Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 87.222.72.175 On Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 87.222.72.175 On Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

Uploaded by

Renato PaladeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 87.222.72.175 On Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 87.222.72.175 On Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

Uploaded by

Renato PaladeCopyright:

Available Formats

HOUSING AND SPATIAL POLICIES IN THE SOCIALIST THIRD-WORLD

Author(s): Roy Darke

Source: The Netherlands Journal of Housing and Environmental Research , 1989, Vol. 4,

No. 1, Special Issue 'Housing in the Third-World: self-help and governmental

programmes' (1989), pp. 51-66

Published by: Springer

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43932850

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/43932850?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Netherlands Journal of Housing and Environmental Research

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOUSING AND SPATIAL POLICIES IN THE SOCIALIST THIRD-WORLD

Roy Darke

Introduction

The intention of this paper is to introduce a study of shelter and settlement

policies in the Socialist Third-World. In the main body of the article a de-

scriptive format is followed which owes a debt to previous comparative work

undertaken by the International Institute for Environment and Development

(Hardoy and Satterthwaite, 1981). The present paper extends the coverage of

their valuable study by consideration of housing and settlement policies in a

number of developing nations that have professed and pursued socialist aims

and principles. Of the seventeen countries covered in the IIED survey only

Tanzania might be considered to appropriately fall within the spectrum of

the present study. The current study of socialist Third World policies is at an

early stage and this paper should therefore be seen as a contribution to work

in progress. The familiar difficulty of obtaining accurate and up-to-date in-

formation from nations in the developing world is compounded by the sensi-

tivity that the leadership in such countries often have with respect to the

provision of statistical information. The contents of the paper are, there-

fore, eclectic in relying on previous studies and the help of others who have

had first-hand experience within the chosen countries. Any omissions and

misunderstandings must be the present author's responsibility. The intention

of the paper is to go beyond the descriptive and to raise a number of general

issues about the approach and policies towards housing and settlement in

socialist development.

Defining socialism

An immediate issue in setting out on this task is to define what is meant by

socialist and, therefore, to establish a rationale for the choice of case ex-

amples. Socialism and associated terms cover a broad spectrum of meaning

and some categorisations of socialist nations have included questionable and

marginal cases(l).

Wiles and Smith in their work on the New Communist Third- World in-

clude 'those developing countries that have recently proclaimed a Marxist-

Leninist form of government' (Wiles, 1981: 13). Yet, they recognise the

shades of difference by adopting a four-fold classification of communist

nations.

These range from:

Group 1: nations with full membership of the Council for Mutual Economic

Assistance (CMEA or COMECON).

Neth. J. of Housing and Environmental Res., Vol. 4 (1989) No. 1.

51

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Group 2s countries that are recognised as communist but who are not

members of CMEA.

Group 3s countries whose leadership has professed allegiance to Marxist-

Leninism.

Group 'Doubtful cases1.

They include within Group 1 the European 'core1 and non-European members

of CMEA such as Mongolia, Cuba, and Vietnam. In Group 2 are recognised

socialist/communist nations which remain outside the direct influence of the

Soviet Union (China, North Korea). Group 3 is considered to be the NCTW

proper: Angola, Mozambique, PDR, Yemen, and Ethiopia. The doubtful cases

include Madagascar, Benin, Congo, and Guyana.

Traditionally, communism has been seen as a stage beyond socialism

(Deacon, 1983) where the state has 'withered away', alienation has been

eliminated, where the means to life are distributed according to need, where

exchange value has given way to use value and where hierarchical divisions

of labour have given way to non-hierarchical relationships in work. Socialism

is therefore seen as a transitional stage. White has recognised the dynamics

of socialist development by considering the term socialist to be too diffuse

and bland for an accurate classification of nations (White et al., 1983: 2). He

decides on a distinction between 'proto-socialist', to indicate engagement in

the transition and 'state-socialist', to indicate a centralised form of ad-

ministration found in countries adopting Soviet-styled models of planning and

development. For White, full socialism is 'marked by an absence of classes

and the state, political democracy and conscious control of the social eco-

nomy by the associated producers' (ibid) which would appear to correspond to

the traditional definition of communism adopted by Deacon.

Slater outlines four perspectives on socialism which accept a broader

definition than one based on strict allegiance to Marxist-Leninism (Slater,

1986s 157-163). Firstly, socialism can be seen as a state-led development of

social welfare programmes, income redistribution, the promotion of social

justice, and limited nationalisation in key economic sectors. However, Slater

sees these as reformist measures, rather than evidence of transition, with a

more appropriate label of 'social democracy'.

A second definition (and grouping of nations) is where some elements

of social democratic reform are pursued, where imperialism is denounced

and radical nationalism is adopted (suggested examples are Algeria, Tanza-

nia, Zimbabwe). Slater believes that failure to sustain 'a revolutionary

mobilization of popular forces and the establishment of a genuinely indepen-

dent political base' (ibids 158) disqualifies this second set of nations from

strict categorisation as socialist.

The Leninist model underlies his third definition of socialism in giving

priority to 'production, party, and the dictatorship of the proletariat', usually

after the revolutionary seizure of power.

A common criticism of the authoritarianism of the Leninist model and

the recent growth of more libertarian, democratic forms of socialism sug-

gests a foirth grouping/definition which guarantees politiceli pluralism, pop-

ular control, arri the elimination of all forms of alienation (including presum-

ably alienation from the centralised state apparatus found in some Marxist-

Leninist (M-L) contexts).

The most recent contribution to the definitional debate is provided by

a collection of essays on urban development and the space economy in the

socialist third-world (Forbes and Thrift, 1987). They implicitly agree with

the broad approach taken by Slater in believing that membership of group-

ings such as COMECON is not a sufficient condition for labelling countries

52

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

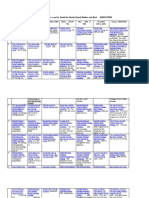

TABLE 1. Basic Data: Case Study Nations

Nicaragua Cuba

Official name: Republic of Republic of Cuba

Nicaragua

Established: 19 July 1979 1 January 1959

Population: 2.82 million 9.84 million (1982)

Land area: 128,875 sq km 114,524 sq km

Capital: Managua 1 million (1979) La Habana 2 million (1977)

Urban pop: 50.55% (est) 65% (1980)

GNP per capita: US$ 867 (1977) US$ 753 (1977)

Vietnam China

Official name: Socialist Republic of Peoples Republic of

Vietnam China

Established: 2 July 1976 (!) 1 October 1949

Population: 57.02 million (1983) 1032 million (1982)

Land area: 329,566 sq km 9.56 million sq km

Capital: Hanoi 2.6 million (1979) Beijing c.8 mill. (1977)

Largest city Ho Chi-

Minh-Ville, formerly

Saigon 3.4 million

Urban pop: 23% (1980) 25% (1980)

GNP per capita: US$ 160 (1977) US$ 413 (1977)

Mozambique Tanzania

Official name: Peoples Republic of United Republic of

Mozambique Tanzania

Established: 25 June 1975 26 April 1964

Population: 13.14 million (1983) 19.74 million (1983)

Land area: 799,380 (!) sq km 945,490 sq km

Capital: Maputo 755,000 (1980) Dar es Salaam 800,000

Urban pop: 9% ( 1 980) c. 1 0%

GNP per capita: US$ 136 (1977) GNP per capita: US$ 210

as socialist. Their main additional offering to the debate is to explicity

identify the structural features of, a) a break from the dominance of private

capital in the economy and an undermining of the hegemony of individualism

and market freedom and, b) concrete evidence of transition and transforma-

tion towards socialist ends (such as the nationalisation of economic sectors).

