Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Avowed Happiness As An Overall Assessment of The Quality of Life

Avowed Happiness As An Overall Assessment of The Quality of Life

Uploaded by

Symmetry WOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Avowed Happiness As An Overall Assessment of The Quality of Life

Avowed Happiness As An Overall Assessment of The Quality of Life

Uploaded by

Symmetry WCopyright:

Available Formats

Avowed Happiness as an Overall Assessment of the Quality of Life

Author(s): D. C. Shin and D. M. Johnson

Source: Social Indicators Research , Oct., 1978, Vol. 5, No. 4 (Oct., 1978), pp. 475-492

Published by: Springer

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27521880

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social Indicators

Research

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

D. C. SHIN AND D. M. JOHNSON

AVOWED HAPPINESS AS AN OVERALL ASSESSMENT

OF THE QUALITY OF LIFE

(Received 16 August, 1977)

ABSTRACT. The concept of happiness has been mistakenly identified with feelings of

pleasure in recent studies of quality of life. This paper clarifies the meaning of the

concept 'happiness' and establishes grounds for its proper use in scholarly research. In

addition, an empirical test of four major accounts of happiness derived from a careful

review of philosophical and empirical literature is undertaken to propose a theory of

happiness. The theory suggests that happiness is primarily a product of the positive

assessments of life situations and favorable comparisons of these life situations with

those of others and in the past. The various personal characteristics of an individual

and the resources in his command, such as sex, age and income, influence happiness

mostly through their effects upon the two psychological processess of assessment

and comparison.

Throughout history, many philosophers have argued that man exists in order

to be happy and that the search for happiness is the chief goal of human

action. For example, Aristotle identified happiness as the chief and final good

in his first book of the Ethics and wrote more than nine books inquiring

about the nature of human happiness. Utilitarian philosopher Jeremy

Bentham claimed that government's primary purpose is to ensure the greatest

amount of happiness for the greatest number. The Declaration of Independence

pronounces all men as possessors of an 'unalienable' right to 'the pursuit of

happiness'. There is a general agreement among thoughtful people that

happiness is the final end of human activity.

Happiness, however, is known to be a peculiarly difficult subject to frame

and analyze. Although everyone is sure that happiness is desirable, no one

seems to know exactly what it is or how it can be achieved. Is it the same as

peace of mind, contentment or statisfaction? Is it enjoyment and pleasure or

creative activity? Does happiness emanate from riches, fame or power? These

are age-old philosophical and empirical questions which still need to be ans

wered. The present study represents a systematic attempt to deal with some

of these questions.

Recent years have seen a substantial increase in empirical research into

self-assessments of happiness. Many scholars have examined the individual

Social Indicators Research 5 (1978) 475-492. All Rights Reserved

Copyright ? 1978 by D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht, Holland

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

476 D. C. SHIN AND D. M. JOHNSON

relationships between various demographic, sociological, psychological and

behavioral characteristics and self-assessments of happiness (Allard, 1975;

Alston et al., 1972; Andrews and Withey, 1976; Bradburn and Caplovitz,

1965; Bardburn, 1969; Brenner, 1975; Cameron, 1974; 1975; Campbell

et al., 1976; Easterline, 1973, 1974; Glenn, 1975;Gurin, 1960; Harry, 1976;

Phillips, 1967; Robinson and Shaver, 1969; Spreitzer and Snyder, 1974;

Wilson, 1967). Although their studies have produced valuable information on

the correlates of avowed happiness, they have not developed a systematic

line of research mainly due to the absence of theoretical frameworks. Most of

these empirical works have failed to present systematic accounts of happiness,

because for the most part, they are confined to the individual impact of a

limited number of arbitrarily selected variables upon self-reports of happiness

without considering their mutual interactions. What is known from such

works is little more than that income, youth, education, marriage, social

participation and positive feelings are positively correlated with happiness.

Consequently, the formulation of theory in self-assessments of happiness is

only nascent and requires a broader framework of explanation and sophisticated

methodology. The present inquiry is intended to formulate a broader

explanatory framework; derive researchable hypotheses; and subject them to

empirical testing through multiple-regression analyses. For this purpose,

an attempt will be made to synthesize philosophical accounts of happiness

with the findings derived from previous empirical research.

I. THE NOTION OF HAPPINESS

From the Epicureans to contemporary social scientists, there has been con

siderable confusion about what precisely happiness means. Even in present

English usage, happiness carries quite a variety of meanings and thus

frequently creates a semantic snare (Margolis, 1975, p. 23). To clarify the

meaning of the concept and establish grounds for its proper use in scholarly

research, a conceptual investigation will be attempted of the philosophical

and empirical literature on happiness. In addition, the three main uses of the

term 'happy' will be distinguished here (Thomas, 1968).

The first use of the term refers to a feeling, which is usually of short

duration. When Homer and Herodotus understood happiness to be basically

physical pleasure and when Allard, Campbell and Bradburn thought of it as

an affective state, they were referring to short-term moods of gaiety and

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AVOWED HAPPINESS 477

elation, different from the core meaning of satisfaction. Such feelings of

happiness are often termed euphoria: the presence of pleasure and the

absence of pain. Viewed from this perspective, happiness is a hedonic

concept.

A second use is one in which a person is 'happy with' or 'happy about'

something, and these expressions mean being 'satisfied with' or 'contented

with', and do not at all imply that one has any particular feeling. The word

is used to describe the welfare aspect of life experience, not the hedonic

aspect of human life.1

Thirdly, the term 'happy' is often used evaluatively to make an appraisal

of one's overall quality of experience rather than to make a statement of fact

as in the case of the second use (Benditt, 1974; Cameron, 1975). When a man

says that he is happy, he means that he has a happy life, a life in which all of

his objectives form a harmonious and satisfying whole (Simpson, 1975,

p. 175). When one makes such a judgment in the context of the concept of

happiness, he takes into account various aspects of his condition and circum

stances, as well as how he feels about them. For this reason, philosopher

Austin (1968, p. 52) claims that a person's being happy represents the highest

assessment of his total condition.

