Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Davies Essay ch10

Davies Essay ch10

Uploaded by

lee tranCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- CHAPTER 1 - General Provisions On Contracts (Arts. 1305-1317)Document20 pagesCHAPTER 1 - General Provisions On Contracts (Arts. 1305-1317)Kim Deiparine85% (20)

- BLAW Quiz in General ProvisionsDocument3 pagesBLAW Quiz in General ProvisionsWyn DignosNo ratings yet

- ContractsDocument4 pagesContractsMschocokisses Shane Sison ÜNo ratings yet

- Document FileDocument1,310 pagesDocument Filelee tranNo ratings yet

- Civ2 QuizDocument13 pagesCiv2 QuizAce Roncalli Jereza Velasco100% (1)

- CasesDocument4 pagesCasesSheldonNo ratings yet

- Breach of Contract Problem Question and SolutionDocument5 pagesBreach of Contract Problem Question and SolutionGovnyoNo ratings yet

- Promoter AgreementDocument3 pagesPromoter Agreementyashvi bansalNo ratings yet

- USA V Kent Hovind Trial Transcripts (1 of 8)Document81 pagesUSA V Kent Hovind Trial Transcripts (1 of 8)AlbertFrank55No ratings yet

- Private Complaint Format MMRDocument29 pagesPrivate Complaint Format MMRMOHAN REDDY100% (1)

- Privity of Contract and Third Party RightsDocument9 pagesPrivity of Contract and Third Party RightsLaraib ShahidNo ratings yet

- Beatson Burrows CartwrightDocument62 pagesBeatson Burrows CartwrightMahdi Bin MamunNo ratings yet

- Privity of ContractDocument5 pagesPrivity of ContractOwuraku Amoako-AttahNo ratings yet

- Discharge JoooDocument4 pagesDischarge Jooopaco kazunguNo ratings yet

- Privity of ContractDocument2 pagesPrivity of ContractShraddhaNo ratings yet

- Review Notes - Contracts, Natural Obligations and Damages 2014Document22 pagesReview Notes - Contracts, Natural Obligations and Damages 2014JanetGraceDalisayFabrero100% (1)

- LEGT 1710: Assignment 2Document8 pagesLEGT 1710: Assignment 2timeflies23No ratings yet

- Chapter 4 LLB Contract Law Worksheet 3 BreakdownDocument33 pagesChapter 4 LLB Contract Law Worksheet 3 Breakdownماتو اریکاNo ratings yet

- Cat 2 Law of ContractDocument3 pagesCat 2 Law of ContractMorganNo ratings yet

- Contracts CH1Document4 pagesContracts CH1Bea Dela PeniaNo ratings yet

- Ngi Contract 1 - 125956Document7 pagesNgi Contract 1 - 125956gnanguni7No ratings yet

- ObliconDocument4 pagesObliconRam BeeNo ratings yet

- Third Party Rights: Beswich V BeswichDocument4 pagesThird Party Rights: Beswich V Beswichnicole camnasio100% (1)

- Doctrine of Privity of Contract Under Contract LawDocument18 pagesDoctrine of Privity of Contract Under Contract Lawdebanga borpujari100% (1)

- Definitions LawDocument10 pagesDefinitions LawNikki RunesNo ratings yet

- Contract eDocument8 pagesContract erajzarmy009No ratings yet

- Gen Prov ContDocument9 pagesGen Prov Contooagentx44No ratings yet

- Study Guide LawDocument2 pagesStudy Guide LawAngela DimituiNo ratings yet

- Discharge of Contract (RPT)Document4 pagesDischarge of Contract (RPT)Basim ZiaNo ratings yet

- Mod9 ItlDocument29 pagesMod9 ItlCoco PimentelNo ratings yet

- Mod9 (Itl)Document27 pagesMod9 (Itl)Tiara LlorenteNo ratings yet

- Civ2 QuizDocument12 pagesCiv2 Quizanon_258621924No ratings yet

- Article 1305 1422 Group 5 FinalDocument174 pagesArticle 1305 1422 Group 5 Finalacem16098No ratings yet

- STUDY GUIDE Pages 329 330 369 370 387Document7 pagesSTUDY GUIDE Pages 329 330 369 370 387Jhonielyn Regalado Ruga100% (3)

- Doctrine of Privity Contract With Case Laws AND ExceptionsDocument21 pagesDoctrine of Privity Contract With Case Laws AND Exceptionstuka IASNo ratings yet

- ASS 5-Reviewer in Midterm Law On Obligations and ContractsDocument9 pagesASS 5-Reviewer in Midterm Law On Obligations and ContractsRev Richmon De ChavezNo ratings yet

- Privity of ContractDocument6 pagesPrivity of ContractAbdul sami bhuttoNo ratings yet

- Law of Contract: ConsiderationDocument19 pagesLaw of Contract: ConsiderationJacob Black100% (1)

