Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jay Davidson - The Essential Guide To Calming Lyme Induced Inflamation

Jay Davidson - The Essential Guide To Calming Lyme Induced Inflamation

Uploaded by

nUno MichaelsCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Understanding Immune Health Mayo ClinicDocument8 pagesUnderstanding Immune Health Mayo ClinicCarmel HarelNo ratings yet

- Jay Davidson Symptoms of A Parasitic InfectionDocument4 pagesJay Davidson Symptoms of A Parasitic InfectionNaga BalaNo ratings yet

- Biodiversity of Micro-OrganismsDocument32 pagesBiodiversity of Micro-Organismsapi-20234922250% (2)

- The Essential Guide To Calming Lyme-Induced InflammationDocument7 pagesThe Essential Guide To Calming Lyme-Induced InflammationDorian GrayNo ratings yet

- Trovanje HranomDocument14 pagesTrovanje HranomLamija EmricNo ratings yet

- Autoimmune Diseases: Immune SystemDocument11 pagesAutoimmune Diseases: Immune Systemmaria nataliaNo ratings yet

- HKDSE Biology Part 3 Health & DiseasesDocument17 pagesHKDSE Biology Part 3 Health & DiseasesTSZ YAN CHEUNGNo ratings yet

- Reporting ScienceDocument20 pagesReporting ScienceYasuhiro Hinggo EscobilloNo ratings yet

- Ebook Top 26 Shopping List Supermarket Foods 1Document19 pagesEbook Top 26 Shopping List Supermarket Foods 1Dragica BernotNo ratings yet

- Arthritis RheumatoidDocument15 pagesArthritis Rheumatoidputri rahmadaniNo ratings yet

- Lyme Disease: Submitted byDocument6 pagesLyme Disease: Submitted byhsmolenggeNo ratings yet

- Leaky Gut: The Guide To Treating The Source of Allergies, Joint Pain, Digestive Diseases and MoreDocument15 pagesLeaky Gut: The Guide To Treating The Source of Allergies, Joint Pain, Digestive Diseases and Moresurveytryer2No ratings yet

- Toxic Mold It May Be Harming Your Health More Than You Know Eguide 2555Document17 pagesToxic Mold It May Be Harming Your Health More Than You Know Eguide 2555Petite PoubelleNo ratings yet

- Diseases and VaccinesDocument37 pagesDiseases and Vaccinesraghu ramNo ratings yet

- What Makes You Ill: Made By: Amna AmeenDocument7 pagesWhat Makes You Ill: Made By: Amna Ameenamna ameen StudentNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Disease and Vaccines What Is A Disease?Document2 pagesIntroduction To Disease and Vaccines What Is A Disease?Sue Adames de VelascoNo ratings yet

- Disorders of NSDocument4 pagesDisorders of NSThe KhanNo ratings yet

- Fibromyalgia: The complete guide to fibromyalgia, understanding fibromyalgia, and reducing pain and symptoms of fibromyalgia with simple treatment methods!From EverandFibromyalgia: The complete guide to fibromyalgia, understanding fibromyalgia, and reducing pain and symptoms of fibromyalgia with simple treatment methods!Rating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (2)

- Final Product 2024-05-01 16 06 36Document12 pagesFinal Product 2024-05-01 16 06 36api-711508569No ratings yet

- Diseases and VaccinesDocument22 pagesDiseases and VaccineslakshNo ratings yet

- 6246bb700cf2ee69840e3596 OriginalDocument24 pages6246bb700cf2ee69840e3596 Originalsoma5koshasNo ratings yet

- Margaret Christensen Got Mold Now What Final EditDocument5 pagesMargaret Christensen Got Mold Now What Final EditMarcelo FernandezNo ratings yet

- Guillain Barré SyndromeDocument20 pagesGuillain Barré Syndromelourdes kusumadiNo ratings yet

- CandidaguideDocument12 pagesCandidaguideNica norNo ratings yet

- Lyme Disease 1Document1 pageLyme Disease 1api-547400638No ratings yet

- Autoimmune Disorders: Description of The DisabilityDocument6 pagesAutoimmune Disorders: Description of The DisabilityCemara Boro SaestiNo ratings yet

- Autoimmune GuidebookDocument20 pagesAutoimmune Guidebookedurodica7No ratings yet

- Nerve Pain and Nerve Damage 2Document17 pagesNerve Pain and Nerve Damage 2Ryan BediNo ratings yet

- Lyme Disease 1Document14 pagesLyme Disease 1api-677928137No ratings yet

- Margaret-Christensen Got Mold Now What UpdatedDocument5 pagesMargaret-Christensen Got Mold Now What UpdatedMirela Olarescu100% (1)

- The Effects of Chronic Stress: Stress Is Your Body's Way of Responding To Any KindDocument3 pagesThe Effects of Chronic Stress: Stress Is Your Body's Way of Responding To Any KindXanthophile ShopeeNo ratings yet

