Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sensitive Periods C38

Sensitive Periods C38

Uploaded by

Gavi NnamdiCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Advanced Legal Writing, Third Edition Theories and Strategies in Persuasive Writing, Third Edition (Michael R. Smith)Document615 pagesAdvanced Legal Writing, Third Edition Theories and Strategies in Persuasive Writing, Third Edition (Michael R. Smith)Sovanrangsey Kong100% (2)

- The Role of The Assistant in A Montessori Classroom: Sandra Girl ToDocument5 pagesThe Role of The Assistant in A Montessori Classroom: Sandra Girl ToKesia AvilesNo ratings yet

- Montessori Adolescent Methodology - ENDocument55 pagesMontessori Adolescent Methodology - ENMarcel CapraruNo ratings yet

- Desarrollo SocialDocument16 pagesDesarrollo SocialNalleli CruzNo ratings yet

- Independence:: A Montessori JourneyDocument6 pagesIndependence:: A Montessori JourneyAndrea Lovato100% (2)

- How To Raise An Amazing Child The Montessori Way, 2nd Edition: A Parents' Guide To Building Creativity, Confidence, and Independence - Tim SeldinDocument4 pagesHow To Raise An Amazing Child The Montessori Way, 2nd Edition: A Parents' Guide To Building Creativity, Confidence, and Independence - Tim SeldinzusohunuNo ratings yet

- Maria MontessoriDocument5 pagesMaria Montessoriniwdle1No ratings yet

- Essay - PleDocument18 pagesEssay - PleKshirja SethiNo ratings yet

- Maria Montessori - Biography - Academic, Educator - Biography PDFDocument4 pagesMaria Montessori - Biography - Academic, Educator - Biography PDFkoldo10100% (2)

- Ssignment Odule: S B: M .S KDocument14 pagesSsignment Odule: S B: M .S Ksaadia khanNo ratings yet

- Human Needs and TendenciesDocument9 pagesHuman Needs and TendenciesHeidi Quiring0% (1)

- Define The Term Sensitive PeriodsDocument3 pagesDefine The Term Sensitive PeriodsBéla Soltész100% (4)

- In Casa de BambiniDocument2 pagesIn Casa de Bambiniparadise schoolNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Preliminary Activities C38Document2 pagesIntroduction To Preliminary Activities C38Marinella PerezNo ratings yet

- Life and Works of DrMAriaDocument19 pagesLife and Works of DrMAriaSa100% (1)

- Human TendenciesDocument9 pagesHuman TendenciesBinduNo ratings yet

- The NAMTA Journal - Vol. 39, No. 2 - Spring 2014: Ginni SackettDocument20 pagesThe NAMTA Journal - Vol. 39, No. 2 - Spring 2014: Ginni SackettSaeed Ahmed BhattiNo ratings yet

- Nebulae 0Document3 pagesNebulae 0delia atenaNo ratings yet

- Maria Montessori BioDocument3 pagesMaria Montessori Bioapi-395431821No ratings yet

- Intro To MathDocument22 pagesIntro To MathMonwei YungNo ratings yet

- Slogan (We Follow The Child)Document9 pagesSlogan (We Follow The Child)paradise schoolNo ratings yet

- Epilogue 0 - The Child and The EnvironmentDocument14 pagesEpilogue 0 - The Child and The EnvironmentkatyarafaelNo ratings yet

- 3period LessonokprintDocument3 pages3period LessonokprintFresia MonterrubioNo ratings yet

- History of MontessoriDocument19 pagesHistory of MontessoriRazi AbbasNo ratings yet

- Montessori PrinciplesDocument6 pagesMontessori Principlesapi-269680928No ratings yet

- Developmental Delays and Movement in Relation To Instinct Harriet Jane A AlejandroDocument36 pagesDevelopmental Delays and Movement in Relation To Instinct Harriet Jane A AlejandroNeil Christian Tunac CoralesNo ratings yet

- Module 1 AssignmentDocument18 pagesModule 1 AssignmentQurat-ul-ain abroNo ratings yet

- The First Plane of DVP - Birth To Age 6 - Montessori Philosophy PDFDocument3 pagesThe First Plane of DVP - Birth To Age 6 - Montessori Philosophy PDFMahmoud BelabbassiNo ratings yet

- Citizen of The WorldDocument3 pagesCitizen of The WorldOrieri brianNo ratings yet

- Amiusa Maria Montessori Biography2 PDFDocument2 pagesAmiusa Maria Montessori Biography2 PDFDunja Kojić ŠeguljevNo ratings yet

- Why Children Bully - Himpsi SumutDocument62 pagesWhy Children Bully - Himpsi Sumutfajar zakiNo ratings yet

- Ami School Standards 7092Document2 pagesAmi School Standards 7092Dunja Kojić ŠeguljevNo ratings yet

- Course 37 Practical Life Presentation Outlines 5kb2Document32 pagesCourse 37 Practical Life Presentation Outlines 5kb2Kreativ MontessoriNo ratings yet

- AMI Montessori Observation Refresher 2019Document10 pagesAMI Montessori Observation Refresher 2019AleksandraNo ratings yet

- The Ten Secrets of MontessoriDocument4 pagesThe Ten Secrets of MontessoriJessa Resuello FerrerNo ratings yet

- Oral Language in The Montessori ClassroomDocument5 pagesOral Language in The Montessori ClassroomLarson ChinNo ratings yet

- Montessori Question and Ans SheetDocument13 pagesMontessori Question and Ans SheetJayantaBeheraNo ratings yet

- Observation 1987 London UpdatedDocument3 pagesObservation 1987 London UpdatedAleksandraNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3Document20 pagesLesson 3Kassandra KayNo ratings yet

- Module 5 Raeesa D-17230Document21 pagesModule 5 Raeesa D-17230Raeesa ShoaibNo ratings yet

- TreasureArticle2022 01-1Document9 pagesTreasureArticle2022 01-1Marizz DuduNo ratings yet

- The Absorbent MindDocument1 pageThe Absorbent MindUzma MazharNo ratings yet

- 5 GlasgowDocument24 pages5 Glasgowbentarigan77100% (1)

- Absorbent Mind and Sensitive Periods PDFDocument2 pagesAbsorbent Mind and Sensitive Periods PDFЕкатеринаNo ratings yet

- Montessori Method - Final Assignment 1 - 22 MAY 2022Document11 pagesMontessori Method - Final Assignment 1 - 22 MAY 2022Jennifer BotheloNo ratings yet

- Human Interdependencies HelenaDocument15 pagesHuman Interdependencies HelenahelenareidNo ratings yet

- Montassori Module 2Document23 pagesMontassori Module 2Ahmed0% (1)

- Example and Definition: Sensitive Periods Is A Term Developed by The Dutch Geneticist Hugo de Vries and Later UsedDocument10 pagesExample and Definition: Sensitive Periods Is A Term Developed by The Dutch Geneticist Hugo de Vries and Later UsedMehakBatla100% (1)

