Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PhiLaw Chapter-2 2

PhiLaw Chapter-2 2

Uploaded by

Jessa Ervina Badion-GerillaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

PhiLaw Chapter-2 2

PhiLaw Chapter-2 2

Uploaded by

Jessa Ervina Badion-GerillaCopyright:

Available Formats

John Stuart Mill pointed thi s out, saying that the _need for large ~apitat

· , t d

m a ra e or business limits the competition in that business.

. · Monopolies

h · ·1 are

not necessan·1y bad 1·fthey can cut the

. costs of production

• • given t e1r• ava1 able

capital, large workforce and factories, corporate stab1hty and expenence, and

network of production facilities.

The Morality of the Free Market

Critics of the capitalist free market, or an economy free from

government intervention, say that it is selfish and anti-poor. But for economist

Walter Williams in Is Capitalism Moral? having a free market is morally and

economically superior than any other way of organizing economic behavior.

It calls for voluntary transactions between individuals choosing to pay value

for value. The money you pay is proof of the value or service you give to your

fellowman so that both buyer and seller are both better off with an agreed

just price. Enter the government imposing a fixed price and one party (usually

the seller) is worse off. While it is true that giant corporations can gain too

much power, consumers can punish them by refusing to buy their products and

shifting to another provider. Aside from the consumers, big unions also punish

and match the influence of big corporations.

In contrast, nationalizing corporations keeps inefficient corporations

afloat no matter how inferior their products are, since citizens are forced to

avail or prefer their products under government and ultimately, taxpayers'

subsidy. While consumers can fire private industries, they cannot simply put

the government out of business .

. ~apitalism does not want the government to provide for those able but

unwll_hng to w~rk a~d pa~icipate in economic output. Giving out food stamps,

fr~b1es, and tmkenng with the market only give the non-worker a sense of

enttt!e~ent to de~and services and claim the profit others worked for. Free

subsidies are "anti-worker" and in the long-run "anti-poor" since the recipient

does not learn the value and need for work. The poor is given free fish but

not taught how to fish and fend for h. If H b .

shell-outs and th , . . •mse · e egms to rely on government

government ' s mtervention

_o . ers generosity

to kee instead

. of his own industry· Furthermore, the

who will be disincentivised to 1: p~e_s 1ow m~y actually hurt poor producers,

hoard these for their own sub ?tece t ~•r goods m the cheap market but instead

.

prices, sis t nee, import

or sell to others willing h. . to countries that o ffier better

them

cheapening the price of products:!~ •gher pnce tags. Moreover, artificially

and redound to cheapening the regar: :::mers doubt ~eir qua~ity and worth

workmanship of their producers.

For George Gilder, economist of US .

free market actually channeis s If . President Ronald Reagan, a

e -interest to altruism. As business owners,

36 I Philamophta.· Pht!D,ophy and 77oeory ofPhl/;ppine law

entrepreneurs have no cho. b

desires of others-their cu1cte ut to concern themselves with the needs and

. s omers They m t d T

satisfy customer feedback If th . h us I igent1y research, know, and

without improving servic~s th e\; oos~ to be greedy, raise prices unjustly

enslave their employees then :~ ey·17~11 lose customers. If they choose to

other entrepreneurs. Capita11·sm . eyth~I ose _workers or their best talents to

, m 1s sense 1s a "com ff f · · ,,

businessman always has to ask "D th ' Id pe I ion o g1vmg. The

If he would cease to ask and r . oes e wor _want what I have to give?"

. espond to that question, he would cease to be 1·n

busmess.

accum~!~;sw!~!!h G;~s ric:? Whilliams ask. _Not because he devilishly

. . e pro ts e earned are Just proof of how much he

satisfied the_ needs of millions who are willing to reach down their pockets

to. P~Y forfh;s products. His accumulated capital is proof of his service to his

m1 11ions o 1e1lowmen.

Fair Market Economy

. s~pposed concession for private, public, and corporate ownership

ts _the fa~r market economy." Unlike in unregulated capitalism, it is not a

la~ssez-fazre free market; but unlike in Communism, neither does it forbid a

pnvate market. The principle is to "make markets free and fair." Industries

will ~emain in private or corporate ownership but the government will provide

pubhc works and ensure basic services such as social security, health care,

pension, basic education, and measures to prohibit monopolies and cartel that

prevent a free playing field in services. The emphasis is national welfare not

national income; the aim being the increase of over-all happiness, including

better living standards, not mere rise of income and gross production.

Government regulation is needed to stabilize the economy, protect both

workers and property owners, and allow profitable return of investments lest

industries close down. To temper the power of corporations engaged in vital

industries, the State can purchase shares and voting rights at fair market value

to have a say on corporate policies, but not to the extent of nationalizing the

corporation, which will discourage private investments or will politicize the

business environment. The government must also take the lead in ensuring

that government workers get competitive salaries and working environment

by raising labor standards. Furthermore, governments should not bail-out and

spoil, but let the market discipline failing banks and corporations.

The "Nordic model" of Scandinavian countries follows the social

market economy, with welfare systems that ensure a quality of life for all.

The Philippine Constitution has also adopted provisions on welfare programs

to enfranchise the marginalized and allow them to participate in the country's

economic life. Social safety nets (SSS, GSIS, PhilHealth, Pag-lbig) are available

to insure services for the working class based on their actual contributions

Legal & Philosophical Issues I 37

that should not be freely and equally " universalized" without parameters as to

disincentivize work.

Locke, the champion of property rights, advocated the limitation and

regulation of property according to one's share of labor in the Second Treatise

of Civil Government: "The measure of property nature has been well set by the

extent of men's labour and the conveniences of life xx x for, in governments

the laws regulate the right of property, and the possession of land is determined'

by positive constitutions."

For Locke, one is entitled to property not to the extent of what his money

can buy, but as much "as man tills, plants, improves, cultivates, and can use

the product of, so much is his property." This is called as the "homestead

principle" or "labor theory of property," where it is by the exertion of labor

upon natural resources that things become one's property. Based on this

principle, the Public Land Act No. 2874 granted Homestead Patents to landless

Filipinos who are able to cultivate the land they possess during the American

period.

Locke's principle gives premium to hard-earned wealth. Both the rich

and the ~ r should not be entitled to property they did not work for. Giving

free subs1d1es or estates would only reward the indolent at the expense of the

work.er who deserves the property more. l

Law, Freedom, and Duty

A law is valuable, not because it is a law, but because there is right in it.

- Henry Ward Beecher, Life Thoughts

Many of our heroes died in the f fr

valuabl than • name O eedom. For them, it is more

e . mere existence. For to be human is to be free.

. Isaiah Berlin said that freedom has two kinds· N. . ·h

IS the absence of external co . . .• · egative freedom, whic

control or rational m nstram~, and /!0Sitive freedom, which is self.

from coercive and pre~v~v~ one s a~petite~ .. Ne~ative liberty is freedoIIl

individual to control his circumstan~~hile posttive liberty is the ability of all

True freedom takes into account bo . . .. ..

Authentic freedom does not nl th J>enniss1b11ity and possib1litY.

Law in this case must not onl o bye:ean you are allowed, but you are able.

freedom of action even if no~ r . shackles but also empower. There is no

have no control or means fo hg stops you from doing What you want if you

r w at you want.

"If a man is too poor to afford . th .

- a loaf of bread, a journey round thsome ing on which there is no legal ball

e world, recourse to the law courts - he

38 f PhiLawsophui- Ph -1 hy

- l osop and Th . if . _

eory o Philzppine Lnw

is as l~ttle f_ree to have it as he would be if it were forbidden him by law," Berlin

explamed m Two Concepts of Liberty.

The d~g~~e of freedom the law can provide may vary upon the capacity

and responsibility of persons. For example, a minor or a lunatic will need a

~uardian bec~use ?e cann~t really decide for himself and exercise positive

hbe~. Negatl~e h_berty will be taken from criminals to prevent them from

harmmg and v10latmg others' liberty.

Randolph Mayes said that persons are not ordinary objects but

"reasoning objects," requiring personal space for self-determination. To

interfere with a person's choice is to interrupt his reason and right to self-

government and personal autonomy. "Liberalism" teaches that there should

be no compulsion in making choices, whether perceived good or bad, called as

the "right to choose."