- Module 3 - ContractsDocument21 pagesModule 3 - ContractsKoji Brian ReyesNo ratings yet

- Sample Bar Questions With Answers ObliconDocument12 pagesSample Bar Questions With Answers ObliconJen Quilaquil - AlicanNo ratings yet

- Business LawDocument10 pagesBusiness LawKeshvin SidhuNo ratings yet

- Business Law Week 4 (Essential of A Valid Contract)Document27 pagesBusiness Law Week 4 (Essential of A Valid Contract)240450282No ratings yet

- 1styr 1stF ObliCon 2324Document21 pages1styr 1stF ObliCon 2324Yazzy2No ratings yet

- Contract LawDocument7 pagesContract LawVINCENT CHUANo ratings yet

- Reviewer ContractsDocument6 pagesReviewer ContractsBernard de AsisNo ratings yet

- Lecture 13 InterpretationDocument2 pagesLecture 13 InterpretationKeith San PedroNo ratings yet

- Sushant Lalla (57) - INDEMNITYDocument2 pagesSushant Lalla (57) - INDEMNITYSushant LallaNo ratings yet

- FinaDocument10 pagesFinaAnena AlbrightNo ratings yet

- SLL Contract Assignment Grp. 2Document29 pagesSLL Contract Assignment Grp. 2Jacob komba EllieNo ratings yet

- Contracts For The Benefit of Third PartiesDocument16 pagesContracts For The Benefit of Third PartiesErique Li-Onn PhangNo ratings yet

- Andersons Business Law and The Legal Environment Comprehensive Volume 23rd Edition Twome Solutions Manual DownloadDocument6 pagesAndersons Business Law and The Legal Environment Comprehensive Volume 23rd Edition Twome Solutions Manual DownloadJuan Davidson100% (24)

- Article 1315 and 1316Document8 pagesArticle 1315 and 1316Janeiro Brix GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Contract Act LawDocument8 pagesContract Act Lawmukmin09No ratings yet

- Oblicon 4Document5 pagesOblicon 4Borgonia, Khryzlin May C.No ratings yet

- Privity of Contract: Generally in Common LawDocument5 pagesPrivity of Contract: Generally in Common LawMikhail EremenkoNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 8 (Unenforceable Contracts)Document6 pagesCHAPTER 8 (Unenforceable Contracts)phoebe andamo67% (3)

- Doctrine of PrivityDocument6 pagesDoctrine of PrivityPJ 123No ratings yet

- Article 1366. There Shall Be No Reformation in The Following CasesDocument6 pagesArticle 1366. There Shall Be No Reformation in The Following CasesKhim Cortez100% (1)

- Law and Business Administration in Canada Canadian 13th Edition Smyth Test BankDocument22 pagesLaw and Business Administration in Canada Canadian 13th Edition Smyth Test Bankchristinawilliamsmprdegtjxz100% (33)

- The Privity of Contract DoctrineDocument5 pagesThe Privity of Contract DoctrinesivajibuddyNo ratings yet

- Week 6 Slides (Upsa)Document31 pagesWeek 6 Slides (Upsa)BISMARK ANKUNo ratings yet

- Law School Survival Guide (Volume I of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Torts, Civil Procedure, Property, Contracts & Sales: Law School Survival GuidesFrom EverandLaw School Survival Guide (Volume I of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Torts, Civil Procedure, Property, Contracts & Sales: Law School Survival GuidesNo ratings yet

- Soccer (Football) Contracts: An Introduction to Player Contracts (Clubs & Agents) and Contract Law: Volume 2From EverandSoccer (Football) Contracts: An Introduction to Player Contracts (Clubs & Agents) and Contract Law: Volume 2No ratings yet

- Criminal Process PromptDocument3 pagesCriminal Process Promptlee tranNo ratings yet

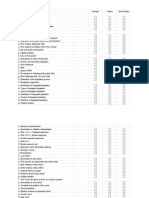

- A-Level Law Checklist - Sheet1Document12 pagesA-Level Law Checklist - Sheet1lee tranNo ratings yet

- Topic 2 OnlyDocument1 pageTopic 2 Onlylee tranNo ratings yet

- Wilden HusDocument3 pagesWilden HusValiant Aragon DayagbilNo ratings yet

- Case 17 - Kalaw vs. FernandezDocument1 pageCase 17 - Kalaw vs. FernandezJarvelNo ratings yet

- Delta Motors Vs CA 276 SCRA 212 July 4, 1997Document2 pagesDelta Motors Vs CA 276 SCRA 212 July 4, 1997Ken TuazonNo ratings yet

- Santos vs. BartolomeDocument2 pagesSantos vs. BartolomestrgrlNo ratings yet

- Angel Vs Aledo Full TextDocument4 pagesAngel Vs Aledo Full TextChristin Jireh NabataNo ratings yet