- CB5 - Revision - Summary Filled inDocument3 pagesCB5 - Revision - Summary Filled inSiaNo ratings yet

- Got Mold? Now What?: Hope For Health and HomeDocument5 pagesGot Mold? Now What?: Hope For Health and HomeFlo BorsNo ratings yet

- ACUTE INFLAMMATION VS CHRONIC INFLAMMATION Assignment #2 (CU-1774-2020)Document17 pagesACUTE INFLAMMATION VS CHRONIC INFLAMMATION Assignment #2 (CU-1774-2020)Ali Aasam KhanNo ratings yet

- Black Neon Green Neon Pink Trendy Illustrative Creative Presentation 2Document21 pagesBlack Neon Green Neon Pink Trendy Illustrative Creative Presentation 2Sherry-Ann TulauanNo ratings yet

- Multiple Sclerosis 1.1. Definition: Immunologic DisorderDocument21 pagesMultiple Sclerosis 1.1. Definition: Immunologic Disordergrazelantonette.calubNo ratings yet

- Guillain-Barré Syndrome Fact Sheet - National Institute of Neurological Disorders and StrokeDocument9 pagesGuillain-Barré Syndrome Fact Sheet - National Institute of Neurological Disorders and StrokeCarl MacCordNo ratings yet

- Iitei: NieieiircDocument1 pageIitei: Nieieiircapi-21190143No ratings yet

- PBL 1 ResultDocument11 pagesPBL 1 ResultNabilla MahdiNo ratings yet

- Parasites and SusceptibilityDocument13 pagesParasites and SusceptibilityCaroline D.No ratings yet

- Chapter 1 DiseasesDocument10 pagesChapter 1 DiseasesQaran PrintingNo ratings yet

- DISEASES FINALDocument29 pagesDISEASES FINALnitishkumarswain2No ratings yet

- RA and FMDocument3 pagesRA and FMSNo ratings yet

- PainDocument5 pagesPainSyamsulAriefNo ratings yet

- Causes and Prevention of DiseasesDocument4 pagesCauses and Prevention of DiseasesSusan Hepzi100% (1)

- 6B-Biology Notes - Diseases and HygieneDocument13 pages6B-Biology Notes - Diseases and HygieneJagrity SinghNo ratings yet

- Depression and CopingDocument18 pagesDepression and CopingAlcesua EalmyelaNo ratings yet

- Tle Lead PoisoningDocument2 pagesTle Lead PoisoningXhaNo ratings yet

- HEALTH 9 QUARTER2 MODULE3 WeeK5-6Document9 pagesHEALTH 9 QUARTER2 MODULE3 WeeK5-6Heidee Basas100% (3)

- University of Northern PhilippinesDocument4 pagesUniversity of Northern PhilippinesCatherine PradoNo ratings yet

- English Final ProjectDocument16 pagesEnglish Final ProjectAry SanucasNo ratings yet

- Yoga 4 Immune SystemDocument33 pagesYoga 4 Immune Systemsukunath100% (1)

- Psy 325 LecturesDocument14 pagesPsy 325 LecturesErika BalaniNo ratings yet

- Virus, Viroids and PrionsDocument29 pagesVirus, Viroids and PrionscatherinejoaquinNo ratings yet

- HEALTH 4TH Q NCD - For Blended LearnersDocument35 pagesHEALTH 4TH Q NCD - For Blended LearnersAlmighty OperyNo ratings yet

- Health Problems Most Common in School Aged ChildrenDocument15 pagesHealth Problems Most Common in School Aged ChildrenAsterlyn ConiendoNo ratings yet

- GR - 9 - Revision Notes - Why We Do Fall IllDocument9 pagesGR - 9 - Revision Notes - Why We Do Fall IllAditi KumariNo ratings yet

- Examples of DrugsDocument29 pagesExamples of DrugsEdwins MaranduNo ratings yet

- Symptoms: What Are The Complications of Insomnia?Document4 pagesSymptoms: What Are The Complications of Insomnia?Mohamad nazrinNo ratings yet

- F&E ExamDocument3 pagesF&E ExamDino PringNo ratings yet

- (Burnett James C.) Tumours of The Breast and TheirDocument78 pages(Burnett James C.) Tumours of The Breast and TheirRajendraNo ratings yet

- Benefit Packages (Private)Document103 pagesBenefit Packages (Private)You Are Not Wasting TIME HereNo ratings yet

- ALU 101 Sample QuestionsDocument4 pagesALU 101 Sample Questionsartlover30No ratings yet

- Case 013: Fever in A Cirrhotic PatientDocument5 pagesCase 013: Fever in A Cirrhotic PatientFitri 1997No ratings yet

- Chaves 2020Document10 pagesChaves 2020Matheus CastroNo ratings yet

- 08-Hand-Arm VibrationDocument35 pages08-Hand-Arm Vibrationjimmy tiarlinaNo ratings yet

