Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Trip To Jhari - February 23, 2008

A Trip To Jhari - February 23, 2008

Uploaded by

Tushar PundeCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Independent Testing Saves The Day: Case StudyDocument4 pagesIndependent Testing Saves The Day: Case StudyVinod MakaniNo ratings yet

- CoreLogic - Investor Day May 2010Document109 pagesCoreLogic - Investor Day May 2010as3122No ratings yet

- Meeting The Mahatma - Speech by DR Abhay BangDocument9 pagesMeeting The Mahatma - Speech by DR Abhay BangDeepak SalunkeNo ratings yet

- Village Immersion ReportDocument8 pagesVillage Immersion ReportRaghu Vinay100% (1)

- MD Story-Starvation DeathDocument3 pagesMD Story-Starvation DeathManoj DasNo ratings yet

- Maharogi Sewa Samiti: Baba Amte's Ashram: Indian Institute of Management AhmedabadDocument20 pagesMaharogi Sewa Samiti: Baba Amte's Ashram: Indian Institute of Management AhmedabadArchit GargNo ratings yet

- 16th Aug LinkDocument2 pages16th Aug LinkDebabrata MalickNo ratings yet

- Jeran - Velho - Meet Mejim Dususow, An ASHA Surviving at The Margins of India's Health SystemDocument7 pagesJeran - Velho - Meet Mejim Dususow, An ASHA Surviving at The Margins of India's Health SystemNandini VelhoNo ratings yet

- Anna Hazare Strategies in Mirror of Indian History: Colloquium Lab OnDocument21 pagesAnna Hazare Strategies in Mirror of Indian History: Colloquium Lab OnAbhinav PareekNo ratings yet

- Ecobiz Newsletter III IssueDocument4 pagesEcobiz Newsletter III IssuerutwikdphatakNo ratings yet

- Barangay Cabacnitan: Community SituationerDocument2 pagesBarangay Cabacnitan: Community SituationerAdrian OblenaNo ratings yet

- Conservation, Conflict and Creativity ExtendedDocument3 pagesConservation, Conflict and Creativity ExtendedAnil Gupta100% (1)

- Reading Assignment Case A The Sustainability DilemmaDocument3 pagesReading Assignment Case A The Sustainability DilemmaPrasamsa PNo ratings yet

- 4711-Article Text-8579-1-10-20220803Document8 pages4711-Article Text-8579-1-10-20220803anjelinamahtoNo ratings yet

- Impact of Recent....Document14 pagesImpact of Recent....Sandesh AhirNo ratings yet

- Shepherd 2019: St. Joseph's Institute of Management (JIM)Document19 pagesShepherd 2019: St. Joseph's Institute of Management (JIM)Nithish kannanNo ratings yet

- Book Review - Everyone Loves A Good DroughtDocument4 pagesBook Review - Everyone Loves A Good DroughtAnkit BhuptaniNo ratings yet

- Iess 202Document13 pagesIess 202Ravi ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Aaaaa RDocument20 pagesAaaaa RPppNo ratings yet

- Economics Chapter - 2 People As ResourcesDocument24 pagesEconomics Chapter - 2 People As ResourcesKanishka SharmaNo ratings yet

- Baba AmteDocument22 pagesBaba Amteujashree doleyNo ratings yet

- Anna HazareDocument10 pagesAnna HazareShilpa GowdaNo ratings yet

- A Good Way To Start Sai SevaDocument4 pagesA Good Way To Start Sai SevaDeepa HNo ratings yet

- Brij Ratan Parakh or Baba - Biography of An Unknown IndianDocument8 pagesBrij Ratan Parakh or Baba - Biography of An Unknown IndianKNOWLEDGE CREATORSNo ratings yet

- Knowing The True Taste of A Water 2013Document200 pagesKnowing The True Taste of A Water 2013Sara NayanNo ratings yet

- Profile of Dr. Achyuta Samanta 01.08.2019 PDFDocument2 pagesProfile of Dr. Achyuta Samanta 01.08.2019 PDFSai Kushi NNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneruship Success Against All OddsDocument4 pagesEntrepreneruship Success Against All OddsDr.K PaikNo ratings yet

- Identifying Our Own ProblemsDocument8 pagesIdentifying Our Own ProblemszerpthederpNo ratings yet

- Annexure 1 Community Develpoment: Submitted by Shreya MahajanDocument27 pagesAnnexure 1 Community Develpoment: Submitted by Shreya MahajanShreya MahajanNo ratings yet

- The Self Help Village-Jrd TataDocument8 pagesThe Self Help Village-Jrd TataSaurabh KrNo ratings yet

- KSK Report 3 All Equal in SufferingDocument3 pagesKSK Report 3 All Equal in Sufferingkausar s khanNo ratings yet

- SOP - Personal StatementDocument2 pagesSOP - Personal StatementDepepanshu MahajanNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument21 pagesUntitled Documentmanishamahto2004No ratings yet

