Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Affect in A Behavioral Asset Pricing Model

Affect in A Behavioral Asset Pricing Model

Uploaded by

DebCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Seven Signs of Ethical Collapse: How to Spot Moral Meltdowns in Companies... Before It's Too LateFrom EverandThe Seven Signs of Ethical Collapse: How to Spot Moral Meltdowns in Companies... Before It's Too LateNo ratings yet

- Great by Choice: Uncertainty, Chaos, and Luck--Why Some Thrive Despite Them AllFrom EverandGreat by Choice: Uncertainty, Chaos, and Luck--Why Some Thrive Despite Them AllRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (120)

- DR York - The Eyes Tunnel Vision To The SoulDocument11 pagesDR York - The Eyes Tunnel Vision To The Soulsean lee92% (49)

- Arindam Bandyopadhyay - Basic Statistics For Risk Management in Banks and Financial Institutions-Oxford University Press (2022)Document321 pagesArindam Bandyopadhyay - Basic Statistics For Risk Management in Banks and Financial Institutions-Oxford University Press (2022)Deb100% (1)

- Drexel 10 Yr RetrospectiveDocument41 pagesDrexel 10 Yr RetrospectiveDan MawsonNo ratings yet

- Economic Instructor ManualDocument35 pagesEconomic Instructor Manualclbrack100% (11)

- Literature Review MonopolyDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Monopolyafduaciuf100% (1)

- Essay Questions Chapters 1 Thru 16Document96 pagesEssay Questions Chapters 1 Thru 16DianaNo ratings yet

- An Agent-Based Macroeconomic Model With Interacting Firms, Socio-Economic Opinion Formation and Optimistic/pessimistic Sales ExpectationsDocument39 pagesAn Agent-Based Macroeconomic Model With Interacting Firms, Socio-Economic Opinion Formation and Optimistic/pessimistic Sales ExpectationsLucas AkioNo ratings yet

- Essay Topics For PsychologyDocument5 pagesEssay Topics For Psychologylwfdwwwhd100% (2)

- Reviewofspulberstheory FirmDocument13 pagesReviewofspulberstheory FirmRotsy Ilon'ny Aina RatsimbarisonNo ratings yet

- 2011 Thinking About The Firm - SpulberDocument15 pages2011 Thinking About The Firm - SpulberNicolas SandovalNo ratings yet

- Thinking About The FirmDocument13 pagesThinking About The FirmMaria CindaNo ratings yet

- Rar 1999 Iss32 GirardDocument3 pagesRar 1999 Iss32 GirardSaad CheemaNo ratings yet

- How Do You Compare - Thoughts On Comparing Well - Mauboussin - On - Strategy - 20060809Document14 pagesHow Do You Compare - Thoughts On Comparing Well - Mauboussin - On - Strategy - 20060809ygd100% (1)

- Multi-Billion Dollar Microcap Opportunity Hiding in A Dark AlleyDocument40 pagesMulti-Billion Dollar Microcap Opportunity Hiding in A Dark Alleybiggercapital100% (1)

- Business Ethics ReflectionDocument4 pagesBusiness Ethics ReflectionRon Edward Medina100% (1)

- SP-Distressed Company ValuationDocument18 pagesSP-Distressed Company ValuationfreahoooNo ratings yet

- t3 Presentation Template (Sharkey)Document45 pagest3 Presentation Template (Sharkey)khmaloneyNo ratings yet

- Extracted Pages From Beyond Greed and Fear Understanding Behavioral Finance and The Psychology of Investing (Shefrin)Document20 pagesExtracted Pages From Beyond Greed and Fear Understanding Behavioral Finance and The Psychology of Investing (Shefrin)ms.aminah.khatumNo ratings yet

- Financial Markets and Firm DynamicsDocument25 pagesFinancial Markets and Firm DynamicsGuru PrasadNo ratings yet

- What Do We Need To FixDocument10 pagesWhat Do We Need To Fixkoyuri7No ratings yet

- Prospect Theory ThesisDocument7 pagesProspect Theory Thesisangelabaxtermanchester100% (1)

- Bankruptcy Essay ThesisDocument7 pagesBankruptcy Essay Thesiskrystalgreenglendale100% (1)

- Ase Analysis-Week 1-LayfieldDocument5 pagesAse Analysis-Week 1-LayfieldKylee LayfieldNo ratings yet

- Ethics of SpeculationDocument10 pagesEthics of SpeculationA BNo ratings yet

- A Rose by Any Other Name - Submitted To Journal of Financial and Economic PracticeDocument20 pagesA Rose by Any Other Name - Submitted To Journal of Financial and Economic PracticedrjcthompsonNo ratings yet

- Coremacroeconomics 3rd Edition Chiang Solutions ManualDocument11 pagesCoremacroeconomics 3rd Edition Chiang Solutions Manualphenicboxironicu9100% (33)

- Disappointment in Decision Making Under UncertaintyDocument28 pagesDisappointment in Decision Making Under UncertaintyMarindah PutriNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Lecture 6 - ConfDocument44 pagesBehavioral Lecture 6 - ConfUdit DhawanNo ratings yet

- Risk AversionDocument15 pagesRisk AversionAntía TejedaNo ratings yet

- January 2012Document4 pagesJanuary 2012edoneyNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Myopia and Loss Aversion On Risk TakingDocument16 pagesThe Effect of Myopia and Loss Aversion On Risk TakingbboyvnNo ratings yet

- Against Abortions EssaysDocument49 pagesAgainst Abortions EssaysafabkedovNo ratings yet

- Journal EntriesDocument4 pagesJournal EntriesmanishNo ratings yet

- Game Theory and ExternalitiesDocument21 pagesGame Theory and ExternalitiesAira Jane YaptangcoNo ratings yet

- Intro To Beh. FinanceDocument35 pagesIntro To Beh. FinanceAnonymous YKmreGjNo ratings yet

- Thinking About The Firm: A Review of Daniel Spulber'sDocument14 pagesThinking About The Firm: A Review of Daniel Spulber'sKara JohnsonNo ratings yet

- GREED1 Is Mostly GreedyDocument24 pagesGREED1 Is Mostly GreedyJimmyChaoNo ratings yet

- Deepwater-A Business Ethics Simulation Game-LibreDocument37 pagesDeepwater-A Business Ethics Simulation Game-Libre007003sNo ratings yet

- Financial Institutions Center: by Franklin Allen 01-04Document25 pagesFinancial Institutions Center: by Franklin Allen 01-04Muhammad Haider AliNo ratings yet

- Theory: of TheDocument69 pagesTheory: of TheJulyanto Candra Dwi CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Culture and Capital StructureDocument37 pagesCulture and Capital Structurekurniasilalahi726No ratings yet

- Illuminas The Convergence of B2b and Consumer MarketingDocument30 pagesIlluminas The Convergence of B2b and Consumer MarketingArslan AzamNo ratings yet

- Prospect Theory and Other TopicsDocument19 pagesProspect Theory and Other Topicskhush preetNo ratings yet

- April 2021 Client LetterDocument5 pagesApril 2021 Client LetteramarNo ratings yet

- Bin There Done That - Us PDFDocument19 pagesBin There Done That - Us PDFaaquibnasirNo ratings yet

- Moral Economy of Speculation - Sandel LectureDocument27 pagesMoral Economy of Speculation - Sandel LecturejaribuzNo ratings yet

- WWW: Click On The Web Surfer Icon To Go To The Pricewaterhousecoopers WebDocument15 pagesWWW: Click On The Web Surfer Icon To Go To The Pricewaterhousecoopers WebvvNo ratings yet

- Edgar Allan Poe EssaysDocument7 pagesEdgar Allan Poe Essaysfz6z1n2p100% (2)

- Interpersonal Communication Essay TopicsDocument7 pagesInterpersonal Communication Essay Topicsezm8kqbt100% (2)

- Case Study: Italian Tax MoresDocument8 pagesCase Study: Italian Tax MoresVictorYoonNo ratings yet

- Rise and Fall of Performance InvestingDocument5 pagesRise and Fall of Performance Investingathompson14No ratings yet

- Rational Actors, Tca, P&aDocument14 pagesRational Actors, Tca, P&aPoonam NaiduNo ratings yet

- Report On: - Buyology Team: - Southwest AirlinesDocument12 pagesReport On: - Buyology Team: - Southwest AirlinesPriya SrivastavNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id2613702 PDFDocument61 pagesSSRN Id2613702 PDFmuhjaerNo ratings yet

- Integrity Management: Muel KapteinDocument10 pagesIntegrity Management: Muel KapteinZaimatul SulfizaNo ratings yet

