Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

44 viewsAct #4 - Tandog, Judie Lee M. FSM 31

Act #4 - Tandog, Judie Lee M. FSM 31

Uploaded by

Judie Lee TandogThe document discusses three key doctrines in labor law:

1. The police power of the state allows it to enact laws that may interfere with personal liberty or property to promote public welfare. A landmark case upheld the suspension of deployment of Filipino domestic workers as a valid exercise of police power to protect their welfare.

2. Police power refers to the state's authority to protect public health and safety through laws and regulations. It has traditionally been used to regulate issues like nuisances, food/drug safety, and communicable diseases.

3. Police power is the broad authority granted to legislatures to establish laws for public good. It is exercised to promote health, morals, safety and general welfare. The power

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Constitutional Law 2 PDFDocument43 pagesConstitutional Law 2 PDFLeon Milan Emmanuel Romano83% (6)

- Integrated Review May 2020 Batch Second Monthly Exams AfarDocument94 pagesIntegrated Review May 2020 Batch Second Monthly Exams AfarKriztle Kate Gelogo100% (5)

- CDCS &CITF Mixed Paper - 2020Document8 pagesCDCS &CITF Mixed Paper - 2020Phương Anh100% (3)

- 2018 Global Private Equity & Venture Capital Report - Single Licence - pdf82263Document147 pages2018 Global Private Equity & Venture Capital Report - Single Licence - pdf82263wkNo ratings yet

- HRM AssignmentDocument3 pagesHRM AssignmentakshitNo ratings yet

- InvoiceDocument1 pageInvoiceBasim MaqsoodNo ratings yet

- CHCLEG001 Student Assessment Booklet (ID 98960)Document46 pagesCHCLEG001 Student Assessment Booklet (ID 98960)Show Ssti33% (6)

- The Big List of Star Wars NPC Names - RPG ReadyDocument5 pagesThe Big List of Star Wars NPC Names - RPG ReadyMichael LorenzNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Hrmis PDFDocument1 pageGuidelines For Hrmis PDFFaryal FaryalNo ratings yet

- Polirev 1 - Digest - Day 1Document134 pagesPolirev 1 - Digest - Day 1amun dinNo ratings yet

- San Beda College of Law: Cases in Constitutional Law Ii Fundamental Powers of The State Police PowerDocument190 pagesSan Beda College of Law: Cases in Constitutional Law Ii Fundamental Powers of The State Police PowerEdgar Calzita AlotaNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Powers YambaoDocument14 pagesFundamental Powers YambaofclalarilaNo ratings yet

- Goro SpeDocument195 pagesGoro SpeKR ReborosoNo ratings yet

- Gutierrez & Alo Law Offices For PetitionerDocument7 pagesGutierrez & Alo Law Offices For PetitionerJo Irene JumalaNo ratings yet

- Consti II DigestDocument55 pagesConsti II DigestChrisNo ratings yet

- Consti II Cases 1Document65 pagesConsti II Cases 1Nathaniel OlaguerNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Supreme CourtDocument7 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Supreme CourtFrans Emily Perez SalvadorNo ratings yet

- LaborDocument90 pagesLaborMarie CecileNo ratings yet

- Pase Vs Drilon 163 SCRA 386Document7 pagesPase Vs Drilon 163 SCRA 386Ays KwimNo ratings yet

- Pasei Vs DrilonDocument4 pagesPasei Vs DrilonRevz LamosteNo ratings yet

- Phil Assoc Vs DrilonDocument4 pagesPhil Assoc Vs DrilonOwen BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- Sarocam vs. Interorient Maritime Ent., Inc., G.R. No. 167813, June 27, 2006Document4 pagesSarocam vs. Interorient Maritime Ent., Inc., G.R. No. 167813, June 27, 2006JoeyBoyCruzNo ratings yet

- Labor CasesDocument68 pagesLabor CasesAmalia TabingoNo ratings yet

- WHAT'S POLICING and INNOVATIVE POLICINGDocument8 pagesWHAT'S POLICING and INNOVATIVE POLICINGGideon Ray Facsoy (Sphynx)No ratings yet

- Due ProcessDocument7 pagesDue ProcessArciere Jeonsa100% (1)

- Constitutional Law II (Gabriel)Document194 pagesConstitutional Law II (Gabriel)trishayaokasin100% (1)

- Human Rights B.S. Criminal Justice CLE2 (Week 2) : PLT Freddie R. FernandezDocument33 pagesHuman Rights B.S. Criminal Justice CLE2 (Week 2) : PLT Freddie R. FernandezJayson ampatuanNo ratings yet

- 6-17 Pasei vs. Drilon, 163 Scra 386 (1988)Document11 pages6-17 Pasei vs. Drilon, 163 Scra 386 (1988)Reginald Dwight FloridoNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law II ReviewerDocument45 pagesConstitutional Law II Reviewerchitru_chichru100% (2)

- Police Power Philippine Association of Service Exporters vs. DrilonDocument4 pagesPolice Power Philippine Association of Service Exporters vs. DrilonRafael AdanNo ratings yet

- PH Association V DrilonDocument7 pagesPH Association V DrilonAlyssa Bianca OrbisoNo ratings yet

- Gutierrez & Alo Law Offices For PetitionerDocument9 pagesGutierrez & Alo Law Offices For PetitionerJames OcampoNo ratings yet

- Memorandum: Prefatory StatementsDocument3 pagesMemorandum: Prefatory StatementsEmeNo ratings yet