Unlike the first two segmented views of happiness, which focus upon

either pleasure, fulfillment or welfare, this third conception of happiness

includes all human needs, desires, interests, tastes and demands, and seeks

to determine whether they constitute a harmonious whole, which Professor

Fletcher (1975, p. 14) characterizes as a sensitive commixture of mind and

feeling (see also Goldstein, 1973). Since mind without emotion, so it is

believed, is impoverished and since emotion without mind is squalid, they

would make a partnership in the form of happiness. Happiness is not

episodic like pleasure, or subject to momentary moods. Feelings of pleasure

and pain can occur both in the context of a happy life and in the context of

an unhappy life. The distinction between feeling happy and being happy

should be considered in systematic accounts of happiness (McCall, 1973,

p. 232).

Yet, this important distinction and the value of happiness as a conceptual

tool for assessing life quality through the eyes of the beholder have been

little appreciated in recent studies of the quality of life (Allard, 1975;

Andrews and Withey, 1976; Campbell et al., 1976). Despite substantial and

consistent evidence contrary to their claims, many well-known scholars have

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

478 D. C. SHIN AND D. M. JOHNSON

identified happiness with short-term moods of gaiety and elation. For

example, Bradburn viewed happiness as a product of positive feelings and the

absence of negative feelings, although his data explain only small portions of

variations in happiness. His study (1969, pp. 63?68) reports that the gamma

values for the association between self-reports of happiness and the balance of

positive and negative affect ranged from 0.33 to 0.51. Similarly, a recent

national sample survey conducted by the University of Michigan (Andrews

and Withey, 1976, p. 85) reveals that the Affect Balance Scale explains only

26 percent of the variance in self-reports on happiness.2 No doubt, one's

perception of pleasure and pain is not identical with his assessment of

happiness. As a recent empirical study by Brenner (1975, p. 330) suggests,

happiness should not be equated with an experience of feeling or affect.

Instead, it should be viewed as a global assessment of a person's quality of life

according to his own chosen criteria.

II. SOURCES OF HAPPINESS

If the search for happiness is considered as the prime force of human action,

the question that matters, then, is of what does happiness consist? Philosophers

and social scientists have constantly examined numerous factors in search for

the determinants of happiness.3 Some people argue that happiness consists of

the possession of a solid estate, while as many others have said that it is

granted only to those who have no attachment to the things of this world.

Power, virtue, love, solitude, friendship, the pleasure of the sense ? each has

been recommended by some, and rejected by others, as constituting true

happiness.

According to von Wright (1963, pp. 92?94), there are at least three well

known accounts of the happy life. He calls the first of these 'Epicurean ideals',

according to which happiness consists in having (as opposed to doing) certain

things that give one passive pleasure. For example, one might get pleasure

from having certain possessions. Happiness for such an individual consists,

then, in getting sufficient pleasure by having enough of these pleasure

producing things. The Lockean idea that property is the foundation and

means of happiness and the Whiggish conception of happiness as possession

of property belong to this materialistic theory of happiness (Schaar, 1970,

p. 10). Such materialistic conceptions are still widely held in the popular

belief that money buys happiness.

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AVOWED HAPPINESS 479

The second kind of ideal of the happy life is, according to von Wright,

found in the writings of the utilitarians, for whom happiness was seen as

dependent upon the satisfaction of desire. Happiness, in such a view, is

essentially contentedness ? equilibrium between needs and wants on the one

hand and satisfaction on the other; the prompt satisfaction of needs produces

happiness, while the persistence of unfulfilled needs causes unhappiness

(Wilson, 1967, p. 302). The happy life for a person would be a life in which

as many as possible of one's needs and desires are met; frustration in

obtaining them, accordingly, would be a main source of unhappiness.

A third category of ideals of the happy life, as revealed in the philosophical

literature, sees happiness neither in passive pleasure as in the possession of

property nor in the satisfaction of desire. The third view, which is found in

Aristotle's concept of eudaimonia, equates happiness with creative activity

(McKean, 1941, pp. 1093?1112). Happiness is thought to come from the

fulfillment of one's capacities by doing what one is keen on. As Simpson

(1975, pp. 172-176) and Schaar (1970, pp. 22-25) argue, happiness is

an achievement brought about by man's inner productiveness, the accom

paniment of all productive activity. Sociologist Phillips (1967) demonstrated

that social participation would increase happiness.

While philosophical accounts search for the main source of happiness in

individuals in terms of their unique needs, interests and capacities, social

scientists take the position that happiness is a concept relative to the

culture in which they function and relative to their personal life history

(Margolis, 1975, p. 23). Unlike moods, which are heavily affected by

immediately prior circumstances, happiness as a person's appraisal of his

'overall' quality of existence takes in broader considerations. Like the

concepts of poverty and wealth, happiness is influenced by past experience

as well as comparisons with others (Crosby, 1976). For example, a recent

14-nation study of happiness reached the conclusion that "relative status is

an important ingredient of happiness" (Easterline, 1974, p. 113).

Considering all these important accounts of happiness, we propose that

happiness consists of the possession of resources; the satisfaction of needs,

wants and desires; participation in self-actualizing activities; and comparisons

with others and past experience. By determining how these four sources

individually and collectively contribute to self-assessment of happiness, the

present inquiry seeks to outline a causal model in skeletal form for further

analysis.

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

480 D. C. SHIN AND D. M. JOHNSON

III. METHODOLOGY

The data for this study were collected in the summer of 1975 as part of a

larger investigation into the quality of life in three middle-size cities in Illinois

Using a random digit-dialing technique, telephone interviews were made with

a sample of 665 male or female heads of households in Decatur, Peor?a and

Springfield. The sample consisted of 263 males, 36 of whom were over 65;

403 were females, 76 of whom were over 65. Six hundred fifteen were

whites, and 50 were blacks. Comparisons of the sample with census data for

the areas indicated that the sample represented the target population with

the exception that both males and blacks were slightly underrepresented.

The questionnaire item used in the present research to measure happiness

has been included in previous surveys conducted by the National Opinion

Research Center and the Survey Research Center at the University of Michigan.