- Tom Sayer and Construction of ValueDocument21 pagesTom Sayer and Construction of ValueDon QuixoteNo ratings yet

- +++ Boom, Bust, Boom - Internet Company Valuation - From Netscape To GoogleDocument20 pages+++ Boom, Bust, Boom - Internet Company Valuation - From Netscape To GooglePrashanth KumarNo ratings yet

- Great by Choice ΓÇô Thriving in Uncertainty-21-24Document4 pagesGreat by Choice ΓÇô Thriving in Uncertainty-21-24FelipeGame21 2No ratings yet

- Investor's Mental Models: Mental Models Series, #3From EverandInvestor's Mental Models: Mental Models Series, #3Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Effects of Monetary Magnitude (Showing Per Day Pricing)Document11 pagesThe Effects of Monetary Magnitude (Showing Per Day Pricing)Geet YadavNo ratings yet

- Linear Equations in Two VariablesDocument8 pagesLinear Equations in Two VariablesDebNo ratings yet

- PolynomialsDocument4 pagesPolynomialsDebNo ratings yet

- 3.coordinate GeometryDocument12 pages3.coordinate GeometryDebNo ratings yet

- Mock CAT - 06 PDFDocument79 pagesMock CAT - 06 PDFDebNo ratings yet

- 5.introduction To Euclid - S GeometryDocument9 pages5.introduction To Euclid - S GeometryDebNo ratings yet

- Number SystemsDocument5 pagesNumber SystemsDebNo ratings yet

- PPTXDocument10 pagesPPTXDebNo ratings yet

- Mock CAT - 04 PDFDocument78 pagesMock CAT - 04 PDFDebNo ratings yet

- Mock CAT - 05 PDFDocument82 pagesMock CAT - 05 PDFDebNo ratings yet

- Exp (% of GDP)Document63 pagesExp (% of GDP)DebNo ratings yet

- 3-Data ReferencingDocument135 pages3-Data ReferencingDebNo ratings yet

- GST Collection Jan'23Document3 pagesGST Collection Jan'23DebNo ratings yet

- 5 SolverDocument11 pages5 SolverDebNo ratings yet

- Case Study Blinds To GoDocument7 pagesCase Study Blinds To GoDebNo ratings yet

- Fiscal ConsolidationDocument11 pagesFiscal ConsolidationDebNo ratings yet

- FinalDocument2 pagesFinalDebNo ratings yet

- Session4 DateDocument364 pagesSession4 DateDebNo ratings yet

- Sec B Gp8 Blinds To Go PDFDocument12 pagesSec B Gp8 Blinds To Go PDFDebNo ratings yet

- 2021 Bull CAT 05Document60 pages2021 Bull CAT 05DebNo ratings yet

- Book 1Document5 pagesBook 1DebNo ratings yet

- 5-Reporting and Data Visualization-1Document111 pages5-Reporting and Data Visualization-1DebNo ratings yet

- 2021 Bull CAT 04 (New Pattern)Document42 pages2021 Bull CAT 04 (New Pattern)DebNo ratings yet

- 2021 Bull Cat 01Document62 pages2021 Bull Cat 01DebNo ratings yet

- 2021 Bull CAT 02Document56 pages2021 Bull CAT 02DebNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 115.124.43.107 On Wed, 18 Jan 2023 06:19:13 UTCDocument33 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 115.124.43.107 On Wed, 18 Jan 2023 06:19:13 UTCDebNo ratings yet

- American Finance Association, Wiley The Journal of FinanceDocument41 pagesAmerican Finance Association, Wiley The Journal of FinanceDebNo ratings yet

- 2021 Bull CAT 03Document58 pages2021 Bull CAT 03DebNo ratings yet

- Bjerring 1983Document18 pagesBjerring 1983DebNo ratings yet

- FULLTEXT01Document60 pagesFULLTEXT01DebNo ratings yet

- Human BodyDocument27 pagesHuman Bodyvigyanashram100% (2)

- Impact of Poor Nutrition On The Academic PerformanDocument13 pagesImpact of Poor Nutrition On The Academic PerformanVictor UgoslyNo ratings yet

- Strengths of Character and VirtuesDocument45 pagesStrengths of Character and VirtuesPraveen BVSNo ratings yet

- One Paper MCQS Dated: 26-04-2021 For The Preparation Of: Today's Dose of PPSC, SPSC, FPSC, NTS, PTS, General TestsDocument7 pagesOne Paper MCQS Dated: 26-04-2021 For The Preparation Of: Today's Dose of PPSC, SPSC, FPSC, NTS, PTS, General TestsRaja NafeesNo ratings yet

- PowerPoint Presentation Perdev by Haillie and JericDocument15 pagesPowerPoint Presentation Perdev by Haillie and JericTetzie Sumaylo100% (1)

- Description of Prototype Modes-of-Action Related To Repeated Dose ToxicityDocument49 pagesDescription of Prototype Modes-of-Action Related To Repeated Dose ToxicityRoy MarechaNo ratings yet

- Albumin Liquicolor: Photometric Colorimetric Test For Albumin BCG-MethodDocument1 pageAlbumin Liquicolor: Photometric Colorimetric Test For Albumin BCG-MethodMaher100% (1)

- Isolation of Phytochemicals and Biological Activity Studies ON The Bark of Thespesia Populnea LinnDocument10 pagesIsolation of Phytochemicals and Biological Activity Studies ON The Bark of Thespesia Populnea LinnRosu SilviaNo ratings yet

- Nextgen Cropscience LLP - CatalogueDocument8 pagesNextgen Cropscience LLP - CatalogueManavasi R SureshNo ratings yet

- English 7: Using Appropriate Reading Styles For One'S PurposeDocument6 pagesEnglish 7: Using Appropriate Reading Styles For One'S PurposeJodie PortugalNo ratings yet

- Post Traumatic Stress Disorder The Neurobiological Impact of Psychological TraumaDocument17 pagesPost Traumatic Stress Disorder The Neurobiological Impact of Psychological TraumaMariana VilcaNo ratings yet

- Biomedical CompositesDocument20 pagesBiomedical Compositesanh lêNo ratings yet

- Journal AlzheimerDocument10 pagesJournal AlzheimerFaza KeumalasariNo ratings yet

- CRA-W Ra03-04 enDocument116 pagesCRA-W Ra03-04 enThanh MiNo ratings yet

- 057Document80 pages057Gonzalo BoninoNo ratings yet

- How To Read PeopleDocument93 pagesHow To Read PeopleJasminaNo ratings yet

- Bark Splitting On Trees 2012Document2 pagesBark Splitting On Trees 2012johnson12mrNo ratings yet

- Personal CareDocument5 pagesPersonal CarePhoebe Mariano100% (1)

- New Zealand Biology Olympiad 2013Document37 pagesNew Zealand Biology Olympiad 2013Science Olympiad BlogNo ratings yet

- Human Anatomy & Physiology ExpDocument38 pagesHuman Anatomy & Physiology Expbestmadeeasy100% (3)

- Landscape ArchitectureDocument2 pagesLandscape ArchitectureJoy CadornaNo ratings yet

- Pathogens: Fungal Pathogens of Maize Gaining Free Passage Along The Silk RoadDocument16 pagesPathogens: Fungal Pathogens of Maize Gaining Free Passage Along The Silk RoadNyemaigbani VictoryNo ratings yet

- Applied Veterinary Histology PDFDocument2 pagesApplied Veterinary Histology PDFAbdulla Hil KafiNo ratings yet

- Final BrochureDocument2 pagesFinal BrochureChrister de SilvaNo ratings yet

- 05 - EnzymesDocument6 pages05 - EnzymesLissa JacksonNo ratings yet

- Contoh UAS XI MADocument4 pagesContoh UAS XI MAChubbaydillahNo ratings yet

- ChloroplastDocument4 pagesChloroplastEmmanuel DagdagNo ratings yet

- (936BCB0C) The Practice of Prolog (Sterling 1990-10-30)Document331 pages(936BCB0C) The Practice of Prolog (Sterling 1990-10-30)Török ZoltánNo ratings yet

Affect in A Behavioral Asset Pricing Model

Affect in A Behavioral Asset Pricing Model

Uploaded by

DebOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Affect in A Behavioral Asset Pricing Model

Affect in A Behavioral Asset Pricing Model

Uploaded by

DebCopyright:

Available Formats

Financial Analysts Journal

ISSN: 0015-198X (Print) 1938-3312 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ufaj20

Affect in a Behavioral Asset-Pricing Model

Meir Statman, Kenneth L. Fisher & Deniz Anginer

To cite this article: Meir Statman, Kenneth L. Fisher & Deniz Anginer (2008) Affect in a Behavioral

