Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Module 2 - Types of Curriculum

Module 2 - Types of Curriculum

Uploaded by

Clauditte SaladoCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- University of Rizal System Graduate SchoolDocument3 pagesUniversity of Rizal System Graduate SchoolTwinkle Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- 6503 2Document17 pages6503 2Muhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Curriculum DesignDocument15 pagesCurriculum Designahmed100% (4)

- Weaknesses in Writing A Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesWeaknesses in Writing A Lesson PlanJOHN CARMELO SAULON100% (2)

- M404 Unit - 2-2.3Document9 pagesM404 Unit - 2-2.3Vinod RanaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The PurposefulDocument8 pagesCurriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The PurposefulCHARLYN MAE EBUENGANo ratings yet

- Purpose of Curriculum Design: Stage: 3Document4 pagesPurpose of Curriculum Design: Stage: 3Hayder AliNo ratings yet

- Purpose of Curriculum DesignDocument2 pagesPurpose of Curriculum DesignFaiqa AtiqueNo ratings yet

- Purpose of Curriculum Design: Curriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The Purposeful, Deliberate, andDocument3 pagesPurpose of Curriculum Design: Curriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The Purposeful, Deliberate, andMoira Kate SantosNo ratings yet

- NAME:Vinita Raj ROLL NO.:0000267187 Course Code:6503 SEMESTER: Spring 2022Document17 pagesNAME:Vinita Raj ROLL NO.:0000267187 Course Code:6503 SEMESTER: Spring 2022Karampuri BabuNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design ModelsDocument4 pagesCurriculum Design ModelsMadel RonemNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design QualitiesDocument3 pagesCurriculum Design QualitiesJhodie Anne IsorenaNo ratings yet

- Assignment No.2 (Code 6503)Document22 pagesAssignment No.2 (Code 6503)Muhammad MudassirNo ratings yet

- Types of Curriculum DesignDocument2 pagesTypes of Curriculum DesignM Salman AwanNo ratings yet

- Teacher Level FactorsDocument12 pagesTeacher Level FactorsMiner Casañada Piedad0% (1)

- Curriculum DesignDocument1 pageCurriculum DesignJobelle VergaraNo ratings yet

- Purpose of Curriculum Design: Curriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The Purposeful, Deliberate, andDocument2 pagesPurpose of Curriculum Design: Curriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The Purposeful, Deliberate, andRosiel A. InocNo ratings yet

- Complete Overview of The Curriculum Development ProcessDocument4 pagesComplete Overview of The Curriculum Development ProcessAsnema BatunggaraNo ratings yet

- What Is Curriculum DesignDocument6 pagesWhat Is Curriculum DesignPam Aliento AlcorezaNo ratings yet

- Jawaban Curricullum Design - UAS. 4th March 2023. FINALDocument12 pagesJawaban Curricullum Design - UAS. 4th March 2023. FINALSuci WMNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The PurposefulDocument5 pagesCurriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The PurposefulEdz ArroyalNo ratings yet

- Second Assignment (6503)Document29 pagesSecond Assignment (6503)Ahmad RehmanNo ratings yet

- Curriculum DevelopmentDocument6 pagesCurriculum Developmentbernadette embienNo ratings yet

- Curriculum DevelopmentDocument3 pagesCurriculum DevelopmentFranklin BallonNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development Can Be Defined As The StepDocument4 pagesCurriculum Development Can Be Defined As The Stepverlynne loginaNo ratings yet

- D. Curriculum Development Processes and Models 1Document3 pagesD. Curriculum Development Processes and Models 1CATABAY, JORDAN D.No ratings yet

- CURRICULUMDESIGNDocument2 pagesCURRICULUMDESIGNAlyn Joyce G. LibradoNo ratings yet

- Concept of Curriculum DesignDocument2 pagesConcept of Curriculum DesignMARIA VERONICA TEJADANo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design: Presented By: Fidel Estepa BoluntateDocument9 pagesCurriculum Design: Presented By: Fidel Estepa Boluntatefidel boluntateNo ratings yet

- Key Words: Classroom, Curriculum, Design, Education, Knowledge, Learning, Student, TeacherDocument4 pagesKey Words: Classroom, Curriculum, Design, Education, Knowledge, Learning, Student, TeacherichikoNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document8 pagesAssignment 2ChokkEyyNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design TipsDocument11 pagesCurriculum Design TipsTofuraii SophieNo ratings yet

- What Is Curriculum DesignDocument5 pagesWhat Is Curriculum DesignCorteza, Ricardo Danilo E. UnknownNo ratings yet

- Curriculum DesignDocument18 pagesCurriculum DesignPalero RosemarieNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development and The 3 Models ExplainedDocument4 pagesCurriculum Development and The 3 Models ExplainedKC Reniva100% (1)

