Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Training Evaluation1

Training Evaluation1

Uploaded by

sirajuddin islamCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Phrasebank ManchesterDocument19 pagesPhrasebank ManchesterHarold QuilangNo ratings yet

- Letter of Recommendation: Please Type Neatly. To Be Filled by The ApplicantDocument2 pagesLetter of Recommendation: Please Type Neatly. To Be Filled by The ApplicantTresna Maulana100% (2)

- Training Effectiveness Measurement for Large Scale Programs: Demystified!From EverandTraining Effectiveness Measurement for Large Scale Programs: Demystified!No ratings yet

- Level 6 Diploma - Unit 3 Assignment Guidance - April 2015Document10 pagesLevel 6 Diploma - Unit 3 Assignment Guidance - April 2015Jaijeev PaliNo ratings yet

- Q059 Wang 2006Document12 pagesQ059 Wang 2006Heinz PeterNo ratings yet

- Training EvaluationDocument12 pagesTraining EvaluationRana ShakoorNo ratings yet

- HRD Program Evaluation CH 9Document31 pagesHRD Program Evaluation CH 9Tesfaye KebedeNo ratings yet

- Literaturereview TperezDocument16 pagesLiteraturereview Tperezapi-705656960No ratings yet

- HRD CHP 7Document34 pagesHRD CHP 7kamaruljamil4No ratings yet

- Team D Program Evaluation Training MaterialDocument11 pagesTeam D Program Evaluation Training Materialapi-367023602No ratings yet

- Evaluation of Training Programmes: BackgroundDocument7 pagesEvaluation of Training Programmes: BackgroundUpadhayayAnkurNo ratings yet

- Case Study Application of Dmaic To Academic Assessment in Higher EducationDocument10 pagesCase Study Application of Dmaic To Academic Assessment in Higher EducationAmir ShahzadNo ratings yet

- hrd-3 NewDocument18 pageshrd-3 Newjeevangowdas476No ratings yet

- Tutorial HRM 549 Chapter 1Document4 pagesTutorial HRM 549 Chapter 1Shira EjatNo ratings yet

- Training & Development - 1525Document9 pagesTraining & Development - 1525Durjoy SharmaNo ratings yet

- Methods of Training Programmes Evaluation: A Review: April 2014Document13 pagesMethods of Training Programmes Evaluation: A Review: April 2014AnkitaNo ratings yet

- Discussion 5Document4 pagesDiscussion 5Nordia Black-BrownNo ratings yet

- Assignment Iee& GG: Submitted By: Obaid KhurshidDocument3 pagesAssignment Iee& GG: Submitted By: Obaid KhurshidObaid Khurshid MughalNo ratings yet

- How To Evaluate Your Faculty Development Services - Academic Briefing - Higher Ed Administrative LeadershipDocument10 pagesHow To Evaluate Your Faculty Development Services - Academic Briefing - Higher Ed Administrative LeadershipSherein ShalabyNo ratings yet

- Training and DDocument8 pagesTraining and DAkshay BadheNo ratings yet

- CIPP Evaluation ModelDocument6 pagesCIPP Evaluation ModelReynalyn GozunNo ratings yet

- Addie ModeelDocument4 pagesAddie ModeelSaira AzizNo ratings yet

- Training and Development (CHAPTER 6)Document8 pagesTraining and Development (CHAPTER 6)JaneaNo ratings yet

- Training ModelDocument8 pagesTraining ModelSyful An-nuarNo ratings yet

- Dissertation DraftDocument49 pagesDissertation DraftKrithika YagneshwaranNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Training - Beyond Reaction EvaluationDocument18 pagesEvaluating Training - Beyond Reaction Evaluationpooja_patnaik237No ratings yet

- Evaluation of Training and Development: An Analysis of Various ModelsDocument7 pagesEvaluation of Training and Development: An Analysis of Various Modelsdharshn12345No ratings yet

- Dissertation ReportDocument99 pagesDissertation Reportvidhuarora1840100% (1)

- Florence P. Querubin Report in Evaluation of S&T EducationDocument15 pagesFlorence P. Querubin Report in Evaluation of S&T EducationFlorence QuerubinNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Various Training Evaluation ModelsDocument9 pagesAn Analysis of Various Training Evaluation ModelsRanaa hannaNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Various Training Evaluation ModelsDocument9 pagesAn Analysis of Various Training Evaluation ModelsRajeshNo ratings yet

- A Literature Review On Various Models For Evaluating Training ProgramsDocument9 pagesA Literature Review On Various Models For Evaluating Training ProgramsKacang BakarNo ratings yet

- Training EffectivenessDocument10 pagesTraining EffectivenessdeepmaniaNo ratings yet

- Study of Training and Development: Audit and Evaluation Division March 2002Document26 pagesStudy of Training and Development: Audit and Evaluation Division March 2002Irene Joy ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Final LR 1Document8 pagesFinal LR 1mansi trivediNo ratings yet

- 5068 Preskill Chapter 5Document80 pages5068 Preskill Chapter 5pj501No ratings yet

- The Application Strategic Planning and Balance Scorecard Modelling in Enhance of Higher EducationDocument5 pagesThe Application Strategic Planning and Balance Scorecard Modelling in Enhance of Higher Educationc1rkeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 - Training EvaluationDocument28 pagesChapter 6 - Training EvaluationChaudry AdeelNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Evaluation of TrainingDocument9 pagesApproaches To Evaluation of Trainingdhavalchothani1616No ratings yet

- Principles and Processes in Coaching Evaluation: Degray School of Management, University of SurreyDocument15 pagesPrinciples and Processes in Coaching Evaluation: Degray School of Management, University of SurreyReiki TerapiasNo ratings yet

- Training Programme Evaluation: Training and Learning Evaluation, Feedback Forms, Action Plans and Follow-UpDocument14 pagesTraining Programme Evaluation: Training and Learning Evaluation, Feedback Forms, Action Plans and Follow-UpDiana Vivisur100% (1)

- Training Evaluation: 6 Edition Raymond A. NoeDocument28 pagesTraining Evaluation: 6 Edition Raymond A. Noepanthoh1No ratings yet

- Operational DefinitionsDocument4 pagesOperational DefinitionsTomika RodriguezNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of Evaluation Practice: The Kirkpatrick Model and The Principle of BeneficenceDocument8 pagesA Critical Analysis of Evaluation Practice: The Kirkpatrick Model and The Principle of BeneficenceDedet TriwahyudiNo ratings yet

- Training and Development Program FinalDocument27 pagesTraining and Development Program FinalRahil KhanNo ratings yet

- Douglah. Concept of Program EvaluationDocument0 pagesDouglah. Concept of Program EvaluationThelma Pineda GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Section 4:: Evaluation of Professional DevelopmentDocument16 pagesSection 4:: Evaluation of Professional DevelopmentMaria RicNo ratings yet

- HRM - C - 5 HRD Done + BestDocument21 pagesHRM - C - 5 HRD Done + BestAbraham BizualemNo ratings yet

- Unit 13: Training: ObjectivesDocument30 pagesUnit 13: Training: Objectivesg24uallNo ratings yet

- Creating Training and Development Programs: Using The ADDIE MethodDocument5 pagesCreating Training and Development Programs: Using The ADDIE MethodYayan NadzriNo ratings yet