- Waite V Diversified Consultants Inc FDCPA TCPA Lawsuit FloridaDocument13 pagesWaite V Diversified Consultants Inc FDCPA TCPA Lawsuit FloridaghostgripNo ratings yet

- Doctrine:: de Leon, JR., J.Document2 pagesDoctrine:: de Leon, JR., J.Tootsie GuzmaNo ratings yet

- Simon v. CHRDocument2 pagesSimon v. CHRLexNo ratings yet

- Faculty of Arts, Business and Social Sciences - Assessment Brief For Students - 2021/22Document31 pagesFaculty of Arts, Business and Social Sciences - Assessment Brief For Students - 2021/22diamond WritersNo ratings yet

- Partnership Act 1961Document15 pagesPartnership Act 1961Khairul Idzwan100% (8)

- FLORANTE VITUG, Petitioner, vs. EVANGELINE A. ABUDA, Respondent. G.R. No. 201264 - January 11, 2016 - LEONEN, JDocument2 pagesFLORANTE VITUG, Petitioner, vs. EVANGELINE A. ABUDA, Respondent. G.R. No. 201264 - January 11, 2016 - LEONEN, JJosiah Balgos100% (1)

- Jesse U. Lucas V Jesus S. Lucas G.R. No. 190710 June 6, 2011 FactsDocument2 pagesJesse U. Lucas V Jesus S. Lucas G.R. No. 190710 June 6, 2011 FactsMichelle Valdez AlvaroNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court DecisionDocument13 pagesSupreme Court DecisionHNNNo ratings yet

- The Waterfowl of Etruria A STDocument248 pagesThe Waterfowl of Etruria A STIeva NavickaitėNo ratings yet

- How To Take Patent in INDIA FinalDocument19 pagesHow To Take Patent in INDIA FinalnonsenseatulNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 78585 July 5, 1989Document2 pagesG.R. No. 78585 July 5, 1989Ruchie EtolleNo ratings yet

- General Concept of Penology, Corrections and Punishment PenologyDocument3 pagesGeneral Concept of Penology, Corrections and Punishment PenologyFrederick EboñaNo ratings yet

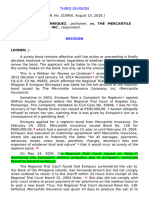

- Enriquez v. The Mercantile Insurance Co., IncDocument16 pagesEnriquez v. The Mercantile Insurance Co., IncJohn FerarenNo ratings yet

- Revised Rules On Evidence Comparative Matrix PDF FreeDocument43 pagesRevised Rules On Evidence Comparative Matrix PDF FreeCarmela Eloisa DullasNo ratings yet

- La Chemise Lacoste S.A. vs. Hon. Fernandez, Et Al. 214 Phil. 332, (1984)Document3 pagesLa Chemise Lacoste S.A. vs. Hon. Fernandez, Et Al. 214 Phil. 332, (1984)Roland MarananNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-32747 November 29, 1984 FRUIT OF THE LOOM, INC., Petitioner, Court of Appeals and General Garments CORPORATION, Respondents. Makasiar, J.Document4 pagesG.R. No. L-32747 November 29, 1984 FRUIT OF THE LOOM, INC., Petitioner, Court of Appeals and General Garments CORPORATION, Respondents. Makasiar, J.JVMNo ratings yet

- Iii. in Both of The Above Cases, The Capitalist-Industrial Partner Shall Not Share in The Losses in His Capacity As Industrial PartnerDocument4 pagesIii. in Both of The Above Cases, The Capitalist-Industrial Partner Shall Not Share in The Losses in His Capacity As Industrial PartnerEsto, Cassandra Jill SumalbagNo ratings yet

- Joson v. BaltazarDocument7 pagesJoson v. BaltazardingNo ratings yet

- PNCC Traffic v. PNCC, G.R. No. 171231, February 17, 2010Document1 pagePNCC Traffic v. PNCC, G.R. No. 171231, February 17, 2010Mary LeandaNo ratings yet

- Jung V McFarland ComplaintDocument21 pagesJung V McFarland ComplaintLaw&CrimeNo ratings yet

- Ramirez vs. MargalloDocument5 pagesRamirez vs. MargalloWreath An GuevarraNo ratings yet

Davies Essay ch10

Davies Essay ch10

Uploaded by

lee tranOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Davies Essay ch10

Davies Essay ch10

Uploaded by

lee tranCopyright:

Available Formats

Davies: JC Smith's The Law of Contract

Chapter 10, Question 1

Francis and Clare are friends. They decide to play the National Lottery each week. Each is to

contribute £3 and they will take it in turns to choose three sets of numbers. They agree that any

winnings are to be divided equally between the two of them and another friend, Doug. Doug

learns of this agreement and tells Clare that he is very happy and grateful for it. In the sixth week,

when Francis had chosen the numbers, one of the line of numbers chosen wins a prize of

£250,000. Francis, in whose name the ticket was registered, wishes to keep the prize. Advise

Francis as to his liability to Clare and to Doug.

