Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vincent Duckles - The "Curious" Art of John Wilson

Vincent Duckles - The "Curious" Art of John Wilson

Uploaded by

FelipeCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Wegman MakerComposerImprovisation 1996Document72 pagesWegman MakerComposerImprovisation 1996Ryan Rogers100% (1)

- Dont Op. 37 Galamian PDFDocument35 pagesDont Op. 37 Galamian PDFALEXANDRANo ratings yet

- 18th Century Secular Music - One Voice With (Out) BCDocument105 pages18th Century Secular Music - One Voice With (Out) BCFelipe100% (1)

- 17th Century Secular Music - One Voice With ContinuoDocument203 pages17th Century Secular Music - One Voice With ContinuoFelipeNo ratings yet

- Charles Ives PDFDocument47 pagesCharles Ives PDFNalles.100% (1)

- Hudson BassanoDocument18 pagesHudson Bassanosinderesi100% (1)

- The Music of Henry CowellDocument27 pagesThe Music of Henry CowellPablo AlonsoNo ratings yet

- British Music HistoryDocument23 pagesBritish Music HistoryAna Adiaconitei100% (1)

- Mensural Notations InformationDocument12 pagesMensural Notations InformationTheodor77100% (1)

- Scales & Arpeggios For Cello - Rehearsal EditionDocument127 pagesScales & Arpeggios For Cello - Rehearsal EditionMUSICAL BAIRES100% (1)

- Riam Scales ArpeggiosDocument92 pagesRiam Scales ArpeggiosAengus RyanNo ratings yet

- Art Music 3 Baroque Era Study GuideDocument4 pagesArt Music 3 Baroque Era Study Guidethot777No ratings yet

- The "Curious" Art of John WilsonDocument20 pagesThe "Curious" Art of John WilsonZappo22100% (1)

- Mary Chan - Edward Lowe's Manuscript British Library Add MS 29396Document16 pagesMary Chan - Edward Lowe's Manuscript British Library Add MS 29396FelipeNo ratings yet

- John P. Cutts - Edinburgh University Library Music Ms. Dc. 1. 69Document27 pagesJohn P. Cutts - Edinburgh University Library Music Ms. Dc. 1. 69FelipeNo ratings yet

- Ars Nova John Taverner IDocument2 pagesArs Nova John Taverner Iwalter allmandNo ratings yet

- Charles Ives and His WorldFrom EverandCharles Ives and His WorldJ. BurkholderRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Amphitheatrvm Sapientiae AeternaeDocument550 pagesAmphitheatrvm Sapientiae AeternaeConst VassNo ratings yet

- Charles IvesDocument47 pagesCharles Ivesfgomezescobar100% (1)

- New Shakespeare TheoryDocument18 pagesNew Shakespeare TheoryJOHN HUDSON100% (2)

- British Music Through The AgesDocument7 pagesBritish Music Through The AgesJulienne PapeNo ratings yet

- Final Paper Proposal - Paige SalynDocument9 pagesFinal Paper Proposal - Paige SalynPaige SalynNo ratings yet

- The Woman Who Wrote Shakespeare A Research OverviewDocument15 pagesThe Woman Who Wrote Shakespeare A Research OverviewJOHN HUDSON100% (2)

- Francis Johnson: BiographyDocument2 pagesFrancis Johnson: BiographyReubenPompeiNo ratings yet

- Francis JohnsonDocument2 pagesFrancis JohnsonReubenPompeiNo ratings yet

- THE TEACHING OF SAXOPHONE OVER TIME: From Adolphe Sax to the present dayFrom EverandTHE TEACHING OF SAXOPHONE OVER TIME: From Adolphe Sax to the present dayNo ratings yet

- Vincent Duckles - The Gamble Manuscript As A Source of Continuo Song in EnglandDocument19 pagesVincent Duckles - The Gamble Manuscript As A Source of Continuo Song in EnglandFelipe100% (1)

- Gorboduc or Ferrex and PorrexDocument144 pagesGorboduc or Ferrex and PorrexO993100% (1)

- Sara Itzig SalonDocument39 pagesSara Itzig SalonSandra Myers BrownNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument2 pagesPDFkiss8andrea8iriszNo ratings yet

- Another Time and Place: A Brief Study of the Folk Music RevivalFrom EverandAnother Time and Place: A Brief Study of the Folk Music RevivalNo ratings yet

- Arnold BaxDocument14 pagesArnold BaxIain Cowie100% (2)

- Josquin IntroDocument13 pagesJosquin IntroRuey YenNo ratings yet

- Chapter4 - Part1Document33 pagesChapter4 - Part1Thanh TúNo ratings yet

- Peel - in Summertime On Bredon (Gervase Elwes, Tenor, 1916)Document2 pagesPeel - in Summertime On Bredon (Gervase Elwes, Tenor, 1916)robo707No ratings yet

- Atestat AndreeaDocument25 pagesAtestat AndreeaMihaela Monica MotorcaNo ratings yet

- History of Music EssayDocument4 pagesHistory of Music EssayMaisie JaneNo ratings yet

- Western MusicDocument11 pagesWestern MusicAnika Nawar100% (2)

- Booklet - Classical KirkbyDocument32 pagesBooklet - Classical KirkbyFelipeNo ratings yet

- Gorboduc 1Document149 pagesGorboduc 1Fr Joby PulickakunnelNo ratings yet

- Music in ShakespeareDocument523 pagesMusic in ShakespeareMarc Demers100% (4)

- Annotated Bibliography Primary SourcesDocument11 pagesAnnotated Bibliography Primary Sourcesapi-277596160No ratings yet

- Our True North' - Walton's First Symphony, Sibelianism, and The Nationalization of Modernism in EnglandDocument23 pagesOur True North' - Walton's First Symphony, Sibelianism, and The Nationalization of Modernism in EnglandtrishNo ratings yet

- Famous Composers and Their Works (Vol. 1&2): Biographies and Music of Mozart, Beethoven, Bach, Schumann, Strauss, Verdi, Rossini, Haydn, Franz…From EverandFamous Composers and Their Works (Vol. 1&2): Biographies and Music of Mozart, Beethoven, Bach, Schumann, Strauss, Verdi, Rossini, Haydn, Franz…No ratings yet

- Midieval Period Hildegard Von BingenDocument10 pagesMidieval Period Hildegard Von BingenLhen NonanNo ratings yet

- Sir Watkin Williams Wynn and The Rutgers Handel Collection : by MartinpickerDocument15 pagesSir Watkin Williams Wynn and The Rutgers Handel Collection : by MartinpickerSixtusNo ratings yet

- Not Necessarily English MusicDocument3 pagesNot Necessarily English MusicHeoel GreopNo ratings yet

- Music of New York - The New Grove Dictionary of Music and MusiciansDocument44 pagesMusic of New York - The New Grove Dictionary of Music and MusiciansPedro R. PérezNo ratings yet

- Sesiunea de Comunicări Științifice Limba Engleză: The English RenaissanceDocument12 pagesSesiunea de Comunicări Științifice Limba Engleză: The English RenaissanceAnonymous C8GSwW9wedNo ratings yet

- James Joyce and Avant-Garde MusicDocument11 pagesJames Joyce and Avant-Garde MusicVictoria GianeraNo ratings yet

- Band History EssayDocument7 pagesBand History EssayThomas SwatlandNo ratings yet

- Arnold BaxDocument18 pagesArnold BaxBob LablaNo ratings yet

- The Accordion and The Polka in Polish-American Ethnic MusicDocument3 pagesThe Accordion and The Polka in Polish-American Ethnic MusicVictorGomezNo ratings yet

- From Chaucer to Tennyson: With Twenty-Nine Portraits and Selections from Thirty AuthorsFrom EverandFrom Chaucer to Tennyson: With Twenty-Nine Portraits and Selections from Thirty AuthorsNo ratings yet

- Henry Purcell - A Sketch of A Busy Life Author(s) : Percy A. Scholes Source: The Musical Quarterly, Jul., 1916, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Jul., 1916), Pp. 442-464 Published By: Oxford University PressDocument26 pagesHenry Purcell - A Sketch of A Busy Life Author(s) : Percy A. Scholes Source: The Musical Quarterly, Jul., 1916, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Jul., 1916), Pp. 442-464 Published By: Oxford University PressLeon MilkaNo ratings yet

- Famous Composers and Their Works: Biographies and Music of Mozart, Beethoven, Bach, Schumann, Strauss, Verdi, Rossini, Haydn, Franz…From EverandFamous Composers and Their Works: Biographies and Music of Mozart, Beethoven, Bach, Schumann, Strauss, Verdi, Rossini, Haydn, Franz…Theodore ThomasNo ratings yet

- Beowulf Falls Into Two Parts. It Opens in Denmark, Where King Hrothgar's Splendid HallDocument10 pagesBeowulf Falls Into Two Parts. It Opens in Denmark, Where King Hrothgar's Splendid HallRoksolanaNo ratings yet

