

tion of what happened, because the Persian opposition here amounted altogether to something

between one third and one half of their whole army, whereas oi IrEpi 'ApiTrrlvwere, at the

most, 8oo Thracian lancers: 20 and even if oi -TrEpi'ApITrvbe taken to mean not merely the

unit of Aretes himself but the whole of the flank-guard, even this can have amounted to only

1500 cavalry at the most (including the 8oo already mentioned), and perhaps 6ooo infantry,

of whom all but about Iooo were Greek mercenaries.21 Looking back for a moment to what

I called Phase I of the battle, we saw there that the Greek mercenaries, cavalry and infantry,

with a small force of Paeonian cavalry, had a hard fight against the troops of the extreme

Persian left, the picked Bactrian and Saca horse reinforcedby the mass of the Bactrian cavalry.

When the second outflanking wave came on (the movement discussed above in which the

Persian left-centre and even Darius in the centre took part), the troops against whom Aretes

charged must have been those close to the centre, since the small gap which he made, and which

Alexander used, enabled Alexander to charge 'for Darius himself'. There remained,

therefore,between these troops and the Bactriansof the extreme Persianleft the units catalogued

by Arrian at III I I. 3; namely, Dahae and Arachosians (if they did not operate with the

Bactrians), the whole mass of the Persians themselves (surely one of the largest ethnic units

of the whole army?), the Susians, and the Cadusians. Against these forces, together with the

Bactrian wing, one would hardly have expected that the units of the flank-guard would hold

out indefinitely, for not one of them, except the Agrianians, was in any sense a corpsd'Jliteof

Alexander's army, and in total they were heavily outnumbered. One would have expected

Group B to be overwhelmed fairly quickly, leaving the phalanx with its right 'in the air'

and exposed to a flank attack if the enemy cared to make one. In fact, there are many of

the ingredients of a lost battle for Alexander, if the right flank-guard were left to its own

devices.22

What happened to this right flank-guard (Group B)? The possibilities seem to be three.

First, it is just possible that Group B succeeded in holding its own unsupported throughout

the battle, though it seems unlikely for the reasons I have just mentioned. Second, it is

possible that Bessus, the Persian commander of this flank, ceased fighting, whether from

treachery or prudence, as soon as he knew that Darius had fled, or even earlier. The idea

of treachery is attractive at first sight, in view of the subsequent history of Bessus, but the very

fact of his conspicuous treachery later makes it improbable that his treachery here (if it existed)

should never have been mentioned by the historians of the war. I take it, therefore, that a

premature retreat by Bessus is just a possibility, but no more. The third possibility is that

Group B was supported in the course of the battle, and at the earliest possible moment; and

20 See Tarn, AGSS pp. I57 ff., for an analysis of the originally, 5000 strong (Diod. XVII 17. 3). The archers

Balkan (non-Macedonian) cavalry contingents at Gauga- and Agrianians together numbered Iooo (Diod. ibid.).

mela: there were four (the other three being the Paeonians, 22 While I hesitate to place reliance on the account of

and the Thracians and Odrysians of the left wing), and Curtius, so full of confusions (see note 26 below), I would

together they cannot have amounted to more than I300- point out that one long passage (IV 15. 18-23), when

400o horse, but this contingent of Aretes may well have allowance is made for all its inaccuracies and misplace-

been by far the largest of the four. ments, does give the impression of a hard battle on the

21 These figures cannot be regarded as certain, but it

right flank, not only before but also after Alexander himself

seems probable that the mercenaries of Cleander here (and of course the 'Companions') were already com-

(ol dpXaiol Kaho?cEVOI ?bvoi-Arrian III 12. 2) are the mitted: it may be true, as Curtius says (ibid. 21 ff.), that the

contingent which crossed into Asia with Alexander Agrianians here served him well.

