Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fungo Propolis

Fungo Propolis

Uploaded by

Suelen Santos da SilvaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Chap 14Document39 pagesChap 14Koby100% (4)

- Orsi 2005Document10 pagesOrsi 2005vahidNo ratings yet

- CARDOSO Et Al 2010 - Propolis Staphylo e Malassezia - Otite CaninaDocument3 pagesCARDOSO Et Al 2010 - Propolis Staphylo e Malassezia - Otite CaninaDébora SakiyamaNo ratings yet

- Galleria Mellonella As An in Vivo Model For Assessing The Protective Activity of Probiotics Against Gastrointestinal Bacterial PathogensDocument6 pagesGalleria Mellonella As An in Vivo Model For Assessing The Protective Activity of Probiotics Against Gastrointestinal Bacterial PathogensJosXe CalderonNo ratings yet

- In Vitro Multiplication of Eucalyptus Hybrid Via: Temporary Immersion Bioreactor: Culture Media and Cytokinin EffectsDocument8 pagesIn Vitro Multiplication of Eucalyptus Hybrid Via: Temporary Immersion Bioreactor: Culture Media and Cytokinin EffectsFenny OctavianiNo ratings yet

- 3 PDFDocument3 pages3 PDFGeraldineMoletaGabutinNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Giving Trigona Honey and HDocument4 pagesThe Effect of Giving Trigona Honey and HNurul Muqarribah Pratiwi IshaqNo ratings yet

- Bioefficacy of Mosquito Mat Vaporizers and Associated Metabolic DetoxicationDocument11 pagesBioefficacy of Mosquito Mat Vaporizers and Associated Metabolic DetoxicationNg Kin HoongNo ratings yet

- A Study of The Larvicidal and Molluscicidal Activities of Some Medicinal Plants From Northeast BrazilDocument8 pagesA Study of The Larvicidal and Molluscicidal Activities of Some Medicinal Plants From Northeast BrazilJosé Teófilo Moreira FilhoNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial Activity Test of Medicinal Plant Extract Using Antimicrobial Disc and Filter PaperDocument9 pagesAntimicrobial Activity Test of Medicinal Plant Extract Using Antimicrobial Disc and Filter PaperGinnyNo ratings yet

- Activity 2 - Antifungal StudyDocument6 pagesActivity 2 - Antifungal StudyDuke TenchavezNo ratings yet

- Fungo Endofitico T. Granulosa - QuaresmeiraDocument13 pagesFungo Endofitico T. Granulosa - Quaresmeiratata.andrade.profNo ratings yet

- Geopropolis Mandaguari PretaDocument11 pagesGeopropolis Mandaguari PretaJonas GarciaNo ratings yet

- Fração Biomassa Ostreatus Sarcoma 2017Document8 pagesFração Biomassa Ostreatus Sarcoma 2017Edward Marques de SouzaNo ratings yet

- Solid State Fermentation of Jatropha Curcas Kernel Cake With Cocktail of FungiDocument8 pagesSolid State Fermentation of Jatropha Curcas Kernel Cake With Cocktail of FungiAnowar RazvyNo ratings yet

- Liu, 2013Document10 pagesLiu, 2013abudiharjo73No ratings yet

- tmp73EA TMPDocument15 pagestmp73EA TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Propolis in The Control of Helminths in Sheep - IJAAR-Vol-14-No-6-p-69-74Document6 pagesPropolis in The Control of Helminths in Sheep - IJAAR-Vol-14-No-6-p-69-74International Network For Natural SciencesNo ratings yet

- 394 668 1 SMDocument8 pages394 668 1 SMRizka Amanda FauziaNo ratings yet

- Template JRBA Rev 2Document13 pagesTemplate JRBA Rev 2FRISKA CHRISTININGRUMNo ratings yet

- Araujo Etal 2005 WJ MBDocument7 pagesAraujo Etal 2005 WJ MBFabiolaNo ratings yet

- Ovad 045Document8 pagesOvad 045phong nguyễnNo ratings yet

- Cartagena Filamentus FungusDocument17 pagesCartagena Filamentus FungusLorena Sosa LunaNo ratings yet

- Artigo RubensDocument8 pagesArtigo RubensbuissaNo ratings yet

- 2018 Satish PoojariDocument4 pages2018 Satish PoojariDr Estari MamidalaNo ratings yet

- Effective Control of Black Sigatoka DiseDocument8 pagesEffective Control of Black Sigatoka DiseIsrael Kelly AntolinNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Production of Antifungal Metabolites Against MutagenesisDocument9 pagesEvaluation of The Production of Antifungal Metabolites Against MutagenesisDũng NguyễnNo ratings yet

- 5QBJ - 1472-6882-11-108-p - GEOPROPOLISDocument10 pages5QBJ - 1472-6882-11-108-p - GEOPROPOLISAnonymous OdfoTPUNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Ahmad Rafdi Wiharja 081211433013Document22 pagesJurnal Ahmad Rafdi Wiharja 081211433013titanNo ratings yet

- Jurnal - Efek Imunostimulator Propolis TerhadapDocument7 pagesJurnal - Efek Imunostimulator Propolis TerhadapArifin I. OputuNo ratings yet

- Antiviral Effects of Brazilian Green and RedDocument10 pagesAntiviral Effects of Brazilian Green and RedDebora PereiraNo ratings yet

- Floram 27 2 E20170718Document6 pagesFloram 27 2 E20170718Tatiany NóbregaNo ratings yet

- Pathogenicity of Epicoccum Sorghinum Towards Dragon FruitsDocument8 pagesPathogenicity of Epicoccum Sorghinum Towards Dragon FruitsJuan PachecoNo ratings yet

- Theobroma Cacao PhytophthoraDocument10 pagesTheobroma Cacao PhytophthoraOpenaccess Research paperNo ratings yet

