Professional Documents

Culture Documents

143ARajesh Soni Vs Mukesh Verma

143ARajesh Soni Vs Mukesh Verma

Uploaded by

Ajay SarmaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

143ARajesh Soni Vs Mukesh Verma

143ARajesh Soni Vs Mukesh Verma

Uploaded by

Ajay SarmaCopyright:

Available Formats

Page 1 of 12

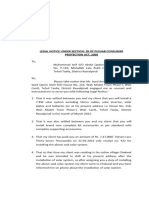

AFR

HIGH COURT OF CHHATTISGARH, BILASPUR

CRMP No. 562 of 2021

Order Reserved on : 22.06.2021

Order Delivered on : 30.06.2021

Rajesh Soni, S/o Shri P.R. Soni, Aged About 44 Years, R/o Opposite

Harsh Tower, Devpuri, Tehsil & District- Raipur (C.G.)

---- Petitioner

Versus

Mukesh Verma, S/o Late Shri J.P. Verma, Aged About 57 Years, R/o

Opposite Suraj Kirana Store, Nandi Chowk, Tikrapara, Tehsil &

District- Raipur (C.G.)

---- Respondent

For Petitioner : Mr. D.K. Gwalare, Advocate.

Hon'ble Shri Justice Narendra Kumar Vyas

CAV Order

1. The petitioner has filed present petition under Section 482 of

Cr.P.C. challenging the order dated 24.12.2019 passed by

Judicial Magistrate First Class, Raipur (C.G.) in Complaint

Case No. 1777/2019 wherein learned trial court has allowed

the application filed by the complainant under Section 143A of

the Negotiable Instrument Act, 1881 (for short “the Act, 1881”)

and has directed the petitioner to pay 20% of the cheque

amount, as well as order dated 06.03.2021 passed by 11 th

Additional Sessions Judge Raipur, District- Raipur (C.G.) by

which the criminal revision filed by the petitioner has been

rejected.

2. The brief facts, as projected by the petitioner, are that

complainant/ respondent has filed complaint against the

petitioner under Section 138 of the Act, 1881 on 09.01.2019

before Judicial Magistrate First Class, Raipur, District- Raipur

(C.G.) mainly contending that the petitioner had given a

Page 2 of 12

cheque dated 26.11.2018 amounting to Rs. 6,50,000/- to the

complainant. The complainant has deposited the cheque on

28.11.2018 in the account maintained by him in Central Bank

of India, Branch- Chhattisgarh College, Raipur. The said

cheque was dishonoured and returned due to insufficient fund

on 14.12.2018, therefore, the offence under Section 138 of the

Act, 1881 has been committed by the petitioner.

3. The complainant has sent a legal notice to the petitioner on

17.12.2018 as petitioner has not paid the amount of cheque,

therefore, the complainant has filed a Complaint Case No.

1777/2019 before Judicial Magistrate First Class, Raipur, The

learned Judicial Magistrate First Class taking cognizance on

the complaint, issued summon to the petitioner. On

04.05.2019, the complainant has filed an application under

Section 143A of the Act, 1881 contending that the charges

have already been framed wherein he has denied the charges

levelled against him. Further contention of the complainant is

that as per the provisions of Section 143A of the Act, 1881, if

charges have been framed against the accused, the interim

compensation can be ordered by the Court to the extent of

20% of the cheque amount, therefore, he prayed for grant of

20% of the amount as interim compensation.

4. The learned Judicial Magistrate First Class vide its order dated

24.12.2019 considering the amended provisions of Section

143A of the Act, 1881, directed the accused to pay 20% of the

cheque amount as compensation, failing which proceeding

under sub-section (v) of Section 143A will be initiated against

petitioner, thereafter fixed the case for hearing on 20.01.2020.

5. Being aggrieved by the aforesaid order, the petitioner

preferred Criminal Revision No. 102/2020 before the Sessions

Judge, Raipur which was transferred to the Court of 11 th

Additional Sessions Judge, Raipur, District- Raipur. The

learned 11th Additional Sessions Judge vide its order dated

06.03.2021 dismissed the revision by recording a finding that

there is no illegality and irregularity in the impugned order

Page 3 of 12

passed by the learned Judicial Magistrate First Class, Raipur

and same is inconformity with the amended provisions of

Section 143A of the Act, 1881. Both these orders have been

challenged by the petitioner in the present petition.