Asset-Pricing Model, Financial Analysts Journal, 64:2, 20-29, DOI: 10.2469/faj.v64.n2.8

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v64.n2.8

View supplementary material

Published online: 31 Dec 2018.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 281

View related articles

Citing articles: 1 View citing articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ufaj20

Financial Analysts Journal

Volume 64 • Number 2

©2008, CFA Institute

PERSPECTIVES

Affect in a Behavioral Asset-Pricing Model

Meir Statman, Kenneth L. Fisher, and Deniz Anginer

W

e often admire a stock or disapprove of three-factor model. But affect plays a role in behav-

it when we hear its name even before ioral asset-pricing models, where it is referred to as

we think about its P/E or the growth of “sentiment” or an “expressive set of characteristics.”

its company’s sales. Think of Google Statman (1999) described a behavioral asset-

Inc., General Electric Company, Enron Corpora- pricing model that includes utilitarian factors, such

tion. Like houses, cars, watches, and many other as risk, but also expressive or affect characteristics,

products, stocks exude “affect.” Affect is the spe- such as the negative affect of tobacco and other “sin”

cific quality of “goodness” or “badness,” and companies or the positive affect of prestigious hedge

Slovic, Finucane, Peters, and MacGregor (2002) funds. He illustrated the model with an analogy to

described it as a feeling that occurs rapidly and the watch market. A $10,000 Rolex watch and a $50

Timex watch have approximately the same utilitar-

automatically, often without consciousness. Zajonc

ian qualities; both watches display the same time.

(1980), an early proponent of the importance of

But Rolex buyers are willing to pay an extra $9,950

affect in decision making, wrote, “We do not just over the price of the Timex because the affect of a

see house: We see a handsome house, an ugly Rolex—consisting of prestige and, perhaps,

house, or a pretentious house” (p. 154) and added: beauty—is more positive than that of a Timex.

We sometimes delude ourselves that we pro- This article is about asset-pricing models, not

ceed in a rational manner and weigh all the market efficiency, although the two are interre-

pros and cons of the various alternatives. But lated. We found that the returns of stocks admired

this is rarely the case. Quite often “I decided in by respondents to the Fortune surveys are lower

favor of X” is no more than “I liked X.” We buy than the returns of stocks of less admired compa-

the cars we “like,” choose the jobs and houses nies, but we do not claim to have uncovered a new

we find “attractive,” and then justify these anomaly. Rather, we hypothesize that affect plays

choices by various reasons. (p. 155) a role in pricing models of financial assets. In par-

Kahneman (2002) described the affect heuristic in ticular, we hypothesize that affect underlies the

his Nobel Prize lecture as “probably the most market-capitalization and book-to-market factors

important development in the study of judgment of three-factor models. We present evidence consis-

heuristics in the last decades.” tent with this hypothesis and discuss the role of

affect in a behavioral asset-pricing model.

Affect, embedded in location, brand, and con-

notation, plays a role in the pricing models for

houses, cars, and watches. But according to stan- Affect in Pricing Models

dard financial theory, affect plays no role in the Considerable evidence suggests that affect plays a

pricing of financial assets. In the capital asset pricing role in pricing. For example, Hsee (1998) presented

model (CAPM) and the three-factor model (Fama to subjects pictures of two ice-cream cups, depicted

in Figure 1. The cup on the left contains 8 ounces of

and French 1992), expected returns are determined

ice cream, but its affect is negative because the

by risk alone. Beta measures risk in the CAPM, and

serving seems stingy in its 10-oz. cup. In contrast,

according to Fama and French, market capitaliza-

the affect of the 7 oz. of ice cream on the right is

tion and book-to-market ratio measure risk in the positive because it is overflowing its 5-oz. cup.

Hsee found that subjects who saw only the 5-oz.

cup overflowing with the 7 oz. of ice cream were

Meir Statman is Glenn Klimek Professor of Finance at willing to pay more for it than subjects who saw

Santa Clara University, California. Kenneth L. Fisher is only the 10-oz. cup stingily filled with 8 oz. of ice

founder, chairman, and CEO of Fisher Investments, Inc. cream. But subjects who saw the two cups side by

Deniz Anginer is a doctoral student at the University of side were willing to pay a higher price for the cup

Michigan, Ann Arbor. with 8 oz. of ice cream.

20 www.cfapubs.org ©2008, CFA Institute

Affect in a Behavioral Asset-Pricing Model

Figure 1. Affect in the Pricing of Ice Cream

10 oz.

8 oz.

7 oz.

5 oz.

Source: Hsee (1998).

Affect is an emotion that, like all emotions, is task—memorizing a two-digit number. Others

grounded in evolutionary psychology. Cosmides were assigned a higher-stress task—memorizing a

and Tooby (2000) wrote that evolutionary psychol- seven-digit number. Next, each subject was asked

ogy is a theoretical framework that combines prin- to go to another room. On their way, each could

ciples and results from evolutionary biology, choose chocolate cake or fruit salad. Shiv and

cognitive science, anthropology, and neuroscience Fedorikhin found that subjects who were under the

to describe human behavior, and they described greater stress of memorizing the seven-digit num-

emotions as programs whose function is to direct ber were more likely to be guided by affect and

the activities and interactions of subprograms, choose the chocolate cake over the fruit salad.

including those of perception, attention, goal Stocks are notoriously complex, and evaluat-

choice, and physiological reactions. Cosmides and ing them is stressful. Are shares of Google at $700

Tooby illustrated the idea with the emotion of fear, per share better investments than shares of General

such as when stalked by predators: Motors Corporation at $20 per share? Faced with

Goals and motivational weightings change; such tasks, investors may try to overcome the pull

safety becomes a far higher priority. . . . You are of affect through a systematic examination of rele-

no longer hungry; you cease to think about vant information, but affect still exerts its power.

how to charm a potential mate. . . . adrenalin Companies with internet-related dot-com names

spikes. . . . (pp. 93–94) had positive affect in the boom years of the late

Emotions prevent us from being lost in 1990s, and Cooper, Dimitrov, and Rau (2001) found

thought when it is time to act. But sometimes, that companies that changed their names to dot-

emotions subvert good thinking. Reliance on emo- com names had positive abnormal returns on the

tions increases with the complexity of information order of 74 percent in the 10 days surrounding the

and with stress. Shiv and Fedorikhin (1999) day on which the change was announced—even

described an experiment in which subjects chose when nothing about the business had changed.

between a piece of chocolate cake, which had Companies with dot-com names acquired negative

intense positive affect but was inferior from a cog- affect in the bust years of the early 2000s, and

nitive perspective, and a serving of fruit salad, with Cooper, Khorana, Osobov, Patel, and Rau (2005)

its less positive affect but superiority from a cogni- found that companies that changed from a dot-com

tive perspective. Subjects were brought to a room, name to a conventional name during that time

one at a time. Some were assigned a low-stress experienced positive abnormal returns.

March/April 2008 www.cfapubs.org 21

Financial Analysts Journal

These findings illustrate “integral affect”— factor model presents expected returns as a func-

affect that is associated with the characteristics of a tion of beta (a measure of objective risk) but also as

particular object, such as a stock. “Incidental affect” a function of market capitalization and BV/MV.

arises not from an object but from an unrelated What do market capitalization and BV/MV repre-

event. For example, Welch (1999) induced fear in sent? Fama and French argued that they represent

subjects by showing them two minutes of Stanley objective risk, but much of the evidence is inconsis-

Kubrick’s movie The Shining. He found that the tent with their argument. For example, Lakon-

induced fear carried over beyond the movie, increas- ishok, Shleifer, and Vishny (1994) found that value

ing subjects’ risk aversion in choices unrelated to the stocks (defined as having high BV/MV) outper-

movie. In the context of stocks, Hirshleifer and formed growth stocks (those with low BV/MV) in

Shumway (2003) found that the positive incidental three out of four recessions from 1963 through 1990,

affect of sunny days brought high stock returns and which is not consistent with the view that value

Edmans, Garcia, and Norli (2007) found that the stocks are riskier. Similarly, Skinner and Sloan

negative incidental affect of soccer losses brought (2002) found that the relatively high returns of

low stock returns. value stocks are not a result of their higher risk.