This content downloaded from 137.149.3.15 on Thu, 28 Mar 2013 14:18:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

84 G. T. GRIFFITH

in this case there is no one who can have supported it except Alexander himself.23 By this

interpretation Alexander, after his successful charge and the flight of Darius, wheeled to the

rightwith his ' Companions ' in order to deal with that sector of the battle which he knewto

be in danger and in order to relieve the only group of his forces which he knew,at that moment,

to be in some need of relief. The point is well made by Dr. Tarn that Bessushimself and his

Bactrians got away from the battle as a unit, undefeated-Kcdi ,Oivcirr (sc. Darius) oi rE

B1<KTplO1 i'ToTTrE,CdoTOTE•E v rTi~ X orXOcVVEXv, ---: whatever •this strange phrase

.

may mean, it must surely indicate that, the Bactrians retired as a unit and without being badly

mauled.24 It might be argued that they could hardly have done this if Alexander did indeed

wheel to the right with the ' Companions' to ' clean up ' that sector of the battle. There is

weight in this argument, but not (in my view) overwhelming weight. When Alexander

wheeled right (as I suggest), his first opponents would be the Persians of the left-centre, and

his last opponents as he ' rolled up ' the Persian left wing would be the Bactrianson the outside.

It is not impossible that the Bactrians on the extreme left had time to see what was coming

and to get away before it came. As for the Persiansjust mentioned, the same passage of Arrian

is rather strong evidence for their having been badly mauled in the battle, since it says that

few Persians were with Darius as he made for Media, and those few belonged to his personal

troops (stationed in the centre)-not, that is to say, to the main mass of the Persians of the

left-centre to which we are now referring: these last Persians, at least, did not escape as a

unit, in fact they are never heard of again. They may perhaps be held to support my view

that something stronger than ' Aretes and his men ' had passed their way.

Altogether, the ' third possibility' of my previous paragraph seems to me to give by far

the most reasonable answer to this question, in that it shows Alexander doing the natural

and indeed the necessary thing, the logical sequel to the disposition of his forces in the first

place, and to the first (defensive) phase of the battle which he had directed in person. My

own feeling is that the story as we have it requires this interpretation (or something to take

its place) even if there were no additional hint of it in the ancient evidence. But I think that

there are hints, and that this interpretation may also clear up two other matters which are

themselves obscure.

The first of them (one of Arrian's ' loose ends ') concerns the detachment of Indian and

Persian cavalry which charged through the Macedonian phalanx when a gap appeared (see

above, p. 82) through (or round) the second line of infantry (Group D),25 and then on to the

camp in rear of the Macedonian army. It was almost certainly this cavalry on its way back

which encountered Alexander and the ' Companions' on theirway to relieve Parmenion in

response to his appeal: 26 and this encounter (planned by neither party) produced the most

23 The only other body of troops near enough to support is the Indians and Persians who were not (see Plan I and

it was the 'second line ' of infantry (Group D); but they Key). The Indian cavalry were in the true centre, with

were soon fully occupied in facing about and driving enemy Darius, and ' the most and best of the Persians ' must surely

cavalry out of the Camp (Arrian III 14. 6). be the King's Guard, as Dr. Tarn says in his account of

24 Arrian III i6. I. Tarn AGSS p. 187. The figures of the battle (AGSS p. 187). But the Indian cavalry and

Curtius (IV 12. 6 f. and V 8. 4) for the Bactrians in the the Royal Guard must (one would think) have taken part

battle and later in Media are of little value in this con- in the great outflanking movement described on pp. f.,

nexion, since there may have been many desertions after and this movement took them into battle somewhat 8I to the

the defeat. In any case, they cannot be allowed to stand left (Persian left) of their original position in the centre,

in the way of our accepting this statement of Arrian. whereas the gap in the Macedonian phalanx occurred to

25 The phrase here used does not necessarily mean that the (Persian) right of their original position. It does not

they did break through the second line of infantry in make sense. The solution I propose (though with the

addition to riding through the gap in the first line. utmost diffidence) is as follows: When the gap in the

