Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Recognition of States Some Reflections On Doctrine and Practice

Recognition of States Some Reflections On Doctrine and Practice

Uploaded by

Patrick Sucre MumoCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Constitutions of Pakistan 1956 1962 1973Document2 pagesConstitutions of Pakistan 1956 1962 1973Farhan Farzand87% (78)

- Kinds of GovernmentsDocument9 pagesKinds of GovernmentsNoel IV T. Borromeo100% (2)

- American RealismDocument32 pagesAmerican RealismGauravKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Individuals As Subjects of International Law PDFDocument19 pagesIndividuals As Subjects of International Law PDFDank ShankNo ratings yet

- Part I The Concept of Statehood in International Law, Ch.1 Statehood and RecognitionDocument31 pagesPart I The Concept of Statehood in International Law, Ch.1 Statehood and RecognitionAnirudh Patwary100% (1)

- Defining Statehood, The Montevideo Convention and Its DiscontentsDocument57 pagesDefining Statehood, The Montevideo Convention and Its DiscontentsJeffrey L. OntangcoNo ratings yet

- Benton and Clulow - Legal EncountersDocument21 pagesBenton and Clulow - Legal EncountersMatthew KimaniNo ratings yet

- The Development of Conflicts LawDocument33 pagesThe Development of Conflicts LawAngela Louise SabaoanNo ratings yet

- Responsibility of States For Injuries To ForeignersDocument51 pagesResponsibility of States For Injuries To ForeignersADHEERA BINTI MOHD SALMI (MOE)No ratings yet

- 10 - Territory-In-International-LawDocument31 pages10 - Territory-In-International-LawecalotaNo ratings yet

- Universal International Law Nineteenth Century Histories of Imposition and AppropriationDocument78 pagesUniversal International Law Nineteenth Century Histories of Imposition and AppropriationAntonio UrrutiaNo ratings yet

- Difference and Deference in Treaty InterpetationDocument63 pagesDifference and Deference in Treaty InterpetationEdgar OdongoNo ratings yet

- Statehood 2Document31 pagesStatehood 2Willard Enrique MacaraanNo ratings yet

- Inter Unit I PDFDocument7 pagesInter Unit I PDFFaizan BhatNo ratings yet

- Public International Law Study MaterialDocument37 pagesPublic International Law Study Materialimro leathersNo ratings yet

- Nature and Origin of Int LawDocument22 pagesNature and Origin of Int Lawchirag agrawalNo ratings yet

- Colonialism and Its Impact On International Law, ID 216124 TWAILDocument10 pagesColonialism and Its Impact On International Law, ID 216124 TWAILMusharaf NazirNo ratings yet

- General Principles of International LawDocument29 pagesGeneral Principles of International LawDharu LilawatNo ratings yet

- British Yearbook of International Law-1977-Crawford-93-182 PDFDocument90 pagesBritish Yearbook of International Law-1977-Crawford-93-182 PDFzepedrobrNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of International Law: Colonial and Postcolonial RealitiesDocument6 pagesThe Evolution of International Law: Colonial and Postcolonial RealitiesAnanya100% (2)

- Private International Law or International Private LawDocument19 pagesPrivate International Law or International Private LawSAMIKSHA SHRIVASTAVANo ratings yet

- KOSKENNIEMI - What Use For SovereigntyDocument10 pagesKOSKENNIEMI - What Use For SovereigntyStefanoChiariniNo ratings yet

- The Elements of International LawDocument6 pagesThe Elements of International LawhidhaabdurazackNo ratings yet

- The Proper Law of The ContractDocument24 pagesThe Proper Law of The ContractrajNo ratings yet

- UWU Compiled 2Document75 pagesUWU Compiled 2Luzenne JonesNo ratings yet

- The Role of Positivism in The Development of International Law PDFDocument21 pagesThe Role of Positivism in The Development of International Law PDFShubhankar ThakurNo ratings yet

- A Phenomenological Theory of The Human Rights of The Alien: William E. Conklin University of Windsor (Ontario, Canada)Document57 pagesA Phenomenological Theory of The Human Rights of The Alien: William E. Conklin University of Windsor (Ontario, Canada)Mamatha RangaswamyNo ratings yet

- The Nature Origin and Development of IntDocument21 pagesThe Nature Origin and Development of IntShrinivas DesaiNo ratings yet

- Definition of Modern International LawDocument9 pagesDefinition of Modern International LawRohit YadavNo ratings yet

- International Law Notes - Dr. KabumbaDocument23 pagesInternational Law Notes - Dr. KabumbaNathan NakibingeNo ratings yet

- A Basic Introduction To The Sources of International Law: Ori PomsonDocument12 pagesA Basic Introduction To The Sources of International Law: Ori PomsonnheneNo ratings yet

- Alain Pellet - Badinter Comission ReviewDocument9 pagesAlain Pellet - Badinter Comission ReviewDumitru CazacNo ratings yet

- Jus Cogens PDFDocument27 pagesJus Cogens PDFshellahmayeNo ratings yet

- Genuine LinkDocument61 pagesGenuine Linksalehmagdy1999No ratings yet

- SSRN Id1877123Document15 pagesSSRN Id1877123Rishi Shrivastava100% (1)

- The Opinions of The Badinter Arbitration Committee 1-3Document8 pagesThe Opinions of The Badinter Arbitration Committee 1-3lonefrancNo ratings yet

- Atty Bagares PDFDocument188 pagesAtty Bagares PDFCarla VirtucioNo ratings yet

- Gordon A. Christenson, Jus Cogens: Guarding Interests Fundamental To International Society, 28 VA. J. INT'l L. 585 (1988) .Document65 pagesGordon A. Christenson, Jus Cogens: Guarding Interests Fundamental To International Society, 28 VA. J. INT'l L. 585 (1988) .Agent BlueNo ratings yet

- recognition-of-states-international-law-or-realpolitik-the-practice-of-recognition-in-the-wake-of-kosovo-south-ossetia-and-abkhaziaDocument24 pagesrecognition-of-states-international-law-or-realpolitik-the-practice-of-recognition-in-the-wake-of-kosovo-south-ossetia-and-abkhaziaAnton BilokonNo ratings yet

- Historical OverviewDocument8 pagesHistorical OverviewVishal kumarNo ratings yet

- The Sources of International LawDocument6 pagesThe Sources of International Lawshahzadjaved640No ratings yet

- Oundo Cj.Document21 pagesOundo Cj.Prince AgeNo ratings yet

- Nature - Development of 382 NotesDocument4 pagesNature - Development of 382 NoteslehlohonolomositijnrNo ratings yet

- International Legal PluralismDocument17 pagesInternational Legal PluralismIgnacio TorresNo ratings yet

- International Law and World War IDocument15 pagesInternational Law and World War IOzgur KorpeNo ratings yet

- Pil ReviewerDocument25 pagesPil ReviewerSamuel Johnson100% (1)

- Public International Law ReviewerDocument25 pagesPublic International Law Reviewermamp05100% (5)