The immediate effect of an increase in affect is Rather, value stocks’ returns are a result of large

an increase in stock prices, but higher stock prices declines in the prices of growth stocks in response

set the stage for lower future returns. This is illus- to negative earnings surprises. For the study of the

trated in the returns of stocks shunned by “socially relationship between affect and stock returns, we

responsible” investors. These investors regularly first turned to Fortune magazine.

exclude from their portfolios stocks of companies

engaged in selling tobacco, alcohol, military prod- Performance of Fortune Admired

ucts, or firearms, in the gaming industry, or in

nuclear operations. Hong and Kacperczyk (2007) and Spurned

found that stocks associated with tobacco, alcohol, Fortune has been publishing the results of an annual

and gaming operations had high returns relative to survey of company reputations since 1983. The sur-

the stocks of other companies. Similarly, Statman vey that was published in March 2007 included 587

and Glushkov (2008) found that stocks of companies U.S. companies. Fortune asked more than 10,000

associated with tobacco, alcohol, gaming, firearms, senior executives, directors, and security analysts

military sales, and nuclear operations had high who responded to the survey to rate, using a scale

returns relative to stocks of other companies. In this of 0 (poor) to 10 (excellent), the 10 largest compa-

study, we hypothesized, analogously, that the neg- nies in their industries based on eight attributes of

ative affect of companies ranked low in Fortune’s reputation. We focused on the attribute of long-

survey of Most Admired companies is accompanied term investment value (LTIV) because it reflects

by higher stock returns. perceptions of respondents about company stocks

that incorporate the respondents’ expectations for

Market Efficiency and Asset- the companies’ returns and risk.

Consider two portfolios constructed by For-

Pricing Models tune scores, each consisting of an equally weighted

Fama (1970) noted that market efficiency per se is half of the Fortune stocks. The Admired portfolio

not testable. Market efficiency must be tested jointly contains the stocks of companies with the highest

with an asset-pricing model, such as the CAPM or LTIV scores, and the Spurned portfolio contains the

the Fama–French three-factor model. For example, stocks with the lowest scores. If Fortune respon-

the excess returns relative to the CAPM of small-cap dents believe that the stock market is efficient, they

stocks and stocks with high ratios of book value of should rate all stocks equally on LTIV because in

equity to market value of equity (BV/MV) might an efficient market, there are no stocks with high

indicate that the market is not efficient or that the LTIV and no stocks with low LTIV. If Fortune

CAPM is a bad model of expected returns. But when respondents believe that the stock market is ineffi-

it comes to tests of market efficiency, the CAPM is cient and that they can identify correctly the stocks

quite different from the three-factor model. with higher LTIV, they should expect the stocks of

The CAPM presents expected returns as a companies with high LTIV to do better than the

function of objective risk. The objective measure of stocks of companies with low LTIV. But Fortune

investment risk is based on the probability distri- respondents rated some stocks high on LTIV and

bution of investment outcomes, usually equated other stocks low because the respondents were

with the variance of a portfolio and the beta of a influenced by the positive affect of the first group

security within a portfolio. In contrast, the three- and the negative affect of the other.

22 www.cfapubs.org ©2008, CFA Institute

Affect in a Behavioral Asset-Pricing Model

To investigate whether Fortune respondents’ the industry-adjusted score of a company as the

ratings correspond to either an efficient or an inef- difference between its score in a given survey and

ficient market model, we constructed Admired and the mean score of companies in its industry. The

Spurned portfolios and followed their fortunes. mean scores of companies in some industries were

The portfolios were constructed as of 30 September found to be higher, on average, than those of com-

1982 on the basis of the Fortune survey published panies in other industries; for example, the mean

subsequently in 1983 (because Fortune surveys are score for companies in the communications indus-

completed by respondents around 30 September of try was 6.43 versus a score of 5.14 for the coal

the year before they are published). mining industry.

Fortune does not define how long “long term” Table 1 provides the returns to the portfolios

is. We investigated horizons of two, three, and four

as reconstituted every two, three, or four years and

years. For the two-year horizon, we reconstituted

measured in a CAPM analysis. The returns of the

each portfolio on 30 September every two years, so

Spurned portfolios exceed those of the Admired

the first reconstitution was based on the survey

conducted in 1984 and published in 1985. We con- portfolios. For example, when the portfolios were

structed portfolios similarly for the three- and four- rebalanced every four years, the mean annualized

year horizons. Fortunately, the overall 24-year return of the Spurned portfolio is 19.7 percent—

period, 30 September 1982 to 30 September 2006, is higher than the mean annualized return of the

divisible by 2, 3, and 4, so each time period was Admired portfolio by 4.6 percentage points.

included in each analysis. The advantage of the Spurned portfolios over

Admired and Spurned portfolios were based the Admired portfolios remained intact when we

on companies’ industry-adjusted scores. We calcu- assessed them by using the CAPM. The alphas of

lated the mean score of companies in each industry the Spurned portfolios as measured in the CAPM

in the surveys published in 1983–2007 and defined are consistently higher than those of the Admired

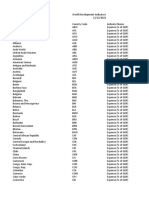

Table 1. CAPM-Based Performance of Admired and Spurned Portfolios,

30 September 1982 to 30 September 2006

(t-statistics in parentheses)

Difference

Measure Spurned Admired (percentage points)

Portfolios reconstituted every two years

Mean annualized return 18.99% 15.65% 3.34

Annualized alpha 4.37% 1.94% 2.43

(2.43)** (1.67)*

Beta 1.04 0.98 0.06

(30.84)*** (44.82)***

Adjusted R2 0.76 0.87

Portfolios reconstituted every three years

Mean annualized return 17.83% 16.02% 1.81

Annualized alpha 3.81% 2.29% 1.52

(2.17)** (1.95)*

Beta 1.03 1.00 0.04

(31.24)*** (44.58)***

Adjusted R2 0.77 0.87

Portfolios reconstituted every four years

Mean annualized return 19.72% 15.12% 4.60

Annualized alpha 4.89% 1.57% 3.32

(2.82)*** (1.31)

Beta 1.03 0.98 0.05

(31.66)*** (42.96)***

Adjusted R2 0.77 0.86

Notes: Portfolios are equally weighted. Analysis is of monthly data.

*Statistically significant at the 10 percent level.

**Statistically significant at the 5 percent level.

***Statistically significant at the 1 percent level.

March/April 2008 www.cfapubs.org 23

Financial Analysts Journal

portfolios. For example, the annualized alpha of the always positive but are statistically significant only

Spurned portfolio when portfolios were reconsti- for the three-year reconstitution interval.1

tuted every four years is 4.89 percent whereas it is A four-factor analysis (consisting of the origi-

only 1.57 percent for the Admired portfolio. The nal three Fama–French factors plus a momentum

alphas of the Spurned portfolios are positive and factor) of the portfolios is presented in Table 2. It

statistically significant for all reconstitution inter- shows that companies in the Spurned portfolios

vals. The alphas of the Admired portfolios are had higher objective risk than companies in the

Table 2. Four-Factor-Based Performance of Admired and Spurned

Portfolios, 30 September 1982 to 30 September 2006

(t-statistics in parentheses)

Difference

Measure Spurned Admired (percentage points)

Portfolios reconstituted every two years

Annualized alpha 1.90% 0.35% 1.55

(1.55) (0.36)

Beta 1.18 1.09 0.09

(45.75)*** (53.61)***

Small minus big 0.36 –0.05 0.41

(11.25)*** (–1.99)***

Value minus growth 0.59 0.29 0.29

(15.26)*** (9.66)***

Momentum –0.24 –0.09 –0.15

(–10.60)*** (–4.95)***

Adjusted R2 0.90 0.92

Portfolios reconstituted every three years

Annualized alpha 1.29% 0.81% 0.48

(1.04) (0.83)

Beta 1.17 1.10 0.06

(44.60)*** (54.08)***

Small minus big 0.35 –0.04 0.39

(10.81)*** (–1.46)

Value minus growth 0.57 0.30 0.26

(14.54)*** (9.95)***

Momentum –0.22 –0.11 –0.11

(–9.53)*** (–5.94)***

Adjusted R2 0.89 0.92

Portfolios reconstituted every four years

Annualized alpha 2.07% –0.02% 2.09

(1.64) (–0.03)

Beta 1.17 1.09 0.08

(44.18)*** (52.01)***

Small minus big 0.32 –0.02 0.34

(9.70)*** (–0.96)

Value minus growth 0.57 0.32 0.25

(14.42)*** (10.11)***

Momentum –0.19 –0.11 –0.09

(–8.25)*** (–5.72)***

Adjusted R2 0.89 0.92

Notes: Portfolios are equally weighted. Analysis is of monthly data. Momentum is the difference between

the return of a portfolio containing stocks with high returns over the previous 2–12 months and a portfolio

containing stocks with low returns over the same period.

*Statistically significant at the 10 percent level.