- Principles Strategies and Approaches Pasatiempo Jeffrey E. PH.DDocument37 pagesPrinciples Strategies and Approaches Pasatiempo Jeffrey E. PH.DPhineps CanoyNo ratings yet

- PED09 Narrative Report - Hernandez and HizolaDocument4 pagesPED09 Narrative Report - Hernandez and HizolaAzaleaNo ratings yet

- Medm 202Document12 pagesMedm 202Alvett Tan VillaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Planning in Education and Training CoursesDocument3 pagesLesson Planning in Education and Training CoursesHiền NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Unit II Develop Training CurriculumDocument9 pagesUnit II Develop Training CurriculumErric TorresNo ratings yet

- Social Studies Curriculum Designs: Task 1. Subject-Centered Design (10pts)Document3 pagesSocial Studies Curriculum Designs: Task 1. Subject-Centered Design (10pts)Kazumi WelhemsenNo ratings yet

- Attributes and Development of A CurriculumDocument5 pagesAttributes and Development of A CurriculumSana MsoutiNo ratings yet

- The 3 Models of Curriculum DesignDocument12 pagesThe 3 Models of Curriculum DesignKenneth Delegencia GallegoNo ratings yet

- What Is The Meaning of Lesson PlanningDocument3 pagesWhat Is The Meaning of Lesson PlanningReinjane Mae FernandezNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design Tips: Consider Creating A Curriculum Map (Also Known As A CurriculumDocument2 pagesCurriculum Design Tips: Consider Creating A Curriculum Map (Also Known As A Curriculumclara dupitasNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Crafting The CurriculumDocument22 pagesModule 3 Crafting The CurriculumkeithdagumanNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development-Types, Principles & Process of Curriculum DevelopmentDocument7 pagesCurriculum Development-Types, Principles & Process of Curriculum DevelopmentFarah BahrouniNo ratings yet

- Criticism of Subject Centred ApproachDocument18 pagesCriticism of Subject Centred ApproachAnonymous zORD37r0Y100% (2)

- Writing My Lesson - Educ 60Document4 pagesWriting My Lesson - Educ 60JEZIEL BALANo ratings yet

- Puntos 4, 5 y 6Document4 pagesPuntos 4, 5 y 6Fátima LópezNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Lesson Planning For Student SuccessDocument2 pagesThe Importance of Lesson Planning For Student SuccessJustine MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development Contemporary Curriculum DesignsDocument4 pagesCurriculum Development Contemporary Curriculum DesignsTofuraii SophieNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Academic Plan and Backward Design Curriculum What Is Curriculum As An Academic Plan?Document6 pagesCurriculum Academic Plan and Backward Design Curriculum What Is Curriculum As An Academic Plan?Simple LadNo ratings yet

- Ormulation of Objectives in The Curriculum Basing On The Following CriteriaDocument6 pagesOrmulation of Objectives in The Curriculum Basing On The Following CriteriaZabron LuhendeNo ratings yet

- Unit II Lesson 2 SC-PEHDocument4 pagesUnit II Lesson 2 SC-PEHJewin OmarNo ratings yet

- Jeffrey Beloso Bas BSED - Fil 3-B Subject: PROF ED 9 Instructor: Mrs. Bernardita ManaloDocument3 pagesJeffrey Beloso Bas BSED - Fil 3-B Subject: PROF ED 9 Instructor: Mrs. Bernardita ManaloJeff Beloso BasNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design: Jandy P. AysonDocument11 pagesCurriculum Design: Jandy P. AysonJandy P. AysonNo ratings yet

- Rudolf 2Document9 pagesRudolf 2kim mutiaNo ratings yet

- Prof Ed Teaching StrategyDocument5 pagesProf Ed Teaching Strategykim mutiaNo ratings yet

- CurriculumDocument6 pagesCurriculummarlokynNo ratings yet

- Chapter-VI Realistic StoriesDocument6 pagesChapter-VI Realistic StoriesClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- CurriculumDocument57 pagesCurriculumClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Chapter-IV FablesDocument8 pagesChapter-IV FablesClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Chapter-II Dev. of Poetry For ChildrenDocument17 pagesChapter-II Dev. of Poetry For ChildrenClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- MODULE 2 Crafting The CurriculumDocument31 pagesMODULE 2 Crafting The CurriculumClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 8 (Part 1)Document13 pagesLesson 8 (Part 1)Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Curriculum EssentialsDocument48 pagesCurriculum EssentialsClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Chapter I - ReadingDocument7 pagesChapter I - ReadingClauditte Salado100% (1)

- Lesson 7Document8 pagesLesson 7Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5Document17 pagesLesson 5Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6Document15 pagesLesson 6Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2Document15 pagesLesson 2Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4Document8 pagesLesson 4Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3Document19 pagesLesson 3Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1Document13 pagesLesson 1Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