- Rana G PDFDocument7 pagesRana G PDFAbdul MajidNo ratings yet

- Models of TrainingDocument6 pagesModels of TrainingNishita Jain100% (1)

- Evaluating Learning Develop - 20221129T122816Document8 pagesEvaluating Learning Develop - 20221129T122816Sanja KutanoskaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation ModelDocument7 pagesEvaluation ModelHumaizah MaiNo ratings yet

- IJBGM - Evaluation of Training Effectiveness Based On Reaction A Case StudyDocument12 pagesIJBGM - Evaluation of Training Effectiveness Based On Reaction A Case Studyiaset123No ratings yet

- THE IMPACT STUDY ON EFFECTIVENESS OF AKEPT'S T& L TRAINING PROGRAMMESDocument86 pagesTHE IMPACT STUDY ON EFFECTIVENESS OF AKEPT'S T& L TRAINING PROGRAMMEShanipahhussinNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Training Evaluation: StructureDocument15 pagesUnit 2 Training Evaluation: StructurevinothvinozonsNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of Evaluation Practice: The Kirkpatrick Model and The Principle of BeneficenceDocument8 pagesA Critical Analysis of Evaluation Practice: The Kirkpatrick Model and The Principle of BeneficenceMru KarNo ratings yet

- Chapter VI: Recommendations and ConclusionsDocument34 pagesChapter VI: Recommendations and ConclusionsSrini VasNo ratings yet

- Riccard Multigenerational Tiered AssessmentDocument9 pagesRiccard Multigenerational Tiered Assessmentapi-519873112No ratings yet

- Allen, W. (N.D) - Selecting Evaluation Questions and TypesDocument6 pagesAllen, W. (N.D) - Selecting Evaluation Questions and Typesken macNo ratings yet

- The Value of Learning: How Organizations Capture Value and ROI and Translate It into Support, Improvement, and FundsFrom EverandThe Value of Learning: How Organizations Capture Value and ROI and Translate It into Support, Improvement, and FundsNo ratings yet

- Q1 G7 Worksheet Direct and Reported SpeechDocument5 pagesQ1 G7 Worksheet Direct and Reported SpeechQueeny Abiera TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Nouns Regular and IrregularDocument9 pagesNouns Regular and Irregularkenken2No ratings yet

- B.Sc. Paramedical Sciences Selection List 6: Fee Details Head FeeDocument2 pagesB.Sc. Paramedical Sciences Selection List 6: Fee Details Head FeeLex LexiconNo ratings yet

- 1.1 Definitions and Classifications Building MaterialsDocument7 pages1.1 Definitions and Classifications Building Materialsjack.simpson.changNo ratings yet

- B. Sample Annotated Bibliography Dr. Alvin S. SicatDocument6 pagesB. Sample Annotated Bibliography Dr. Alvin S. SicatJeremy James AlbayNo ratings yet

- December Gasetan Guihan Newsletter 2019Document4 pagesDecember Gasetan Guihan Newsletter 2019api-250691083No ratings yet

- Needs Analysis Questionnaire - EnglishDocument8 pagesNeeds Analysis Questionnaire - EnglishBeatrice BacalbasaNo ratings yet

- Industrial Training Presentation Evaluation Form - Industry SVDocument3 pagesIndustrial Training Presentation Evaluation Form - Industry SVazlanazmanNo ratings yet

- Dayton Christian School System: 9391 Washington Church Road Miamisburg, OH 45342 Phone: 937.291.7201Document7 pagesDayton Christian School System: 9391 Washington Church Road Miamisburg, OH 45342 Phone: 937.291.7201bdavis9474No ratings yet

- A Career in Accounting Tips On How You Can Be SuccessfulDocument2 pagesA Career in Accounting Tips On How You Can Be SuccessfulCarlos DNo ratings yet

- Case Study Updated TAPF Food Security 27022019 ReviewedDocument17 pagesCase Study Updated TAPF Food Security 27022019 Reviewedguptha mukthaNo ratings yet

- Punctuation Marks Lesson Plan by Patricia Leigh GonzalesDocument2 pagesPunctuation Marks Lesson Plan by Patricia Leigh GonzalesPatricia Leigh GonzalesNo ratings yet

- 4 Managerial EconomicsDocument8 pages4 Managerial EconomicsBoSs GamingNo ratings yet

- DLL Week 3Document5 pagesDLL Week 3Maye S. AranetaNo ratings yet

- Introductory Message: Welcome Dear Marians To School Year 2020-2021!Document17 pagesIntroductory Message: Welcome Dear Marians To School Year 2020-2021!Medelyn Butron PepitoNo ratings yet

- Ajay Rana: ObjectiveDocument3 pagesAjay Rana: ObjectiveManish KumarNo ratings yet

- AdmissionsResumeTemplate - RotmanDocument1 pageAdmissionsResumeTemplate - RotmanAlan0% (1)

- Education in Egypt: Conversation 1Document12 pagesEducation in Egypt: Conversation 1Mahmoud Nady Zakria Sadek SadekNo ratings yet

- 2AC K BlocksDocument165 pages2AC K BlocksBrody Diehn100% (1)

- ADHD-converted-converted-converted 2Document23 pagesADHD-converted-converted-converted 2ROSHANI YADAVNo ratings yet

- Community Organizing: Addams and AlinskyDocument40 pagesCommunity Organizing: Addams and AlinskymaadamaNo ratings yet

- Wandering by Sarah Jane CervenakDocument34 pagesWandering by Sarah Jane CervenakDuke University Press100% (3)

- .. To Officially Announce That You Have Decided To Leave Your Job or An Organization QuitDocument25 pages.. To Officially Announce That You Have Decided To Leave Your Job or An Organization QuitLê Nguyễn Bảo DuyNo ratings yet

- DL Archaeology and Ancient HistoryDocument28 pagesDL Archaeology and Ancient HistoryDaniel Barbo LulaNo ratings yet

- Punjab University College of Information Technology (Pucit) : Database Systems Lab 2Document2 pagesPunjab University College of Information Technology (Pucit) : Database Systems Lab 2Lyeba AjmalNo ratings yet

- Visa Interview-F1 - USDocument7 pagesVisa Interview-F1 - USOPDSS SRINIVASNo ratings yet

- Edu 533/535-Assessment of Learning: Palasol, Kenneth T. A-COE-08 Bsed - Fil. Iv EDU 259Document6 pagesEdu 533/535-Assessment of Learning: Palasol, Kenneth T. A-COE-08 Bsed - Fil. Iv EDU 259Mike Angelo Gare PitoNo ratings yet

Training Evaluation1

Training Evaluation1

Uploaded by

sirajuddin islamCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Training Evaluation1

Training Evaluation1

Uploaded by

sirajuddin islamCopyright:

Available Formats

Advances in Developing Human

Resources

http://adh.sagepub.com

Training Evaluation: Knowing More Than Is Practiced

Greg G. Wang and Diane Wilcox

Advances in Developing Human Resources 2006; 8; 528

DOI: 10.1177/1523422306293007

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://adh.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/8/4/528

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Academy of Human Resource Development

Additional services and information for Advances in Developing Human Resources can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://adh.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://adh.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations (this article cites 20 articles hosted on the

SAGE Journals Online and HighWire Press platforms):

http://adh.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/8/4/528

Downloaded from http://adh.sagepub.com at Airlangga University on September 25, 2008

Training Evaluation: Knowing

More Than Is Practiced

Greg G.Wang

Diane Wilcox

The problem and the solution. Training program evaluation is an

important and culminating phase in the analysis, design, develop,

implement, evaluate (ADDIE) process. However, evaluation has often

been overlooked or not implemented to its full capacity. To assess

and ensure the quality, effectiveness, and the impact of systematic

training, this article emphasizes the importance of summative evalu-

ation at the last phase of ADDIE and presents developments toward

a summative evaluation framework of training program effectiveness.

