Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reading, Writing, and Understanding: Vicki A. Jacobs

Reading, Writing, and Understanding: Vicki A. Jacobs

Uploaded by

Julia Retni AinayaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Cgfns-Profile Entry Instructions PDFDocument11 pagesCgfns-Profile Entry Instructions PDFMosab AfanahNo ratings yet

- Teaching From A Disciplinary Literacy StanceDocument6 pagesTeaching From A Disciplinary Literacy StancesherrymiNo ratings yet

- Fifty Ways to Teach Reading: Fifty Ways to Teach: Tips for ESL/EFL TeachersFrom EverandFifty Ways to Teach Reading: Fifty Ways to Teach: Tips for ESL/EFL TeachersRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Reading and Writing For UnderstandingDocument4 pagesReading and Writing For Understandinglili loti100% (1)

- Riview Jurnal 1Document11 pagesRiview Jurnal 1ripihamdaniNo ratings yet

- Chapter IIDocument15 pagesChapter IIGustari AulyaNo ratings yet

- Reciprocal TeachingDocument18 pagesReciprocal Teachingbluenight99No ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension Intervention StrategiesDocument18 pagesReading Comprehension Intervention Strategiesapi-258330934No ratings yet

- 02 Chapter 2Document39 pages02 Chapter 2jmmagaddatu06No ratings yet

- Definitions of ReadingDocument6 pagesDefinitions of ReadingTiQe 'ansaewa' Sacral HanbieNo ratings yet

- Poetry and Exile Thesis DefenseDocument21 pagesPoetry and Exile Thesis DefenseROMERO, AIRA JOY M.No ratings yet

- Thinking Aloud (Comprehension)Document3 pagesThinking Aloud (Comprehension)dendoinxNo ratings yet

- Content Area ReadingDocument30 pagesContent Area ReadingJohnjohn GalanzaNo ratings yet

- Summary On "A Review On Reading Theories and Its Implication To The Teaching of Reading" by Parlindungan PardedeDocument5 pagesSummary On "A Review On Reading Theories and Its Implication To The Teaching of Reading" by Parlindungan PardedeKayle BorromeoNo ratings yet

- Lesson Planning and Preservice Teachers: A Model For Implementing Research-Based Instructional StrategiesDocument10 pagesLesson Planning and Preservice Teachers: A Model For Implementing Research-Based Instructional StrategiesDeeJey Gaming100% (1)

- MacroSkills ListeningSkillsDocument25 pagesMacroSkills ListeningSkillsCastro, Princess Joy S.No ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument17 pagesChapter IFleur De Liz CredoNo ratings yet

- Teaching EFL ReadingDocument6 pagesTeaching EFL Readingmanalmanila780No ratings yet

- Exploit The Reader's Background KnowledgeDocument4 pagesExploit The Reader's Background KnowledgeismaaNo ratings yet

- Writing AssignmentsDocument6 pagesWriting AssignmentsGe HaxNo ratings yet

- Reading Microskills and Procedure For Training ThemDocument11 pagesReading Microskills and Procedure For Training ThemtrinhquangcoNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Differentiated InstructionDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Differentiated Instructionjzneaqwgf100% (1)

- Cahoon 08Document24 pagesCahoon 08Rya EarlNo ratings yet

- Nunan (1994) Enhancing The Role of The Learner Within The Learning ProcessDocument8 pagesNunan (1994) Enhancing The Role of The Learner Within The Learning ProcessChompNo ratings yet

- Chapter II Scientific ApproachDocument5 pagesChapter II Scientific ApproachtorikNo ratings yet

- PH D Ele Model PaperDocument10 pagesPH D Ele Model PaperMohd ImtiazNo ratings yet

- The Role of Discussion in The Reading ProgramDocument9 pagesThe Role of Discussion in The Reading Programashley_pittman8364No ratings yet

- Dialnet StudentsFirstApproachToReadingComprehension 5476231Document16 pagesDialnet StudentsFirstApproachToReadingComprehension 5476231Kasra VahidiNo ratings yet

- Chapter IiDocument11 pagesChapter IiHani HandayaniNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument5 pagesChapter IAya Tambuli100% (1)

- Disciplinary Literacy A Shift That Makes SenseDocument6 pagesDisciplinary Literacy A Shift That Makes SenseYana ArsyadiNo ratings yet

- 29 2 10125 66918 ElturkiDocument4 pages29 2 10125 66918 ElturkiMehmet YILDIZNo ratings yet

- Developing Reading ActivitiesDocument3 pagesDeveloping Reading ActivitiesbaewonNo ratings yet

