Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Amity Patterson

Amity Patterson

Uploaded by

Mahnoor ImranOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Amity Patterson

Amity Patterson

Uploaded by

Mahnoor ImranCopyright:

Available Formats

The Bankruptcy of Homoerotic Amity in Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice

Author(s): Steve Patterson

Source: Shakespeare Quarterly , Spring, 1999, Vol. 50, No. 1 (Spring, 1999), pp. 9-32

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2902109

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2902109?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Shakespeare Quarterly

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Bankruptcy of Homoerotic Amity in

Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice

STEVE PATTERSON

R ATHER FAMOUSLY, THE MERCHANT OF VEXICE OPENS WITH a pitiful Antonio

bemoaning his outcast state but unable to articulate just what has caused his

disenchantment. His very identity seems to be at stake as he complains, "I have

much ado to know myself" (1.1.7).1 Indeed, his worries over how much and in

what terms he matters in Venice may be much ado about nothing-about the pos-

sibility of his being nothing. Antonio speaks as a man at odds with the changing

values of his culture, someone whose role as virtuous friend has no serious regis-

ter with his fellow men but whose identity as merchant has premium value. He

has entered the stage in dialogue with himself as much as with his two compan-

ions, and as the scene progresses, Antonio is repeatedly unable to connect with

those he encounters. His melancholy is diagnosed immediately as an effect of

money woes by Salerio and Solanio, who swoon over their histrionic visions of

how the course of a rich merchant's humors is surely tied to the swell of his

argosies' sails. In keeping with this stress on Venice as a world in which even feel-

ings are valued mainly in commercial terms, Gratiano intimates that Antonio uses

his public displays of moodiness to "fish . .. with this melancholy bait / For this

fool gudgeon, this opinion" (11. 101-2). In short, his strange affect must be a cal-

culated bid to gain attention-as if melancholy is best understood as an entrepre-

neurial gambit. Small wonder that Antonio protests the theory that his sighing

must indicate some variety of love, since even love is a cheap commodity in

Venice, something one puts on like a "sober habit" or the "boldest suit of mirth"

(2.2.181, 193). The passionate Antonio can hardly fathom, let alone endorse, such

a devaluation of his desires.

Despite Antonio's protestations, literary critics have debated the object and

nature of his love. For some time it was held that Antonio has no particular ref-

erent in mind at all, that the subject is raised mainly as a dramatic device to cue

the theme of romance or that it stands as "a relic of an earlier version of the

play."2 But this analysis has been superseded by the modern cliche (and, some

insist, the anachronism) of Antonio as a lovelorn homosexual vainly in pursuit

of the obviously heterosexual Bassanio. Certainly there is enough textual ambi-

guity to lend validity to almost any diagnosis of Antonio's melancholy, and the

present understandings of the ways that same- and cross-sex passions mattered in

A longer version of this essay was presented in February 1998 to a session of a year-long colloqui-

um entitled "Sexuality, Subjectivity, and Representation in Early Modern Literature," chaired by Susan

Zimmerman at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC. I am grateful to the colloquium

members, especially Susan Zimmerman, Jeff Masten, and Michael Neill. Gail Kern Paster and anony-

mous readers at Shakespeare Quarterly also offered valuable criticism and suggestions.

1 Quotations from The Merchant of Venice follow John Russell Brown's edition for the Arden

Shakespeare (London: Methuen, 1955).

2 Brown, ed., 4n.

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

10 SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY

early modern England are still confused enough to allow for a

ing of Antonio as a prototype of the lovesick homosexual. Alan

to Read The Merchant of Venice Without Being Heterosexist" a

pretation as it considers the play's resonance-and its correctiv

ern gay audience.3

It may be that the current confusion about eroticism and

Renaissance England does not mean that there were no early m

structures that incorporated and even valued homosexual a

argue that Antonio's love is a frustrated sexual desire for Bass

that his passionate love falls into an early modern tradition of

ship, or amity. Amity represented friendship as an identity p

value of same-sex love which codified passionate behaviors

tropes, while now perhaps somewhat strange or ambiguous, w

the play's production topical enough for both depiction and

popular formats. Central to The Merchant of Venice is a dramati

of male friendship in a radically shifting mercantile economy

seems better regulated by a social structure based on marital a

sexual reproduction. The play's uncanny resonance comes from

ipates modern romantic ideals by realigning the value and nat

literary figures: the male lover and his beloved, the female m

the social outcast.

Friendship themes were so often the subject of poetry and prose during the last

decade of the sixteenth century that it would not have taken an audience long to

recognize Antonio as the prototype of the passionate friend. The tradition he rep-

resents is exemplified by Sir Thomas Elyot's story of Titus and Gysippus in his

Boke afamed the Governour (1531), a redaction of the friendship narrative which is

remarkable for its foregrounding of the homoeroticism implicit between insepara-

ble male companions. Elyot revised the tale, familiar from a number of sources,

especially Boccaccio's Decameron, in a way that emphasized men's intimate prox-

imity. His Titus and Gysippus enjoy a "perfect amity" or "incomparable friend-

ship," as the tradition would have it, but they are further represented as physical-

ly passionate and amorously drawn to one another. In what might be considered

an erotics of amity, the men are described as "embrac[ing] . . . and sweetly

kiss[ing]" one another, and crying as if their bodies "should be dissolved and

3 See Alan Sinfield, "How to Read iThe Merchant of Venice Without Being Heterosexist" in Alternative

Shakespeares 2, Terence Hawkes, ed. (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), 122-39. Many essays

have dealt with Antonio's homosexuality. In the main, they tend to treat the possibility as secondary

to more pressing issues, as Catherine Belsey does when she writes, "We can, of course, reduce the

metaphysical burden of Antonio's apparently unmotivated melancholy to disappointed homoerotic

desire" ("Love in Venice," Shakespeare Szuvey 44 [1992]: 41-53, esp. 49). Others contend with the prob-

lem of a homosexual in a heterosexual society. W Thomas MacCary, for example, sees the "pathetic"

Antonio as "arrested" in "primary narcissism" and sadly "looking for that archaic image of himself"

(Frends and Lovers: The Phenonenology of Desire in Shakespearean Comedy [New York: Columbia UP, 1985],

168). See also Lawrence Danson, "'The Catastrophe Is a Nuptial': The Space of Masculine Desire in

Othello, Cymbeline, and The Winter's lale," SS 46 (1994): 69-79; Keith Geary, "The Nature of Portia's

Victory: Turning to Men in 'The Merchant of Venice'," SS 37 (1984): 55-68; Lawrence Normand,

"Reading the body in The Me-rchant of Venice," extual Practice 5:1 (1991): 55-73; Seymour Kleinberg, "The

Merchant of Venice: The Homosexual as Anti-Semite in Nascent Capitalism" in Literary Visions of

Homosexuality, Stuart Kellogg, ed. (New York: Haworth Press, 1983), 113-26; and Joseph Pequigney,

"The Two Antonios and Same-Sex Love in Twelfth lNight and The Merchant of Venice;, English Literaiy

Renaissance 22 (1992): 201-21.

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOMOEROTIC AMITY IN SHAKESPEARE'S MERCHANT OF VENICE 11

relented into salt drops"; they risk their lives for one another, swoon when par

ed, publicly proclaim their love, and make hyperbolic vows of eternal devotion.

Although Gysippus is betrothed in order to "increase his lineage and progeny,"

Elyot emphasizes that he had "his heart already wedded to his friend" and that

the two men enjoyed a "fervent and entire love."4 The icon of embracing lovers

depicted such bonding as ethically sound (these model lovers were hardly shame

ful reprobates) and as a boon to the commonwealth.5 The depth of the lovers' pa

sions served the economic and social well-being of their kingdoms.