- 3 State Inherent Powers 29 Jan 2019Document5 pages3 State Inherent Powers 29 Jan 2019hm2c74gtnbNo ratings yet

- Labor Cases - PreEmploymentDocument197 pagesLabor Cases - PreEmploymentsamantha.tirthdas2758No ratings yet

- Memorandum: Prefatory StatementsDocument5 pagesMemorandum: Prefatory StatementsEmeNo ratings yet

- (What Is The Prevailing Statute/ Rule?Document16 pages(What Is The Prevailing Statute/ Rule?Cheala ManagayNo ratings yet

- Digested CasesDocument38 pagesDigested CasesJaelein Nicey A. Monteclaro100% (1)

- Philippine Association of Service Exporters vs. DrilonDocument12 pagesPhilippine Association of Service Exporters vs. DrilonMF OrtizNo ratings yet

- Jackson vs. Macalino (G.R. No. 139255, November 24, 2003)Document3 pagesJackson vs. Macalino (G.R. No. 139255, November 24, 2003)Kenny BesarioNo ratings yet

- Police PowerDocument35 pagesPolice PowerJohn Roel S. VillaruzNo ratings yet

- Atty. Gabriel Constitutional Law II Research On Cases Aug 2013Document263 pagesAtty. Gabriel Constitutional Law II Research On Cases Aug 2013Yoo Si Jin100% (1)

- Philippine Association of Service Exporters Vs DrilonDocument22 pagesPhilippine Association of Service Exporters Vs DrilonJerome LeañoNo ratings yet

- Police PowerDocument11 pagesPolice PowerPrasanth DandapaniNo ratings yet

- Article III - Bill of RightsDocument28 pagesArticle III - Bill of RightsNaddie Deore100% (1)

- Constitutional Law IIDocument12 pagesConstitutional Law IImejtulio97No ratings yet

- HR Chap 4Document29 pagesHR Chap 4anjisyNo ratings yet

- 4 Ichong v. HernandezDocument3 pages4 Ichong v. HernandezKJPL_1987No ratings yet

- Sovereignty-The Term May Be Defined As The Supreme Power of The State To Command and Enforce ObedienceDocument6 pagesSovereignty-The Term May Be Defined As The Supreme Power of The State To Command and Enforce ObedienceBinayNo ratings yet

- Bill of Rights Cases Sec 1 - 11 Latest Consolidated CasesDocument479 pagesBill of Rights Cases Sec 1 - 11 Latest Consolidated CasesAbigail Louise Carreon DagdagNo ratings yet

- Labor Law Syl Lab Us ContentDocument26 pagesLabor Law Syl Lab Us Contentshannsantos85No ratings yet

- Ichiong v. HernandezDocument2 pagesIchiong v. HernandezMark Genesis Alvarez RojasNo ratings yet

- Infinity GauntletDocument17 pagesInfinity GauntletGAVIN REYES CUSTODIONo ratings yet

- Bill of RightsDocument37 pagesBill of RightsEllain CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Equal Protection and Privacy of CommunicationDocument19 pagesEqual Protection and Privacy of CommunicationAndrew GarciaNo ratings yet

- Case Notes 2Document66 pagesCase Notes 2Ron Jacob AlmaizNo ratings yet

- Law As An Instrument of JusticeDocument2 pagesLaw As An Instrument of JusticeAlvin ClaridadesNo ratings yet

- Superhuman Registration Act - 1Document3 pagesSuperhuman Registration Act - 1J V Dela Cruz0% (1)

- Consti 2 Paulo Digest CompleteDocument532 pagesConsti 2 Paulo Digest CompleteEthan KurbyNo ratings yet

- Philippine Association of Service Exporters, Inc. v. Drilon, G.R. No. 81958, 6-30-88Document4 pagesPhilippine Association of Service Exporters, Inc. v. Drilon, G.R. No. 81958, 6-30-88Ron AceroNo ratings yet

- Philippine Association of Service Exporters Inc vs. Franklin Drilon G.R. No. 81958Document5 pagesPhilippine Association of Service Exporters Inc vs. Franklin Drilon G.R. No. 81958solomontemplestoneNo ratings yet

- Hell No: Your Right to Dissent in Twenty-First-Century AmericaFrom EverandHell No: Your Right to Dissent in Twenty-First-Century AmericaRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Overview of US Criminal Procedure and the ConstitutionFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Overview of US Criminal Procedure and the ConstitutionNo ratings yet

- Defending Freedom of Contract: Constitutional Solutions to Resolve the Political DivideFrom EverandDefending Freedom of Contract: Constitutional Solutions to Resolve the Political DivideNo ratings yet

- Behind the Bill of Rights: Timeless Principles that Make It TickFrom EverandBehind the Bill of Rights: Timeless Principles that Make It TickNo ratings yet

- The Alert Citizen - Analyzing the Issues Within the Patriot ActFrom EverandThe Alert Citizen - Analyzing the Issues Within the Patriot ActNo ratings yet