26 Arrian III 14. 4 ff. This is the view of all the modern phalanx appeared, the cavalry which used it was the

writers cited above. This Indian and Persian cavalry, Parthian, which was in a good position to do so. At the

however, is in itself something of a problem, because it is time when that happened, the Indians and the Royal

not easy to see how it found itself anywhere near the gap Guard were already involved in the flank battle; but at

when it appeared. The enemy opposite to the fifth taxis some moment they, some or all of them, broke through the

of the phalanx were the troops of the Persian right-centre flank-guard (and with the 'Companions' now engaged

(the 'inside' units of Mazaeus). When Arrian describes there was little to stop them), and rode to the Camp.

the return of this cavalry force a little later (15. I), he calls When the time came for looting to cease in the Camp,

them ' the Parthians and some of the Indians and the most all the enemy cavalry returned together, and met Alexander

and best of the Persians'. Now the Parthians were in the and the 'Companions', now disengaged.

right place, originally, to take advantage of this gap: it If this explanation is right, Arrian has omitted one of

This content downloaded from 137.149.3.15 on Thu, 28 Mar 2013 14:18:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALEXANDER'S GENERALSHIP AT GAUGAMELA

85

desperate fighting of the whole battle, and was responsiblefor the death of sixty of the ' Com-

panions ' themselves."7 No one, so far as I know, has shown satisfactorilyjust how and where

it took place. What is certain is that the enemy cavalry did not seek to return by making

a wide circuit of one or other flank of the fighting armies, for a reason which I will show

presently. Nor did they charge back throughthe Macedonian army, taking it in rear, because,

had they done so, the effect would have been very great and we should certainly have heard

more of it: this is, in fact, what they oughtto have done after their first successful charge,

instead of wasting their success in Alexander's camp."8 The remaining possibility is that they

returned by a route which both was short and looked safe, namely where they could see a

gap already in existence in the Macedonian

line. Two such gaps suggest themselves,

and the first is the one by which they had

originally broken through;29 but I hope to

show that it is more likely to have been by C

the second gap that they returned. This --

second gap did exist by my interpretationof 7;---.. .-

b c

Alexander's movements after the flight of A

Darius-the space where the 'Companion'

cavalry had been originally, a space which

grew wider as the 'Companions' wheeled

to the right and as that whole sector of the

battle detached itself from the rest when the FIG. 2.-SKETCH OF A LATE

Persians here began to withdraw. In fact PHASE OF THE BATTLE OF

the battle by this time is in three pieces. V GAUGAMELA.

Only Parmenion's wing and its opponents

(A) have stayed on much the same ground as that which they covered originally. The four

right-hand rTaEl<of the phalanx and the three battalions of the hypaspists (B) have advanced

at infantry pace driving the enemy before them. The ' Companions' have wheeled to the

right, and with the right flank-guard (C), have broken away from the original battle ground

as their opponents retreated. See Fig. 2.30

the two break-throughs, and has transferred the agents of mean, in a sense, two pieces of good luck, in the sense

this one (the Indians and the Royal Guard) to the other that a second body of cavalry should have followed the

one, which really belongs to the Parthians. The account political rather than the military aim. It would not be

of the battle by Curtius is such a nightmare of confusion two mistakes by the Persian command, but the same

that I hesitate to use it either to confirm or to stultify any mistake committed twice, by two of its executives. If the

explanation of any particular incident. But allowing for thing really did happen twice over, it reveals either a

the fact that sometimes (but not always-that would be pitiful incompetence in the Persian command (in this case

too simple) he says right wing when he means left and obviously Darius himself), or else a failure by the command

vice versa, I think it cannot be denied that Curtius believed to make its wishes clear to its fighting leaders, and of the

(if he ever thought about it at all) that there were two two alternatives the second is perhaps the more likely.