Amity acknowledged eroticism's power to ensure loyal service in men who

economic and social bonds would otherwise be open to question. In a Tudor court

where "new men" lacked the blood and property ties to one another characteris-

tic of feudalism, and in a social world where men were as available to same- as t

cross-sex attractions, a representation of male lovers compatible with heroic ma

culinity and good citizenship grasped the imagination with rhetorical force. Amit

did not avoid the implication that deep friendships might have an erotic compo

nent but constructed same-sex desire in ways that made it commensurate with

civic conduct and aristocratic ideals.6 Together, loving friends embodied a n

kind of man, as evident in the master trope "one soul in bodies twain." An

indeed, over the ensuing decades the credibility of such an ideal figure was take

up by a range of writers and playwrights interested in the ramifications of the th

ory and practices of devoted gentlemen lovers.7

4 Sir Thomas Elyot, "The wonderful history of Titus and Gisippus, whereby is fully declared t

figure of perfect amity" in Tfie Book nzamed 7i'e Governor, ed. S. E. Lehmberg, (London:J. M. Dent a

Sons; New York: E. P. Dutton and Co., 1962), 136-51, esp. 136, 145, 142, 139, 137, and 138. (M

own essay uses the more common spelling Gysippus.) One of the many changes Elyot makes in the tal

as he knew it from Boccaccio was to soften the female character, eliminating her protests against bei

"gifted" to Titus by her betrothed. Nor is she even aware of the plan, as she is in Boccaccio's versi

Elyot's decision to make Sophronia ignorant and docile fuels the fantasy that amity can accommod

marriage in a way that ensures social harmony. The men's close physical resemblance is also add

and emphasized, and the length of their friendship is extended in number of years. Elyot revises

tale to exalt "perfect amity," not conjugal or romantic love. See Clement Tyson Goode, "Sir Thom

Elyot's Titus and Gysijppus Modern Language Notes 37 (1922): 1-11.

5 Ethics is used here in a sense commensurate with Elyot's views on virtuous male conduct; that

educable behavior that promotes ideal civic and social relationships among men in traffic with o

another. Elyot was not, of course, envisioning, let alone advocating, homosexual sodomy. His eth

allowed that love between noble-minded men could be generative and conservative if properly act

out, and his concept of a heroic same-sex love set it apart from the degradations of sodomy.

6 This argument for the erotic intimacies of friendship is especially indebted to the work of Miche

Foucault and Alan Bray. Foucault speculates, for example, on friendship as "a social relation with

which people had ... a certain kind of choice (limited of course), as well as very intense emotion

relations.... You can find from the 16th Century on, texts that explicitly criticize friendship as some

thing dangerous" ("An Interview: Sex, Power, and the Politics of Identity," interview by Bob Gallaghe

and Alexander Wilson, The Advocate [7 August 1984]: 26-30 and 58, esp. 30). See also "Homosexuali

and the Signs of Male Friendship in Elizabethan England" in Queering the Renaissance, Jonath

Goldberg, ed. (Durham, NC, and London: Duke UP, 1994), 40-61, where Bray argues that th

sodomite as shadow figure to the masculine friend helps to explain the credibility of such criticism.

other works that take up the question of homoeroticism in male friendships, see Jeffrey Masten, Text

intercourse: Collaboration, authorship, and sexualities in Renaissance dratm (Cambridge and New York

Cambridge UP, 1997); Mario DiGangi, lThe homoer-otics of early modert dsrama (Cambridge and New Yo

Cambridge UP, 1997); and Bruce R. Smith, Homosexual Desire in S/zakespeae 's England: A Cultural Poeti

(Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1991).

7 The emphasis on a construct of masculinity that emphasized proximity and intimate touch-a

opposed to distance and the remote gaze-is part of a larger project that includes this essay. For a

cussion of the sense of touch as traditionally associated with ideological disruption and homosexuality

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

12 SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY

Until recently, the only thorough study of the friendship g

Mills's One Soul in Bodies Twain, but there the literature of ami

ations on a plot device traced to its classical origins.8 Mills esc

the friends as sexually passionate and thereby bolsters the mo

Renaissance male friendship was a rather baroque form of plat

Mills concludes, moreover, that amity dies out as a genre in th

century simply because its literary possibilities were exhau

view of male friendship is sustained in many feminist treatme

of an ongoing debate between marriage and friendship. A

bonding stage both prior and inferior to a mature marriage o

marriage or maintain bachelorhood becomes symptomatic

problem peculiar to unevolved males: the narrative progress, s

ing a psychic and historical telos, is toward the comic trope o

marriage. Even when a sexual component in friendship is allow

the case that homosexuality is seen as an immature or neurotic

or as an inherently narcissistic desire.9 But the friend in the t

neither sick nor lonesome. His virtue and integrity come from

for his companion, and it is only gradually that this love is se

ism or at odds with marriage. For Elyot-or, to quickly cite se

vision, for Richard Edwards in his tragicomedy Damon and Pith

perhaps, for Shakespeare in his early friendship play The Two G

(1594)-a social system based on amorous male friendships h

can accommodate marriage and even settle disputes over fortu

property.10 The closing line of Two Gentlemen, as the two frie

appear to settle under one roof, succinctly captures the ideali

feast, one house, one mutual happiness."

When Shakespeare writes Two Gentlemen, however, this hap

seems remote, perhaps impossible, as if such accommodations

of fantasy. Janet Adelman has noted how false the play's "ma

the problems the play sets up between marriage and friendship

away."11 Similarly, in her introduction to The Two Gentlemen

see Sander L. Gilman, Sexuality: An Illustrated History (New York: John Wiley

passim. The coupling of the transcendent and the physical was not unique to

cusses various efforts to reconcile the erotic and the spiritual; see iThe Natu

Romantic, 2d ed., 3 vols. (Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1984), 10-15

versive or "pornographic" tradition of highlighting the eroticism in Renaissan

transcendence, as well as efforts by writers such as Pietro Aretino to represen

window to the soul; see Lynn Hunt, ed., Thie Invention of Ponzog7-aphy: Obscenity an

1500-1800 (New York: Zone Books, 1993).

8 See Laurens J. Mills, One Soul in Bodies Twuain: Friendship in Tudor Lite

(Bloomington, IN: The Principia Press, 1937).

9 Coppelia Kahn asserts that "same sex friendships, in Shakespeare (as in th

chronologically and psychologically prior to marriage" ("The Cuckoo's N

Cuckoldry in The Merchant of Venice" in Shiakespeare "Rough Magic": Renaissanc

Barber, Peter Erickson and Coppelia Kahn, eds. [Newark: U of Delaware P,

In the same volume, see alsoJanet Adelman, "Male Bonding in Shakespeare'

10 John Lyly's Euphues: iThe Anatomy of Wit (1578) might be include

Philautus and Euphues, part with their friendship severed, and neither man

tale may be read as cautionary, warning against true friends falling prey

self-interest.

11 Adelman, 79.

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOMOEROTIC AMITY IN SHAKESPEARE'S MERCHANT OF VENICE 13

Howard observes "the strain under which Shakespeare labored in trying to join

tale of heroic male friendship to a tale of romantic love between men an

women."12 Traditionally, of course, tales of amity were comedies; sudden, happ

denouements were prime characteristics of the genre. Elyot's Titus fears,

example, that his desire for Gysippus's betrothed will corrupt their friendship,

Gysippus tells him that amity incorporates the "power of Venus." Indeed, it is

Gysippus's kin, unforgiving patriarchs of contract marriage, who represent th

blocking agents to this loving friendship, though finally "the noise of rejoicin

hearts fill[s] all the court."13 Even the duped Sophronia, conveniently silent an

acquiescent, settles into marriage and produces children with Titus under

aegis of amity. In Two Gentlemen, however, the path to betrothal and marriage

entailed such base treatment of the female that comic closure seems compromise

The familiar bed-trick in Elyot's tale becomes rather more serious: an audie

must overlook Proteus's threat to rape Silvia. Tensions that Elyot downplayed o

elided begin to resonate in a way that makes the passionate conduct between tw

gentlemen seem, perhaps for the first time, costly.