- After Reading The Provided Reading MaterialsDocument1 pageAfter Reading The Provided Reading MaterialsJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Group 7 ReportingDocument16 pagesGroup 7 ReportingJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Movie ReviewDocument3 pagesMovie ReviewJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Food Processing TechniquesDocument5 pagesFood Processing TechniquesJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Gastronomy in The PhilippinesDocument12 pagesAssignment 2 Gastronomy in The PhilippinesJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 - Key Concepts and Common CompetenciesDocument12 pagesUnit 2 - Key Concepts and Common CompetenciesJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Reaction Paper On The Eight Strategies For First Rate StudyingDocument1 pageReaction Paper On The Eight Strategies For First Rate StudyingJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Multi-Cultural FoodsDocument10 pagesModule 1 Multi-Cultural FoodsJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Multi-Cultural FoodsDocument5 pagesModule 2 Multi-Cultural FoodsJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Multi-Cultural FoodsDocument9 pagesModule 3 Multi-Cultural FoodsJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- ReviewerDocument5 pagesReviewerJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Module 5 Multi-Cultural FoodsDocument15 pagesModule 5 Multi-Cultural FoodsJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Criteria For Recognizing HeroesDocument3 pagesCriteria For Recognizing HeroesJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Rizal Module 1Document3 pagesRizal Module 1Judie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Judie Lee MDocument7 pagesJudie Lee MJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Tandog FSM 31-Memory Test 1 Rizal (Act#1)Document2 pagesTandog FSM 31-Memory Test 1 Rizal (Act#1)Judie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- How Philip Morris Conquered TurkeyDocument7 pagesHow Philip Morris Conquered TurkeyjoaobastoNo ratings yet

- Electronic RapidTablesDocument4 pagesElectronic RapidTablesGarrisonNo ratings yet

- Special Power of Attorney: Aldwin C - Peque Atty Adrian P. MapaloDocument3 pagesSpecial Power of Attorney: Aldwin C - Peque Atty Adrian P. MapaloAdrian MapaloNo ratings yet

- Offer Letter - Ranjit Sutradhar - Customer Relationship Officer - Dumka, JharkhandDocument5 pagesOffer Letter - Ranjit Sutradhar - Customer Relationship Officer - Dumka, JharkhandRanjit SutradharNo ratings yet

- Takeover Defence TacticsDocument52 pagesTakeover Defence Tacticsrahul-singh-659250% (2)

- College English Satire PaperDocument4 pagesCollege English Satire PaperSean PetersNo ratings yet

- Latest Application For Revalidation of CocDocument3 pagesLatest Application For Revalidation of CocAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Pleading, Drafting and Conveyancing: Application For Maintenance of Under Section 125 (CRPC, 1973)Document16 pagesPleading, Drafting and Conveyancing: Application For Maintenance of Under Section 125 (CRPC, 1973)Vanshdeep Singh SamraNo ratings yet

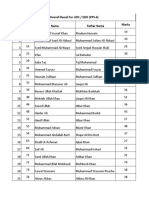

- Tacloban City: Licensure Examination For CIVIL ENGINEERSDocument5 pagesTacloban City: Licensure Examination For CIVIL ENGINEERSPhilBoardResultsNo ratings yet

- St. Nicholas Day Student Version ColorDocument2 pagesSt. Nicholas Day Student Version ColorFilipkoNo ratings yet

- Counter Bautista Estafa bp22Document4 pagesCounter Bautista Estafa bp22Bornok TamolmolNo ratings yet

- MDN Mind Storms IIIDocument45 pagesMDN Mind Storms IIIapi-3752698No ratings yet

- Data SheetDocument12 pagesData Sheetpatrick1009No ratings yet

- Overall Result For UDC / DEO (PPS-4)Document7 pagesOverall Result For UDC / DEO (PPS-4)Aziz Mahar ChannarNo ratings yet

- PP vs. DagmanDocument2 pagesPP vs. DagmanDat Doria PalerNo ratings yet

- Amnf2011 Invitation LetterDocument8 pagesAmnf2011 Invitation LetterLam Kian YipNo ratings yet

- Fraud, Abuse, and Financial Conflicts of InterestDocument4 pagesFraud, Abuse, and Financial Conflicts of InterestKORA HamzathNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Unpaid SellerDocument6 pagesMeaning of Unpaid Sellerr.k.sir7856No ratings yet

- BREAKTHESILENCEDocument10 pagesBREAKTHESILENCEMaria ClaraNo ratings yet

- JawiDocument4 pagesJawiZoey GeeNo ratings yet

- 12.20.BP - Specialaccounts BankingDocument4 pages12.20.BP - Specialaccounts BankingTruth Press MediaNo ratings yet

- Pacasum Vs Zamoranos Full TextDocument3 pagesPacasum Vs Zamoranos Full TextJay PabloNo ratings yet

Act #4 - Tandog, Judie Lee M. FSM 31

Act #4 - Tandog, Judie Lee M. FSM 31

Uploaded by

Judie Lee Tandog0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

44 views6 pagesThe document discusses three key doctrines in labor law:

1. The police power of the state allows it to enact laws that may interfere with personal liberty or property to promote public welfare. A landmark case upheld the suspension of deployment of Filipino domestic workers as a valid exercise of police power to protect their welfare.

2. Police power refers to the state's authority to protect public health and safety through laws and regulations. It has traditionally been used to regulate issues like nuisances, food/drug safety, and communicable diseases.

3. Police power is the broad authority granted to legislatures to establish laws for public good. It is exercised to promote health, morals, safety and general welfare. The power

Original Description:

Original Title

ACT #4- TANDOG, JUDIE LEE M. FSM 31

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document discusses three key doctrines in labor law:

1. The police power of the state allows it to enact laws that may interfere with personal liberty or property to promote public welfare. A landmark case upheld the suspension of deployment of Filipino domestic workers as a valid exercise of police power to protect their welfare.

2. Police power refers to the state's authority to protect public health and safety through laws and regulations. It has traditionally been used to regulate issues like nuisances, food/drug safety, and communicable diseases.