- My Survey ExperienceDocument3 pagesMy Survey ExperienceJolly BiswasNo ratings yet

- Kalam Farewell SpeechDocument5 pagesKalam Farewell Speechvenkatdhokale100% (2)

- Rural Outrage Report Final BJDocument18 pagesRural Outrage Report Final BJVikram SinghNo ratings yet

- Dr. VArghese KurinDocument39 pagesDr. VArghese KurinprogrammerNo ratings yet

- Village Exposure Program - Report JSLPSDocument11 pagesVillage Exposure Program - Report JSLPSAbhishek KumarNo ratings yet

- The Link 15thdec'07Document2 pagesThe Link 15thdec'07Debabrata MalickNo ratings yet

- Babasaheb B.R. Ambedkar's Contribution To Nation BuildingDocument5 pagesBabasaheb B.R. Ambedkar's Contribution To Nation BuildingMukesh KumarNo ratings yet

- 11 Common Sense Less IndianDocument16 pages11 Common Sense Less IndianAmi Mce BhaskarNo ratings yet

- Population GrowthDocument3 pagesPopulation GrowthSheraz SarwarNo ratings yet

- Baba Amte Man Wit A MissionDocument1 pageBaba Amte Man Wit A MissionRavi BheriNo ratings yet

- Rural Life: Positive PointsDocument3 pagesRural Life: Positive PointsSreekanth PagadapalliNo ratings yet

- 02 Pe 27523Document13 pages02 Pe 27523ABHISHEK KUMARNo ratings yet

- 10 I Like What You Do, Burma Update (Mar 2010)Document6 pages10 I Like What You Do, Burma Update (Mar 2010)Thean Yong TeohNo ratings yet

- Iess 202Document13 pagesIess 202anand kumarNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Custard Apple Beneficiary (Srijan)Document38 pagesCase Study On Custard Apple Beneficiary (Srijan)Narendra ShandilyaNo ratings yet

- Assossiation For India'S DevelopmentDocument11 pagesAssossiation For India'S DevelopmentAID INDIA DELHI CHAPTERNo ratings yet

- Flip Class (People As A Resource)Document38 pagesFlip Class (People As A Resource)priya.gNo ratings yet

- Baba Amte InformationDocument3 pagesBaba Amte InformationSuhel PathanNo ratings yet

- The Green ReformerDocument6 pagesThe Green Reformeranudvkr11No ratings yet

- 30 Days Teaching Plan July Form 3Document20 pages30 Days Teaching Plan July Form 3Eugene JosephNo ratings yet

- Environmental Activist PDFDocument48 pagesEnvironmental Activist PDFTanaya BorseNo ratings yet

- Village Exposure ProgramDocument11 pagesVillage Exposure ProgramUddalak BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- ABDUL SATTAR EDHI-social WorkDocument4 pagesABDUL SATTAR EDHI-social WorkAOWN RAZA HASHMINo ratings yet

- Dams, Displacement, Policy and Law in India - World Bank GroupDocument118 pagesDams, Displacement, Policy and Law in India - World Bank GroupHarsh DixitNo ratings yet

- GREEN Village EnabaviDocument5 pagesGREEN Village EnabaviRamanjaneyulu GvNo ratings yet

- Speech of Sudha MurthyDocument3 pagesSpeech of Sudha Murthyapi-3840587100% (5)

- The Teacher and Child Labour by T. Vijayendra, 2009 Price Rs. 50Document32 pagesThe Teacher and Child Labour by T. Vijayendra, 2009 Price Rs. 50tv1943No ratings yet

- Its About KIDS: Information Summary About Incredible Institute in PanvanDocument13 pagesIts About KIDS: Information Summary About Incredible Institute in PanvanAmar KumarNo ratings yet

- ForfeitingDocument34 pagesForfeitingvandana_daki3941No ratings yet

- 5 6154396266370433283Document8 pages5 6154396266370433283Sing YingNo ratings yet

- Overview of Bond Sectors and InstrumentsDocument32 pagesOverview of Bond Sectors and InstrumentsShrirang LichadeNo ratings yet

- Mitc Credit CardsDocument31 pagesMitc Credit Cardsguru jeeNo ratings yet

- Capulong vs. CADocument13 pagesCapulong vs. CAdanexrainierNo ratings yet

- Al AwfarDocument14 pagesAl Awfarnadzirah samsuddinNo ratings yet

- Toeic 2007Document12 pagesToeic 2007honghue100% (2)

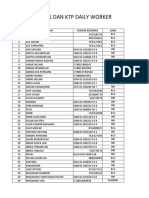

- Data Daily WorkerDocument4 pagesData Daily Workerzulmi07No ratings yet

- Cyber Laundering FinalDocument70 pagesCyber Laundering Finalsalman jamali100% (2)

