Professional Documents

Culture Documents

(Expedition To Trengganu and Kelantan) (JMBRASS)

(Expedition To Trengganu and Kelantan) (JMBRASS)

Uploaded by

MUAZ BIN MUZAFFAOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

(Expedition To Trengganu and Kelantan) (JMBRASS)

(Expedition To Trengganu and Kelantan) (JMBRASS)

Uploaded by

MUAZ BIN MUZAFFACopyright:

Available Formats

[Expedition to Trengganu and Kelantan]

Author(s): Khoo Kay Kim and Hugh Clifford

Source: Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society , May, 1961, Vol.

34, No. 1 (193), Expedition to Trengganu and Kelantan (May, 1961), pp. xi-xviii, 1-162

Published by: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41505504

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Introduction

One can hardly over-emphasise the importance of any

historical data which have bearing on the eastern Malay states

for the simple reason that these states have been unfairly

neglected in the standard history works on Malaysia. Of the

writings which have, from time to time, appeared on these

states,1 few are now easily accessible to the average student of

Malaysian history. Moreover, the majority of the existing

works tend to concentrate on general history or administra-

tive and constitutional developments beginning from about

1900. In so far as the indigenous society itself is concerned,

no careful study has been undertaken.2 This is no doubt due

partly to the scarcity of source material. Bearing this in

mind, it will be possible to realise how extremely useful is

Clifford's report on his expedition to Trengganu and

lw Various types of writings have appeared on the more modern period

of Trengganu and Kelantan history,. Some of these have been by

contemporary visitors and therefore contain valuable information on

the conditions oř the time. The best known of these are Abdullah bin

Abdul Kadir, Kisah Pelayaran Abdallah (ed. by Kassim Ahmad, Kuala

Lumpur, 1960) and Gu W. Earl, The Eastern Seas , or Voyages

and Adventures in the Indian Archipelago, London, 1837,. The general

history of the two states has also been written by various people - see,

in particular, Haji Abdullah, "A Fragment of the History of Trengganu

and Kelantan" JSBRAS, no. 72, May 1916 (ed. by Sir H. Marriott);

A. Rent.se, "History of Kelantan" JMBRAS, vol. 12, pt,. 1, 1934; and

M. C. if. Sheppard, "A Short History of Trengganu" JMBRAS , vpl.

22, pi 3, 1949. Also an invaluable historical source is the work of

the Bugis historian, Raja Ali Haji, Tuhfat al-Nafis, Singapore, 1963.

Kelantan, in addition, has received some extra publicity through the

writings of A. Wright and T. H. Reid ( The Malay Peninsula , London,

1912) and its first Resident Commissioner and Adviser, W: A. Graham

- Kelantan: A Handbook of Information, Glasgow, 1909, "Kelantan"

The Encyčbpaedia Britanîca, 11th ed;, 1909-11, and "Report of W: A.

Graham, Siamese Resident Commissioner, 1903-4" Malay Mail , 4 March

1905: Through Graham, Trengganu has also appeared in the

Encylopaedia Británico (13th ed,.)) and both the states have been use-

fully treated by R. Emerson in Malaysia : A Study in Direct and

Indirect Rule, New York, 1937,. More recently, scholarly studies oř the

two states have also been published - Chan Su-ming, "Kelantan and

Trengganu, 1909-1939" JMBRAS , vol. 38, pt. 1, 1965; C. Skinner,

"The Civil War in Kelantan in 1839" Monograph II of MBRAS, 1965;

and J. de V. Allen, "The Ancien Regime in Trengganu, 1909-1919"

JMBRAS, vol. 41, pt. 1, 1968.

2. That is, in the same manner as J. Mu Gullick's Indigenous Political

Systems of Western Malaya, London, 1958.

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

xii Khoo Kay Kim

Kelantan in 1895 for it is by far one of

and comprehensive documents availab

After submission in 1895 it was first re

the Federated Malay States Governmen

never been easily available to both stude

Malay society.3

Hugh Charles Clifford, born on 5 Mar

cated at Woburn Park, spent half of his

country. He joined the Perak Service o

1885, he was Collector of Land Revenu

It was in Jan. 1887 that he was first sen

special mission, and thereafter, for the

early service in this country, he served i

capacities - Acting Government Agent (1

tendent, Ulu Pahang (1889-90), Acting

Pahang (1890-96). It was as Acting Reside

a leading part in suppressing the anti-Br

by Dato' Bahman. In between he was a

to the Government of Selangor (1894) an

Commissioner to visit Cocos- Keeling Isl

promoted to the rank of British Resident

1896 and in Dec. 1899 held concurrently

Governor of North Borneo and Labuan. Clifford was next

transferred to the West Indies where he held w.e.f. 15 Sept.

1903 the appointment of Acting Colonial Secretary, Trinidad

and Tobago. He was confirmed in the appointment one year

later. Until he left for Ceylon, on two occasions he served

as Officer Administering the Government (1904 and 1906).

Clifford assumed duties as Colonial Secretary, Ceylon, on

3 May 1907 and until he left Ceylon in 1912 was Officer

Administering the Government on four occasions. He

became Governor of the Gold Coast on 11 Dec. 1912. In

Aug. 1914, he concluded with M. Noufflard, the Lieutenant-

3. A summarised version of Clifford's observations of the two states has

appeared in the journal of the Royal Geographical Sbciety, London

(V. "A Journey through the Malay States of Trengganu and Kelantan"

The Geographical Journal, vol. IX, 1897). It may be added that in

later years the journal (vol. 33, 1909) also carried an anonymous article

entitled "The New British- Protected Malay States: Kelantan,

Trengganu, and Keda".

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Introduction xiii

Governor of Dahomey, an agreem

tition between the British and French Governments and for

the provisional administration of Togoland. At the same

time, he administered the British sphere of occupation

(Togoland) concurrently with the Gold Coast. On 23 July

1919, he was made Governor of Nigeria. He returned to

Ceylon on 10 Nov. 1925 as its Governor and on 9 June 1927

he was transferred back to this country as the Governor of

the Straits Settlements and High Commissioner for the Malay

States and British Agent for Sarawak and British North

Borneo. He finally retired from Colonial Service on 21 Oct.

1929.4

Although the value of Clifford's report, as a historical

source, is undeniable, it is nonetheless necessary for readers

to separate the grain from the chaff. The report is primarily

a political document and only secondarily a record of social

and economic conditions in late 19th century Trengganu and

Kelantan. The military nature of Clifford's expedition

unavoidably determined the main substance of his report and

the numerous enclosures. This has to some extent minimis-

ed the importance of the document. Not that the political

data cannot prove of some value to present-day historians for

even interest in the Pahang disturbances of the late 1890s is

very much alive. But history as primarily a story of wars and

political upheavals no longer occupies the pre-eminent posi-

tion it once enjoyed. Even if many historians have continu-

ed to preserve their interests in political history, the approach

to the writing of such history has undergone significant

changes. It is generally agreed that political upheavals can-

not justifiably be seen as merely spectacular events; they can

be understood only if seen against the background of

the society in which they have erupted. And therefore simply

to recount what happened can hardly prove meaningful. As

such, the minute details given of the expedition's attempt to

pursue and apprehend the so-called rebels will probably

prove interesting to only those who have no more than an

esoteric interest in great events of history.

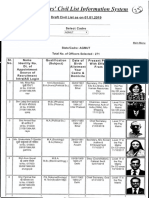

4. The Malayan Cvúl List , 1929 , pp. 70-71.

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

xiv Khoo Kay Kim

On the other hand, within a space of a

Clifford has dealt quite meticulously with a

in the two eastern states. The data on Kelantan are, of

course, regretably brief but that regarding Trengganu could

serve as excellent material for those who are equipped with

the proper analytical tools to make a careful case study of

the indigenous Malay society.

