Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Denobile, Kleeman & Zarkos 2014 Investigating The Impacts of Global Education Curriculum On The Values and Attitudes of Secondary Students

Denobile, Kleeman & Zarkos 2014 Investigating The Impacts of Global Education Curriculum On The Values and Attitudes of Secondary Students

Uploaded by

Javier POriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Denobile, Kleeman & Zarkos 2014 Investigating The Impacts of Global Education Curriculum On The Values and Attitudes of Secondary Students

Denobile, Kleeman & Zarkos 2014 Investigating The Impacts of Global Education Curriculum On The Values and Attitudes of Secondary Students

Uploaded by

Javier PCopyright:

Available Formats

Investigating the impacts of Global

Education curriculum on the values and

attitudes of secondary students

Dr John DeNobile, Dr Grant Kleeman, and Ms Anastasia Zarkos

School of Education, Macquarie University

Abstract that focuses on student experiences and the

constructive application of information acquisition

Each year, World Vision and AusAID devote

and imagination to improve the social condition.

substantial resources to their educational

For Freire (1972), schools are places for cultural

programs. These initiatives include the production

reconstruction and that education is a process

and dissemination of Global Education related

of critical awareness that draws on people’s

instructional materials and the provision of

ideas and perceptions to question and challenge

professional learning for teachers. Given the

injustices.

substantial funds involved, it is important that we

evaluate the effectiveness of such initiatives. Are In broad terms, global education reflects these

they for example enhancing students’ knowledge two strands of progressive education. The first

and understanding of global issues? Do they is focused on the development of the individual

have a positive impact on attitudes and values of and the student’s experiences (Dewey, 1916).

students? Do they enhance students’ sense of The other is concerned with creating a more just

self or personal identity? Do they make students and equitable society (Freire, 1972). For authors

more predisposed to support programs that like Dewey and Freire learning is about effecting

seek to alleviate poverty in developing countries? change at the personal and social level (Breithorde

And, do they promote active and informed global & Swiniarski, 1999). Thus global education with

citizenship? The purpose of this study is to its emphasis on self and society can be viewed as

investigate how the study of Global Education a resocialisation approach as argued by Rapoport

impacts student knowledge, understanding, (2013) or reflecting Goodson’s (1990) concept

attitudes and values. The research reported here of curriculum as social construction, in both in

explores student attitudes and values using process and practice.

quantitative data extracted from a total of 521

pre- and post- questionnaires. The authors will

Global Education in Australia

discuss that, despite the anticipated positive effect

of the Global Education program, the results Global education in Australia was established as

revealed an element of intolerance in the students’ a curriculum approach in a national statement

responses. titled Global Perspectives: A statement on global

education for Australian schools, first published

in 2002 (Curriculum Corporation, 2008). Global

Introduction

education can be traced back to the growing

international concern for social and global

Global Education and Education

inequalities in the 1960s and 1970s (Curriculum

Philosophies Corporation, 2008) and the emergence of

Geography provides students with opportunities international studies and development education

to gain knowledge of people and countries beyond (Dyer, 2005; Bliss, 2007; Zhao, Lin, & Hoge 2007;

their personal and local experiences. Adding Fuijkane, 2003).

global education to the curriculum with its

global perspective, examination of contemporary The current Global Perspectives document

global issues, and educating students to be encompasses five key learning areas

global citizens that empathise and understand reflecting themes in global education such as

other people, cultures and countries, involves Interdependence and Globalisation, Identity and

resocialisation of individuals and advancement of Cultural Diversity, Social Justice and Human

social and civic. Rights, Peace Building and Conflict Resolution,

and Sustainable Futures (Curriculum Corporation,

Curriculum as social reconstructivism is central 2008). These learning areas are interdisciplinary

to John Dewey and Paulo Freire’s educational and the objective is to integrate global

philosophy. Dewey (1916) supports curriculum perspectives across the curriculum.

28 GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION VOLUME 27, 2014

A key goal of the Melbourne Declaration on The effectiveness of global education in the USA

Educational Goals for Young Australians has been questioned by a number of researchers

(MCEECDYA, 2008) is that the national curriculum (Lansford, 2002; Merryfield & Kasai, 2004;

enables students to become active and informed Zhao, Lin & Hoge, 2007; Gaudelli & Heilman,

citizens. Although a number of statements in 2009). These authors have raised concerns about

the Melbourne Declaration (MCEECDYA, 2008) students’ rudimentary knowledge and critical

incorporate a focus on global education including capacity to understand complex global issues.

global knowledge, global skills and global studies, Similarly in Canada, research indicates that the

global education is not a key perspective or key implementation of global education was weak

capability. It is however inferred in other initiatives or uneven (Mundy & Manion, 2008) due to low

in the Australian Curriculum (ACARA, 2013) such levels of teacher knowledge in this area. This

as Asia and Australia’s engagement with Asia. was seen as a factor in Canadian youths’ limited

knowledge of global issues.

The overall consensus is that global education

is a good thing for 21st century learning in a Research undertaken in the United Kingdom

global economy. It can be empowering and found that without an opportunity to learn in

transformative in terms of the way in which school about global issues 34 per cent of adults

students view the world (Bliss, 2005a; Dyer, 2005; surveyed (aged 15 years and over) were not

DERC, 2013); it extends students’ understanding interested, engaged or supportive of positive

and acceptance of difference (Gore, 2004) and social action. In comparison, this disengagement

provides opportunities for students to develop reduced significantly to 1 in 10 for those that

positive and responsible values and attitudes and learnt about global issues at school (DEA, 2010).

become active global participants (Curriculum

Corporation, 2008; DERC, 2013). Role of Teacher and School

Buchanan and Harris (2004), Marshall (2007)

Some Issues Relating to Global Education and Bourn and Hunt (2011) note the development

in Canada, UK and USA of a global perspective in UK schools was linked

Despite global education’s presence in the to local stimuli associated with multicultural

education discourse in Australia, the UK and communities, languages spoken at school, and

USA a number of authors (Zhao, Lin, & Hoge teacher commitment. This reflects Dyer’s (2005)

2007; Hicks, 2003; Bourn & Hunt 2011) have view that the quality of global education is

found that there is a lack of specific research on dependent on the teacher and the learning space

the effectiveness of the various global education created by the teacher.

programs. One of the reasons for this absence of Teachers’ experiences, knowledge and critical

research may be due to how global education as a capacity influenced the teaching of complex global

concept is viewed and applied. issues (Merryfield & Kasai, 2004; Zhao, Lin, &

Hoge, 2007). This is reaffirmed in research by

This is compounded by the absence of a universal

Dyer (2005) Bliss (2005b, 2005c, 2007), and

definition (Bliss, 2005a); the nuanced meanings

Gallavan (2008) revealing that factors such as

of global education (Dyer, 2005); and the many

age, life experiences, bias, prejudices and subject

terms used by educators including global

discipline may contribute. Boon (2011), however,

dimension, global citizenship, development

argues that more research needs to be conducted

education, and global education (DERC, 2013;

to gain a better understanding of influences that

Hicks, 2003). A further dilemma identified by

shape pre-service teachers’ beliefs, values and

a number of authors (Bliss 2005a; Dyer, 2005;

ethics.