- IQRA NAYYAB - D18333 - Module 2 - Assisgnment 2Document21 pagesIQRA NAYYAB - D18333 - Module 2 - Assisgnment 2iqra Ayaz khanNo ratings yet

- Six "Sensitive Periods": by Maria MontessoriDocument2 pagesSix "Sensitive Periods": by Maria Montessoridelia atenaNo ratings yet

- PMC Module Three Assignment Misbah.....Document19 pagesPMC Module Three Assignment Misbah.....Misbah AmjadNo ratings yet

- Arts Integration in Montessori MathematicsDocument21 pagesArts Integration in Montessori MathematicsLorena MaglonzoNo ratings yet

- Montessori Practical LifeDocument3 pagesMontessori Practical LifeSiti ShalihaNo ratings yet

- Q2 M 1requirements To Start House of ChildremDocument3 pagesQ2 M 1requirements To Start House of ChildremNighat Nawaz100% (4)

- ED411077Document92 pagesED411077katyarafaelNo ratings yet

- 6 Sensitive Periods in Montessori CurriculumDocument2 pages6 Sensitive Periods in Montessori Curriculumaina adrianaNo ratings yet

- MontessoriDocument14 pagesMontessori4gen_3No ratings yet

- Culture 1 (Geography and History)Document10 pagesCulture 1 (Geography and History)Sadaf KhanNo ratings yet

- Names: Gulshan Shehzadi Roll# D17090 Topic: Exercise of Practical Life (EPL)Document18 pagesNames: Gulshan Shehzadi Roll# D17090 Topic: Exercise of Practical Life (EPL)Gulshan ShehzadiNo ratings yet

- SensorialDocument10 pagesSensorialMonwei YungNo ratings yet

- Images of Animals For School (AutoRecovered) 1Document24 pagesImages of Animals For School (AutoRecovered) 1Gavi NnamdiNo ratings yet

- I Am A Member of The Boa FamilyDocument2 pagesI Am A Member of The Boa FamilyGavi NnamdiNo ratings yet

- Review of The Nigerian Economy in 2020 and Key Priorities For 2021 and BeyondDocument27 pagesReview of The Nigerian Economy in 2020 and Key Priorities For 2021 and BeyondGavi NnamdiNo ratings yet

- Social Development C38Document15 pagesSocial Development C38Gavi NnamdiNo ratings yet

- What Makes A New Business Start-Up Successful?: ArticleDocument19 pagesWhat Makes A New Business Start-Up Successful?: ArticleGavi NnamdiNo ratings yet

- Ethics MIDTERMSDocument3 pagesEthics MIDTERMSClaire Jacynth FloroNo ratings yet

- Calasanz-My BodyDocument6 pagesCalasanz-My BodyALDOUS GABRIEL MIGUELNo ratings yet

- 3 PR2 ManuscriptDocument71 pages3 PR2 Manuscriptkyla villarealNo ratings yet

- 5 Generation Warfare and Social Media: ST THDocument2 pages5 Generation Warfare and Social Media: ST THSheikh AmmaraNo ratings yet

- Stephen R. Anderson - The Language OrganDocument285 pagesStephen R. Anderson - The Language Organioana_mariaro8144100% (2)

- Artificial Intelligence Unit 1 NotesDocument34 pagesArtificial Intelligence Unit 1 NotesSa InamdarNo ratings yet

- Prieto Ramos FernandoDocument10 pagesPrieto Ramos FernandoHojaAmarillaNo ratings yet

- A Nonviolent Communication (NVC) Cheat Sheet: Spare Time PhilosophyDocument1 pageA Nonviolent Communication (NVC) Cheat Sheet: Spare Time PhilosophyMiguel Barata GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Trends Networks and Critical Thinking in The 21st CenturyDocument13 pagesModule 2 Trends Networks and Critical Thinking in The 21st CenturyGhol Ocray BonaobraNo ratings yet

- Ed 105 Module 7 10 Answer The Activities HereDocument24 pagesEd 105 Module 7 10 Answer The Activities HereJodelyn Quirao AlmarioNo ratings yet

- Oral Presentation Rubric IngvDocument1 pageOral Presentation Rubric Ingvjose angelNo ratings yet

- Bleach CYOADocument3 pagesBleach CYOAJoão Pedro FariasNo ratings yet

- Ethical Requirements: Prepared By: Group 7Document26 pagesEthical Requirements: Prepared By: Group 7Maica A.No ratings yet

- Purposive Communication Reviewer .1Document9 pagesPurposive Communication Reviewer .1Ash JuamanNo ratings yet

- Framework of The StudyDocument21 pagesFramework of The StudyJuanito II BalingsatNo ratings yet

- UTS Finals CoverageDocument11 pagesUTS Finals CoverageAjiezhel NatividadNo ratings yet

- CMM-4050 Theories of Perfsuasion: Spring 2019Document11 pagesCMM-4050 Theories of Perfsuasion: Spring 2019ElsiechNo ratings yet

- Lesson 10 - Drawing Out Patterns and Themes From DataDocument31 pagesLesson 10 - Drawing Out Patterns and Themes From DataJames Andrei CaguiclaNo ratings yet

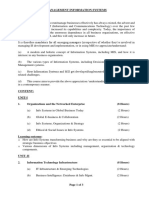

- Management Information Systems Course ObjectivesDocument3 pagesManagement Information Systems Course ObjectivesAakash AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Week 4 Purposive CommunicationDocument16 pagesWeek 4 Purposive CommunicationJerusha Shane Dueñas SadsadNo ratings yet

- Ai1 2Document41 pagesAi1 2Head CSEAECCNo ratings yet

- The Image of The City Book ReviewDocument3 pagesThe Image of The City Book ReviewSharique ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Annotation. in This Article An Important Assumption of Discourse Analysis IsDocument5 pagesAnnotation. in This Article An Important Assumption of Discourse Analysis IsNguyễn Hoàng Minh AnhNo ratings yet

- Grade 12 LM PR2 1 Module3Document45 pagesGrade 12 LM PR2 1 Module3Romnick CosteloNo ratings yet

- Prof Ed 6Document2 pagesProf Ed 6KAYE ESCOBARNo ratings yet

- IntroPhiloSHS Q4 Mod1 Version5 BaoDocument14 pagesIntroPhiloSHS Q4 Mod1 Version5 BaoClark崎.No ratings yet

- Minds: Margaret DonaldsonDocument180 pagesMinds: Margaret DonaldsonAnnie AloyanNo ratings yet

- Quiz CommunicationDocument9 pagesQuiz CommunicationAlishba ZubairNo ratings yet

- An Application of Lefebvere's SpaceDocument13 pagesAn Application of Lefebvere's Spacepinkish zahraNo ratings yet

Sensitive Periods C38

Sensitive Periods C38

Uploaded by

Gavi NnamdiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sensitive Periods C38

Sensitive Periods C38

Uploaded by

Gavi NnamdiCopyright:

Available Formats

Sensitive Periods

The Sensitive Periods

Introduction

Today we will examine the second of the unique Powers which Dr. Montessori identified in the First Plane of

Development. She called this second power “The Sensitive Periods”. As with “The Absorbent Mind”, the

identification of the Sensitive Periods is a fundamental Montessori discovery – a significant and original

contribution to the understanding of early childhood development. This discovery emerged from the

observation of children all over the world, interpreted in the light of Montessori’s intuitive insights and her

contemporary scientific knowledge. The Sensitive Periods, then, are yet another universal human

characteristic, a phenomenon of development exhibited by all children regardless of their era or culture.