- Pseudomonas Alcaligenes, Potential Antagonist Against Fusarium Oxysporum F.SP - Lycopersicum The Cause of Fusarium Wilt Disease On TomatoDocument8 pagesPseudomonas Alcaligenes, Potential Antagonist Against Fusarium Oxysporum F.SP - Lycopersicum The Cause of Fusarium Wilt Disease On TomatoAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Armando Et Al 2011Document10 pagesArmando Et Al 2011Adrian Melgratti JobsonNo ratings yet

- Da Silva 2013 - ECAM - Brazilian Propolis Antileishmanial and Immunomodulatory EffectsDocument8 pagesDa Silva 2013 - ECAM - Brazilian Propolis Antileishmanial and Immunomodulatory EffectsmilenamiNo ratings yet

- Biological Activities of The Fermentation Extract of The Endophytic Fungus Alternaria Alternata Isolated From Coffea Arabica LDocument13 pagesBiological Activities of The Fermentation Extract of The Endophytic Fungus Alternaria Alternata Isolated From Coffea Arabica LCece MarzamanNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2667011923000282 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S2667011923000282 MainJoao Sousa RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Acaricidal Activity of Extracts From Different Structures of Piper Tuberculatum Against Larvae and Adults of Rhipicephalus MicroplusDocument6 pagesAcaricidal Activity of Extracts From Different Structures of Piper Tuberculatum Against Larvae and Adults of Rhipicephalus MicroplusLaura Estefania Niño MNo ratings yet

- Bot513 03Document8 pagesBot513 03Ponechor HomeNo ratings yet

- Palmivora (Butler) Butler Penyebab Penyakit Busuk BuahDocument11 pagesPalmivora (Butler) Butler Penyebab Penyakit Busuk BuahRyan Afriandi SiregarNo ratings yet

- Phytochemical Characterization of Pumpkin Seed WithDocument8 pagesPhytochemical Characterization of Pumpkin Seed WithLarisa CatautaNo ratings yet

- Molluscicidal and Ovicidal Activities of Plant Extracts 2011Document8 pagesMolluscicidal and Ovicidal Activities of Plant Extracts 2011Juan Enrique Tacoronte MoralesNo ratings yet

- Vieira Etal 2017Document8 pagesVieira Etal 2017Manuel ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Microbiological assessment of fresh, minimally processed vegetables from open air markets and supermarkets in Luzon, Philippines, for food safetyDocument10 pagesMicrobiological assessment of fresh, minimally processed vegetables from open air markets and supermarkets in Luzon, Philippines, for food safetyiyaNo ratings yet

- IOSRPHRDocument3 pagesIOSRPHRIOSR Journal of PharmacyNo ratings yet

- Immunity To Plasmodium KnowlesiDocument6 pagesImmunity To Plasmodium KnowlesimustrechNo ratings yet

- Effect of 2,4-D, Hydric Stress and Light On Indica Rice (Oryza Sativa) Somatic EmbryogenesisDocument8 pagesEffect of 2,4-D, Hydric Stress and Light On Indica Rice (Oryza Sativa) Somatic EmbryogenesisGaurav ChandrakantNo ratings yet

- Baert, Samapundo 2007Document12 pagesBaert, Samapundo 2007Jerusalen BetancourtNo ratings yet

- In Vitro Anthelmintic Activity of The Crude Hydroalcoholic Extract of PiperDocument6 pagesIn Vitro Anthelmintic Activity of The Crude Hydroalcoholic Extract of PiperMarcial Fuentes EstradaNo ratings yet

- An Efficient Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation Protocol For Black Pepper (Piper Nigrum L.) Using Embryogenic Mass As ExplantDocument8 pagesAn Efficient Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation Protocol For Black Pepper (Piper Nigrum L.) Using Embryogenic Mass As ExplantIman Fadhul HadiNo ratings yet

- Food Research InternationalDocument9 pagesFood Research InternationalNaticita Rincon MacoteNo ratings yet

- tmp42AA TMPDocument8 pagestmp42AA TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Giving Trigona Honey and Honey Propolis Trigona To The mRNA Foxp3 Expression in Mice Balb/c Strain Induced by Salmonella TyphiDocument45 pagesThe Effect of Giving Trigona Honey and Honey Propolis Trigona To The mRNA Foxp3 Expression in Mice Balb/c Strain Induced by Salmonella TyphiNisfi Laelah GirltsaniieNo ratings yet

- Antifungal Activity of GuavaDocument11 pagesAntifungal Activity of GuavaFarij AbdurrohmanNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial Activity of Nigella Sativa Seed ExtractDocument5 pagesAntimicrobial Activity of Nigella Sativa Seed ExtractDian Takwa HarahapNo ratings yet

- Antibact AssayDocument7 pagesAntibact Assaymakerk82No ratings yet

- BR - PLG MiceDocument8 pagesBR - PLG Miceyogi75No ratings yet

- Plant-derived Pharmaceuticals: Principles and Applications for Developing CountriesFrom EverandPlant-derived Pharmaceuticals: Principles and Applications for Developing CountriesNo ratings yet

- Microbial Plant Pathogens: Detection and Management in Seeds and PropagulesFrom EverandMicrobial Plant Pathogens: Detection and Management in Seeds and PropagulesNo ratings yet

- 6 Helpful Ways To Boost Immune HealthDocument6 pages6 Helpful Ways To Boost Immune HealthDennis Noel BejerNo ratings yet

- Imse LectureDocument19 pagesImse LectureJOWELA RUBY EUSEBIONo ratings yet

- Tyrosine Kinase Receptors in Oncology: Molecular SciencesDocument48 pagesTyrosine Kinase Receptors in Oncology: Molecular SciencesAnuradha Monga KapoorNo ratings yet