- Read Online Textbook Second A Gay Hockey Romance La Storm Book 2 RJ Scott Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument22 pagesRead Online Textbook Second A Gay Hockey Romance La Storm Book 2 RJ Scott Ebook All Chapter PDFrodney.ellison150100% (3)

- MILLETSDocument11 pagesMILLETSVeer VijayNo ratings yet

- ACOG Combined List of TitlesDocument13 pagesACOG Combined List of TitlesLaura RojasNo ratings yet

- Reflection AssignmentDocument5 pagesReflection Assignmentapi-659065431No ratings yet

- Transmission Sars Cov-2Document7 pagesTransmission Sars Cov-2Ikmah FauzanNo ratings yet

- Endomaterial Cancer-1Document28 pagesEndomaterial Cancer-1A.H.ANo ratings yet

- Fat-And Water-Soluble VitaminsDocument9 pagesFat-And Water-Soluble VitaminsJessa Mae OhaoNo ratings yet

- Water and ElectrolytesDocument39 pagesWater and ElectrolytesevbptrprnrmNo ratings yet

- Communicable Diseases HandoutDocument7 pagesCommunicable Diseases Handoutariane100% (1)

- Cefuroxime Drug StudyDocument1 pageCefuroxime Drug StudyACOB, Jamil C.No ratings yet

- Lippincotts Antiarrhythmics 5Document1 pageLippincotts Antiarrhythmics 5Wijdan HatemNo ratings yet

- Week 14 - Leukocyte Abnormalities and Non-Malignant Leukocyte DisordersDocument83 pagesWeek 14 - Leukocyte Abnormalities and Non-Malignant Leukocyte DisordersSheine EspinoNo ratings yet

- Nursing Responsibilities Adverse Effect Indication / Contraindication Mechanism of Action Drug Name IndicationDocument2 pagesNursing Responsibilities Adverse Effect Indication / Contraindication Mechanism of Action Drug Name IndicationOmar IzzoNo ratings yet

- Basic Encoding ActivityDocument3 pagesBasic Encoding ActivityJHOMER CABANTOGNo ratings yet

- Polycythemia: (Primary & Secondary)Document16 pagesPolycythemia: (Primary & Secondary)Vanessa Camille DomingoNo ratings yet

- PA1 HandoutDocument22 pagesPA1 HandoutIligan, JamaicahNo ratings yet

- 7.2 FTAT Coding Registers Case ScenariosDocument25 pages7.2 FTAT Coding Registers Case ScenariosGosa MohammedNo ratings yet

- 47-Article Text-305-1-10-20220731Document10 pages47-Article Text-305-1-10-20220731alyn30274No ratings yet

- ANT Handbook 2023Document84 pagesANT Handbook 2023latibaleni02No ratings yet

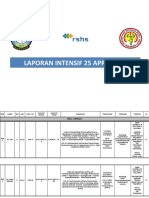

- Laporan Intensif 25 April 2021Document21 pagesLaporan Intensif 25 April 2021bosnia agusNo ratings yet

- Avian Influenza H5N1 VirusDocument27 pagesAvian Influenza H5N1 VirusHarsh Purwar100% (3)

- DGHS IPHS Sub-Dist Hosps 31 To 50Document113 pagesDGHS IPHS Sub-Dist Hosps 31 To 50shanmugapriyasankarNo ratings yet

- WEEK 2 Management of Patients With Chest and Lower Respiratory Tract DisordersDocument9 pagesWEEK 2 Management of Patients With Chest and Lower Respiratory Tract DisordersTin tinNo ratings yet

Jay Davidson - The Essential Guide To Calming Lyme Induced Inflamation

Jay Davidson - The Essential Guide To Calming Lyme Induced Inflamation

Uploaded by

nUno MichaelsOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jay Davidson - The Essential Guide To Calming Lyme Induced Inflamation

Jay Davidson - The Essential Guide To Calming Lyme Induced Inflamation

Uploaded by

nUno MichaelsCopyright:

Available Formats

The Essential

Guide to Calming

Lyme-Induced

Inflammation

People with chronic illnesses, like Lyme disease, usually have a long

list of health problems that have them digging through various

internet sources (hopefully, reputable ones) for answers. Those

seemingly separate issues could boil down to one central source —

chronic Lyme disease.

Indeed, chronic Lyme disease has many vague, erratic, and

concealed symptoms. What’s more, chronic illnesses have so many

symptoms in common and can look a lot like one another. Mapping

out your personal scenario can be challenging, since testing for

Lyme disease may be unreliable.

Chronic Lyme Disease

During the early stages of Lyme disease, it may seem like you have a flu bug. You could

have aches, pains, stiffness, and swollen glands. These symptoms may last a few weeks. If

caught in the early stages, Lyme disease may be easier to diagnose and treat.