- Emg 447 Choice PaperDocument9 pagesEmg 447 Choice Paperapi-699650191No ratings yet

- 12 TEAL Deeper Learning Qs Complete 5 1 0Document5 pages12 TEAL Deeper Learning Qs Complete 5 1 0Jose MendezNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument8 pagesIntroductionELPINIKIMUNo ratings yet

- Reading-Pre While PostDocument18 pagesReading-Pre While PostSiti Hajar Zaid100% (1)

- LtaDocument9 pagesLtasyifaNo ratings yet

- Skripsi FixDocument58 pagesSkripsi Fixresky awaliaNo ratings yet

- Group Work Assignment Methodological ApproachesDocument9 pagesGroup Work Assignment Methodological ApproachesRomina Paola PiñeyroNo ratings yet

- Teaching Reading in A Foreign Language.Document2 pagesTeaching Reading in A Foreign Language.claudio guajardo manzano100% (2)

- Bringing Text Analysis To The Language Classroom: Presented byDocument77 pagesBringing Text Analysis To The Language Classroom: Presented byAdil A BouabdalliNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension Strategies For Elementary Students - Always A Teacher.Document9 pagesReading Comprehension Strategies For Elementary Students - Always A Teacher.Mary ChildNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Bab IIDocument10 pagesLiterature Review Bab IIWindy BesthiaNo ratings yet

- Ii. Frame of TheoriesDocument10 pagesIi. Frame of TheoriesblackarjtelNo ratings yet

- Final Paper ResearchDocument6 pagesFinal Paper ResearchClaudiaNo ratings yet

- Essay 1Document12 pagesEssay 1Laiba TufailNo ratings yet

- Exit Slip JournalDocument8 pagesExit Slip JournalDwi Artawan Gold KnightNo ratings yet

- Writting-Skills-Research-Jesrile-Puda - Docx TheDocument21 pagesWritting-Skills-Research-Jesrile-Puda - Docx Thejesrile pudaNo ratings yet

- The Language Experience Approach and Adult LearnersDocument5 pagesThe Language Experience Approach and Adult LearnersLahandz MejelaNo ratings yet

- Article 2Document6 pagesArticle 2Mohd Zahren ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Final Portfolio 2009Document47 pagesFinal Portfolio 2009claudio guajardo manzano100% (2)

- The Nature of LanguageDocument22 pagesThe Nature of LanguageHolbelMéndezNo ratings yet

- Assignment: Methodological Approaches: General InformationDocument11 pagesAssignment: Methodological Approaches: General InformationAndrea Paz Vallejos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension Levels: Language Skills Phonology Syntax Semantics PragmaticsDocument13 pagesReading Comprehension Levels: Language Skills Phonology Syntax Semantics Pragmaticsnikmatul_ismiNo ratings yet

- Four Activities To Promote Student Engagement With Referencing SkillsDocument12 pagesFour Activities To Promote Student Engagement With Referencing Skillsfabulous annNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3 Literacy PlanningDocument31 pagesAssignment 3 Literacy Planningapi-263403037No ratings yet

- Interacting with Informational Text for Close and Critical ReadingFrom EverandInteracting with Informational Text for Close and Critical ReadingNo ratings yet

- Report Card SF 9 ES k12 Grade 4 6 ModularDocument2 pagesReport Card SF 9 ES k12 Grade 4 6 Modularkian josefNo ratings yet

- SPG Action Plan 2022-2023Document2 pagesSPG Action Plan 2022-2023IVY PESCADERONo ratings yet

- G11 W4 I Am An STIerDocument3 pagesG11 W4 I Am An STIerSapphire RedNo ratings yet

- Shodhganga@INFLIBNET - Search 2Document10 pagesShodhganga@INFLIBNET - Search 2edufolderallNo ratings yet

- The Development Plan Is Evolved Through The Shared Leadership of The School and The Community StakeholdersDocument11 pagesThe Development Plan Is Evolved Through The Shared Leadership of The School and The Community StakeholdersMarlynNo ratings yet

- Ghana Northern RegionDocument23 pagesGhana Northern RegionAto QuansahNo ratings yet

- Analytic RubricsDocument2 pagesAnalytic RubricsLorenzo B. FollosoNo ratings yet

- Finals Gensoc AlmeraDocument3 pagesFinals Gensoc AlmerajustinalmeraNo ratings yet

- MPS Grade 5Document1 pageMPS Grade 5HeizelMeaVenturaLapuz-SuguitanNo ratings yet

- Is It Independent Clause or Dependent Clause PDFDocument2 pagesIs It Independent Clause or Dependent Clause PDFjon_kasilagNo ratings yet