break-throughs by enemy cavalry, one by cavalry of the It is incredible that Darius should have said 'Rescue the

wing commanded by Mazaeus (he calls them Cadusians Royal Family even if it means losing the battle'. But it

and Scythians, IV 15. 5, 9 ff., 12 ff. and I8 f.), the other is comparatively easy to believe that he said to Bessus and

by cavalry of the wing commanded by Bessus (these he Mazaeus, ' It is vital to rescue the Royal Family', perhaps

calls Bactrians, IV 15. 20 and 22). The fact that all these naming a prize for the man or men who should do it. In

bodies of cavalry (Cadusians, Scythians, and Bactrians) this case, the two generals would no doubt hand on the

in reality came under the command of Bessus (see Plan I message to their unit commanders and they to their units:

and Key) is not perhaps an insuperable obstacle, if we can and the handing-on process, particularly when it is handing-

bring ourselves to use Curtius at all for incidents in the down, is a peculiarly vulnerable one. It could well have

battle, to our using him here in support of the view which ended in an intense rivalry among the cavalry units

I have just suggested, that there may have been really two (Persians, Indians, Parthians, Bactrians, Cadusians and

break-throughs by enemy cavalry to the Camp. the rest), all determined that it should be they who won

The interesting thing about all this is the question of this prize. But this is conjecture, based on nothing more

generalship which it raises: this time, of Persian general- solid than a reading of human nature and an experience

ship. It has long been recognised that it was a piece of of its occasional impermeability to all except the most

good luck for Alexander that a break-through by enemy exact of' briefing '.

27 Arrian

cavalry should have wasted itself on the Camp instead of III 15. I f.

winning the battle for Darius or at least trying to win it; 28 The second line of infantry later faced about to prevent

and the motive for the mistake was no doubt the political it, and then drove them out of the camp (Arrian ibid. 14. 6).

motive of trying to recover the King's family from its 29 So

(e.g.), Judeich loc. cit.

30 It will be realised that this little

captivity (Diod. XVII 59. 7; Curt. IV 14. 22). But plan is highly

what if there were two break-throughs? That would schematic, and that the reality must have been much more

This content downloaded from 137.149.3.15 on Thu, 28 Mar 2013 14:18:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

86 G. T. GRIFFITH

Putting oneself in the place of a Persian cavalry officerre-forminghis men after plundering

the camp (D), what he must first want to know is 'Have we won the battle or have we lost

it? ' The fact that his plundering of the camp has been interruptedby the arrivalof Alexander's

second-line infantry (Arrian I4. 6) is not and when he looks towards the main

one .encouraging,

mass of dust

battlefield, he will see stationary (where Parmenion is still fighting himself

free-A), one slowly receding mass of dust (B), and one mass more rapidly receding (C) where

Alexander and the cavalry are at work. It looks as if the battle is being lost: they must

retreat in good order-which way ? Arbela is the natural goal for a retreating Persian army.

From their present position they could reach it most easily by passing on eitherside of B, less

easily by passing to the outside of A or C. I take it that they chose one of the two easier ways,

and of the two I prefer the way between C and B, for a reason which I will show in a moment.

If the enemy cavalry returned through this gap between B and C it is very easy to see how

they unexpectedly encountered Alexander going to the support of Parmenion, since this line

of retreat takes them nearly at right-angles across the path of Alexander's movement from his

extreme right flank towards his extreme left.31

There is an interesting confirmation of this view in Arrian's remark about the Macedonian

casualties which resultedfrom this cavalry action: ' here fell about sixty of the " Companions"

and among the wounded were Hephaestion himself and Koinos and Menidas '.32 It is the

presence here of Koinos that probably enables us to fix more nearly the site of this action.

