Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reasons

Reasons

Uploaded by

Asfand KhalidOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reasons

Reasons

Uploaded by

Asfand KhalidCopyright:

Available Formats

Contractor’s Financial Estimation

based on Owner Payment Histories

Hanh Tran David G. Carmichael

School of Civil and Environmental School of Civil and Environmental

Engineering, The University of New South Engineering, The University of New South

Wales, Sydney, 2052 NSW Australia Wales, Sydney, 2052 NSW Australia

D.Carmichael@unsw.edu.au

a contractor ’s financial viabilit y is affected by late and incomplete pay -

DOI 10.5592/otmcj.2012.2.4

Research paper ments from the owner . Late and incomplete payments lead to cash flow

uncertainty, additional bank interest, and delays in paying creditors

such as suppliers and subcontractors, and may lead to decreased proj-

ect performance, and possible additional time and cost due to disputes.

The paper presents a method for cash flow and present value analysis

under uncertainty based on an owner’s payment history or estimated

payment characteristics. The paper generalises existing modelling of

uncertainty associated with late and incomplete owner payments to a

range of claim types by the contractor, and different owner types. Aging

contractor claims are analysed for claims submitted on a regular basis

for amounts which may vary depending on project phasing. For each of

the pre-identified typical owner payment practices, the estimated paid

proportions of claims and the steady state distribution of payments in dif-

ferent age categories are established. A present value analysis assesses

project viability from the contractor’s viewpoint. Actual project data are

used to confirm the validity of the method. The intent of the paper is to

assist contractors establish suitable allowances in their tender pricing,

Keywords

to choose a suitable claim/payment schedule and/or to adopt suitable

Cash flow, Markov chains,

administration practices to optimise cash flow. The paper gives a sum-

contractor payment,

mary approach for contractors, providing them with a practical tool in

owner classification

cash flow planning, control and risk management.

hanh tran · da vi d g . ca r m i cha e l · c o n t r a c t o r ’ s f i n a n c i a l e s t i m a t i o n b a s e d o n o w n e r … · pp 481 - 489 481

INTRODUCTION (Tran and Carmichael, 2013), the esti- also serve as a reference tool for project

Cash flow forecasting and cash flow man- mated paid proportions of claims and owners to enhance their relationship

agement are essential but difficult as- the steady state distribution of pay- with contractors. The paper provides

pects of a contractor’s practices; they are ments in different age categories are a practical tool for cash flow planning

central to the wellbeing of a contractor. established. Real project data are used and management; it is a contribution to

Forecasting is also important as a means to confirm the validity of the method. contractor financial planning and risk

to obtain loans, because banks prefer to The aim of the paper is to assist con- management.

lend money to companies that can pres- tractors in establishing a detail cash The paper starts by reviewing related

ent periodic cash flow forecasts (Navon, flow forecast which takes into account studies about claim-payment modelling

1995). However a contractor’s cash flow cash inflow uncertainties due to late and and cash flow estimation and then sum-

is subject to many uncertainties, some of incomplete owner payment behaviour, marises some key results from the litera-

which result from owner payment prac- and cash outflow. As a follow-on, con- ture. The existing literature is modified to

tices. An owner which fully complies with tractors are able to establish suitable incorporate claims that change with proj-

payment terms outlined in the conditions allowances in their tender pricing or to ect phasing. Case study data are used to

of contract makes cash flow management choose a suitable claim/payment sched- demonstrate the cash flow and present

much easier, while an owner which re- ule to optimise cash flow. The paper’s value calculations, taking into account

sponds irregularly and incompletely to method can be used to address risks alternatives in payment time lags to sub-

a contractor’s claims may drive the con- associated with negative cash flow, ad- contractors and mark-up in claims.

tractor’s cash flow to deviate far from ditional bank interest, and disputes,

what had been planned. An understand- leading to more effective cash manage- Background Literature

ing of an owner’s payment practices is, ment by the contractor. Uncertainties in payments leading to

therefore, very useful for a contractor’s Although in some countries there cash flow difficulties have been high-

cash flow planning purposes. exists legislation to protect contractors lighted as a cause of business failures

The paper presents a method for from late and incomplete payments and and escalating disputes (Carmichael,

cash flow and present value (equiva- insolvency of the payer, payment ar- 2002; Carmichael and Balatbat, 2010).

lently present worth) analysis under un- rears are still very common (Wu et al., Some research has attempted to assist

certainty based on an owner’s payment 2011; Brand and Uher, 2010). Owner- in mitigating construction uncertainties

history or estimated payment charac- caused delays and incompleteness in associated with claims and disputes.

teristics. Extending from the original payments have been shown to have a Examples include predicting contrac-

work of Carmichael and Balatbat (2010), large influence on a contractor’s cash tor failure (Russell and Zhai, 1996),

the method gives the change in claim flow and financial viability (Carmichael, evaluating and investing in construc-

payments in weeks/months following 2000, 2002; Carmichael and Balatbat, tion projects under uncertainty (Ho and

claim lodgement. Payments of indi- 2010). Cost and time associated with Liu, 2003), and developing an integrated

vidual claims are accumulated and su- disputes may also place a large burden method for project risk management

perimposed on the planned cash out- on contractors. An example given by El- from the owner’s point of view (del Cano

flows throughout the project, so that Adaway and Kandil (2009) emphasises and de la Cruz, 2002).

a detailed cash flow diagram can be the severe losses to a contractor when Cash flow forecasting is about the

obtained. A present value analysis is it had to wait for a 3-year arbitration distribution of income and expenditure

performed to assess project viability to run its course before recovering the as a function of time (Navon, 1995). It is

from the contractor’s viewpoint. majority of its claim. noted that the majority of existing pub-

Payment time lag to creditors such The method presented in this paper lications about cash flow forecasting

as subcontractors, owner type (repre- can be combined with the Carmichael- focus on expenditure, which is taken

sented by different payment profiles) Balatbat Markov chain formulation of from the project schedule. For exam-

and claim mark-up are analysis vari- owner payments and the classification ple, Navon (1995) introduces a resource-

ables. Claims are allowed to change of owner payment behaviour (Tran et based cash flow estimation, Kenley and

in line with project phasing and typi- al., 2011; Tran and Carmichael, 2012a,b, Wilson (1986, 1989) model project net

cal project S curve behaviour. Aging 2013) to form a complete cash flow anal- cash flow as a logit-transformation of

contractor claims are assumed to be ysis tool. While primarily intended for percentages of project time and cost,

submitted on a regular basis; claim contractors, the method can also be Chen and Chen (2000) integrate a cost

amounts may vary depending on proj- used by subcontractors, suppliers and database and billing activity payments

ect phasing. For each of the pre-identi- consultants when they deal with others of subcontractors into the cash flow es-

fied typical owner payment practices higher in the contractual chain. It may timate, and Kaka and Price (1993) sim-