The first issue to consider in the case of Francis (F), Clare (C), and Doug (D) is whether F and C have

created a valid contract. There appears to be a form of offer and acceptance where the terms of the

contract have been agreed. An area of uncertainty is the requirement of an intention to create legal

relations; F and C are friends and the agreement could therefore be of a social rather than a legal

nature. Balfour v. Balfour established that no intention to create legal relations would be found in

agreements between spouses. Jones v. Padavatton further established that an arrangement within

the family would not warrant a finding of an intention to create legal relations. It is more likely that

an agreement between two friends where they both contribute funds to a common endeavour

would mean that there is an intention to create legal relations. Both parties have provided

consideration in the form of the £3 contribution each week, and both parties are competent enough

to make a contract. It seems, therefore, that F and C have validly created a contract.

F’s liability to C is easier to determine. As a promisee who has provided consideration for the

contract in the form of £3 contributed for six weeks, C is entitled to enforce the contract that F will

breach by keeping the entire sum of £250,000. At the very least, C is entitled to one-third of the

money, around £83,333. The most appropriate remedy would be specific performance, ordering F to

pay the £83,333 to C as it was originally a term of the contract that the sum would be split between

F, C, and D. The other option would be an award of damages to C for the amount of £83,333 in order

to put C in the position she would be if the contract had been performed. Since C is a party to the

contract and has provided consideration for the contract, F is likely to be found liable to C in breach

of the contract.

The next issue to consider is whether D acquires any rights as a third party to the contract between F

and C. It is clear that both F and C have provided consideration for the contract in the form of the £3

they each contribute to play the National Lottery each week. D, on the other hand, is simply

informed of the gains he makes from this contract without making any financial contribution to the

contract. Under common law principles, consideration must flow from the promisee. Although D is a

promisee, he has not provided any consideration and therefore cannot enforce the promise. Only C,

who has provided consideration, would be able to enforce the promise under common law

principles.

D would therefore have to employ the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 in order to

determine whether he acquires a right to enforce any of the terms of the contract between F and C.

© Oxford University Press, 2021.

Davies: JC Smith's The Law of Contract

Section 1(1)(a) and (b) of the Act state that a third party can enforce a term of a contract if the

contract expressly provides that he may or the term purports to confer a benefit on him, unless it

appears that on a proper construction of the contract it appears that the parties did not intend for

the term to be enforceable by a third party. The term of the contract that specifies that the money

will be split equally between F, C, and D certainly purports to confer a benefit on D. However, it must

be considered whether, as per s 1(2) of the Act, on the proper construction of the contract it appears

that the parties did not intend for the term to be enforceable by the third party. Nothing in the facts

suggests that F and C did not intend the term to be enforceable by D. F and C mutually agree that D

will receive a share of the money. C knows that D is aware of the term of the contract and makes no

statement suggesting that D is not meant to be able to enforce the term. Section 1(3) of the Act

states that the third party must be identified by name, as a member of a class, or as answering a

particular description. It seems to be agreed expressly that the money will be divided equally

between F, C, and D. As far as these sections of the Act state, therefore, it appears that D is entitled

to enforce the term that states that he will receive an equal share of the £250,000.

With no relevant defences to D’s claim, it is therefore submitted that F is liable to D in breach of the

term of the contract stipulating that D would receive the £83,333. Section 1(5) of the 1999 states

that once the third party is able to enforce the term of the contract, any remedy that would be

available to the third party in an action for a breach of contract had he been a party to the contract

will be available to enforce the term in question. D would therefore be entitled to the same

remedies that C was entitled to. Either specific performance would be ordered, forcing F to pay the

£83,333 owed to D. On the other hand, there may be an award of damages of £83,333 instead to

place D in the position he would have been had the contract not been breached by F.

It is submitted, therefore, that F would be liable for the original stipulated amount (one-third of

£250,000) to C and D respectively.

Overall essay feedback: Good on the core issues, with some very clear and persuasive analysis. It is

a shame that you don’t discuss the Panatown – type issues at all, which are both important and

interesting. As a result, this answer would be unlikely to score higher than a mid-2.i in the exam.

© Oxford University Press, 2021.

Davies: JC Smith's The Law of Contract

Chapter 10, Question 2

Sissy hires Rayburn Ltd to transport her grand piano from Nottingham to Devon. She pays Rayburn

Ltd £1,500 for this service. The contract includes the following two clauses:

(a) Rayburn Ltd may employ independent contractors to perform any part of this service.

(b) Liability for any damage to the piano during transportation will be limited to £5,000.

Rayburn Ltd hires Eric to transport the piano. Unfortunately, the piano is damaged by the negli-

gence of Eric during the transport, causing damage to the value of £12,000.

Advise Sissy.

