Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Clinical Implications of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Scores

Clinical Implications of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Scores

Uploaded by

주병욱Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Implications of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Scores

Clinical Implications of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Scores

Uploaded by

주병욱Copyright:

Available Formats

B R I T I S H J O U R N A L O F P S YC H I AT RY ( 2 0 0 5 ) , 1 8 7, 3 6 6 ^ 3 7 1

Clinical implications of Brief Psychiatric Rating METHOD

Database

Scale scores Original patient data from seven trials

(baseline n¼1979;

1979; 1361 men, 618 women;

STEFAN LEUCHT, JOHN M. KANE, WERNER KISSLING, age 35.8 years, s.d.¼10.6;

s.d. 10.6; weight 72.6 kg,

JOHANNES HAMANN, EVA ETSCHEL and ROLF ENGEL s.d.¼15.8;

s.d. 15.8; height 172 cm, s.d.¼9)

s.d. 9) compar-

ing amisulpride or olanzapine with other

antipsychotics or placebo, which used both

the original BPRS (Overall & Gorham,

1962) and the CGI (Guy, 1976), were

pooled for this analysis (Table 1). All

Background Despite the widespread The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; studies were randomised, and all but one

use of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Overall & Gorham, 1962) is one of the (Colonna et al, al, 2000) were double-blind.

most frequently used instruments for Each trial included patients with schizo-

(BPRS), the clinical meaning of its total

evaluating psychopathology in patients phrenia or schizophreniform disorder

score and cut-off values used to define with schizophrenia. Although its psycho- according to DSM–III–R or DSM–IV

treatment response are unclear. metric properties in terms of reliability, (American Psychiatric Association, 1987,

validity and sensitivity have been exten- 1994). With one exception (Carrière

(Carriere et al,

al,

Aims To link the BPRS to Clinical Global sively examined (for a comprehensive 2000), all studies required various mini-

Impression (CGI) ratings. review, see Hedlund & Vieweg, 1980), mum scores as eligibility criteria to assure

the clinical implications of BPRS scores that the patients had florid positive symp-

Method Equipercentile linking of BPRS are not always clear. For example, to toms. Please note that the criteria in

and CGI ratings from seven drug trials in our knowledge it has never been analysed Table 1 were eligibility criteria before the

acutely ill patients with schizophrenia how ill a patient with a BPRS total score wash-out phases. Some patients had

of say, 30, 50 or 90 actually is from a already improved during the wash-out

(n¼1979).

1979).

clinical judgement point of view. Further- phases and had scores below the eligibility

more, in clinical studies a reduction of at criteria at baseline. The patients in the

Results ‘Mildly ill’according to the CGI

least 20% (e.g. Kane et al,

al, 1988; Marder study without scale-derived minimum

approximately corresponded to a BPRS scores (Carrière

(Carriere et al,

al, 2000) were all in-

& Meibach, 1994), 30% (e.g. Arvanitis

total score of 31,‘moderately ill’to a BPRS et al,

al, 1997; Small et al, al, 1997), 40% patients and had a mean BPRS score of

score of 41and ‘markedly ill’to a BPRS (e.g. Beasley et al,

al, 1996) or 50% (e.g. 65 at baseline, so that patients with severe

score of 53.‘Minimally improved’according Peuskens & Link, 1997) of the initial symptoms were also involved in this study.

BPRS score has been used as a cut-off The mean BPRS total score at baseline in

to the CGI score was associated with

to define response, but what these cut- all studies was 58.9 (s.d.¼12.2)

(s.d. 12.2) and the

percentage BPRS reductions of 24, 27 and off levels mean clinically is again unclear. mean CGI – Severity scale score was 5.2

30% at weeks1, 2 and 4, respectively.The The Clinical Global Impression scale (s.d.¼0.8).

(s.d. 0.8). All studies used the 18-item ver-

corresponding numbers for a CGIrating of (CGI; Guy, 1976), another frequently sion of the BPRS with its original anchors;

‘much improved’ were 44, 53 and 58%. used instrument, is to some extent more the items were not derived from the Positive

informative in this regard: because it and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay

Conclusions The results provide a describes a patient’s overall clinical state & Fiszbein, 1987). The single items were

as a ‘global impression’ by the rater, it rated on a seven-point scale (1, not present;

clearer understanding of how to interpret

provides results that (in contrast to BPRS 2, very mild; 3, mild; 4, moderate; 5, mod-

BPRS total and percentage reduction erately severe; 6, severe; 7, extremely

scores) can be understood intuitively by

scores in clinical trials with patients acutely clinicians (Nierenberg & DeCecco, severe). Thus, the range of possible BPRS

ill with schizophrenia who are 2002). The purpose of our study there- total scores is from 18 to 126. The CGI –

experiencing positive symptoms. fore was to find – with statistical Severity (CGI–S) and the CGI – Global

means – corresponding points for BPRS Improvement (CGI–I) scales (Guy, 1976)

Declaration of interest None. and CGI ratings within a large sample were also available for all studies. The

Funding detailed in Acknowledgements. of patients with schizophrenia participat- CGI–S assesses the clinician’s impression

ing in antipsychotic drug trials. To know of the patient’s current illness state. The

which BPRS score corresponds to a rater is asked to ‘consider his total clinical

CGI – Severity rating of, for example, experience with the given population’. As

‘moderately ill’ or ‘severely ill’ or which with the BPRS, the time span considered

percentage BPRS reduction from base- is the week before the rating, and the fol-

line corresponds to a CGI – Improvement lowing scores can be given: 1, normal, not

rating of ‘minimally better’ or ‘much at all ill; 2, borderline mentally ill; 3, mildly

better’ could increase our understanding ill; 4, moderately ill; 5, markedly ill; 6,

of the clinical implications of BPRS severely ill; 7, among the most extremely

scores. ill patients. The CGI–I assesses the patient’s

366

https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.187.4.366 Published online by Cambridge University Press