- History of Classical Period 1730-1820Document9 pagesHistory of Classical Period 1730-1820Mary Rose QuimanjanNo ratings yet

- York Bowen Viola Concerto FinalDocument7 pagesYork Bowen Viola Concerto FinalThe Land of Lost Content33% (3)

- Russian Liturgical Music and Its Relation To Twentieth-Century IdealsDocument11 pagesRussian Liturgical Music and Its Relation To Twentieth-Century IdealsHelena RadziwiłłNo ratings yet

- Notation Manual - Ross W. DuffinDocument13 pagesNotation Manual - Ross W. DuffinFelipeNo ratings yet

- Booklet - Olympia's LamentDocument13 pagesBooklet - Olympia's LamentFelipeNo ratings yet

- Musical Borrowings in The English BaroqueDocument14 pagesMusical Borrowings in The English BaroqueFelipe100% (1)

- Gordon J Callon - BibliographyDocument31 pagesGordon J Callon - BibliographyFelipeNo ratings yet

- A Monteverdi Source Reappears - The 'Grilanda' of F. M. FucciDocument13 pagesA Monteverdi Source Reappears - The 'Grilanda' of F. M. FucciFelipeNo ratings yet

- Italian Music Manuscripts in The British Library - Section A Part 2 Add. Mss. c.1640-c.1720Document22 pagesItalian Music Manuscripts in The British Library - Section A Part 2 Add. Mss. c.1640-c.1720FelipeNo ratings yet

- Booklet - Concerto Delle DonneDocument15 pagesBooklet - Concerto Delle DonneFelipeNo ratings yet

- Creative Approaches To Ground-Bass Composition in EnglandDocument400 pagesCreative Approaches To Ground-Bass Composition in EnglandFelipeNo ratings yet

- Booklet - Sigismondo D'india - Cappella MediterraneaDocument44 pagesBooklet - Sigismondo D'india - Cappella MediterraneaFelipeNo ratings yet

- English Baroque Mad Songs - ThesisDocument346 pagesEnglish Baroque Mad Songs - ThesisFelipeNo ratings yet

- Booklet - Mortale Che PensiDocument14 pagesBooklet - Mortale Che PensiFelipeNo ratings yet

- Booklet - LamentariumDocument14 pagesBooklet - LamentariumFelipeNo ratings yet

- Booklet - Classical KirkbyDocument32 pagesBooklet - Classical KirkbyFelipeNo ratings yet

- Booklet - Serpent and FireDocument58 pagesBooklet - Serpent and FireFelipeNo ratings yet

- Nina Treadwell - Music of The Gods - Solo Song and Effetti Meravigliosi in The Interludes For La PellegrinaDocument52 pagesNina Treadwell - Music of The Gods - Solo Song and Effetti Meravigliosi in The Interludes For La PellegrinaFelipeNo ratings yet

- Booklet - Cantatas From The Georgian Drawing RoomDocument8 pagesBooklet - Cantatas From The Georgian Drawing RoomFelipeNo ratings yet

- Pamela J. Willetts - Silvanus Stirrop's BookDocument8 pagesPamela J. Willetts - Silvanus Stirrop's BookFelipeNo ratings yet

- Booklet - Elizabeth DavenantDocument45 pagesBooklet - Elizabeth DavenantFelipeNo ratings yet

- Vincent Duckles - The Gamble Manuscript As A Source of Continuo Song in EnglandDocument19 pagesVincent Duckles - The Gamble Manuscript As A Source of Continuo Song in EnglandFelipe100% (1)

- Pamela J. Willetts (1962) A Neglected Source of Monody and Madrigal.Document14 pagesPamela J. Willetts (1962) A Neglected Source of Monody and Madrigal.FelipeNo ratings yet

- Mary Chan - John Hilton's Manuscript British Library Add. MS 11608Document11 pagesMary Chan - John Hilton's Manuscript British Library Add. MS 11608FelipeNo ratings yet

- Mary Joiner - British Museum Add MS. 15117Document60 pagesMary Joiner - British Museum Add MS. 15117FelipeNo ratings yet

- McD. Emslie - Nicholas Laniers Innovations in English SongDocument16 pagesMcD. Emslie - Nicholas Laniers Innovations in English SongFelipeNo ratings yet

- Mary Chan - Christ Church Manuscript Mus 439Document40 pagesMary Chan - Christ Church Manuscript Mus 439FelipeNo ratings yet

- Mary Chan - Drolls, Drolleries and Mid-Seventeenth-Century Dramatic Music in EnglandDocument60 pagesMary Chan - Drolls, Drolleries and Mid-Seventeenth-Century Dramatic Music in EnglandFelipeNo ratings yet

- Mary Chan - Edward Lowe's Manuscript British Library Add MS 29396Document16 pagesMary Chan - Edward Lowe's Manuscript British Library Add MS 29396FelipeNo ratings yet

- John P. Cutts - Tenbury 1018Document11 pagesJohn P. Cutts - Tenbury 1018FelipeNo ratings yet

- Happy Birthday in Chopin S Style: A Tempo Di Valse (Document8 pagesHappy Birthday in Chopin S Style: A Tempo Di Valse (Minh Nguyen ThanhNo ratings yet

- Messiah - For Unto Us A Child Is Born PDFDocument10 pagesMessiah - For Unto Us A Child Is Born PDFMicaeli Rourke du PlessisNo ratings yet

- (Clarinet - Institute) Bach, J.S. - Keyboard Arr. of Marcello Violin Conc. BWV 981 Cl4Document35 pages(Clarinet - Institute) Bach, J.S. - Keyboard Arr. of Marcello Violin Conc. BWV 981 Cl4André DehéeNo ratings yet

- Im Always by Your Side John Park Bass Clef MelodyDocument2 pagesIm Always by Your Side John Park Bass Clef MelodyclaudioNo ratings yet

- Twelve Italian Songs GuitarDocument26 pagesTwelve Italian Songs GuitarMatias Tomasetto100% (1)

- Trombone PresentationDocument15 pagesTrombone Presentationapi-316009379No ratings yet

- Brassafolia SC PtsDocument44 pagesBrassafolia SC PtscatiasilvacostaNo ratings yet

- TRIAD PAIRS 1 - Key of Eb - Theory - Armando Alonso - FREEDocument13 pagesTRIAD PAIRS 1 - Key of Eb - Theory - Armando Alonso - FREENestor CrespoNo ratings yet

- Analise Webern1 PDFDocument11 pagesAnalise Webern1 PDFAndréDamiãoNo ratings yet

- Jazz Improv Made Easy Fast Track GuideDocument16 pagesJazz Improv Made Easy Fast Track GuideFrankie DeschachtNo ratings yet

- The Art of Visualising Music: Graphic ScoresDocument15 pagesThe Art of Visualising Music: Graphic ScoresFrancescoM100% (1)

- Creative Chord ProgressionsDocument6 pagesCreative Chord ProgressionsCarlos Cruz100% (1)

- I. Allegro - Sonata C.E.P.Bach - Part. PianoDocument22 pagesI. Allegro - Sonata C.E.P.Bach - Part. PianoabcdefghijklmnñNo ratings yet

- Chatmusician: Understanding and Generating Music Intrinsically With LLMDocument19 pagesChatmusician: Understanding and Generating Music Intrinsically With LLMZhongchun ZhouNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Bartóks Music For Strings Percussion and CelestaDocument4 pagesA Guide To Bartóks Music For Strings Percussion and CelestaAna Sincich100% (1)

- 16DMUSP001Document122 pages16DMUSP001Rafael CoelhoNo ratings yet

- Divers ComposersDocument3 pagesDivers Composersapi-440300122No ratings yet

- GUITAR-4 Fantasies by Gerard ReboursDocument7 pagesGUITAR-4 Fantasies by Gerard ReboursClavicytheriumNo ratings yet

- Caribbean CapersDocument21 pagesCaribbean CapersGustavo Marcano LopezNo ratings yet

- Cadieu 1969 ADocument3 pagesCadieu 1969 AalexhwangNo ratings yet

- (Clarinet - Institute) Robertson, Ernest - 10 Duos For Flute and Clarinet, Op.56 PDFDocument38 pages(Clarinet - Institute) Robertson, Ernest - 10 Duos For Flute and Clarinet, Op.56 PDFCamron AndrewsNo ratings yet

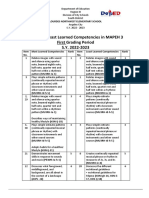

- MAPEH3 - 1st QTR - MOST-LEAST-LEARNED-SKILLSDocument2 pagesMAPEH3 - 1st QTR - MOST-LEAST-LEARNED-SKILLSDesserie100% (1)

- Madrigal 1Document1 pageMadrigal 1dunhallin6633No ratings yet

- Beethoven InformationDocument5 pagesBeethoven InformationMatt GoochNo ratings yet

- Music History Diagnostic ExamDocument4 pagesMusic History Diagnostic ExamLê Đoài Huy100% (1)

- Choral Music SamplerDocument25 pagesChoral Music SamplerJuan García LlatasNo ratings yet

Vincent Duckles - The "Curious" Art of John Wilson

Vincent Duckles - The "Curious" Art of John Wilson

Uploaded by

FelipeOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vincent Duckles - The "Curious" Art of John Wilson

Vincent Duckles - The "Curious" Art of John Wilson

Uploaded by

FelipeCopyright:

Available Formats

The "Curious" Art of John Wilson (1595-1674): An Introduction to His Songs and Lute Music

Author(s): Vincent Duckles

Source: Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 7, No. 2 (Summer, 1954), pp. 93-

112

Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the American Musicological Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/829764 .