482 o rga n i za t i o n , te ch n ol o g y a n d ma na ge m e n t i n co nst r u c t i o n · an international journal · 4(2)2012

plify the standard cost-commitment of payment by a certain date and the Extension of the Carmichael-

curve to enable contractors to perform average time to payment. The present Balatbat Formulation

cash flow estimates at the pre-tender- analysis follows this line of thinking but for Calculating Changes

ing stage more readily. Blyth and Kaka allowing for different claim submission in Payments

(2006), Hwee and Tiong (2002), and Ma- schedules that reflect project phasing. The Carmichael-Balatbat formulation

vrostas et al. (2005), among others, use can be used to estimate the change in

a project’s S curve as a guide for es- Background Theory amounts in the transient states follow-

timating cash outflow; an underlying Carmichael and Balatbat (2010) model ing a claim submission. Consider a claim

assumption in these cash flow forecast contractor payments by owners using of value c1. A claim is equivalent to an

models is that payments occur as antici- Markov chains in the following sum- amount (here c1) entering state 0, with

pated pre-project. mary way. zero amounts in the other states 1, 2,

Some studies that discuss changes Let period i = 0 be the time that the …, n. These other states only take val-

in cash inflow are Park et al. (2005), claim is made by the contractor; then ues when transitions between states oc-

Chen et al. (2005), Kaka and Price (1991) periods i = 1, 2, 3, ... represent months/ cur. Accordingly define 1 × n row vector

and Kaka (1996). The model by Park et weeks beyond that time. Let the (tran- C1 = [c1, 0, 0, ..., 0] as the vector of new

al. (2005) allows contractors to incor- sient) states be the amount outstand- state additions. Over one time period, the

porate the time lag between expendi- ing to the contractor beyond period i. amounts in the transient states change

ture and payment of a related cost item. The states reflect the aging amount be- to C1Q, over two time periods to C1Q2 and

Chen et al. (2005) recommend the in- lieved by the contractor to be owed on so on.

clusion of more detailed payment con- the project. Two additional (absorbing) In the following time periods i = 2,

ditions, and differential payment lags states n’ and n are also introduced. n’ 3, ..., (here a month, week, ...), allow

and frequency in order to increase the is the ‘Paid’ state and n is the ‘To be re- claims respectively of c2, c3, .... And so,

accuracy of cost-schedule integrated solved’ state. As noted, states 0, 1, 2, …, using equivalent notation as above, the

cash flow forecasting techniques. Kaka n-1 are referred to as transient states, amount in each transient state contrib-

(1996) mentions payment delays and while states n and n’ are referred to as uted by the latest claim (after 0 time pe-

retention in cash flow calculations, as- absorbing states. riods) is Ci, contributed by the previous

suming that delay is minimal and the Transition probabilities between claim (after 1 time period) is Ci-1Q, con-

work in progress and the value of prog- periods i and i+1 are calculated from, tributed by the claim before that (after

ress claims are equal. 2 time periods) is Ci-2Q2, and so on. The

Doubtful accounts in retail busi- cumulative amount in each transient

nesses are modelled as Markov chains

state contributed by all claims is Ci +

by Cyert et al. (1962) to estimate col- Ci-1Q + Ci-2Q2 + ...

lectibles and the probable time to col- For claims of constant amounts C1 =

lection. The estimates of collectibles C2 = ... = Ci = C, the steady state amount

are then calculated for the case where j, k = 0, 1, 2, ..., n, n’ (1) in each transient state is

monthly inputs of claims vary cyclically

as occurs in retail businesses. There Here α is the amount in state k that is C + CQ + CQ2 + CQ 3 + ... =

are several modifications to and com- transferred from state j between peri- C(1 + Q + Q2 + Q 3 + ...) = CN (2)

ments on the original contribution of ods i and i+1.

Cyert et al. (1962), including Corcoran pjk , for j, k = 0, 1, 2, …, n, n’, com- CN is a 1 x n vector.

(1978), van Kuelen et al. (1981), Bark- prise the elements of an transition ma-

man (1977), Wort and Zumwalt (1985), trix P which is partitioned to give Q (n A similar argument can be used for

Kallberg and Saunders (1983) and Fry- x n) and R (n x 2) matrices. R applies the absorbing states. Of any new claim,

dman et al. (1985). to transitions from transient states to CR will be absorbed, of the preceding

Carmichael and Balatbat (2010) use absorbing states, while Q applies to time period claim CQR will be absorbed,

Markov chains to model late and incom- transitions between transient states. of the time period CQ2R claim before

plete owner payments. States are de- A fundamental matrix N = (1–Q) -1, and that will be absorbed, and so on. That

fined as the period of time by which pay- a matrix NR are then computed. The is, the steady state amount absorbed is

ment is overdue. Transition probabilities first column of NR gives the probabili- CR + CQR + CQ2R + CQ 3R + ... =

are estimated based on summaries of ties of amounts being paid. The second C(1 + Q + Q2 + Q 3 + ...)R = CNR (3)

total project outstanding amounts over column of NR gives the probabilities of

time. The analysis gives probabilities amounts needing resolution. CNR is a 1 x 2 vector.

hanh tran · da vi d g . ca r m i cha e l · c o n t r a c t o r ’ s f i n a n c i a l e s t i m a t i o n b a s e d o n o w n e r … · pp 481 - 489 483

Thus, the claim submission schedule claim of $143.9K in the second month … of $0, $63.6K, $108.4K and so on.

of the contractor can be converted to an gives rise to payments of $0, $96.3K, Figure 1 plots shows the claim-

estimate of future cash inflow, which can $18.3K and $0 in subsequent months. payment relationship for the project,

be combined with planned cash outflow. And continuing, strings of payments of in which the payments are calculated

Actual claim submission schedules can claims in the third, fourth, etc. months using the above extension of the Car-

be used. Alternatively, constant claims can be calculated. Summing the pay- michael-Balatbat formulation.

within project phases may be assumed. ment contributions of each claim leads The total claimed value was ap-

Below, a case study project is used to to the total payments in months 1, 2, 3, proximately $1,134.2K, while the to-

demonstrate the method.