C L INI C A L I M P L I C AT I ON S OF B P R S S C OR

ORE S

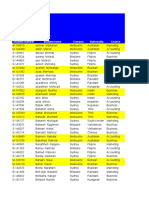

T

Table

able 1 Characteristics of the included studies

Study Antipsychotic drug used Sample size Duration (weeks) Selected patient characteristics Mean BPRS score at baseline

(n)

Mo

Moller

« ller et al (1997) Amisulpride, 191 6 In-patients with paranoid, disorganised or 61

haloperidol undifferentiated schizophrenia (DSM^III^

R), BPRS psychotic sub-score1 512 and at

least two BPRS psychosis items 54

Wetzel et al (1998) Amisulpride, 133 6 Acutely admitted in-patients with paranoid 53

flupentixol or undifferentiated schizophrenia, BPRS

total score 536, but no predominant

negative symptoms defined as SANS

composite score 455

Puech et al (1998) Amisulpride, 319 4 In-patients with acute exacerbations of 61

haloperidol paranoid, disorganised or undifferentiated

schizophrenia (DSM^III^R), BPRS

psychotic sub-score 512 and at least two

BPRS psychosis items 54

Colonna et al (2000) Amisulpride, 487 51 In- or out-patients with acute 56

haloperidol exacerbations of paranoid, disorganised or

undifferentiated schizophrenia (DSM^III^

R), at least two BPRS psychosis items 54

Carrie

Carriere

' re et al (2000) Amisulpride, 202 17 In-patients with paranoid schizophrenia or 65

haloperidol schizophreniform disorder (DSM^IV)

Peuskens et al (1999) Amisulpride, 228 8 In- or out-patients with paranoid, 55

risperidone disorganised or undifferentiated

schizophrenia (DSM^IV), BPRS total score

536, BPRS psychotic sub-score 512 and at

least two BPRS psychosis items 54

Beasley et al (1996) Olanzapine, haloperidol, 419 6 In-patients with acute exacerbations of 60

placebo schizophrenia (DSM^III^R), BPRS total

score 542

BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms.

1. Sum of conceptual disorganisation, suspiciousness, hallucinatory behaviour and unusual thought content.

improvement or worsening since the start variable measured without error and the then finds for every score of one variable

of the study using the following scores: 1, other as the dependent variable measured a score on the other variable that has the

very much improved; 2, much improved; with error. This is conceptually wrong, be- same percentile rank. The exact formulae

3, minimally improved; 4, no change; 5, cause both variables are measured with ran- are described in Chapter 2 of Kolen &

minimally worse; 6, much worse; 7, very dom error. Within the psychometric Brennan (1995). With regard to our large

much worse. A third item of the CGI, literature the search for corresponding database, no smoothing was applied, either

which tries to relate therapeutic effects points on different, but correlated, mea- to the cumulative distribution functions or

and side-effects – the efficacy index – was surement devices is referred to as ‘linking’ to the resulting linking functions. Only eva-

not used for the analysis. (Linn, 1993) or, in its most strict sense, as luations at baseline and at weeks 1, 2 and 4

‘equating’ (Kolen & Brennan, 1995). For were analysed, because although the dura-

this study we used equipercentile linking, tion of the studies ranged from 4 weeks to

Statistical analysis a technique that identifies those scores on 51 weeks not all studies provided data for

An often-used, but nevertheless inadequate, both measures that have the same percen- other time points, so that trial effects could

method to compare scores would have been tile rank. We used the SAS program EQUI- have biased the results. For each linking

to regress BPRS scores on CGI scores or PERCENTILE (Price et al, al, 2001), a task we included all patients with valid

vice versa. Both measures showed only realisation of the algorithms described by values on both measures, because analysing

median high correlations (see Results) Kolen & Brennan (1995). In the first step, the data only of those who completed the

and, therefore, regression equations would percentile rank functions are calculated studies would have implied a selection.

give different results depending on the for both variables. Using the percentile rank However, approximately 20% of the

direction of the regression equation. Linear function of one variable and the inverse patients withdrew between baseline and

regression treats one scale as the independent percentile rank function of the other, one week 4. In a sensitivity analysis we therefore

3 67

https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.187.4.366 Published online by Cambridge University Press

LEUCH T E T AL

included only patients who were still in the score of 30 at weeks 2 and 4. Being consid- improved’ (CGI–I score 1) corresponded

studies at week 4, so that a rating was avail- ered ‘moderately ill’ (CGI–S score 4) to percentage BPRS reductions of 71, 79

able at each time point. With the exception corresponded to BPRS total scores of 44 and 85% at weeks 1, 2 and 4, respectively.

of a somewhat more notable variation con- at baseline and 40 at weeks 1, 2 and 4. Thus there was a consistent time effect

cerning the association between the CGI–I ‘Markedly ill’ (CGI–S score 5) corre- indicating that a smaller percentage change

ratings much worse/very much worse and sponded to BPRS scores of 55 at baseline, in BPRS total score was necessary for a

percentage BPRS worsening of up to 4– 53 at weeks 1 and 2, and 52 at week 4. patient to be considered improved 1 week

6% BPRS points, the results were so similar ‘Severely ill’ (CGI–S score 6) corresponded after the initiation of treatment than at later

that only those of the primary analysis are to BPRS scores of 70 at baseline and 68, time points. This effect is also seen for

shown. 67 and 65 at weeks 1, 2 and 4, respectively. the ‘no change’ rating according to the

Extremely ill (CGI–S score 7) corresponded CGI–I (score 4), which was linked with a

to BPRS scores of 85 at baseline and 89, 84 5% BPRS score reduction at weeks 1 and

RESULTS

and 88 at weeks 1, 2 and 4, respectively. 2 and an 8% reduction at week 4.