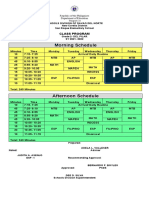

- Classprogram New NormalDocument2 pagesClassprogram New NormalClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- CLASS-PROGRAM-F2F-clau - NewDocument3 pagesCLASS-PROGRAM-F2F-clau - NewClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

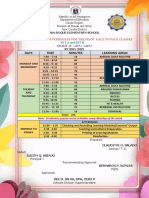

- Clasrroom Daily MonitoringDocument4 pagesClasrroom Daily MonitoringClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- An Activity Matrix On Teaching Reading in Contextualization With EnglishDocument2 pagesAn Activity Matrix On Teaching Reading in Contextualization With EnglishClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Grades Lapu2xDocument5 pagesGrades Lapu2xClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Teaching Profession ReviewerDocument12 pagesTeaching Profession Reviewerlilixuxi53No ratings yet

- Philosophy of Islamic Religion Based On Moderation 2Document15 pagesPhilosophy of Islamic Religion Based On Moderation 2bagas witzNo ratings yet

- Harold A. Abella - Cbc-Reviewer in Educ 1, 2 and 3Document11 pagesHarold A. Abella - Cbc-Reviewer in Educ 1, 2 and 3ABELLA, HAROLD A.No ratings yet

- Matthew ChesebroughDocument2 pagesMatthew Chesebroughapi-213606338No ratings yet

- What Is EducationDocument9 pagesWhat Is EducationAnnissa HypeTribeNo ratings yet

- Professional Education ReviewerDocument86 pagesProfessional Education Reviewerconnie1joy1alarca1om50% (2)

- Edu601 Philosophy of Education (Past Solved Questions Final Term)Document21 pagesEdu601 Philosophy of Education (Past Solved Questions Final Term)Misbah HanifNo ratings yet

- FD Educational Philosophy Paper - Adina TapiaDocument7 pagesFD Educational Philosophy Paper - Adina Tapiaapi-612103051No ratings yet

- 8609 QuizDocument41 pages8609 QuizattiaNo ratings yet

- Branches of Philosophy Appropriate For LDocument11 pagesBranches of Philosophy Appropriate For LMerito MhlangaNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Education: Albert E. Lupisan, Ed.D. FacilitatorDocument36 pagesPhilosophy of Education: Albert E. Lupisan, Ed.D. Facilitatorvasil jiang100% (1)

- Quality EducationDocument53 pagesQuality EducationdhankarrNo ratings yet

- Ped 100 Act1Document1 pagePed 100 Act1Jonalyn OmerezNo ratings yet

- Edu200 Philosophical Perspectives in Education Parts1 4.HTMLDocument10 pagesEdu200 Philosophical Perspectives in Education Parts1 4.HTMLTrisha MarieNo ratings yet

- 1bruners Spiral Curriculum For Teaching & LearningDocument7 pages1bruners Spiral Curriculum For Teaching & LearningNohaNo ratings yet

- Edu 314 - Comparative EducationDocument87 pagesEdu 314 - Comparative EducationRodel G. Esteban Lpt100% (1)

- Philosophical Foundations of EducationDocument12 pagesPhilosophical Foundations of EducationJazmin Kate Abogne100% (1)

- Philosophy of EducationDocument14 pagesPhilosophy of EducationKhadijah ElamoreNo ratings yet

- Syllabus For Philosophy of EducationDocument9 pagesSyllabus For Philosophy of EducationDalePagunsanDariaganNo ratings yet

- ch9 Curriculum Position - Transforming Society Macnaughton GDocument31 pagesch9 Curriculum Position - Transforming Society Macnaughton Gapi-664251071No ratings yet

- (Unit 01) Introduction To PhilosophyDocument8 pages(Unit 01) Introduction To PhilosophyZain AhmadNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Christian EducationDocument6 pagesPhilosophy of Christian Educationapi-251979005No ratings yet

- Music Education PhilosophyDocument2 pagesMusic Education Philosophyapi-272942870No ratings yet

- Art and Design NotesDocument8 pagesArt and Design Noteskabambaleonard4No ratings yet

- Dewey's Thought On EducationDocument14 pagesDewey's Thought On EducationIrfanullah FarooqiNo ratings yet

- Buiding A Personal Philosophy of EducationDocument13 pagesBuiding A Personal Philosophy of EducationJeremy DupaganNo ratings yet

- Project 1Document30 pagesProject 1Taqwa ElsayedNo ratings yet

- Sadi, Persian LiteratureDocument12 pagesSadi, Persian LiteraturetalipguderNo ratings yet