The focus is the connection of final summative evaluation to the

direction provided by the analysis phase and the concerns of the

host organization.

Keywords: formative evaluation; summative evaluation; ISD; outcome

evaluation; impact evaluation

As a systematic process for developing needed workplace knowledge and

expertise, instructional systems design requires an evaluation component to

determine if the training program achieved its intended goal—if it did what it

purported to do. However, evaluation, the last phase of the ADDIE (analysis,

design, develop, implement, evaluate) model, is often overlooked when orga-

nizations create and implement training programs. Strictly speaking, the larger

view of evaluation may not be treated as a separate phase during the process.

It is indeed an ongoing effort throughout all phases of the ADDIE process

(Hannum & Hansen, 1989) and culminating at the last phase.

A number of reasons have been noted for organizations failing to conduct

systematic evaluations. First, many training professionals either do not believe

in evaluation or do not possess the mind-set necessary to conduct evaluation

(Swanson, 2005). Others do not wish to evaluate their training programs

because of the lack of confidence in whether their programs add value to, or

have impact on, organizations (Spitzer, 1999). Lack of evaluation in training

was also attributed to the lack of resources and expertise, as well as lack of an

organization culture that supports such efforts (Desimone, Werner, & Harris,

Advances in Developing Human Resources Vol. 8, No. 4 November 2006 528-539

DOI: 10.1177/1523422306293007

Copyright 2006 Sage Publications

Downloaded from http://adh.sagepub.com at Airlangga University on September 25, 2008

Wang, Wilcox / TRAINING EVALUATION 529

2002; Moller, Benscoter, & Rohrer-Murphy, 2000). Even for limited efforts in

training evaluation, most are retrospective in nature (Brown & Gerhardt, 2002;

Wang & Wang, 2005). A study of a group of instructional design practitioners

indicated that 89.5% of those conduct end-of-course evaluation, 71% evaluate

learning; however, only 44% use acceptable techniques for measuring achieve-

ment. Yet merely 20% of those surveyed correctly identified methods for

results evaluation (Moller & Mallin, 1996). Brown and Gerhardt (2002) con-

cluded that companies expend even less effort in evaluating the instructional

design process.

The purpose of this article is to examine program evaluation throughout the

ADDIE process for systematic training design. In particular, we focus on the

importance of summative or outcome evaluation at the evaluation phase. By

presenting developments of summative evaluation, we argue that result-oriented

evaluation is critical to ensure the quality and desired outcomes of systematic

training.

Formative and Summative Evaluation

In a broad sense, training program evaluation can be divided into two cate-

gories, formative evaluation and summative evaluation (Noe, 2002; Scriven,

1996). An evaluation intended to provide information on improving program

design and development is called formative evaluation (Scriven, 1991).

Specifically, the purpose of formative evaluation is to identify weakness in

instructional material, methods, or learning objectives with the intention to

develop prescriptive solutions during training program design and develop-

ment (Brown & Gerhardt, 2002). A further purpose of formative evaluation is

to help form and shape the program quality to perform better and should be

built into each of the ADDIE phases. It should be an ongoing, integrated effort

throughout all phases of the ADDIE process (Hannum & Hansen, 1989).

Therefore, formative evaluation should be imbedded in the entire systematic

training process.

In contrast, an evaluation conducted to determine whether intended training

goals and outcomes are achieved is called a summative evaluation (Scriven,

1991). Summative evaluation is conducted after a training program has been

delivered. It is the focus of this discussion of the fifth phase in the ADDIE

model. A major purpose of summative evaluation is to render a summary judg-

ment or conclusion through measurement and assessment of program outcomes.

Summative Evaluation

Summative evaluation, the focus of the evaluation phase of systematic

training, is centered on training outcomes (Alvarez, Salas, & Garofano, 2004).

It seeks to identify the benefits of training to individuals and organizations in

the form of learning and enhanced on-the-job performance that were specified

Downloaded from http://adh.sagepub.com at Airlangga University on September 25, 2008

530 Advances in Developing Human Resources November 2006

in the analysis phase. There are several major purposes for organizations to

conduct summative evaluation after systematic training. First, summative eval-

uation connects all the ADDIE phases in systematic training with organiza-

tional goals and objectives. It will not only justify the training budget and

human resource development (HRD) investment but also validate imple-

mented interventions. More importantly, it demonstrates to the organization

decision makers the value of training interventions. Second, systematic sum-

mative evaluation may discover the areas of training interventions that do not

meet the stakeholders’ expectations. Such evaluation will certainly provide

opportunities for future improvement. Last, but not least, summative evalua-

tion may assist and support future training and HRD investment. In today’s

competitive world, training and HRD are frequently competing with all other

functions for organizational resources. Sound summative evaluation of sys-

tematic training demonstrates the accountability of training and HRD func-

tions and supports decision making regarding future training investments.

Training and HRD professionals have been attempting to understand sum-

mative evaluation since late 1950s. Various classification systems have been

proposed to specify the functions and purposes of evaluation in systematic

training intervention. Kirkpatrick’s (1998) four-level evaluation created in

1959 was the first classification schema or taxonomy specifically for outcome

evaluation or summative evaluation as noted by a number of studies (Alliger

& Janak, 1989; Holton, 1996; Wang, Dou, & Li, 2002; Wang & Wang, 2005).

The function of the four-level evaluation was further identified as a communi-

cation tool, instead of being claimed as evaluation techniques or steps, for

training evaluation practice (Wang et al., 2002). Based on the learning domain,

training evaluation may be classified into three types: (a) cognitive: evaluating

knowledge and cognitive strategies; (b) skill-based: evaluating constructs such

as automaticity and compilation; and (c) affective: evaluating constructs such

as attitudes and motivation (Kraiger, Ford, & Salas, 1993). Swanson and

Holton (1999) also presented a comprehensive results assessment system

focused on three domains: performance (system and financial), learning

(knowledge and expertise), and perceptions (participant and stakeholder).

Training evaluation can also be classified according to time frames involved,

such as short-term or long-term impact evaluation.

Practically, the purpose of all classification systems in evaluation is to help

conceptualize and understand the nature, functions, or purposes of evaluation

from different perspectives for facilitating data collection and analysis aspects

of program evaluation. It is a matter of preference, familiarity, or convention

of practices to various classification regarding data collection and analysis. In

other words, such classification schemes will not be able to provide analytical

tools or techniques for evaluation, except for communicating purpose or focus

of evaluations. It is the training and HRD professionals’ task to determine what

data collection techniques to use and what analytical tools to choose for the

actual evaluation efforts.