Correlation between CGI Thus, the results were relatively consistent

and BPRS over the four time points examined,

Spearman correlation coefficients between although there was a slight tendency that, DISCUSSION

CGI–S ratings and BPRS total score were for a given BPRS score, CGI ratings were

0.41, 0.60, 0.68 and 0.74 respectively somewhat less severe at baseline and be- Although the BPRS is a frequently used and

for baseline (n

(n¼1905),

1905), week 1 (n(n¼1835),

1835), came more severe during the course of the psychometrically sound assessment device

week 2 (n(n¼1720)

1720) and week 4 (n(n¼1512);

1512); treatment. This effect, however, was collecting explicitly certain aspects of psy-

all P50.001. Spearman correlations neither large nor always consistent. chotic behaviour, the clinical meaning of a

between CGI–I score and percentage given scale value has not been anchored to

improvement of BPRS total score were a global clinical judgement. In our study

Linking of CGI ^ I score the psychometric procedure of equipercen-

70.72, 70.74 and 70.76 for week 1

and percentage BPRS change tile linking was used to link the BPRS to a

(n¼1829),

1829), week 2 (n(n¼1717)

1717) and week 4

from baseline clinically meaningful global rating. Apply-

(n¼1511)

1511) respectively; all P50.001.

Figure 2 shows the linking function ing this procedure in a large sample of

between the CGI–I scale and the percentage acutely ill patients across various multicen-

Linking of CGI ^ S score and BPRS BPRS change from baseline at weeks 1, 2 tre studies did result in a calibration or

total score and 4. Ratings of ‘minimally improved’ anchoring of the rating instrument to the

Figure 1 shows the result of the linking (CGI–I score 3) at weeks 1, 2 and 4 corre- clinical judgement. The linking functions

between CGI–S rating and the BPRS total sponded to percentage BPRS reductions of linking BPRS scores to the CGI can provide

score at baseline and at weeks 1, 2 and 4. 23, 27 and 30%, respectively. Ratings of a better understanding of the BPRS and can

They suggest that being considered ‘mildly ‘much improved’ (CGI–I score 2) corre- help clinicians to interpret the results of

ill’ on the CGI (CGI–S score 3) approxi- sponded to percentage BPRS reductions of clinical trials. For example, the data indi-

mately corresponded to a BPRS total score 44, 53 and 58% at weeks 1, 2 and 4, cate that trials in which the average BPRS

of 32 at baseline and at week 1 and a total respectively. Ratings of ‘very much total score at baseline was 40 are unlikely

Fig. 1 Linking of Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Severity score with Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) total score.

368

https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.187.4.366 Published online by Cambridge University Press

C L INI C A L I M P L I C AT I ON S OF B P R S S C OR

ORE S

Fig. 2 Linking of Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Improvement score with percentage reduction in Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) total score.

to have examined a severely ill population. of drug treatment and would be of ques- and statistical grounds (e.g. relatively low

Furthermore, frequently used cut-off points tionable clinical importance. In contrast to test–retest reliability in a heterogeneous

to define response in treatment trials – a 20 our findings, recent antipsychotic drug sample of patients with ‘schizophrenic,

or 50% reduction of the BPRS baseline trials in patients with acute exacerbations depressive and anxiety disorders’).

scores – seem to mean that on average the often used a 20 or 30% criterion to Although the algorithms for linking and

patients were ‘minimally improved’ and distinguish between responders and non- equating are the same, the terms have dif-

‘much improved’ respectively, according responders (Marder & Meibach,

Meibach, 1994; ferent meanings. For example, equating

to the raters’ clinical impression. In fact, Arvanitis et al,

al, 1997; Small et al,

al, 1997). two forms of a college admission test is

the data suggest that somewhat higher Ironically, the 20% cut-off level was indeed done to assure that both forms can be used

cut-off points than 20% (rather 25–30%) initially used in a study of patients with interchangeably and provide the same deci-

and 50% (rather 55%) might be better indi- refractory disease (Kane et al,

al, 1988), but sion. In our application the meaning is far

cators of ‘minimal improvement’ and was subsequently widely applied in studies less rigorous as the instruments differ,

‘much improvement’. of non-refractory cases. showing correlation coefficients for the

These results are relevant not only for The main strength of our analysis is the CGI–S v. BPRS total score comparison of

the readers of publications on antipsychotic large number of patients, which should 0.60–0.76 in weeks 1 to 4 and of only

drugs, but also for the definition of make the results rather robust. However, 0.40–0.41 at the baseline measurement.

response criteria of future trials: consider- a number of limitations of our analysis Linking is thus best understood here as

ing that a 25% BPRS score reduction means must be considered. Despite the widespread a kind of anchoring that helps in

that the patient is just minimally better use of the CGI in drug trials, there have understanding the clinical meaning of a

compared with baseline, this criterion been only a few studies of its psychometric given scale score. The correlation at base-

might be a useful cut-off for studying characteristics, so the CGI is certainly not line was especially low. This may in part

patients with treatment-refractory disease, an ideal measure for ‘evaluating’ the BPRS. be explained by the minimum of symptoms

but not for the ‘average’ patient. In In 116 patients with panic disorder and required at baseline by most studies, so that

treatment-refractory cases even a small depression, Leon et al (1993) found good variability was reduced, accounting for the

improvement in symptoms might be clini- concurrent validity and sensitivity for relatively low correlation.

cally important. However, in acutely ill change using the CGI. In two trials, Khan From a purely statistical point of view,

patients with non-refractory conditions, et al (2002, 2004) showed that the correlating an implicit difference rating

a 50% criterion (i.e. clinically much sensitivity of the CGI–S and CGI–I was (CGI–I rating) with an explicit, calculated

improved) would seem to be a more appro- similar to that of the Montgomery–Åsberg

