Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ilovepdf Merged Merged

Ilovepdf Merged Merged

Uploaded by

Ma. Trina AnotnioOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ilovepdf Merged Merged

Ilovepdf Merged Merged

Uploaded by

Ma. Trina AnotnioCopyright:

Available Formats

BM2021

ABSORPTION AND VARIABLE COSTING

Absorption, Variable, and Throughput Costing

Income is one of the many significant measures managers use to make decisions and evaluate operational

performance. In a manufacturing firm, two (2) alternative accounting treatments of fixed manufacturing

overhead can result in different reported income amounts for the company. The difference in reported

income can alter management’s view of the profitability of a particular decision or segment of the

company (Hilton & Platt, 2017). Normally, accountants and managers make a judgment when measuring

income, and one of the most important factors is choosing the appropriate method in calculating the

product cost.

When managers realized that product costing would affect their evaluation, they started to pay attention

to the determination of product costs. The two (2) product costing methods that differ in the treatment

of the fixed manufacturing overhead are absorption costing and variable costing.

1. Absorption Costing. It is also known as “full costing” or “conventional costing.” In this method, all

manufacturing costs (i.e., direct materials, direct labor, and manufacturing overhead) are recognized

as product costs, regardless of whether they are variable or fixed (Garrison et al., 2018). This means

that all manufacturing costs are assigned to (or absorbed by) the units produced.

Figure 1. Manufacturing costs for absorption costing

Figure 1 illustrates all manufacturing costs needed to produce the product. These are direct

materials, direct labor, variable manufacturing overhead, and fixed manufacturing overhead. As the

goods are produced, these costs are recognized in the balance sheet as part of inventory. As the

goods are sold, all manufacturing costs of the units sold will be part of the cost of goods sold (an

account recognized in the income statement). In using the absorption costing, the fixed overhead per

unit is computed based on the level of production.

Since absorption costing includes all manufacturing costs in costing the product, it cannot be used to

prepare a contribution margin income statement (a measure for evaluating the performance of a

segment or department). In this regard, an alternative costing is used by the management for internal

use only. This is called variable costing.

2. Variable Costing. It is also known as “marginal costing” or “direct costing.” It recognizes that the cost

of the product must include only those production costs that vary directly within the volume of

production. This method only includes variable manufacturing costs in the cost of a unit of product.

It treats fixed manufacturing overhead as period cost.

Figure 2. Manufacturing costs for variable costing

07 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 1 of 4

BM2021

In Figure 2, all manufacturing costs (except for the fixed manufacturing overhead) are considered

part of the cost of the product. These costs are recognized in the balance sheet as part of the

inventory. As the goods are sold, the cost of the product will be recognized in the income statement

as cost of goods sold. However, the fixed manufacturing overhead will be considered as period cost,

i.e., the cost will be expensed as incurred. This is because this cost will be incurred whether or not

production occurs, and it is improper to allocate these costs to production and defer current costs of

doing business.

Under variable costing, there is a method called throughput costing. It is also known as

“supervariable costing,” which is an extreme form of variable costing in which only direct material

costs are considered product costs included as cost of inventory. All other costs are period costs that

are expensed as incurred.

Table 1 shows the principal differences between variable and absorption costing:

Variable Costing Absorption Costing

1. Cost segregation Costs are segregated into Costs are seldom segregated

variable or fixed. into variable and fixed costs.

2. Cost of inventory Cost of inventory includes only Cost of inventory includes all

the variable costs. the manufacturing costs,

variable and fixed.

3. Treatment of fixed Fixed manufacturing overhead Fixed manufacturing overhead

manufacturing overhead is treated as period cost. is treated as product cost.

4. Income statement Distinguishes between variable Distinguishes between

and fixed costs production and other costs

5. Net Income Net income may differ from each other because of the difference

in the amount of fixed overhead costs recognized as expense

during an accounting period. In the long run, however, both

methods give substantially the same results since sales cannot

continuously exceed production, nor can production continually

exceed sales.

Table 1. Differences between variable costing and absorption costing

Reconciliation of Net Income

The following observations can be developed regarding variable costing and absorption costing in relation

to production and sales (Garrison et al., 2018):

1. Production equals sales. When units produced is equal to units sold, there is no change in

inventory. The same net income will be realized regardless of the method used.

2. Production is greater than sales. When units produced exceed units sold, there is an increase in

inventory. The fixed overhead expensed under absorption costing is less than the fixed overhead

expensed under variable costing. Therefore, the net income reported under absorption costing

will be greater than the net income reported under variable costing.

3. Production is less than sales. When units sold exceeds units produced, there is a decrease in

inventory. The fixed overhead expensed under absorption costing is greater than the fixed cost

expensed under variable costing. Therefore, the net income reported under absorption costing

will be less than the net income reported under variable costing.

When inventory increases or decreases during the year, reported income differs under absorption and

variable costing. This results from the fixed overhead that is inventoried under absorption costing but

expensed immediately under variable costing. The following formula may be used to compute the

07 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 2 of 4

BM2021

difference in the amount of fixed overhead expensed in a given period under the two (2) costing methods

(Hilton & Platt, 2017):

𝑫𝒊𝒇𝒇𝒆𝒓𝒆𝒏𝒄𝒆 𝒊𝒏 𝒇𝒊𝒙𝒆𝒅 𝒐𝒗𝒆𝒓𝒉𝒆𝒂𝒅 = 𝑪𝒉𝒂𝒏𝒈𝒆 𝒊𝒏𝒗𝒆𝒏𝒕𝒐𝒓𝒚 𝒖𝒏𝒊𝒕𝒔 𝒙 𝑭𝒊𝒙𝒆𝒅 𝒐𝒗𝒆𝒓𝒉𝒆𝒂𝒅 𝒑𝒆𝒓 𝒖𝒏𝒊𝒕

The difference in fixed overhead is also the difference between the net income under the two (2) methods.

