Professional Documents

Culture Documents

J, E, M, A A C: Ustifying Xempting Itigating Ggravating AND Lternative Ircumstances

J, E, M, A A C: Ustifying Xempting Itigating Ggravating AND Lternative Ircumstances

Uploaded by

mirCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Colouring Book Mandalas and MosaicsDocument76 pagesColouring Book Mandalas and Mosaicsszulamit halasi100% (3)

- 22 Chapter 2 Section 141-To-143Document1 page22 Chapter 2 Section 141-To-143Kenya Monique Huston ElNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law JDDocument23 pagesCriminal Law JDCooksNo ratings yet

- Art. 11 of RPCDocument168 pagesArt. 11 of RPCCastrel AcerNo ratings yet

- Claw 3 Notes 3Document11 pagesClaw 3 Notes 3Nicko SalinasNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law JEMAADocument117 pagesCriminal Law JEMAAGalindo, Hans DavidNo ratings yet

- CRIM Slides EditedDocument6 pagesCRIM Slides EditedApril Kirstin ChuaNo ratings yet

- Arts.11, 12 and 15Document28 pagesArts.11, 12 and 15Rodelyn SagamlaNo ratings yet

- Notes On Art. 11 of The Revised Penal CodeDocument12 pagesNotes On Art. 11 of The Revised Penal CodelemonnerriNo ratings yet

- Self-Defense Research 04212016Document4 pagesSelf-Defense Research 04212016KriziaItaoNo ratings yet

- Group 3 Report Part 1 and 2Document155 pagesGroup 3 Report Part 1 and 2Patricia Ortega50% (2)

- Kenneth Martin E. Dela Cruz - Assignment#1 - Section BDocument7 pagesKenneth Martin E. Dela Cruz - Assignment#1 - Section BKenneth Martin E. Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Art 11 Justifying CircumstancesDocument30 pagesArt 11 Justifying CircumstancesJabami YumekoNo ratings yet

- Crim - PimentelDocument98 pagesCrim - PimentelLirio IringanNo ratings yet

- Crim Law ReviewerDocument28 pagesCrim Law ReviewerJenny Reyes100% (1)

- Self-Defense JurisprudenceDocument4 pagesSelf-Defense Jurisprudencejessi berNo ratings yet

- Essential Points On Circumstances Affecting Criminal LiabilityDocument8 pagesEssential Points On Circumstances Affecting Criminal LiabilityRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- BP 22 Is Malum ProhibitumDocument4 pagesBP 22 Is Malum ProhibitumJade Marlu DelaTorreNo ratings yet

- Justifying and Exempting CircumstancesDocument6 pagesJustifying and Exempting CircumstancesRophelus GalendezNo ratings yet

- Kenneth Martin E. Dela Cruz - Assignment#1 - Section BDocument8 pagesKenneth Martin E. Dela Cruz - Assignment#1 - Section BKenneth Martin E. Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Crim MidtermsDocument28 pagesCrim MidtermsSunshine RubinNo ratings yet

- Crim 1 - 2 Chapter 2: Justifying Circumstances and Circumstances Which Exempt From Criminal Liability Circumstances Affecting Criminal LiabilityDocument3 pagesCrim 1 - 2 Chapter 2: Justifying Circumstances and Circumstances Which Exempt From Criminal Liability Circumstances Affecting Criminal LiabilityLuis RetananNo ratings yet

- Justifying Circumstances: / January 28, 2010Document8 pagesJustifying Circumstances: / January 28, 2010Mayela Lou AdajarNo ratings yet

- Notes On Crim. Law Review Part 2Document11 pagesNotes On Crim. Law Review Part 2Mayett LarrosaNo ratings yet

- People Vs Dulin June 29 2015Document19 pagesPeople Vs Dulin June 29 2015KM HanNo ratings yet

- Article 11 RPCDocument53 pagesArticle 11 RPCRuffa mae PortugalNo ratings yet

- Art. 11 Criminal Law ReviewerDocument13 pagesArt. 11 Criminal Law ReviewerTeresa CardinozaNo ratings yet

- WEEK 1.2 AssaultDocument5 pagesWEEK 1.2 AssaultammarizvandiarNo ratings yet

- Justifying CicumstancesDocument14 pagesJustifying CicumstancesPatrick AlcanarNo ratings yet

- 2010 Updates in Criminal LawDocument114 pages2010 Updates in Criminal LawEller-JedManalacMendozaNo ratings yet

- Reply AffidavitDocument7 pagesReply Affidavitnoel sincoNo ratings yet

- JEMAADocument7 pagesJEMAAYanyan De LeonNo ratings yet

- Crim Law FlashcardDocument13 pagesCrim Law FlashcardLeoncio DanielNo ratings yet

- Sgt.-Real, Position PaperDocument9 pagesSgt.-Real, Position PaperAldrinNo ratings yet

- ART 4 RPC Felonies and Circumstances Affecting Criminal LiabilityDocument39 pagesART 4 RPC Felonies and Circumstances Affecting Criminal LiabilityJewel Francine PUDESNo ratings yet

- RPC Art 11-15Document22 pagesRPC Art 11-15Van Openiano0% (1)

- Notes On Crim. Law Review MidtermDocument24 pagesNotes On Crim. Law Review MidtermMayett LarrosaNo ratings yet

- Article 11 Justifying Circumstances AidDocument12 pagesArticle 11 Justifying Circumstances AidMercy LingatingNo ratings yet

- 10th Reading Assignment (Crim)Document6 pages10th Reading Assignment (Crim)JB JuneNo ratings yet

- Justifying CircumstancesDocument23 pagesJustifying CircumstancesJhayvee Garcia100% (1)

- Trial Memorandum - Self-DefenseDocument18 pagesTrial Memorandum - Self-DefenseSiobhan RobinNo ratings yet

- LectureDocument5 pagesLecturePaul Angelo 黃種 武No ratings yet

- People vs. OlarbeDocument14 pagesPeople vs. OlarbeSinha ElleNo ratings yet

- Modifying CircumstanceDocument37 pagesModifying CircumstanceMae Ann Joy LamentaNo ratings yet

- Self DefenseDocument8 pagesSelf DefenseFrancis OcadoNo ratings yet

- Self DefenseDocument8 pagesSelf DefenseFrancis OcadoNo ratings yet

- Campanilla Lectures PartDocument8 pagesCampanilla Lectures PartJose JarlathNo ratings yet

- Other Circumstances/Factors Which Affect Criminal LiabilityDocument4 pagesOther Circumstances/Factors Which Affect Criminal LiabilityJazireeNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law - Justifying CircumstancesDocument9 pagesCriminal Law - Justifying CircumstancesAndrea Felice AbesamisNo ratings yet

- Just and Exemp RevDocument20 pagesJust and Exemp RevRimvan Le SufeorNo ratings yet

- Par 1. Self-Defense: Marlo C. Manuel L-1900166Document21 pagesPar 1. Self-Defense: Marlo C. Manuel L-1900166Marlo Caluya Manuel100% (1)

- Versus-Criminal Case No.: Counter-AffidavitDocument6 pagesVersus-Criminal Case No.: Counter-AffidavitJan Paul CrudaNo ratings yet

- Art 11 JustifyingDocument6 pagesArt 11 JustifyingYanne AriasNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Last Minute Tips 2018Document14 pagesCriminal Law Last Minute Tips 2018Jimcris Posadas HermosadoNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law (Caguioa Notes)Document42 pagesCriminal Law (Caguioa Notes)Jeadic St. MoniqueNo ratings yet

- CRIM 1 CASE DIGEST - CORPIN - CRL1 - JDNT-1B1 - Felonies - Part2Document11 pagesCRIM 1 CASE DIGEST - CORPIN - CRL1 - JDNT-1B1 - Felonies - Part2JemNo ratings yet

- Module 5 in Crim Law.2nd SemDocument45 pagesModule 5 in Crim Law.2nd SemNicoleNo ratings yet

