Professional Documents

Culture Documents

TB, Review, Patho

TB, Review, Patho

Uploaded by

Krizzia Laturnas0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views4 pagesThe document discusses the theoretical background and pathophysiology of acute glomerulonephritis (AGN). It states that AGN is common in childhood and can often be managed in primary care by checking the complement C3 level and urine tests. It also describes potential complications that require specialist referral. The pathophysiology section explains that AGN is an immune-mediated condition where antibodies attack antigens in the glomerular basement membrane, activating the complement system and causing inflammation. This leads to structural changes like cellular proliferation and thickening of the basement membrane, as well as functional changes like proteinuria and reduced kidney function.

Original Description:

Pathophysiology of acute Glomerulonephritis

Original Title

Tb, Review, Patho

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document discusses the theoretical background and pathophysiology of acute glomerulonephritis (AGN). It states that AGN is common in childhood and can often be managed in primary care by checking the complement C3 level and urine tests. It also describes potential complications that require specialist referral. The pathophysiology section explains that AGN is an immune-mediated condition where antibodies attack antigens in the glomerular basement membrane, activating the complement system and causing inflammation. This leads to structural changes like cellular proliferation and thickening of the basement membrane, as well as functional changes like proteinuria and reduced kidney function.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views4 pagesTB, Review, Patho

TB, Review, Patho

Uploaded by

Krizzia LaturnasThe document discusses the theoretical background and pathophysiology of acute glomerulonephritis (AGN). It states that AGN is common in childhood and can often be managed in primary care by checking the complement C3 level and urine tests. It also describes potential complications that require specialist referral. The pathophysiology section explains that AGN is an immune-mediated condition where antibodies attack antigens in the glomerular basement membrane, activating the complement system and causing inflammation. This leads to structural changes like cellular proliferation and thickening of the basement membrane, as well as functional changes like proteinuria and reduced kidney function.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 4

Theoretical Background

According to Thomas R. Welch (2011) Acute glomerulonephritis (AGN) is a

common condition in childhood. Many children with AGN can be managed in the

primary care setting. The diagnosis is usually made on the basis of urinary findings,

especially the presence of red blood cell casts. One of the most important initial

investigations is determining the complement C3 level; hypocomplementemia is most

characteristic of post streptococcal AGN, while normocomplementemia is most often

seen with IgA nephropathy. Children whose AGN is accompanied by significant

hypertension or renal insufficiency should be assessed by a specialist immediately.

The presence of serious extrarenal signs or symptoms also merits urgent

referral. Otherwise, serial follow-up in the primary care office is appropriate. Particular

attention should be paid to rash, joint discomfort, recent weight change, fatigue, appetite

changes, respiratory complaints, and recent medication exposure.

Proteinuria is also nearly invariant in AGN although any cause of gross

hematuria can lead to some urinary protein. If the urine is not grossly bloody, however,

the combined presence of hematuria and proteinuria virtually always means

glomerulonephritis.

The chronic form may develop silently (without symptoms) over several years. It

often leads to complete kidney failure. Early signs and symptoms of the chronic form

may include:

Blood or protein in the urine (hematuria, proteinuria)

High blood pressure

Swelling of your ankles or face (edema)

Frequent nighttime urination

Very bubbly or foamy urine

Symptoms of kidney failure include:

Lack of appetite

Nausea and vomiting

Tiredness

Difficulty sleeping

Dry and itchy skin Nighttime muscle cramps

It is next important to ascertain any symptoms suggestive of complications of the

AGN. These might include shortness of breath or exercise intolerance from fluid

overload or headaches, visual disturbances, or alteration in mental status from

hypertension.

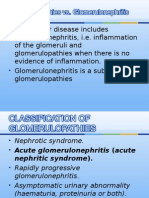

Pathophysiology of Acute Glomerulonephritis

The underlying pathogenetic mechanism common to all of these different varieties of

glomerulonephritis (GN) is immune-mediated, in which both humoral as well as cell-

mediated pathways are active. The consequent inflammatory response, in many cases,

paves the way for fibrotic events that follow.