- Link BelajarDocument19 pagesLink BelajarAlya nurfatmahNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesCecile AmbrocioNo ratings yet

- Dr. R. Shivashankar: (1) Biographical Data (A) EducationDocument36 pagesDr. R. Shivashankar: (1) Biographical Data (A) EducationMohammed Junaid Shaikh100% (1)

- Action Research ProDocument6 pagesAction Research ProRhea PeñarandaNo ratings yet

- 1 1400686 2023 Guidelines - Ted Rogers Future Leader Scholarship FinalDocument3 pages1 1400686 2023 Guidelines - Ted Rogers Future Leader Scholarship FinalAshmeet MahanNo ratings yet

- Word Formation: NounsDocument3 pagesWord Formation: NounsClaudia Zuñiga PeñuelaNo ratings yet

- Academic Calendar 22-23-Aw-Updated NovDocument1 pageAcademic Calendar 22-23-Aw-Updated NovCarolina MulattiNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Sample With FootnotesDocument8 pagesResearch Paper Sample With Footnotesaflbqewzh100% (1)

- Comprehension Homework Y6Document7 pagesComprehension Homework Y6afmtcbjca100% (1)

- 3rd Quarter Learning Plan (ESP GENEROSITY)Document4 pages3rd Quarter Learning Plan (ESP GENEROSITY)Angelica Sibayan QuinionesNo ratings yet

- Faridabad Schools InteractionDocument10 pagesFaridabad Schools Interactionnitinthukral10No ratings yet

- Lomce in EnglishDocument5 pagesLomce in EnglishTeresaNo ratings yet

- Korea EPTA - Aviation English Proficiency Test BrochureDocument11 pagesKorea EPTA - Aviation English Proficiency Test BrochureRichard PrasadNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan (DLP) SY 2020-2021: GRADEDocument6 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan (DLP) SY 2020-2021: GRADEEmmie Lou SalomonNo ratings yet

- N18 Integrated Humanities MarkschemeDocument31 pagesN18 Integrated Humanities MarkschemeGEORGE MATTHEWNo ratings yet

- HTTPS:/WWW - Faeaindia.org/registration2023/fill ApplicationNext - AspxDocument3 pagesHTTPS:/WWW - Faeaindia.org/registration2023/fill ApplicationNext - Aspx8jkzbzst4fNo ratings yet

- Item Analysis With Mastery Level & Frequency of ErrorsDocument3 pagesItem Analysis With Mastery Level & Frequency of ErrorsEdna GamoNo ratings yet

- ENG 189 - SAS#15 - Writing - 2324Document5 pagesENG 189 - SAS#15 - Writing - 2324yuto.daan.swuNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region I Schools Division of Pangasinan II Bautista District Artacho Elementary SchoolDocument5 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Department of Education Region I Schools Division of Pangasinan II Bautista District Artacho Elementary SchoolFrit ZieNo ratings yet

Reading, Writing, and Understanding: Vicki A. Jacobs

Reading, Writing, and Understanding: Vicki A. Jacobs

Uploaded by

Julia Retni AinayaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reading, Writing, and Understanding: Vicki A. Jacobs

Reading, Writing, and Understanding: Vicki A. Jacobs

Uploaded by

Julia Retni AinayaCopyright:

Available Formats

November 2002 | Volume 60 | Number 3

Reading and Writing in the Content Areas Pages 58-61

Reading, Writing, and Understanding

Secondary school teachers are more willing to integrate reading and writing

strategies in their content-area instruction when they see how these strategies

can support their goals for students' understanding.

Vicki A. Jacobs

Why hasn't the concept of secondary reading—also known as "reading and writing across the

curriculum" and "content-area reading and writing"—become better rooted in our schools? One

reason is an understandable reluctance among secondary school teachers to think of

themselves as reading or writing teachers.

Secondary school teachers rightfully consider themselves first and foremost teachers of such

content areas as science, history, and mathematics. When we ask them to integrate reading

and writing in their instruction, it sounds as if we are asking them to teach additional content.

As a result, we get such reactions as, "That's not my job," "I don't have time," or "Why

doesn't the reading teacher do it?" (Jacobs & Wade, 1981). For subject teachers to implement

principles and practices of secondary reading and writing, they must first recognize reading

and writing as meaning-making processes that can support their instructional goals,

particularly those related to understanding content.

Certainly, most teachers would agree that a central purpose of their instruction is to help

students understand something significant about their content area. What do we really mean

when we say that we want our students to understand? Understanding is more than "doing" or

"knowing": Students may do multiplication problems or know historical facts without

understanding much about them. Understanding is a problem-solving process that involves

making meaning of content. Teaching for understanding, in part, involves choosing topics into

which students can find their own points of entry; directly telling students the goals for their

understanding; and developing assessments that allow students to demonstrate their

understanding (Perkins & Blythe, 1994). The principles and practices of secondary reading and

writing provide means by which students can move from understanding goals to

demonstrating understanding.