These tensions do not represent the emergence of a natural incompatibili

between the two kinds of love. Rather, the play's problems of closure may ind

cate that amity as a utopian narrative can no longer contain its inherent contr

dictions. The theater, its market conditions financially and artistically depende

on women and other consumers varying in social status, could not bank on sell

ing stories that represented the uncontested interests of a select few. To make

Silvia quiet and compliant despite her poor treatment may be true to form, bu

her narrow escape from abuse also challenges amity's ameliorating powe

Howard concludes her analysis by speculating that the primacy of male friend-

ship with which the play closes has seemed strange since the eighteenth centur

mainly because heterosexual romance has since enjoyed an ascendancy over

other forms of bonding. But never before were early modern consumers of ami

tales asked to witness the female's cooperation as a condition of brute force or

muted protests.14 In short, the strains and pressures apparent in Two Gentlem

mark a faultline in the gentle practices of amity.

7he Merchant of Venice comes across as a comedy even more deeply skeptical th

Two Gentlemen of the promises and prices of amity. Marriage and amity are squa

ly at odds because the play questions the possibility of a homoerotic bonding t

produces exemplary conduct. As Coppelia Kahn observes, "Merchant... is p

haps the first play in which Shakespeare avoids [a] kind of magical solution" an

turns his "attention to the conflict between the two kinds of bonds"-amity an

marriage.15 It also tests the tenets of loving friendship between men of differe

12 In 7he Norton Shakespeare, ed. Stephen Greenblatt et al. (New York and London: W. W. Norton

Co., 1997), 77-83, esp. 83.

13 Elyot, 140 and 149.

14 Sylvia is spared the rape. Shakespeare compounds the troubling moment with an allusion to Ovi

tale of Philomela, whose rape transforms her into a doleful nightingale who can, at least, endles

broadcast her plight in song. AsJean Howard further observes, Sylvia is also denied this Ovidian com

plaint. Still, the oblique citation might prompt an audience to ask, at least momentarily, about the de

of complicity a tale of amity requires for its idealism to work. Even the context of the allusion-rais

as Valentine laments that he can "sit alone ... / And to the nightingale's complaining notes / Tune m

distresses and record my woes" (5.4.4-6)-embarrasses amity. The bird's song, traditionally decode

Philomela's lament, is summoned to serenade Valentine's own sadness (Greenblatt, ed., 82).

15 Kahn, 105.

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

14 SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY

social status-a merchant and a gentleman. Merchant raises pro

about virtue, rank, wealth, gender, and desire which earlier f

downplayed or idealized. The play wonders whose interests are

of a world governed by the bonds of amity and how practical

plex social and economic questions such a system would b

Merchant takes to task the ideals of homoerotic male friendship

doubts about the ability of romance and marriage to offer an

ments to society or to be any more inclusive. What are the lim

erotic love, the play asks? Might a wealthy merchant become

friend? What if the betrothed female were given a voice? What

might a marriage-based economy have over one grounded

friendships?

Such questions are raised as the play dramatizes the travails of the ideal friend

in a society that is re-evaluating its definitions of love and its virtues-a shift so dis-

ruptive that Antonio as amorous lover seems sadly outmoded, himself a kind of

anachronism. Elyot's Gysippus had been outcast, too, when he defied the will of

his father and a patriarchal system of contract love, and that familiar plot device

makes Shakespeare's Antonio seem at first somewhat conventionally at odds with

the values of Venetian society, in this case a world that commodifies every human

transaction. The merchant's struggle to lionize friendship, however, is decidedly

different from the one patterned by Elyot. In "Titus and Gysippus" contract mar-

riage seems antiquated, in dire need of reform, and amity's power to match like

with like in both homo- and heterosexual relations reinvigorates an ailing body

politic. In Merchant the part Antonio must play in the marketplace of Venice is, as

he himself seems to suspect, "a sad one" (1.1.79), and his faith in the tenets of

amity seems no match for his community's cynical views on the value and pur-

pose of relationships. Lawrence Normand has observed that "Antonio brushes

aside his friends' attempts to put him into words, and offers no discursive version

of himself," but perhaps the merchant's difficulty in articulating his dismay is the

fault of a discourse that has lost its clarity as a medium for expressing and secur-

ing his bond with a gentleman.16

Shakespeare makes his audience aware of Antonio's marginal position not sim-

ply by dramatizing the merchant's opening complaint but also by rearranging the

conventions of friendship tales. Antonio and Bassanio, his "most noble kinsman"

(1.1.57), are strikingly different in both temperament and demeanor; the custom-

ary emphasis in friendship literature on exact similitude is noticeably absent.17

Their longtime association has been characterized by Bassanio's indebtedness to

16 Normand, 60.

17 Mills notes this emphasis on difference, but attributes it to "dramatic contrast" and argues further

that the two men are nonetheless equal in noble character (268). Brown, ed., discusses Bassanio and

Antonio as exemplars of amity and concludes that this alteration from the play's source, n Pecorone,

lends the men an air of nobility and virtue (xiv-xvi). He sees no tensions in the differences in status

of the two friends, nor does he consider an erotic component in amity. Frank Whigham analyzes the

play's "context of social mobility and class conflict," but he tends to see the Christians as singular in

their revisionist use of marital courtship as a vehicle for mystifying aristocratic solidarity and economic

privilege ("Ideology and Class Conduct in Thie Merclant of Venice," Renaissance Drama n.s. 10 [1979]:

93-115, esp. 93). This essay stresses amity's tradition of representing friends as gentlemen, the human-

ist rhetoric of an educable character notwithstanding. Men of lower status are often amazed, perhaps

even moved to emulate amity's code of conduct, but they are never depicted as ideal lovers, let alone

peers to the entitled heroes.

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOMOEROTIC AMITY IN SHAKESPEARE'S MERCHANT OF VENICE 15

Antonio, not by mutual pledges of munificence which friends typically made in

the most public and histrionic ways. Likewise, Antonio's refusal to charge interes

on loans, a long-standing, economically awkward Christian value, may also refer

to amity's now-impractical ethic of a generosity that assumes equality and reci-

procity between men. The merchant who lends gratis in the spirit of friendshi

does not automatically signal a noble character, as does the gentle exemplar of gif

giving in a tale of amity, but seems, instead, foolhardy and impetuous.18

Even the way Shakespeare brings the pair onstage emphasizes their difference

Elyot had observed of his protagonists that "nature wrought in their hearts suc

a mutual affection, that their wills and appetites daily more and more so confe

erated themselves."19 But in Merchant the friends each appear separately and in

obviously incompatible moods. Their conversation lasts only so long as Bassanio's

financial needs are expressed and met. Although he says he owes Antonio "t

most in money and in love" (1.1.131), Bassanio appears mainly interested in expe

diting a solution to his financial bind. In short, there is no unequivocal assertion

of a deeply rooted physical and spiritual kinship that would immediately identi

them as emotional twins and signal a familiar comic-plot trajectory. In Edwards

Damon and Pithias, to illustrate the contrast, the servant Stephano marvels at t

convergence of the friends, who

In mutual friendship at no time have fainted.

But loved so kindly and friendly each other,

As though they were brothers by father and mother.

Pythagoras' learning these two have embraced,

Which both are in virtue so narrowly laced,

That all their whole doings do fall to this issue,

To have no respect but only to virtue:

All one in effect, all one in their going,

All one in their study, all one in their doing.20

Stephano goes on to muse that "they have but one heart between them," thereb

invoking the familiar metaphor of a shared identity between lovers. Antonio an

18 Walter Cohen discusses the politics of early modern England's awkward shift from an opposition

to usurious practices to a capitalist-based economy. Equivocations are apparent in terms such as v

turing, advantage, interest, and iisk; see " The Merchant of Venice and the Possibilities of Historical Criticism

ELH49 (1982): 765-89. Henry Abelove argues that the ascendancy of marriage and reproductive h

erosexuality is homologous with changes in demographics and a rise in capitalist ethics; he conten

however, that the role of "same-sex sexual behaviors" in such developments warrant "separate tre

ment" ("Some Speculations on the History of 'Sexual Intercourse' During the 'Long Eighteen

Century' in England" in Nationalisms and Sexualities, Andrew Parker et al., eds. [London and New Yor

Routledge, 1992], 335-42, esp. 340).

