Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ss0503 12

ss0503 12

Uploaded by

梁亦采Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

ss0503 12

ss0503 12

Uploaded by

梁亦采Copyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/234631459

Improving Science Reading Comprehension

Article in Science Scope · January 2005

CITATIONS READS

8 5,415

2 authors, including:

Lisa Michelle Martin-Hansen

California State University, Long Beach

28 PUBLICATIONS 332 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Teacher Interview Protocol View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Lisa Michelle Martin-Hansen on 09 November 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

R E A D I N G

Improving

Science Reading

Comprehension

by Jill Caton Johnson and Lisa Martin-Hansen

S

tudents in science classrooms are given numerous predictions if it appears students need support. Students

opportunities to read expository text in a variety of can revisit their prediction and discuss its accuracy.

formats and for a variety of purposes. They read to Students can also participate in an anticipatory set

solve a problem, understand the steps in an experi- (Readence, Bean, and Baldwin 1981, Vacca and Vacca 2001;

ment, gain base knowledge about a concept, answer their own Rasinksi and Padak 2004). An anticipatory set is a set of about

questions, compare their inquiry results with what others five controversial statements about a concept (see Figure 2).

have found, expand their basic understanding of a concept, The teacher writes these out and shares the statements with

and for enjoyment. Students in science classrooms also read students. They then have to either agree or disagree with

a variety of text formats. They read books, directions for the statement. This forces students to think about a concept

experiments, newspaper articles, websites, and peer work. before reading about it. Just like probable passage, students

The reading tasks going on in science classrooms today are can revisit the statements after reading to see if their under-

quite extensive and do complement efforts being made in standing of each statement has changed.

schools to improve reading achievement.

However, science teachers need to support struggling During reading strategies

readers with strategies that will enhance their comprehen- Helping students process what they are reading while they are

sion of science reading materials. This article offers a few reading it has been shown to improve comprehension (Pressley

easy-to-implement strategies that science teachers can use 1999). Activities designed to have students reflect during the

before, during, and after reading. reading process are effective and easy to implement. Such activi-

ties allow the teacher to identify comprehension problems as

Before-reading strategies soon as they occur, instead of backtracking to identify problems

Front-load meaning when reading expository materials. once the entire reading has been completed. This metacognition,

This prepares students for reading and helps comprehen- realizing that meaning is interrupted, is critical if students are to

sion, as they have some prior knowledge of the subject read proficiently. Having students reflect on reading while read-

matter. Specifically, prediction and vocabulary work are ing also sends the essential message that reading is thinking and

important for students to do before they begin reading. that a reader is actively thinking throughout the reading.

Having students predict what the reading will be about is One strategy to increase comprehension while reading is to

important because it can help activate prior knowledge they have students keep a response log. These logs can be structured

have on the topic. It allows them to start connecting the or open-ended. Most structured response logs are two, three,

new reading with their established knowledge. One fun way or four-column charts that have the reader respond to specific

to initiate prediction is the Probable Passage (Beers 2003). information in a reading. In contrast, an open-ended log al-

With this strategy, the teacher lists key words and concepts lows students to choose what they respond to. For example, in

for the students. Then, based on these words, students must Figure 3, the reader is asked to locate something important in

write a prediction about what they will be reading (see

Jill Caton Johnson is an assistant professor of literacy education

Figure 1). Students may be instructed to separate key words at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa. Lisa Martin-Hansen is an

into categories to facilitate a prediction. Teachers may also assistant professor of science education at Georgia State University

provide students with the title of the reading to prompt in Atlanta, Georgia.

12 science scope March 2 0 0 5

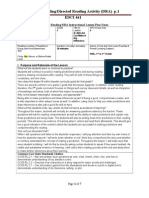

R E A D I N G

MIKE OLLIVER

the reading, categorize it in one of four ways,

FIGURE 1 Probable passage vocabulary for a reading from

and then provide a personal response to the Volcanoes and Earthquakes

information. Students should provide 5 to 10

Title of selection: Volcanoes and Earthquakes

responses to a given reading, depending on its

Words from text: ash, fault, mantle, seismic wave, lava, plate, vent,

length. The teacher can use these response epicenter, magma

logs to ascertain points of confusion, interest,

and mastery. Teachers can do response log

checks once or twice a week. FIGURE 2 Sample anticipation guide

Another strategy that students can use

Book: Storms

while reading is Say Something (Harste,

Short, and Burke 1988). This strategy also Agree Disagree

encourages students to think while reading. Tornadoes generally last 15 minutes or less.