Accessed: 15/06/2014 08:51

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of California Press and American Musicological Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to Journal of the American Musicological Society.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The "Curious"Art of JohnWilson (1595-1674):

An Introduction to His Songs and Lute Music

BY VINCENT DUCKLES

JOHNWILSON'SSMALLPLACEin mu- twenty he collaborated with Lanier

sical and literary history has been and Coperario to provide music for

due in large part to reflected glory the Masque of Flowers (1614). In

from the light of Shakespeare. A few 1632 he appeared as the composer of

slight and charming settings by Wil- the songs for Richard Brome's play,

son of such lyrics as "Take, O take The Northern Lass. In 1622 a John

those lips away," "Where the bee Wilson, presumably the composer

sucks," and "Lawn as white as driven under consideration, was appointed

snow," are mentioned in all studies to the company of the London waits

of Shakespeare music. Rimbault held "upon trial had of that his sufficiency

an attractive theory, which has never and judgement."2 Although men-

been fully substantiated, that John tioned as a musician in the court

Wilson could be identified with Jack records as early as I635, he did not

Wilson, a singing boy in Shake- achieve the eminence of a "Gentle-

speare's company; whether true or man of the Royal Chapel" until after

not the theory has given further the death of his colleague, Henry

weight to the association with the Lawes, whose place he assumed in

great dramatist.' But Wilson's status 1662. Like Lawes, Wilson was a

as a composer in his own right has lutanist and a counter-tenor, and as

never been appraised. The long ca- such took part in numerous court

reer of this musician, which coin- masques and entertainments in the

cided with one of the most eventful years preceding the Civil War. He

periods in British history and in- was highly regarded at court as a

volved responsible posts in city, chamber singer, a man with a good

court, and university music, deserves voice and a skillful hand on the lute,

more attention that can be claimed who delighted court society with his

by a mere eddy in Shakespeare schol- performance of the light love lyrics

arship. His songs in the printed col- of the day. It was reported by An-

lections from 1652 onwards are sec- thony Wood that Charles I used to

ond only to those of Henry Lawes in stand with his hand on Wilson's

number, and the manuscript sources shoulder while the musician sang, not

sustain the impression of his popu- an uncommon mark of royal ap-

larity. proval since Nicholas Lanier and the

Wilson's musical activity, except Lawes brothers enjoyed the same

during the interval of the Common- favor. During the Civil War, Wilson

wealth, was closely connected with retreated to Oxford with the court

the life of the court either in Lon- and for a period of about ten years

don or in Oxford. Before he was lived in the residence of Sir William

1 Edward F. Rimbault, Who was Jack Wil- 2 Walter L. Woodfill, Musicians in English

son, the Singer of Shakespeare's Stage? (Lon- Society from Elizabeth to Charles I (Prince-

don, x86I). ton, 1953), p. 42.

93

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

94 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY

Walter, a wealthy music-lover near more in the nature of a sinecure, a

the city. An Oxford Doctor of Music reward for his royalist sympathies,

degree was conferred upon him in than for any real demand for his

I644, and in i656 he was made Pro- services.

fessor of Music at that University, A vivid picture of Wilson as a

relinquishing that post at the Restora- musician and as a personalitystems

tion to return to the King's Musick from his period at Oxford, thanksto

in London. the observationsof that alert musical

John Playford, the publisher, was amateur, Anthony Wood. Wood

quick to recognize the popularity of makes it clear that Wilson was the

Wilson's songs and printed more than leading spirit of the little group of

50 of them in his series of collections Oxford musicians who met at the

beginning with Select Musical Ayres home of Will Ellis to make music

and Dialogues in i652. Wilson him- during the troubleddays of the war.

self appeared as editor of a collection Here we see Wilson as a vigorous

printed in Oxford in I66o under the and forceful character,who "some-

title, Cheerful Ayres and Ballads, and times played the lute, but mostly

described as the first piece of music presided the consort." In Wood's

printing to issue from that city. It is phrase,"he was a great pretenderto

devoted almost entirely to songs buffonery,and the greatestand most

composed early in Wilson's career, curious judge of music that ever

with several additional pieces by was."• The I8th century, however,

Robert Johnson and Nicholas Lanier. madeshort work of Wilson'sreputa-

Three years earlier, in 1657, Wilson tion. It was Dr. Burney's view that

had provided musical settings for the only thing which could account

Thomas Stanley's version of the for the prestigeof a musicianof Wil-

eikon basilike, issued as Psalterium son's caliber was the extraordinarily

Carolinum, the Devotions of his low level of musicallife in Oxford in

Sacred Majestie in his Solitudes and the i7th century. "Little had been

Sufferings. The composer was 62 heard,and but little was expected."4

when this publication appeared, and More recent historianshave soughtto

he resolved, according to a statement justify his fame in reasonsother than

in his preface, that this tribute to the his musicalgifts. Nagel suggeststhat

murdered Charles would be "the last it was his strong personalityand his

of his labours." Although he lived for talents as an administratorwhich

another sixteen years at least, there is brought him into eminence.5It is

little evidence that he departed from certainthat he had a great deal to do

this resolution. There were musical with establishingthe music school at

as well as personal reasons why he Oxford; there are receiptsin his own

should have ceased activity as a com- hand for the purchaseof instruments

poser. Wilson's serious song style had and the construction of improve-

become old fashioned by the time he ments in the buildings.

returned to the court in 1662. A new One can see the extent to which

taste in verse of a more popular, semi- 3 Anthony ' Wood, "Lives of English Mu-

sicians." Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Wood

political kind was growing; the court D. I9 (4).

demanded ballads and French dance 4 Charles Burney, A General History of

tunes-the kind of thing Charles II Music, ed. Frank Mercer (London, 1935),

could tap his foot to. No doubt Wil- Vol. II, p. 314.

5 Wilibald Nagel, Geschichte der Musik in

son's Restoration appointment was England (Strassburg, 1897), Vol. II, p. 212.

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE "CURIOUS"7 ART

OF JOHN WILSON 95

Wilson's fame has lapsed since his The phrase, "His curious hand his

own time by reading some of the fancy did bedeck," strikes a familiar

17th-century tributes to his art. A note in contemporary opinion. More

manuscript in the Bodleian Library than one writer of the time uses the

contains the versified impressions of word, "curious," in alluding to Wil-

Sir Robert Southwell written while son's work. It appears in some verses

he was an undergraduate at Queen's by Robert Herrick addressed to

College." The subject which moved Henry Lawes: 7

this amateur poet to the heights of

Then if thy voice comminglewith the

artificial eloquence was "Dr. Wilson

and his lute at Ellis his meeting, Dec. String

I hear in thee the rare Laniere to sing

31, [i6]55." The phrases, extrava- Or curiousWilson....

gant as they are, still convey the

writer's vivid experience: It must be stated that the ordinary

objective sense in which we use the

Silence! I saw from its dark coffinrise term "curious" today, as suggesting

This prison'd Lute: and then I lost my

something novel, strange, or queer,

eyes. was not the common I7th-century

All senses did unite to bear a share,

And throng'd into the portals of mine ear. usage. At that time it referred to a

The Profound Orpheus, seated with con- quality of workmanship that was

skillful or ingenious, or to a product

tent,

that was choice, excellent, or fine. It

Deign'dto embracethe silent instrument,

But by the virtue of his hand'sex'cute, also had a subjective meaning in

Life trickledfrom his fingerson the lute, which it signified an act of judgment

Which, being inspired,first each grateful that was precise, clear, and well-de-

string fined-the usage intended by Wood

His power,his bounty,andhis praisessing. in praising Wilson as a "most curious

Rhetorickof Raptures(at first dash) was

there judge of music." Still another conno-

tation of the term suggested the ab-

Drown'd in the wondering whirlpool of

mine ear; struse, intricate, or subtle qualities

Then he a new-born voluntary hurls which Henry Lawes must have had

in mind when he wrote in his com-

Through the conduit of its inward curls.