**Statistically significant at the 5 percent level.

***Statistically significant at the 1 percent level.

24 www.cfapubs.org ©2008, CFA Institute

Affect in a Behavioral Asset-Pricing Model

Admired portfolios. Betas in the Spurned portfolios and also when subjective risk is high. High subjective

are consistently higher than betas in the Admired risk comes with negative affect, and low subjective

portfolios. The four-factor analysis also shows that risk comes with positive affect. Subjective risk is not

the characteristics of small cap, value, and poor always the same as objective risk. For example,

past returns (low short-term momentum) are asso- Ganzach (2000) presented a list of 30 international

ciated with the Spurned portfolios. The tilts of the stock markets to two groups of subjects. One group

Spurned portfolios toward small cap and value are was asked to judge the expected returns of the mar-

consistently greater than those of the Admired ket portfolios of each stock market; the other group

portfolios, and the momentum returns of the was asked to judge the risk of these market portfo-

Spurned portfolios are consistently lower than lios. A CAPM-like asset-pricing model based

those of the Admired portfolios. entirely on objective risk would lead us to expect a

Additional characteristics of the portfolios are positive correlation between assessments of risk

presented in Table 3. Companies in the Spurned and assessments of expected returns, but Ganzach

portfolios during the period had higher ratios of found a negative correlation: Markets with high

earnings to price (E/P), higher ratios of cash flow to expected returns were perceived to have low risk.

price (CF/P), lower past sales and earnings growth, The negative relationship between subjective

and lower returns on assets (ROAs). risk and expected returns in Ganzach’s study is

The question is what these results say about the one example of a generally negative relationship

asset-pricing models that we use. between subjective risk and perceived benefits.

Slovic et al. (2002) attributed that negative rela-

Table 3. Characteristics of Stocks in Admired tionship to affect. When affect is positive, benefits

and Spurned Portfolios: Mean Values are judged high and risk is judged low. And when

as of 30 September of Each Year, affect is negative, benefits are judged low and risk

1982–2005 is judged high. We found similar results in our

experiments.

Measure Admired Spurned

In the first experiment, conducted in May

Return in previous year (%) 21.57 11.06 2007, we presented investors who were high-net-

Return in previous three years (%) 81.24 38.47 worth clients of an investment firm with only the

Return in previous five years (%) 169.44 79.50 names and industries of the 210 companies from

Market capitalization ($ millions) 19,327 5,853 the Fortune 2007 survey.2 We asked the investors

BV/MV 0.491 0.751

to score the companies on a 10-point scale ranging

E/P 0.066 0.079

from “bad” to “good.” The questionnaire said,

CF/P 0.103 0.136

“Look at the name of the company and its industry

Sales growth 0.101 0.035

and quickly rate the feeling associated with it on a

Earnings growth 0.127 0.052

scale ranging from bad to good. Don’t spend time

ROA 0.158 0.125

thinking about the rating. Just go with your quick,

Beta 0.980 1.040

intuitive feeling.” The affect score of a company is

Notes: “Previous year(s)” returns are the returns during the 12, the mean score assigned to it by the surveyed

36, and 60 months prior to the end of September of the portfolio

formation year. Market capitalization and price are as of the end investors. As Figure 2 shows, we found a positive

of September of portfolio formation year. Book value of equity and statistically significant relationship between

(defined as in Davis, Fama, and French 2000) is as of the end of affect scores and Fortune scores.

the fiscal year prior to portfolio formation. Earnings for the fiscal

In the second experiment, conducted in July

year are prior to portfolio formation. Cash flow (earnings +

depreciation) for the fiscal year is prior to portfolio formation. 2007, we presented to another group of investors

E/P and CF/P were set to zero if they were negative. Sales the names and industries of the same 210 compa-

growth = log change in sales for the two fiscal years prior to the nies from the Fortune 2007 survey. One group of

end of September of the portfolio formation year. Earnings

growth = log change in earnings for the two fiscal years prior to

investors was asked to rate the future return of each

the end of September of the portfolio formation year. ROA was stock on a 10-point scale ranging from low to high.

calculated as the ratio of operating income before depreciation Another group of investors was asked to rate the

to total assets at the end of the fiscal year prior to portfolio risk of each stock on the same scale.3 The risk and

formation. Betas are from 60 monthly returns (and minimum 36

months) prior to the end of portfolio formation year. return scores of companies were the mean scores

assigned to them by the surveyed investors.

If investors’ assessments of risk reflect objec-

Affect in a Behavioral Asset- tive risk alone, we should find a positive correlation

between the risk scores and the return scores that

Pricing Model they assigned to companies. As seen in Figure 3,

In the behavioral asset-pricing model outlined here, however, the correlation between the two was neg-

expected returns are high when objective risk is high ative: High return scores corresponded to low risk

March/April 2008 www.cfapubs.org 25

Financial Analysts Journal

Figure 2. Relationship between Affect Scores with high return scores. The coefficient on the

and Fortune Scores return scores is positive and statistically significant.

Similarly, in a regression of Fortune scores on risk

Fortune Score scores, shown in Figure 5, we found high Fortune

10 ratings to be associated with low risk scores. The

9 coefficient on the risk scores is negative and statis-

8 tically significant.

7 Objective risk measured by beta and subjective

6 risk measured by affect are two factors in the behav-

5 ioral asset-pricing model. But they are not the only

4 factors. Short-term momentum is an especially

3 interesting factor because its rationale is distinct

2 from the rationale of affect.

1

0

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Figure 4. Relationship between Expected-

Affect Score Return Scores and Fortune Scores

Fortune Score

Notes: Number of stocks = 210. Fortune score = 2.13 + 0.60(Affect

score), with a t-statistic of 6.6; statistically significant at the 10

1 percent level. R2 = 0.17. 9

8

7

Figure 3. Relationship between Expected- 6

Return Scores and Risk Scores 5

4

Expected-Return Score

3

9

2

8 1

7 0

6 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

5 Expected-Return Score

4 Notes: Number of stocks = 210. Fortune score = 2.7 + 0.6(Expected-

3 return score), with a t-statistic of 6.8; statistically significant at the

1 percent level. R2 = 0.18.

2

1

0 Figure 5. Relationship between Risk Scores

3 4 5 6 7 8 and Fortune Scores

Risk Score

Fortune Score

Notes: Number of stocks = 210. Expected-return score = 8.4 – 0.4 10

(Risk score), with a t-statistic of –7.2; statistically significant at 9

the 1 percent level. R2 = 0.18.

8

7

6

scores. This negative correlation indicates that

5

investors’ assessments of risk reflect subjective risk 4

associated with affect. Positive affect creates a halo 3

over stocks. Stocks with positive affect are assessed 2

to be high as to future returns and low in risk, and 1

stocks with negative affect are assessed to be low 0

in future returns and high in risk. 3 4 5 6 7 8

We also found a link between return scores, Risk Score

risk scores, and Fortune scores. In a regression of Notes: Number of stocks = 210. Fortune score = 8.0 – 0.3(Risk score),

Fortune scores on return scores, shown in Figure 4, with a t-statistic of –3.3; statistically significant at the 1 percent

we found that high Fortune ratings are associated level. R2 = 0.05.

26 www.cfapubs.org ©2008, CFA Institute

Affect in a Behavioral Asset-Pricing Model

High short-term (12-month) momentum is Conclusion

positively correlated with affect, yet it is generally

All asset-pricing models, whether of securities, cars,

associated with high returns (Jegadeesh and Titman

or watches, are versions of the basic model in which

1993). In contrast, large market capitalization is also

prices are determined by the intersection of demand

positively correlated with affect but is generally

and supply. The demand and supply functions

associated with low returns. These relationships reflect the preferences of consumers and producers.

suggest that the relationship between short-term

The demand and supply structure is evident in

momentum and subsequent high returns might be

the CAPM. In that model, investors on both the

the result of something other than affect. Indeed,

demand and supply sides prefer mean–variance-

the association between short-term momentum efficient portfolios, and the aggregation of their

and returns was attributed by Grinblatt and Han preferences yields an asset-pricing model in which

(2005) to the “disposition effect,” as described by expected returns of securities vary by beta. The

Shefrin and Statman (1995), and was attributed by demand and supply structure is not nearly as evi-

Sias (2007) to trading by institutional investors. dent in the Fama and French three-factor asset-

pricing model. Market capitalization and BV/MV

Investor Preferences and Stock were associated with anomalies relative to the

CAPM long before the debut of the three-factor

Returns model, but the argument that size and BV/MV

The road from the perception that admired compa- proxy for risk is not fully supported by the evidence.

nies offer both high expected returns and low risk The purpose of this article was to help link

to the low realized returns of such stocks is not asset-pricing models to the preferences of inves-

straight, as explained by Shefrin and Statman tors. We outlined a behavioral asset-pricing model