- Criminal LDocument58 pagesCriminal LbilliatlearnmoreNo ratings yet

- Nacnac V. PeopleDocument6 pagesNacnac V. PeopleSean Bofill-GallardoNo ratings yet

- Ustifying Ircumstances: Ricky Russell Paul Obienda ValbarezDocument16 pagesUstifying Ircumstances: Ricky Russell Paul Obienda Valbarezlkristin0% (1)

- General Defences in Criminal Law IntoxicationDocument19 pagesGeneral Defences in Criminal Law IntoxicationPapah ReyNo ratings yet

- A I S L: Pplication of The Ndeterminate Entence AWDocument6 pagesA I S L: Pplication of The Ndeterminate Entence AWmirNo ratings yet

- Executive DeptDocument19 pagesExecutive DeptmirNo ratings yet

- Afulugencia vs. MetrobankDocument15 pagesAfulugencia vs. MetrobankmirNo ratings yet

- Duque vs. YuDocument13 pagesDuque vs. YumirNo ratings yet

- Disini V SandiganbayanDocument34 pagesDisini V SandiganbayanmirNo ratings yet

- 1 Saguisag Case July 26Document48 pages1 Saguisag Case July 26mirNo ratings yet

- Cenntral Azucarera de Bais Vs Heirs of ApostolDocument22 pagesCenntral Azucarera de Bais Vs Heirs of ApostolmirNo ratings yet

- Ang Lad Lad Vs ComelecDocument99 pagesAng Lad Lad Vs ComelecmirNo ratings yet

- R 128 To 133 Case Doctrines On EvidenceDocument105 pagesR 128 To 133 Case Doctrines On EvidencemirNo ratings yet

- Consolidate Remedial Law Review 2 Transcribed Notes: Provisional Remedies To Special ProceedingsDocument75 pagesConsolidate Remedial Law Review 2 Transcribed Notes: Provisional Remedies To Special ProceedingsmirNo ratings yet

- Phil. Health vs. Our Lady of Lourdes HospitalDocument14 pagesPhil. Health vs. Our Lady of Lourdes HospitalmirNo ratings yet

- People Vs WebbDocument31 pagesPeople Vs WebbmirNo ratings yet

- Human Rights Violation by Police in IndiaDocument18 pagesHuman Rights Violation by Police in IndiaNitisha GeedNo ratings yet

- IJAL Volume 7 Issue 2 Ajar RabDocument20 pagesIJAL Volume 7 Issue 2 Ajar RabAdrin AshNo ratings yet

- 121 20020214 Jud 01 08 en PDFDocument37 pages121 20020214 Jud 01 08 en PDFCalMustoNo ratings yet

- Constitution in Nutshell PDFDocument19 pagesConstitution in Nutshell PDFel capitanNo ratings yet

- SealandDocument4 pagesSealandHansel Jake B. Pampilo100% (1)

- Code of Mechanical Engineering Ethics in The PhilippinesDocument24 pagesCode of Mechanical Engineering Ethics in The PhilippinesJan Lorenz100% (1)

- Renvoi: (Doctrine, Concept, History, Advantages and Disadvantages)Document12 pagesRenvoi: (Doctrine, Concept, History, Advantages and Disadvantages)Qadir JavedNo ratings yet

- Exercise - The Indian ConstitutionDocument4 pagesExercise - The Indian ConstitutionSameer SurlaNo ratings yet

- Tecnogas Philippines Manufacturing Corp. vs. Court of AppealsDocument17 pagesTecnogas Philippines Manufacturing Corp. vs. Court of AppealsCarrie Anne GarciaNo ratings yet

- Duty of Care (I) SlidesDocument35 pagesDuty of Care (I) SlidesShabab TahsinNo ratings yet

- Instruction HandoutsDocument8 pagesInstruction HandoutsTroy WelchNo ratings yet

- What Is TaekwondoDocument10 pagesWhat Is TaekwondoGrace JPNo ratings yet

- Case DigestsDocument90 pagesCase DigestsMicaela Dela PeñaNo ratings yet

- T. Sareetha v. T. Venkata SubbaiahDocument16 pagesT. Sareetha v. T. Venkata SubbaiahSreenath NamboodiriNo ratings yet

- Battered Woman Syndrome The Justifying CDocument9 pagesBattered Woman Syndrome The Justifying CcharmssatellNo ratings yet

- People vs. MendozaDocument6 pagesPeople vs. MendozaDi ko alamNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 1 - Criminal LawDocument27 pagesTutorial 1 - Criminal LawRaphael Karasu-ThirdNo ratings yet

- People vs. Del RosarioDocument11 pagesPeople vs. Del RosarioIrish Marie CabreraNo ratings yet

- The Criminal Procedure (Identification) Bill 2022Document6 pagesThe Criminal Procedure (Identification) Bill 2022Abhishek BiswalNo ratings yet

- People V MalunsingDocument3 pagesPeople V MalunsingRamchand CaitorNo ratings yet

- Malfeasance, Misfeasance and NonfeasanceDocument1 pageMalfeasance, Misfeasance and Nonfeasanceeaglelegal67% (3)

- Team Code-R24: ICC Trial ChamberDocument28 pagesTeam Code-R24: ICC Trial ChamberShikhar SrivastavNo ratings yet

- EthicsDocument13 pagesEthicsJayc ChantengcoNo ratings yet

- The Lotus CaseDocument5 pagesThe Lotus Caseraul_beke118No ratings yet

- ContractsDocument14 pagesContractsNikunj sikariaNo ratings yet

- Introductory Provisions Chapter-1,2 & 3 General Exceptions Chapter-4 Sec-76-106 Penal Provisions of Offences Chapter-5-23 Sec-107-511Document1 pageIntroductory Provisions Chapter-1,2 & 3 General Exceptions Chapter-4 Sec-76-106 Penal Provisions of Offences Chapter-5-23 Sec-107-511KARTHIKEYAN MNo ratings yet

- What Is Law - ParanjapeDocument3 pagesWhat Is Law - ParanjapeKushaal JadhavNo ratings yet

- 03 TOM Civil Law Reviewer - PagesDocument927 pages03 TOM Civil Law Reviewer - PagesDee EismaNo ratings yet

J, E, M, A A C: Ustifying Xempting Itigating Ggravating AND Lternative Ircumstances

J, E, M, A A C: Ustifying Xempting Itigating Ggravating AND Lternative Ircumstances

Uploaded by

mirOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

J, E, M, A A C: Ustifying Xempting Itigating Ggravating AND Lternative Ircumstances

J, E, M, A A C: Ustifying Xempting Itigating Ggravating AND Lternative Ircumstances

Uploaded by

mirCopyright:

Available Formats

JUSTIFYING, EXEMPTING, MITIGATING, AGGRAVATING

AND ALTERNATIVE CIRCUMSTANCES

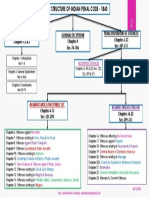

1. Circumstances affecting criminal liability

(a) Justifying circumstances

(b) Exempting circumstances

(c) Absolutory causes

(d) Mitigating circumstances

(e) Aggravating circumstances

(f) Alternative circumstances

A. Justifying Circumstances

2. Justifying circumstances are those where the act of a person is

said to be in accordance with law, so that such person is

deemed not to have transgressed the law and is free from both

criminal and civil liability. [Luis B. Reyes, The Revised Penal

Code, Book One, Nineteenth Edition, 2017, p. 150] There is

generally no civil liability, except in avoidance of greater evil or

injury where the person benefitted is the one civilly liable [REV.

PEN. CODE, art. 11 and 101].

3. There are six (6) justifying circumstances enumerated in Article

11 of the Revised Penal Code, namely:

1. (a) Self-defense;

2.

3. (b) Defense of relative;

4.

5. (c) Defense of stranger;

6.

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

2

7. (d) Avoidance of greater evil or injury;

8.

9. (e) Fulfilment of duty or lawful exercise of a right or office; and

10.

