Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Massey Locality

Massey Locality

Uploaded by

elli dramitinouOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Massey Locality

Massey Locality

Uploaded by

elli dramitinouCopyright:

Available Formats

Questions of Locality

Author(s): Doreen Massey

Source: Geography , April 1993, Vol. 78, No. 2 (April 1993), pp. 142-149

Published by: Geographical Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40572496

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Geographical Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Geography

This content downloaded from

147.52.231.39 on Sat, 11 Jun 2022 13:06:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Questions of Locality

Doreen Massey

ABSTRACT: This paper explores issues surrounding studies of locality' and 'place'.

Reasons for the renewed emphasis on such studies are examined, before consideration of

two controversial aspects. The first is the charge of parochialism, which is contested. It

is argued that, when conceived in a particular way, locality studies can be at the heart

of a geography which is truly internationalist, both in its recognition of geographical

uniqueness and difference, and in its analysis of the {unequal) relations which bind

different places together. Secondly methodological issues are examined, and it is argued

that, far from being confined to description, locality studies pose productive theoretical

challenges.

The issue of locality, and of the closely related - indeed sometimes indistinguishable -

concepts of place and region have in the last few years figured prominently on the

geographical agenda. The question of place and locality has been central to a major

programme of research funded by the Economic and Social Research Council.1 There

have been storms of debate about the appropriateness of this focus, about the intellectual

frameworks needed for geographical analysis of such phenomena, and indeed about the

very definition of place/region/locality in the first instance. Finally the notions of place

and locality figure prominently, as geographical concepts and as foci for the organisation

of the teaching of geography, within the National Curriculum.

There are many factors which seem to be important in explaining this new (or renewed)

emphasis. A number of authors have in recent years expressed the view that geography

stood in danger of losing its appreciation of the differences between places and its ability

to explain those differences in real depth. This argument is not merely one which derives

from an emotional attachment to the specificity of place, although it certainly has strains

of that within it; but it has other sources, too. On the one hand there is the argument that

a greater attentiveness to geographical variation, to difference, is a necessary component

of a wider social project of greater comprehension of other parts of the world. Thus

Gregory has written:

one of the raisons d'être of the human sciences is surely to comprehend the 'otherness' of other

cultures. There are few tasks more urgent in a multicultural society and an interdependent world,

and yet one of modern geography's greatest betrayals was its devaluation of the specificities of

place and of people (Gregory, 1989, p. 358).

It is in the context of arguments such as this that calls have recently been made for the

rebirth of (a re-thought) regional geography. Moreover, the reference in the quotation

Doreen Massey is Professor of Geography in the Faculty of Social Sciences at the Open University, Walton Hall,

Milton Keynes MK7 6AA © The Geographical Association, 1993.

142

This content downloaded from

147.52.231.39 on Sat, 11 Jun 2022 13:06:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

GEOGRAPHY 143

from Gregory to "the hum

a larger issue. For 'differ

currently sweeping thro

geographer's attention to di

There are other reasons, to

discipline. These include pe

have been dominant in rece

forms of Marxism) have ten

both in the United Kingdom

and social change have invo

obvious, for instance, th

(Thatcherism', for instance

and result in quite distinct

well), in different parts of

understand the impact an

below the national level and

nature which were an impo

research programme (Mas

greater relevance of locality

integral relations between)

issues, and in ways which l

appreciation of the need to

dynamics of daily life in its local to-ings and fro-ings

I should perhaps declare from the start that this interest

which I share and support. However I do so with some str

borne in mind in what follows. Firstly, I am very wary of

swings of emphasis and interest as people follow them

localities and a new sort of regional geography are not cal

geography at the expense of other things. Indeed, as will

other aspects of geography are absolutely indispensabl

understanding of place. A focus on place/locality/region is

neglected, aspect of 'the compleat geographer'. Secondly, t

provoked considerable discussion, in seminars, conference

disagreement. In the sections below I shall pick up and anal

it seems to me that what their very existence highlights

debate about the way in which we do locality studies. Man

such studies would argue that they are necessarily paro

descriptive in form. I shall argue below not only that the

things but that they should not be, and I shall try to dem

doubt that such dangers exist. The question, then, is how to

A focus on the locality need not be paroc

In educational circles it is sometimes argued that students

of things which are local to them, including - within geo

areas. The argument is made that they are likely to be mo

familiar. I am personally somewhat sceptical of this argum

fascinated by the far-away). But there is no doubt that li

concrete reality of daily life can 'bring messages home' in

course studies of locality can equally well be of places on th

wherever they are they run the danger of being 'parochial

Geography «·) 1993

This content downloaded from

147.52.231.39 on Sat, 11 Jun 2022 13:06:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

144 GEOGRAPHY

locality is one which focuss

identity for that place an

romanticism and nostalgia.