Hicks, 2003) is the existence of related fields such

as peace education, environmental education, Many teachers report that they feel inadequately

development education and sustainable education trained to teach global issues (Merryfield & Kasai,

that have separate identities but are part of global 2004). Not surprisingly research confirms the

education. importance of teacher training in addressing

global education knowledge and understanding

Generally, there are common elements in the

(Donnelly, Bradbery, Brown, Ferguson-Patrick,

rationale and outcomes of global education Macqueen, and Reynolds, 2013; Holden &

programs (Bliss, 2007) but as noted by Tye Hicks, 2007; Power, 2008) including career long

(1999, as cited by Hicks, 2003) differences exist professional learning (Buchanan & Harris, 2004;

across countries in relation to forms, connections Mulraney, 2006) and provision of appropriate

and multiple perspectives. In the UK and USA, support and resources (Larsen & Faden, 2008;

global education has been conceptually contested, Mundy & Manion, 2008).

criticised and reviewed by all sides of politics

(Merryfield & Kasai, 2004; Zhao, Lin, & Hoge, Teaching and learning resources provided by

2007; Agabaria, 2011). NGOs for global education have not always been

GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION VOLUME 27, 2014 29

successfully integrated in schools and classrooms Kriewaldt (2003) argues that values are central

such as in Canada (Mundy & Manion, 2008) and to geographical education and that both teachers

the UK (Bourn & Hunt, 2011). Contrary to the and students should deconstruct the ideological

overseas experience, internal research by World framework that positions their values through

Vision (2011) revealed teachers in Australia that the study of people and places and multiple

utilised NGO resources had a positive impact perspectives. The challenge for teachers is

on student knowledge, values and attitudes. whether to stay neutral or play the role of devil’s

Witteborn (2010), however, questions the role advocate to illuminate alternative perspectives

of NGOs and argues they promote values, (Kriewaldt, 2003).

practices and a vision of global citizenship that

is “choreographed by donor countries”. This Purpose of the Study

concern is echoed by Bliss (2005b; 2007) and

The purposes of this research were to find out

Mangram and Watson (2011) and as noted by Tye

(a) after completing a unit of work in global

(1999, as cited by Hicks, 2003) it could be argued education to what degree did it enhance students’

that global education is a rich world initiative knowledge of global issues? (b) to what degree

reflecting an Anglocentric perspective (Berry & did it have a positive impact on attitudes and

Smith, 2009). values of students? (c) to what degree did it

enhance students’ sense of self or personal

Inclusion of Values and Attitudes identity? and (d) to what degree did it promote

active and informed global citizenship?

Students participating in global education are

introduced to a more critical and informed way

of viewing the world. Kriewaldt (2003) argues Measuring Values and Attitudes

from a reconstructionist perspective that students The Global Education Values and Attitudes

develop knowledge and skills through the study Questionnaire (GEVAQ) was developed using

of countries, people and places, and by examining concepts expected to be taught in the Global

different perspectives. The importance of multiple Education framework (Curriculum Corporation,

perspectives is embodied in Australia’s national 2008). Items for the questionnaire were

statement first published in 2002 (Curriculum developed by operationalising concepts relating

Corporation, 2008). to the values and attitudes expected to be

developed in the Global Perspective curriculum.

Submissions by the National Geography Where possible, insight from recent research

Curriculum project team (Berry & Smith, 2009) literature was used to inform the development

to ACARA argued that students should be able of the items. For example, sense of community

to develop values and attitudes through the is one of the desired outcomes of the Global

exploration of ethical dilemmas and critical Education framework. There exists a body of

analysis of differing viewpoints. In exploring literature that has investigated that particular

values in Geography, Kriewaldt (2003) notes that concept. Therefore, key studies (for example,

teachers and curriculum material may draw from McMillan & Chavis, 1986; Chiessi, Cicognani, and

a range of ideologies and teachers should help Sonn (2010) were used to conceptually frame

students to develop informed opinions. sense of community and its various dimensions

and generate items for the questionnaire. Care

In the process of challenging or influencing

and compassion were conceptualised using the

students’ perspectives, Bliss (2005a) notes that

operational definitions concerning the desire to

content and practice are linked. The how and who do something about the suffering of others and

we teach has an impact on students’ outcomes related concepts developed by Martins, Nicholas,

– as informed, responsible global citizens. Shaheen, Jones, and Norris(2013), Gelhaus

Ultimately, Bliss (2005b) sees teaching values as (2012), and others. A comprehensive explanation

an integrated process often requiring “mindset of the development of the GEVAQ will be reported

changes” in moving students beyond thinking and in a forthcoming article.

feeling to acting.

The study reported here is predicated on the

Research on the transformative nature of the notion of values as an individual’s ideas about

broader Australian program Values in Action what is important, worth being or worth doing,

Schools Project reveals students can be and standards about what is desirable and what

supported to develop a deeper understanding of is not (Fraenkel, 1977; Newman, 2004). It is

complex issues (Lovat, Clement, Dally, & Toomey, also predicated on a definition of attitudes as

2010). Similarly, research on Asian studies by dispositions or feelings towards things (Stankov,

Griffin, Woods, and Dulhunty (2004) found a 2011; Wells, 2011) and that these can be positive

correlation between students’ understanding/ or negative or other (Griffin et al., 2004; Tarry &

achievement levels and the teacher’s commitment. Emler, 2007; Wells, 2011). The proposition that

30 GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION VOLUME 27, 2014

values and attitudes can be the same thing, or returned usable surveys. All participants in the

are at least interrelated, has been put forward pre-test were also participants in the post-test.

by several scholars in an attempt to describe

how they are linked (Mellor & Kennedy, 2003; Results

Wells, 2011). For example, someone can have a

feeling that they are part of a community which Data from both administrations of the GEVAQ

were entered on to an SPSS database. Inspection

could be described as the same as an attitude

of the frequencies for all items revealed no

to community (Chiessi et al., 2010), while at

abnormalities. What follows is an account of the

the same time holding sense of community

factor analysis and subsequent comparisons of

as important (valuing it). Values are known to

means.

influence attitudes and behaviour, and can be

extrapolated from the actions of individuals to

some degree (Dilmac, Kulaksizoglu, & Eski, Factor Analyses

2007). Factor analysis was conducted in order to arrive

at a coherent, statistically supported, and reliable

Values and attitudes have been described as set of scales representing the values and attitudes

concepts that cannot necessarily be seen or that are expected to be developed in the global

felt but that exist in the mind (Griffin, Woods, education curriculum. Data from the pre-test were

& Dulhunty, 2006). They appear to operate in entered into an SPSS database and subjected

the realm of feelings and perceptions (Dilmac to factor analyses. A ten factor solution was

et al., 2007). Values in particular have been the identified that reflected those values and attitudes.

subject of a large body of qualitative literature Results are displayed in Table 1. The table

(for example, Hamston, Weston, Wajsenberg, shows the factor names based on the items that

& Brown 2010; Marvul, 2012). However, it is comprised them, the number of the items and a

possible to measure values and attitudes using sample of them.

quantitative methods (Griffin et al., 2006; Mellor

& Kennedy, 2003; Stankov, 2011; Tarry & Emler, Reliabilities of each of the ten scales were

2007). In a study of the attitudes of young considered moderate to very strong and each

adults, for instance, elements of the concept of factor comprised items that were easy to interpret

compassion were effectively and successfully as scales measuring particular values or attitudes.