11.(f) Obedience to lawful order of a superior.

4. Victim-survivors who are found by the courts to be suffering

from the battered woman syndrome do not incur any criminal

and civil liability notwithstanding the absence of any of the

elements for justifying circumstances of self-defense under the

Revised Penal Code. As such, the Battered Woman Syndrome is

also considered as a justifying circumstance as long as at least

two cycles of violence, consisting of three phases, are duly

established by the expert testimony of psychologists or

psychiatrists. [REP. ACT NO. 9262 (2004), sec. 26, in relation to

People v. Genosa, 419 SCRA 537 (2002)]

The Battered Woman Syndrome (“BWS”) refers to a scientifically

defined pattern of psychological and behavioral symptoms

found in women living in battering relationships as a result of

cumulative abuse. [REP. ACT NO. 9262 (2004), sec. 3(c)]

5. Self-defense includes defense of one’s person or right and

requires the presence of these three (3) circumstances:

(a) Unlawful aggression;

(b) Reasonable necessity of the means employed to prevent or

repel it; and

(c) Lack of sufficient provocation on the part of the person

defending himself. [REV. PEN. CODE, art. 11(1)]

Defense of relative includes defense of the person or rights of

one’s spouse, ascendants, descendants, or legitimate, natural

or adopted brothers or sisters, or of his/her relatives by affinity

in the same degrees and those by consanguinity within the

fourth civil degree, provided that the first and second requisites

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

3

in self-defense are present and the further requisite, in case the

provocation was given by the person attacked, that the one

making the defense had no part therein. [REV. PEN. CODE, art.

11(2)]

Defense of a stranger also has the same first two requisites and

the third requisite that the person defending be not induced by

revenge, resentment or other evil motive. [REV. PEN. CODE, art.

11(3)]

6. An indispensable requisite of self-defense, defense of relative

and defense of stranger is that the victim must have mounted

an unlawful aggression against the accused. Without such

unlawful aggression, the accused cannot invoke self-defense,

defense of relative or defense of stranger as a justifying

circumstance. [People v. Olarbe, G.R. No. 227421, 23 July

2018] There could likewise be no incomplete self defense,

defense of relative or defense of stranger if there is no unlawful

aggression.

7. Unlawful aggression is of two kinds: (a) actual or material

unlawful aggression; and (b) imminent unlawful aggression.

Actual or material unlawful aggression means an attack with

physical force or with a weapon, an offensive act that positively

determines the intent of the aggressor to cause the injury.

Imminent unlawful aggression means an attack that is

impending or at the point of happening; it must not consist in

a mere threatening attitude, nor must it be merely imaginary,

but must be offensive and positively strong (like aiming a

revolver at another with intent to shoot or opening a knife and

making a motion as if to attack). Imminent unlawful aggression

must not be a mere threatening attitude of the victim, such as

pressing his right hand to his hip where a revolver was

holstered, accompanied by an angry countenance, or like

aiming to throw a pot. [People v. Olarbe, G.R. No. 227421, 23

July 2018]

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

4

There can be no self-defense, whether complete or incomplete,

unless the victim had committed unlawful aggression against

the person who resorted to self-defense. Unlawful aggression is

an actual physical assault, or at least a threat to inflict real

imminent injury, upon a person. In case of threat, it must be

offensive and strong, positively showing the wrongful intent to

cause injury -- as in this case. Thus, Suico’s act of aiming a

cocked gun at appellant is sufficient unlawful aggression.

[People v. Catbagan, G.R. Nos. 149430-32, 23 February 2004]

Unlawful aggression is an actual physical assault, or at least a

threat to inflict real imminent injury, upon a person. The test

for the presence of unlawful aggression is whether the victim's

aggression placed in real peril the life or personal safety of the

person defending himself. The danger must not be an imagined

or imaginary threat. Accordingly, the confluence of these

elements of unlawful aggression must be established by the

accused, to wit: (a) there must be a physical or material attack

or assault; (b) the attack or assault must be actual, or at least

imminent; and (c) the attack or assault must be unlawful.

As the second element of unlawful aggression will show, it is of

two kinds: (a) actual or material unlawful aggression; and (b)

imminent unlawful aggression Actual or material unlawful

aggression means an attack with physical force or with a

weapon, an offensive act that positively determines the intent of

the aggressor to cause the injury. Imminent unlawful

aggression means an attack that is impending or at the point of

happening; it must not consist in a mere threatening or

intimidating attitude, nor must it be merely imaginary, but

must be offensive, menacing and positively strong, manifestly

showing the wrongful intent to cause injury (like aiming a

revolver at another with intent to shoot or opening a knife and

making a motion as if to attack). There must be an actual,

sudden, unexpected attack or imminent danger thereof: which

puts the accused's life in real peril. [People v. Reyes, G.R. No.

224498, 11 January 2018]

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

5

8. The requisites for avoidance of greater evil or injury are:

(a) That the evil sought to be avoided actually exists;

(b) That the injury feared be greater than that done to avoid

it; and

(c) That there be no other practical and less harmful means

of preventing it. [REV. PEN. CODE, art. 11(4)]

Unlike the other justifying circumstances, there is civil liability

under this paragraph. Article 101 of the Revised Penal Code

provides that, in cases falling within subdivision 4 of Article 11,

the persons for whose benefit the harm has been prevented

shall be civilly liable in proportion to the benefit which they may

have received. The courts shall determine, in their sound

discretion, the proportionate amount for which each one shall

be liable. In this circumstance, the greater evil should not be

brought about by the negligence or the imprudence of the actor.

9. A person incurs no criminal liability when he acts in the

fulfillment of a duty or in the lawful exercise of a right or office

[REV. PEN. CODE, art. 11(5)], which have two requisites: (a) that

the offender acted in the performance of a duty or in the lawful

exercise of a duty or in the lawful exercise of a right: and (b) that

the injury or offense committed be the necessary consequence

of the due performance of such right or office. [People v. Belbes,

334 SCRA 161 (2000)]

10. People v. Ulep

G.R. No. 132547, 20 September 2000

Buenaventura Wapili went berserk and became violent,

prompting police intervention. Policemen, including accused

SPO1 Ernesto Ulep, saw Wapili armed with a bolo and a rattan

stool. SPO1 Ulep fired a warning shot and told Wapili to put

down his weapons or they would shoot him. But Wapili retorted

"pusila!" ("fire!") and continued advancing towards the police

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

6

officers. When Wapili was only about two (2) to three (3) meters

away from them, SPO1 Ulep shot the victim with his M-16 rifle,

hitting him in various parts of his body. As the victim slumped

to the ground, SPO1 Ulep came closer and pumped another

bullet into his head and literally blew his brains out.

SPO1 Ulep was convicted of murder and sentenced with

the death penalty by the trial court.

Upon automatic review in the Supreme Court, Ulep prayed

for his acquittal mainly on the basis of his claim that the killing

of the victim was in the course of the performance of his official

duty as a police officer. He also raised self-defense.

The Supreme Court rejected the defense of fulfillment of

duty after finding that its second requisite is lacking. However,

it convicted Ulep only of homicide because treachery was not

proved.

Before the justifying circumstance of fulfillment of a duty

under Art. 11, par. 5, of the Revised Penal Code may be

successfully invoked, the accused must prove the presence of

two (2) requisites, namely, that he acted in the performance of

a duty or in the lawful exercise of a right or an office, and that

the injury caused or the offense committed be the necessary

consequence of the due performance of duty or the lawful

exercise of such right or office.

