Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sports and Recreation For Persons With Limb Deficiency: Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation April 2001

Sports and Recreation For Persons With Limb Deficiency: Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation April 2001

Uploaded by

MonishaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Global Citizens AssignmentDocument9 pagesGlobal Citizens Assignmentapi-658645362No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Body Image Change in Amputee ChildrenDocument6 pagesBody Image Change in Amputee ChildrenMonishaNo ratings yet

- Astheticc of Prosthetic DeviceDocument21 pagesAstheticc of Prosthetic DeviceMonishaNo ratings yet

- A Demographic Study of Lower Limb Amputees in A NoDocument4 pagesA Demographic Study of Lower Limb Amputees in A NoMonishaNo ratings yet

- Sports Apdapation Lower Limb and Upper Limb ProsthesisDocument8 pagesSports Apdapation Lower Limb and Upper Limb ProsthesisMonishaNo ratings yet

- Amputee Report 1986Document17 pagesAmputee Report 1986MonishaNo ratings yet

- Pedro Carreño: SkillsDocument1 pagePedro Carreño: Skillsapi-253966222No ratings yet

- Historical Phases of CSRDocument12 pagesHistorical Phases of CSRHIMANSHU RAWATNo ratings yet

- NCP EamcDocument4 pagesNCP EamcsustiguerchristianpaulNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was: Running Head: Epidemiology Reaction Paper 1Document3 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Running Head: Epidemiology Reaction Paper 1Jayson AbadNo ratings yet

- Dental BooklistDocument14 pagesDental Booklistالمكتبة المليونيةNo ratings yet

- Diarrhoea CattleDocument11 pagesDiarrhoea CattleOnutza Elena Tătaru100% (1)

- Mavalli Tiffin Room (MTR) : A Brand HistoryDocument12 pagesMavalli Tiffin Room (MTR) : A Brand HistoryRohit GunwaniNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibiographyDocument7 pagesAnnotated Bibiographyapi-439568635No ratings yet

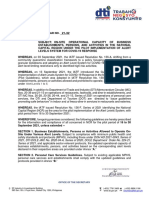

- Memorandum - Circular - No - 21-32 (DTI Operational Capacity Under Alert Level System)Document11 pagesMemorandum - Circular - No - 21-32 (DTI Operational Capacity Under Alert Level System)Brian TomasNo ratings yet

- Tetanus ProphylaxisDocument4 pagesTetanus ProphylaxisRifda LatifaNo ratings yet

- Physical Inactivity TestDocument66 pagesPhysical Inactivity TestNHEMSTERS xoxoNo ratings yet

- Hci Report Group3Document15 pagesHci Report Group3api-302906387No ratings yet

- Notification NIMH Various PostsDocument4 pagesNotification NIMH Various PostsKeshav RamNo ratings yet

- Book - Health and WellnessDocument10 pagesBook - Health and WellnessWill AsinNo ratings yet

- KKKDocument94 pagesKKKahmedhaji_sadikNo ratings yet

- Mahakal Institute of Pharamaceutical Studies, UjjainDocument8 pagesMahakal Institute of Pharamaceutical Studies, UjjainsafiyaNo ratings yet

- Paul Saville For Mayor of Bristol 2016Document5 pagesPaul Saville For Mayor of Bristol 2016Paul SavilleNo ratings yet

- LI Report Example1Document131 pagesLI Report Example1Spekza GamingNo ratings yet

- Module Overview: Session Date Tutor Lecture TopicDocument7 pagesModule Overview: Session Date Tutor Lecture TopicFiveer FreelancerNo ratings yet

- School Forms (Sf2) June-March 2015Document109 pagesSchool Forms (Sf2) June-March 2015Kristoffer Alcantara RiveraNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 1 Identifying Stress and RubricDocument2 pagesLesson Plan 1 Identifying Stress and Rubricapi-252461940No ratings yet

- MAPEH 7 Q4 Week 4Document9 pagesMAPEH 7 Q4 Week 4Maricris ArsibalNo ratings yet

- Fehling's Test: Comparative Test Reactions of CarbohydratesDocument33 pagesFehling's Test: Comparative Test Reactions of CarbohydratesTom Anthony Tonguia100% (1)

- Yildiz Technical University European Union Office Sample Test of English For Erasmus StudentsDocument2 pagesYildiz Technical University European Union Office Sample Test of English For Erasmus StudentsSerdar GurbanovNo ratings yet

- Electro-Chemiluminescence Immunoassay (ECLIA) For The Quantitative Determination of CEA in Human Serum and PlasmaDocument2 pagesElectro-Chemiluminescence Immunoassay (ECLIA) For The Quantitative Determination of CEA in Human Serum and Plasmamaricela carmen te desea lo mejorNo ratings yet

- Plan A 2025 CommitmentsDocument20 pagesPlan A 2025 CommitmentsReswinNo ratings yet

- CDC 118387 DS1Document132 pagesCDC 118387 DS1Sina AyodejiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10Document17 pagesChapter 10Bryle Dela TorreNo ratings yet

- GASTROINTESTINALDocument8 pagesGASTROINTESTINALrheantiffany0815No ratings yet

Sports and Recreation For Persons With Limb Deficiency: Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation April 2001

Sports and Recreation For Persons With Limb Deficiency: Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation April 2001

Uploaded by

MonishaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sports and Recreation For Persons With Limb Deficiency: Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation April 2001

Sports and Recreation For Persons With Limb Deficiency: Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation April 2001

Uploaded by

MonishaCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/12093348

Sports and recreation for persons with limb deficiency

Article in Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation · April 2001

DOI: 10.1053/apmr.2001.22243 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

37 2,808

4 authors, including:

Charles E Levy

North Florida and South Georgia Veterans Health System

99 PUBLICATIONS 1,959 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Battlefield Acupuncture View project

brain injury View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Charles E Levy on 27 November 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