Reading-to-Learn as a Means of Understanding

The difference between primary and secondary school reading is the difference between

learning to read and using reading to learn (Chall, 1983). Through about the 3rd grade,

students learn to read. They become familiar with the roles that literacy can play in various

contexts, the value of reading, and the enjoyment that reading can provide. They build their

vocabulary, acquire conceptual knowledge, learn about letter-sound relationships and the

relationship between oral and written language, and practice the skills necessary to become

automatic and fluent readers who can tackle the more specialized and technical texts of

secondary reading (Chall, 1983; Chall & Jacobs, 1996; Jacobs, 2000).

Reprinted by permission of the author.

At about the 4th grade, students begin using these early reading skills to learn. Reading-to-

learn is a matter of meaning-making, problem-solving, and understanding.

The process through which students come to understand something from a text is called

comprehension. In order for students to focus on comprehension, the teacher must present a

text as a mystery—a dilemma or problem to be solved. Comprehension is a three-stage

process in which teachers engage students in problem-solving activities that serve as scaffolds

(Bruner, 1975)—between reader and text, and from one stage of the comprehension process

to the next.

Stage 1: Prereading

Frequently, a struggling secondary reader will come to class and say, "I read last night's

homework, but I don't remember anything about it (let alone understand it)!" How

successfully students remember or understand text depends, in part, on how explicitly

teachers have prepared them to read it for clearly defined purposes.

During prereading, teachers help students activate and organize the "given"—the background

knowledge and experience they will use to solve the mystery of the text. The "given" includes

students' cultural and language-based contexts, their biases (for example, from previous

successes or failures with learning about the subject), and the relevant factual and conceptual

knowledge that they have gained from daily experience and formal study. When teachers

know what students bring to their reading, they can purposefully choose strategies that serve

as effective scaffolds between the "given" and the "new" of the text—clarifying unfamiliar

vocabulary and concepts, helping students anticipate the text, and helping them make

personal connections with it—thus promoting their interest, engagement, and motivation

(Jacobs, 1999).

Prereading activities can include brainstorms, graphic organizers of students' background

knowledge (using concept maps, clusters, or webs), or cloze exercises (during which students

attempt to replace important vocabulary or concepts that the teacher has deleted from the

text in order to draw attention to those points). In addition, the teacher or students may

develop questions, through directed writing or interactive discussions, such as, "What do I

already know and what do I need to know before reading?" or "What do I think this passage

will be about, given the headings, graphs, or pictures?" (Jacobs, 1999, p. 4; 2000, p. 38).

Such prereading activities not only prepare students to understand text but also help build

their vocabulary and study skills.

Stage 2: Guided Reading

During guided reading, teachers provide students with the structured means to integrate the

background knowledge that they bring to the text with the "new" knowledge provided by the

text. During guided reading, students probe the text beyond its literal meaning for deeper

understanding. They revise their preliminary questions or predictions; search for tentative

answers; gather, organize, analyze, and synthesize evidence; and begin to make

generalizations or assertions about their new understanding that they want to investigate

further (Jacobs, 1999; Scala, 2001).

Common guided reading activities include directed writing (such as response journals or study

guides) and collaborative problem-solving activities that engage students in searching beyond

the text's literal meaning. For example, teachers might take the factual questions that texts

usually provide at the end of a chapter and transform them into questions that ask how or

why the facts are important or how information that students have to locate in the text

informs the problem that the students are trying to address through their reading (Jacobs,

Reprinted by permission of the author.

2000). As in prereading, such guided reading activities not only enhance comprehension but

also promote vocabulary and study skills.

The ability to self-monitor often distinguishes effective from poor readers in the secondary

years. Thus, guided reading activities might also ask students to reflect on the reading process

itself: to keep a process log of how their background knowledge and experience influences

their understanding of the text, where they get lost in their reading and the possible reasons

why, and what questions they have for the author or the text to clarify their growing

understanding. Teachers can then use these reflections to decide whether they need to be

more explicit about the particular reading strategies that students should use to understand

their texts.

Stage 3: Postreading

During postreading, teachers provide students with opportunities to step back and test the

validity of their tentative understanding of the text. For example, students might "believe" and

"doubt" one another's assertions in light of evidence from the text or outside the text (Jacobs,

2000). By doing so, students help their peers revise and strengthen their arguments, and also

reflect on and improve their own.