Montgomery–Asberg ‘percentage improvement’ score is proble-

priate reflection of clinically meaningful Depression Rating Scale (Montgomery & matic. It was nevertheless reassuring that

improvement, because such patients usually Åsberg,

Asberg, 1979) and the Hamilton Rating these two measures showed higher correla-

respond well to antipsychotic drugs (Cole, Scale for Depression (Hamilton, 1960). tions than the severity scores themselves,

1964). Considering only a 25% reduction However, Beneke & Rasmus (1992) criti- thus demonstrating that clinicians are able

(i.e. only minimally improved) of the cised the CGI on semantic (e.g. asymmetric to give meaningful differential global

overall symptoms as a ‘response’ would scaling), logical (e.g. non-meaningful com- ratings reflecting something like a ‘relative

probably not meet clinicians’ expectations binations of CGI–S and CGI–I ratings) amount of change’. There was a time effect

369

https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.187.4.366 Published online by Cambridge University Press

LEUCH T E T AL

in the percentage BPRS reduction, suggest-

ing that a somewhat smaller ‘objective’

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

percentage change as measured by the

BPRS was necessary for patients to be con- & The linking functions linking Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) total scores to

sidered improved according to the CGI–I at

the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity ratings provide certain anchors that

1 week after the initiation of treatment than

may help in understanding the results of clinical trials.

at later weeks. This result probably reflects

physicians’ expectations, which may be & Studies in acutely ill, treatment-responsive patients with schizophrenia and positive

lower after short durations of treatment symptoms should use a 50% BPRS score reduction cut-off to define response rather

than at later stages. Whereas the investiga- than lower thresholds.

tors received training in BPRS rating before

the trials, this was usually not the case for & Linking CGI improvement ratings with percentage BPRS reduction showed a time

the CGI. Interrater reliabilities for the BPRS effect indicating that a smaller percentage BPRS change was necessary for a patient

between 0.87 and 0.97 have been reported to be considered improved1

improved 1 week after the initiation of treatment than at later time

(Collegium Internationale Psychiatrae points and suggesting that expectation bias might play a part in assessing

Scalarum, 1996). A small study reported improvement.

interrater reliabilities for the CGI–S and

the CGI–I of 0.66 and 0.51, respectively LIMITATIONS

(37 physicians rating 12 patients with

dementia; Dahlke et al, al, 1992). Recently a & The results are only generalisable to patients with schizophrenia and at least

somewhat better-anchored CGI scale for moderate positive symptoms.

patients with schizophrenia has been devel-

& The psychometric properties of the CGI have not been well evaluated, and the

oped (the Clinical Global Impression –

analysis should be repeated using better-anchored versions of this measure.

Schizophrenia scale) and its validity and

reliability have been verified: the interrater & Although using drug trial data to a certain extent reflects ‘real trial world’

reliability was 0.75 (Haro et al, al, 2003). A conditions, replication studies with specifically trained CGI raters would be useful.

replication with this new scale would be

useful. Such data could also show that a

more objective measure of clinical psycho-

pathology might be obtained by raters STEFAN LEUCHT, MD, Clinic and Polyclinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Technical University of Munich,

who were masked to which week of Germany, and Zucker Hillside Hospital, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, USA; JOHN M. KANE,

participation the patient is in. MD, Zucker Hillside Hospital, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, USA; WERNER KISSLING, MD,

It is important to emphasise the nature JOHANNES HAMANN, MD, Clinic and Polyclinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Technical University of

Munich; EVA ETSCHEL, ROLF ENGEL, PhD, Psychiatric Clinic, Ludwig Maximilian’s University, Munich,Germany

of the patients involved, as the results might

not be the same when different patient Correspondence: PD Dr Stefan Leucht,Klinik fu fur« r Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie derTechnischen

populations are analysed. We assembled a Universita

Universitat

« t Mu

Munchen,Klinikum

« nchen,Klinikum rechts der Isar, Ismaningerstrasse 22, 81675 MuMunchen,Germany.

« nchen,Germany.

data-set composed of people suffering from Stefan.Leucht @lrz.tu-muenchen.de

Tel: +49 89 414 0 4249; e-mail: Stefan.Leucht@

acute exacerbations of schizophrenia with

positive symptoms. For example, in (First received 14 September 2004, final revision 14 January 2005, accepted 28 January 2005)

patients suffering only from negative symp-

toms, the relationship between the BPRS

and the CGI – Severity scale might be very

different. Such patients could be considered patient populations (e.g. patients with REFERENCES

severely ill according to the CGI, but would residual schizophrenia and predominant

have relatively low BPRS total scores owing primary negative symptoms) and should American Psychiatric Association (1987) Diagnostic

to a lack of positive symptoms. Similarly, a use anchored versions of the CGI and spe- and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd edn,

50% BPRS reduction might have a different revised) (DSM ^ III ^ R).Washington, DC: APA.

cifically trained raters. In addition, efforts

clinical meaning in patients with low base- are under way to develop criteria for American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic

line BPRS scores. We therefore hasten to ‘remission’ that could be applied to schizo- and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edn)

emphasise that our results relate only to (DSM ^ IV).Washington, DC: APA.

phrenia and used in evaluating treatment

acutely ill patients with schizophrenia with effects in a more objective and consistent Andreasen, N., Carpenter,W., Kane, J., et al (2005)

positive symptoms similar to those included fashion (Andreasen et al,al, 2005).

Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and

rationale for consensus. American Journal of Psychiatry,

Psychiatry,

in our database.

162,

162, 441^449.