S38

FOCUSED REVIEW

Sports and Recreation for Persons With Limb Deficiency

Joseph B. Webster, MD, Charles E. Levy, MD, Phillip R. Bryant, DO, Paul E. Prusakowski, CPO

ABSTRACT. Webster JB, Levy CE, Bryant PR, Prusa- nentry, and fabrication have also been an essential part of this

kowski PE. Sports and recreation for persons with limb defi- development. Many of these improvements have been driven

ciency. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001;82 Suppl 1:S38-44. by persons with limb loss who have challenged the system and

demanded prosthetic componentry capable of facilitating,

Opportunities for persons with limb deficiency to participate rather than limiting, their athletic, artistic, and leisure ambi-

in sport and recreational activities have increased dramatically tions. The objective of this article is to review the development

over the past 20 years. Various factors have contributed to this and importance of sports and recreation for persons with limb

phenomenon, including an increased public interest in sports deficiency as well as the specific prosthetic considerations for

and fitness as well as improvements in disability awareness. An this group.

even more essential element has been a consumer-driven de-

mand for advances in prosthetic technology and design.

Whether the activity is a music performance, a friendly round HISTORY AND IMPORTANCE

of golf, or a high-level track-and-field competition, the benefits The social need for leisure has been identified as an impor-

of participation in sports and recreation are numerous both at tant component of the quality of life of persons, especially if a

the individual and at the societal level. This article provides an person’s full involvement in society is limited by a physical

overview of the development and scope of sport and recre- impairment.1-3,7 Several studies have noted that participation in

ational opportunities available to persons with limb deficiency. sports and recreation is a major concern for persons with limb

In addition, specific prosthetic considerations for several com- deficiency and that these activities are important for their

mon sport and recreational activities are presented in a case- reintegration into the community.8-11 In addition to the physi-

discussion format. ologic benefits—improved strength, cardiopulmonary endur-

Overall Article Objective: To review the development and ance, muscle coordination, and balance—involvement in ther-

scope of sport and recreational opportunities available to per- apeutic recreation and physical fitness can also enhance coping

sons with limb deficiency. behavior, cognitive abilities, mood, psychologic well-being,

Key Words: Prostheses and implants; Artificial limbs; Lei- self-confidence, and self-esteem.1,12-15 Particularly for a child

sure activities; Sports; Rehabilitation with limb deficiency, involvement in sport and recreational

© 2001 by the American Academy of Physical Medicine and activities provides an important mechanism for development of

Rehabilitation motor coordination, integration with peer groups, and adjust-

ment to physical limitations.1,16-18

The origin of organized sports for persons with disabilities

ARTICIPATION IN SPORTS and recreation has many

P physical, psychologic, and emotional benefits for the per-

son with limb deficiency. These factors make integration into

1-4

has been largely attributed to Sir Ludwig Guttmann, who

implemented athletics and sports as a part of comprehensive

rehabilitation at the Stoke Mandeville Hospital in England in

leisure, recreation, and sports activities a vital part of the 1944.4,6 Since then, there has been steady growth in the rec-

rehabilitation process. Opportunities for persons with limb ognition and organization of both recreational and competitive

deficiency to participate in leisure and competitive sports have sports for persons with disabilities. Organized athletic compe-

improved immensely over the past 20 years. This improvement titions and recreational sport opportunities for persons with

has been realized in part through an increased public interest in limb deficiency are currently widely available across the

physical fitness, leisure, and sports, and also through greater globe.5,6,19,20 Many organizations are available to assist the

awareness that persons with limb deficiency and other disabil- person with limb deficiency who desires to become more active

ities can compete at very high levels of athletic competition.4-6 in recreational and sport activities.4,19-22 While the majority of

Accompanying this has been the growth and development of these organizations are impairment or disability specific, others

innumerable sports organizations for the disabled which pro- are more sports specific. One such organization, Disabled

vide information, resources, and support for almost all sports Sports USA, provides opportunities for recreational rehabilita-

and leisure activities. Advances in prosthetic design, compo- tion and competitive sports programs, along with training

camps to prepare amputee athletes for the summer and winter

paralympic games.

From the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Brody School of The International Paralympic Games were founded in

Medicine, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC (Webster, Bryant); Physical 1960.4,6 As the number of participants has steadily grown, the

Medicine and Rehabilitation Service and Brain Rehabilitation Research Center, North

Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Department of Orthopaedics and Re-

level and scope of competition have sharpened and public

habilitation, College of Medicine, University of Florida, Health System and Univer- interest has increased. Although competitions initially focused

sity of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, FL (Levy); and Orthotics and on wheelchair athletes, since 1976 the Paralympics have in-

Prosthetics Clinical Technologies, Inc., Gainesville, FL (Prusakowski). cluded ambulatory persons with limb deficiencies.6 The 1996

Accepted November 1, 2000.

No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research

International Paralympic Games in Atlanta, GA, hosted a

supporting this article has or will confer a benefit upon the author(s) or upon any record 3500 athletes from 120 nations, who participated in 17

organization with which the author(s) is/are associated. full medal and 2 demonstration sports. Athletes with limb

Address correspondence to Joseph B. Webster, MD, Dept of Physical Medicine and deficiencies were involved with the majority of these sports.6

Rehabilitation East Carolina University, Brody School of Medicine, 600 Moye Blvd,

Greenville, NC 27858.