- 17 Brit YBIntl L66Document17 pages17 Brit YBIntl L66Aishwarya BuddharajuNo ratings yet

- 13 - The Islamic Law of Nations and Its Place in TDocument19 pages13 - The Islamic Law of Nations and Its Place in TDupla PaltaNo ratings yet

- Injury To AliensDocument30 pagesInjury To AliensMamatha RangaswamyNo ratings yet

- 2006006060Document12 pages2006006060saad aliNo ratings yet

- Readings On Nationality and DomicileDocument16 pagesReadings On Nationality and DomicileSalex E. AliboghaNo ratings yet

- Transcivilizational v6-1 PDFDocument8 pagesTranscivilizational v6-1 PDFJuan Andrés TrianaNo ratings yet

- The Legal Significance The Declo Rations The General Assembly The United NationsDocument287 pagesThe Legal Significance The Declo Rations The General Assembly The United NationsRiya Shankar SharmaNo ratings yet

- Mediaocean 01Document8 pagesMediaocean 01Limon Md. KaykobadNo ratings yet

- Illegal Occupation Framing The Occupied Palestinian TerritoryDocument65 pagesIllegal Occupation Framing The Occupied Palestinian TerritoryDinaazouni100% (2)

- International Legal PersonalityDocument13 pagesInternational Legal PersonalityKajal RaiNo ratings yet

- 114 Penn Statim 34 PDFDocument7 pages114 Penn Statim 34 PDFabdul raufNo ratings yet

- Pax mundi: A concise account of the progress of the movement for peace by means of arbitration, neutralization, international law and disarmamentFrom EverandPax mundi: A concise account of the progress of the movement for peace by means of arbitration, neutralization, international law and disarmamentNo ratings yet

- The Law of the United Nations as Applied to Intervention Within the Frame Work of Article 2, Paragraph 7 of the Un Charter: A Comparative Analysis of Selected Cases to Establish the Underpinning Reality of the Danger of the Principles of Sovereign Equality and Domestic Jurisdiction Against Un Mandate for Total Humanity's Peaceful Co - Existence and Prosperity.From EverandThe Law of the United Nations as Applied to Intervention Within the Frame Work of Article 2, Paragraph 7 of the Un Charter: A Comparative Analysis of Selected Cases to Establish the Underpinning Reality of the Danger of the Principles of Sovereign Equality and Domestic Jurisdiction Against Un Mandate for Total Humanity's Peaceful Co - Existence and Prosperity.No ratings yet

- IPS Force CalibrationDocument4 pagesIPS Force CalibrationPatrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Guideline DKD-R 9-2Document9 pagesGuideline DKD-R 9-2Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Ds Force and Weight Measuring InstrumentsDocument73 pagesDs Force and Weight Measuring InstrumentsPatrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Wagstaff Homeworking Product Guide May 2020Document46 pagesWagstaff Homeworking Product Guide May 2020Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- SADIS User GuideDocument103 pagesSADIS User GuidePatrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

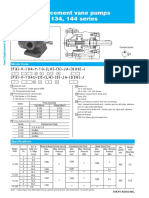

- Fixed Displacement Vane Pumps DatasheetDocument6 pagesFixed Displacement Vane Pumps DatasheetPatrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- BS en 1926Document20 pagesBS en 1926Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Department of Transportation: California Test 203 February 2008Document5 pagesDepartment of Transportation: California Test 203 February 2008Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Department of Transportation: California Test 202 November 2011Document20 pagesDepartment of Transportation: California Test 202 November 2011Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Fluide Ii D: Fluid For Automatic Transmissions and Hydraulic SystemsDocument1 pageFluide Ii D: Fluid For Automatic Transmissions and Hydraulic SystemsPatrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Department of Transportation: California Test 105 July 2012Document14 pagesDepartment of Transportation: California Test 105 July 2012Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- FSEL Flexural StrengthTesting Rev 00Document9 pagesFSEL Flexural StrengthTesting Rev 00Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Ideapad320-14ikb 320x-14ikb 320-14isk 320x-14isk HMM 201704Document82 pagesIdeapad320-14ikb 320x-14ikb 320-14isk 320x-14isk HMM 201704Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- GND PlaneDocument4 pagesGND PlanePatrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Historiography: How Far Does Alexander II Deserve The Title of Tsar Liberator'?Document2 pagesHistoriography: How Far Does Alexander II Deserve The Title of Tsar Liberator'?sofiaNo ratings yet

- Principality of SealandDocument1 pagePrincipality of SealandJay L Batiancila ContentoNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Paper FormatDocument11 pagesConceptual Paper FormatelijahNo ratings yet

- DYZENHAUS - Hobbes and The Legitimacy of LawDocument39 pagesDYZENHAUS - Hobbes and The Legitimacy of LawmehrbuchNo ratings yet

- The Role of Judiciary in The Constitutional Development of Pakistan (1947-1971)Document24 pagesThe Role of Judiciary in The Constitutional Development of Pakistan (1947-1971)FahadNo ratings yet

- Rights of A CitizenDocument45 pagesRights of A CitizenApoorvNo ratings yet

- Media LawDocument15 pagesMedia LawAditi IndraniNo ratings yet

- Ethiopia's Developmental State Model: A Reflection On Francis Fukuyama's ArticleDocument13 pagesEthiopia's Developmental State Model: A Reflection On Francis Fukuyama's ArticleAnonymous OdgFZrywoNo ratings yet

- Public AdministrationDocument14 pagesPublic AdministrationEjaz KazmiNo ratings yet

- Friedman Capitalism and FreedomDocument6 pagesFriedman Capitalism and FreedomYessica leyvaNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law Administrative LawDocument3 pagesConstitutional Law Administrative LawUtkarsh KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Ideology Security As National SecurityDocument14 pagesIdeology Security As National SecurityM Abdillah JundiNo ratings yet

- Parliamentary & Presidential Govt.Document14 pagesParliamentary & Presidential Govt.Royal Raj Alig100% (1)

- Ora John Reuter - Political Participation and The Survival of Electoral Authoritarian RegimesDocument37 pagesOra John Reuter - Political Participation and The Survival of Electoral Authoritarian RegimesMilos JankovicNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Democracy and RepublicDocument5 pagesDifference Between Democracy and RepublicAlvin Corpuz JrNo ratings yet

- Pengembangan KapasitasDocument7 pagesPengembangan KapasitasKhoirul RizalNo ratings yet

- Current Issues in The International Relations - 4th Week Analysis - Süha Mete KalenderDocument2 pagesCurrent Issues in The International Relations - 4th Week Analysis - Süha Mete KalenderSüha Mete KalenderNo ratings yet

- Aristotle's Politics - SummaryDocument2 pagesAristotle's Politics - SummaryIzabelaKaxniashviliNo ratings yet

- Hart - Rawls On Liberty and Its PriorityDocument23 pagesHart - Rawls On Liberty and Its Priorityגל דבשNo ratings yet