19 Elyot, 136.

20 Richard Edwards, Damon and Pithias in The Dramatic Writings of Richard Edwards, Thomas Norton, and

Thomas Sackville, ed.John S. Farmer, Early English Dramatists (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1966),

1-84, esp. 14. Edwards's depiction of homoerotic friendship seems indebted to Elyot's idealism,

although its dramatic action seems to be a defense of amity as a viable solution to social problems. The

heroes must justify their friendship, which at first appears suspicious to the members of the court,

and distinguish themselves from the self-serving and crass forms of alliance that define male relations

in Dionysius's kingdom. The tropes of Elyot's homoerotic amity-that is, an emphasis on a tran-

scendent physical intimacy-are advanced, and, in the end, the sovereign becomes a third friend to

the gentleman heroes. The question of friendship's compatibility with marriage is not an issue in

Edwards's comedy.

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

16 SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY

Bassanio lack the fusion-troped both physically and metaphysi

heart-that marks a bona fide friendship.

Despite this lack, Antonio plays the standard part of devoted

he evokes comes not from an ostentatious behavior that would

but from the lack of reciprocation between twinned companio

ing to the dictates of amity, Antonio exhibits an exemplary gen

ingness to help fund Bassanio's venture and especially in

Bassanio happy by enabling his courtship of Portia. He is that

rejoiceth at his friend's good fortune than at his own."21 That

his friend's profession of interest in Portia also marks Antonio

of amity. In somewhat nervous terms, Harry Berger Jr.

Antonio's ardor in gift-giving as shamelessly manipulative

hooks of gratitude and obligation deep into the beneficiary's b

Hapgood also sees Antonio as "at once too generous and to

today there remains something strange about a man in pa

another male, such pursuits may have been more ambiguo

Elyot's text, Gysippus gladly sacrifices his betrothed to Titus in

"similitude in all the parts of our body."24 His gift not only cl

their intimacy but, eventually, contributes to social harmony.

It could be argued that there is a classical element of generos

willingness to bargain with Shylock. To an early modern Engl

indeed, to the citizens of Venice-such a venture might be reco

to the ethics of friendship, which would dictate a carefully ch

of charity and sacrifice. Still, at this point in history these sign

already being tallied as strangely extreme (and perhaps the re

and Hapgood bear out this turn in values). Risk-taking is admi

it promises to deliver substantial gains-money, especially, but

ty, too-and Antonio's venture, pledging money and his own fle

who has given nothing in return, does not seem likely to earn

domestic tranquillity. Indeed, Antonio's complaint that he is a

the flock" (4.1.114) may refer to his inability to deliver on the p

love will yoke men of equal character and virtue. The mer

Bassanio is wearisome and circular in a way reminiscent of Sir

exhausted hunter in "Whoso List to Hunt": like that frustr

makes bids for a love quarry he cannot touch. It is as if noli m

Antonio's object of desire as it had the hunter's hind.

That an expectation of love in return for lending would har

dox interpretation of amity's purchasing power is, however, e

tation from Sir Thomas Wilson's Discourse vpon Vsury: "God or

maintenaunce of amitye, and declaration of love, betwix

Likewise Miles Mosse, in his sermon The Arraignment and Convi

es that a "lender may lawfully expect the loue and good will o

21Elyot, 134.

22 Harry BergerJr., "Marriage and Mercifixion in The Merchant of Venice: Th

Shiakespeare Quarterly 32 (1981): 155-62, esp. 161.

23Robert Hapgood, "Portia and The Merchant of Venice: The Gentle Bond," Mo

28 (March 1967): 19-32, esp. 26.

24 Elyot, 139.

25 Sir Thomas Wilson, A Discouise vpon Vsuy (London, 1572), N7r.

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOMOEROTIC AMITY IN SHAKESPEARE'S MERCHANT OF VENICE 17

that hath he iustly deserued by his kindnesse."26 If Antonio presumes that his

generosity will yoke his heart to Bassanio's, it is because humanist images o

amity have taught him to do so. This promise of an intimate equity, delivere

from the court and the pulpit, may account for the popularity of Elyot's tale of

Titus and Gysippus in particular as well as the preoccupation with friendship

themes in Renaissance prose and poetry; at any rate, it helps to make sense o

Antonio's deep yearning. As Mosse preaches, "hee that expecteth loue cannot

bee sayd to expect gaine from lending."27 And so Antonio, who seems to believe

his lending practices will generate love, professes to lend gratis even as he com-

plains about a bewildering sense of loss.

On the other hand, the leveling force of amity also accounts for the apparent

reluctance of the financially-strapped Bassanio to act in kind: friendship may

make both borrower and lender indistinguishable, but in the case of a gentleman

indebted to a merchant, it also risks betraying the men as mere partners in trade-

not fundamentally different from merchant usurers such as Tubal and Shylock in

being bound by the marketplace realities of what Wilson called "private benefit

and oppression:"28 To be sure, when Bassanio visits the marketplace to beg fo

Shylock's backing, he risks ignoble submission; rather comically, amity dimin-

ishes Bassanio's greatness.29 In 1.3, as he urgently bargains with the Jew,

Bassanio's manner of speaking is notably less ornate than the euphuistics he had

used in private dealings with Antonio (nor does it approach the self-aggrandizing

speeches he will deliver in his suit at Belmont). His awkward traffic with a usurer

is an unaccounted price of amity's laws, or, put differently, the gentleman find

himself compromised by the merchant's amiable command to "Go presently

inquire (and so will I) / Where money is" (1.1.183-84). In a bond that should give

rise to an "incomparable friendship" or, as Wilson puts it, would pronounce the

lovers "man and man," Bassanio's status seems tenuous, if not degraded. Once

in Belmont, Bassanio solves Portia's father's riddle by rejecting gold and silver, a

turn that might also describe his attitude toward the mercantile bonds tha

financed his venture:

Therefore thou gaudy gold,

Hard food for Midas, I will none of thee,

Nor none of thee thou pale and common drudge

'Tween man and man....

(3.2.101-4)30

In bargains with men below gentleman status, "perfect amity" produces a rather

disorderly love: the intimacies of friendship compromise and skew hierarchical

26 Miles Mosse, Thie Arraignment and Conviction of Vvrie (London, 1595), M[1]v.

27 Mosse, M[1]v.

28 Wilson, N7'.

29 The stage practice of playing Antonio as an older man in pursuit of a young, handsome aristocrat

may arise from the play's skeptical view of amity's promises of equity, not from any reference to the

men's ages. The elided tradition of an emphasis on twinship creates the sense of an imbalance between

the two men, as does Antonio's unrequited yearning. The modern stereotype of age enamored of inno-

cent youth obfuscates such inequities.

30 Whigham observes that this passage reminds an audience that Bassanio's fortune has been "bred

from Shylock's gold" (101).

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

18 SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY

alliances and are, perhaps, intimacies best forsaken.31 In

Bassanio marry the "lady richly left" (1.1.161), he can a

his rank as lord and governor, even as he is beholding to

amity, not companionate friendship, allows the illusion o

Thus Bassanio's risk-taking to win Portia is announc

Cast as a sort of fairy-tale, this venture in romantic lov

(not the friend) will inevitably win his love, that show

will deliver the coveted goods and preserve the gentl

Bassanio's access to cash in Belmont seems so enchan

Venetian bartering with a merchant and a usurer se

After agreeing to sign a risky contract to finance his f

reassured an anxious Bassanio, "I do expect return /

value of this bond" (1.3.154-55). But when Portia invests

Venice, her confidence dazzles: "Pay [theJew] six thousa

/ Double six thousand, and then treble that.... / You

the petty debt twenty times over" (3.2.298-99, 305-6). H

passes sexual desire and domestic comfort in a way t

ness could not quite effect: "For never shall you lie b

unquiet soul" (11. 304-5). Indeed, the impossible worl

tasies about the regenerative powers of money in

Antonio's marketplace, fraught with the well-known

flats, / . . . dangerous rocks, / . . . [and] roaring water

across as a strange uncharted world. The vexing problem

disregard for his patron once in Belmont may be ex

surance to the eager suitor-"Let it not enter in your m

(2.8.42-43).32 But the memory lapse might better be

privileges of Belmont afford him the luxury of believin

a sign of virtue, not bargains.