These scales were comprised of the individual

operationalised into a scale using a questionnaire

GEVAQ items that loaded on each of the factors.

(Martins et al., 2013).

Social justice, for example, comprised seven of

the GEVAQ items relating to elements of social

Method justice. Sample items for each of the factors are

Ethics approval to conduct the study was obtained presented in Table 1. The scores for each cluster

from the relevant ethics committee at Macquarie of items comprising each factor could then be

University prior to commencement of the study. combined to calculate means. Given the success

The GEVAQ was tested using data from the of the factor analyses to identify cogent global

education scales, the next stage of the statistical

first participating school to see if items were

analysis, comparison of means of pre-tests with

understandable and, therefore, dependable, as

the post-tests, to identify differences could be

measures of values and attitudes. Examination

carried out.

of descriptive data for each item revealed no

problems items and the questionnaire was

deemed ready for use in other schools. Comparisons across all schools

Means for each of the above factors were

The GEVAQ was administered to students in

calculated for the pre-test and post-test data.

Years 7 and 8 in the nine independent secondary Subsequently they became means for particular

schools that agreed to participate in the larger values and attitudes for the cohort of students

study. The survey was completed twice, firstly participating in this study. These were compared

prior to the delivery of a global perspectives mathematically and also subjected to a paired-

curriculum, and second, immediately after that samples t-test to identify differences that were

series of learning experiences ceased. The aim of statistically significant (p=0.01, 0.05, 0.10).

this was to determine what, if any, attitudinal or Given the exploratory nature of the research,

value changes occurred in the students as a result a significance level of 0.10 was considered

of a global education curriculum. acceptable (Gay & Airasian, 2000).

Given this design, the first survey can be viewed Factors that had significantly different means were

as a pre-test while the second (identical to the subjected to Cohen’s d analyses to calculate the

first) as a post-test. The response rate was 85%, effect size reflected in the difference. The effect

reflecting 521 participants from a pool of 621 who size statistic, in essence, could be interpreted as

GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION VOLUME 27, 2014 31

Table 1: Results of Factor Analysis

No of Reliability

Factor name Sample item

items (a)

I believe we have a responsibility to help others

Social justice 7 0.80

less fortunate

Personal identity 3 I am happy with the way I am as a person 0.58

Respect for rights of others 5 I think everyone should be treated equally 0.82

There are times when I have asked someone “Are

Empathy for others 3 0.60

you OK” or something similar

Antipathy towards global I believe that Australia shouldn’t waste money on

4 0.53

issues foreign aid

Sense of community –

6 I like learning about other religions and customs 0.86

shared emotional connection

Sense of community –

4 I feel like I belong to a global community 0.68

membership

I think sustainability is important for a healthy

Environmental sustainability 4 0.68

planet

Cooperation and care 5 I assist others when I can 0.81

I get along with students who have different beliefs

Tolerance of difference 4 0.70

to mine

'a' denotes Cronbach's alpha reliability statistic calculated for factors

an estimate of the impact the global education 2002) and hence be able to determine the effect

curriculum had on student values and attitudes. size indicated by the difference.

These comparisons are displayed in Table 2.

The attitude and value that had the largest

Statistically significant differences were difference, and consequently the largest effect

identified for 4 out of the 10 values and attitudes

size, was Personal identity. The effect size

comparisons: Social justice, Personal identity,

Sense of community – membership, and (d=0.94) was considered large statistically

Environmental sustainability. These four were (Hittleman & Simon, 2002). The other three

subjected to a Cohen’s d analysis to determine the values and attitudes subjected to these

magnitude of the difference (Hittleman & Simon, calculations had effect sizes below 0.20 which,

Table 2: Comparison of differences

Factor M1 SD M2 SD Diff t d

Social justice 8.15 1.34 8.32 1.25 +0.17 -2.06** 0.18

Personal identity 5.88 1.36 6.96 1.78 +1.08 -10.82* 0.94

Respect for rights of others 9.03 1.22 9.04 1.10 +0.01 -0.26 - -

Empathy for others 8.90 1.23 8.91 1.18 +0.01 -0.10 - -

Antipathy towards global issues 4.44 1.71 4.40 1.84 -0.04 0.35 - -

Sense of community –

8.30 1.45 8.39 1.50 +0.09 - 0.95 - -

shared emotional connection

Sense of community –

7.41 1.46 7.57 1.53 +0.16 -1.73*** 0.16

membership

Environmental sustainability 8.29 1.22 8.43 1.24 +0.14 -1.78*** 0.15

Cooperation and care 8.72 1.16 8.73 1.17 +0.01 - 0.81 - -

Tolerance of difference 8.63 1.23 8.55 1.32 - 0.08 1.08 - -

* p=0.01, ** p=0.05, *** p=0.10 M1= Mean (pre-test) M2=Mean (post-test)

32 GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION VOLUME 27, 2014

10.00

9.00

8.00

7.00

6.00

5.00

4.00 Mean 1

3.00 Mean 2

2.00

1.00

0.00

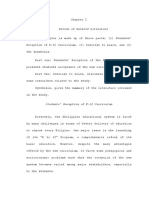

Figure 1: Pre- and post-test means for School A

while significant, could be considered as weak decrease in the same interval. The increases were

(Hittleman & Simon, 2002). as anticipated for all but Tolerance of difference.

A mathematical comparison of the means for The pattern of mean change between pre-test

each revealed changes that were in the expected

and post-test was similar across all nine schools.

directions for all but one of the values and

attitudes. Specifically, means for Social justice, Figures 1 and 2, showing means from two of the

Personal identity, Respect for rights of others, schools (referred to as ‘A’ and ‘B’), illustrates this

Empathy for others, Sense of community – shared similarity. Some minor, non-significant, school-

emotional connection, Sense of community based differences, such as those between Sense

– membership, Environmental sustainability,

of Community – membership in Figures 1 and 2,

Cooperation and care, and Tolerance of difference

were expected to increase in the post-test were observed in comparisons between schools.

compared to the pre-test and the mean of However, the general trends for each factor were

Antipathy towards global issues was expected to quite similar.

10.00

9.00

8.00

7.00

6.00

5.00

4.00 Mean 1

3.00 Mean 2

2.00

1.00

0.00

Figure 2: Pre- and post-test means for School B

GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION VOLUME 27, 2014 33

6.00

5.00

4.00

3.00 M1

M2

2.00

1.00

0.00

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Figure 3: Means of Antipathy towards global issues from the nine schools

On inspection of individual school scores those The means for Tolerance of difference did not

for Antipathy towards global issues were the most increase as expected. Figure 4 shows the means

variable across the nine schools, as shown in for this factor across the nine participating

Figure 3, and this would account for the smaller schools. The differences were very small and this

than expected change result. Nevertheless, in half would explain why the overall change was not

of the schools the mean for this factor increased, significant statistically. Nevertheless, it is worth

suggesting that the students felt more opposed to reporting that the mean did increase, in absolute

global issues such as foreign aid after the global terms from pre-test to post-test, in four schools,

education program and this requires further decreased in four schools and remained the same

investigation. in one school (see result for ‘4’ in Figure 4).

