Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Preservatin of Historic Arch and Beliefs of The Moder Movement in Mexico

The Preservatin of Historic Arch and Beliefs of The Moder Movement in Mexico

Uploaded by

ana paula ruiz galindoCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Koontz Visual Culture StudiesDocument5 pagesKoontz Visual Culture StudiesJanaMuseologiaNo ratings yet

- Mexican MuralismDocument6 pagesMexican Muralismrsbasu0% (1)

- Studio GBL - 2016 - Texte - A G - H Frampton - 2015 - S 6-17Document19 pagesStudio GBL - 2016 - Texte - A G - H Frampton - 2015 - S 6-17Nikola Kovacevic100% (1)

- How To Access The Akashic RecordsDocument8 pagesHow To Access The Akashic Recordsthanesh singhNo ratings yet

- The American Places of Charles W. MooreDocument10 pagesThe American Places of Charles W. MooreValentín Martínez, ArquitectoNo ratings yet

- Giedion, Sert, Leger: Nine Points On MonumentalityDocument5 pagesGiedion, Sert, Leger: Nine Points On MonumentalityManuel CirauquiNo ratings yet

- EstridentópolisDocument27 pagesEstridentópolisArt DNo ratings yet

- Architecture of The 40sDocument21 pagesArchitecture of The 40sScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- MuralPaintinginMexicoandtheUSA EvaZettermanDocument17 pagesMuralPaintinginMexicoandtheUSA EvaZettermanSenad BegovicNo ratings yet

- Beyond Tlatelolco Design Media and Polit PDFDocument27 pagesBeyond Tlatelolco Design Media and Polit PDFeisraNo ratings yet

- CASTEÑEDA. Beyond TlatelolcoDocument28 pagesCASTEÑEDA. Beyond TlatelolcoRoberta PlantNo ratings yet

- Moteuczoma Reborn: Biombo Paintings and Collective Memory in Colonial Mexico CityDocument17 pagesMoteuczoma Reborn: Biombo Paintings and Collective Memory in Colonial Mexico CityPriya SeshadriNo ratings yet

- Juan Ogorman Vs The International StyleDocument7 pagesJuan Ogorman Vs The International StyleMaria JoãoNo ratings yet

- Architectural Culture in The Fifties: Louis Kahn and The National Assembly Complex in DhakaDocument20 pagesArchitectural Culture in The Fifties: Louis Kahn and The National Assembly Complex in DhakaSomya InaniNo ratings yet

- American Junkspace: The Discourse of Contemporary American ArchitectureDocument9 pagesAmerican Junkspace: The Discourse of Contemporary American ArchitectureEzequiel VillalbaNo ratings yet

- Identify and Analyse The Political Ideals Present in One Major Work of Mexican Muralist ArtDocument9 pagesIdentify and Analyse The Political Ideals Present in One Major Work of Mexican Muralist ArtalejandraNo ratings yet

- Laa Bibliography PDFDocument18 pagesLaa Bibliography PDFPablo Muñoz PonzoNo ratings yet

- Condesa TópicoDocument5 pagesCondesa TópicoMarcelo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Unit Ii: History of Architecture & Culture - ViDocument51 pagesUnit Ii: History of Architecture & Culture - ViPrarthana roy RNo ratings yet

- MuralismDocument3 pagesMuralismCarolina RoblesNo ratings yet

- The Vernacular Between Theory and practice-C.Machat PDFDocument14 pagesThe Vernacular Between Theory and practice-C.Machat PDFAlin TRANCUNo ratings yet

- Iafor: Writing of The History: Ernesto Rogers Between Estrangement and Familiarity of Architectural HistoryDocument12 pagesIafor: Writing of The History: Ernesto Rogers Between Estrangement and Familiarity of Architectural HistoryF Andrés VinascoNo ratings yet

- Unit I: History of Architecture & Culture - ViDocument44 pagesUnit I: History of Architecture & Culture - ViPrarthana roy RNo ratings yet

- 2017 Articulo Classical Readings For Chi PDFDocument10 pages2017 Articulo Classical Readings For Chi PDFDiego IcazaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 170.239.168.67 On Tue, 23 Mar 2021 19:59:42 UTCDocument30 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 170.239.168.67 On Tue, 23 Mar 2021 19:59:42 UTCAgus DemNo ratings yet

- Review Essay: Mexico: Biography of Power by Enrique Krauze. Translated by HankDocument14 pagesReview Essay: Mexico: Biography of Power by Enrique Krauze. Translated by HankLuis Rubén Hernández GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- The Fate of Mesopotamian Architecture inDocument13 pagesThe Fate of Mesopotamian Architecture inMuhammad BrohiNo ratings yet

- C Ssic S: The Ultu F Ti D RN Arch Te Ur R Manti Mandre Teqreuon B TweenDocument1 pageC Ssic S: The Ultu F Ti D RN Arch Te Ur R Manti Mandre Teqreuon B TweenGil EdgarNo ratings yet

- Re Reading The EncyclopediaDocument10 pagesRe Reading The Encyclopediaweareyoung5833No ratings yet

- 2018 4 1 2 MagalhaesDocument22 pages2018 4 1 2 MagalhaesSome445GuyNo ratings yet

- Cosentino, A Cartographic ReckoningDocument16 pagesCosentino, A Cartographic ReckoningEfren SandovalNo ratings yet

- BTC 3 2011Document5 pagesBTC 3 2011Dl DodhedNo ratings yet

- Mexican MuralismDocument3 pagesMexican MuralismNatalia ChillemiNo ratings yet

- Ch'u MayaaDocument14 pagesCh'u MayaaJesse LernerNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Arts Week 56Document3 pagesContemporary Arts Week 56jayveenalsoclaritNo ratings yet

- LECTURA 7 - CarpoDocument12 pagesLECTURA 7 - CarpofNo ratings yet

- Forging A Popular Art HistoryDocument17 pagesForging A Popular Art HistoryGreta Manrique GandolfoNo ratings yet

- A Nationalist Metaphysics: State Fixations, National Maps, and The Geo-Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century MexicoDocument36 pagesA Nationalist Metaphysics: State Fixations, National Maps, and The Geo-Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century MexicoRene ToapantaNo ratings yet

- Post War Philippines ArchitectureDocument10 pagesPost War Philippines ArchitectureElaiza FuentesNo ratings yet

- DDocument14 pagesDapi-706911799No ratings yet

- Noguchi in MexicoDocument25 pagesNoguchi in MexicoMario MonterrosoNo ratings yet

- Brulon Soares-The Myths of MuseologyDocument19 pagesBrulon Soares-The Myths of MuseologyflorenciacolomboNo ratings yet

- Theory of Architecture (Toa) : Name SRNDocument28 pagesTheory of Architecture (Toa) : Name SRNDhanush KeshavNo ratings yet

- Modern Mexico CityDocument61 pagesModern Mexico CityPriya SeshadriNo ratings yet

- Blier, S. Vernacular ArchitectureDocument24 pagesBlier, S. Vernacular ArchitecturemagwanwanNo ratings yet

