Professional Documents

Culture Documents

MapGallery2018 V2 Reduced

MapGallery2018 V2 Reduced

Uploaded by

Jacob HelfmanOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

MapGallery2018 V2 Reduced

MapGallery2018 V2 Reduced

Uploaded by

Jacob HelfmanCopyright:

Available Formats

•This method was chosen since the last mini project determined positive spatial autocorrelation at a distance band

of ~1,200 meters. After the annual crime data was joined to the 100 meter grid, python field calculations were used to replace nulls with zeros.

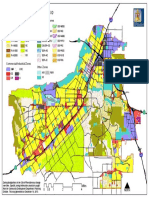

Barrio Logan: An Exploratory Data Analysis

by Jacob Helfman Scan this QR code to be directed to the accompanying story map (http://arcg.is/4yb0S):

Results

Directional distribution ellipse is wider in Downtown than in

Barrio Logan

Ellipses overlap on National Avenue, at 7 project locations

Clustering of vandalism is not random per the spatial

autocorrelation

Zmax = 11.2 at 1,200 meters (~ length of project area)

Crime cold spots become less intense from 2011 to 2013

Hot spots generally moved in an eastward direction

Statistically significant clustering of crime occurred in Downtown

and Barrio Logan

Distance (m) Moran’s index Z score

400 0.103425 8.616853

600 0.082000 9.947152

800 0.064028 10.050397

1000 0.056483 10.927497

1200 0.049656 11.200711

1400 0.039695 10.362309

1600 0.033047 9.759855

1800 0.031065 10.251189

2000 0.027429 10.042618

Introduction Research Questions

Barrio Logan is one of the most important pieces of history for San Diego, Chicano Civil 1. Where are there patterns of vandalism relative to unpainted utility boxes in Barrio Logan?

Rights and the Chicano Art Movement. Its neighborhoods have historically endured 2. Is there a directional trend or pattern to this variation? Where is there clustering? How has this changed over time?

hardships, including discriminatory zoning laws and significantly negative impacts to its

businesses and housing. Since the protests of 1970, which led to the creation of Chicano Park, 3. What is the best way to have the community explore the utility box public art project?

the community has experienced resilience, economically and artistically. A public art program

would further engage the community and contribute to neighborhood beautification. The

predictive capabilities of hotspot mapping[1] inspired me to conduct a spatiotemporal crime Methods

analysis centered around a mock public art program in Barrio Logan. The program involved Software: ArcGIS Pro 2.1 and ArcMap 10.6.

mapping out potential project locations which were mostly unpainted utility box structures Exploring patterns of vandalism

located along the community’s north main streets (Figure 1). Data was acquired from the San Diego Regional Data Library’s 2007-2013 dataset[4]

It is suggested by some that communities that engage in public art experience Mean Center, Center Feature, and Directional Distribution (Standard Deviational Ellipse) tools

improved economic development[2] and decreased crime rates[3]. In addition, a public art were used to identify spatial patterns of vandalism

program can be considered a countermeasure against illegal graffiti and tagging. Performing a The Spatial Autocorrelation (Global Moran’s I) tool was used to determine whether the crime

geostatistical analysis on crime data in the Barrio Logan and its surrounding communities data was clustered, random or dispersed. The results were used to guide the Hot Spot Analysis.

would be useful in developing a successful public art program. The results of this analysis Determining crime clusters

could help direct our attention to areas with higher incidences of crime and eventually A Hot Spot Analysis (Getis-Ord Gi*) was run on the “Count” field using the Euclidian distance

determine whether there’s a relationship between public art and higher crime rates. This method and a fixed distance band of 1,200 meters (the approximate length of the potential

could influence where utility boxes are painted and what art styles are chosen for that project area).

location. Perhaps the utility boxes could be strategically painted to prevent graffiti in areas of Engaging with the public References

significantly clustered incidences of crime. Story Map (see link/QR code at the top of this poster). The Story Map features two separate 1. Swain, A. W. 2012. A Comparison of Hotspot Mapping for Crime Prediction. Lancaster University (20th annual GIS Research UK Conference), April 2012.

https://www.geos.ed.ac.uk/~gisteac/proceedingsonline/GISRUK2012/Papers/presentation-72.pdf

maps, one map that highlights businesses, restaurants and art galleries, and a another map 2. Rosenfeld, D. 2012. “The Financial Case for Public Art.” CITYLAB, May 28, 2012. https://www.citylab.com/design/2012/05/financial-case-public-art/2113/

3. Sakip, S. R. M. et al. 2012. The Relationship between Crime Prevention through Environmental Design and Fear of Crime. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences (ASIA Pacific

featuring the potential locations for public art projects. International Conference on Environment-Behavior Studies). December 9, 2012. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042812057370#!