Under this paradigm, choice is a value so we can pursue alternative plans

in life. Law should only prohibit one from harming others but not from harming

oneself ("harm principle"). There should be minimal state intervention in the

lives of citizens. A person has complete dominion over what he wills for his

body, his life, and his property ("libertarianism"). In other words, ''your life,

your choice."

Freedom with Duty

Totalitarian and authoritarian regimes and on one hand, traditional,

and paternalistic institutions, view liberty as freedom only to do good and

fulfill duties. Individualistic, self-interested, or anti-social behavior must be

restrained. For the ancient Chinese, all citizens are ''under one heaven" and

liberty must be exercised to promote the good of all. The power to choose is

not the same as freedom, says Edmund Burke.

In Scholasticism, one who commits vice is not really free, but a slave to

his passions. As Aristotle clarified in the Metaphysics, "the free man is he who

is his own master." Freedom is itself a good, but God gave us free will that we

may choose what is right. This is also what Kant called "moral autonomy,"

and what Rousseau referred to as "moral liberty."

According to Kant, a philosophy of freedom will be deficient without

a duty theory or deontology. How do we know what is our duty? Kant

answered that first we must find the maxim or principle of action in what we

want to do. Next, ;e must ask ourselves whether we want our choice of action

to be universal rule or law which will be fine for everyone to do under the same

circumstances.

Authentic freedom is the capacity to enjoy the good life and fulfill one's

potential and not the opportunity to do harm, whether to others or oneself.

Legal & Philosophical Issues I 39

I

1

The fact that one can choose to harm oneself means one cannot exercise right

judgment and may have to be subject to the contro l of others, such as through

guardians hip, rehabilitation , or property receivership. Self-hann is contrary

to the instinct of self-preservation. Righ ts, when not exercised properly, is

considered abdicated , thus the justifi cation for curtailing the liberty of criminal

offenders through imprisonment. A s the movie Spiderman puts it, "with great

power comes great respons ibi li ty."

Man is capable of so muc h good but a lso of so m uch evil , and the latter

must be checked by law. Disciplinary Jaw must restrain unnatural, self.

destructi ve, and unproductive desires and impul ses thro ugh penology. Social

cooperation is needed in a healthy society, and this includes fulfilling social

duties for the good of all, including the personal good of oneself. The principle

of solidarity highlights the social nature of a person , the interdependence of

each member of society, and the commitment to a common good.

Personal rights do not exist in a vacuum but has a social context. Without

a consciousness of ethical norms and duties, rights-advocacy can simply

degenerate into a liberal platform for licentious behavior, social deviancy, and

individualism . Thus, some countries, including Israel, Japan, India, and the

Scandinavia, scripted in their Constitution a fundamental bil1 of duties or

bill of responsibilities or Articles on the Duties of the People to complement

their bill of rights. There is a move in the Philippines to adopt a Bill of Rights

and Duties in the Constitution, following the Declaration of the Basic Duties

of ASEAN Peoples and Government. This has a precedent in the Karti/ya ng

Katipunan, which was worded in terms of duties.

For Rizal, the increase in duties must correspond with increase in rights.

In his essay The Philippines a Century Hence, he lamented the "increase of

duties, taxes and contributions without any corresponding increase in rights,

privileges, and liberties or an assurance of the continuation of the few existing

ones."

Rights therefore must be balanced with duties and vice versa. The term

"right" ~fter all _came_fron,i the Roman "jus," meaning "just.'' The French

R.evolutwn bad 1t saying: Liberte! Egalite! Fraternite! In this context true

freedom is not solipsistic liberty, but fraternal egalitarian liberty. '

Law, Guilt and Personal Liability

It ilJ better to risk saving a guilty person than to condemn an innocent one.

- Voltaire, Zadig

e. . When is a person guilty'? Does it require malice or the mere doing or

ia1Jure to do an act'?

. . Fr~o~ an~ responsibility are issues in criminal liability. An element of

cnmmal habihty 18 voluntariness, also call ed as "free action ." Since a person

4-0 f Philaw.wphla: Philo.1ophy and Theory of Philippine Law

will commit or omit as he thinks right the .

not matter much so long as an act. d rJresence ofmahce or good-will does

th

in aggravating penalties, the road ~: h:: :::e. Al ough ?ad faith is a factor

1

Whatever one's motivation one t b be paved with good intentions.

made not happen willingly. ' mus e responsible for what one made or

Deliberation or voluntariness is the k Ari st 1

main causes of how an act b . ey. ot e noted that there are two

ecomes mvoluntary· ignoranc d I•

Ignorance

. is lack of kn 1 d · e an compu

ow e ge or awareness of what one is doing or not s10n.

In

compulsion, however,. one. is forced to do someth"mg he would not have done

·

sueh as w hen· a• gun ts pomted into one's head · I nsam·ty may a1so be pleaded'

to excuse cnmma1 .acts due to defective mental 1acu .c. . so 1ong the disease

1ties, .

was present at. the time

. the act was committed and the defiect·1ve cond"1t1on

. has

a causal relation with the act.

But is. free will j_ust a concept? Are not our actions the result of a

conglomeration of physical, psychological, and social forces not really in our

control?

. '~Determinism" is the theory that all events are caused by antecedent

cond1~1ons ~d people .do not have much free will, but is like a complex

machine, subJect to vanous external and internal stimuli. Mental deficiencies,

heredity, hormonal imbalances, psychological lapses, biological instincts,

physical needs, traumas and syndromes, social conditioning, customs and

traditions, parental training, peer influence, environmental conditions, and

pass-on political and religious beliefs can all "conspire" to make a person

commit the perfect crime. As proof, criminal incidence is prevalent in marginal

communities because it is in these areas where people live in multiple sub-

human conditions, who do not have sufficient property, rights, and education

to direct a normal life even if they would want to.

Quantum consciousness says that things are not mechanistic as they

are supposed to be, but there is microcosmic human influence in the turn of

events. By our thoughts, intentions, actions and feelings, we emit brainwaves

and energy frequencies that can affect the tendencies of the smallest particles

of matter, especially ongoing undetermined events. Hence, human volitional

consciousness, especially when collective, may have influence on how things

behave or the outcome of events. In other words, even our circumstances may

be the accumulated result of our choices.

A version of "soft determinism" or "compatibilism" insists that

freedom is compatible with internal and external d~terminants. The antecedent

factors give us alternatives of action and tendencies but our character elects

what we will decide to do. It would be absurd if external factors are considered

but not one's personal agency. The blame game never_ends. We can always rise

out of our circumstances, especially adults psycholog1cally capable of consent.

Legal & Philosophical Issues l 41

If we deny free will, and maintain that freedom is an illusion, then we may as

well deny freedom too.

In civil damages, there is a standard of"strict liability~' where regardless

of whether the tortfeasor is at fault, one is responsible for bemg the proximate

cause without whom the damaging event, in the ordinary course of things

unbroken by an efficient intervening cause, would not arise. Strict liability

prevents defenses and justifications based on still debatable theories of human

free will and degrees of required diligence.

For instance, damages may be committed because one is drunk, and

while the psychological effect of drinking is beyond one's control, one is

responsible for getting drunk in the first place. Injuries may also be due to

an accident, but one can be inviting an accident if he failed to observe traffic

rules. Strict liability does not seek to solve the question of who is the first agent

(God? Genes? Nature?) but who is the last or proximate cause who sealed the

course of events.

Meanwhile, criminal punishment, in recent trends, has been reformed to

be more rehabilitative instead of punitive. It recognizes sociological findings

that people can be driven to commit criminal acts given their environment

and circumstances. People are responsible but not solely responsible, and

mitigating, aggravating, and special circumstances must always be appreciated.

CHAPTER I I CASE READINGS

PHILQSQPHERs QNLAWAND ACADEMIC FREEDOM

FELIXBERTO C. STA. MARIA v. SALVADOR P. LOPEZ, et aL

(G.R. No. L-30773, February 18, 1970)

CASTRO, J., concurring:

xxx

. ~ut the res~ect due the integrity of the individual is by no means

ant1thet1cal to the mterests of society On the contrary · ;:-. th

oth th h'l · , one rem1.orces e

e~, e P 1.~sopher Reinhold Niebuhr has so beautifully brought

out _m his boo~, The Children. of Light and the Children of Darkness."