- El Elogio de Las OllasDocument21 pagesEl Elogio de Las OllasDeborah DorotinskyNo ratings yet

- Critical Fortune of Brazilian Modern Architecture 1943-1955Document20 pagesCritical Fortune of Brazilian Modern Architecture 1943-1955Luca Luini100% (1)

- ARTICULO PALLINI - Schools and Museums in Greece PDFDocument13 pagesARTICULO PALLINI - Schools and Museums in Greece PDFIsabel Llanos ChaparroNo ratings yet

- 05-Art - Folklore - and Industry - Popular Arts and Indigenismo in Mexico - 1920 - 1946Document25 pages05-Art - Folklore - and Industry - Popular Arts and Indigenismo in Mexico - 1920 - 1946Anamaria Garzon MantillaNo ratings yet

- From The Screen To The Wall Siqueiros and EisensteinDocument26 pagesFrom The Screen To The Wall Siqueiros and EisensteinPazuzu8No ratings yet

- Rural and Urban Schools: Northern Greece in The Interwar PeriodDocument10 pagesRural and Urban Schools: Northern Greece in The Interwar PeriodAleksandar AšaninNo ratings yet

- Codex AzcatitlanDocument17 pagesCodex AzcatitlanCarlos Quintero MunguíaNo ratings yet

- Neo Baroque CodexDocument19 pagesNeo Baroque CodexAnonymous iGdPMJwKNo ratings yet

- J. B. 杰克逊和景观设计师-劳里-奥林-2020Document5 pagesJ. B. 杰克逊和景观设计师-劳里-奥林-20201018439332No ratings yet

- Troubles in Theory I - The State of The Art 1945-2000 - Architectural ReviewDocument12 pagesTroubles in Theory I - The State of The Art 1945-2000 - Architectural ReviewPlastic SelvesNo ratings yet

- In Progress: New Monumentality S Retrospective JustificationDocument41 pagesIn Progress: New Monumentality S Retrospective JustificationMaria Camila GonzalezNo ratings yet

- 05CURRENTNEWS IT B07-En-1Document10 pages05CURRENTNEWS IT B07-En-1Isaac TameNo ratings yet

- Society of Architectural Historians University of California PressDocument5 pagesSociety of Architectural Historians University of California Press槑雨No ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Regionalism and IdentityDocument36 pagesChapter 2 - Regionalism and IdentityAr Shahanaz JaleelNo ratings yet

- 3 HOUSES Luis Barragan - English-RoquimeDocument34 pages3 HOUSES Luis Barragan - English-RoquimeRoquime Roquime100% (1)

- Designs of Destruction: The Making of Monuments in the Twentieth CenturyFrom EverandDesigns of Destruction: The Making of Monuments in the Twentieth CenturyNo ratings yet

- Braintree 15Document6 pagesBraintree 15paypaltrexNo ratings yet

- PPE Lab ManualDocument27 pagesPPE Lab ManualDinesh Chavhan100% (1)

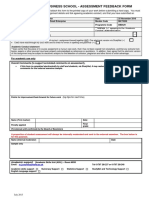

- HBS Assessment Feedback Form IndividualDocument1 pageHBS Assessment Feedback Form IndividualsarithaNo ratings yet

- JLTR, 02Document8 pagesJLTR, 02Junalyn Villegas FerbesNo ratings yet

- Pac CarbonDocument172 pagesPac CarbonBob MackinNo ratings yet

- Nature of Bivariate DataDocument39 pagesNature of Bivariate DataRossel Jane CampilloNo ratings yet

- Financial Summary Statement Period 03/10/23 - 04/09/23: Deposit Accounts Total DepositsDocument14 pagesFinancial Summary Statement Period 03/10/23 - 04/09/23: Deposit Accounts Total DepositsLuis RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Actuator-Sensor-Interface: I/O Modules For Operation in The Control Cabinet (IP 20)Document22 pagesActuator-Sensor-Interface: I/O Modules For Operation in The Control Cabinet (IP 20)chochoroyNo ratings yet

- PCR AslamkhanDocument1 pagePCR AslamkhanKoteswar MandavaNo ratings yet

- XAI P T A Brief Review of ExplainableDocument9 pagesXAI P T A Brief Review of Explainableghrab MedNo ratings yet

- Research MethodologyDocument2 pagesResearch MethodologyrameshNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3. Functions and Philosophical Perspectives On Art - PDF - Philosophical Theories - EpistemologyDocument362 pagesLesson 3. Functions and Philosophical Perspectives On Art - PDF - Philosophical Theories - EpistemologyDanica Jeane CorozNo ratings yet

- Cost Justifying HRIS InvestmentsDocument19 pagesCost Justifying HRIS InvestmentsJessierene ManceraNo ratings yet

- Procedure: Administering An Intradermal Injection For Skin TestDocument3 pagesProcedure: Administering An Intradermal Injection For Skin TestSofia AmistosoNo ratings yet

- The Wild BunchDocument2 pagesThe Wild BuncharnoldNo ratings yet

- Section 2 Digital OutputDocument1 pageSection 2 Digital Outputsamim_khNo ratings yet

- Cyctocyle - Care PlanDocument22 pagesCyctocyle - Care Planarchana vermaNo ratings yet

- Imj 13707Document11 pagesImj 13707Santiago López JosueNo ratings yet

- 3 2 A UnitconversionDocument6 pages3 2 A Unitconversionapi-312626334No ratings yet

- Exterior & Interior: SectionDocument44 pagesExterior & Interior: Sectiontomallor101No ratings yet

- Water Pollution 2 (Enclosure)Document10 pagesWater Pollution 2 (Enclosure)mrlabby89No ratings yet

- A Bluetooth ModulesDocument19 pagesA Bluetooth ModulesBruno PalašekNo ratings yet

- Primary Worksheets: Frog Life CycleDocument6 pagesPrimary Worksheets: Frog Life CycleMylene Delantar AtregenioNo ratings yet

- Opsrey - Acre 1291Document97 pagesOpsrey - Acre 1291Hieronymus Sousa PintoNo ratings yet

- Pack 197 Ana Maria Popescu Case Study AnalysisDocument16 pagesPack 197 Ana Maria Popescu Case Study AnalysisBidulaNo ratings yet

- Digipay GuruDocument13 pagesDigipay GuruPeterhill100% (1)

- CS701 - Theory of Computation Assignment No.1: InstructionsDocument2 pagesCS701 - Theory of Computation Assignment No.1: InstructionsIhsanullah KhanNo ratings yet

- Topic On CC11Document3 pagesTopic On CC11Free HitNo ratings yet

The Preservatin of Historic Arch and Beliefs of The Moder Movement in Mexico

The Preservatin of Historic Arch and Beliefs of The Moder Movement in Mexico

Uploaded by

ana paula ruiz galindoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Preservatin of Historic Arch and Beliefs of The Moder Movement in Mexico

The Preservatin of Historic Arch and Beliefs of The Moder Movement in Mexico

Uploaded by

ana paula ruiz galindoCopyright:

Available Formats

The Preservation of Historic Architecture and the Beliefs of the Modern Movement in

Mexico: 1914–1963

Author(s): Enrique X. de Anda Alanís

Source: Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation, History, Theory, and

Criticism , Winter 2009, Vol. 6, No. 2 (Winter 2009), pp. 58-73

Published by: University of Minnesota Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25835064

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/25835064?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

University of Minnesota Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation, History, Theory, and Criticism

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

i. Plaza de las Tres Culturas (The Plaza of the Three Cultures), watercolor rendering. Conjunto urbano, "Presidente Lopez

Mateos" (Nonoalco-Tlatelolco), (Mexico: Banco Nacional Hipotecario Urbano y de Obras Publicas, S.A., 1963), 216.