10.00

9.00

8.00

7.00

6.00

5.00 M1

4.00 M2

3.00

2.00

1.00

0.00

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Figure 4: Means of Tolerance of difference from the 9 schools

34 GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION VOLUME 27, 2014

Discussion and Conclusion respect, human dignity and concern for others

The results suggest that the global education may be reflected in the attitudes and behaviour

curriculum had positive effects on students’ of students and teachers (Crick & Jelfs, 2011;

values and attitudes regarding related issues. Dorner, Spillane, & Pustejovsky, 2011; Street,

Increases in value and attitude means could be 2007). The findings could therefore point to an

interpreted as students placing greater importance artefact of school and wider culture.

on particular values or having a more positive

disposition towards them than previously would This study has, of course, limitations that prevent

have been the case. This is a valuable finding us from generalising for all schools. First of all,

pointing to the potential for global education and most importantly, the study represents a

curricula to influence value and attitude change. snapshot of a curriculum program over a short

The strongest impact appeared to be on students’ period of time. A better explanation of the impacts

personal identity or, put another way, the global of global education programs on student values

education curriculum in these schools appeared and attitudes would obviously be achieved via

to have the strongest influence on students’ sense longitudinal studies where students have been

of self. In a recent theoretical paper drawing on exposed to such curricula over a longer period

other scholars, Almond (2010) makes clear the of time. Secondly, the study was conducted in

connection between values taught in schools

independent, faith-based, schools and this could

and the development of student religious and

have influenced the level of means, as a baseline

cultural identities. In an earlier study, Dinter

(2006) described how various aspects of school measure, in the pre-test. A more comprehensive

curriculum can impact on identity formation. study, involving government schools and perhaps

Therefore, the finding reported here could Catholic systemic schools also, is needed to gain

be explained, potentially, as the outcome of a more accurate picture of the impacts of global

a program directed at personal values and a education curricula on students from a variety of

resulting student satisfaction with how they are religious and cultural backgrounds.

developing as individuals.

These limitations notwithstanding, the findings

The results for Tolerance of difference were not

suggest that a global education curriculum has

expected, but could be explained in terms of the

students already having achieved a threshold the potential to influence the values and attitudes,

level of tolerance via their earlier studies of and by extension, the behaviour and inclinations

global issues and exposure to inequity and of students to issues ranging from social justice

injustice via social and other electronic media. and tolerance to their own identities as global

Social media, for example, has been shown to citizens. This kind of personal development is

have influences on attitudes on young adults certainly in line the broad aims of the Melbourne

(Livingston, Cianfrone, Korf-Uzan, & Coniglio, Declaration, which espouses, among other ideals,

2014). It may also reflect the nature of the

the creation of generations of individuals who are

schools included in the sample. The means for

each of the global education values and attitudes “active and informed citizens” (MCEETYA, 2008).

factors were generally moderate to high even at While the direct line between values and attitudes

the pre-test stage, which would partly account and actions can be sometimes obscured by other

for the low difference calculations. There are motivations, there lies in such curricula as Global

possible explanations for this. During interviews Education the potential to influence values in ways

conducted as part of the larger study, some that will more likely lead to changed attitudes

students indicated that they had experienced and, as a consequence, behaviour and choices

global education programs or units of work of a

(Newman, 2004). In relation to dispositions that

similar nature previously. If that is the case, then

are in line with the notion of “active and informed

the higher means might be interpreted as a logical

consequence of formative value and attitude citizens” from the Melbourne Declaration or,

development arising from the previous learning beyond this, succeeding in the constantly

experiences. changing and challenging wider world, the

findings we have reported here are encouraging.

Another explanation for the higher pre-test

means relates to the faith-based nature of the The next phase of the larger study involves an

participating schools. All nine schools have analysis of the qualitative data collected during the

faith-based origins and cater to the predominant

course of the research. Also to be examined is the

religious denominations of their communities.

data related to knowledge acquisition. Subsequent

There is a body of literature that recognises the

highly normative nature of faith-based schools, research papers will detail the findings of these

and how common religious values such as analyses.

GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION VOLUME 27, 2014 35

References Crick, R.D., & Jelfs, H. (2011). Spirituality,

learning and personalisation: exploring the

Agbaria, A. K. (2011). The social studies education

relationship between spiritual development

discourse community on globalization: and learning to learn in a faith-based

exploring the agenda of preparing citizens secondary school. International Journal of

for the golden age. Journal of Studies in Children’s Spirituality, 16(3), 197–217.

International Education, 15(1), 57–74.

Curriculum Corporation. (2008). Global

Almond, B. (2010). Education for tolerance: Perspectives: A framework for global

cultural difference and family values. Journal education in Australian schools. Carlton South:

of Moral Education, 39(2), 131–143. Curriculum Corporation.

Australian Curriculuum, Research and Assessment Development Education Association [DEA].

[ACARA]. (2013). Cross-curriculum priorities. (2010). The impact of global learning on

Retrieved from http://www.acara.edu.au/ public attitudes and behaviours towards

curriculum/cross_curriculum_priorities.html international development and sustainability.

Berry, R., & Smith, R. (2009). Towards a London: Swallow House Group.

National Geography Curriculum for Australia: Development Education Research Centre [DERC].

Background report – June 2009. Melbourne: (2013). Development education and global

Australian Geography Teachers Association learning. Retrieved from http://www.ioe.ac.uk/

Ltd, Brisbane: Royal Geographical Society of DERCUpdateOctober2013.pdf

Queensland Inc, & Canberra: the Institute of

Australian Geographers Inc. Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. New

York: The Free Press.

Bliss, S. (2005a, July). Growing global education

and globalisation in Australia. Paper presented Dilmac, B., Kulaksizoglu, A., & Eski, H. (2007). An

at Pacific Circle Consortium International examination of the Humane Values Education

Conference, University of Western Sydney. Program on a group of science high school

Retrieved from http://www.ptc.nsw.edu.au students. Educational Sciences: Theory &

Practice, 7(3), 1241–1261.

Bliss, S. (2005b). Australian Global Education

Values for a sustainable world. Social Dinter, A. (2006). Adolescence and computers.

Educator, 23(2), 26–38. Dimensions of media‐related identity

formation, self‐formation and religious value

Bliss, S. (2005c). Global perspectives integrated as challenges for religious education. British

in global and geographical education. Journal of Religious Education, 28(3), 235–

Geography Bulletin, 37(4), 22–38. 248.

Bliss, S. (2007). Australian global education: Donnelly, D., Bradbery, D., Brown, J., Ferguson-

beyond rhetoric towards reality. Curriculum Patrick, K., Macqueen, S., & Reynolds, R.

Perspectives, 27(1), 40–52. (2013). Teaching global education: lessons

Boon, H. (2011). Raising the bar: ethics education learned for classroom teachers, Ethos 21(1),

for quality teachers. Australian Journal of 18-22

Teacher Education, 36(7), 76–93. Dorner, L.M., Spillane, J.P., & Pustejovsky,

Bourn, D., & Hunt, F. (2011). Global dimensions J. (2011). Organizing for instruction: A

in secondary schools. London: Development comparative study of public, charter and

Education Research Centre. Catholic schools, Journal of Educational

Change, 12(1), 71–98.