On the assumption that each individual is the best judge of his present

state of happiness, the question was framed to elicit self-evaluation of

happiness in terms of the respondent's own conception of it. As in previous

surveys, the respondents were asked the straightforward question, 'Taking

all things together, how would you say things are these days ? would you say

you are very happy, pretty happy or not too happy?' The wording of

the question enabled the respondents to make the distinction between

being happy and feeling happy and thus make an appraisal of their overall

conditions of existence. As Bradburn (1965, 1969) and Robinson and

Shaver (1969) point out, this self-rating item has the advantage of simplicity,

face validity and, more importantly, the 'stable test-retest reliabilities'. Con

sidering the answer to the question in terms of the subject's best estimate

of happiness, we took such self-reports as the basic dependent variable.

Twenty independent variables were selected from our Quality-of-Life

questionnaire to operationalize the conceptual model presented earlier;

they were grouped into four theoretical clusters composed of (1) resources,

(2) assessments of needs and wants, (3) participation and (4) relative life

standing. The resource cluster included achieved resources (income, educa

tion and home ownership), biological or physiological resources (sex, race

and age) and inter-personal relationships (marital status, the number of

children and the number of people living together). Income was measured by

the amount of family income before taxes, and education was measured by

the highest level of schooling each respondent achieved or completed at the

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AVOWED HAPPINESS 481

time of interview. Home ownership was measured by asking whether or not

the subject owned the place in which he or she lived. Information on sex, race,

age, marital status, the number of children and of people living together in

the same household were collected following standard procedures.

The second cluster 'assessment of needs and wants' encompassed a number

of important areas of human needs whose satisfaction are known to be

essential to human survival and well-being. Subjects were asked to rate their

health, education, housing, standard of living, leisure time, community and

local government from a Likert-type rating scale ranging from very satisfied

to very dissatisfied or from excellent to very poor.

The third cluster focused on participation in communal activities and work

because they represent a variety of opportunities for self-actualization. Com

munal participation was measured by nine items, which were later converted

into index form. Specifically, respondents were asked whether or not they

had (1) written or spoken to a local political or public official about their

community; (2) written to a local newspaper about community matters; (3)

attended a meeting or gathering in which local government or community

policy matters were a major subject for consideration; (4) contributed time

or money in a local campaign; (5) been a candidate for and/or held one

local elective office; (6) been a member of a local political club or organiza

tion; (7) contributed money to social service organizations; (8) worked as

a volunteer with any social service organization; and (9) always voted in local

elections. By summing up responses to these nine items, a nine-point Com

munal Participation Scale (CPS) was constructed. Participation in work was

determined by determining whether or not the subject was working for pay

at the time of interview.

The final theoretical cluster included two separate assessments of life

standing according to relative criteria. The first item was designed to suggest

that respondents compare themselves with the people whom they know in

terms of life enjoyment. In addition, the respondents were requested to judge

whether their financial situation had been getting better, stayed about the

same or had been worse during the past few years.

IV. DATA ANALYSIS

For an extensive exploration of the theoretical model outlined above, the

present research employed a series of powerful statistical techniques. First,

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

482 D. C. SHIN AND D. M. JOHNSON

zero-order correlations (r) were computed to measure the gross relationships

between the twenty independent variables on the one hand and self-assess

ments of happiness on the other. Then, standardized partial regression coef

ficients were calculated to determine the relative effect of each independent

variable in the prediction of happiness when the effects of the remaining

variables were removed. Finally, the relative and absolute predictive power of

each of the four theoretical domains was measured and compared through

multi-mode regression analysis to determine the nature of their interactions

and thereby to develop a predictive model of happiness.

In the statistical analyses, all categorical variables were used as dummy

variables. Males, whites, the married, the employed and those owning their

housing unit were coded as one; females, blacks, the unmarried, the

unemployed and those who rent their place were correspondingly coded as

zero. Missing data on any of the variables included in the present research

were handled by means of listwise deletions (Nie et al., 1975, pp. 347?348).

This reduced the number of cases to 549.

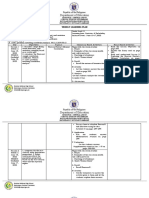

Table I presents Pearson product-moment correlations to determine the

general relationship between the 20 independent variables and the dependent

variable of happiness. As expected, most of the relationships were found

to be statistically significant. Of the four theoretical domains outlined earlier,

the participation cluster fails to significantly relate. The Index of Communal

Participation and work status variables are not significantly correlated with

self-assessments of happiness. More surprisingly, the work status variable

is inversely associated with happiness. These findings appear to raise some

doubt about either the importance of participation to happiness or the

validity and reliability of our measures of self-actualizing work. In any event,

the present evidence does not support the conclusion drawn by sociologist

Phillips (1967), p. 487) that self-reports of happiness is highly related to

participation.

Table I reveals two other negative correlations besides participation in

work. Apparently, being a male or having children seems to work against the

achievement of a happy life. The same table displays a great deal of variations

in the magnitude of association as the values pf the Pearson r's range from

very weak 0.04 to substantial 0.43. While such variables as the perception

of life enjoyment relative to others and satisfaction with the standard of

living explains nearly 15 percent of the variance in avowed happiness, several

other variables such as sex, age and communal participation explain little or

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AVOWED HAPPINESS 483

TABLE I

Ranges, means, standard deviations and zero-order correlations of predictor variables

with happiness

Variable Mean Standard Correlation

deviation with happiness

Resources

Race 0.93 0.26 0.09a

Sex 0.41 0.49 -0.03

Age 3.33 1.65 0.06

Income 3.29 1.50 0.11a

Education 2.38 0.97 0.05

Home ownership 0.75 0.43 0.18a

Marital status 0.69 0.46 0.23 a

Number of children 1.45 0.74 0.04

Number of People living together 2.91 1.46 0.04

Assessment of

Stadard of living 3.36 0.72 0.38a

Leisure time 3.43 0.71 0.34a

Housing 3.54 0.59 0.29a

Health 3.38 0.82 0.21a

Education 4.32 0.68 0.15 a

Community 3.34 0.83 0.17a

Quality of government 1.96 0.96 0.09 a

Participation

Communal activities 2.87 1.94 0.06

Work status 0.64 0.47 -0.06

Comparison of Life Situation

With others 2.45 0.57 0.43 a

With the past 1.36 0.67 0.22

a Product moment correlation coefficient significant at 0.05 level.

nothing in the variance of happiness. By and large, subjective meas

assessments of various needs and perceptions of life standing tend

strongly associated with happiness than various objective indica

resources and participation domains. This is consistent with th

literature on social indicators (Schneider, 1975; Campbell et a

Andrews and Withey, 1976; Inglehart, 1977).