Students work in small groups and read a If you are in your car during a tornado, you should stay in it.

passage from a text chosen by the teacher. The funnel cloud is dark because of the debris it picks up.

Prior to student reading, predetermined

You should lie on the ground during a thunderstorm.

stopping points are marked. For example, a

The heat from lightning causes thunder.

chapter from a text may be divided into 10

All major storms result from cold and warm air mixing.

sections. Students mark each section as a

stopping point. All students begin reading Hurricanes are the least dangerous storm.

and read until stopping at point one. Stu- The eye of a hurricane is calm.

dents take turns “saying something” about A watch and a warning are the same thing.

what was read. All students in the group are

expected to respond to the text. The groups are student-run, but take turns saying something. Prompts like the one in Figure

the teacher serves as a rotating facilitator to assist and observe 4 can be used to help students articulate their thinking about

groups as needed. When everyone is done reading, students the reading (Stubblefield unpublished). Students in the group

March 2 0 0 5 science scope 13

R E A D I N G

FIGURE 3 Response log for Using Force and Motion support each other by clarifying questions that

arise and/or further discussing points of inter-

Page What the text said... Code My response... est. Talking about reading is a powerful tool

9 In space, the force of gravity ! Wow…cool. It’s hard to that can assist in comprehension (Almasi,

is less, so bones in the spine imagine that some astronauts McKeown, and Beck 1996).

move further apart. get 2 inches taller when they

Students also need to be aware of text struc-

are in space. Do they notice

the difference? tures and their important link to main ideas

(Dickson, Simmons, and Kameenui 1995).

Text structures are captions, headings, illustra-

tions, charts, tables, lists, subtitles, titles, and

Coding system other conventions that authors use to organize

! Interesting

a text. These send messages to students about

? Confusing

I Important/Main point what is important in the reading. Authors

W Want to know more about rarely place tables in a text that are irrelevant

to the main idea. Therefore, students need to

be shown that these text structures do indeed

FIGURE 4 Say Something starters (adapted from Beers 2003)

give additional information on what the author

feels is most important. A teacher can have

students connect these structures with the

Question Clarify Connect

main ideas of a text while reading. One way

I don’t get this part… Oh, I get it… This reminds me of…

to do this is to simply have students identify

Why… Let me explain… This is similar to… text structures and explain how they relate to

What do you think… Now I understand… The differences are… the main idea of the text (see Figure 5).

What is… This makes sense now… I have heard of this…

What does this mean… No, I think it means… An example is… After-reading strategies

What if… This is really saying… When students are done with a particular

reading, their thinking and understanding

Predict Comment Explain of a text does not stop. Readers continue to

I predict that… This is hard because… My understanding is…

process and make sense of what they read long

after the actual reading event. Science teach-

I wonder if… This is confusing because… The basic idea is…

ers can provide students with opportunities to

I think that… I think that…

further process their reading, which in turn

The next idea will… can deepen student comprehension.

Literacy teachers frequently use literature

circles to help students process their understand-

ing of a text. This strategy can also be used in

science classrooms. Literature circles are small

groups of students placed together to discuss

what was hard, confusing, interesting, conflicting,

questionable, or relevant about what they have

read. Literature circles of four to five students

can form for one assigned reading or can meet

several times to discuss a longer reading assign-

ment or unit of study. Some teachers assign

roles such as discussion director, illustrator, and

connector (Daniels 1994) for each student in a

literature group so that everyone is encouraged to

participate. We recommend that all students be

MIKE OLLIVER

prepared for literature circles by having a written

response to the reading prepared, questions listed,

or vocabulary terms in need of explanation so that

14 science scope March 2 0 0 5

R E A D I N G

FIGURE 5 Text structures found in Life in the Ocean

Text structure Page Purpose of text structure/Message to the reader

Photograph 10 The author inserted a picture of this fish because it lives in the twilight zone of the ocean. This fish

was picked because it has large eyes that help it find food in this zone, which is dark.