Sissy (S) can potentially bring a claim against Rayburn Ltd (R) or Eric (E) for the damage caused to her

grand piano, in contract or in tort, but is likely to have to choose between either one as she will not

be granted double recovery. The biggest problem that S is likely to face in any claim she brings is

enforcement of the limitation of liability clause contained within her contract with R.

(i) S’ claim against R

S and R are the main contractors and have a contractual relationship. R is likely to be liable for the

damage caused to S’ piano under an express (or implied) term in the contract. The difficulty with

bringing a claim against R is that on the face of the contract, R’s liability for any damage to the piano

during transportation is limited to £5,000, whereas the actual damage caused is to the value of

£12,000, and S will want to recover as much as possible.

(ii) S’ claim against E

S will have better chances of recovering the full £12,000 in a claim against E. As there is no direct

contractual relationship between S and E, S may bring a claim in e.g. the tort of negligence. E may

seek to rely on the limitation clause. However, since he is a third party and is not privy to the

contract, the question is whether he may do so, under statute or the common law.

Contract (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999

(a) Whether the Act applies

E may be able to enforce the contract term in his own right under the 1999 Act. The Act applies only

to contracts made between 11 November 1999 and 11 May 2000 which expressly provide that it

should apply, and contracts made on or after the latter date. If the contract between S and R was

made before the date the Act came into force, E will not be able to rely on the Act to enforce the

limitation clause. The same is true if elsewhere in the contract, S and R have expressly excluded the

Act’s operation. We have no information regarding the date of contract formation nor on any

express terms excluding the Act, therefore it is assumed that this is not an issue here.

s.6 also lists cases where s.1 would not confer rights on a third party. It is unlikely that any of the

exceptions apply to exclude the operation of the Act. In particular, although the contract appears to

© Oxford University Press, 2021.

Davies: JC Smith's The Law of Contract

be a contract of service (potentially falling within the definition of a contract of employment, s.6(4)),

E is not seeking to enforce a right against an employee or a worker (neither R nor S can be classified

as such). Further, even if the contract was a carriage of goods contract as defined by s.6(5) and (6),

which is unlikely, since it concerns only a service to transport the piano within the UK and is

therefore unlikely to be subject to the rules of international transport convention, the Act expressly

states that a third party may still avail himself of an exclusion or limitation of liability clause in such a

contract, which is the case here. It is very likely that the Act applies to the contract between S and R.

(b) Whether E has acquired a right to enforce a term of the contract

The next issue is whether E can enforce a term of the contract in his own right. s.1 of the Act

contains two tests of enforceability, stating that, subject to the provisions of the Act, E may in his

own right enforce a term of the contract if the contract expressly provides that he may (s.1(1)(a)), or

the term purports to confer a benefit on him (s.1(1)(b), subject to s.1(2)). E is unlikely to be able to

rely on s.1(1)(a) since the contract does not expressly say that E (or ‘a third party’) can rely on the

limitation clause.

However, E may be able to enforce the limitation clause under s.1(1)(b), since the document is to be

read as a whole, and clause (a) of the contract states that R may employ independent contractors to

perform the contract. s.1(1)(b) only raises a rebuttable presumption, and rebutted where the parties

did not intend to confer the benefit to E. Subsequent cases such as Nisshin v Cleaves, and The

Laemthong Glory (No.2) have demonstrated that it is a strong presumption and is difficult to rebut.

Given that the facts do not indicate a strong intention by S and R that E (or another third party)

should not be able to enforce the term, the enforceability test under s.1(1)(b) is likely to be satisfied.

s.1(3) of the Act does not require that E is expressly identified in the contract by name; it is sufficient

that he is identified as a member of a class, or as answering to a particular description (i.e. an

‘independent contractor’ employed by R to perform this particular service, under clause (a) of the

contract).

Finally, s.1(6) of the Act provides that clause (b), a limitation clause, can be relied upon by a third

party, envisaging that it will be easier to protect employees, subcontractors and so on under

exclusion or limitation of liability clauses.

Under the Act, it is highly likely that E will be able to enforce the limitation clause for his benefit,

meaning that any damages recovered by S from either R or E will be limited to £5,000.

The common law position

Another legal avenue through which E may seek to limit his liability is at common law. s.7(1) of the

Act states that s.1 does not affect any right or remedy of a third party that exists or is available apart

from this Act.

© Oxford University Press, 2021.

Davies: JC Smith's The Law of Contract

The leading case is Scruttons v Midland Silicones, where similarly a third party sought to rely on a

limitation clause. The House of Lords held that a third party (e.g. E) cannot rely on a contract

between S and R as a shield if one of the parties sues him.