Chronic Lyme disease, or “late-stage Lyme,” is much different. Signs of this chronic illness

may arise gradually, over time. Or, they may be ongoing, having never entirely resolved

with earlier treatment. In some cases, physical or emotional stress may have an impact,

and push the disease front and center.

Blood tests often fail to diagnose this type of Lyme disease, as the acute phase is past. The

corkscrew-shaped Lyme bacteria are no longer floating in the bloodstream; they have

drilled down into the tissues where they are harder to see. Plus, the infection can confuse

your immune system. It may not create the antibodies required to get a positive test

result.

Thus, the source of your pain and inflammation can be elusive. Yet, Lyme disease

symptoms may be in plain sight. You may develop long-term issues like joint pain, severe

and debilitating fatigue, headaches, and trouble concentrating. These may become more

crippling and devastating over time.

Lyme Disease Contributes to

Immune System Dysfunction

Chronic Lyme disease can cause a substantial amount of inflammation, due in part to

taxing your immune system. The Lyme bacteria provoke your immune cells to produce

small proteins called cytokines. These substances generate inflammation to fight the

infection.[1]

But, another problem may manifest — your immune system’s activity may not return to

normal — even after the infection is knocked back. It may go into a hyperactive state,

continuing to fight just as hard as if it was battling a new threat.

This is partly the case because the bacteria are masters of disguise. They can mutate and

change form. Over and over, the immune cells see them as new threats. The immune cells

search for many invaders, rather than merely the original one. Then, the immune system is

continually in hyperimmune emergency mode, which continues to cause painful

inflammation.

So, the effect of Lyme disease on the immune system is both suppression

(downregulation) and too much stimulation (upregulation). In this scenario, balancing

immune function (immune modulation) is critical.

Lyme Disease Causes

Joint Inflammation

Chronic Lyme disease doesn’t discriminate. You could be the fittest,

healthiest person before you contract it. It will still try to take you down.

This disease damages the joints and can cause excruciating pain. You

might become unable to enjoy your former quality of life.

Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria that causes Lyme disease, love to

hang out in the joints and connective tissues, including cartilage,

tendons, and ligaments. The bacteria bind to collagen in these

connective tissues. Then, they break it down and destroy it. If your body

tries to regenerate these tissues, the microbes can disrupt its efforts.[2]

The Lyme disease bacteria are dependent on your body for nutrients.

Since they can’t make specific proteins, they’ll steal them from your

joints. They’re especially fond of a gel-like substance called hyaluronic

acid. Without it, connective tissues can be brittle, and joints can be stiff.

These stealthy bacteria also cause inflammation in your joints.

Fragments of borrelia remain in joints, even after the microbes are

killed off. This is triggered by a specific substance in their cell walls

(peptidoglycan) that is dumped into the surrounding environment. The

borrelia litterbugs cause you to appear to have arthritis, but the real

culprit is chronic Lyme disease.[3]

The peptidoglycan stays in the synovial fluid, which is the thick liquid

that lubricates the joint and allows it to move smoothly. It causes

ongoing inflammation as the immune system continues to respond.[4]

Lyme Disease Causes

Brain Inflammation

Lyme is an inflammatory disease that affects the nervous system adversely, as well. This

fact is both accurate and terrifying since damage to the brain is a dreaded consequence of

illness.

Lyme spirochetes cross the blood-brain barrier, causing inflammation in the central

nervous system. The brains of patients with chronic Lyme disease show chemical changes

and widespread inflammation.[5] Some of those infected with Lyme disease will ONLY

show nervous system symptoms and signs — they don’t have the joint and body pains.

Lyme neuroborreliosis is the scientific name for the effects B. burgdorferi may produce in

both the peripheral and central nervous systems.[6] The disease and its associated

symptoms develop as a result of inflammatory changes in the central nervous system

(brain and spinal cord), spinal nerves, and dorsal root ganglia.

Common neurocognitive problems include:[7]

Brain fog Sleep disorders

Poor memory Dyslexic-like errors when writing or

Slower thinking speed speaking

Difficulty retrieving words Spatial disorientation

Attention and focus issues Confusion

Irritability, sometimes extreme Emotional responses that are irregular or

out of proportion to the situation at hand

(mood lability)

Neurological system impairments may include:[8]

Numbness Bell's palsy (paralysis of the facial muscles)

Pain Meningitis symptoms such as severe

Fatigue headache, fever, and stiff neck

Weakness Nerve damage in the arms and legs

Increased sensitivity to specific Visual disturbances

frequencies and volume ranges of sound Impaired fine motor control

(auditory hyperacusis)

Around 40% of individuals with chronic Lyme develop neurological issues. Lyme disease

can also affect the neurotransmitters, manifesting as anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder,

anorexia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or schizophrenia. Major depression develops in

many chronic Lyme patients, which contributes to thoughts of suicide. Panic attacks and

aggression are a sign of the spirochete’s attack on the central nervous system, as well.[9,10]