Bold words 14 The term midnight zone is bold to show that it is an important concept. It is one of the four zones

of the ocean.

there is a starting point for small group discussion. Teachers can implement to aid in students’ comprehension of the specific

assess student performance by observing and reading the written concepts they teach. If students can’t comprehend the materi-

responses students prepare for literature circles. Teachers may also als science teachers provide them, then their understanding

require a final reflection paper from each member of the literature of scientific concepts will suffer. When you teach science,

circle. Some teachers encourage each group to prepare a project you are also teaching students how to read for a variety of

or presentation that demonstrates the information learned or purposes and with a variety of materials—both of which will

discussed by the group. prepare students to become better readers.

Another after-reading activity is to have students re-create

what they’ve read in a different form. For example, students References

could re-create the journey of oxygen through the respira- Almasi, J. F., M. G. McKeown, and I. L. Beck. 1996. The nature

tory system in a skit. Students can also use a creative writing of engaged reading in classroom discussions of literature. Journal of

Literacy Research 28: 107–147.

technique known as RAFT (Vanderventer 1979) to present Beers, K. 2003. When kids can’t read. What teachers can do. Ports-

the information found in a reading. Using RAFT, students mouth, NH: Heinemann.

are asked to write from a Role, for a particular Audience, in a Daniels, H. 1994. Literature circles. York, ME: Stenhouse.

particular Format, on a particular Topic. For example, students Dickson, S. V., D. C. Simmons, and E. J. Kameenui. 1995. Text

studying weather could be asked to write as a storm cloud, to an organization and its relation to reading comprehension: A synthesis of the

research. (Tech. Rep. No. 17). Eugene, OR: University of Oregon,

audience of sunshine lovers, in the form of an editorial, about

National Center to Improve the Tools of Educators.

the bias toward the Sun. Graves, D. 1994. A fresh look at writing. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Harste, J. C., K. C. Short, and C. Burke. 1988. Creating classrooms for au-

Special support to struggling students thors: The reading-writing connection. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

All teachers in every discipline have students who are poor Pressley, M. 1999. Self-regulated comprehension processing and its

readers. There are several ways you can provide extra support development through instruction. In Best practices in literacy instruc-

tion, eds. L. Gambrell et al. New York: Guilford.

to these readers. First of all, put reading assignments on au- Rasinksi, T., and N. Padak. 2004. Effective reading strategies. Teach-

diotape and allow students to listen to them once they have ing children who find reading difficult. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River,

attempted the reading on their own. Teachers can have older NJ: Pearson.

students or adult volunteers make tapes for them. This repeated Readence, J. E., T. W. Bean, and R. S. Baldwin. 1981. Content area

exposure can enhance comprehension and alleviate student reading: An integrated approach. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

Stubblefield, A. (Unpublished). Work submitted for course assign-

frustration. Teachers can also provide students with a reading

ment. Adapted from Beers 2003.

buddy. The reading buddy can serve as the first contact for Vacca, R. T. and J. L. Vacca. 2001. Content area reading. 7th ed.

answering questions about the text. This can eliminate a line Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

of students waiting to ask the teacher questions. Teachers can Vanderventer, N. 1979. RAFT: A process to structure prewriting. High-

also provide graphic organizers that assist students in focusing way One: A Canadian Journal of Language Experience (Winter): 26.

on the main ideas. These can be outlines for students to follow

during reading, a list of questions to check for comprehension Science trade books

before a student moves on to the next section, or a dictionary Collins, A. 2002. Storms. Washington, DC: National Geographic

School Publishing.

keyed to the text to help identify essential vocabulary. Huxley, G. 2002. Life in the ocean. Washington, DC: National

Geographic School Publishing.