Whtie sta

bourgeois d~mocracy, with its enshrining of the individual at the

cente~ ge of ~ociety, has now generally been replaced by a new social

consc1_o~sness, its emphasi~ on liberty nevertheless contains an element

~f vahd1ty that transcends its excessive individualism. Perhaps it would

e closer to the truth to say that the community re uires libe

as does the individual and the individual requ1·res q . rty as much

b · th oug ht comprehended. As Dr. Niebuhr explains:

community more than

ourge01s

42 l PhiLawsophia: Philosophy and Theory ofPhilippine Law

T?e man who searches after both meaning and fulfillments be ond

the ambiguous

· · h . h fulfillments

h" . and frustration s Of h"1story exists

. Y_

. a height

m

o· f spmt· w1 1c no 1stoncal

h . process can comPIe t e1Y contam.

. This . height

.

1s not

· me evant to

·b·l· t e hfe

. . of the communi·ty b ·

, ecause new nchness and

a higher poss1 1 ity of ~ustl~e come to the community from this height of

awareness. But the height . 1s. destroyed by any commumty · w h"1ch seeks

prematurely

. to cut off this pmnacle of m· di·v1·dual·ty 1 m· the mterest

· o f th e

community's peace and order.

And what w~s the community interest involved here? If it was

that .of. the community

. . . of students

. who massed 1·n front o f th e umvers1ty

· ·

a~1mstra~1on bml~mg, then 1t was obviously in their interest that the

stnke contmued_unttl the respondent Lopez yielded to their demand. If, on

the other hand, 1t was that of the community of students who very much

t?

wanted attend classes but were prevented from doing so, or that of the

community of professors and other scholars who could not get inside the

classrooms_ because t~ey were barred by the demonstrating students, then

the protection of t~etr rights is to be found in some solution of a police

character and not m the summary removal of the petitioner. The issue

would always thus narrow down to the vindication of a principle: The

rational solution of any controversy.

Of more than passing relevance are these sentiments articulated

by Dr. Sidney Hook of the Department of Philosophy of the New York

University, a thoughtful commentator on the contemporary university

scene: "Due process in the academic community is reliant upon the

process of nationality it cannot be the same as due process in the political

community as far as the mechanisms of determining the outcome of rational

activity. For what controls the nature and direction of due process in the

academic community is derived from its educational goal - the effective

pursuit, discovery, publication, and teaching of the truth. In the political

community all men are equal as citizens not only as participants in, and

contributors to, the political process, but as voters and decision-makers

on the primary level. Not so in the academic community. What qualifies

a man to enjoy equal human or political rights does not qualify him to

teach equally with others or even to study equally on every level. There

is an authoritative, not authoritarian, aspect of the process of teaching and

learning that depends not upon the person or power of the teacher, but

upon the authority of his knowledge, the cogency of his method, the scope

and depth of his experience. But whatever the differences in the power

of making decisions flowing from legitimate differences in educational

authority, there is an equality of learners, whether of teachers or students,

in the rational processes by which knowledge is won, methods developed,

and experience enriched."

And on the rule of reason in a liberal educational regimen,

Professor Hook gives us pause with his incisive observations: "In a liberal

educational regimen, everything is subject to the i:ule ofreaso~, and all ~e

equals as questioners and participants. Who_ever mterferes ~1th acade~ic

due process either by violence or threat of violence places himself outside

Legal & Philosophical Issues I 43

. ti sanctions appropriate. to Ththe

the

gra academic commumffi

·ty, and mcurs t lesuspension

. to expu ls1on. e

O

from censure bl " h

pecvity of his. o enses · . . . l'b ral educational esta ts ments

Of the ntuahsttc I e .h •

uliar deficiency t . f t· al due process wit appropnate

.olahons o ra ion Th .

is the failure to mee vi . 1 d intelligent manner. ere ts a

sanctions or to them in a ttm~ y anf lawless behavior on the Part of

l meet eye to expressions o d f h

tendency toh c ose an d deprive their fellow stu ents o t e

· th name of free om, c1m· · ·

students w o, m e . d' It • as if the liberal a m1stratton

freedom to pursue therr fell sit! ,es. ':inued existence by treating such

sought to appease the challenge to its ~on x x There is no panacea that can

incidents as if they had never happene . x tion of a hard line or a soft line,

be applied to all situations. It_ IS not a ques e advice from hindsight, to be

but of an intelligent line. It is easy to l ys helpful for the faculty

. d ksure after the event. But it is a wa .

wise an coc . . .delines for action, so that students will

to promulgate m advance farr gu; negotiations should be conducted

: ~ : ;:a~;x;cc!;!i;::~a;h:: administrators or faculty are held

captive."

PHILOSOPHERS ON LAW AND JUSTICE

JORGE B. VARGAS v. EMILIO RILLORAZA, et al

(G.R. No. L-1612, February 26, 1948)

PERFECTO, J., concurring:

According to Cicero "in justice the brilliance of virtue is gr:ater,

and from her they receive their name just men" (De Offic. 1., 1, Ill. de

Justitia); and Saint Thomas Aquinas maintains that ''.justice exc_els

other moral virtues" and "it is the most excellent among all other vutues

(Summa Theologica, Second Part, Cuestion XVIII, Article XII).

Although the psuedo-progressives of new pattern, those intellectual

renegades who spurn the wisdom of the ages, may not relish it, we have

to quote from Aristotle that "justice seems to be the most excellent

virtue, and that neither the afternoon star nor the morning star inspires

more admiration than her" (Ethics, 1. 5. c. 1), as "the greatest virtue as

necessan1y those which are more useful to others, because virtue is a

beneficient faculty" (Rhetor. I, I, c.9). After all, those who look farther

in the past will see better the future. Who can puU the farther back the

string of a bow, he will send the anow farther. Robert Maynard Hutchins,

President of the University of Chicago, one of the instittitions which

weatly COOtributed to the development of the atomic bomb, in the 1945

edition of his book "The High Learning in America" could not avoid

invoking several times the authority of the Stagirite. The Pleiad of great

physicists who are resPonsible for ushering of the Atomic Energy Era, the

m_ost r~volutionary in the history of humanity- Becquerel, Curie, Hertz,

ElllStem, Bohr, Smyth, Rutherford, Meitner, Oppenheimer, and many

others - themselves admitted that the ideas of Democrirus and Aristotle

on matter, on energy, on the elements of universe, expressed centuries

44 I Philaw,ophio; Phik,sophy ond Theory of Phi!;ppine Law

bef~re Christ, t~e philosopher's stone of the medieval alchemists, and

the ideas of Gahleo and Newton are direct progenitors and inspirers of

the present co~cepts on ~atter an~ energy as the different expressions

of the same thmg and which permitted the discovery of that wonderful

microcosmos where the constellations of electrons, protons, neutrons,

deuterons, photons, alpha, beta, and gamma rays, and other radiant

particles in play, offering to man the mastery it never had on physical

nature with the harnessing of the basic forces of universe.

There are thoughts and ideas bequeathed to us by great thinkers

which remain fresh and young through the ages and centuries, like the

flesh of the wooly mammoth, buried in Russian tundras, which today

can still be eaten, although the beasts died in the pre-historic darkness

of remote antiquity. Those are the thoughts and ideas insuffl.ated with the

vitality of eternal truth. They spring from the minds of the geniuses with

which Nature, once in a while, blesses certain epochs, to be the intellectual

leaders of mankind for all time.

The ignorants and retrogrades will never understand it; but it is a

fact that in the summit of his glorious career, Justice Holmes, the greatest

Judge of modern times, continued reading Aristotle. To free themselves

from the sorrows they feel with the surrounding market of vulgarity,

where pygmys and riffraffs dominate, great minds seek enjoyment in the

company of their kind. Eagles will not be happy in the society of flies and

mosquitoes. That explains the calibre of the friends Rizal had in Europe.

All these may sound esoteric to the unfortunate class of morons

or mental degenerates. We cannot help it. Our words are addressed to

persons with normal understanding.