Perhaps the most valuable of Clifford's observations are

those which concern the traditional socio-political system be-

cause so little yet has been written on the subject. The

western Malay states, in particular Negri Sembilan, have been

comparatively fortunate but the east coast states have suffered

serious neglect. Clifford's observations, however, render it

at least possible to make some tentative conclusions about

the traditional polity in 19th century Trengganu and

Kelantan.

Clifford claims that, prior to the mid-nineteenth century,

in Trengganu, the aristocrats, as a class, enjoyed substantial

political power by virtue of the fact that they "held in fief

from the Sultan" a number of districts in the state. This,

to some extent, is borne out by the observation of an earlier

visitor to Trengganu:

The government must be pronounced aristocratical,

for although the Sultan is nominally the chief au-

thority, the whole power is vested in the pangerans,

or lords.®

Clifford, however, refers to them merely as Dato'. These

were, in fact, the highest authority at the district level for

there was a distinct hierarchy of aristocrats though they were

not divided into multiples of four® as in the case of Kedah,

Pahang and Perak. Immediately below the Dato' stood the

Dato' Muda and1 further down the rank, that is, at the village

level, were the various headmen called Ketua-an.

During the reign of Baginda Omar (1839-76), a number

of the offices were allowed to lapse. The political organisa-

tion was gradually re-organised so that a highly centralised

3. Earl, op. cit., p. 184.

6. See J. de V,. Allen, op cit, p. 99 (citing Conlay's report on Trengganu).

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Introduction XV

form of administration was bro

aristocrats was replaced by a sim

which was under the charge of

directly responsible to the sup

mained much the same during t

Baginda Omar's successor. But

III, only 18 years old, succeeded

was made by members of the ro

political power by having the v

to them so that they could ap

these members of the royal fam

administrators who had agent

sibilities.

It is interesting to note that within less than a century,

three variations were found in the Trengganu political

system. However, only the village-commune type can lay

any claim to uniqueness in the Malay Peninsula. The system

of allowing political power to accumulate in the hands of

the aristocrats or the members of the royal family represent

two variant forms of political arrangements which had pre-

cedence in some of the other Malay states, for example,

Perak and Selangor respectively.

Clifford's observations of the Kelantan political system,

if accurate, are extremely interesting if only because the

system presents a distinct contrast to that which obtained in

Trengganu. Here was to be found another example of a

highly centralised Malay political system but unlike the

system which prevailed during Baginda Omar's reign in

Trengganu, in Kelantan, there existed simultaneously a

powerful class of aristocrats "who support him [the Sultan],

and keep him in enjoyment of the position he holds."7 An

equally interesting feature of the political system here was

the concentration of the orang besar in the capital (Kota

7. Chan Su-ming, referring to Graham's report of 1903-4, writes: "The

impotence of the Raja's position was apparent from the privileges

wrested from him by the more powerful of the aristocrats. Together

with financial benefits and arbitrary judicial powers, they were also given

the right to veto orders of the Raja on matters of state. (op. cit.,

p. 160).

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

xvi Khoo Kay Kim

Bahru). It tends rather to remind one of th

which existed at the time of the Malacca Sultanate. Malacca,

then a political state based essentially on the port, had all

the important political paraphernalia located in the capital.

In Kelantan, where the population was also inclined to be

multi-racial because of mining activities, though far less so

than in the case of Malacca, there was at least one Kapitan

China known to have been appointed (in the district of

Galas) who was also directly responsible to the Raja. And

if one is looking for an obvious sign of Siamese influence,

it is to be found in the institution of Kweng (headmen who

ruled over various village communes along Sungai Kelantan,

each directly responsible to the Raja). However, as men-

tioned earlier, Clifford's account of Kelantan is unhappily

brief so that much of the information on its socio-political

system will have to be obtained from elsewhere and fortu-

nately enough for the historian there have been more in-

digenous writings on Kelantan than on Trengganu.8

Clifford's account of the topography and geography of

the two states is no less important to historians. Quite apart

from the fact that his detailed descriptions help to produce

an extremely clear visual picture of the states, it is important

to bear in mind that the structure of the Malay polity was

in large measure influenced by geographical factors. For

example, the wide dispersal of political power was largely

due to the wide geographical dispersal of component parts of

the state. Hence, the further away from the capital, the

greater would be the political power enjoyed by the local

authority. This might be a very broad principle which has

only general application, nevertheless it would have to be

taken into consideration in any specific study of the tradi-

tional Malay polity. Moreover, in view of the fact that it

has never been easy to define the Malay state, any graphic

description of these states would undoubtedly be a welcomed

contribution to the subject. One might venture to add that

from the descriptions provided by Clifford there are now suf-

ficient data to strengthen an observation made as early as the

mid-nineteenth century that the Malay state was basically an

8. See Journal Persatuan Sejarah Kelantan , no. 1, 1964/65.

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Introduction xvii

agglomeration of river settlements

case of Negri Sembilan, there wa

the river served as a boundary b

The very minute description o

tan economy in this document a

Information on the subject for the

tury is easily enough available in

coast states.10 For the 20th centu

on the official reports the major

served in various libraries and ar

covering the last twenty years of

difficult to come by. Even the

lost.11

Clifford's report bears testimo

economy in both the eastern stat

cline during the latter half of t

lation here compared favourably

the western Peninsula although

tion was, on the whole, insign

greater proportion of the people

others were engaged in variou

Trading relations with the ou

Singapore) continued much as it

Indigenous currency had not yet

one and native handicraft and in

fore the major difference betwee

the western Peninsula then was that in the latter case, the

rate of economic growth was much faster, and hence also,

social change.

Lastly, here as elsewhere Clifford has a great deal to say

9. See, J. R. Logan, "Notes on Pinang, Kidah & c." Journal of the Indian

Archipelago and Eastern Asia, vol. 5, 1851, pp. 63-4;.

10. Apart from the writings of contemporary visitors already mentioned,

see also, Wong Lin Ken, "The Trade of Singapore, 1819-69" JMBRAS,

vol, 33>, pt. 4, 1960.

11. I refer to the Colonial Secretariat Records (Singapore). Straits) Settle-

ments Records up to 1867, however, are still available although they

are incomplete.

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

xviii Khoo Kay Kim

about the Malays.12 Most of his remarks are,

jective and reflect the bias of the times. As a

he believed in the superiority of British cult

or at least he purported to believe in it so t

persuade others of the righteousness of British

less to say a great deal of his remarks are un

therefore will prove of little value to more se

of social anthropology. But here and there

and phrases could be stripped of their moral

the reader may yet find descriptive informati

value. For after all, it is as a source of inform

geography, polity and ethnography of Treng

lantan that Clifford's report will be valued f

to come.

Khoo Kay Kim

Dept. of History

University of Malaya

Kuala Lumpur.

12. Some of his better known writings are: Studies in Brown Humanity,

being Scrawls and Smudges in Sepia White, and Yellow, London, 1898;

Malayan Monochromes, London, 191 $; In Court and Kampong, London,

1927; In a Corner of Asia, London, 1928; Bushwhacking and Other Asiatic

Tales and Memories, London, 1929L A collection of some of his stories

has recently been re-published, see, Stories by Sir Hugh Clifford

(selected and introduced by W. R. Roff), Oxford University Press,

Kuala Lumpur, 1966.