- NewNQUESH Reviewer 2Document90 pagesNewNQUESH Reviewer 2Raymund P. CruzNo ratings yet

Module 2 - Types of Curriculum

Module 2 - Types of Curriculum

Uploaded by

Clauditte SaladoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Module 2 - Types of Curriculum

Module 2 - Types of Curriculum

Uploaded by

Clauditte SaladoCopyright:

Available Formats

Purpose of Curriculum Design

Teachers design each curriculum with a specific educational purpose in mind. The

ultimate goal is to improve student learning, but there are other reasons to employ

curriculum design as well. For example, designing a curriculum for middle school

students with both elementary and high school curricula in mind helps to make sure

that learning goals are aligned and complement each other from one stage to the

next. If a middle school curriculum is designed without taking prior knowledge from

elementary school or future learning in high school into account it can create real

problems for the students.

Types of Curriculum Design

There are three basic types of curriculum design:

• Subject-centered design

• Learner-centered design

• Problem-centered design

• Subject-Centered Curriculum Design

Subject-centered curriculum design revolves around a particular subject

matter or discipline. For example, a subject-centered curriculum may focus on math

or biology. This type of curriculum design tends to focus on the subject rather than

the individual. It is the most common type of curriculum used in K-12 public schools

in states and local districts in the United States.

Subject-centered curriculum design describes what needs to be studied and how

it should be studied. Core curriculum is an example of a subject-centered design that

can be standardized across schools, states, and the country as a whole. In

standardized core curricula, teachers are provided a pre-determined list of things

that they need to teach their students, along with specific examples of how these

things should be taught. You can also find subject-centered designs in large college

classes in which teachers focus on a particular subject or discipline.

The primary drawback of subject-centered curriculum design is that it is not

student-centered. In particular, this form of curriculum design is constructed without

taking into account the specific learning styles of the students. This can cause

problems with student engagement and motivation and may even cause students to

fall behind in class.

Learner-Centered Curriculum Design

In contrast, learner-centered curriculum design takes each individual's needs,

interests, and goals into consideration. In other words, it acknowledges that

students are not uniform and adjust to those student needs. Learner-centered

curriculum design is meant to empower learners and allow them to shape their

education through choices.

Instructional plans in a learner-centered curriculum are differentiated, giving

students the opportunity to choose assignments, learning experiences or activities.

This can motivate students and help them stay engaged in the material that they are

learning.

The drawback to this form of curriculum design is that it is labor-intensive.

Developing differentiated instruction puts pressure on the teacher to create

instruction and/or find materials that are conducive to each student's learning needs.

Teachers may not have the time or may lack the experience or skills to create such a

plan. Learner-centered curriculum design also requires that teachers balance student

wants and interests with student needs and required outcomes, which is not an easy

balance to obtain.

Problem-Centered Curriculum Design

Like learner-centered curriculum design, problem-centered curriculum design

is also a form of student-centered design. Problem-centered curricula focus on

teaching students how to look at a problem and come up with a solution to the

problem. Students are thus exposed to real-life issues, which helps them develop

skills that are transferable to the real world.

Problem-centered curriculum design increases the relevance of the curriculum

and allows students to be creative and innovate as they are learning. The drawback

to this form of curriculum design is that it does not always take learning styles into

consideration.

There are three basic types of curriculum design—subject-centered,

learner-centered, and problem-centered design.

Subject-centered curriculum design revolves around a particular subject

matter or discipline, such as mathematics, literature or biology. This type of

curriculum design tends to focus on the subject, rather than the student. It is the

most common type of standardized curriculum that can be found in K-12 public

schools.

Teachers compile lists of subjects, and specific examples of how they should

be studied. In higher education, this methodology is typically found in large

university or college classes where teachers focus on a particular subject or

discipline.

Subject-centered curriculum design is not student-centered, and the model is

less concerned with individual learning styles compared to other forms of curriculum

design. This can lead to problems with student engagement and motivation and may

cause students who are not responsive to this model to fall behind.

Learner-centered curriculum design, by contrast, revolves around

student needs, interests and goals. It acknowledges that students are not uniform

but individuals, and therefore should not, in all cases, be subject to a standardized

curriculum. This approach aims to empower learners to shape their education

through choices.

Differentiated instructional plans provide an opportunity to select

assignments, teaching and learning experiences, or activities. This form of

curriculum design has been shown to engage and motivate students. The drawback

to this form of curriculum design is that it can create pressure on the educator to

source materials specific to each student’s learning needs. This can be challenging

due to teaching time constraints. Balancing individual student interests with the

institution’s required outcomes could prove to be a daunting task.