JURISTS ON POLICE POWER, THE COMMON GOOD AND THE

GENERAL WELFARE

PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS v. JULIO POMAR

(G.R. No. L-22008, November 3, 1924)

JOHNSON, J.:

A d fi .f of the police power of the state must depend ~pon the

. l el m iond the particular facts to which it is to be applied. The

part1cu ar aw an . b th hi best courts may be

many definitions which have been given_ _Y e g ·de to

. h ose of givmg us a compass or gm

exammed, however, for t e purp . . the particular case before

assist us in arriving at a correct cone1us1otn itnexpounders of the common

S . w·11· Bl kstone one of the grea es

us. Ir 1 1am ac. ' r as "the due regu1a11· 0 n and domestic order of

law, defines the po1ice pow~ . f tate like members of a well-

kin d h b the mhab1tants o a s ,

the g om, w ere Y ti their general behavior to the rules

nd

governed family, are ~ou to co; ~: ood manners, and to be decent,

of propriety, go~ ne1gh~or~ootheir re;pective stations" (4 Blackstone s

industrious, and moffensive m

Commentaries, 162).

Legal & Philosophical Issues I 45

Mr. Jeremy Bentham, in his General View of Public Offenses, g~ves

us the following definition: "Police is in general a system ~f precaution,

either for the prevention of crimes or of calamities. Its busmess ~ay be

distributed into eight distinct branches: (1) Polic_e_for the pre_vent1on of

offenses; (2) police for the prevention of calam1t1es; (3) ~ohce _for ~e

prevention of endemic diseased; (4) police of charity; (5) pol!ce of mtenor

communications; (6) police of public amusements; (7) pohce for recent

intelligence; (8) police for registration."

Mr. Justice Cooley, perhaps the greatest expounder of the American

Constitution, says: "The police power is the power vested in the legis-

lature by the constitution to make, ordain, and establish all manner of

wholesome and reasonable laws, statutes, and ordinances, either with

penalties or without, not repugnant to the constitution, as they shall judge

to be for the good and welfare of the commonwealth, and of the subject of

s

the same. x x x" (Cooley Constitutional Limitations, p. 830).

In the case of Commonwealth ofMassachusetts v. Alger, 7 Cushing,

53, we find a very comprehensive definition of the police power of the state.

In that case it appears that the colony of Massachusetts in 1647 adopted an

Act to preserve the harbor of Boston and to prevent encroachments therein.

The defendant unlawfully erected, built, and established in said harbor,

and extended beyond said lines and into and over the tide-water of the

Commonwealth a certain superstructure, obstruction and encumbrance.

Said Act provided a penalty for its violation of a fine of not less than

$1,000 nor more than $5,000 for every offense, and for the destruction of

said buildings, or structures, or obstructions as a public nuisance. Alger

was arrested and placed on trial for violation of said Act. His defense

was that the Act of 1647 was illegal and void, because if permitted the

destruction of private property without compensation. Mr. Justice Shaw,

spe~g for the court in that said: "We think it is a settled principle,

growmg out of the nature of well-ordered civil society, that every holder

of property, however absolute and unqualified may be his title holds it

under the i~p!ie~ liability that his use of it may be so regulat;d, that it

s~ll not be •~urious to the equal environment of others having an equal

nght to ~e enJoyment of their property nor injurious to the rights of the

commumty. Al_l prope~ in this commonwealth, as well that in the interior

: that bordenng on tide waters, is derived directly or indirectly from

e government and held subject to those general regulations which are

1 ll~thto the_common good and general welfare. Dinl.ts ~f property

nl.eceske

a o er social and c f I · "'-16" '

limitations in th . . onven Iona nghts, are subject to such reasooable

and to sueh reasonable1r enJ,oyment, as shall prevent them from being m·,iun'ous

trai · :.1 '

legislature under th e res _nts and regulations established by law, as the

the consti~tion ma~ ~:~;mmg I and controlling power vested in them by

further adds· ..; x Th necessary and expedient." Mr. Justice Shaw

· x e power we allude to · th th .

the power vested in th 1 . 1s ra er e pohce power,

1

and establish all maiu:ere:~s ai;;; by tbe constitlation, to make, ordain

O

w esome and reasonable laws, statutes

46 I Philawsophia: Philosophy and Theory ol"Ph ·1 · . L

'J , 1pp1ne aw

and ordinances, either with penalties or without, not repugnant to the

constitution, as they shall judge to be for the good and welfare of the

commonwealth, and of the subjects of the same."

This court has, in the case of Case v. Board of Health and Heiser,

24 Phil., 250, in discussing the police power of the state, had occasion

to say: "x x x It is a well settled principle, growing out of the nature of

well-ordered and civilized society, that every holder of property, however

absolute and unqualified may be his title, holds it under the implied liability

that his use of it shall not be injurious to the equal enjoyment of others

having an equal right to the enjoyment of their property, nor injurious

to the rights of the community. All property in the state is held subject

to its general regulations, which are necessary to the common good and

general welfare. Rights of property, like all other social and conventional

rights, are subject to such reasonable limitations in their enjoyment as

shall prevent them from being injurious, and to such reasonable restraints

and regulations, established by law, as the legislature, under the governing

and controlling power vested in them by the constitution, may think

necessary and expedient. The state, under the police power is possessed

with plenary power to deal with all matters relating to the general health,

morals, and safety of the people, so long as it does not contravene any

positive inhibition of the organic law and providing that such power is not

exercised in such a manner as to justify the interference of the courts to

prevent positive wrong and oppression."

CYBERLIBEL, PROOF QF TRUTHAND RESTRICTIONS TQ

FREEDOM QFSPEECH

JOSE JESUS M. DISINI, JR., et al v. THE SECRETARY OF

JUSTICE, et al

(G.R. No. 20333S, February 11, 2014)

ABAD,J.:

But, where the offended party is a private individual, the prosecution

need not prove the presence of malice. The law explicitly presumes its

existence (malice in law) from the defamatory character of the assailed

statement. For his defense, the accused must show that he has a justifiable

reason for the defamatory statement even if it was in fact true.

Petitioners peddle the view that both the penal code and the

Cybercrime Prevention Act violate the country's obligations under the

International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). They point

out that in Adonis v. Republic of the Philippines, the United Nations

Human Rights Committee (UNHRC) cited its General Comment 34 to

the effect that penal defamation laws should include the defense of truth.

But General Comment 34 does not say that the truth of the

defamatory statement should constitute an all-encompassing defense.

Legal & Philosophical Issues I 47

. h pens Artie . 1e 361 reco gn,·zes truth as a defense

. but under the

As it ap that 'the accused has been prompted in making the statement by

condition

good motives and for justifiable ends. Thus:

. roo f o f the truth. - In every criminal prosecution

361 P for

Art. d .f .

libel the truth may be given in evidence to the court an J it a~pears

that ,the matter charged as libelous is true, and, moreover, that it was

published with good motives and for justifiable ends, the defendants shall

be acquitted.

Proof of the truth of an imputation of an act or omission not

constituting a crime shall not be admitted, unless the imputation shall have

been made against Government employees with respect to facts related to

the discharge of their official duties.

In such cases if the defendant proves the truth of the imputation

made by him. he shall be acquitted.

Besides, the lJNHRC did not actually enjoin the Philippines,

as petitioners urge, to decriminalize libel. It simply suggested that

defamation laws be crafted with care to ensure that they do not stifle

freedom of expression. Indeed, the ICCPR states that although everyone

should enjoy freedom of expression, its exercise carries with it special

duties and responsibilities. Free speech is not absolute. It is subject to

certain restrictions, as may be necessary and as may be provided by law.

The Court agrees with the Solicitor General that libel is not a

constitutionally protected speech and that the government has an obligation

to protect private individuals from defamation. Indeed, cyberlibel is

actually not a new crime since Article 353, in relation to Article 355 of the

Penal Code, already punishes it. In effect, Section 4(cX4) above merely

affirms that online defamation constitutes "similar means" for committing

libel

But the Court's acquiescence goes only insofar as the cybercrime

law penalizes the author of the libelous statement or article. Cyberlibel

brings with it certain intricacies, unheard of when the penal code

provisions on libel were enacted. The culture associated with internet

media is distinct from that of print.