Despite these limitations, we consider

that the results are an important contri- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Arvanitis, L. A., Miller, B. G. & Seroquel Trial

Trial 13

Study Group (1997) Multiple fixed doses of ‘seroquel’

bution to a better understanding of the (quetiapine) in patients with acute exacerbation of

We are indebted to Sanofi-Aventis and Eli Lilly for

clinical meaning of the BPRS total score schizophrenia: a comparison with haloperidol and

allowing us to analyse individual patient data from

and percentage BPRS change in score in their database. The study was supported by a grant

placebo. Biological Psychiatry,

Psychiatry, 42,

42, 233^246.

acutely ill patients with schizophrenia. from the Zucker Hillside Hospital Intervention Beasley, C. M., Tollefson, G. D., Tran, P., et al (1996)

Future studies should examine other Research Center for Schizophrenia (MH-60575). Olanzapine versus haloperidol and placebo. Acute phase

370

https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.187.4.366 Published online by Cambridge University Press

C L INI C A L I M P L I C AT I ON S OF B P R S S C OR

ORE S

results of the American double-blind olanzapine trial. Kane, J. M., Honigfeld, G., Singer, J., et al (1988) Montgomery, S. A. & —sberg, M. (1979) A new

Neuropsychopharmacology,

Neuropsychopharmacology, 14,

14, 111^123. Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic. A depression scale designed to be sensitive to change.

double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Archives British Journal of Psychiatry,

Psychiatry, 134,

134, 382^389.

Rasmus, W. (1992) ‘Clinical Global

Beneke, M. & Rasmus,W.

of General Psychiatry,

Psychiatry, 45,

45, 789^796.

Impressions’ (ECDEU): some critical comments. Nierenberg, A. A. & DeCecco, L. M. (2002)

Pharmacopsychiatry,

Pharmacopsychiatry, 25,

25, 171^176. Kay, S. R. & Fiszbein, A. (1987) The positive and Definitions of antidepressant treatment response,

' re, P., Bonhomme, D. & Lempe¤ rie're,T. (2000) negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. remission, nonresponse, partial response, and other

Carrie

Carriere, Lemperiere,T.

Schizophrenia Bulletin,

Bulletin, 13,

13, 261^275. relevant outcomes: a focus on treatment-resistant

Amisulpride has superior benefit/risk profile to

depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry,

Psychiatry, 62 (suppl.), 5^9.

haloperidol in schizophrenia: results of a multicentre,

double-blind study (the Amisulpride Study Group). Khan, A., Khan, S. R., Shankles, E. B., et al (2002)

Overall, J. E. & Gorham, D. R. (1962) The Brief

European Psychiatry,

Psychiatry, 15,

15, 321^329. Relative sensitivity of the Montgomery ^Asberg

Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports,

Reports, 10,

10,

Depression Rating Scale, the Hamilton Depression

Cole, J. O. (1964) Phenothiazine treatment in acute 790^812.

rating scale and the Clinical Global Impressions rating

schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry,

Psychiatry, 10,

10, 246^261. scale in antidepressant clinical trials. International Clinical Peuskens, J. & Link, C. G. G. (1997) A comparison

Collegium Internationale Psychiatriae Scalarum Psychopharmacology,

Psychopharmacology, 17,17, 281^285. of quetiapine and chlorpromazine in the treatment of

(1996) Internationale Skalen fu

fur

« r Psychiatrie,

Psychiatrie, 4th edn. schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica,

Scandinavica, 96,

96,

Khan, A., Brodhead, A. E. & Kolts, R. L. (2004) 265^273.

Go

Gottingen:

« ttingen: Beltz Test.

Relative sensitivity of the Montgomery ^Asberg

Colonna, L., Saleem, P., Dondey-Nouvel, L., et al depression rating scale, the Hamilton depression Peuskens, J., Bech, P., Mo« ller, H. J., et al (1999)

Moller,

(2000) Long-term safety and efficacy of amisulpride in rating scale and the Clinical Global Impressions rating Amisulpride v. risperidone in the treatment of acute

subchronic or chronic schizophrenia. International Clinical scale in antidepressant clinical trials: a replication exacerbations of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research,

Research, 88,

88,

Psychopharmacology,

Psychopharmacology, 15,

15, 13^22. analysis. International Clinical Psychopharmacology,

Psychopharmacology, 19,

19, 107^117.

Dahlke, F., Lohaus, A. & Gutzmann, H. (1992)

157^160.

Price, L. R., Lurie, A. & Wilkins, C. (2001)

Reliability and clinical concepts underlying global EQUIPERCENT: A SAS program for calculating

Kolen, M. J. & Brennan, R. L. (1995) Test Equating:

judgements in dementia: implications for clinical equivalent scores using the equipercentile method.

Methods and Practices.

Practices. New York:

York: Springer.

research. Psychopharmacology Bulletin,

Bulletin, 28,

28, 425^432. Applied Psychological Measurement,

Measurement, 25,

25, 332.

Guy, W. (1976) Clinical Global Impressions: In ECDEU

Guy,W. Leon, A. C., Shear, M. K., Klerman, G. L., et al (1993)

Puech, A., Fleurot, O. & Rein, W. (1998)

Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology,

Psychopharmacology, pp. 218^222. A comparison of symptom determinants of patient and Amisulpride, an atypical antipsychotic, in the treatment

Revised DHEW Pub. (ADM). Rockville, MD: National clinician global ratings in patients with panic disorder and of acute episodes of schizophrenia: a dose-ranging

Institute for Mental Health. depression. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology,

Psychopharmacology, 13,

13, study v. haloperidol. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica,

Scandinavica, 98,

98,

327^331. 65^72.

Hamilton, M. (1960) A rating scale of depression.

Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry,

Psychiatry, 23,

23, Linn, R. L. (1993) Linking results of distinct assessments. Small, J. G., Hirsch, S. R., Arvanitis, L. A., et al

56^62. Applied Measurement in Education,

Education, 6, 83^102. (1997) Quetiapine in patients with schizophrenia. A

Haro, J. M., Kamath, S. A., Ochoa, S., et al (2003) high- and low-dose comparison with placebo. Archives of

Marder, S. R. & Meibach, R. C. (1994) Risperidone in General Psychiatry,

Psychiatry, 54,

54, 549^557.

The Clinical Global Impression

Impression^Schizophrenia

^Schizophrenia scale: a

simple instrument to measure the diversity of symptoms the treatment of schizophrenia. American Journal of

Psychiatry,

Psychiatry, 151,

151, 825^835. Wetzel, H., Grunder, G., Hillert, A., et al (1998)

present in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica,

Scandinavica,

Amisulpride versus flupentixol in schizophrenia with

107,

107, 16^23.

« ller, H. J., Boyer, P., Fleurot, O., et al (1997)

Mo

Moller, predominantly positive symptomatology ^ a double-

Hedlund, J. L. & Vieweg, B. W. (1980) The Brief Improvement of acute exacerbations of schizophrenia blind controlled study comparing a selective D-2-like

Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): a comprehensive with amisulpride: a comparison with haloperidol. antagonist to a mixed D-1-/D-2-like antagonist.

review. Journal of Operational Psychiatry,

Psychiatry, 11,

11, 48^65. Psychopharmacology,

Psychopharmacology, 132,

132, 396^401. Psychopharmacology,

Psychopharmacology, 137,

137, 223^232.

3 71

https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.187.4.366 Published online by Cambridge University Press

You might also like

- Statistics and Probability ReviewerDocument6 pagesStatistics and Probability ReviewerJoseph Cabailo75% (8)

- The Natural Gas Safety Rules 1991Document65 pagesThe Natural Gas Safety Rules 1991Laskar REAZ0% (3)

- Effects of Isometric, Eccentric, or Heavy Slow Resistance Exercises On Pain and Function With PTDocument15 pagesEffects of Isometric, Eccentric, or Heavy Slow Resistance Exercises On Pain and Function With PTTomBramboNo ratings yet

- BPRS - InterpretationDocument7 pagesBPRS - InterpretationKar Gayee100% (1)

- Determinants of Qualityof Life at First Presentation Determinants of Qualityof Life at First Presentation With Schizophrenia With SchizophreniaDocument5 pagesDeterminants of Qualityof Life at First Presentation Determinants of Qualityof Life at First Presentation With Schizophrenia With SchizophreniadomoNo ratings yet

- What Does The PANSS Mean?Document8 pagesWhat Does The PANSS Mean?Farin MauliaNo ratings yet

- ZiprasidoneHaloperidolHostilitySchizophreniaPoster CITROME CINP2006Document1 pageZiprasidoneHaloperidolHostilitySchizophreniaPoster CITROME CINP2006Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- Index LEQUESNE Indexes of Severity For Osteoarthritis of The Hip and KneeDocument5 pagesIndex LEQUESNE Indexes of Severity For Osteoarthritis of The Hip and KneeKanliajie Kresna KastiantoNo ratings yet

- Back Pain and Body Posture Evaluation Instrument For Adults: Expansion and ReproducibilityDocument9 pagesBack Pain and Body Posture Evaluation Instrument For Adults: Expansion and ReproducibilitydwimellyndaNo ratings yet

- Original PaperDocument9 pagesOriginal PaperSharvari ShahNo ratings yet

- Spearing, M. K., Post, R. M., Leverich, G. S., Brandt, D., & Nolen, W.Document13 pagesSpearing, M. K., Post, R. M., Leverich, G. S., Brandt, D., & Nolen, W.Isadora de PaulaNo ratings yet

- Acute and Transient Psychotic Disorders - Precursors, Epidemiology, Course and Outcome-Singh2004Document9 pagesAcute and Transient Psychotic Disorders - Precursors, Epidemiology, Course and Outcome-Singh2004Pedro IssaNo ratings yet

- Parent ArticleDocument6 pagesParent ArticleUzra ShujaatNo ratings yet

- The SQLSSelf-report Quality of Life Measure For People With SchizophreniaDocument6 pagesThe SQLSSelf-report Quality of Life Measure For People With SchizophreniaWulandari AdindaNo ratings yet

- The Oswestry Risk IndexDocument7 pagesThe Oswestry Risk IndexRamon LagoNo ratings yet

- What Is A Clinically Significant Reduction in HDRS-17?Document15 pagesWhat Is A Clinically Significant Reduction in HDRS-17?jasonNo ratings yet

- Assessing Mood Symptoms Through Heartbeat Dynamics A - 2017 - Journal of PsychiDocument10 pagesAssessing Mood Symptoms Through Heartbeat Dynamics A - 2017 - Journal of PsychiEden DingNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 06 Oct 2022Document21 pagesAdobe Scan 06 Oct 2022Minakshi KalraNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of The Effectiveness of Three Drug Regimens On Cognitive Performance of Patients With Parkinson's DiseaseDocument12 pagesA Comparison of The Effectiveness of Three Drug Regimens On Cognitive Performance of Patients With Parkinson's DiseaseGolita emsakiNo ratings yet

- Escala de DorDocument8 pagesEscala de DorTUTOR PAULO EDUARDO REDKVANo ratings yet

- A Rating Scale For Acute Drug-Induced Akathisia: Development, Reliability, and ValidityDocument9 pagesA Rating Scale For Acute Drug-Induced Akathisia: Development, Reliability, and ValidityPradhani Fakhira DhaneswariNo ratings yet