The Privy Council in The Eurymedon circumvented the decision in Scruttons by holding that a third

party, such as E, may be able to rely on the limitation clause if the court finds a unilateral contract

between S and E. This does not create an exception to privity since the court would be looking at a

contract which E is privy to. However, the Eurymedon principle does not apply to all situations. In the

case itself, the court found a unilateral contract providing that, in return for the stevedores

unloading the goods, the shipper excluded the stevedores from liability for negligently damaging the

goods, (unless the action was brought within a year). The contract clearly provided that e.g.

servants, agents and independent contractors are to have the benefit of the limitations contained in

that contract. Although there is a clause here envisaging that third parties would perform the

contract, the limitations have not been expressly extended to E. Moreover, The Eurymedon principle

applies in the context of a carriage of goods by sea (which is not likely to be the case here, as the

piano was only being transported from Nottingham to Devon). E is unlikely to be able to rely on The

Eurymedon to avoid the ruling in Scruttons, and therefore under common law, he cannot take

advantage of the contract between S and R by way of defence.

In conclusion, both R (as a contracting party) and E (as a third party relying on the 1999 Act) are

likely to be able to limit their liability to S, unless S is able to show under s.1(2) that neither party

intended to confer a benefit to E under the contract.

Overall essay feedback: Good – you spot the key issues and deal with them well. You just seem to

make a bit of a meal of a couple of easy issues, which squeezes the time and space you have to

explore some of the harder and more interesting points. As a result, this answer may just fall short

of being First Class.

© Oxford University Press, 2021.

You might also like

- CHAPTER 1 - General Provisions On Contracts (Arts. 1305-1317)Document20 pagesCHAPTER 1 - General Provisions On Contracts (Arts. 1305-1317)Kim Deiparine85% (20)

- BLAW Quiz in General ProvisionsDocument3 pagesBLAW Quiz in General ProvisionsWyn DignosNo ratings yet

- ContractsDocument4 pagesContractsMschocokisses Shane Sison ÜNo ratings yet

- Document FileDocument1,310 pagesDocument Filelee tranNo ratings yet

- Civ2 QuizDocument13 pagesCiv2 QuizAce Roncalli Jereza Velasco100% (1)

- CasesDocument4 pagesCasesSheldonNo ratings yet

- Breach of Contract Problem Question and SolutionDocument5 pagesBreach of Contract Problem Question and SolutionGovnyoNo ratings yet

- Promoter AgreementDocument3 pagesPromoter Agreementyashvi bansalNo ratings yet

- USA V Kent Hovind Trial Transcripts (1 of 8)Document81 pagesUSA V Kent Hovind Trial Transcripts (1 of 8)AlbertFrank55No ratings yet

- Private Complaint Format MMRDocument29 pagesPrivate Complaint Format MMRMOHAN REDDY100% (1)

- Privity of Contract and Third Party RightsDocument9 pagesPrivity of Contract and Third Party RightsLaraib ShahidNo ratings yet

- Beatson Burrows CartwrightDocument62 pagesBeatson Burrows CartwrightMahdi Bin MamunNo ratings yet

- Privity of ContractDocument5 pagesPrivity of ContractOwuraku Amoako-AttahNo ratings yet

- Discharge JoooDocument4 pagesDischarge Jooopaco kazunguNo ratings yet

- Privity of ContractDocument2 pagesPrivity of ContractShraddhaNo ratings yet

- Review Notes - Contracts, Natural Obligations and Damages 2014Document22 pagesReview Notes - Contracts, Natural Obligations and Damages 2014JanetGraceDalisayFabrero100% (1)

- LEGT 1710: Assignment 2Document8 pagesLEGT 1710: Assignment 2timeflies23No ratings yet

- Chapter 4 LLB Contract Law Worksheet 3 BreakdownDocument33 pagesChapter 4 LLB Contract Law Worksheet 3 Breakdownماتو اریکاNo ratings yet

- Cat 2 Law of ContractDocument3 pagesCat 2 Law of ContractMorganNo ratings yet

- Contracts CH1Document4 pagesContracts CH1Bea Dela PeniaNo ratings yet

- Ngi Contract 1 - 125956Document7 pagesNgi Contract 1 - 125956gnanguni7No ratings yet

- ObliconDocument4 pagesObliconRam BeeNo ratings yet

- Third Party Rights: Beswich V BeswichDocument4 pagesThird Party Rights: Beswich V Beswichnicole camnasio100% (1)

- Doctrine of Privity of Contract Under Contract LawDocument18 pagesDoctrine of Privity of Contract Under Contract Lawdebanga borpujari100% (1)

- Definitions LawDocument10 pagesDefinitions LawNikki RunesNo ratings yet

- Contract eDocument8 pagesContract erajzarmy009No ratings yet

- Gen Prov ContDocument9 pagesGen Prov Contooagentx44No ratings yet

- Study Guide LawDocument2 pagesStudy Guide LawAngela DimituiNo ratings yet

- Discharge of Contract (RPT)Document4 pagesDischarge of Contract (RPT)Basim ZiaNo ratings yet

- Mod9 ItlDocument29 pagesMod9 ItlCoco PimentelNo ratings yet

- Mod9 (Itl)Document27 pagesMod9 (Itl)Tiara LlorenteNo ratings yet

- Civ2 QuizDocument12 pagesCiv2 Quizanon_258621924No ratings yet

- Article 1305 1422 Group 5 FinalDocument174 pagesArticle 1305 1422 Group 5 Finalacem16098No ratings yet