. The intern~ is characterized as encouraging a freewheeling,

an~g-goes wnttng style. In a sense, they are a world apart in terms

~f qu1ekness of the reader's reaction to defamatory statements ted

m cyh-.-___ facir• 1 ..+~...i b . pos

~"V~, st .~ Y one-cbck reply options offered by the

: ~ ~ g te as well as_by the speed with which such reactions are

down the lme to other internet users. Whether these

:;"'ons .'° defarnato,y 5taremeat JlOSted on the internet constitute aiding

abetting

another matter libel,

thatacts

th Co that Section·1 5 of the cybercrime law Punishes' is

of the law. e Urt W1 I deal With next in relation to Section 5

4B I Ph;J.,,_,phia, Philow,,hy and 1neory of Philippine I.Aw

PUBLICAND SECULAR MQRALITYAS PREVAILING

NORM QF CONDUCT

CHERYLL SANTOS LEUS v. ST. SCHOLASTICA'S COLLEGE

WESTGROVE

(G.R. No. 187226, January 28, 2015)

REYES,J.:

. Howe~er, determining what the prevailing norms of conduct are

considered disgraceful or immoral is not an easy task. An individual's

per_c eption of what is moral or respectable is a confluence of a myriad

of influence~, such as religion, family, social status, and a cacophony of

others. In this regard, the Court's ratiocination in Estrada v. Escritor is

instructive.

In Estrada, an administrative case against a court interpreter

charged with disgraceful and immoral conduct, the Court stressed that in

determining whether a particular conduct can be considered as disgraceful

and immoral, the distinction between public and secular morality on the

one hand, and religious morality, on the other, should be kept in mind.

That the distinction between public and secular m,orality and religious

morality is important because the jurisdiction of the Court extends only to

public and secular morality. The Court further explained that:

The morality referred to in the law is public and necessarily secular,

not religious x x x. "Religious teachings as expressed in public debate may

influence the civil public order but public moral disputes may be resolved

only on grounds articulable in secular terms." Otherwise, if government

relies upon religious beliefs in formulating public policies and morals,

the resulting policies and morals would require conformity to what some

might regard as religious programs or agenda. The non-believers would

therefore be compelled to conform to a standard of conduct buttressed by

a religious belief, i.e., to a "compelled religion," anathema to religious

freedom. Likewise, if government based its actions upon religious beliefs,

it would tacitly approve or endorse that belief and thereby also tacitly

disapprove contrary religious or non-religious views that would not

support the policy. As a result, government will not provide full religious

freedom for all its citizens, or even make it appear that those whose beliefs

are disapproved are second-class citizens. Expansive religious freedom

therefore requires that government be neutral in matters of religion;

governmental reliance upon religious justification is inconsistent with this

policy of neutrality.

In other words, government action, including its proscription of

immorality as expressed in criminal law like concubinage, must have a

secular purpose. That is, the government proscribes this conduct because

it is "detrimental (or dangerous) to those conditions upon which depend

the existence and progress of human society" and not because the

conduct is proscribed by the beliefs of one religion or the other. Although

Legal & Philosophical Issues I 49

d 'tt dl moral judgments based on religion might have a hcompelling .

a m1 e Y, d . blic deliberations over w at actions

influence on t~ose engage 1ts:p~robation punishable by law. After all,

would be cons,~;:!;::;::: 0 ; 3 religion and thus have religious opinions

they might also .h mpelling influence on them; the human mind

and moral codes wit a co . . • f .

l

endeavors to regu a e e t th temporal and spiritual

. mstltutlons o

· 1 society

•m a umform

· manner, a h nnonizing earth with

. . heaven.

• • · · · yd put, a

Succmct

law could be re l.1g10

· us or Kantian or Aqmman .or utihtanan

. m its eepest

roots, but it must have an articulable an~ _discernible secular ~~ose

and justification to pass scrutiny of the rehgion clauses. x x x. (Citations

omitted and emphases ours)

Accordingly, when the law speaks of immoral or, .nec~ssarily,

disgraceful conduct, it pertains to public and secular morahty; i~ refers

to those conducts which are proscribed because they are detrimental

to conditions upon which depend the existence and progress of human

society. Thus, in Anonymous v. Radam, an administrative case involving

a court utility worker likewise charged with disgraceful and immoral

conduct, applying the doctrines laid down in Estrada, the Court held that:

For a particular conduct to constitute "disgraceful and immoral"

behavior under civil service laws, it must be regulated on account of the

concerns of public and secular morality. It cannot be judged based on

personal bias, specifically those colored by particular mores. Nor should

it be grounded on "cultural" values not convincingly demonstrated to have

been recognized in the realm of public policy expressed in the Constitution

and the laws. At the same time, the constitutionally guaranteed rights

(such as the ~ght to privacy) should be observed to the extent that they

protect behavior that may be frowned upon by the majority.

EQUAL PROTECTION COMPATIBLE WITH REASONABLE

CLASSIFICATIOJY.

FERDINAND R. VILLANUEVA v. JUDICIAL AND BAR

COUNCIL

(G.R. No. 211833, April 7, 2015)

REYES,J.:

There is no question that me em

basis to screen applicants who ann t b P1~ys standards to have a rational

to a vacancy in the judiciary ~o d e I acco~odated and appointed

the applicants, and not to di;c . ermme _who is best qualified among

or class. nmmate agamSt any Particular individual

The equal protection clause of th . .

t~e _universal application of the I e Constitution does not require

d1stmc!ion; what it requires is sim ;ws to _all persons or things without

accordmg to a valid classificatio p ~quahty among equals as determined

sol n. ence, the Court has affirmed that if

Philawsophia: Philosophy and Th

eory of Philippine Law

a la~ neit?er burdens a fundamental right nor targets a suspect class, the

classification stands as long as it bears a rational relationship to some

legitimate government end.

The equal protection clause, therefore, does not preclude

classification ofindividuals who may be accorded different treatment under

the law as long as the classification is reasonable and not arbitrary. The

mere fact that the legislative classification may result in actual inequality

is not violative of the right to equal protection, for every classification

of persons or things for regulation by law produces inequality in some

degree, but the law is not thereby rendered invalid.

That is the situation here. In issuing the assailed policy, the JBC

merely exercised its discretion in accordance with the constitutional

requirement and its rules that a member of the Judiciary must be of proven

competence, integrity, probity and independence.

EQUAL DISTRIBUTION OF WEALTH VIOLATES THE RIGHT TO

PRIVATE PROPERTY

JUSTA G. GUIDO v. RURAL PROGRESS ADMINISTRATION, c/o

FAUSTINO AGUILAR

(G.R. No. L-2089, October 31, 1949)

TUASON~J.:

There are indeed powerful considerations, aside from the intrinsic

meaning of Section 4 of Article XIII of the Constitution, for interpreting

Act No. 539 in a restrictive sense. Carried to extremes, this Act would

be subversive of the Philippine political and social structure. It would

be in derogation of individual rights and the time-honored constitutional

guarantee that no private property of law. The protection against

deprivation of property without due process for public use without just

compensation occupies the forefront positions (paragraphs 1 and 2) in the

Bill for private use relieves the owner of his property without due process

of law; and the prohibition that "private property should not be taken for

public use without just compensation" (Section 1 [par. 2}, Article III, ofthe

Constitution) forbids necessary implication the appropriation of private

property for private uses (29 C.J.S., 819). It has been truly said that the

assertion of the right on the part of the legislature to take the property of

and citizen and transfer it to another, even for a full compensation, when

the public interest is not promoted thereby, is claiming a despotic power,

and one inconsistent with very just principle and fundamental maxim of a

free government (29 C.J.S., 820).

Hand in hand with the announced principle, herein invoked,

that "the promotion of social justice to insure the well-being and

economic security of all the people should be the concern of the state,"

is a declaration, with which the former should be reconciled, that "the

Legal & Philosophical Issues I 5l

Philippines is o Republican stnto" created to secure to the f ilipfno r>copl

.. the blessings of independence under a regime of justice, li berty an:

democracy." Democracy, os a way of li fe enshrined in the Constitution

embraces os its necessary components freedom of conscience. freedo~

of express ion, and freedom in the pursuit of happiness. Along with these

freedoms ore included economic freedom and freedom of enterprise

within reasonable bounds and under proper contro l. In paving the way

for the breaking up of existing large estates, trust in perpetuity, feudalism

and their concomitant evils, the Constitution did not propose to destroy 0 ;

undermine the property right or to advocate equal distribution of wealth

or to authorize of what is in excess of one's personal needs and the giving

of it to another. Evincing much concern for the protection of property, the

Constitution distinctly recognize the preferred position which real estate

has occupied in law for ages. Property is bound up with every aspects of

social life in a democracy as democracy is conceived in the Constitution.