Thus, a kind of consensus emerges from this brief review about how it

is possible to classify socialist countries in the developing world. In addition

to the two structural features classified by Forbes and Thrift we could add

other factors such as some degree of centralised planning and control over

the economy, the strength of external links and relations with other commu-

nist/socialist nations as well as pursuit of social justice, greater equality and

the set of structural and ideological factors offered by Deacon.

Marginal cases (such as Tanzania) do create difficulties but the division

between M-L nations and those countries whose socialist aims include polit-

ical pluralism and popular power is the principal cleavage adopted in the

following review.

For reason of seeking as broad a coverage as possible we have chosen

to consider pairs of socialist developing countries from the major continents.

53

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Thus, Cuba and Nicaragua are included from Latin America/Central Ameri-

ca/Caribbean, Mozambique and Tanzania from Africa, and Vietnam and

China from Asia. In each case the first named from each continent is con-

sidered to be the tiarder' example with respect to Marxist-Leninist ideas and

the second-named country is considered to have a more pluralistic approach

to change. Further complications are encountered given that the dynamics of

economic change and world politics as well as internal developments in the

countries studied create shifts and variations in the key factors over time.

Lack of space limits the extent to which it has been possible to include

background information on each of the six nations. Where basic information

is available it is included Table 1.

The Americas

Cuba

Housing Policy. Housing policy in Cuba has passed through a number of

phases since the beginning of the revolution in 1959. Several phases of policy

have been identified (Hamberg, 1986).

In the earliest period, housing was identified as a social service. Early

reforms abolished private renting (with compensation for former landlords)

and established an ultimate objective of making housing available as part of

the 'social wage1 at no cost to residents. The 1960 Urban Reform Law turned

private tenants in the cities into owner occupiers (by using rent payments as

a contribution to amortization). Under this legislation individuals were not

permitted to own more than one permanent home. Rents were also controll-

ed by the State at levels which did not exceed 10% of household income. At

the same time government tenants were given long-term leases on the prin-

ciple of usufruct. Sales of residential property were possible but at govern-

ment set prices. The government indicated an intention to act as the main

agent for improving housing conditions and dealing with inherited housing

problems. A large state construction-sector was proposed and a self-help

programme for relocation and improvement of urban shantytown was iden-

tified. However, intentions did not match performance. The state construc-

tion sector was dogged by shortages of building materials caused by the US

economic blockade. From 1961 priority was given to the building of factories

and schools. However, even in this early period a start was made on the task

of narrowing the gap between town and country with respect to housing con-

ditions. This was to be achieved by means of the rural settlements pro-

gramme where the state began to build small 'new towns1 linked to agricul-

tural production, mining, and textiles.

The second phase of housing policy in Cuba (196*^-1970) saw the pro-

duction of homes even more heavily subordinated to the priority for in-

creased industrial production and to improvements in the national economic

position. Infrastructure and 'directly productive' investments were given

priority. On the state-housing front shortages of labour and materials gave

an impetus to the use of lightweight concrete prefabricated systems and

experimentation with large wall panel systems from Eastern Europe. The

average annual production of homes in the state sector over the period 1959-

1971 was 8,300 units.

Greater priority was given to housing again in national planning in the

period from 1971 to 1975. Microbrigades were introduced, being teams of

workers drawn from economic sectors and enterprises (on a 10% ratio) to

build housing for themselves and co-workers. Co-workers undertook to main-

tain manufacturing output and productivity as a commitment to the revolu-

tion with the incentive of future improvements in their housing circum-

5k

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

stances. Many large scale urban and rural housing-projects were completed

during this period. The average annual construction of housing by the state,

including the use of microbrigades, was 16,200 units for this period.

Output of housing by the State began to improve considerably after

1975. The main urban centres saw much of this increased production. The

question of a policy for urban slums and shantytown began to be seriously

addressed as more modern housing units became available. State construc-

tion rose to close on an average of 5 0,000 units p.a. in the period 1976-1980.

Whilst industrialised methods of building were still favoured, appreciation of

some of the problems deriving from the use of unskilled microbrigades led

back towards trained/skilled state construction-teams. The particular prob-

lems of poor workmanship, and future maintenance caused concern. Greater

emphasis on rural housing programmes was given in the late 1970s by pro-

motion of agricultural and rural co-operatives which took on responsibility

for housing as well as production.

The early 1980s saw further increases in housing production and the

provision of basic services. The 1981 census showed that self-build continued

to represent a high proportion of output. Official recognition of self-build

followed despite government disquiet (particularly because self-build con-

tributes to further low density urban sprawl and cuts across rural settlement

policies by completion of isolated buildings in the countryside). Legislation in

late- 1984 authorised low interest loans for self-build housing. In addition,

this decree extended home ownership by allowing tenants in state housing to

use their rent payments to amortise the cost of the dwelling. Sales, ex-

changes, and the inheritance of property were opened up to a broader form

of distribution.

Land. Urban land and property have not been nationalised in Cuba but capi-

talist ownership has been eliminated through the State exercising control

over prices at exchange. The State also has first option to buy and

'redistribute1 land and property when transactions occur. Castro has said that

individual home ownership is not incompatible with socialism, in stating that

a socialist state 'can give homes for free' (Jenness, 1985: 297).

Settlement Policy. Much has been written about Cuba's efforts to break the

urban dominance of Havana with respect to resource use. In the mid- to late-

1960s the productive emphasis on agriculture, and particularly the produc-

tion target of 1 million tons of sugar for 1970, gave added point to the

revolutionary committment to break the 'exploitative' hold of the capital.

Havana had become associated with corruption and tourism. Rural develop-

ment on the other hand was seen as a powerful element in national develop-

ment and fostering redistribution. Decentralisation from the cities and the

urbanisation of the countryside (via the new- towns programme) were follow-

ed as means to social and economic ends compatible with socialismi). With

the failure to meet the 10 million ton sugar target and the massive disrup-

tion caused to other sectors of the economy by attempting this level of out-

put it was recognised that the cities had a significant part to play in the

economy. In particular, the cities were seen as sites for essential skilled

labour, industrial production, and exchange.

The aim to break down the separation of town and country (encapsu-

lated in Castro's proposal for 'a minimum of urbanism and a maximum of

ruralism') and concern at the deformities of urban concentration have more

recently been tempered by the promotion of a more rational use of resour-

ces. This aim recognises the various contributions that agricultural pro-

55

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

duction and urban-based enterprises can make to economic development.

Current policy includes the green-belt programme (bringing agricul-

tural production closer to the capital), the new-towns programme in the

countryside, the promotion of an urban settlement network and hierarchy

and the widespread transformation of education, welfare and political or-

ganisation (particularly in the rural areas).