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Resident 1023

0 Resident

REPORT OF MR. CLIFFORD, ACTING BRITISH

RESIDENT OF PAHANG, ON THE EXPEDITION

RECENTLY LED INTO TRËNGGANU AND

KËLANTAN ON THE EAST COAST OF THE MALAY

PENINSULA.

British Residency, P'ahang, 7th August , 1895.

To the Hon. the Colonial Secretary, S.S.

Sir, - I have the honour to forward, for the information

of His Excellency the Governor, the following Report on the

Expedition, which I recently led into the Malay States of

Trènggânu and Kělantan, on the East Coast of the Malay

Peninsula. Although, from time to time during my absence

from Pahang, I have forwarded to you short reports dealing

with the purely political portion of my work, I have hither-

to been unable to furnish you with a full and detailed account

of the journey accomplished by the Expeditionary Force

under my command. The press of writing, consequent upon

the arrears which had accumulated during my prolonged

absence from this State, has caused my time, since my return

to Pahang on the 18th June last, to be very fully occupied.

1 have further delayed forwarding this Report, until the

Map, which has been prepared from time and compass

surveys made by three European members of the Expedition,

had been plotted. This has now been done in the Survey

Office of the Sèlângor Government, and I attach a copy of it

to this Report. (Enclosure 1.)

2. I have divided this Report into two portions; the

first dealing with the actual active work of the Expedition,

and the second part containing all the information - political

social, economic, and physical - which I have been able to

collect during my three months' sojourn in Trènggânu and

Kělantan.

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

2 Hugh Clifford

PART I.

3. In order to explain the reasons which led to th

Expedition it will be necessary for me to briefly recapitu

the events which occurred during the year 1894.

4. The Pahang Rebel Chiefs, who were driven from

this State in the autumn of 1892, having collected a larg

following of Kělantan and Trënggânu Malays, in June, 18

made a raid into the Těmběling District of Pahang. Owin

to the prompt action taken by the Chiefs of the Ulu Pah

District, this raid was quickly repelled, and the rebels w

pursued by Lt.-Col. Walker, c.m.g., and myself into Kělan

territory in July, 1894. Here they were enabled to el

pursuit by the assistance afforded to them by Ungku S

Râja and Dâto' Pânglîma Dâlam, two Kělantan Chiefs w

had been sent up river by the Râja of Kělantan ostensibly

the purpose of aiding us and co-öperating with us.

unfortunately had no authority to punish these Chiefs

their treachery, I withdrew to Pahang. In August I h

long interview in Singapore with the Siamese Commissio

from Puket, and proposed a scheme for finally dealing w

the rebels who, for the past two years, had been shelte

in Trënggânu and Kělantan. In the first instance, I state

it as my firm conviction that no reliance was to be placed

the assistance of the Chiefs and people of these States; an

therefore regarded it as an axiom that the Râjas of Kělan

and Trënggânu should not be permitted to take any p

whatsoever in any operations which might in future be und

taken against the rebels. My proposal, therefore, was th

if Siamese co-öperation was to be afforded to us, it sho

be confined to the presence of Siamese troops at the foo

the Kělěmang Falls in Trënggânu, in the Stîu and B

Rivers at points to be hereafter decided upon, and at Ku

Rek at the foot of the rapids in the Lěbir River in Kělan

All the natives living above these points were to be mov

down stream below the Siamese outposts, while I, wit

body of Malays and Dyaks, operated against the rebels in

country above the rapids. The natives of this portion of

Journal Malayan Branch [Vol. XXXIV, Pt. I,

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Expedition: Trengganu and Kelantan 3

country having been removed, the dakaits would no longer

be in a position to get either supplies or information.

5. These proposals were duly referred to the Govern-

ment of Siam, but without any practical result ensuing. In

the meantime, the Pahang rebels had been living for some

weeks in Ungku Sětia Raja's compound at Kěmuning in

Kělantan, where, by arrangement, they were relieved from

the embarrassing presence of their women and children, and

male non-combatants. While their party still comprised

some 60 souls, only a small proportion of whom were effective

fighting men, their movements were much hampered, large

quantities of supplies were necessary before a long march

could be undertaken, and the number of their women and

children otherwise proved a constant source of danger to

them when attempting to evade pursuit.

6. When the presence of the rebels at Kěmuning had

become so notorious that no one could any longer pretend to

be ignorant of the fact, an attempt to arrest them was made by

a Malay who is in the Siamese Service, and who bears the

title of Luang Pati Pak Pachakom. The rebels then removed

into Běsut, and took up their quarters in the Këmbîau, a

right tributary of the Běsut River, where they remained until

last May.

7. As no result followed my application to be allowed

to pursue the rebels into the Unprotected Malay States, I

wrote to the НопЪе the Colonial Secretary on 4th October

(Confidential ) renewing my application, and making

recommendations as to the Force which I proposed to take

with me, in the event of permission being granted to me to

cross the frontier.

8. The actual number of Rebel Chiefs still at large

had been reduced at this time to about a dozen; but the

gravity of the danger which threatened Pahang, so long as

these men continued to live within easy striking distance of

our border, must not be judged by the actual numerical

strength of the dakaits themselves. The real cause for appre-

1961] Royal Asiatic Society .

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

4 Hugh Clifford

hension lay in the fact that the rebels, ba

of the notorious Ungku Saiyid of Ku

already once succeeded in raising a follo

in Trënggânu and Kělantan to take par

Holy War against the Infidel. What the

might do again, and there was at that

believe that a similar following of fanat

for a like purpose, should the Rebel

though the raid made in June, 1894, h

real damage to life and property of

trading in Pahang, still a similar ra

disastrous consequences, and in any c

taken to punish the offenders, the sense o

during the last few years has done so

progress of this State, would not soon b

9. In a like manner had I merely be

force necessary to operate against the

have been necessary to cross the borde

dozen men. I was bound to take into consideration, how-

ever, the possibility, which I regarded as by no means remote,

of the Chiefs beyond the frontier actively assisting the dakaits

by force of arms. I did not, therefore, consider it wise to

cross the border with less than 100 rifles. As a perusal of

this Report will shew, my anticipations were based on a fairly

accurate estimate of the attitude which the Malays of

Trënggânu and Běsut were likely to assume towards those

engaged in the pursuit of the rebels.

10. In November, 1894, I was informed that, after pro-

longed discussion with the authorities in Bangkok, the pro-

posals made by me in August, and repeated in October, had

been referred to the Secretary of State for his consideration,

and, on 7th January, I received a telegram from His Excel-

lency the Governor, forwarded from Kuâla Lipis, informing

me that Her Majesty's Government had approved the pro-

posals contained in my letter of 4th October, always provided

that a Siamese Commissioner accompanied the Expedition.

I was further informed that I should be communicated with

later with regard to the probable date of the arrival of this

Journal Malayan Branch [Vol. XXXIV, Pt. I,

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Expedition: Trengganu and Kelantan 5

Siamese Official. On 21st January, I received a telegram

from His Excellency the Governor informing me that the

Commissioner had sailed from Bangkok in a Siamese gun-

boat on 18th January. I accordingly remained at Pěkan

daily expecting his arrival.

11. On 24th February I left Pěkan by boat in order

to pay a visit to Ulu Pahang, as rumours of a fresh raid from

Běsut were again rife throughout this State. On my way-

up-river I met Saiyid Hûsin and Saiyid Sěman, two young

Pahang men of the family of the Prophet Muhammad, who

are devoted to my interests, and who were returning from a

visit which, at my desire, they had paid to the States across

the border. They brought me word that the rebels were still

camped in the Kěmbíau River in the Běsut District, and that

they were again endeavouring to raise a following for the

purpose of raiding Pahang.