Downloaded from http://adh.sagepub.com at Airlangga University on September 25, 2008

Wang, Wilcox / TRAINING EVALUATION 531

Challenge and Opportunity

It is expected that engaging in formative evaluation within the training

phases of ADDIE and taking action on the findings will improve the quality of

the training intervention. However, a sound formative evaluation result may not

necessarily be able to guarantee positive summative evaluation results, particu-

larly when summative evaluation conducted on learners returning to their per-

formance setting. Almost always, the application of learned knowledge and

expertise are intertwined with other organizational factors, such as organization

support and the application environment (Holton, 2005; Wang et al., 2002).

Summative evaluation has been experiencing difficulties and challenges in

research and practice areas of training (Wang & Wang, 2005). Most recent data

from American Society for Training and Development (ASTD) showed that

only 12.9% of the largest organizations have conducted any kind of training

impact evaluation (Sugrue & Rivera, 2005), the most important form of sum-

mative evaluation. This reveals an interesting and alarming question: If impact

(summative) evaluation, including return-on-investment (ROI) measurement,

is so important, why we still see so few organizations actually conduct such

evaluation in training reality?

Wang and Spitzer (2005) divided the evaluation evolution in training and

HRD into three stages. The first stage is practice-oriented atheoretical stage as

represented by the Kirkpatrick four-level scheme, ranging from the late 1950s

to the late 1980s. The second stage is a process-driven operational stage, rep-

resented by the ROI wave (e.g., Phillips, 2003), spanning from the late 1980s

to the early 2000s. We are now at the beginning of the third stage, the research-

oriented comprehensive stage. Recent years have witnessed a burgeoning of

evaluation methods developed by scholars and practitioners (e.g., Wang &

Spitzer, 2005), which offer training and HRD professionals more alternative

approaches and opportunities to conduct outcome evaluation.

Outcome Evaluation

Following the classification tradition initiated by Kirkpatrick (1998), this

section discusses a new perspective of classification on outcome evaluation. In

addition to demonstrating how current and previous evaluation taxonomy, the-

ories, and approaches may fit in the framework, we argue that connecting out-

come evaluation to the direction defined by the analysis phase and the

concerns of the host organization should be the focus of the evaluation.

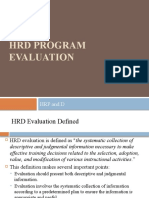

Summative evaluation at the systematic training evaluation phase can be fur-

ther detailed and classified into short-term and long-term outcome evaluation.

This classification is presented in Figure 1. In most situations, organizations

need to identify immediate training outcomes after the program implementa-

tion. Based on the four-level evaluation scheme, short-term outcome may

include participant reactions and reported or measured learning outcomes.

Downloaded from http://adh.sagepub.com at Airlangga University on September 25, 2008

532 Advances in Developing Human Resources November 2006

Reactions of

Learners

Short-Term

Outcomes

Learning by

Participants

Summative

Outcomes

Behavior

on the Job

Long-Term

Outcomes

Organizational

Impact and ROI

FIGURE 1: Framework for Summative Evaluation Phase Within Systematic Training

Note: ROI = return on investment.

Short-Term Evaluation

As a short-term evaluation, measuring participants’ perceptions and reac-

tions on training occurs during and toward the end of the implement phase. An

implicit assumption under perceptional evaluation is that the participants are

clear about their learning needs, and the needs are consistent with those iden-

tified during analysis phase. Under this assumption, if a training program fails

to satisfy the learning needs, a task for the evaluation is to identify whether it

is the responsibility of the program design or delivery. However, results from

a perceptional evaluation do not necessarily indicate what new skills and

knowledge the learners have acquired because the above assumption is not

often held true in training reality. Therefore, a more realistic way in reaction

evaluation is to obtain learners’ feedback on the interest, attention, and moti-

vation to the learning subject. These areas are critical to the success of a train-

ing program. Intuitively, participants should not have negative feelings and

reactions to training experiences.

Evaluation of learner’s reactions as a short-term training outcome is often

conducted with an attitudinal questionnaire survey with commonly used

Likert-type rating scales. Normally, the survey should cover questions in the

following areas:

• learning objectives, content and design

• instructional approaches

• learning environment and interactions.

For technology-based training, questionnaires should also include a compo-

nent on learner’s perceptions on technology usability and navigation. Regardless

Downloaded from http://adh.sagepub.com at Airlangga University on September 25, 2008

Wang, Wilcox / TRAINING EVALUATION 533

of its rationale, evaluation on reaction is the first outcome feedback that train-

ing professionals receive regarding a specific program.

Evaluation of learning outcomes is the other form of short-term evaluation.

The purpose of learning evaluation is to measure knowledge and skill enhance-

ment by the learners due to the training program participation. Consequently,

such evaluation is generally based on learning assessment and measurement

and is conducted immediately after training implementation.

Traditionally, learning evaluation has been interpreted as posttest of learn-

ing (Phillips, 1997). However, testing should not be considered the only means

of evaluating learning, especially in organizational settings where improving

performance is the ultimate goal of learning. Depending on the domain of the

subject covered by a training program, learning outcome evaluation in a train-

ing context frequently takes on formats other than knowledge testing.

Assessing expertise requires the learner to do things such as demonstration,

presentation, and hands-on projects. No matter what format one chooses to

assess learning, it should be framed by the analysis phase embedded in the

training program design process. Based on performance requirements identi-

fied during the analysis phase and learning objectives in the design phase,

trainers should create measurement instruments that fit into the learning con-

text. This fit is the core basis for evaluation of content validity.

It is critical to note that the two forms of short-term evaluation—reaction

and learning assessment as Levels 1 and 2 defined by Kirkpatrick (1998) may

not have any causal relationship in term of evaluation results. In other words,

good results from a reaction evaluation do not necessarily warrant satisfactory

learning outcomes (Alliger & Janak, 1989). However, results obtained from

reactional and learning evaluation can be used to improve and enhance the

training program in subsequent systematic training design.

Long-Term Evaluation

In organization settings, the ultimate goal for design and conducting train-

ing is to improve individual and organizational performance. The nature of

application-driven instructional design also determines the importance of

long-term evaluation. In today’s organizational reality, the “smile sheet” can

no longer represent an acceptable evaluation of training effectiveness (Moller

et al., 2000). Therefore, long-term evaluation of the impact of training

programs has received increasing attention in organizations.

Evaluation of Learning Transfer

It is important to evaluate learning transfer and behavior change because

one of the primary purposes of systematic training is to improve individual

on-the-job performance after the training. Such improvement can only be

Downloaded from http://adh.sagepub.com at Airlangga University on September 25, 2008

534 Advances in Developing Human Resources November 2006

identified when the participants apply newly learned skills and knowledge on

the performance settings. This type of evaluation is also referred to as a Level

3 evaluation according to Kirkpatrick’s classification. Because learners may

not be confronted with opportunities to demonstrate their learned knowledge

and skills immediately after a training program, evaluation of this aspect needs

to allow sufficient time for such opportunities to occur in the performance set-

tings. In practice, evaluation of knowledge and skills transfer requires a 3 to

6 months time period after a training program.