Problem-centered curriculum design teaches students how to look at a

problem and formulate a solution. Considered an authentic form of learning because

students are exposed to real-life issues, this model helps students develop skills that

are transferable to the real world. Problem-centered curriculum design has been

shown to increase the relevance of the curriculum and encourages creativity,

innovation and collaboration in the classroom. The drawback to this format is that it

does not always consider individual learning styles.

By considering all three types of curriculum design before they begin

planning, instructors can choose the types that are best suited to both their students

and their course.

Conclusion

Developing, designing and implementing an education curriculum is no easy

task. With the rise of educational technology and the diverse types of students

attending higher educational institutions these days, instructors have their work cut

out for them. But by following the fundamental guidelines and framework of

curriculum development, educators will be setting themselves — and their students

— up for long-term success.

Curriculum Design Tips

The following curriculum design tips can help educators manage each stage

of the curriculum design process.

✓ Identify the needs of stakeholders (i.e., students) early on in the curriculum

design process. This can be done through needs analysis, which involves the

collection and analysis of data related to the learner. This data might include

what learners already know and what they need to know to be proficient in a

particular area or skill. It may also include information about learner

perceptions, strengths, and weaknesses.

✓ Create a clear list of learning goals and outcomes. This will help you to focus

on the intended purpose of the curriculum and allow you to plan instruction

that can achieve the desired results. Learning goals are the things teachers

want students to achieve in the course. Learning outcomes are the

measurable knowledge, skills, and attitudes that students should have

achieved in the course.

✓ Identify constraints that will impact your curriculum design. For example, time

is a common constraint that must be considered. There are only so many

hours, days, weeks or months in the term. If there isn't enough time to

deliver all of the instruction that has been planned, it will impact learning

outcomes.

✓ Consider creating a curriculum map (also known as a curriculum matrix) so

that you can properly evaluate the sequence and coherence of

instruction. Curriculum mapping provides visual diagrams or indexes of a

curriculum. Analyzing a visual representation of the curriculum is a good way

to quickly and easily identify potential gaps, redundancies or alignment issues

in the sequencing of instruction. Curriculum maps can be created on paper or

with software programs or online services designed specifically for this

purpose.

✓ Identify the instructional methods that will be used throughout the course and

consider how they will work with student learning styles. If the instructional

methods are not conducive to the curriculum, the instructional design or the

curriculum design will need to be altered accordingly.

✓ Establish evaluation methods that will be used at the end and during the

school year to assess learners, instructors, and the curriculum. Evaluation will

help you determine if the curriculum design is working or if it is failing.

Examples of things that should be evaluated include the strengths and

weaknesses of the curriculum and achievement rates related to learning

outcomes. The most effective evaluation is ongoing and summative.

✓ Remember that curriculum design is not a one-step process; continuous

improvement is a necessity. The design of the curriculum should be assessed

periodically and refined based on assessment data. This may involve making

alterations to the design partway through the course to ensure that learning

outcomes or a certain level of proficiency will be achieved at the end of the

course.

A model where the curriculum is divided into subject areas, and there is little

flexibility for cross-curricular activity. Subjects are siloed. Emphasis is placed on

acquisition, memorization, and knowledge of each specific content area. Within this

curriculum structure, strong emphasis is placed on instruction, teacher-to-student

explanation, and direct strategies. Direct strategies include lectures, questions, and

answers, as well as teacher-student discussions. These curricula often encourage

memorization and repetitive practice of facts and ideas. Traditionally, students had

little choice about what they studied under these curricula. Now students are given

some degree of freedom in choosing elective subjects. They are also given more

independence to choose from among key topics for personal project work.

Curricula organized around a given subject area (for example, World War II)

will look at the facts, ideas, and skills of that subject area. Learning activities are

then planned around acquisition and memorization of these facts, ideas, and skills.

Teaching methods usually include oral discussions and explanations, lectures, and

questions.

An example of a subject-centered curriculum is the spiral curriculum. The

spiral curriculum is organized around the material to be taught, with less emphasis

on the discipline structure itself, and more emphasis on the concepts and ideas. It is

based around the structure of knowledge, rather than focusing on the detailed

information itself.

A spiral curriculum takes emphasis away from learning specific topics or

pieces of information within a certain time limit. Instead, it aims to expose students

to a wide variety of ideas over and over again. A spiral curriculum, by moving in a

circular pattern from topic to topic, aims to catch students when they first become

ready to comprehend a concept. At the same time, a spiral curriculum works to

continuously reinforce the fundamentals of this concept, to ingrain these

fundamentals in the students’ knowledge base, and to prevent losing students who

aren’t ready for the new lesson.

With this technique, students repeat working on the same skill, but concepts

gradually increase in difficulty. This is referred to as spiraling. What it means in

practice is that each of the core topics of a particular subject is emphasized

throughout the school year and repeated in all of the higher years, but with added

complexities. Instead of covering the skill of “division” in the first semester of a math

class, for example, simple division may be seen in the first semester, and again in

the second semester, but with added double figures.