The targets of immune-mediated damage vary according to the type of GN. For

instance, glomerulonephritis associated with staphylococcus shows deposits of IgA and

C3 complement.

One of the targets is the glomerular basement membrane itself or some antigen trapped

within it, as in post-streptococcal disease. Such antigen-antibody reactions can be

systemic with glomerulonephritis occurring as one of the components of the disease

process, such as in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or IgA nephropathy. On the

other hand, in small vessel vasculitis; instead of antigen-antibody reaction, cell-

mediated immune reactions are the main culprit. Here, T lymphocytes and

macrophages flood the glomeruli with resultant damage.

These initiating events lead to the activation of common inflammatory pathways, i.e., the

complement system and coagulation cascade. The generation of pro-inflammatory

cytokines and complement products, in turn, results in the proliferation of glomerular

cells.

Cytokines such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) are also released, ultimately

causing glomerulosclerosis. This event is seen in those situations where the antigen is

present for longer periods of time, for example, in hepatitis C viral infection.

When the antigen is rapidly cleared as in post-streptococcal GN, the resolution of

inflammation is more likely.

Structural Changes

Structurally, cellular proliferation causes an increase in the cellularity of the glomerular

tuft due to the excess of endothelial, mesangial, and epithelial cells. The proliferation

may be of two types:

Endocapillary - within the glomerular capillary tufts

Extracapillary - in the Bowman space including the epithelial cells

In extracapillary proliferation, parietal epithelial cells proliferate to cause the formation of

crescents which is characteristic of some forms of rapidly

progressive glomerulonephritis.

Thickening of glomerular basement membrane appears as thickened capillary walls on

light microscopy. However, on electron microscopy, this may look like a consequence of

thickening of basement membrane proper, for instance, diabetes or electron-dense

deposits either on the epithelial or endothelial side of the basement membrane. There

can be various types of electron-dense deposits, corresponding to an area of immune

complex deposition, such as subendothelial, subepithelial, intramembranous, and

mesangial.

Features of irreversible injury include hyalinization or sclerosis that can be focal, diffuse,

segmental, or global.

Functional Changes Functional changes include the following:

Proteinuria

Hematuria

Reduction in creatinine clearance, oliguria, or anuria

Active urine sediments, such as RBCs and RBC casts

This leads to intravascular volume expansion, edema, and systemic hypertension.

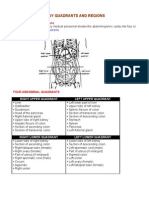

Review of Anatomy and Physiology of a Nephron

The nephron consist of a tubule closed at one end, to form the cup-shaped

glomerular capsule (Bowman’s Capsule), which almost completely enclose a network of

tiny arterial capillaries, the glomerulus. Continuing from the glomerulus capsule, the

remainder of the nephron is about 3 cm long and is described in three parts:

o The proximal convoluted tubule

o Loop of Henle (medullary loop)

o Distal convoluted tubule lead them to collecting duct

You might also like

- Freebie Bundle-50 PagesDocument75 pagesFreebie Bundle-50 PagesKarla Seravalli86% (7)

- Research ProposalDocument5 pagesResearch ProposalAishwarya Bharath100% (2)

- ACLS Manual Provider 2016Document207 pagesACLS Manual Provider 2016AhmedShareef100% (9)

- Organs in The Body Quadrants and RegionsDocument3 pagesOrgans in The Body Quadrants and RegionsDavid HosamNo ratings yet

- Glomerulonephritis-1 (Dr. Soffa)Document58 pagesGlomerulonephritis-1 (Dr. Soffa)Rahmailla Khanza Diana FebriliantriNo ratings yet

- Robinson Pathology Chapter 20 KidneyDocument11 pagesRobinson Pathology Chapter 20 KidneyElina Drits100% (1)

- Journal OPDDocument18 pagesJournal OPDKate WeyganNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 Renal DiseaseDocument13 pagesChapter 8 Renal DiseaseAlanah JaneNo ratings yet