Nicaragua

Housing policy. Housing was identified as a third welfare priority (after

health and education) in the programme for social reconstruction begun by

the Sandinistas after 1979. The Ministry of Housing and Human Settlement

(MINVAH) has worked within a broad set of objectives which have been

summarised as:

1. Giving priority to housing provision on the basis of need.

2. Redressing inequalities between regions and between urban and rural

areas.

3. Expanding the role of the State in housing (by both

indirect support).

4. The promotion of popular participation in the proce

vision.

5. Reduction of technological dependence on imports of building materials,

machinery, etc.

6. Changing the institutional and financial context within which housing is

provided.

A series of home building measures has been pursued ranging from complete

housing-units built by the government (housing complexes), through provision

of basic resources - land, services, technical advice, prefabricated building

elements or, building materials - to self-builders (materials bank scheme)

and plot allocation (progressive urbanisation). As the war situation (including

trade embargoes) has deepened the economic pressures on Nicaragua so the

emphasis in housing policy has been moved increasingly to schemes of pro-

gressive urbanisation, leaving state built housing to be targeted on priority

economic projects (housing for industrial workers) and the resettlement of

vulnerable campesinos into hamlets in the war zones. Self-build activity is

well organised through the Sandinista Defence Committees (CDS) which

operate at neighbourhood level to provide a range of self-help and co-

operative services (health, education, distribution of goods, etc.).

Land. Abandoned and underused agricultural land was expropriated by the

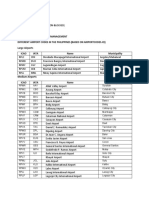

TABLE 2. Annual Housing Output, Nicaragua, 1980-1984.

1980 1981 1982 1983 1984

Housing

complexes 1146 2006 3215 3128 1017

Materials

Bank - 202 349 1322 2382

Progressive

Urbanisation - 854 8810 5814 4281

Total 1146 3062 12374 10264 7680

56

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

State in the early days of the revolution although a mixed tenure system has

been maintained (in line with the national objectives of a mixed economy and

political pluralism). In Managua waste land and urban subdivisions where

private owners had exploited tenants in the past were also expropriated by

the State. Land title has been given extensively to agricultural and urban

households in these circumstances with inheritance being passed on within

families but legal restrictions being exercised over market exchange.

Settlement policy. The intention to create a national urban system, to

extend town planning and controls over spatial development, and the decen-

tralisation of the control and administration of urban services represent

elements of a spatial policy which is concerned to achieve greater territorial

justice between parts of the country and to ensure universal access to basic

needs. Urban dominance and the low density of population in rural areas pose

a considerable task in achieving these aims. In 1982 the country was divided

into regions and special zones. A national strategy pointed out the dangers of

the continued 'force for urbanisation1, leading to a proposal for a national

urban system (SUN). The system proposes an urban hierarchy within regions

as a step to 'ordered, systematic growth1 within a strategy of fwell balanced,

fully co-ordinated ... national development1. The linking of economic and

physical development is to be achieved through regional plans, sustained

through the preparation of urban plans (a number of which have been com-

pleted, including a plan for the capital). In addition, a basic system of

development control and regulation of building standards was introduced in

1979. A third means to attempt to break the domirance of Managua is the

decentralisation of State administration and policy making. Under the 1986

constitution a system of elected local government is to be introduced and

Ministries have already begun decentralising some activities to the regions.

Asia

Vietnam

Housing policy. Housing conditions are particularly acute in the urban

centres of Vietnam. For example, it has been estimated that 17,000 housing

units were destroyed by the bombing of Hanoi, and after the withdrawal of

US troops the re-entry of people into the cities exacerbated problems of

overcrowding and poor living-conditions. An average living space of 1.5 m 2

per person has been identified in central Hanoi (Nguyan due Nhuan, 1984:

83). Housing (including low-rise flats) has gone up on the outskirts of Hanoi

which provides an average of 3m2 per person in the outer suburbs but the

comparison with conditions in the large southern city of Ho Chi -Minh- Ville

(where average housing floor space is 14 m2 per person) shows the wide re-

gional disparity that has developed over time. Urban housing is not a national

priority; is the greatest policy emphasis is being given to agricultural

production and rural development.

Reliance on self-sufficiency, and lack of resources, have meant that

housing provision in the countryside has principally been vested in local com-

mittees who take responsibility for home building and improvement. This

responsibility extends into the indigenous production of building materials.

Appleton records the local manufacture of baked-earth bricks and tiles on a

collective basis as improvements over wattle and daub walling for rural

housing (Appleton, 1983s 273).

State involvement in housinģ principally relates to the de-urbanisation

policies intended to relocate peasants out of the cities (particularly southern

cities) and into rural areas in order to boost agricultural production. Housing

57

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

loans have been granted to peasants moving back onto the plains around Ho

Chi -Mi nh- Ville and efforts to develop new agricultural production (e.g. on

tea and cotton plantations in the Central Highlands) are being pursued by

means of provision of temporary housing and basic services (such as clean

water and access roads).

Land* Land reform in Vietnam commenced in the North in the early 1950s. A

five-fold classification of tenure was used in the process of redistribution.

The classes ranged from large non- working landlords to landless peasants.

Local land reform committees controlled redistribution giving no household

more land than they could individually work. The resulting distribution gave

only sufficient cultivable land for a meagre subsistence so that collectivisa-

tion was taken as the appropriate next step to greater equalisation. From

mid 1958 to the 1960s the transfer of land ownership from individual owner

to group ownership represented the first major step to decentralised and col-

lective management of the national economy. Co-operatives were formed

(based on the Chinese model).

Co-operative development has taken a relatively long time to com-

plete. Initially peasants who pooled their land for collective cultivation were

paid a total dividend based on the size of their contributed land, other

capital inputs and their labour power. By 1967 in the North 25% of peasants

were in 'high level1 co-operatives (where all the means of production are

collectively owned) and 10% were in 'low level1 co-operatives (where there is

some shared used of land and tools but the land remains in individual owner-

ship) (Forbes and Thrift, 1987: 105).

Settlement Policy. The decentralisation of agricultural production with the

aim of self-sufficiency in food (as a contribution to the war effort) was cen-

tral to the military victory. The importance of this strategy has been follow-

ed through by post-war policies of social equality and a spatially even

approach to rural development. This policy has been applied in South Viet-

nam since 1975.

Socialist Vietnam aims to eliminate economic exploitation and raise

standards of living particularly in the countryside, in order to achieve

equality. Industrialisation associated with agricultural production has been

pursued to avoid 'urban-rural dualism'. The means adopted is the consolida-

tion of agro-industrial units in the countryside with linked strategies and

products.

The strategy of integrated rural development has been accompanied by

'de-urbanisation' particularly in the South. State support has been given (in

the form of transport and subsistence, housing loans, etc.) to persuade

refugees to return to their former villages and return to agricultural or

industrial production in the rural areas. Large numbers have been relocated.

Despite Western concern about this programme (by criticism of 'forced re-

location') 30% of households relocated into the countryside of the Mekong

Delta between 1976 and 1980 had formed co-operatives and were integrated

into national development policies (Murray and Picha, 1982: 262).