Reading Comprehension and Understanding

The stages of instruction in reading comprehension—prereading, guided reading, and

postreading—essentially describe how students can move from understanding their goal to

demonstrating their understanding. This insight can help teachers view these strategies as a

means to accomplish the content-based goal of understanding, rather than simply as add-on

activities.

Writing-to-Learn as a Means of Understanding

Purposes of Writing in Secondary School

We most frequently use writing in secondary schools in two ways. More often, we use writing

as a means to evaluate students' mastery of content or of the written form. Less often, we use

writing as a means to engage students in learning (Applebee, 1981).

For learning, the act of writing provides a chronology of our thoughts, which we can then

label, objectify, modify, or build on; and it engages us in becoming invested in our ideas and

learning. Writing-to-learn forms and extends thinking and thus deepens understanding

(Fulwiler, 1983; Knoblauch & Brannon, 1983). Like reading-to-learn, it is a meaning-making

process.

The Pedagogy of Writing-to-Learn

Research about the most effective ways to improve composition has found positive effects for

such strategies as literary models, freewriting, sentence combining, and scales (also called

rubrics). The strategy most solidly supported by research to improve composition is a process

called inquiry (Hillocks, 1986).

Inquiry treats writing as a problem-solving activity in which students come to understand

something that they want to say before they begin drafting. In an inquiry-based classroom,

teachers guide students through the development of assertions and arguments about these

assertions. They choose instructional strategies to help students 1) find and state specific,

relevant details from personal experience; 2) analyze and generalize about the text or pose

assertions about it; and 3) test the validity of their generalizations, arguments, or assertions

Reprinted by permission of the author.

by predicting and countering potential opposing arguments (Hillocks, 1986). The inquiry

process is a way to discover something worth writing about. Strategies that accomplish the

purposes of composition-based inquiry engage students in developing their thinking in

preparation for drafting (also called prewriting). These writing-to-learn strategies can include

freewriting, focused freewriting, narrative writing, response writing (for example, response

logs, starters, or dialectic notebooks), loop writing (writing on an idea from different

perspectives), and dialogue writing (for example, with an author or a character) (Bard College

Institute for Writing and Thinking, n.d.; Elbow & Belanoff, 1989). Not surprisingly, writing-to-

learn activities are also known as "writing-to-read" strategies—means by which students can

engage with text in order to understand it.

The Relationships Among Reading, Writing, and Understanding

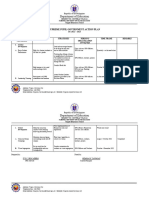

Figure 1 illustrates how reading, writing, and understanding are related. The cognitive

processes involved in the stages of comprehension (prereading, guided reading, and

postreading) are virtually the same as the cognitive processes involved in the three inquiry

stages that promote effective composition. Both reading-to-learn and writing-to-learn are

meaning-making activities that result in understanding—a central goal of content-based

instruction. They both help students proceed from understanding goals to demonstrating

understanding. As a result, if we have engaged our students well in reading-to-learn, then we

will have also prepared them to draft well. As a bonus, we can also use writing-to-learn

strategies to engage students in the prereading, guided reading, and postreading process.

Figure 1. The Interrelation Among Reading, Writing, and Understanding

Staff Development

Most inservice programs on reading and writing across the curriculum offer teachers a variety

of strategies for integrating reading or writing into their content-based instruction. But such

programs rarely ask teachers to examine their own instructional goals and then to consider

how well various reading and writing strategies actually support those goals.

If teachers decide that their goals for students' learning include understanding, then

professional development programs should give them time to think about what they mean by

"understanding" and how they engage students in the process of understanding. Teachers

Reprinted by permission of the author.

might consider the following questions: What strategies do they use to engage students in the

process of making their own meaning? What strategies do they use to prepare and guide

students in problem-solving—allowing students to integrate the "given" of what they bring to a

text and the "new" that the text provides? What means do teachers provide for students to

test assertions of their understanding before they have to demonstrate their understanding?

How explicitly do they share with students the purposes of any given activity in light of their

instructional goals? And how faithfully do the reading and writing strategies that they use

serve their goals?

Only after teachers have examined whether teaching for understanding suits their instructional

goals and after they have defined their role in facilitating understanding can they consider how

the principles and practices of reading-to-learn and writing-to-learn might support their

instruction.

Teachers might begin by discussing what they are already doing with reading and writing and

their reasons for doing so in light of their purposes for students' learning. Frequently, teachers

will discover that they are already making good use of strategies characteristic of reading- and

writing-to-learn. The framework suggested here can help teachers integrate reading-to-learn

and writing-to-learn strategies into content-area instruction more systematically to support

their students' development of understanding.