Table II summarizes a stepwise regression analysis that provides a

of the relative effect of each successively-introduced independent

stepwise prediction of happiness; a significance test is performed

sessive increments in explained variance. The betas in the Table are s

partial regression coefficients which tell us the expected change in

tion variable while holding the other independent variables c

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

484 D. C. SHIN AND D. M. JOHNSON

Reflecting the amount of change expected in the dependent variable when

the remaining independent variables are controlled, the betas provide a

measure of the relative contribution of each predictor in accounting for self

assessments of happiness.

TABLE II

Stepwise multiple regression of happiness

Variable Multiple Cumulative R2 Standardized

correlation variance change partial regression

explained (R2) coefficient

Perceived life enjoy

ment relative to

others 0.430 0.185 0.296

0.185

Satisfaction with

0.0790.264

living standard 0.514 0.168

Satisfaction with

leisure time 0.546 0.298 0.034 0.164

Marital status 0.572 0.327 0.029 0.156

Perceived quality

of home 0.581 0.337 0.010 0.095

Perceived financial

0.005

change over time 0.585 0.082

0.343

Sex 0.589 0.347 0.005 0.053

Perceived health 0.592 0.350 0.003 0.073

Income 0.594 0.353 0.003 0.061

Home ownership 0.595 0.354 0.001 0.046

Number of children 0.596 0.356 0.001 0.054

Age 0.597 0.357 0.001 0.061

Community satisfac

tion 0.598 0.358 0.001 0.034

Work status 0.599 0.359 0.001 0.033

Number of people

0.006

living together 0.599 0.359 0.031

Race 0.599 0.359 0.000 0.021

Education 0.599 0.359 0.000 0.024

Perceived quality of

government 0.600 0.360 0.000 0.012

Satisfaction with

education 0.600 0.360 0.000 0.015

Communal participa

tion 0.600 0.360 0.000 0.013

Examination of the magnitude of individual regression coefficients points

out that the perception of life enjoyment relative to other people is the

strongest predictor of happiness. The coefficient of this subjective measure

is more than one and one-half times that of any other variables in the

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AVOWED HAPPINESS 485

equation. The beta value of 0.30 means that for each unit change in the meas

urement of the perceived relative life enjoyment there is more than a quarter

point difference in the happiness scale. Moreover, the positive value of this

coefficient signifies that better comparison with other people enhances self

assessments of happiness. The cumulative variance explained (the square of

multiple regression) in the third column of Table II indicates not only that

this factor is the strongest of all, but also that it alone accounts for the

absolute majority of the explained variance in happiness (19 percent).

Evidence clearly suggests that people do compare with others when they

assess the present status of their happiness and that their comparison with

others is an important determinant of happiness.

Table II also reveals that satisfaction with the standard of living is the

second strongest predictor, explaining a percent of the variations of reported

happiness. This financial satisfaction is followed by leisure time satisfaction,

marital status and housing quality in the order of the relative potency of

predictability. This group of four variables, taken together, explains 15

percent of the variation of happiness, about four percent less than that

accounted for by the single item of the perceived relative life enjoyment.

When all 20 predictors are considered, the equation accounts for an

impressive 36 percent of the variance in the dependent variable of happiness

(multiple correlation = 0.60), but this figure is only two percent higher than

that accounted for by the five predictors which have the highest beta

values. This means that the other twelve independent variables with low beta

values (mostly those bearing on the resources and participation domains)

contribute little or nothing to the prediction of happiness.

While confirming the conclusion derived from the 1973 General Social

Survey that financial satisfaction is an important source of happiness

(Spreitzer and Snyder, 1974; Harry, 1976), the present evidence contradicts

the conclusions drawn from earlier studies that perceived health, socio

economic status and social participation play very prominent roles in creating

happiness. Both work status and communal participation variables, which are

considered as indicators of the participation domain, contribute virtually

nothing to the prediction of reported happiness as the figures in the fourth

column of Table II (R square change) and their beta values suggest. Similarly,

education and income are also found to have little influence on happiness

by explaining 0.3 percent or less of the variations of the dependent variable.

More surprisingly, their beta values are negative and less than 0.08, the value

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

486 D. C. SHIN AND D. M. JOHNSON

which is commonly considered as the minimum level of significance. The fact

that these important components of socio-economic status have trivial

negative beta values must be considered unanticipated, although highly

intriguing. Apparently, income and education have two conflicting effects in

predicting happiness.

While the positive influence of education and income outweighs their

negative influence, the residual effects of them upon reported happiness are

found to be negative when their positive effects are stripped away by statistical

control. Less surprising than these findings on education and income is the

reversal of the original positive relationship between aging and happiness.

Consistent with some previous findings (Spreitzer and Snyder, 1974, p. 458),

regression coefficient (B = ?0.09) indicates that aging in itself detracts from

happiness with adjustments made for all other variables.

The final objective of the present inquiry is to determine the relative

potency of each of the four theoretical domains presented earlier in the

prediction of happiness and thereby to outline a causal model in skeletal

form for further analysis. Changes in the magnitude of the coefficients of

multiple determination (R2 or percent of explained variance) associated with

the four theoretical clusters when they were considered individually and

jointly were used as a means of evaluating the direct contribution of each

cluster to the prediction of the dependent variables and of ascertaining the

interactions among themselves. In this statistical analysis, independent

variables belonging to each cluster were simultaneously entered into the

equations in multiple (as opposed to stepwise) mode. Table III summarizes

the results of a series of such multi-variate analyses by presenting the coef

ficients of multiple determination and standardized betas.

As discussed earlier, our conceptual model of happiness is composed of

the four major domains of sources of happiness derived from philosophical

and empirical accounts of happiness. These domains are the subject's

biological, interpersonal and achieved resources; his assessments of various

individual and communal needs; his self-actualizing activities; and the percep

tion of his life standing relative to other people and his past life experience.