This turn to courtship and marriage at the expense of

into the behaviors of a burgeoning system of alliance in

puts it, "the contracting of matrimony will ensure pro

Marriage to an endlessly wealthy lady will allow the ge

ward scene of plying a merchant for loans in a discour

tion of exact similitude. Thus, Bassanio expresses his in

lends Portia's wealth and her house at Belmont the myth

is described as having "sunny locks," with "wondrous v

valu'd / To Cato's daughter" (1.1.169, 163, 165-66).

fleece" at "Colchos' strond," Bassanio, her questing J

31 DiGangi distinguishes between "orderly" and "disorderly" homoe

the value and effects of homoeroticism in early modern England ca

not according to beliefs about its inherent unruliness or theories of its

argument has further support in Masten, in Smith, and in Valerie

Modern England" in Erotic Politics: Desire on the Renaissance stage, Sus

London: Routledge, 1992), 150-69.

32 See Brown, ed., xlvi.

33 Lorna Hutson, The Usurer's Daughter: Male Friendship and Fictions of W

(London and New York: Routledge, 1994), 70-71. Hutson does not co

tor in amity. Similarly, Cohen explains, "Romantic comedy, firmly fo

matizes the adaptation of the nobility to a new social configuration,

cable from a reassertion of dominance" (781).

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOMOEROTIC AMITY IN SHAKESPEARE'S MERCHANT OF VENICE 19

(11. 170, 171, 176).34 From the spectacular reception Portia provides for her

"Hercules" (3.2.60) to Bassanio's Petrarchan complaints of the "happy torment

in romantic love (1. 37), the fiction that this bond is a marriage of true minds

becomes irresistible in the way amity's myth of twinship enjoys.35 It is not that

Antonio's conduct is melodramatic and wanton, while Bassanio's is sensible an

shrewd: these are identical investments, the same excess of risk and passion

Rather, it is the social and economic implications of each man's desires that deter

mine the credibility of his conduct.

Though Bassanio may seem sincere in playing the part of the virtuous suitor

to Portia, Merchant does not allow for a complete mystification of his turn to

romance. Bassanio is that enterprising gentleman whose courtesies and favor

bond him to others only insofar as they promise to secure his wealth and station

Even Bassanio's way of begging Antonio for another loan reveals his faith i

courtly artifice over amorous virtue, at least in terms of the dlan necessary to ply

a merchant for more money. Couching his new request in a simile extended to

credibility's breaking point, he likens Antonio's lending habits to the sport o

archery and then claims that his conceited request for Antonio's steady marks-

manship is made out of "pure innocence" (1.1.145). The needy gentleman is

pledged, or "gag'd" (1. 130), to the merchant because of prodigal spending habits,

and his references to a "swelling port" (1. 124) and a "noble rate" (1. 127) reveal

his concerns with maintaining a lavish lifestyle. Indeed, at the heart of his impas-

sioned plea that Antonio "shoot another arrow" is not love but Bassanio's blun

self-interest-"to get clear of all the debts I owe" (1. 134). In Elyot, Titus's desire

for Sophronia comes with passionate worry that because of his romantic love

"friendship is excluded," a desecration he cannot forebear; and it is only whe

Gysippus reassures Titus that there could be no motive of "lust or sudden

appetite" in matters of amity that Titus agrees to accept amity's gift of marriage.3

Notably, Shakespeare's gentleman suffers no such consideration for Antonio.

When Bassanio turns to romance in Belmont, his motivations are mercenar

enough to mitigate his protestations of transcendent love. Observing the reputa-

tion for "magnificent improvidence" that defamed Elizabethan aristocrats

Katharine E. Maus argues that Bassanio apparently "feels socially obliged to dis-

play himself properly.... [and so] spends huge sums of borrowed money equip

ping himself for his trip to Belmont."37 Similarly, Bassanio worries that his trav-

eling companion, Gratiano, may be unable to "allay with some cold drops of

modesty / [His] skipping spirit" (2.2.177-78), though his friend assures him that

when the time comes, he will "put on a sober habit, . . . / Like one well studied

in a sad ostent / To please his grandam" (11. 187-88). This facility with rhetorica

flourishes and with suiting behavior to the needs of the moment undermines an

audience's ability to completely invest in the romantic fantasy orchestrated

Belmont. And perhaps, too, such self-fashioning allows Portia to opine "There's

something tells me (but it is not love) / I would not lose you" (3.2.4-5).

34 Bassanio's description of Portia has been often observed as a crass devaluation; see, for exampl

Jonathan Bate, Sliakespea-e and Ovid (Oxford and New York: Oxford UP, 1993), 151-53; an

Whigham, 95-96.

35 Adelman observes that one source of male identity in early modern England came from the friend

ship trope of twinship or the mirror self (75-76), but the rhetoric of the companionate marriage was

appropriating that metaphor.

36 Elyot, 139 and 140.

37 Katharine Eisaman Maus in Greenblatt, ed., 1,081-88, esp. 1,084.

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

20 SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY

As noteworthy for its cool remove as for its ent

speaking may belie its sincerity. Antonio, on the o

ed with language that creates an illusion of deep r

common device in persuading an audience of the au

opens, he is marked as a man of complex feeling,

"What stuff [his sadness is] made of" and how it af

self. In a world "deceiv'd with ornament" (1. 74), w

prejudice, mistaken identity, and falsehood prevail,

pretense. His struggle to express his affection may

merchant has Bassanio alone: Antonio momentarily

a tell-tale sign of disruptive feelings, as he stutters t

thing now" (1.1.113).38 In a show of pride that

Antonio is properly insulted by the gentleman's c

[his] love with circumstance" (1. 154). Then, as if to

Antonio speaks in a direct, unadorned manner, not

by courtiers: "but say to me what I should do / Th

be done, / And I am prest unto it: therefore speak

This impassioned resolve is how friends speak on

an impression that what matters most is the welfar

cost of the transaction or some private interest. Wi

Pithias reacts to the news of his lover's condemne

death also!" When later Pithias offers to die for h

witness the depth of the friendship bond "that [he

friend / That loves him better than his own life, an

sacrifices and declarations are conventional signs of

tunities to make public his deep regard. Certainly t

Salerio, who observes that Antonio "only loves the

Unlike Bassanio's passions, however, which seem t

the merchant's feelings vary only in the sense of g

from risking his fortune for Bassanio to offering u

Antonio's grand gestures are further identified

simply platonic love, and they help to account for t

amorous friends and romantic lovers which this p

Antonio's "affection wondrous sensible" for Bassan

self avows, "My purse, my person, my extreme

Bassanio's needs (1.1.138-39). As Seymour Kleinb

purse and person suggests a "sexual longing," a love

give all, including one's body, was a commonplace

tales of romance); to be "one in having and suffer

Like his ships, Antonio's love is cast upon the

"Goodwins" (3.1.4-5). According to the Nort

38 Brown, ed., tries to make sense of the line by providing mis

sible pronoun referents (1 n), but its incoherence may be delibe

rupted speech as a way to show emotional turmoil most fam

acteristic eloquence collapses into disjointed phrasing and ob

the Moor into believing he is a cuckold.

39 Edwards, 31 and 40.

40 Kleinberg, 117.

41 Elyot, 134.

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOMOEROTIC AMITY IN SHAKESPEARE'S MERCHANT OF VENICE 21

'friend."'42 And at least at first, such wrecked passion seems routine: in tales of

amity, friends are separated from one another so that the integrity of their love may

be tested. Lorenzo alludes to such a trial as he compares Portia's fortitude (and her

sexual sacrifice) when faced with her new husband's departure to "god-like amity,

which appears most strongly / In bearing thus the absence of your lord" (3.4.3-4).