References

Applebee, A. N. (1981). Writing in the secondary school: English and the content areas. (NCTE

Research Report No. 21). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Bard College Institute for Writing and Thinking Web site. (n.d.). [Online]. Available:

www.writingandthinking.org

Bruner, J. S. (1975). The relevance of education. New York: W. W. Norton.

Chall, J. S. (1983). Stages of reading development. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Chall, J., & Jacobs, V. A. (1996). The reading, writing, and language connection. In J. Shimron

(Ed.), Education and literacy (pp. 33–48). Creskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Elbow, P., & Belanoff, P. (1989). Sharing and responding. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fulwiler, T. (1983). Why we teach writing in the first place. In P. L. Stock (Ed.), fforum:

Essays on theory and practice in the teaching of writing (pp. 273–286). Montclair, NJ:

Boynton/Cook.

Hillocks, G., Jr. (1986). Research on written composition: New directions for teaching. Urbana,

IL: ERIC Clearinghouse on Reading and Communication Skills and the National Conference on

Research in English.

Jacobs, V. A. (1999). What secondary teachers can do to teach reading: A three-step strategy

for helping students delve deeper into texts. Harvard Education Letter, 15(4), 4–5.

Jacobs, V. A. (2000). Using reading to learn: The matter of understanding. Perspectives: The

International Dyslexia Association, 26(4), 38–40.

Jacobs, V. A., & Wade, S. (1981). Teaching reading in secondary content areas. Momentum,

12(4), 8–10.

Knoblauch, C. A., & Brannon, L. (1983). Writing as learning through the curriculum. College

English, 45(5), 465–474.

Reprinted by permission of the author.

Perkins, D., & Blythe, T. (1994). Putting understanding up front. Educational Leadership,

51(5), 11–13.

Scala, M. C. (2001). Working together: Reading and writing in inclusive classrooms. Newark,

DE International Reading Association.

Copyright © Vicki A. Jacobs.

Reprinted by permission of the author.

You might also like

- Cgfns-Profile Entry Instructions PDFDocument11 pagesCgfns-Profile Entry Instructions PDFMosab AfanahNo ratings yet

- Teaching From A Disciplinary Literacy StanceDocument6 pagesTeaching From A Disciplinary Literacy StancesherrymiNo ratings yet

- Fifty Ways to Teach Reading: Fifty Ways to Teach: Tips for ESL/EFL TeachersFrom EverandFifty Ways to Teach Reading: Fifty Ways to Teach: Tips for ESL/EFL TeachersRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Reading and Writing For UnderstandingDocument4 pagesReading and Writing For Understandinglili loti100% (1)

- Riview Jurnal 1Document11 pagesRiview Jurnal 1ripihamdaniNo ratings yet

- Chapter IIDocument15 pagesChapter IIGustari AulyaNo ratings yet

- Reciprocal TeachingDocument18 pagesReciprocal Teachingbluenight99No ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension Intervention StrategiesDocument18 pagesReading Comprehension Intervention Strategiesapi-258330934No ratings yet

- 02 Chapter 2Document39 pages02 Chapter 2jmmagaddatu06No ratings yet

- Definitions of ReadingDocument6 pagesDefinitions of ReadingTiQe 'ansaewa' Sacral HanbieNo ratings yet

- Poetry and Exile Thesis DefenseDocument21 pagesPoetry and Exile Thesis DefenseROMERO, AIRA JOY M.No ratings yet

- Thinking Aloud (Comprehension)Document3 pagesThinking Aloud (Comprehension)dendoinxNo ratings yet

- Content Area ReadingDocument30 pagesContent Area ReadingJohnjohn GalanzaNo ratings yet

- Summary On "A Review On Reading Theories and Its Implication To The Teaching of Reading" by Parlindungan PardedeDocument5 pagesSummary On "A Review On Reading Theories and Its Implication To The Teaching of Reading" by Parlindungan PardedeKayle BorromeoNo ratings yet

- Lesson Planning and Preservice Teachers: A Model For Implementing Research-Based Instructional StrategiesDocument10 pagesLesson Planning and Preservice Teachers: A Model For Implementing Research-Based Instructional StrategiesDeeJey Gaming100% (1)

- MacroSkills ListeningSkillsDocument25 pagesMacroSkills ListeningSkillsCastro, Princess Joy S.No ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument17 pagesChapter IFleur De Liz CredoNo ratings yet

- Teaching EFL ReadingDocument6 pagesTeaching EFL Readingmanalmanila780No ratings yet

- Exploit The Reader's Background KnowledgeDocument4 pagesExploit The Reader's Background KnowledgeismaaNo ratings yet