Pro forma reconciliation

1. Absorption to Variable Costing

Absorption costing Net Income P xxx

Add: Fixed overhead in beginning inventory xxx

Less: Fixed overhead in ending inventory xxx

Variable costing net income P xxx

2. Variable to Absorption Costing

Variable costing Net Income P xxx

Add: Fixed overhead in ending inventory xxx

Less: Fixed overhead in beginning inventory xxx

Absorption costing net income P xxx

EXAMPLE:

ANJY Corporation has the following information in its first year of operations in 201A:

Units produced 40,000

Units sold 36,000

Selling price per unit P60

Variable manufacturing costs P24 per unit produced

Variable selling expenses P6 per unit sold

Fixed manufacturing costs P500,000

Fixed administrative expenses P250,000

Assume that the actual production is the same as the normal operating level for the year. Income

statements under the two (2) methods will be presented as follows:

ANJY Corporation

Income Statement (Absorption Costing)

December 31, 201A

Sales (36,000 x P60) P2,160,000

Less: Cost of Goods Sold (36,000 x P36.50) 1,314,000

Gross Profit 846,000

Less: Selling and Administrative Expenses

Variable Selling (36,000 x P6) P216,000

Fixed administrative 250,000 466,000

Net Income P380,000

The cost of goods sold by P36.50 per unit is computed as the sum of variable and fixed manufacturing

costs per unit [P24 + (P500,000/40,000)]. The cost of ending inventory will be P146,000 (P36.50 x P4,000

units unsold).

07 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 3 of 4

BM2021

ANJY Corporation

Income Statement (Variable Costing)

December 31, 201A

Sales (36,000 x P60) P2,160,000

Less: Variable Costs

Cost of Goods Sold (36,000 x P24) P864,000

Selling Costs (36,000 x P6) 216,000 1,080,000

Contribution Margin 1,080,000

Less: Fixed Costs

Manufacturing Costs 500,000

Administrative Costs 250,000 750,000

Net Income P330,000

The income statement under variable costing separates variable costs and fixed costs and shows a

contribution margin instead of a gross profit, as shown under absorption costing. The cost of ending

inventory under variable costing is P96,000 (P24 x 4,000 units unsold).

As shown in the two (2) income statements, the difference between the net income of the two (2)

methods is P50,000. This is also the difference between the cost of ending inventory and comprises the

fixed manufacturing overhead in ending inventory of P50,000 (P12.50 x 4,000 units unsold).

To reconcile the net income in the two (2) methods, it shall be computed as follows:

P330,000 Absorption costing net income P380,000

Variable costing net income

Add: Fixed manufacturing costs in Less: Fixed manufacturing costs in

ending inventory (4,000 x P12.50) 50,000 ending inventory (4,000 x P12.50) 50,000

Absorption costing net income P380,000 Variable costing net income P330,000

Assume that the direct material per unit is P12; the following is the income statement using throughput

costing:

ANJY Corporation

Income Statement (Throughput Costing)

December 31, 201A

Sales (36,000 x P60) P2,160,000

Less: Direct Materials (36,000 x P12) 432,000

Throughput Margin 1,728,000

Less:

Variable manufacturing costs (40,000 x

P12) P480,000

Variable Selling Expenses (36,000 XP6) 216,000

Fixed Manufacturing Costs 500,000

Fixed Administrative Expenses 250,000 P1,446,000

Net Income P282,000

In throughput costing, only the cost of materials is included in the cost of inventory. Direct labor and

manufacturing overhead costs are all treated as period costs, treating them as expenses as they are

incurred. This means that it is based on the units produced, not on the units sold. When production

exceeds sales, the net income reported in throughput costing is much lower than variable and absorption

costing.

References:

Garrison, R. H., Noreen, E. W., & Brewer, P. C. (2018). Managerial accounting. McGraw-Hill Education.

Hilton, R. W., & Platt, D. E. (2017). Managerial accounting: Creating value in a dynamic business environment. McGraw-Hill Education.

07 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 4 of 4

BM2021

COST–VOLUME–PROFIT AND BREAK-EVEN ANALYSIS

Cost-Volume-Profit (CVP) Analysis (Lalitha & Rajasekaran, 2010; Rante, 2016)

The cost-volume-profit (CVP) analysis determines how changes in costs and volume affect a company's

operating income and net income. This analysis assumes that the volume of production drives cost and

revenue.

The following are the objectives of CVP Analysis:

• Optimum pricing. It assists in estimating the market value of products and services to earn a

profit.

• Profit planning. It is essential in assessing the income or loss at different levels of activity.

• Exercise cost control. It assists in evaluating profit and expenses incurred to facilitate cost control.

• Forecasting profit. It assists in analyzing the relationship among earnings, costs, and volume to

precisely forecast the expected income of a business undertaking.