A major element of the de-urbanisation policy has been the creation of

new villages and the upgrading of existing regional and district centres.

Vietnam has been structured administratively into 500 districts below 35

provinces. Districts vary in size with a population of 100,000 - 150,000 as a

norm. District centres are the central elements in the process of integrated

rural development and are prioritized in the distribution of commodities arid

services (such as reading materials, films, touring theatre companies, etc.)

58

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

to increase their attractiveness and redress urban-rural imbalances (Apple-

ton, 1983).

China

Housing Policy. Housing provision was considered to be chiefly the responsi-

bility of the state from the early years of the revolution. In this 'low wage1

economy housing was identified as an element of the social wage. Provision

was either through municipal authorities (in urban areas) or through the

employing institution/organisation (in urban and rural areas) at a nominal

cost to the tenant. (Initially rents were set at 6-10% of household income;

this percentage has dropped further as labour participation rates increased

and some municipal authorities implemented rent reductions.)

Housing output, and attitudes by the government towards housing pro-

vision, can be seen to have gone through a number of stages. During the 1st

Five-Year Plan (FYP) China pursued extensive industrialisation of the

economy paying particular attention to housing for key workers. The level of

output was relatively high, with housing investment running at about 10% of

state construction investments in the period up to 1957. From 1958-1962 (the

2nd FYP period) this went down to 4%, rising slightly in the inter phase

adjustment period, to stabilise again at 4% over the 3rd FYP period (1966-

1970). From the early 1970s housing investment began to rise (as a propor-

tion of overall state construction investment) reaching 20% in 1980 and

representing one-quarter of all state construction spending by 1982 (Kirkby,

1985: 171). After the 3rd FYP period (when state construction investment

was at a low point) absolute resources put into construction have risen

steadily to the highest recorded level (since 19^9) in 1982. The target set for

urban housing construction at a government conference in 1978 was 500

million m2 of housing floor-space completed in the period 1979-1985. This

represented more housing floor-space than was actually constructed over the

previous 20 years. Against expectations this target was achieved. To reach

this level of output new forms of construction and building technology were

employed. The common form of k or 5 storey walk-up apartment blocks was

abandoned, to be replaced by high rise housing blocks using mechanised

building methods.

Behind these figures lie dramatic ideological shifts as the principles

established by Mao for dealing with the economy as a first priority (with

concern for the social well-being of the population deferred into the future)

have recently been questioned and overturned. Housing has come to be seen

as an integral sector in national development.

In an associated shift in principles there has been an attack on low rent

levels for housing. Within the ideological embrace of market guidance and

market regulation inside the planned economy (which has been a hallmark of

changes in China over the past few years) experiments with the use of

private capital investment in housing have been developed. State housing can

now be bought by tenants (outright or on a mortgage).

In rural areas the state has built housing (often in small townships) but

the tradition of private ownership and house-building has never been fully

lost. 'Liberalisation1 of the economy and the possibility of sade of produce in

a more 'open' market system has increased the potential for savings and their

investment through self-help in private house-building.

Land. A mix of land ownership still applies. Expropriation of the land and

property of the larger owners brought most holdings into state ownership. In

urban areas the state is still the largest land owner (either directly or

59

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

through state enterprises). Yet in 1980, 25% of the urban housing stock re-

mained in private hands (including owner occupation and privately rented

property). A relationship has been shown indicating that the larger the city

the smaller the proportion of private property holding. Private ownership is

greatest in the countryside.

Yet rural land reform in China has been described as the most 'sweep-

ing rural transformation in history1 (Blecher, 1986: 43). Land was expro-

priated and redistributed more equitably. Collectivisation was the main

plank of agrarian reform. Full nationalisation of land and equalisation of

holdings was not pursued (principally in the interests of maintaining political

unity and maintaining production levels in agriculture by minimising disrup-

tion).

Settlement Policy. The view that China has pursued policies specifically

intended to minimise regional disparities and inequalities and to control

urbanisation is, in general, correct. However, a number of recent writers

have questioned how strongly these principles and policies have been carried

through or how deeply held they are in present day China. An anti-urban ele-

ment in Chinese spatial policy is predictable to the extent that Mao built the

revolution in the countryside and the corruption and vice of the cities was

associated with the Kuomintang.

Self-reliance in agriculture was accompanied by efforts to promote a

dispersed pattern of development and settlement. Yet the pursuit of econo-

mic development, which requires the maintenance of production in the

coastal industrial cities, has not markedly changed the balance of spatial and

regional inequalities (Chung-Tong, 1987). The dispersal of industry, by

strengthening manufacturing in the interior and the decentralisation of

enterprises from larger to smaller cities, was the centrepiece of past

regional policy. A core city policy has been adopted since 1978 indicating

continued efforts to secure less uneven spatial development in the future.

Africa

Mozambique

Housing Policy. The nationalisation of land and urban rented property soon

after liberation included not only the large flat-blocks (the colonial 'cement

city') in Maputo, Beira, and Nampula but also the timber and reed shacks

(canico) in the shanty towns, the latter representing about 2/3 of urban hous-

ing in 1975.

The 3rd congress of FRELIMO (1977) decided that housing was princi-

pally an individual concern. State priorities were to enhance manufacturing

and production. Within social services, education and health were tackled

along with provision for basic needs such as clean water. Nationalisation of

land and property offered the prospect of overcoming obstacles to housing

improvements due to private ownership and exploitation.

Given these national priorities and the lack of resources (further ex-

acerbated by the counter revolution led by RENAMO) there are two main

elements to state support for housing in Mozambique. Firstly, reliance on

popular mobilisation for housing provision and improvement, with the State

taking on a guiding and developmental role. Popular initiatives in housing are

channelled by the planned use of land, infrastructural improvements (parti-

cularly to improve hygiene through latrine slab programmes, etc.), and tech-

nical support to develope and improve traditional building material pro-

duction and construction methods. Housing production in the communal vil-

lages has been supported mainly by the transport of building materials and of

60

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

household effects for relocated families.

Secondly, the government has undertaken to adapt the construction in-

dustry (previously oriented to modern methods of building production in the

urban centres) to the broader needs of the country by the use of less m

chanised methods. Provincial state building companies have been set up an

appropriate housing forms developed for regional needs and settings. Thes

state construction companies have shown increasing productivity. Shortag

of materials have led to simple housing units being favoured with basic

facilities and finishes. Between 1977-83 4,300 units were built by the state

for key projects and for housing priority- workers. Recently the need for co-

ordination of resources and state efforts has integrated the National Housing

Directorate within the State physical planning system.

The 4th FRELIMO Congress in 1983 took account of the deepening ex-

ternal pressure on the country and the lack of resources by reaffirming in-

dividual, family and small co-operative effort. Local organisation and man-

agement of housing production was further encouraged by support for key

production sectors and enterprises. FRELIMO Neighbourhood Committees

play a key role in leading popular mobilisation by organising collective

programmes of self-help and by support with technical aid and building

materials.

In the urban shantytowns a programme of resettlement has developed

offering secure land-tenure on planned subdivisions, but aid for self-help

housing has been hampered by shortages of building materials.