SPO1 Ulep and the other police officers involved originally

set out to perform a legal duty: to render police assistance, and

restore peace and order at Mundog Subdivision where the

victim was then running amuck. There were two (2) stages of

the incident at Mundog Subdivision. During the first stage, the

victim threatened the safety of the police officers by menacingly

advancing towards them, notwithstanding SPO1 Ulep's

previous warning shot and verbal admonition to the victim to

lay down his weapon or he would be shot. As a police officer, it

is to be expected that SPO1 Ulep would stand his ground. Up to

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

7

that point, his decision to respond with a barrage of gunfire to

halt the victim's further advance was justified under the

circumstances. However, he cannot be exonerated from

overdoing his duty during the second stage of the incident -

when he fatally shot the victim in the head, even after the latter

slumped to the ground due to multiple gunshot wounds

sustained while charging at the police officers. The victim at

that point no longer posed a threat and was already incapable

of mounting an aggression against the police officers. Shooting

him in the head was obviously unnecessary.

It cannot therefore be said that the fatal wound in the head

of the victim was a necessary consequence of SPO1 Ulep's due

performance of a duty or the lawful exercise of a right or office.

However, he was convicted only of homicide because there was

no treachery. He was given also the benefit of a privileged

mitigating circumstance.

11. Cabanlig v. Sandiganbayan

G.R. No. 148431, 28 June 2005

Jordan Magat, Randy Reyes and Jimmy Valino were

arrested for robbery in Nueva Ecija by the investigating

authorities. Most of the stolen goods were recovered except for

a flower vase and a small radio. During the retrieval operation

for the unrecovered goods, Valino suddenly grabbed a police

officer’s M16 Armalite and jumped out of the jeep. Without

issuing any warning, SPO2 Cabanlig, the accused in this case,

fired one shot at Valino, followed by four more successive shots.

Valino did not fire any shot. Valino died from the wounds he

sustained.

SPO2 Cabanlig and the other police officers were charged

with murder. All were acquitted except for SPO2 Cabanlig, who

was convicted of homicide, the Sandiganbayan having found no

circumstance that would qualify the crime to murder.

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

8

SPO2 Cabanlig challenged the decision by invoking the

justifying circumstances of fulfillment of duty and self-defense/

defense of stranger.

The Supreme Court reversed the Decision and acquitted

SPO2 Cabanlig and found that Cabanlig’s acts were justified

given the circumstances.

In this case, Valino was committing an offense in the

presence of the policemen when Valino grabbed the M16

Armalite from one of the policemen and jumped from the jeep to

escape. The policemen would have been justified in shooting

Valino if the use of force was absolutely necessary to prevent

his escape. But Valino was not only an escaping detainee.

Valino had also stolen the M16 Armalite of a policeman. The

policemen had the duty not only to recapture Valino but also to

recover the loose firearm. By grabbing the policeman's M16

Armalite, which is a formidable firearm, Valino had placed the

lives of the policemen in grave danger.

The Sandiganbayan had very good reasons in steadfastly

adhering to the policy that a law enforcer must first issue a

warning before he could use force against an offender. However,

the duty to issue a warning is not absolutely mandated at all

times and at all cost, to the detriment of the life of law enforcers.

The directive to issue a warning contemplates a situation where

several options are still available to the law enforcers. In

exceptional circumstances such as this case, where the threat

to the life of a law enforcer is already imminent, and there is no

other option but to use force to subdue the offender, the law

enforcer's failure to issue a warning is excusable.

In this case, the embattled policemen did not have the

luxury of time. Neither did they have much choice. Cabanlig's

shooting of Valino was an immediate and spontaneous reaction

to imminent danger.

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

9

12. The sixth justifying circumstance is when a person acts in

obedience to an order issued by a superior for some lawful

purpose [REV. PEN. CODE, art. 11(6)]. Its requisites are:

(a) An order has been issued by a superior;

(b) The order is for a legal purpose; and

(c) The means to be used to carry out said order is lawful.

[Ambil v. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 175457, 6 July 2011]

B. Exempting Circumstances

13. There are seven (7) exempting circumstances enumerated in

Article 12 of the Revised Penal Code where a person who

commits a crime is exempt from criminal liability because of the

absence of freedom, intelligence or intent or lack of negligence.

However, he incurs civil liability, except in paragraphs 4 and 7,

Article 12 of the Revised Penal Code.

14. The exempting circumstances in Article 12 of the Revised Penal

Code, as amended by Republic Act No. 9344, include:

(a) An imbecile or insane person, unless the latter acted

1. under a lucid interval;

2.

(b) A person fifteen years or under;

3.

(c) A person over fifteen and under eighteen years, unless he

1. acted with discernment;

4.

(d) Accident;

5.

(e) Any person who acts under the compulsion of an

irresistible force;

6.

(f) Any person who acts under the impulse of an

uncontrollable fear; and

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

10

7.

(g) Any person who fails to perform an act required by law

when prevented by some lawful or insuperable cause.

15. Article 12 of the Revised Penal Code exempts from criminal

liability an imbecile or an insane person unless the latter has

acted during a lucid interval. An imbecile is exempt at all times,

while an insane person is exempt unless he acted during a lucid

interval. An imbecile is a person marked by mental deficiency

while an insane person is one who has an unsound mind or

suffers from a mental disorder. [People v. Ambal, 100 SCRA 325

(1980)]

An imbecile, within the meaning of Article 12 of the Revised

Penal Code, is one who must be deprived completely of reason

or discernment and freedom of will at the time of committing

the crime. He is one who, while advanced in age, has a mental

development comparable to that of children between two and

seven years of age. [People v. Nunez, G.R. Nos. 112429-30, 23

July 1997]

Insanity has been defined as "a manifestation in language or

conduct of disease or defect of the brain, or a more or less

permanently diseased or disordered condition of the mentality,

functional or organic, and characterized by perversion,

inhibition, or disordered function of the sensory or of the

intellective faculties, or by impaired or disordered volition."

[People v. Ambal, 100 SCRA 325 (1980), citing Section 1039,

Revised Administrative Code]

16. A child fifteen (15) years and under is absolutely exempt from

criminal liability. A child over fifteen (15) years old but below

eighteen (18) years old is also exempt from criminal liability,

unless he acted with discernment. [Rep. Act No. 9344 (2006),

sec. 6]

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

11

Under Article 12(3) of the Revised Penal Code, a minor over nine

years of age and under fifteen1 is exempt from criminal liability

if charged with a felony. The law applies even if such minor is

charged with a crime defined and penalized by a special penal

law. In such case, it is the burden of the minor to prove his age

in order for him to be exempt from criminal liability. The reason

for the exemption is that a minor of such age is presumed

lacking the mental element of a crime – the capacity to know

what is wrong as distinguished from what is right or to

determine the morality of human acts; wrong in the sense in

which the term is used in moral wrong. However, such

presumption is rebuttable. For a minor at such an age to be

criminally liable, the prosecution is burdened to prove beyond

reasonable doubt, by direct or circumstantial evidence, that he

acted with discernment, meaning that he knew what he was

doing and that it was wrong. [Jose v. People, 448 SCRA 116

(2005)]

17. The discernment that constitutes an exception to the exemption

from criminal liability of a minor under fifteen years of age but

over nine,2 who commits an act prohibited by law, is his mental

capacity to understand the difference between right and wrong

[People v. Doquena, 68 Phil. 580 (1939)] Discernment is more

than the mere understanding between right and wrong. Rather

it means the mental capacity of a minor to fully appreciate the

consequences of his unlawful act. [People v. Navarro, 51 O.G.

4062 (1955)]

18. Any person who, while performing a lawful act with due care,

causes an injury by mere accident, without fault or intention of

causing it, is exempt from criminal liability [REV. PEN. CODE, art.

11(6)].

The requisites of accident are:

(a) A person performs a lawful act;

1 Old rule

2 Old rule

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

12

(b) With due care;

(c) He causes injury to another by mere accident

(d) Without fault or intention of causing it [RPC, art. 12(4)

and Toledo v. People, 482 Phil. 292 (2004)]

19. A person invoking the exempting circumstance of compulsion

due to irresistible force admits in effect the commission of a

punishable act, and must therefore prove the exempting

circumstance by clear and convincing evidence. Specifically: He

must show that the irresistible force reduced him to a mere

instrument that acted not only without will but also against his

will. The compulsion must be of such character as to leave the

accused no opportunity to defend himself or to escape. [People

v. Licayan, G.R. No. 203961, 29 July 2015]

Under Article 12 of the Revised Penal Code, a person is exempt

from criminal liability if he acts under the compulsion of an

irresistible force, or under the impulse of an uncontrollable fear

of equal or greater injury, because such person does not act

with freedom. However, the Supreme Court held that for such a

defense to prosper, the duress, force, fear, or intimidation must

be present, imminent and impending, and of such nature as to

induce a well-grounded apprehension of death or serious bodily

harm if the act be done. A threat of future injury is not enough.