- Writing AssignmentsDocument6 pagesWriting AssignmentsGe HaxNo ratings yet

- Reading Microskills and Procedure For Training ThemDocument11 pagesReading Microskills and Procedure For Training ThemtrinhquangcoNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Differentiated InstructionDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Differentiated Instructionjzneaqwgf100% (1)

- Cahoon 08Document24 pagesCahoon 08Rya EarlNo ratings yet

- Nunan (1994) Enhancing The Role of The Learner Within The Learning ProcessDocument8 pagesNunan (1994) Enhancing The Role of The Learner Within The Learning ProcessChompNo ratings yet

- Chapter II Scientific ApproachDocument5 pagesChapter II Scientific ApproachtorikNo ratings yet

- PH D Ele Model PaperDocument10 pagesPH D Ele Model PaperMohd ImtiazNo ratings yet

- The Role of Discussion in The Reading ProgramDocument9 pagesThe Role of Discussion in The Reading Programashley_pittman8364No ratings yet

- Dialnet StudentsFirstApproachToReadingComprehension 5476231Document16 pagesDialnet StudentsFirstApproachToReadingComprehension 5476231Kasra VahidiNo ratings yet

- Chapter IiDocument11 pagesChapter IiHani HandayaniNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument5 pagesChapter IAya Tambuli100% (1)

- Disciplinary Literacy A Shift That Makes SenseDocument6 pagesDisciplinary Literacy A Shift That Makes SenseYana ArsyadiNo ratings yet

- 29 2 10125 66918 ElturkiDocument4 pages29 2 10125 66918 ElturkiMehmet YILDIZNo ratings yet

- Developing Reading ActivitiesDocument3 pagesDeveloping Reading ActivitiesbaewonNo ratings yet

- Emg 447 Choice PaperDocument9 pagesEmg 447 Choice Paperapi-699650191No ratings yet

- 12 TEAL Deeper Learning Qs Complete 5 1 0Document5 pages12 TEAL Deeper Learning Qs Complete 5 1 0Jose MendezNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument8 pagesIntroductionELPINIKIMUNo ratings yet

- Reading-Pre While PostDocument18 pagesReading-Pre While PostSiti Hajar Zaid100% (1)

- LtaDocument9 pagesLtasyifaNo ratings yet

- Skripsi FixDocument58 pagesSkripsi Fixresky awaliaNo ratings yet

- Group Work Assignment Methodological ApproachesDocument9 pagesGroup Work Assignment Methodological ApproachesRomina Paola PiñeyroNo ratings yet

- Teaching Reading in A Foreign Language.Document2 pagesTeaching Reading in A Foreign Language.claudio guajardo manzano100% (2)

- Bringing Text Analysis To The Language Classroom: Presented byDocument77 pagesBringing Text Analysis To The Language Classroom: Presented byAdil A BouabdalliNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension Strategies For Elementary Students - Always A Teacher.Document9 pagesReading Comprehension Strategies For Elementary Students - Always A Teacher.Mary ChildNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Bab IIDocument10 pagesLiterature Review Bab IIWindy BesthiaNo ratings yet

- Ii. Frame of TheoriesDocument10 pagesIi. Frame of TheoriesblackarjtelNo ratings yet

- Final Paper ResearchDocument6 pagesFinal Paper ResearchClaudiaNo ratings yet

- Essay 1Document12 pagesEssay 1Laiba TufailNo ratings yet

- Exit Slip JournalDocument8 pagesExit Slip JournalDwi Artawan Gold KnightNo ratings yet

- Writting-Skills-Research-Jesrile-Puda - Docx TheDocument21 pagesWritting-Skills-Research-Jesrile-Puda - Docx Thejesrile pudaNo ratings yet

- The Language Experience Approach and Adult LearnersDocument5 pagesThe Language Experience Approach and Adult LearnersLahandz MejelaNo ratings yet

- Article 2Document6 pagesArticle 2Mohd Zahren ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Final Portfolio 2009Document47 pagesFinal Portfolio 2009claudio guajardo manzano100% (2)

- The Nature of LanguageDocument22 pagesThe Nature of LanguageHolbelMéndezNo ratings yet

- Assignment: Methodological Approaches: General InformationDocument11 pagesAssignment: Methodological Approaches: General InformationAndrea Paz Vallejos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension Levels: Language Skills Phonology Syntax Semantics PragmaticsDocument13 pagesReading Comprehension Levels: Language Skills Phonology Syntax Semantics Pragmaticsnikmatul_ismiNo ratings yet