6. Learned counsel for the petitioner would submit that as per

amended provision of Section 143A of the Act, 1881, grant of

interim compensation is not mandatory and it is discretionary,

therefore, it is not necessary in every case to grant 20% of

cheque amount as interim compensation. He has drawn

attention of this Court towards amended provision of Section

143A of the Act, 1881, which is extracted below:-

“143A – Power to direct interim

compensation- (1) Notwithstanding anything

contained in the Code of Criminal Procedure,

1973 (2 of 1974), the Court trying an offence

under Section 138 may order the drawer of the

cheque to pay interim compensation to the

complainant-

(a) in a summary trial or summon case,

where the drawer pleads not guilty to the

accusation made in the complaint; and

(b) in any other case, upon framing

charges.

(2) The interim compensation under sub-

section (1) shall not exceed twenty per cent of the

amount of the cheque.

(3) The interim compensation shall be pad

within sixty days from the date of the order under

sub-section (1), or within such further period not

exceeding thirty days as may be directed by the

Court on sufficient cause being shown by the

drawer of the cheque.

(4) If the drawer of the cheque is acquitted, the

Court shall direct the complainant to repay to the

drawer the amount of interim compensation, with

interest at the bank rate as published by the

Reserve Bank of India, prevalent at the beginning

of the relevant financial years, within sixty days

from the date of the order, or within such further

period not exceeding thirty days as may be

directed by the Court on sufficient cause being

shown by the complainant.

(5) The interim compensation payable under

this section may be recovered as if it were a find

Page 4 of 12

under section 421 of the Code of Criminal

Procedure, 1973 (2 of 1974).

(6) The amount of fine imposed under section

138 or the amount of compensation awarded

under section 357 of the Code of Criminal

Procedure, 1973 (2 of 1974).”

7. Learned counsel for the petitioner would rely upon the

judgment of Madras High Court in L.G.R. Enterprises &

another Vs. P. Anbazhagan1, and drew attention of this Court

towards para 18 of the judgment, which reads as under:-

“18. A careful reading of the order passed by the

Court below shows that the Court below has

focussed more on the issue of the prospective /

retrospective operation of the amendment. The

Court has not given any reason as to why it is

directing the accused persons to pay an interim

compensation of 20% to the complainant. As held

by this Court, the discretionary power that is

vested with the trial Court in ordering for interim

compensation must be supported by reasons and

unfortunately in this case, it is not supported by

reasons. The attempt made by the learned

counsel for the respondent to read certain

reasons into the order, cannot be done by this

Court, since this Court is testing the application of

mind of the Court below while passing the

impugned order by exercising its discretion and

this Court cannot attempt to supplement it with

the reasons argued by the learned counsel for the

respondent.”

8. Learned counsel for the petitioner would further submit that

since the legislature has used the word 'may', as such, it is

discretionary and learned trial court should have not granted

20% of cheque amount as interim compensation, therefore,

orders passed by both the courts below, are not just and

proper, which are liable to be quashed by this Court.

9. Before adverting to the submission made by learned counsel

for the petitioner, it is expedient to see that aims and object of

amended provision of Section 143A of the Act, 1881, which

reads as under:-

1 AIR Online 2019 Mad 801

Page 5 of 12

“The Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 (the Act)

was enacted to define and amend the law relating

to Promissory Notes, Bills of Exchange and

Cheques. The said Act has been amended from

time to time so as to provide, inter alia, speedy

disposal of cases relating to the offence of

dishonour of cheques. However, the Central

Government has been receiving several

representations from the public including trading

community relating to pendency of cheque

dishonour cases. This is because of delay tactics

of unscrupulous drawers of dishonoured cheques

due to easy filing of appeals and obtaining stay

on proceedings. As a result of this, injustice is

caused to the payee of a dishonoured cheque

who has to spend considerable time and

resources in court proceedings to realize the

value of the cheque. Such delays compromise the

sanctity of cheque transactions.

2. It is proposed to amend the said Act with a

view to address the issue of undue delay in final

resolution of cheque dishonour cases so as to

provide relief to payees of dishonoured cheques

and to discourage frivolous and unnecessary

litigation which would save time and money. The

proposed amendments will strengthen the

credibility of cheques and help trade and

commerce in general by allowing lending

institutions, including banks, to continue to extend

financing to the productive sectors of the

economy.”