Address Inflammation

with Dietary Adjustments

It’s plain to see that calming inflammation in the body could provide some much-needed

relief for people with Lyme disease. Eating an anti-inflammatory diet is helpful. Some foods

and beverages are associated with an increased risk of inflammation. Consider reducing or

cutting out:

Sugar and sugary beverages Processed snack foods

Refined carbs Processed seed and vegetable oils (like corn,

Gluten canola, and soybean)

Wheat and corn (due to pesticide residues, Foods with partially hydrogenated (trans-

mold, fungus) fat) ingredients

Pre-packaged and fast foods Genetically modified foods

Processed meats Alcohol

You can also ADD anti-inflammatory foods, including:

Vegetables (particularly cruciferous veggies) Wild-caught fatty fish, including salmon,

Low-sugar fruits sardines, herring, anchovies, and mackerel

High-fat fruits, including avocados and Dark chocolate (in moderation)

olives Spices, including turmeric, ginger, garlic,

Healthy fats, including olive oil, avocado oil, cinnamon, clove, and cayenne

and coconut oil Green tea

Nuts Red wine (in moderation)

Remember to “eat the rainbow” of fruits and vegetables. Also, eat organic, wild-caught,

and pasture-raised produce and meats whenever possible.

Address Inflammation

with Anti-Inflammatory

Herbs and Supplements

Nature offers many plant-based solutions to help calm

inflammation. These may be especially potent when taken as

extracts and used in combination. Collectively, the following

may be more powerful together, rather than individually:

Broccoli sprouts

Mulberry

Artichoke leaf

Blueberry

Wheatgrass

Acai

Pineapple bromelain

Olive leaf

Citrulline (a non-essential amino acid)

Pomegranate

Astaxanthin (a naturally-occurring carotenoid)

General Recommendations for

Lyme-Associated Inflammation

Chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation is a significant contributor to chronic

diseases. Besides the above recommendations, here are a few more to take to

heart:

Get exercise. Physical activity can decrease inflammatory markers, reducing

your risk of Lyme symptoms and chronic disease.[11]

Sleep well.

Both quality and quantity of sleep are extremely critical. Manage

inflammation by focusing on healthy sleep habits.[12]

Obesity

Manage your weight. causes chronic, low-grade inflammation.[13]

Balance

your

blood

sugar

level.

Blood sugar imbalances play a role in

inflammation, increasing the likelihood of insulin resistance, metabolic

syndrome, and diabetes.[14]

Clear environmental toxins.

Daily exposure to toxins, such as chemicals,

pesticides, heavy metals, mycotoxins (from mold), radioactive metals, toxins

released by pathogens, and much more, contribute to inflammation. Reduce

your exposure to these when possible, and detoxify your body to clear them.

As you can see, no matter what you are experiencing health-wise, inflammation

is a likely factor. Since inflammation is involved in so many health conditions, and

the world presents inflammatory environmental challenges daily, keeping

inflammation in check is vital to staying healthy and aging well. Even individuals

who have no health challenges may want to consider keeping tabs on

inflammation.

Lyme disease patients may develop persistent, painful inflammatory issues. If

you’ve been treated for Lyme disease and still feel unwell, your immune system’s

inflammatory response may be out of whack. See your functional medicine

provider or natural health expert to discuss personalized options for managing

your symptoms.

Powered by:

For more information, visit www.MicrobeFormulas.com. At Microbe Formulas, we

live by a simple standard. Creating supplements that work is what we do. Restoring

hope and health is who we are. We’ll help you create Your Roadmap to Health. If

you're chronically ill and looking for solutions, an effective roadmap is critical to your

success. We'd love to help guide you on your path to healing and recovery!

Source:

. Strle, Klemen, et al. “T-Helper 17 Cell Cytokine Responses in Lyme

Disease Correlate With Borrelia burgdorferi Antibodies During Early

Infection and With Autoantibodies Late in the Illness in Patients

With Antibiotic-Refractory Lyme Arthritis.” Clinical Infectious

Diseases, vol. 64, no. 7, 1 April 2017.

. Zambrano, Maria C, et al. “Borrelia Burgdorferi Binds to, Invades, and

Colonizes Native Type I Collagen Lattices.” Infection and Immunity,

American Society for Microbiology, vol. 72, no. 6, June 2004.

. Ross, John. “Chronic Lyme Arthritis: A Mystery Solved?” Harvard

Health Blog, 7 Oct. 2019.

. “Lyme Disease's Arthritis Inflammation Trigger Identified.” GEN, 18

June 2019.

. “New Scan Technique Reveals Brain Inflammation Associated with

Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome.” Johns Hopkins Medicine

Newsroom, 5 Feb 2019.