Transfer of training is defined as the degree to which learners apply the

knowledge, skills, and attitudes gained in training to their jobs (Wexley &

Latham, 1991). Transfer of training may be measured by the maintenance of

the skills, knowledge, and attitudes during a certain period of time (Baldwin

& Ford, 1988). Rouiller and Goldstein (1993) expanded the research on trans-

fer of training to include the concept of a transfer climate that either inhibits

or helps facilitate the transfer of learning into a job performance setting.

Accurately measuring transfer climate is important because it can help HRD

move beyond the question of whether training works, to analyzing why train-

ing works. Therefore, obtaining valid and reliable measures of transfer climate

will help identify not only when an organization is ready for a training inter-

vention but also when individuals, groups, and organizations are ready for such

an intervention (Holton, Bates, Seyler, & Carvalho, 1997).

Holton, Bates, and Ruona (2000) further extended transfer climate to a

learning transfer system. This system is defined as all factors in the person,

training, and organization that influence transfer of learning to job perfor-

mance. That study argued that transfer climate is only one subset of factors

that influences learning transfer. Other influences on transfer may include

training design, personal characteristics, opportunity to use training, and

motivational influences. Transfer can only be completely understood and

influenced by examining the entire system of influences (Holton, 2005). It is

also a requirement for learning transfer to take place on the job. Thus, to

effectively measure the learning transfer climate and potential subsequent

behavioral change, Holton and colleagues (Holton et al., 1997; Holton et al.,

2000) posited and validated the following variables in a proposed learning

transfer system inventory (LTSI): learner readiness, motivation to transfer,

positive and/or negative personal outcomes, personal capacity for transfer,

peer and supervisor support, supervisor sanctions, transfer design, and oppor-

tunity to use.

LTSI as a latest development in measuring training outcomes takes into

consideration of all influencing organization variables and constructs bearing

on the transfer of learning to workplace behaviors. It clearly points to a future

direction for enhancing learning transfer and behavior change after a training

program at a longer term. Without considering the variables as defined in the

above LTSI, it is difficult to effectively enhance the transfer process and close

the performance gap identified in the analysis phase of systematic training.

Downloaded from http://adh.sagepub.com at Airlangga University on September 25, 2008

Wang, Wilcox / TRAINING EVALUATION 535

Frequently, direct observations and assessment of actual workplace behaviors

is also required to confirm actual transfer.

Evaluation of Organizational Impact

As an important form of long-term evaluation, measuring the impact of train-

ing on organizational results poses unique problems. Traditional ADDIE models

start with the assumption that training is needed and moves on to systematically

create and deliver that requested training. In almost all cases, the core analysis

as to what the organizational problem or goal was, and what it would truly take

to make the desired gains, is outside the traditional ADDIE process. In this com-

mon scenario, Wang and Wang (2005) observed that the complexity and diffi-

culty is caused by the fact that such evaluation is to analyze the impact of a

training subsystem on an organizational overall system. Given the multiple sub-

systems coexisting and intertwining with each other in any organizational

system, many view measurement of training programs’ organizational results or

ROI of training a thorny task, if not impossible. However, to demonstrate the

contribution of systematic training to overall organizational performance, it has

become a requirement to conduct impact evaluation in many organizations.

Occasionally, ROI formula may be applied to the evaluation settings as rec-

ommended by Phillips (1997). The formula is expressed as ROI = Net

Benefit/Total Cost × 100%. The application of the ROI calculation, however, is

subject to one restriction: A valid and reliable measure of the training program’s

net benefit (Net Program Benefit = Total Program Benefit – Total Program

Cost) is readily available. Yet in training reality, the net program benefit is often

entangled with other organizational system variables and difficult to separate,

although the term of total program cost may be easily obtainable. In fact, if one

can calculate the net benefit for a training program, it may become unnecessary

to determine the ROI because the net benefit is the organizational impact of

training, or the contribution that a training program makes for the organization.

Control groups were recommended by Wang (2002) for identifying the net

benefit of a training program. Wang (2002) defined four types of control

groups based on experimental design methodology. While Type I control

group serves as a benchmark to gauge the validity and reliability of the mea-

surement, Type II control group can be used for two or more groups’ compar-

ison on training program benefit. Type III control group is a time-series

measurement, with one physical group, that treats the training group as the

control of its own. Meanwhile, Type IV control group setting is a combination

of Type II and Type III which can be used for more complex measurement sce-

narios for obtaining the benefit information generated by training programs.

When more sophisticated ADDIE processes are applied over traditional

ADDIE models, the up-front analyst takes off his or her training hat and puts

on a performance improvement hat (Rummler & Brache, 1995; Swanson,

Downloaded from http://adh.sagepub.com at Airlangga University on September 25, 2008

536 Advances in Developing Human Resources November 2006

1996). When this happens, the analysis will focus on mission-related outputs

of the organization. Performance goals related to outputs of the goods or ser-

vices produced by the organization will almost always require an intervention

that goes beyond training so as to consider all the elements required to assure

performance improvement. After performance shortcomings are identified,

and complete interventions are assessed to be at the root of improvement, the

resulting gains in units of work productivity, and their conversion to financial

benefits, are quite easy (Swanson, 2001).

Nonfinancial Alternatives

At the beginning of the new measurement and evaluation stage, the

research-oriented comprehensive stage as defined by Wang and Spitzer (2005),

recent years have witnessed more summative evaluation approaches focusing

on measuring organizational impact of training interventions. Several studies

advocate systems thinking for conducting the impact measurement in organi-

zations (e.g., Russ-Eft & Preskill, 2005; Wang & Wang, 2005). Such analyses

consider the complexity of evaluation within an organizational systems con-

text, and indicate that in training impact analysis one needs to consider what

impact other organizational system variables may have on the outcome mea-

sure to effectively answer the organization’s evaluative questions. Through

case studies, Russ-Eft and Preskill (2005) demonstrated the application of a

systems approach to measuring organizational impact of training programs

qualitatively. That study showed that determining ROI is a multifaceted and

complicated task within a complex system. Many of the measurement requests

for ROI tend to be “knee-jerk” reactions, based on a lack of understanding and

misconceptions about evaluation. In a similar systems framework, Wang and

Wang (2005) derived a quantitative approach to measuring quantifiable orga-

nizational outcomes generated by the training function while considering all

other factors’ contributions to the organization.

In a similar vein, Brinkerhoff (2003) further argued that evaluation of train-

ing is a whole organization strategy. Training should not be the object of eval-

uation. Instead, what is needed is evaluation of how well organizations use

training. This requires focusing evaluation inquiry on the larger process of

training as it is integrated with performance management and includes those

factors and actions that determine whether training can create performance

results. By proposing a success case method, Brinkerhoff demonstrated that

effective training impact should involve all relevant stakeholders of a training

program. Likewise, Nickols (2005) suggested a stakeholder-based approach

for measuring organizational impact of training. This approach requires train-

ing and HRD professionals to incorporate stakeholder requirements into the

design, development, and delivery of training, increasing stakeholder interest

in the outcomes and in evaluating those outcomes in ways that offer meaning

Downloaded from http://adh.sagepub.com at Airlangga University on September 25, 2008

Wang, Wilcox / TRAINING EVALUATION 537

and value to all the stakeholders. Other latest methodological development of

organizational impact for training programs also includes learning effective-

ness measurement approach that focuses on the relationship between training

and business causal chain (Spitzer, 2005), and critical outcome technique that

concentrates on result-oriented program evaluation (Mattson, 2005).