- STUDY GUIDE Pages 329 330 369 370 387Document7 pagesSTUDY GUIDE Pages 329 330 369 370 387Jhonielyn Regalado Ruga100% (3)

- Doctrine of Privity Contract With Case Laws AND ExceptionsDocument21 pagesDoctrine of Privity Contract With Case Laws AND Exceptionstuka IASNo ratings yet

- ASS 5-Reviewer in Midterm Law On Obligations and ContractsDocument9 pagesASS 5-Reviewer in Midterm Law On Obligations and ContractsRev Richmon De ChavezNo ratings yet

- Privity of ContractDocument6 pagesPrivity of ContractAbdul sami bhuttoNo ratings yet

- Law of Contract: ConsiderationDocument19 pagesLaw of Contract: ConsiderationJacob Black100% (1)

- Module 3 - ContractsDocument21 pagesModule 3 - ContractsKoji Brian ReyesNo ratings yet

- Sample Bar Questions With Answers ObliconDocument12 pagesSample Bar Questions With Answers ObliconJen Quilaquil - AlicanNo ratings yet

- Business LawDocument10 pagesBusiness LawKeshvin SidhuNo ratings yet

- Business Law Week 4 (Essential of A Valid Contract)Document27 pagesBusiness Law Week 4 (Essential of A Valid Contract)240450282No ratings yet

- 1styr 1stF ObliCon 2324Document21 pages1styr 1stF ObliCon 2324Yazzy2No ratings yet

- Contract LawDocument7 pagesContract LawVINCENT CHUANo ratings yet

- Reviewer ContractsDocument6 pagesReviewer ContractsBernard de AsisNo ratings yet

- Lecture 13 InterpretationDocument2 pagesLecture 13 InterpretationKeith San PedroNo ratings yet

- Sushant Lalla (57) - INDEMNITYDocument2 pagesSushant Lalla (57) - INDEMNITYSushant LallaNo ratings yet

- FinaDocument10 pagesFinaAnena AlbrightNo ratings yet

- SLL Contract Assignment Grp. 2Document29 pagesSLL Contract Assignment Grp. 2Jacob komba EllieNo ratings yet

- Contracts For The Benefit of Third PartiesDocument16 pagesContracts For The Benefit of Third PartiesErique Li-Onn PhangNo ratings yet

- Andersons Business Law and The Legal Environment Comprehensive Volume 23rd Edition Twome Solutions Manual DownloadDocument6 pagesAndersons Business Law and The Legal Environment Comprehensive Volume 23rd Edition Twome Solutions Manual DownloadJuan Davidson100% (24)

- Article 1315 and 1316Document8 pagesArticle 1315 and 1316Janeiro Brix GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Contract Act LawDocument8 pagesContract Act Lawmukmin09No ratings yet

- Oblicon 4Document5 pagesOblicon 4Borgonia, Khryzlin May C.No ratings yet

- Privity of Contract: Generally in Common LawDocument5 pagesPrivity of Contract: Generally in Common LawMikhail EremenkoNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 8 (Unenforceable Contracts)Document6 pagesCHAPTER 8 (Unenforceable Contracts)phoebe andamo67% (3)

- Doctrine of PrivityDocument6 pagesDoctrine of PrivityPJ 123No ratings yet

- Article 1366. There Shall Be No Reformation in The Following CasesDocument6 pagesArticle 1366. There Shall Be No Reformation in The Following CasesKhim Cortez100% (1)

- Law and Business Administration in Canada Canadian 13th Edition Smyth Test BankDocument22 pagesLaw and Business Administration in Canada Canadian 13th Edition Smyth Test Bankchristinawilliamsmprdegtjxz100% (33)

- The Privity of Contract DoctrineDocument5 pagesThe Privity of Contract DoctrinesivajibuddyNo ratings yet

- Week 6 Slides (Upsa)Document31 pagesWeek 6 Slides (Upsa)BISMARK ANKUNo ratings yet

- Law School Survival Guide (Volume I of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Torts, Civil Procedure, Property, Contracts & Sales: Law School Survival GuidesFrom EverandLaw School Survival Guide (Volume I of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Torts, Civil Procedure, Property, Contracts & Sales: Law School Survival GuidesNo ratings yet

- Soccer (Football) Contracts: An Introduction to Player Contracts (Clubs & Agents) and Contract Law: Volume 2From EverandSoccer (Football) Contracts: An Introduction to Player Contracts (Clubs & Agents) and Contract Law: Volume 2No ratings yet

- Criminal Process PromptDocument3 pagesCriminal Process Promptlee tranNo ratings yet

- A-Level Law Checklist - Sheet1Document12 pagesA-Level Law Checklist - Sheet1lee tranNo ratings yet