10. From perusal of the Act, 1881 as well as amended Section

143A of the Act, 1881, it is clear that the Act, 1881 has played

a substantial role in the Indian commercial landscape and has

given rightful sanction against defaulters of the due process of

trade who engage in disingenuous activities that causes

unlawful losses to rightful recipients through cheque

dishonour. Thereafter, the legislature has amended Act, 1881,

which came into force on 01.09.2018 with the aim to secure

the interest of the complainant along with increasing the

efficacy and expediency of proceedings under Section 138 of

the Act, 1881. Section 143A of the Act, 1881 stipulates that

under certain stages of proceedings under Section 138 of the

Act, 1881, the Court may order for the drawer to make

Page 6 of 12

payment upto 20% of the cheque amount during the

pendency of the matter. The order under Section 143A of the

Act, 1881 can be passed only in summary trial or a summons

case, where he pleads not guilty to the accusation made in

the complaint, in any the case upon framing of charge.

11. From perusal of Section 143A of the Act, 1881, it is quite

evident that the act has been amended by granting interim

measures ensuring that interest of complainant is upheld in

the interim period before the charges are proven against the

drawer. The intent behind this provision is to provide aid to the

complainant during the pendency of proceedings under

Section 138 of the Act, where he is already suffering double-

edged sword of loss of receivables by dishonor of the cheque

and the subsequent legal costs in pursuing claim and offence.

These amendments would reduce pendency in courts

because of the deterrent effect on the masses along ensuring

certainty of process that was very much lacking in the past,

especially enforced at key stages of the proceedings under

the Act. The changes brought forth by way of the 2018

amendment to the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 are

substantial in nature and focus heavily on upholding the

interests of the complainants in such proceedings.

12. From perusal of the amended provision of Section 143A of the

Act, 1881, it is clear that the word 'may' used is beneficial for

the complainant because the complainant has already

suffered for mass deed committed by the accused by not

paying the amount, therefore, it is in the interest of the

complainant as well the accused if the 20% of the cheque

amount is to be paid by the accused, he may be able to utilize

the same for his own purpose, whereas the accused will be in

safer side as the amount is already deposited in pursuance of

the order passed under Section 143A of the Act, 1881. When

the final judgment passed against him, he has to pay

allowances on lower side. Section 143A of the Act, 1881 has

been drafted in such a manner that it secures the interest of

Page 7 of 12

the complainant as well as the accused, therefore, from

perusal of aims and object of amended Section 143A of the

Act, 1881, it is quite clear that the word 'may' may be treated

as 'shall' and it is not discretionary but of directory in nature.

13. The Hon'ble Supreme Court, while examining 'may' used

'shall' and have effect of directory in nature in case of

Bachahan Devi & another Vs. Nagar Nigam, Gorakhpur &

another2, which reads as under:-

“18. It is well-settled that the use of word “may”

in a statutory provision would not by itself show

that the provision is directory in nature. In some

cases, the legislature may use the word 'may' as

a matter of pure conventional courtesy and yet

intend a mandatory force. In order, therefore, to

interpret the legal import of the word “may”, the

court has to consider various factors, namely, the

object and the scheme of the Act, the context and

the background against which the words have

been used, the purpose and the advantages

sought to be achieved by the use of this word,

and the like. It is equally well-settled that where

the word 'may' involves a discretion coupled with

an obligation or where it confers a positive

benefit to a general class of subjects in a utility

Act, or where the court advances a remedy and

suppresses the mischief, or where giving the

words directory significance would defeat the

very object of the Act, the word 'may' should be

interpreted to convey a mandatory force. As a

general rule, the word “may” is permissive and

operative to confer discretion and especially so,

where it is used in juxtaposition to the word

“shall”, which ordinarily is imperative as it

imposes a duty. Cases however, are not wanting

where the words “may” “shall”, and “must” are

used interchangeably. In order to find out whether

these words are being used in a directory or in a

mandatory sense, the intent of the legislature

should be looked into along with the pertinent

circumstances.

19. “17. The distinction of mandatory

compliance or directory effect of the language

depends upon the language couched in the

statute under consideration and its object,

purpose and effect. The distinction reflected in

2 (2008) 12 SCC 372

Page 8 of 12

the use of the word `shall' or 'may' depends on

conferment of power. Depending upon the

context, 'may' does not always mean may. 'May'

is a must for enabling compliance of provision but

there are cases in which, for various reasons, as

soon as a person who is within the statute is

entrusted with the power, it becomes [his] duty to

exercise [that power]. Where the language of

statute creates a duty, the special remedy is

prescribed for non-performance of the duty.”