- Four Activities To Promote Student Engagement With Referencing SkillsDocument12 pagesFour Activities To Promote Student Engagement With Referencing Skillsfabulous annNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3 Literacy PlanningDocument31 pagesAssignment 3 Literacy Planningapi-263403037No ratings yet

- Interacting with Informational Text for Close and Critical ReadingFrom EverandInteracting with Informational Text for Close and Critical ReadingNo ratings yet

- Report Card SF 9 ES k12 Grade 4 6 ModularDocument2 pagesReport Card SF 9 ES k12 Grade 4 6 Modularkian josefNo ratings yet

- SPG Action Plan 2022-2023Document2 pagesSPG Action Plan 2022-2023IVY PESCADERONo ratings yet

- G11 W4 I Am An STIerDocument3 pagesG11 W4 I Am An STIerSapphire RedNo ratings yet

- Shodhganga@INFLIBNET - Search 2Document10 pagesShodhganga@INFLIBNET - Search 2edufolderallNo ratings yet

- The Development Plan Is Evolved Through The Shared Leadership of The School and The Community StakeholdersDocument11 pagesThe Development Plan Is Evolved Through The Shared Leadership of The School and The Community StakeholdersMarlynNo ratings yet

- Ghana Northern RegionDocument23 pagesGhana Northern RegionAto QuansahNo ratings yet

- Analytic RubricsDocument2 pagesAnalytic RubricsLorenzo B. FollosoNo ratings yet

- Finals Gensoc AlmeraDocument3 pagesFinals Gensoc AlmerajustinalmeraNo ratings yet

- MPS Grade 5Document1 pageMPS Grade 5HeizelMeaVenturaLapuz-SuguitanNo ratings yet

- Is It Independent Clause or Dependent Clause PDFDocument2 pagesIs It Independent Clause or Dependent Clause PDFjon_kasilagNo ratings yet

- Link BelajarDocument19 pagesLink BelajarAlya nurfatmahNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesCecile AmbrocioNo ratings yet

- Dr. R. Shivashankar: (1) Biographical Data (A) EducationDocument36 pagesDr. R. Shivashankar: (1) Biographical Data (A) EducationMohammed Junaid Shaikh100% (1)

- Action Research ProDocument6 pagesAction Research ProRhea PeñarandaNo ratings yet

- 1 1400686 2023 Guidelines - Ted Rogers Future Leader Scholarship FinalDocument3 pages1 1400686 2023 Guidelines - Ted Rogers Future Leader Scholarship FinalAshmeet MahanNo ratings yet

- Word Formation: NounsDocument3 pagesWord Formation: NounsClaudia Zuñiga PeñuelaNo ratings yet

- Academic Calendar 22-23-Aw-Updated NovDocument1 pageAcademic Calendar 22-23-Aw-Updated NovCarolina MulattiNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Sample With FootnotesDocument8 pagesResearch Paper Sample With Footnotesaflbqewzh100% (1)

- Comprehension Homework Y6Document7 pagesComprehension Homework Y6afmtcbjca100% (1)

- 3rd Quarter Learning Plan (ESP GENEROSITY)Document4 pages3rd Quarter Learning Plan (ESP GENEROSITY)Angelica Sibayan QuinionesNo ratings yet

- Faridabad Schools InteractionDocument10 pagesFaridabad Schools Interactionnitinthukral10No ratings yet

- Lomce in EnglishDocument5 pagesLomce in EnglishTeresaNo ratings yet

- Korea EPTA - Aviation English Proficiency Test BrochureDocument11 pagesKorea EPTA - Aviation English Proficiency Test BrochureRichard PrasadNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan (DLP) SY 2020-2021: GRADEDocument6 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan (DLP) SY 2020-2021: GRADEEmmie Lou SalomonNo ratings yet

- N18 Integrated Humanities MarkschemeDocument31 pagesN18 Integrated Humanities MarkschemeGEORGE MATTHEWNo ratings yet

- HTTPS:/WWW - Faeaindia.org/registration2023/fill ApplicationNext - AspxDocument3 pagesHTTPS:/WWW - Faeaindia.org/registration2023/fill ApplicationNext - Aspx8jkzbzst4fNo ratings yet

- Item Analysis With Mastery Level & Frequency of ErrorsDocument3 pagesItem Analysis With Mastery Level & Frequency of ErrorsEdna GamoNo ratings yet

- ENG 189 - SAS#15 - Writing - 2324Document5 pagesENG 189 - SAS#15 - Writing - 2324yuto.daan.swuNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region I Schools Division of Pangasinan II Bautista District Artacho Elementary SchoolDocument5 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Department of Education Region I Schools Division of Pangasinan II Bautista District Artacho Elementary SchoolFrit ZieNo ratings yet