- Immunology Overview: Armond S. Goldman Bellur S. PrabhakarDocument45 pagesImmunology Overview: Armond S. Goldman Bellur S. PrabhakarIoana AsziaNo ratings yet

- Immunology KubyDocument24 pagesImmunology KubySayanta Bera100% (1)

- Prelim HPCTDocument37 pagesPrelim HPCTMariaangela AliscuanoNo ratings yet

- Veterinary ImmunologyDocument271 pagesVeterinary ImmunologySam Bot100% (1)

- Microbiota Intestinal e Inmunidad. Review.2020Document15 pagesMicrobiota Intestinal e Inmunidad. Review.2020hacek357No ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of TBDocument3 pagesPathophysiology of TBEddie Lou GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MacrófagoDocument10 pagesMacrófagoFabro BianNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Acute and Chronic Inflammation: Ms.V. Rajalakshimi M.Pharm LecturerDocument82 pagesUnit 2 Acute and Chronic Inflammation: Ms.V. Rajalakshimi M.Pharm LecturerSheriffCaitlynNo ratings yet

- Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome Therapy On Inflammation: A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesMesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome Therapy On Inflammation: A Systematic ReviewJournal of Pharmacy & Pharmacognosy ResearchNo ratings yet

- IMMUNE SYSTEM - MedSurgDocument5 pagesIMMUNE SYSTEM - MedSurgAdiel CalsaNo ratings yet

- Targeting Hypoxia in The Tumor Microenvironment ADocument16 pagesTargeting Hypoxia in The Tumor Microenvironment AViviana OrellanaNo ratings yet

- Cellular and Molecular Immunology Module1: IntroductionDocument32 pagesCellular and Molecular Immunology Module1: IntroductionAygul RamankulovaNo ratings yet

- IRA 15th Conference 21.-24.9.2008Document57 pagesIRA 15th Conference 21.-24.9.2008shellyrahmaniaNo ratings yet

- From Inflammation To Sickness Historical PerspectiveDocument5 pagesFrom Inflammation To Sickness Historical PerspectiveВладимир ДружининNo ratings yet

- Chronic InflammationDocument24 pagesChronic InflammationTommys100% (1)

- Urinary System Test BankDocument30 pagesUrinary System Test BankVinz TombocNo ratings yet

- Nanofol: Folate-Based Nanobiodevices For Integrated Diagnosis/therapy Targeting Chronic Inflammatory DiseasesDocument4 pagesNanofol: Folate-Based Nanobiodevices For Integrated Diagnosis/therapy Targeting Chronic Inflammatory DiseasesAudrey POGETNo ratings yet

- Medical - 1 PPT UOGDocument1,003 pagesMedical - 1 PPT UOGCHALIE MEQU100% (1)

- (Let's Get Defensive) : Presented by Shruti Sharma, Pharmacology, 2 SemDocument46 pages(Let's Get Defensive) : Presented by Shruti Sharma, Pharmacology, 2 SemRiska Resty WasitaNo ratings yet

- 2 Blood and Immunology Module Study GuideDocument37 pages2 Blood and Immunology Module Study GuideMaryam FidaNo ratings yet

- My Journal 2Document11 pagesMy Journal 2FelixNo ratings yet

- Tumor ImunologiDocument45 pagesTumor ImunologiahdirNo ratings yet

- IVMS - General Pathology, Inflammation NotesDocument19 pagesIVMS - General Pathology, Inflammation NotesMarc Imhotep Cray, M.D.No ratings yet

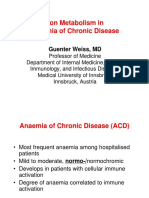

- Iron Metabolism in Anaemia of Chronic Disease: Guenter Weiss, MDDocument37 pagesIron Metabolism in Anaemia of Chronic Disease: Guenter Weiss, MDsome bodyNo ratings yet

- Sistem Imun 2Document20 pagesSistem Imun 2CameliaMasrijalNo ratings yet

- New Perspectives in Fermented Dairy Products and Their Health RelevanceDocument11 pagesNew Perspectives in Fermented Dairy Products and Their Health RelevanceAndrea Osorio AlturoNo ratings yet

Fungo Propolis

Fungo Propolis

Uploaded by

Suelen Santos da SilvaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fungo Propolis

Fungo Propolis

Uploaded by

Suelen Santos da SilvaCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Ethnopharmacology 79 (2002) 331 334 www.elsevier.

com/locate/jethpharm

Effects of propolis from Brazil and Bulgaria on fungicidal activity of macrophages against Paracoccidioides brasiliensis

J.M. Murad a, S.A. Calvi a, A.M.V.C. Soares a, V. Bankova b, J.M. Sforcin a,*

b

Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Biosciences Institute, IB-UNESP, 18618 -000 Botucatu, SP, Brazil Institute of Organic Chemistry with Centre of Phytochemistry, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 1113 Soa, Bulgaria Received 1 June 2001; received in revised form 1 November 2001; accepted 14 November 2001

Abstract Paracoccidioidomycosis is the most important systemic mycosis in Latin America. Its etiological agent, Paracoccidoides brasiliensis, affects individuals living in endemic areas through inhalation of airborne conidia or mycelial fragments. The disease may affect different organs and systems, with multiple clinical features, with cell-mediated immunity playing a signicant role in host defence. Peritoneal macrophages from BALB/c mice were stimulated with Brazilian or Bulgarian propolis and subsequently challenged with P. brasiliensis. Data suggest an increase in the fungicidal activity of macrophages by propolis stimulation, independently from its geographic origin. 2002 Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Propolis; Macrophage; Yeast; Paracoccidioides brasiliensis; Brazil; Bulgaria

1. Introduction Propolis is a sticky dark-coloured material that honeybees collect from plants, showing a very complex chemical composition (Bankova et al., 1999). It has been used in folk medicine since ancient times, due to its many biological properties, such as antimicrobial, antiinammatory, antioxidant, immunomodulatory activities, among others (Marcucci, 1995). In the temperate zone of the northern hemisphere, bees produce propolis from late spring until early autumn (about 4 months), collecting the material mainly from the bud exudate of poplar trees (Bankova et al., 1998b). In Brazil, propolis production proceeds throughout the entire year and seasonal variations in its chemical composition are not signicant and are predominantly quantitative (Boudourova-Krasteva et al., 1997; Bankova et al., 1998a; Sforcin et al., 2000). Baccharis dracunculifolia DC. was shown to be the main propolis source in Botucatu, Sao Paulo State, followed by Eucalyptus citriodora Hook. and Araucaria angustifolia (Bert.) O. Kuntze (Bankova et al., 1999).