Land. Nationalisation of land was carried through in 1975. All rented housing

was taken into state ownership in 1976. A considerable housing gain in the

urban centres followed from the take-over of the 'cement cities1.

Collectivisation of agriculture in rural areas has followed the pattern

of organisation in the former liberated zones before the Portuguese with-

drawal.

Settlement Policy. State support for further collectivisation was seen to be a

major means of providing basic needs in health and education as well as

aiding agricultural productivity. The policy of communal villages, ("aldeias

communais") which brought together the rural population into clusters of (a

minimum of) 200 families with collectivisation of work, has been set back by

lack of resources. The communal villages have been evaluated as a social

success but they still face economic difficulties. Among the problems have

been poor location, bad technical advice which has failed to take account of

local traditions in agriculture, and over-rapid implementation. The pro-

gramme has also been relatively limited in relation to need. By the early

1980s 1,300 settlements had received state support but even so the pro-

gramme had only reached 14% of the peasants living at marginal subsistence

levels at the time of liberation.

Urban resettlement policy consists of a programme of communal

neighbourhoods ("bairros communais") with the intention of improving the

overcrowding and congestion of the shantytown.

Tanzania

Housing Policy (3). A number of institutions were set up after liberation

the task of securing home-building and improvements in housing conditio

The National Housing Corporation was given the task of providing ho

for low-income households and carrying out urban-renewal projects. Early

emphasis was given to work in Dar es Salaam with 4,700 units being built

61

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

with NHC help between 1964 and 1969. An associated programme of slum

clearance meant little net gain in housing units. The aim of 25,000 homes

(mainly in the cities) included in the targets of the 1st FYP (1964-1969) was

badly undershot, with only 6,000 units being built. The gap between intention

and output was equally severe in the 2nd FYP period (1969-1974). Twenty-

five thousand homes and 2,100 serviced plots were the target but the com-

bined output of state supported units was only 2,000 p.a. over the period. Use

of imported building materials also pushed up costs so that rent levels were

beyond the pockets of the poorest households.

For these reasons emphasis shifted in the early 1970s to squatter up-

grading schemes and serviced site projects. In the latter, security of tenure

was assured for participants, and basic provision included water supply, elec-

tricity, and drainage. Where possible schools, communal buildings, and health

centres were also provided. In the first serviced-sites projects in the prin-

cipal cities 9,000 plots were included, bringing benefit to an estimated

160,000 people. A second scheme begun in 1978 supported improvements in

living conditions for over 300,000. However, in the second phase only lots

were provided with no other basic provision.

The Tanzania Housing Bank (THB), set up in 1972 provides housing

loans to individuals, housing co-operative and institutions for urban and rural

projects. Loans help pay for materials, labour and other inputs. The pro-

motion of locally produced materials (e.g. burnt bricks) has saved on import

costs. By 1970 the THB was supporting the production of approximately

2,000 units p.a. A special housing fund, with levies on small enterprises and

organisations, also channels loans to rural areas, with priority to ujamaa

villages and housing co-operatives. By 1981 this fund had supported 32,000

village homes with a rising trend of annual loans.

Other institutions which provide help with housing output include state

owned and state-controlled enterprises which (with NHC and THB support)

were providing 3,000 units p.a. by the late 1970s.

The informal, or self -build sector remains the principal means of hous-

ing provision with up to 90% of urban shelter needs being met through un-

aided individual household efforts.

Improvements to infrastructure and basic services in rural settlements

have been dramatic. The 3rd FYP (1976-81) stressed improvements to living

conditions in the countryside and mobile state construction teams were

founded to give technical assistance, training and to organise self help for

village communities.

Land. Land is in public ownership in Tanzania. In 1963 freeholds were con-

verted into state leasehold and in 1968 land was fully nationalised. Rights to

occupation are granted for long terms with associated conditions of use. Re-

vocation of these rights can be decreed if in the public interest (with com-

pensation if necessary) or if tenure conditions are breached. Customary land

tenure can still apply in the rural areas if traditional land holders so wish but

over time this form of tenure is reducing. Subtenancies on land are allow-

able.

An official planning-system controls urban development but urban

squatting makes enforcement difficult and sustains heavy demands for ser-

vices and improved infrastructure. Levies on urban land-holdings capture

some of the enhancement of land values due to urban development.

Settlement Policy. An explicit rural development policy has been followed

since the late 1960s. The 'vUlagisation1 scheme aimed to bring a scattered

62

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

population into key settlements where basic services can be provided more

efficiently and small scale industrial activity promoted. Initially, the ujamaa

principle of collective work and social provision dominated the policy aims

but lack of success in collective farming has led to the promotion of a

broader, more inclusive development for the rural economy.

The pattern of urban development has been set out in the various na-

tional plans. A primary goal has been to slow down the growth of Dar es

Salaam. The creation of a new capital at Dodoma is part of that aim and

development of smaller centres has been promoted by fiscal incentives to

industry as well as infrastructural improvements. Industrial estates have

been built. Advice and training programmes have been offered to businesses.

National long-term economic strategy aims at the development of a heavy

industrial sector and greater production of necessities and consumer goods

(import substitution).

Evaluations of settlement policy have produced mixed conclusions but

almost all studies indicate potential for consolidation and success. Urban

development policy seems to be showing some effect with growth in the

regional centres, although Dar es Salaam also continues to grow. In the rural

areas, although the villagisation policy has not shown any improvements in

agricultural productivity, the programme of meeting basic needs for all

people (such as piped water within a reasonable distance) is well advanced.

General issues

A number of common trends emerge from this preliminary survey. All the

countries discussed here have nationalised land, or have radically reformed

the pre-existing system of land and property holdings in order to give stron-

ger state control over the use of land, the amount of property held by indiv-

iduals, the form of exchange and the costs of property. The rationale for this

common measure has been the desire to limit speculation and individual

profit and to seek greater equality with respect to land and housing con-

ditions.

Most of the six nations have pursued an explicit rural settlement pol-

icy^). This is usually followed in the belief that such action will help to

redress regional inequalities and to loosen the grip that large urban-centres

can exert over resources, which is seen to heighten regional imbalances in

the economy and in living conditions.

Housing is frequently given a lower priority in national plans and ob-

jectives than olther social-services, particularly health and education. Many

of these nations have followed strategies of popular mobilisation and decen-

tralisation of decision-making within a framework of national planning. It is

noticeable that this movement towards decentralisation and popular control

comes about as the revolutionary leaderships learn from experience and the

economies develop. In some cases, self-build as an element of housing pro-

duction has become more significant than direct provision of housing by the

state.

A noticeable difference between self-help housing in the capi

Third-World and in socialist developing-countries is that in the lat

build is frequently organised on a collective basis.

The debate about whether housing is productive or unproductive i

ment continues. Clearly the demand for a healthy, locally concentrate

relatively contented workforce was an element in the development of

involvement in housing during the industrialisation of the capitalist W

the 18th and 19th centuries. However, shortage of labour power i

crucial a factor for the developing world, so the imperative of housing

63

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

provision by the state is less essential for economic development. On the

other hand, housing is considered a social service by socialist countries and

recognition is given to the right to a decent home and a collective respons-

ibility is accepted to work to that end. Difficulties arise where housing

provision is seen to compete with other elements of development, particu-

larly where finance, materials, tools, and specialised labour are in short

supply.