• Deciding on alternatives. It helps in analyzing various courses of action to make accurate and

informed decisions.

• Planning for cash requirements. It assists in planning for financial resources at a given volume of

output.

• New product decisions. It helps in launching a new product/service based on nature, the volume

of output, price, and volume of sale.

• Determining overheads. It helps in determining the amount of overhead cost to be charged at

various levels of activity because overhead rates are generally predetermined to a selected

volume of production.

• Setting up flexible budgets. It helps in estimating the required working capital, which indicates

costs at different levels of activity.

The basic formula used in CVP analysis is derived from the profit equation as follows:

𝑥𝑝 = 𝑥𝑣 + 𝐹𝐶 + 𝐷𝑒𝑠𝑖𝑟𝑒𝑑 𝑃𝑟𝑜𝑓𝑖𝑡

where:

p is the price per unit; x is the total number of units produced and sold;

v is the variable cost per unit; FC is the total fixed cost

ILLUSTRATION: An entrepreneur desires to earn a profit of P100,000 by selling 10,000 pieces of anime

figures. The fixed cost in producing the product is P200,000, while the variable cost per anime figure is

P20.

SOLUTION:

𝑥𝑝 = 𝑣𝑥 + 𝐹𝐶 + 𝐷𝑒𝑠𝑖𝑟𝑒𝑑 𝑃𝑟𝑜𝑓𝑖𝑡

10,000𝑝 = (10,000)(𝑃20) + 𝑃200,000 + 𝑃100,000

10,000𝑝 = 𝑃200,000 + 𝑃200,000 + 𝑃100,000

10,000𝑝 = 𝑃500,000

𝒑 = 𝑷𝟓𝟎

KEY POINTS: The entrepreneur must sell each anime figure for P50 to earn the desired profit.

09 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 1 of 3

BM2021

Break-Even Analysis (Lalitha & Rajasekaran, 2010; Rante, 2016)

Break-even analysis is an analytical technique for studying the relationship between costs and revenues.

It shows the profitability or non-profitability of an undertaking at various levels of activity, and as a result,

it indicates the point at which sales will equal total costs or the break-even point. This analysis depicts the

variable costs, fixed costs, total costs, sales value, break-even point, and profit or loss at different levels

of production or activities.

The following are some of the assumptions underlying break-even analysis:

• Cost variability concept. In this method, the concept of cost variability is valid, and the costs are

classified as fixed and variable costs.

• Fixed costs are constant. In this method, fixed costs remain constant, and there are certain factors

for which the costs may not change, whatever may be the level of activity.

• Segregation of semi-variable costs. In this method, semi-variable costs can be segregated into

fixed and variable.

• Constant selling price. In this method, the selling price does not change as the volume of sales

changes.

• No change in a product. In this method, there will be no change in the product if there is only one

(1) product. Also, the sales mix remains constant if there is more than one product.

• Short-term price level. In this method, the general price level remains stable at the short-run

level.

• Constant product mix. In this method, the product mix remains unchanged.

• Operating efficiency. In this method, the operating efficiency of the firm neither increases nor

decreases.

• Production and sales. In this method, the number of units of sales coincides with the number of

units of production so that the inventory may remain constant.

• Profit-volume ratio. In this method, the relationship between the contribution and selling price

of a product or service is represented in terms of percentage.

• Break-even point in units. In this method, the production level (where total revenues equal total

expenses) is represented in terms of the number of output or unit of product or service.

• Break-even point in values. In this method, the production level (where total revenues equal total

expenses) is represented in terms of the equivalent amount or peso value of a product or service.

ILLUSTRATION: Scented candles are sold at P100 per unit with a variable cost of P80 per unit and a

contribution margin of P20 per unit. The fixed expense of the business is P10,000 per year. Determine the

following: Break-even point in units; Break-even point in values; Profit for sales of 620 units; and Required

sales to earn a profit of P10,000 for the year.

PROCEDURE:

• Step 1. Determine the contribution margin per unit by deducting the variable cost per unit to the

selling price per unit:

𝐶𝑜𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑏𝑢𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑚𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑖𝑛 𝑝𝑒𝑟 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡 = 𝑆𝑒𝑙𝑙𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑝𝑟𝑖𝑐𝑒 𝑝𝑒𝑟 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡 − 𝑉𝑎𝑟𝑖𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝑝𝑒𝑟 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡

= 𝑃100 − 𝑃80 = 𝑷𝟐𝟎

• Step 2. Determine the profit-volume (P/V) ratio using the following formula:

𝐶𝑜𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑏𝑢𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑚𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑖𝑛 𝑝𝑒𝑟 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡 𝑃20

𝑃/𝑉 𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜 = × 100 = × 100 = 0.2 × 100 = 𝟐𝟎%

𝑆𝑒𝑙𝑙𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑝𝑟𝑖𝑐𝑒 𝑝𝑒𝑟 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡 𝑃100

09 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 2 of 3

BM2021

• Step 3. Determine the break-even point (BEP) in units using the following formula:

𝐹𝑖𝑥𝑒𝑑 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝑃10,000

𝐵𝐸𝑃 𝑖𝑛 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡𝑠 = = = 𝟓𝟎𝟎 𝒖𝒏𝒊𝒕𝒔

𝐶𝑜𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑏𝑢𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑚𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑖𝑛 𝑝𝑒𝑟 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡 𝑃20

• Step 4. Determine the break-even point (BEP) in values using the following formula:

