Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fairytale

Fairytale

Uploaded by

Daniel WolterOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fairytale

Fairytale

Uploaded by

Daniel WolterCopyright:

Available Formats

The Expectant Reader in Theory and Practice

Author(s): Lois Josephs Fowler and Kathleen McCormick

Source: The English Journal , Oct., 1986, Vol. 75, No. 6 (Oct., 1986), pp. 45-47

Published by: National Council of Teachers of English

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/819009

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

National Council of Teachers of English is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to The English Journal

This content downloaded from

132.72.138.1 on Sun, 04 Sep 2022 11:14:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Expectant Reader

in Theory

and Practice

Lois Josephs Fowler and Kathleen McCormick

genres. Students' expectations, therefore, allow for

In the past decade or so, reader-response criticism

has emerged as the kind of theory potentially certain

most interpretations but inhibit others that sur-

useful for changing both pedagogy and literary face only when their expectations change.

issues addressed in the classroom. Some pedagog- The unit begins with a fairy tale. Not only does

ical ideas have been offered with this wealth of the genre frequently contain metamorphoses but

theory, but they have been accompanied byitfew is also one about which students have clearly-

concrete and specific suggestions about defined actual expectations. We begin with Italo Calvi-

classroom practice. The lack may result from no'san"The Canary Prince" because in this story a

overriding emphasis on the ideal reader rather prince turns into a canary-a metamorphosis that

than the actual one. As teachers we need some parallels Kafka's story. While few students have

working strategies, so in this paper, we suggest previously

one read it, most are still almost immedi-

issue that provokes students into more self-con- ately able to recognize its familiar fairy

scious awareness of what they do as readers conventions.

and

helps them to develop insights about how individ- We ask students if they have difficulty accepting

ual expectations of texts, rather than just the texts

the unrealistic events of the story, such as the met-

themselves, color their perceptions of literature.

amorphosis, the witches, or the magic potions. No

Since use of the inductive or Socratic method one does, but we want them to determine explicitly

of questioning may lead students too forcefully whyin they do not. While responses vary, they are

a predetermined direction, we suggest instead always a informed by students' acceptance of the

sequence of reading assignments and strategies. conventions of the fairy tale: most of them rec-

As an example, we show here how students can that they were introduced to fairy tales at

ognize

arrive at powerful, individual readings of Kafka'san early age with the distinction between fantasy

"Metamorphosis" and, more important, increasing and reality blurred. Consequently, they accept the

awareness that their assumptions and expectations unrealistic "once upon a time" and the "happily

about a text influence their reading experience everasafter" construction of the fairy tale; they

much as the text itself. accept the stereotyped activities of the handsome

Each of the following texts-fairy tale, fable, prince, the wicked stepmother, the mistreated

parable, realistic story--describes a metamorpho-princess, the naive king, and the cagey witch.

sis of some kind. What we wish to help students We also ask students what questions they tend

recognize is that their responses to these meta- not to ask of a fairy tale. We discover that they

morphoses will differ, not because of intrinsic tex-

initially avoid any issues that confront realism-

tual differences but because their assumptions the motives of the stepmother, the compatibility of

the prince and princess, the existence of the

about genre classifications cause them to have dif-

ferent interpretative expectations about how meta-

witches, the means by which the prince turns into

morphoses can function in each of these sub-a canary and the princess disguises herself as a

October 1986 45

This content downloaded from

132.72.138.1 on Sun, 04 Sep 2022 11:14:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Students then read Gabriel Marquez's "The

Very Old Man With Enormous Wings," a quasi-

biblical parable about an old angel, sick and hurt,

with damaged wings, who lands in the yard of a

poor family and becomes the center of interest for

people of the town. Because students are as famil-

iar with the traditional parable form as they were

with the fairy tale and the fable, they do not ques-

tion the supernatural or unrealistic events of the

story. What they do question is the ironic tone in

which the parable is presented. Why does the

angel look so old and sad? What happened to the

angel's power? Why is the angel so ugly? Why does

the angel land in such a strange place? What these

questions reveal is an acceptance of the magical

quality of angels but rigid expectations about the

appropriate demeanor of angels. Even though

angels, like canary princes and talking animals,

belong to the realm of the imaginary, or at least

man. These questions are not in themselves the unknown, they have been so conventionalized

invalid; they are simply seen by students as inap- that students expect them to appear and behave

propriate to ask of a fairy tale because students in prescribed ways.