3. Police power is the broad authority granted to legislatures to establish laws for public good. It is exercised to promote health, morals, safety and general welfare. The power

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

44 views6 pagesAct #4 - Tandog, Judie Lee M. FSM 31

Act #4 - Tandog, Judie Lee M. FSM 31

Uploaded by

Judie Lee TandogThe document discusses three key doctrines in labor law:

1. The police power of the state allows it to enact laws that may interfere with personal liberty or property to promote public welfare. A landmark case upheld the suspension of deployment of Filipino domestic workers as a valid exercise of police power to protect their welfare.

2. Police power refers to the state's authority to protect public health and safety through laws and regulations. It has traditionally been used to regulate issues like nuisances, food/drug safety, and communicable diseases.

3. Police power is the broad authority granted to legislatures to establish laws for public good. It is exercised to promote health, morals, safety and general welfare. The power

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 6

Judie Lee M.

Tandog

FSM 31

MOST IMPORTANT DOCTRINES IN LABOR LAW

International and Philippine Labor Code

1. Police Power of the State in Labor Laws

(CASE: PHIL. ASSOCIATION OF SERVICE EXPORTERS INC. (PASEU) vs. HON. F.M.

DRILON et., al, G.R. No. 81958, 30, June 1998, EN Banc, Sarmiento, J.)

The concept of police power is well-established in this jurisdiction. It has been defined as the

“state authority to enact legislation that may interfere with personal liberty or property in order to

promote the general welfare.” As defined, it consists of an imposition of restraint upon liberty or

property, in order to foster the common good. It is not capable of an exact definition but has

been, purposely, veiled in general terms to underscore its all-comprehensive embrace. “Its scope,

ever-expanding to meet the exigencies of the times, even to anticipate the future where it could

be done, provides enough room for an efficient and flexible response to conditions and

circumstances thus assuring the greatest benefits.” It finds no specific Constitutional grant for the

plain reason that it does not owe its origin to the Charter. Along with the taxing power and

eminent domain, it is inborn in the very fact of statehood and sovereignty. It is a fundamental

attribute of government that has enabled it to perform the most vital functions of governance.

Marshall, to whom the expression has been credited, refers to it succinctly as the plenary power

of the State “to govern its citizens.” “The police power of the State … is a power coextensive

with self- protection, and it is not inaptly termed the “law of overwhelming necessity.” It may be

said to be that inherent and plenary power in the State which enables it to prohibit all things

hurtful to the comfort, safety, and welfare of society.” It constitutes an implied limitation on the

Bill of Rights. According to Fernando, it is “rooted in the conception that men in organizing the

state and imposing upon its government limitations to safeguard constitutional rights did not

intend thereby to enable an individual citizen or a group of citizens to obstruct unreasonably the

enactment of such salutary measures calculated to ensure communal peace, safety, good order,

and welfare.” Significantly, the Bill of Rights itself does not purport to be an absolute guaranty

of individual rights and liberties “Even liberty itself, the greatest of all rights, is not unrestricted

license to act according to one’s will.” It is subject to the far more overriding demands and

requirements of the greater number.

Philippine Association of Service Exporters vs. Hon. Franklin Drilon GR No. 81958 – June 30,

1988

FACTS: Philippine Association of Service Exporters, Inc. (PASEI), is a firm ”engaged

principally in the recruitment of Filipino workers, male and female, for overseas placement”.

They challenged the constitutionality of D.O. No. 1,1988 of the DOLE or the “Guidelines

Governing the Temporary Suspension of deployment of the Filipino Domestic and Household

Workers”. The petitioners claimed that the Order was did not apply to all Filipino workers but

only to domestic helpers and females with similar skills, that it is violate of the right to travel, it

was likewise an invalid exercise of the lawmaking power, police power being legislative, and not

executive, in character. The Solicitor General invoked that such was an exercise of the police

power of the Philippine State and that such was in the nature of a police power measure.

ISSUE: Whether or not the said Order is unconstitutional?

RULING: No. The Court ruled that the Department Order was a valid exercise of police power

and that there was no in due discrimination against the sexes given the unhappy plight that has

befallen the female labor force abroad, especially domestic servants, amid exploitative working

conditions marked by, in not a few cases, physical and personal abuse. The sordid tales of

maltreatment suffered by migrant Filipina workers, even rape and various forms of torture,

confirmed by testimonies of returning workers, are compelling motives for urgent Government

action. As precisely the caretaker of Constitutional rights, the Court is called upon to protect

victims of exploitation. In fulfilling that duty, the Court sustained the Government’s efforts.

Unquestionably, it is the avowed objective of Department Order No. 1to “enhance the protection

for Filipino female overseas workers” the SC has no quarrel that in the midst of the terrible

mistreatment Filipina workers have suffered abroad, a ban on deployment will be for their own

good and welfare. The basis of the Court in ruling with the respondent is the provision of Sec. 3,

Art. XIII of the Constitution which states, “The State shall afford full protection to labor, local

and overseas, organized and unorganized, and promote full employment and equality of

employment opportunities for all. “The Court explained the protection of labor as not merely not

signifying the promotion of employment alone, but that the promotion of such employment must

be above all, decent, just, and humane. The Government is duty-bound to ensure that our toiling

expatriates have adequate protection, personally and economically, while away from home.

2. The State’s POLICE POWER

Police power is the right to protect the country and its population from threats to the public

health and safety. The term “police power” predates the development of organized police forces,

which did not develop until the postcolonial period. In the colonial period, police power was

used to control nuisances, such as tanneries that fouled the air and water in towns, to prevent the

sale of bad food, and to quarantine persons who were infected with communicable diseases.