Outstanding amount ($K) at

Case Example A Total claimed amount ($K)

Consider the claims and payment data 1 month 2 months 3 months 4 months

for the construction of noise-reduction 1,134 1,134 375 231 231

walls along a metropolitan railway

line. The project contains 12 progress Table 1 Outstanding claimed amounts at months following claim lodgement –

claims totalling approximately $1.2M. case example A; n = 4

The project duration was approximately

12 months. Two progress claims were 200.0

not paid and the reasons given were

150.0

that the work had not been completed,

or insufficient detail was submitted in 100.0

the progress claim. Table 1 shows the

50.0

summary of the outstanding project

Amount ($K)

money against the number of months 0.0

after claims lodgement.

-50.0 3 5 11 12 13 14 15

Based on the payment profile in Ta-

ble 1, the matrices Q and R can be as- -100.0

sembled according to Carmichael and

-150.0

Balatbat (2010),

-200.0

-250.0 Time (month)

Figure 1: Claim-payment relationship - case example A

10 140

and 9

120

8

Cummulative amount ($M)

7 100

Claim amount ($M)

6

80

5

60

4

Changes in payment

For each unit new claim of $1, the first 3 40

entries of CR, CQR, CQ2R, and CQ 3R are 2

0, 0.669, 0.127 and 0, and these enter 20

1

the ‘Paid’ state in subsequent time pe-

riods. Thus the first claim of $95.0K (in 0

the first month) gives rise to payments 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41

of $0, $63.6K, $12.1K and $0 in subse- Claim number

quent months. Similarly, the second Figure 2: Claims data – case example B

484 o rga n i za t i o n , te ch n ol o g y a n d ma na ge m e n t i n co nst r u c t i o n · an international journal · 4(2)2012

tal payment was less at approximately Claims According to Project and constant as project activities are be-

$903.1K. If this payment scenario had Cumulative Expenditure ing initiated and the project resources

been anticipated, the contractor could A piecewise linear approximation to a mobilised, a middle phase where expen-

have increased claim mark-up in order project cumulative expenditure or proj- diture is high and constant and contrac-

to improve its net cash flow. Such pay- ect S curve will cover most situations. tors could expect to submit claims of

ment information, if available from past Each straight-line portion represents a similar amounts regularly, and a final

projects, can be used to estimate pay- period of claims of constant but differ- phase where expenditure and claims are

ments on future projects. ing amounts. One, two or more straight- low and constant as the project winds

Below, a project S curve is approx- line segments may be appropriate, de- up (Blyth and Kaka, 2006).

imated by piecewise linear portions pending on the fluctuation of claims The data from three projects are

equivalent to claims constant in time over the project duration. The textbook shown here to demonstrate typical

but of differing magnitudes, in order project S curve might be approximated claims practices, and how the cumula-

that cash inflow estimation can be read- by three straight lines - an initial phase tive claims plots may be approximated

ily obtained. where expenditure and claims are low by multiple straight-line segments,

where the number of segments may

12 160 vary from project to project.

Case example B: the construction of

140 a 7 km two-lane grade separated road.

10

41 progress claims were made over a

120

total duration of 32 months (Figure 2).

Cummulative amount ($M)

8 Because of the peak claims either side

Claim amount ($M)

100

of small claims, the cumulative claim

6 80 schedule of this project may require ap-

proximating by several segments.

60

4 Case example C: the construction of

40 a rural highway including earthworks,

drainage, pavements, road furniture

2

20 and traffic management. The 22 prog-

ress claims are shown in Figure 3. This

0 cumulative plot might be approximated

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22

by several segments, or more severely

Claim number by one segment.

Figure 3: Claims data – case example C Case example D: the refurbishment

of a city building with total cost of ap-

10 60 proximately $60M and duration of ap-

proximately 20 months. The cumulative

9

claims given in Figure 4 might be ap-

50

8 proximated by two straight segments

either side of the middle of the project.

Cummulative amount ($M)

7

40 The number of straight-line seg-

Claim amount ($M)

6

ments assumed to represent cumula-

5 30 tive expenditure is at the discretion of

the contractor. Stylised assumptions, in

4

20 order to simplify the calculations, how-

3 ever might be in terms of:

2 XX One straight-line (constant slope) seg-

10

ment over the entire project.

1

XX Two straight-line segments where the

0 change occurs near project midpoint.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

XX Three straight-line segments with the

Claim number larger claims in the middle part of

Figure 4: Claims data – case example D the project.

hanh tran · da vi d g . ca r m i cha e l · c o n t r a c t o r ’ s f i n a n c i a l e s t i m a t i o n b a s e d o n o w n e r … · pp 481 - 489 485

2.0

1.5 Payment

1.0

0.5

Amount ($)

0.0

-0.5

-1.0

-1.5 Claim

-2.0 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37

Time (months)

Figure 5: Case example A extension; payment-claim relationship based on unit claims for the first 9 and last 9 months,

and twice this for the middle 18 months

Nonlinear segments can also be 3 and 4 are $0, $0.669, $0.127 and $0, out the project. The mark-up of 17.6% is

assumed in place of linear segments, respectively. The payment-claim rela- not high enough to give a positive pres-

for example by using quadratic or ex- tionship is plotted in Figure 5. ent value as the contractor would like. The

ponential functions. Numerical experi- minimum mark-up that needs to be ap-

ments conducted by the authors show Present Value plied in order to have a non-negative pres-

that the difference in the results be- Let the net cash flow, the difference be- ent value is of interest to the contractor.

tween linear and nonlinear assumptions tween the payments and the expendi- Figure 6 shows a range of mark-

is negligible. In the steady state there ture at each time period, i = 0, 1, 2, ... ups and the associated present value

is almost no difference in the values be xi. The present value (PV) is the sum amounts. It is seen that the contractor

of the matrix NR or the vector CNR be- of the discounted xi, needs to adopt at least a 27% mark-up

tween the assumptions of linear or non- (value at the intersection of the present

linear segments. Accordingly the extra value plot and the horizontal axis) in or-

accuracy that might be thought possible der to have a non-negative present value.

through the use of nonlinear approxi-

mations is not there; as well, it comes Effect of delaying payments to creditors

with increased burdens of mathematical where r is the monthly discount rate on contractor’s cash flow

understanding and computational load. and m extends until the last payment In order to improve present value, the con-

is received. tractor may consider the option of delaying

Estimation for a Future Project Consider the values as in Figure 5. payments to creditors such as subcontrac-

– Case Example A Extension The steady state payment to the ‘Paid’ tors and suppliers. This delays cash out-

Assume that the owner payment practices state is $0.796. Since the actual cash flows. Different time lags in payments to

of case example A apply, but now add the outflow each month is 85% of each claim, creditors can be examined by shifting the

following new (future) project specifics. the contractor’s net cash flow in each of cash outflows to the right.