assume that the events of a fairy tale should be Despite students' acceptance of the strange or

accepted, not analyzed. We will see later, however, magical in all of the literary forms they have read

that these are exactly the kinds of questions stu- thus far, they are still puzzled by Gregor's trans-

dents ask of Kafka's "Metamorphosis." By making formation into a bug in Kafka's "metamorphosis."

students aware of the questions they would not ask This demonstrates effectively that students' expec-

of a fairy tale, we alert them to simple ways in tations, as well as the events of a narrative, deter-

which their responses are determined by their mine how they react, in this case with initial

expectations about texts rather than by texts confusion and disbelief. Because its tone and set-

themselves. ting is realistic, students report that they are

Next, we turn to a fable, a genre about which unable to categorize Kafka's story as either a fairy

students' responses may be somewhat more ana- tale, a fable, or a parable, three forms of classifi-

lytical. They themselves report that they expect tocation that would allow them to naturalize Gre-

find a "message" of some kind in a fable. We use gor's metamorphosis in the way they naturalized

"The Fox and the Grapes" or "The Tortoise and that of the prince, the animals, and the angel.

the Hare" because they depict metamorphoses of Thus a metamorphosis becomes a subject for

a kind. Even if students do not understand alle- interpretation for the first time in this assignment

gory, these stories do not provoke questions sequence.

about This occurs not so much because of the

text of Kafka's story, but rather because students

how animals can act like people. Just as students

have expectations about the nature of metamor-

accepted the prince's transformation into a canary

phoses in literature. They assume that metamor-

in "The Canary Prince," so they accept the human

characteristics of the animals in these fables. But phoses can only occur in unrealistic and

students' discussions of these fables transcend fantastical writing.

Thus students ask questions of Gregor's meta-

those of the fairy tale because their expectations

morphosis

engage them on a moral level. In fact we get some that they did not ask of characters who

were

disagreement in response: some students resent a transformed in other stories. How can a per-

son really

didactic message in the literary form; others are change into a bug? Why does Gregor,

though

comfortable because they feel they "get the point." a bug, try to go on with his daily chores

as if nothing

Nonetheless, all students expect and therefore find has happened to him? Why does his

family

a moral in these fables, something they did not virtually ignore him? Because students

cannot

expect or find in the fairy tales they read. resolve such questions from their prior

46 English Journal

This content downloaded from

132.72.138.1 on Sun, 04 Sep 2022 11:14:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

expectations of literary conventions, they feel the same way that they analyzed Gregor as a loath-

need to search for new ways to explain or explain some, pitiable creature because he turned into an

away Gregor's metamorphosis. If they have been insect. In fact the prince does prove to be rather

trained in school that if a text does not make lit- simple-minded, being easily tricked and finally

eral sense, it may make sense metaphorically, needing

stu- to be rescued by the princess. But stu-

dents can, without prompting from the teacher, dents did not choose to develop such an analysis

draw on their knowledge of the literary convention of the Canary Prince, not because the text would

of symbolism, their knowledge of psychology,not andallow it, but because their expectations found

their personal experiences of rejection to analyze an easier way to accept the Prince's

Gregor's metamorphosis symbolically. They arrive metamorphosis.

at the operative question: Why might a human To organize a unit around theoretical issues, a

being perceive himself to be a bug? Less sophisti- reader-centered approach to teaching literature

cated students may need more direct guidance. can encourage students to analyze the influences

Their experiences with metamorphoses in theand lit- assumptions underlying their apprehension

erary genres they do understand, however, make of texts rather than simply to state how they "feel"

it easier for them to recognize that they must about texts. It may take a few weeks to convince

expand their expectations if they are to naturalize students that they have assumptions, that these

Gregor's metamorphosis: most of them beginassumptionsto are acquired rather than innate, and

analyze this metamorphosis in a new way, as a that psy- they are really of interest in the classroom.

chological rather than a physical transformation. Our students gain confidence in their own ability