20. If it appears to be the settled intention of the

legislature to convey the sense of compulsion, as

where an obligation is created, the use of the

word “may” will not prevent the court from giving

it the effect of Compulsion or obligation. Where

the statute was passed purely in public interest

and that rights of private citizens have been

considerably modified and curtailed in the

interests of the general development of an area

or in the interests or removal of slums and

unsanitary areas. Though the power is conferred

upon the statutory body by the use of the word

“may” that power must be construed as a

statutory duty. Conversely, the use of the term

'shall' may indicate the use in optional or

permissive sense. Although in general sense

'may' is enabling or discretional and “shall is

obligatory, the connotation is not inelastic and

inviolate." Where to interpret the word “may” as

directory would render the very object of the Act

as nugatory, the word “may must mean 'shall'.

21. The ultimate rule in construing auxiliary verbs

like “may and “shall” is to discover the legislative

intent; and the use of words `may' and 'shall' is

not decisive of its discretion or mandates. The

use of the words “may” and `shall' may help the

courts in ascertaining the legislative intent

without giving to either a controlling or a

determinating effect. The courts have further to

consider the subject matter, the purpose of the

provisions, the object intended to be secured by

the statute which is of prime importance, as also

the actual words employed.”

14. The Supreme Court in Surinder Singh Deswal alias Colonel

S.S. Deswal & others Vs. Virender Gandhi 3, has examined

provision of Section 148 of the Act, 1881 and held that it is

mandatory provision. The relevant para of the judgment is

reproduced below:-

3 (2019) 11 SCC 341

Page 9 of 12

“8. Now so far as the submission on behalf of

the Appellants that even considering the

language used in Section 148 of the N.I. Act as

amended, the appellate Court "may" order the

Appellant to deposit such sum which shall be a

minimum of 20% of the fine or compensation

awarded by the trial Court and the word used is

not "shall" and therefore the discretion is vested

with the first appellate court to direct the

Appellant - Accused to deposit such sum and the

appellate court has construed it as mandatory,

which according to the learned Senior Advocate

for the Appellants would be contrary to the

provisions of Section 148 of the N.I. Act as

amended is concerned, considering the amended

Section 148 of the N.I. Act as a whole to be read

with the Statement of Objects and Reasons of

the amending Section 148 of the N.I. Act, though

it is true that in amended Section 148 of the N.I.

Act, the word used is "may", it is generally to be

construed as a "rule" or "shall" and not to direct

to deposit by the appellate court is an exception

for which special reasons are to be assigned.

Therefore amended Section 148 of the N.I. Act

confers power upon the Appellate Court to pass

an order pending appeal to direct the Appellant-

Accused to deposit the sum which shall not be

less than 20% of the fine or compensation either

on an application filed by the original complainant

or even on the application filed by the Appellant-

Accused Under Section 389 of the Code of

Criminal Procedure to suspend the sentence.

The aforesaid is required to be construed

considering the fact that as per the amended

Section 148 of the N.I. Act, a minimum of 20% of

the fine or compensation awarded by the trial

court is directed to be deposited and that such

amount is to be deposited within a period of 60

days from the date of the order, or within such

further period not exceeding 30 days as may be

directed by the appellate court for sufficient

cause shown by the Appellant. Therefore, if

amended Section 148 of the N.I. Act is

purposively interpreted in such a manner it would

serve the Objects and Reasons of not only

amendment in Section 148 of the N.I. Act, but

also Section 138 of the N.I. Act. Negotiable

Instruments Act has been amended from time to

time so as to provide, inter alia, speedy disposal

of cases relating to the offence of the

dishonoured of cheques. So as to see that due to

delay tactics by the unscrupulous drawers of the

Page 10 of 12

dishonoured cheques due to easy filing of the

appeals and obtaining stay in the proceedings,

an injustice was caused to the payee of a

dishonoured cheque who has to spend

considerable time and resources in the court

proceedings to realise the value of the cheque

and having observed that such delay has

compromised the sanctity of the cheque

transactions, the Parliament has thought it fit to

amend Section 148 of the N.I. Act. Therefore,

such a purposive interpretation would be in

furtherance of the Objects and Reasons of the

amendment in Section 148 of the N.I. Act and

also Section 138 of the N.I. Act.”