You might also like

- University of Rizal System Graduate SchoolDocument3 pagesUniversity of Rizal System Graduate SchoolTwinkle Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- 6503 2Document17 pages6503 2Muhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Curriculum DesignDocument15 pagesCurriculum Designahmed100% (4)

- Weaknesses in Writing A Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesWeaknesses in Writing A Lesson PlanJOHN CARMELO SAULON100% (2)

- M404 Unit - 2-2.3Document9 pagesM404 Unit - 2-2.3Vinod RanaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The PurposefulDocument8 pagesCurriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The PurposefulCHARLYN MAE EBUENGANo ratings yet

- Purpose of Curriculum Design: Stage: 3Document4 pagesPurpose of Curriculum Design: Stage: 3Hayder AliNo ratings yet

- Purpose of Curriculum DesignDocument2 pagesPurpose of Curriculum DesignFaiqa AtiqueNo ratings yet

- Purpose of Curriculum Design: Curriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The Purposeful, Deliberate, andDocument3 pagesPurpose of Curriculum Design: Curriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The Purposeful, Deliberate, andMoira Kate SantosNo ratings yet

- NAME:Vinita Raj ROLL NO.:0000267187 Course Code:6503 SEMESTER: Spring 2022Document17 pagesNAME:Vinita Raj ROLL NO.:0000267187 Course Code:6503 SEMESTER: Spring 2022Karampuri BabuNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design ModelsDocument4 pagesCurriculum Design ModelsMadel RonemNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design QualitiesDocument3 pagesCurriculum Design QualitiesJhodie Anne IsorenaNo ratings yet

- Assignment No.2 (Code 6503)Document22 pagesAssignment No.2 (Code 6503)Muhammad MudassirNo ratings yet

- Types of Curriculum DesignDocument2 pagesTypes of Curriculum DesignM Salman AwanNo ratings yet

- Teacher Level FactorsDocument12 pagesTeacher Level FactorsMiner Casañada Piedad0% (1)

- Curriculum DesignDocument1 pageCurriculum DesignJobelle VergaraNo ratings yet

- Purpose of Curriculum Design: Curriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The Purposeful, Deliberate, andDocument2 pagesPurpose of Curriculum Design: Curriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The Purposeful, Deliberate, andRosiel A. InocNo ratings yet

- Complete Overview of The Curriculum Development ProcessDocument4 pagesComplete Overview of The Curriculum Development ProcessAsnema BatunggaraNo ratings yet

- What Is Curriculum DesignDocument6 pagesWhat Is Curriculum DesignPam Aliento AlcorezaNo ratings yet

- Jawaban Curricullum Design - UAS. 4th March 2023. FINALDocument12 pagesJawaban Curricullum Design - UAS. 4th March 2023. FINALSuci WMNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The PurposefulDocument5 pagesCurriculum Design Is A Term Used To Describe The PurposefulEdz ArroyalNo ratings yet

- Second Assignment (6503)Document29 pagesSecond Assignment (6503)Ahmad RehmanNo ratings yet

- Curriculum DevelopmentDocument6 pagesCurriculum Developmentbernadette embienNo ratings yet

- Curriculum DevelopmentDocument3 pagesCurriculum DevelopmentFranklin BallonNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development Can Be Defined As The StepDocument4 pagesCurriculum Development Can Be Defined As The Stepverlynne loginaNo ratings yet

- D. Curriculum Development Processes and Models 1Document3 pagesD. Curriculum Development Processes and Models 1CATABAY, JORDAN D.No ratings yet

- CURRICULUMDESIGNDocument2 pagesCURRICULUMDESIGNAlyn Joyce G. LibradoNo ratings yet

- Concept of Curriculum DesignDocument2 pagesConcept of Curriculum DesignMARIA VERONICA TEJADANo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design: Presented By: Fidel Estepa BoluntateDocument9 pagesCurriculum Design: Presented By: Fidel Estepa Boluntatefidel boluntateNo ratings yet

- Key Words: Classroom, Curriculum, Design, Education, Knowledge, Learning, Student, TeacherDocument4 pagesKey Words: Classroom, Curriculum, Design, Education, Knowledge, Learning, Student, TeacherichikoNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document8 pagesAssignment 2ChokkEyyNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design TipsDocument11 pagesCurriculum Design TipsTofuraii SophieNo ratings yet

- What Is Curriculum DesignDocument5 pagesWhat Is Curriculum DesignCorteza, Ricardo Danilo E. UnknownNo ratings yet