- ISPR8-1352: Posters (First Part) / Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 61S (2018) E103-E308 E219Document1 pageISPR8-1352: Posters (First Part) / Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 61S (2018) E103-E308 E219Amal VRNo ratings yet

- Computerized Assessment of BodDocument10 pagesComputerized Assessment of BodAna Gómez EstebanNo ratings yet

- RMD Open-2016-KalyoncuDocument9 pagesRMD Open-2016-KalyoncuneoslaveNo ratings yet

- Ams (2010)Document7 pagesAms (2010)DaypsiNo ratings yet

- SmallestdetectablechangeDocument4 pagesSmallestdetectablechangeBimo AnggoroNo ratings yet

- KernsDocument36 pagesKernsmalikadjerroud01No ratings yet

- The Body Attitude Test: Validation of The Spanish Version: Eating and Weight Disorders: EWD July 1999Document5 pagesThe Body Attitude Test: Validation of The Spanish Version: Eating and Weight Disorders: EWD July 1999Lorena Solana MartínezNo ratings yet

- Effect-Of-Aspirin-On-Hypothalamic PSCDocument5 pagesEffect-Of-Aspirin-On-Hypothalamic PSCCaioNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Trials Investigating Strength Training in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders PDFDocument5 pagesA Systematic Review of Trials Investigating Strength Training in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders PDFAgustin LopezNo ratings yet

- Sedation For Fibreoptic Gastroscopy: A Comparative Study of Midazolam and DiazepamDocument8 pagesSedation For Fibreoptic Gastroscopy: A Comparative Study of Midazolam and DiazepamRomaNo ratings yet

- CVA Reasoning Form PMRCDocument12 pagesCVA Reasoning Form PMRCsurbhi voraNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Three Scoring MethodsDocument9 pagesA Comparison of Three Scoring MethodseugeniaNo ratings yet

- Psychological Correlates of Outcome After Coronary Artery Bypass GraftDocument4 pagesPsychological Correlates of Outcome After Coronary Artery Bypass GraftVishnuPriyaDikkalaNo ratings yet

- Apathy in Currently Nondepressed Patients Treated With A SSRI For A Major Depressive Episode - Outcomes Following RandomDocument8 pagesApathy in Currently Nondepressed Patients Treated With A SSRI For A Major Depressive Episode - Outcomes Following RandomMooyongNo ratings yet

- Renal Resistive Index and Longterm in IRCDocument9 pagesRenal Resistive Index and Longterm in IRCsamuelNo ratings yet

- Bai 22Document4 pagesBai 22JungjackNo ratings yet

- RoCES D BlackSeaJPsyDocument13 pagesRoCES D BlackSeaJPsyPetru Madalin SchönthalerNo ratings yet

- Ji-Hua Xu 2018Document3 pagesJi-Hua Xu 2018Mary FallNo ratings yet

- Non-Steroidal Anti-In Ammatory Drugs For Spinal Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument11 pagesNon-Steroidal Anti-In Ammatory Drugs For Spinal Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysistanyasisNo ratings yet

- NH Màn Hình 2023-02-10 Lúc 14.11.27Document3 pagesNH Màn Hình 2023-02-10 Lúc 14.11.27hoàng nguyễnNo ratings yet

- Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews: Cindy Stroemel-Scheder, Bernd Kundermann, Stefan Lautenbacher TDocument18 pagesNeuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews: Cindy Stroemel-Scheder, Bernd Kundermann, Stefan Lautenbacher TAMBAR SOFIA SOTONo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Lower Limb Muscle Strength and 6-Minute Walk Test Performance in Stroke PatientsDocument4 pagesRelationship Between Lower Limb Muscle Strength and 6-Minute Walk Test Performance in Stroke PatientsGabriNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 3 PDFDocument4 pagesJurnal 3 PDFsufaNo ratings yet

- Effect of A Drug Holiday On Plasma ChlorDocument4 pagesEffect of A Drug Holiday On Plasma ChlorAdeyemi SegunNo ratings yet

- Recovery From Psychotic Illness A 15 and 25year International Followup StudyDocument12 pagesRecovery From Psychotic Illness A 15 and 25year International Followup StudyIoana MarchisNo ratings yet

- Calcular Regresión Simple PacienteDocument10 pagesCalcular Regresión Simple PacienteDavidNo ratings yet

- A New Method For Determining Levels of Sedation in Dogs - A Pilot Study With Propofol and A Novel Neuroactive Steroid AnestheticDocument7 pagesA New Method For Determining Levels of Sedation in Dogs - A Pilot Study With Propofol and A Novel Neuroactive Steroid AnestheticSalomé BonillaNo ratings yet

- Virtual Reality For Spinal Cord Injury-Associated Neuropathic Pain: Systematic ReviewDocument9 pagesVirtual Reality For Spinal Cord Injury-Associated Neuropathic Pain: Systematic ReviewAyat BissNo ratings yet

- J 1468-1331 2010 03092 XDocument10 pagesJ 1468-1331 2010 03092 XLauri VergaraNo ratings yet

- Muniz 2010Document7 pagesMuniz 2010seyedmohamadNo ratings yet

- PASAT Norms For The Portuguese PopulationDocument8 pagesPASAT Norms For The Portuguese PopulationMarília RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Is The Breadth of Individualized Ranges of Optimal Anxiety (IZOF) Equal For All Athletes? A Graphical Method For Establishing IZOFDocument8 pagesIs The Breadth of Individualized Ranges of Optimal Anxiety (IZOF) Equal For All Athletes? A Graphical Method For Establishing IZOFDextrexa Psicología del DeporteNo ratings yet