Students did not even think of analyzingto the

analyze the individual expectations that under-

Canary Prince's metamorphosis as psychological lie their experiences of texts. The classroom,

because its magical nature conformed with their therefore, becomes a place where students develop

expectations about fairy tales. Once students their own ideas with less obvious prompting by the

assume that Gregor's metamorphosis is psycholog- teacher-though not with less planning.

ical, they can then confront a whole host of pos- How clever was Charles Dickens with his title,

sibilities in their individual responses to the story:

Great Expectations-a title having no place, no per-

Gregor's anger with his family; Gregor's feelings son, no concrete subject. How do we read the book

of insecurity; Gregor's feelings of exploitation; after reading the title? How do we feel about the

Gregor's inability to confront his own misery.forceIt is of expectations as they influence perceptions

important to recognize that students' knowledge of what happens, of how characters think and act?

of psychology and symbolism and their personal Pip perceives that Miss Havisham is his patron

experiences of rejection were in their repertoiresand acts accordingly; she perceives his misconcep-

when reading all these stories, but they were tions

acti- and feeds on them; Jaggers, the convict

vated only by Kafka's story because their assump- turned patron and father, perceives that Pip will

tions about fairy tales, fables, and parables

be made happy if he is educated to be a gentle-

preclude such forms of analysis. man; and so on. Only when Pip understands the

Just as important as students' developmentcomplexities

of of his expectations can he begin to

confront

symbolic interpretations is their understanding of himself and the text that is his life. Sim-

how they arrive at such interpretations. Having

ilarly, only when our students are able to under-

read a number of stories about which they did not the expectations that guide their reading

stand

feel the need to develop a symbolic interpretation,

and interpretative experiences can they become

students now gain a greater insight into the confident, critical, and self-conscious readers of

literature.

assumptions and expectations that direct their

determination of when and why they feel com-

pelled to develop symbolic interpretations. It

would have been possible, for example, forLois

stu-Josephs Fowler and Kathleen

dents to have analyzed the Canary Prince as a McCormick

frail teach at Carnegie-Mellon

man because he turned into a little bird in the University.

October 1986 47

This content downloaded from

132.72.138.1 on Sun, 04 Sep 2022 11:14:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Janson, Stone Clark 2009Document10 pagesJanson, Stone Clark 2009Daniel WolterNo ratings yet

- Dungeons & Dragons - Monster Manual (001-126)Document126 pagesDungeons & Dragons - Monster Manual (001-126)Marcelo Villeda71% (7)

- Encyclopedia Mythologica: Gods and Heroes Pop-Up Teachers' GuideDocument2 pagesEncyclopedia Mythologica: Gods and Heroes Pop-Up Teachers' GuideCandlewick PressNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5: Types of Children's Literature: Candice Livingston and Molly BrownDocument31 pagesChapter 5: Types of Children's Literature: Candice Livingston and Molly Brownun_arandanosNo ratings yet

- Lazy DM Workbook Fill-In Pages PDFDocument5 pagesLazy DM Workbook Fill-In Pages PDFlittlepuppy100% (1)

- Catherine Lim2Document13 pagesCatherine Lim2lovelydove020% (1)

- English 4 Lesson Plan Week 10-11Document16 pagesEnglish 4 Lesson Plan Week 10-11Josef SamaranayakeNo ratings yet

- Magical TheoryDocument41 pagesMagical TheoryBrianna Gittos100% (2)

- Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesLesson PlanDERYL SAZONNo ratings yet

- Lit Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesLit Lesson PlanDeryl SazonNo ratings yet

- Frog Princess ExplanationofchoiceDocument8 pagesFrog Princess ExplanationofchoiceDewi Umbar PakartiNo ratings yet

- Pip Project ArticleDocument1 pagePip Project Articleapi-641185793No ratings yet

- 1gates P S Steffel S B Molson F J Fantasy Literature For ChilDocument177 pages1gates P S Steffel S B Molson F J Fantasy Literature For ChilВикторияNo ratings yet

- Thesis Water For ElephantsDocument6 pagesThesis Water For ElephantsVicki Cristol100% (2)

- The Fairy Tale An Introduction To Literature and The Creative ProcessDocument16 pagesThe Fairy Tale An Introduction To Literature and The Creative Processblackpetal1No ratings yet