The growth of events such as the Paralympics has been valu-

0003-9993/01/8203-6659$35.00/0 able for increasing public awareness of the capabilities of both

doi:10.1053/apmr.2001.22243 amputee athletes and the disabled population in general.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 82, Suppl 1, March 2001

SPORTS AND RECREATION FOR PERSONS WITH LIMB DEFICIENCY, Webster S39

EVALUATION PROCESS allow use of prosthetic devices, and the swimming classifica-

The evaluation of a person with limb deficiency who desires tion divides athletes with different disabling conditions into 10

to participate in recreational and sports activities is in many functional classes based on impairment level. Paralympic

respects similar to that for any amputee patient.23-25 In addition sports such as tennis and basketball, which are played in

to the more standard aspects of evaluation, the exact demands wheelchairs, are also open to persons with limb deficiency and

of the desired activity and the environment in which the sport have separate classification schemes. Despite these structured

is to be played need to be considered. For example, the pros- systems, each limb deficiency is different, and this difference

thetic requirements for fishing from a pier or dock may vary may impart a slight biomechanical or prosthetic advantage for

greatly from the requirements for surf fishing or fishing from a 1 person compared with the next.

boat. If the demands of the activity cannot be adequately

assessed or simulated in the clinic, an on-site evaluation or a PROSTHETIC CONSIDERATIONS

videotape review may provide additional insight. The fre-

quency and intensity of participation in the activity also need to General

be assessed. There are several special prosthetic considerations for the

During the physical examination, the physician and the pros- individual interested in using a prosthesis during recreational or

thetist must attempt to objectively and realistically assess sports activities.1,20,22 One of the first is whether the prosthesis

whether the individual and his/her residual limb(s) can tolerate will be used for both a specific recreational purpose and daily

the added stress and demands of the desired recreational activ- activities or exclusively for a particular activity (eg, sprint

ity. This includes a complete musculoskeletal evaluation and a running). The demands and frequency of the sports activity

cardiopulmonary assessment. A gradually progressive exercise play a role in this decision-making process, as do financial

and training program may have to be prescribed to prevent issues. In general, durability and strength of the prosthesis and

complications such as musculoskeletal injuries, residual limb its ability to withstand increased biomechanical forces are

skin breakdown, cardiopulmonary complications, and/or frus- important, especially during running or jumping activities.

tration with associated loss of self-esteem.26,27 Cardiac stress Failure of the prosthesis during either recreational use or com-

testing may be indicated, depending on the desired activity and petition can result not only in psychologic repercussions but in

the status of the patient.26,27 Another component of the evalu- physical injury as well.

ation and the prosthetic prescription is clear communication The significant biomechanical forces and repetitive nature of

among all team members, including the therapist and/or the recreational and sport activities also have a bearing on pros-

coach or trainer, if possible, so that the goals, expectations, and thetic suspension and the prosthetic interface with the residual

options for prosthetic fitting are clear. For persons wanting to limb. Auxiliary suspension systems provide added stability and

participate in competitive sports, a detailed evaluation of the security to the prosthetic suspension, especially with kicking

limb deficiency and other musculoskeletal impairments is also activities in the lower limb or throwing and catching activities

necessary, as this typically serves as the basis for competition in the upper limb. The use of interface materials such as

classification.6 silicone liners, gel liners, or hypobaric socks provides added

padding and helps to absorb and disperse potentially damaging

IMPAIRMENT CLASSIFICATION FOR SPORTS pressure and shear forces. Maintaining appropriate prosthetic

The impact of limb deficiency on athletic performance varies fit is particularly important in a child with limb deficiency, who

greatly, depending on the anatomic location, extent, and cause will need frequent socket revisions with growth changes.

of the limb deficiency. Classification systems for competitive For prosthetic devices that are to be used for recreation and

sports ensure that persons compete on as equal terms as pos- sports activities, cosmesis is typically less of a priority than

sible.21 Classification must also take into account whether or function, unless the prosthesis is to be used for everyday

not the use of prostheses, wheelchairs, or other adaptive equip- activities as well. Weight of the prosthesis is also important.

ment is allowed during competition. For most sports involving Although some research28 has noted that metabolic costs dur-

persons with limb deficiency, the classification depends pri- ing walking are unchanged with the addition of up to 1.34kg to

marily on the location and extent of the amputation(s).6,21 For a transfemoral prosthesis, little is known about the metabolic

competitions involving track and field events, all classes in- effects of prosthetic weight on higher level activities such as

clude a letter T (for track) or F (for field), followed by a number running. Despite the lack of supporting scientific evidence,

that designates the severity of the amputation (table 1). Com- most prosthetists strive to keep the prosthesis as light as pos-

petitive swimming events for persons with amputations do not sible while simultaneously providing a structure that is both

Table 1: Track and Field Classification System for Persons With a Limb Deficiency

T42 Single above-the-knee; combined lower and upper limb amputations; minimum disability

T43 Double below-the-knee; combined lower and upper limb amputations; normal function in throwing arm

T44 Single below-the-knee; combined lower and upper limb amputations; moderate reduced function in 1 or both limbs

T45 Double above-the-elbow; double below-the-elbow

T46 Single above-the-elbow; single below-the-elbow; upper limb function in throwing arm

F40 Double above-the-knee; combined lower and upper limb amputations; severe problems when walking.

F41 Standing athletes with no more than 70 points in the lower limbs (based on function and strength of muscle groups)

F42 Single above-the-knee; combined lower and upper limb amputation; normal function in throwing arm

F43 Double below-the-knee; combined lower and upper limb amputations; normal function in throwing arm

F44 Single below-the-knee; combined lower and upper limb amputations; normal function in throwing arm

F45 Double above-the-elbow; double below-the-elbow

F46 Single above-the-elbow; single below-the-elbow; upper limb function in throwing arm

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 82, Suppl 1, March 2001

S40 SPORTS AND RECREATION FOR PERSONS WITH LIMB DEFICIENCY, Webster

durable and able to function in the sports activity required. Advances in prosthetic pylon, ankle, and foot componentry,

Typically, persons using a prosthesis for sports require exten- especially the advent and development of high-profile dynamic

sive education regarding the maintenance, care, and adjustment elastic-response feet, have been a great benefit to both trans-

of the device. They need to be able to perform required pros- femoral and transtibial amputee runners. Although low-profile

thetic adjustments either before or during their athletic or dynamic elastic-response-type feet and multiaxial-type feet

recreational activity. They must also be able to inspect the designs can be used for occasional running,37-39 the advantages

prosthesis regularly and identify signs of impending compo- and benefits of high-profile dynamic elastic-response feet that

nent failure. incorporate the shank, ankle, and foot mechanism into a single

unit have been noted in several studies.40-46 This research,

combined with clinical experience, has made high-profile dy-

Sport-Specific Considerations namic elastic-response components such as the Flex-Foota and