* Corresponding author. E-mail address: sforcin@ibb.unesp.br (J.M. Sforcin).

Macrophages are involved in several processes, such as phagocytosis, enzyme liberation, free radical generation as well as mediators of inammatory processes. Scheller et al. (1988) suggested that the immunostimulant activity of propolis may be associated with macrophage activation and enhancement of macrophage phagocytic capacity. Tatefuji et al. (1996) investigated the effect of six propolis compounds on macrophage mobility and spreading. Paracoccidioidomycosis is a human systemic mycosis caused by the thermally dimorphic fungus Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (Lacaz, 1956). It is one of the most prevalently serious mycoses in Latin America and the great majority of the infected persons develop an asymptomatic pulmonary infection, although some individuals present clinical manifestations, leading to the dissemination of the disease. Clinical and experimental data indicate that cell-mediated immunity plays a signicant role in host defence, whereas high levels of specic antibodies are associated with the most severe form of this disease. Gamma-interferon (IFN-g) has been shown to play a protective role and is one major mediator of resistance against P. brasiliensis infection in mice (Cano et al., 1998). Experimental models have shown the role of macrophages in the mechanisms of resistance against this fungus.

0378-8741/02/$ - see front matter 2002 Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. PII: S 0 3 7 8 - 8 7 4 1 ( 0 1 ) 0 0 4 0 4 - 4

332

J.M. Murad et al. / Journal of Ethnopharmacology 79 (2002) 331334

The goal of the present research was to study the effects of various concentrations of propolis on the fungicidal activity of macrophages against P. brasiliensis. We also compared the effects of Brazilian propolis with those produced by a propolis sample from Bulgaria, using the same assay.

removed and macrophage monolayers were reincubated at 37 C for 24 h with Brazilian or Bulgarian propolis (5, 10 and 20 mg per well) or with IFN-g (100 U/ml).

2.4. Fungicidal acti6ity of macrophages against P. brasiliensis

After 24 h of incubation, supernatants were removed and macrophages were challenged with 4 104 fungal cells (at a ratio of 1:50 of fungus:macrophages) and 10% mice fresh serum. After co-culture for 4 h (experimental cultures), cells were harvested with distilled water to lyse the macrophages. Each culture and well washings were contained in 2 ml of distilled water. In order to determine fungicidal activity, the number of colony-forming units (CFU) of P. brasiliensis was determined by plating 0.1 ml of P. brasiliensis culture on agar plates containing Brain Heart Infusion Agar (BHI) supplemented with 4% horse serum and 5% Pb 192 culture ltrate, the latter constituting the source of growth-promoting factor (Singer-Vermes et al., 1992). A control culture containing only 0.1 ml of yeast cells of P. brasiliensis (4 104 viable units per ml) was submitted to the same procedures used for the experimental cultures. Plates were incubated at 37 C for 10 14 days in sealed plastic bags to prevent drying. At the end of this period, the number of CFU in each plate was counted. The percentage of fungicidal activity was determined using the formula: fungicidal activity= 1

2. Methodology

2.1. Propolis samples

Propolis was produced by africanized honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) in the Beekeeping Section of the School of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Husbandry of Botucatu, UNESP. Samples were obtained from plastic nets and were subsequently frozen to promote propolis removal (Toth, 1985). Propolis samples were ground and extracted (30 g of propolis, completing the volume to 100 ml with 70% ethanol) in the absence of bright light, at room temperature, with moderate shaking. After a week, extracts were ltered and diluted in distilled water (Sforcin et al., 1995).

2.2. Paracoccidioides brasiliensis

Yeast cells of P. brasiliensis 18 were maintained by weekly subculturing in a semisolid Fava Nettos culture medium at 35 C and used at the 7th day of culture. The fungal cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2), counted in a hemocytometer and the concentration was adjusted to 4 104 cells per ml. Viability of fungal suspension was determined on a phase contrast microscope. Bright cells were counted as viable, while dark ones as non-viable. Suspensions containing more than 90% viable fungi were used.

CFU experimental cultures CFU control

100

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Graph Pad Software 1993, San Diego, CA, USA. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed, followed by the multiple comparison test by TukeyKrammer method (Godfrey, 1985).