The set of the nine resources variables accounted for 9.0 percent of the

variance in happiness. Seven assessments of individual and communal needs,

taken together, explained as much as 24.4 percent of the variance in the same

happiness measure. Two items of the relative life standing domain explained

20.7 percent of the same measure. By contrast, the composite index of

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

TABLE III

Prediction of happiness by three cluster of variables

Beta coefficients

Resources Assessments Comparions Resources Resourc

only only only and and

assessments compari

Resources

Race 0.04 0.01 0.05

Sex -0.07 -0.04 -0.09

Age 0.03 -0.04 0.01

Income 0.04 -0.05 -0.01

Education 0.05 0.03 -0.04

Home ownership 0.11 0.04 0.10

Marital status 0.22 0.17 0.18

Children -0.09 -0.06 -0.06

Household members - 0.04 0.02 -0.01

Assessments

Standard of living 0.25 0.24

Leisure time 0.22 0.21

Housing 0.10 0.10

Health 0.15 0.13

Education 0.03 0.02

Community 0.05 0.05

Government 0.02 0.01

Comparisons

With others 0.40 0.39

With the past 0.14 0.15

Explained Variance

(adjusted multiple R2 ) 9.0 % 24.4% 20.7% 27.8% 27.2%

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

488 D. C. SHIN AND D. M. JOHNSON

communal activities and work status together explained only 0.8 percent of

the variations in reported happiness.

It is clear that the participation variables are very poor predictors

of the happiness measure, which implies that participation as measured here

is not a main source of happiness. The participation variables are also found

to explain virtually none of the variance in happiness that could not be

alternatively, and more effectively, accounted for by any other domain. Note,

for example, that adding the two participation measures to the set of

assessment measures resulted in no increase in the variance explained; 24.4

percent of the variance explained by the assessment domain remained intact.

This means that the participation variable makes no independent contribution

to what can be predicted by other domains. The weak explanatory power

shown by the figures for the percentage-of-variance shown in Table II and the

absence of their net contribution to the prediction of happiness led us to

withdraw this domain from the prediction model which the present analysis

is proposing.

To determine whether the resource domain has any effect appart from

that mediated by the other three domains, the nine resource measures are

included in further analysis together with the other domains. The results of

this analysis, presented in Table HI, show that addition of the resource

measures makes a small but significant increase over the predictive capacity

shown by the set of assessments or the relative life standing variables. For

example, the set of assessment measures alone account for 24.4 percent of

the variance in happiness, and adding our nine measures of the resource

domain to this information brings the total to 27.8 percent, an increase of

3.4 percent. When the resource variables entered into the equation with the

two measures of the relative life standing, the equation's predictive capacity

rose by 6.5 percent from 20.6 to 27.2. Even when the assessment and

relative life standing domains were considered together, the addition of the

resource variables increased the squared value of multiple regression by 3.6

percent. These findings imply that there are some limited direct effects of the

various resources covered in the present analysis on happiness, beyond those

mediated by the assessments of needs and wants and the perception of

relative life standing. This fact is mirrored by some of the betas for the

resources in the final column of Table III, which remain non trivial.

As reported earlier, the set of nine assessments explained 24.4 percent,

while the set of two relative life standing measures explained 20.7 percent of

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AVOWED HAPPINESS 489

the variance in avowed happiness. If the effects of the perceived life standing

were entirely indirect and mediated by the nine assessments included in the

analysis, the combined explanatory power of both sets would not increase

beyond the 24.4 percent explained by the assessments alone. If, on the other

hand, the effects of the relative life standing on happiness were entirely

independent of these assessments, the total explanatory power of both sets

taken together would be the sum of the explanatory power of the two sets

taken separately, or 45.1 percent. In fact, the sixth column of Table HI

shows that the total explanatory power of the two sets is 32.3 percent; this

suggests the existence of interactions between these two sets of measures,

which results in a mixture of direct and indirect effects of them on self

assessments of happiness, with the preponderance being indirect.

Finally, the relative predictive power of each theoretical domain was

assessed by measuring each domain's direct contribution to the prediction of

happiness. Again, such direct influence was computed by means of the

squared part correlation coefficient, a measure of the difference between

two R2 values (Nie et al., 1975, p. 334). The part coefficient between the

assessment domain and happiness is 0.087, which means that the nine assess

ments add an increment of 8.7 percent to the variation already explained by

the other two domains. The relative life standing and resource domains are

found to raise the potency of prediction by 8.1 percent and 3 percent re

spectively. A comparison of these three squared part coefficients suggests

that the most important source of happiness is the satisfaction of various

human needs followed by favorable comparisons of life situations and then

resources at disposal. This seems to accord with utilitarian accounts of

happiness that happiness consists in an equilibrium between needs and wants

on the one hand and satisfaction on the other (Leiss, 1976).

The findings documented thus far can be integrated to propose a general

model of happiness and this model is presented in specific form in Figure 1.

Happiness is shown as depending primarily on the manner in which a person

perceives and evaluates particular needs of his existence and in which he

compares his life situations. The assessment of his needs and the comparison

of his life situations are, in turn, influenced by characteristics of the

respondent and resources at his command. These resources and characteristics

are viewed as having a direct bearing on happiness, in addition to their

predominant indirect effects through the assessment and comparison of

particular situations. The processes of such assessment and comparison

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

490 D. C. SHIN AND D. M. JOHNSON

Assessments of Needs

Resources - > Happiness

\ Comparison of Life

Si tuations

?tf ) The cross-hatched arrow represents that the streng

relationship is relatively minor compared to others in the

Fig. 1. Model of determinants of happiness.

influence each other in evaluating the present state of happines

the effects of the other process. This is because the degree

required to produce the sense of satisfaction depends on as

which is influenced by the particular standards of comparison

as past experience and comparisons with others and becaus

particular standards for comparison is influenced by the given

satisfaction. Which needs and standards of comparison are

to the assessment of happiness is an empirical question waiting

investigation.

v. CONCLUSION

Social scientists have been for a long time studying the determinants of

happiness, which is known to be the final end of human action. However,

a careful review of the current literature on happiness reveals the absence of a

systematic line of research and this calls for the expansion of the existing

theoretical framework and the application of a sophisticated methodology.

The purpose of this paper involved an attempt to develop a theoretical model

of happiness.

The task of developing a theoretical model has been addressed in the

present work (1) by identifying the proper criteria for the use of the term

'happiness'; (2) by synthesizing major accounts of happiness; and (3) by

testing those accounts with empirical data. On the basis of the findings,

two major conclusions are noteworthy.