With this examination of the Sensitive Periods we will also complete our picture of the mechanisms of self-

construction in the First Plane of Development. So let’s look for a moment at the pieces of that picture

already in place.

We started with the Human Tendencies – universal, innate human traits which guide human development

and motivate human behavior, already present at birth, and active throughout life. Next, we examined the

four stages or Planes of Development – each with its particular tasks, needs, and creations – which result in

the construction of an individual human adult. Then we narrowed our focus to the First Plane of

Development: a stage of extraordinary creative activity guided by two additional powers which are active

only during this First Plane – The Absorbent Mind, the special mentality present as a motivating and

creative power throughout the First Plane of Development; and now, The Sensitive Periods, which we will

recognize as very specific powers present only for certain times and for limited purposes during the First

Plane, after which they disappear. 1

1 th

As with the Absorbent Mind, the 20 century provided increasing recognition of what Montessori termed “Sensitive

Periods” during the formative stage of human development. In 1950, Norbert Wiener was able to suggest their

existence as an extrapolation of language development: “… what evidence there is goes to show that there is a

critical period during which speech is most readily learned; and that if this period is passed over without contact with

one’s fellow human beings of whatever sort they may be, the learning of language becomes limited, slow, and highly

imperfect. … This is probably true of most other abilities which we consider to be natural skills … (such as, movement,

visual development, etc.)”, in The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society, Boston: Houghton Mifflin,

1950. Evidence multiplied during the second half of the century, expanding our picture of early brain development.

See, for example, Ronald Kotulak Inside the Brain: Revolutionary Discoveries of How the Mind Works, Kansas City:

Andrews & McMeel, 1996, p. 7: “Information flows easily into the brain through ‘windows’ that are open for only a

short duration. These windows of development occur in phases from birth to age 12 when the brain is most actively

learning from its environment. It is during this period and especially the first three years that the foundations for

thinking, language, vision, attitude, aptitudes and other characteristics are laid down. Then the windows close, and

much of the fundamental architecture of the brain is complete.” Richard Restak offered a description of what could

be happening at the cellular level during these “critical periods” or “windows of opportunity”: “… the brain literally

creates itself during our earliest development. At various times in the developmental process from fetus to newborn

to infant, nerve cells migrate, many die off, and many others stick to one another and send out processes whereby

neuronal connections are formed and re-formed. This orchestration depends upon sensitivities on the part of the

developing brain to place (the effect of other cells in the immediate area), time (the brain develops in designated

stages, and if development is thwarted the brain often cannot later compensate), and the chemical and electrical

activity of neighboring neurons.” in Brainscapes: An Introduction to What Neuroscience Has Learned about the Structure, Function,

and Abilities of the Brain. New York: Hyperion, 1995, pp. 93-94.

©Ginni Sackett – Montessori Institute Northwest 1

No portion may be reproduced without express written permission from the author Course 38

Sensitive Periods

We have already seen that for Montessori, growth from conception to adulthood is not a vague

“progressive accumulation of material”; nor an “inherent hereditary necessity”, shaped by our genes

towards a limited set of pre-determined characteristics. Rather, she saw growth as “… a process

meticulously guided by transient instincts which give an acute sensibility and an impulse towards specific

forms of activity …”. Furthermore, these acute sensibilities and specific forms of activity “often differ very

plainly from the activities of the individual in the adult state”. 2

How have we seen this already? Well, in all of the Planes of Development, we see different and specific,

attractions to certain activities and experiences which ebb and flow as necessary developmental learning is

accomplished: we saw, for example, that in the Second Plane of Development, the Human Tendencies of

Abstraction and Imagination take on an intense developmental power or significance. Similarly, in the Third

Plane, there is the new attraction to explore interpersonal human relationships; which contrasts with the

Second Plane child’s intense interest in the dynamics of life in a fixed social group with definite rules, roles,

and expectations.

Such powers, attractions, and motivations are not “willed” in a conscious or adult sense. They emerge

naturally, spontaneously and unconsciously; and they are universally exhibited – they are the psychological

equivalent of such physiological phenomena of growth as the pre-determined appearance and

disappearance of the teeth during childhood.

These psychological powers guiding growth and development can be assisted, thwarted, or obstructed; but

their appearance cannot be controlled from outside the individual who experiences them. And certainly,

these transient and variable sensibilities, powers, and attractions can be very different from the

manifestations of normal, conscious adult behavior.

Among these “transient instincts”, meticulously guiding growth, we found a unique unconscious mentality

present only during the First Plane of Development – the Absorbent Mind: a power for growth, self-

construction, and adaptation which is present at birth and then disappears by age six. The particular powers

which we will call Sensitive Periods are also found only in the First Plane of Development. They appear at

birth for very specific developmental purposes, and disappear during the First Plane according to their

own developmental time tables.

These Sensitive Periods are unique, even among the many temporary powers and sensibilities which

emerge and subside throughout the Four Planes of Development. They guide the formation of very specific

sensibilities and characteristics. In particular, we will be thinking of Sensitive Periods as those sensitivities in

human development that are unique to the First Plane of Development.

2

The Secret of Childhood, pp. 35; 211

©Ginni Sackett – Montessori Institute Northwest 2

No portion may be reproduced without express written permission from the author Course 38

Sensitive Periods

Definition and Description of Sensitive Periods

We can define Sensitive Periods as:

Laws of development that provide an inner guide leading to the attainment of specific

sensibilities or characteristics

According to this definition, Sensitive Periods guide formations or characteristics which are essential to

human psychic life and which can only be created during the First Plane of Development. We will identify

four Sensitive Periods. 3 They can be summarized according to their essential formations (or outcomes), as

follows:

• Sensitive Period for Order (birth through age 4 ½)

Guides the formation of mental structures necessary for the emergence of human intelligence; and

organizes the child’s experience to provide the foundation for all aspects of the child’s adaptation

to his time and place

• Sensitive Period for Coordination of Movement (birth through age 4 ½ / 5)

Guides the formation of physical movement of the body and the hand, movement which is directed

purposefully by the Mind (specifically, by the mental power known as the Will)

• Sensitive Period for Development & Refinement of Sensory Perception (birth through age 4 ½)

Guides continual development and refinement of perception through the five senses (touch, smell,

taste, hearing, and vision or sight) leading to: first, the classification of sensory impressions; and,

second, the formation of abstractions for sensory experience (memory).