Breithorde, M. L., & Swiniarski, L. (1999).

Constructivism and Reconstructivism: Dyer, J. (2005). Preparing students for a world

Educating teachers for world citizenship. which is global in its outlook and influences:

Australian Journal of Teacher Education, The rhetoric, reality and response. The Social

24(1), 1–17. Educator, 23(1), 45–52.

Buchanan, J., & Harris, B. (2004). The world is Fraenkel, J. R. (1977). Values Clarification is not

your oyster, but where’s the pearl? Getting enough! History and Social Science Teacher,

13(1), 27–32.

the most out of global education. Curriculum

Perspectives, 24(1), 1–11. Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the oppressed.

Ringwood, Vic: Penguin Books Australia.

Chiessi, M., Cicognani, E., & Sonn, C. (2010).

Assessing Sense of Community on Fuijkane, H. (2003). Approaches to global

adolescents: Validating the brief scale of Sense education in the United States, the United

of Community in adolescents (SOC-A). Journal Kingdom and Japan. International Review of

of Community Psychology, 38(3), 276–292. Education, 49(1–2), 133–152.

36 GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION VOLUME 27, 2014

Gallavan, N. P. (2008). Examining teacher Livingston, J. D., Cianfrone, M., Korf-Uzan, K.,

candidates’ views on teaching world & Coniglio, C. (2014). Another time point, a

citizenship. The Social Studies, 99(6), 249– different story: one year effects of a social

254. media intervention on the attitudes of young

Gaudelli, W., & Heilman, E. (2009). people towards mental health issues. Social

Reconceptualizing geography as democratic Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology

global citizenship education. Teachers College 49(6), 985–990.

Record, 11(11), 2647–2677. Lovat, T., Clement, N., Dally, K., & Toomey,

Gay, L. R., & Airasian, P. (2000). Educational R. (2010). Values education as holistic

research: Competencies for analysis and development for all sectors: researching

application (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River: for effective pedagogy. Oxford Review of

Prentice Hall. Education, 36(6), 713–729.

Gelhaus, P. (2012). The desired moral attitude Mangram, J., & Watson, A. (2011). US and them:

of the physician: (II) compassion. Medicine social studies teachers’ talk about Global

Health Care and Philosophy, 15, 397–410. Education. Journal of Social Studies Research,

Goodson, I. F. (1990). Studying curriculum: 35(1), 95–116.

towards a social constructionist perspective. Marshall, H. (2007). Global education in

Journal of Curriculum Studies, 22(4), 299– perspective: fostering a global dimension in an

312. English secondary school. Cambridge Journal

Gore, J. (2004). The role of the school in of Education, 37(3), 355–374.

citizenship education in an era of globalisation.

Martins, D., Nicholas, N. A., Shaheen, M., Jones,

Pacific Asian Education, 16(1), 10–16.

L., & Norris K. (2013). The development and

Griffin, P., Woods, K., & Dulhunty, M. (2004). evaluation of a Compassion Scale. Journal of

Australian students’ knowledge and Health Care for the Poor and Underserved,

understanding of Asia: a national study. 24(3), 1235–1246.

Australian Journal of Education, 48(3), 253–

267. Marvul, J.N. (2012). If you build it, they will come:

A successful truancy intervention program in

Griffin, P., Woods, K., & Dulhunty, M. (2006). a small high school. Urban Education, 47(1),

Australian students’ attitudes to learning about 144–169.

Asia. Journal of Research in International

Education, 5(1), 83–103. McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of

community: A definition and theory. Journal of

Hamston, J., Weston, J., Wajsenberg, J., &

Community Psychology, 14(1), 6–23.

Brown, D. (2010). Giving Voice to the impacts

of values education: The final report of the Mellor, S., & Kennedy, K. J. (2003). Australian

Values in Action Schools Project. Carlton students’ democratic values and attitudes

South: Education Services Australia. towards participation: Indicators from the IEA

Hicks, D. (2003). Thirty years of Global Education: civic education study. International Journal of

A reminder of key principles and precedents, Educational Research, 39(6), 525–537.

Educational Review, 55(3), 265–275. Merryfield, M. M., & Kasai, M. (2004). How

Hittleman, D. R., & Simon, A.J. (2002). are teachers responding to globalization?

Interpreting educational research (3rd ed.). (Research and practice). Social Education,

Upper Saddle River: Merrill Prentice Hall. 68(5), 354–356.

Holden, C., & Hicks, D. (2007). Making global Ministerial Council for Education, Early Childhood

connections: the knowledge, understanding Development and Youth Affairs [MCEECDYA],

and motivation of trainee teachers. Teaching (2008). Melbourne Declaration on Educational

and Teacher education, 23, 13–23. Goals for Young Australians. Melbourne:

Kriewaldt, J. (2003). Values: dimensions in MCEECDYA.

Geography. Geographical Education, 16, Mulraney, R. (2006). Implementing Victorian

41–47. essential learning standards: linking global

Lansford, J. E. (2002). Educating students for life perspectives, pedagogy and principles of

in a global society. Education Reform, 2(4), learning. Ethos, 14(1), 11–45.

1–4. Mundy, K., & Manion, C. (2008). Global

Larsen, M., & Faden, L. (2008). Supporting the education in Canadian elementary schools;

growth of global citizenship educators. Brock an exploratory study. Canadian Journal of

Education Journal, 17(1), 71–86. Education, 31(4), 941–974.

GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION VOLUME 27, 2014 37

Newman, D. M. (2004). Sociology: Exploring British Journal of Developmental Psychology,

the architecture of everyday life (5th ed.). 25(2), 169–183.

Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press.

Tye, K. A. (1999). Global Education: a worldwide

Power, A. (2008). In action: future educators in a movement. Orange, CA: Interdependent Press.

NSW project. Pacific-Asian Education, 20(1),

Wells, J. (2011). International education,

47–54.

values and attitudes: A critical analysis of

Rapoport, A. (2013). Global Citizenship themes the International Baccalaureate (IB) Learner

in the Social Studies classroom: Teaching Profile. Journal of Research in International

devices and teachers’ attitudes. The Education, 10(2), 174–188.

Educational Forum, 77(4), 407–420.

Witteborn, S. (2010). The role of transnational

Stankov, L. (2011). Individual, country and NGOs in promoting global citizenship

societal cluster differences on measures and globalizing communication practices.

of personality, attitudes and social norms. Language and Intercultural Communication,

Learning and Individual Differences, 21(1), 10(4), 358–372.

55–66.

World Vision (2011). Get connected: teacher

Street, R.W. (2007). The impact of ‘The Way evaluation survey results. PowerPoint

Ahead’ on headteachers of Anglican volunteer- presentation at World Vision Marketing.

aided secondary schools. Journal of Beliefs &

Zhao, Y., Lin, L., & Hoge, J.D. (2007) Establishing

Values, 28(2), 137–150.

the need for cross-cultural and global issues

Tarry, H., & Emler, N. (2007) Attitudes, values and research. International education Journal,

moral reasoning as predictors of delinquency. 8(1), 139–150.