- State JurisdictionDocument2 pagesState JurisdictionNaeem ul mustafaNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes On DemocracyDocument7 pagesLecture Notes On DemocracygutterbcNo ratings yet

- Heldira Larashati - EAC Kyoto University (Geopolitical Economy of Development Term Assignment)Document3 pagesHeldira Larashati - EAC Kyoto University (Geopolitical Economy of Development Term Assignment)Heldira Larashati HaroenNo ratings yet

- Rousseau Spring 2021Document22 pagesRousseau Spring 2021Johnny KahaléNo ratings yet

- Networked Politics - A ReaderDocument238 pagesNetworked Politics - A ReaderÖrsan ŞenalpNo ratings yet

- Electoral System NotesDocument9 pagesElectoral System NotesAdei ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- 64 LawDocument2 pages64 LawJay TiwariNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Philippine Politics and Government PDFDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Philippine Politics and Government PDFAnonymous 1Pjqb2No ratings yet

- 1962 ConstitutionDocument22 pages1962 ConstitutionAbdul LatifNo ratings yet

Recognition of States Some Reflections On Doctrine and Practice

Recognition of States Some Reflections On Doctrine and Practice

Uploaded by

Patrick Sucre MumoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Recognition of States Some Reflections On Doctrine and Practice

Recognition of States Some Reflections On Doctrine and Practice

Uploaded by

Patrick Sucre MumoCopyright:

Available Formats

EDITORIAL COMMENT 113

titled to use loading and unloading machinery, etc., on the basis of agree

ments, concluded with the appropriate transportation and expeditionary

agencies” (Article 38, Soviet draft, Article 41, convention). But these

“ appropriate agencies” are Soviet-sponsored companies in Hungary, Ru

mania and Yugoslavia. These companies have varying degrees of Soviet

ownership, but always effective Soviet control; the general manager is in

all cases a Soviet citizen. These companies have been given privileged

treatment and special (in the case of Budapest, nearly exclusive) privi

leges; they dominate the Danube fleets in the various countries and have

obtained control of most of the useful ports and dock facilities. Thus,

Western shipping is at the mercy of these companies.

The United States, under these conditions, naturally rejected the con

vention and “ will not, of course, recognize for itself or for those ports of

Austria and Germany which are under its control, the authority of any

commission set up in this manner to exercise any jurisdiction in those por

tions of Austria and Germany.”

The Belgrade Conference is a failure as far as the Danube problem is

concerned. Although the convention will come into force among the seven

Eastern states, the Danube remains divided and dead. But there is even

more to it, which confirms the discouraging statement that international

law, as far as the laws of war and many other parts are concerned, is in a

deplorable state of retrogression. As Ambassador Cannon in his final re

jection stated, “ The Soviet attitude defeats and destroys the whole concept

of international waterways which has been the public law of Europe for

over 130 years.”

The Belgrade Conference presents the picture of a caricature of an inter

national conference under totalitarian domination. Last, though not least,

the Belgrade Conference has once more shown the crisis of our whole

Western Christian .culture, the danger of a new era of barbarism, by the

tremendous decline of good manners in diplomacy. Such decline is, as

Anthony Eden has stated, “ at the same time, one of the most troubling

factors in the present situation of the world.”

J osef L . K u n z

RECOGNITION OF STATES: SOME REFLECTIONS ON DOCTRINE AND PRACTICE

“ The recognition of a new state has been described as the assurance given

to it that it will be permitted to hold its place and rank in the character

of an independent political organism in the society of nations.” 1 The

practice of states demonstrates that the granting of recognition to a new

state is productive of juridical consequences in international law, but

i Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of State, Address before the Council on Foreign Rela

tions, Feb. 6,1931. Department o f State, Latin American Series, No. 4, p. 6.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2193138 Published online by Cambridge University Press

114 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW

doctrinal controversy has raged over the precise implications of the act of

recognition and the juridical status of the unrecognized state.2

Conceptualists, who, like Lauterpacht,3 Anzilotti,4 and Kelsen,5 start

from the premise that every juridical order, including international law,

must determine who are its subjects and at what point juridical personality

must be attributed to them, feel compelled by their own abstractions to

regard the act of recognition as constitutive—as creative of legal personality

in international law. Because international law possesses no central organ

to perform this “ legal” function of the establishment (la constatation)

of the “ legal fact” that a “ state-in-the-sense-of-international law” exists,

the function of recognition is attributed to each previously existing state

as an “ organ” of international law.6 Because, however, this decentralized

method of “ creating” new subjects of international law might lead to the

anomalous situation in which a new community is a state bound by inter

national law for recognizing states but not for others, it is convenient to

posit: (1) that international law contains rules stipulating the requirements

of statehood and (2) that there is a legal duty under international law to

recognize a community which meets these requirements of statehood.7 The

act of recognition thus becomes a “ legal” act in the dual sense of being

required of existing states by international law and of legally creating a

new subject of international law.

2 See, for example, H. Lauterpacht, Recognition in International Law (Cambridge

University, 1947); Josef L. Kunz, Die Anerhennung der Staaten und Regierungen im

Volkerrecht (1928); Sir John Fischer Williams, “ La Doctrine de la Reconnaissance en

Droit International et ses D6veloppements Recents,” 44 Academie de Droit International,

Recueil des Cours (1933), pp. 203-314; idem, “ Some Thoughts on the Doctrine of

Recognition in International Law,” 47 Harvard Law Review (1933-34), pp. 776-794;

Hans Kelsen, “ Recognition in International Law: Theoretical Observations,” this

J o u r n a l , Vol. 35 (1941), pp. 605-617, with comment by Philip Marshall Brown, ibid.,

Vol. 36 (1942), p. 106, and Edwin M. Borchard, ibid., p. 108; Annuaire de I’Institut de

Droit International, Paris, 1934, pp. 302-357 (Philip Marshall Brown, Rapporteur) and

Brussels, 1936, I, pp. 233-245, II, pp. 175-255, 300-305 (for English translation of reso

lutions adopted, see this J o u r n a l , Supp., Vol. 30 (1936), p. 185); Arnold Raestad, “ La

Reconnaissance Internationale des Nouveaux Mats et des Nouveaux Gouvernements,”

Revue de Droit International et de Legislation Comparee (3rd. Ser.), Vol. 17 (1936),

pp. 257-313; Louis L. Jaffe, Judicial Aspects of Foreign Relations, In Particular of the

Recognition of Foreign Powers (1933), Ch. II; Dionisio Anzilotti, Cours de Droit

International (trad. Gidel, 1929), Vol. I, pp. 159-177; Le Normand, La Reconnaissance

Internationale et ses Diverses Applications (1899).

3 Op. cit., p. 7 ff.

4Op. cit., p. 160 ff.

5Loo. cit., p. 606 ff.