Partnering science and reading Jerome, K. B. 2003. Volcanoes and earthquakes. Washington, DC:

Concepts being taught in science often rely on students’ National Geographic School Publishing.

reading to build background knowledge or to follow inquiry Phelan, G. 2003. Using force and motion. Washington, DC: National

Geographic School Publishing.

procedures. Science teachers need to know strategies they can

March 2 0 0 5 science scope 15

View publication stats

You might also like

- New Headway Advanced. Teacher's Book PDFDocument168 pagesNew Headway Advanced. Teacher's Book PDFArdita Emini88% (33)

- ESOL Scheme of WorkDocument6 pagesESOL Scheme of WorkLidka Piontek-Legowska100% (3)

- Subject Link 9 TG PDFDocument73 pagesSubject Link 9 TG PDFbrigitte100% (1)

- OrtizDocument64 pagesOrtizapi-295387342No ratings yet

- Subject Link 9tgDocument73 pagesSubject Link 9tgYasser MohamedNo ratings yet

- Edtpa Lesson PlansDocument9 pagesEdtpa Lesson Plansapi-405758157100% (1)

- Eei Lesson Plan 3Document4 pagesEei Lesson Plan 3api-324796495100% (2)

- Comprehension Lesson PlanDocument12 pagesComprehension Lesson Planapi-464778396No ratings yet

- On The Pulse TeacherKitDocument80 pagesOn The Pulse TeacherKitCeleste Paredes100% (1)

- Siop Strategies PowerpointDocument16 pagesSiop Strategies Powerpointapi-523358689No ratings yet

- EIKENDocument6 pagesEIKENmari roxanNo ratings yet

- Review of Reading Explorer 2: Macintyre, P. Boston HeinleDocument5 pagesReview of Reading Explorer 2: Macintyre, P. Boston HeinleAnonymous YRU6YtNo ratings yet

- Effective Comprehension Instruction: Author MonographsDocument4 pagesEffective Comprehension Instruction: Author MonographsEryNo ratings yet

- OgleDocument8 pagesOgleWahyu Sendirii DisiniiNo ratings yet

- Assessing and Teaching Fluency Mini Lesson - Grace Heide 2Document11 pagesAssessing and Teaching Fluency Mini Lesson - Grace Heide 2api-583559880No ratings yet

- Rationale Theory: Common Misconceptions/ DifficultiesDocument4 pagesRationale Theory: Common Misconceptions/ Difficultiesapi-356513456No ratings yet

- Cunninghamb-C T840-M8-EbookpaperDocument7 pagesCunninghamb-C T840-M8-Ebookpaperapi-384666465No ratings yet

- Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Theory Into PracticeDocument7 pagesTaylor & Francis, Ltd. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Theory Into PracticeBeth SummerNo ratings yet

- Teaching & Learning ReadingDocument4 pagesTeaching & Learning Readinghawa ahmedNo ratings yet

- Level II Lesson Plan - CT Observation 2 - Small Group Ela ComprehensionDocument11 pagesLevel II Lesson Plan - CT Observation 2 - Small Group Ela Comprehensionapi-402780026No ratings yet

- Sreplan LaraDocument10 pagesSreplan Laraapi-321791631No ratings yet

- Coming To America Day 1Document3 pagesComing To America Day 1api-343561548No ratings yet

- Education Network - Epc 1 - Reading and Reflecting On Texts PDFDocument11 pagesEducation Network - Epc 1 - Reading and Reflecting On Texts PDFSHIVAM CHOPRA100% (1)

- Supervisorlesson 1Document6 pagesSupervisorlesson 1api-338640283No ratings yet

- Scaffolded Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesScaffolded Lesson Planapi-243738585No ratings yet

- Ashland University Standard Lesson Plan: Dwight Schar College of EducationDocument7 pagesAshland University Standard Lesson Plan: Dwight Schar College of Educationapi-546831448No ratings yet

- Guided Reading GroupsDocument3 pagesGuided Reading Groupsapi-594522478No ratings yet

- Name: Megan Costa Day: Wednesday Date: 9/21/16 Subject: STEM, Grade 3 Common Core Standard(s)Document8 pagesName: Megan Costa Day: Wednesday Date: 9/21/16 Subject: STEM, Grade 3 Common Core Standard(s)api-336708344No ratings yet

- Chapter IIDocument15 pagesChapter IIGustari AulyaNo ratings yet

- How Can I Identify The Main Topic and Key Details? How Can I Ask and Answer Questions About Key Details in A Text?Document7 pagesHow Can I Identify The Main Topic and Key Details? How Can I Ask and Answer Questions About Key Details in A Text?api-378198603No ratings yet