38 GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION VOLUME 27, 2014

You might also like

- J 10Document11 pagesJ 10Yvonne WilliamNo ratings yet

- The Futures of Learning 3Document21 pagesThe Futures of Learning 3Sebastian MuñozNo ratings yet

- Setting a Sustainable Trajectory: A Pedagogical Theory for Christian Worldview FormationFrom EverandSetting a Sustainable Trajectory: A Pedagogical Theory for Christian Worldview FormationNo ratings yet

- 2 PBDocument15 pages2 PBDimaz Ananda RizkyNo ratings yet

- Teacher's Perceptions of Students and Global AwarenessDocument16 pagesTeacher's Perceptions of Students and Global AwarenessJohn Cliford AlveroNo ratings yet

- EJ1291252Document10 pagesEJ1291252Theodora VildNo ratings yet

- Kelly2022 Article UniversalDesignForLearning-AFrDocument15 pagesKelly2022 Article UniversalDesignForLearning-AFrdanielNo ratings yet

- Making The Grade: Teacher Training For Inclusive Education: A Systematic ReviewDocument19 pagesMaking The Grade: Teacher Training For Inclusive Education: A Systematic ReviewAllen JordiNo ratings yet

- Uncovering EFL Learners' Perspectives On A Course Integrating Global Issues and Language LearningDocument16 pagesUncovering EFL Learners' Perspectives On A Course Integrating Global Issues and Language Learninghail jackbamNo ratings yet

- 2015 Lauricella Mac Askill OEHolistic EducationDocument26 pages2015 Lauricella Mac Askill OEHolistic EducationNavdeep GillNo ratings yet

- Impacts of Successful Educational Actions On Student OutcamesDocument12 pagesImpacts of Successful Educational Actions On Student OutcamesllanomanexNo ratings yet

- Preparing Teachers To Educate For 21st Century Global CitizenshipDocument23 pagesPreparing Teachers To Educate For 21st Century Global CitizenshipNurl AinaNo ratings yet

- د.انعام وميساء (بحث التنمية المستدامةDocument17 pagesد.انعام وميساء (بحث التنمية المستدامةMaysaa Al TameemiNo ratings yet

- De La Cruz - CURRICULUMDocument34 pagesDe La Cruz - CURRICULUMmizel dotillosNo ratings yet

- Inclusive Pedagogy From Learning To Action. Supporting Each Individual in The Context of EverybodyDocument8 pagesInclusive Pedagogy From Learning To Action. Supporting Each Individual in The Context of Everybodygreys castroNo ratings yet

- HopeDocument23 pagesHopeArkar KyawNo ratings yet

- Student Role in Assessment For LearningDocument19 pagesStudent Role in Assessment For LearningSAMIR ARTURO IBARRA BOLAÑOSNo ratings yet

- Whitehead 2015 Global LearningDocument9 pagesWhitehead 2015 Global LearningMarc JacquinetNo ratings yet

- Book ChapterDocument35 pagesBook ChapterAhmed SalihuNo ratings yet

- Cultivating 21st Century Learners: Grade One Educators' Blueprint in Building A Strong FoundationDocument15 pagesCultivating 21st Century Learners: Grade One Educators' Blueprint in Building A Strong FoundationInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Crawford 2020Document15 pagesCrawford 2020Farnia SariNo ratings yet

- The Death and Life of A School-Based Environmental Education and Communication Program in Brazil Rethinking Educational Leadership and Ecological LeaDocument11 pagesThe Death and Life of A School-Based Environmental Education and Communication Program in Brazil Rethinking Educational Leadership and Ecological LeaAna Carolina SeabraNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER-11 Challenges and Teacher Resilience: The New Normal Classroom Instruction Using Social Media in Philippine ContextDocument15 pagesCHAPTER-11 Challenges and Teacher Resilience: The New Normal Classroom Instruction Using Social Media in Philippine ContextBrittaney BatoNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Need For Graduate Global Education Programs in The United StatesDocument28 pagesAssessing The Need For Graduate Global Education Programs in The United StatesSTAR ScholarsNo ratings yet

- Universal Design For LearningDocument5 pagesUniversal Design For Learningapi-486149613No ratings yet

- Phenomenological Study 2 1Document12 pagesPhenomenological Study 2 1rashmiNo ratings yet

- Academic Writing FinalDocument15 pagesAcademic Writing FinalHodan HaruriNo ratings yet

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument11 pagesReview of Related LiteratureKem Jean ValdezNo ratings yet

- Caring School and EducatorsDocument12 pagesCaring School and Educators22091185No ratings yet

- Situated Learning TheoryDocument13 pagesSituated Learning Theorylunar89No ratings yet

- Global Learning For Sustainable Development in Higher Education: Recent Trends and A CritiqueDocument11 pagesGlobal Learning For Sustainable Development in Higher Education: Recent Trends and A CritiqueShigo HauNo ratings yet

- Constructivism and Pedagogical Practices of English As A Second Language (ESL) TeachersDocument12 pagesConstructivism and Pedagogical Practices of English As A Second Language (ESL) TeachersIOER International Multidisciplinary Research Journal ( IIMRJ)No ratings yet

- Teaching and Teacher EducationDocument15 pagesTeaching and Teacher EducationHenrique Rodrigues CaldeiraNo ratings yet

- Written Assignment 2 EDUC 5810Document5 pagesWritten Assignment 2 EDUC 5810fableydraNo ratings yet

- Students Preferred Qualities and Pedagogies of Araling Panlipunan Teachers Damandaman Benedicto Dolino Libradilla CDDocument140 pagesStudents Preferred Qualities and Pedagogies of Araling Panlipunan Teachers Damandaman Benedicto Dolino Libradilla CDRoy Benedicto Jr.No ratings yet

- The Global Education Terminology Debate: Exploring Some of The IssuesDocument14 pagesThe Global Education Terminology Debate: Exploring Some of The IssuesAdia HeyresNo ratings yet

- Education Comparisons-1Document5 pagesEducation Comparisons-1eefoste4No ratings yet

- DziubanEtal (2018) BlendedLearningTheNewNormalAndEmergingTechnologiesDocument17 pagesDziubanEtal (2018) BlendedLearningTheNewNormalAndEmergingTechnologiesEmily BarretoNo ratings yet

- Blended Learning The New Normal and Emerging Technologies PDFDocument16 pagesBlended Learning The New Normal and Emerging Technologies PDFBagas Annas UtomoNo ratings yet

- MathDocument27 pagesMathDayondon, AprilNo ratings yet

- EDU501Document4 pagesEDU501PatriciaSugpatanNo ratings yet

- Reflection Teaching AdultsDocument6 pagesReflection Teaching AdultsphijuvNo ratings yet

- Grace A1Document23 pagesGrace A1Hà MùNo ratings yet

- Global Teaching Competencies in Primary EducationDocument19 pagesGlobal Teaching Competencies in Primary EducationWulan Aulia AzizahNo ratings yet

- Teacher Attitudes Towards The Inclusion of Students With Support NeedsDocument10 pagesTeacher Attitudes Towards The Inclusion of Students With Support NeedsAndrej HodonjNo ratings yet

- The Development of Education For Learners With DivDocument9 pagesThe Development of Education For Learners With DivABULELA NAMANo ratings yet

- Final Enhanced Thesis Chapter 1 2 3. 3Document29 pagesFinal Enhanced Thesis Chapter 1 2 3. 3Donna Vi YuzonNo ratings yet