In this case, as correctly held by the Court of Appeals, based on

the evidence on record, appellant had the chance to escape

Lumbayan's threat or engage Lumbayan in combat, as

appellant was also holding a knife at the time. Thus, appellant's

allegation of fear or duress is untenable. The Supreme Court

has held that in order for the circumstance of uncontrollable

fear may apply, it is necessary that the compulsion be of such

a character as to leave no opportunity for escape or self-defense

in equal combat. Therefore, under the circumstances,

appellant’s alleged fear, arising from the threat of Lumbayan,

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

13

would not suffice to exempt him from incurring criminal

liability. [People v. Anod, G.R. No. 186420, 25 August 2009]

20. In People v. Bandian, 63 Phil 530 (1936), Valentin Aguilar saw

Josefina Bandian, who was then pregnant, went to a thicket

near her house, apparently to respond to a call of nature. A few

minutes later, he again saw her emerge from the thicket with

her clothes stained with blood, staggering and visibly showing

signs of not being able to support herself. He aided her rest in

her bed and observed that she was very weak and dizzy. Later,

Aguilar and another companion saw the body of a newborn

child in the thicket where Bandian had gone a few moments

earlier. When asked whether the baby was hers, Bandian said

yes. Bandian was charged and convicted of infanticide. The

Supreme Court reversed. The evidence certainly does not show

that Bandian, in causing her child’s death in one way or the

other, or in abandoning it in the thicket, did no willfully,

consciously or imprudently. She had no cause to kill or

abandon the baby. Bandian could not carry the child from the

thicket due to her debility or dizziness, which causes may be

considered lawful or insuperable to constitute the seventh

exempting circumstances.

C. Absolutory Causes

21. An absolutory cause is present “where the act committed is a

crime but for reasons of public policy and sentiment there is no

penalty imposed”. [People v. Talisic, G.R. No. 97961, 5

September 1997, citing Luis B. Reyes, The Revised Penal Code,

Volume I, 13th Edition, 1993, pp. 231-232]. There is generally

civil liability. There are several absolutory causes which

include:

a. The spontaneous desistance of the person who

commenced the commission of a felony before he could

perform all acts of execution [REV. PEN. CODE, art. 6(3)];

1.

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

14

b. Frustrated and attempted light felonies are not

punishable, except in crimes against persons and property

[REV. PEN. CODE, art. 7];

2.

c. Accessories are not criminally liable in light felonies [REV.

PEN. CODE, art. 16];

3.

d. Accessories who are relatives of the principal are exempt

from criminal liability [REV. PEN. CODE, art. 20];

e. Death or serious physical injuries and other physical

injuries inflicted under exceptional circumstances [REV.

PEN. CODE, art. 247];

f. Absolutory causes in qualified trespass to dwelling [REV.

PEN. CODE, art. 280];

g. Exempt persons in certain crimes against property,

specifically estafa, theft or malicious mischief [REV. PEN.

CODE, art. 332];

h. Consent or pardon in certain crimes against chastity [REV.

PEN. CODE, art. 344]; and

i. Instigation [People v. Doria, G.R. No. 125299, 22 January

1999].

22. Article 247 of the Revised Penal Code does not define an offense.

Destierro is imposed more as a protection to the accused rather

than as a punishment. [People v. Abarca, 153 SCRA 735 (1987)]

It is rather an absolutory cause which is present "where the act

committed is a crime but for reasons of public policy and

sentiment there is no penalty imposed." [People v. Talisic, G.R.

No. 97961, 5 September 1997]

23. The absolutory cause in Article 247 of the Revised Penal Code

applies only to legally married persons and can be invoked by

the innocent spouse who surprises his or her spouse in sexual

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

15

intercourse with another person and kills or inflicts physical

injuries on them in the act or immediately thereafter. It is not

applied if the spouse has promoted or facilitate the prostitution

or has otherwise consented to the infidelity of the other spouse.

[REV. PEN. CODE, art. 247 and People v. Talisic, G.R. No. 97961,

5 September 1997] This absolutory cause applies to parents

with respect to their daughters under eighteen years and their

seducers, while the daughters are living with their parents.

[REV. PEN. CODE, art. 247]

Article 247 of the Revised Penal Code states that it applies when

the guilty spouse has “sexual intercourse with another person”,

without specifying the gender of the paramour. However, in

People v. Butiong, G.R. No. G.R. No. 168932, 19 October 2011,

the Supreme Court stated that he basic element of rape is

carnal knowledge or sexual intercourse and carnal knowledge

is defined as "the act of a man having sexual bodily connections

with a woman."

24. Article 332 of the Revised Penal Code provides for an absolutory

cause in the crimes of theft, estafa (or swindling) and malicious

mischief. It limits the responsibility of the offender to civil

liability and frees him from criminal liability by virtue of his

relationship to the offended party. [Intestate Estate of Manolita

Gonzales vda. de Carungcong v. People, G.R. No. 181409, 11

February 2010]

Article 332 of the Revised Penal Code involves three crimes

against property only, namely, (a) theft, (b) estafa or swindling,

and (c) malicious mischief. It also includes three kinds of

relationships only, namely: (a) spouses, ascendants and

descendants, or relatives by affinity in the same line; (b) the

widowed spouse with respect to the property which belonged to

the deceased spouse before the same shall have passed into the

possession of another; and (c) brothers and sisters and

brothers-in-law and sisters-in-law, if living together. [REV. PEN.

CODE, art. 332]

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

16

The exemption provided here does not apply to strangers

participating in the commission of the crime. [REV. PEN. CODE,

art. 332]

There is a view that under Article 332 of the Revised Penal Code,

the term "spouse" embraces common law relation for purposes

of exemption from criminal liability in cases of theft, swindling

and malicious mischief committed or caused mutually by

spouses. The Penal Code article, it is said, makes no distinction

between a couple whose cohabitation is sanctioned by a

sacrament or legal tie and another who are husband and wife

de facto. [Valino v. Adriano, G.R. No. 182894, 22 April 2014]

The relationship by affinity between the surviving spouse and

the kindred of the deceased spouse continues even after the

death of the deceased spouse, regardless of whether the

marriage produced children or not. [Intestate Estate of Manolita

Gonzales vda. de Carungcong v. People, G.R. No. 181409, 11

February 2010]

Furthermore, the coverage of Article 332 is strictly limited to the

simple felonies mentioned therein and it does not apply where

any of the crimes mentioned under Article 332 is complexed

with another crime, such as theft through falsification or estafa

through falsification. [Intestate Estate of Manolita Gonzales

vda. de Carungcong v. People, G.R. No. 181409, 11 February

2010]

25. Entrapment in the Philippines is not a defense available to the

accused. It is instigation that is a defense and is considered an

absolutory cause. [People v. Doria, G.R. No. 125299, 22

January 1999]

There are two tests in entrapment:

a. Subjective or origin of intent test, where the focus of the

inquiry is the accused’s predisposition to commit the

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

17

offense charged, his state of mind and inclination before

his initial exposure to government agents; and

b. Objective test, where the court considers the nature of the

police activity involved and the propriety of police conduct.

The inquiry is focused on the inducements made by police

agents, on police conduct, not on the accused and his

predisposition to commit the crime.