- Final Project 3Document65 pagesFinal Project 3Riya GuptaNo ratings yet

- A Study On Credit Risk Management at Karnataka State Co-Operative Apex Bank Limited, Bengaluru PDFDocument71 pagesA Study On Credit Risk Management at Karnataka State Co-Operative Apex Bank Limited, Bengaluru PDFAstute ReportNo ratings yet

- Part A & BDocument6 pagesPart A & BRiya PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Igcse and o Level Accounting Revision GuideDocument10 pagesCambridge Igcse and o Level Accounting Revision GuideSlome HackNo ratings yet

- Finance: Security BrokerageDocument22 pagesFinance: Security BrokerageCaren Que ViniegraNo ratings yet

- PLJ Volume 47 Number 2 - 02 - Ruben F. Balane Civil Law - Part TwoDocument16 pagesPLJ Volume 47 Number 2 - 02 - Ruben F. Balane Civil Law - Part TwoTidong Christian BryannNo ratings yet

- Spa Lpfo AndrewDocument11 pagesSpa Lpfo AndrewnashapI100% (2)

- Questions and Answers About Uncurrent and Mutilated CoinsDocument2 pagesQuestions and Answers About Uncurrent and Mutilated CoinsscriNo ratings yet

- A Study of Debit Card in Indian Scenario - SPDocument8 pagesA Study of Debit Card in Indian Scenario - SPSandip PatilNo ratings yet

- Account Statement: 0212482892 Chennai - MadippakkamDocument2 pagesAccount Statement: 0212482892 Chennai - MadippakkamAJAYNo ratings yet

- Medical Services Recruitment Board (MRB) : Government of Tamil Nadu, Chennai - 6. Website: WWW - MRB.TN - Gov.inDocument19 pagesMedical Services Recruitment Board (MRB) : Government of Tamil Nadu, Chennai - 6. Website: WWW - MRB.TN - Gov.inguruyasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 The Structure of A BankDocument5 pagesChapter 8 The Structure of A BankMohamad Alfianur SahriNo ratings yet

- Apollo Pharmacy Standard TCDocument2 pagesApollo Pharmacy Standard TCKaushikNo ratings yet

- Idbi Bank ProjectDocument109 pagesIdbi Bank Projectvishvak100% (7)

- A Brief Chronology of Events in Banking IndustryDocument5 pagesA Brief Chronology of Events in Banking Industryranjitmnit09No ratings yet

- Assignment 2 ACFAR 1231 Bank ReconciliationDocument3 pagesAssignment 2 ACFAR 1231 Bank ReconciliationkakaoNo ratings yet

- Change of Name Request FormDocument2 pagesChange of Name Request FormDinesh Rishi BhogaNo ratings yet

- 2023 03 02 20 32 56nov 22 - 486001Document6 pages2023 03 02 20 32 56nov 22 - 486001Nagendra Singh PariharNo ratings yet

- NSEP Case Study Over ViewDocument2 pagesNSEP Case Study Over ViewRaj RNo ratings yet

A Trip To Jhari - February 23, 2008

A Trip To Jhari - February 23, 2008

Uploaded by

Tushar PundeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Trip To Jhari - February 23, 2008

A Trip To Jhari - February 23, 2008

Uploaded by

Tushar PundeCopyright:

Available Formats

A Trip to Jhari February 23, 2008 Scandalous farmer suicide stories broke in the local papers week after

r week while I was at Anandwan in 2005 and 2006. Baba always considered himself to be a farmer at heart and he was visibly upset. He fretted non-stop and expressed his frustration at not being able to help. In a younger, more able body, he would have not wasted a minute. Every time, he read of yet another public relations photo opportunity where politicians promised some scheme but no benefit reached the farmer, he would get absolutely furious. So much younger than Baba, I had come to expect nothing from politicians. Baba was not burdened by such cynicism. No, he was outraged that they werent rolling up their sleeves and coming up with practical solutions. Baba often proclaimed, If the majority remains silent for a very long time, it becomes the silenced majority And he wanted to raise a big fuss about this mess. Father and Son Every day, Dr. Vikas Amte, Babas older son, would climb up on his fathers bed for a daily touch-base. It was their ritual, father and son. Vikas would tell Baba about his day, and Baba would ask questions about this-and-that or so-and-so. Vikas deeply felt the pain of the farmers too. But his heavy responsibilities of running Maharogi Sewa Samiti, and caring for thousands of its residents, made it difficult for him to drop everything and take on a new endeavor. Vikas had this interesting habit of stapling the mornings newspapers so they would stay neat and aligned. Then he would mark articles in red ink and one of his staff members would cut them out and file them for him. I always joked with Vikas about his filing system because he could find any article in a few minutes even though he collected thousands. As the pile of articles about the farmers grew, the idea of doing something kept gnawing at father and son. It was around this time that Dr. Vikass son, Kaustubh Amte started taking over the day-to-day responsibilities of managing Anandwan. A Chartered Accountant by training, Kaustubh aligned the finances of the organization, and his wife, Pallavi, started putting human resources and other systems in place. Finally, Vikas was free. But it must have been a painfully difficult decision for him to move away from Anandwan and help the farmers of Yeotmal at a time when Babas health was deteriorating. Though Dr. Vikas Amte has been responsible for all of Anandwans growth and expansion over the past three decades, the public has always associated the project with Baba. When people dont like something like modern buildings replacing the old terracotta cottages, they usually find any easy scapegoat in Vikas. Still, he forged ahead all the same, serving the disenfranchised, day after day since he graduated medical school. Over the years, it made me sad to see Vikas not even get