• Sensitive Period for Language (birth through age 6)

Guides the formation of the specific human language (or languages) used for spoken

communication in the child’s environment

The work of these four Sensitive Periods occurs during specific, parallel age-spans in the First Plane of

Development. Each Sensitive Period has very clear developmental goals – very specific and essential

formations (see appended Outlines for each Sensitive Period). The degree to which a child attains these

essential, developmental formations of being human will influence all of his future development in a

fundamental way. In fact, all future development will be contingent upon these creations and the quality of

their attainment.

3

There has been some debate as to the number of Sensitive Periods and more than four have, at times, been

identified. For example, a fifth sensitive period is sometimes named, focusing on Socialization or Social Relations. See

Constance Corbett, “Sensitive Periods”, AMI COMMUNICATIONS #2-3, 1995, pp. 38-45. These aspects of social

development seem, however, to be more related to the constructive work of adaptation accomplished by the

Absorbent Mind. See, for example, Chapters 22 & 23 in The Absorbent Mind, (1949) Claude A. Claremont, trans. New

York: Dell Publishing, 1967.

©Ginni Sackett – Montessori Institute Northwest 3

No portion may be reproduced without express written permission from the author Course 38

Sensitive Periods

Origins of the Term

The Dutch biologist and geneticist, Hugo DeVries (1848-1935), first identified and named Sensitive Periods

in 1902, through his study of insects. In The Secret Of Childhood, Montessori cites DeVries’ example of a

Sensitive Period in the caterpillar of the Porthesia butterfly. Here is Montessori’s description:

(The caterpillar) must feed on very tender leaves, and yet the butterfly lays its eggs in the most

hidden fork of the branch, near the trunk of the tree. Who will show the little caterpillars hidden

there, the moment they leave the egg, that the tender leaves they need are to be found at the

extreme tip of the branch, in the light? Now the caterpillar is strongly sensible to light; light

attracts it, summons it as by an irresistible voice, fascinates it, and the caterpillar goes wriggling

towards where the light is brightest, till it reaches the tip of the branch, and thus finds itself,

famished for food, among the budding leaves that can give it nourishment. It is a strange fact

that when the caterpillar has passed through its first stage and is full grown, it can eat other food,

and then loses its sensibility to light. This has been proved in scientific laboratories where there

are neither trees nor leaves but only the caterpillar and the light. 4

Montessori observed that very young children also exhibit such irresistible attractions to particular

activities or objects in their environment. She further recognized that through these irresistible activities or

objects, growth and development – self-construction – occur. As with the caterpillar, so also for children:

these attractions appear for a set time and a definite, pre-determined purpose, then disappear.

Montessori found that the facts of Sensitive Periods in other life forms can guide our understanding of these

observable phenomena in human children. She writes:

The great difference lies between an animating impulse leading to the performance of wonderful,

staggering actions, and an indifference that brings blindness and inaptitude. The adult can do

nothing from the outside that will affect these different states. 5

We can summarize Sensitive Periods as follows:

• The Sensitive Periods are exclusive to the first Plane of Development: their work is directed towards

the fundamental Self-Construction of the Psychic Being (or individual personality). 6

• Sensitive Periods are unconscious powers for growth.

4

Maria Montessori. The Secret Of Childhood. (1936) Barbara Barclay Carter, trans. Hyderabad: Orient Longman LTD,

1978, p. 35

5

The Secret Of Childhood, p. 36

6

Sensitivities and Powers which motivate growth and development in subsequent planes will build upon this

foundation of self-construction as accomplished in the first plane. In later planes, there is a severe limit in the capacity

to re-mediate missing pieces or incomplete constructions intended through the activity of Sensitive Periods in the first

plane: the earlier the intended construction, the more irremediable; and such remediation as is possible, will require

deliberate, conscious effort. The “second chance” offered in the second, conscious phase of the Absorbent Mind (c.

age 3-6) might also be the “last chance” for the earliest constructions motivated by the Sensitive Periods.

©Ginni Sackett – Montessori Institute Northwest 4

No portion may be reproduced without express written permission from the author Course 38

Sensitive Periods

• Sensitive Periods guide psychological development – psychological development which is manifested

through physical development as well.

• While present, they are intransigent, purposeful, and particular. They work in accordance with an inner

guidance which is inaccessible to external motivations. As unconscious, internal guides, they direct the

child’s attention towards specific aspects of the environment and towards specific circumstances which

are favorable for self-construction; and they motivate activity which will result in the necessary

psychological formations.

• The Sensitive Periods are transitory – appearing and disappearing at predictable times and in

predictable sequences. Once a Sensitive Period has ended, once the window of opportunity closes,

opportunities for the unconscious self-construction it offers also end.

• Sensitive Periods make particular use of the totality images taken in by the Absorbent Mind. [These

images have been absorbed under the guidance of the Horme, and particularly through the specialized

motivations of the various Nebulae.] One might think of these absorbed totality images as a large box

of photographs mixed and stored somewhat at random. Each Sensitive Period selects those totality

images (particular photographs) which are relevant to its developmental goals; the activity motivated

by the Sensitive Period then organizes these images (as one might organize the photographs into books

according to specific categories or topics), thereby creating a new psychological structure in the

emergent conscious mind.

Pattern of a Sensitive Period at Work

The four Sensitive Periods function simultaneously and parallel to each other. As can be seen, their work is

far from random. The child moves from one to the other, according to inner directives which are immune

to outside influence. We shall see that there are very specific sequences within each Sensitive Period,

guiding the child to incremental acquisitions; in this way, creations build one upon another in a specific

order. Once in place, specific creations made possible through one particular Sensitive Period may be

employed in later constructive work. There are recognizable patterns to the work of a Sensitive Period:

Psychic Work Precedes Activity

When we examined The Absorbent Mind, we saw that in human development psychic work

precedes any expression of that psychic work through activity: hidden mental work occurs

unnoticed, followed by overt expressions made possible by the interior constructions. This same

pattern is seen with The Sensitive Periods, leaving an impression of activity which ebbs and flows

throughout the time of a Sensitive Period’s constructive work: “The facts of creation and

conservation remain hidden”, Montessori writes; “no one notices the imperceptible outward

signs of the creative working of life … 7

7

The Secret of Childhood, p. 41

©Ginni Sackett – Montessori Institute Northwest 5

No portion may be reproduced without express written permission from the author Course 38

Sensitive Periods

Motives of Activity Are Selected

As we know, totality images from the environment are constantly being absorbed, and stored in the

unconscious memory (or Mneme) by The Absorbent Mind. A Sensitive Period purposefully focuses

on just those totality images which are relevant to its particular psychic work. In this way, certain

objects or circumstances in the child’s environment are selected for the child’s activity. Montessori

writes that “… development takes place by means of the outer world”. This outer world – the

environment – provides the necessary means of psychic life, “… just as the body, by eating and

breathing, takes from its outer environment the necessary means of physical life”. 8

Once the items of the environment have been selected, they serve as Motives of Activity:

motivations to act in such a way as to accomplish the specific constructive work. Once they are

selected, growth and development will depend upon these particular, selected items, or similar

items – similar motives of activity – being available. Montessori describes this as a life “…

spontaneously evolving at the expense of its outer environment”; and she notes the mystery

which lies at the heart of this phenomenon: “In these sensitive relations between the child and

his environment lies the key to the mysterious recess in which the spiritual embryo achieves the

miracles of growth”. 9

The Sensitivity Fades & Disappears

As in the example of the caterpillar and the light, the specific sensitivity is of a particular duration.