- Fluency LP and Parent LetterDocument5 pagesFluency LP and Parent Letterapi-746634430No ratings yet

- Anticipation Guides - (Literacy Strategy Guide)Document8 pagesAnticipation Guides - (Literacy Strategy Guide)Princejoy ManzanoNo ratings yet

- Integrated Literacy Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesIntegrated Literacy Lesson Planapi-596053421No ratings yet

- STUDY - NOTES - Teaching - Strategies 2Document2 pagesSTUDY - NOTES - Teaching - Strategies 2marleneNo ratings yet

- TEFL SSummaryDocument4 pagesTEFL SSummarymariaNo ratings yet

- Sup Obv Lesson Plan 1Document8 pagesSup Obv Lesson Plan 1api-22742434No ratings yet

- Virtual Win Time LessonDocument7 pagesVirtual Win Time Lessonapi-528416556No ratings yet

- Guided Reading - Dra AssignmentDocument7 pagesGuided Reading - Dra Assignmentapi-286060600No ratings yet

- Educ 464 Lesson Plan 2018 2Document4 pagesEduc 464 Lesson Plan 2018 2api-321764945No ratings yet

- 2.c.bizarre Coincidences: Date Daily Lesson PlanDocument2 pages2.c.bizarre Coincidences: Date Daily Lesson PlanFatjona Cibuku HysolliNo ratings yet

- 2.a.mysterious Creatures: Date Daily Lesson PlanDocument2 pages2.a.mysterious Creatures: Date Daily Lesson PlanFatjona Cibuku HysolliNo ratings yet

- COT 1 (Context Clues) - ELMADocument6 pagesCOT 1 (Context Clues) - ELMAZoragen MorancilNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Directed Reading Thinking Activity 3Document10 pagesJurnal Directed Reading Thinking Activity 3INTAN NURAININo ratings yet

- Lessonplanusftemplate 123Document9 pagesLessonplanusftemplate 123api-242740031No ratings yet

- Action Research: School: Birchmount Grade: 7 Subject: English Outcome: Reading ProficiencyDocument17 pagesAction Research: School: Birchmount Grade: 7 Subject: English Outcome: Reading Proficiencyapi-546993307No ratings yet

- OTP3 e Teachers KitDocument80 pagesOTP3 e Teachers KitCecilia CardozoNo ratings yet

- CELT-P - M3 - Portfolio - Task 3 Ismayilova GunelDocument3 pagesCELT-P - M3 - Portfolio - Task 3 Ismayilova GunelGunel IsmayilovaNo ratings yet

- Edla278 Lesson Sequence AssignmentDocument14 pagesEdla278 Lesson Sequence Assignmentapi-461610001No ratings yet

- Keep em Honest PresentationDocument14 pagesKeep em Honest Presentationapi-316761791No ratings yet

- Assessing and Teaching Fluency Mini Lesson TemplateDocument3 pagesAssessing and Teaching Fluency Mini Lesson Templateapi-667784121No ratings yet

- ApqhsnsiDocument11 pagesApqhsnsiRozak HakikiNo ratings yet

- Pre - Reading Activities Part 1 PDFDocument12 pagesPre - Reading Activities Part 1 PDFBykovskaya sisNo ratings yet

- Cambridge ThinkDocument7 pagesCambridge ThinkHisham ezzaroualy0% (1)

- Eng ReviewerDocument278 pagesEng ReviewerRalph Noah LunetaNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument41 pagesThesisDonald FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Paglinawan Lesson 2Document22 pagesPaglinawan Lesson 2Dhesserie PaglinawanNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Bab IIDocument10 pagesLiterature Review Bab IIWindy BesthiaNo ratings yet

- Lit Review Week 1Document5 pagesLit Review Week 1api-439631634No ratings yet

- Lesson 16 Theme Descriptive Language To Create An AtmosphereDocument3 pagesLesson 16 Theme Descriptive Language To Create An AtmosphereTalant KanatovNo ratings yet

- Final Integrated Unit ProjectDocument22 pagesFinal Integrated Unit Projectapi-373060871No ratings yet