Many of the colonies had active boards of health to administer the police power. This was one of

the main governmental functions in the colonial period. Under the Constitution, the states

retained much of their police power but share the right to regulate health and safety issues with

the federal government. Examples of the federal use of the police power are food and drug

regulations, environmental preservation laws, and workplace safety laws. The states have

companion laws in most of these areas, plus local public health enforcement such as restaurant

inspections, communicable disease control, and drinking water sanitation. In most cases, the

states share jurisdiction with the federal government and the courts will enforce whichever is the

more strict law. State and local public health laws are exercises of the police power. The

application of police power has traditionally implied a capacity to (1) promote the public health,

morals, or safety, and the general well-being of the community; (2) enact and enforce laws for

the promotion of the general welfare; (3) regulate private rights in the public interest; and (4)

extend measures to all great public needs

3. The nature of Police Power

Police power is the plenary power vested in the legislature to make, ordain, and establish

wholesome and reasonable laws, statutes and ordinances, not repugnant to the Constitution, for

the good and welfare of the people. This power to prescribe regulations to promote the health,

morals, education, good order or safety, and general welfare of the people flows from the

recognition that salus populi est suprema lex – the welfare of the people is the supreme law.

While police power rests primarily with the legislature, such power may be delegated, as it is in

fact increasingly being delegated. By virtue of a valid delegation, the power may be exercised by

the President and administrative boards as well as by the lawmaking bodies of municipal

corporations or local governments under an express delegation by the Local Government Code

of 1991. (MMDA, et al. v. Viron Trans. Co., Inc., supra.).

A. When is the exercise of Police Power considered reasonable

When police power is exercised, there is no just compensation to the citizen who loses his

private property. When eminent domain is exercised, there must be just compensation. Thus, the

Court must distinguish and clarify taking in police power and taking in eminent domain.

Government officials cannot just invoke police power when the act constitutes eminent domain.

In People v. Pomar, the Court acknowledged that “by reason of the constant growth of public

opinion in a developing civilization, the term ‘police power’ has never been, and we do not

believe can be, clearly and definitely defined and circumscribed. “The Court stated that the

“definition of the police power of the State must depend upon the particular law and the

particular facts to which it is to be applied.” 7 However, it was considered even then that police

power, when applied to taking 1of property without compensation, refers to property that is

destroyed PR placed outside the commerce of man. The Court declared in Pomar: It is believed

and confidently asserted that no case can be found, in civilized society and well-organized

governments, where individuals have been deprived of their property, under the police power of

the state, without compensation, except in cases where the property in question was used for the

purpose of violating some law legally adopted, or constitutes a nuisance. Among such cases may

be mentioned: Apparatus used in counterfeiting the money of the state; firearms illegally

possessed; opium possessed in violation of law; apparatus used for gambling in violation of law;

buildings and property used for the purpose of violating laws prohibiting the manufacture and

sale of intoxicating liquors; and all cases in which the property itself has become a nuisance and

dangerous and detrimental to the public health, morals and general welfare of the state. In all of

such cases, and in many more which might be cited, the destruction of the property is permitted

in the exercise of the police power of the state. But it must first be established that such property

was used as the instrument for the violation of a valid existing law.

B. The 2 elements of reasonableness un the exercise of Police Power

The proper exercise of the police power requires compliance with the following requisites:

[1] The interests of the public generally, as distinguished from those of a particular class,

require the interference by the State; and

[2] The means employed are reasonably necessary for the attainment of the object sought

and not unduly oppressive upon individuals.

C. Section 16, AR. 10022 of the LABOR CODE

REPUBLIC ACT No. 10022 AN ACT AMENDING REPUBLIC ACT NO. 8042,

OTHERWISE KNOWN AS THE MIGRANT WORKERS AND OVERSEAS FILIPINOS

ACT OF 1995, AS AMENDED, FURTHER IMPROVING THE STANDARD OF

PROTECTION AND PROMOTION OF THE WELFARE OF MIGRANT WORKERS,

THEIR FAMILIES AND OVERSEAS FILIPINOS IN DISTRESS, AND FOR OTHER

PURPOSES

Section 16. Under Section 23 of Republic Act No. 8042, as amended, add new paragraphs © and

(d) with their corresponding subparagraphs to read as follows:

“C. Department of Health. – The Department of Health (DOH) shall regulate the activities and

operations of all clinics which conduct medical, physical, optical, dental, psychological and other

similar examinations, hereinafter referred to as health examinations, on Filipino migrant workers

as requirement for their overseas employment. Pursuant to this, the DOH shall ensure that:

“(c.1) The fees for the health examinations are regulated, regularly monitored and duly published

to ensure that the said fees are reasonable and not exorbitant;

“(c.2) The Filipino migrant worker shall only be required to undergo health examinations when

there is reasonable certainty that he or she will be hired and deployed to the jobsite and only

those health examinations which are absolutely necessary for the type of job applied for or those

specifically required by the foreign employer shall be conducted;

“(c.3) No group or groups of medical clinics shall have a monopoly of exclusively conducting

health examinations on migrant workers for certain receiving countries;

“(c.4) Every Filipino migrant worker shall have the freedom to choose any of the DOH-

accredited or DOH-operated clinics that will conduct his/her health examinations and that his or

her rights as a patient are respected. The decking practice, which requires an overseas Filipino

worker to go first to an office for registration and then farmed out to a medical clinic located

elsewhere, shall not be allowed;