D. Mitigating Circumstances

26. The mitigating circumstances are the following:

(a) Incomplete justifying and exempting circumstances, when

all the requisites necessary to justify the act or to exempt

from criminal liability in the respective cases are not

attendant;

(b) That the offender is under eighteen years of age or over

seventy years;

(c) That the offender had no intention to commit so grave a

wrong as that committed;

(d) That sufficient provocation or threat on the part of the

offended party immediately preceded the act;

(e) That the act was committed in the immediate vindication

of a grave offense to the one committing the felony (delito)

his spouse, ascendants, descendants, legitimate, natural

or adopted brothers or sisters or relatives by affinity within

the same degrees;

(f) That of having acted upon an impulse so powerful as

naturally to have produced passion or obfuscation;

(g) That the offender had voluntarily surrendered himself to a

person in authority or his agents, or that he had

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

18

voluntarily confessed his guilt before the court prior to the

presentation of the evidence for the prosecution;

(h) That the offender is deaf and dumb, blind or otherwise

suffering some physical defect which thus restricts his

means of action, defense, or communication with his

fellow beings;

(i) Such illness of the offender as would diminish the exercise

of the will-power of the offender without however depriving

him of consciousness of his acts;

(j) And, finally, any other circumstance of a similar nature

and analogous to those above mentioned.

27. The list of mitigating circumstances in Article 13 of the Revised

Penal Code is not exclusive as there may be other mitigating

circumstances which are of a similar nature or analogous to

those enumerated, while the list of aggravating circumstances

in Article 14 of the Revised Penal Code are exclusive.

28. Mitigating circumstances may either be ordinary or privileged.

Ordinary mitigating circumstances will result to the imposition

of the lower indivisible penalty in case there are two indivisible

penalties under Article 63 of the Revised Penal Code or of the

penalty in its minimum period in case of a divisible penalty

under Article 64 of the Revised Penal Code, if there is no

aggravating circumstance; while a privileged mitigating

circumstance may result to the lowering of the penalty by a

degree or two degrees. [REV. PEN. CODE, art. 64(5), 68, and 69]

29. Incomplete justifying or exempting circumstances may be

ordinary or privileged mitigating circumstances. When majority

of the requisites are present, these are considered as privileged

mitigating circumstances under Article 69 of the Revised Penal

Code which may lead to the reduction of the penalty by one or

two degrees; when majority of the requisites are not present,

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

19

these are considered as ordinary mitigating circumstances

under Article 13(1) of the Revised Penal Code.

30. Minority in Article 13(2) of the Revised Penal Code is an

exempting circumstance if the child is 15 years old or below or

a privileged mitigating circumstance under Article 68 of the

Revised Penal Code, which will result to a reduction of only one

degree, if the child is over 15 but below 18 years old who acted

with discernment.

31. When originally there are two or more mitigating circumstances

and no aggravating circumstance, it will be considered as a

privileged mitigating circumstance which will result to the

imposition of the penalty next lower in degree. [REV. PEN. CODE,

art. 64(5)] It does not apply if there was originally an aggravating

circumstance and offsetting was done leaving two or more

mitigating circumstances.

E. Aggravating Circumstances

32. The following are aggravating circumstances:

(a) That advantage be taken by the offender of his public

position;

(b) That the crime be committed in contempt of or with insult

to the public authorities;

(c) That the act be committed with insult or in disregard of

the respect due to the offended party on account of his

rank, age, or sex, or that it be committed in the dwelling

of the offended party, if the latter has not given

provocation;

(d) That the act be committed with abuse of confidence or

obvious ungratefulness;

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

20

(e) That the crime be committed in the palace of the Chief

Executive, or in his presence, or where public authorities

are engaged in the discharge of their duties, or in a place

dedicated to religious worship;

(f) That the crime be committed in the nighttime, or in an

uninhabited place, or by a band, whenever such

circumstances may facilitate the commission of the

offense.

Whenever more than three armed malefactors shall have

acted together in the commission of an offense, it shall be

deemed to have been committed by a band.

(g) That the crime be committed on the occasion of a

conflagration, shipwreck, earthquake, epidemic, or other

calamity or misfortune;

(h) That the crime be committed with the aid of armed men or

persons who insure or afford impunity;

(i) That the accused is a recidivist.

A recidivist is one who, at the time of his trial for one crime,

shall have been previously convicted by final judgment of

another crime embraced in the same title of this Code;

(j) That the offender has been previously punished for an

offense to which the law attaches an equal or greater

penalty or for two or more crimes to which it attaches a

lighter penalty;

(k) That the crime be committed in consideration of a price,

reward, or promise;

(l) That the crime be committed by means of inundation, fire,

poison, explosion, stranding of a vessel or intentional

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

21

damage thereto, derailment of a locomotive, or by the use

of any other artifice involving great waste and ruin;

(m) That the act be committed with evident premeditation;

(n) That craft, fraud, or disguise be employed;

(o) That advantage be taken of superior strength, or means be

employed to weaken the defense;

(p) That the act be committed with treachery (alevosia).

There is treachery when the offender commits any of the

crimes against the person, employing means, methods, or

forms in the execution thereof which tend directly and

specially to insure its execution, without risk to himself

arising from the defense which the offended party might

make;

(q) That means be employed or circumstances brought about

which add ignominy to the natural effects of the act;

(r) That the crime be committed after an unlawful entry.

There is an unlawful entry when an entrance is effected by

a way not intended for the purpose;

(s) That as a means to the commission of a crime a wall, roof,

floor, door, or window be broken;

(t) That the crime be committed with the aid of persons under

fifteen years of age or by means of motor vehicles,

motorized watercraft, airships, or other similar means;

and

(u) That the wrong done in the commission of the crime be

deliberately augmented by causing other wrong not

necessary for its commission.

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

22

33. The qualifying and aggravating circumstances must be alleged

in the complaint or information, otherwise, these cannot be

appreciated by the court even if subsequently proved during the

trial. [Rules of Court, Rule 110, sec. 8 and 9 and Sombillon v.

People, G.R. No. 175528, 30 September 2009]

34. Aggravating circumstances which in themselves constitute a

crime especially punishable by law or which are included by law

in defining a crime and prescribing the penalty therefor as well

as those which are inherent in the crime are not taken into

account for the purpose of increasing the penalty. [REV. PEN.

CODE, art. 62]

35. Aggravating or mitigating circumstances which arise from the

moral attributes of the offender or from his private relations

with the offended party, or from any other personal cause shall

only serve to aggravate or mitigate the liability of those as to

whom such circumstances are attendant; while circumstances

which consist in the material execution of the act or in the

means employed to accomplish it shall serve to aggravate or

mitigate the liability of those persons only who had knowledge

of them at the time of the execution of the act or their

cooperation therein. [REV. PEN. CODE, art. 62]

36. Special aggravating circumstances may not be offset by

ordinary mitigating circumstances and mandate that the

penalty be imposed always in its maximum period, including: (i)

penalty for complex crimes in Article 48 of the Revised Penal

Code; (ii) penalty for mistake in identity in Article 49 of the

Revised Penal Code; (iii) when the offender took advantage of his

public position in the commission of a crime in Article 62(1)(a)

of the Revised Penal Code (iv) when the offense was committed

by any person who belongs to an organized/syndicated group

in Article 62(1)(a) of the Revised Penal Code; and (v) in quasi-

recidivism in Article 160 of the Revised Penal Code.

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

23

Article 14(20) of the Revised Penal Code considers it an

aggravating circumstance when the crime be committed with

the aid of persons under fifteen (15) years of age. Section 20(C)

of Republic Act No. 9344 (2006), as amended, or the Juvenile

Justice and Welfare Act of 2006 considers this as a special

aggravating circumstance as it provides that “[a]ny person who,

in the commission of a crime, makes use, takes advantage of,

or profits from the use of children, including any person who

abuses his/her authority over the child or who, with abuse of

confidence, takes advantage of the vulnerabilities of the child

and shall induce, threaten or instigate the commission of the

crime, shall be imposed the penalty prescribed by law for the

crime committed in its maximum period."