𝐹𝑖𝑥𝑒𝑑 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝑃10,000

𝐵𝐸𝑃 𝑖𝑛 𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑢𝑒𝑠 = = = 𝑷𝟓𝟎, 𝟎𝟎𝟎

𝑃 0.2

𝑉 𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜

• Step 5. Determine the total contribution margin by multiplying the estimated number of units for

sale by the contribution margin per unit:

𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑏𝑢𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑚𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑖𝑛 = 𝐸𝑠𝑡𝑖𝑚𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑑 𝑛𝑜. 𝑜𝑓 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡𝑠 𝑓𝑜𝑟 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒 × 𝐶𝑜𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑏𝑢𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑚𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑖𝑛 𝑝𝑒𝑟 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡

= 620 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡𝑠 × 𝑃20 = 𝑷𝟏𝟐, 𝟒𝟎𝟎

• Step 6. Determine the profit for the sales of 620 units by getting the difference of total

contribution margin and total fixed cost for the year:

𝑃𝑟𝑜𝑓𝑖𝑡 = 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑏𝑢𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑚𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑖𝑛 − 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑓𝑖𝑥𝑒𝑑 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 = 𝑃12,400 − 𝑃10,000 = 𝑷𝟐, 𝟒𝟎𝟎

• Step 7. Determine the required sales to be made to earn a profit of P10,000 using the following

formula:

𝐹𝑖𝑥𝑒𝑑 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 + 𝐷𝑒𝑠𝑖𝑟𝑒𝑑 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑓𝑖𝑡

𝑅𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑟𝑒𝑑 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠 =

𝑃

𝑉 𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜

𝑃10,000 + 𝑃10,000 𝑃20,000

= = = 𝑷𝟏𝟎𝟎, 𝟎𝟎𝟎

0.2 0.2

References:

AccountingExplained. (2021). Cost volume profit analysis.

https://accountingexplained.com/managerial/cvp-analysis/

Cliffsnotes. (2020). Cost-volume-profit analysis. https://www.cliffsnotes.com/study-

guides/accounting/accounting-principles-ii/cost-volume-profit-relationships/cost-volume-profit-

analysis

Lalitha, R. & Rajasekaran, V. (2010). Costing accounting. India: Pearson.

Rante, G. A. (2016). Cost accounting. Mandaluyong City: Millenium Books, Inc.

09 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 3 of 3

BM2021

ACTIVITY-BASED COSTING

The Strategic Role of Activity-Based Costing (Blocher et al., 2019)

Activity-based costing (ABC) is a method for improving the accuracy of cost determination. While ABC is a

relatively recent innovation in cost accounting, it has been adopted by companies in varying industries

and within government and non-profit organizations. Here is a quick example of how it works and why it

is important. Suppose Jordan and two (2) friends (Joe and Al) go out for dinner. Each one (1) ordered a

personal-size pizza, and Al suggests ordering a plate of appetizers for the table. Jordan and Joe figured

they would have a bite or two (2) of the appetizers, so they agree. Dinner is great, but at the end, Al is still

hungry, so he orders another plate of appetizers, but this time, he eats all of it. When it is time for the

check, Al suggests the three (3) of them split the cost of the meal equally. Is this fair? Perhaps Al should

offer to pay more for the two (2) appetizer plates. The individual pizzas are direct costs to each friend so

that an equal share is fair, but while the appetizer plates were intended to be shared equally, it turns out

that Al consumed most of them.

There are similar examples in manufacturing. Suppose Jordan, Joe, and Al are also product managers at a

plant that manufactures furniture. There are three (3) product lines. Al is in charge of sofa manufacturing,

Joe handles dining room tables and chairs, and Jordan is in charge of bedroom furniture. The direct

materials and labor costs are traced directly to each product line. Also, there are indirect manufacturing

costs (overhead) that are associated with activities that cannot be traced to a single product, including

materials acquisition, materials storage and handling, product inspection, manufacturing supervision, job

scheduling, equipment maintenance, and fabric cutting. What if the company decides to charge each of

the three (3) product managers a “fair share” of the total indirect cost using the proportion of units

produced in a manager’s area relative to the total units produced? This approach is commonly referred

to as volume-based costing. Note that whether the proportions used are based on units of product, direct

labor hours, or machine hours, each of these is volume-based. But if, as is often the case, the usage of

these activities is not proportional to the number of units produced, then some managers will be

overcharged, and others undercharged under the volume-based approach. For example, suppose Al

insists on more frequent inspections of his production; then he should be charged a higher proportion of

overhead (inspection) than that based on units alone. Moreover, why should Jordan pay any portion of

fabric cutting if the bedroom furniture does not require fabric?

Another consideration is that the volume-based method provides little incentive for the manager to

control indirect costs. Unfortunately, the only way Jordan could reduce his share of the indirect costs is

to reduce the units produced (or hope that Joe and/or Al increase production)—not much of an incentive.

On reflection, the approach that charges indirect costs to products based on units produced does not

provide very accurate product costs and certainly does not provide the appropriate incentives for

managing the indirect costs. One solution is to use activity-based costing to charge these indirect costs to

the products, using detailed information on the activities that make up the indirect costs—inspection,

fabric cutting, and materials handling.