The Constitution owned in reasonable quantities and used legitimately,

plays in the stimulation to economic effort and the formation and growth

of a social middle class that is said to be the bulwark of democracy and the

backbone of every progressive and happy country.

The promotion of social justice ordained by the Constitution does

not supply paramount basis for untrammeled expropriation of private

land by the Rural Progress Administration or any other government

instrumentality. Social justice does not champion division of property or

equality of economic status; what it and the Constitution do guaranty are

equality of opportunity, equality of political rights, equality before the

law, equality between values given and received on the basis of efforts

exerted in their production. As applied to metropolitan centers, especially

Manila, in relation to housing problems, it is a command to devise, among

other social measures, ways and means for the elimination of slums,

shambles, shacks, and house that are dilapidated, overcrowded, without

ventilation, light and sanitation facilities, and for the construction in their

place of decent dwellings for the poor and the destitute. As will presently

be shown, condemnation of blighted urban areas bears direct relation to

public safety health, and/or morals, and is legal.

THE TRAGEDYQF CQMMQNS

PRYCE CORPORATION v. CHINA BANKING CORPORATION

(G.R. No. 172302, February 18, 2014)

LEONEN,J.:

Rather than let struggling corporations slip and vanish, the better

option is to allow commercial courts to come in and apply the process for

corporate rehabilitation.

This option is preferred so as to avoid what Garrett Hardin called the

Tragedy of Commons. Here, Hardin submits that ..coercive government

.sz I Ph /Lawsophia : Philosophy a nd Theory of Philippine Law

regulation is necessary to prevent the degradation of common-pool

resources [since] individual resource appropriators receive the full benefit

of their use and bear only a share of their cost." By analogy to the game

theory, this is the prisoner's dilemma: "Since no individual has the right

to control or exclude others, each appropriator has a very high discount

rate [with] little incentive to efficiently manage the resource in order to

guarantee future use." Thus, the cure is an exogenous policy to equitably

distribute scarce resources. This will incentivize future creditors to

continue lending, resulting in something productive rather than resulting

in nothing.

In fact, these corporations exist within a market. The General Theory

of Second Best holds that "correction for one market imperfection will not

necessarily be efficiency-enhancing unless [there is also] simultaneous

[correction] for all other market imperfections." The correction of one

market imperfection may adversely affect market efficiency elsewhere,

for instance, "a contract rule that corrects for an imperfection in the

market for consensual agreements may [at the same time] induce welfare

losses elsewhere." This theory is one justification for the passing of

corporate rehabilitation laws allowing the suspension of payments so that

corporations can get back on their feet.

As in all markets, the environment is never guaranteed. There are

always risks. Contracts are indeed sacred as the law between the parties.

However, these contracts exist within a society where nothing is risk-free,

and the government is constantly being called to attend to the realities of

the times.

Corporate rehabilitation is preferred for addressing social costs.

Allowing the corporation room to get back on its feet will retain if not

increase employment opportunities for the market as a whole. Indirectly,

the services offered by the corporation will also benefit the market as

"[t]he fundamental impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in

motion comes from [the constant entry of] new consumers' goods, the

new methods of production or transportation, the new markets, [and] the

new forms of industrial organization that capitalist enterprise creates."

MARKETS MUST BE FAIR TO BE FREE

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION v. INTERPORT

RESOURCES CORPORATION, et aL

(G.R. No. 135808, October 6, 2008)

TINGA, J., concurring opinion:

The securities market, when active and vibrant, is an effective engine

of economic growth. It is more able to channel capital as it tends to favor

start-up and venture capital companies. To remain attractive to investors,

however the stock market should be fair and orderly . All the regulations,

all the r;quirements, all the procedures and all the people in the industry

legal & Philosophical issues I 53

h' wed ob.~ec ti·ve · Manipulative devices and

should

d strive to achieve t . t~ av~ 'd trading throw a monkey wrench

. • l dmg ms1 er • d ·

eceptive practices, fme u . . . d try When someone tra es In the

h cunttes m us · • .

right into the heart o t e se . h £ of highly valuable secret tnstde

market with unfair advantage :~ :::frauded. All of the mechanism,

infonnation, all other parttctp b of stock market scandals coupled With

become worthless. Gtven eno:arket such abuses could presage a severe

drainrelated

the loss ofAnd

of capital. fat thmvestors

ID the wou id eventually feel more secure With

their money invested elsewhere. .

.. k t is imbued with public interest and as such It

The secunhes mar e iven for securities regulation are

is regulated. Specifically, the reasons g . nnational needs of investors

( 1) to protect investors, (2) _to supply the IDfoh fundamental value of th~

(3) to ensure that stock pnces conform to t e

companies traded, (4) to allow shareholders to gai~ greater c~ntrol o~er

their corporate managers,

and. access to capital. and (5) to foster economic growth, mnovatton

In checking securities fraud, regulation of the stock market ~ssumes

quite a few forms, the most common being disclosure regulation and

financial activity regulation.

xxx

Yet there is an underlying dangerous implication to respondents'

arguments which makes the Courts rejection thereof even more laudable.

The ability ofthe SEC to effectively regulate the securities market depends

on the breadth of its discretion to undertake regulatory activities. The

intractable adherents of laissez-faire absolutism may decry the fact that

there exists an SEC in the first place, yet it is that body which assures the

protection of interests of ordinary stockholders and investors in the capital

markets, interests which may be overlooked by the issuers of securities

and their corporate overseer, whose own interests may not necessarily

align with that of the investing public. A free market that is not a fair

market is not truly free, even if left unshackled by the State as it would

in fact be shackled by the uninhibited greed of on]y the largest players.

!JNNEGIJGENCF, INTENT, ntonm AND M-Wa.

AR'rEMio VILLAREAL v. PEOPI,E OF THE PlfILIPPINEs

(G.R. No. 1S12S8, December t, 2014)

SERENO, CJ.:

Reckless imprudence consists i l tary . .

doing or falling to do an act fr h. h n vo un ' but without malice,

of inexcUsable lack of Precao; w tc :;'aleria!

damage results by reason

or failing to I>erfonn such ac:' : on _t e Pan ?f the Person perfonning

or occupation, degree of . 'teu· ng mto consideration his employment

circumstances regarding ID tgence, PhYstca] condition and other

persons, tune and place.

541 Philawsophia · Ph·l h

. l osop !Y and Theory ofPhilippine Law

Simple imprudence consists in the lack of precaution displayed in

those cases in which the damage impending to be caused is not immediate

nor the danger clearly manifest. (Emphases supplied)

On the other hand, intentional felonies concern those wrongs in

which a deliberate malicious intent to do an unlawful act is present. Below

is our exhaustive discussion on the matter: Our Revised Penal Code

belongs to the classical school of thought. x x x The identity of mens rea

- defined as a guilty mind, a guilty or wrongful purpose or criminal intent

- is the predominant consideration. Thus, it is not enough to do what the

law prohibits. In order for an intentional felony to exist, it is necessary that

the act be committed by means of dolo or "malice."

The term "dolo" or "malice" is a complex idea involving the

elements of freedom, intelligence, and intent. x x x The element of intent

- on which this Court shall focus - is described as the state of mind

accompanying an act, especially a forbidden act. It refers to the purpose of

the mind and the resolve with which a person proceeds. It does not refer to

mere will, for the latter pertains to the act, while intent concerns the result

of the act. While motive is the "moving power" that impels one to action

for a definite result, intent is the "purpose" of using a particular means

to produce the result. On the other hand, the term "felonious" means,

inter alia, malicious, villainous, and/or proceeding from an evil heart or

purpose. With these elements taken together, the requirement of intent in

intentional felony must refer to malicious intent, which is a vicious and

malevolent state of mind accompanying a forbidden act. Stated otherwise,

intentional felony requires the existence of do/us ma/us - that the act or

omission be done "willfully," "maliciously," "with deliberate evil intent,"

and '<with malice aforethought." The maxim is actus non facit reum,

nisi mens sit rea - a crime is not committed if the mind of the person

performing the act complained of is innocent. As is required of the other

elements of a felony, the existence of malicious intent must be proven

beyond reasonable doubt.