Each Sensitive Period has its own psychic timer, counting down irrevocably. While it is present, its

chosen objects are as essential to the child’s psychic existence as food and air are to his physical

existence. But when this sensitivity fades – as it will, according to its own inner timetable – these

objects and experiences cease to be motives of activity; and they leave the child uninterested and

indifferent. It is very important to remember that adults can do nothing to change these cycles of

interest and dis-interest.

Ideally, a particular, vital sensitivity fades when the particular characteristic which was its goal has

been sufficiently formed. This then initiates another period of hidden, inner work, drawing the

child’s unconscious attention to other objects, to other motives of activity for self-construction.

If, however, there is insufficient nourishment in the outer environment – if proper objects or

circumstances are not available – then the sensitivity fades with its work undone. Similarly, if this

work is thwarted or obstructed, it might shut down prematurely, with its creative purpose

unfulfilled or stunted. In both circumstances, resulting defects or deformations will remain,

indelible, for the rest of this individual’s life. In the case of the Sensitive Periods, such a situation is

irremediable: Montessori states categorically: “If the baby has not been able to work in

accordance with the guidance of its sensitive period, it has lost its chance of a natural conquest

and has lost it forever. 10

8

The Secret Of Childhood, p. 37

9

The Secret Of Childhood, pp. 44; 38

10

The Secret Of Childhood, p. 39. Montessori elaborates (p. 40) that, as long as “… the conditions of the outer

environment correspond sufficiently to the child’s inner needs”, this psychic activity occurs “quietly and imperceptibly”.

Yet these “marvelous activities” leave “indelible traces, by which the man will be the greater, and which give him the higher

characteristics that will accompany him all his life.”

©Ginni Sackett – Montessori Institute Northwest 6

No portion may be reproduced without express written permission from the author Course 38

Sensitive Periods

Observable Characteristics of Sensitive Periods

From our list of the four Sensitive Periods in Human development, we can see that they guide four very

different aspects of essential Self-Construction. There are, however, certain observable characteristics

which all of the Sensitive Periods exhibit once a Motive of Activity has been selected. These observable

characteristics of a Sensitive Period at work are:

A Well-Defined Activity

There will be, first of all, a well-defined activity. This is the activity performed through the selected

objects or experiences in the environment (the Motives of Activity). Such well-defined activities can

often be very subtle: for example, under the guidance of the Sensitive Period for Language, a 4

month old child will actively watch the mouth of a human who is speaking. Or, the well-defined

activity can be very obvious – such as a child of 18 months, under the guidance of the Sensitive

Period for Movement, climbing a set of stairs encountered during a walk. In both instances, this

well-defined activity occurs only during a specific developmental moment. The speaker’s mouth

was not such a focus of interest earlier in the child’s life, nor will it be later. Similarly, earlier in the

child’s conquest of locomotion, he will pass by the stairs, as if not noticing them at all; while at a

later stage of gross motor control, they will cease to be of such intense interest, important only as

the means to enter or leave someplace else. For the prime developmental moment, however, it is

seemingly impossible to pass a staircase by – as anyone who has taken an urban walk with this age

child can attest.

An Irresistible Urge with Passionate Interest

We have already hinted at the second characteristic of a Sensitive Period: there is an unconscious,

irresistible urge toward this particular well-defined activity. While engaged in this activity, there is

complete indifference towards other objects or activities which are equally available in the

environment – as is obvious to anyone who has tried to distract a child away from such an activity;

and if the child is momentarily distracted, he returns to the activity as soon as possible – like iron

filings to a magnet.

The child’s engagement in this activity can only be described as one of passionate interest.

Montessori writes:

“The child makes a number of acquisitions during the sensitive periods, which place him in

relation to the outer world in an exceptionally intense manner. Then all is easy; all is eagerness

and life, every effort is an increase of power. … When some of these psychic passions die away,

other flames are kindled and so infancy passes from conquest to conquest, in a continuous vital

vibrancy, which we have called its joy and simplicity. It is through this lovely flame that burns

without consuming that the work of creating the mental world of man takes place. 11

Repetition of the Activity

11

The Secret of Childhood, pp. 36-37

©Ginni Sackett – Montessori Institute Northwest 7

No portion may be reproduced without express written permission from the author Course 38

Sensitive Periods

A fourth observable characteristic is repetition of this activity. This repetition can be observed in the

moment – as successive repetitions in one setting; or, as repetitions with the same or similar

objects over a span of days, or possibly weeks.

Closure: A Restful & Tranquil State at the Finish

When the child is able to live in harmony with this inner guidance – this “joy and simplicity” – we

can observe a characteristic manner as the cycle of this well-defined activity is completed: a state of

calm, of restful tranquility, of serenity, and of joy.

Although often difficult to discern, the aware and informed adult can observe, respect, and facilitate the

child’s work when he is acting according to the unconscious guidance of a Sensitive Period. This knowledge

and awareness forms the basis for education which is intended as a help to life.

The Role of Sensitive Periods in Self-Construction

Now, let’s look more closely at how the Sensitive Periods fit into our big picture of growth and

development. We have several layers of motivation at work – Human Tendencies throughout life; and here

in the First Plane of Development, The Absorbent Mind and Sensitive Periods. We already know a lot about

the Absorbent Mind – its extraordinary work as both a motivating power and as a creative power, guiding in

its two phases the formation of the psychic being. What is the relation, however, among these three – The

Human Tendencies, The Absorbent Mind, and The Sensitive Periods?

First, we can look at our list of Human Tendencies. Some Human Tendencies are profoundly reflected in the

characteristic activity of Sensitive Periods: in particular, concentration-repetition-self perfection with

increasing exactness and precision can be immediately recognized when a child is irresistibly engaged with

a motive of activity.