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Enrique X. de Anda Alams

The Preservation of Historic

Architecture and the Beliefs of

the Modern Movement in Mexico:

1914-1963

This article explores the role of Mexican modernist architects

in conceiving the cultural and architectural significance of

Mexico's patrimony. The period in question spans from 1914

to 1963 and focuses on architects living in Mexico City. The

choice of the bracketing years stems from two milestone

events: in 1914, architect Federico Mariscal gave an influential

series of lectures on historic Mexican architecture; in 1963,

the Plaza de las Tres Culturas (the Plaza of Three Cultures) in

Mexico City was completed (Figure 1). The preservation of the

architecture of the previous centuries was a critical compo

nent of the intellectual battles from the 1910s onward,1 and

was to remain a cultural problem that in some cases became

an official undertaking of the Mexican state, and in other

cases merged with the ethos of the modern movement.2

Indeed, Mexican architects theorized and designed built

works that investigated the nature of the country's architec

tural patrimony well before the Mexican state issued formal

preservation legislation, which occurred only in 1938 and

1946, with the creation of government bodies charged with

the preservation of Mexican cultural heritage.3 The intellectual

foment in Mexico also predated the promulgation of the two

key international preservation agreements of the twentieth

century, the Athens Charter (1931) and the Venice Charter

(1964), which defined cultural heritage as a collective legacy

of mankind to be preserved. Most Mexican modernist archi

tects of this period, despite their adherence to the idea of a

new architecture, nevertheless followed the idea of preserving

the physical legacy of the past and its link to a wider, histori

cally contiguous notion of "Mexicanness."

Before continuing, however, the distinction between the

modern movement and the wider constellation of Mexican

architects should be made clear. Even though the first built

works of European modernism (those of Le Corbusier, Walter

Gropius, J. J. P. Oud, and others) corresponded in Mexico with

the first buildings by Jose Villagran (1925-1927) and Juan

O'Gorman (1928-1929),4 Mexican modernist architecture

Future Anterior

must be understood in the broader context of the new cultural

Volume VI, Number 2

Winter 2009 programs that were endorsed by Jose Vasconcelos,5 the

59

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

founder in 1922 of the Secretaria de Educacion Publica (Public

Education Ministry), and were later influential in the architec

tural projects of O'Gorman and Enrique Yanez among others.6

At the time, the graduates of the National School of Architec

ture (the only school of architecture at the time in Mexico) had

tended to view history based on the official high school pro

grams and linked to the idea of preservation, and it is that

influential circle of architects and theorists around which this

half-century of history of preservation in Mexico revolves.

Federico Mariscal: Motherland and National Architecture

The university lectures taught by Federico Mariscal beginning

in 1914 were critical to the establishment of new architectural

ethos toward the Mexican past in the twentieth century.

Mariscal's role in the architects guild automatically makes

him the object of special historical attention,7 and his theo

retical stance reached a wider audience with the 1915 publica

tion of his La patria y la arquitectura nacional (The Motherland

and National Architecture)8 (Figure 2). The book took as its

subject the architecture of the viceregal period in Mexico

(1521-1821) and argued that the buildings of that era in Mex

ico held equivalent architectural significance to European

buildings of the same period. With this historical finding,

Mariscal proposed that viceregal architecture was integral to

Mexican culture and, thus, a primary element of the Mexican

identity.9

Mariscal was not the first to make these observations,10

but his contribution was critical as an opponent to the demoli

tion of the architecture of that era. The most salient part of his

defense of viceregal architecture was his concept of "mother

land and nation." Although both terms are somewhat equiva

lent, "motherland" (patria) as an idea in Mariscal's work alludes

to the geography, population, and identity of the inhabitants

anchored in the past, the sum of which makes social coher

ence possible in the present. "Nation" (nacion) signifies the

notion of physical territory, connected of course to the histori

cal events that took place in those borders. Mariscal can be

called the originator of the intellectual framework with which

Mexican architects of the period established their ethos,

making them not only creators of a new architecture but also

rendering them responsible for the custody of a collective cul

tural legacy, or, as Mariscal would say, a national legacy.

Mariscal's theoretical position can be summarized in a

selection of writing from La patria y la arquitectura nacional:

love of the motherland is one of the most powerful sources

of solidarity... therefore the buildings [that stand] on the

60

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CLASIF.

ADQUIS.

FtCHA:.

PROCED.

S.

la. de Aztecas Num. 5.

La Patria y la Arquitectura Nacional.

Conferencias del Sr. 3Srq. Federico Mariscal

I.

LA CASA.

Entre los elementos que constituyen la nocion de Patria, indudablemente esta comprendi

da la casa que vivimos y las que viven nuestros parientes, nuestros amigos, los representantes de

nuestro Gobierno y todos nuestros conciudadanos. El amor a la Patria es uno de tantos podero

sos elementos de solidaridad y, por tanto, de los fundamentales para la vida del hombre como

miembro de una nacion; deben por tanto amarse los edificios del suelo en que nacimos como una

parte constitutiva de nuestra Patria. Pero para que estos edificios realmente sean nuestros, deben

ser la fiel expresion de nuestra vida, de nuestras costumbres, y estar de acuerdo con nuestro pai

saje, es decir, con nuestro suelo y nuestro clima. Los que asf sean, son los unicos que merecen ese

amor, y al mismo tiempo, son los unicos que pueden llamarse obras de arte arquitectonico na

cional.

No podn'amos destruir ninguno de los elementos que constituyen nuestra Patria, sin lasti

mar nuestro amor a ella, ni podrfamo.. tampoco cambiarlos aun cuando fuera por el solo hecho de

imitar elementos mejores de otra nacion; de igual manera, no debemos camblar ni mucho inencs

destruir, ninguno de nuestros edificiosi que merezcun el nombre de obras He arte arqritect ^iicc

nacional, pues aun cuando revelaren uWamente la vida y las costumbies ya pasadas, esas consti

tuyen nuestra tradici6n, y el verdadero amor a la Patria debe comprender el amor a nuestros an

tepasados y lo que ellos hicieron por ella y tambien el amor a los que nos siguen, que sc d pode

mos hacer patente, o por las obras que les leguemos, o por las que les trasmitamos despues de

haberlas conservado mtegramente como herencia de nuestros abuelos.