- Topic 2 OnlyDocument1 pageTopic 2 Onlylee tranNo ratings yet

- Wilden HusDocument3 pagesWilden HusValiant Aragon DayagbilNo ratings yet

- Case 17 - Kalaw vs. FernandezDocument1 pageCase 17 - Kalaw vs. FernandezJarvelNo ratings yet

- Delta Motors Vs CA 276 SCRA 212 July 4, 1997Document2 pagesDelta Motors Vs CA 276 SCRA 212 July 4, 1997Ken TuazonNo ratings yet

- Santos vs. BartolomeDocument2 pagesSantos vs. BartolomestrgrlNo ratings yet

- Angel Vs Aledo Full TextDocument4 pagesAngel Vs Aledo Full TextChristin Jireh NabataNo ratings yet

- Waite V Diversified Consultants Inc FDCPA TCPA Lawsuit FloridaDocument13 pagesWaite V Diversified Consultants Inc FDCPA TCPA Lawsuit FloridaghostgripNo ratings yet

- Doctrine:: de Leon, JR., J.Document2 pagesDoctrine:: de Leon, JR., J.Tootsie GuzmaNo ratings yet

- Simon v. CHRDocument2 pagesSimon v. CHRLexNo ratings yet

- Faculty of Arts, Business and Social Sciences - Assessment Brief For Students - 2021/22Document31 pagesFaculty of Arts, Business and Social Sciences - Assessment Brief For Students - 2021/22diamond WritersNo ratings yet

- Partnership Act 1961Document15 pagesPartnership Act 1961Khairul Idzwan100% (8)

- FLORANTE VITUG, Petitioner, vs. EVANGELINE A. ABUDA, Respondent. G.R. No. 201264 - January 11, 2016 - LEONEN, JDocument2 pagesFLORANTE VITUG, Petitioner, vs. EVANGELINE A. ABUDA, Respondent. G.R. No. 201264 - January 11, 2016 - LEONEN, JJosiah Balgos100% (1)

- Jesse U. Lucas V Jesus S. Lucas G.R. No. 190710 June 6, 2011 FactsDocument2 pagesJesse U. Lucas V Jesus S. Lucas G.R. No. 190710 June 6, 2011 FactsMichelle Valdez AlvaroNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court DecisionDocument13 pagesSupreme Court DecisionHNNNo ratings yet

- The Waterfowl of Etruria A STDocument248 pagesThe Waterfowl of Etruria A STIeva NavickaitėNo ratings yet

- How To Take Patent in INDIA FinalDocument19 pagesHow To Take Patent in INDIA FinalnonsenseatulNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 78585 July 5, 1989Document2 pagesG.R. No. 78585 July 5, 1989Ruchie EtolleNo ratings yet

- General Concept of Penology, Corrections and Punishment PenologyDocument3 pagesGeneral Concept of Penology, Corrections and Punishment PenologyFrederick EboñaNo ratings yet

- Enriquez v. The Mercantile Insurance Co., IncDocument16 pagesEnriquez v. The Mercantile Insurance Co., IncJohn FerarenNo ratings yet

- Revised Rules On Evidence Comparative Matrix PDF FreeDocument43 pagesRevised Rules On Evidence Comparative Matrix PDF FreeCarmela Eloisa DullasNo ratings yet

- La Chemise Lacoste S.A. vs. Hon. Fernandez, Et Al. 214 Phil. 332, (1984)Document3 pagesLa Chemise Lacoste S.A. vs. Hon. Fernandez, Et Al. 214 Phil. 332, (1984)Roland MarananNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-32747 November 29, 1984 FRUIT OF THE LOOM, INC., Petitioner, Court of Appeals and General Garments CORPORATION, Respondents. Makasiar, J.Document4 pagesG.R. No. L-32747 November 29, 1984 FRUIT OF THE LOOM, INC., Petitioner, Court of Appeals and General Garments CORPORATION, Respondents. Makasiar, J.JVMNo ratings yet

- Iii. in Both of The Above Cases, The Capitalist-Industrial Partner Shall Not Share in The Losses in His Capacity As Industrial PartnerDocument4 pagesIii. in Both of The Above Cases, The Capitalist-Industrial Partner Shall Not Share in The Losses in His Capacity As Industrial PartnerEsto, Cassandra Jill SumalbagNo ratings yet

- Joson v. BaltazarDocument7 pagesJoson v. BaltazardingNo ratings yet

- PNCC Traffic v. PNCC, G.R. No. 171231, February 17, 2010Document1 pagePNCC Traffic v. PNCC, G.R. No. 171231, February 17, 2010Mary LeandaNo ratings yet

- Jung V McFarland ComplaintDocument21 pagesJung V McFarland ComplaintLaw&CrimeNo ratings yet

- Ramirez vs. MargalloDocument5 pagesRamirez vs. MargalloWreath An GuevarraNo ratings yet