Role of Volume-Based Costing (Blocher et al., 2019)

Volume-based costing can be a good strategic choice for some firms. It is generally appropriate when

common costs are relatively small or when activities supporting the production of the product or service

are relatively homogeneous across different product lines. This may be the case, for example, for a firm

that manufactures a limited range of paper products or a firm that produces a narrow range of agricultural

products. Similarly, a professional service firm (law firm, accounting firm, etc.) may not need ABC because

labor costs for the professional staff are the largest cost of the firm, and labor is also easily traced to clients

06 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 1 of 5

BM2021

(the cost object). For firms other than these, the ABC approach may be preferred to avoid the distortions

from over costing or under costing that may occur using a volume-based approach.

Activity-Based Costing (ABC)

Activity-based costing (ABC) system is an approach that assigns resource expenses to cost objects such as

products, services, or customers. The premise of this costing approach is that a firm’s products and/or

services result from activities that require resources accompanying costs or expenses. Costs of resources

are assigned to the activities that use or consume resources (resource consumption drivers), and costs of

activities are assigned to cost objects (activity consumption drivers). ABC recognizes the causal or direct

relationships between resource costs, cost drivers, activities, and cost objects in assigning costs to

activities and then to cost objects (Blocher et al., 2019).

To develop a costing system, an understanding of the relationships among resources, activities, and

products and/or services is important. Resources are used to perform activities, and products/services are

the results of activities. Many of the resources used in an operation can be traced to individual products

and/or services and identified as direct materials or direct labor costs. Most overhead costs relate only

indirectly to final products and/or services. A costing system identifies costs with activities that consume

resources and assigns resource costs to cost objects—such as products, services, or cost pools based on

activities performed for the cost objects (Blocher et al., 2019).

Stages that are involved in ABC system are explained as follows (Rante, 2016):

• First Stage: Identify the activities. These activities are work performed or undertaken to produce

products such as the number of setups, scheduling, orders, parts, inspections, labor hours, and

design, among others. To identify resource costs for various activities, a firm classifies all activities

according to how the activities consume resources as follows:

o Output unit-level costs. These are the cost of activities performed on each item of

product or service. The cost of activities increases in proportion to the volume of

production or sales. An example of this is the manufacturing operations cost.

o Batch-level costs. These are the costs of activities performed on each group of units of

products or services. The cost of activities increases in proportion to the volume of

production or sales. An example of this is the procurement cost.

o Product-sustaining costs. These are the costs of activities undertaken to support products

or services irrespective of 1the number of units or batches. An example of this involves

marketing costs to launch new products.

o Facility-sustaining costs. These are the costs of activities that cannot be traced to

individual products. They are common to all products, and they support the entire

activities of an organization. An example of this includes general administration costs.

• Second Stage: Pool rates. The overhead cost pool is traced to products using the pool rates. These

activities are used as cost drivers in computing overhead rates. The total factory overhead is then

allocated to activity cost pools. The cost per activity is divided by the activity drivers’ practical

capacity to arrive at the overhead rate per activity.

EXAMPLE: Dragon Plumbing Company has identified activity centers to which overhead costs are assigned.

The following data is available:

Activity Centers Costs Activity Drivers

Utilities P300,000 60,000 machine hours

Scheduling and Setup 273,000 780 set ups

06 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 2 of 5

BM2021

Activity Centers Costs Activity Drivers

1,600,000 pounds of

Material Handling 640,000

materials

The following are the company’s products and other operating statistics:

Product A Product B Product C

Prime costs P80,000 P80,000 P90,000

Machine hours 30,000 10,000 20,000

Number of setups 130 380 270

Pounds of materials 500,000 300,000 800,000

Number of units

40,000 20,000 60,000

produced

Direct labor hours 32,000 18,000 50,000

PROCEDURE:

• Step 1. Determine the pool rates by dividing the given costs to the activity drivers:

Activity Centers Solution Pool rates

Utilities P300,000/60,000 P5/mhr

Scheduling & setup P273,000/780 P350/set up

Materials handling P640,000/1,600,000 P0.40/lb

• Step 2. Determine the overhead cost allocated by multiplying the activity centers by the cost of

activity drivers using the computed pool rates:

Product A Product B Product C TOTAL

Utilities:

A. 30,000 X 5 P150,000

B. 10,000 X 5 P50,000

C. 20,000 X 5 P100,000

P300,000

Scheduling and Setup:

A. 130 X 350 45,500

B. 380 X 350 133,000

C. 270 X 350 94,500

P273,000

Material Handling:

A. 500,000 X .40 200,000

B. 300,000 X .40 120,000

C. 800,000 X .40 320,000

P640,000

TOTAL P395,500 P303,000 P514,500 P1,213,000

06 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 3 of 5

BM2021

Activity-Based Management (Blocher et al., 2019)

Activity-based management (ABM) organizes resources and activities to improve the value of products

and/or services to customers and increase the firm’s competitiveness and profitability. ABM draws on

ABC as its major source of information and focuses on the efficiency and effectiveness of key business

processes and activities. Using ABM, management can identify ways to improve operations, reduce costs,

or increase value to customers, all of which can enhance the firm’s competitiveness.

ABM applications can be classified into two (2) categories:

1. Operational ABM. It enhances operational efficiency, asset utilization, and cost reduction. It is

based on the perspective of doing things right and performing activities more efficiently.

Operational ABM applications use management techniques such as activity analysis, business

process improvement, total quality management, and performance measurement.