Running Activities: case. Formulate a prosthetic prescrip- the Springliteb and their variations the preferred choice for

tion for a 25-year-old man with a traumatic left transfemoral many amputee runners, especially those involved in competi-

amputation due to a motorcycle accident 1 year ago who wants tive sports (fig 1). The Sprint-Flexa and Springlite Sprinterb are

to begin running for exercise and to resume playing basketball. components designed exclusively for competitive sprint run-

He is currently an active prosthetic user and ambulates without ning (fig 2). Through plantarflexion alignment and increased

assistive devices. keel stiffness, they allow a toe-running pattern. Although these

Discussion. Running is a part of many sports and recre- design features have advantages for sprint running, they are not

ational activities (eg, track, basketball, baseball, tennis). For suitable for everyday activities.

persons with limb deficiency, running can also be a method of Pylon-ankle-foot systems such as the Re-Flex-VSP®,a

exercise to help maintain or improve general fitness, weight Pathfinder™,c and Free-Flow,c which incorporate a dynamic

control, cardiopulmonary endurance, and psychologic well- elastic-response-type foot and a shock-absorbing pylon, are

being.1-3 For children with limb loss, running can be an integral well suited for the highly active person for training and also for

part of play and peer interaction. Even for the less active long-distance running47 (fig 3). The shock-absorbing pylon

amputee, the ability to run could be useful in an emergency.29 reduces forces on the residual limb with repetitive activities

As with many other activities, lower extremity amputee run-

ning has been revolutionized over the past 20 years by ad-

vances in prosthetic componentry. The use of materials such as

carbon fiber, titanium, and graphite has provided added

strength and energy-storage capabilities to prostheses while

decreasing the weight of prosthetic components. Significant

changes in prosthetic design have also occurred. Despite this,

the loss of normal biologic function and proprioceptive feed-

back of the distal extremity in persons with limb deficiency

leads to altered running biomechanics, including changes in

muscle work output and joint kinetics.30-33

With regard to prosthetic considerations for persons with

transfemoral amputations who desire to run, most will utilize a

narrow mediolateral socket design. They may also benefit from

the use of a flexible inner liner to decrease the weight of the

prosthesis and to accommodate the changing shape of the thigh

during muscular contraction and relaxation. Acrylic socket

laminations provide both the desired strength and low weight.

Because of its secure nature, suction is a commonly used

method of suspension in the transfemoral amputee patient,

although roll-on silicone or gel liners with pin-locking mech-

anisms are also viable options.34 The socket fit, suspension, and

interface are very important to the amputee runner because of

the much greater force and frequency of loading on the residual

limb. Swing- and stance-control hydraulic knee units, which

allow variable cadence, are preferred for most amputee run-

ners, especially now that units have become smaller and

lighter. Although recent studies and anecdotal reports have

found significant benefits with microprocessor-controlled knee

units for walking activities,35,36 they are not currently being

used for competitive running because of technical limitations.

For the transtibial runner, the posterior and lateral socket

trim lines are lowered to maximize range of motion at the knee.

Although these changes allow greater range of motion at the

knee, the compromise is a less secure suspension system.

Silicone sleeves, neoprene sleeves, or a waistbelt and fork-strap

are typical options for auxiliary transtibial suspension.34 Sili-

cone or gel liners are helpful in reducing shear forces and

preventing skin breakdown. Endoskeletal shank systems, Fig 1. Springlite Gold Medal.b A high-profile dynamic elastic-re-

which will be described below, provide the required strength sponse-type of pylon-ankle-foot system with removable heel plugs

and desired weight for a running prosthesis. for adjusting heel resistance to match activity level.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 82, Suppl 1, March 2001

SPORTS AND RECREATION FOR PERSONS WITH LIMB DEFICIENCY, Webster S41

months after a left transtibial amputation with new skin break-

down on the residual limb after beginning a recreational bicy-

cling program.

Discussion. Cycling is regarded by many as an excellent

form of exercise and recreation for persons with limb defi-

ciency. Cycling has also become a major competitive sport for

amputee athletes.6 The choice whether to use a prosthesis

during cycling activities depends primarily on the level of the

amputation. Persons with unilateral deficiencies above the

midtransfemoral level typically do not have enough strength in

their residual limb to push a pedal and thus do not benefit from

using a prosthesis during cycling. For these persons, a toe clip

on the intact side allows power to be applied to the pedal during

both the downward and the upward strokes.48-51 Persons with

unilateral amputations below the midtransfemoral level usually

prefer to use their prosthesis for cycling. The prosthesis pro-

vides better balance and symmetry during riding. For the

person interested in recreational cycling, as in the case de-

scribed, relatively few prosthetic accommodations are required.

Trim lines on the transtibial prosthetic socket may need to be

adjusted to prevent skin breakdown because of the need for

additional knee flexion with cycling, as compared with walk-

ing.50,51 For the transfemoral amputee, a knee unit that allows

adequate range of motion with variable resistance is helpful.

Ankle and foot components that allow some degree of ankle

motion are also desirable. Seating difficulties and proximal

Fig 2. Sprint-Flex.a A high-profile dynamic elastic-response foot

used for competitive sprint running.

such as distance running. These systems are also excellent

choices for sports requiring frequent jumping such as basket-

ball and high jumping. In the case described above, the indi-

vidual patients would likely benefit from this type of compo-

nentry in combination with a narrow mediolateral socket, a

suction or silicone suspension system, and a hydraulic knee

unit.

Historically, component failure, skin breakdown, and resid-

ual limb trauma, as well as the need for modified training

regimens, have been major concerns for amputee runners.