12. At 2 a.m. on 3rd March I reached Kuâla Lipis and

learned that Luang Visudh Parihar, and his colleague Luang

Sevasti Borirom, (commonly called Luang Swat), had arrived

via the Gâlas and Jělai Rivers, two days previously.

From Luang Visudh, who called upon me that after-

noon, I learned that an attempt had been made to reach

Pahang by sea, but that the Siamese gunboat had failed to

find the place it was seeking, and had then put back to Kuâla

Kělantan. Seeing that one or two ships were plying between

Singapore and Pahang during the whole of the close season,

it seems curious that if any real attempt was made to reach

Pahang by sea, it should not have been successful. The

Siamese Commissioners then proceeded up the Kělantan

River to Kuâla Lěbir, and up the latter stream to Kuâla Rek,

where Dato' Lêla Di-Raja was encamped at that time. My

men, Saiyid Hûsin and Saiyid Sěman, were at Kuâla Rek

while the Commissioners were there, and they informed me

that the Siamese were at some pains to spread abroad the

news that an expedition in pursuit of the rebels was about

to be undertaken under British and Siamese auspices, and

that the Lěbir River was the route decided upon. I ima-

gined, at that time, that this action was taken through ignor-

1961] Royal Asiatic Society.

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6 Hugh Clifford

ance on the part of the Commissioners of

which attaches in matters of this kind

absolute secrecy as to one's plans, etc., if i

should have a successful result. Since then I have had occa-

sion to doubt whether this view was not one which charity,

rather than reason, would incline one to adopt. From Kuâla

Rek the Commissioners descended the Lěbir and proceeded

to Pahang by the far longer route up the Gâlas River, and

eventually reached Kuâla Lipis as I have already had occasion

to mention.

13. The selection of the Gâlas route by the Commis-

sioners was further the cause of some little delay as the Dyak

portion of my Force, which for some weeks had been held in

readiness at Pěkan, was still at that station, and it was of

course impossible to make a start until they had arrived. I

at once sent instructions to the Officer-in-Charge at Head-

quarters to despatch the Dyaks upstream, and I also wrote to

the Pûlau Tâwar and Těmběling Chiefs asking them to hold

themselves in readiness to accompany me on an expedition

into the Lěbir District of Kělantan.

14. On 9th March, I received a telegram from His

Excellency the Governor, enquiring as to the purport of the

Commissioner's instructions, and in reply I informed His

Excellency that though the instructions in question were

written in Siamese, I was informed by the Commissioner that

he was ordered to accompany the Expedition for the purpose

of affording "every assistance" to the officer commanding it. I

told the Commissioner that it would very probably be found

necessary to bring pressure to bear upon the natives of

Trenggânu and Kělantan in order to ensure proper informa-

tion being supplied to us, and he said that he fully realised

that this would very likely be the case, and that he thought he

had sufficient authority to aid in doing all that was necessary.

15. In your confidential letter of 26th January, 1895,

the following passage occurs:- "From your letter under

"reply - (Confidential of the 21st January, 1895) -

"His Excellency infers that you consider the present condi-

Journal Malayan Branch [Vol. XXXIV, Pt. I,

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Expedition: Trengganu and Kelantan 7

"tions as being less likely to conduce to a successful issue

"of the expedition than they were when you made the

"application, and His Excellency agrees with you that this

"is probably the case, and would therefore leave it entirely to

"your discretion whether, in the event of the Commissioner

"bringing with him no definite information as to the where-

abouts of the rebels, the Expedition should not be aban-

doned. If, however, you decide that the prospects of a

"successful issue are still good, and that the effect of the

"Expedition, even if unsuccessful, would not be harmful to

"the interests of Pahang as regards Kělantan and Trěnggánu,

"then His Excellency approves of your proceeding by the

"course indicated and with the Force you name."

From this it will be seen that the responsibility of the

final decision whether or no this Expedition should be under-

taken, rested wholly with me; and before proceeding further

in my narrative, I must briefly explain the reasons which

caused me to decide that the interests of Pahang were best

served by embarking on this undertaking.

16. The information supplied to me by Saiyid Hûsin

and Saiyid Sěman, which I have since had an opportunity of

checking and have found to be entirely accurate, went to

shew that the rebels were not only living quite openly in

Běsut, but were also endeavouring to obtain supplies of arms

and ammunition, and were making other preparations for

another raid into Pahang. If it once came to be believed

by the people beyond our border that the Government of

Pahang was content to refrain from making any reprisals, so

long as dakaits who had raided Pahang villages were not

actually living in Pahang territory, I considered it certain

that the rebels would speedily find means to collect a large

following and to undertake another raid. Seeing that such

a raid was even then in contemplation, I had to ask myself

whether the interests of Pahang would be best served by act-

ing on the offensive, or the defensive. With the Police Force

at my command it is impossible to securely guard the 120

miles or so of difficult and densely-wooded country which

forms the boundary between Pahang and the neighbouring

1961] Royal Asiatic Society.

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

8 Hugh Clifford

States on the East Coast. Moreover,

reason to fear that in the event of a raid

and without warning at any one of the

along the border, it would prove at leas

that upon the Station at Kuâla Těmb

Pahang, therefore, was not, I concluded

efficiently on the defensive, and anythi

trouble within the State was calculated

her reputation in the Peninsula as a saf

to invest capital, or in which to seek a

fore decided to act on the offensive, f

ability to impress the natives of the wi

interior with the inadvisability of offe

which could send its emissaries into any

which a Malay could traverse, and whic

render life supremely uncomfortable fo

it. Never for a moment did I fail to ap

difficulty which I should experience in

since not only were they living in a count

friendly towards them, but, moreov

relieved of the presence of their women

would be able to traverse the country

rate of speed, and would be able to e

places for long periods upon comparativ

food.

Nevertheless, I considered that an Ex

Trěnggánu and Kělantan territory wou

effect upon the natives of those States,

in its main object of arresting the re

ensure the future tranquillity of Pah

derations was added the fact, of which I felt confident,

namely, that the whole extra expense which Pahang would

incur on account of this Expedition would not amount to

more than $4,000 or $5,000, whereas the cost of repelling a

raid would entail the expenditure of a far larger sum, if any

conclusions can be drawn from the experience of past years.

I accordingly had no hesitation in arriving at the conclusion

that the Expedition should be undertaken forthwith; and I

Journal Malayan Branch [Vol. XXXIV, Pt. I,

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Expedition: Trengganu and Kelantan 9

am still fully prepared to accept all the responsibility of that

decision.

17. On 13th March I left Kuâla Lipis for Kuâla

Těmběling, when I arrived the same afternoon. That even-

ing I was joined by Mr. R. W. Duff, Acting Superintendent

of Police, Mr. A. B. Jesser-Coope, Residency Surgeon, and a

portion of the Dyak Force. The remainder of the Dyaks,

and a number of the Malay Chiefs and their followers who

were to accompany the Expedition, arrived during the night

and during the following day. Imam Prang Inděra Stia

Raja, and the Pûlau Tâwar Chiefs, came in on the 15th

March, and that evening the Siamese Commissioners arrived

from Kuâla Lipls.