- Narrative BookDocument13 pagesNarrative BookFifi AfifahNo ratings yet

- Teaching Fairy Tales in Optional ClassesDocument15 pagesTeaching Fairy Tales in Optional ClassesAndreea BudeanuNo ratings yet

- Children's LiteratureDocument2 pagesChildren's LiteraturemamjobelleNo ratings yet

- Temel Halde Masallar Ve WaldorfDocument3 pagesTemel Halde Masallar Ve WaldorfinfoNo ratings yet

- Child and Adult MidtermDocument70 pagesChild and Adult MidtermcanoruthmarquezNo ratings yet

- A Study of Fairy Tales by Kready, Laura F.Document209 pagesA Study of Fairy Tales by Kready, Laura F.Gutenberg.org100% (2)

- Monarch Metaphors LCMSDocument2 pagesMonarch Metaphors LCMSMadel PorrasNo ratings yet

- Reading Journal (1)Document54 pagesReading Journal (1)Phub LhamNo ratings yet

- Cleland Unit Calendar With Terminal ObjectivesDocument2 pagesCleland Unit Calendar With Terminal ObjectivesTaylor ClelandNo ratings yet

- Cleland Unit Calendar With Terminal ObjectivesDocument2 pagesCleland Unit Calendar With Terminal ObjectivesTaylor ClelandNo ratings yet

- Anchor Text Guidance: Grade 8, Module 1: Folklore of Latin AmericaDocument6 pagesAnchor Text Guidance: Grade 8, Module 1: Folklore of Latin AmericaHannahNo ratings yet

- 166 ArticleText 283 1 10 20181122Document16 pages166 ArticleText 283 1 10 20181122Michelle LinaNo ratings yet

- Activity 1 - Valuing Literature For ChildrenDocument4 pagesActivity 1 - Valuing Literature For Childrenwill cabreraNo ratings yet

- EEd 221 CHILDRENS LITERATURE - MIDTERM REVIEWERDocument4 pagesEEd 221 CHILDRENS LITERATURE - MIDTERM REVIEWER22-58387No ratings yet

- Unit Plan: King Arthur and Adaptations GATE English 9/western CivDocument3 pagesUnit Plan: King Arthur and Adaptations GATE English 9/western CivTaylor ClelandNo ratings yet

- Myth BookDocument60 pagesMyth BookAlexa May AlbiaNo ratings yet

- Book Wonders of NatureDocument91 pagesBook Wonders of Natureapi-308438389100% (2)

- wp3 Turn-In DraftDocument5 pageswp3 Turn-In Draftapi-302358988No ratings yet

- Coincidence in The Novel - A Necessary TechniqueDocument13 pagesCoincidence in The Novel - A Necessary TechniqueMorain CanausNo ratings yet

- The Book of Fables and FairytalesDocument33 pagesThe Book of Fables and FairytalesblackriptoniteNo ratings yet

- Gifted 3Document12 pagesGifted 3api-413748610No ratings yet

- Book Sea TurnDocument7 pagesBook Sea TurnqrboyaNo ratings yet

- IbodullayevaDocument5 pagesIbodullayevaAshu TyagiNo ratings yet

- Fairytale Dissertation IdeasDocument5 pagesFairytale Dissertation IdeasPaperHelperUK100% (1)

- Benefits of Children's Literature Cognitive DimensionDocument4 pagesBenefits of Children's Literature Cognitive DimensionGlaiza OrpianoNo ratings yet

- Three Genre PlanDocument10 pagesThree Genre Planapi-443207039No ratings yet

- The Story of The Monkey and The Turtle - An Illustrated RetelliDocument27 pagesThe Story of The Monkey and The Turtle - An Illustrated RetelliLeonard Lirio PanganibanNo ratings yet

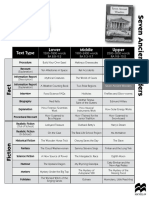

- Springboard 4 Teacher Pack Seven Ancient WondersDocument16 pagesSpringboard 4 Teacher Pack Seven Ancient WondersEmre HpNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For A Fable For TomorrowDocument8 pagesThesis Statement For A Fable For Tomorrowangelawilliamssavannah100% (1)