What appears to occur (on the basis of this brief study) is that re-

cognition of housing need and the lack of investment (for maintenance and

repair) becomes a more pressing demand as revolutions develop. The ex-

amples of the longer established revolutions in China and Cuba show that the

resources put into housing programmes begin to be increased some decades

after the overthrow of previous political regimes.

One solution to the productive/ un productive debate and the lack of

national resources is to promote self-help in housing. Costs of housing can be

reduced by popular initiatives(5). However, there are a number of theoretical

issues which need to be considered. We have found no extended discussion of

self-help housing in the context of socialist development. Western Marxist

discussions of self-help in the capitalist developing world are unhelpful

(Burgess, 1978) by pursuing issues of 'double exploitation' and 'commodifi-

cation of housing'.

Double exploitation refers to the process by which workers in capitalist

economies are subject to exploitation in the workplace (where the owner

takes a surplus from their labour) and then may have to labour out of work-

time to provide shelter for self and dependents. The argument fails to re-

cognise that housing is more than a utilitarian artifact and that self-builders

may gain considerable psychic satisfaction from their building work and from

the end product.

The issue of com modification is not absent in a socialist context.

Strictly, where elements of housing (materials, land, houses) can be

exchanged then housing itself can be considered a commodity. That

values can be supplemented by exchange values, so commodity relations are

established. However, we should recognise that there is a difference between

the law of value and the role of commodities in a planned economy and a

market economy. In the former, legal exchange is not based on the principle

of extracting maximum profits or an exploitation of recipients of the com-

modities. 'Liberalisation' within socialist revolutions (such as the estab-

lishment of farmers' markets, which allow an element of market pricing and

can create savings for individuals and the possible injection of private

capital into housing, e.g. China) makes the distinction between socialist and

capitalist economies more indistinct over the issue of com modification.

However, as Castro has said 'a socialist state can, if it so desires, build

homes, rent them, receive income and even profits, since these profits can

be destined for other things which benefit the people and would be in keeping

with the ethic or principles of socialism' (Jenness, 1985: 297).

A further issue which differentiates self-help housing in the socialist

Third-World from elsewhere is the organisation of building on a collective

basis. Co-operative house building is often one aspect of popular mobilisation

in socialist contexts (which includes local involvement in health care,

education, food distribution etc.). In reviewing the factors which make for

success in self-help housing projects in the capitalist Third-World, Skinner

identifies collective effort and state support as necessary conditions for

viable self -building (Skinner, 1982). It is characteristic of the socialist Third-

World that these elements are present in self-build efforts.

64

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

With respect to settlement policy and regional inequalities the policies of

development, which are becoming more insistent in the face of massive ur-

ban growth in the capitalist Third-World are, increasingly focused on limita-

tion of urban size or securing more attractive intermediate urban centres for

potential migrants to primate cities. Growth poles, integrated rural devel-

opment and the promotion of small and mid-sized cities have been suggested

as possible models for dealing with the primate city problem (Mohit, 1988).

However, policies which follow these models have had limited success in the

capitalist context and although the de-urbanisation policies adopted by some

socialist Third-World countries (e.g. Vietnam) have been criticised for their

taint of coercion, the promotion of greater equality and balanced develop-

ment may offset this criticism.

References

Appleton, 3. (1983)

'Socialist Vietnam: continuity and change', in Lea, D. and Chaudri, D.P.

(eds.) Rural Development and the State, London: Methuen, 273-300.

Blecher, M. (1986)

China: Politicsy Economics and Society, London: Pinter.

Burgess, R. (1978)

'Petty commodity housing or dweller control?', World Development, 6,

1 105-34.

Chung-Tong, W. (1987)

'Chinese Socialism and Uneven Development' in Forbes, D. and N.

Thrift, N. (eds.), The Socialist Third World, Oxford: Blackwell, 53-97.

Darke, R.A. (1987)

'Housing in Nicaragua', International Journal of Urban and Regional

Research, 11, 100-114.

Deacon, B. (1983)

Social Policy and Socialism. London: Pluto.

Forbes, D. and N. Thrift, (1987)

'Introduction' in Forbes, D. and N. Thrift, (eds.), The Socialist Third

World. Oxford: Blackwell, 1-26.

Hamberg, 3. (1986)

'The Dynamics of Cuban Housing Policy' in Bratt, R.G., C. Hartmann,

and A. Meyerson, (eds.), Critical Perspectives in Housing, Philadelphia:

Temple University Press.

Hardoy, J. and D. Sat ter thw aite, (1981)

Shelter, Need and Response, New York: Wiley.

Jenness, D. (1985)

'New housing law to go into effect', International Press, 23, 203-237.

Kirkby, R.J.R. (1985)

Urbanisation in China: Town and Country in a Developing Economy,

1949-2000 AD. London: Croom Helm.

Mohit, M. (1988)

Development of Small and Medium Sized Towns in Bangladesh: A Re-

gional Planning Approach, Unpublished PhD, University of Shef field.

Murray, M. and P. Picha, (1982)

'Why Make a Socialist Revolution?' The Case of Vietnam, in Chase-

Dunn, C.K. (ed.), Socialist States in the World System Beverley Hills:

Sage, 253-267.

65

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Nguyan duc Nhuan (1984)

'Do the urban and regional policies of socialist Vietnam reflect the

patterns of the ancient Mandarin bureaucracy?, International Journal of

Urban and Regional Research, 8, 78-139.

Skinner, R.J. (1983)

•Community Participation: Its scope and organisation1 in Rodell, M.J.

and R.J. Skinner, (eds.), People, Poverty and Shelter: Problems of Self

Help Housing in lhe Third World, London: Methuen.

Slater, D. (1986)

•Socialism, democracy and the territorial imperative1, Antipode, 18, 155-

185.

Turok, B. (1987)

'Marxist States in Africa1 (review), Third World Quarterly, 9, 744-750.

Wiles, P. and A. Smith, (1982)

'The General View, especially from Moscow', in Wiles, P. (ed.), The New

Communist Third World, London: Croom Helm, 13-49.

Footnotes

(1) The useful series of 36 volumes (already published or planned) on 'M

ist Regimes') under the general editorship of Bogdan Szajkowski (pu

lisher F. Pinter, London) contains some definitional anomalies. In p

ticular, Ghana under Rawlings is not an obvious candidate for inclusion.

Whilst Rawlings associated with Marxists during the seizure of pow

and Marxist influences continue within the government, socialism w

openly rejected as a potential goal by the leader (Turok, 1987: 74 9).

(2) By 1975, 335 new settlements had been created in the Cuban countr

side since 1959, with housing for 140,000 persons (Angotti, 1983: 14).

(3) The section on Tanzania rests heavily on the work of Hardoy and

ter thwaite to whom full recognition must be given (Hardoy and S

ter thwaite, 1981).

(4) Hardoy and Satter thwaite note that (with the exception of Tanzania

none of the seventeen nations in their study had an explicit rural housi

policy.