8 See Lauterpacht, op. cit., p. 6; Kelsen, loc. cit., p. 607.

i Although both Lauterpacht, op. cit., p. 26 ff., and Kelsen, loc. cit., p. 607 ff., assert

that international law determines the requirements of statehood, Lauterpacht asserts and

Kelsen denies (loc. cit., p. 609 ff.) the duty to recognize a state which fulfills these

requirements. ,

https://doi.org/10.2307/2193138 Published online by Cambridge University Press

EDITORIAL COMMENT 115

Although it is possible to conclude, by induction from the practice of

states, that states achieving recognition possess people, territory, an ef

fective government, independence, and the capacity for international rela

tions, that same practice seems to indicate that states have no “ legal”

origin.8 A colony revolts or is permitted to secede from the parent country

and establishes its independent control over its territorial domain; or a

group of states and territories combine to form a new state {e.g., Yugo

slavia in 1918). No rules of international law prescribe or proscribe the

creation of such a new state; nor, except perhaps in the national juris

prudential theology, can the state be said to have had a “ legal” origin.

The origin of the Republic of the Philippines provides an instructive

example. On July 4, 1946, “ The United States of America and the Re

public of the Philippines, being animated by the desire . . . to provide

for the recognition of the independence of the Republic of the Philippines

as of July 4, 1946 and the relinquishment of American sovereignty over the

Philippine Islands,” signed at Manila a Treaty of General Relations,8 from

the Preamble of which the above words are taken, and which provides

further:

Article I. The United States of America agrees to withdraw and

surrender, and does hereby withdraw and surrender, all right of pos

session, supervision, jurisdiction, control or sovereignty existing and

exercised by the United States of America in and over the territory

and the people of the Philippine Islands, except the use of such bases,

necessary appurtenances to such bases, and the rights incident thereto,

as the United States of America, by agreement with the Republic of

the Philippines, may deem necessary to retain for the mutual protec

tion of the United States of America and of the Republic of the Philip

pines. The United States of America further agrees to recognize, and

does hereby recognize, the independence of the Republic of the Philip

pines as a separate self-governing nation and to acknowledge, and does

hereby acknowledge, the authority and control over the same of the

Government instituted by the people thereof, under the Constitution

of the Republic of the Philippines.

Article II. The diplomatic representatives of each country shall

enjoy in the territories of the other the privileges and immunities

derived from generally recognized international law and usage. . . .

Article III. Pending the final establishment of the requisite Philip

pine Foreign Service establishments abroad, the United States of

America and the Republic of the Philippines agree that at the request

of the Republic of the Philippines the United States of America will

endeavor, in so far as it may be practicable, to represent through its

Foreign Service the interests of the Republic of the Philippines in

countries where there is no Philippine representation. The two coun-

s Compare Louis Cavar4, “ La Reconnaissance de I’Mat et le Mandchoukouo, ’ ’ jRevue

Generate de Droit International Public, Vol. 42 (1935), pp. 5-99.

8 Department of State, Treaties and Other International Acts Series, No. 1568.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2193138 Published online by Cambridge University Press

116 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW

tries further agree that any such arrangements are to be subject to

termination when in the judgment of either country such arrangements

are no longer necessary.

Article VIII. This Treaty shall enter into force on the exchange of

instruments of ratification. . . .

It should be noted that although the Preamble states that one of the

purposes of the treaty was “ to provide for the recognition of the inde

pendence of the Republic of the Philippines as of July 4,1946, ’ ’ the obliga

tion assumed by the United States in Article I “ hereby” to “ withdraw and

surrender . . . sovereignty” and to “ recognize the independence of the

Republic of the Philippines as a separate self-governing nation” was not

legally effective, according to Article VIII, until October 22, 1946, the date

of the exchange of ratifications. It should also be noted that, by an “ In

terim Agreement Effected by Exchange of Notes, Signed at Manila, July

10 and 12, 1946, Effective July 4, 1946,” the United States and the Re

public of the Philippines agreed to observe the provisions of Articles II

and III of the Treaty, pending the final ratification thereof, in accordance

with the provisions of a Protocol signed July 4, 1946, to accompany the

Treaty and which had provided in part: “ It is understood and agreed that

pending final ratification of this Treaty, the provisions of Articles II and

III shall be observed by executive agreement.”

It would appear to be significant that the drafters of the Interim Agree

ment omitted to stipulate that Article I of the Treaty, providing for the

recognition of the Republic of the Philippines, should be observed as from

July 4, 1946. The implication would seem to be that by signing the

Treaty10 and concluding the Interim Agreement the United States had al

ready recognized the independence of the Republic.

No one will question the conclusion that it was the policy of the United

States which made possible the independence of her former colony, the

Philippine Islands. However, was statehood conferred on the Philippines

in any legal sense by United States recognition? I f the Republic of the

Philippines was not already a state prior to the signing of the agreements

on July 4, did she have the legal capacity to conclude agreements intended

to be governed by international law? I f statehood and the legal capacity

to conclude international agreements were conferred by the United States,

what is to prevent the United States from withdrawing them? It is sub

mitted that if the agreements were terminated, the question whether the

Republic of the Philippines was or was not an independent state would be

a question of fact, not of law.11 Similarly, although the policy of the United

10 Cf. Republic of China v. Merchant’s Fire Assurance Corporation o f New York

(1929), 30 Fed. 2d. 278.

11 Compare Wulfsohn v. Russian Socialist Federated Soviet Republic (1923), 234

N. Y. 372: “ Whether or not a government exists, clothed with the power to enforce its

https://doi.org/10.2307/2193138 Published online by Cambridge University Press

EDITORIAL COMMENT 117

States made it possible for the people of the Philippines to organize them

selves as a state, neither the United States nor international law “ created”

that state.

At this point troublesome theoretical questions recur: Is the new state

endowed with rights and obligations under international law at birth or

does it exist in a legal vacuum, without international legal rights and obliga

tions with respect to states which have not recognized it? Adherents of

the constitutive theory of recognition are logically forced to regard the

new state as without rights or obligations under international law until

recognized; although Lauterpacht attempts to minimize the embarrassment

by taking refuge in his conceptualism. To assert, he writes,12 that “ whether

a state exists is a question of fact” is “ to predicate that a given legal re

sult is a question of fact.” Jaffe,13 suggesting the pragmatic approach of

the foreign office when confronted with the emergence of a new state, ob

serves that:

. . . recognized statehood is but the completion of a process wherein

fact is informed by law, and where at any particular stage it may be

difficult to say whether a thing is so because it is the fact or because

it is the law . . . recognition does not create international personality

. . . there may be limited relationships, necessarily implying the state

hood of the parties, which do not rise to the dignity and completeness

of the relation between recognizant states.

Nascent states, however indeterminate their status politically or legally,

do not exist in a vacuum. Legal and political relations of varying intensity

with neighboring or more distant states are an immediate or inevitable

necessity and practice even prior to recognition.14 Although the pronounce

ments of foreign offices and judicial tribunals sometimes echo the constitu

tive theory, the practice of states of entering into “ unofficial” relations

with unrecognized states, of concluding international agreements with them,

of respecting their territorial limits, and of respecting their power to gov

ern and establish legal relationships within that territorial domain would

seem to be predicated, as Lauterpacht admits,15 upon the possession by the

unrecognized community of “ a measure of statehood” — i.e., of international

legal personality. Not only is there a necessary implication of the juridical

authority within its own territory, obeyed by the people over whom it rules, capable of

performing the duties and fulfilling the obligations of an independent power, able to

enforce its claims by military force, is a fact, not a theory. For it recognition does

not create the state, although it may be desirable.”