- Lenses For Interpreting Global Education in A Contemporary WorldDocument41 pagesLenses For Interpreting Global Education in A Contemporary Worlds h a n i eNo ratings yet

- Manginyog Thesis Manuscript 2024Document63 pagesManginyog Thesis Manuscript 2024Norhamin MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Inclusive International Schooling, Philosophy and Practice Revisited (Agustian 2010)Document44 pagesInclusive International Schooling, Philosophy and Practice Revisited (Agustian 2010)Twinkle StarNo ratings yet

- The Effect of The Round House Strategy On Acquiring Geographical Concepts For Fourth-Grade Literary Pupils and Developing Their Effective CommunicationDocument12 pagesThe Effect of The Round House Strategy On Acquiring Geographical Concepts For Fourth-Grade Literary Pupils and Developing Their Effective CommunicationMonika GuptaNo ratings yet

- A Focus On Self-Directed Learning: The Role That Educators' Expectations Play in The Enhancement of Students' Self-DirectednessDocument11 pagesA Focus On Self-Directed Learning: The Role That Educators' Expectations Play in The Enhancement of Students' Self-DirectednessAnggita Nandya ArdiatiNo ratings yet

- Designing An Integrated Curriculum For Preschool: Greg Tabios Pawilen, Jaeson P. Arre, Eloida F. LindoDocument20 pagesDesigning An Integrated Curriculum For Preschool: Greg Tabios Pawilen, Jaeson P. Arre, Eloida F. Lindohoomesh waranNo ratings yet

- Supporting Educators' Professional Learning For Equity Pedagogy: The Promise of Open Educational PracticesDocument13 pagesSupporting Educators' Professional Learning For Equity Pedagogy: The Promise of Open Educational PracticesAini Fazlinda NICCENo ratings yet

- Asian International Students' College Experience: Relationship Between Quality of Personal Contact and Gains in LearningDocument26 pagesAsian International Students' College Experience: Relationship Between Quality of Personal Contact and Gains in LearningSTAR ScholarsNo ratings yet

- GlobalshowandtellDocument18 pagesGlobalshowandtellapi-348368170No ratings yet

- Challenges To Preparing Teachers To Instruct All Stu - 2023 - Teaching and TeachDocument10 pagesChallenges To Preparing Teachers To Instruct All Stu - 2023 - Teaching and TeachjbagNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1 FiDocument17 pagesCHAPTER 1 FiNicka VillacorteNo ratings yet

- Applications of Andragogy in Multi-Disciplined Teaching and Learning PDFDocument11 pagesApplications of Andragogy in Multi-Disciplined Teaching and Learning PDFtigresse123No ratings yet

- Education for Sustainable Development in the Caribbean: Pedagogy, Processes and PracticesFrom EverandEducation for Sustainable Development in the Caribbean: Pedagogy, Processes and PracticesNo ratings yet

- Bermingham 2016 Investigating The Extent To Which Student-Led Inquiry Is Supported by Fieldwork Booklet DesignDocument7 pagesBermingham 2016 Investigating The Extent To Which Student-Led Inquiry Is Supported by Fieldwork Booklet DesignJavier PNo ratings yet

- Hutchinson 2016 Landscapes Both Invite and Defy de NitionDocument10 pagesHutchinson 2016 Landscapes Both Invite and Defy de NitionJavier PNo ratings yet

- Climate Change and Sustainable Development - The Response From Education The Canadian PerspectiveDocument32 pagesClimate Change and Sustainable Development - The Response From Education The Canadian PerspectiveJavier PNo ratings yet

- ACARA - Geography: Sequence of Content 7-8 Strand: Geographical Knowledge and UnderstandingDocument3 pagesACARA - Geography: Sequence of Content 7-8 Strand: Geographical Knowledge and UnderstandingJavier PNo ratings yet

- Hutchinson 2013 Empowering The Next Generation To Make Their Own WorldDocument5 pagesHutchinson 2013 Empowering The Next Generation To Make Their Own WorldJavier PNo ratings yet

- Hutchinson 2013 World Views, A Story About How The World Works: Their Signi Cance in The Australian Curriculum: GeographyDocument13 pagesHutchinson 2013 World Views, A Story About How The World Works: Their Signi Cance in The Australian Curriculum: GeographyJavier PNo ratings yet

- Assessment in Geography Education - A Systematic ReviewDocument16 pagesAssessment in Geography Education - A Systematic ReviewJavier PNo ratings yet

- 2015 The Ontario Curriculum Grades 11 and 12 Canadian and World Studies - Economics, Geography, HistoryDocument576 pages2015 The Ontario Curriculum Grades 11 and 12 Canadian and World Studies - Economics, Geography, HistoryJavier PNo ratings yet

- Catling 2013 Introducing National Curriculum Geography To Australia's Primary Schools: Lessons From England's ExperienceDocument13 pagesCatling 2013 Introducing National Curriculum Geography To Australia's Primary Schools: Lessons From England's ExperienceJavier PNo ratings yet

- 2018 The Ontario Curriculum Grades 9 and 10 Canadian and World Studies-Geography-History-CivicsDocument198 pages2018 The Ontario Curriculum Grades 9 and 10 Canadian and World Studies-Geography-History-CivicsJavier PNo ratings yet

- Oxfam - Sow The Seed Pupils' WallchartDocument2 pagesOxfam - Sow The Seed Pupils' WallchartJavier PNo ratings yet

- Oxfam - Sow The Seed Wallchart: Start SowingDocument5 pagesOxfam - Sow The Seed Wallchart: Start SowingJavier PNo ratings yet

- Oxfam - Sow The Seed Wallchart: Get Active GuideDocument10 pagesOxfam - Sow The Seed Wallchart: Get Active GuideJavier PNo ratings yet

- Da Costa Junior, J., Diehl, J-C., & Snelders, D. (2019) - A Framework For A Systems Design Approach To Complex Societal ProblemsDocument33 pagesDa Costa Junior, J., Diehl, J-C., & Snelders, D. (2019) - A Framework For A Systems Design Approach To Complex Societal ProblemsJavier PNo ratings yet

- Oxfam - Coffee Chain GameDocument16 pagesOxfam - Coffee Chain GameJavier PNo ratings yet

- Åhlberg 2005 Education For Sustainable Living: Integrating Theory, Practice, Design and DevelopmentDocument30 pagesÅhlberg 2005 Education For Sustainable Living: Integrating Theory, Practice, Design and DevelopmentJavier PNo ratings yet

- Toward The Concrete - Critical Geography and Curriculum Inquiry in The New MaterialismDocument22 pagesToward The Concrete - Critical Geography and Curriculum Inquiry in The New MaterialismJavier PNo ratings yet

- Oxfam - Climate Change, Poverty and WomenDocument6 pagesOxfam - Climate Change, Poverty and WomenJavier PNo ratings yet

- Staeheli 2010 Political Geography: Where's Citizenship?Document8 pagesStaeheli 2010 Political Geography: Where's Citizenship?Javier PNo ratings yet

- Graham 1998 The End of Geography or The Explosion of Place? Conceptualizing Space, Place and Information TechnologyDocument22 pagesGraham 1998 The End of Geography or The Explosion of Place? Conceptualizing Space, Place and Information TechnologyJavier PNo ratings yet