18. All this time I had allowed it to be universally

supposed that I intended to proceed straight to Kělantan via

the Sat River and I still allowed this impression to be

believed, even by the Siamese Commissioners, who had been

the first to make my supposed route and destination a matter

of public notoriety. Nevertheless, I had quite made up my

mind to avoid following a route by which my coming was

anticipated, and where I might be sure that no information,

other than such as was specially intended for me and mine,

would be obtainable. I was further impelled to proceed to

Trěngganu in the first instance by the receipt of a report,

which at this time was brought over to me from the Lěbir

district, to the effect that the rebels, having learned of our

intended Expedition into Kělantan, had moved from the

Běsut further into Trěnggánu territory with a view to elud-

ing pursuit. I judged from the knowledge which I possessed

of the country across our frontier that the rebels, if they

decided to finally quit Běsut, would most probably move into

the Trěngan and take up their quarters in the Bêwah, a left

tributary of the former river, which had been visited and

selected by them in 1894 as a suitable hiding place in case of

emergency. I therefore decided to follow the Spìa route

into Trěngganu, traversing the difficult country lying be-

tween the Těmběling and Trěngan Rivers, over which I had

passed in July of the preceding year.

1961] Royal Asiatic Society .

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

10 Hugh Clifford

19. On the 16th I wrote a full report, f

to the НопЪ1е the Colonial Secretary, exp

and on 17th March I left Kuâla Těmbělin

ascent of that river. I camped that nigh

and the following afternoon I reached Trě

the Těmběling rapids. On 19th March I

Kěndiam, having passed up the rapids wit

on mid-day on the 20th March Kuâla Sa

21st March I despatched Saiyid Sěman t

letters to the Dâto' Lêla Di-Raja, from the

sioner, informing him that we were about to

With the exception of the Commissioner t

in camp who knew, at this time, that I ha

the Spìa route, and the bearer of the le

Di-Raja believed that we should shortly fo

Sat and into Kělantan territory.

20. The whole of 21st March was spe

our supplies into cooly-loads, making the â

basket-work knapsacks, in which jungle-b

their packs, collecting more bearers, and co

parations for departure. On the 22nd Mar

was made, the Expedition moving up the

intense surprise of all its native members

Lûbok Ipu in the Spìa River at about 5

21. On 23rd March a start was made at 5.45 a.m. and

Kampong Rěmih, the last village on the Spìa, was passed

before 7 a.m. From this place, until Kampong Malâka on

the Trěngan is reached, no inhabited country is passed

through. At about 10 a.m. we got into the rapids and conti-

nued to labour up them all day, camping at Pâsir Bulan at

the head of the first flight of rapids in the afternoon. The

Siamese Commissioner did not arrive until 8.30 p.m. having

met with an accident, one of his boats being smashed and

having to be abandoned in the rapids. Several other boats

had lagged somewhat during the day, and as I waited until

they had all arrived, we did not get off on the morning

of the 24th March until 7.30 a.m. Kuâla Reh, the point

whence the track leads across into Trënggânu territory, was

Journal Malayan Branch [Vol. XXXIV, Pt. I,

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Expedition: Trengganu and Kelantan 11

reached by me just before 6 p.m. the second flight of rapids

having been negotiated without accident; but the Siamese

boats, and those belonging to some the Pûlau Tâwar Chiefs,

whose men were less expert in ascending the rapids than are

the natives of the Těmběling, did not arrive until 1 p.m.

on 25th March.

22. When assembled at Kuala Reh, my party num-

bered, all told, 252 men; and was composed as follows: -

Europeans 3, Malays 190, Dyaks 39, Sikhs 8, Sâkai (aboriginal

natives of the Peninsula) 2, and Siamese 10. The effective

fighting men were 3 Europeans, 55 Malays, 39 Dyaks, and 8

Sikhs, making a total of 105 rifles. The remaining 147

Malays were bearers and personal attendants of the Euro-

pean Officers.

23. The main difficulty which attends the movement

of an Expedition of this kind through uninhabited jungles

is of course that of transporting with it a sufficient quantity

of supplies. When I left Kuala Sat I had with me 606

gantang of rice or 2,424 full rations. The daily rations of

the camp amounted to 60 gantang and 2 chûpak of rice, and I

had, therefore, barely ten days' full rations for all my people.

By 26th March, on the morning of which day the boats were

left and the march across country was begun, the actual

quantity of rice in camp amounted to 364 gantang, equiv-

alent to 2,366 lbs., or between 70 and 75 cooly-loads. Each

European's baggage was confined to three cooly-loads, of

which his sleeping mat and clothes formed two loads, and his

despatch box a third. The medical stores required two

coolies to carry them, and ten bearers were needed to carry

the ghi and tinned milk which was considered necessary in

order to enable the Sikhs to live on a rice diet. Tobacco

for the men made up another two loads, and eight men were

employed carrying ammunition. Twenty-five coolies were

told off to carry the baggage of the Siamese Commissioners,

than which a more heterogeneous collection of unnecessary

rubbish with which to encumber oneself on a jungle journey

was never devised by the wit of man. Of the remaining 16

coolies, four men were left behind incapacitated by sickness,

1961] Royal Asiatic Society .

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

12 Hugh Clifford

and the rest were employed carrying the

Native Chiefs.

24. All the members of the Expedition were required

to live on a rice diet. This is the natural staple of the

Malays and Dyaks who formed the immense majority of the

men of whom the party was composed, and it would have

added vastly to the expense of the Expedition had other forms

of rations been supplied. In speaking of the expense I do

not refer to the cost of such rations, but rather to the cost of

transport, every cooly-load which does not consist of rice

entailing the employment of a rice-bearing cooly in order to

transport the ten days' rations for the man so engaged. On

long jungle marches 5 gantang of rice is a heavy load for a

bearer, and in ten days he will himself consume half that

amount of rice leaving only 2 gantang , or ten days' rations

for one man, which can be devoted to the common use. It

is this consideration which renders it imperatively necessary

to cut down personal baggage to the lowest point, and to

avoid, as far as possible, employing any coolies to carry packs

other than loads of rice. An exception, as I have noted, was

made in favour of the Sikhs for whom ghi and milk were

considered necessary, but should I ever again have to organise

a similar Expedition, no Sikhs should be detailed to accom-

pany it. The men I had with me behaved remarkably well,

and lived with little difficulty on their rice ration, but they

are altogether unsuited for the work of travelling in Malay

jungles, and up and down Malay rivers, and the extra trouble

which their presence involves is not compensated for by any

corresponding advantage.

25. On 26th March the morning meal was cooked be-

fore dawn, and all the coolies were loaded up and a start

made at 6.50 a.m. Our route lay up the Reh and then up

the Kěněring River, a left tributary of the former stream.

The path followed the bed of the river, the water of which

is very shallow, but as the bed is rocky and strewn with sharp

stones it is very tiring and uncomfortable walking. At

11.20 a.m. we reached Sangka Dûa, a spot in the jungle, at

the foot of the mountains, where the Kěněring divides into

Journal Malayan Branch [Vol. XXXIV, Pt. I,

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Expedition: Trengganu and Kelantan 13

two streams of equal size. At 1 p.m., all our party having

assembled and rested, we began the ascent of Gunong Ulu

Kěněring, a mountain which is about 2,000 feet above the

level of the sea. The summit was reached at 2.25 p.m., and

here a much-needed halt was called to enable the party to

collect. At 3 p.m. we began the descent into Trěnggánu ter-

ritory, and at 4.10 p.m. we camped on the spot selected by

me for a similar purpose on 21st July, 1894.

26. On 27th March an early start was made and the

Pring was struck at 8 a.m. Following the Pring we reached

the point where that stream falls into the Trěngan on its left

bank at 2.20 p.m. and camped there. Our march had been

a very slow one as we had frequently halted to await the

Siamese, who, however, failed to put in an appearance that

night. Luang Swat, we learned afterwards, had strained him-

self during the climb of the preceding day, and was unable

to travel except very slowly.