- AUBF Group 1 Chapter 8Document12 pagesAUBF Group 1 Chapter 8Gerald John PazNo ratings yet

- Glomerulonephritis: Lecturer Prof. Yu.R. KovalevDocument39 pagesGlomerulonephritis: Lecturer Prof. Yu.R. Kovalevalfaz lakhani100% (1)

- Screenshot 2022-12-05 at 15.41.06Document122 pagesScreenshot 2022-12-05 at 15.41.06Senuri ManthripalaNo ratings yet

- What Is Glomerulonephritis?Document7 pagesWhat Is Glomerulonephritis?SSNo ratings yet

- Postgrad Med J 2003 Vinen 206 13Document9 pagesPostgrad Med J 2003 Vinen 206 13Raka ArifirmandaNo ratings yet

- Acute Glomerulonephritis (AGN) OverviewDocument8 pagesAcute Glomerulonephritis (AGN) OverviewRalph Wwarren ReyesNo ratings yet

- Glomerular DsDocument18 pagesGlomerular Dsnathan asfahaNo ratings yet

- Glomerular DiseasesDocument31 pagesGlomerular DiseasesLALITH SAI KNo ratings yet

- NEPHRITISDocument37 pagesNEPHRITISJay RathvaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 4 (1of3) - Nephritic SyndromeDocument45 pagesLecture 4 (1of3) - Nephritic SyndromeAliye BaramNo ratings yet

- What Is Acute Glomerulonephritis?: Acute Glomerulonephritis (GN) Comprises A Specific Set of Renal Diseases inDocument6 pagesWhat Is Acute Glomerulonephritis?: Acute Glomerulonephritis (GN) Comprises A Specific Set of Renal Diseases inAnnapoorna SHNo ratings yet

- Nephritic SyndromeDocument24 pagesNephritic SyndromeMuhamed Al Rohani100% (2)

- 10 Primary Glumerulopathies III - GKDocument2 pages10 Primary Glumerulopathies III - GKGerarld Immanuel KairupanNo ratings yet

- ACUTE GLOMERULONEPHRITIS Refers To A Specific Set of Renal Diseases in Which An ImmunologicDocument3 pagesACUTE GLOMERULONEPHRITIS Refers To A Specific Set of Renal Diseases in Which An ImmunologicAdrian MallarNo ratings yet

- Nephritic Syndrome - Armando HasudunganDocument14 pagesNephritic Syndrome - Armando HasudunganzahraaNo ratings yet

- Causes of Acute GlomerulonephritisDocument8 pagesCauses of Acute GlomerulonephritisShielah YacubNo ratings yet

- Acute Glomerulonephritis: Background, Pathophysiology, EtiologyDocument5 pagesAcute Glomerulonephritis: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology'Riku' Pratiwie TunaNo ratings yet

- Isolated Glomerular Disease With Recurrent Gross HematuriaDocument17 pagesIsolated Glomerular Disease With Recurrent Gross HematuriaArun GeorgeNo ratings yet

- GLOMERULONEPHRITIS (Bright's Disease)Document8 pagesGLOMERULONEPHRITIS (Bright's Disease)Anjitha K. JNo ratings yet

- Secundary Glomerular LesionsDocument2 pagesSecundary Glomerular LesionsGlogogeanu Cristina AndreeaNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic SyndromeDocument1 pageNephrotic Syndromedhruv kumarNo ratings yet

- GlomerulonephritisDocument59 pagesGlomerulonephritistressNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic SyndromeDocument65 pagesNephrotic SyndromemejulNo ratings yet

- GlomerulonephritisDocument35 pagesGlomerulonephritisapi-19916399No ratings yet

- Rapidly Progressive GlomerulonephritisDocument17 pagesRapidly Progressive GlomerulonephritisEasyOrientDNo ratings yet

- Renal Diseases IDocument17 pagesRenal Diseases IPoojaNo ratings yet

- Acute GlomerulonephritisDocument4 pagesAcute GlomerulonephritisJulliza Joy PandiNo ratings yet