In view of the amendments introduced by Rep. Act No. 8294 and

Rep. Act No. 10591, to Presidential Decree No. 1866, separate

prosecutions for homicide and illegal possession are no longer

in order. Instead, illegal possession of firearm is merely to be

taken as an aggravating circumstance in the crime of murder.

It is clear from the foregoing that where murder results from the

use of an unlicensed firearm, the crime is not qualified illegal

possession but, murder. In such a case, the use of the

unlicensed firearm is not considered as a separate crime but

shall be appreciated as a mere aggravating circumstance. Thus,

where murder was committed, the penalty for illegal possession

of firearms is no longer imposable since it becomes merely a

special aggravating circumstance. The intent of Congress is to

treat the offense of illegal possession of firearm and the

commission of homicide or murder with the use of unlicensed

firearm as a single offense. [People v. Gaborne, G.R. No. 210710,

27 July 2016]

37. Whatever may be the number and nature of the aggravating

circumstances, the courts shall not impose a greater penalty

than that prescribed by law, in its maximum period. [REV. PEN.

CODE, art. 64(6)]

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

24

38. The essence of treachery is the unexpected and sudden attack

on the victim which renders the latter unable and unprepared

to defend himself by reason of the suddenness and severity of

the attack. This criterion applies, whether the attack is frontal

or from behind. Even a frontal attack could be treacherous

when unexpected and on an unarmed victim who would be in

no position to repel the attack or avoid it. [People v. Pulgo, G.R.

No. 218205, 5 July 2017]

F. Alternative Circumstances

39. Alternative circumstances are those which must be taken into

consideration as aggravating or mitigating according to the

nature and effects of the crime and the other conditions

attending its commission. They are the relationship,

intoxication and the degree of instruction and education of the

offender. [REV. PEN. CODE, art. 15]

40. The intoxication of the offender shall be taken into

consideration as a mitigating circumstance when the offender

has committed a felony in a state of intoxication, if the same is

not habitual or subsequent to the plan to commit said felony;

but when the intoxication is habitual or intentional, it shall be

considered as an aggravating circumstance. [REV. PEN. CODE,

art. 15]

CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING LIABILITY DAN P. CALICA

You might also like

- Colouring Book Mandalas and MosaicsDocument76 pagesColouring Book Mandalas and Mosaicsszulamit halasi100% (3)

- 22 Chapter 2 Section 141-To-143Document1 page22 Chapter 2 Section 141-To-143Kenya Monique Huston ElNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law JDDocument23 pagesCriminal Law JDCooksNo ratings yet

- Art. 11 of RPCDocument168 pagesArt. 11 of RPCCastrel AcerNo ratings yet

- Claw 3 Notes 3Document11 pagesClaw 3 Notes 3Nicko SalinasNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law JEMAADocument117 pagesCriminal Law JEMAAGalindo, Hans DavidNo ratings yet

- CRIM Slides EditedDocument6 pagesCRIM Slides EditedApril Kirstin ChuaNo ratings yet

- Arts.11, 12 and 15Document28 pagesArts.11, 12 and 15Rodelyn SagamlaNo ratings yet

- Notes On Art. 11 of The Revised Penal CodeDocument12 pagesNotes On Art. 11 of The Revised Penal CodelemonnerriNo ratings yet

- Self-Defense Research 04212016Document4 pagesSelf-Defense Research 04212016KriziaItaoNo ratings yet

- Group 3 Report Part 1 and 2Document155 pagesGroup 3 Report Part 1 and 2Patricia Ortega50% (2)

- Kenneth Martin E. Dela Cruz - Assignment#1 - Section BDocument7 pagesKenneth Martin E. Dela Cruz - Assignment#1 - Section BKenneth Martin E. Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Art 11 Justifying CircumstancesDocument30 pagesArt 11 Justifying CircumstancesJabami YumekoNo ratings yet

- Crim - PimentelDocument98 pagesCrim - PimentelLirio IringanNo ratings yet

- Crim Law ReviewerDocument28 pagesCrim Law ReviewerJenny Reyes100% (1)

- Self-Defense JurisprudenceDocument4 pagesSelf-Defense Jurisprudencejessi berNo ratings yet

- Essential Points On Circumstances Affecting Criminal LiabilityDocument8 pagesEssential Points On Circumstances Affecting Criminal LiabilityRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- BP 22 Is Malum ProhibitumDocument4 pagesBP 22 Is Malum ProhibitumJade Marlu DelaTorreNo ratings yet

- Justifying and Exempting CircumstancesDocument6 pagesJustifying and Exempting CircumstancesRophelus GalendezNo ratings yet

- Kenneth Martin E. Dela Cruz - Assignment#1 - Section BDocument8 pagesKenneth Martin E. Dela Cruz - Assignment#1 - Section BKenneth Martin E. Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Crim MidtermsDocument28 pagesCrim MidtermsSunshine RubinNo ratings yet

- Crim 1 - 2 Chapter 2: Justifying Circumstances and Circumstances Which Exempt From Criminal Liability Circumstances Affecting Criminal LiabilityDocument3 pagesCrim 1 - 2 Chapter 2: Justifying Circumstances and Circumstances Which Exempt From Criminal Liability Circumstances Affecting Criminal LiabilityLuis RetananNo ratings yet

- Justifying Circumstances: / January 28, 2010Document8 pagesJustifying Circumstances: / January 28, 2010Mayela Lou AdajarNo ratings yet

- Notes On Crim. Law Review Part 2Document11 pagesNotes On Crim. Law Review Part 2Mayett LarrosaNo ratings yet

- People Vs Dulin June 29 2015Document19 pagesPeople Vs Dulin June 29 2015KM HanNo ratings yet

- Article 11 RPCDocument53 pagesArticle 11 RPCRuffa mae PortugalNo ratings yet

- Art. 11 Criminal Law ReviewerDocument13 pagesArt. 11 Criminal Law ReviewerTeresa CardinozaNo ratings yet

- WEEK 1.2 AssaultDocument5 pagesWEEK 1.2 AssaultammarizvandiarNo ratings yet

- Justifying CicumstancesDocument14 pagesJustifying CicumstancesPatrick AlcanarNo ratings yet

- 2010 Updates in Criminal LawDocument114 pages2010 Updates in Criminal LawEller-JedManalacMendozaNo ratings yet

- Reply AffidavitDocument7 pagesReply Affidavitnoel sincoNo ratings yet

- JEMAADocument7 pagesJEMAAYanyan De LeonNo ratings yet

- Crim Law FlashcardDocument13 pagesCrim Law FlashcardLeoncio DanielNo ratings yet

- Sgt.-Real, Position PaperDocument9 pagesSgt.-Real, Position PaperAldrinNo ratings yet

- ART 4 RPC Felonies and Circumstances Affecting Criminal LiabilityDocument39 pagesART 4 RPC Felonies and Circumstances Affecting Criminal LiabilityJewel Francine PUDESNo ratings yet

- RPC Art 11-15Document22 pagesRPC Art 11-15Van Openiano0% (1)

- Notes On Crim. Law Review MidtermDocument24 pagesNotes On Crim. Law Review MidtermMayett LarrosaNo ratings yet

- Article 11 Justifying Circumstances AidDocument12 pagesArticle 11 Justifying Circumstances AidMercy LingatingNo ratings yet

- 10th Reading Assignment (Crim)Document6 pages10th Reading Assignment (Crim)JB JuneNo ratings yet

- Justifying CircumstancesDocument23 pagesJustifying CircumstancesJhayvee Garcia100% (1)

- Trial Memorandum - Self-DefenseDocument18 pagesTrial Memorandum - Self-DefenseSiobhan RobinNo ratings yet

- LectureDocument5 pagesLecturePaul Angelo 黃種 武No ratings yet

- People vs. OlarbeDocument14 pagesPeople vs. OlarbeSinha ElleNo ratings yet

- Modifying CircumstanceDocument37 pagesModifying CircumstanceMae Ann Joy LamentaNo ratings yet