15. The Hon'ble Supreme Court in G.J. Raja Vs. Tejraj Surana4,

has examined the amended Section 143A of the Act, 1881

and held that it is prospective effect and not retrospective

effect. The relevant para of the judgment is reproduced

below:-

“19. It must be stated that prior to the insertion of

Section 143-A in the Act there was no provision

on the statute book whereunder even before the

pronouncement of the guilt of an accused, or

even before his conviction for the offence in

question, he could be made to pay or deposit

interim compensation. The imposition and

consequential recovery of fine or compensation

either through the modality of Section 421 of the

Code or Section 357 of the code could also arise

only after the person was found guilty of an

offence. That was the status of law which was

sought to be changed by the introduction of

Section 143A in the Act. It now imposes a liability

that even before the pronouncement of his guilt

or order of conviction, the accused may, with the

aid of State machinery for recovery of the money

as arrears of land revenue, be forced to pay

interim compensation. The person would,

therefore, be subjected to a new disability or

obligation. The situation is thus completely

different from the one which arose for

consideration in ESI Corpn. v. Dwarka Nath

Bhargwa, (1997) 7 SCC 131.

23. In the ultimate analysis, we hold Section

143A to be prospective in operation and that the

provisions of said Section 143A can be applied or

invoked only in cases where the offence under

4 (2019) 19 SCC 469

Page 11 of 12

Section 138 of the Act was committed after the

introduction of said Section 143A in the statute

book. Consequently, the orders passed by the

Trial Court as well as the High Court are required

to be set aside. The money deposited by the

Appellant, pursuant to the interim direction

passed by this Court, shall be returned to the

Appellant along with interest accrued thereon

within two weeks from the date of this order.”

16. Therefore, the word “may” be treated as “shall” and is not

discretionary, but of directory in nature, therefore, the learned

Judicial Magistrate First Class has rightly passed the interim

compensation in favour of the complainant.

17. In L.G.R. Enterprises (Supras), the Hon'ble Madras High

Court held as under:-

“8. Therefore, whenever the trial Court

exercises its jurisdiction under Section 143A(1) of

the Act, it shall record reasons as to why it directs

the accused person (drawer of the cheque) to pay

the interim compensation to the complainant. The

reasons may be varied. For instance, the accused

person would have absconded for a longtime and

thereby would have protracted the proceedings or

the accused person would have intentionally

evaded service for a long time and only after

repeated attempts, appears before the Court, or

the enforceable debt or liability in a case, is borne

out by overwhelming materials which the accused

person could not on the face of it deny or where

the accused person accepts the debt or liability

partly or where the accused person does not

cross examine the witnesses and keeps on

dragging with the proceedings by filing one

petition after another or the accused person

absonds and by virtue of a non-bailable warrant

he is secured and brought before the Court after a

long time or he files a recall non-bailable warrant

petition after a long time and the Court while

considering his petition for recalling the non-

bailable warrant can invoke Section 143A(1) of the

Act. This list is not exhaustive and it is more

illustrative as to the various circumstances under

which the trial Court will be justified in exercising

its jurisdiction under Section 143A(1) of the Act, by

directing the accused person to pay the interim

compensation of 20% to the complainant.

Page 12 of 12

9. The other reason why the order of the trial

Court under Section 143A(1) of the Act, should

contain reasons, is because it will always be

subjected to challenge before this Court. This

Court while considering the petition will only look

for the reasons given by the Court below while

passing the order under Section 143A(1) of the

Act. An order that is subjected to appeal or

revision, should always be supported by reasons.

A discretionary order without reasons is, on the

face of it, illegal and it will be setaside on that

ground alone.”

18. The judgment cited by learned counsel for the petitioner also

indicates that the Judicial Magistrate First Class has to pass a

reasoned order for determining quantum of compensation,

which is payable to the victim looking to the facts and

circumstances each case, but does not suggest any iota that

grant of compensation as per Section 143A of the Act, 1881 is

of discretionary in nature.

19. From perusal of provisions of the Act, 1881 considering the

aims behind object of the Act, 1881 and the law laid down by

the Supreme Court, I am of the considered view that the

amendment in Section 143A of the Act, 1881 is mandatory in

nature, therefore, the learned Judicial Magistrate First Class

has rightly passed the order of interim compensation in favour

of the respondent and has not committed any irregularity or

illegality in passing such order. The learned 11 th Additional

Sessions Judge has also not committed any irregularity or

illegality in rejecting the revision filed by the petitioner, which

warrants any interference by this Court.

20. In view of the above, this petition being devoid of merits, is

liable to be and is hereby dismissed. No order as to costs.