- McKeown 1994 Environmental Education - A Geographical PerspectiveDocument4 pagesMcKeown 1994 Environmental Education - A Geographical PerspectiveJavier PNo ratings yet

- Geography As A Great Intellectual Melting Pot and The Preeminent Interdisciplinary Environmental DisciplineDocument6 pagesGeography As A Great Intellectual Melting Pot and The Preeminent Interdisciplinary Environmental DisciplineJavier PNo ratings yet

- Primary Geography Education in China - Past, Current and FutureDocument26 pagesPrimary Geography Education in China - Past, Current and FutureJavier PNo ratings yet

- Assaraf, O. B.-Z., and Orion, N. 2005. Development of System Thinking Skills in The Context of Earth System EducationDocument44 pagesAssaraf, O. B.-Z., and Orion, N. 2005. Development of System Thinking Skills in The Context of Earth System EducationJavier PNo ratings yet

- Norwegian School Geography and Geographical Education - A New Research Field?Document8 pagesNorwegian School Geography and Geographical Education - A New Research Field?Javier PNo ratings yet

- Morgan 2006 Discerning Citizenship in Geography EducationDocument18 pagesMorgan 2006 Discerning Citizenship in Geography EducationJavier PNo ratings yet

- Cox Elen Steegen 2017 Systems Thinking in Geography - Can High School Students Do It?Document17 pagesCox Elen Steegen 2017 Systems Thinking in Geography - Can High School Students Do It?Javier PNo ratings yet

- Teaching Geography For Social TransformationDocument17 pagesTeaching Geography For Social TransformationJavier PNo ratings yet

- Cox Steegen Elen 2019 Using Causal Diagrams To Foster Systems Thinking in Geography EducationDocument15 pagesCox Steegen Elen 2019 Using Causal Diagrams To Foster Systems Thinking in Geography EducationJavier PNo ratings yet

- Cox 2019 The Use of Causal Diagrams To Foster Systems Thinking in Geography Education - Results of An Intervention StudyDocument15 pagesCox 2019 The Use of Causal Diagrams To Foster Systems Thinking in Geography Education - Results of An Intervention StudyJavier PNo ratings yet

- Goat Milk Marketing Feasibility Study Report - Only For ReferenceDocument40 pagesGoat Milk Marketing Feasibility Study Report - Only For ReferenceSurajSinghal100% (1)

- G006 Sinexcel BESS Micro Grid Solution - MalawiDocument2 pagesG006 Sinexcel BESS Micro Grid Solution - MalawiSyed Furqan RafiqueNo ratings yet

- Reading Passage 1: (lấy cảm hứng) (sánh ngang)Document14 pagesReading Passage 1: (lấy cảm hứng) (sánh ngang)Tuấn Hiệp PhạmNo ratings yet

- The 7 Levels of Wealth ManualDocument215 pagesThe 7 Levels of Wealth Manualawakejoy89% (18)

- Đề 14Document2 pagesĐề 14Gia HannNo ratings yet

- GT 1.1a Drafting Instruments 0Document23 pagesGT 1.1a Drafting Instruments 0Carl Maneclang AbarabarNo ratings yet

- Sem - 2 AEC - 25329 - Speaking & Writing Skills of Communication 2023-24Document2 pagesSem - 2 AEC - 25329 - Speaking & Writing Skills of Communication 2023-24kanakparikh3No ratings yet

- Devoir de Synthèse N°1 - Anglais - 2ème Lettres (2019-2020) Mme Rahmeni JamilaDocument5 pagesDevoir de Synthèse N°1 - Anglais - 2ème Lettres (2019-2020) Mme Rahmeni JamilaSassi LassaadNo ratings yet

- UnivibeDocument1 pageUnivibePablo EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Fabm ReviewerDocument2 pagesFabm ReviewerKennethEdizaNo ratings yet

- Dhaval J. Pathak: Experience Warehouse ExecutiveDocument4 pagesDhaval J. Pathak: Experience Warehouse ExecutiveDhaval PathakNo ratings yet

- (Guide) (How To Port Roms) (Snapdragon) (Window - Android Development and HackingDocument1 page(Guide) (How To Port Roms) (Snapdragon) (Window - Android Development and HackingJus RajNo ratings yet

- CRM # 4044662347 (Zpec # 5)Document1 pageCRM # 4044662347 (Zpec # 5)Mohammad MushtaqNo ratings yet

- American Anthropologist - June 1964 - Pocock - Sociology A Guide To Problems and Literature T B BottomoreDocument2 pagesAmerican Anthropologist - June 1964 - Pocock - Sociology A Guide To Problems and Literature T B Bottomorek jNo ratings yet

- Ok' Time Coffee FinninshDocument26 pagesOk' Time Coffee FinninshMelvin OlarNo ratings yet

- 500-Piso English Series BanknoteDocument24 pages500-Piso English Series BanknoteSehyoonaa KimNo ratings yet

- Himel General CatalogueDocument93 pagesHimel General CatalogueJeffDeCastroNo ratings yet

- Black White Sampling in Quantitative Research PresentationDocument12 pagesBlack White Sampling in Quantitative Research PresentationAnna Marie Estrella PonesNo ratings yet

- Stay Where You Are' For 21 Days: Modi Puts India Under LockdownDocument8 pagesStay Where You Are' For 21 Days: Modi Puts India Under LockdownshivendrakumarNo ratings yet

- Breaking Bad TeaserDocument3 pagesBreaking Bad Teaserjorge escobarNo ratings yet

- RAN1#NR - AH - 03: AgreementsDocument20 pagesRAN1#NR - AH - 03: AgreementssmequixuNo ratings yet

- Power Calculation Drum MotorsDocument2 pagesPower Calculation Drum MotorsFitra VertikalNo ratings yet

- Subject - Verb AgreementDocument12 pagesSubject - Verb AgreementRistaNo ratings yet

- Script For Tablespace Utilization Alert With UTL MAIL Package - Smart Way of TechnologyDocument4 pagesScript For Tablespace Utilization Alert With UTL MAIL Package - Smart Way of TechnologyShivkumar KurnawalNo ratings yet

- Ph0101 Unit 4 Lecture-7: Point Imperfections Line Imperfections Surface Imperfections Volume ImperfectionsDocument41 pagesPh0101 Unit 4 Lecture-7: Point Imperfections Line Imperfections Surface Imperfections Volume Imperfectionskelompok 16No ratings yet

- How To Install Openshift On A Laptop or DesktopDocument7 pagesHow To Install Openshift On A Laptop or DesktopAymenNo ratings yet

- GCED GraphDocument1 pageGCED GraphWan Redzwan KadirNo ratings yet

- FINAL CONCEPT PAPER Edit 8 PDFDocument10 pagesFINAL CONCEPT PAPER Edit 8 PDFJABUNAN, JOHNREX M.No ratings yet

- Pre-Final Examination: Prepared By: Marife G. Ventura Page - 1Document5 pagesPre-Final Examination: Prepared By: Marife G. Ventura Page - 1Princess Dayana Madera AtabayNo ratings yet

- Peter Wicke - Rock Music Culture Aesthetic and SociologyDocument121 pagesPeter Wicke - Rock Music Culture Aesthetic and SociologyFelipeNo ratings yet