- Self DefenseDocument8 pagesSelf DefenseFrancis OcadoNo ratings yet

- Self DefenseDocument8 pagesSelf DefenseFrancis OcadoNo ratings yet

- Campanilla Lectures PartDocument8 pagesCampanilla Lectures PartJose JarlathNo ratings yet

- Other Circumstances/Factors Which Affect Criminal LiabilityDocument4 pagesOther Circumstances/Factors Which Affect Criminal LiabilityJazireeNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law - Justifying CircumstancesDocument9 pagesCriminal Law - Justifying CircumstancesAndrea Felice AbesamisNo ratings yet

- Just and Exemp RevDocument20 pagesJust and Exemp RevRimvan Le SufeorNo ratings yet

- Par 1. Self-Defense: Marlo C. Manuel L-1900166Document21 pagesPar 1. Self-Defense: Marlo C. Manuel L-1900166Marlo Caluya Manuel100% (1)

- Versus-Criminal Case No.: Counter-AffidavitDocument6 pagesVersus-Criminal Case No.: Counter-AffidavitJan Paul CrudaNo ratings yet

- Art 11 JustifyingDocument6 pagesArt 11 JustifyingYanne AriasNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Last Minute Tips 2018Document14 pagesCriminal Law Last Minute Tips 2018Jimcris Posadas HermosadoNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law (Caguioa Notes)Document42 pagesCriminal Law (Caguioa Notes)Jeadic St. MoniqueNo ratings yet

- CRIM 1 CASE DIGEST - CORPIN - CRL1 - JDNT-1B1 - Felonies - Part2Document11 pagesCRIM 1 CASE DIGEST - CORPIN - CRL1 - JDNT-1B1 - Felonies - Part2JemNo ratings yet

- Module 5 in Crim Law.2nd SemDocument45 pagesModule 5 in Crim Law.2nd SemNicoleNo ratings yet

- Criminal LDocument58 pagesCriminal LbilliatlearnmoreNo ratings yet

- Nacnac V. PeopleDocument6 pagesNacnac V. PeopleSean Bofill-GallardoNo ratings yet

- Ustifying Ircumstances: Ricky Russell Paul Obienda ValbarezDocument16 pagesUstifying Ircumstances: Ricky Russell Paul Obienda Valbarezlkristin0% (1)

- General Defences in Criminal Law IntoxicationDocument19 pagesGeneral Defences in Criminal Law IntoxicationPapah ReyNo ratings yet

- A I S L: Pplication of The Ndeterminate Entence AWDocument6 pagesA I S L: Pplication of The Ndeterminate Entence AWmirNo ratings yet

- Executive DeptDocument19 pagesExecutive DeptmirNo ratings yet

- Afulugencia vs. MetrobankDocument15 pagesAfulugencia vs. MetrobankmirNo ratings yet

- Duque vs. YuDocument13 pagesDuque vs. YumirNo ratings yet

- Disini V SandiganbayanDocument34 pagesDisini V SandiganbayanmirNo ratings yet

- 1 Saguisag Case July 26Document48 pages1 Saguisag Case July 26mirNo ratings yet

- Cenntral Azucarera de Bais Vs Heirs of ApostolDocument22 pagesCenntral Azucarera de Bais Vs Heirs of ApostolmirNo ratings yet

- Ang Lad Lad Vs ComelecDocument99 pagesAng Lad Lad Vs ComelecmirNo ratings yet

- R 128 To 133 Case Doctrines On EvidenceDocument105 pagesR 128 To 133 Case Doctrines On EvidencemirNo ratings yet

- Consolidate Remedial Law Review 2 Transcribed Notes: Provisional Remedies To Special ProceedingsDocument75 pagesConsolidate Remedial Law Review 2 Transcribed Notes: Provisional Remedies To Special ProceedingsmirNo ratings yet

- Phil. Health vs. Our Lady of Lourdes HospitalDocument14 pagesPhil. Health vs. Our Lady of Lourdes HospitalmirNo ratings yet

- People Vs WebbDocument31 pagesPeople Vs WebbmirNo ratings yet

- Human Rights Violation by Police in IndiaDocument18 pagesHuman Rights Violation by Police in IndiaNitisha GeedNo ratings yet

- IJAL Volume 7 Issue 2 Ajar RabDocument20 pagesIJAL Volume 7 Issue 2 Ajar RabAdrin AshNo ratings yet

- 121 20020214 Jud 01 08 en PDFDocument37 pages121 20020214 Jud 01 08 en PDFCalMustoNo ratings yet

- Constitution in Nutshell PDFDocument19 pagesConstitution in Nutshell PDFel capitanNo ratings yet

- SealandDocument4 pagesSealandHansel Jake B. Pampilo100% (1)

- Code of Mechanical Engineering Ethics in The PhilippinesDocument24 pagesCode of Mechanical Engineering Ethics in The PhilippinesJan Lorenz100% (1)

- Renvoi: (Doctrine, Concept, History, Advantages and Disadvantages)Document12 pagesRenvoi: (Doctrine, Concept, History, Advantages and Disadvantages)Qadir JavedNo ratings yet

- Exercise - The Indian ConstitutionDocument4 pagesExercise - The Indian ConstitutionSameer SurlaNo ratings yet

- Tecnogas Philippines Manufacturing Corp. vs. Court of AppealsDocument17 pagesTecnogas Philippines Manufacturing Corp. vs. Court of AppealsCarrie Anne GarciaNo ratings yet

- Duty of Care (I) SlidesDocument35 pagesDuty of Care (I) SlidesShabab TahsinNo ratings yet

- Instruction HandoutsDocument8 pagesInstruction HandoutsTroy WelchNo ratings yet

- What Is TaekwondoDocument10 pagesWhat Is TaekwondoGrace JPNo ratings yet

- Case DigestsDocument90 pagesCase DigestsMicaela Dela PeñaNo ratings yet

- T. Sareetha v. T. Venkata SubbaiahDocument16 pagesT. Sareetha v. T. Venkata SubbaiahSreenath NamboodiriNo ratings yet

- Battered Woman Syndrome The Justifying CDocument9 pagesBattered Woman Syndrome The Justifying CcharmssatellNo ratings yet

- People vs. MendozaDocument6 pagesPeople vs. MendozaDi ko alamNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 1 - Criminal LawDocument27 pagesTutorial 1 - Criminal LawRaphael Karasu-ThirdNo ratings yet

- People vs. Del RosarioDocument11 pagesPeople vs. Del RosarioIrish Marie CabreraNo ratings yet

- The Criminal Procedure (Identification) Bill 2022Document6 pagesThe Criminal Procedure (Identification) Bill 2022Abhishek BiswalNo ratings yet

- People V MalunsingDocument3 pagesPeople V MalunsingRamchand CaitorNo ratings yet

- Malfeasance, Misfeasance and NonfeasanceDocument1 pageMalfeasance, Misfeasance and Nonfeasanceeaglelegal67% (3)

- Team Code-R24: ICC Trial ChamberDocument28 pagesTeam Code-R24: ICC Trial ChamberShikhar SrivastavNo ratings yet

- EthicsDocument13 pagesEthicsJayc ChantengcoNo ratings yet

- The Lotus CaseDocument5 pagesThe Lotus Caseraul_beke118No ratings yet

- ContractsDocument14 pagesContractsNikunj sikariaNo ratings yet

- Introductory Provisions Chapter-1,2 & 3 General Exceptions Chapter-4 Sec-76-106 Penal Provisions of Offences Chapter-5-23 Sec-107-511Document1 pageIntroductory Provisions Chapter-1,2 & 3 General Exceptions Chapter-4 Sec-76-106 Penal Provisions of Offences Chapter-5-23 Sec-107-511KARTHIKEYAN MNo ratings yet

- What Is Law - ParanjapeDocument3 pagesWhat Is Law - ParanjapeKushaal JadhavNo ratings yet

- 03 TOM Civil Law Reviewer - PagesDocument927 pages03 TOM Civil Law Reviewer - PagesDee EismaNo ratings yet