(5) There are other pressires, such as the external aggression facing coun-

tries such as Nicaragua and Mozambique, which force economies in so-

cial programmes. In Nicaragua, government officials are not unanimous

in support of self-help, believing it to lead to poor work and loss of

materials. Cuban officials have also acted to adapt the microbrigade

programme for similar reasons. Whether this implies that direct state-

housing provision by construction teams will be reintroduced as these

economies strengthen is an open question.

66

This content downloaded from

87.222.72.175 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 08:58:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Sklair, Leslie (2012) - Transnational Capitalist Class (En The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization)Document2 pagesSklair, Leslie (2012) - Transnational Capitalist Class (En The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization)joaquín arrosamenaNo ratings yet

- Globalization and The State (Is 261)Document12 pagesGlobalization and The State (Is 261)Gerald MagnoNo ratings yet

- Ahmad, Eqbal, Post-Colonial Systems of PowerDocument15 pagesAhmad, Eqbal, Post-Colonial Systems of PowerbaaalNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 13.234.156.0 On Thu, 18 Mar 2021 15:07:06 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 13.234.156.0 On Thu, 18 Mar 2021 15:07:06 UTCakira menonNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 207.62.77.131 On Wed, 24 Jun 2020 06:07:51 UTCDocument15 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 207.62.77.131 On Wed, 24 Jun 2020 06:07:51 UTCcrobelo7No ratings yet

- 7 Knight Democracia y Revolucion ALDocument41 pages7 Knight Democracia y Revolucion ALPEDRO MARTIN HERNANDEZ MADRIDNo ratings yet

- Neocolonialism, Neoliberalismand PostdemocracyDocument9 pagesNeocolonialism, Neoliberalismand Postdemocracykiranbarki63No ratings yet

- Wiley, Society For Latin American Studies (SLAS) Bulletin of Latin American ResearchDocument41 pagesWiley, Society For Latin American Studies (SLAS) Bulletin of Latin American ResearchTatNo ratings yet

- Contemporary World ReviewerDocument5 pagesContemporary World ReviewerAshiro Dump100% (1)

- Social Justice/Global Options Social Justice: This Content Downloaded From 132.248.9.8 On Thu, 11 Oct 2018 22:11:35 UTCDocument15 pagesSocial Justice/Global Options Social Justice: This Content Downloaded From 132.248.9.8 On Thu, 11 Oct 2018 22:11:35 UTCHilary GoodfriendNo ratings yet

- Democratic and Revolutionary Traditions in Latin AmericaDocument41 pagesDemocratic and Revolutionary Traditions in Latin AmericaNina ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Unit 4Document12 pagesUnit 4Cezanne Pi-ay EckmanNo ratings yet

- Week 2 China's Development Path by Michael DunfordDocument31 pagesWeek 2 China's Development Path by Michael DunfordCain BureNo ratings yet

- Sen (1990) Socialism, Markets and DemocracyDocument7 pagesSen (1990) Socialism, Markets and DemocracyjrodascNo ratings yet

- Pluto JournalsDocument15 pagesPluto JournalsNEVER SETTLENo ratings yet

- Transnational Democracy: Theories and Prospects: January 2002Document51 pagesTransnational Democracy: Theories and Prospects: January 2002Franco van WykNo ratings yet

- Wallerstein-Dependence in An Interdependent World - The Limited Possibilities of Transformation Within TheDocument27 pagesWallerstein-Dependence in An Interdependent World - The Limited Possibilities of Transformation Within TheMariana Zuluaga SalazarNo ratings yet

- Cynthia H. Enloe - Beyond Modernization - 1969Document7 pagesCynthia H. Enloe - Beyond Modernization - 1969EliKrasniqiNo ratings yet

- Connell Worldneoliberalismcome 2014Document23 pagesConnell Worldneoliberalismcome 2014jdpisoNo ratings yet

- 2005 Della Porta Tarrow Transantional MovementsDocument18 pages2005 Della Porta Tarrow Transantional MovementsYato SakataNo ratings yet

- Globlization and Literature PDFDocument96 pagesGloblization and Literature PDFjesusdavid100% (4)

- Impact of Socialism On Different CountriesDocument20 pagesImpact of Socialism On Different CountriesAnkitNo ratings yet

- Cox - 'Multilateralism and World Order'Document21 pagesCox - 'Multilateralism and World Order'Kam Ho M. Wong100% (1)

- Shumpei Kumon Yasuhide YamanouchiDocument23 pagesShumpei Kumon Yasuhide YamanouchiymnchyNo ratings yet

- John Urry: Globalization and CitizenshipDocument8 pagesJohn Urry: Globalization and CitizenshipMahi Sanjay PanchalNo ratings yet

- 30jan2021 Civil Society Media Approaches PART 1 CDocument27 pages30jan2021 Civil Society Media Approaches PART 1 CChino Estoque FragataNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3Document6 pagesLecture 3Hekuran H. BudaniNo ratings yet

- Robinson 2000Document45 pagesRobinson 2000José Manuel MejíaNo ratings yet

- AraghiDocument33 pagesAraghiAby GuagchingaNo ratings yet

- Gurr MinoritiesRebelGlobal 1993Document42 pagesGurr MinoritiesRebelGlobal 1993ananokirvaNo ratings yet

- Module 6Document15 pagesModule 6Anand Wealth JavierNo ratings yet

- Toulouse 1991 Thatcherism Class Politics and Urban Development in LondonDocument22 pagesToulouse 1991 Thatcherism Class Politics and Urban Development in LondonafswyshnmqowgykmqoNo ratings yet

- The State Empire and ImperialismDocument28 pagesThe State Empire and ImperialismOmer TezerNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4. Global Interstate SystemDocument8 pagesLesson 4. Global Interstate SystemAntenorio Nestlyn MaeNo ratings yet

- Communism and TerrorDocument12 pagesCommunism and TerrorDarkwispNo ratings yet

- Weak Civil Society in CEECDocument8 pagesWeak Civil Society in CEECKristin KretzschmarovaNo ratings yet

- 2013 DavyDocument20 pages2013 DavyAndres GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Dependency Theory 1 PDFDocument19 pagesDependency Theory 1 PDFTawny ClaireNo ratings yet

- Globalization Topic I .PPTX DalidaDocument26 pagesGlobalization Topic I .PPTX Dalidadominia.salvidar1No ratings yet

- Nacionalismo-Banal MexicoDocument22 pagesNacionalismo-Banal MexicoMario RuferNo ratings yet

- Michigan State University Press Northeast African StudiesDocument45 pagesMichigan State University Press Northeast African StudiesJust BelieveNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document22 pagesChapter 2Aprisal MalaleNo ratings yet

- Global Civil SocietyDocument12 pagesGlobal Civil SocietyHawaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Wallerstein 1968Document20 pagesWallerstein 1968Preda GabrielaNo ratings yet

- Resurrecting Media Imperialism - SparksDocument18 pagesResurrecting Media Imperialism - SparksVanessa PortillaNo ratings yet

- WSFocus DeviDocument20 pagesWSFocus DeviAdarsh KhandateNo ratings yet

- Globalization and CommunismDocument21 pagesGlobalization and CommunismBursebladesNo ratings yet