4. San Diego Regional Data Library. San Diego Region Crime Incidents 2007 – 2013 [Shapefiles]. Created May 13, 2013. Available via San Diego Regional Data Library website:

https://data.sandiegodata.org/dataset/clarinova_com-crime-incidents-casnd-7ba4-extract/resource/45edbde0-1179-44ac-8eac-19c446f50cc9. Accessed April 15, 2018.

You might also like

- Lab 12Document13 pagesLab 12Brian PaciaNo ratings yet

- Scaffold Designs - Chadworth House Elevation PDFDocument1 pageScaffold Designs - Chadworth House Elevation PDFsabeerNo ratings yet

- Instant Assessments for Data Tracking, Grade K: Language ArtsFrom EverandInstant Assessments for Data Tracking, Grade K: Language ArtsNo ratings yet

- Interview Questions - Oracle Order ManagementDocument6 pagesInterview Questions - Oracle Order ManagementMohamed Fathy Hassan100% (1)

- 1.3 Extragalactic EmpiricismDocument4 pages1.3 Extragalactic EmpiricismSHAM painNo ratings yet

- Two-Way Mobility Adams & Forsyth Streets: City of Jacksonville NotesDocument133 pagesTwo-Way Mobility Adams & Forsyth Streets: City of Jacksonville NotesJJNo ratings yet

- Charlotte-Mecklenburg Area Plans That Update The District PlansDocument1 pageCharlotte-Mecklenburg Area Plans That Update The District PlansIsabelle WesternNo ratings yet

- Head LossDocument1 pageHead LossamrNo ratings yet

- Suction Head CalcDocument5 pagesSuction Head CalcNghiaNo ratings yet

- My Portfolio: Engr. Wilfredo P Purisima Jr. LICENSED NO. 0068441 Licensed Electrical EngineerDocument16 pagesMy Portfolio: Engr. Wilfredo P Purisima Jr. LICENSED NO. 0068441 Licensed Electrical Engineerwil purisimaNo ratings yet

- DMM 1 e 007Document1 pageDMM 1 e 007mahesh reddy mNo ratings yet

- Souq Waqif CHW Pump Head - Rev-01a As Per Approved DWGDocument1 pageSouq Waqif CHW Pump Head - Rev-01a As Per Approved DWGKarthy GanesanNo ratings yet

- Bound State Paper ArXivDocument16 pagesBound State Paper ArXivmipiacemrgoldsteinNo ratings yet

- Art RT WE1 re-PQDocument2 pagesArt RT WE1 re-PQrunewise9311No ratings yet

- RF and EMC Formulas and Charts: Conversions for 50Ω Environment Antenna Equations www.arworld.usDocument1 pageRF and EMC Formulas and Charts: Conversions for 50Ω Environment Antenna Equations www.arworld.usamirNo ratings yet

- Major1107202x12.2pscslab V4 Approve P11Document1 pageMajor1107202x12.2pscslab V4 Approve P11rushi123No ratings yet

- Cmit 220046 000 SCW 15.01 0001 0Document12 pagesCmit 220046 000 SCW 15.01 0001 0Ali SalehNo ratings yet

- 2021FPSO OffshoreDocument1 page2021FPSO OffshoreShafif SalehNo ratings yet

- Singularities in Differential Equations: Singularities Often of Important Physical SignificanceDocument11 pagesSingularities in Differential Equations: Singularities Often of Important Physical SignificanceSamir HamdiNo ratings yet

- Industrisl Security Building Office Finishing ScheduleDocument1 pageIndustrisl Security Building Office Finishing ScheduleBrando BandidoNo ratings yet

- Type A1 First Floor CSD Sign Off - Submittal #174Document2 pagesType A1 First Floor CSD Sign Off - Submittal #174nuraishah zulkifliNo ratings yet

- Illumination Design: Single Dwelling JAJ Sentina JAJ SentinaDocument2 pagesIllumination Design: Single Dwelling JAJ Sentina JAJ SentinaEl Vee Joice HaroNo ratings yet

- 5G Architecture and SpecificationsDocument1 page5G Architecture and Specificationshrga hrgaNo ratings yet

- Kanawat Zoning MapDocument1 pageKanawat Zoning MapLOKUT LocapNo ratings yet

- Petrophysicist OkeDocument16 pagesPetrophysicist OkeRiau Amuri AndalanNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3: Approximate Analysis: ECE 5984: Power Distribution System AnalysisDocument17 pagesLecture 3: Approximate Analysis: ECE 5984: Power Distribution System Analysisante mitarNo ratings yet