His curious hand his fancy did bedeck, mendatory verses to Wilson's Psalte-

And Musick followed every finger beck. rium Carolinum (1657):

He ruled that Sphere, and his command

From long acquaintance and experience, I

was such

Could tell the World thy known integrity;

That, by the influence of a flying touch, Unto thy Friend, thy true and honest heart,

Each gut ensnared a soul: never evok'd

Ev'n mind, good nature, all, but thy great

string Art;

But to embrace his fingers with a. ring.

Which I but dully understand...

I stood amazed such power in gut to see,

That from the Dung-hill took its pedegree. And further:

Fountain of Pleasure, all whose parts and

For this I know, and must say't to thy

themes,

Whose slender strings are thy enchanting praise,

That thou hast gone, in Musick, unknown

streams;

Thy lustrous melody all Bliss can sum, ways,

And waft a soul to its Elisium. Hast cut a path where there was none

before,

Like Magellantraced an unknown shore...

e Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Eng. poet.

f. 6. 7 Hesperides (1648).

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

96 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY

Henry Lawes was no mere layman groupedtogetherin the first 22 pages

in musical matters. The fact that the of the volume.

most admired composer of his age It is evident that Wilson's manu-

should praise his colleague for mov- script was not, like some of the other

ing into music's "unknown ways" sources of the period, a composer's

should prompt a restudy of the songs workbook full of miscellaneousjot-

dismissed so emphatically by Burney. tings for his daily use as a performer.

But it is difficult for modern ears It has the characterof a deliberately

to appreciate what was exceptional contrived opera omnia, a collection

about Wilson's style, at least on the which was compiled as an authorita-

ground of his published songs. His tive source by the composerhimself.

settings in the Playford publications, The calligraphy is extremely neat

and in his own Cheerful Ayres, are and legible, and the manuscript is

certainly no better than the kind of unmarkedby practical use. In one

thing his fellow court musicians were respect, however, it seems to be in-

producing in great quantity during complete.Most of the songs aregiven

the first half of the i7th century. in the treble and unfiguredbass ar-

One is tempted to conclude that rangement common to song collec-

much of the attraction Wilson held tions of the time, but in Wilson's

for his contemporaries was due to manuscriptspace has been left for

the art of a performer with a per- the insertion of the lute tablature.

sonal, somewhat idiosyncratic style, Not until the latterpart of the manu-

the aspect of his work which is, un- script is the tablature added for a

fortunately, beyond recovery today. group of eighteen Englishsongs and

A skillful musician with a lute in his nineteen settings of Latin verse,

hands and his own voice as the solo chiefly from Horace. The lute bass

instrument could bring quality and differs slightly from the continuo

conviction to the most unpromising bass, which was presumablyplayed

score; and it must be admitted that on a viol. These English lute songs

many of Wilson's scores are sadly in and Latin settings were never pub-

need of that added ingredient. lished, nor are they found in any

There is, however, one source other contemporary manuscript

which provides a clue to Wilson's source. One can only conjecture as

reputation as a composer of rare and to why a full harmonizationwas sup-

curious songs, as well as a lutanist of plied them and not the other songs

deep skill. This is the autograph in the collection. Perhapsthe com-

manuscript which he presented to the poser felt that these works demanded

Bodleian Library in about 1656 when an elaborateand studied accompani-

he accepted the Oxford professor- ment beyond the range of the ordi-

ship.8 He stipulated at that time that nary formulas for a lute continuo.

the manuscript was not to be con- Whatever his reasons, we can be

sulted by anyone until after his death, grateful for them, because there is

an attitude which suggests the de- all too little evidence of the kind of

liberate breaking off of at least one harmonicthinkingthat existedin the

phase of his life as a composer. The minds of the song composersof Wil-

manuscript contains some 220 songs, son's generation. Mid-I7th-century

including a number of dialogues, and songs with lute tablature are com-

30 solo lute pieces, the latter all parativelyrareoutside of a few ama-

8 Oxford, Bodleian Library, Mus. B. I. teurs' collections in which the lute

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE c'CURIOUS ' ART OF JOHN WILSON 97

writing is of the most primitive kind. The text is a trivial Cavalier lyric

The song, "Beauty which all men and one wonders why it should have

admire," is a convenient starting been selected for treatment in such

point for the study of Wilson's bi- an unconventional fashion. If there

zarre harmonic imagination. It is not is some descriptive intent behind the

among those provided with tablature. strange harmonic progressions it is

At least two other manuscript ver- too subtle for the modern listener to

sions are preserved, indicating that it grasp. The harmonic structure de-

had some currency among the com- rives from a chromatically rising bass

poser's fellow musicians., It is ob- which arrives at full cadences suc-

Ex. IW

Beau-fy

which all men

od-mire coar-rec on chos - fns my de- sire.

Pride Scorn the serveva are that ush-erus un-+ofte fir. lndto so

a•nd

,I I , I

cer-fain loss we runtha+ + 9oughwe thrive we are un - done.

Servile

`nures love +hemmost, and but of bondage can - not boost;

ove them s)ill and live in scorn, for such vile use us they're born.

PCJ Hto,.

--69"1I ! , .

viously a tour de force, an experi- cessively in G, Ab, A, Bb, B, and C

mental work of the kind composers in rapid succession. There is no mod-

in all ages have devised for their own ulation in the ordinary sense; instead,

amusement and for the amazement the ear is wrenched from one tonal

of their friends (see Ex. i). level to the next with no opportunity

9 The song is found in New York Public

to establish itself in the home key

Library, Ms. Drexel 4041, and in Oxford,

Library of Christ Church College, Ms. i7. until the final cadence. At the same

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

98 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY

time, the melody is completely dia- favorite cadence chord is the domi-

tonic, and the cadence formulasare nant seventh,frequently unprepared.

all quite conventional.This pre-tonal His dissonance seems crude when

harmonic style, in which the triads transferredto the modern keyboard

are ambiguousas to mode, and every instrumentbut quite appropriateto

tone can take on the characteristics the transparenttexture of the lute

of a leading tone, is not peculiar to writing. It is a dissonancewhich is

Wilson. It exemplifiesthe Early Ba- harmonicallyconceived and does not

roque range of harmonic freedom develop from the continuity of the

but carriedto a degree rarely found inner voices. Sometimes it is moti-

in English music. The outcome in vated by the text, but there is no

this instanceis hardlya work of mu- slavishpictorialism.It is evident that

sical distinctionbut such was proba- the quality of the lyric as a whole in-

bly not intended.Here is John Wil- fluences the composer's choice of

son, "the pretender to buffonery," harmoniesand selection of key. He

playing a lutanist'strick on his lis- uses much greater freedom in the

teners. It reveals a musicianwith a choice of key than is found in the

droll and rationalisticturn of mind work of the earlierlutanistsong com-

who delightedin framinghis musical posers;F minor is a favorite tonality

ideasin patternssometimescarriedto for the setting of melancholyor ex-

the point of absurdity.The signifi- pressive texts. A few excerpts, se-

cance of this approachto composi- lected from a great many possibili-

tion will becomemoreapparentwhen ties, can serve to illustrateWilson's

we consider his solo lute music. skill as a harmoniccolorist.

Ex. 2

,•', e, • _ .,. j, I, ' •

I.

I

the firs+ woV bu+ hec - - vyfo worn

:e

Ojc;

j~

I'-" ~ T1

Wilson is considerablymore artful Note the expressivedissonancein

in his use of harmony in the lute Ex. 2 on the word "heavy,"brought

songs of the Bodleian manuscript. about by the unprepared 2nd be-

The tablaturesreveal an astonishing tween the f# in the lute part and the

amount of harmonicinterestand va- gg in the voice, furtherintensifiedby

riety concealed between the rather the delayed resolutionof the ascend-

pedantic declamatory melodies and ing bass moving from d# to, e.

the continuo bass lines, qualities The suspension on the word

which could scarcely be deduced "strikes,"at the end of the second

from the lines themselves.The lute measure of Ex. 3, is correctly pre-

part is spiced with accented passing pared accordingto the rules of i6th-

tones and non-chord tones. He is century counterpoint,but the abrupt

fond of the sonorities of parallel introduction of a new voice in the

tenths and chainsof sixth chords;his lute part,the f, gives a sharpand pun-

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

"cCURIOUS" ART OF JOHN WILSON 99

-

Ex.

1lift IAA

190. .

-d - U

IL-•

gent effect to the emphatic word of max he often introduces a sharp dis-

the text. sonant progression in the closing

The excerpt from one of the Latin measures of his songs. Here with ob-

settings in Ex. 4 illustrates a device vious pictorial intent the lute part

which the composer was particularly descends to the earth while the voice

fond of using. Over a single harmony rises to the stars, creating a spread of

in the lute part, the voice moves three octaves between the solo and

freely through prominently placed the lute bass. The emergence of the

non-chord tones, in this case the note F major triad out of the harsh dis-

d on the third beat of the first and sonance preceding it is a striking

second measures. Although the lute effect.