Koinos was no cavalry commander in attendance on Alexander with the 'Companion'

cavalry, but commanded the first (right-hand) taxis of the phalanx, next to the hypaspists,

who had been next (on the left) to the 'Companions' in the original order of battle. The

right of the phalanx was never held up in its advance (the break in the phalanx occurred at

the fifth taxis),33and we must suppose that Koinos advanced till he found himself involved

(or was able to involve himself) in this cavalry action in which he was wounded. The cavalry

action, therefore, took place behind what had been the Persian line at the moment when the

two armies engaged, but not so very far behind, since it was possible for a Macedonian infantry

commander to reach the spot. Since the taxisof Koinos is exactly in the middle of the advanc-

ing line of Macedonian infantry, it cannot be said to support strongly the right-hand gap (as

against the left-hand gap) as the more probable avenue of escape for the enemy cavalry,

though a glance at Plan II will suggest the right-hand one as the more probable; but what

it does do is to exclude altogether the routes round the outside of either Macedonian wing,

since Koinos could never conceivably have found himself in those sectors of the battle at all.

But to return to these distinguished officers who were casualties, the name of Menidas

is even more useful to us than that of Koinos, because it links up with, and confirms, my

suggestion about the course of the battle on the Macedonian right wing; about the movements,

in fact, of Alexander himself. Only one Menidas is known,34 and he is the officer already

mentioned in command of the mercenary cavalry in the forefront of the right flank-guard

(Group B, see above p. 79),35 among the troops to whose support (in my view) Alexander

untidy: my A, B, and C are not intended to represent (III 15. 2), meant that they had to fight for their lives

three still intact battle lines, but to cover the three main instead of merely riding for them. My interpretation,

groups of the army, which was by this time much broken however (see Plan), allows of the probability of their being

up by the manoeuvres of the several units in attack, pursuit surprised by the meeting, since Alexander could appear

or (in the case of A) in self-defence. rather suddenly out of the dust created by the other

31 It may be said that the gap created by the wheeling formations on the extreme right of the Macedonian army,

(on my interpretation) of the 'Companions' would still cf. Diod. XVII 60. 4 and 6 for the dust of this battle.

exist if, instead of wheeling, they had charged straight 32 Arrian ibid., 15. 2.

forward 'in pursuit' (presumably of the fleeing Darius): 33 Id., I4. 4.

in this case the enemy cavalry returning could still use 34 See H. Berve, Das Alexanderreich auf prosopographischer

this gap, and still meet Alexander as he returned 'from Grundlage,No. 508.

pursuit' to help Parmenion (which is certainly what 35 Arrian ibid., 12. 3. Curtius (IV 5. 12) mentions this

Arrian says he did-loc. cit.). The objection to this, and Menidas as moving with his mercenary cavalry to the rear

it is a strong one, is that although in these conditions the at an early stage in the battle, to drive enemy cavalry out of

two forces could have met if both had wanted to meet, it is the Camp. It seems impossible that this can be right, unless

certain that the enemy cavalry wanted anything rather Arrian's account of the battle is to be jettisoned entirely in

than this. They were not now trying to do damage, they favour of the confused story of Curtius. In any case, Curtius

were trying to escape; and this meeting, as Arrian says makes Menidas return to Alexander almost immediately.

This content downloaded from 137.149.3.15 on Thu, 28 Mar 2013 14:18:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALEXANDER'S GENERALSHIP AT GAUGAMELA 87

had wheeled right, and from whom (in my view) he was making his way when he met the

retreating enemy cavalry. This means, surely, that at the moment when Alexander received

Parmenion's message he was in contact with Menidas on the extreme right of his line, and

ordered him with his mercenary horse to accompany the 'Companions' to the rescue of

Parmenion. To suppose otherwise is to suppose some accidental meeting of Alexander and

Menidas after Alexander has begun ' to pursue' and after Menidas (by some means unexplained)

has freed himself from the attentions of Bessus and great masses of the Persian army: and

though accidents do happen in battle (and important accidents too), it seems much more

probable that this meeting was brought about in the way which I have suggested. I take it,

then, that Alexander and Menidas had met and joined up on the extreme right, and when

that happened of course the danger to that flank was over, thanks to the wheeling movement

of the ' Companions': in fact, when he got Parmenion's message he had already got the

better of the troops of Bessus (though the Bactrians themselves were able to get away intact),

and had driven them off in disorder at least to a point where there was no danger of their

re-forming and renewing the attack. This driving-off of Bessus, indeed, can explain perhaps