2.3. Animals and peritoneal macrophages

Male BALB/c mice weighing approximately 25 30 g and aged between 6 and 8 weeks were used. Peritoneal macrophages were obtained by inoculation of 35 ml of cold PBS in the abdominal cavity. After a soft abdominal massage for 30 s, the peritoneal liquid was collected with a Pasteur pipette and put in sterile plastic tubes (Falcon). This procedure was repeated three or four times for each animal and the tubes were centrifuged at 200 g for 10 min. Cells were pooled and resuspended in cell culture medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 40 mg/ml gentamycine, 20 mM HEPES, 2.5 10 5 M 2-mercaptoethanol) and cultured in a 96-welled at-bottomed plate (Corning) at a nal concentration of 2105 cells per well. After 2 h at 37 C, non-adherent cells were

3. Results and discussion Propolis has been used in human and veterinary medicine, because of its therapeutical properties. Its antifungal property has also been established (Marcucci, 1995). Thus, this research was performed to evaluate the possible effect of propolis on the fungicidal activity of macrophages against P. brasiliensis. Macrophages were stimulated with Brazilian propolis and results are shown in Table 1. It can be seen from this table that propolis increased the fungicidal activity

J.M. Murad et al. / Journal of Ethnopharmacology 79 (2002) 331334

333

when compared with control cells, but not signicantly. Although this increase was not statistically signicant, this fact has its biological importance and should be taken into account, since propolis was able to activate macrophage and enhance its fungicidal action, but less efciently than IFN-g-cytokyne used as a positive control. In a recent work in our laboratory using human cells, adequate concentrations of tumour necrosis factor (TNF-a) alone or in a synergistic effect with IFN-g signicantly increased the fungicidal activity of these cells. Dimov et al. (1992) reported that the water-soluble derivative of propolis activated macrophages to produce several mediators, such as IL-1 and TNF. Propolis could exert its function by increasing directly the liberation of fungicidal substances by macrophages, such as oxygen and nitrogen metabolites, as well as inducing production of some cytokynes. The process of phagocytosis is complex and involves the binding of the target to the surface of macrophages

and ingestion, which usually triggers the so-called oxidative burst. Ivanovska et al. (1993), investigating the effects of individual propolis constituents complexed with lysine, found that cinnamic acid tends to inhibit H2O2 release by peritoneal macrophages, while caffeic acid induces its production. Orsi et al. (2000) suggested that propolis acts on the hosts non-specic immunity, inducing a discrete elevation in hydrogen peroxide release and producing a mild inhibition of nitric oxide generation. As to the Bulgarian propolis, it also showed a nonsignicant increase in the fungicidal activity of macrophages (Table 1). Fig. 1 shows a comparison between Brazilian and Bulgarian propolis activities. It may be seen that both samples had a modulatory action on macrophages, without signicant differences between them. In the past few years, propolis has become a subject of increasing interest for both commercial and scientic reasons. Its chemical composition varies according to

Table 1 Fungicidal activity of peritoneal macrophages activated with IFN-g (100 U/ml) or with Brazilian or Bulgarian propolis (P) in different concentrations and challenged with P. brasiliensis 18 yeast Control Brazil Bulgaria 32.3 (2.9) 32.3 (2.9) P5 41.0 (4.9) 35.6 (3.4) P10 40.5 (2.3) 38.3 (3.8) P20 39.0 (4.0) 47.0 (3.5) IFN-g 54.3 (2.0) 54.3 (2.0)

Results are means 9standard deviation (S.D.) of three similar assays. Values are % fungicidal activity of macrophages.

Fig. 1. Comparison between Brazilian and Bulgarian propolis with respect to the fungicidal activity of peritoneal macrophages challenged with P. brasiliensis 18 yeast. *Statistically different from IFN-g (PB 0.05).

334

J.M. Murad et al. / Journal of Ethnopharmacology 79 (2002) 331334 Cano, L.E., Kashino, S.S., Arruda, C., Andre, D., Xidieh, C.F., Singer-Vermes, L.M., Vaz, C.A.C., Burger, E., Calich, V.L.G., 1998. Protective role of gamma interferon in experimental pulmonary paracoccidioidomycosis. Infection and Immunity 66, 800 806. Dimov, V., Ivanovska, N., Bankova, V., Popov, S., 1992. Immunomodulatory action of propolis: IV. Prophylactic activity against Gram-negative infections and adjuvant effect of the watersoluble derivative. Vaccine 10, 817 823. Godfrey, K., 1985. Statistics in practice. Comparing the means of several groups. New England Journal of Medicine 313, 1450 1456. Ivanovska, N., Stefanova, Z., Valeva, V., Neychev, H., 1993. Immunomodulatory action of propolis:VII. A comparative study on cinnamic and caffeic acid lysine derivatives, Comptes Rendus de L. Academie Bulgare des Sciences 46, 115 117. Lacaz, C.S., 1956. South American Blastomycosis. Anais da Faculdade de Medicina de Sao Paulo, 29, 7 120. Marcucci, M.C., 1995. Propolis: chemical composition, biological properties and therapeutic activity. Apidologie 26, 83 99. Orsi, R.O., Funari, S.R.C., Soares, A.M.V.C., Calvi, S.A., Oliveira, S.L., Sforcin, J.M., Bankova, V., 2000. Immunomodulatory action of propolis on macrophage activation. The Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins 6, 205 219. Scheller, S., Gazda, G., Pietsz, G., Gabrys, J., Szumlas, J., Eckert, J., Shani, J., 1988. The ability of ethanolic extract of propolis to stimulate plaque formation in immunized mouse spleen cells. Pharmacological Research Communications 20, 323 328. Sforcin, J.M., Novelli, E.L.B., Funari, S.R.C., 1995. Serum biochemical determinations of propolis-treated rats. The Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins 1, 31 37. Sforcin, J.M., Fernandes, A. Jr, Lopes, C.A.M., Bankova, V., Funari, S.R.C., 2000. Seasonal effect on Brazilian propolis antibacterial activity. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 73, 243 249. Singer-Vermes, L.M., Ciavaglia, M.C., Kashino, S.S., Burger, E., Calich, V.L.G., 1992. The source of the growth-promoting factor (s) affects the plating efciency of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. Journal of Medical and Veterinary Mycology 30, 261 264. Tatefuji, T., Izumi, N., Ohta, T., Arai, S., Ikeda, M., Kurimoto, M., 1996. Isolation and identication of compounds from Brazilian propolis which enhance macrophage spreading and mobility. Biological and Pharmacological Bulletin 19, 966 970. Toth, G., 1985. Propolis: medicine or fraud? American Bee Journal 125, 337 338.

its geographical origin, which may inuence its biological properties. Depending on the local ora, one may nd some chemical compounds in lower or higher concentrations in the samples, or even their absence. In this work, Brazilian and Bulgarian propolis samples had similar effects, although they were produced in widely separated geographic regions. Contrary to propolis from the temperate zones, where poplars are its sole source, in Brazil there are many more plants that bees could visit as sources of propolis, and depending on the location, its chemical composition can differ. Since mankind has been using propolis since early times, a better understanding of its action in the immune response will provide a scientic basis for a better therapeutic application in human or veterinary medicine whether it is associated or not with conventional treatments.