27. On 28th March the men were set to work making

rafts, and when this was completed 95 of the coolies were

given a half ration of rice each and sent back to Pahang. A

sufficient quantity of stores to take them back to their homes

was awaiting them at Kuala Reh. At 3 p.m. all the rafts, 55

in number, being ready, a start was made, and at 5 p.m. we

camped on the right bank of the Trěngan just above Jěram

Kuâli.

28. On 29th March an early start was made and the

head of the Pâling Falls was reached at 11.30 a.m. I decided

to camp here for the night and to send Panglima Kâkap Hûsin

and a small party at Dyaks and Malays down to the foot of the

falls whence they could scout the Bêwah River.

29. On 30th March, leaving our rafts at the head of

the Pâling Falls, which are quite impassable, we marched

down the right bank of the Trěngan and reached Galas, a

point below the falls, at 11.30 a.m. Here all hands set to

work to make fresh rafts, a work which was not completed

until mid-day on 31st March, 48 rafts being required. At

1961] Royal Asiatic Society .

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

14 Hugh Clifford

4.15 p.m of that day messengers reached me

Kâkap Hûsin, who was camped at Kuâla Bê

that he had examined that river carefully an

traces of the dakaits for whom we were seekin

30. On 1st April I moved the whole Force

and camped at Malâka, where no news of

preceded us. The Siamese Commissioners

behind when I reached Malâka; and it accord

to question the Pènghûlu, a man named T

whom I was already acquainted, with regard

of the rebels or any of their people in his d

reluctance he shewed to make oath in confirmation of his

statements that he had no information concerning any of the

people for whom I was seeking, I felt certain that he was

withholding something from me, and on the arrival of the

Commissioner I pointed out that the only way in which he

could be made to speak would be by bringing pressure to

bear upon him. The Commissioner then said, to my intense

surprise, that he had no power to exert any such authority in

Trěnggánu, and that he could not be a party to any such

action. He further expressed himself of the opinion that

"coaxing" would have the desired effect. I told him that

after many years spent among Malays, I was in a position to

assure him that any such course would be ludicrously in-

effectual, and that unless he was in a position to aid me in

case of this sort his presence with the Expedition, which had

already done much to delay me, was altogether objectless.

He expressed himself as very much grieved at not being

armed with the necessary authority to give me the assistance

I needed, but said that he was bound to obey his instructions,

which I fully admitted, though I could not but recall to his

memory the statements which he had made to me at Kuâla

Lipis concerning the purport of those instructions.

31. On 2nd April, I started down the Trěngan with all

my people, intending to go to Jënâgar, the market below the

Kělěmang Falls, on the Trěnggánu River, where I should be

able to obtain fresh supplies. Owing to heavy rain a start

was not made until 11 a.m. Ot 1.15 p.m. Kuâla Trěngan

Journal Malayan Branch [Vol. XXXIV, Pt. I,

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Expedition: Trengganu and Kelantan 15

was reached, at which point the Kěrbat and Trěngan Rivers

meet and from one stream which bears the name of the

former river. Below this point the Kěrbat is studded with

enormous granite boulders, and a quarter of a mile lowe

down Jěram Kěntir, the first of the 24 rapids which lie be

tween Kuala Trěngan and Kuêla Trënggânu Ulu, is reached.

At this time the water in the river was very high, and th

rapids were extremely formidable. I camped for the night

on a large sand bank at the foot of Jěram Panjang, the nint

rapid from the head of the falls, and the next day reached

Jěram Bûching, at the foot of the falls, at 2 p.m. Our pro

gress was somewhat slow as we had nearly 50 rafts with us,

many of which had to be unloaded before the rapids could

be shot.

32. At 2.40 p.m. on 3rd April we reached Kuâla

Trënggênu Ulu, where the Kěrbat and Trënggânu Ulu

Rivers meet and form the Trënggânu River. A stockade

had been built by orders of the Sultan to command this point,

ostensibly as a defensive measure against the rebels, but really

to repel any invasion from Pahang. It was exceedingly ill-

constructed, and would have proved equally ineffective for

either purpose. Another similar stockade had been con-

structed at Kampong Mělor, a village between Kuâla Lansir

and the head of the Kělěmang Falls, which I reached at

3.30 p.m.

33. Panglîma Kâkap Hûsin had preceded me, and from

him I learned that on his arrival there he had been mistaken

by the Pënghûlu To' Bakti, for one of the rebels. Under

this delusiçn, which Panglîma Kâkap Hûsin was by no means

anxious to dispel, To* Bakti informed him that the rebels

were living in the Běsut River, and the Râja Sëmâil or Râja

Weng, as he is variously called, had been recently sent across

by the Sultan to warn them that an Expedition was contem-

plated with the object of pursuing them. He also stated that

during the last flood (November, 1894), Bahman and Mat

Kîlau had gone down the Trënggânu River and had paid a

visit to Ungku Saiyid at Pâloh, and by his agency had been

permitted to reside peacefully in the Bësut, the people of

1961] Royal Asiatic Society.

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

16 Hugh Clifford

that district being instructed to aid them

B'akti further mentioned that Râsu's son

Nuh, was at that time living in the Měn

falls into the Trěngan, a short distance ab

right bank. To* Bakti's face was a study w

his village, and he realised, for the first tim

imparting all this information to those w

in pursuing the rebels, and not one of th

34. Just before sundown the Commis

their rafts having once more met with an

way down river, and with them came To

whom they had brought down river at m

sent for Luang Visudh and asked him wh

had obtained by means of the process of "

he pinned his faith; and I was in no degree

that he had no information of any kind

told him what I had learned, and insisted

at once sent on board my raft. I then s

full confession from him, without anyth

of corporal punishment becoming nece

having at last found his tongue, confirme

had said; and reluctantly admitted that

even then living within a mile or two of h

35. On 4th April I sent Mr. Duff and a

Dyaks and Malays up the Kěrbat and Trěn

arrest of Haji Mat Nuh; and I, with the r

moved on down river to the head of th

marched round them, and camped at P

just below Jěram Lentang. On 5th Apr

Jěnágar where I set to work collecting f

into camp pending the return of Mr. D

here I was visited by all the Râjas, Chiefs

the district, and had an opportunity, duri

of conversation which I had with them, of

derable amount of varied information ab

country. Luang Swat accompanied me

Luang Visudh went up river with Mr.

Journal Malayan Branch [Vol. X

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Expedition: Trengganu and Kelantan 17

copy of the instructions which I gave to Mr. Duff on this

occasion. (. Enclosure 2 •)

36. On the evening of the 6th April Mr. Duff and his

party returned, having effected the arrest of Haji Mat Nuh.

He brought with him the 12 women and children who were

with Haji Mat Nuh at the time of his arrest. I enclose a

copy of Mr. Duff's report made to me on his arrival at Jěnagar.

(Enclosure 3.)

37. The policy which it was the object of the Siamese

Commissioners to adopt was now daily becoming more and

more plain. The influence of the Siamese in Trěngganu is

purely nominal, as I shall hereafter have occasion to shew,

and their object clearly was to endeavour to strengthen that

influence at our expense. To this end they lost no oppor-

tunity of covertly assuring the people of Trěngganu that the

latter had nothing to fear from me and my Force, since we

were accompanied by Siamese Officiais whose sole object was

to befriend and protect the natives of the country from our

wrath, no matter what ill-deeds of theirs might have aroused

it. Matters came to a point when the Commissioner Luang

Visudh took the action, described by Mr. Duff in his report,

with regard to Imam Hûsin and the people of Ilor, and when

I became aware of what had occurred, I at once decided to

abandon all idea of persevering with the Expedition until a

sounder basis, upon which to work, had been arrived at. I

accordingly marched my men down river on 8th April and

camped in the village of Bûlor near Kuala Bram, with the

intention of leaving my Force there, and thence proceeding

to Kuala Trěngganu, in order to communicate with

Singapore.