Ex. 4

e

. te, pa-+er Sil -

vo-• ne, u-+or fin - i-urn

A)

sound would not sustain itself as sug- It would be unjust to a song com-

gested in the score, the clash of the poser to demonstrate his style by

minor sixth against the f# major triad means of fragments; at least one com-

is pronounced. plete setting is required. A song

The next example (Ex. 5) illus- which reveals many of the elements

trates one of Wilson's most dissonant of Wilson's harmonic and melodic

cadences. With a fine feeling for cli- technique is his setting of Thomas

Ex. 5

would think.. h RP - res-+ri-ol

i+ a ter- s i gal - ax - y.

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1 00 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY

Stanley's "Draw near, you lovers, vein seems restrainedin comparison

that complain," a metaphysical lyric with this song. The emotionseemsall

which would make severe demands the more intense because it is af-

upon any composer. Stanley, a lesser fected. The conventionalizedexcess

member of the school of John Donne, of Stanley'slyric is perfectly matched

wrote verse which was conspicuously in Wilson's music.

lacking in musical quality, full of ob- The song exhibits one feature of

scure imagery and strained conceits. style distinguishingWilson from his

Nevertheless the musicians of the time English contemporaries,namely his

vied for the honor of collaborating feeling for long, continuousmelodic

with him.'0 The particular lyric un- phrases.The declamatoryair in the

der consideration (Ex. 6) is a typical handsof Henry Lawes, for example,

product of his pen, an epitome of tends to break down into a succes-

I7th-century melancholy, with the sion of short-windedfragmentssep-

virtue of sustaining a single emotional arated by strong cadences. Wilson,

quality throughout. on the other hand,never fails to ob-

Wilson gives the text a modified serve the continuity of line, which in

strophic setting. The first two stanzas turn dependsupon the broadunitsof

are set to the same music, with altered

poetic thought. In Stanley's lyric

declamation in the second; the third there is only one full stop midway in

stanza achieves an effective contrast the first stanzaafter the word "tear."

by meansof a change in tonality Here the music comes to a momen-

from the dominant of A minor to G

tary rest, but elsewhere its flow is

major. The slow descending line of maintained by means of deceptive

the first phrase, with its sudden quick- cadences.There is a certainflexibility

ening and return to the high register in the vocal line which grows out of

on the words, "and to my ashes lend the sensitive declamation;but if one

a tear" (mm. 5-6), gives a sensitive

placesthis song besidean airof Dow-

expression to the meaning of the text. landor Daniel,its rhythmicregularity

The unexpected dissonance of the

immediatelybecomes apparent.The

note c in the lute part in m. 13, first lute part performsthe function of a

beat, and again in m. 30o,adds a touch true continuo;the harmonyis firmly

of poignancy, as do the slow synco-

supportedby the bass, and the inner

pations in the second stanza at the voices do not sustainmelodic lines of

words, "softly, O softly mourn" any interest as such. These observa-

(mm. 29-3i). The coda-like section tions are importantin placing Wil-

of eight measures which concludes son's work in its proper historical

the song reveals an intensity of feel-

perspective. He does not belong

ing found in certain Italian monodies among the lutanist song writers of

of the period. The voice enters on an the first decades of the century; he

f over an A minor triad and then falls is a true representativeof the English

to the g# a diminished seventh below,

Early Baroque,althoughsome of the

and the final measures are heightened moredistinctivefeaturesof the Italian

with expressive dissonance. Dowland

in his most doleful and

song style, which have been taken as

melancholy definitive marksof the new era, are

10

lacking in his work.

Henry Lawes set a number of Stanley

lyrics, and the entire contents of John Gam- Baroquesong in all the European

ble's First Book of Ayres and Dialogues (1656) countrieshadits beginningsin literary

consists of settings of Stanley's verse.

theory, and it progressed, at rates of

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE "CURIOUS"1 ART OF JOHN WILSON 101

Ex. 6

5 f

I4I O lif

I"

PWI I "ilkI I" I"

Drwner +h+ o -pI inoff -n, o

addi~~

L 20'*Pmdb yes

yu- .r you sod -•

ledotm-Metteroble. "t "l'ho'lnpdsotethrlenty

A

sones, whose cold em-roces__ do victim. hid th? poi to Bou yon Love'

TLL

I101%

1 W

r=I F, 15 - = = = I -'. rJ '

j

J

l~l 1I,nor

l, ' j !+law

I71 sing to

"J _ died.

l-to• * No

I, ~ no Epicedium

I , bring, ,

peoaceful

recjuiem AL

rF*verse,__

chodrmthe terrors of my hearsle; no pro-phone numbers mustflow neolrthe soced

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

102 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY

Ex. 6-Continued

silence hat dwells here. Vasa griefsare dumb; soff-ly Oh soft -

45

MJIV% I lie

Id

A•- - I !•

FEW.. . i

J J I ll l

_ _ ,, l

. ,,L

I I

on mydismol grve such s you hove fors ken Cypress, and

k off'rings

... ,,

.--q ••

. ..

, '

. ?I.140.

or

q • Ir , j

-I FA

7 l , FI

on m imlgaesc f rng syuhv os pes n

eo mr. u rdufset,

my toke no ot weep my

e growth nd syre Here

sad yew, for kinder

ou frees

Weepyur can tirth or duostk fromthis unhappy

50

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE "CURIOUS" ART OF JOHN WILSON 103

Ex. 6-Concluded

lies po Love and an - qual soc-

Fa•e ri-lice.

IL.II&l_1

speed governed by the varying na- and sense."1 In the pagesof Wilson's

tional traditions, in the direction of autographmanuscriptmidway in the

pure musical form. In Wilson's songs I7th century, one can trace the dis-

few of the decisive steps in that prog- integrationof the last elementsof the

ress were taken. Apart from his de- Renaissancelute ayre and observethe

veloped sense of harmonic color and transformationof the lute from a

an incipient feeling for form based on polyphonicto a continuoinstrument.

tonality, he used none of the devices Looking toward the other end of the

which led the Italians along the path century, one can see in his harmonic

to the opera and the chamber cantata. skill, his treatmentof dissonance,and

There is no antithesis between aria his love of sonority the elements in

and recitative, no recitative as such, Englishmusicwhich persistedin spite

no forms developed by means of of the increasingpressureof foreign

ostinato, sequence, or the use of ritor- influences.But it would be smallsatis-

nello. The unrelieved effort to trans- faction to any composer to be re-

late word rhythms into melody set garded merely as a transitionfigure.

a limit upon the degree to which his Does Wilson deserve any more than

art could develop. He was caught that? In my opinion he does, and the

between two incompatible trends, a evidenceis found not only in his lute

song tradition which demanded the songs in the Bodleianmanuscriptbut

artistic fusion of words and music in his solo lute music as well, pre-

and a new spirit in lyric verse which servedin the samesourceandthus far

was moving in a direction music could ignored by studentsof 17th-century

not follow. Since the poets could not, English music.

or would not, modify their require- The full story of the lute in Eng-

ments, the musicians had to adjust as land has never been told; nor can it

best they could. But it was not until be told until scholarshave completed

composers like Purcell and Blow had the investigationof the rich body of

the audacity to rip a text to pieces source material to be found in the

and reassemble it in conformity with BritishMuseum,the CambridgeUni-

their musical ideas that the transition versity Library, and other British

to the Middle Baroque style became and continentalcollections.12 Richard

complete in England. John Wilson

was one of the last of the 11 The phrase occurs in Lawes's preface to

English his Second Book of Ayres and Dialogues

to writetruedeclam- (1655).