Sd/-

(Narendra Kumar Vyas)

Judge

Arun

You might also like

- Legal Fees Invoice FormatDocument1 pageLegal Fees Invoice FormatJITENDRA SHARMANo ratings yet

- Drafted Reply in Ajay KumarDocument27 pagesDrafted Reply in Ajay KumarMuskaan SinhaNo ratings yet

- Dishonour of Cheques in India: A Guide along with Model Drafts of Notices and ComplaintFrom EverandDishonour of Cheques in India: A Guide along with Model Drafts of Notices and ComplaintRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Asmeet Singh BhatiaDocument20 pagesAsmeet Singh BhatiaUtkarsh Khandelwal100% (1)

- Before The Hon'Ble Principal Senior Civil Judge at MorbiDocument7 pagesBefore The Hon'Ble Principal Senior Civil Judge at MorbiShaheenaNo ratings yet

- CT Cases 5332/2020 Yogender Panwar vs. Ram Kishore: NoonDocument6 pagesCT Cases 5332/2020 Yogender Panwar vs. Ram Kishore: Noonroopsi ratheeNo ratings yet

- Format of Plaint Claiming Compensation For DefamationDocument2 pagesFormat of Plaint Claiming Compensation For DefamationDHUP CHAND JAISWAL100% (6)

- Salary Attachment WarrantDocument2 pagesSalary Attachment WarrantJerard francis victor100% (2)

- Section 156 (3) Legal DraftDocument9 pagesSection 156 (3) Legal Draftronn13nNo ratings yet

- 15 Civil Revision Petition Anand SharmaDocument11 pages15 Civil Revision Petition Anand SharmamahabaleshNo ratings yet

- WRT Discharge ApplicationDocument5 pagesWRT Discharge ApplicationSurbhi Gupta0% (1)

- Bail Under Section 376Document29 pagesBail Under Section 376Amit BhatiNo ratings yet

- Impleadment Application O1 R 10 CPCDocument6 pagesImpleadment Application O1 R 10 CPCraj singh100% (1)

- Application For File InspectionDocument2 pagesApplication For File InspectionAnuj TomarNo ratings yet

- 190 CRPC Sample ApplicationsDocument40 pages190 CRPC Sample ApplicationsIsrar A. Shah JeelaniNo ratings yet

- National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission New Delhi Revision Petition No. 2922 of 2015Document5 pagesNational Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission New Delhi Revision Petition No. 2922 of 2015Moneylife FoundationNo ratings yet

- NBWDocument4 pagesNBWabctandon100% (1)

- Replication Nextra 04.01.2020Document13 pagesReplication Nextra 04.01.2020sagar100% (1)

- 151 PetitionDocument3 pages151 PetitionSayan Mitra100% (1)

- Appeal Against Conviction - STC - Depash Bharathi VS Sruthi NirmalDocument14 pagesAppeal Against Conviction - STC - Depash Bharathi VS Sruthi Nirmalshahith100% (2)

- Legal Notice - Osho PackagingDocument4 pagesLegal Notice - Osho PackagingUtkarsh KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Tayabba Vs Suhail Application Name DeletionDocument6 pagesTayabba Vs Suhail Application Name DeletionRiya NitharwalNo ratings yet

- Before The National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission, at New Delhi Complaint Case No. of 2017Document11 pagesBefore The National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission, at New Delhi Complaint Case No. of 2017sandysinghsihag100% (1)

- Written Statement SashiDocument14 pagesWritten Statement SashishivendugaurNo ratings yet

- Meta Data Form For Digital Courts NI ActDocument2 pagesMeta Data Form For Digital Courts NI ActonevikasNo ratings yet

- Execution PetitionDocument6 pagesExecution PetitionBhanu Pratap100% (1)

- An Application For Substitution of The Respondent NoDocument4 pagesAn Application For Substitution of The Respondent NoMoid Ali100% (1)

- Appl. For Waiver CostDocument3 pagesAppl. For Waiver CostKartikeya MudgilNo ratings yet

- Application Format For Certified Copy - 0Document2 pagesApplication Format For Certified Copy - 0vikramNo ratings yet

- Summons For JudgmentDocument11 pagesSummons For JudgmentAshutosh Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- Application Under Order 39, Rule 7 of The C. P. C.Document2 pagesApplication Under Order 39, Rule 7 of The C. P. C.namanNo ratings yet

- Memorandum of Crl. Misc. Petition Under Section - 439 of The Code of Ciminal Procedure, 1973.Document6 pagesMemorandum of Crl. Misc. Petition Under Section - 439 of The Code of Ciminal Procedure, 1973.Alliance Law AssociatesNo ratings yet