Solo puede amarse lo que se conoce bien, y como el amor a todo lo que es la Patria cons

tituye ademas un deber, estamos obligados a conocer bien cuales son esas obras de arte arquitec

tonico nacional que merece ese nombre, que constituyen una parte de nuestra Patria. Los que de

un modo especial nos hemos dedicado al Arte Arquitect6nico y hemos adquirido los conocimien

tos en nuestro propio pai's, estamos obligados mas que ninguno a darselos a conocer a todos nues

tros conciudadanos.

El Arte Arquitectonico Mexicano merece especial estudio aun comparado con el de los

otros pai'ses: es el mas importante de toda la America, y, sin embargo, muy pocos?especialmen

te Mexicanos?lo conocen bien, y menos aun lo han estudiado y dado a conocer a los demas.

iCwdl es el Arte Arquitectonico Nacional? Para contestar esta pregunta basta decir: el que

revele la vida y las costumbres mas generates durante toda la vida de Mexico como nacion.

El ciudadano mexicano actual, el que forma la mayoria de la poblacion, es el resultado de

una mezcla material, moral e intelectual de la raza espanola y de las razas aborigenes que pobla

ron el suelo mexicano. Por tanto, la arquitectura mexicana tiene que ser la que surgio y se des

arrollo durante tres siglos virreynales en los que se constituyo el mexicano que despues se ha des

arrollado en vida independiente. Esa arquitectura es la que debe sufrir todas las transformacio

nes necesarias, para revelar en los edificios actuales las modificaciones que haya sufrido de en

tonces aca la vida del mexicano, Desgraciadamente se detuvo esa evoluci6n, y por iniluencias exo

ticas?en general muy inferiores a las originales,?se ha ido perdiendo la Arquitectura Nacional;

s61o, y esto es lo mas sensible, porque se construyen edificios que podian ser los de cualquier

otro pais porque no revelan la vida mexicana, sino porque se han destrui'do y modificado barba

ramente los hermosi'simos ejemplares de nuestra arquitectura.

Aun es tiempo de hacer renacer nuestro propio Arte Arquitectonico, y para esto, estudie

mos la vida de la epoca en que surgio y se desarrollo y la vida actual y veamos c6mo coinciden

en muchos puntos y por tanto c6mo es posible aumentar esa herencia de nuestros antepasados;

pero sobre todo y, esto por lo pronto es lo fundamental, evitemos que se destruya lo que nos que

da, no pertenece a nosotros unicamente, es la herencia que tenemos obligacion de dejar a nues

tros hijos.

2. Title page of Federico Mariscal, La patria y la arquitectura nacional, 1915.

61

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ground on which we were born, a constitutive part of

our motherland, ought to be cherished ... we must not

change, much less destroy, any of buildings that de

serve the name of national architectural art... one can

only love what one knows well and, since love to all that

motherland is implies a duty, we are [in addition] com

pelled to learn what those national works of architec

tural art are.11

Mariscal in the book also put forward a thesis of cultural and

ethnic cross-breeding (mestizaje), explaining that the pres

ence of this mestizaje became the foundation for a new way of

thinking, beyond French positivism, which had been a compo

nent of the Mexican teaching programs at the end of nine

teenth century. The "Mexican citizen," Mariscal wrote, is a

"mixture of racial, moral, and intellectual material of the

Spanish race and of the races of the aborigines.. .therefore,

Mexican architecture must be what emerged and developed

from the three centuries of the viceregal period .. ."12 His intro

duction to La patria y la arquitectura nacional closes with the

forceful message: "let us impede that, that which remains

with us and belongs to us only be destroyed, since it is the

legacy that we ?by obligation ?shall leave in inheritance to

our children"13 (Figure 3).

The Institutionalization of Preservation

Mariscal's call for the preservation of Mexico's architectural

heritage was motivated by an ethics of civil responsibility.

Two decades would pass, however, before the Mexican state

made an official commitment to the preservation of the archi

tecture of the past. In January 1939, the Instituto Nacional de

Antropologfa e Historia (INAH) was founded; its first director

was archeologist Alfonso Caso, a member of the intellectual

clique that had given shape to new Mexican cultural institu

tions following the social revolution of 1910. An act of sover

eignty was implicit in the political decision to create an official

preservation body: the autonomy of the Mexican nation over

the physical record of its past, which came from all the cul

tures within the territorial boundaries that would later become

the Mexican state. INAH was charged with restoring, docu

menting, and safeguarding all material remains from both the

Mesoamerican and the Spanish viceregal periods in Mexican

history. Again, the footprints of the National University figure

large in this story: the second director of the INAH (from 1944

1956) was Ignacio Marquina, a graduate in architecture from

the National University,14 who was in charge of the research

on Mesoamerican architecture.

62

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I ki

lit4

fit9

-- W,

411

i-t

* 1 -li

3. Palacio del Conde de Jaral de

InBerrio,

1945, the Mexican state took another im

Mexico City, originally from a photo

the subject

graph in Federico Mariscal, La patria y

of preservation of goods from t

ber

la arquitectura nacional, as 31, the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Arte

published

in Pedro Ramirez Vazquez, 4000 anos

tute of Fine Arts, INBA) was established. The

de arquitectura mexicana (Mexico City:

corresponded to INAH in responsibilities bu

Sociedad de Arquitectos Mexicanos,

Colegio Nacional de Arquitectos Mexi

exclusively with Mexican artistic output afte

canos, 1956), 105.

mission was to "safeguard, promote, sponsor

strengthen all artistic forms in which the sp

expressed and defined." In order to execute i

sibilities, INBA was organized into departme

each artistic discipline, with architecture as o

63

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

presumed its "official" acceptance into the field of the fine

arts. The first director of the department was Enrique Yanez, a

modernist architect who from the 1930s onward had helped

promote European functionalist architecture in Mexico.15

Carlos Chavez, a composer and INBA's first director,

wrote that the teaching of architecture was not a charge of

INBA, but that its dissemination and promotion was, as a "con

structive criticism about important architectural problems."16

Yanez wrote in 1952 that the responsibility of the INBA was

"to divulge the artistic [architectural] output of the nation"

and that "architecture... had tried to become a national

expression in the period immediately following the armed

struggle [of 1910]."17

During the six years in which Yanez served as director of

the Architecture Department of INBA, he organized an exhibi

tion titled "Modern Mexican Architecture," in which a number

of works from 1925 to 1950 had been selected by Yanez him

self, along with a group of important architects who identified

themselves as modernists.18 However, aside from other promo

tional tasks, what is most interesting is the exhibition named

"Arquitectura Popular en Mexico" (Popular Architecture in

Mexico), which took place in the Palace of Fine Arts in 1953

and was published in a monograph.19 It is critical to underline

the significance that Yanez placed on popular or vernacular

Mexican architecture, not only as a historical matter, but also

as a cultural component whose genesis had to be explored in

order to identify any constituent elements of national identity

within it. These popular expressions were to be conserved

and studied as historical resources, which would then sub

sequently contribute to the design of modern architecture.

Yanez, who held himself as one of the most committed fun

cionalistas (as the followers of the modern movement were

known in Mexico), recognized the potential originality of pop

ular architecture as a source of inspiration that was alien to

the academy and its theoretical doctrines.