credit for things that were purely his inventions the tube-wells, the biogas plants, the wild bird sanctuary, and the low-cost housing. Without Vikas bhau, Baba Amtes legacy would have been something we learned about in museums or books. Instead, it lives on altered to fit the times and the people it serves, but alive all the same. Thousands of students from schools and colleges visit Anandwan and attend the Somnath Youth Camps. These rural youth learn about values of service and solidarity that they dont get from television or Bollywood. Even on this trip, I saw a hundred impressionable medical students at a social service camp at Anandwan, and I made a mental note to thank Vikas. I wish he received more recognition for keeping Babas flame going. Talking about Babas ideas (or writing about them) is much easier than putting them in practice. And all his life, thats what Vikas has done. Yet, I couldnt help but notice that I got more kudos for writing my book, Wisdom Song: the Life of Baba Amte, than Dr. Vikas Amte has ever received for spending his entire lifetime implementing his fathers ideas. Of course, he is aware of the fact that his work has gone largely unnoticed. For his part, he uses caustic humor and sarcasm as defense mechanisms. My friend Dr. Vijaya Bapat says it reminds her of Saint Tukarams apt description of sugarcane, Hard and knotted from the outside - filled with lifegiving juice inside. Now he would set in motion this new endeavor for farmers so Baba could stop fretting. The Genesis of Jhari In the eastern district of Yeotmal in Maharashtra, only two hours from Anandwan, in the village of Mulgavan, Dr. Vikas Amte initiated the Jhari project on Gandhijis birthday, 2 October 2006. The Kolam tribe lives in this region-- they are part of the aborigine (adivisi) population of India. Their civilization closely resembles the Gonds. They speak Kolami, their own language, but they mix in quite a few Marathi words. Read more about the tribe. Coincidentally, around this time, Dr. Vikas met Pramod Bakshi, a recently-retired government official who worked in the audit department in Nagpur. Instead of spending a relaxed retirement in his home in Mumbai, Bakshi offered to join Dr. Vikas Amte to help the farmers in Yeotmal. For Bakshi, it was an opportunity to do something truly meaningful with his life. But he made this decision at great personal cost. His wife and daughters took the news hard. Even today, his granddaughter cries on the phone, Dariya (Bakshis pet-name because of his beard), when are you coming home? In Pramod Bakshi, I found a person who thinks of Dr. Vikas Amte as his guru, his mentor. Vikas most misunderstood statement is, Anandwan is the worlds biggest jail and Im the jailer. What he means, Bakshi explains, is that society is unable to accept people with leprosy so they live at Anandwan. But they would much rather be with their families. So in essence though there is no fence, they can never leave. They can never integrate into society. The prejudice against them is still too strong. So Anandwan is a prison of sorts. Most visitors are so shocked

by that comment. How can the son of Baba Amte call Anandwan the Forest of Joy a prison? But listening to Bakshi, I see that he understands Vikas perfectly. I wrote the rest of this narrative about the Jhari project based largely on Bakshis eloquent information session over several cups of tea. He also took us for a tour of the Jhari project and the photos we took are now online. By no means is this a comprehensive report on this relatively new MSS project. But Im hopeful it will inspire researchers to do a more thorough study of its impact. In the Words of Pramod Bakshi Pramod Bakshi said that first, before starting any work on the project, Vikas sent him to the tehsil office to get a list of all the farmers who have committed suicide and visit their homes. Bakshi met with 81 families and listened to their stories. He discovered that a complex web of reasons lead to suicide. Yes, it is true that the farmers are extremely dependent on money lenders. Cotton, also called white gold in this region, is the main crop they depend on. Only one crop can be grown in a year and if the rains dont come, the farmer cannot pay back the loans and incurs even more debt to feed his family. But thats not all Bakshi noticed. The villages he visited didnt have electricity for the most part, the roads were terrible, and the schools were inadequate. The system had failed, and as an ex-government official, Bakshi realized that the problems were much deeper than what the media could capture in 10 seconds of air-time or an 800-word editorial. For example, the farmers needed water infrastructure so they could store water and use it in the dry season. They needed to learn to farm without using fertilizers that ruined the soil rendering it unusable. They also needed to diversify beyond cotton. The tribal youth needed job opportunities and vocational training. There was no doctor for miles and no public health system in place. The government was offering (as of March 2008, it still offers) Rs. 1 Lakh (around $2500) to families in compensation when a farmer committed suicide. Bakshi was told that a few farmers committed suicide so their families could get the compensation from the government and pay back their debts. Some families were even faking the deaths to receive compensation. Dr. Vikas Amte suggested that MSS use a different approach. The team went doorto-door with the following life-affirming offer: If you agree to grow something besides cotton on a small percentage of your land this year, we will provide the seeds, the fertilizer, and even the labor to work the land. We will also bring students from the Anand Niketan College to teach you how to grow these crops every alternate Saturday. You keep all the profits from this joint venture. Well even help you sell it at market rates without paying brokerage fees and transportation costs. See for yourself the results and you can decide at the end of the experiment if they want to continue or go back to only growing cotton. Tired of their dependency on cotton (the price of cotton is set by the government at around Rs. 200 ($5) per quintile) and its long growing season, several farmers agreed to this proposition even though the lure of white gold here in very strong.