(c.5) Within a period of three (3) years from the effectivity of this Act, all DOH regional and/or

provincial hospitals shall establish and operate clinics that can be serve the health examination

requirements of Filipino migrant workers to provide them easy access to such clinics all over the

country and lessen their transportation and lodging expenses and

“(c.6) All DOH-accredited medical clinics, including the DOH-operated clinics, conducting

health examinations for Filipino migrant workers shall observe the same standard operating

procedures and shall comply with internationally-accepted standards in their operations to

conform with the requirements of receiving countries or of foreign employers/principals. “Any

Foreign employer who does not honor the results of valid health examinations conducted by a

DOH-accredited or DOH-operated clinic shall be temporarily disqualified from the participating

in the overseas employment program, pursuant to POEA rules and regulations. “In case an

overseas Filipino worker is found to be not medically fit upon his/her immediate arrival in the

country of destination, the medical clinic that conducted the health examination/s of such

overseas Filipino worker shall pay for his or her repatriation back to the Philippines and the cost

of deployment of such worker.

“Any government official or employee who violates any provision of this subsection shall be

removed or dismissed from service with disqualification to hold any appointive public office for

five (5) years. Such penalty is without prejudice to any other liability which he or she may have

incurred under existing laws, rules or regulations.

(d) Local Government Units. – In the fight against illegal recruitment, the local government units

(LGUs), in partnership with the POEA, other concerned government agencies, and non-

government organizations advocating the rights and welfare of overseas Filipino workers, shall

take a proactive stance by being primarily responsible for the dissemination of information to

their constituents on all aspects of overseas employment. To carry out this task, the following

shall be undertaken by the LGUs:

“(d.1) Provide a venue for the POEA, other concerned government agencies and non-government

organizations to conduct PEOS to their constituents on a regular basis;

“(d.2) Establish overseas Filipino worker help desk or kiosk in their localities with the objective

of providing current information to their constituents on all the processes aspects of overseas

employment. Such desk or kiosk shall, as be linked to the database of all concerned government

agencies, particularly the POEA for its updated lists of overseas job orders and licensed

recruitment agencies in good standing.”

You might also like

- Constitutional Law 2 PDFDocument43 pagesConstitutional Law 2 PDFLeon Milan Emmanuel Romano83% (6)

- Integrated Review May 2020 Batch Second Monthly Exams AfarDocument94 pagesIntegrated Review May 2020 Batch Second Monthly Exams AfarKriztle Kate Gelogo100% (5)

- CDCS &CITF Mixed Paper - 2020Document8 pagesCDCS &CITF Mixed Paper - 2020Phương Anh100% (3)

- 2018 Global Private Equity & Venture Capital Report - Single Licence - pdf82263Document147 pages2018 Global Private Equity & Venture Capital Report - Single Licence - pdf82263wkNo ratings yet

- HRM AssignmentDocument3 pagesHRM AssignmentakshitNo ratings yet

- InvoiceDocument1 pageInvoiceBasim MaqsoodNo ratings yet

- CHCLEG001 Student Assessment Booklet (ID 98960)Document46 pagesCHCLEG001 Student Assessment Booklet (ID 98960)Show Ssti33% (6)

- The Big List of Star Wars NPC Names - RPG ReadyDocument5 pagesThe Big List of Star Wars NPC Names - RPG ReadyMichael LorenzNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Hrmis PDFDocument1 pageGuidelines For Hrmis PDFFaryal FaryalNo ratings yet

- Polirev 1 - Digest - Day 1Document134 pagesPolirev 1 - Digest - Day 1amun dinNo ratings yet

- San Beda College of Law: Cases in Constitutional Law Ii Fundamental Powers of The State Police PowerDocument190 pagesSan Beda College of Law: Cases in Constitutional Law Ii Fundamental Powers of The State Police PowerEdgar Calzita AlotaNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Powers YambaoDocument14 pagesFundamental Powers YambaofclalarilaNo ratings yet

- Goro SpeDocument195 pagesGoro SpeKR ReborosoNo ratings yet

- Gutierrez & Alo Law Offices For PetitionerDocument7 pagesGutierrez & Alo Law Offices For PetitionerJo Irene JumalaNo ratings yet

- Consti II DigestDocument55 pagesConsti II DigestChrisNo ratings yet

- Consti II Cases 1Document65 pagesConsti II Cases 1Nathaniel OlaguerNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Supreme CourtDocument7 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Supreme CourtFrans Emily Perez SalvadorNo ratings yet

- LaborDocument90 pagesLaborMarie CecileNo ratings yet

- Pase Vs Drilon 163 SCRA 386Document7 pagesPase Vs Drilon 163 SCRA 386Ays KwimNo ratings yet

- Pasei Vs DrilonDocument4 pagesPasei Vs DrilonRevz LamosteNo ratings yet

- Phil Assoc Vs DrilonDocument4 pagesPhil Assoc Vs DrilonOwen BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- Sarocam vs. Interorient Maritime Ent., Inc., G.R. No. 167813, June 27, 2006Document4 pagesSarocam vs. Interorient Maritime Ent., Inc., G.R. No. 167813, June 27, 2006JoeyBoyCruzNo ratings yet

- Labor CasesDocument68 pagesLabor CasesAmalia TabingoNo ratings yet

- WHAT'S POLICING and INNOVATIVE POLICINGDocument8 pagesWHAT'S POLICING and INNOVATIVE POLICINGGideon Ray Facsoy (Sphynx)No ratings yet

- Due ProcessDocument7 pagesDue ProcessArciere Jeonsa100% (1)