2. Strategic ABM. It focuses on choosing appropriate activities for the operation, eliminating non-

essential activities, and selecting the most profitable customers. Strategic ABM applications use

management techniques such as process design and value-chain analysis, all of which can alter

the demand for activities and increase profitability through improved activity efficiency.

Activity Analysis

To be competitive, a firm must assess each of its activities based on product or customer requirements,

efficiency, and value content. Ideally, a firm performs an activity for one (1) of the following reasons:

• It is required to meet the specification of the product and/or service to satisfy customer demands.

• It is required to sustain the organization.

• It is deemed beneficial to the firm.

Examples of activities required to sustain the organization are providing plant security and compliance

with government regulations. Although these activities have no direct effect on the product/service or

customer satisfaction, they cannot be eliminated. Examples of discretionary activities deemed beneficial

to the firm include a holiday party and free coffee. Figure 1 depicts an activity analysis. Some activities,

however, may not adequately meet any of the preceding criteria, making them candidates for elimination.

Figure 1. Example of an activity analysis

Source: Cost management: A strategic emphasis, 2019, p. 149.

06 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 4 of 5

BM2021

Value-Added Analysis

Eliminating activities that add little or no value to customers reduces resource consumption and allows

the firm to focus on activities that increase customer satisfaction. Knowing the values of activities allows

employees to see how work really serves customers and which activities may have little value to the

ultimate customers and should be eliminated or reduced. To ensure that no activities are missed in the

value-added analysis, management may want to prepare a process map. The process map is a diagram

that identifies each step that is currently involved in making a product or providing a service. Development

of the process map should include input from those currently involved in providing the product or service.

The following measures are used in assessing a firm’s activities:

• High-value-added activity. It significantly increases the value of the product or service to the

customers. Removal of a high-value-added activity perceptively decreases the value of the

product or service to the customer. Examples of high-value-added activities are pouring molten

metal into a mold and preparing a field for planting. Anything that involves designing, processing,

and delivering products and services can be classified as high value-added activity. Table 1

illustrates high value-added activities of a television news broadcasting firm. The exhibit also

includes examples of low-value-added activities.

• Low-value-added activity. It consumes time, resources, or space but adds little regarding

satisfying customer needs. If eliminated, customer value or satisfaction decreases imperceptibly

or remains unchanged. Moving parts between processes, waiting time, repairing, and rework are

examples of low-value-added activities. Reduction or elimination of low-value-added activities

reduces cost. Low-value-added activities can be eliminated without affecting the form, fit, or

function of the product or service. These also include activities that are duplicated in another

department or add unnecessary steps to the business process.

High-value-added activity Low-value-added activity

These activities, if eliminated, would affect These activities, if eliminated, would not

the accuracy and effectiveness of the affect the accuracy and effectiveness of the

newscast and decrease total viewers as well newscast. The activity contributes nothing to

as ratings for a specific time slot. the quest for viewer retention and improved

ratings.

• Verification of story sources and acquired • Developing stories not used in a

information newscast

• Efficient electronic journalism to ensure • Assigning more than one (1) person to

effective taped segments develop each facet of the same news

• Newscast story order planned so that story

viewers can follow from one (1) story to • Newscast not completed on time

the next because of one (1) or more inefficient

• Field crew time used to access the best processes

footage possible • Too many employees on a particular shift

• Meaningful news story writing or project

Table 1. Television news broadcasting firm’s activities

Source: Cost management: A strategic emphasis, 2019, p. 150.

References:

Blocher, E., Jurds, D., Smith, S., & Stout D. (2019). Cost management: A strategic emphasis. McGraw-Hill.

Rante, G. A. (2016). Cost accounting. Millenium Books, Inc.

06 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 5 of 5

You might also like

- Anureev Test 2Document46 pagesAnureev Test 2Николай ИлиаевNo ratings yet

- Absorption and Variable CostingDocument22 pagesAbsorption and Variable CostingJamaica David100% (4)

- Absorption and Variable CostingDocument4 pagesAbsorption and Variable Costingj financeNo ratings yet

- Product Costing Methods: Table 1 Shows The Differences Between Product Cost and Period CostDocument5 pagesProduct Costing Methods: Table 1 Shows The Differences Between Product Cost and Period CostMa Trixia Alexandra CuevasNo ratings yet

- MAS.2904 - Variable - Absorption CostingDocument6 pagesMAS.2904 - Variable - Absorption Costingvistalblyss.08No ratings yet

- Study Guide Variable Versus Absorption CostingDocument9 pagesStudy Guide Variable Versus Absorption CostingFlorie May HizoNo ratings yet

- SIM - Variable and Absorption Costing - 0Document5 pagesSIM - Variable and Absorption Costing - 0lilienesieraNo ratings yet

- Chap 007Document10 pagesChap 007Đức LộcNo ratings yet

- M3 Variable Costing As Management ToolDocument6 pagesM3 Variable Costing As Management Toolwingsenigma 00No ratings yet

- Mas 9404 Product CostingDocument11 pagesMas 9404 Product CostingEpfie SanchesNo ratings yet

- Study Guide Variable Versus Absorption CostingDocument8 pagesStudy Guide Variable Versus Absorption CostingFlorie May HizoNo ratings yet

- Variable and Absorption CostingDocument5 pagesVariable and Absorption CostingAllan Jay CabreraNo ratings yet

- Mas-03: Absorption & Variable CostingDocument4 pagesMas-03: Absorption & Variable CostingClint AbenojaNo ratings yet