- Exploring the Fantasy Realm: Magic in Stories for Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandExploring the Fantasy Realm: Magic in Stories for Children and Young AdultsNo ratings yet

- Amber & Clay Teachers' GuideDocument3 pagesAmber & Clay Teachers' GuideCandlewick PressNo ratings yet

- Rosalind's Siblings: Fiction and Poetry Celebrating Scientists of Marginalized GendersFrom EverandRosalind's Siblings: Fiction and Poetry Celebrating Scientists of Marginalized GendersNo ratings yet

- A Rose For Emily Literary Analysis EssayDocument4 pagesA Rose For Emily Literary Analysis Essayafhbctdfx100% (2)

- Thesis FantasyDocument8 pagesThesis Fantasypatriciajohnsonwashington100% (1)

- The Power of Belief - Innocents and Innocence in Childrens Fantas PDFDocument119 pagesThe Power of Belief - Innocents and Innocence in Childrens Fantas PDFnurhidayatiNo ratings yet

- Modern Fantasy Literary AnalysisDocument6 pagesModern Fantasy Literary Analysisapi-264901966No ratings yet

- Fairy Tale Dissertation TopicsDocument5 pagesFairy Tale Dissertation TopicsWriteMyCollegePaperBillings100% (2)

- 5 Theme in Children LiteratureDocument17 pages5 Theme in Children LiteratureRizki Diliarti ArmayaNo ratings yet

- Task 4 Their ChoiceDocument4 pagesTask 4 Their Choiceflory mae gudiaNo ratings yet

- Book 1947 - Eva Shaw - Divining The Future Prognostication From Astrology To ZoomancyDocument301 pagesBook 1947 - Eva Shaw - Divining The Future Prognostication From Astrology To Zoomancyantoniorios1935-1100% (1)

- Fairy Origins A Phenomenon and RealmsDocument14 pagesFairy Origins A Phenomenon and RealmsJason PowellNo ratings yet

- שדמי 2004Document24 pagesשדמי 2004Daniel WolterNo ratings yet

- EJ651686Document10 pagesEJ651686Daniel WolterNo ratings yet

- Fantasia MedievalDocument8 pagesFantasia MedievalDaniel WolterNo ratings yet

- The Power of Disney History, Gender & Disney Princesses Maya RobertsDocument28 pagesThe Power of Disney History, Gender & Disney Princesses Maya RobertsDaniel WolterNo ratings yet

- Sher-Censor & Oppenheim 2010 בנות שעוזבות לשירות צבאיDocument9 pagesSher-Censor & Oppenheim 2010 בנות שעוזבות לשירות צבאיDaniel WolterNo ratings yet

- Park Peterson 2008Document8 pagesPark Peterson 2008Daniel WolterNo ratings yet

- Neukrug 2007Document10 pagesNeukrug 2007Daniel WolterNo ratings yet

- Downey1996 Female Empowerment DisneyDocument29 pagesDowney1996 Female Empowerment DisneyDaniel WolterNo ratings yet

- 1930's America-Feminist Void MoranDocument8 pages1930's America-Feminist Void MoranDaniel WolterNo ratings yet

- Article What British Knows About Medievlism From DisneyDocument21 pagesArticle What British Knows About Medievlism From DisneyDaniel WolterNo ratings yet

- The Representation of Women in Disney Animated FilmsDocument36 pagesThe Representation of Women in Disney Animated FilmsDaniel WolterNo ratings yet

- Gender Roles and IdentityDocument7 pagesGender Roles and IdentityDaniel WolterNo ratings yet

- The World According To DisneyDocument24 pagesThe World According To DisneyDaniel WolterNo ratings yet

- Feminist View On Disney HeroinsDocument23 pagesFeminist View On Disney HeroinsDaniel WolterNo ratings yet

- The Medieval Fantasy of (Coopted) MalificentDocument18 pagesThe Medieval Fantasy of (Coopted) MalificentDaniel WolterNo ratings yet

- Enter The Castlel ReiteratingDocument19 pagesEnter The Castlel ReiteratingDaniel WolterNo ratings yet

- Disney PrincessesDocument5 pagesDisney PrincessesDaniel WolterNo ratings yet

- NecropolisDocument286 pagesNecropolisMichael Taylor75% (4)