38. It is worthy of note that while in the Ulu the

Commissioner was exceedingly anxious to excuse To' Málek

and the other Trěnggánu natives who had withheld informa-

tion, and who had aided in concealing and feeding the rebels,

on the grounds that they were certainly acting under orders

from their Sultan, and so could not be blamed for playing

us false. This theory, which is undoubtedly a correct one,

1961] Royal Asiatic Society .

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

18 Hugh Clifford

was entirely abandoned by the Commissione

at Kuâla Trënggânu, he then being anxious o

sion to express his opinion that the Sultan w

could to aid us, and was only unable to do s

because his authority in his country was so l

39. On 9th April the Pënghûlu Baiai,

younger brother to To' Mâta-Mâta, and Wan

from Kuâla Trënggânu with boats, presents

and civil messages from the Sultan welco

country. On 10th April, leaving the Force u

mand of Mr. Duff, and taking ten Malays w

ceeded to Kuâla Trënggânu, where I arrived

6 p.m. I was here received by a guard of ho

men, by Tungku Běsar, Tungku Mûsa, Tu

all the principal Râjas and Chiefs, who con

house which had been prepared for my

Sultan was awaiting my arrival at the Balai

myself for that day, as some repairs were n

wardrobe. During the evening I was visited

cipal Chiefs, to whom I related what had occu

journey through the interior of Trënggân

at once sent up river to bring in To' Mále

both these men having been allowed to retur

above the Kělěmang Falls by the Commissio

knowledge, and most decidedly without my

add that the action of the Trënggânu autho

spontaneous, and was not due to any deman

being, at this time, quite ready to sacrifice a

headmen if, by so doing, they were enabled

appearance of hearty cooperation with us.

his Chiefs were exceedingly civil and did al

ensure my comfort, the Sultan insisting on sup

my men with food cooked in the palace dur

of our stay at the Kuâla. Indeed, never was

guest treated with greater hospitality, nor w

rate professions of friendship and goodwill.

40. It is worthy of remark that though L

represented the Government of Siam, he

Journal Malayan Branch [Vol. XXX

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Expedition: Trengganu and Kelantan 19

land as best he could, and met with very scant courtesy from

the people of Trěngganu.

41. On 11th April I had a long interview with the

Sultan in the Bâlai, to which I was conducted by a guard of

spearsmen, and I again described all that had occurred, and

all the information I had gained while in the interior of

Trěnggánu.

42. On 12th April I had an official interview with

Ungku Saiyid, who is a man of a remarkable personality, and

who wields an extraordinary influence over the superstitious

and somewhat fanatical Muhammadans of Trěngganu. I

had a second and more private interview with the Saiyid

during my stay at Kuâla Trěnggánu, and on both of these

occasions he lied to me concerning his connection with the

rebels with a directness and a stolidity of countenance which

accorded ill with his saintly reputation. At this time I did

not wish to shew my hand, and I accordingly received all his

false statements, many of which I was in a position to entirely

disprove, with every appearance of belief; and contented my-

self with making notes of all he said for use at later date.

43. On 16th April the Siamese gunboat Mukut Rajaku -

mar arrived with Mr. Beckett, Acting British Consul, and

Phya Dhip Kosa, the Governor of Puket, on board. On that

day and the next Mr. Beckett and myself had interviews with

the Sultan, at which His Highness made all manner of pro-

fessions of helplessness to aid us, in spite of his anxiety to do

so. Nothing, of course, was gained by these interviews, but we

were able to arrange for the issue of a chap - a letter of

authority from the Sultan - empowering me and the Siamese

Commissioners to summarily punish any persons whom we

had good reason to believe were aiding, concealing, or feed-

ing the rebels, or who refused to supply us with information

concerning them, which we knew them to possess. I enclose

a copy and translation of this chap. ( Enclosures 4 and 5.)

44. On 26th April I received final instructions from

Singapore, and on 27th April I dined with the Sultan and

1961] Royal Asiatic Society.

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

20 Hugh Clifford

left Kuâla Trënggânu the following mor

29th I reached Kuâla Bram at noon and spen

day in making preparations for my depar

viously despatched the prisoner Haji Mat

with a police escort, the Siamese Commissio

agreed to his removal.

45. There had been a good deal of sickn

men encamped at Kuâla Bram during m

found it necessary to order Imâm Prang Ind

about a dozen other men to return by sea t

46. Meanwhile, Mr. Duff with 1 1 Dyaks

Saiyid Sěman, Khatib Pandak, two other Ma

4 Sikhs, 20 rifles in all, had left Kuâla Tělěm

and Běsut districts on 25th April, my orde

to go across to the Stîu, and thence to the B

to driving the rebels out of that country in

trict; I, with a small body of men, undertak

to the Lěbir via Ulu Kěrbat so as, if possi

rebels between two fires.

47. On 30th April I broke camp at Kuâla Bram and

halted that night at the foot of the Kělěmang Falls, reaching

Kampong Mělor at 2 p.m. on 1st May. Here I camped for

the night in the Trënggânu authorities' stockade, which had

been greatly strengthened since we passed down river - a

rather significant fact. I turned out all the men who were

holding this stockade to make room for my own people.

48. The Siamese Commissioner sent to me after my

arrival att Kampong Mělor and asked to be allowed to make

the necessary arrangements as regarded boats, etc., to which

I consented. The result was, however, that on the morning

of 2nd May half the boats had disappeared, having been

hidden by their owners, and when I required the number

that had been promised to me, and which had been collected

by my own people the night before, Luang Visudh was unable

to produce them. Seeing that the people entirely ignored

his orders, I was forced to take the matter into my own hands,

Journal Malayan Branch [Vol. XXXIV, Pt. I,

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Expedition: Trengganu and Kelantan 21

and was speedily supplied with all the boats I required, and

also with the guides who were needed to accompany Mr.

Jesser-Coope's party overland to Stîu and Běsut, where I had

ordered them to proceed to support Mr. Duff.

49. At 7 a.m. Mr. Jesser-Coope and his party started

to march across to Tâpah in Ulu Pûeh. His Force consisted

of 5 Sikhs, 8 Dyaks, and 24 Malays, 10 of whom were bearers.

Luang Swat accompanied him. They carried ten day's sup-

plies with them. At 7.20 a.m. I got off with 45 Malays, 22

of whom had guns, and 14 Dyaks, making with me 37 guns,

and a total of 60 men. Luang Visudh, being left to his own

resources - as I did not feel called upon to insist on the

Trěngganu natives supplying him with boatmen, being of

opinion that I had no right to interfere between him and

them in such a matter - was unable to obtain sufficient men

to pole his boats, and, as I learned from him afterwards, was

put to some straits in order to follow me up stream.

50. I camped at the head of the Kěrbat Rapids on the

night of the 2nd, and on the night of the 3rd I camped at

Pûlau Lâbit close to Alu, the last village in the upper Kěrbat.

Here I left a note for the Siamese Commissioner saying that

I could not afford to wait for him, as every day meant the

consumption of a certain quantity of rice, but that I trusted

that he would come after me as quickly as possible.

51. On 4th May I began the march across to Kělantan

and camped at 2.30 p.m. at Kuâla Děkoh, still in Trěnggánu

territory. Very heavy rain, which fell continuously drench-

ing us to the skin, and sending the rivers up 6 ft. in three

hours, prevented me from making a longer march on this day.