- Constitutional Law II (Gabriel)Document194 pagesConstitutional Law II (Gabriel)trishayaokasin100% (1)

- Human Rights B.S. Criminal Justice CLE2 (Week 2) : PLT Freddie R. FernandezDocument33 pagesHuman Rights B.S. Criminal Justice CLE2 (Week 2) : PLT Freddie R. FernandezJayson ampatuanNo ratings yet

- 6-17 Pasei vs. Drilon, 163 Scra 386 (1988)Document11 pages6-17 Pasei vs. Drilon, 163 Scra 386 (1988)Reginald Dwight FloridoNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law II ReviewerDocument45 pagesConstitutional Law II Reviewerchitru_chichru100% (2)

- Police Power Philippine Association of Service Exporters vs. DrilonDocument4 pagesPolice Power Philippine Association of Service Exporters vs. DrilonRafael AdanNo ratings yet

- PH Association V DrilonDocument7 pagesPH Association V DrilonAlyssa Bianca OrbisoNo ratings yet

- Gutierrez & Alo Law Offices For PetitionerDocument9 pagesGutierrez & Alo Law Offices For PetitionerJames OcampoNo ratings yet

- Memorandum: Prefatory StatementsDocument3 pagesMemorandum: Prefatory StatementsEmeNo ratings yet

- 3 State Inherent Powers 29 Jan 2019Document5 pages3 State Inherent Powers 29 Jan 2019hm2c74gtnbNo ratings yet

- Labor Cases - PreEmploymentDocument197 pagesLabor Cases - PreEmploymentsamantha.tirthdas2758No ratings yet

- Memorandum: Prefatory StatementsDocument5 pagesMemorandum: Prefatory StatementsEmeNo ratings yet

- (What Is The Prevailing Statute/ Rule?Document16 pages(What Is The Prevailing Statute/ Rule?Cheala ManagayNo ratings yet

- Digested CasesDocument38 pagesDigested CasesJaelein Nicey A. Monteclaro100% (1)

- Philippine Association of Service Exporters vs. DrilonDocument12 pagesPhilippine Association of Service Exporters vs. DrilonMF OrtizNo ratings yet

- Jackson vs. Macalino (G.R. No. 139255, November 24, 2003)Document3 pagesJackson vs. Macalino (G.R. No. 139255, November 24, 2003)Kenny BesarioNo ratings yet

- Police PowerDocument35 pagesPolice PowerJohn Roel S. VillaruzNo ratings yet

- Atty. Gabriel Constitutional Law II Research On Cases Aug 2013Document263 pagesAtty. Gabriel Constitutional Law II Research On Cases Aug 2013Yoo Si Jin100% (1)

- Philippine Association of Service Exporters Vs DrilonDocument22 pagesPhilippine Association of Service Exporters Vs DrilonJerome LeañoNo ratings yet

- Police PowerDocument11 pagesPolice PowerPrasanth DandapaniNo ratings yet

- Article III - Bill of RightsDocument28 pagesArticle III - Bill of RightsNaddie Deore100% (1)

- Constitutional Law IIDocument12 pagesConstitutional Law IImejtulio97No ratings yet

- HR Chap 4Document29 pagesHR Chap 4anjisyNo ratings yet

- 4 Ichong v. HernandezDocument3 pages4 Ichong v. HernandezKJPL_1987No ratings yet

- Sovereignty-The Term May Be Defined As The Supreme Power of The State To Command and Enforce ObedienceDocument6 pagesSovereignty-The Term May Be Defined As The Supreme Power of The State To Command and Enforce ObedienceBinayNo ratings yet

- Bill of Rights Cases Sec 1 - 11 Latest Consolidated CasesDocument479 pagesBill of Rights Cases Sec 1 - 11 Latest Consolidated CasesAbigail Louise Carreon DagdagNo ratings yet

- Labor Law Syl Lab Us ContentDocument26 pagesLabor Law Syl Lab Us Contentshannsantos85No ratings yet

- Ichiong v. HernandezDocument2 pagesIchiong v. HernandezMark Genesis Alvarez RojasNo ratings yet

- Infinity GauntletDocument17 pagesInfinity GauntletGAVIN REYES CUSTODIONo ratings yet

- Bill of RightsDocument37 pagesBill of RightsEllain CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Equal Protection and Privacy of CommunicationDocument19 pagesEqual Protection and Privacy of CommunicationAndrew GarciaNo ratings yet

- Case Notes 2Document66 pagesCase Notes 2Ron Jacob AlmaizNo ratings yet

- Law As An Instrument of JusticeDocument2 pagesLaw As An Instrument of JusticeAlvin ClaridadesNo ratings yet

- Superhuman Registration Act - 1Document3 pagesSuperhuman Registration Act - 1J V Dela Cruz0% (1)

- Consti 2 Paulo Digest CompleteDocument532 pagesConsti 2 Paulo Digest CompleteEthan KurbyNo ratings yet

- Philippine Association of Service Exporters, Inc. v. Drilon, G.R. No. 81958, 6-30-88Document4 pagesPhilippine Association of Service Exporters, Inc. v. Drilon, G.R. No. 81958, 6-30-88Ron AceroNo ratings yet

- Philippine Association of Service Exporters Inc vs. Franklin Drilon G.R. No. 81958Document5 pagesPhilippine Association of Service Exporters Inc vs. Franklin Drilon G.R. No. 81958solomontemplestoneNo ratings yet