- Legible Sydney Design Manual Part 2ADocument9 pagesLegible Sydney Design Manual Part 2ApramodsagarvsNo ratings yet

- Mặt Bằng Trệt Tổng Thể (Xây Mới)Document1 pageMặt Bằng Trệt Tổng Thể (Xây Mới)nhacotungNo ratings yet

- New York City Base Map: Street Borough BoundaryDocument1 pageNew York City Base Map: Street Borough BoundaryFrank RasoNo ratings yet

- Poster Test v24 BaseDocument1 pagePoster Test v24 Basetrungkien131201No ratings yet

- AD370NDocument2 pagesAD370NmnjobenNo ratings yet

- JW 13859 - DrawingsDocument2 pagesJW 13859 - Drawingskamogelo MolalaNo ratings yet

- Basement DDA Car ParkingDocument1 pageBasement DDA Car Parkingrajen raghwaniNo ratings yet

- Thiết Kế Kỹ Thuật: Single Line DiagramDocument1 pageThiết Kế Kỹ Thuật: Single Line DiagramAn BuiNo ratings yet

- Project: Zealax Hotel Bms Point Schedule (Ve Version) : No. Panel Name System Description CodeDocument2 pagesProject: Zealax Hotel Bms Point Schedule (Ve Version) : No. Panel Name System Description CodeHnin PwintNo ratings yet

- Transmission Network July, 2021 NEA-ModelDocument1 pageTransmission Network July, 2021 NEA-ModelSuraj DahalNo ratings yet

- Equipments Foundation Layout: Geographic North 22.377° Prevaling Summer Wind S/WDocument1 pageEquipments Foundation Layout: Geographic North 22.377° Prevaling Summer Wind S/Wtitir bagchiNo ratings yet

- Industrisl Security Building Office Schedule of WindowsDocument1 pageIndustrisl Security Building Office Schedule of WindowsBrando BandidoNo ratings yet

- 200 - C01 Existing - Demolition Elevations (AI 001)Document1 page200 - C01 Existing - Demolition Elevations (AI 001)Ekta JadejaNo ratings yet

- Fuel Station Future Extension Natural Soil Gate Security FenceDocument1 pageFuel Station Future Extension Natural Soil Gate Security FenceSyed Munawar AliNo ratings yet

- Fuel Station Future Extension Natural Soil Gate Security FenceDocument1 pageFuel Station Future Extension Natural Soil Gate Security FenceSyed Munawar AliNo ratings yet

- Drwaing Full SetDocument18 pagesDrwaing Full Setserg234sok42No ratings yet

- MagmediaDocument9 pagesMagmedia조성철No ratings yet

- BG2D-Sheet - FP-702 - PELAN BUMBUNG BAWAH, PELAN BUMBUNG, KERATAN A-A & KERATAN B-B-Layout1Document1 pageBG2D-Sheet - FP-702 - PELAN BUMBUNG BAWAH, PELAN BUMBUNG, KERATAN A-A & KERATAN B-B-Layout1Alexander SNo ratings yet

- Head Loss Calculation Circulation PumpDocument1 pageHead Loss Calculation Circulation PumpKarthy Ganesan100% (1)

- Openfoam Simulation of The Flow in The Hoelleforsen Draft Tube ModelDocument15 pagesOpenfoam Simulation of The Flow in The Hoelleforsen Draft Tube ModelAghajaniNo ratings yet

- 1 Chilled Water Pump Head CalculationDocument6 pages1 Chilled Water Pump Head CalculationMohammed TanveerNo ratings yet

- Precinct MapDocument1 pagePrecinct MapHolden AbshierNo ratings yet

- 3 Automotive Component TestingDocument1 page3 Automotive Component Testingjorges_santosNo ratings yet

- Riverside ZoningDocument1 pageRiverside ZoningFAQ MDNo ratings yet

- Dear If You ChangeDocument2 pagesDear If You ChangeLuca ChiavinatoNo ratings yet

- PosterDocument1 pagePosteropabolaNo ratings yet

- Screenshot 2023-05-25 at 1.53.52 PMDocument1 pageScreenshot 2023-05-25 at 1.53.52 PMik27419No ratings yet

- January 2016: Imports & Exports 2014 - 2015Document2 pagesJanuary 2016: Imports & Exports 2014 - 2015hussainNo ratings yet

- Scaled PlanDocument6 pagesScaled PlanDillion BradleyNo ratings yet

- BG-DWG-2023-R0-212 Skylight Access Scaffolding 18-05-2023 P02 of 02Document1 pageBG-DWG-2023-R0-212 Skylight Access Scaffolding 18-05-2023 P02 of 02anilNo ratings yet