Bakshi said, The government has many schemes to help the poor but they are not always rooted in the real world. One scheme provides seeds but no know-how; another gives free gas cylinders but no replacements; a third offers them cattle but do you see any grass here? The solutions are well-intentioned but probably written by some bureaucrat who has never lived in Yeotmal district, or even met a Kolami tribal! Perched on a rocky hilly with young teakwood trees given to Maharogi Sewa Samiti by the state government, the project first only consisted of a few tents. Dr. Vikas Amte and Pramod Bakshi set up camp, roughing it out for several months with a team of cured leprosy patients from Anandwan till they could bring an excavator and other earth moving equipment to start cutting terraces into the hill. The two have worked together like brothers-in-arms, dealing with all kinds of difficulties. Early in the project, they coped with the worst kind of shock. Bakshi recounted that a contractor, hired to dig a well in a nearby village, used explosives with utter disregard for proper safety protocols, and a stone flew out of the well and hit a passing girl. She was killed on the spot. Dr. Vikas Amte, was furious and wanted the authorities to find the contractor and file charges against him. But girls family demanded that Maharogi Sewa Samiti provide compensation. Dr. Vikas Amte, though terribly upset, felt he could not use funds from a non-governmental organization to give money to the family. But he told the family that he would help in kind education, health care, vocational training resources, or housing improvements. But an angry mob had taken over, and was not willing to wait for justice from a contractor who had fled the scene. They threatened to kill Dr. Vikas Amte, Pramod Bakshi, and the cured leprosy patients who lived in the Jhari project. Everyone advised Dr. Vikas Amte to leave. They had already beaten up one of the project volunteers. No one wanted to stay. At this time, a very sick patient came for treatment. Everyone advised Vikas not to take the patient but he insisted. According to his Hippocratic Oath, he had a moral responsibility to serve the patient. But if this patient died, the mob outside would blame Dr. Vikas for yet another thing over which he had little or no control. Then bed-ridden nonagenarian Baba sent a message from Anandwan, Tell those who are afraid to come back. Ill go and stay in their place. After that, everyone agreed to stay. The patient recovered and the tide turned. Bakshi explained, The angry villagers realized that if there was anyone to blame it was the contractor. It was clear that Dr. Vikas Amte was in the business of saving lives not taking them. Because he did not run away in fear during this crisis, the villagers came to trust him. Bakshi added, Many apologized later for intimidating him. Baba had dealt with run-ins with violent crowds at his leprosy project at Somnath in the late 1960s, he visited Khalistani terrorists in the Golden Temple, and survived many dangerous encounters during the Narmada years, so though others were afraid, he instinctively knew that his son was right to stay and serve the sick