songcomposers 12 A comprehensive study of solo lute music

atory airs designed, as Henry Lawes in England has recently been undertaken by

put it, "to shape notes to the words a young Cambridge University scholar, David

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

104 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY

Newton,in 1938,wasoneof the first others have the characterof mono-

to explorethis fieldanddrawatten- thematic ricercars,tightly organized

tion to a great wealth of solo lute polyphonic works in which a single

musicworthyof consideration along melodic idea displays itself in all

with the vocalmusicof "thegolden voices. Sometimes the composer

age."13John Wilson'swork in this adopts the "broken" style so well

veincomesattheendof thatdevelop- suited to the naturalcapacitiesof his

ment(if, indeed,it belongswithinthe instrument.Here the harmonyis out-

sameframeof reference);a full ap- lined in arpeggiosand other broken

preciationof his contributionmust chord figurations, and the normal

awaitthe roundingout of the earlier three-voice writing is reduced to

detailsof the picture. two. Passagesof this kind are often

All thatwe knowof Wilson'ssolo introduced for purposes of contrast

lute compositionis containedin the between sections of chordal struc-

opening22 pages of his autograph ture.14

manuscript. Here is a set of 30 lute The most remarkablefeature of

pieces,actually 28 different composi- this group of lute pieces is the fact

tionssince2 of themarerepeatedin that they are all part of a large-scale

variantforms.They bearno distinc- tonal plan-a featurewhich does not

tivetitlesbutexamination revealsthat become apparentuntil one has ana-

they are freelycomposedlute fanta- lyzed the set as a whole. They com-

sias or, as Wilson'scontemporariesprise a unified collection of fantasias

mightprefer,lute voluntaries. They in every single major and minor key

areall in duplemeterandshownone and thus belong to that select group

of thecharacteristicsof stylizeddance of works of which Bach's Well-tem-

or variationforms,nor do they seem pered Clavieris the best known ex-

to be basedon specificvocal or in- ample.John Wilson's"well-tempered

strumental models.Harmonicinterest lute"may in fact claimthe distinction

outweighsmelodyas a rule,although of being the earliesteffort at

therearea numberof piecesin which matic compositionin all keys.15syste-

the uppervoice carnes a song-like The sequencefollowed by the com-

melody accompaniedby the lower poser in moving through the com-

voices.The typicalthree-voicelute plete system of keys is puzzling.The

style predominates, but the texture first fantasiais in A minor, the sec-

occasionallythickensto fouror even ond in Bb major, which seems to

fivepartsor thinsto a passagein two- promisean ascendingseriesof tonali-

voice writing. Apart from certain ties. The next three pieces, however,

generalsimilaritiesin style the pieces returnto the key of A (minor,

differwidelyin textureandconstruc- minor), followed by two in Ebmajor,

tion. Somemove in solemnchordal major

14 A detailed analysis of Wilson's lute style

treatmentfrom beginningto end; cannot be attempted here. The author is pre-

paring an edition of Wilson's lute music for

Lumsden. The first fruits of his research have publication in the near future, at which time

appeared in two articles, "The Sources of a fuller analysis will be undertaken.

English Lute Music (1540-1620)," The Galpin 15 It is impossible to determine the exact

Society Journal VI (July, 1953), pp. 14-22; date at which Wilson's lute pieces were writ-

and "The Lute in England," The Score, No. ten. They are found in a manuscript that was

8 (Sept., 1953), pp. 36-43. completed sometime before 1656, the date at

13 Richard Newton, "English Lute Music which it was accessioned by the Bodleian Li-

of the 'Golden Age,' " Proceedings of the brary. They are entered first in a collection of

Musical Association LXV (1938-9), pp. 63- more than 2oo songs. Probably they were com-

90. posed between 0640 and

I65o.

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE ART OF JOHN WILSON 105

"CURIOUS"7

and three in C (minor, minor, major). "tonality" must be used with some

Thereafter the compositions occur in qualifications in any discussion of

pairs with the minor key usually pre- mid-i7th-century music. The two

ceding the major, but the order of principal modes, major and minor,

key succession seems to have no ra- were well defined by this time, and

tional basis. The original order can they had begun to take on something

be observed in Table I below. of the affective contrast which we

TABLEI

ORIGINAL ORDER OF WILSON'S LUTE FANTASIAS*

I A minor [ 9] ii D minor [19] 21 Ab major

2 Bb major [Io] I2 D major 22 Ab minor

[ ] 3 A minor [II] 13

G minor [2o] 23 B minor

[ 2] 4 A major [21] 14 G major [21i] 24 B major

[ 3 5 A minor [13] 15 E minor 25 Cg (or Db) major

[4] 6 Eb major [14] 16 E major 26 CGminor

[ 5] 7 Eb major [15] 17 F minor 27 C# (or Db) major

[ 6] 8 C minor [16] 18 F major 28 F# minor

[ 7 1 9 C minor ['7] I9 Bb minor 29 Fg (or Gb) major

[ 8] io C major [18] 2o Bb major 3o Eb minor

* The fantasias have been numbered consecutively from I to 30 for purposes of

identification in the present paper. The numbers in brackets, from [11 to [z21], are

assigned in the original Ms. Nos. 2 and 20o are variants of the same composition; so

also are Nos. 25 and 27.

It is possiblethatthe orderin which ascribe to them today; but the har-

these pieces were enteredin the Bod- monic relationshipswithin any given

leian manuscriptwas tentative, and tonality were infinitely subtle and

that the composerintended to make varied, not yet having taken on the

a final selection of 24, one in each simple tonal perspective enforced

major and minor key, to constitute upon the harmonyof the classic pe-

the set. One can do no more than riod. Wilson pays his respectsto the

conjecture on this point, but there home key in the opening and closing

can be no doubt that the set was con- measuresof his fantasias,but between

ceived as a whole to demonstratethe these points he moves freely through

capacitiesof the lute for performance almost every triad in the chromatic

in all keys. The terms "key" and spectrum (see Ex. 7). After the point

From FantasiaNo. 5 in A Minor

Ex. 7

.. -- , I I IF 1 • i

Fq. •

j j ,J d ,,j b

_.

d"

; i

, I - • I,,

r

_.IJ.. 4 g" i 97

III I

_::| I r

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

IO6 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY

where the example breaks off, the technique. Wilson has freed himself

bass descends by semitones for ten completely from any dependence

measures. upon the scholastic forms, and his

Wilson was a practical,not a theo- venture into remote keys is restricted

retical, musician.So far as we know only by the skill of his hand and the

he had no theory of equal tempera- capacity of his instrument.

ment to advance,no new system of The lute was of course the ideal

lute tuning such as Thomas Mace at- instrumentfor harmonicexperimen-

tempted to promote as a means of tation. Charles van den Borren has

playing easily in remote keys.'6 His observed:19

approach was that of the virtuoso

anxiousto prove to his own satisfac- The lutanists, who were not troubled

tion that no technical problem was by the restrictive rules of vocal music and

of the traditional notation, and who had

beyond his skill. His accomplishment not to pay attention to the limits imposed

was probablyuniquefor its time, but

by unequal temperament of the keyboard

it cannot be said that he was out of instruments, preceded the virginalists in

touch with the spirit of his age, for the use of exceptional modifications. From

the I7th-centurywas as prone to ex- the first half of the, 6th century we find

perimentin the artsas in the scientific them making use of A-sharp, of D-flat, of

fields. Wilson's set of fantasiaswas a E-sharp, and even of F-double sharp.

kind of thesaurusof harmonicprac-

tice which had its precedentin some With such a flexiblemediumat their

of the scholastic pieces in the Fitz- disposal,it is surprisingto find that

william Virginal Book, for example, the English lutanistsbefore and after

John Bull's hexachordfancy, which Wilson were quite conservative in

introduces twelve statements of its their use of chromaticismand remote

subject, each on a differentdegree of keys. It may be that furtherexamples

the chromatic scale;"7 or, in another will come to light as our knowledge

medium, the younger Ferrabosco's of the lute repertoire grows, but

fantasia for viols which employs a David Lumsdenin a recent paperon

similar series of hexachordson suc- solo lute music in England calls at-

cessive steps of the chromaticscale, tentionto only two chromaticfancies

both ascendingand descending.'"But by Dowland as exemplifyingthe use

such hexachordcompositionscontain of "a device found nowhere else in

an element of archaismin the fact English lute music."20 Thomas Mace,

that their technique is basically an writing some 20 years after Wilson

extension of the old cantus firmus presentedhis manuscriptto the Bod-

leian, and not more than two years

16 Mace advocated what he called the "Flat after the composer'sdeath, presents

Tuning" as superior to the customary tuning, his readers with some examples of

particularly for playing in keys with many lute lessons in the key of B major

flats or sharps. See Musick's Monument

(1676), pp. 172-3. with the following statement: "And

17 Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (London and

now shall follow a sett in B-mi-key,

Leipzig, 1899), Vol. I, p. 183.

is See Ernest Walker's description of this Natural; which I never yet see set

fantasia in "An Oxford Book of Fancies,"

Musical Antiquary III (i912), pp. 65-73. An-

upon the Lute. It being a key (as

other 4-part version of the same work is found

some say) very Unapt, andImproper

in Cambridge, King's College, Rowe Library; 19 Charles van den Borren, The Sources of

and a 5-part version occurs in the recently Keyboard Music in England (London, 1913),

discovered Tregian Anthology (British Mu- p. 323n.

seum, Ms. Eger. 3665), o0David Lumsden, "The Lute in England."

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE iCURIOUS7 ART OF JOHN WILSON 107

to Compose anything in."21 What of the basses was variable, determined

would Mace have had to say about a by the key in which the performer

fantasia in CQ major or Eb minor? It was playing. Each tablature bears an

is obvious that he had no knowledge indication of the proper tuning for

of Wilson's work. His only purpose the particular piece involved. As one

in introducing what he considered an might expect from the character of

exceptional key was to demonstrate his lute songs. Wilson's forte as a vir-

the advantages of his own system of tuoso lay in his harmonic ingenuity.