There are 36 monthly progress claims, the first 36 months is negative. The non- Consider the situation (in the same

where the first 9 claims, the next 18 claims discounted total payment is $42.98 while case example) in which the contractor de-

and the last 9 claims have ratios of 1:2:1. the non-discounted total expenditure is lays its cash outflow by one month, then

The claims submitted include a mark-up $45.90. Based on a monthly discount the present value for a 17.6% mark-up be-

(17.6%) to account for overheads; the ac- rate of 1%, the present value of the net comes -$2.50. To make the present value

tual spending of the contractor is 85% of cash flow is -$2.90. non-negative, a 26% mark-up is required.

what it is being claimed. The contractor Delaying cash outflow by a further month,

pays for the work as it is done irrespective Effect of mark-up on present a 25% mark-up is required to bring the

of getting any payment from the owner. value present value to a positive amount ($0.13).

For each unit or $1 claim, the change The above analysis shows that the contrac- This may assist the contractor’s bid to be

in payments in subsequent months 1, 2, tor has a negative net cash flow through- more competitive.

486 o rga n i za t i o n , te ch n ol o g y a n d ma na ge m e n t i n co nst r u c t i o n · an international journal · 4(2)2012

Figure 7 shows how the present value Typical owner payment Average payment in

changes for different time lags in paying behaviour Owner Type 2 months (standard

creditors, assuming a 25% mark-up. A study of the classification of owner deviation)

The effect on present value of delay- payment behaviour by Tran and Carmi- 1 0.54 (0.24)

ing the cash outflow is more apparent chael (2013) established that there are

2 0.27 (0.1)

when the discount rate is higher. With six main types of owners when char-

a discount rate of 1.5% per month, the acterised in terms of their late and in- 3 0.70 (0.15)

minimum mark-up required to have a complete payment histories. Owners 4 0.34 (0.13)

non-negative present value for delays are classified according to three pa-

5 0.76 (0.11)

of 0, 1, and 2 months is approximately rameters representing uncertainties

26%, 25% and 24%, respectively. in payments, namely, the proportion 6 0.80 (0.11)

The above example shows the con- of total amount paid within a certain

Table 2 Average payment in 2-month

tractor the impact of mark-up choices and time frame, the time following the sub-

period following claim submission,

creditor payment policies on its finances. mission of the claim to the initial pay-

as a proportion of total claimed

This may assist, for example in being ment made, and the consistency in the

amount, of the six representative

more competitive at tendering time, or promptness in responding to each in-

owner types of Tran and Carmichael

in administering funds during a project. dividual claim.

(2013)

4.00 Accordingly, it is shown that owners

with incomplete payment histories fall

within one of six levels of practice: from

2.00 poor – Type 1 to excellent – Type 6 (Tran

and Carmichael, 2013). The anticipated

Present value

0.00 payment in terms of proportion of to-

tal claimed amount, for example in 2

10 20 30 40 months following claim submission,

-2.00 for each typical owner type is shown

in Table 2.

For owners Type 1, Type 2 and Type 4,

-4.00

given that the steady state paid amount

in the 2-month allowance is no more than

-6.00 Percent mark-up 60% of the claim, the contractor’s real

expenditure should be lower than 60%

Figure 6: Effect of mark-up on PV - case example A extension of its claimed amount in order to have

a positive monthly net cash flow. This

0.60

implies a mark-up of more than 100%.

Therefore, such owners are not desirable

0.40 to work for. Owners Type 5 and Type 6

have steady state payments equal to 76%

0.20 and 80% of the claimed amount, respec-

0 month 1 month

Present value

tively. Hence mark-ups of at least 31.5%

0.00

and 25%, respectively, are required in or-

2 months 3 months

-0.20 der to have a positive present value when

working with these owner types. Owner

-0.40 Type 3 may also be suitable to work for,

but a contractor might also simultane-

-0.60

ously consider other practices such as

-0.80 Time of payment to creditors (month) front-end loading or up-front payments.

The classification of owner payment

Figure 7: Present value based on different payment time lags to creditors; behaviour allows contractors to per-

25% mark-up, 1% monthly discount rate - case example A extension form an analysis based on the identi-

hanh tran · da vi d g . ca r m i cha e l · c o n t r a c t o r ’ s f i n a n c i a l e s t i m a t i o n b a s e d o n o w n e r … · pp 481 - 489 487

fied type of the owner, derived from the 4. For each claim, calculate the values ent project phases as demonstrated

contractor’s own experiences or others’ of CR, CQR, CQ2R, ..., CQn-1R, where C in case examples B, C and D. The con-

experiences. The requirement of hav- = [c, 0, ..., 0] is a 1×n vector and c is tractor may also examine different op-

ing specific historical owner payment the amount of the claim. These are tions in claim submission schedules,

data can be eased, yet the result of the payments in the weeks or months fol- taking into account any possible front-

analysis remains practical. For exam- lowing claim lodgement. end loading. The methodology remains

ple, consider a contractor working with 5. Add claim payments to the cash out- the same.

an owner Type 6. Based on the antici- flow diagram to produce a complete The analysis is not only applicable

pated payment practices of this owner cash flow diagram. to owners with incomplete payment his-

(as given in Table 2) and the assumed fu- 6. Perform a present value analysis. Ex- tories, but also applicable to complete

ture project scenario as in Figure 5, the amine changes in assumptions on payment situations as identified in Tran

contractor is advised to adopt at least mark-up, discount rate and payment and Carmichael (2013). Based on knowl-

a 25.5% mark-up, assuming payments time lag to creditors in order to as- edge of the timing of payments from

to creditors are not delayed. The mark- sist decision making on tendering the owner, the contractor can perform

up can be reduced to 23.9%, 22.7% policy and/or project administration the same analysis to estimate the in-

and 21.5% respectively for 1-, 2- and practices. crements in payments following claim

3-month payment time lags to creditors. lodgement and feed this into the cash

The contractor, based on this analysis, Conclusion flow diagram. Because claims are paid

can also modify its cash flow diagram The paper provides a practical way for a completely, the timing of payments may

by unbalancing its claims schedule to contractor to perform financial calcula- not largely affect the present value, but

give a further reduction in the mark-up, tions based on past payment experience it still gives very useful information

thereby improving its competitiveness. with an owner, or estimates of an own- about the monthly/weekly cash flow of

er’s payment practices. The contractor the contractor.