For other Human Tendencies, however, we can see that although these are operative at birth, the child’s

capacity to realize or actualize these Human Tendencies is limited by his inert, dependent, unformed state –

his existence as a psychic-spiritual embryo still in the process of primary formation. We could say that the

full realization of the Human Tendencies must await the creation, development, and refinement of the

psychic organs necessary to carry them out. To extend Montessori’s analogy of the physical body seeking

nourishment from its environment: the proper nourishment of an omnivorous human must await the

development of the organs of digestion; in the same way, the Human Tendencies await fully functioning

psychic organs – here are some examples:

• The Sensitive Period for Order constructs internal mental order with which to organize the

information gained through experience (Human Tendency for Order)

• The Sensitive Period for Movement constructs capacities for coordinated movement necessary to

fully explore the environment (Human Tendency for Exploration)

©Ginni Sackett – Montessori Institute Northwest 8

No portion may be reproduced without express written permission from the author Course 38

Sensitive Periods

• The Sensitive Period for Development and Refinement of Sensory Impressions constructs refined

and reliable sensory impressions which are the foundation for accurate, detailed and reliable

abstractions (Human Tendency for Abstraction and Imagination)

• The Sensitive Period for Language constructs full spoken language to channel human

communication. (Human Tendency for Communication)

As we have seen, none of these capacities exist at birth: they are created and integrated as part of the

formation of a human being during the First Plane of Development. This is what it means that the

constructions guided by the Sensitive Periods are essential and fundamental aspects of the psychic being;

and that future development is contingent upon these prior formations.

This is a good time to re-visit Montessori’s charts depicting the Four Planes – particularly the first chart,

which illustrates the Planes in terms of “The Constructive Rhythm of Life”. We see on this chart a highly

stylized and geometric representation, with its lines alternately diverging and merging with the line of life.

These lines create enclosed triangles – depicting an orderly rhythm as each stage of life opens to new

experiences and acquisitions, then closes, preparing for a new stage to follow; this, in contrast to the Bulb

chart and its graphic depiction of the dynamic energy of growth and development. Specifically, this first

chart shows (in Camillo Grazzini’s description), “… the vital role of the sensitive periods or sensitivities

which, as they change their nature from one phase to another, determine the characteristics of each and

every phase. The sensitivities pertinent to a particular phase appear, increase, reach a maximum, and

then decline; new sensitivities appear, reach a maximum and decline to give way to yet other, new

sensitivities; and so on. It is these sensitivities, then, that guide development and determine its rhythm”.

12

In her description of the Absorbent Mind, Montessori described the nebulae as specialized and

differentiated aspects of the Horme, the Motivating Power of the Absorbent Mind; the Nebulae direct the

child’s psychic attention to specific images available in the environment which are necessary for self-

construction and adaptation, for growth and development. Perhaps we can see the Sensitive Periods, in

turn, as specialized aspects of the Creative Power of the Absorbent Mind: for certain essential formations

during the First Plane of Development, the constructive activity of the Absorbent Mind is specifically guided

and organized by The Sensitive Periods. During the first sub-plane in particular, The Sensitive Periods,

organize the indiscriminate totality images stored in the Absorbent Mind. Through their cycles of activity, in

strict sequence, key components of the intelligence – of psychic life – are constructed: mental organs

created separately, just as the organs of the body were constructed separately in utero. 13 These key

psychic organs are created through the powers of the Sensitive Periods for Order; Movement; Development

& Refinement of Sensory Perceptions; and Language.

12

Camillo Grazzini. “The Four Planes of Development”, The Child, The Family, The Future. Proceedings, AMI International Study

Conference, July 1994. AMI/USA: 1995, p. 118.

13

Maria Montessori. The Absorbent Mind, p. 165: “In this psycho-embryonic period various powers develop separately and

independently of one another; for example, language, arm movements and leg movements. Certain sensory powers also take

shape. And this is what reminds us of the prenatal period, when the physical organs are developing each on its own account,

regardless of the others. For, in this psycho-embryonic period we see the mental powers of control coming into existence

separately.”

©Ginni Sackett – Montessori Institute Northwest 9

No portion may be reproduced without express written permission from the author Course 38

Sensitive Periods

As these separate organs are created during the first three years of life, the structure of the child’s mental

life is itself transformed. This is manifested in the child’s activity in two ways:

• As successive conquests of independence

• As the emergent consciousness which characterizes the developmental work of the second

sub-plane, when these separate creations are developed and integrated into the unity of the

emergent personality

Within their allotted time spans, the Sensitive Periods both contribute to, and also partake of, the two-part

process which we describe as the two phases of the Absorbent Mind: unconscious creation followed by

conscious development. All of this self-construction, and particularly the creation of the psychic organs by

the Sensitive Periods, is essential to the functioning of an integrated personality, able to act for the rest of

his life in accordance with the motivations of the Human Tendencies.

Here is Montessori’s summary for the First Plane of Development:

… we may say that man is born with a vital force (horme) already present in the general structure

of the absorbent mind, with its specializations and differentiations which we have described

under the heading of “nebulae”. This structure alters during infancy under the direction of what

we have called (following De Vries) the sensitive periods. Growth and psychic development are

therefore guided by: the absorbent mind, the nebulae and the sensitive periods, with their

respective mechanisms. It is these that are hereditary and characteristic of the human species. 14

14

The Absorbent Mind, pp. 95-96

©Ginni Sackett – Montessori Institute Northwest 10

No portion may be reproduced without express written permission from the author Course 38

Sensitive Periods

Bibliography

Montessori Sources

Maria Montessori. The Absorbent Mind. (1949) Claude A. Claremont, trans. New York: Dell Publishing, 1967.

…… The Child, Society And The World: Unpublished Speeches And Writings. Oxford: Clio Press, 1989.

…… Childhood Education (The Formation of Man). (1949) A.M. Joosten, trans. (1955) NY: Meridian, 1975.

…… Education For A New World. (1946) Madras, India: Kalekshetra Publications: 1963.

…… The Secret Of Childhood. (1936?) Barbara Barclay Carter, trans. Hyderabad: Orient Longman LTD, 1978.

nd

Montessori, Mario M. “The Human Tendencies and Montessori Education”, 2 Edition, AMI (1956)

The Child, The Family, The Future. Proceedings, International Study Conference, July 1994. AMI/USA: 1995.

Camillo Grazzini’s article ‘The Four Planes of Development’ (discussing Montessori’s charts for the Four Planes of

Development) can also be found in several different issues of the NAMTA Journal – including Winter 2004.

Corbett, Constance. “Sensitive Periods”, AMI Communications #2-3 1995, pp. 38-46.

Montanaro, Silvana Q. M.D. Understanding The Human Being: The Importance of the First Three Years of Life. (1987)

Mountain View CA: Nienhuis Montessori USA, 1991.

Stephenson, Margaret E. “The Secret of Childhood and To Educate the Human Potential”, AMI Communications #1

1996, pp. 12-24.

Non-Montessori Sources:

Bickerton, Derek. Language and Species. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

…… Language and Human Behavior. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1995.

Kauffman, Stuart. At Home In The Universe: The Search For The Laws of Self-Organization And Complexity.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Kotulak, Ronald. Inside The Brain: Revolutionary Discoveries Of How The Mind Works. Kansas City: Andrews

& McMeel, 1996.

rd

Montagu, Ashley. Touching: The Human Significance Of The Skin. 3 Edition. New York: Harper & Row, 1986.