- 3&4 Glomerular Diseases and Nephrotic SyndromeDocument46 pages3&4 Glomerular Diseases and Nephrotic SyndromeTor Koang ThorNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic SyndDocument21 pagesNephrotic Synd238439904No ratings yet

- Primary Glomerulonephritis UG LectureDocument50 pagesPrimary Glomerulonephritis UG LectureMalik Mohammad AzharuddinNo ratings yet

- MANUSCRIPTDocument11 pagesMANUSCRIPTANA DelafuenteNo ratings yet

- Acute: Poststreptococca L Glomerulonephri TisDocument28 pagesAcute: Poststreptococca L Glomerulonephri TisLeroy Christy LawalataNo ratings yet

- Review Article: An Approach To The Child With Acute GlomerulonephritisDocument4 pagesReview Article: An Approach To The Child With Acute GlomerulonephritisLu Jordy LuhurNo ratings yet

- Enfermedad GlomerularDocument23 pagesEnfermedad GlomerularAlejandro beuses morrNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic Vs Nephritic SyndromeDocument80 pagesNephrotic Vs Nephritic Syndromevan016_bunnyNo ratings yet

- Lecture Note On Renal Diseases For Medical Students - GNDocument10 pagesLecture Note On Renal Diseases For Medical Students - GNEsayas KebedeNo ratings yet

- Acute Glomerulonephriti S: Group 3Document25 pagesAcute Glomerulonephriti S: Group 3AradhanaRamchandaniNo ratings yet

- AUBF Lec Week#8 Renal DiseasesDocument10 pagesAUBF Lec Week#8 Renal DiseasesLexaNatalieConcepcionJuntadoNo ratings yet

- GlomerulonephritisDocument58 pagesGlomerulonephritisJosa Anggi Pratama0% (1)

- AUBF Renal DiseasesDocument3 pagesAUBF Renal DiseasesAngela LaglivaNo ratings yet

- 14 Kidney Diseases PDFDocument128 pages14 Kidney Diseases PDFMayur WakchaureNo ratings yet

- Glomer Ds TadDocument190 pagesGlomer Ds TadHaileprince MekonnenNo ratings yet

- Glomerulonephritis: Nameesha Natasha Naidu 20130105Document26 pagesGlomerulonephritis: Nameesha Natasha Naidu 20130105AliMalikNo ratings yet

- C C C C: CC CC CCCC CC CCC CC C CCCC CC CCC C CC C CCCCC CCC CC C C CCCC CDocument1 pageC C C C: CC CC CCCC CC CCC CC C CCCC CC CCC C CC C CCCCC CCC CC C C CCCC CGabriel Rosales RM RNNo ratings yet

- Acute Glomerulonephritis (AGN)Document5 pagesAcute Glomerulonephritis (AGN)smashayielNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic Syndrome in Children-LectureDocument52 pagesNephrotic Syndrome in Children-LectureLubinda SitaliNo ratings yet

- 2 Glomerular DiseasesDocument48 pages2 Glomerular DiseasesDammaqsaa W BiyyanaaNo ratings yet

- Glomerular Disease - Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis in Adults - UpToDateDocument23 pagesGlomerular Disease - Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis in Adults - UpToDateRaiya MallickNo ratings yet

- Glomerulonefritis Menbrano Prol N Engl J Med 2012Document13 pagesGlomerulonefritis Menbrano Prol N Engl J Med 2012Francisco Rebollar GarduñoNo ratings yet

- Acute GlomerulonephritisDocument28 pagesAcute GlomerulonephritisPaul SinsNo ratings yet

- Agn PDFDocument6 pagesAgn PDFMohamed ZiadaNo ratings yet

- Gus156 Slide Ginjal Dan Saluran KemihDocument128 pagesGus156 Slide Ginjal Dan Saluran KemihRina ChairunnisaNo ratings yet

- Seminar On Nephrotic Syndrome: Medical Surgical NursingDocument15 pagesSeminar On Nephrotic Syndrome: Medical Surgical NursingGargi MP100% (1)