12 Op. cit., pp. 24, 45 ff.

is Louis L. Jaffe, Judicial Aspects of Foreign Relations, In Particular of the Recog

nition of Foreign Powers (Harvard University, 1933), pp. 96, 121.

1 * See illustrative materials, sometimes under the rubric “ Acts Falling Short of

Recognition,” in Moore, Digest o f International Law, Vol. I, p. 206 fit.; Hackworth,

Digest of International Law, Vol. I, p. 327 ff.; H. A. Smith, Great Britain and the Law

of Nations, Vol. I (1932), pp. 115 ff., 190; Lauterpacht, op. cit., p. 369 ff.

is Op. cit., p. 54.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2193138 Published online by Cambridge University Press

118 THE A MERICAN JOURNAL OP INTERNATIONAL LAW

capacity of the unrecognized state through its agents to conclude agree

ments which are legally binding under international law,18 but the unrecog

nized state is regarded as obligated not to commit acts in violation of a law

by which, according to the constitutive theory, it is not bound. An un

recognized state, writes Lauterpacht17 with careful dialectic,

cannot, in reliance on the formal logic of its non-recognition, claim the

right to commit acts which if done by a recognized authority would

constitute a violation of international law. . . . There can be no ob

jection to treating the unrecognized state as if it were bound by obliga

tions of international law if these obligations are so compelling as to

be universally admitted and if the non-recognizing state acknowledges

itself to be bound by them.

Thus, on May 9,1922, the American Commissioner in Albania was instructed

to protest to the governmental authorities of the unrecognized Albanian

state against their action in depriving American citizens of Albanian origin

of their American passports and forcing them to take Albanian passports.

Although the printed correspondence describing the American protest and

the Albanian engagement to recognize all United States passports contains

no reference to international law, the evidence suggests that, despite non

recognition of Albania by the United States, international law was re

garded by both states as regulating their relations and as establishing both

the delictual responsibility and the contractual capacity of the unrecog

nized state.18

Since “ unofficial relations” are a convenient, although juridically am

biguous, device for dealing with communities from which, because of their

indeterminate status or for political reasons, it is considered desirable to

withhold recognition, foreign offices have been reluctant to admit a legal

duty to recognize. “ We are not in a position,” admits Lauterpacht19

after a barren search for convincing evidence to the contrary, “ to say

either that there is a clear and uniform practice of states in support of the

legal view of recognition, or that the process of recognition has invariably

taken place, in all its aspects, under the aegis of international law. ’ ’

A study of the practice of states 20 reveals that considerations which have

i« See, for example, the agreement relating to most-favored-nation treatment and other

matters concluded by the United States and Albania by exchange o f notes at Tirana,

June 23 and 25, 1922, prior to, and as a condition of, United States recognition of

Albania as a state on July 28, 1922. U. S. Foreign Relations, 1922, Vol. I, pp. 603-604;

ibid., 1925, Vol. I, pp. 511-512.

if Op. oit., pp. 53-54.

is U. S. Foreign Eelations, 1922, Vol. I, p. 599; ibid., 1925, Vol. I, pp. 511-514.

19 Op. cit., p. 78.

20 As set forth particularly in Moore, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 77 ff.; Hackworth, op. cit.,

Vol. I, p. 195 ff.; H. A. Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 77 S. ; M. W. Graham, The Diplomatic

Recognition of the Border States: I, Finland; II, Estonia; III, Latvia; Lauterpacht,

op. cit., pp. 12 ff., 26-37; Fontes Juris Oentivm, Ser. B, Ser. 1, Tom. 1, Digest of the

Diplomatic Correspondence of the European States, 1856-1871, p. 130 ff., and ibid.,

Tom. 2, 1871-1878, p. 78 ff.; U. S. Foreign Relations, passim.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2193138 Published online by Cambridge University Press

EDITORIAL COMMENT 119

been weighed by foreign offices in determining whether to recognize a new

state or to defer or withhold recognition include: the freedom of the new

state from external control; the stability and effectiveness of its govern

ment, and perhaps an estimate of its permanence as indicated by popular

support; the ability, and perhaps the willingness, of the new state to ful

fill its obligations under international law; whether “ its existence responds

to political exigencies” in a region such as Europe or the Adriatic or in

the world community; the extent to which it “ commands international sup

port,” i.e., has been recognized by other states; the extent to which its es

tablishment affronts principles of dynastic or constitutional legitimacy;

whether its recognition would offend an ally or be otherwise premature;

whether its recognition would not go far “ to support legitimate enter

prise” of the recognizing state or be politically advantageous; the use of

non-recognition as a sanction of national policy or of international law.

Particular considerations adverted to in state papers may be deemed by

an observer to be politically noxious or juridically ambiguous but, despite

occasional references to a natural right to recognition or a moral obligation

to recognize, the evidence fails to support the thesis that, in granting recog

nition, foreign offices regard themselves as fulfilling a legal duty or per

forming a function as an “ organ” of international law. Was it really

the failure of Israel to fulfill the “ basic criteria” of statehood or considera

tions of British foreign policy and international politics which caused the

British Foreign Office to decline recognition to Israel in May 1948 ? 21

When the United States hastily granted de facto recognition to Israel and

the Soviet Union countered by granting de jure recognition, and the Arab

states granted no recognition, does the available evidence suggest that con

siderations of national or international politics were subordinated to legal

criteria or that any one of these states was fulfilling a legal obligation or

violating international law? “ The main difficulty with the constitutive

theory,” writes Philip Marshall Brown, “ is that it is mere theory.” 22

What, then, is the juridical function of recognition as determined by state

pronouncements and conduct? The establishment of diplomatic relations,

although a normal consequence of recognition, is not a consequence re

quired by international law, since states are legally entitled to establish

“ unofficial relations” prior to recognition and to delay, establish or sever

official diplomatic relations even after recognition. The principal juridical

function of recognition is that, by acknowledging the full status of a

hitherto indeterminate community, the recognizing state makes possible the

regularizing of relations between them on the basis of international law.

The acknowledgment that the recognized political community possesses the

attributes of statehood and full capacity in international law at the time

of recognition does not pretend to answer the question as to how long prior

See Philip Marshall Brown, “ The Recognition of Israel,” this J o u r n a l , Vol. 42

(1948), pp. 620-627.

2 2 “ The Effects of Recognition,” this J o u r n a l , Vol. 36 (1942), p. 106.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2193138 Published online by Cambridge University Press

120 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OP INTERNATIONAL LAW

to recognition the community may or may not have been in possession of

the attributes of statehood and legal capacity. The act of recognition is

thus not constitutive in the sense that it confers international juridical

personality upon an entity which did not possess it prior to recognition.