- Curriculum DesignDocument18 pagesCurriculum DesignPalero RosemarieNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development and The 3 Models ExplainedDocument4 pagesCurriculum Development and The 3 Models ExplainedKC Reniva100% (1)

- Principles Strategies and Approaches Pasatiempo Jeffrey E. PH.DDocument37 pagesPrinciples Strategies and Approaches Pasatiempo Jeffrey E. PH.DPhineps CanoyNo ratings yet

- PED09 Narrative Report - Hernandez and HizolaDocument4 pagesPED09 Narrative Report - Hernandez and HizolaAzaleaNo ratings yet

- Medm 202Document12 pagesMedm 202Alvett Tan VillaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Planning in Education and Training CoursesDocument3 pagesLesson Planning in Education and Training CoursesHiền NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Unit II Develop Training CurriculumDocument9 pagesUnit II Develop Training CurriculumErric TorresNo ratings yet

- Social Studies Curriculum Designs: Task 1. Subject-Centered Design (10pts)Document3 pagesSocial Studies Curriculum Designs: Task 1. Subject-Centered Design (10pts)Kazumi WelhemsenNo ratings yet

- Attributes and Development of A CurriculumDocument5 pagesAttributes and Development of A CurriculumSana MsoutiNo ratings yet

- The 3 Models of Curriculum DesignDocument12 pagesThe 3 Models of Curriculum DesignKenneth Delegencia GallegoNo ratings yet

- What Is The Meaning of Lesson PlanningDocument3 pagesWhat Is The Meaning of Lesson PlanningReinjane Mae FernandezNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design Tips: Consider Creating A Curriculum Map (Also Known As A CurriculumDocument2 pagesCurriculum Design Tips: Consider Creating A Curriculum Map (Also Known As A Curriculumclara dupitasNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Crafting The CurriculumDocument22 pagesModule 3 Crafting The CurriculumkeithdagumanNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development-Types, Principles & Process of Curriculum DevelopmentDocument7 pagesCurriculum Development-Types, Principles & Process of Curriculum DevelopmentFarah BahrouniNo ratings yet

- Criticism of Subject Centred ApproachDocument18 pagesCriticism of Subject Centred ApproachAnonymous zORD37r0Y100% (2)

- Writing My Lesson - Educ 60Document4 pagesWriting My Lesson - Educ 60JEZIEL BALANo ratings yet

- Puntos 4, 5 y 6Document4 pagesPuntos 4, 5 y 6Fátima LópezNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Lesson Planning For Student SuccessDocument2 pagesThe Importance of Lesson Planning For Student SuccessJustine MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development Contemporary Curriculum DesignsDocument4 pagesCurriculum Development Contemporary Curriculum DesignsTofuraii SophieNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Academic Plan and Backward Design Curriculum What Is Curriculum As An Academic Plan?Document6 pagesCurriculum Academic Plan and Backward Design Curriculum What Is Curriculum As An Academic Plan?Simple LadNo ratings yet

- Ormulation of Objectives in The Curriculum Basing On The Following CriteriaDocument6 pagesOrmulation of Objectives in The Curriculum Basing On The Following CriteriaZabron LuhendeNo ratings yet

- Unit II Lesson 2 SC-PEHDocument4 pagesUnit II Lesson 2 SC-PEHJewin OmarNo ratings yet

- Jeffrey Beloso Bas BSED - Fil 3-B Subject: PROF ED 9 Instructor: Mrs. Bernardita ManaloDocument3 pagesJeffrey Beloso Bas BSED - Fil 3-B Subject: PROF ED 9 Instructor: Mrs. Bernardita ManaloJeff Beloso BasNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design: Jandy P. AysonDocument11 pagesCurriculum Design: Jandy P. AysonJandy P. AysonNo ratings yet

- Rudolf 2Document9 pagesRudolf 2kim mutiaNo ratings yet

- Prof Ed Teaching StrategyDocument5 pagesProf Ed Teaching Strategykim mutiaNo ratings yet

- CurriculumDocument6 pagesCurriculummarlokynNo ratings yet

- Chapter-VI Realistic StoriesDocument6 pagesChapter-VI Realistic StoriesClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- CurriculumDocument57 pagesCurriculumClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Chapter-IV FablesDocument8 pagesChapter-IV FablesClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Chapter-II Dev. of Poetry For ChildrenDocument17 pagesChapter-II Dev. of Poetry For ChildrenClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- MODULE 2 Crafting The CurriculumDocument31 pagesMODULE 2 Crafting The CurriculumClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 8 (Part 1)Document13 pagesLesson 8 (Part 1)Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Curriculum EssentialsDocument48 pagesCurriculum EssentialsClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Chapter I - ReadingDocument7 pagesChapter I - ReadingClauditte Salado100% (1)