- 04 Absorption Vs Variable CostingDocument4 pages04 Absorption Vs Variable CostingBanna SplitNo ratings yet

- IWB Chapter 5 - Marginal and Absorption CostingDocument28 pagesIWB Chapter 5 - Marginal and Absorption Costingjulioruiz891No ratings yet

- Marginal & Absorption CostingDocument12 pagesMarginal & Absorption CostingMayal Sheikh100% (1)

- Marginal CostingDocument26 pagesMarginal CostinganshNo ratings yet

- MS 3605 Variable and Absorption CostingDocument5 pagesMS 3605 Variable and Absorption Costingrichshielanghag627No ratings yet

- MS 3405 Variable and Absorption CostingDocument5 pagesMS 3405 Variable and Absorption CostingMonica GarciaNo ratings yet

- 07 Module 03 AVC PDFDocument12 pages07 Module 03 AVC PDFMarriah Izzabelle Suarez RamadaNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Variable Costing As Management Tool-1Document4 pagesModule 3 Variable Costing As Management Tool-1Haika ContiNo ratings yet

- 3MA 03 Absortion and Variable CostingDocument3 pages3MA 03 Absortion and Variable CostingAbigail Regondola BonitaNo ratings yet

- MAS-05 Variable and Absorption CostingDocument8 pagesMAS-05 Variable and Absorption CostingKrizza MaeNo ratings yet

- Cost Two IIDocument65 pagesCost Two IIAbdi Mucee TubeNo ratings yet

- MAS 04 Absorption CostingDocument6 pagesMAS 04 Absorption CostingJoelyn Grace MontajesNo ratings yet

- Marginal Costing TYBAFDocument13 pagesMarginal Costing TYBAFAkash BugadeNo ratings yet

- MS103 SendingDocument3 pagesMS103 SendingEthel Joy Tolentino GamboaNo ratings yet

- Variable CostingDocument2 pagesVariable CostingMutia Novita SariNo ratings yet

- MS Absorption-and-Variable-CostingDocument2 pagesMS Absorption-and-Variable-Costingkalloni.zoeNo ratings yet

- HR Accounting Unit 2Document12 pagesHR Accounting Unit 2Cassidy DonahueNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Product CostingDocument6 pagesChapter 3 - Product Costingchelsea kayle licomes fuentesNo ratings yet

- Variable and Absorption Costing ModuleDocument18 pagesVariable and Absorption Costing ModuleVicNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 AkmenDocument28 pagesChapter 3 AkmenRomi AlfikriNo ratings yet

- Marginal CostingDocument13 pagesMarginal CostingmohitNo ratings yet

- Overview of Absorption and Variable CostingDocument5 pagesOverview of Absorption and Variable CostingJarrelaine SerranoNo ratings yet

- Pre-Study Session 4Document10 pagesPre-Study Session 4Narendralaxman ReddyNo ratings yet

- Notes and Summary in Product Costing With QuizzerDocument12 pagesNotes and Summary in Product Costing With QuizzerCykee Hanna Quizo LumongsodNo ratings yet

- ACT121 - Topic 5Document5 pagesACT121 - Topic 5Juan FrivaldoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10Document5 pagesChapter 10Ailene QuintoNo ratings yet

- (Cpar2017) Mas-8205 (Product Costing) PDFDocument12 pages(Cpar2017) Mas-8205 (Product Costing) PDFSusan Esteban Espartero50% (2)

- Mas 1.2.4 Assessment For-PostingDocument5 pagesMas 1.2.4 Assessment For-PostingJustine CruzNo ratings yet

- Module 4 Absorption and Variable Costing NotesDocument3 pagesModule 4 Absorption and Variable Costing NotesMadielyn Santarin Miranda100% (3)

- Marginal CostingDocument42 pagesMarginal CostingAbdifatah SaidNo ratings yet

- MAS Absorption Costing/Variable Costing Study ObjectivesDocument6 pagesMAS Absorption Costing/Variable Costing Study ObjectivesMarjorie ManuelNo ratings yet

- Bilu Chap 3Document16 pagesBilu Chap 3borena extensionNo ratings yet

- Mas 2605Document6 pagesMas 2605John Philip CastroNo ratings yet

- Marginal Costing & Decision MakingDocument8 pagesMarginal Costing & Decision MakingPraneeth KNo ratings yet

- Team Work Makes The Dream Work Acctg15 Var. Absorption CostingDocument4 pagesTeam Work Makes The Dream Work Acctg15 Var. Absorption Costinggeorgia cerezoNo ratings yet

- CMA-II-Chapter 1Document20 pagesCMA-II-Chapter 1Yared BitewNo ratings yet

- CMA II CH 1Document22 pagesCMA II CH 1Yared BitewNo ratings yet

- Variable Costing: A Tool For ManagementDocument9 pagesVariable Costing: A Tool For ManagementNica JeonNo ratings yet

- Absorption Vs VariableDocument10 pagesAbsorption Vs VariableRonie Macasabuang CardosaNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER FOUR Cost and MGMT ACCTDocument12 pagesCHAPTER FOUR Cost and MGMT ACCTFeleke TerefeNo ratings yet

- Ringkasan Materi - Akuntansi ManajemenDocument7 pagesRingkasan Materi - Akuntansi ManajemenFahmi Nur AlfiyanNo ratings yet