Chavez alongside Yanez expressed this view in the texts

that they both contributed to the book Arquitectura popular

de Mexico, writing that to solve the "question" of Mexican

architecture would require determining how vernacular archi

tecture could contribute to it: "Up to what point can or should

Mexican architecture be Mexican ... [before] its quality of

beautiful art as well as its national character become a prob

lem," Chavez wrote in his introduction.20 Yanez stated that

the goal of the exhibition was "to clarify whether our modern

architecture could also be considered as Mexican"21 (Figure

4). Yanez connected European theories of modern architecture

to the historical tradition of Mexican vernacular architecture:

64

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IL

Ink" t

A4,

AMF"

4. Cover, Arquitectura popular en"These acquisitions [meaning the ideas, theories, and

Mexico (Mexican Popular Architecture).

tectonic shapes coming from abroad], which in a great pa

Photography by Gabriel Garcia Maroto.

signify progress, inasmuch as they imply that which is u

sal in modern man, ought to go along with an eagerness

internal knowledge that may expose our peculiarities."2

The project of modern architecture in Mexico was ba

on the idea of permanence (and therefore of preservatio

of tradition, an attitude that was also institutional, as t

65

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

viewpoint of the official Mexican architectural body, la

Sociedad de Arquitectos Mexicanos, makes clear. In 1956,

Pedro Ramirez Vazquez, president of the guild, sponsored

and was the editor of a photo book titled 4000 anos de

arquitectura mexicana (Four thousand Years of Mexican

Architecture),23 a selection of buildings built in Mexico since

2000 bce. The book tied contemporary architecture to the

far past and showed that Mexican architects were part of a

great historical continuity: the pre-Columbian pyramids, the

churches of the viceregal period, and the present all formed

one unbroken history. Vazquez wrote: "we feel we are the

inheritors of 4000 years of architecture integrated by the

highest tradition of indigenous America and by one of the

deepest branches of Western architecture, our mission in

the future cannot forsake these precedents" (Figure 5).

The Unification of Modernism and Mexican Patrimony

In 1963, a year before the ratification of the Venice Charter,

architect Ricardo de Robina published an essay in which he

analyzed the development of modern architecture in Mexico

between 1938 and 1963.24 As some of his colleagues already

had done, he postulated that Mexican historic architecture ?

in both its aesthetic and material traditions ?had conferred a

distinctive aspect to Mexican modern architecture, different

from other national modern architectures. Mexican modern

architecture was, in de Robina's analysis, a local adaptation

of internacionalismo, the Spanish term for Henry-Russell Hitch

cock and Philip Johnson's International Style. However, he

noted that Mexican architecture was not entirely explicable

through the rubric postulated by Hitchcock and Johnson.25 De

Robina wrote: "Historic presence lets itself be felt today...

even when architecture that ignores traditional values is car

ried out, even then, it doesn't have a character of ignoring

these values, but of a struggle which is aware of them."26

De Robina later reiterates his theme, that modern Mexican

architecture maintained an indelible bond with its historic

roots: "The new [Mexican] architecture will be no exception

to [the historical constants] and will tend to form ?as one of

its basic assumptions ?an expressive and material bond

with the past."27

The completion of the La Plaza de las Tres Culturas in

1963 was physical testimony of this idea. The complex was

constructed as the heart of a development in Nonoalco

Tlatelolco, Mexico City, and named after Presidente Adolfo

Lopez Mateos. This major housing project was constructed

on a large parcel of land located to the north of the city's his

toric center; the lead architect, Mario Pani, was the most

66

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I fi H BS tlffejte^? ? ?..;

I i e I ^ |1h ^

5 Secretarfa de Relaciones Exteriores

(Foreign Affairs Ministry), Tlatelolco,

Pedro Ramirez Vazquez, architect,

1965. From the magazine Arquitectura

Mexico 99 (1967): 187

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

144

j -

AT

OFt

-wimpool

6. Ciudad Universitaria campus, experienced architect in large-scale housing in Mexico.28

Mexico City, UNAM. Pedro Ramirez

The size and the human density of Pani's architectural project

Vazquez, 4000 ahos de arquitectura

Mexicana, 303. were huge, with nearly twelve thousand apartments housing

some seventy thousand people.29 Within this massive urban

and architectural conglomeration, the public space of the

Plaza de las Tres Culturas was conceived as the scheme's

symbolic heart, the most significant national work of arch

itecture in Mexico after the completion of the Ciudad Univer

sitaria in 1954 (Figure 6). The entire development serves

as testimony to the attitudes both toward new construction

and heritage held by Mexican architects of the modern

movement.

The Nonoalco-Tlatelolca tribe founded the city of Nonoalco

Tlatelolco in 1325. This city was the twin of nearby Mexico

Tenochtitlan. At the site, a pre-Hispanic pyramid stood at the

moment of the building of the Plaza de las Tres Culturas near

a church built by Franciscan missionaries in the sixteenth

century.30 Those two sites were protected by INAH's historic

monuments law, and Pani and the architectural team were

required to construct across from the archeological space.31

They brought the design well beyond this state with the deci

sion?made together with the political authorities?to place

the tower of the Foreign Affairs Ministry at the southern limit

of the complex. The commission for the tower was awarded to

68

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Pedro Ramirez Vazquez,32 who had recently designed the

Museo Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, one of the

emblematic Mexican buildings of the second half of the cen

tury. The official publication placed the entire project in the

context of Mexico's historic patrimony: "special interest has

been assigned [to this dwelling] in addition to its significance

as one of the most important facilities for social benefit built

in a city of five million inhabitants, to its contribution to the

teaching of our history and to the spreading of our culture."33

The inauguration ceremony took place on the Plaza de las

Tres Culturas, which is an indicator with which to measure

within the value scale of the Mexican government?the impor

tance of the space that the Mexican architects had recently

transformed. The historic site was no longer a simple archaeo

logical monument once it had been integrated with new con

struction; instead, following the Mexican architectural theories

of the previous half-century, the archeological vestiges were

reinterpreted as critical roots of Mexican modern architecture.

Indeed, the culture of Mexican identity had consolidated by

this historical juncture: Mexicanness was conceived as the

sentimental?and, as such, also spiritual?relation to the

local past, understood as the social and historical events that

took place in the territory of the Mexican Republic. In this sense,

architects looked to the premodern past, but not in the man

ner, for example, of the Florentine Renaissance, when archi

tects directly copied the ruins of Rome. Rather, in Mexico,

there was an emphasis on abstraction enabled precisely by

the notion of a permanent national or Mexican architecture.