52. On 5th May I continued my march, and crossing

the border into Kělantan at 7 a.m., reached Kuâla Alor on

the P'ërtang at 9 a.m. Having scouted the rebel's former

camps up the Pěrtang, and having found no traces of them,

I set all my people to work making rafts, and at 4 p.m. I

started down the Pěrtang and reached the point at which that

river falls into the Lěbir at dusk. Luang Visudh had arrived

1961] Royal Asiatic Society.

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

22 Hugh Clifford

without his baggage during the day, but h

Kuâla Fěrtang at 6 a.m. on 6th May, at wh

down the Lěbir.

53. About a mile below Kuâla Pěrtang we found traces

of a camp which had been occupied two days before by about

a dozen men, who, as the gun-rests shewed, had been armed

with firearms. The tracks indicated that this party had been

travelling by boat and had been going up stream. I there-

fore concluded that this camp had been occupied by the

rebels who had fled from the Besut on the approach of Mr.

Duff's party; and, as they were certainly not in the Pěrtang,

I concluded that they had returned to their old haunts at

Kuâla Ampul. I accordingly went back to Kuâla Pěrtang,

camped there till 3.20 p.m. when I began to pole up the

Lěbir River on our rafts, and reached a point just below

Kuâla Ampul at 8 p.m. Here I waited, being devoured by

sand-flies the while, until 1 1 p.m., when I went on to Ampul

and surrounded the village, fully expecting to find the rebels

encamped there. Great was my disgust when I found that

I had been following a body of local men who had been seek-

ing buffaloes down stream, and who happened to have been

armed with half-a-dozen match-locks. Having assured myself

by due enquiries that this was really the case, I camped my

men in the village for the night, and started down the Lěbir

again on the morning of the 7th May. That afternoon I

camped early at Kělěbing - a village which, in common with

all those between Kuâla Ampul and Lanchar, had been

deserted since August, 1894 - and the men worked until

midnight enlarging the rafts.

54. On 8th May a start was made at 6.30 a.m., and at

1.10 p.m. Lanchar, the first inhabited village which we had

passed since we left Kuâla Ampul, was reached. Here I

learned that the Commissioner's baggage, which had been

left behind, as already mentioned, in Ulu Trënggânu had

been brought across by his people, acting under his orders,

by the Lěbir Kěchil route, and that this party had gone

straight on down river ahead of us, spreading everywhere the

report that I and my people were coming. Had I not been

Journal Malayan Branch [Vol. XXXIV, Pt. I,

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Expedition: Trengganu and Kelantan 23

delayed by making that visit to Kuala Ampul, I should still

have been far ahead of the Commissioner's baggage, and my

approach would not have been expected. As it was, how-

ever, every soul in the Lěbir knew that I was about to arrive,

and had anyone wished to send a word of warning to the

rebels, it could have been done before I was on the spot to

prevent it. I spoke to the Commissioner on this subject, and

pointed out to him that unless he followed implicitly the

routes I gave him, he would be apt to interfere seriously with

my plans and arrangements. He expressed himself as being

very much distressed at what had occurred, and I believe

that the mistake was the result of ignorance and not of

design. As it happened, it did no harm, though the conse-

quences might have been very serious.

55. At 3.30 p.m. I reached Kuâla Aring, where a watch-

house, which is called a Pèntìat in this part of the country

had been erected by the Dâto' Lêla Di-Raja's orders with a

view to guarding against the return of the rebels to the Lěbir

district. Here I saw Haji Méntri, the man who ferried the

rebels across the Lěbir River at Těni on 8th August, 1894,

who was loud in his professions of repentance, and of good

intentions for the future, to neither of which I attached very

much importance. That night I camped at Kuâla Mîak,

where the river of that name falls into the Lěbir on its right

bank. Here another watch-house had been erected in order

to guard this route from Běsut.

56. On the morning of 9th May I left the main body

of my people encamped at Kuala Mîak, in order to keep watch

over the routes leading from Běsut; by which tracks I thought

that it was probable that the rebels would attempt to escape

if they were driven from the Kěmbíau by Mr. Duff's party.

Taking ten men with me, and accompanied by Luang

Visudh, I pushed on to Kuâla Rek, below the Lěbir Rapids,

where I arrived at sun-down, and was most courteously

received by Dâto Lêla Di-Raja, the Chief in charge of the

Lěbir district, who conducted me to a house which had been

specially built for my accommodation.

1961] Royal Asiatic Society.

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

24 Hugh Clifford

57. Half an hour after midnight, on

Duff arrived from Běsut by the Rek rout

that had occurred since he left Kuâla T

April. I enclose a copy of his Report. {E

after daybreak I sent for Luang Visudh, a

recited all that had occurred during hi

Běsut. I then asked Luang Visudh: I. Whet

of my party proceeding to Běsut, he had suf

on behalf of this Government, to ensure r

being supplied to me. without it becoming

use of the powers vested in me by the Su

Whether he had sufficient influence to ensure no hostile

action being taken against us, by the Chiefs and people of

Běsut, if I found it necessary to make use of the powers of

punishment granted to me by that chap. Luang Visudh

replied that he, as the representative of the Siamese Govern-

ment, had not sufficient influence in Trënggânu territory to

enable him to give a guarantee on either point.

58. It appeared to me to be evident, from the informa-

tion brought in to me by Mr. Duff, that if I entered Běsut

I must be fully prepared to fight the whole of that district,

and though I believed that the Force at my command was

quite sufficient to act as a punitive Expedition against this

portion of Trënggânu, I was not armed with sufficient

authority from His Excellency the Governor to take any such

action, until I had first communicated with Singapore.

Judging from the information which Mr. Duff had obtained,

it seemed highly improbable that the rebels would leave

Běsut until a Force had been led into that district which

should render their position there untenable. So loyally

were they befriended by Tungku Chik and his people, that

they could hardly hope to find safer quarters than those they

were at present occupying in any other part of the Peninsula.

I discussed the matter fully with Mr. Duff, who, having been

on the spot, was better able than I to form an opinion, and

I eventually decided to adopt the following course: to collect

all my people at Kuâla Rek, where supplies could be obtained

more easily and more cheaply than in any other part of the

Journal Malayan Branch [Vol. XXXIV, Pt. I,

This content downloaded from

202.45.133.243 on Wed, 08 Jun 2022 05:14:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Expedition: Trengganu and Kelantan 25

Lěbir River; to report fully on the situation to His Excellency

the Governor, and myself to proceed to Kóta Bharu there to

await instructions as soon as Mr. Jesser-Coope and his party

should have reached Kuala Rek.

59. In pursuance of this plan, I called all the men I

had left at Kuâla Mîak down to Kuâla Rek, and despatched

my report to Kóta Bharu for transmission to Singapore. I

also sent scouts - Kělantan natives - across to the Běsut to

see what was going on beyond the frontier; to learn what

they could with regard to the whereabouts of the rebels; and

to ascertain where Mr. Jesser-Coope was.

60. At 6 p.m. on 18th May these scouts returned and

reported that they had only gone down the Běsut River as

far as Běrangan, and that they had fled thence, being warned

by their relations living in the place that they were suspected

of being spies, and that orders had been given for their arrest

by the Běsut authorities. Tungku Chik, they said, had made

his sudden departure from Tâsek on 8th May, as reported by

Mr. Duff, because he declared that he could not have res-

trained himself from attacking Mr. Duff had he remained in

the same camp with him for another 24 hours. The scouts

had been unable to learn the present whereabouts of the

rebels, but they said that the name of the Kěmbíau River,

which they had known from infancy, had been changed to

Sûngai Châbang Dua, or Sangka Dua, by the orders of