Restak, Richard M.D. Brainscapes: An Introduction to What Neuroscience Has Learned About the Structure,

Function, and Abilities of the Brain. New York: Hyperion, 1995,

Trevarthen, Colwyn. “Mind In Infancy”, in The Oxford Companion To The Mind, Richard L. Gregory, ed.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987, pp. 362-368.

Wiener, Norbert. The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950.

©Ginni Sackett – Montessori Institute Northwest 11

No portion may be reproduced without express written permission from the author Course 38

You might also like

- Advanced Legal Writing, Third Edition Theories and Strategies in Persuasive Writing, Third Edition (Michael R. Smith)Document615 pagesAdvanced Legal Writing, Third Edition Theories and Strategies in Persuasive Writing, Third Edition (Michael R. Smith)Sovanrangsey Kong100% (2)

- The Role of The Assistant in A Montessori Classroom: Sandra Girl ToDocument5 pagesThe Role of The Assistant in A Montessori Classroom: Sandra Girl ToKesia AvilesNo ratings yet

- Montessori Adolescent Methodology - ENDocument55 pagesMontessori Adolescent Methodology - ENMarcel CapraruNo ratings yet

- Desarrollo SocialDocument16 pagesDesarrollo SocialNalleli CruzNo ratings yet

- Independence:: A Montessori JourneyDocument6 pagesIndependence:: A Montessori JourneyAndrea Lovato100% (2)

- How To Raise An Amazing Child The Montessori Way, 2nd Edition: A Parents' Guide To Building Creativity, Confidence, and Independence - Tim SeldinDocument4 pagesHow To Raise An Amazing Child The Montessori Way, 2nd Edition: A Parents' Guide To Building Creativity, Confidence, and Independence - Tim SeldinzusohunuNo ratings yet

- Maria MontessoriDocument5 pagesMaria Montessoriniwdle1No ratings yet

- Essay - PleDocument18 pagesEssay - PleKshirja SethiNo ratings yet

- Maria Montessori - Biography - Academic, Educator - Biography PDFDocument4 pagesMaria Montessori - Biography - Academic, Educator - Biography PDFkoldo10100% (2)

- Ssignment Odule: S B: M .S KDocument14 pagesSsignment Odule: S B: M .S Ksaadia khanNo ratings yet

- Human Needs and TendenciesDocument9 pagesHuman Needs and TendenciesHeidi Quiring0% (1)

- Define The Term Sensitive PeriodsDocument3 pagesDefine The Term Sensitive PeriodsBéla Soltész100% (4)

- In Casa de BambiniDocument2 pagesIn Casa de Bambiniparadise schoolNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Preliminary Activities C38Document2 pagesIntroduction To Preliminary Activities C38Marinella PerezNo ratings yet

- Life and Works of DrMAriaDocument19 pagesLife and Works of DrMAriaSa100% (1)

- Human TendenciesDocument9 pagesHuman TendenciesBinduNo ratings yet

- The NAMTA Journal - Vol. 39, No. 2 - Spring 2014: Ginni SackettDocument20 pagesThe NAMTA Journal - Vol. 39, No. 2 - Spring 2014: Ginni SackettSaeed Ahmed BhattiNo ratings yet

- Nebulae 0Document3 pagesNebulae 0delia atenaNo ratings yet

- Maria Montessori BioDocument3 pagesMaria Montessori Bioapi-395431821No ratings yet

- Intro To MathDocument22 pagesIntro To MathMonwei YungNo ratings yet

- Slogan (We Follow The Child)Document9 pagesSlogan (We Follow The Child)paradise schoolNo ratings yet

- Epilogue 0 - The Child and The EnvironmentDocument14 pagesEpilogue 0 - The Child and The EnvironmentkatyarafaelNo ratings yet

- 3period LessonokprintDocument3 pages3period LessonokprintFresia MonterrubioNo ratings yet

- History of MontessoriDocument19 pagesHistory of MontessoriRazi AbbasNo ratings yet

- Montessori PrinciplesDocument6 pagesMontessori Principlesapi-269680928No ratings yet

- Developmental Delays and Movement in Relation To Instinct Harriet Jane A AlejandroDocument36 pagesDevelopmental Delays and Movement in Relation To Instinct Harriet Jane A AlejandroNeil Christian Tunac CoralesNo ratings yet

- Module 1 AssignmentDocument18 pagesModule 1 AssignmentQurat-ul-ain abroNo ratings yet

- The First Plane of DVP - Birth To Age 6 - Montessori Philosophy PDFDocument3 pagesThe First Plane of DVP - Birth To Age 6 - Montessori Philosophy PDFMahmoud BelabbassiNo ratings yet

- Citizen of The WorldDocument3 pagesCitizen of The WorldOrieri brianNo ratings yet

- Amiusa Maria Montessori Biography2 PDFDocument2 pagesAmiusa Maria Montessori Biography2 PDFDunja Kojić ŠeguljevNo ratings yet

- Why Children Bully - Himpsi SumutDocument62 pagesWhy Children Bully - Himpsi Sumutfajar zakiNo ratings yet

- Ami School Standards 7092Document2 pagesAmi School Standards 7092Dunja Kojić ŠeguljevNo ratings yet

- Course 37 Practical Life Presentation Outlines 5kb2Document32 pagesCourse 37 Practical Life Presentation Outlines 5kb2Kreativ MontessoriNo ratings yet

- AMI Montessori Observation Refresher 2019Document10 pagesAMI Montessori Observation Refresher 2019AleksandraNo ratings yet

- The Ten Secrets of MontessoriDocument4 pagesThe Ten Secrets of MontessoriJessa Resuello FerrerNo ratings yet

- Oral Language in The Montessori ClassroomDocument5 pagesOral Language in The Montessori ClassroomLarson ChinNo ratings yet

- Montessori Question and Ans SheetDocument13 pagesMontessori Question and Ans SheetJayantaBeheraNo ratings yet

- Observation 1987 London UpdatedDocument3 pagesObservation 1987 London UpdatedAleksandraNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3Document20 pagesLesson 3Kassandra KayNo ratings yet

- Module 5 Raeesa D-17230Document21 pagesModule 5 Raeesa D-17230Raeesa ShoaibNo ratings yet

- TreasureArticle2022 01-1Document9 pagesTreasureArticle2022 01-1Marizz DuduNo ratings yet

- The Absorbent MindDocument1 pageThe Absorbent MindUzma MazharNo ratings yet

- 5 GlasgowDocument24 pages5 Glasgowbentarigan77100% (1)

- Absorbent Mind and Sensitive Periods PDFDocument2 pagesAbsorbent Mind and Sensitive Periods PDFЕкатеринаNo ratings yet

- Montessori Method - Final Assignment 1 - 22 MAY 2022Document11 pagesMontessori Method - Final Assignment 1 - 22 MAY 2022Jennifer BotheloNo ratings yet

- Human Interdependencies HelenaDocument15 pagesHuman Interdependencies HelenahelenareidNo ratings yet