Summary of the Approach for a is able to forecast future cash flows and Future research. The analysis pre-

Contractor hence potential project profitability. The sented in this paper could be extended

The above development is summarised method is best applied pre-tender when by considering different claim sched-

for the purpose of being implemented by simple and quick cash flow estimates ules made by the contractor in an up-

contractors (as well as subcontractors, are required. It can also be used dur- coming project. Instead of assuming

suppliers and consultants when deal- ing a project to understand the cash the cash outflow being constant over

ing with others higher in the contractual position of the contractor, or to adjust certain project phases, cash outflow

chain). The method requires no more than claims practices. estimated from actual project sched-

a summary or estimate of outstanding For each owner type, the method ules could be used to estimate payment

project money against time after claim allows contractors to: portions and timing. Another extension

lodgement from a past project. All cash XX Calculate the payment expectancy of the research could be incorporating

flow and present value calculations can for individual claims, including incre- probabilistic cash flow forecasts into

be readily done using a spreadsheet. ments in payments in weeks/months the analysis, taking into account un-

1. Decide on a relevant time period and following claim lodgement. certainty associated with discount rate,

how many time periods must pass be- XX Generate a cash flow diagram by look- project schedules and investment life

fore a claim is conceded as needing ing at a series of claims. spans. The whole analysis could be inte-

resolution. Based on past projects or XX Perform a present value analysis of grated into a spreadsheet tool requiring

estimates, summarise the outstand- payments and expenditure, consid- only user inputs of a summary of owner

ing amounts against time since claim ering various possible time lags in historical payment data, and a future

lodgement. Estimate the entries of the cash outflow to creditors, discount cash outflow schedule. The spread-

matrix P in the Markov chain formula- rates and mark-ups, and hence de- sheet tool would allow the contractor

tion (Carmichael and Balatbat, 2010). cide on the most suitable bidding and to examine the effect of tardy payments

2. Calculate the submatrices Q and R. claim practices. from the owner, possible changes in

3. Generate a cash outflow diagram The method permits a number of dis- discount rates and payment policies to

based on the project schedule. Sim- cretionary parameters including choice creditors on its net cash flow and net

plify the cash outflow diagram by al- in time periods, and choice in time lags present value. The classification of typi-

lowing constant claims over project in payment to creditors. The cash out- cal owner payment behaviour could be

phases, if detailed estimation is not flow calculations may be simplified by incorporated in the analysis tool for

available. allowing constant claims over differ- quick and simple estimation.

488 o rga n i za t i o n , te ch n ol o g y a n d ma na ge m e n t i n co nst r u c t i o n · an international journal · 4(2)2012

References Frydman, H., Kallberg, J. G. and Kao, D. (1985), Tran, H. and Carmichael, D. G. (2012a), The

Barkman, A. I. (1977), Estimation in accounting Testing the adequacy of Markov chain and Likelihood of Subcontractor Payment;

and auditing using Markov chains, Mover-Stayer models as representations of Downstream Progression via the Owner and

The Journal of Accountancy, 144 (6), 75-79. credit behaviour, Operations Research, Contractor, Journal of Financial Management

Blyth, K. and Kaka, A. (2006), A novel multiple 33 (6), 1203-1214. of Property and Construction, 17 (2) ), 135-152.

linear regression model for forecasting Hwee, N. G. and Tiong, R. L. K. (2002), Model of Tran, H. and Carmichael, D. G. (2012b),

S-curves, Engineering, Construction and cash flow forecasting and risk analysis for Stationarity of the Transition Probabilities

Architectural Management, 12 (1), 82-95. contracting firms, International Journal of in the Markov Chain Formulation of Owner

Brand, M. C. and Uher, T. (2010), Follow-up Project Management, 20 (5), 351-363. Payment Histories on Projects, Australian

empirical study of the performance of the Ho, S. P. and Liu, L. Y. (2003), How to Evaluate and New Zealand Industrial and Applied

New South Wales construction industry security and Invest in Emerging A/E/C Technologies Mathematics Journal, 53 (C69-C89).

of payment legislation, International Journal of under Uncertainty, Journal of Construction Tran, H. and Carmichael, D. G. (2013), A

Law in the Built Environment, 2 (1), 7-25. Engineering and Management, 129 (1), 16-24. Contractor’s Classification of Owner Payment

Carmichael, D. G. (2000), Contracts and Kaka, A. P. (1996), Towards more flexible and Practices, Engineering, Construction and

International Project Management, accurate cash flow forecasting, Construction Architectural Management 20 (1)., accepted for

A A Balkema, Rotterdam. Management and Economics, 14 (1), 35-44. publication, to appear 2013.

Carmichael, D. G. (2002). Disputes and Kaka, A. P. and Price, A. D. F. (1991), Net cash Tran, H., Carmichael, D. G. and Balatbat,

International Projects, A A Balkema, flow models: are they reliable, Construction M. C. A. (2011). Tree form classification of

Rotterdam. Management and Economics, 9 (3), 291-308. owner payment behaviour. Proceedings of the

Carmichael, D. G. and Balatbat, M. C. A. (2010), Kaka, A. P. and Price, A. D. F. (1993), Modelling 4th International Conference on Construction

A contractor’s analysis of the likelihood standard cost commitment curves for Engineering and Project Management, Sydney

of payment of claims, Journal of Financial contractors’ cash flow forecasting, 16-18 February 2011, University of New South

Management of Property and Construction, Construction Management and Economics, Wales, Sydney, Australia.