"Neo-viceregal" and "neo-indigenous" -isms should thus be

seen as formulas of "style," in the same manner in which they

were applied in the second half of the nineteenth century.34

The Plaza de la Tres Culturas is particularly noteworthy

as an example of this attitude. The urban project juxtaposed

architectures from three different historic periods?without

trying to find material equivalence between the modern build

ings and the historic monuments ?in order to conform an

abstract urban space containing physical cultural symbols

of preexisting architecture (Figure 7). Although the creation

of collective recreational space was a functional element of

the project, its main mission was to convey a wider cultural

message: that the past and the present of the country were

expressed at once within a new modern framework of national

identity.35 A reading of some of the concepts in the official

publications shows that this was a matter of deliberate intent,

especially when the design highlighted the relationships

between the new buildings and the archeological vestiges

they faced: "(in the plaza area) the restoration of the whole of

69

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

"fi

I1:

7. Plaza de las Tres Culturas (The the archeological site takes place, of which the main part is

Plaza of the Three Cultures). Conjunto

urbano, 219.

pre-Columbian pyramid ... El Templo de Santiago [Santiago

Temple]... [and] El Colegio de La Santa Cruz [The Holy Cros

College]... all of these works shall harmonize with the diff

ent buildings of contemporary architecture to be construct

in that section"36 (Figure 8).

To conclude, in 1963 and in an urban development larg

dictated by the orthodoxies of the modern movement, the

preservation of the vestiges of the past was not only the ob

of great concern but was also used to support the cultural

70

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WIN

-

NK1- ~.L

8. Plaza dedoctrine

las of anTres

official "nationalCulturas

identity" policy by taking (The

Plaza of the Three Cultures). From

the

the old buildings

magazine

themselves as historic symbols, considered

Arquitectura Mexico

99 (1967): 188. apart from their architectural significance. The Mexican cul

ture of identity, whose origins can be traced to the early twen

tieth century, carried with it a high regard for the architectural

values of cultures of the past, as well as the need to guarantee

the preservation of the buildings wherever these values were

manifest. In arguing for these affinities, modernist architects

provided a continuum of history to Mexican architecture and a

successful appropriation of the past, which in turn gave way

to a model of architectural Mexicanness that continues to be

felt into the present.

Author Biography

Enrique X. de Anda Alams is an art historian at UNAM (National University of

Mexico) in Mexico City, and a researcher at the Instituto de Investigaciones

Esteticas at the same institution. He specializes in Mexican modern architecture

and the preservation of cultural heritage, and is responsible for the group of

twentieth-century specialists of ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments

and Sites) in Mexico and Latin America. He has published more than twenty

books on the history of modern architecture.

71

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Endnotes

1. See Jesus T. Acevedo, Disertaciones de un arquitecto (Mexico: Biblioteca de

Autores Mexicanos, 1920).

2 On December 31,1938, the creation of the National Institute of Anthropology

(INAH) was decreed; on December 31,1945, the internal law of the National Insti

tute of Fine Arts (INBA) was approved. See volume 7 of Enciclopedia de Mexico

(Mexico City: Jose Rogelio Alvarez 1978).

3 See Enrique X. de Anda A., coordinator, Ciudad de Mexico: Arquitectura 1921-1970

(Sevilla: Junta de Andalucia, 2001).

4 See Enrique X. de Anda A., La Arquitectura de la Revolution Mexicana: Corrientes

yestilos en la decada de los Veinte, 2nd ed. (Mexico: UNAM, 2008).

5 The bibliography on Jose Vasconcelos is abundant; see Claude Fell, Jose Vascon

celos: Los ahos del aguila (Mexico: UNAM, 1989).

6 The National School of Architecture evolved from the Academy of Fine Arts of

San Carlos (1783); as a school it was and still is linked to the National University

of Mexico and became the School of Architecture in 1929.

7 Federico Mariscal y Pina. (1881-1971). The importance of Mariscal derives from

his having been a teacher of the history of architecture, a renowned constructor,

director of the National School of Architecture and president of the Mexican Archi

tects Association. See Diccionario Porrua (Mexico: Editorial Porrua, 1964), 2120.

8 Federico Mariscal, La patria y la arquitectura national (Mexico imprenta Stephan

Torres, 1915).

9 See, among other references: Enrique X. De Anda A., "La identidad nacionalista

del estilo neocolonial y su persistencia en la cultura mexicana moderna" (Nation

alistic identity of the neo-viceregal style and its persistence in Mexican modern

culture), in Una mirada a la arquitectura mexicana del sigloXX (Diez ensayos)

(Mexico: ONACULTA, 2005).

10 Jesus T. Acevedo, in his lectures ?starting in 1907?began proposing the

configuration of a new architectonic program with forms adopted from viceregal

architecture. Acevedo, Disertaciones de un arquitecto.

11 Mariscal, La patria y la arquitectura national, 10-11.

12 Ibid., 10.

13 Ibid., 11.

14 Ignacio Marquina, Memorias, 1st ed. (Mexico, INAH, 1964).

15 See Rafael Lopez Rangel, Enrique Ydhez en la cultura arquitectdnica mexicana

(Mexico: UAM Atzcapozalco, Editorial Limusa, 1989)

16 Gabriel Garcia Maroto, Arquitectura popular en Mexico (Mexico City: INBA,

1954). 5- Text and photographs by Gabriel Garcia Maroto.

171. E. Myers, Mexico's Modern Architecture (New York: Architectural Book Publish

ing Co., 1952), 266.

18 See the lecture by Jose Villagran G. in Panorama de 50 ahos de arquitectura con

tempordnea, (Mexico: INBA, 1952).

19 Garcia Maroto, Arquitectura popular en Mexico.

20 Ibid., 5.

21 Ibid., 9.

22 Ibid.

23 Pedro Ramirez Vazquez, 4000 anos de arquitectura mexicana (Mexico: Sociedad

de Arquitectos Mexicanos, Colegio Nacional de Arquitectos Mexicanos, 1956).

24 Ricardo de Robina, "25 anos de arquitectura mexicana, dialogo en torno a

su supuestos, sus logros y sus directivas, 1938-1963," Arquitectura Mexico 83

(Sept 1963).

25 Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson, The International Style (New York:

W.W. Norton Company, 1932), 260.

26 Ricardo de Robina, "25 anos de arquitectura mexicana," emphasis added.

27 Ibid. One last quote has to do with the explanation he gave to color as a con

stant in Mexican architecture; he wrote that Modern Mexican architecture pre

serves chromatic values "in the same way as pre-Hispanic architecture was

exhaustively colorful, through the use of painted stucco, a tradition which was

carried on by the architecture of the convents of the sixteenth century [and that

was to be] changed in the eighteenth century to a severe polychromy with natural

materials"; it should be pointed out that de Robina also did archeological

research work on pre-Hispanic architecture.

28 Enrique X. de Anda A., La vivienda colectiva de la modernidad en Mexico: Los

multifamiliares durante el periodo presidential de Miguel Aleman (1946-1952)

(Mexico City: UNAM, 2008); Louise Noelle, ed., Mario Pani (Mexico City: UNAM,

2008).

29 Conjunto urbano "Presidente Lopez Mateos" (Nonoalco-Tlatelolco) (Mexico

City: Banco Nacional Hipotecario Urbano y de Obras Publicas, S.A., 1963).

72

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

30 The church of Santiago was built by order of Carlos V in 1543. The College of

Santa Cruz was built by order of the Viceroy of Mendoza in 1536 and was the first

college in America dedicated to the teaching of native noble men. See Diccionario

Porrua (Mexico City: Editorial Porrua, 1964), 357.