Nor is recognition merely cognition. The cognitive element of acknowledg

ing that the recognized community possesses the attributes of statehood

and capacity under international law is formally embodied in an official

assurance that the legal consequences of statehood and capacity will be ac

cepted by the recognizing state.23

There is no necessary implication that the probably limited relations be

tween them prior to recognition were not governed by international law.

The theoretical objection that, if the unrecognized state possesses rights

under international law prior to recognition, it is a violation of inter

national law for a non-recognizing state to deny the exercise of these rights,

assumes too much and proves too little. Even between recognized states

the exercise of certain rights is suspended when diplomatic relations are

severed. Moreover, except perhaps in such fields as the extraterritorial

effect to be given to certain state acts, practice with regard to unrecognized

states reveals no wholesale disregard of the rights and obligations stipu

lated by international law for the governance of international relations.

The significant fact is that, prior to recognition, relations with an un

recognized state are likely to be limited in scope.

Foreign offices have not been concerned with pushing juridical concep

tions to the limit of their logic and have regarded recognition as extending

the scope of rights and obligations between recognizing and recognized

states, without indulging in sterile debate as to whether the act of recog

nition “ confirmed” previously existing rights or “ created” new rights.

The practical effect has been an increased sense of obligation on the part

of the recognizing state and an increasing ability on the part of the recog

nized state to secure the enjoyment of its rights abroad. The belief that

“ the unrecognized state and its acts do not legally exist prior to recog

nition” 24—a confusion exhibited by English and American courts in the

early 19th century—has influenced national jurisprudence, but appears to

be based upon a misconstrued judicial deference for the acts of another

branch of the same government in granting or withholding recognition, or

upon conceptualist logic, rather than upon the requirements of international

law.25

28 Compare J. L. Brierly, The Law of Nations (3rd ed., 1942), p. 100: “ The primary

function of recognition is formally to acknowledge -as a fact something which has

hitherto been uncertain, namely, the independence of the state recognized, and to de

clare the recognizing state’s readiness to accept the normal consequences of that

fact. . .

2 4 Lauterpacht, op. cit., p. 44. Compare Kelsen, loc. cit., p. 608: “ Before recognition,

the unrecognized community does not legally exist vis-d-vis the recognizing state.”

25 See P. L. Bushe-Fox, ‘ ‘ The Court of Chancery and Recognition, 1804-31, ’ ’ British

Year Book of International Law, 1931, p. 63; Bushe-Fox, “ Unrecognized States: Cases

https://doi.org/10.2307/2193138 Published online by Cambridge University Press

EDITORIAL COMMENT 121

Juridical theories of recognition logically deduced from jurisprudential

concepts fail to explain the facts of state conduct, and inductions from the

conduct of states have failed to provide a juridically unambiguous theory

of recognition. The path to the future is clearly indicated by two considera

tions: the decentralized nature of the practice of recognition and the de

veloping community interest in the emergence of new states. Collective

recognition by the Great Powers has been sparingly employed in the past

and has sometimes savored of collective intervention.28 Whether admission

to membership in the League of Nations constituted automatic recognition

was always controversial.27 Nor has the United Nations clearly settled the

question of the relation of membership to recognition.28 In his A Modern

Law of Nations, Philip Jessup has proposed that the United Nations Gen

eral Assembly might by general convention or declaration establish the

essential criteria of statehood, provide for a finding that a particular entity

possesses the required attributes and pledge members not to accord recog

nition to new states except in accordance with a standard procedure.29

With the centralization of the recognition of states in an international

organization, the granting of recognition might well acquire the role of a

legal function performed on behalf of the organized community of states,

a role which today appears to exist more in theory than in fact.

H erbert W. B riggs

in the Admiralty and Common Law Courts, 1805-26,” ibid., 1932, p. 39; A. B. Lyons,

“ The Conelusiveness of the Foreign Office Certificate,” ibid., 1946, pp. 240, 245 ff.;

Jaffe, op. cit., passim; E. D. Dickinson, “ The Unrecognized Government or State in

English and American Law,” 22 Michigan Law Review (1923), pp. 29, 118. For the

decision of an international tribunal affirming the declaratory nature of recognition, see

Deutsche Continental Gas-Gesellschaft v. Polish State, decided Aug. 1, 1929, by the

German-Polish Mixed Arbitral Tribunal, Recueil des Decisions des Tribunaux Arbitraux

Mixtes, Vol. IX , pp. 336, 344; see comment thereon by Hans Herz, “ Le Problime de

la Naissance de I’M at et la Decision . . . du J Aout 1929,” Revue de Droit International

et de Legislation Comparee (3rd ser.), Vol. 17 (1936), p. 564.

28 See, for example, collective recognition o f Greece, 1830, British and Foreign State

Papers, Vol. X V II, p. 191; of Belgium, 1831, ibid., Vol. X V III, pp. 645, 723 ff.; of

Montenegro, Serbia and Roumania, 1878, ibid., Vol. L X IX , pp. 758, 761, 763, 862 ff.;

of Albania, 1921, League of Nations Official Journal (2nd Year, 1921), p. 1195, and

G eT h a rd Pink, The Conference of Ambassadors (Paris, 1920-1931), Geneva Studies,

Vol. X II, Nos. 4-5 (1942), pp. 106-116, 203 ff.; of Estonia and Latvia, 1921, British

and Foreign State Papers, Vol. CXIV, p. 558, and M. W. Graham, op. cit., p. 290 ff.

See also British and Foreign State Papers, Vol. CXII, p. 225 ff., Clemenceau to Pader

ewski, June 24, 1919.

27 Graham, op. cit., pp. 295 ff., 300-301, 372, 375-6; Graham, The League o f Nations

and the Recognition of States (1933), and the works there cited.

28 The Advisory Opinion of May 28, 1948, of the International Court of Justice on

Conditions of Admission o f a State to Membership in the United Nations (Charter,

Art. 4) (I. C. J . Reports, 1947-1948, p. 57 ff.; this J o u r n a l , Vol. 42 (1948), p. 927),

while dealing with the criteria of membership in the United Nations, discusses neither

the criteria of statehood nor recognition.