. Ramesh, Geeta et al. “Inflammation in the pathogenesis of lyme

neuroborreliosis.” The American Journal of Pathology, vol 185, no. 5,

May 2015.

. Westervelt, Holly James and McCaffrey, Robert J.

“Neuropsychological Functioning in Chronic Lyme Disease.”

Neuropsychology Review, U.S. National Library of Medicine, vol. 12,

no. 3, Sept 2002.

. “Neurological Complications of Lyme Disease Information Page.”

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.

. Fallon, B A and Nields, J A. “Lyme Disease: a Neuropsychiatric

Illness.” The American Journal of Psychiatry, U.S. National Library of

Medicine, vol. 151, no. 11, Nov 1994,

. Bransfield, Robert C. “Suicide and Lyme and associated diseases.”

Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, vol. 13, 16 Jun 2017

. Pedersen, Bente Klarlund. “The Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Exercise:

Its Role in Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease Control.” Essays in

Biochemistry, U.S. National Library of Medicine, vol. 42, 2006.

. Mullington, Janet M et al. “Sleep Loss and Inflammation.” Best

Practice & Research. Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, U.S.

National Library of Medicine, vol. 24, no. 5, Oct 2010.

. Vandanmagsar, Bolormaa et al. “The NLRP3 Inflammasome

Instigates Obesity-Induced Inflammation and Insulin Resistance.”

Nature Medicine, vol. 17, no. 2, Feb 2011.

. Romeo, Giulio R et al. “Metabolic Syndrome, Insulin Resistance, and

Roles of Inflammation--Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets.”

Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, vol. 32, no. 8, Aug

2012.

You might also like

- Understanding Immune Health Mayo ClinicDocument8 pagesUnderstanding Immune Health Mayo ClinicCarmel HarelNo ratings yet

- Jay Davidson Symptoms of A Parasitic InfectionDocument4 pagesJay Davidson Symptoms of A Parasitic InfectionNaga BalaNo ratings yet

- Biodiversity of Micro-OrganismsDocument32 pagesBiodiversity of Micro-Organismsapi-20234922250% (2)

- The Essential Guide To Calming Lyme-Induced InflammationDocument7 pagesThe Essential Guide To Calming Lyme-Induced InflammationDorian GrayNo ratings yet

- Trovanje HranomDocument14 pagesTrovanje HranomLamija EmricNo ratings yet

- Autoimmune Diseases: Immune SystemDocument11 pagesAutoimmune Diseases: Immune Systemmaria nataliaNo ratings yet

- HKDSE Biology Part 3 Health & DiseasesDocument17 pagesHKDSE Biology Part 3 Health & DiseasesTSZ YAN CHEUNGNo ratings yet

- Reporting ScienceDocument20 pagesReporting ScienceYasuhiro Hinggo EscobilloNo ratings yet

- Ebook Top 26 Shopping List Supermarket Foods 1Document19 pagesEbook Top 26 Shopping List Supermarket Foods 1Dragica BernotNo ratings yet

- Arthritis RheumatoidDocument15 pagesArthritis Rheumatoidputri rahmadaniNo ratings yet

- Lyme Disease: Submitted byDocument6 pagesLyme Disease: Submitted byhsmolenggeNo ratings yet

- Leaky Gut: The Guide To Treating The Source of Allergies, Joint Pain, Digestive Diseases and MoreDocument15 pagesLeaky Gut: The Guide To Treating The Source of Allergies, Joint Pain, Digestive Diseases and Moresurveytryer2No ratings yet

- Toxic Mold It May Be Harming Your Health More Than You Know Eguide 2555Document17 pagesToxic Mold It May Be Harming Your Health More Than You Know Eguide 2555Petite PoubelleNo ratings yet

- Diseases and VaccinesDocument37 pagesDiseases and Vaccinesraghu ramNo ratings yet

- What Makes You Ill: Made By: Amna AmeenDocument7 pagesWhat Makes You Ill: Made By: Amna Ameenamna ameen StudentNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Disease and Vaccines What Is A Disease?Document2 pagesIntroduction To Disease and Vaccines What Is A Disease?Sue Adames de VelascoNo ratings yet

- Disorders of NSDocument4 pagesDisorders of NSThe KhanNo ratings yet

- Fibromyalgia: The complete guide to fibromyalgia, understanding fibromyalgia, and reducing pain and symptoms of fibromyalgia with simple treatment methods!From EverandFibromyalgia: The complete guide to fibromyalgia, understanding fibromyalgia, and reducing pain and symptoms of fibromyalgia with simple treatment methods!Rating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (2)

- Final Product 2024-05-01 16 06 36Document12 pagesFinal Product 2024-05-01 16 06 36api-711508569No ratings yet

- Diseases and VaccinesDocument22 pagesDiseases and VaccineslakshNo ratings yet

- 6246bb700cf2ee69840e3596 OriginalDocument24 pages6246bb700cf2ee69840e3596 Originalsoma5koshasNo ratings yet