Arrian's 'pursuit' from which Alexander (he says) was recalled by Parmenion's message."3

On this view, it was no wild pursuit of Darius, endangering the issue of a battle still undecided,

but a rational and necessary counter-attack directed against Bessus, whose outflanking wing

constituted the greatest and most obvious danger to the Macedonians, a danger to which

Alexander was alive from the start, as the preliminaries of the battle clearly show.37

This brings us to another minor obscurity in Arrian's account, the message itself of

Parmenion. That it was sent seems certain: and that it was delivered seems almost certain,

though Diodorus says it was not.38 It is very difficult to accept the evidence of Diodorus as

it stands, because to do so would involve rejecting Arrian's circumstantial account of the

movement to rescue Parmenion and of the cavalry action in which the sixty ' Companions '

were killed: and in general Arrian's account of the battle is orderly and lucid enough to carry

conviction that the movements which he describes did really take place in some form or other,

and are not mere inventions or misapprehensions of Arrian or his source. There is an over-

whelming probability, then, that the message did reach Alexander and that he moved in

response to it. Plutarch and Curtius say that it reached him when he was already far in

pursuit of Darius and likely to overtake him, and Arrian implies that he was pursuing Darius,

having given no indication that there was at that time any other group of fugitives for him to

pursue. Diodorus says that the message never reached Alexander becausehe was pursuing

Darius and was too far away, and though the information itself is probably false, the reason

seems to me to show a most remarkable common sense in the historian who is Diodorus'

ultimate source here: 39 it shows, in fact, a grasp of what was possible in the circumstances.

A glance at the plan will suggest that no messenger from Parmenion could possibly have

reached Alexander if he were already pursuing Darius (presumably towards Arbela): such

a messenger would have had to begin by riding through much of the Persian army in retreat,

or (alternatively) by making so wide a detour as to leave him with no chance of overtaking

Alexander, who did not 'pursue' at a jog-trot. Diodorus seems to me to be right thus far,

that if Alexander had been pursuing Darius, the messengers would have done exactly what

he implies that they did, namely gallop along and behind the Macedonian fighting-line to

the place where they knew that Alexander had been, find him no longer there, learn that he

was far away 'pursuing' and then return to Parmenion rrtpacK-roL.40

36 As for how a mistake about 'the

pursuit' can have clearly, that Alexander was still unaware of the state of

arisen, it seems very unlikely that Ptolemy did not know the battle on his left flank: the position there was serious,

the truth about Alexander's movements and their motive; but he did not know this until he got Parmenion's message.

but I suggest that a description by Ptolemy of a wheeling 38 Arrian ibid., 15. I: Curt. IV 16. I if: Diod. XVII

movement by Alexander to the right when Darius fled, 6o. 7: Plut. Alex. 33.

if it were not phrased carefully and explicitly, could perhaps 39 Diod. id., 4 and 7.

have been misinterpreted by Arrian as the beginning of a 40 Id., 7 . . . 6 nTapEviEcv i~gEP

ivv TIVaS T OV TSEp aITO6v

pursuit of Darius. itrwrrCv rrp6b TbV 'AAixav8pov, Mycv Ka-rT&TarXoS [oiTrjat..

37 I am assuming of course, what all our sources indicate 6OSCs 8 Tro'TrOV Kxi Tb6v'AXaCv-

wTapayyEWevwTpa-rTTr6VTCaV

T"O

This content downloaded from 137.149.3.15 on Thu, 28 Mar 2013 14:18:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

88 G. T. GRIFFITH

This I take to be what would have happened if Alexander had been pursuing Darius;

the message would never have been delivered. But if he never began to pursue Darius (as

I have tried to show), it becomes much easier to see how it was possible for Parmenion to send

a message which did reach him and bring him over from the extreme right towards the extreme

left. If the wheeling-right of the 'Companions' be accepted as fact, and if the 'pursuit'

mentioned by Arrian is really Alexander's repulse and driving-off of the troops of Bessus on

the flank, then Parmenion's messengers could reach him fairly easily, riding in safety behind

their own lines all the way.