Such fortitude cannot be measured by "customary bounty" (1. 9). Moreover, the

separation of lovers traditionally promises a consummation. In tales of amity,

friends inevitably reunite with embraces, kisses, and simultaneous protests of their

passion. Richard Brathwait's image of two men rushing into one another's arms,

univocally declaring their love, "Certus amor morum est" was his emblem for

"Acquaintance" in his 1633 conduct book The English Gentlman, and it is precisely

this familiar moment of ecstatic reunion which tales of amity celebrated.43 Antonio

seems to believe that there must be blocking agents to this love's consummation-

Bassanio's desire for a wife, for example, or, more seriously, a hostile usurer-and

that they must be confronted to test the ameliorating power of amity's love.

Friendships such as those between Titus and Gysippus or Damon and Pithias

allow the lovers to luxuriate in the ecstasy of painful separations and passionate

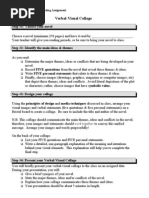

Fig. 1: Detail from the frontispiece of

Richard Brathwait's he Fngih S

Gentlema (London, 1633). From the

Folger Shakespeare Library Collection.

42 Brown, ed., 70n; and Greenblatt, ed., 1,115n.

43 Richard Brathwait, 7Te English Gentleman, 2d ed. (London, 1633). The embracing gentlemen in

Brathwait's conduct book are replaced in the 1641 edition with the icon of a disembodied handshake;

the title is also expanded to e Engish Gentleman and English Gentewoman JeffMasten, whose essay in

Goldberg, ed., includes a reproduction of this image, brought these changes to my attention. In the

1707 broadsheet 7he Woman-Hater's Lamentaion a woodcut of two men embracing serves to defame the

homosexual molly; see Alan Bray, Homosexualiy n Rai England (London: Gay Men's Press,

1982), 83; and Jeff Masten, "My Two Dads: Collaboration and Reproduction in Beaumont and

Fletcher" in Goldberg, ed., 280-309, esp. 281.

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

22 SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY

reunions. Just as undying devotion is proclaimed, as kisses an

what words fail to capture, as emotions burst forth publicly an

the love of friends seems to take on a form outside the mediev

gories of transcendent brotherhood or platonic alliance.44 As it

love only accrues in value with an intensification of the theme

so close as to become one and the same. Indeed, this consolidatio

ates the illusion of a new kind of man, what Elyot called "the o

and Pithias, Pithias explains the effects of amity's love-"when I

am Pithias, methinks I am Damon"-but this strange figure clear

ducated, as when Dionysius inquires, "What callest thou friends

is not this true?"46 Friends are so exceptional in their love that

were transformed into another, which [is] against kind"47-th

phosis of a new being evolved from erotic love. (Idealizations o

sion use this same device in the icon of the hermaphrodite.48

sures in this friendship "against kind"-distinguished from the

monsters against kind-are drawn out through the pattern of se

Eventually, inevitably, the two become one, erotically linked by

Shakespeare borrows this device for producing the illusion o

phosis in friendship by emphasizing Antonio's declarations

faces separation from Bassanio. Antonio behaves as if the gent

loving friend and, later, as if their bond is but temporarily in

ous tyrant ignorant of the ideals of friendship. When first o

seeks, Antonio scoffs at Shylock for mocking the hallmark g

philosophy of exchange: "If thou wilt lend this money, lend i

friends, for when did friendship take / A breed for barren m

(1.3.127-29). Indeed, Shylock makes Antonio agree to his "mer

by defining his offer in the vocabulary of amity, a use of langu

municate love and virtue:

I would be friends with you, and have your love,

Forget the shames that you have stain'd me with,

Supply your present wants, and take no doit

Of usance for my moneys, and you'll not hear me,-

This is kind I offer.

(11. 134-38)

44 Normand argues that in the exalted tones of amity "the sexual is banished, leaving only the spir-

itual" (66), but amity, like romance, advanced the opposite logic: a sexual relationship expressed

through exalted language. It is not unlike the excited verse Romeo andJuliet use to express their pro-

found love and physical passion for one another. See also AllenJ. Frantzen, Before the closet: same-sex love

from Beowulf to Angels in America (Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1998), where Frantzen

argues for homoeroticism in Anglo-Saxon and medieval categories of male bonding.

45 Elyot, 134.

46 Edwards, 41.

47 Edwards, 18.

48 Linda Woodbridge explains that the hermaphrodite in Renaissance poetics represented "the essen-

tial oneness of the sexes," a reference to Plato's idea of the original unity of the self (Women and the

English Renaissance: Literature and the Nature of Womankind, 1540-1620 [Urbana and Chicago: U of Illinois

P, 1984], 140). Although Geary sees Portia's donning of men's clothes as a homoerotic allusion to

Ganymede (57), the invaginated figure might represent the heteroerotic ideal of "one sex," especially

once Portia reveals the wife's value as helpmate in reforming patriarchal law and economic order.

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOMOEROTIC AMITY IN SHAKESPEARE'S MERCHAXT OF VEXICE 23

"I extend this friendship,-" Shylock challenges, "If [Antonio] will take it" (11. 164-65).

In turn, as if he has taken literally Elyot's emphasis on amity as a code of ethics

available for education and reform, Antonio marvels that the reprobate has

become a new man. When Shylock demands his pound of flesh after all, Antonio

speaks as if aJew's heart is beyond the scope of friendship: "You may as well do

any thing most hard / As seek to soften that-than which what's harder?- / His

Jewish heart!" (4.1.78-80). The anticipation of a confrontation with this enemy of

friendship allows Antonio to prepare for his love to take a turn-for him an essen-

tial, even natural turn-toward public recognition and union.

Thus, in his summons to his friend, Antonio implores, "Sweet Bassanio, . . . all

debts are cleared between you and I, ifI might but see you at my death: notwithstanding, use

your pleasure,-ifyour love do not persuade you to come, let not my letter" (3.2.314-20).49

What may seem desperate or effeminate devices to ensnare a man are heroic

actions in the friendship tradition. Antonio wants Bassanio to be present at his

trial as a sign of their love, perhaps in hopes of having his friendship, like the

amity between Elyot's twins, "throughout the city published, extolled, and

magnified."50 To believe that his own society, the mercantile world of Venice,

devalues the erotic possibilities of male friendship nearly to their vanishing point

would not only nullify Antonio's love but turn the merchant himself into a kind

of hapless, friendless "other"-possibly a sodomite but certainly a suspect char-

acter, since outside the bonds of amity and romance, his excessive behavior

would seem useless or reckless. Poised at amity's limits, he does not consider that

its claims on equality and reciprocity are only about nobility and love when they

are also about good manners. Perhaps Portia recognizes in Antonio's letter a call

for a scene of friendship since she not only urges Bassanio to go to his friend but

encourages him to repay the bond twenty times over. Her reference to "an egall

yoke of love" (3.4.13) may be a tribute to the "'greater love"' of biblical heroes,

as Lawrence W. Hyman observes,51 but as a description of amity, its contingen-

cies are apparent:

... for in companions

That do converse and waste the time together,

Whose souls do bear an egall yoke of love,

There must be needs a like proportion

Of lineaments, of manners, and of spirit...

(11. 11-15)

The limiting condition of amity's stress on loving bonds is its clause about the con-

gruence of well-bred bodies.

Perhaps Shylock also understands that amity excludes even as it invites, since

neither the alienJew nor the female possesses that combination of features, breed-

ing, and soul that would allow either to participate fully in amity's myth of twin-

ship. When bargaining with Bassanio in 1.3, Shylock limits the term good to mean

commercially sound, an equivocation that seems less a symptom of stereotypical

greed when read in the context of Elyot's advice "to remember that friendship may

49On the erotic possibilities in the tradition of letter-writing between friends, see Forrest Tyler

Stevens, "Erasmus's 'Tigress': The Language of Friendship" in Goldberg, ed., 124-40.