15 (2), 102-117. 11 (4), 271-283. van Kuelen, J. A. M., Spronk, J. and Corcoran,

Chen, H. L. and Chen, W. T. (2000). An interactive Kallberg, J. G. and Saunders, A. (1983), Markov A. W. (1981), On the Cyert-Davidson-Thompson

cost-schedule/payment schedule prototype chain approaches to the analysis of payment doubtful accounts model, Management

integration model for cost-flow forecasting behaviour of retail credit customers, Financial Science, 27 (1), 108-112.

and controlling. 17th International Association Management, 12 (2), 5-14. Wort, D. H. and Zumwalt, J. K. (1985), The trade

for Automation and Robotics in Construction. Kenley, R. and Wilson, O. D. (1986), A construction discount decision: a Markov chain approach,

IAARC, Taipei, Taiwan. project cash flow model—an idiographic Decision Sciences, 16 (1), 43-56.

Chen, H. L., O’Brien, W. J. and Herbsman, approach, Construction Management and Wu, J., Kumaraswamy, M. M. and Soo, G. K.

Z. J. (2005), Assessing the accuracy of Economics, 4 (3), 212-232. L. (2011), Dubious benefits from future

cash flow models: the significance of Kenley, R. and Wilson, O. D. (1989), A construction exchange: an explanation of payment arrears

payment conditions, Journal of Construction project net cash flow model, Construction from ‘continuing clients’ in Mainland China,

Engineering and Management, 131 (6), Management and Economics, 7 (1), 7-18. Construction Management and Economics,

669-676. Mavrotas, G., Caloghirou, Y. and Koune, J. (2005), 29 (1), 15-23.

Corcoran, A. W. (1978), The use of exponentially- A model on cash flow forecasting and early

smoothed transition matrices to improve warning for multi-project programmes:

forecasting of cash flows from accounts application to the Operational Programme

receivables, Management Science, for the Information Society in Greece,

24 (7), 732-739. International Journal of Project Management,

Cyert, R. M., Davidson, H. J. and Thompson, 23 (2), 121-133.

G. L. (1962), Estimation of the Allowance Navon, R. (1995), Resource-Based Model for

for Doubtful Accounts by Markov Chains, Automatic Cash-Flow Forecasting, Construction

Management Science, 8 (3), 287-303. Management and Economics, 13 (6), 501-510.

del Cano, A. and de la Cruz, M. P. (2002), Park, H. K., Han, S. H. and Russell, J. S. (2005),

Integrated Methodology for Project Risk Cash Flow Forecasting Model for General

Management, Journal of construction Contractors Using Moving Weights of Cost

engineering and management, 128 (6), Categories, Journal of Management in

473-485. Engineering, 21 (4), 164-172.

El-Adaway, I. H. and Kandil, A. A. (2009), Russell, J. S. and Zhai, H. (1996), Predicting

Contractors’ Claims Insurance: A Risk contractor failure using stochastic dynamics

Retention Approach, Journal of construction of economic and financial variables, Journal of

engineering and management, construction engineering and management,

135 (9), 819-825. 122 (2), 183-191.

hanh tran · da vi d g . ca r m i cha e l · c o n t r a c t o r ’ s f i n a n c i a l e s t i m a t i o n b a s e d o n o w n e r … · pp 481 - 489 489

You might also like

- Business Communication and Character 11Th Edition Amy Newman Full ChapterDocument67 pagesBusiness Communication and Character 11Th Edition Amy Newman Full Chapterhelena.williams785100% (7)

- CREFC CMBS 2 - 0 Best Practices Principles-Based Loan Underwriting GuidelinesDocument33 pagesCREFC CMBS 2 - 0 Best Practices Principles-Based Loan Underwriting Guidelinesmerlin7474No ratings yet

- BIM, A Case Study On BIMCHAINDocument10 pagesBIM, A Case Study On BIMCHAINAsfand KhalidNo ratings yet

- Objectives of Project Finance ModelsDocument86 pagesObjectives of Project Finance ModelsAlavaro Jaramillo100% (1)

- API 4G Inspections PDFDocument20 pagesAPI 4G Inspections PDFrabeemhNo ratings yet

- Important Principles of Labor LawDocument14 pagesImportant Principles of Labor LawPal Wa100% (2)

- B10900182S219Document5 pagesB10900182S219vincent rotichNo ratings yet

- ContractorsSatisfactnJFMPC PDFDocument11 pagesContractorsSatisfactnJFMPC PDFHEER MENDANINo ratings yet

- Assessment of Credit Risk in Project FinanceDocument9 pagesAssessment of Credit Risk in Project FinanceJalpesh PitrodaNo ratings yet

- Cash FlowDocument7 pagesCash Flowtine.torio05No ratings yet

- 1private Power ProjectDocument3 pages1private Power Projectravesh_georgeNo ratings yet

- Construction Project Payments:: Fundamental Challenges & SolutionsDocument6 pagesConstruction Project Payments:: Fundamental Challenges & SolutionsVimarshi KasthuriarachchiNo ratings yet

- Ykvn Project Finance For Vietnam Energy Generation Asia Mena by Eli Mazur Nguyen Van Hai Ho Van KhanhDocument5 pagesYkvn Project Finance For Vietnam Energy Generation Asia Mena by Eli Mazur Nguyen Van Hai Ho Van KhanhVu HuongNo ratings yet

- Disputes and Charge Backs White Paper - Rob Hadden UnlockedDocument8 pagesDisputes and Charge Backs White Paper - Rob Hadden Unlockedpymnts1No ratings yet

- Contractor, S Cash FlowDocument9 pagesContractor, S Cash Flowvihangimadu100% (2)

- Progress Payment TimingDocument15 pagesProgress Payment TimingadithyNo ratings yet

- Construction FinanceDocument14 pagesConstruction FinanceReginaldNo ratings yet

- Performance Bond Article - d4Document2 pagesPerformance Bond Article - d4MeeraTharaMaayaNo ratings yet

- Report On Payment Delays in Sri Lankan Construction IndustryDocument10 pagesReport On Payment Delays in Sri Lankan Construction Industrychamil_dananjayaNo ratings yet

- Tsys TDR WPDocument8 pagesTsys TDR WPpymnts1No ratings yet

- Applying Internal Controls Skills On Construction Projects by Alexia Nalewaik, CCE MRICSDocument4 pagesApplying Internal Controls Skills On Construction Projects by Alexia Nalewaik, CCE MRICSMwesigwa DaniNo ratings yet