Acknowledgements Brazilian authors wish to thank Dr Vassya Bankova, Bulgaria, for providing the Bulgarian propolis sample.

References

Bankova, V., Boudourova-Krasteva, G., Popov, S., Sforcin, J.M., Funari, S.R.C., 1998a. Seasonal variations in essential oil from Brazilian propolis. Journal of Essential Oil Research 10, 693 696. Bankova, V., Boudourova-Krasteva, G., Popov, S., Sforcin, J.M., Funari, S.R.C., 1998b. Seasonal variations of the chemical composition of Brazilian propolis. Apidologie 29, 361 367. Bankova, V., Boudourova-Krasteva, G., Sforcin, J.M., Frete, X., Kujumgiev, A., Maimoni-Rodella, R., Popov, S., 1999. Phytochemical evidence for the plant origin of Brazilian propolis from Sao Paulo State. Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung 54c, 401 405. Boudourova-Krasteva, G., Bankova, V., Sforcin, J.M., Nikolova, N., Popov, S., 1997. Phenolics from Brazilian propolis. Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung 52c, 676 679.

You might also like

- Chap 14Document39 pagesChap 14Koby100% (4)

- Orsi 2005Document10 pagesOrsi 2005vahidNo ratings yet

- CARDOSO Et Al 2010 - Propolis Staphylo e Malassezia - Otite CaninaDocument3 pagesCARDOSO Et Al 2010 - Propolis Staphylo e Malassezia - Otite CaninaDébora SakiyamaNo ratings yet

- Galleria Mellonella As An in Vivo Model For Assessing The Protective Activity of Probiotics Against Gastrointestinal Bacterial PathogensDocument6 pagesGalleria Mellonella As An in Vivo Model For Assessing The Protective Activity of Probiotics Against Gastrointestinal Bacterial PathogensJosXe CalderonNo ratings yet

- In Vitro Multiplication of Eucalyptus Hybrid Via: Temporary Immersion Bioreactor: Culture Media and Cytokinin EffectsDocument8 pagesIn Vitro Multiplication of Eucalyptus Hybrid Via: Temporary Immersion Bioreactor: Culture Media and Cytokinin EffectsFenny OctavianiNo ratings yet

- 3 PDFDocument3 pages3 PDFGeraldineMoletaGabutinNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Giving Trigona Honey and HDocument4 pagesThe Effect of Giving Trigona Honey and HNurul Muqarribah Pratiwi IshaqNo ratings yet

- Bioefficacy of Mosquito Mat Vaporizers and Associated Metabolic DetoxicationDocument11 pagesBioefficacy of Mosquito Mat Vaporizers and Associated Metabolic DetoxicationNg Kin HoongNo ratings yet

- A Study of The Larvicidal and Molluscicidal Activities of Some Medicinal Plants From Northeast BrazilDocument8 pagesA Study of The Larvicidal and Molluscicidal Activities of Some Medicinal Plants From Northeast BrazilJosé Teófilo Moreira FilhoNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial Activity Test of Medicinal Plant Extract Using Antimicrobial Disc and Filter PaperDocument9 pagesAntimicrobial Activity Test of Medicinal Plant Extract Using Antimicrobial Disc and Filter PaperGinnyNo ratings yet

- Activity 2 - Antifungal StudyDocument6 pagesActivity 2 - Antifungal StudyDuke TenchavezNo ratings yet

- Fungo Endofitico T. Granulosa - QuaresmeiraDocument13 pagesFungo Endofitico T. Granulosa - Quaresmeiratata.andrade.profNo ratings yet

- Geopropolis Mandaguari PretaDocument11 pagesGeopropolis Mandaguari PretaJonas GarciaNo ratings yet

- Fração Biomassa Ostreatus Sarcoma 2017Document8 pagesFração Biomassa Ostreatus Sarcoma 2017Edward Marques de SouzaNo ratings yet

- Solid State Fermentation of Jatropha Curcas Kernel Cake With Cocktail of FungiDocument8 pagesSolid State Fermentation of Jatropha Curcas Kernel Cake With Cocktail of FungiAnowar RazvyNo ratings yet

- Liu, 2013Document10 pagesLiu, 2013abudiharjo73No ratings yet

- tmp73EA TMPDocument15 pagestmp73EA TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Propolis in The Control of Helminths in Sheep - IJAAR-Vol-14-No-6-p-69-74Document6 pagesPropolis in The Control of Helminths in Sheep - IJAAR-Vol-14-No-6-p-69-74International Network For Natural SciencesNo ratings yet

- 394 668 1 SMDocument8 pages394 668 1 SMRizka Amanda FauziaNo ratings yet

- Template JRBA Rev 2Document13 pagesTemplate JRBA Rev 2FRISKA CHRISTININGRUMNo ratings yet

- Araujo Etal 2005 WJ MBDocument7 pagesAraujo Etal 2005 WJ MBFabiolaNo ratings yet

- Ovad 045Document8 pagesOvad 045phong nguyễnNo ratings yet

- Cartagena Filamentus FungusDocument17 pagesCartagena Filamentus FungusLorena Sosa LunaNo ratings yet