Technologic and design advances have made componentry

failure much less of a problem. Adequate suspension systems

remain a problem for some transtibial amputee runners because

systems that provide the most secure suspension have the

disadvantage of restricting range of motion at the knee. With

the use of gel liners and silicone interfaces, residual limb skin

problems have also been minimized. Although amputee ath-

letes must appreciate that new socket and interface systems

often require a break-in period during which training regimens

need to be modified, many competitive amputee runners are

now capable of training along with nonamputee runners.

Cycling: case. Provide prosthetic recommendations to a Fig 3. Re-Flex-VSP.a A dynamic elastic-response-type foot and an-

62-year-old man with peripheral arterial disease who returns 6 kle componentry with a shock-absorbing pylon.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 82, Suppl 1, March 2001

S42 SPORTS AND RECREATION FOR PERSONS WITH LIMB DEFICIENCY, Webster

skin irritation are common problems for transfemoral amputee cases, depending on the level of the extremity involvement and

cyclists. A narrow-design seat allows more room for the prox- the particular interests of the patient, a highly specialized

imal brim of the prosthesis, and proximal socket adjustments prosthetic prescription may be required.55,56 The important

can also be helpful.48 One of the most frequent problems characteristics of the upper limb recreational prosthesis are

encountered with using a prosthesis for cycling is trouble secure suspension, durability, and optimal weight. Just as with

keeping the prosthetic foot on the pedal. Using pedals with the lower limb amputee, a secure suspension system is impor-

serrated edges or toe clips can help prevent foot slippage, but tant for the upper limb amputee, especially for throwing,

it may also increase the risk of injury during a fall or when swinging, or catching. Auxiliary suspension systems such as a

stopping.48-50 For optimal power while pedaling on the pros- chest strap or a shoulder harness may be useful for the trans-

thetic side, the mid-foot of the prosthesis should be placed humeral amputee to maintain adequate contact with the resid-

directly over the pedal.48-51 For persons who do a large amount ual limb and to provide added support for the prosthesis. A

of riding, the prosthetic alignment may need to be adjusted to supracondylar suspension system or a silicone sleeve is a

a more straight-ahead position as opposed to the slightly toe- reasonable option for a person with a transradial amputation, as

out position used for walking. Persons with bilateral transfemo- in the case described above.57,58 The interface between the

ral or higher level amputations can also enjoy the benefits of residual limb and the prosthetic socket is also critical to prevent

cycling through the use of hand-powered, hand-controlled tri- skin breakdown with repetitive motion activities, and a roll-on

cycles or bicycles or specially designed tandem bicycles.9,50 liner should be considered in these instances. The prosthetic

Swimming and water-based activities: case. Discuss the componentry in general should be as lightweight as possible

advantages and disadvantages of prosthetic use for swimming and relatively simple in design so that mechanical failures are

with a 17-year-old female patient who presents after having minimized.

undergone a right transfemoral amputation because of osteo- The decision to use a body-powered system or a myoelectric

sarcoma. system depends primarily on the sport and the person’s prior

Discussion. Although prosthetic use is not allowed in of- experience with 1 system or another. Body-powered systems

ficially sanctioned competitive swimming events, specialized are commonly preferred for outdoor activities because they are

prosthetic componentry and fitting are very important for other versatile, durable, relatively lightweight, and able to function in

water-based activities. Whether a person is swimming in a pool various environments. The use of a quick-release wrist unit

or in an open-water environment, using a prosthesis can assist allows relatively simple exchange of terminal devices for dif-

with entry into and exit from the water. Use of the prosthesis in ferent activities. Terminal devices for most common sports and

the water, either with or without a fin attachment, also facili- recreational activities are now commercially available,e includ-

tates exercise and strengthening of the residual limb. The ing devices for holding hockey sticks, rackets, golf clubs,

buoyancy of the prosthesis can be problematic, although many bowling balls, fishing poles, baseball bats, and ski poles.56,57,59

prostheses can accommodate for this by allowing water to For musicians, devices are available for holding a drumstick,

partially fill the internal space during swimming.9,48 For per- violin bow, or flat pick.55-57 A terminal device useful for

sons who do not need a swim prosthesis but who may occa- golfing consists of a flexible cable attached between the golf

sionally be around water with their standard prosthesis, covers club and the prosthesis (fig 4). With it, the prosthesis provides

are available to provide protection from water damage. A added stability and power to the golf swing. It is approved by

beach or utility prosthesis can also be used for this purpose as the US Golf Association and can be changed from 1 club to

well as for showering.48 another. Flexible and durable hand devices are effective in

Specialized components for swim prostheses include ankle assisting a person with a unilateral upper limb deficiency to

systems such as the Activankle,d which can be locked at a catch a football or basketball or to throw a soccer ball (fig 5).

neutral position for walking and at a plantarflexion position for Padded or webbed devices are also available for swimming,

swimming. These systems are waterproof and salt resistant.9,52 and these can be used either with or without other specialized

Several waterproof knee units are also available for the trans- prosthetic components (fig 6). If a specific device is not com-

femoral amputee, and they can be used with either endoskeletal mercially available for a particular activity, the prosthetist and

or exoskeletal systems. A fin added to the prosthesis improves physician may have to be creative and develop a custom system

propulsion through the water and can allow the person with that will meet the needs of the person.21

limb loss to swim greater distances with less fatigue.53,54

For scuba diving and snorkeling, use of prostheses with

swim fin attachments are typically beneficial for the person

with a unilateral or a bilateral transtibial amputation. Those

with transfemoral or higher level amputations often prefer to

scuba dive or snorkel without a prosthesis.52 Persons with limb

deficiencies involving both the upper and the lower limbs can

also benefit from water-based activities, either with or without

custom-designed prosthetic devices. Aquatic activities can also

be a beneficial means of exercise and cardiopulmonary condi-

tioning for a person with multiple limb amputations.