- Application For Ex ParteDocument1 pageApplication For Ex Parterahul BAROTNo ratings yet

- Commercial Mediation FormDocument3 pagesCommercial Mediation Formrahul BAROTNo ratings yet

- Case Information Format FINALDocument2 pagesCase Information Format FINALvishalsehijpalNo ratings yet

- In The High Court of Madhya Pradesh: IndexDocument8 pagesIn The High Court of Madhya Pradesh: IndexAayush100% (1)

- Template - Transfer Petition Before The Supreme Court of IndiaDocument5 pagesTemplate - Transfer Petition Before The Supreme Court of IndiaAyushNo ratings yet

- In The Court of The Fast Track Judicial Magistrate No.I of CoimbatoreDocument3 pagesIn The Court of The Fast Track Judicial Magistrate No.I of CoimbatoreBoopathy RangasamyNo ratings yet

- Additional Affidavit in Lieu of Examination in Chief of Pw2Document6 pagesAdditional Affidavit in Lieu of Examination in Chief of Pw2KamshadNo ratings yet

- Application Under Order 9, Rule 9, C. P. C.Document5 pagesApplication Under Order 9, Rule 9, C. P. C.Intern VSPNo ratings yet

- Shoib Interim BailDocument7 pagesShoib Interim BailTSA LEGALNo ratings yet

- Affidavit in A Civil Revision Petition Under Section 115 of CPC and For Stay Against OrderDocument3 pagesAffidavit in A Civil Revision Petition Under Section 115 of CPC and For Stay Against OrderVeena100% (1)

- 482-2022 - Sandeep Kumar Rai - 26.06.2022Document28 pages482-2022 - Sandeep Kumar Rai - 26.06.2022Sandeep RaiNo ratings yet

- Affidavit - EmergentDocument2 pagesAffidavit - EmergentMuthu KumaranNo ratings yet

- Application To Sue As Indegent PersonDocument2 pagesApplication To Sue As Indegent Personaditi todariaNo ratings yet

- TahsinDocument11 pagesTahsinPritam Ananta100% (1)

- Senior Citizen Application Before TribunalDocument5 pagesSenior Citizen Application Before TribunalUrvashi Dhonde100% (1)

- Consumer ComplaintDocument13 pagesConsumer ComplaintAlok kumar TripathiNo ratings yet

- In The Court of Gurgaon, Haryana Omp (Comm.) NoDocument9 pagesIn The Court of Gurgaon, Haryana Omp (Comm.) NoRadhika SharmaNo ratings yet

- Execution Petition in Ms Word Format DownloadDocument3 pagesExecution Petition in Ms Word Format DownloadHsk100% (1)

- Judgments in Ni Act & DCDocument31 pagesJudgments in Ni Act & DCVarri Demudu Babu100% (1)

- Suresh BansalDocument12 pagesSuresh BansalTauheedAlamNo ratings yet

- 138 ChecklistDocument3 pages138 ChecklistSachin DhamijaNo ratings yet

- Bail ApplicationDocument9 pagesBail ApplicationAlisha khanNo ratings yet

- Application For ExemptionDocument1 pageApplication For ExemptionNick RoxxNo ratings yet

- Appellate Court Cannot Grant BailDocument12 pagesAppellate Court Cannot Grant BailLive Law0% (1)

- Pooja Versus State (Rejoinder Affidavit)Document16 pagesPooja Versus State (Rejoinder Affidavit)Harsh NawariaNo ratings yet

- Written Statement - Sarin AdvocateDocument12 pagesWritten Statement - Sarin AdvocateSandeepPamaratiNo ratings yet

- Form 7 - RERADocument1 pageForm 7 - RERAChhaya Sagar SoniNo ratings yet

- Appeal Aganist An Award Moter Vehicle Claim Mfa 2019 MVC 559 of 2016 Lakshmikanth Adv.Document17 pagesAppeal Aganist An Award Moter Vehicle Claim Mfa 2019 MVC 559 of 2016 Lakshmikanth Adv.Anil kumarNo ratings yet

- Rey LacaDocument658 pagesRey LacaRey LacadenNo ratings yet

- 177 - Loyola Grand Villas Homeowners v. CADocument3 pages177 - Loyola Grand Villas Homeowners v. CAMariaHannahKristenRamirez0% (1)

- JKSSB Panchayat Secretary Adfar NabiDocument3 pagesJKSSB Panchayat Secretary Adfar NabiSHEIKHXUNINo ratings yet