patient, regardless of the outcome. I liked Bakshis frankness in discussing the challenges of grassroots development work. His style is to lay down the facts, and see if you have the courage to accept the reality of the situation. Bakshi told us that several surrounding villages and hamlets have already benefited from the Jhari project. A farmer, who previously grew only cotton, started growing vegetables. When Baba was diagnosed with leukemia last fall, bouquets of flowers came from all over the country and the world. This farmer, Mohammed, made a breath-taking bouquet out of vegetables. Baba sent a message that the vegetable bouquet was more meaningful to him than the thousands of flower bouquets put together. Bakshi pointed out that when they arrived in Jhari, they had surveyed the local population to first find out what the needs were. Since then, they have invested in huge infrastructure projects and have spent a lot of money. Kaustubh Amte, ever the vigilant Chartered Accountant, reminds his father that they cannot break fixed deposits to fund this cash-hungry project. Building rainwater harvesting ponds, changing the agricultural practices of the farmers, and providing health care and vocational training isnt cheap. But Pramod Bakshi said to me wistfully, My guru, Dr. Vikas Amte told me that if you serve the people, the support will come. People will see the work. They will contribute generously. You dont worry. But we are not magicians, Bakshi added wistfully, even with all this back-breaking work, it will take five years to see the full results of our efforts. Babas Spirit Dances in Jhari Now As we drove away from the Jhari project, past red chilly fields and villagers riding their bicycles to the market, I felt Dr. Vikas Amte close at hand. Though he was thousands of miles away in Goa with his orchestra, his imprint was everywhere in Jhari: in the dome houses, in the blooming cabbage and cauliflower fields, in Prasanna grinning down from the excavator, in the rainwater harvesting ponds and the newly painted schoolhouse in the nearby village, in the deep bonds the project had forged with the locals Most of all, in the smiling faces of Pono, Maruti, and Dadarao Bhima Meshram, three farmers who were elated that their fields may soon have water through the dry season. Balu dropped us off at the guesthouse at Anandwan. I went over the Baba and Tais cottage. I stood by Babas bedroom door, which had the red letters, I.C.U. painted over it. For a moment, I imagined Vikas sitting on the bed chatting with Baba about his day. But the bed was empty. Baba passed away on February 9, 2008. It feels like he just stepped away, and will be back any minute. His walking stick, the White Tara thankga the Dalai Lama sent for his long life, his bed everything is still in its place. I arrived at Anandwan two weeks too late to meet Baba. While I was there, many visitors came in search of Baba Amtes Samadhi. And appropriately, Sadhana tai

has selected a banyan tree to be planted over his earthly remains. But I dont believe he is sleeping in his grave. When he visited Vikas new project in 2007, Baba said, After seeing this work, I have the desire to live another fifty years. The sheer speed at which that project has progressed leads me to believe that Baba, if hes looking on, is pleased as punch. Free from the spondylolysis that plagued his body since 1972, Baba Amtes spirit most likely dances in Jhari now. And late at night, after everyone else is sound asleep, Vikas still probably keeps his rendez-vous with his father, chitchatting about this-and-that or so-and-so under the breathtaking star-lit Jhari sky Photos from our trip to Jhari Video of Dr. Vikas Amte showing visitors around Anandwan (Part 1) and Part II

You might also like

- Independent Testing Saves The Day: Case StudyDocument4 pagesIndependent Testing Saves The Day: Case StudyVinod MakaniNo ratings yet

- CoreLogic - Investor Day May 2010Document109 pagesCoreLogic - Investor Day May 2010as3122No ratings yet

- Meeting The Mahatma - Speech by DR Abhay BangDocument9 pagesMeeting The Mahatma - Speech by DR Abhay BangDeepak SalunkeNo ratings yet

- Village Immersion ReportDocument8 pagesVillage Immersion ReportRaghu Vinay100% (1)

- MD Story-Starvation DeathDocument3 pagesMD Story-Starvation DeathManoj DasNo ratings yet

- Maharogi Sewa Samiti: Baba Amte's Ashram: Indian Institute of Management AhmedabadDocument20 pagesMaharogi Sewa Samiti: Baba Amte's Ashram: Indian Institute of Management AhmedabadArchit GargNo ratings yet

- 16th Aug LinkDocument2 pages16th Aug LinkDebabrata MalickNo ratings yet

- Jeran - Velho - Meet Mejim Dususow, An ASHA Surviving at The Margins of India's Health SystemDocument7 pagesJeran - Velho - Meet Mejim Dususow, An ASHA Surviving at The Margins of India's Health SystemNandini VelhoNo ratings yet

- Anna Hazare Strategies in Mirror of Indian History: Colloquium Lab OnDocument21 pagesAnna Hazare Strategies in Mirror of Indian History: Colloquium Lab OnAbhinav PareekNo ratings yet

- Ecobiz Newsletter III IssueDocument4 pagesEcobiz Newsletter III IssuerutwikdphatakNo ratings yet

- Barangay Cabacnitan: Community SituationerDocument2 pagesBarangay Cabacnitan: Community SituationerAdrian OblenaNo ratings yet

- Conservation, Conflict and Creativity ExtendedDocument3 pagesConservation, Conflict and Creativity ExtendedAnil Gupta100% (1)

- Reading Assignment Case A The Sustainability DilemmaDocument3 pagesReading Assignment Case A The Sustainability DilemmaPrasamsa PNo ratings yet

- 4711-Article Text-8579-1-10-20220803Document8 pages4711-Article Text-8579-1-10-20220803anjelinamahtoNo ratings yet

- Impact of Recent....Document14 pagesImpact of Recent....Sandesh AhirNo ratings yet

- Shepherd 2019: St. Joseph's Institute of Management (JIM)Document19 pagesShepherd 2019: St. Joseph's Institute of Management (JIM)Nithish kannanNo ratings yet

- Book Review - Everyone Loves A Good DroughtDocument4 pagesBook Review - Everyone Loves A Good DroughtAnkit BhuptaniNo ratings yet