While the concept of happiness carries a variety of meanings, many social

scientists have failed to understand the important distinction between those

divergent meanings and the proper criteria for their use. As a result, they have

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AVOWED HAPPINESS 491

mistakenly identified happiness with feelings of pleasure, and thus have mis

understood the value of the term as an important conceptual tool for

assessing the quality of life through the eyes of the beholder. When the term

is used in an evaluative context, it simply refers to being happy and requires

an appraisal of the overall conditions of one's existence.

The results of an empirical test of the four major accounts of happiness

derived from a review of philosophical and theoretical literature imply that

happiness is primarily a product of the positive assessment of life situations

and the favorable comparison of these life situations with those of others and

the past. The various characteristics of an individual and the resources at his

command, such as sex, age and income, influence happiness mostly through

their effects upon the two psychological processes of assessment and com

parison. In addition, they also exert a small but significant amount of direct

influence upon happiness. All in all, our model proposes that happiness is a

concept relative to individuals, their unique needs and resources and to the

culture and environment in which they function as social beings.

Center for the Study of Middle-Size Cities,

Sangamon State University, Springfield, Illinois

NOTES

1 For an illuminating discussion of this subject, see George von Wright (1963).

2 The Affect Balance Scale measures the difference between the scores on the positiv

and negative feeling indices (Bradburn, 1969).

3 For an interesting discussion of the American philosophical literature on the sources

of happiness, see Schaar (1970).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allard, E.: 1975, Dimensions of Welfare in a Comparative Scandinavian Study (University

of Helsinki, Helsinki).

Alston, J., Lowe, R., and Wrigley, A.: 1972, 'Socio-economic correlates of four dimen

sions of self-perceived satisfaction', Human Organization 33, pp. 99-102.

Andrews, F. and Withey, S.: 1976, Social Indicators of Well-Being (Plenum Press, New

York).

Austin, J.: 1968, 'Pleasure and happiness', Philosophy 43, pp. 51?62.

Beneditt, R.: 1974, 'Happiness', Philosophical Studies 25, pp. 1-20.

Bradburn, N.: 1969, The Structure of Psychological Well-Being (Aldine, Chicago).

Bradburn, D. and Capilovitz, D.: 1965, Reports on Happiness (Aldine, Chicago).

Brenner, B.: 1975, 'Quality of affect and self-evaluated happiness', Social Indicators

Research 2, pp. 315?332.

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

492 D. C. SHIN AND D. M. JOHNSON

Cameron, P.: 1975, 'Mood as an indicant of happiness: Age, sex, social class and situa

tion differences', Journal of Gerontology 30, pp. 216-224.

Cameron, P.: 1975, 'Social stereotypes: Three faces of happiness', Psychology Today.

Campbell, A., Converse, P., and Rodgers, W.: 1976, The Quality of American Life

(Russell Sage Foundation, New York).

Crosby, F.: 1976, 'A model of egotistical relative deprivation', Psychological Review 83,

pp. 85-90.

Davis, J.: 1965, Education for Positive Mental Health (Aldine, Chicago).

Easterline, D.: 1973, 'Does money buy happiness?', Public Interest 30, pp. 3-10.

Easterline, D.: 1974, 'Does economic growth improve the human lot?: Some empirical

evidence', in P. David and M. Reder (eds.), Nations and Households in Economic

Growth (Academic Press, New York).

Fletcher, J.: 1975, 'Being happy, being human', The Humanist 35, pp. 13-15.

Glenn, N.: 1975, 'The contribution of marriage to the psychological well-being of males

and females', Journal of Marriage and the Family 37, pp. 394-401.

Goldstein, L.: 1973, 'Happiness: The role of non-Hedonic criteria in its evaluation',

International Studies Quarterly 14, pp. 523-534.

Gurin, G., Veroff, J., and Feld, S.: 1960, Americans View Their Mental Health (Basic

Books, New York).

Harry, J.: 1976, 'Evolving sources of happiness over the life cycle: A structural analysis',

Journal of Marriage and the Family 38, pp. 289-296.

Inglehart, R.: 1977, 'Values, objective needs and subjective satisfaction among western

publics', Comparative Political Studies 10, pp. 429-458.

Leiss, W.: 1976, The Limits to Satisfaction (University of Toronto, Toronto.).

Margolis, J.: 1975, 'Two concepts of happiness', The Humanist 35, pp. 22-23.

McCall, S.: 1975, 'Quality of life', Social Indicators Research 2, pp. 229-248.

McKeon, R.: 1941, The Basic Works of Aristotle (Random House, New York).

Moore, B., Jr.: 1972, Reflection on the Causes of Human Misery and Upon Proposals

to Eliminate Them (Beacon Press, Boston).

Nie, N., et al.: 1975, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (McGraw-Hill, New York).

Phillips, D.: 1967, 'Social participation and happiness', American Journal of Sociology

72, pp. 479-488.

Robinson, J. and Shaver, P.: 1970, Measures of Social Psychological Attitudes (University

of Michican, Ann Arbor).

Rodelfor, B.: 1973, 'Measures of happiness among Manila residents', Phillipine Sociolog

ical Review 21, pp. 229-238.

Schaar, J.: 1970, 'The pursuit of happiness', Virginia Quarterly Review 46, pp. 1-26.

Schneider, M.: 1975, 'The quality of life in large American cities: Objective and subjective

indicators', Social Indicators Research 1, pp. 495-510.

Simpson, R.: 1975, 'Happiness', American Philosophical Quarterly 12, pp. 169-176.

Spreitzer, E. and Snyder, E.: 1974, 'Correlates of life satisfaction among the aged',

Journal of Gerontology 29, pp. 454-458.

Thomas D.: 1968, 'Happiness', Philosophical Quarterly 18, pp. 97-113.

von Wright, G.: 1963, The Varieties of Goodness (Routledge and Kegan Paul, New York).

Wilson, W.: 1967, 'Correlates of happiness', Psychological Bulletin 67, pp. 294-306.