- Lesson 7Document8 pagesLesson 7Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5Document17 pagesLesson 5Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6Document15 pagesLesson 6Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2Document15 pagesLesson 2Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4Document8 pagesLesson 4Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3Document19 pagesLesson 3Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1Document13 pagesLesson 1Clauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Classprogram New NormalDocument2 pagesClassprogram New NormalClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- CLASS-PROGRAM-F2F-clau - NewDocument3 pagesCLASS-PROGRAM-F2F-clau - NewClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Clasrroom Daily MonitoringDocument4 pagesClasrroom Daily MonitoringClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- An Activity Matrix On Teaching Reading in Contextualization With EnglishDocument2 pagesAn Activity Matrix On Teaching Reading in Contextualization With EnglishClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Grades Lapu2xDocument5 pagesGrades Lapu2xClauditte SaladoNo ratings yet

- Teaching Profession ReviewerDocument12 pagesTeaching Profession Reviewerlilixuxi53No ratings yet

- Philosophy of Islamic Religion Based On Moderation 2Document15 pagesPhilosophy of Islamic Religion Based On Moderation 2bagas witzNo ratings yet

- Harold A. Abella - Cbc-Reviewer in Educ 1, 2 and 3Document11 pagesHarold A. Abella - Cbc-Reviewer in Educ 1, 2 and 3ABELLA, HAROLD A.No ratings yet

- Matthew ChesebroughDocument2 pagesMatthew Chesebroughapi-213606338No ratings yet

- What Is EducationDocument9 pagesWhat Is EducationAnnissa HypeTribeNo ratings yet

- Professional Education ReviewerDocument86 pagesProfessional Education Reviewerconnie1joy1alarca1om50% (2)

- Edu601 Philosophy of Education (Past Solved Questions Final Term)Document21 pagesEdu601 Philosophy of Education (Past Solved Questions Final Term)Misbah HanifNo ratings yet

- FD Educational Philosophy Paper - Adina TapiaDocument7 pagesFD Educational Philosophy Paper - Adina Tapiaapi-612103051No ratings yet

- 8609 QuizDocument41 pages8609 QuizattiaNo ratings yet

- Branches of Philosophy Appropriate For LDocument11 pagesBranches of Philosophy Appropriate For LMerito MhlangaNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Education: Albert E. Lupisan, Ed.D. FacilitatorDocument36 pagesPhilosophy of Education: Albert E. Lupisan, Ed.D. Facilitatorvasil jiang100% (1)

- Quality EducationDocument53 pagesQuality EducationdhankarrNo ratings yet

- Ped 100 Act1Document1 pagePed 100 Act1Jonalyn OmerezNo ratings yet

- Edu200 Philosophical Perspectives in Education Parts1 4.HTMLDocument10 pagesEdu200 Philosophical Perspectives in Education Parts1 4.HTMLTrisha MarieNo ratings yet

- 1bruners Spiral Curriculum For Teaching & LearningDocument7 pages1bruners Spiral Curriculum For Teaching & LearningNohaNo ratings yet

- Edu 314 - Comparative EducationDocument87 pagesEdu 314 - Comparative EducationRodel G. Esteban Lpt100% (1)

- Philosophical Foundations of EducationDocument12 pagesPhilosophical Foundations of EducationJazmin Kate Abogne100% (1)

- Philosophy of EducationDocument14 pagesPhilosophy of EducationKhadijah ElamoreNo ratings yet

- Syllabus For Philosophy of EducationDocument9 pagesSyllabus For Philosophy of EducationDalePagunsanDariaganNo ratings yet

- ch9 Curriculum Position - Transforming Society Macnaughton GDocument31 pagesch9 Curriculum Position - Transforming Society Macnaughton Gapi-664251071No ratings yet

- (Unit 01) Introduction To PhilosophyDocument8 pages(Unit 01) Introduction To PhilosophyZain AhmadNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Christian EducationDocument6 pagesPhilosophy of Christian Educationapi-251979005No ratings yet

- Music Education PhilosophyDocument2 pagesMusic Education Philosophyapi-272942870No ratings yet

- Art and Design NotesDocument8 pagesArt and Design Noteskabambaleonard4No ratings yet

- Dewey's Thought On EducationDocument14 pagesDewey's Thought On EducationIrfanullah FarooqiNo ratings yet

- Buiding A Personal Philosophy of EducationDocument13 pagesBuiding A Personal Philosophy of EducationJeremy DupaganNo ratings yet

- Project 1Document30 pagesProject 1Taqwa ElsayedNo ratings yet

- Sadi, Persian LiteratureDocument12 pagesSadi, Persian LiteraturetalipguderNo ratings yet

- NewNQUESH Reviewer 2Document90 pagesNewNQUESH Reviewer 2Raymund P. CruzNo ratings yet