- Planning Cash FlowDocument9 pagesPlanning Cash FlowWaleed AlkhafajiNo ratings yet

- Finance Project ProposalDocument7 pagesFinance Project Proposalsoumya.mettagalNo ratings yet

- ICRA Rating Methodology: Construction CompaniesDocument11 pagesICRA Rating Methodology: Construction Companieshesham zakiNo ratings yet

- Planning and Optioneering: CostingDocument3 pagesPlanning and Optioneering: CostingGamini KodikaraNo ratings yet

- Cost Reimbursable Contract Construction ProcurementDocument1 pageCost Reimbursable Contract Construction ProcurementMikeNo ratings yet

- Estimating and Tendering For Construction Work - (14 Sub-Contractors and Market Testing)Document8 pagesEstimating and Tendering For Construction Work - (14 Sub-Contractors and Market Testing)mohamedNo ratings yet

- A9 - Financing PDFDocument5 pagesA9 - Financing PDFadnmaNo ratings yet

- Factors in Uencing Building Contractors' Pricing For Time-Related Risks in TendersDocument12 pagesFactors in Uencing Building Contractors' Pricing For Time-Related Risks in Tendersnoahyosef456No ratings yet

- Procurement Guide: CHP Financing: 1. OverviewDocument9 pagesProcurement Guide: CHP Financing: 1. OverviewCarlos LinaresNo ratings yet

- How To Achieve The Highest Long-Term PV Project ValuesDocument14 pagesHow To Achieve The Highest Long-Term PV Project Valuesjmgarci33No ratings yet

- BASAK-G-Tuning Into Your ClientDocument6 pagesBASAK-G-Tuning Into Your ClientegglestonaNo ratings yet

- Systems Analysis of Project Cash Flow Management StrategiesDocument17 pagesSystems Analysis of Project Cash Flow Management StrategiessatgasppksNo ratings yet

- Presentation On New Islamabad International AirportDocument16 pagesPresentation On New Islamabad International AirportAhmar NiaziNo ratings yet

- E-AP-2 - Short-Term Loans and AdvancesDocument7 pagesE-AP-2 - Short-Term Loans and AdvancesAung Zaw HtweNo ratings yet

- Methodology ConstructionDocument11 pagesMethodology ConstructionMIHIR1304No ratings yet

- Credit Risk Analysis Applying Logistic Regression, Neural Networks and Genetic Algorithms ModelsDocument12 pagesCredit Risk Analysis Applying Logistic Regression, Neural Networks and Genetic Algorithms ModelsIJAERS JOURNALNo ratings yet

- P1 QS ReviewerDocument5 pagesP1 QS ReviewerZach GarciaNo ratings yet

- Emerging Issuesin Construction Contract Administrationandtheir Significanceinthe Construction Industry 2Document20 pagesEmerging Issuesin Construction Contract Administrationandtheir Significanceinthe Construction Industry 2Boss VasNo ratings yet

- Preparing A Construction Cash Flow Analysis Using Building Information Modeling (BIM) TechnologyDocument9 pagesPreparing A Construction Cash Flow Analysis Using Building Information Modeling (BIM) TechnologyAHTASHAM ULLAHNo ratings yet

- Exploring Blockchain For MSR TransfersDocument7 pagesExploring Blockchain For MSR TransfersSailesh AkkarajuNo ratings yet

- (080EE15C 9EBB 437D B7BD 66023532CD4D) Arcadis Construction Management 241017Document6 pages(080EE15C 9EBB 437D B7BD 66023532CD4D) Arcadis Construction Management 241017Min Chan MoonNo ratings yet

- 2013-07 Project Organization Due Diligence v0Document2 pages2013-07 Project Organization Due Diligence v0Aayushi AroraNo ratings yet

- Job Description - ConsultantDocument3 pagesJob Description - Consultant8hinoNo ratings yet

- Bavadekar, T. (2020) - Importance of Proper Cost Management in Construction Industry. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology.Document3 pagesBavadekar, T. (2020) - Importance of Proper Cost Management in Construction Industry. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology.beast mickeyNo ratings yet

- 4-June 2017Document16 pages4-June 2017vasilikiNo ratings yet

- Raheel Aamir: How To Avoid Losing The Contractor'S Construction ClaimsDocument20 pagesRaheel Aamir: How To Avoid Losing The Contractor'S Construction ClaimsKhaled AbdelbakiNo ratings yet

- WACC: Practical Guide For Strategic Decision-Making - Part 5: Project Selection - How To Choose The Right Project and Make Effective ComparisonsDocument4 pagesWACC: Practical Guide For Strategic Decision-Making - Part 5: Project Selection - How To Choose The Right Project and Make Effective ComparisonsbuttsahibNo ratings yet

- Combined Heating, Cooling & Power HandbookDocument18 pagesCombined Heating, Cooling & Power HandbookFREDIELABRADORNo ratings yet

- DBSA Responses 1 PDFDocument2 pagesDBSA Responses 1 PDFLeila DouganNo ratings yet

- Hughes and Kabiri Performance Based ContractingDocument40 pagesHughes and Kabiri Performance Based ContractingReyLeonNo ratings yet

- Accenture Collateral Management Offering BrochureDocument16 pagesAccenture Collateral Management Offering BrochureinvHnS ok100% (1)

- Project Finance Summary Debt Rating Criteria-S&P PDFDocument17 pagesProject Finance Summary Debt Rating Criteria-S&P PDFReisha Ananda PutriNo ratings yet

- Week 6 AuditingDocument1 pageWeek 6 AuditingYusef ShaqeelNo ratings yet

- Feasibility Study of Belitung Hotel Project (Case Study PT Xyz)Document11 pagesFeasibility Study of Belitung Hotel Project (Case Study PT Xyz)rikasusanNo ratings yet

- Commercial Bank Examination ManualDocument1 pageCommercial Bank Examination Manualmimu xuNo ratings yet

- Construction Economics and Finance - Cash Flow ManagementDocument50 pagesConstruction Economics and Finance - Cash Flow ManagementMilashuNo ratings yet

- Accenture Auto Equipment Servitization Financing ModelsDocument13 pagesAccenture Auto Equipment Servitization Financing ModelsRendy DjunaediNo ratings yet