Golf: case. Anticipate the prosthetic needs for a 42-year-

old man with a recent transradial amputation who is interested

in playing golf.

Discussion. For the person with an upper extremity defi-

ciency, various prosthetic components are available to allow

participation in sports and recreational activities.21,55-57 Al-

though some may choose not to use a prosthesis during sport or

recreational pursuits, they may still benefit from modifications

of the equipment to be used in their particular activity. In other Fig 4. Amputee Golf Grip.e Terminal device used for golfing.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 82, Suppl 1, March 2001

SPORTS AND RECREATION FOR PERSONS WITH LIMB DEFICIENCY, Webster S43

advances are expected to continue, offering all amputees

greater opportunity to pursue their leisure interests or to com-

pete with other athletes at the highest levels of competition.

The popularity of sports competitions for the disabled is also

expected to grow. Although currently perceived as highly ex-

perimental and controversial, the areas of direct skeletal attach-

ment of prosthetic devices and human bionics are likely to

challenge the current thinking in prosthetic componentry and

lead to advances for all persons with limb deficiency, including

those who participate in sports and recreational pursuits.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Brian Frasure (Hanger

Prosthetics, Raleigh, NC) for his expertise and contributions to this

article. The authors also recognize and thank the following corpora-

tions for their assistance and willingness to supply images utilized in

the article: Flex-Foot, Springlite, and TRS.

References

Fig 5. Re-Bound Probasketball hand device.e Terminal device used 1. Anderson TF. Aspects of sports and recreation for the child with

for basketball and other ball sports. a limb deficiency. In: Herring JA, Birch JG, editors. The child

with a limb deficiency. Rosemont (IL): American Academy Or-

thopaedic Surgeons; 1998. p 345-52.

2. Depauw KP, Gavron SJ. Disability and sport. Champaign (IL):

Persons with lower limb amputations who are interested in Human Kinetics; 1995.

playing golf also require several special prosthetic consider- 3. Richter KJ, Sherrill C, McCann BC, Mushett CA, Kaschalk SM.

ations.51 The socket, interface, and suspension considerations Recreation and sport for people with disabilities. In: DeLisa JA,

are similar to those previously described for any person who is Gans BM, editors. Rehabilitation medicine: principles and prac-

involved with recreational or sport activities. Secure suspen- tice. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. p 853-72.

sion and a shear-reducing interface are especially important. A 4. Bergeron JW. Athletes with disabilities. Phys Med Rehabil Clin

torque absorber placed distal to the socket can help to accom- North Am 1999;10:213-31.

5. McCann C. Sports for the disabled: the evolution from rehabili-

modate the added rotation needed during a golf swing. A tation to competitive sport. Br J Sports Med 1996;30:279-80.

multiaxial or low-profile dynamic elastic-response-type foot is 6. Tiessen JA, editor. The triumph of the human spirit. The Atlanta

advantageous for amputee golfers because it can accommodate paralympic experience. Oakville (Ont): Disability Today Publish-

to uneven terrain. A shock-absorbing pylon may also be a ing; 1997.

consideration in this population to help decrease pressure and 7. Shephard RJ. Benefits of sports and physical activity for the

shear on the residual limb. disabled: implications for the person and for society. Scand J

Rehabil Med 1991;23:51-9.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS 8. Chadderton HC. Consumer concerns in prosthetics. Prosthet Or-

thot Int 1983;7:15-6.

Advances in prosthetic technology and design have laid the 9. Kegel B, Webster JC, Burgess EM. Recreational activities of

foundation for the growth and development of recreational and lower extremity amputees: a survey. Arch Phys Med Rehabil

sports activities for persons with limb deficiency. These rapid 1980;61:258-64.

10. Nissen SJ, Newman WP. Factors influencing reintegration to

normal living after amputation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1992;73:

548-51.

11. Pandian G, Kowalske K. Daily functioning of patients with an

amputated lower extremity. Clin Orthop 1999;361:91-7.

12. US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical activity

and health: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): US

Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease

Control, and National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and

Health Promotion; 1996.

13. Sherrill C, Hinson M, Gench B, Kennedy SO, Low L. Self-

concepts of disabled youth athletes. Percept Mot Skills 1990;70:

1093-8.

14. Rimmer JH, Braddock D, Pitetti KH. Research on physical activ-

ity and disability: an emerging national priority. Med Sci Sports

Exerc 1996;28:1366-72.

15. Katz JF, Adler JC, Mazzarella NJ, Ince LP Psychological conse-

quences of an exercise training program for a paraplegic man: a

case study. Rehabil Psychol 1985;30:53-8.

16. National Consortium for Physical Education and Recreation for

Persons with Disabilities. Adapted physical education national

standards. Champaign (IL): Human Kinetics; 1995.

17. Nelson MA, Harris SS. The benefits and risks of sports and

exercise for children with chronic health conditions. In: Goldberg

B, editor. Sports and exercise for children with chronic health

conditions. Champaign (IL): Human Kinetics; 1995.

Fig 6. Freestyle Swimming Td device.e Terminal device used for 18. Johnstone KS, Perrin JCS. Sports for the handicapped child. Phys

swimming. Med Rehabil State Art Rev 1991;5:331-50.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 82, Suppl 1, March 2001

S44 SPORTS AND RECREATION FOR PERSONS WITH LIMB DEFICIENCY, Webster

19. Tanner RW, Forrest E. USA directory of sports organizations for 41. Michael J. Energy storing feet: a clinical comparison. Clin Pros-

athletes with disabilities. 3rd ed. Chicago: American Academy thet Orthot 1987;11:154-68.

Physical Medicine Rehabilitation Resident Physician Council; 42. Barth DG, Schumacher L, Thomas SS. Gait analysis and energy

1997. cost of below-knee amputees wearing six different prosthetic feet.