31 The 1938 law of historical monuments protected the historical vestiges at the

moment of the architectonic intervention by the group lead by Mario Pani.

32 The construction of three Museums had been planned in the site of the "Plaza

of the Three Cultures." See Conjunto Urbano, 233.

33 Ibid., 215.

34 See Aracy Amaral et al., Arquitectura neocolonial en America latina: Caribe,

Estados Unidos, 1st ed. (Sao Paulo: Memorial Fondo de Cultura Economica, 1994),

336.

35 "National identity" is here understood as an abstract condition related to the

particular culture of a group in a country at a historical moment. It is interesting

to point out that the term is the collective "conscience" that?based on inherent

features ?a social group might have in orderto distinguish itself from others.

36 Conjunto Urbano, 233.

This content downloaded from

200.194.42.143 on Wed, 04 May 2022 00:11:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Koontz Visual Culture StudiesDocument5 pagesKoontz Visual Culture StudiesJanaMuseologiaNo ratings yet

- Mexican MuralismDocument6 pagesMexican Muralismrsbasu0% (1)

- Studio GBL - 2016 - Texte - A G - H Frampton - 2015 - S 6-17Document19 pagesStudio GBL - 2016 - Texte - A G - H Frampton - 2015 - S 6-17Nikola Kovacevic100% (1)

- How To Access The Akashic RecordsDocument8 pagesHow To Access The Akashic Recordsthanesh singhNo ratings yet

- The American Places of Charles W. MooreDocument10 pagesThe American Places of Charles W. MooreValentín Martínez, ArquitectoNo ratings yet

- Giedion, Sert, Leger: Nine Points On MonumentalityDocument5 pagesGiedion, Sert, Leger: Nine Points On MonumentalityManuel CirauquiNo ratings yet

- EstridentópolisDocument27 pagesEstridentópolisArt DNo ratings yet

- Architecture of The 40sDocument21 pagesArchitecture of The 40sScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- MuralPaintinginMexicoandtheUSA EvaZettermanDocument17 pagesMuralPaintinginMexicoandtheUSA EvaZettermanSenad BegovicNo ratings yet

- Beyond Tlatelolco Design Media and Polit PDFDocument27 pagesBeyond Tlatelolco Design Media and Polit PDFeisraNo ratings yet

- CASTEÑEDA. Beyond TlatelolcoDocument28 pagesCASTEÑEDA. Beyond TlatelolcoRoberta PlantNo ratings yet

- Moteuczoma Reborn: Biombo Paintings and Collective Memory in Colonial Mexico CityDocument17 pagesMoteuczoma Reborn: Biombo Paintings and Collective Memory in Colonial Mexico CityPriya SeshadriNo ratings yet

- Juan Ogorman Vs The International StyleDocument7 pagesJuan Ogorman Vs The International StyleMaria JoãoNo ratings yet

- Architectural Culture in The Fifties: Louis Kahn and The National Assembly Complex in DhakaDocument20 pagesArchitectural Culture in The Fifties: Louis Kahn and The National Assembly Complex in DhakaSomya InaniNo ratings yet

- American Junkspace: The Discourse of Contemporary American ArchitectureDocument9 pagesAmerican Junkspace: The Discourse of Contemporary American ArchitectureEzequiel VillalbaNo ratings yet

- Identify and Analyse The Political Ideals Present in One Major Work of Mexican Muralist ArtDocument9 pagesIdentify and Analyse The Political Ideals Present in One Major Work of Mexican Muralist ArtalejandraNo ratings yet

- Laa Bibliography PDFDocument18 pagesLaa Bibliography PDFPablo Muñoz PonzoNo ratings yet

- Condesa TópicoDocument5 pagesCondesa TópicoMarcelo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Unit Ii: History of Architecture & Culture - ViDocument51 pagesUnit Ii: History of Architecture & Culture - ViPrarthana roy RNo ratings yet

- MuralismDocument3 pagesMuralismCarolina RoblesNo ratings yet

- The Vernacular Between Theory and practice-C.Machat PDFDocument14 pagesThe Vernacular Between Theory and practice-C.Machat PDFAlin TRANCUNo ratings yet

- Iafor: Writing of The History: Ernesto Rogers Between Estrangement and Familiarity of Architectural HistoryDocument12 pagesIafor: Writing of The History: Ernesto Rogers Between Estrangement and Familiarity of Architectural HistoryF Andrés VinascoNo ratings yet

- Unit I: History of Architecture & Culture - ViDocument44 pagesUnit I: History of Architecture & Culture - ViPrarthana roy RNo ratings yet

- 2017 Articulo Classical Readings For Chi PDFDocument10 pages2017 Articulo Classical Readings For Chi PDFDiego IcazaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 170.239.168.67 On Tue, 23 Mar 2021 19:59:42 UTCDocument30 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 170.239.168.67 On Tue, 23 Mar 2021 19:59:42 UTCAgus DemNo ratings yet

- Review Essay: Mexico: Biography of Power by Enrique Krauze. Translated by HankDocument14 pagesReview Essay: Mexico: Biography of Power by Enrique Krauze. Translated by HankLuis Rubén Hernández GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- The Fate of Mesopotamian Architecture inDocument13 pagesThe Fate of Mesopotamian Architecture inMuhammad BrohiNo ratings yet

- C Ssic S: The Ultu F Ti D RN Arch Te Ur R Manti Mandre Teqreuon B TweenDocument1 pageC Ssic S: The Ultu F Ti D RN Arch Te Ur R Manti Mandre Teqreuon B TweenGil EdgarNo ratings yet

- Re Reading The EncyclopediaDocument10 pagesRe Reading The Encyclopediaweareyoung5833No ratings yet

- 2018 4 1 2 MagalhaesDocument22 pages2018 4 1 2 MagalhaesSome445GuyNo ratings yet

- Cosentino, A Cartographic ReckoningDocument16 pagesCosentino, A Cartographic ReckoningEfren SandovalNo ratings yet

- BTC 3 2011Document5 pagesBTC 3 2011Dl DodhedNo ratings yet

- Mexican MuralismDocument3 pagesMexican MuralismNatalia ChillemiNo ratings yet

- Ch'u MayaaDocument14 pagesCh'u MayaaJesse LernerNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Arts Week 56Document3 pagesContemporary Arts Week 56jayveenalsoclaritNo ratings yet

- LECTURA 7 - CarpoDocument12 pagesLECTURA 7 - CarpofNo ratings yet

- Forging A Popular Art HistoryDocument17 pagesForging A Popular Art HistoryGreta Manrique GandolfoNo ratings yet

- A Nationalist Metaphysics: State Fixations, National Maps, and The Geo-Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century MexicoDocument36 pagesA Nationalist Metaphysics: State Fixations, National Maps, and The Geo-Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century MexicoRene ToapantaNo ratings yet

- Post War Philippines ArchitectureDocument10 pagesPost War Philippines ArchitectureElaiza FuentesNo ratings yet

- DDocument14 pagesDapi-706911799No ratings yet

- Noguchi in MexicoDocument25 pagesNoguchi in MexicoMario MonterrosoNo ratings yet