No matter what methods are used in obtaining the information on training

benefit regarding organizational impact, key metrics in three areas are almost

always appealing to decision makers and may be effectively measured for

training’s impact. They are time, quality, and cost, as directly related to business

principle of “faster, better, and cheaper.” All the three areas of metrics are pro-

ductivity driven. Although other more directive metrics, such as sales revenue or

profitability, may be more attractive, given the multiple factors involved and the

difficulties in separating training program effects, we do not recommend directly

measuring such impact. In other words, if a training program, through a sys-

tematic ADDIE process, can generate results that save an organization time in

delivering their product and services, or improve product or service quality, or

reduce the cost, it will certainly receive more organizational support and invest-

ment. In measurement reality, the three areas of key metrics should be further

specified at different levels according to particular measurement situations and

requirements. For instance, time-related metrics may include project cycle time,

facility downtime, time to market, and time to delivery; quality-related metrics

may include defect rate, unscheduled maintenance, and customer and/or stake-

holder satisfaction rate; and cost-related metrics may include cost reduction in

any specific area. In short, measuring organizational impact of training is to

identify specific metrics that an organization values and translate the training

impact into quantifiable organizational outcomes with credible methods.

Concluding Remark

When reviewing the theory and practice within the evaluation realm of sys-

tematic training, the training profession should know more than it is practic-

ing. With increasingly available approaches and models for conducting

training outcome and impact evaluation, a core challenge to the profession is

to know the right approaches and techniques for specific evaluation needs and

the concerns of the host organization. Furthermore, having measurement skills

related to creating valid and reliable instruments is also critical to produce

credible evaluation results.

References

Alliger, G. M., & Janak, E. A. (1989). Kirkpatrick’s levels of criteria: Thirty years later.

Personnel Psychology, 42, 331-341.

Alvarez, K., Salas, E., & Garofano, C. M. (2004). An integrated model of training eval-

uation and effectiveness. Human Resource Development Review, 3(4), 385-416.

Downloaded from http://adh.sagepub.com at Airlangga University on September 25, 2008

538 Advances in Developing Human Resources November 2006

Baldwin, T. T., & Ford, J. K. (1988). Transfer of training: A review and directions for

future research, Personnel Psychology, 41, 63-105.

Brinkerhoff, R. O. (2003). The success case method. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Brown, K. G., & Gerhardt, M. W. (2002). Formative evaluation: An integrative practice

model and case study. Personnel Psychology, 55, 951-983.

Desimone, R. L., Werner, J. M., & Harris, D. M. (2002). Human resource development.

Cincinnati, OH: South-Western.

Hannum, W., & Hansen, C. (1989). Instructional systems development in large organi-

zations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Holton, E. F., III. (1996). The flawed four level evaluation model. Human Resource

Development Quarterly, 7, 5-21.

Holton, E. F., III. (2005). Holton’s evaluation model: New evidence and construct elab-

orations. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 7(1), 37-54.

Holton, E. F., III, Bates, R. A., & Ruona, W. E. A. (2000). Development of a general-

ized learning transfer system inventory. Human Resource Development Quarterly,

11(4), 333-360.

Holton, E. F., III, Bates, R., Seyler, D., & Carvalho, M. (1997). Toward a construct val-

idation of a transfer climate instrument. Human Resource Development Quarterly,

8(2), 95–113.

Kirkpatrick, D. (1998). Evaluating training programs: The four levels (2nd ed.). San

Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Kraiger, K., Ford, J. K., & Salas, E. (1993). Application of cognitive, skill-based, and

affective theories of learning outcomes to new methods of training evaluation.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 311-328.

Mattson, B. W. (2005). Using the critical outcome techniques to demonstrate financial

and organizational performance results. Advances in Developing Human Resources,

7(1), 102-120.

Moller, L., Benscoter, B., & Rohrer-Murphy, L. (2000). Utilizing performance tech-

nology to improve evaluative practices of instructional designers. Performance

Improvement Quarterly, 13(1), 84-95.

Moller, L., & Mallin, P. (1996). Evaluation practices of instructional designers and orga-

nizational support or barriers. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 9(4), 82-92.

Nickols, F. W. (2005). Why a stakeholder approach to evaluating training? Advances in

Developing Human Resources, 7(1), 121-134.

Noe, R. (2002). Employee training and development (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Phillips, J. (1997). Handbook of training evaluation and measurement methods (3rd

ed.). Houston, TX: Gulf.

Phillips, J. (2003). Return on investment in training and performance improvement

programs (2nd ed.). Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Rouiller, J. Z., & Goldstein, I. L. (1993). The relationship between organizational trans-

fer climate and positive transfer of training. Human Resource Development

Quarterly, 4(4), 95-113.

Rummler, G. A., & Brache, A. P. (1995). Improving performance: How to manage the

white space on the organization chart (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Russ-Eft, D., & Preskill, H. (2005). In search of the holy grail: Return on investment

evaluation in human resource development. Advances in Developing Human

Resources, 7(1), 71-85.

Scriven, M. (1991). Evaluation thesaurus (4th ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Downloaded from http://adh.sagepub.com at Airlangga University on September 25, 2008

Wang, Wilcox / TRAINING EVALUATION 539

Scriven, M. (1996). Types of evaluation and types of evaluator. Evaluation Practice,

17(2), 151-161.

Spitzer, D. R. (1999). Embracing evaluation. Training, 36(6), 42-47.

Spitzer, D. R. (2005). Learning effectiveness: A new approach for measuring and man-

aging learning to achieve business results. Advances in Developing Human

Resources, 7(1), 55-70.

Sugrue, B., & Rivera, R. J. (2005). 2005 state of the industry: ASTD annual review of

trends in workplace learning and performance. Alexandra, VA: American Society

for Training and Development.

Swanson, R. A. (1996). Analysis for improving performance: Tools for diagnosing

organizations and documenting workplace expertise. San Francisco: Berrett-

Koehler.

Swanson, R. A. (2001). Assessing the financial benefits of human resource develop-

ment. Cambridge, MA: Perseus.

Swanson, R. A. (2005). Evaluation, a state of mind. Advances in Developing Human

Resources, 7(1), 16-21.

Swanson, R. A., & Holton, E. F. (1999). Results: How to assess performance, learning,

and perceptions in organizations. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Wang, G. (2002). Control groups for human performance technology (HPT) evaluation

and measurement. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 15(2), 34-48.

Wang, G., Dou, Z., & Li, N. (2002). A systems approach to measuring return on invest-

ment for HRD programs. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 13(2), 203-224.

Wang, G. G., & Spitzer, D. R. (2005). HRD measurement & evaluation: Looking back

and moving forward. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 7(1), 5-15.

Wang, G. G., & Wang, J. (2005). HRD evaluation: Emerging market, barriers, and

theory building. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 7(1), 22-36.

Wexley, K. R., & Latham, G. P. (1991). Developing and training human resources in

organizations. New York: HarperCollins.

Greg G. Wang is associate professor of human resource development (HRD) at Old

Dominion University. His research focus has been on economic foundation of HRD,

evaluation and measurement, e-learning interventions, and international HRD.