- Margaret Christensen Got Mold Now What Final EditDocument5 pagesMargaret Christensen Got Mold Now What Final EditMarcelo FernandezNo ratings yet

- Guillain Barré SyndromeDocument20 pagesGuillain Barré Syndromelourdes kusumadiNo ratings yet

- CandidaguideDocument12 pagesCandidaguideNica norNo ratings yet

- Lyme Disease 1Document1 pageLyme Disease 1api-547400638No ratings yet

- Autoimmune Disorders: Description of The DisabilityDocument6 pagesAutoimmune Disorders: Description of The DisabilityCemara Boro SaestiNo ratings yet

- Autoimmune GuidebookDocument20 pagesAutoimmune Guidebookedurodica7No ratings yet

- Nerve Pain and Nerve Damage 2Document17 pagesNerve Pain and Nerve Damage 2Ryan BediNo ratings yet

- Lyme Disease 1Document14 pagesLyme Disease 1api-677928137No ratings yet

- Margaret-Christensen Got Mold Now What UpdatedDocument5 pagesMargaret-Christensen Got Mold Now What UpdatedMirela Olarescu100% (1)

- The Effects of Chronic Stress: Stress Is Your Body's Way of Responding To Any KindDocument3 pagesThe Effects of Chronic Stress: Stress Is Your Body's Way of Responding To Any KindXanthophile ShopeeNo ratings yet

- CB5 - Revision - Summary Filled inDocument3 pagesCB5 - Revision - Summary Filled inSiaNo ratings yet

- Got Mold? Now What?: Hope For Health and HomeDocument5 pagesGot Mold? Now What?: Hope For Health and HomeFlo BorsNo ratings yet

- ACUTE INFLAMMATION VS CHRONIC INFLAMMATION Assignment #2 (CU-1774-2020)Document17 pagesACUTE INFLAMMATION VS CHRONIC INFLAMMATION Assignment #2 (CU-1774-2020)Ali Aasam KhanNo ratings yet

- Black Neon Green Neon Pink Trendy Illustrative Creative Presentation 2Document21 pagesBlack Neon Green Neon Pink Trendy Illustrative Creative Presentation 2Sherry-Ann TulauanNo ratings yet

- Multiple Sclerosis 1.1. Definition: Immunologic DisorderDocument21 pagesMultiple Sclerosis 1.1. Definition: Immunologic Disordergrazelantonette.calubNo ratings yet

- Guillain-Barré Syndrome Fact Sheet - National Institute of Neurological Disorders and StrokeDocument9 pagesGuillain-Barré Syndrome Fact Sheet - National Institute of Neurological Disorders and StrokeCarl MacCordNo ratings yet

- Iitei: NieieiircDocument1 pageIitei: Nieieiircapi-21190143No ratings yet

- PBL 1 ResultDocument11 pagesPBL 1 ResultNabilla MahdiNo ratings yet

- Parasites and SusceptibilityDocument13 pagesParasites and SusceptibilityCaroline D.No ratings yet

- Chapter 1 DiseasesDocument10 pagesChapter 1 DiseasesQaran PrintingNo ratings yet

- DISEASES FINALDocument29 pagesDISEASES FINALnitishkumarswain2No ratings yet

- RA and FMDocument3 pagesRA and FMSNo ratings yet

- PainDocument5 pagesPainSyamsulAriefNo ratings yet

- Causes and Prevention of DiseasesDocument4 pagesCauses and Prevention of DiseasesSusan Hepzi100% (1)

- 6B-Biology Notes - Diseases and HygieneDocument13 pages6B-Biology Notes - Diseases and HygieneJagrity SinghNo ratings yet

- Depression and CopingDocument18 pagesDepression and CopingAlcesua EalmyelaNo ratings yet

- Tle Lead PoisoningDocument2 pagesTle Lead PoisoningXhaNo ratings yet

- HEALTH 9 QUARTER2 MODULE3 WeeK5-6Document9 pagesHEALTH 9 QUARTER2 MODULE3 WeeK5-6Heidee Basas100% (3)

- University of Northern PhilippinesDocument4 pagesUniversity of Northern PhilippinesCatherine PradoNo ratings yet

- English Final ProjectDocument16 pagesEnglish Final ProjectAry SanucasNo ratings yet

- Yoga 4 Immune SystemDocument33 pagesYoga 4 Immune Systemsukunath100% (1)

- Psy 325 LecturesDocument14 pagesPsy 325 LecturesErika BalaniNo ratings yet

- Virus, Viroids and PrionsDocument29 pagesVirus, Viroids and PrionscatherinejoaquinNo ratings yet

- HEALTH 4TH Q NCD - For Blended LearnersDocument35 pagesHEALTH 4TH Q NCD - For Blended LearnersAlmighty OperyNo ratings yet