20. Kegel B. Adaptations for sports and recreation. In: Bowker JH, J Prosthet Orthot 1992;4:63-75.

editor. Atlas of limb prosthetics: surgical, prosthetic, and rehabil- 43. Gitter A, Czerniecki JM, DeGroot DM. Biomechanical analysis of

itation principles. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby Year Book; 1992. p the influence of prosthetic feet on below-knee amputee walking.

623-54. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1991;70:142-8.

21. Chang FM. Sports programs for the child with a limb deficiency. 44. Lehmann JF, Price R, Boswell-Bessette S, Dralle A. Questad K,

In: Herring JA, Birch JG, editors. The child with a limb defi-

deLateur BJ. Comprehensive analysis of energy storing prosthetic

ciency. Rosemont (IL): American Academy Orthopaedic Sur-

geons; 1998. p 361-77. feet: flex-foot and seattle foot versus standard SACH foot. Arch

22. Kegel B. Physical fitness: sports and recreation for those with Phys Med Rehabil 1993;74:1225-31.

lower limb amputation or impairment. J Rehabil Res Dev Clin 45. Menard MR, McBride ME, Sanderson DJ, Murray DD. Compar-

Suppl 1985;(1):1-125. ative biomechanical analysis of energy-storing feet. Arch Phys

23. McAnelly RD, Faulkner VW. Lower limb prostheses. In: Brad- Med Rehabil 1992;73:451-8.

dom RL, editor. Physical medicine and rehabilitation. Philadel- 46. Perry J, Stanfield S. Efficiency of dynamic elastic response pros-

phia: WB Saunders; 1996. p 289-320. thetic feet. J Rehabil Res Dev 1993;30:137-43.

24. Leonard JA Jr, Meier RH. Upper and lower extremity prosthetics. 47. Hsu MJ, Nielsen DH, Yack HJ, Shurr DG. Physiological mea-

In: DeLisa JA, Gans BM, editors. Rehabilitation medicine: prin- surements of walking and running in people with transtibial am-

ciples and practice. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. putations with 3 different prostheses. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther

p 669-96. 1999;29:526-33.

25. Evaluation and care of the lower limb amputee. In: Upper and 48. Michael JW, Gailey RS, Bowker JH. New developments in rec-

lower-limb prosthetics and orthotics for physicians and surgeons. reational prostheses and adaptive devices for the amputee. Clin

Evanston (IL): Prosthetic-Orthotic Center, Northwestern Univer- Orthop 1990;256:64-75.

sity Medical School; 1999. 49. Amputee Coalition of America. On yer bike. Tips on bicycle

26. Czerniecki JM, Gitter A. Cardiac rehabilitation in the lower ex- riding for lower limb amputees. Available at: http://www.ampu-

tremity amputee. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am 1995;6:311- teeonline.com/amputee/onyerbike.html. Accessed July 30, 2000.

30.

50. Mackie B, McGuiness B. Bicycling and the transtibial amputee.

27. Brown PS. The geriatric amputee. Phys Med Rehabil State Art

Rev 1990;4:67-76. Available at: http://www.amputeeonline.com/amputee/mackie.html.

28. Czerniecki JM, Gitter A, Weaver K. Effect of alterations in Accessed July 30, 2000.

prosthetic shank mass on the metabolic costs of ambulation in 51. Kegal B. Adaptations for sports and recreation. In: Bowker JH,

above-knee amputees. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1994;73:348-52. editor. Atlas of limb prosthetics: surgical, prosthetic, and rehabil-

29. Thomas JR. Training the child with lower limb loss to run. In: itation principles. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby Year Book; 1992. p

Herring JA, Birch JG, editors. The child with a limb deficiency. 623-54.

Rosemont (IL): American Academy Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1998. 52. Budde CM. Scuba divers know everybody’s blue in the ocean.

p 353-60. inMotion 1997;7(3):41-2.

30. Czerniecki JM, Gitter A. Insights into amputee running: a muscle 53. Saadah ES. Swimming devices for below-knee amputees. Prosthet

work analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1992;71:209-18. Orthot Int 1992;16:140-1.

31. Czerniecki JM, Gitter A, Beck JC. Energy transfer mechanisms as 54. Greene E. The fin. inMotion 1998;8(3):21-4.

a compensatory strategy in below knee amputee runners. J Bio- 55. Radocy B. Upper limb prosthetic adaptations for sports and rec-

mech 1996;29:717-22. reation. In: Bowker JH, editor. Atlas of limb prosthetics: surgical,

32. Sanderson DJ, Martin PE. Joint kinetics in unilateral below-knee prosthetic, and rehabilitation principles. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby

amputee patients during running. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996; Year Book; 1992. p 325-44.

77:1279-85. 56. Dillingham TR. Rehabilitation of the upper limb amputee. In:

33. Buckley JG. Sprint kinematics of athletes with lower-limb ampu- Rehabilitation of the injured combatant. Vol I. Washington (DC):

tations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999;80:501-8. Office of the Surgeon General at TMM Publications, Borden

34. Kapp S. Suspension systems for prostheses. Clin Orthop 1999; Institute, Walter Reed Army Medical Center; 1998. p 33-77.

361:55-62. 57. Radocy B. Upper-extremity prosthetics: considerations and de-

35. Datta D, Howitt J. Conventional versus microchip controlled signs for sports and recreation. Clin Prosthet Orthot 1987;11:131-

pneumatic swing phase control for trans-femoral amputees: user’s 53.

verdict. Prosthet Orthot Int 1998;22:129-35. 58. Radocy R, Beiswenger WD. A high performance, variable sus-

36. Pike A. The new high-tech prostheses. inMotion 1999;9(3):17-20. pension, transradial (below-elbow) prosthesis. J Prosthet Orthot

37. Esquenazi A, Torres MM. Prosthetic feet and ankle mechanisms. 1995;7:65-7.

Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am 1991;2:299-309. 59. Truong XT, Erickson R, Galbreath R. Baseball adaptation for

38. Romo HD. Specialized prostheses for activities: an update. Clin below-elbow prosthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1986;67:418.

Orthop 1999;361:63-70.