Formerly with GE, Motorola, and Pennsylvania Power & Light, he is also actively

involved in HRD practice. He has consulted with IBM, GE, Hewlett Packard, and other

major corporations. He is the founder and moderator of the Internet forum, ROInet,

with more than 2,300 researchers and practitioners from more than 40 countries.

Diane Wilcox is an assistant professor of human resource development (HRD) at

James Madison University where she teaches HRD, instructional technology, and adult

learning. Her research interests include the use of innovative technologies in training,

performance assessment, and evaluation. She has 15 years of HRD practitioner experience

and earned her PhD at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in educational

psychology.

Wang, G. G., & Wilcox, D. (2006). Training evaluation: Knowing more than is practiced.

Advances in Developing Human Resources, 8(4), 528-539.

Downloaded from http://adh.sagepub.com at Airlangga University on September 25, 2008

You might also like

- Phrasebank ManchesterDocument19 pagesPhrasebank ManchesterHarold QuilangNo ratings yet

- Letter of Recommendation: Please Type Neatly. To Be Filled by The ApplicantDocument2 pagesLetter of Recommendation: Please Type Neatly. To Be Filled by The ApplicantTresna Maulana100% (2)

- Training Effectiveness Measurement for Large Scale Programs: Demystified!From EverandTraining Effectiveness Measurement for Large Scale Programs: Demystified!No ratings yet

- Level 6 Diploma - Unit 3 Assignment Guidance - April 2015Document10 pagesLevel 6 Diploma - Unit 3 Assignment Guidance - April 2015Jaijeev PaliNo ratings yet

- Q059 Wang 2006Document12 pagesQ059 Wang 2006Heinz PeterNo ratings yet

- Training EvaluationDocument12 pagesTraining EvaluationRana ShakoorNo ratings yet

- HRD Program Evaluation CH 9Document31 pagesHRD Program Evaluation CH 9Tesfaye KebedeNo ratings yet

- Literaturereview TperezDocument16 pagesLiteraturereview Tperezapi-705656960No ratings yet

- HRD CHP 7Document34 pagesHRD CHP 7kamaruljamil4No ratings yet

- Team D Program Evaluation Training MaterialDocument11 pagesTeam D Program Evaluation Training Materialapi-367023602No ratings yet

- Evaluation of Training Programmes: BackgroundDocument7 pagesEvaluation of Training Programmes: BackgroundUpadhayayAnkurNo ratings yet

- Case Study Application of Dmaic To Academic Assessment in Higher EducationDocument10 pagesCase Study Application of Dmaic To Academic Assessment in Higher EducationAmir ShahzadNo ratings yet

- hrd-3 NewDocument18 pageshrd-3 Newjeevangowdas476No ratings yet

- Tutorial HRM 549 Chapter 1Document4 pagesTutorial HRM 549 Chapter 1Shira EjatNo ratings yet

- Training & Development - 1525Document9 pagesTraining & Development - 1525Durjoy SharmaNo ratings yet

- Methods of Training Programmes Evaluation: A Review: April 2014Document13 pagesMethods of Training Programmes Evaluation: A Review: April 2014AnkitaNo ratings yet

- Discussion 5Document4 pagesDiscussion 5Nordia Black-BrownNo ratings yet

- Assignment Iee& GG: Submitted By: Obaid KhurshidDocument3 pagesAssignment Iee& GG: Submitted By: Obaid KhurshidObaid Khurshid MughalNo ratings yet

- How To Evaluate Your Faculty Development Services - Academic Briefing - Higher Ed Administrative LeadershipDocument10 pagesHow To Evaluate Your Faculty Development Services - Academic Briefing - Higher Ed Administrative LeadershipSherein ShalabyNo ratings yet

- Training and DDocument8 pagesTraining and DAkshay BadheNo ratings yet

- CIPP Evaluation ModelDocument6 pagesCIPP Evaluation ModelReynalyn GozunNo ratings yet

- Addie ModeelDocument4 pagesAddie ModeelSaira AzizNo ratings yet

- Training and Development (CHAPTER 6)Document8 pagesTraining and Development (CHAPTER 6)JaneaNo ratings yet

- Training ModelDocument8 pagesTraining ModelSyful An-nuarNo ratings yet

- Dissertation DraftDocument49 pagesDissertation DraftKrithika YagneshwaranNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Training - Beyond Reaction EvaluationDocument18 pagesEvaluating Training - Beyond Reaction Evaluationpooja_patnaik237No ratings yet

- Evaluation of Training and Development: An Analysis of Various ModelsDocument7 pagesEvaluation of Training and Development: An Analysis of Various Modelsdharshn12345No ratings yet

- Dissertation ReportDocument99 pagesDissertation Reportvidhuarora1840100% (1)

- Florence P. Querubin Report in Evaluation of S&T EducationDocument15 pagesFlorence P. Querubin Report in Evaluation of S&T EducationFlorence QuerubinNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Various Training Evaluation ModelsDocument9 pagesAn Analysis of Various Training Evaluation ModelsRanaa hannaNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Various Training Evaluation ModelsDocument9 pagesAn Analysis of Various Training Evaluation ModelsRajeshNo ratings yet

- A Literature Review On Various Models For Evaluating Training ProgramsDocument9 pagesA Literature Review On Various Models For Evaluating Training ProgramsKacang BakarNo ratings yet

- Training EffectivenessDocument10 pagesTraining EffectivenessdeepmaniaNo ratings yet

- Study of Training and Development: Audit and Evaluation Division March 2002Document26 pagesStudy of Training and Development: Audit and Evaluation Division March 2002Irene Joy ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Final LR 1Document8 pagesFinal LR 1mansi trivediNo ratings yet

- 5068 Preskill Chapter 5Document80 pages5068 Preskill Chapter 5pj501No ratings yet

- The Application Strategic Planning and Balance Scorecard Modelling in Enhance of Higher EducationDocument5 pagesThe Application Strategic Planning and Balance Scorecard Modelling in Enhance of Higher Educationc1rkeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 - Training EvaluationDocument28 pagesChapter 6 - Training EvaluationChaudry AdeelNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Evaluation of TrainingDocument9 pagesApproaches To Evaluation of Trainingdhavalchothani1616No ratings yet

- Principles and Processes in Coaching Evaluation: Degray School of Management, University of SurreyDocument15 pagesPrinciples and Processes in Coaching Evaluation: Degray School of Management, University of SurreyReiki TerapiasNo ratings yet

- Training Programme Evaluation: Training and Learning Evaluation, Feedback Forms, Action Plans and Follow-UpDocument14 pagesTraining Programme Evaluation: Training and Learning Evaluation, Feedback Forms, Action Plans and Follow-UpDiana Vivisur100% (1)

- Training Evaluation: 6 Edition Raymond A. NoeDocument28 pagesTraining Evaluation: 6 Edition Raymond A. Noepanthoh1No ratings yet

- Operational DefinitionsDocument4 pagesOperational DefinitionsTomika RodriguezNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of Evaluation Practice: The Kirkpatrick Model and The Principle of BeneficenceDocument8 pagesA Critical Analysis of Evaluation Practice: The Kirkpatrick Model and The Principle of BeneficenceDedet TriwahyudiNo ratings yet

- Training and Development Program FinalDocument27 pagesTraining and Development Program FinalRahil KhanNo ratings yet