(1995) and by Pontiff (2006). Suppose typical inves- in which expected returns are high when objective

tors prefer admired companies that they perceive risk is high and also when subjective risk is high.

as having both high expected returns and low risk. High subjective risk comes with negative affect,

Surely, some investors, however, are contrarians and low subjective risk comes with positive affect.

who are aware of the preferences of typical inves- The study described here used the preferences

tors and seek to capitalize on them by favoring of investors as reflected in surveys conducted by

stocks of spurned companies. Would arbitrage by Fortune magazine during 1983–2006 and in addi-

these contrarians not nullify the effect of the typical tional surveys that we conducted in 2007. We found

investors on stock returns? If the effects of typical that the returns of admired stocks, those highly

investors on stock returns are nullified by arbitrage, rated by the Fortune respondents, were lower than

then subjective risk stemming from affect plays no the returns of spurned stocks, those rated low. This

role in the asset-pricing model. If arbitrage is result is consistent with the hypothesis that stocks

incomplete, however, subjective risk does play a with negative affect have high subjective risk and

role in the asset-pricing model. their extra returns compensate for that risk. We also

In considering arbitrage and the likelihood found that market capitalization and BV/MV are

that it nullifies the effects of the preferences of correlated with affect, and we argued that those

typical investors on stock returns, keep in mind that factors proxy for affect.

no perfect (risk-free) arbitrage is possible. As some We found additional support for the hypothe-

hedge funds and other unlucky investors found sis in the surveys that we conducted. Respondents

out, price gaps that are likely to close over a long in these surveys rated companies as if they believe

period may widen farther over a shorter period. that the stocks with high expected returns also have

Risk makes arbitrage imperfect: Imagine a group of low risk, and respondents perceived the stocks of

contrarians who know that the stocks of spurned companies admired by Fortune respondents as hav-

companies have high expected returns relative to ing both high expected returns and low risk.

their objective risk. It is optimal for the contrarians The behavioral asset-pricing model outlined

to increase their holdings of stocks of spurned com- here is not “superior” to the three- or four-factor

panies, but as the amount devoted to such stocks models. Indeed, the factor models are behavioral

increases, the portfolios of the contrarians become models under their standard-finance skins. The

less diversified and they take on more idiosyncratic affect factor in the behavioral asset-pricing model

risk. The increase in portfolio risk leads contrarians elucidates the rationale underlying the effects of

to limit the amount allocated to spurned stocks and, the market-cap and BV/MV factors of the three-

in so doing, to limit their effect on stock returns. factor model.

March/April 2008 www.cfapubs.org 27

Financial Analysts Journal

The number of factors in a full model is likely model. Social responsibility is one source of

to grow to include factors, such as liquidity, that positive affect. Prestige is another.

are not included in the behavioral model or in the

three- and four-factor models. Moreover, affect has We would like to thank Ramie Fernandez, Hersh Shefrin,

several distinct sources, and these sources may and Paul Slovic.

play distinct roles in a behavioral asset-pricing This article qualifies for 0.5 CE credit.

Notes

1. Part of the magnitude of the CAPM alphas in the Spurned 2. We sent the questionnaire to 900 investors in three groups

and Admired portfolios is a result of equal weighting of 300 each. The list of stocks for each group consisted of 70

because equal weighting creates a small-cap tilt. Neverthe- of the 210 companies in the survey. We received 170 com-

less, when value weighting was used, the CAPM alphas pleted questionnaires from the first group, 162 from the

were lower in the Spurned and Admired portfolios than in second, and 169 from the third, for a total of 501.

the equally weighted portfolios but the alphas of the 3. We sent the questionnaire to 1,800 investors in six groups

Spurned portfolios remained consistently higher than those of 300 each. The list of stocks for each group consisted of 70

of the Admired portfolios. When value weighting was used, of the 210 companies in the survey. Three groups received

the alphas of the Spurned portfolios were positive and sta- the return version of the questionnaire, and three received

tistically significant with the exception of the portfolio recon- the risk version. We received 94, 91, and 94 completed

stituted every two years. In contrast, none of the alphas of questionnaires for the return versions and 134, 74, and 83

the Admired portfolios was statistically significant. for the risk version, for a total of 570.

References

Cooper, Michael J., Orlin Dimitrov, and P. Raghavendra Rau. Hirshleifer, David, and Tyler Shumway. 2003. “Good Day

2001. “A Rose.com by Any Other Name.” Journal of Finance, Sunshine: Stock Returns and the Weather.” Journal of Finance,

vol. 56, no. 6 (December):2371–2388. vol. 58, no. 3 (June):1009–1032.

Cooper, Michael J., Ajay Khorana, Igor Osobov, Ajay Patel, and Hong, Harrison, and Marcin Kacperczyk. 2007. “The Price of

P. Raghavendra Rau. 2005. “Managerial Actions in Response to Sin: The Effects of Social Norms on the Market.” Working paper,

a Market Downturn: Valuation Effects of Name Changes in the Princeton University.

Dot.com Decline.” Journal of Corporate Finance, vol. 11, no. 1–2

Hsee, C.K. 1998. “Less Is Better: When Low-Value Options Are

(March):319–335.

Judged More Highly Than High-Value Options.” Journal of

Cosmides, Leda, and John Tooby. 2000. “Evolutionary Psychol- Behavioral Decision Making, vol. 11, no. 2 (June):107–121.

ogy and the Emotions.” In Handbook of Emotions. 2nd ed. Edited

by Michael Lewis and Jeannette M. Haviland-Jones. New York: Jegadeesh, Narasimham, and Sheridan Titman. 1993. “Returns to

Guilford Press. Buying Winners and Selling Losers: Implications for Stock

Market Efficiency.” Journal of Finance, vol. 48, no. 1 (March):65–91.

Davis, J.L., E.F. Fama, and K.R. French. 2000. “Characteristics,

Covariances, and Average Returns: 1929 to 1997.” Journal of Kahneman, Daniel. 2002. “Maps of Bounded Rationality: A

Finance, vol. 55, no. 1 (February):389–406. Perspective on Intuitive Judgment and Choice.” Nobel Prize

lecture (8 December): http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/

Edmans, Alex, D. Garcia, and O. Norli. 2007. “Sports Senti-

economics/laureates/2002/kahneman-lecture.html.

ment and Stock Returns.” Journal of Finance, vol. 62, no. 4

(August):1967–1998. Lakonishok, Josef, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. 1994.

“Contrarian Investment, Extrapolation, and Risk.” Journal of

Fama, Eugene. 1970. “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of

Theory and Empirical Work.” Journal of Finance, vol. 25, no. 2 Finance, vol. 49, no. 5 (December):1541–1578.

(May):383–417. Pontiff, Jeffrey. 2006. “Costly Arbitrage and the Myth of

Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French. 1992. “The Cross- Idiosyncratic Risk.” Journal of Accounting and Economics, vol. 42,

Section of Expected Stock Returns.” Journal of Finance, vol. 47, no. 1–2 (October):35–52.

no. 2 (June):427–465. Shefrin, Hersh, and Meir Statman. 1995. “Making Sense of

Ganzach, Yoav. 2000. “Judging Risk and Return of Financial Beta, Size, and Book-to-Market.” Journal of Portfolio Manage-

Assets.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, ment, vol. 21, no. 2 (Winter):26–34.

vol. 83, no. 2 (November):353–370. Shiv, Baba, and Alexander Fedorikhin. 1999. “Heart and Mind

Grinblatt, Mark, and Bing Han. 2005. “Prospect Theory, Mental in Conflict: The Interplay of Affect and Cognition in Consumer

Accounting, and Momentum.” Journal of Financial Economics, Decision Making.” Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 26, no. 3

vol. 78, no. 2 (November):311–339. (December):278–292.

28 www.cfapubs.org ©2008, CFA Institute

Affect in a Behavioral Asset-Pricing Model

Sias, Richard. 2007. “Causes and Seasonality of Momentum Statman, Meir. 1999. “Behavioral Finance: Past Battles and

Profits.” Financial Analysts Journal, vol. 63, no. 2 (March/ Future Engagements.” Financial Analysts Journal, vol. 55, no. 6

April):48–54. (November/December):18–27.

Skinner, Douglas J., and Richard G. Sloan. 2002. “Earnings Statman, Meir, and Denys Glushkov. 2008. “The Wages of Social

Surprises, Growth Expectations, and Stock Returns or Don't Let Responsibility.” Working paper, Santa Clara University.

an Earnings Torpedo Sink Your Portfolio.” Review of Accounting Welch, Ned. 1999. “The Heat of the Moment.” Doctoral

Studies, vol. 7, no. 2–3 (June–September):289–312. dissertation, Department of Social and Decision Sciences,

Slovic, Paul, Melissa Finucane, Ellen Peters, and Donald G. Carnegie Mellon University.