- Iess 202Document13 pagesIess 202Ravi ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Aaaaa RDocument20 pagesAaaaa RPppNo ratings yet

- Economics Chapter - 2 People As ResourcesDocument24 pagesEconomics Chapter - 2 People As ResourcesKanishka SharmaNo ratings yet

- Baba AmteDocument22 pagesBaba Amteujashree doleyNo ratings yet

- Anna HazareDocument10 pagesAnna HazareShilpa GowdaNo ratings yet

- A Good Way To Start Sai SevaDocument4 pagesA Good Way To Start Sai SevaDeepa HNo ratings yet

- Brij Ratan Parakh or Baba - Biography of An Unknown IndianDocument8 pagesBrij Ratan Parakh or Baba - Biography of An Unknown IndianKNOWLEDGE CREATORSNo ratings yet

- Knowing The True Taste of A Water 2013Document200 pagesKnowing The True Taste of A Water 2013Sara NayanNo ratings yet

- Profile of Dr. Achyuta Samanta 01.08.2019 PDFDocument2 pagesProfile of Dr. Achyuta Samanta 01.08.2019 PDFSai Kushi NNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneruship Success Against All OddsDocument4 pagesEntrepreneruship Success Against All OddsDr.K PaikNo ratings yet

- Identifying Our Own ProblemsDocument8 pagesIdentifying Our Own ProblemszerpthederpNo ratings yet

- Annexure 1 Community Develpoment: Submitted by Shreya MahajanDocument27 pagesAnnexure 1 Community Develpoment: Submitted by Shreya MahajanShreya MahajanNo ratings yet

- The Self Help Village-Jrd TataDocument8 pagesThe Self Help Village-Jrd TataSaurabh KrNo ratings yet

- KSK Report 3 All Equal in SufferingDocument3 pagesKSK Report 3 All Equal in Sufferingkausar s khanNo ratings yet

- SOP - Personal StatementDocument2 pagesSOP - Personal StatementDepepanshu MahajanNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument21 pagesUntitled Documentmanishamahto2004No ratings yet

- My Survey ExperienceDocument3 pagesMy Survey ExperienceJolly BiswasNo ratings yet

- Kalam Farewell SpeechDocument5 pagesKalam Farewell Speechvenkatdhokale100% (2)

- Rural Outrage Report Final BJDocument18 pagesRural Outrage Report Final BJVikram SinghNo ratings yet

- Dr. VArghese KurinDocument39 pagesDr. VArghese KurinprogrammerNo ratings yet

- Village Exposure Program - Report JSLPSDocument11 pagesVillage Exposure Program - Report JSLPSAbhishek KumarNo ratings yet

- The Link 15thdec'07Document2 pagesThe Link 15thdec'07Debabrata MalickNo ratings yet

- Babasaheb B.R. Ambedkar's Contribution To Nation BuildingDocument5 pagesBabasaheb B.R. Ambedkar's Contribution To Nation BuildingMukesh KumarNo ratings yet

- 11 Common Sense Less IndianDocument16 pages11 Common Sense Less IndianAmi Mce BhaskarNo ratings yet

- Population GrowthDocument3 pagesPopulation GrowthSheraz SarwarNo ratings yet

- Baba Amte Man Wit A MissionDocument1 pageBaba Amte Man Wit A MissionRavi BheriNo ratings yet

- Rural Life: Positive PointsDocument3 pagesRural Life: Positive PointsSreekanth PagadapalliNo ratings yet

- 02 Pe 27523Document13 pages02 Pe 27523ABHISHEK KUMARNo ratings yet

- 10 I Like What You Do, Burma Update (Mar 2010)Document6 pages10 I Like What You Do, Burma Update (Mar 2010)Thean Yong TeohNo ratings yet

- Iess 202Document13 pagesIess 202anand kumarNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Custard Apple Beneficiary (Srijan)Document38 pagesCase Study On Custard Apple Beneficiary (Srijan)Narendra ShandilyaNo ratings yet

- Assossiation For India'S DevelopmentDocument11 pagesAssossiation For India'S DevelopmentAID INDIA DELHI CHAPTERNo ratings yet

- Flip Class (People As A Resource)Document38 pagesFlip Class (People As A Resource)priya.gNo ratings yet

- Baba Amte InformationDocument3 pagesBaba Amte InformationSuhel PathanNo ratings yet

- The Green ReformerDocument6 pagesThe Green Reformeranudvkr11No ratings yet

- 30 Days Teaching Plan July Form 3Document20 pages30 Days Teaching Plan July Form 3Eugene JosephNo ratings yet

- Environmental Activist PDFDocument48 pagesEnvironmental Activist PDFTanaya BorseNo ratings yet

- Village Exposure ProgramDocument11 pagesVillage Exposure ProgramUddalak BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- ABDUL SATTAR EDHI-social WorkDocument4 pagesABDUL SATTAR EDHI-social WorkAOWN RAZA HASHMINo ratings yet