- Montassori Module 2Document23 pagesMontassori Module 2Ahmed0% (1)

- Example and Definition: Sensitive Periods Is A Term Developed by The Dutch Geneticist Hugo de Vries and Later UsedDocument10 pagesExample and Definition: Sensitive Periods Is A Term Developed by The Dutch Geneticist Hugo de Vries and Later UsedMehakBatla100% (1)

- IQRA NAYYAB - D18333 - Module 2 - Assisgnment 2Document21 pagesIQRA NAYYAB - D18333 - Module 2 - Assisgnment 2iqra Ayaz khanNo ratings yet

- Six "Sensitive Periods": by Maria MontessoriDocument2 pagesSix "Sensitive Periods": by Maria Montessoridelia atenaNo ratings yet

- PMC Module Three Assignment Misbah.....Document19 pagesPMC Module Three Assignment Misbah.....Misbah AmjadNo ratings yet

- Arts Integration in Montessori MathematicsDocument21 pagesArts Integration in Montessori MathematicsLorena MaglonzoNo ratings yet

- Montessori Practical LifeDocument3 pagesMontessori Practical LifeSiti ShalihaNo ratings yet

- Q2 M 1requirements To Start House of ChildremDocument3 pagesQ2 M 1requirements To Start House of ChildremNighat Nawaz100% (4)

- ED411077Document92 pagesED411077katyarafaelNo ratings yet

- 6 Sensitive Periods in Montessori CurriculumDocument2 pages6 Sensitive Periods in Montessori Curriculumaina adrianaNo ratings yet

- MontessoriDocument14 pagesMontessori4gen_3No ratings yet

- Culture 1 (Geography and History)Document10 pagesCulture 1 (Geography and History)Sadaf KhanNo ratings yet

- Names: Gulshan Shehzadi Roll# D17090 Topic: Exercise of Practical Life (EPL)Document18 pagesNames: Gulshan Shehzadi Roll# D17090 Topic: Exercise of Practical Life (EPL)Gulshan ShehzadiNo ratings yet

- SensorialDocument10 pagesSensorialMonwei YungNo ratings yet

- Images of Animals For School (AutoRecovered) 1Document24 pagesImages of Animals For School (AutoRecovered) 1Gavi NnamdiNo ratings yet

- I Am A Member of The Boa FamilyDocument2 pagesI Am A Member of The Boa FamilyGavi NnamdiNo ratings yet

- Review of The Nigerian Economy in 2020 and Key Priorities For 2021 and BeyondDocument27 pagesReview of The Nigerian Economy in 2020 and Key Priorities For 2021 and BeyondGavi NnamdiNo ratings yet

- Social Development C38Document15 pagesSocial Development C38Gavi NnamdiNo ratings yet

- What Makes A New Business Start-Up Successful?: ArticleDocument19 pagesWhat Makes A New Business Start-Up Successful?: ArticleGavi NnamdiNo ratings yet

- Ethics MIDTERMSDocument3 pagesEthics MIDTERMSClaire Jacynth FloroNo ratings yet

- Calasanz-My BodyDocument6 pagesCalasanz-My BodyALDOUS GABRIEL MIGUELNo ratings yet

- 3 PR2 ManuscriptDocument71 pages3 PR2 Manuscriptkyla villarealNo ratings yet

- 5 Generation Warfare and Social Media: ST THDocument2 pages5 Generation Warfare and Social Media: ST THSheikh AmmaraNo ratings yet

- Stephen R. Anderson - The Language OrganDocument285 pagesStephen R. Anderson - The Language Organioana_mariaro8144100% (2)

- Artificial Intelligence Unit 1 NotesDocument34 pagesArtificial Intelligence Unit 1 NotesSa InamdarNo ratings yet

- Prieto Ramos FernandoDocument10 pagesPrieto Ramos FernandoHojaAmarillaNo ratings yet

- A Nonviolent Communication (NVC) Cheat Sheet: Spare Time PhilosophyDocument1 pageA Nonviolent Communication (NVC) Cheat Sheet: Spare Time PhilosophyMiguel Barata GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Trends Networks and Critical Thinking in The 21st CenturyDocument13 pagesModule 2 Trends Networks and Critical Thinking in The 21st CenturyGhol Ocray BonaobraNo ratings yet

- Ed 105 Module 7 10 Answer The Activities HereDocument24 pagesEd 105 Module 7 10 Answer The Activities HereJodelyn Quirao AlmarioNo ratings yet

- Oral Presentation Rubric IngvDocument1 pageOral Presentation Rubric Ingvjose angelNo ratings yet

- Bleach CYOADocument3 pagesBleach CYOAJoão Pedro FariasNo ratings yet

- Ethical Requirements: Prepared By: Group 7Document26 pagesEthical Requirements: Prepared By: Group 7Maica A.No ratings yet

- Purposive Communication Reviewer .1Document9 pagesPurposive Communication Reviewer .1Ash JuamanNo ratings yet

- Framework of The StudyDocument21 pagesFramework of The StudyJuanito II BalingsatNo ratings yet

- UTS Finals CoverageDocument11 pagesUTS Finals CoverageAjiezhel NatividadNo ratings yet

- CMM-4050 Theories of Perfsuasion: Spring 2019Document11 pagesCMM-4050 Theories of Perfsuasion: Spring 2019ElsiechNo ratings yet

- Lesson 10 - Drawing Out Patterns and Themes From DataDocument31 pagesLesson 10 - Drawing Out Patterns and Themes From DataJames Andrei CaguiclaNo ratings yet

- Management Information Systems Course ObjectivesDocument3 pagesManagement Information Systems Course ObjectivesAakash AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Week 4 Purposive CommunicationDocument16 pagesWeek 4 Purposive CommunicationJerusha Shane Dueñas SadsadNo ratings yet

- Ai1 2Document41 pagesAi1 2Head CSEAECCNo ratings yet

- The Image of The City Book ReviewDocument3 pagesThe Image of The City Book ReviewSharique ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Annotation. in This Article An Important Assumption of Discourse Analysis IsDocument5 pagesAnnotation. in This Article An Important Assumption of Discourse Analysis IsNguyễn Hoàng Minh AnhNo ratings yet

- Grade 12 LM PR2 1 Module3Document45 pagesGrade 12 LM PR2 1 Module3Romnick CosteloNo ratings yet

- Prof Ed 6Document2 pagesProf Ed 6KAYE ESCOBARNo ratings yet

- IntroPhiloSHS Q4 Mod1 Version5 BaoDocument14 pagesIntroPhiloSHS Q4 Mod1 Version5 BaoClark崎.No ratings yet

- Minds: Margaret DonaldsonDocument180 pagesMinds: Margaret DonaldsonAnnie AloyanNo ratings yet

- Quiz CommunicationDocument9 pagesQuiz CommunicationAlishba ZubairNo ratings yet

- An Application of Lefebvere's SpaceDocument13 pagesAn Application of Lefebvere's Spacepinkish zahraNo ratings yet