- Carroll2007 PDFDocument7 pagesCarroll2007 PDFgastro fkikunibNo ratings yet

- Duong 2018Document27 pagesDuong 2018lazaro jara andradeNo ratings yet

- GMA Guide 2020Document8 pagesGMA Guide 2020CamilaNo ratings yet

- 2 - PDFsam - EurJGeriatricGerontol 2 13 enDocument1 page2 - PDFsam - EurJGeriatricGerontol 2 13 enSuck my PenisNo ratings yet

- International Headache Society Headache Diagnostic Patterns in Pain Facility PatientsDocument16 pagesInternational Headache Society Headache Diagnostic Patterns in Pain Facility PatientstamiNo ratings yet

- Radloff 1977Document17 pagesRadloff 1977Fitrisia AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Lukasiewicz2013 PDFDocument13 pagesLukasiewicz2013 PDFmaghfiraniNo ratings yet

- The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric Features and Clinical CorrelatesDocument8 pagesThe Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric Features and Clinical CorrelatesKariena PermanasariNo ratings yet

- INVOICE VAT No. 1221060058Document1 pageINVOICE VAT No. 1221060058주병욱No ratings yet

- Thesis AccessDocument286 pagesThesis Access주병욱No ratings yet

- Suicide Life Threat Behav - 2018 - Turner - Experiencing and Resisting Nonsuicidal Self Injury Thoughts and Urges inDocument15 pagesSuicide Life Threat Behav - 2018 - Turner - Experiencing and Resisting Nonsuicidal Self Injury Thoughts and Urges in주병욱No ratings yet

- The Course of Bipolar DisorderDocument11 pagesThe Course of Bipolar Disorder주병욱No ratings yet

- Defining Treatment Response, Remission, Relapse, and RecoveryDocument21 pagesDefining Treatment Response, Remission, Relapse, and Recovery주병욱No ratings yet

- Psychiatry ResearchDocument6 pagesPsychiatry Research주병욱No ratings yet

- Voltage Drop & Cable Sizing & Electrical LoadDocument26 pagesVoltage Drop & Cable Sizing & Electrical Loadfd270% (1)

- Mathematics p1 (Eng) 2024Document10 pagesMathematics p1 (Eng) 2024Mahlatse S Sedibeng100% (1)

- OOPS ConceptsDocument9 pagesOOPS ConceptsVijay ChikkalaNo ratings yet

- Application ListDocument30 pagesApplication ListMario AlcazabaNo ratings yet

- Week6 (Aco and Pso)Document55 pagesWeek6 (Aco and Pso)Karim Abd El-GayedNo ratings yet

- Android DatePicker Example - JavatpointDocument7 pagesAndroid DatePicker Example - JavatpointimsukhNo ratings yet

- User Instructions: Domestic Garage Door OperatorsDocument16 pagesUser Instructions: Domestic Garage Door OperatorsJack Smith100% (1)

- Size Exclusion ChortamographyDocument124 pagesSize Exclusion ChortamographyViviana CastilloNo ratings yet

- ATi Radeon R300 SeriesDocument5 pagesATi Radeon R300 SeriesHeikkiNo ratings yet

- NRL VFD Datasheet FormatDocument5 pagesNRL VFD Datasheet FormatDebashish ChattopadhyayaNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Pelatihan Dan Lingkungan Kerja Terhadap Kinerja KaryawanDocument10 pagesPengaruh Pelatihan Dan Lingkungan Kerja Terhadap Kinerja KaryawanferdiantiNo ratings yet

- 2013 Post Promo Exam TimetableDocument5 pages2013 Post Promo Exam Timetablemin95No ratings yet

- Insulation Resistance (IR) Values - Electrical Notes & ArticlesDocument28 pagesInsulation Resistance (IR) Values - Electrical Notes & ArticlesjengandxbNo ratings yet

- VLSI Concepts - VLSI BASIC ImportantDocument6 pagesVLSI Concepts - VLSI BASIC ImportantIlaiyaveni IyanduraiNo ratings yet

- Gas Laws: Jacques Charles (1746 - 1823)Document5 pagesGas Laws: Jacques Charles (1746 - 1823)cj lequinNo ratings yet

- 401b Intro To Atom Presentation NotesDocument16 pages401b Intro To Atom Presentation Notes28veralNo ratings yet

- Parker SSD Drives 650 Series Quick Start GuideDocument2 pagesParker SSD Drives 650 Series Quick Start Guideeng_karamazabNo ratings yet

- IPP-I As Per Generic CurriculumDocument380 pagesIPP-I As Per Generic CurriculumamarnesredinNo ratings yet

- Redis - 5. DebuggingDocument4 pagesRedis - 5. DebuggingDiogenesNo ratings yet

- Trinabh Shridhar - Individual Quiz CompletedDocument11 pagesTrinabh Shridhar - Individual Quiz CompletedSneha DhamijaNo ratings yet

- UsbFix ReportDocument6 pagesUsbFix ReportlcandoNo ratings yet

- RAP 2022 Book of AbstractsDocument166 pagesRAP 2022 Book of AbstractsMilena ZivkovicNo ratings yet

- Problems On Trains PDFDocument15 pagesProblems On Trains PDFloveNo ratings yet

- Ss 1 Further Mathematics Vectors Lesson 7Document2 pagesSs 1 Further Mathematics Vectors Lesson 7Adio Babatunde Abiodun Cabax100% (1)

- Levo Tablets USPDocument2 pagesLevo Tablets USPNikhil Sindhav100% (3)

- Elastic-Viscoplastic ModelDocument13 pagesElastic-Viscoplastic ModelDan AlexandrescuNo ratings yet

- Lms Length Boys 3mon PDocument1 pageLms Length Boys 3mon PArdi IswaraNo ratings yet

- Unconventional Machining Processes - Introduction and ClassificationDocument3 pagesUnconventional Machining Processes - Introduction and ClassificationVishal KumarNo ratings yet