- POWERDocument3 pagesPOWERanish.mohanNo ratings yet

- Lecture 11 SlidesDocument15 pagesLecture 11 SlidesDanishNo ratings yet

- 05 Wall Finishes Plan - Al DeerahDocument1 page05 Wall Finishes Plan - Al Deerahhelmymohamed GebrelNo ratings yet

- This Land Is Your LandDocument1 pageThis Land Is Your Landapi-371128894100% (1)

- Edmonds Comprehensive PlanDocument1 pageEdmonds Comprehensive PlanThe UrbanistNo ratings yet

- Geoswath Plus Wide Swath Bathymetry EnglishDocument2 pagesGeoswath Plus Wide Swath Bathymetry EnglishSaad FatrouniNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2: Understanding The Basic Concepts in ICT What To Expect?Document10 pagesLesson 2: Understanding The Basic Concepts in ICT What To Expect?MA. CAROL FLORONo ratings yet

- Shell FaslasknsalfnaskfnklafffgggdffrDocument21 pagesShell FaslasknsalfnaskfnklafffgggdffrVigne SulaimanNo ratings yet

- Comparative - Analysis - of Marketing Strategies of Airtel and VodafoneDocument57 pagesComparative - Analysis - of Marketing Strategies of Airtel and VodafoneJoshua LoyalNo ratings yet

- Finlatics 2Document3 pagesFinlatics 2Divya MNo ratings yet

- WebFilter - Quiz - Attempt Review2Document2 pagesWebFilter - Quiz - Attempt Review2DuangkamonNo ratings yet

- Frequently Asked Questions Cloning Oracle Applications Release 11iDocument18 pagesFrequently Asked Questions Cloning Oracle Applications Release 11iapi-3744496No ratings yet

- Lab 2 Introduction To Labview and Usrp: Principle of Communication Lab ManualDocument7 pagesLab 2 Introduction To Labview and Usrp: Principle of Communication Lab Manualعمیر بن اصغرNo ratings yet

- Essays On Animal Farm by George OrwellDocument7 pagesEssays On Animal Farm by George Orwellezmrfsem100% (2)

- Request For Use of Audiovisual Materials (Images, Films, Sounds) of The German Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv)Document3 pagesRequest For Use of Audiovisual Materials (Images, Films, Sounds) of The German Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv)VishnuNo ratings yet

- D Itg ManualDocument35 pagesD Itg Manualjoto123No ratings yet

- Datacolor Match Textile 1.0 User GuideDocument420 pagesDatacolor Match Textile 1.0 User Guidetkr163No ratings yet

- The Iron Warrior: Volume 24, Issue 5 (Special Edition)Document9 pagesThe Iron Warrior: Volume 24, Issue 5 (Special Edition)The Iron WarriorNo ratings yet

- Week 2 Exercises SolutionsDocument5 pagesWeek 2 Exercises SolutionsJuan Camilo Guarnizo Bermudez100% (1)

- Assignment of Software Quality AssuranceDocument4 pagesAssignment of Software Quality AssuranceMurtazaNo ratings yet

- EasyMotionControl GS eDocument10 pagesEasyMotionControl GS eerikavergaraNo ratings yet

- 56 Gbps Optical Intersatellite Communication LinkDocument9 pages56 Gbps Optical Intersatellite Communication LinkPriyanshu PandeyNo ratings yet

- Modicon Micro and 984 - A120 Compact PLC (1998)Document47 pagesModicon Micro and 984 - A120 Compact PLC (1998)mandster78No ratings yet

- Purpose: WM014 - Create Planned Work OrderDocument32 pagesPurpose: WM014 - Create Planned Work OrderAndrés RodríguezNo ratings yet

- GEOVISUALIZATIONDocument16 pagesGEOVISUALIZATIONAna Nadhirah100% (1)

- Hafele Product CatalogDocument178 pagesHafele Product CatalogMichaelNo ratings yet

- Information Technology: Technical Consultant PanelDocument4 pagesInformation Technology: Technical Consultant PanelmjmacrohonNo ratings yet

- STPM Ict 2019Document3 pagesSTPM Ict 2019Chinong HowNo ratings yet

- Industrial Automation1Document15 pagesIndustrial Automation1anon_91668243No ratings yet

- Types of MediaDocument14 pagesTypes of MediaMary Quincy Marilao100% (1)

- C If Else StatementDocument11 pagesC If Else StatementKiran KalyaniNo ratings yet

- Cghs Form NewDocument3 pagesCghs Form Newmohankseb0% (1)

- PhplotDocument380 pagesPhplotfleysson domingos soaresNo ratings yet