XXX

The presence of an initial malicious intent to commit a felony is

thus a vital ingredient in establishing the commission of the intentional

felony of homicide. Being ma/a in se, the felony of homicide requires the

existence of malice or dolo immediately before or simultaneously with

the infliction of injuries. Intent to kill - or animus interficendi - cannot

and should not be inferred, unless there is proof beyond reasonable doubt

of such intent. Furthermore, the victim's death must not have been the

product of accident, natural cause, or suicide. If death resulted from an

act executed without malice or criminal intent - but with lack of foresight,

carelessness, or negligence - the act must be qualified as reckless or

simple negligence or imprudence resulting in homicide.

XXX

In order to be found guilty of any of the felonious acts under

Articles 262 to 266 of the Revised Penal Code, the employment of

Legal & Philosophical Issues I ss

• 1 tnJunes

phys1ca • • · m ust be coupled with do/us ma/us. As an

. fund I ·act that

· · is

mala m . se, th e ex1.stence

· of malicious intent 1s . . amenta

. .n.., smce Ill.Jury

.

arises from the mental state of the wrongdoer - zmurza ex a»ectufacientis

•

cons,stat. If there is no criminal intent, the accused

f h · cannot

I · · be · found

guilty of an intentional felony. Thus, in case o_ p ys~ca 1~~e_s und_der

th R

e evtse · d Penal Code • there must be a spec1. 6 c ·ammus · zmurzan llbez or

malicious intention to do wrong against th~ phys1ca.11~tegnty or ~e i~g

of a person, so as to incapacitate and depnve the v1ct1m of ce~m bodlly

functions. Without proof beyond reasonable doubt of the reqmred animus

iniuriandi the overt act of inflicting physical injuries per se merely

satisfies the elements of freedom and intelligence in an intentional felony.

The commission of the act does not, in itself, make a man guilty unless

his intentions are.

Thus, we have ruled in a number of instances that the mere

infliction of physical injuries, absent malicious intent, does not make a

person automatically liable for an intentional felony. x x x.

xxx

The absence of malicious intent does not automatically mean,

however, that the accused fraternity members are ultimately devoid of

criminal liability. The Revised Penal Code also punishes felonies that are

committed by means of fault (culpa). According to Article 3 thereof, there

is fault when the wrongful act results from imprudence, negligence, lack

of foresight, or lack of skill.

Reckless imprudence or negligence consists of a voluntary act

done without malice, from which an immediate personal hann, injury or

material damage results by reason of an inexcusable lack of precaution or

advertence on the part of the person committing it. In this case, the danger

is visible and consciously appreciated by the actor. In contrast, simple

imprudence or negligence comprises an act done without grave fault, from

which an injury or material damage ensues by reason of a mere lack of

foresight or skill. Here, the threatened harm is not immediate, and the

danger is not openly visible.

The test for determining whether or not a person is negligent in

doing an act is as follows: Would a prudent man in the position of the

person to whom negligence is attributed foresee hann to the person

injured as a reasonable consequence of the course about to be Pursued?

If_so, the law imPoses on the doer the duty to take !)reeaution against the

mtscbievous results of the act. Failure to do so constitutes negligence.

. As we held in Ga;d v. People, for a P<rson to avoid being cluuged

wnb recklessness, the degree of precaution and diligence required varies

wtth the degree of the danger involved. If, on account of a certain line

of conduc~ the danger of causing harm to another person is greai, the

mdtvtdual who cbnoses to follow that J>articular course of conduct is

bound to be very carefu~ in onler to prevent or avoid damage or injury.

56) Phil.,awsophUr PhHosDphy and Theory of PhUipp;n, Law

In contrast, if the danger is minor, not much care is required. It is thus

possible that there are countless degrees of precaution or diligence that

may be required of an individual, "from a transitory glance of care to

the most vigilant effort." The duty of the person to employ more or less

degree of care will depend upon the circumstances of each particular case.

(Emphases supplied, citations omitted)

Legal & Philosophical issues I 57

You might also like

- Profitable Gold Trading StrategiesDocument12 pagesProfitable Gold Trading StrategiesDelorme Wycliffe Daryl91% (22)

- A Marketing Plan For Launch of New Soap Betwen Price of 15 and 20Document46 pagesA Marketing Plan For Launch of New Soap Betwen Price of 15 and 20Vihan Shukla54% (50)

- The Good Society - Matt KoehlDocument8 pagesThe Good Society - Matt Koehlulfheidner9103100% (1)

- Loan Pricing 916Document22 pagesLoan Pricing 916Gonçalo MadalenoNo ratings yet

- The Wolf - Strategy PDFDocument6 pagesThe Wolf - Strategy PDFSiva Sangari100% (1)

- The Contradictions of Free Market Doctrine: Is There A Solution?Document18 pagesThe Contradictions of Free Market Doctrine: Is There A Solution?Ivica KelamNo ratings yet

- Study Guide To Human Action by Robert P. Murphy: Chapter XV. The MarketDocument9 pagesStudy Guide To Human Action by Robert P. Murphy: Chapter XV. The MarketPeter LapsanskyNo ratings yet

- Rent Control: The Perennial Folly (Cato Public Policy Research Monograph No. 2)From EverandRent Control: The Perennial Folly (Cato Public Policy Research Monograph No. 2)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Role of A Business - Koontz and FulmerDocument4 pagesRole of A Business - Koontz and Fulmerniks220989No ratings yet

- 2018-Ag-3423 ALi SHERDocument11 pages2018-Ag-3423 ALi SHERALI SHER HaidriNo ratings yet

- Understanding Business 9th Edition Nickels Test BankDocument25 pagesUnderstanding Business 9th Edition Nickels Test BankSeanMorrisonsipn100% (36)

- The Politically Incorrect Guide to CapitalismFrom EverandThe Politically Incorrect Guide to CapitalismRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Market Dilemmas of Norton AugustDocument17 pagesThe Market Dilemmas of Norton AugustSharath NairNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics - Chp3Document33 pagesBusiness Ethics - Chp3Sueraya ShahNo ratings yet

- The Moral Dimensions of PovertyDocument6 pagesThe Moral Dimensions of PovertyAlex MingNo ratings yet

- Mukul Anand - Writing Sample 1Document7 pagesMukul Anand - Writing Sample 1Anand MukulNo ratings yet

- Rudiments of An Economic SystemDocument3 pagesRudiments of An Economic SystempetewcNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document18 pagesChapter 3Harzma MamatNo ratings yet

- (English) Is Capitalism Moral - (DownSub - Com)Document3 pages(English) Is Capitalism Moral - (DownSub - Com)Monnu montoNo ratings yet

- Globalization of CapitalismDocument3 pagesGlobalization of CapitalismSarah-Jessik LinNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Understanding Business 9th Edition Nickels Test Bank PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Understanding Business 9th Edition Nickels Test Bank PDFsoutaneetchingnqcdtv100% (15)

- Chapter 3 The Business System: Government, Markets, and International TradeDocument23 pagesChapter 3 The Business System: Government, Markets, and International TradeLH50% (4)

- EcoJustice QuotesDocument3 pagesEcoJustice QuotesErick LagdameoNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics-502: BBA - 6 (B)Document46 pagesBusiness Ethics-502: BBA - 6 (B)Hadier AliNo ratings yet

- The Challenge of UtilitarianismDocument10 pagesThe Challenge of Utilitarianismcamille εϊзNo ratings yet

- 4.Adam Smith and the Modern EconomicsDocument8 pages4.Adam Smith and the Modern EconomicsAnushkaNo ratings yet

- Law and EconomicsDocument13 pagesLaw and Economicshrishabh KhatwaniNo ratings yet

- D) Resource Allocation in Different Economic Systems and Issues of TransitionDocument4 pagesD) Resource Allocation in Different Economic Systems and Issues of TransitionSameera ShahzadNo ratings yet

- Full Download Understanding Business 9th Edition Nickels Test BankDocument35 pagesFull Download Understanding Business 9th Edition Nickels Test Bankleuterslagina100% (31)

- Graedig Which Means Always Hungry For More'. We All Have The Potential For Greedy TendenciesDocument2 pagesGraedig Which Means Always Hungry For More'. We All Have The Potential For Greedy TendenciesGail DomingoNo ratings yet