- Costing NotesDocument48 pagesCosting NotesOckouri BarnesNo ratings yet

- 03 MAS - Var. & Absorption CostingDocument6 pages03 MAS - Var. & Absorption CostingManwol JangNo ratings yet

- Absorption and Variable Costing: Strategic Cost ManagementDocument3 pagesAbsorption and Variable Costing: Strategic Cost ManagementMarites AmorsoloNo ratings yet

- Activity - Based - Costing F5 NotesDocument13 pagesActivity - Based - Costing F5 NotesSiddiqua KashifNo ratings yet

- SCM Unit 4 Variable and Absorption CostingDocument9 pagesSCM Unit 4 Variable and Absorption CostingMargie Garcia LausaNo ratings yet

- Management Accounting: Decision-Making by Numbers: Business Strategy & Competitive AdvantageFrom EverandManagement Accounting: Decision-Making by Numbers: Business Strategy & Competitive AdvantageRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Management Accounting Strategy Study Resource for CIMA Students: CIMA Study ResourcesFrom EverandManagement Accounting Strategy Study Resource for CIMA Students: CIMA Study ResourcesNo ratings yet

- The Pizza Food Truck - SolutionDocument13 pagesThe Pizza Food Truck - SolutionsukhvindertaakNo ratings yet

- The Cost of Goods Sold For The Month of December: Excel Professional Services, IncDocument4 pagesThe Cost of Goods Sold For The Month of December: Excel Professional Services, IncmatildaNo ratings yet

- 2021 11 05 Midterms DEPTALSDocument3 pages2021 11 05 Midterms DEPTALSeveNo ratings yet

- Far - 03: Inventories: Financial Accounting & ReportingDocument10 pagesFar - 03: Inventories: Financial Accounting & ReportingLorenzo LapuzNo ratings yet

- 9706 m17 Ms 22Document11 pages9706 m17 Ms 22FarrukhsgNo ratings yet

- Standard CostingDocument17 pagesStandard CostingRoldan Hiano ManganipNo ratings yet

- Accounting For Rebates and Vendor - Customer Incentives - FinalDocument6 pagesAccounting For Rebates and Vendor - Customer Incentives - FinalEunice WongNo ratings yet

- Segment ReportingDocument10 pagesSegment ReportingmonneNo ratings yet

- Past Paper NSODocument18 pagesPast Paper NSORana AwaisNo ratings yet

- SMCH 13Document47 pagesSMCH 13Lara Lewis AchillesNo ratings yet

- 7 Variable Absorption CostingDocument37 pages7 Variable Absorption CostingBəhmən OrucovNo ratings yet

- Kuala Lumpur: Answer Sheets: GBHDHFH: 23525: ABMC2054 Cost & Management Accounting IDocument30 pagesKuala Lumpur: Answer Sheets: GBHDHFH: 23525: ABMC2054 Cost & Management Accounting IJUN XIANG NGNo ratings yet

- Financial Accounting Reviewer - Chapter 58Document13 pagesFinancial Accounting Reviewer - Chapter 58Coursehero PremiumNo ratings yet

- Fabm 4 PDFDocument2 pagesFabm 4 PDFgk concepcionNo ratings yet

- Castor OilDocument17 pagesCastor OilsamsonNo ratings yet

- 2018 Za (Q + Ma) Ac1025Document95 pages2018 Za (Q + Ma) Ac1025전민건No ratings yet

- Mcom Part 1 Sem 2 Cost Acc Operating CostingDocument41 pagesMcom Part 1 Sem 2 Cost Acc Operating Costingjui100% (2)

- Prathi Project CapexDocument100 pagesPrathi Project CapexJennifer Joseph0% (1)

- BAC 201 - MGT ACC Select TopicsDocument43 pagesBAC 201 - MGT ACC Select TopicsRebeccah NdungiNo ratings yet

- Cost Accounting #2 PDFDocument3 pagesCost Accounting #2 PDFSYED ABDUL HASEEB SYED MUZZAMIL NAJEEB 13853No ratings yet

- Accounting Hawk - MADocument21 pagesAccounting Hawk - MAClaire BarbaNo ratings yet

- Budgeting and Profit Planning CR PDFDocument24 pagesBudgeting and Profit Planning CR PDFLindcelle Jane DalopeNo ratings yet

- Cfas ReviewerDocument10 pagesCfas ReviewershaylieeeNo ratings yet

- Activity Sheet Entrep 2nd - QuarterDocument11 pagesActivity Sheet Entrep 2nd - QuarterDenilyn PalaypayNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 Conversion Processes and ControlsDocument5 pagesChapter 11 Conversion Processes and ControlsPunita DoleNo ratings yet

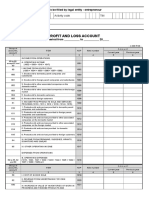

- Enterprises - Profit and Loss Account13042016Document4 pagesEnterprises - Profit and Loss Account13042016jelachajelenaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14 HomeworkDocument22 pagesChapter 14 HomeworkCody IrelanNo ratings yet

- Jawaban Mojakoe-UTS Akuntansi Keuangan 1 Ganjil 2020-2021Document22 pagesJawaban Mojakoe-UTS Akuntansi Keuangan 1 Ganjil 2020-2021Vincenttio le CloudNo ratings yet

- Hilton CH 2 Select SolutionsDocument12 pagesHilton CH 2 Select SolutionsUmair AliNo ratings yet