- DTR (Vacant)Document2 pagesDTR (Vacant)Eugene PelonioNo ratings yet

- Eu 965 - 2012Document4 pagesEu 965 - 2012riversgardenNo ratings yet

- Malaysia - Employment (Amendment of First Schedule) Order 2022. - Conventus LawDocument3 pagesMalaysia - Employment (Amendment of First Schedule) Order 2022. - Conventus LawfahiraNo ratings yet

- Layouts Permssions Payment InformationDocument2 pagesLayouts Permssions Payment InformationSrikanthNo ratings yet

- 2818 2021 33 1501 27661 Judgement 20-Apr-2021Document106 pages2818 2021 33 1501 27661 Judgement 20-Apr-2021Richa KesarwaniNo ratings yet

- Letter of Intent in Construction (How To Write) - Quantity Surveyor BlogDocument5 pagesLetter of Intent in Construction (How To Write) - Quantity Surveyor BlogShashank BahiratNo ratings yet

- Indian Partnership Act, 1932Document24 pagesIndian Partnership Act, 1932Malkeet SinghNo ratings yet

- RERA CertificateDocument1 pageRERA Certificatecs.saisampathNo ratings yet

- Uniform Customs and Practice For Documentary Credit ICC Publication No. 600 (Some Articles)Document10 pagesUniform Customs and Practice For Documentary Credit ICC Publication No. 600 (Some Articles)Мария НиколенкоNo ratings yet

- The Indian Partnership Act 1932Document4 pagesThe Indian Partnership Act 1932Shweta BhadauriaNo ratings yet

- Forms of Tourism and Hospitality Business Ownership and FranchisingDocument27 pagesForms of Tourism and Hospitality Business Ownership and FranchisingJulie Mae Guanga Lpt100% (1)

- Legal Notice... Ahsan Ali ShahDocument3 pagesLegal Notice... Ahsan Ali Shahfahadkhan.00769hdNo ratings yet

- n1297 Saravanan Raja Retainer AgreementDocument4 pagesn1297 Saravanan Raja Retainer AgreementRohitha SNo ratings yet

- MWD User Checklist: Collaborative Working (Schedule 3, Supplemental Provision 1)Document3 pagesMWD User Checklist: Collaborative Working (Schedule 3, Supplemental Provision 1)KarthiktrichyNo ratings yet

- Power Saved 2R Alq5 30.11.22Document1 pagePower Saved 2R Alq5 30.11.22aliNo ratings yet

- Barhabise Municipality 6x27-MinDocument1 pageBarhabise Municipality 6x27-MinHari PyakurelNo ratings yet

- National Law Institute University Bhopal: Property Law-I Trimester-Vi Case Analysis Rosher v. Rosher (1884) 26 CH.D 801Document14 pagesNational Law Institute University Bhopal: Property Law-I Trimester-Vi Case Analysis Rosher v. Rosher (1884) 26 CH.D 801PRATEEK AUSTINNo ratings yet

- Madan Lal v. State of Jammu and KashmirDocument14 pagesMadan Lal v. State of Jammu and KashmirRitesh RajNo ratings yet

- ConstitutionDocument19 pagesConstitutionNikita DakhoreNo ratings yet

- FIN Guidelines - On - The - Establishment - of - Labuan - Trust - and - Islamic - TrustDocument8 pagesFIN Guidelines - On - The - Establishment - of - Labuan - Trust - and - Islamic - TrustAl KayprofNo ratings yet

- TRANSPO - NotesDocument46 pagesTRANSPO - NotesElsha DamoloNo ratings yet

- Trade Union Act 1926Document2 pagesTrade Union Act 1926Ashley D’cruzNo ratings yet

- Age Grid & Rule Changes: Highlights For 2022-23Document11 pagesAge Grid & Rule Changes: Highlights For 2022-23shaun shepherdNo ratings yet

- EULADocument2 pagesEULAMary Valentina Gamba CasallasNo ratings yet

- What Is Memorandum of Understanding (Mou) ?: Indian Contract Act 1872Document5 pagesWhat Is Memorandum of Understanding (Mou) ?: Indian Contract Act 1872Redfields KavaliNo ratings yet

- Memorandum of AssociationDocument11 pagesMemorandum of Associationyashu43No ratings yet

- 15 TUCP vs. NHADocument7 pages15 TUCP vs. NHAchristopher d. balubayanNo ratings yet