This content downloaded from

210.107.252.61 on Wed, 16 Mar 2022 00:38:25 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Avowed Happinessand Qualityof Life South KoreaDocument20 pagesAvowed Happinessand Qualityof Life South KoreamvroeheNo ratings yet

- Diener, Scollon & Lucas, 2009Document2 pagesDiener, Scollon & Lucas, 2009NovalkNo ratings yet

- 11 Chapter 2Document41 pages11 Chapter 2Pradeep ThawaniNo ratings yet

- Self-Reported Wisdom and HappinessDocument19 pagesSelf-Reported Wisdom and HappinessSuvrata Dahiya PilaniaNo ratings yet

- 2 Orientations To Happiness - Peterson & SeligmanDocument18 pages2 Orientations To Happiness - Peterson & Seligmannbc4meNo ratings yet

- Measuring HappinessDocument22 pagesMeasuring HappinessSree LakshyaNo ratings yet

- Reconsidering Happiness The Costs of Distinguishing Between Hedonics and EudaimoniaDocument16 pagesReconsidering Happiness The Costs of Distinguishing Between Hedonics and EudaimoniaAndres Felipe Arango MontoyaNo ratings yet

- Assignment - Himani PundirDocument18 pagesAssignment - Himani Pundirmindful troubadourNo ratings yet

- Life Satisf and Well-Being StudyDocument22 pagesLife Satisf and Well-Being StudyTălmaciu Bianca100% (1)

- Oishi Westgate Psychrev 2021Document22 pagesOishi Westgate Psychrev 2021Ruxandra PasareNo ratings yet

- La Felicidad: Conceptos, Teorías, Formas de Medición y Discusiones. Happiness: Concepts, Theories, Measurement and DiscussionsDocument20 pagesLa Felicidad: Conceptos, Teorías, Formas de Medición y Discusiones. Happiness: Concepts, Theories, Measurement and DiscussionsKEVIN XAVIER ORTIZ COGOLLONo ratings yet

- Research Essay - CarnesDocument14 pagesResearch Essay - Carnesapi-609519772No ratings yet

- A Dark Side of Happiness? How, When, and Why Happiness Is Not Always GoodDocument12 pagesA Dark Side of Happiness? How, When, and Why Happiness Is Not Always GoodGiancarlo FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Happiness - WikipediaDocument21 pagesHappiness - WikipediaDiana GhiusNo ratings yet

- The Philosophy of Happiness in Life ( - Aristotle's View) 2Document1 pageThe Philosophy of Happiness in Life ( - Aristotle's View) 2BeatrizNo ratings yet

- UC Riverside Previously Published WorksDocument21 pagesUC Riverside Previously Published WorksPriscilla FerrufinoNo ratings yet

- Informative SpeechDocument4 pagesInformative SpeechacqurarosNo ratings yet

- Inquiry ProjectDocument8 pagesInquiry Projectapi-456569037No ratings yet

- Life Satisfaction: A Literature Review: Rituparna Prasoon K R ChaturvediDocument8 pagesLife Satisfaction: A Literature Review: Rituparna Prasoon K R ChaturvediTrejo Hernandez DannaNo ratings yet

- Happiness (1) 1Document9 pagesHappiness (1) 1kaf mosesNo ratings yet

- The Happiness of Individuals and The Collective: Kyoto UniversityDocument17 pagesThe Happiness of Individuals and The Collective: Kyoto UniversityOmriNo ratings yet

- Questions On Happiness Classical Topics, Modern Answers, Blind SpotsDocument21 pagesQuestions On Happiness Classical Topics, Modern Answers, Blind SpotsmehakNo ratings yet

- Aversion To Happiness Across Cultures 2013Document43 pagesAversion To Happiness Across Cultures 2013denscco68No ratings yet

- KD. Eudaimonic Hedonic - FindingsDocument23 pagesKD. Eudaimonic Hedonic - FindingsNoor Arifah MoiderNo ratings yet

- Understanding Happiness - A Vedantic PerspectiveDocument12 pagesUnderstanding Happiness - A Vedantic PerspectiveRiddhima dagaNo ratings yet

- Ryff Et Al. (2021) - Eudaimonic and Hedonic Well-BeingDocument44 pagesRyff Et Al. (2021) - Eudaimonic and Hedonic Well-BeingMarceloNo ratings yet

- 07 - Chapter 1Document23 pages07 - Chapter 1aariz mohammadNo ratings yet

- Wealth and HappinessDocument18 pagesWealth and Happinesslehongtram1228No ratings yet

- Finding Happiness For Privileged and UnderprivilegedDocument15 pagesFinding Happiness For Privileged and UnderprivilegedFaisal KareemNo ratings yet

- Hills 2001Document8 pagesHills 2001poliana stefanNo ratings yet

- Subjective Well BeingDocument8 pagesSubjective Well Being'Personal development program: Personal development books, ebooks and pdfNo ratings yet

- Understanding Happiness 1Document14 pagesUnderstanding Happiness 1leela.verma90No ratings yet

- HappyDocument25 pagesHappyKarla Mae Smiley XdNo ratings yet

- BADOY - SPECIAL Module 2 - Science, Technology, and Society and The Human ConditionDocument8 pagesBADOY - SPECIAL Module 2 - Science, Technology, and Society and The Human ConditionLauitskieNo ratings yet

- 2021 Eng 04Document7 pages2021 Eng 04tssvazNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id1084043Document22 pagesSSRN Id1084043suibragaNo ratings yet

- Well-Being - WikipediaDocument10 pagesWell-Being - WikipediaHeaven2012No ratings yet

- What Is HappinessDocument17 pagesWhat Is Happinessdpv7g9bpb7No ratings yet

- Mock-Defense ScriptDocument5 pagesMock-Defense ScriptJaspher Loís DoyolaNo ratings yet

- VeenhovenDocument29 pagesVeenhovenAlya NamiraNo ratings yet

- True Happiness: The Role of Morality in The Folk Concept of HappinessDocument76 pagesTrue Happiness: The Role of Morality in The Folk Concept of HappinessGina MargasiuNo ratings yet

- Hedonistic ParadoxDocument33 pagesHedonistic ParadoxAlex GomezNo ratings yet

- 2012b FullDocument29 pages2012b FulljoNo ratings yet

- The Aims of Positive Psychology-: Affect, Negative Affect and Life SatisfactionDocument10 pagesThe Aims of Positive Psychology-: Affect, Negative Affect and Life SatisfactionAPOORVA PANDEYNo ratings yet