- Anthropology StateDocument6 pagesAnthropology Statejcarlosssierra-1No ratings yet

- Oommen - 2014 - Some Prerequisites For Internationalisation of SociologyDocument7 pagesOommen - 2014 - Some Prerequisites For Internationalisation of SociologyJuani TroveroNo ratings yet

- Metacognitive Reading Report:: Global Divides: The North and The SouthDocument34 pagesMetacognitive Reading Report:: Global Divides: The North and The SouthJohn Rey LayderosNo ratings yet

- International Critical ThoughtDocument18 pagesInternational Critical ThoughtLizette MourNo ratings yet

- Alan Knight - Democratic and Revolutionary Traditions in Latin AmericaDocument41 pagesAlan Knight - Democratic and Revolutionary Traditions in Latin AmericaalienpenguinNo ratings yet

- Cox-Multilateralism and World Order - 1992Document20 pagesCox-Multilateralism and World Order - 1992lucilalestrangewNo ratings yet

- Taitu Heron - Globalization, NeoliberalismDocument18 pagesTaitu Heron - Globalization, NeoliberalismTia RamNo ratings yet

- Emergi.g: Transnational Civil Society: How A Cosmopolitan Vision IsDocument12 pagesEmergi.g: Transnational Civil Society: How A Cosmopolitan Vision IsLuiz Carlos PereiraNo ratings yet

- Introduction To International Development CH4Document13 pagesIntroduction To International Development CH4snowdave1997No ratings yet

- Global Global MediaDocument3 pagesGlobal Global MediamichaelNo ratings yet

- Tomlinson - What Was The Third WorldDocument16 pagesTomlinson - What Was The Third WorldMaría Camila Valbuena LondoñoNo ratings yet

- Democracy and Prosperity: Reinventing Capitalism through a Turbulent CenturyFrom EverandDemocracy and Prosperity: Reinventing Capitalism through a Turbulent CenturyNo ratings yet

- Architecture Competitions - A Space For Political Contention. Socialist Romania, 1950-1956Document15 pagesArchitecture Competitions - A Space For Political Contention. Socialist Romania, 1950-1956Renato PaladeNo ratings yet

- Arhne: The New, The Old, The Modern. Architecture and Its Representation in Socialist Romania, 1955-1965Document245 pagesArhne: The New, The Old, The Modern. Architecture and Its Representation in Socialist Romania, 1955-1965Renato PaladeNo ratings yet

- SEEU 041 02 StanoevaPRINTDocument29 pagesSEEU 041 02 StanoevaPRINTRenato PaladeNo ratings yet

- Ugly or Beautiful The Housing Blocks Communism Left BehindDocument1 pageUgly or Beautiful The Housing Blocks Communism Left BehindRenato PaladeNo ratings yet

- Accounting Principles: The Recording ProcessDocument52 pagesAccounting Principles: The Recording ProcessPseu DoNo ratings yet

- Basel Ii at A GlanceDocument13 pagesBasel Ii at A GlanceNaushad AnsariNo ratings yet

- Housing: Module 1Document28 pagesHousing: Module 1Swaradipa RoyNo ratings yet

- Banking Financial Institutions.Document18 pagesBanking Financial Institutions.Jhonrey BragaisNo ratings yet

- 8 Months Study PlanDocument24 pages8 Months Study PlanAravind k sNo ratings yet

- Balance Sheet AccountancyDocument18 pagesBalance Sheet AccountancyMeenuNo ratings yet

- Adidas Group Equity ValueDocument4 pagesAdidas Group Equity ValueDiaa eddin saeedNo ratings yet

- XBA-SAR4 (Pulse+MDB+ICT+Parallel A3) PDFDocument1 pageXBA-SAR4 (Pulse+MDB+ICT+Parallel A3) PDFVasil StoyanovNo ratings yet

- Project Journal 2Document4 pagesProject Journal 2Victor SalamiNo ratings yet

- Glossary of Banking, Economic and Financial TermsDocument22 pagesGlossary of Banking, Economic and Financial Termssourav_cybermusicNo ratings yet

- The AI Economy Free Summary by Roger BootleDocument14 pagesThe AI Economy Free Summary by Roger BootleRakesh SharmaGLNo ratings yet

- Tax Information Authorization: Form (Rev. January 2021) Department of The Treasury Internal Revenue ServiceDocument1 pageTax Information Authorization: Form (Rev. January 2021) Department of The Treasury Internal Revenue ServiceMatthew PickettNo ratings yet

- 45 Profit and Loss Questions With SolutionsDocument46 pages45 Profit and Loss Questions With SolutionsGHAPRC RUDRAPURNo ratings yet

- Haircut SecuritiesDocument15 pagesHaircut Securitiesamiit.agarwalNo ratings yet

- Antoine Augustin CournotDocument3 pagesAntoine Augustin Cournotthomas555No ratings yet

- Marathon 1 - Time Value of MoneyDocument96 pagesMarathon 1 - Time Value of MoneyMirdula SharmaNo ratings yet

- No Questions Answers: Faqs Financial Management and Resilience Programme (Urus)Document12 pagesNo Questions Answers: Faqs Financial Management and Resilience Programme (Urus)Khalis Munzir KhazinNo ratings yet

- Midterm ExamDocument5 pagesMidterm ExamKimNo ratings yet

- Analysis: Actual Time Approximate Time May June JulyDocument4 pagesAnalysis: Actual Time Approximate Time May June JulySharmin ReulaNo ratings yet

- MCQ - International Marketing - With Answer Keys PDFDocument8 pagesMCQ - International Marketing - With Answer Keys PDFVijyata Singh100% (2)

- EmiratesTicket Japan MancDocument3 pagesEmiratesTicket Japan MancTheodore69No ratings yet

- Financial Accounting by PC TulsianDocument16 pagesFinancial Accounting by PC TulsianGeeta Univ0% (1)

- Ida CalculationDocument1 pageIda CalculationRambabu DanduriNo ratings yet

- Elasticity of SupplyDocument10 pagesElasticity of SupplyAyas JenaNo ratings yet

- Invoice-Yogesh PatilDocument2 pagesInvoice-Yogesh PatilabcNo ratings yet

- Global BibliometricDocument8 pagesGlobal BibliometricRajendra LamsalNo ratings yet

- Airport Codes in The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesAirport Codes in The PhilippinesLAWRENCE DICDICANNo ratings yet

- The Brics Order Assertive or Complementing The West 1St Edition Edition David Monyae Full ChapterDocument67 pagesThe Brics Order Assertive or Complementing The West 1St Edition Edition David Monyae Full Chapterclaretta.vanhamlin374100% (4)

- University of Mumbai Project On Money Market Instrument Bachelor of CommerceDocument6 pagesUniversity of Mumbai Project On Money Market Instrument Bachelor of CommerceTusharJoshiNo ratings yet

- 6 The Academy of Forex Table For Could Be Good Good Better and Best INDICATORSDocument56 pages6 The Academy of Forex Table For Could Be Good Good Better and Best INDICATORSPaulinus OnyejeluNo ratings yet