Perhaps it is not irrelevant to speculate here about how this discrepancy in the tradition

concerning Parmenion's message ever arose, and particularly how the story told by Diodorus

assumed its present form: for it is certainly remarkable to be given so very good a reason why

something never happened, when in fact it is practically certain that it did happen. The clue

is probably to be found in the later story of Parmenion and, especially, in his death. Whether

or not Alexander was legally justified in causing Parmenion to be killed, it is scarcely possible

that the act was universally or even generally popular."4 It was an act that probably required

some justification beyond the mere letter of the law, and there are signs that persons who

wished to stand well with Alexander deliberately set out to supply this justification by blacken-

ing the memory of Parmenion. Of all the occasions on which Parmenion is recorded to have

offered his advice to Alexander, there is only one (I think) when his advice is taken.42 The

originator of the 'bad' tradition about him was probably Callisthenes, who is quoted as

having written of Parmenion's part in the incident we are now considering, the message to

Alexander: 60Aosyap aic-rov-ral fappEvicova xaTr'EKEiV1rV p6XrlvVcopbV yEVE•aCi Kai

"TlVTlVE

GSrVEpyov,Eis1TE To0 yilpOS ij65 -Ti S Tr6AprE1TE

TTfi @ouaOiavKal T6V OyKOV,

cos KactXXcivrs TrcapachXovTroSS Papuv6vEVOVKai

qTq)ri,TfiS 'AAXE&vapov5uv&pEco This

rpoq•60voIvrCa.43

last accusation falls not far short of treason, and was easy to bring against a dead man whose

son had been found guilty of high treason by the Macedonian army-assembly. That is not

to say that many people can have believed in its truth at the time, or can have been glad to

see or hear it made, indeed there were probably many who resented it, as Cleitus is said to

have resented the undue glorification of Alexander and the belittling of Philip in the famous

quarrel scene which ended in his death.44 It is from such resentment that 'apologies' for

Parmenion may well have arisen, and in particular it is not difficult to imagine that his part

in the battle of Gaugamela may have become a subject for controversy (comparable

perhaps

with the Jutland controversy in our own time). If this were so, the version of the message

incident which Diodorus preserves (that it was sent but did not arrive) would represent the

counter to the 'hostile' (and equally false) version, that its arrival had the worst

possible

effect, of allowing Darius to escape.45 As for Arrian, if his source here is Ptolemy,46 he may

have mis-interpreted Ptolemy and so made his mistake about the 'pursuit' (see note 36); or

it is just possible that Ptolemy himself writing long afterwards was confused by a 'cloud of

witnesses '. Whatever the cause, it would not be surprising if this distorted tradition of the

message of Parmenion contributed not a little to those obscurities in Arrian's account which

it has been my business to discuss.

My conclusions, however, are these:-

(I) Arrian's account of this battle is less complete than appears at first sight. Every-

thing that Arrian describes did really take place (except the first ' pursuit '), but he has

Spov rrwOopov 1TrroA TtiS7r&EcoS KaT rToVSitcoyp6v 46 So E. Kornemann, Die Alexandergeschichte des K6nigs

oirrot &WrpKTOI .... d•VEarr1Toal PtolemaeusI vonAegypten,pp. 56 ff., and p. 130.

t 7&ravij•eov

41 See A.J.Ph. 98 (1937) 1o9 f., where A. J. Robinson 47 Tarn points out most acutely (AGSS p. 177, n. i)

deduces a legal justification from Curtius VI I I. 20 how Ptolemy may have

damaged the reputation of his

supported by Arrian III 27. I ft. (later) great enemy Antigonus by merely omitting all