- Thesis Statement Frankenstein Mary ShelleyDocument5 pagesThesis Statement Frankenstein Mary ShelleyDoMyPaperForMoneyDesMoines100% (2)

- Noli Me Tangere PPTDocument12 pagesNoli Me Tangere PPTEpicyouNo ratings yet

- PANITIKANDocument18 pagesPANITIKANMargie PostoriosoNo ratings yet

- BÀI TẬP THÌ TƯƠNG LAI ĐƠNDocument4 pagesBÀI TẬP THÌ TƯƠNG LAI ĐƠNDao CarolNo ratings yet

- Cerita Cinderela Dalam Bahasa Inggris: Name: Jessisca Christ Alicia Situmorang Class: X-Ips.2Document3 pagesCerita Cinderela Dalam Bahasa Inggris: Name: Jessisca Christ Alicia Situmorang Class: X-Ips.2putma5rijalhiNo ratings yet

- Practice Exercises Answers Unit 1: Exercise 1 Exercise 2Document4 pagesPractice Exercises Answers Unit 1: Exercise 1 Exercise 2Language PointNo ratings yet

- Dickens and London PDFDocument17 pagesDickens and London PDFtrishaNo ratings yet

- 01 MAMD 2021 ENG Tg5-SPM MODEL TEST-QR - FDocument19 pages01 MAMD 2021 ENG Tg5-SPM MODEL TEST-QR - FMelissa SubalNo ratings yet

- Unnamed Memory Vol 5Document407 pagesUnnamed Memory Vol 5ankurdey2002.adNo ratings yet

- Module Harry Potter and The Order of The PhoenixDocument4 pagesModule Harry Potter and The Order of The PhoenixJasmin AjoNo ratings yet

- Great American Bestsellers (Description)Document5 pagesGreat American Bestsellers (Description)ressmyNo ratings yet

- Fairest of Them All Teresa Medeiros PDFDocument2 pagesFairest of Them All Teresa Medeiros PDFSara100% (1)

- Answer These Questions Based On The Text!Document2 pagesAnswer These Questions Based On The Text!Depe AgusNo ratings yet

- Dragonwatch - A Fablehaven Adventure by Brandon Mull - PDF, EPub, Mobi - DownloadDocument1 pageDragonwatch - A Fablehaven Adventure by Brandon Mull - PDF, EPub, Mobi - DownloadAgreensprettyNo ratings yet

- BAMBOO DANCER - OdtDocument1 pageBAMBOO DANCER - OdtEaman CornellNo ratings yet

- The Most Common Irregular VerbsDocument1 pageThe Most Common Irregular VerbsDavid SteensonNo ratings yet

- 831 LiteratureDocument12 pages831 LiteratureEsther Joy HugoNo ratings yet

- How My Brother Leon Brought Home A WifeDocument1 pageHow My Brother Leon Brought Home A Wifejoepnko12375% (4)

- Indian English Literature ShodhgangaDocument26 pagesIndian English Literature ShodhgangaMajid Ali AwanNo ratings yet

- Eng5 Q2 Week7Document28 pagesEng5 Q2 Week7Randy PedrosNo ratings yet

- Dystopia As A Subversion of Utopia: Upamanyu Chatterjee's NovelsDocument4 pagesDystopia As A Subversion of Utopia: Upamanyu Chatterjee's NovelsIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- 11-12 of The Odyssey Double-Entry Journal TrueDocument3 pages11-12 of The Odyssey Double-Entry Journal TrueJohn WalishNo ratings yet

- The Actors and Actresses That Star In: Fast LayneDocument5 pagesThe Actors and Actresses That Star In: Fast LaynejoseNo ratings yet

- Narrative Text Hilmi Datu ADocument2 pagesNarrative Text Hilmi Datu AHilmiNo ratings yet

- The City of The Steam Sun JumpstartDocument22 pagesThe City of The Steam Sun Jumpstartwelly100% (1)

- Write A Story Starting With: "The Widow Had To Work Hard To Bring Up Her Little Son Alone "Document1 pageWrite A Story Starting With: "The Widow Had To Work Hard To Bring Up Her Little Son Alone "Melissa RosilaNo ratings yet