- Hell No: Your Right to Dissent in Twenty-First-Century AmericaFrom EverandHell No: Your Right to Dissent in Twenty-First-Century AmericaRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Overview of US Criminal Procedure and the ConstitutionFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Overview of US Criminal Procedure and the ConstitutionNo ratings yet

- Defending Freedom of Contract: Constitutional Solutions to Resolve the Political DivideFrom EverandDefending Freedom of Contract: Constitutional Solutions to Resolve the Political DivideNo ratings yet

- Behind the Bill of Rights: Timeless Principles that Make It TickFrom EverandBehind the Bill of Rights: Timeless Principles that Make It TickNo ratings yet

- The Alert Citizen - Analyzing the Issues Within the Patriot ActFrom EverandThe Alert Citizen - Analyzing the Issues Within the Patriot ActNo ratings yet

- After Reading The Provided Reading MaterialsDocument1 pageAfter Reading The Provided Reading MaterialsJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Group 7 ReportingDocument16 pagesGroup 7 ReportingJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Movie ReviewDocument3 pagesMovie ReviewJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Food Processing TechniquesDocument5 pagesFood Processing TechniquesJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Gastronomy in The PhilippinesDocument12 pagesAssignment 2 Gastronomy in The PhilippinesJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 - Key Concepts and Common CompetenciesDocument12 pagesUnit 2 - Key Concepts and Common CompetenciesJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Reaction Paper On The Eight Strategies For First Rate StudyingDocument1 pageReaction Paper On The Eight Strategies For First Rate StudyingJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Multi-Cultural FoodsDocument10 pagesModule 1 Multi-Cultural FoodsJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Multi-Cultural FoodsDocument5 pagesModule 2 Multi-Cultural FoodsJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Multi-Cultural FoodsDocument9 pagesModule 3 Multi-Cultural FoodsJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- ReviewerDocument5 pagesReviewerJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Module 5 Multi-Cultural FoodsDocument15 pagesModule 5 Multi-Cultural FoodsJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Criteria For Recognizing HeroesDocument3 pagesCriteria For Recognizing HeroesJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Rizal Module 1Document3 pagesRizal Module 1Judie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Judie Lee MDocument7 pagesJudie Lee MJudie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- Tandog FSM 31-Memory Test 1 Rizal (Act#1)Document2 pagesTandog FSM 31-Memory Test 1 Rizal (Act#1)Judie Lee TandogNo ratings yet

- How Philip Morris Conquered TurkeyDocument7 pagesHow Philip Morris Conquered TurkeyjoaobastoNo ratings yet

- Electronic RapidTablesDocument4 pagesElectronic RapidTablesGarrisonNo ratings yet

- Special Power of Attorney: Aldwin C - Peque Atty Adrian P. MapaloDocument3 pagesSpecial Power of Attorney: Aldwin C - Peque Atty Adrian P. MapaloAdrian MapaloNo ratings yet

- Offer Letter - Ranjit Sutradhar - Customer Relationship Officer - Dumka, JharkhandDocument5 pagesOffer Letter - Ranjit Sutradhar - Customer Relationship Officer - Dumka, JharkhandRanjit SutradharNo ratings yet

- Takeover Defence TacticsDocument52 pagesTakeover Defence Tacticsrahul-singh-659250% (2)

- College English Satire PaperDocument4 pagesCollege English Satire PaperSean PetersNo ratings yet

- Latest Application For Revalidation of CocDocument3 pagesLatest Application For Revalidation of CocAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Pleading, Drafting and Conveyancing: Application For Maintenance of Under Section 125 (CRPC, 1973)Document16 pagesPleading, Drafting and Conveyancing: Application For Maintenance of Under Section 125 (CRPC, 1973)Vanshdeep Singh SamraNo ratings yet

- Tacloban City: Licensure Examination For CIVIL ENGINEERSDocument5 pagesTacloban City: Licensure Examination For CIVIL ENGINEERSPhilBoardResultsNo ratings yet

- St. Nicholas Day Student Version ColorDocument2 pagesSt. Nicholas Day Student Version ColorFilipkoNo ratings yet

- Counter Bautista Estafa bp22Document4 pagesCounter Bautista Estafa bp22Bornok TamolmolNo ratings yet

- MDN Mind Storms IIIDocument45 pagesMDN Mind Storms IIIapi-3752698No ratings yet

- Data SheetDocument12 pagesData Sheetpatrick1009No ratings yet

- Overall Result For UDC / DEO (PPS-4)Document7 pagesOverall Result For UDC / DEO (PPS-4)Aziz Mahar ChannarNo ratings yet

- PP vs. DagmanDocument2 pagesPP vs. DagmanDat Doria PalerNo ratings yet

- Amnf2011 Invitation LetterDocument8 pagesAmnf2011 Invitation LetterLam Kian YipNo ratings yet

- Fraud, Abuse, and Financial Conflicts of InterestDocument4 pagesFraud, Abuse, and Financial Conflicts of InterestKORA HamzathNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Unpaid SellerDocument6 pagesMeaning of Unpaid Sellerr.k.sir7856No ratings yet

- BREAKTHESILENCEDocument10 pagesBREAKTHESILENCEMaria ClaraNo ratings yet

- JawiDocument4 pagesJawiZoey GeeNo ratings yet

- 12.20.BP - Specialaccounts BankingDocument4 pages12.20.BP - Specialaccounts BankingTruth Press MediaNo ratings yet

- Pacasum Vs Zamoranos Full TextDocument3 pagesPacasum Vs Zamoranos Full TextJay PabloNo ratings yet