- Douglah. Concept of Program EvaluationDocument0 pagesDouglah. Concept of Program EvaluationThelma Pineda GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Section 4:: Evaluation of Professional DevelopmentDocument16 pagesSection 4:: Evaluation of Professional DevelopmentMaria RicNo ratings yet

- HRM - C - 5 HRD Done + BestDocument21 pagesHRM - C - 5 HRD Done + BestAbraham BizualemNo ratings yet

- Unit 13: Training: ObjectivesDocument30 pagesUnit 13: Training: Objectivesg24uallNo ratings yet

- Creating Training and Development Programs: Using The ADDIE MethodDocument5 pagesCreating Training and Development Programs: Using The ADDIE MethodYayan NadzriNo ratings yet

- Rana G PDFDocument7 pagesRana G PDFAbdul MajidNo ratings yet

- Models of TrainingDocument6 pagesModels of TrainingNishita Jain100% (1)

- Evaluating Learning Develop - 20221129T122816Document8 pagesEvaluating Learning Develop - 20221129T122816Sanja KutanoskaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation ModelDocument7 pagesEvaluation ModelHumaizah MaiNo ratings yet

- IJBGM - Evaluation of Training Effectiveness Based On Reaction A Case StudyDocument12 pagesIJBGM - Evaluation of Training Effectiveness Based On Reaction A Case Studyiaset123No ratings yet

- THE IMPACT STUDY ON EFFECTIVENESS OF AKEPT'S T& L TRAINING PROGRAMMESDocument86 pagesTHE IMPACT STUDY ON EFFECTIVENESS OF AKEPT'S T& L TRAINING PROGRAMMEShanipahhussinNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Training Evaluation: StructureDocument15 pagesUnit 2 Training Evaluation: StructurevinothvinozonsNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of Evaluation Practice: The Kirkpatrick Model and The Principle of BeneficenceDocument8 pagesA Critical Analysis of Evaluation Practice: The Kirkpatrick Model and The Principle of BeneficenceMru KarNo ratings yet

- Chapter VI: Recommendations and ConclusionsDocument34 pagesChapter VI: Recommendations and ConclusionsSrini VasNo ratings yet

- Riccard Multigenerational Tiered AssessmentDocument9 pagesRiccard Multigenerational Tiered Assessmentapi-519873112No ratings yet

- Allen, W. (N.D) - Selecting Evaluation Questions and TypesDocument6 pagesAllen, W. (N.D) - Selecting Evaluation Questions and Typesken macNo ratings yet

- The Value of Learning: How Organizations Capture Value and ROI and Translate It into Support, Improvement, and FundsFrom EverandThe Value of Learning: How Organizations Capture Value and ROI and Translate It into Support, Improvement, and FundsNo ratings yet

- Q1 G7 Worksheet Direct and Reported SpeechDocument5 pagesQ1 G7 Worksheet Direct and Reported SpeechQueeny Abiera TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Nouns Regular and IrregularDocument9 pagesNouns Regular and Irregularkenken2No ratings yet

- B.Sc. Paramedical Sciences Selection List 6: Fee Details Head FeeDocument2 pagesB.Sc. Paramedical Sciences Selection List 6: Fee Details Head FeeLex LexiconNo ratings yet

- 1.1 Definitions and Classifications Building MaterialsDocument7 pages1.1 Definitions and Classifications Building Materialsjack.simpson.changNo ratings yet

- B. Sample Annotated Bibliography Dr. Alvin S. SicatDocument6 pagesB. Sample Annotated Bibliography Dr. Alvin S. SicatJeremy James AlbayNo ratings yet

- December Gasetan Guihan Newsletter 2019Document4 pagesDecember Gasetan Guihan Newsletter 2019api-250691083No ratings yet

- Needs Analysis Questionnaire - EnglishDocument8 pagesNeeds Analysis Questionnaire - EnglishBeatrice BacalbasaNo ratings yet

- Industrial Training Presentation Evaluation Form - Industry SVDocument3 pagesIndustrial Training Presentation Evaluation Form - Industry SVazlanazmanNo ratings yet

- Dayton Christian School System: 9391 Washington Church Road Miamisburg, OH 45342 Phone: 937.291.7201Document7 pagesDayton Christian School System: 9391 Washington Church Road Miamisburg, OH 45342 Phone: 937.291.7201bdavis9474No ratings yet

- A Career in Accounting Tips On How You Can Be SuccessfulDocument2 pagesA Career in Accounting Tips On How You Can Be SuccessfulCarlos DNo ratings yet

- Case Study Updated TAPF Food Security 27022019 ReviewedDocument17 pagesCase Study Updated TAPF Food Security 27022019 Reviewedguptha mukthaNo ratings yet

- Punctuation Marks Lesson Plan by Patricia Leigh GonzalesDocument2 pagesPunctuation Marks Lesson Plan by Patricia Leigh GonzalesPatricia Leigh GonzalesNo ratings yet

- 4 Managerial EconomicsDocument8 pages4 Managerial EconomicsBoSs GamingNo ratings yet

- DLL Week 3Document5 pagesDLL Week 3Maye S. AranetaNo ratings yet

- Introductory Message: Welcome Dear Marians To School Year 2020-2021!Document17 pagesIntroductory Message: Welcome Dear Marians To School Year 2020-2021!Medelyn Butron PepitoNo ratings yet

- Ajay Rana: ObjectiveDocument3 pagesAjay Rana: ObjectiveManish KumarNo ratings yet

- AdmissionsResumeTemplate - RotmanDocument1 pageAdmissionsResumeTemplate - RotmanAlan0% (1)

- Education in Egypt: Conversation 1Document12 pagesEducation in Egypt: Conversation 1Mahmoud Nady Zakria Sadek SadekNo ratings yet

- 2AC K BlocksDocument165 pages2AC K BlocksBrody Diehn100% (1)

- ADHD-converted-converted-converted 2Document23 pagesADHD-converted-converted-converted 2ROSHANI YADAVNo ratings yet

- Community Organizing: Addams and AlinskyDocument40 pagesCommunity Organizing: Addams and AlinskymaadamaNo ratings yet

- Wandering by Sarah Jane CervenakDocument34 pagesWandering by Sarah Jane CervenakDuke University Press100% (3)

- .. To Officially Announce That You Have Decided To Leave Your Job or An Organization QuitDocument25 pages.. To Officially Announce That You Have Decided To Leave Your Job or An Organization QuitLê Nguyễn Bảo DuyNo ratings yet

- DL Archaeology and Ancient HistoryDocument28 pagesDL Archaeology and Ancient HistoryDaniel Barbo LulaNo ratings yet

- Punjab University College of Information Technology (Pucit) : Database Systems Lab 2Document2 pagesPunjab University College of Information Technology (Pucit) : Database Systems Lab 2Lyeba AjmalNo ratings yet

- Visa Interview-F1 - USDocument7 pagesVisa Interview-F1 - USOPDSS SRINIVASNo ratings yet

- Edu 533/535-Assessment of Learning: Palasol, Kenneth T. A-COE-08 Bsed - Fil. Iv EDU 259Document6 pagesEdu 533/535-Assessment of Learning: Palasol, Kenneth T. A-COE-08 Bsed - Fil. Iv EDU 259Mike Angelo Gare PitoNo ratings yet