50 Elyot, 149.

51 Lawrence W. Hyman, "The Rival Lovers in ihe Merchant of Venice," SQ2 1 (1970): 109-16, esp. 112.

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

24 SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY

not be but between good men" who are "engendered by the si

personage, augmented by the conformity of manners and stu

by the long continuance of company."52 In his pound-of-flesh

is a delicious irony that mocks Antonio's belief in the promises

as the terms of the agreement corroborate his desire as physi

pound of "fair flesh, to be cut off and taken / In what part o

pleaseth" him (1.3.146-47). This demand is erotic, as Alan Sinfi

it can be read metaphorically as an attack on the genitals, as ca

erotic also because Shylock chooses to cut the flesh from Anton

heart-in amity, as in romance, the somatic sign of love. This

the Jew to expose the exclusionary rhetoric of amity: the lov

Venetians runs no deeper than their "varnish'd faces" (2.5.33).

Even Bassanio's disregard for the merchant reveals that Ant

of requited love are both too passionate and too expensive. In Sh

Jonathan Bate argues that the details which Shakespeare choos

Bassanio to the classicJason figure bring to mindJason's wors

that is, Jason as "an archetype of male deceit and infidelity."54

notes, foreshadows Bassanio's attempt to win and, later, to tr

Portia. But as a sign of deceit, it also refers back in time to his

faith in friendship practices. The merchant's failure to capita

amity makes his yearning less like the momentary suffering of

and more like some love-sickness, a bona fide Renaissance illnes

tale symptoms-a tremulous body, a distracted mind, an obsess

for another.55 The emphasis on Antonio's love as physical

way of innovating a homoerotic yearning peculiar to a lon

Antonio; indeed, homoerotic desire, as this essay has argue

guished the protagonists of the friendship genre. What is

amorous pursuit of a gentleman seems both strange and u

risked by a merchant.

In Act 4 the trial scene becomes a showcase for exposing and

limits of amity's erotic power. To sever the love of friends is to

body; as Antonio puts it, if the "cut [is] deep enough, / I'll pay

all my heart" (4.1.276-77). Antonio will have a pound of his ow

and thus allow all who witness such spectacular violence to ev

mative powers of male friendship, to judge "Whether Bass

love" (1. 273). In the competitive, mercenary world of Venice,

of being misunderstood as a rather ill-advised way to profit or

risome to Antonio, to be devalued altogether as usurious appet

tion and status. The integrity of male friendship-its virtues o

sacrifice, and intimacy-is so atrophied that only a radical stagi

to secure bonds between men can reinvigorate its appeal. Anto

52 Elyot, 151 and 149.

53 Sinfield, in Hawkes, ed., 125.

54 Bate, 153.

55 Love melancholy, also known as love-sickness or erotomania, was catal

Robert Burton's 7we Anatomy of Melancholy (1655), but love troped as an illne

heritage dating to medieval and even classical times. See D. A. Beecher, "Ant

Heritage of a Medico-Literary Motif in the Theater of the English Renaissance,"

5 (1990): 113-32.

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOMOEROTIC AMITY IN SHAKESPEARE'S MERCHAJVT OF VEXICE 25

sacrifice can be seen as a daring performance on behalf of an exemplary devotion

In the moment of the merchant's epic display of generosity (traditionally both

grand and grotesque), amity will be memorialized as love "wondrous sensible"

(2.8.48). It is Antonio's own nostalgic citation: when his "tale is told" (4.1.272)

the true love between friends will be as inspirational in Venice as it was when

Pithias proclaimed that no one "may ... say but Damon hath a friend." Antonio

implores Bassanio to "live still and write mine epitaph" (1. 118), as if there could

be no more everlasting proof that "Bassanio had ... once a love" than this famil-

iar gesture of sacrificing the body in the name of amity.

As if to travesty Antonio's belief in amity's power to yoke the heart of a mer-

chant to a gentleman's love, Shylock demands the right "To cut the forfeitur

from that bankrupt there!" (1. 122). This attack on amity from an outsider threat-

ens to show how the social realities of Venice betray amity's ideals. However

questionable Bassanio's investment in his role as friend may be, he takes his cue

when an alien endangers male bonds. The gentleman arrives in time to proper-

ly reciprocate the merchant's sacrifice: "The Jew shall have my flesh, blood

bones and all" (1. 112). The sudden turn in Bassanio, from mercenary borrower

to benevolent friend, would seem virtually inexplicable were it not for Portia's

encouragement that he protect his own kind in the face of a foreigner's threat.

Certainly, in the preceding acts, Bassanio has demonstrated that he can play any

part necessary to his welfare. What is evident, too, is that Portia's quibbling with

the law during the trial is not simply a means of nullifying Shylock's financial

threat to Venetian mercantile practices. Portia seems aware of the trial's double

bind: should Shylock expose the limits of amity, the universal values it claims will

be disgraced by a foreigner; but if Antonio manages to redeem amity's appeal

her role as wife will be diminished. As Keith Geary has argued, in rescuing

Antonio from public execution, she saves the merchant and subverts a classic dis-

play of ideal male friendship: "Portia has fastened the homoerotic tendency o

Bassanio's sexuality and the obligations of masculine friendship on to herself."56

There will be no mockery of the Venetian practices of borrowing and partner-

ship, but there will also be no public spectacle of amity as the supreme form of love

It is as if the typically acquiescent or even absent female character from tales of

amity refuses at this point in history to remain silent or vanish. Portia, like each

of the characters in the competitive world of Venice, opts to recast herself on a

stage where everyone plays a part. For her the "will of a living daughter [is] curb'd

by the will of a dead father" (1.2.24-25), curbed by a discursive bind such that a

marriageable daughter "cannot choose ... nor refuse" (11. 25-26). In short, Portia

resists an enforced silence-as if she only pretends to honor a cooperative spirit in

earlier scenes. Portia's bid for power depends on both Antonio and Bassanio play-

ing their parts, but it depends, too, on the failure of amity's climactic scene of tran

scendence. Her clever orchestration of the trial scene-and, later, her neat turn on

the stock bed-trick57-speaks to her shrewdness and her determination. Disguised

as Balthazar, she uses equivocation and illusion not only to save the merchant

56 Geary, 67. See also Karen Newman, "Portia's Ring: Unruly Women and Structures of Exchange

in The Merchant of enice," SQ38 (1987): 19-33.

57 Elyot uses the bed-trick as well. To fulfill his friend's desire for Sophronia, Gysippus allows Titus

to replace him in the marriage bed, where the marriage ring is presented and the "girdle of virginity"

removed (141). Elyot's female accepts the switch without complaint. Thus amity displays not only it

charity but also its capacity to improve an outdated system of contract marriage which has failed t

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

26 SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY

from the usurer but also as a way of liberating herself f

"little body . . . aweary"(1. 1), her voice faint. If the ve

plucked from Antonio's breast for the world to witnes

Portia seems aware that then the "greater glory [w

Within the generous system of amity, marriage will no

worthless (the early tales had no complaint against marr

not shine nearly so brightly as it could if elevated above

brightly as a king," Portia cannily observes, "Until a kin

better way to effect a re-evaluation of marriage and fr

ardent devotee of amity pledge himself to ensuring th

break faith" with the wife (1. 253).58 The friend will en

riage, a minor player in a reconfigured narrative.

Shakespeare takes up two key moments from tales of a

of friendship; the dissemination of amity's ideals-and pre

ly cynical versions. Even though Antonio has behaved a

ing a spectacle of his devotion to Bassanio, there is n

friendship (or of any kind of love for that matter) can b

ened heart. A murderer in Elyot's Titus and Gysippus fa

"the marvellous contention of these two, ... [and is] veh

cover the truth."59 There friendship has the power to im

proclamation of devotion between Shakespeare's two me

the comic presence of the disguised wives, so that the

betrayal than loyalty. These friends seem histrionic an

encouraged her husband to play his part in the trial of f

presence and confidential asides have also allowed a

untroubled scene. The females standing by seem cheate

endlessly generous circle of amity; and as if to undersc

outsider scoffs, "These be the Christian husbands!"

way that exposes the pitfalls in the landscape of amity,

lovers loses the universal appeal it enjoyed in Elyo

endurance of Bassanio's commitment are suspect, and t

ible when the gentleman abandons friendship in the las

turned to its rhetoric in the trial scene.60 The presence o

guise during the proceedings draws out with some forc

consider the role of (male) desire. Shakespeare complicates this motif

from its romantic context, then by having Portia later reclaim its va

when Antonio re-presents the ring as a sign of conjugal amity.