- Artigo RubensDocument8 pagesArtigo RubensbuissaNo ratings yet

- 2018 Satish PoojariDocument4 pages2018 Satish PoojariDr Estari MamidalaNo ratings yet

- Effective Control of Black Sigatoka DiseDocument8 pagesEffective Control of Black Sigatoka DiseIsrael Kelly AntolinNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Production of Antifungal Metabolites Against MutagenesisDocument9 pagesEvaluation of The Production of Antifungal Metabolites Against MutagenesisDũng NguyễnNo ratings yet

- 5QBJ - 1472-6882-11-108-p - GEOPROPOLISDocument10 pages5QBJ - 1472-6882-11-108-p - GEOPROPOLISAnonymous OdfoTPUNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Ahmad Rafdi Wiharja 081211433013Document22 pagesJurnal Ahmad Rafdi Wiharja 081211433013titanNo ratings yet

- Jurnal - Efek Imunostimulator Propolis TerhadapDocument7 pagesJurnal - Efek Imunostimulator Propolis TerhadapArifin I. OputuNo ratings yet

- Antiviral Effects of Brazilian Green and RedDocument10 pagesAntiviral Effects of Brazilian Green and RedDebora PereiraNo ratings yet

- Floram 27 2 E20170718Document6 pagesFloram 27 2 E20170718Tatiany NóbregaNo ratings yet

- Pathogenicity of Epicoccum Sorghinum Towards Dragon FruitsDocument8 pagesPathogenicity of Epicoccum Sorghinum Towards Dragon FruitsJuan PachecoNo ratings yet

- Theobroma Cacao PhytophthoraDocument10 pagesTheobroma Cacao PhytophthoraOpenaccess Research paperNo ratings yet

- Pseudomonas Alcaligenes, Potential Antagonist Against Fusarium Oxysporum F.SP - Lycopersicum The Cause of Fusarium Wilt Disease On TomatoDocument8 pagesPseudomonas Alcaligenes, Potential Antagonist Against Fusarium Oxysporum F.SP - Lycopersicum The Cause of Fusarium Wilt Disease On TomatoAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Armando Et Al 2011Document10 pagesArmando Et Al 2011Adrian Melgratti JobsonNo ratings yet

- Da Silva 2013 - ECAM - Brazilian Propolis Antileishmanial and Immunomodulatory EffectsDocument8 pagesDa Silva 2013 - ECAM - Brazilian Propolis Antileishmanial and Immunomodulatory EffectsmilenamiNo ratings yet

- Biological Activities of The Fermentation Extract of The Endophytic Fungus Alternaria Alternata Isolated From Coffea Arabica LDocument13 pagesBiological Activities of The Fermentation Extract of The Endophytic Fungus Alternaria Alternata Isolated From Coffea Arabica LCece MarzamanNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2667011923000282 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S2667011923000282 MainJoao Sousa RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Acaricidal Activity of Extracts From Different Structures of Piper Tuberculatum Against Larvae and Adults of Rhipicephalus MicroplusDocument6 pagesAcaricidal Activity of Extracts From Different Structures of Piper Tuberculatum Against Larvae and Adults of Rhipicephalus MicroplusLaura Estefania Niño MNo ratings yet

- Bot513 03Document8 pagesBot513 03Ponechor HomeNo ratings yet

- Palmivora (Butler) Butler Penyebab Penyakit Busuk BuahDocument11 pagesPalmivora (Butler) Butler Penyebab Penyakit Busuk BuahRyan Afriandi SiregarNo ratings yet

- Phytochemical Characterization of Pumpkin Seed WithDocument8 pagesPhytochemical Characterization of Pumpkin Seed WithLarisa CatautaNo ratings yet

- Molluscicidal and Ovicidal Activities of Plant Extracts 2011Document8 pagesMolluscicidal and Ovicidal Activities of Plant Extracts 2011Juan Enrique Tacoronte MoralesNo ratings yet

- Vieira Etal 2017Document8 pagesVieira Etal 2017Manuel ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Microbiological assessment of fresh, minimally processed vegetables from open air markets and supermarkets in Luzon, Philippines, for food safetyDocument10 pagesMicrobiological assessment of fresh, minimally processed vegetables from open air markets and supermarkets in Luzon, Philippines, for food safetyiyaNo ratings yet

- IOSRPHRDocument3 pagesIOSRPHRIOSR Journal of PharmacyNo ratings yet

- Immunity To Plasmodium KnowlesiDocument6 pagesImmunity To Plasmodium KnowlesimustrechNo ratings yet

- Effect of 2,4-D, Hydric Stress and Light On Indica Rice (Oryza Sativa) Somatic EmbryogenesisDocument8 pagesEffect of 2,4-D, Hydric Stress and Light On Indica Rice (Oryza Sativa) Somatic EmbryogenesisGaurav ChandrakantNo ratings yet

- Baert, Samapundo 2007Document12 pagesBaert, Samapundo 2007Jerusalen BetancourtNo ratings yet

- In Vitro Anthelmintic Activity of The Crude Hydroalcoholic Extract of PiperDocument6 pagesIn Vitro Anthelmintic Activity of The Crude Hydroalcoholic Extract of PiperMarcial Fuentes EstradaNo ratings yet

- An Efficient Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation Protocol For Black Pepper (Piper Nigrum L.) Using Embryogenic Mass As ExplantDocument8 pagesAn Efficient Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation Protocol For Black Pepper (Piper Nigrum L.) Using Embryogenic Mass As ExplantIman Fadhul HadiNo ratings yet

- Food Research InternationalDocument9 pagesFood Research InternationalNaticita Rincon MacoteNo ratings yet