2» Op. cit. (1948), pp. 44-51.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2193138 Published online by Cambridge University Press

You might also like

- Constitutions of Pakistan 1956 1962 1973Document2 pagesConstitutions of Pakistan 1956 1962 1973Farhan Farzand87% (78)

- Kinds of GovernmentsDocument9 pagesKinds of GovernmentsNoel IV T. Borromeo100% (2)

- American RealismDocument32 pagesAmerican RealismGauravKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Individuals As Subjects of International Law PDFDocument19 pagesIndividuals As Subjects of International Law PDFDank ShankNo ratings yet

- Part I The Concept of Statehood in International Law, Ch.1 Statehood and RecognitionDocument31 pagesPart I The Concept of Statehood in International Law, Ch.1 Statehood and RecognitionAnirudh Patwary100% (1)

- Defining Statehood, The Montevideo Convention and Its DiscontentsDocument57 pagesDefining Statehood, The Montevideo Convention and Its DiscontentsJeffrey L. OntangcoNo ratings yet

- Benton and Clulow - Legal EncountersDocument21 pagesBenton and Clulow - Legal EncountersMatthew KimaniNo ratings yet

- The Development of Conflicts LawDocument33 pagesThe Development of Conflicts LawAngela Louise SabaoanNo ratings yet

- Responsibility of States For Injuries To ForeignersDocument51 pagesResponsibility of States For Injuries To ForeignersADHEERA BINTI MOHD SALMI (MOE)No ratings yet

- 10 - Territory-In-International-LawDocument31 pages10 - Territory-In-International-LawecalotaNo ratings yet

- Universal International Law Nineteenth Century Histories of Imposition and AppropriationDocument78 pagesUniversal International Law Nineteenth Century Histories of Imposition and AppropriationAntonio UrrutiaNo ratings yet

- Difference and Deference in Treaty InterpetationDocument63 pagesDifference and Deference in Treaty InterpetationEdgar OdongoNo ratings yet

- Statehood 2Document31 pagesStatehood 2Willard Enrique MacaraanNo ratings yet

- Inter Unit I PDFDocument7 pagesInter Unit I PDFFaizan BhatNo ratings yet

- Public International Law Study MaterialDocument37 pagesPublic International Law Study Materialimro leathersNo ratings yet

- Nature and Origin of Int LawDocument22 pagesNature and Origin of Int Lawchirag agrawalNo ratings yet

- Colonialism and Its Impact On International Law, ID 216124 TWAILDocument10 pagesColonialism and Its Impact On International Law, ID 216124 TWAILMusharaf NazirNo ratings yet

- General Principles of International LawDocument29 pagesGeneral Principles of International LawDharu LilawatNo ratings yet

- British Yearbook of International Law-1977-Crawford-93-182 PDFDocument90 pagesBritish Yearbook of International Law-1977-Crawford-93-182 PDFzepedrobrNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of International Law: Colonial and Postcolonial RealitiesDocument6 pagesThe Evolution of International Law: Colonial and Postcolonial RealitiesAnanya100% (2)

- Private International Law or International Private LawDocument19 pagesPrivate International Law or International Private LawSAMIKSHA SHRIVASTAVANo ratings yet

- KOSKENNIEMI - What Use For SovereigntyDocument10 pagesKOSKENNIEMI - What Use For SovereigntyStefanoChiariniNo ratings yet

- The Elements of International LawDocument6 pagesThe Elements of International LawhidhaabdurazackNo ratings yet

- The Proper Law of The ContractDocument24 pagesThe Proper Law of The ContractrajNo ratings yet

- UWU Compiled 2Document75 pagesUWU Compiled 2Luzenne JonesNo ratings yet

- The Role of Positivism in The Development of International Law PDFDocument21 pagesThe Role of Positivism in The Development of International Law PDFShubhankar ThakurNo ratings yet

- A Phenomenological Theory of The Human Rights of The Alien: William E. Conklin University of Windsor (Ontario, Canada)Document57 pagesA Phenomenological Theory of The Human Rights of The Alien: William E. Conklin University of Windsor (Ontario, Canada)Mamatha RangaswamyNo ratings yet

- The Nature Origin and Development of IntDocument21 pagesThe Nature Origin and Development of IntShrinivas DesaiNo ratings yet

- Definition of Modern International LawDocument9 pagesDefinition of Modern International LawRohit YadavNo ratings yet

- International Law Notes - Dr. KabumbaDocument23 pagesInternational Law Notes - Dr. KabumbaNathan NakibingeNo ratings yet

- A Basic Introduction To The Sources of International Law: Ori PomsonDocument12 pagesA Basic Introduction To The Sources of International Law: Ori PomsonnheneNo ratings yet

- Alain Pellet - Badinter Comission ReviewDocument9 pagesAlain Pellet - Badinter Comission ReviewDumitru CazacNo ratings yet

- Jus Cogens PDFDocument27 pagesJus Cogens PDFshellahmayeNo ratings yet

- Genuine LinkDocument61 pagesGenuine Linksalehmagdy1999No ratings yet

- SSRN Id1877123Document15 pagesSSRN Id1877123Rishi Shrivastava100% (1)

- The Opinions of The Badinter Arbitration Committee 1-3Document8 pagesThe Opinions of The Badinter Arbitration Committee 1-3lonefrancNo ratings yet

- Atty Bagares PDFDocument188 pagesAtty Bagares PDFCarla VirtucioNo ratings yet

- Gordon A. Christenson, Jus Cogens: Guarding Interests Fundamental To International Society, 28 VA. J. INT'l L. 585 (1988) .Document65 pagesGordon A. Christenson, Jus Cogens: Guarding Interests Fundamental To International Society, 28 VA. J. INT'l L. 585 (1988) .Agent BlueNo ratings yet

- recognition-of-states-international-law-or-realpolitik-the-practice-of-recognition-in-the-wake-of-kosovo-south-ossetia-and-abkhaziaDocument24 pagesrecognition-of-states-international-law-or-realpolitik-the-practice-of-recognition-in-the-wake-of-kosovo-south-ossetia-and-abkhaziaAnton BilokonNo ratings yet

- Historical OverviewDocument8 pagesHistorical OverviewVishal kumarNo ratings yet

- The Sources of International LawDocument6 pagesThe Sources of International Lawshahzadjaved640No ratings yet

- Oundo Cj.Document21 pagesOundo Cj.Prince AgeNo ratings yet

- Nature - Development of 382 NotesDocument4 pagesNature - Development of 382 NoteslehlohonolomositijnrNo ratings yet

- International Legal PluralismDocument17 pagesInternational Legal PluralismIgnacio TorresNo ratings yet

- International Law and World War IDocument15 pagesInternational Law and World War IOzgur KorpeNo ratings yet

- Pil ReviewerDocument25 pagesPil ReviewerSamuel Johnson100% (1)

- Public International Law ReviewerDocument25 pagesPublic International Law Reviewermamp05100% (5)

- 17 Brit YBIntl L66Document17 pages17 Brit YBIntl L66Aishwarya BuddharajuNo ratings yet

- 13 - The Islamic Law of Nations and Its Place in TDocument19 pages13 - The Islamic Law of Nations and Its Place in TDupla PaltaNo ratings yet

- Injury To AliensDocument30 pagesInjury To AliensMamatha RangaswamyNo ratings yet

- 2006006060Document12 pages2006006060saad aliNo ratings yet

- Readings On Nationality and DomicileDocument16 pagesReadings On Nationality and DomicileSalex E. AliboghaNo ratings yet

- Transcivilizational v6-1 PDFDocument8 pagesTranscivilizational v6-1 PDFJuan Andrés TrianaNo ratings yet

- The Legal Significance The Declo Rations The General Assembly The United NationsDocument287 pagesThe Legal Significance The Declo Rations The General Assembly The United NationsRiya Shankar SharmaNo ratings yet