- Dams, Displacement, Policy and Law in India - World Bank GroupDocument118 pagesDams, Displacement, Policy and Law in India - World Bank GroupHarsh DixitNo ratings yet

- GREEN Village EnabaviDocument5 pagesGREEN Village EnabaviRamanjaneyulu GvNo ratings yet

- Speech of Sudha MurthyDocument3 pagesSpeech of Sudha Murthyapi-3840587100% (5)

- The Teacher and Child Labour by T. Vijayendra, 2009 Price Rs. 50Document32 pagesThe Teacher and Child Labour by T. Vijayendra, 2009 Price Rs. 50tv1943No ratings yet

- Its About KIDS: Information Summary About Incredible Institute in PanvanDocument13 pagesIts About KIDS: Information Summary About Incredible Institute in PanvanAmar KumarNo ratings yet

- ForfeitingDocument34 pagesForfeitingvandana_daki3941No ratings yet

- 5 6154396266370433283Document8 pages5 6154396266370433283Sing YingNo ratings yet

- Overview of Bond Sectors and InstrumentsDocument32 pagesOverview of Bond Sectors and InstrumentsShrirang LichadeNo ratings yet

- Mitc Credit CardsDocument31 pagesMitc Credit Cardsguru jeeNo ratings yet

- Capulong vs. CADocument13 pagesCapulong vs. CAdanexrainierNo ratings yet

- Al AwfarDocument14 pagesAl Awfarnadzirah samsuddinNo ratings yet

- Toeic 2007Document12 pagesToeic 2007honghue100% (2)

- Data Daily WorkerDocument4 pagesData Daily Workerzulmi07No ratings yet

- Cyber Laundering FinalDocument70 pagesCyber Laundering Finalsalman jamali100% (2)

- Final Project 3Document65 pagesFinal Project 3Riya GuptaNo ratings yet

- A Study On Credit Risk Management at Karnataka State Co-Operative Apex Bank Limited, Bengaluru PDFDocument71 pagesA Study On Credit Risk Management at Karnataka State Co-Operative Apex Bank Limited, Bengaluru PDFAstute ReportNo ratings yet

- Part A & BDocument6 pagesPart A & BRiya PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Igcse and o Level Accounting Revision GuideDocument10 pagesCambridge Igcse and o Level Accounting Revision GuideSlome HackNo ratings yet

- Finance: Security BrokerageDocument22 pagesFinance: Security BrokerageCaren Que ViniegraNo ratings yet

- PLJ Volume 47 Number 2 - 02 - Ruben F. Balane Civil Law - Part TwoDocument16 pagesPLJ Volume 47 Number 2 - 02 - Ruben F. Balane Civil Law - Part TwoTidong Christian BryannNo ratings yet

- Spa Lpfo AndrewDocument11 pagesSpa Lpfo AndrewnashapI100% (2)

- Questions and Answers About Uncurrent and Mutilated CoinsDocument2 pagesQuestions and Answers About Uncurrent and Mutilated CoinsscriNo ratings yet

- A Study of Debit Card in Indian Scenario - SPDocument8 pagesA Study of Debit Card in Indian Scenario - SPSandip PatilNo ratings yet

- Account Statement: 0212482892 Chennai - MadippakkamDocument2 pagesAccount Statement: 0212482892 Chennai - MadippakkamAJAYNo ratings yet

- Medical Services Recruitment Board (MRB) : Government of Tamil Nadu, Chennai - 6. Website: WWW - MRB.TN - Gov.inDocument19 pagesMedical Services Recruitment Board (MRB) : Government of Tamil Nadu, Chennai - 6. Website: WWW - MRB.TN - Gov.inguruyasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 The Structure of A BankDocument5 pagesChapter 8 The Structure of A BankMohamad Alfianur SahriNo ratings yet

- Apollo Pharmacy Standard TCDocument2 pagesApollo Pharmacy Standard TCKaushikNo ratings yet

- Idbi Bank ProjectDocument109 pagesIdbi Bank Projectvishvak100% (7)

- A Brief Chronology of Events in Banking IndustryDocument5 pagesA Brief Chronology of Events in Banking Industryranjitmnit09No ratings yet

- Assignment 2 ACFAR 1231 Bank ReconciliationDocument3 pagesAssignment 2 ACFAR 1231 Bank ReconciliationkakaoNo ratings yet

- Change of Name Request FormDocument2 pagesChange of Name Request FormDinesh Rishi BhogaNo ratings yet

- 2023 03 02 20 32 56nov 22 - 486001Document6 pages2023 03 02 20 32 56nov 22 - 486001Nagendra Singh PariharNo ratings yet

- NSEP Case Study Over ViewDocument2 pagesNSEP Case Study Over ViewRaj RNo ratings yet