- Comprehensive Insights into AA Amyloidosis: Understanding, Managing, and ThrivingFrom EverandComprehensive Insights into AA Amyloidosis: Understanding, Managing, and ThrivingNo ratings yet

- Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency SyndromeDocument25 pagesLeukocyte Adhesion Deficiency SyndromeperioassNo ratings yet

- ATCM JOURNAL September 2014 - 21Document60 pagesATCM JOURNAL September 2014 - 21Ivonne Flores FernándezNo ratings yet

- Brain DominanceDocument33 pagesBrain DominanceAndreea Ilie100% (1)

- Bioenergetics, Biological Oxidation and The Respiration Chain Bioenergetics and ATPDocument43 pagesBioenergetics, Biological Oxidation and The Respiration Chain Bioenergetics and ATPEmenintaNo ratings yet

- MHMC EquipmentsDocument2 pagesMHMC EquipmentsMarvinNo ratings yet

- Medical Complications of Type 2 DiabetesDocument422 pagesMedical Complications of Type 2 DiabetesMayracpp.16No ratings yet

- Drug Study: Phinma University of PangasinanDocument1 pageDrug Study: Phinma University of PangasinanVoid LessNo ratings yet

- Care NewbornDocument38 pagesCare NewbornRaja0% (1)

- Bee Stings Immunology Allergy and Treatment Marterre PDFDocument9 pagesBee Stings Immunology Allergy and Treatment Marterre PDFOktaviana Sari DewiNo ratings yet

- Lattice Corneal DystrophyDocument7 pagesLattice Corneal DystrophyPhilip McNelsonNo ratings yet

- Thyroid Gland Clinical Chemistry 2 (Laboratory) : LessonDocument4 pagesThyroid Gland Clinical Chemistry 2 (Laboratory) : LessonCherry Ann ColechaNo ratings yet

- Animal BehaviourDocument5 pagesAnimal BehaviourthinaNo ratings yet

- Revisi AnestesiDocument1 pageRevisi AnestesiWelmi Sulfatri IshakNo ratings yet

- Adrenergic Agonists and AntagonistsDocument9 pagesAdrenergic Agonists and Antagonistsstephanienwafor18No ratings yet

- Botanical Actions Reference Sheet: Botanical Action Description Physiology ExamplesDocument2 pagesBotanical Actions Reference Sheet: Botanical Action Description Physiology ExamplesDeo DoktorNo ratings yet

- Neuroanatomy Quiz BeeDocument55 pagesNeuroanatomy Quiz BeeJulienne Sanchez-Salazar100% (3)

- Fi ADocument67 pagesFi AalfonsoNo ratings yet

- Ren 10Document1 pageRen 10ray72roNo ratings yet

- THT RhinosinusitisDocument8 pagesTHT RhinosinusitismeiliaNo ratings yet

- BiochemistryDocument21 pagesBiochemistryS V S VardhanNo ratings yet

- Neuronal Integration and CurcuitsDocument5 pagesNeuronal Integration and CurcuitsOdyNo ratings yet

- AMES TestDocument11 pagesAMES TestJarena Ria ZolinaNo ratings yet

- Congenital Hydrocephalus: Case PresentationDocument35 pagesCongenital Hydrocephalus: Case PresentationIan Mizzel A. Dulfina100% (1)

- What Process Is Best Seen Using A Perpendicular CR With The Elbow in Acute Flexion and With The Posterior Aspect of The Humerus Adjacent To The Image ReceptorDocument22 pagesWhat Process Is Best Seen Using A Perpendicular CR With The Elbow in Acute Flexion and With The Posterior Aspect of The Humerus Adjacent To The Image ReceptorKalpana ParajuliNo ratings yet

- Summary Adaptations How Animals Survive UploadDocument26 pagesSummary Adaptations How Animals Survive UploadLearnRoots100% (1)

- Drug Study NCP SoapieDocument15 pagesDrug Study NCP Soapiemikrobyo_ng_wmsuNo ratings yet