"Flat Tuning." Elsewhere in Musick's The melodic writing is not ornate,

Monument (1676) he singles out decorated with embellishments or

John Dowland and Robert Johnson rapid divisions, but the complicated

as outstanding lute performers of the finger positions (stops) call for a left

old school, but there is no mention hand of considerable skill. Thomas

of John Wilson. There may be an Mace could have had Wilson's music

unwitting reference to our composer, in mind when he said: "Yea, such

however, in Mace's complaint that Stops have I seen, that I do still won-

the lute's decline in popularity was der how a Mans Hand could stretch

due largely to the fact that it had to perform some of them, and with

been cultivated as an esoteric instru- such swiftness of Time as has been

ment by virtuosi who did everything set down."'22

to encourage the belief that it was

Unhampered by the requirements

difficult to play. Wilson may have of text setting or the rhythms of dec-

been one of those who kept his art lamation, the composer could give

as a jealously guarded trade secret. free rein to his harmonic imagination.

Satisfied to be known as the "Pro- But there were problems as well as

found Orpheus" who could "ensnare

advantages resulting from the absence

the souls" of his listeners, he had no of a text; the composer was forced to

interest in sharing the secrets of his

organize his materials in purely mu-

technique with any other musician. sical terms since he had no lyric form

Wilson's virtuosity does not reveal to support the structure or dictate

itself in the expected ways. It is the details of expression. It is ex-

strange to find a skillful lutanist who tremely interesting to see how Wil-

does not seek to exploit the brilliance son, an habitual song composer, met

of his treble course, but Wilson rarely the problems of free composition.

moves above the third fret of his top His approach is definitely construc-

string. On the lower strings, how- tive rather than rhapsodic. The fan-

ever, he does not hesitate to go as tasias seem to have an improvisatory,

high as the tenth or eleventh fret. almost aimless, character at first

Evidently he preferred the richer glance, but closer analysis reveals

quality of the lower registers of his them to be organized with great care.

lute. The instrument was a 23- or A favorite device, and one which can

24-stringed tenor lute with six bass be recognized as a stereotype of Wil-

courses; it must have been character- son's style, is the use of long ascend-

ized by a fine resonance. The upper ing or descending lines in the bass,

six courses were tuned in the G-tun- sometimes chromatic as in Ex. 7,

ing common to most English lute sometimes diatonic as in the fantasia

music (G c f a d' g'), but the

tuning No. 27, in Db, where the Db major

21 Thomas Mace, Musick's Monument scale mounts in half notes through

(1676), p. I73. 22 Mace, op. cit., p. 41.

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

IO8 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY

two full octaves against eighth-note lead to an emphatic return to B ma-

passage work in the upper voice. Ex- jor, but the conclusion is prolonged

tended pedal points are fairly com- by the abrupt introduction of a ma-

mon, and sequential figures occur jor triad on the flat 7th degree (four

much more frequently than they do measures from the end). This par-

in the lute songs. The effect of con- ticular chord, not used elsewhere in

tinuity produced by the use of de- the piece, strikes the listener com-

ceptive cadences, so noticeable in the pletely unawares. In spite of the flag-

vocal pieces, is also present in the rant use of parallel 5ths in moving

lute solos. The sureness of Wilson's from a B major to an A major triad

harmonic sense is particularly evident in root position, the effect is calcu-

in the closing sections of his pieces. lated and sounds well in lute per-

He may wander far afield in his formance,

From Fantasia No. 24 in B Major

Ex. 8

modulations but he knows how to Several of the fantasias can be de-

dramatize the return to the tonic key scribed as 6tudes, or preludes, unified

-witness the concluding measures by the predominant use of a single

of fantasia No. 24 in B major (see idea: motif, rhythmic figure, or

Ex. 8). structural device. One of the most

Four measures of dominant pedal successful is No. 17, in F minor,

Beginning of Fantasia No. 17 in F Minor

Ex. 9

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE "CURIOUS)) ART OF JOHN WILSON 109

which is a study in suspensions. The is devoted to it. The passage moves

first thirteen measures are given in in a typical lute configuration of

Ex. 9. closely spaced triads in root position

Here again the bass is essentially and first inversion (see Ex. io).

From Fantasia No. 26 in C# Minor

Ex. io

a long descending line; the phrase An even more extreme example is

structure is irregular. Melodic in- found in the last fantasia, No. 30 in

terest is reduced to a minimum,but Eb minor. Here a passage very much

an effect of great expressivebeauty like the preceding is further clouded

is achieved through the use of de- by the use of appoggiaturas and aux-

layed resolutionsand accented pass- iliary notes. The result is a bewilder-

ing tones. ing flight into the realm of atonality

The texture becomes more com- which must have been extremely

plicated and the dimensionsof the confusing to the ears of I7th-cen-

works enlargeas the composermoves tury musicians. One can begin to ap-

into the more unusual keys. The preciate Henry Lawes's complaint

fantasiasare thus arrangedroughly that he had but a dull understanding

in an order of increasingdifficulty, of some of the departures in Wilson's

beginning with the simple, prelude- music (see Ex. i i).

like fantasiaNo. I in A minor to the It should be stated that this ex-

rich and highly involved No. 30 in ample and the one precedingare

Eb minor.The chromaticismlikewise contrastingsectionsof chromaticism

becomes more conspicuous toward placed between passages of chordal

the end of the series. When Wilson diatonic harmony. Wilson knew bet-

uses chromaticismhe uses it to ex- ter than to sustainsuch progressions

cess. All voices participate in the throughout the length of a complete

chromaticmotion. In his fantasiaNo. piece.

26, in Cg minor, a complete section One final exampleis requiredto

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

IIO JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY

From Fantasia No. 30 in Eb Minor

Ex. ii

show the way in which the com- composition seems to gather its mo-

poser handled a composition in poly- mentum deliberately; from mm. 20-

phonic style. Polyphony on the lute 30 the intervals between the entries

is at best a compromise. The lines are decreased, and the statements oc-

can be suggested but not sustained as cur in dominant progression (F#, B,

they can be by a group of voices or E, etc.), producing a stretto-like ef-

viols. Wilson accepts this limitation; fect. After a five measure episode

his polyphonic ideas are motific (mm. 30-35), the theme enters boldly

rather than linear. In this instance a in the dominant of E major, the har-

short theme, two measures in length, mony moves to a tonic pedal, and

is tossed from voice to voice, under- for the last seven measures the theme

going a series of harmonizations dissolves in a series of rhythmic

which reveal it in all possible tonal echoes of itself. Harmony controls

perspectives. The composer treats the development throughout-har-

the theme as though it were an ob- mony that is bold and willful and as

ject held up to the light, turned over, individually conceived as that of

examined from every point of view Frescobaldi. In fact, John Wilson's

(see Ex. I2). musical personality bears a close re-

This fantasia, No. I6 in E major, semblance to that of his Italian con-

is remarkable for the compactness of temporary, whom Willi Apel has

its design. The whole organization is aptly described as "a unique mixture

centered in a series of statements of of an imaginative artist and a reflec-

the brief theme. In the example the tive scholar."23 In his E major fan-

principal statements are indicated by tasia Wilson is working in a form

a line drawn above or below the no- which is superficially akin to the

tation; secondary or derived state- I6th-century instrumental canzona,

ments, by a dotted line. The first few 23 Willi Apel, Masters of the Keyboard

statements are separated so that the (Cambridge, Mass., 1947), p. 79.

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1

THE "CURIOUS ART OF JOHN WILSON III

FantasiaNo. I6 in E Major

Ex. I2

20

I I

a W m

It I F XI

A-- • •J : •

•-•, -..,..:

.

i..