- In The Pursuit of Happiness: Empirical Answers To Philosophical QuestionsDocument5 pagesIn The Pursuit of Happiness: Empirical Answers To Philosophical QuestionsWindy FransiskaNo ratings yet

- Happiness: Also Known As "Life Satisfaction" and "Subjective Well-Being"Document29 pagesHappiness: Also Known As "Life Satisfaction" and "Subjective Well-Being"brainhub50No ratings yet

- Philosophy EssayDocument6 pagesPhilosophy Essayworldwide handsomeNo ratings yet

- Happiness and Pleasure1: Philosophy and Phenomenological Research May 2001Document29 pagesHappiness and Pleasure1: Philosophy and Phenomenological Research May 2001Rabbul Hussein FahadNo ratings yet

- Hedonic Treadmill 2Document4 pagesHedonic Treadmill 2rossana garciaNo ratings yet

- Is A Happy Life Different From A Meaningful OneDocument6 pagesIs A Happy Life Different From A Meaningful OneⱮʌɾcσsNo ratings yet

- Literature Review - Carnes 1Document5 pagesLiterature Review - Carnes 1api-609519772No ratings yet

- Happinessa and PleasureDocument28 pagesHappinessa and PleasurenitishaNo ratings yet

- A Model of Happiness in The WorkplaceDocument12 pagesA Model of Happiness in The WorkplacenghianguyenNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5 GOOD LIFE REVIEWERDocument3 pagesLesson 5 GOOD LIFE REVIEWERRosemarie BacallanNo ratings yet

- LITREV Jihan Objective Assessment in HappinessDocument10 pagesLITREV Jihan Objective Assessment in Happinessjihan praniNo ratings yet

- Happiness: Definitions Philosophy Culture ReligionDocument25 pagesHappiness: Definitions Philosophy Culture ReligionValdomero TimoteoNo ratings yet

- A Virtuous Cycle The Relationship Betwee PDFDocument24 pagesA Virtuous Cycle The Relationship Betwee PDFaerqwerNo ratings yet

- Topic in Social Indicators Research: The Sociology of HappinessDocument13 pagesTopic in Social Indicators Research: The Sociology of HappinessDavid Gonzalo Guluarte EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Eudonia and HappinessDocument49 pagesEudonia and HappinessFurkan AydinerNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez Et Al.,2022Document7 pagesRodriguez Et Al.,2022taniaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Research Methodology AlDocument6 pagesChapter 3 Research Methodology AlMar Ordanza67% (3)

- Foot Over Bridge PDFDocument6 pagesFoot Over Bridge PDFAnonymous xlTHYk1ODENo ratings yet

- StatisticsAllTopicsDocument315 pagesStatisticsAllTopicsHoda HosnyNo ratings yet

- Research Methods W/ Applied Statistics: Crim 7Document12 pagesResearch Methods W/ Applied Statistics: Crim 7Johnloyd MunozNo ratings yet

- Continuous Probability Distribution, Correlation & RegressionDocument22 pagesContinuous Probability Distribution, Correlation & RegressionDebashishDolonNo ratings yet

- MMPC-5 ImpDocument32 pagesMMPC-5 ImpRajith K100% (1)

- Demand Project 11th CDocument4 pagesDemand Project 11th CT Divya JyothiNo ratings yet

- Chapter II FinalDocument7 pagesChapter II FinalHanelen Villegas DadaNo ratings yet

- Statistics For Business and Economics: Bab 14Document31 pagesStatistics For Business and Economics: Bab 14baloNo ratings yet

- Test of HypothesisDocument200 pagesTest of HypothesisCharlene AngacNo ratings yet

- MBA Syllabus 2022Document209 pagesMBA Syllabus 2022Sachin JamakhandiNo ratings yet

- Confidence Intervals For Pearson's CorrelationDocument6 pagesConfidence Intervals For Pearson's CorrelationscjofyWFawlroa2r06YFVabfbajNo ratings yet

- WLP Statistics Probability Week 8Document3 pagesWLP Statistics Probability Week 8Love RazeNo ratings yet

- CorrelationDocument4 pagesCorrelationRam KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Akash ProjectDocument67 pagesAkash ProjectVishnu PriyanNo ratings yet

- (Cohen) Psych Assessment ReviewerDocument63 pages(Cohen) Psych Assessment Reviewercoby & whiteyNo ratings yet

- Ch.1 Regression, Correlation and Hypothesis TestingDocument1 pageCh.1 Regression, Correlation and Hypothesis TestingAdam SalikNo ratings yet

- Incorporation Effect Size KotrlikwilliamsDocument7 pagesIncorporation Effect Size KotrlikwilliamsSimona CoroiNo ratings yet

- Oup 6Document48 pagesOup 6TAMIZHAN ANo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Working Capital Management in India PDFDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Working Capital Management in India PDFgz8reqdcNo ratings yet

- Service Quality and Customer SatisfactionDocument9 pagesService Quality and Customer Satisfactionsanjana jatooNo ratings yet

- Konaté2015 Article GeneralizedRegressionAndFeed-fDocument10 pagesKonaté2015 Article GeneralizedRegressionAndFeed-fFarooq ArshadNo ratings yet

- Oliveira Et Al (2005)Document6 pagesOliveira Et Al (2005)Ulisses Miguel CorreiaNo ratings yet

- Modeling Temprature Change in A Cup of TeaDocument12 pagesModeling Temprature Change in A Cup of TeammanyaNo ratings yet

- 325-Article Text-912-1-10-20190610 PDFDocument10 pages325-Article Text-912-1-10-20190610 PDFR JNo ratings yet

- IT227 Final Research PapeerDocument49 pagesIT227 Final Research PapeerRichell PuertoNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Iq, Attention and Academic PerformanceDocument36 pagesThe Relationship Between Iq, Attention and Academic PerformanceShiphrah Gold100% (3)

- Chapter OneDocument64 pagesChapter OneGumball 8No ratings yet

- Statistics Notes Covering Fundamental ConceptsDocument2 pagesStatistics Notes Covering Fundamental Conceptsbboit031No ratings yet