- Mediaocean 01Document8 pagesMediaocean 01Limon Md. KaykobadNo ratings yet

- Illegal Occupation Framing The Occupied Palestinian TerritoryDocument65 pagesIllegal Occupation Framing The Occupied Palestinian TerritoryDinaazouni100% (2)

- International Legal PersonalityDocument13 pagesInternational Legal PersonalityKajal RaiNo ratings yet

- 114 Penn Statim 34 PDFDocument7 pages114 Penn Statim 34 PDFabdul raufNo ratings yet

- Pax mundi: A concise account of the progress of the movement for peace by means of arbitration, neutralization, international law and disarmamentFrom EverandPax mundi: A concise account of the progress of the movement for peace by means of arbitration, neutralization, international law and disarmamentNo ratings yet

- The Law of the United Nations as Applied to Intervention Within the Frame Work of Article 2, Paragraph 7 of the Un Charter: A Comparative Analysis of Selected Cases to Establish the Underpinning Reality of the Danger of the Principles of Sovereign Equality and Domestic Jurisdiction Against Un Mandate for Total Humanity's Peaceful Co - Existence and Prosperity.From EverandThe Law of the United Nations as Applied to Intervention Within the Frame Work of Article 2, Paragraph 7 of the Un Charter: A Comparative Analysis of Selected Cases to Establish the Underpinning Reality of the Danger of the Principles of Sovereign Equality and Domestic Jurisdiction Against Un Mandate for Total Humanity's Peaceful Co - Existence and Prosperity.No ratings yet

- IPS Force CalibrationDocument4 pagesIPS Force CalibrationPatrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Guideline DKD-R 9-2Document9 pagesGuideline DKD-R 9-2Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Ds Force and Weight Measuring InstrumentsDocument73 pagesDs Force and Weight Measuring InstrumentsPatrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Wagstaff Homeworking Product Guide May 2020Document46 pagesWagstaff Homeworking Product Guide May 2020Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- SADIS User GuideDocument103 pagesSADIS User GuidePatrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Fixed Displacement Vane Pumps DatasheetDocument6 pagesFixed Displacement Vane Pumps DatasheetPatrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- BS en 1926Document20 pagesBS en 1926Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Department of Transportation: California Test 203 February 2008Document5 pagesDepartment of Transportation: California Test 203 February 2008Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Department of Transportation: California Test 202 November 2011Document20 pagesDepartment of Transportation: California Test 202 November 2011Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Fluide Ii D: Fluid For Automatic Transmissions and Hydraulic SystemsDocument1 pageFluide Ii D: Fluid For Automatic Transmissions and Hydraulic SystemsPatrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Department of Transportation: California Test 105 July 2012Document14 pagesDepartment of Transportation: California Test 105 July 2012Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- FSEL Flexural StrengthTesting Rev 00Document9 pagesFSEL Flexural StrengthTesting Rev 00Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Ideapad320-14ikb 320x-14ikb 320-14isk 320x-14isk HMM 201704Document82 pagesIdeapad320-14ikb 320x-14ikb 320-14isk 320x-14isk HMM 201704Patrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- GND PlaneDocument4 pagesGND PlanePatrick Sucre MumoNo ratings yet

- Historiography: How Far Does Alexander II Deserve The Title of Tsar Liberator'?Document2 pagesHistoriography: How Far Does Alexander II Deserve The Title of Tsar Liberator'?sofiaNo ratings yet

- Principality of SealandDocument1 pagePrincipality of SealandJay L Batiancila ContentoNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Paper FormatDocument11 pagesConceptual Paper FormatelijahNo ratings yet

- DYZENHAUS - Hobbes and The Legitimacy of LawDocument39 pagesDYZENHAUS - Hobbes and The Legitimacy of LawmehrbuchNo ratings yet

- The Role of Judiciary in The Constitutional Development of Pakistan (1947-1971)Document24 pagesThe Role of Judiciary in The Constitutional Development of Pakistan (1947-1971)FahadNo ratings yet

- Rights of A CitizenDocument45 pagesRights of A CitizenApoorvNo ratings yet

- Media LawDocument15 pagesMedia LawAditi IndraniNo ratings yet

- Ethiopia's Developmental State Model: A Reflection On Francis Fukuyama's ArticleDocument13 pagesEthiopia's Developmental State Model: A Reflection On Francis Fukuyama's ArticleAnonymous OdgFZrywoNo ratings yet

- Public AdministrationDocument14 pagesPublic AdministrationEjaz KazmiNo ratings yet

- Friedman Capitalism and FreedomDocument6 pagesFriedman Capitalism and FreedomYessica leyvaNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law Administrative LawDocument3 pagesConstitutional Law Administrative LawUtkarsh KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Ideology Security As National SecurityDocument14 pagesIdeology Security As National SecurityM Abdillah JundiNo ratings yet

- Parliamentary & Presidential Govt.Document14 pagesParliamentary & Presidential Govt.Royal Raj Alig100% (1)

- Ora John Reuter - Political Participation and The Survival of Electoral Authoritarian RegimesDocument37 pagesOra John Reuter - Political Participation and The Survival of Electoral Authoritarian RegimesMilos JankovicNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Democracy and RepublicDocument5 pagesDifference Between Democracy and RepublicAlvin Corpuz JrNo ratings yet

- Pengembangan KapasitasDocument7 pagesPengembangan KapasitasKhoirul RizalNo ratings yet

- Current Issues in The International Relations - 4th Week Analysis - Süha Mete KalenderDocument2 pagesCurrent Issues in The International Relations - 4th Week Analysis - Süha Mete KalenderSüha Mete KalenderNo ratings yet

- Aristotle's Politics - SummaryDocument2 pagesAristotle's Politics - SummaryIzabelaKaxniashviliNo ratings yet

- Hart - Rawls On Liberty and Its PriorityDocument23 pagesHart - Rawls On Liberty and Its Priorityגל דבשNo ratings yet

- State JurisdictionDocument2 pagesState JurisdictionNaeem ul mustafaNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes On DemocracyDocument7 pagesLecture Notes On DemocracygutterbcNo ratings yet

- Heldira Larashati - EAC Kyoto University (Geopolitical Economy of Development Term Assignment)Document3 pagesHeldira Larashati - EAC Kyoto University (Geopolitical Economy of Development Term Assignment)Heldira Larashati HaroenNo ratings yet

- Rousseau Spring 2021Document22 pagesRousseau Spring 2021Johnny KahaléNo ratings yet

- Networked Politics - A ReaderDocument238 pagesNetworked Politics - A ReaderÖrsan ŞenalpNo ratings yet

- Electoral System NotesDocument9 pagesElectoral System NotesAdei ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- 64 LawDocument2 pages64 LawJay TiwariNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Philippine Politics and Government PDFDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Philippine Politics and Government PDFAnonymous 1Pjqb2No ratings yet

- 1962 ConstitutionDocument22 pages1962 ConstitutionAbdul LatifNo ratings yet