MacGregor. 2002. “The Affect Heuristic.” In Heuristics and Zajonc, R.B. 1980. “Feeling and Thinking: Preferences Need

Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment. Edited by Thomas No Inferences.” The American Psychologist, vol. 35, no. 2

Gilovich, Dale Griffin, and Daniel Kahneman. New York: (February):151–175.

Cambridge University Press.

[ADVERTISEMENT]

March/April 2008 www.cfapubs.org 29

You might also like

- The Seven Signs of Ethical Collapse: How to Spot Moral Meltdowns in Companies... Before It's Too LateFrom EverandThe Seven Signs of Ethical Collapse: How to Spot Moral Meltdowns in Companies... Before It's Too LateNo ratings yet

- Great by Choice: Uncertainty, Chaos, and Luck--Why Some Thrive Despite Them AllFrom EverandGreat by Choice: Uncertainty, Chaos, and Luck--Why Some Thrive Despite Them AllRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (120)

- DR York - The Eyes Tunnel Vision To The SoulDocument11 pagesDR York - The Eyes Tunnel Vision To The Soulsean lee92% (49)

- Arindam Bandyopadhyay - Basic Statistics For Risk Management in Banks and Financial Institutions-Oxford University Press (2022)Document321 pagesArindam Bandyopadhyay - Basic Statistics For Risk Management in Banks and Financial Institutions-Oxford University Press (2022)Deb100% (1)

- Drexel 10 Yr RetrospectiveDocument41 pagesDrexel 10 Yr RetrospectiveDan MawsonNo ratings yet

- Economic Instructor ManualDocument35 pagesEconomic Instructor Manualclbrack100% (11)

- Literature Review MonopolyDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Monopolyafduaciuf100% (1)

- Essay Questions Chapters 1 Thru 16Document96 pagesEssay Questions Chapters 1 Thru 16DianaNo ratings yet

- An Agent-Based Macroeconomic Model With Interacting Firms, Socio-Economic Opinion Formation and Optimistic/pessimistic Sales ExpectationsDocument39 pagesAn Agent-Based Macroeconomic Model With Interacting Firms, Socio-Economic Opinion Formation and Optimistic/pessimistic Sales ExpectationsLucas AkioNo ratings yet

- Essay Topics For PsychologyDocument5 pagesEssay Topics For Psychologylwfdwwwhd100% (2)

- Reviewofspulberstheory FirmDocument13 pagesReviewofspulberstheory FirmRotsy Ilon'ny Aina RatsimbarisonNo ratings yet

- 2011 Thinking About The Firm - SpulberDocument15 pages2011 Thinking About The Firm - SpulberNicolas SandovalNo ratings yet

- Thinking About The FirmDocument13 pagesThinking About The FirmMaria CindaNo ratings yet

- Rar 1999 Iss32 GirardDocument3 pagesRar 1999 Iss32 GirardSaad CheemaNo ratings yet

- How Do You Compare - Thoughts On Comparing Well - Mauboussin - On - Strategy - 20060809Document14 pagesHow Do You Compare - Thoughts On Comparing Well - Mauboussin - On - Strategy - 20060809ygd100% (1)

- Multi-Billion Dollar Microcap Opportunity Hiding in A Dark AlleyDocument40 pagesMulti-Billion Dollar Microcap Opportunity Hiding in A Dark Alleybiggercapital100% (1)

- Business Ethics ReflectionDocument4 pagesBusiness Ethics ReflectionRon Edward Medina100% (1)

- SP-Distressed Company ValuationDocument18 pagesSP-Distressed Company ValuationfreahoooNo ratings yet

- t3 Presentation Template (Sharkey)Document45 pagest3 Presentation Template (Sharkey)khmaloneyNo ratings yet

- Extracted Pages From Beyond Greed and Fear Understanding Behavioral Finance and The Psychology of Investing (Shefrin)Document20 pagesExtracted Pages From Beyond Greed and Fear Understanding Behavioral Finance and The Psychology of Investing (Shefrin)ms.aminah.khatumNo ratings yet

- Financial Markets and Firm DynamicsDocument25 pagesFinancial Markets and Firm DynamicsGuru PrasadNo ratings yet

- What Do We Need To FixDocument10 pagesWhat Do We Need To Fixkoyuri7No ratings yet

- Prospect Theory ThesisDocument7 pagesProspect Theory Thesisangelabaxtermanchester100% (1)

- Bankruptcy Essay ThesisDocument7 pagesBankruptcy Essay Thesiskrystalgreenglendale100% (1)

- Ase Analysis-Week 1-LayfieldDocument5 pagesAse Analysis-Week 1-LayfieldKylee LayfieldNo ratings yet

- Ethics of SpeculationDocument10 pagesEthics of SpeculationA BNo ratings yet

- A Rose by Any Other Name - Submitted To Journal of Financial and Economic PracticeDocument20 pagesA Rose by Any Other Name - Submitted To Journal of Financial and Economic PracticedrjcthompsonNo ratings yet

- Coremacroeconomics 3rd Edition Chiang Solutions ManualDocument11 pagesCoremacroeconomics 3rd Edition Chiang Solutions Manualphenicboxironicu9100% (33)

- Disappointment in Decision Making Under UncertaintyDocument28 pagesDisappointment in Decision Making Under UncertaintyMarindah PutriNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Lecture 6 - ConfDocument44 pagesBehavioral Lecture 6 - ConfUdit DhawanNo ratings yet

- Risk AversionDocument15 pagesRisk AversionAntía TejedaNo ratings yet

- January 2012Document4 pagesJanuary 2012edoneyNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Myopia and Loss Aversion On Risk TakingDocument16 pagesThe Effect of Myopia and Loss Aversion On Risk TakingbboyvnNo ratings yet

- Against Abortions EssaysDocument49 pagesAgainst Abortions EssaysafabkedovNo ratings yet

- Journal EntriesDocument4 pagesJournal EntriesmanishNo ratings yet

- Game Theory and ExternalitiesDocument21 pagesGame Theory and ExternalitiesAira Jane YaptangcoNo ratings yet

- Intro To Beh. FinanceDocument35 pagesIntro To Beh. FinanceAnonymous YKmreGjNo ratings yet

- Thinking About The Firm: A Review of Daniel Spulber'sDocument14 pagesThinking About The Firm: A Review of Daniel Spulber'sKara JohnsonNo ratings yet

- GREED1 Is Mostly GreedyDocument24 pagesGREED1 Is Mostly GreedyJimmyChaoNo ratings yet

- Deepwater-A Business Ethics Simulation Game-LibreDocument37 pagesDeepwater-A Business Ethics Simulation Game-Libre007003sNo ratings yet

- Financial Institutions Center: by Franklin Allen 01-04Document25 pagesFinancial Institutions Center: by Franklin Allen 01-04Muhammad Haider AliNo ratings yet

- Theory: of TheDocument69 pagesTheory: of TheJulyanto Candra Dwi CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Culture and Capital StructureDocument37 pagesCulture and Capital Structurekurniasilalahi726No ratings yet

- Illuminas The Convergence of B2b and Consumer MarketingDocument30 pagesIlluminas The Convergence of B2b and Consumer MarketingArslan AzamNo ratings yet

- Prospect Theory and Other TopicsDocument19 pagesProspect Theory and Other Topicskhush preetNo ratings yet

- April 2021 Client LetterDocument5 pagesApril 2021 Client LetteramarNo ratings yet

- Bin There Done That - Us PDFDocument19 pagesBin There Done That - Us PDFaaquibnasirNo ratings yet

- Moral Economy of Speculation - Sandel LectureDocument27 pagesMoral Economy of Speculation - Sandel LecturejaribuzNo ratings yet

- WWW: Click On The Web Surfer Icon To Go To The Pricewaterhousecoopers WebDocument15 pagesWWW: Click On The Web Surfer Icon To Go To The Pricewaterhousecoopers WebvvNo ratings yet

- Edgar Allan Poe EssaysDocument7 pagesEdgar Allan Poe Essaysfz6z1n2p100% (2)

- Interpersonal Communication Essay TopicsDocument7 pagesInterpersonal Communication Essay Topicsezm8kqbt100% (2)

- Case Study: Italian Tax MoresDocument8 pagesCase Study: Italian Tax MoresVictorYoonNo ratings yet

- Rise and Fall of Performance InvestingDocument5 pagesRise and Fall of Performance Investingathompson14No ratings yet