- Critical Reading, Using Reading Prompts To Promote Active Engagement With Text Final PDFDocument6 pagesCritical Reading, Using Reading Prompts To Promote Active Engagement With Text Final PDFemysamehNo ratings yet

- Testing Reading FinalDocument7 pagesTesting Reading Finallevel xxiiiNo ratings yet

- Informational Text Toolkit: Research-based Strategies for the Common Core StandardsFrom EverandInformational Text Toolkit: Research-based Strategies for the Common Core StandardsNo ratings yet

- SSCII English Sep2020Document43 pagesSSCII English Sep2020Ali JawwadNo ratings yet

- Critical Journal ReviewDocument19 pagesCritical Journal ReviewMeysi Hutapea100% (1)

- Reilly PowerpointDocument31 pagesReilly Powerpointapi-540911228No ratings yet

- Finding Reasons Why Research Is Important Seems Like A NoDocument8 pagesFinding Reasons Why Research Is Important Seems Like A NoPaul John Garcia RaciNo ratings yet

- Alternative AssessmentDocument59 pagesAlternative AssessmentEko SuwignyoNo ratings yet

- Kamu Personel Seçme Sinavi: Yabanci Dil (İngilizce) ÖğretmenliğiDocument20 pagesKamu Personel Seçme Sinavi: Yabanci Dil (İngilizce) ÖğretmenliğiBirol YamanNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Watching Authentic English Videos With and Without Subtitles On Listening and Reading Skills of EFL LearnersDocument6 pagesThe Effects of Watching Authentic English Videos With and Without Subtitles On Listening and Reading Skills of EFL LearnerslianlizakichiaNo ratings yet

- TEACHING ENGLISH FOR SPECIFIC PURPOSES - PPSXDocument9 pagesTEACHING ENGLISH FOR SPECIFIC PURPOSES - PPSXzyanmktsdNo ratings yet

- BasalDocument2 pagesBasalMasirah MukhtarNo ratings yet

- Edci 461 - Guided Reading Dra Lesson Plan Template Spring 2015Document5 pagesEdci 461 - Guided Reading Dra Lesson Plan Template Spring 2015api-286600836No ratings yet

- Smelly Clyde - Guided Reading LessonDocument5 pagesSmelly Clyde - Guided Reading Lessonapi-286042559No ratings yet

- MelindaDocument6 pagesMelindaNovia Eva D4 MIKNo ratings yet

- Action Research Presentation On Reading ComprehensionDocument7 pagesAction Research Presentation On Reading ComprehensionEuropez AlaskhaNo ratings yet

- DLL in English 4 (4th Quarter-Week 4)Document5 pagesDLL in English 4 (4th Quarter-Week 4)PadaDredNo ratings yet

- DLL English-3 Q4 W2Document4 pagesDLL English-3 Q4 W2Blessed GuillermoNo ratings yet

- Week Three Lesson Plan Bread and Jam For FrancesDocument2 pagesWeek Three Lesson Plan Bread and Jam For Francesapi-29831576No ratings yet

- Year2 ComprehensionDocument44 pagesYear2 ComprehensionNormaDeCastroNo ratings yet

- Guided Reading Assessment Form StinsonDocument7 pagesGuided Reading Assessment Form Stinsonshadydogv5No ratings yet

- Action Plan On Campus JournalismDocument1 pageAction Plan On Campus JournalismJessa Mae Tuazon II100% (5)

- Preparing For The LsatDocument28 pagesPreparing For The LsatRonald ManlapazNo ratings yet

- w2 Assignment - Lesson PlansDocument5 pagesw2 Assignment - Lesson Plansapi-375889476No ratings yet

- June 2021 Examiner ReportDocument64 pagesJune 2021 Examiner ReportThunder StrikeNo ratings yet

- Playful Poems That Build Reading SkillsDocument96 pagesPlayful Poems That Build Reading SkillsKodra Roxana100% (8)

- Unit 2 Lesson 3Document3 pagesUnit 2 Lesson 3api-240273723No ratings yet

- Plan Diario de InglésDocument3 pagesPlan Diario de InglésceiralisNo ratings yet

- ESL Lesson Frameworks - TEFL HorizonsDocument6 pagesESL Lesson Frameworks - TEFL HorizonsRoberta NoélliaNo ratings yet