- tmp42AA TMPDocument8 pagestmp42AA TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Giving Trigona Honey and Honey Propolis Trigona To The mRNA Foxp3 Expression in Mice Balb/c Strain Induced by Salmonella TyphiDocument45 pagesThe Effect of Giving Trigona Honey and Honey Propolis Trigona To The mRNA Foxp3 Expression in Mice Balb/c Strain Induced by Salmonella TyphiNisfi Laelah GirltsaniieNo ratings yet

- Antifungal Activity of GuavaDocument11 pagesAntifungal Activity of GuavaFarij AbdurrohmanNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial Activity of Nigella Sativa Seed ExtractDocument5 pagesAntimicrobial Activity of Nigella Sativa Seed ExtractDian Takwa HarahapNo ratings yet

- Antibact AssayDocument7 pagesAntibact Assaymakerk82No ratings yet

- BR - PLG MiceDocument8 pagesBR - PLG Miceyogi75No ratings yet

- Plant-derived Pharmaceuticals: Principles and Applications for Developing CountriesFrom EverandPlant-derived Pharmaceuticals: Principles and Applications for Developing CountriesNo ratings yet

- Microbial Plant Pathogens: Detection and Management in Seeds and PropagulesFrom EverandMicrobial Plant Pathogens: Detection and Management in Seeds and PropagulesNo ratings yet

- 6 Helpful Ways To Boost Immune HealthDocument6 pages6 Helpful Ways To Boost Immune HealthDennis Noel BejerNo ratings yet

- Imse LectureDocument19 pagesImse LectureJOWELA RUBY EUSEBIONo ratings yet

- Tyrosine Kinase Receptors in Oncology: Molecular SciencesDocument48 pagesTyrosine Kinase Receptors in Oncology: Molecular SciencesAnuradha Monga KapoorNo ratings yet

- Immunology Overview: Armond S. Goldman Bellur S. PrabhakarDocument45 pagesImmunology Overview: Armond S. Goldman Bellur S. PrabhakarIoana AsziaNo ratings yet

- Immunology KubyDocument24 pagesImmunology KubySayanta Bera100% (1)

- Prelim HPCTDocument37 pagesPrelim HPCTMariaangela AliscuanoNo ratings yet

- Veterinary ImmunologyDocument271 pagesVeterinary ImmunologySam Bot100% (1)

- Microbiota Intestinal e Inmunidad. Review.2020Document15 pagesMicrobiota Intestinal e Inmunidad. Review.2020hacek357No ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of TBDocument3 pagesPathophysiology of TBEddie Lou GuzmanNo ratings yet

- MacrófagoDocument10 pagesMacrófagoFabro BianNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Acute and Chronic Inflammation: Ms.V. Rajalakshimi M.Pharm LecturerDocument82 pagesUnit 2 Acute and Chronic Inflammation: Ms.V. Rajalakshimi M.Pharm LecturerSheriffCaitlynNo ratings yet

- Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome Therapy On Inflammation: A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesMesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome Therapy On Inflammation: A Systematic ReviewJournal of Pharmacy & Pharmacognosy ResearchNo ratings yet

- IMMUNE SYSTEM - MedSurgDocument5 pagesIMMUNE SYSTEM - MedSurgAdiel CalsaNo ratings yet

- Targeting Hypoxia in The Tumor Microenvironment ADocument16 pagesTargeting Hypoxia in The Tumor Microenvironment AViviana OrellanaNo ratings yet

- Cellular and Molecular Immunology Module1: IntroductionDocument32 pagesCellular and Molecular Immunology Module1: IntroductionAygul RamankulovaNo ratings yet

- IRA 15th Conference 21.-24.9.2008Document57 pagesIRA 15th Conference 21.-24.9.2008shellyrahmaniaNo ratings yet

- From Inflammation To Sickness Historical PerspectiveDocument5 pagesFrom Inflammation To Sickness Historical PerspectiveВладимир ДружининNo ratings yet

- Chronic InflammationDocument24 pagesChronic InflammationTommys100% (1)

- Urinary System Test BankDocument30 pagesUrinary System Test BankVinz TombocNo ratings yet

- Nanofol: Folate-Based Nanobiodevices For Integrated Diagnosis/therapy Targeting Chronic Inflammatory DiseasesDocument4 pagesNanofol: Folate-Based Nanobiodevices For Integrated Diagnosis/therapy Targeting Chronic Inflammatory DiseasesAudrey POGETNo ratings yet

- Medical - 1 PPT UOGDocument1,003 pagesMedical - 1 PPT UOGCHALIE MEQU100% (1)

- (Let's Get Defensive) : Presented by Shruti Sharma, Pharmacology, 2 SemDocument46 pages(Let's Get Defensive) : Presented by Shruti Sharma, Pharmacology, 2 SemRiska Resty WasitaNo ratings yet

- 2 Blood and Immunology Module Study GuideDocument37 pages2 Blood and Immunology Module Study GuideMaryam FidaNo ratings yet

- My Journal 2Document11 pagesMy Journal 2FelixNo ratings yet

- Tumor ImunologiDocument45 pagesTumor ImunologiahdirNo ratings yet

- IVMS - General Pathology, Inflammation NotesDocument19 pagesIVMS - General Pathology, Inflammation NotesMarc Imhotep Cray, M.D.No ratings yet

- Iron Metabolism in Anaemia of Chronic Disease: Guenter Weiss, MDDocument37 pagesIron Metabolism in Anaemia of Chronic Disease: Guenter Weiss, MDsome bodyNo ratings yet

- Sistem Imun 2Document20 pagesSistem Imun 2CameliaMasrijalNo ratings yet

- New Perspectives in Fermented Dairy Products and Their Health RelevanceDocument11 pagesNew Perspectives in Fermented Dairy Products and Their Health RelevanceAndrea Osorio AlturoNo ratings yet