- Brulon Soares-The Myths of MuseologyDocument19 pagesBrulon Soares-The Myths of MuseologyflorenciacolomboNo ratings yet

- Theory of Architecture (Toa) : Name SRNDocument28 pagesTheory of Architecture (Toa) : Name SRNDhanush KeshavNo ratings yet

- Modern Mexico CityDocument61 pagesModern Mexico CityPriya SeshadriNo ratings yet

- Blier, S. Vernacular ArchitectureDocument24 pagesBlier, S. Vernacular ArchitecturemagwanwanNo ratings yet

- El Elogio de Las OllasDocument21 pagesEl Elogio de Las OllasDeborah DorotinskyNo ratings yet

- Critical Fortune of Brazilian Modern Architecture 1943-1955Document20 pagesCritical Fortune of Brazilian Modern Architecture 1943-1955Luca Luini100% (1)

- ARTICULO PALLINI - Schools and Museums in Greece PDFDocument13 pagesARTICULO PALLINI - Schools and Museums in Greece PDFIsabel Llanos ChaparroNo ratings yet

- 05-Art - Folklore - and Industry - Popular Arts and Indigenismo in Mexico - 1920 - 1946Document25 pages05-Art - Folklore - and Industry - Popular Arts and Indigenismo in Mexico - 1920 - 1946Anamaria Garzon MantillaNo ratings yet

- From The Screen To The Wall Siqueiros and EisensteinDocument26 pagesFrom The Screen To The Wall Siqueiros and EisensteinPazuzu8No ratings yet

- Rural and Urban Schools: Northern Greece in The Interwar PeriodDocument10 pagesRural and Urban Schools: Northern Greece in The Interwar PeriodAleksandar AšaninNo ratings yet

- Codex AzcatitlanDocument17 pagesCodex AzcatitlanCarlos Quintero MunguíaNo ratings yet

- Neo Baroque CodexDocument19 pagesNeo Baroque CodexAnonymous iGdPMJwKNo ratings yet

- J. B. 杰克逊和景观设计师-劳里-奥林-2020Document5 pagesJ. B. 杰克逊和景观设计师-劳里-奥林-20201018439332No ratings yet

- Troubles in Theory I - The State of The Art 1945-2000 - Architectural ReviewDocument12 pagesTroubles in Theory I - The State of The Art 1945-2000 - Architectural ReviewPlastic SelvesNo ratings yet

- In Progress: New Monumentality S Retrospective JustificationDocument41 pagesIn Progress: New Monumentality S Retrospective JustificationMaria Camila GonzalezNo ratings yet

- 05CURRENTNEWS IT B07-En-1Document10 pages05CURRENTNEWS IT B07-En-1Isaac TameNo ratings yet

- Society of Architectural Historians University of California PressDocument5 pagesSociety of Architectural Historians University of California Press槑雨No ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Regionalism and IdentityDocument36 pagesChapter 2 - Regionalism and IdentityAr Shahanaz JaleelNo ratings yet

- 3 HOUSES Luis Barragan - English-RoquimeDocument34 pages3 HOUSES Luis Barragan - English-RoquimeRoquime Roquime100% (1)

- Designs of Destruction: The Making of Monuments in the Twentieth CenturyFrom EverandDesigns of Destruction: The Making of Monuments in the Twentieth CenturyNo ratings yet

- Braintree 15Document6 pagesBraintree 15paypaltrexNo ratings yet

- PPE Lab ManualDocument27 pagesPPE Lab ManualDinesh Chavhan100% (1)

- HBS Assessment Feedback Form IndividualDocument1 pageHBS Assessment Feedback Form IndividualsarithaNo ratings yet

- JLTR, 02Document8 pagesJLTR, 02Junalyn Villegas FerbesNo ratings yet

- Pac CarbonDocument172 pagesPac CarbonBob MackinNo ratings yet

- Nature of Bivariate DataDocument39 pagesNature of Bivariate DataRossel Jane CampilloNo ratings yet

- Financial Summary Statement Period 03/10/23 - 04/09/23: Deposit Accounts Total DepositsDocument14 pagesFinancial Summary Statement Period 03/10/23 - 04/09/23: Deposit Accounts Total DepositsLuis RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Actuator-Sensor-Interface: I/O Modules For Operation in The Control Cabinet (IP 20)Document22 pagesActuator-Sensor-Interface: I/O Modules For Operation in The Control Cabinet (IP 20)chochoroyNo ratings yet

- PCR AslamkhanDocument1 pagePCR AslamkhanKoteswar MandavaNo ratings yet

- XAI P T A Brief Review of ExplainableDocument9 pagesXAI P T A Brief Review of Explainableghrab MedNo ratings yet

- Research MethodologyDocument2 pagesResearch MethodologyrameshNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3. Functions and Philosophical Perspectives On Art - PDF - Philosophical Theories - EpistemologyDocument362 pagesLesson 3. Functions and Philosophical Perspectives On Art - PDF - Philosophical Theories - EpistemologyDanica Jeane CorozNo ratings yet

- Cost Justifying HRIS InvestmentsDocument19 pagesCost Justifying HRIS InvestmentsJessierene ManceraNo ratings yet

- Procedure: Administering An Intradermal Injection For Skin TestDocument3 pagesProcedure: Administering An Intradermal Injection For Skin TestSofia AmistosoNo ratings yet

- The Wild BunchDocument2 pagesThe Wild BuncharnoldNo ratings yet

- Section 2 Digital OutputDocument1 pageSection 2 Digital Outputsamim_khNo ratings yet

- Cyctocyle - Care PlanDocument22 pagesCyctocyle - Care Planarchana vermaNo ratings yet

- Imj 13707Document11 pagesImj 13707Santiago López JosueNo ratings yet

- 3 2 A UnitconversionDocument6 pages3 2 A Unitconversionapi-312626334No ratings yet

- Exterior & Interior: SectionDocument44 pagesExterior & Interior: Sectiontomallor101No ratings yet

- Water Pollution 2 (Enclosure)Document10 pagesWater Pollution 2 (Enclosure)mrlabby89No ratings yet

- A Bluetooth ModulesDocument19 pagesA Bluetooth ModulesBruno PalašekNo ratings yet

- Primary Worksheets: Frog Life CycleDocument6 pagesPrimary Worksheets: Frog Life CycleMylene Delantar AtregenioNo ratings yet

- Opsrey - Acre 1291Document97 pagesOpsrey - Acre 1291Hieronymus Sousa PintoNo ratings yet

- Pack 197 Ana Maria Popescu Case Study AnalysisDocument16 pagesPack 197 Ana Maria Popescu Case Study AnalysisBidulaNo ratings yet

- Digipay GuruDocument13 pagesDigipay GuruPeterhill100% (1)

- CS701 - Theory of Computation Assignment No.1: InstructionsDocument2 pagesCS701 - Theory of Computation Assignment No.1: InstructionsIhsanullah KhanNo ratings yet

- Topic On CC11Document3 pagesTopic On CC11Free HitNo ratings yet