- Capitalism: LT Essays #3Document18 pagesCapitalism: LT Essays #3Rishabh JainNo ratings yet

- IRM Week 1Document16 pagesIRM Week 1kekeNo ratings yet

- British Political EconomyDocument22 pagesBritish Political EconomyDimiNo ratings yet

- That Works Efficiently Without Much Government InterventionDocument10 pagesThat Works Efficiently Without Much Government InterventionBTSAANo ratings yet

- Unit 7. Revision and ConclusionDocument5 pagesUnit 7. Revision and ConclusionAryla AdhiraNo ratings yet

- 5402 1Document14 pages5402 1Inzamam Ul Haq HashmiNo ratings yet

- The Wealth of Nations Summary ReviewDocument6 pagesThe Wealth of Nations Summary ReviewMichael MarioNo ratings yet

- The Wisdom of Frédéric BastiatDocument13 pagesThe Wisdom of Frédéric BastiatBob WeeksNo ratings yet

- Invisible HandDocument12 pagesInvisible HanddebangeesahooNo ratings yet

- Hoover & Roosevelt QuotesDocument2 pagesHoover & Roosevelt QuotesalejandracstllnsNo ratings yet

- The Principle of Increasing Marginal Utility Costs States That After A Certain Point, Each Additional Item The Seller Produces Costs Him More To Produce Than Earlier Items, Discuss BrieflyDocument21 pagesThe Principle of Increasing Marginal Utility Costs States That After A Certain Point, Each Additional Item The Seller Produces Costs Him More To Produce Than Earlier Items, Discuss BrieflyMohammad AnasNo ratings yet

- 02 Market FailureDocument27 pages02 Market FailureOscar OkothNo ratings yet

- Case DigestsDocument11 pagesCase DigestsErnie GultianoNo ratings yet

- Before Test Walk Thru (BGS)Document9 pagesBefore Test Walk Thru (BGS)Sandeep RajNo ratings yet

- Presentation By-DibyajyotiDocument8 pagesPresentation By-DibyajyotiSohan Mohapatra100% (1)

- SubjectiveDocument21 pagesSubjectiveirtaza HashmiNo ratings yet

- Principle 7 FINALDocument5 pagesPrinciple 7 FINALJanine AbucayNo ratings yet

- Understanding Canadian Business Canadian 8th Edition Nickels Test BankDocument6 pagesUnderstanding Canadian Business Canadian 8th Edition Nickels Test BankIsabellaNealaiys100% (42)

- TABL Final AssignmentDocument5 pagesTABL Final AssignmentMilton ChngNo ratings yet

- Unified Theory of Social Systems - Jaroslav Vanek. Chapter 9Document5 pagesUnified Theory of Social Systems - Jaroslav Vanek. Chapter 9Sociedade Sem HinoNo ratings yet

- Business EthicsDocument20 pagesBusiness EthicsSumon AkhtarNo ratings yet

- 4TH QuizDocument3 pages4TH QuizRem AstihNo ratings yet

- Velasquez C3Document19 pagesVelasquez C3Eugenia TohNo ratings yet

- Monopoly Term PaperDocument10 pagesMonopoly Term Paperapi-258247195No ratings yet

- Do We Own Ourselvesii/Libertarianism: Each FallDocument4 pagesDo We Own Ourselvesii/Libertarianism: Each Fallsahil choudharyNo ratings yet

- Market Failure and The Case of Government InterventionDocument16 pagesMarket Failure and The Case of Government InterventionCristine ParedesNo ratings yet

- Economic LiberalismDocument3 pagesEconomic LiberalismLauraMontecinosNo ratings yet

- Capitalism Socialism: Us Economic SystemDocument6 pagesCapitalism Socialism: Us Economic SystemHananti AhhadiyahNo ratings yet

- Capitalism Is A Very Flawed System But The Others Are So Much WorseDocument4 pagesCapitalism Is A Very Flawed System But The Others Are So Much WorseNiharika Satyadev JaiswalNo ratings yet

- Assessment Activity Macroeconomics Quiz 1Document3 pagesAssessment Activity Macroeconomics Quiz 1jumel delunaNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of EconomicsDocument4 pagesFundamentals of EconomicsFastRider SubnaniNo ratings yet

- Philippine Blooming Mills Employees Organization vs. Philippine Blooming Mills Co., Inc.Document52 pagesPhilippine Blooming Mills Employees Organization vs. Philippine Blooming Mills Co., Inc.Elmira Joyce PaugNo ratings yet

- Viral MarketingDocument58 pagesViral Marketingakhilesh1818100% (1)

- CH 04 Demand and SupplyDocument16 pagesCH 04 Demand and SupplyAnkitNo ratings yet

- Cesar Daly Paris and The Emergence of Modern Urban PlanningDocument23 pagesCesar Daly Paris and The Emergence of Modern Urban Planningweareyoung5833No ratings yet

- Paul Pignataro Leveraged BuyoutsDocument11 pagesPaul Pignataro Leveraged Buyoutspriyanshu14No ratings yet

- ECON 201 SyllabusDocument4 pagesECON 201 SyllabusAnh NguyenNo ratings yet

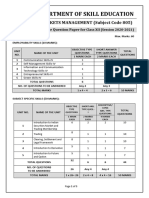

- 805 Financial Market Management SQPDocument5 pages805 Financial Market Management SQPajaydohre893No ratings yet

- BootcampX Day 5Document67 pagesBootcampX Day 5Vivek LasunaNo ratings yet

- Amazon Indias Apni Dukaan Branding StrategyDocument8 pagesAmazon Indias Apni Dukaan Branding Strategyvansaj pandeyNo ratings yet

- Nek KeilDocument40 pagesNek Keilnganemm0612No ratings yet

- Industry 4.0-Transition To New Economic Reality: Stella S. Feshina, Oksana V. Konovalova and Nikolai G. SinyavskyDocument10 pagesIndustry 4.0-Transition To New Economic Reality: Stella S. Feshina, Oksana V. Konovalova and Nikolai G. SinyavskyVinoth HariNo ratings yet

- Types of Bond Liabilities - CompletedDocument5 pagesTypes of Bond Liabilities - CompletedKing T. AnimeNo ratings yet

- Situation & Environmental AnalysisDocument18 pagesSituation & Environmental Analysisarnaarna100% (1)

- Collateralized Loan Obligations (Clos) - Guggenheim PartnersDocument4 pagesCollateralized Loan Obligations (Clos) - Guggenheim PartnersAbdulrahman Al HuribyNo ratings yet

- Adjusting Entries:: BU127 Final NotesDocument26 pagesAdjusting Entries:: BU127 Final NotesdvNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Analysis Redux-3Document25 pagesFundamental Analysis Redux-3Mantu KumarNo ratings yet

- Columbia Sports WearDocument13 pagesColumbia Sports WearZack NduatiNo ratings yet

- Tariff Analysis, Partial EquilibriumDocument35 pagesTariff Analysis, Partial EquilibriumtaimoorNo ratings yet

- Project / Case Study Format (Research Report) : (Word Limit: 4,000+ Words)Document3 pagesProject / Case Study Format (Research Report) : (Word Limit: 4,000+ Words)Hafsa ShahNo ratings yet

- CVP AnalysisDocument16 pagesCVP AnalysisPushkar SharmaNo ratings yet

- Excercises MA 2023 1Document4 pagesExcercises MA 2023 1fin.minhtringuyenNo ratings yet

- Unit Code: BM533 Unit Title: Contemporary Business EconomicsDocument17 pagesUnit Code: BM533 Unit Title: Contemporary Business EconomicsLucifer 3013100% (1)

- FF l1 InretailDocument28 pagesFF l1 Inretailjmas204No ratings yet

- Basel AccordDocument11 pagesBasel AccordleojosephkiNo ratings yet

- A Study On Skill Development Initiative by Government of India With Reference To Dadra & Nagar HaveliDocument8 pagesA Study On Skill Development Initiative by Government of India With Reference To Dadra & Nagar HaveliAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- 11 Organizational StructureDocument115 pages11 Organizational Structureabhishek ibsar50% (2)

- Citibank: Launching The Credit Card in Asia Pacific (A)Document11 pagesCitibank: Launching The Credit Card in Asia Pacific (A)vijay kumarNo ratings yet