39. Huston C, Dillingham TR, Esquenazi A. Rehabilitation of the

lower limb amputee. In: Rehabilitation of the injured combatant. Suppliers

Vol 1. Washington (DC): Office of the Surgeon General at TMM a. Flex-Foot Inc, 27412-A Laguna Hills, Aliso Viejo, CA 92656.

Publications, Borden Institute, Walter Reed Army Medical Cen- b. Springlite, 1006 W Beardsley Pl, Salt Lake City, UT 84119.

ter; 1998. p 79-159. c. Ohio Willow Wood Co, 15441 Scioto-Darby Rd, PO Box 130, Mt

40. Macfarlane PA, Nielsen DH, Shurr DG, Meier K. Perception of Sterling, OH 43143.

walking difficulty by below-knee amputees using a conventional d. Rampro, 2021 Sheridan Rd, Leucadia, CA 92024.

foot versus the flex-foot. J Prosthet Orthot 1991;3:114-9. e. TRS Inc, 2450 Central Ave, Unit D, Boulder, CO 80301.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 82, Suppl 1, March 2001

View publication stats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Global Citizens AssignmentDocument9 pagesGlobal Citizens Assignmentapi-658645362No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Body Image Change in Amputee ChildrenDocument6 pagesBody Image Change in Amputee ChildrenMonishaNo ratings yet

- Astheticc of Prosthetic DeviceDocument21 pagesAstheticc of Prosthetic DeviceMonishaNo ratings yet

- A Demographic Study of Lower Limb Amputees in A NoDocument4 pagesA Demographic Study of Lower Limb Amputees in A NoMonishaNo ratings yet

- Sports Apdapation Lower Limb and Upper Limb ProsthesisDocument8 pagesSports Apdapation Lower Limb and Upper Limb ProsthesisMonishaNo ratings yet

- Amputee Report 1986Document17 pagesAmputee Report 1986MonishaNo ratings yet

- Pedro Carreño: SkillsDocument1 pagePedro Carreño: Skillsapi-253966222No ratings yet

- Historical Phases of CSRDocument12 pagesHistorical Phases of CSRHIMANSHU RAWATNo ratings yet

- NCP EamcDocument4 pagesNCP EamcsustiguerchristianpaulNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was: Running Head: Epidemiology Reaction Paper 1Document3 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Running Head: Epidemiology Reaction Paper 1Jayson AbadNo ratings yet

- Dental BooklistDocument14 pagesDental Booklistالمكتبة المليونيةNo ratings yet

- Diarrhoea CattleDocument11 pagesDiarrhoea CattleOnutza Elena Tătaru100% (1)

- Mavalli Tiffin Room (MTR) : A Brand HistoryDocument12 pagesMavalli Tiffin Room (MTR) : A Brand HistoryRohit GunwaniNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibiographyDocument7 pagesAnnotated Bibiographyapi-439568635No ratings yet

- Memorandum - Circular - No - 21-32 (DTI Operational Capacity Under Alert Level System)Document11 pagesMemorandum - Circular - No - 21-32 (DTI Operational Capacity Under Alert Level System)Brian TomasNo ratings yet

- Tetanus ProphylaxisDocument4 pagesTetanus ProphylaxisRifda LatifaNo ratings yet

- Physical Inactivity TestDocument66 pagesPhysical Inactivity TestNHEMSTERS xoxoNo ratings yet

- Hci Report Group3Document15 pagesHci Report Group3api-302906387No ratings yet

- Notification NIMH Various PostsDocument4 pagesNotification NIMH Various PostsKeshav RamNo ratings yet

- Book - Health and WellnessDocument10 pagesBook - Health and WellnessWill AsinNo ratings yet

- KKKDocument94 pagesKKKahmedhaji_sadikNo ratings yet

- Mahakal Institute of Pharamaceutical Studies, UjjainDocument8 pagesMahakal Institute of Pharamaceutical Studies, UjjainsafiyaNo ratings yet

- Paul Saville For Mayor of Bristol 2016Document5 pagesPaul Saville For Mayor of Bristol 2016Paul SavilleNo ratings yet

- LI Report Example1Document131 pagesLI Report Example1Spekza GamingNo ratings yet

- Module Overview: Session Date Tutor Lecture TopicDocument7 pagesModule Overview: Session Date Tutor Lecture TopicFiveer FreelancerNo ratings yet

- School Forms (Sf2) June-March 2015Document109 pagesSchool Forms (Sf2) June-March 2015Kristoffer Alcantara RiveraNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 1 Identifying Stress and RubricDocument2 pagesLesson Plan 1 Identifying Stress and Rubricapi-252461940No ratings yet

- MAPEH 7 Q4 Week 4Document9 pagesMAPEH 7 Q4 Week 4Maricris ArsibalNo ratings yet

- Fehling's Test: Comparative Test Reactions of CarbohydratesDocument33 pagesFehling's Test: Comparative Test Reactions of CarbohydratesTom Anthony Tonguia100% (1)

- Yildiz Technical University European Union Office Sample Test of English For Erasmus StudentsDocument2 pagesYildiz Technical University European Union Office Sample Test of English For Erasmus StudentsSerdar GurbanovNo ratings yet

- Electro-Chemiluminescence Immunoassay (ECLIA) For The Quantitative Determination of CEA in Human Serum and PlasmaDocument2 pagesElectro-Chemiluminescence Immunoassay (ECLIA) For The Quantitative Determination of CEA in Human Serum and Plasmamaricela carmen te desea lo mejorNo ratings yet

- Plan A 2025 CommitmentsDocument20 pagesPlan A 2025 CommitmentsReswinNo ratings yet

- CDC 118387 DS1Document132 pagesCDC 118387 DS1Sina AyodejiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10Document17 pagesChapter 10Bryle Dela TorreNo ratings yet

- GASTROINTESTINALDocument8 pagesGASTROINTESTINALrheantiffany0815No ratings yet