- Rational Actors, Tca, P&aDocument14 pagesRational Actors, Tca, P&aPoonam NaiduNo ratings yet

- Report On: - Buyology Team: - Southwest AirlinesDocument12 pagesReport On: - Buyology Team: - Southwest AirlinesPriya SrivastavNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id2613702 PDFDocument61 pagesSSRN Id2613702 PDFmuhjaerNo ratings yet

- Integrity Management: Muel KapteinDocument10 pagesIntegrity Management: Muel KapteinZaimatul SulfizaNo ratings yet

- Tom Sayer and Construction of ValueDocument21 pagesTom Sayer and Construction of ValueDon QuixoteNo ratings yet

- +++ Boom, Bust, Boom - Internet Company Valuation - From Netscape To GoogleDocument20 pages+++ Boom, Bust, Boom - Internet Company Valuation - From Netscape To GooglePrashanth KumarNo ratings yet

- Great by Choice ΓÇô Thriving in Uncertainty-21-24Document4 pagesGreat by Choice ΓÇô Thriving in Uncertainty-21-24FelipeGame21 2No ratings yet

- Investor's Mental Models: Mental Models Series, #3From EverandInvestor's Mental Models: Mental Models Series, #3Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Effects of Monetary Magnitude (Showing Per Day Pricing)Document11 pagesThe Effects of Monetary Magnitude (Showing Per Day Pricing)Geet YadavNo ratings yet

- Linear Equations in Two VariablesDocument8 pagesLinear Equations in Two VariablesDebNo ratings yet

- PolynomialsDocument4 pagesPolynomialsDebNo ratings yet

- 3.coordinate GeometryDocument12 pages3.coordinate GeometryDebNo ratings yet

- Mock CAT - 06 PDFDocument79 pagesMock CAT - 06 PDFDebNo ratings yet

- 5.introduction To Euclid - S GeometryDocument9 pages5.introduction To Euclid - S GeometryDebNo ratings yet

- Number SystemsDocument5 pagesNumber SystemsDebNo ratings yet

- PPTXDocument10 pagesPPTXDebNo ratings yet

- Mock CAT - 04 PDFDocument78 pagesMock CAT - 04 PDFDebNo ratings yet

- Mock CAT - 05 PDFDocument82 pagesMock CAT - 05 PDFDebNo ratings yet

- Exp (% of GDP)Document63 pagesExp (% of GDP)DebNo ratings yet

- 3-Data ReferencingDocument135 pages3-Data ReferencingDebNo ratings yet

- GST Collection Jan'23Document3 pagesGST Collection Jan'23DebNo ratings yet

- 5 SolverDocument11 pages5 SolverDebNo ratings yet

- Case Study Blinds To GoDocument7 pagesCase Study Blinds To GoDebNo ratings yet

- Fiscal ConsolidationDocument11 pagesFiscal ConsolidationDebNo ratings yet

- FinalDocument2 pagesFinalDebNo ratings yet

- Session4 DateDocument364 pagesSession4 DateDebNo ratings yet

- Sec B Gp8 Blinds To Go PDFDocument12 pagesSec B Gp8 Blinds To Go PDFDebNo ratings yet

- 2021 Bull CAT 05Document60 pages2021 Bull CAT 05DebNo ratings yet

- Book 1Document5 pagesBook 1DebNo ratings yet

- 5-Reporting and Data Visualization-1Document111 pages5-Reporting and Data Visualization-1DebNo ratings yet

- 2021 Bull CAT 04 (New Pattern)Document42 pages2021 Bull CAT 04 (New Pattern)DebNo ratings yet

- 2021 Bull Cat 01Document62 pages2021 Bull Cat 01DebNo ratings yet

- 2021 Bull CAT 02Document56 pages2021 Bull CAT 02DebNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 115.124.43.107 On Wed, 18 Jan 2023 06:19:13 UTCDocument33 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 115.124.43.107 On Wed, 18 Jan 2023 06:19:13 UTCDebNo ratings yet

- American Finance Association, Wiley The Journal of FinanceDocument41 pagesAmerican Finance Association, Wiley The Journal of FinanceDebNo ratings yet

- 2021 Bull CAT 03Document58 pages2021 Bull CAT 03DebNo ratings yet

- Bjerring 1983Document18 pagesBjerring 1983DebNo ratings yet

- FULLTEXT01Document60 pagesFULLTEXT01DebNo ratings yet

- Human BodyDocument27 pagesHuman Bodyvigyanashram100% (2)

- Impact of Poor Nutrition On The Academic PerformanDocument13 pagesImpact of Poor Nutrition On The Academic PerformanVictor UgoslyNo ratings yet

- Strengths of Character and VirtuesDocument45 pagesStrengths of Character and VirtuesPraveen BVSNo ratings yet

- One Paper MCQS Dated: 26-04-2021 For The Preparation Of: Today's Dose of PPSC, SPSC, FPSC, NTS, PTS, General TestsDocument7 pagesOne Paper MCQS Dated: 26-04-2021 For The Preparation Of: Today's Dose of PPSC, SPSC, FPSC, NTS, PTS, General TestsRaja NafeesNo ratings yet

- PowerPoint Presentation Perdev by Haillie and JericDocument15 pagesPowerPoint Presentation Perdev by Haillie and JericTetzie Sumaylo100% (1)

- Description of Prototype Modes-of-Action Related To Repeated Dose ToxicityDocument49 pagesDescription of Prototype Modes-of-Action Related To Repeated Dose ToxicityRoy MarechaNo ratings yet

- Albumin Liquicolor: Photometric Colorimetric Test For Albumin BCG-MethodDocument1 pageAlbumin Liquicolor: Photometric Colorimetric Test For Albumin BCG-MethodMaher100% (1)

- Isolation of Phytochemicals and Biological Activity Studies ON The Bark of Thespesia Populnea LinnDocument10 pagesIsolation of Phytochemicals and Biological Activity Studies ON The Bark of Thespesia Populnea LinnRosu SilviaNo ratings yet

- Nextgen Cropscience LLP - CatalogueDocument8 pagesNextgen Cropscience LLP - CatalogueManavasi R SureshNo ratings yet

- English 7: Using Appropriate Reading Styles For One'S PurposeDocument6 pagesEnglish 7: Using Appropriate Reading Styles For One'S PurposeJodie PortugalNo ratings yet

- Post Traumatic Stress Disorder The Neurobiological Impact of Psychological TraumaDocument17 pagesPost Traumatic Stress Disorder The Neurobiological Impact of Psychological TraumaMariana VilcaNo ratings yet

- Biomedical CompositesDocument20 pagesBiomedical Compositesanh lêNo ratings yet

- Journal AlzheimerDocument10 pagesJournal AlzheimerFaza KeumalasariNo ratings yet

- CRA-W Ra03-04 enDocument116 pagesCRA-W Ra03-04 enThanh MiNo ratings yet

- 057Document80 pages057Gonzalo BoninoNo ratings yet

- How To Read PeopleDocument93 pagesHow To Read PeopleJasminaNo ratings yet

- Bark Splitting On Trees 2012Document2 pagesBark Splitting On Trees 2012johnson12mrNo ratings yet

- Personal CareDocument5 pagesPersonal CarePhoebe Mariano100% (1)

- New Zealand Biology Olympiad 2013Document37 pagesNew Zealand Biology Olympiad 2013Science Olympiad BlogNo ratings yet

- Human Anatomy & Physiology ExpDocument38 pagesHuman Anatomy & Physiology Expbestmadeeasy100% (3)

- Landscape ArchitectureDocument2 pagesLandscape ArchitectureJoy CadornaNo ratings yet

- Pathogens: Fungal Pathogens of Maize Gaining Free Passage Along The Silk RoadDocument16 pagesPathogens: Fungal Pathogens of Maize Gaining Free Passage Along The Silk RoadNyemaigbani VictoryNo ratings yet

- Applied Veterinary Histology PDFDocument2 pagesApplied Veterinary Histology PDFAbdulla Hil KafiNo ratings yet

- Final BrochureDocument2 pagesFinal BrochureChrister de SilvaNo ratings yet

- 05 - EnzymesDocument6 pages05 - EnzymesLissa JacksonNo ratings yet

- Contoh UAS XI MADocument4 pagesContoh UAS XI MAChubbaydillahNo ratings yet

- ChloroplastDocument4 pagesChloroplastEmmanuel DagdagNo ratings yet

- (936BCB0C) The Practice of Prolog (Sterling 1990-10-30)Document331 pages(936BCB0C) The Practice of Prolog (Sterling 1990-10-30)Török ZoltánNo ratings yet