. .. "

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

12 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY

but his treatment of the material is himself if he dared to venture be-

such as only a Baroque musician yond the safe confines of the stile

could have devised. antico. The ostinato bass and the

Anyone who attempts to make an strophic variation, which can be tedi-

objective evaluation of Wilson as a ous beyond measure in the hands of

composer may feel that his musician- an inferior composer, were attempts

ship is impaired by some rather ob- to solve the same problems of

vious deficiencies. For one thing, he structure. In the early 17th century

seems lacking in melodic skill, a fea- the traditional patterns of musical

ture which is noticeable in both his thought were disrupted as decisively

songs and his solo lute pieces. He will as they were some 300 years later in

often achieve an opening phrase of the opening years of the 20oth cen-

striking beauty but then fail to sus- tury, which is one of the reasons

tain the melodic interest. He has a why the early Baroque has such a

tendency to return too often to the fascination for our own time. Wilson

high point of his line thus destroying was apparently not attracted by the

its shape and balance. His melodic new developments in Italian music,

thought is tied too closely to de- but he could not have been ignorant

clamatory technique; he seldom ex- of them. He attempted, instead, to

hibits the fresh tunefulness that en- solve the problems in his own terms.

livens the work of William Lawes, Whatever his intrinsic worth as a

for example. Another fault stems composer, it is significant that a mu-

from his too rigid adherence to sche- sician of his kind could develop in

matic devices: extended stepwise mo- England during the first half of the

tion of the bass, excessive chromati-

i7th century. It suggests that the

cism, overworking of a particular generalizations so long accepted as to

motif. But these are faults which dis- the inferiority and provincialism of

appear if we give the composer the English music during that period

benefit of a historical evaluation; might bear reconsideration.

they grow from the predicament in

which every Baroque musician found Universityof California,Berkeley

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.191 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 08:51:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Wegman MakerComposerImprovisation 1996Document72 pagesWegman MakerComposerImprovisation 1996Ryan Rogers100% (1)

- Dont Op. 37 Galamian PDFDocument35 pagesDont Op. 37 Galamian PDFALEXANDRANo ratings yet

- 18th Century Secular Music - One Voice With (Out) BCDocument105 pages18th Century Secular Music - One Voice With (Out) BCFelipe100% (1)

- 17th Century Secular Music - One Voice With ContinuoDocument203 pages17th Century Secular Music - One Voice With ContinuoFelipeNo ratings yet

- Charles Ives PDFDocument47 pagesCharles Ives PDFNalles.100% (1)

- Hudson BassanoDocument18 pagesHudson Bassanosinderesi100% (1)

- The Music of Henry CowellDocument27 pagesThe Music of Henry CowellPablo AlonsoNo ratings yet

- British Music HistoryDocument23 pagesBritish Music HistoryAna Adiaconitei100% (1)

- Mensural Notations InformationDocument12 pagesMensural Notations InformationTheodor77100% (1)

- Scales & Arpeggios For Cello - Rehearsal EditionDocument127 pagesScales & Arpeggios For Cello - Rehearsal EditionMUSICAL BAIRES100% (1)

- Riam Scales ArpeggiosDocument92 pagesRiam Scales ArpeggiosAengus RyanNo ratings yet

- Art Music 3 Baroque Era Study GuideDocument4 pagesArt Music 3 Baroque Era Study Guidethot777No ratings yet

- The "Curious" Art of John WilsonDocument20 pagesThe "Curious" Art of John WilsonZappo22100% (1)

- Mary Chan - Edward Lowe's Manuscript British Library Add MS 29396Document16 pagesMary Chan - Edward Lowe's Manuscript British Library Add MS 29396FelipeNo ratings yet

- John P. Cutts - Edinburgh University Library Music Ms. Dc. 1. 69Document27 pagesJohn P. Cutts - Edinburgh University Library Music Ms. Dc. 1. 69FelipeNo ratings yet

- Ars Nova John Taverner IDocument2 pagesArs Nova John Taverner Iwalter allmandNo ratings yet

- Charles Ives and His WorldFrom EverandCharles Ives and His WorldJ. BurkholderRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Amphitheatrvm Sapientiae AeternaeDocument550 pagesAmphitheatrvm Sapientiae AeternaeConst VassNo ratings yet

- Charles IvesDocument47 pagesCharles Ivesfgomezescobar100% (1)

- New Shakespeare TheoryDocument18 pagesNew Shakespeare TheoryJOHN HUDSON100% (2)

- British Music Through The AgesDocument7 pagesBritish Music Through The AgesJulienne PapeNo ratings yet

- Final Paper Proposal - Paige SalynDocument9 pagesFinal Paper Proposal - Paige SalynPaige SalynNo ratings yet

- The Woman Who Wrote Shakespeare A Research OverviewDocument15 pagesThe Woman Who Wrote Shakespeare A Research OverviewJOHN HUDSON100% (2)

- Francis Johnson: BiographyDocument2 pagesFrancis Johnson: BiographyReubenPompeiNo ratings yet

- Francis JohnsonDocument2 pagesFrancis JohnsonReubenPompeiNo ratings yet

- THE TEACHING OF SAXOPHONE OVER TIME: From Adolphe Sax to the present dayFrom EverandTHE TEACHING OF SAXOPHONE OVER TIME: From Adolphe Sax to the present dayNo ratings yet

- Vincent Duckles - The Gamble Manuscript As A Source of Continuo Song in EnglandDocument19 pagesVincent Duckles - The Gamble Manuscript As A Source of Continuo Song in EnglandFelipe100% (1)

- Gorboduc or Ferrex and PorrexDocument144 pagesGorboduc or Ferrex and PorrexO993100% (1)

- Sara Itzig SalonDocument39 pagesSara Itzig SalonSandra Myers BrownNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument2 pagesPDFkiss8andrea8iriszNo ratings yet

- Another Time and Place: A Brief Study of the Folk Music RevivalFrom EverandAnother Time and Place: A Brief Study of the Folk Music RevivalNo ratings yet

- Arnold BaxDocument14 pagesArnold BaxIain Cowie100% (2)

- Josquin IntroDocument13 pagesJosquin IntroRuey YenNo ratings yet

- Chapter4 - Part1Document33 pagesChapter4 - Part1Thanh TúNo ratings yet

- Peel - in Summertime On Bredon (Gervase Elwes, Tenor, 1916)Document2 pagesPeel - in Summertime On Bredon (Gervase Elwes, Tenor, 1916)robo707No ratings yet

- Atestat AndreeaDocument25 pagesAtestat AndreeaMihaela Monica MotorcaNo ratings yet

- History of Music EssayDocument4 pagesHistory of Music EssayMaisie JaneNo ratings yet

- Western MusicDocument11 pagesWestern MusicAnika Nawar100% (2)

- Booklet - Classical KirkbyDocument32 pagesBooklet - Classical KirkbyFelipeNo ratings yet

- Gorboduc 1Document149 pagesGorboduc 1Fr Joby PulickakunnelNo ratings yet

- Music in ShakespeareDocument523 pagesMusic in ShakespeareMarc Demers100% (4)

- Annotated Bibliography Primary SourcesDocument11 pagesAnnotated Bibliography Primary Sourcesapi-277596160No ratings yet

- Our True North' - Walton's First Symphony, Sibelianism, and The Nationalization of Modernism in EnglandDocument23 pagesOur True North' - Walton's First Symphony, Sibelianism, and The Nationalization of Modernism in EnglandtrishNo ratings yet

- Famous Composers and Their Works (Vol. 1&2): Biographies and Music of Mozart, Beethoven, Bach, Schumann, Strauss, Verdi, Rossini, Haydn, Franz…From EverandFamous Composers and Their Works (Vol. 1&2): Biographies and Music of Mozart, Beethoven, Bach, Schumann, Strauss, Verdi, Rossini, Haydn, Franz…No ratings yet

- Midieval Period Hildegard Von BingenDocument10 pagesMidieval Period Hildegard Von BingenLhen NonanNo ratings yet

- Sir Watkin Williams Wynn and The Rutgers Handel Collection : by MartinpickerDocument15 pagesSir Watkin Williams Wynn and The Rutgers Handel Collection : by MartinpickerSixtusNo ratings yet

- Not Necessarily English MusicDocument3 pagesNot Necessarily English MusicHeoel GreopNo ratings yet

- Music of New York - The New Grove Dictionary of Music and MusiciansDocument44 pagesMusic of New York - The New Grove Dictionary of Music and MusiciansPedro R. PérezNo ratings yet

- Sesiunea de Comunicări Științifice Limba Engleză: The English RenaissanceDocument12 pagesSesiunea de Comunicări Științifice Limba Engleză: The English RenaissanceAnonymous C8GSwW9wedNo ratings yet

- James Joyce and Avant-Garde MusicDocument11 pagesJames Joyce and Avant-Garde MusicVictoria GianeraNo ratings yet

- Band History EssayDocument7 pagesBand History EssayThomas SwatlandNo ratings yet

- Arnold BaxDocument18 pagesArnold BaxBob LablaNo ratings yet

- The Accordion and The Polka in Polish-American Ethnic MusicDocument3 pagesThe Accordion and The Polka in Polish-American Ethnic MusicVictorGomezNo ratings yet

- From Chaucer to Tennyson: With Twenty-Nine Portraits and Selections from Thirty AuthorsFrom EverandFrom Chaucer to Tennyson: With Twenty-Nine Portraits and Selections from Thirty AuthorsNo ratings yet

- Henry Purcell - A Sketch of A Busy Life Author(s) : Percy A. Scholes Source: The Musical Quarterly, Jul., 1916, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Jul., 1916), Pp. 442-464 Published By: Oxford University PressDocument26 pagesHenry Purcell - A Sketch of A Busy Life Author(s) : Percy A. Scholes Source: The Musical Quarterly, Jul., 1916, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Jul., 1916), Pp. 442-464 Published By: Oxford University PressLeon MilkaNo ratings yet