58 For a discussion of Portia's use of her knowledge and wealth to alt

as daughter, see LisaJardine, Readzng Shakespeare Historically (London

58-64. Louis Adrian Montrose analyzes the sexual politics in Elizabeth's

used here to describe Portia-that is, her efforts to "advance or frustr

subjects"; to exploit "[r]elationships of power and dependency, desir

Figurations of Gender and Power in Elizabethan Culture" in Representin

Greenblatt, ed. [Berkeley: U of California P, 1988], 31-64, esp. 45 a

plicates this argument by widening the sweep of court politics to i

opposed to limiting desire to heterosexual and "homosocial" relations); s

Modern Sexualities (Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 1992), 29-61.

59 Elyot, 148.

60 Bassanio resembles the false friends in Edwards's Damon and Pi

accuses his double, Carisophus, of betrayal: "My friendship thou sough

/ As worldly men do, by profit measuring amity" (68).

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOMOEROTIC AMITY IN SHAKESPEARE'S MERCHAJT OF VEXICE 27

of friendship: should amity work its magic after all, both the Jew and the Lad

would be muted, if not ostracized. Understandably, neither witness is impressed b

the performance of masculine love in action.

The supposedly contagious display of devotion between friends does not regis-

ter at all with the citizens of Venice, whose ethic of an eye-for-an-eye strains th

quality of amity's kindness. Here friendship on trial fails to elicit virtue from spe

tators; it seems, quite perversely, to have encouraged a cry for blood revenge, a

decidedly different effect than Elyot's magical scene of conversion. Quite regu-

larly Merchant makes it clear that few of the characters in Venice are genuinel

impressed by anything that does not produce wealth or allow for a profit margin

though their rhetoric speaks to higher interests. Shylock's real crime may not

his claim on a pound of flesh but his habit of turning the platitudes of Venice

against their selfish speakers. He accuses the Christians of taking interest while

calling it thrift, of keeping "many a purchas'd slave" (1. 90), and of professing

humility while practicing revenge. The two characters who believe deeply in va

ues outside the marketplace, Shylock and Antonio, for all their faults and trans

gressions, have no place in Venice and are neither of them understood by its ci

zens. Thus there is something sickening in Merchant's turn on the traditional sce

of conversion. If theJewish heart cannot be inspired by amity's practices, it can

least be subjected to force-ironically by the very merchant who believes in the

power of friendship to improve by example. Even though Shylock's money mus

be willed to his Christian son-in-law and daughter, his penalty will be represen

as "a special deed of gift" (5.1.292). Forced to speak as a new man, the Christian

Jew exits broken and ailing: "I am not well" (4.1.392).

This enforced transformation casts a pall over Act 5 as the married coupl

struggle to collect on the promise of an ecstatic reunion in such a night that seem

to be "the daylight sick" (5.1.124).61 In a final twist of the conversion plot, tra

posing it from a staple of amity to an element of romance, Antonio himself is su

jected to reform. Perhaps awestruck by the mystifying display of the law's powe

the merchant is moved to alter the nature of his own love. The merchant

redefines the role of the friend from lover to grateful guest, an outsider invited

within the circle of marriage. When he vows to play his part in keeping safe the

ring, Antonio agrees to limit the range of its symbolic value to a sign of the amity

in marriage. Indeed, by the end of the play, there is an emphasis (the context of

bawdy jokes and frivolity notwithstanding) on the need for overseeing certain

social practices connected to friendship bonds. The early modern custom of

same-sex bed companions-and a literary sign, too, of male friendship-is alluded

to twice in the play's final moments (11. 284, 305), but its homoerotic valence is

drawn out as a luxury in need of surveillance.

AsJeffMasten has observed, male companions sharing a home, a bed, and even

the same clothes changed from being perceived as a convention in early modern

England to being an oddity, a "'strange Production'."62 In Merchant, the domestic

scene is represented as conjugal in a way that highlights the turn away from the cus-

61 The fifth act begins with Lorenzo andJessica trying to "out-night" one another il a scene that may

be played, certainly, as a light-hearted game between newlyweds (11. 1-23). ButJessica's way of empha-

sizing themes of infidelity in each of Lorenzo's citations can foreshadow the upcoming exposure of

unfaithful husbands and may also recall the betrayals in scenes past.

62 Masten in Goldberg, ed., 301-4. On men as bed companions, see also Bray in Goldberg, ed.,

42-43; and Bray, Homosexuality, 50-51.

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

28 SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY

toms of companionate amity. Life at Belmont, it appears, will

male friendships, most certainly not an open intimacy betwee

status; nor will it include wives who would quietly comply

ments. Essential-and essentializing-choices have been made.

his bed companion not in Antonio but in Balthazar, the you

saved the merchant's life, and the gentleman has learned, furth

is his wife: "Sweet doctor," professes the contrite gentleman t

be my bedfellow" (5.1.284). The bawdy ring jokes suggest

sodomy make same-sex desires resemble infidelity, if not con

butt of these jokes, Gratiano heads off to his marriage bed co

the day come, I should wish it dark / Till I were couching with

(11. 304-5).

These lines, as Coppelia Kahn has observed, "voice [a] homoer

haps, too, they voice a fantasy of social mobility, namely, a cle

as lover and beloved. Such relationships were briefly encourag

when, at the end of 4.1, Antonio succeeded in using the ring

bond, enabled by a doctor of law, between a merchant and a g

ing that exalted amity would be familiar, not radical or disside

ern audience, as when Elyot closes his comedy as an "examp

friendship."64 But Shakespeare's version anticipates the moder

homoerotic desire with secrecy-wishes made in the dark-a

Friendship's claim on the ring seems somewhat underhanded an

fifth act's formal turn toward romantic closure is compromise

tence, it also bears the burden of having foreclosed on a conv

consummation: the coupling of two friends, whose amity will

[a] wife's commandement" (4.1.447). The play ends, furthe

admits (his desires notwithstanding) that he will "fear no other

keeping safe Nerissa's ring" (11. 306-7). In these final, comic m

tasies of male friendship trigger anxiety.

This skewed arrangement-two friends pledging service to a

rective to applications of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick's theory of t

Although Sedgwick did not propose her model as a lens for de

phobia inherent in erotic triangles, the idea of homosociality is

every instance in literature where desire for a female affects m

woman serves mainly as a handy alibi for a potentially embar

desire. But the early representatives of English Renaissance frien

in shame; nor do they invariably deflect same-sex desire onto

protestation of love between friends was public and straightf

this difference helps to explain why modern critics, accustome

al tropes of the clinic and the closet, have debated whether am

homoerotic. Indeed, shame as the necessary condition of th

credibility to the cliche that the erotic language of male frien

strategically ambiguous. Homophobia-in this instance an anxie

intimate proximity with one another-appears to become a sha

triangles as the sixteenth century comes to a close. There is no

63 Kahn, 111.

64 Elyot, 149.

65 See Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (New York:

Columbia UP, 1985), 1-5.

This content downloaded from

110.93.234.14 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 03:57:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOMOEROTIC AMITY IN SHAKESPEARE'S MERCHANT OF VENICE 29

first three acts, and certainly none in the early tales of amity, that an expression

love between friends must yield before some heterosexual imperative. Only at t

end of Merchant do the men experience, much to their bewilderment, a pressure

confess their "true" feelings as a desire for, or an allegiance to, marital fidelity.

As for the trope of well-matched or twinned lovers, Antonio finally mirrors

Shylock, not Bassanio. This irony, a bonding of the merchant with the Jew, is

made apparent in the way friendship's twin motif, significantly absent between

Antonio and Bassanio, yokes the supposedly contrary figures of the usurer and

the friend.66 The play's title might refer to either of the two moneylenders, bot

of whom justify their lending practices by citing a common biblical ancestor, y

each a stranger in the marketplace. Shylock's relationship to money is, lik

Antonio's, not reducible to self-interest, as becomes evident when the Je

bemoans the loss of Leah's priceless ring or when he cries to his judges, "you ta