- Financial ControlDocument9 pagesFinancial Controlmalika168malikaaaaNo ratings yet

- Financial Modelling of Project Finance Transactions - 1553119075 PDFDocument21 pagesFinancial Modelling of Project Finance Transactions - 1553119075 PDFLay ZhuNo ratings yet

- Quantity Surveyor DutyDocument8 pagesQuantity Surveyor DutyDavid WebNo ratings yet

- Mega Project Assurance: Volume One - The Terminological DictionaryFrom EverandMega Project Assurance: Volume One - The Terminological DictionaryNo ratings yet

- Unlocking Capital: The Power of Bonds in Project FinanceFrom EverandUnlocking Capital: The Power of Bonds in Project FinanceNo ratings yet

- DauntingDocument27 pagesDauntingAsfand KhalidNo ratings yet

- Th4 - Final DFADocument76 pagesTh4 - Final DFAAsfand KhalidNo ratings yet

- Construction Quality Management With BlockchainsDocument16 pagesConstruction Quality Management With BlockchainsAsfand KhalidNo ratings yet

- Inside of Construction SiteDocument2 pagesInside of Construction SiteAsfand KhalidNo ratings yet

- TrustintheConstructionIndustry ALiteratureReviewDocument11 pagesTrustintheConstructionIndustry ALiteratureReviewAsfand KhalidNo ratings yet

- BLZ DatabaseDocument42 pagesBLZ DatabaseAsfand KhalidNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Project Planning and WBSDocument18 pagesIntroduction To Project Planning and WBSAsfand KhalidNo ratings yet

- Bim by Coursera 1Document9 pagesBim by Coursera 1Asfand KhalidNo ratings yet

- Week 4 Applications of ML in SecurityDocument36 pagesWeek 4 Applications of ML in SecurityAsfand KhalidNo ratings yet

- Week 5 Applications of ML in SecurityDocument36 pagesWeek 5 Applications of ML in SecurityAsfand KhalidNo ratings yet

- Purpose List of Machines and Equipment in Test Floor LabDocument10 pagesPurpose List of Machines and Equipment in Test Floor LabAsfand KhalidNo ratings yet

- Qaid by Abdullah Hussain PDFDocument108 pagesQaid by Abdullah Hussain PDFAsfand KhalidNo ratings yet

- FYP ThesisDocument76 pagesFYP ThesisAsfand KhalidNo ratings yet

- Richard Laureano ResumeDocument2 pagesRichard Laureano Resumeapi-726195881No ratings yet

- Year-End Financial Report Jpia 2017-2018Document10 pagesYear-End Financial Report Jpia 2017-2018Froilan Arlando BandulaNo ratings yet

- DRMG 240Document124 pagesDRMG 240Allen Ashburn100% (1)

- Storage For Z L1 Seller PresentationDocument69 pagesStorage For Z L1 Seller PresentationElisa GarciaRNo ratings yet

- Southeast University: Mid Term AssignmentDocument7 pagesSoutheast University: Mid Term AssignmentRiyazul IslamNo ratings yet

- CC Project - Tarik SulicDocument16 pagesCC Project - Tarik SulicTarik SulicNo ratings yet

- Ibanez & Blackman 2016 PDFDocument14 pagesIbanez & Blackman 2016 PDFmayra garzon vargasNo ratings yet

- Mas 10 Exercises For UploadDocument5 pagesMas 10 Exercises For UploadChristine Joy Duterte RemorozaNo ratings yet

- Biomass Torrefaction in Indonesia - March, 2016Document17 pagesBiomass Torrefaction in Indonesia - March, 2016Herman Eenk HidayatNo ratings yet

- 2.1.1.A DesignFlawsDocument2 pages2.1.1.A DesignFlawsEthan SextonNo ratings yet

- 20 Question PeparDocument6 pages20 Question PeparAnonymous 69No ratings yet

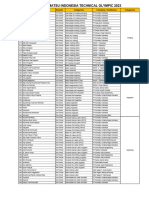

- 12th All Komatsu Indonesia Technical Olympic 2022 Official ResultDocument2 pages12th All Komatsu Indonesia Technical Olympic 2022 Official ResultMarchal KawengianNo ratings yet

- CR Conclusion QuestionsDocument62 pagesCR Conclusion Questionsabhijeet bhaskarNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Globalisation On A Hotels Marketing StrategyDocument10 pagesThe Effect of Globalisation On A Hotels Marketing StrategyAslam Abdullah MarufNo ratings yet

- Consumer Trends 2020Document31 pagesConsumer Trends 2020Vương HạnhNo ratings yet

- AND (B) Both. The Bidder Having Experience, Only of Criteria Mentioned at (A) CanDocument5 pagesAND (B) Both. The Bidder Having Experience, Only of Criteria Mentioned at (A) Canpkb_999No ratings yet

- Synopsis of Hospital Management SystemDocument17 pagesSynopsis of Hospital Management SystemShivraj Cyber100% (1)

- Case Studies - Group Activity InstructionsDocument4 pagesCase Studies - Group Activity InstructionsKissy LorNo ratings yet

- Masaood John Brown - Presentation - v1.1Document54 pagesMasaood John Brown - Presentation - v1.1Hanif Akbar100% (1)

- PJM3Document106 pagesPJM3Sandarsh SDNo ratings yet

- Simon-Kuchers Healthcare It Trends Report 2024Document28 pagesSimon-Kuchers Healthcare It Trends Report 2024coppins98No ratings yet

- ReportDocument11 pagesReportSanjay K ANo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Ethiopian Financial MarketDocument30 pagesChapter 6 Ethiopian Financial Marketyebegashet87% (31)

- ARABIAN - Agreement SMALL - RevisedDocument2 pagesARABIAN - Agreement SMALL - RevisedMarie CanariaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 - Monitoring and Controlling The ProjectDocument41 pagesChapter 7 - Monitoring and Controlling The ProjectAung Khaing MinNo ratings yet

- Ra 11976 EoptDocument2 pagesRa 11976 EoptLGUNo ratings yet

- Unified GCI Form - V2021.0063.01 - Personal Financing - Tawarruq - App Form - V2021.0063.01-ENGDocument9 pagesUnified GCI Form - V2021.0063.01 - Personal Financing - Tawarruq - App Form - V2021.0063.01-ENGYue Wen TradingNo ratings yet