- Health Problems Most Common in School Aged ChildrenDocument15 pagesHealth Problems Most Common in School Aged ChildrenAsterlyn ConiendoNo ratings yet

- GR - 9 - Revision Notes - Why We Do Fall IllDocument9 pagesGR - 9 - Revision Notes - Why We Do Fall IllAditi KumariNo ratings yet

- Examples of DrugsDocument29 pagesExamples of DrugsEdwins MaranduNo ratings yet

- Symptoms: What Are The Complications of Insomnia?Document4 pagesSymptoms: What Are The Complications of Insomnia?Mohamad nazrinNo ratings yet

- F&E ExamDocument3 pagesF&E ExamDino PringNo ratings yet

- (Burnett James C.) Tumours of The Breast and TheirDocument78 pages(Burnett James C.) Tumours of The Breast and TheirRajendraNo ratings yet

- Benefit Packages (Private)Document103 pagesBenefit Packages (Private)You Are Not Wasting TIME HereNo ratings yet

- ALU 101 Sample QuestionsDocument4 pagesALU 101 Sample Questionsartlover30No ratings yet

- Case 013: Fever in A Cirrhotic PatientDocument5 pagesCase 013: Fever in A Cirrhotic PatientFitri 1997No ratings yet

- Chaves 2020Document10 pagesChaves 2020Matheus CastroNo ratings yet

- 08-Hand-Arm VibrationDocument35 pages08-Hand-Arm Vibrationjimmy tiarlinaNo ratings yet

- Read Online Textbook Second A Gay Hockey Romance La Storm Book 2 RJ Scott Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument22 pagesRead Online Textbook Second A Gay Hockey Romance La Storm Book 2 RJ Scott Ebook All Chapter PDFrodney.ellison150100% (3)

- MILLETSDocument11 pagesMILLETSVeer VijayNo ratings yet

- ACOG Combined List of TitlesDocument13 pagesACOG Combined List of TitlesLaura RojasNo ratings yet

- Reflection AssignmentDocument5 pagesReflection Assignmentapi-659065431No ratings yet

- Transmission Sars Cov-2Document7 pagesTransmission Sars Cov-2Ikmah FauzanNo ratings yet

- Endomaterial Cancer-1Document28 pagesEndomaterial Cancer-1A.H.ANo ratings yet

- Fat-And Water-Soluble VitaminsDocument9 pagesFat-And Water-Soluble VitaminsJessa Mae OhaoNo ratings yet

- Water and ElectrolytesDocument39 pagesWater and ElectrolytesevbptrprnrmNo ratings yet

- Communicable Diseases HandoutDocument7 pagesCommunicable Diseases Handoutariane100% (1)

- Cefuroxime Drug StudyDocument1 pageCefuroxime Drug StudyACOB, Jamil C.No ratings yet

- Lippincotts Antiarrhythmics 5Document1 pageLippincotts Antiarrhythmics 5Wijdan HatemNo ratings yet

- Week 14 - Leukocyte Abnormalities and Non-Malignant Leukocyte DisordersDocument83 pagesWeek 14 - Leukocyte Abnormalities and Non-Malignant Leukocyte DisordersSheine EspinoNo ratings yet

- Nursing Responsibilities Adverse Effect Indication / Contraindication Mechanism of Action Drug Name IndicationDocument2 pagesNursing Responsibilities Adverse Effect Indication / Contraindication Mechanism of Action Drug Name IndicationOmar IzzoNo ratings yet

- Basic Encoding ActivityDocument3 pagesBasic Encoding ActivityJHOMER CABANTOGNo ratings yet

- Polycythemia: (Primary & Secondary)Document16 pagesPolycythemia: (Primary & Secondary)Vanessa Camille DomingoNo ratings yet

- PA1 HandoutDocument22 pagesPA1 HandoutIligan, JamaicahNo ratings yet

- 7.2 FTAT Coding Registers Case ScenariosDocument25 pages7.2 FTAT Coding Registers Case ScenariosGosa MohammedNo ratings yet

- 47-Article Text-305-1-10-20220731Document10 pages47-Article Text-305-1-10-20220731alyn30274No ratings yet

- ANT Handbook 2023Document84 pagesANT Handbook 2023latibaleni02No ratings yet

- Laporan Intensif 25 April 2021Document21 pagesLaporan Intensif 25 April 2021bosnia agusNo ratings yet

- Avian Influenza H5N1 VirusDocument27 pagesAvian Influenza H5N1 VirusHarsh Purwar100% (3)

- DGHS IPHS Sub-Dist Hosps 31 To 50Document113 pagesDGHS IPHS Sub-Dist Hosps 31 To 50shanmugapriyasankarNo ratings yet

- WEEK 2 Management of Patients With Chest and Lower Respiratory Tract DisordersDocument9 pagesWEEK 2 Management of Patients With Chest and Lower Respiratory Tract DisordersTin tinNo ratings yet