A non-parochial view of place

But there is another way

parochial. This is the view

These links exist in many w

modern era. The sources of

petrol in the garage links in

companies will certainly no

redundancies may be tracea

the local population will di

'undisturbed', most 'local',

steeple rises to honour a

territory.

The point is that there are today very few, if any, places in the world, and certainly

none in the UK, which can be at all satisfactorily understood or explained in isolation

from the wider context, both national and international, in which they are set. The nature

of such links will range across the spectrum of the concerns of human geography, from

economic (through trade, and products, ownership and influence), to political (the impacts

of decisions made elsewhere, perhaps, from Maastricht to the GATT negotiations) to

cultural (the films on at the local cinema or the thoughts of home in the heads of people

as they go about their daily, apparently local, business: thoughts of the North in those

who have come south in search of work, stories of Cyprus heard in the families of those

who emigrated years ago). These things tie one locality to many others in a myriad

different ways. Moreover, they are more than 'links', they are part of the constitution of

the place, part of what gives it its own particular character.

Furthermore, the existence of such links is rarely new, although the nature of them will

have changed over time. Patrick Wright, in his book On Living in an Old Country, writes

of the way in which so many local histories are told: the place was first mentioned in the

Domesday Book, it had ten villanes . . . and so on, through a stately progression of

changes all of which are bounded by the local area itself (Wright, 1985). Such history is

indeed 'parochial', seeing only the place itself. Thus a history of that now-disputed bit of

country called London Docklands could be written as a story of fields giving way to docks

and working-class housing, and then in turn ceding place to high-tech offices, finance-

houses and 'executive' residences. But to tell the history so would be to miss a lot of what

gave the area its shape and its character, and to miss, too, much of the explanation of that

history. For the story of the change from docks to finance houses is also the story about

the area's changing place in the world, from port and processor at the heart of one of the

world's biggest empires to a vital communications and finance link in the chain of late

twentieth-century world cities. In each period the area played a distinct role in a particular

international division of labour. And each period left its mark and traces of the

international links, from street names to the mix of the local population.

The point of thinking of localities in this way is to stress that their formation, and their

character, cannot be understood merely by looking at the place alone. Any serious

understanding of any one place necessitates standing back, taking a broader view, and

setting it in a wider context. In this way even studying one's own local area can be the

opposite of parochial; it can indeed really make more concrete the links between 'us' and

'them', and to understand not only how the local is affected by the global but how the

actions of 'local people' at 'local level' are fully implicated in, and thus have some

responsibility for, events in, and conditions of, people in lands which may often seem

remote.

Geography © 1993

This content downloaded from

147.52.231.39 on Sat, 11 Jun 2022 13:06:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

GEOGRAPHY 145

For 'links' with other places

interdependence which is

domination, subordination,

analysis of these one can un

good deal of what make it wh

The identity of place

For if all this is so, then th

also be set in a wider contex

relations with other places.

them in order to discover w

function); they are also pa

understand what it is to be

the UK, without deeply appr

played upon the character o

tea was born out of the act

Caribbean.

It is in this way that interdependence contributes to uniqueness (Open University, 1985).

Indeed interdependence and uniqueness can be understood as two sides of the same coin,

in which two fundamental geographical concepts - uneven development and the identity of

place - can be held in tension with each other and can each contribute to the explanation

of the other.

Moreover, and in part because of this, the identities of places are constantly changing as

new products of history, new effects of the role of the place in the wider scheme of things,

are added to the old. What is meant by talk of 'the real Lancashire'? A picture

immediately rises into view of proud cotton mills and huddled terraces (some variant of a

Lowry painting); yet cotton has been important for only a hundred and fifty years of the

history of that part of the country, and dominant for even less.

A sense of place

Yet when one refers to a 'sense of place' it is not these analysed histories which are so

relevant but rather the feelings which people carry round with them. There are many

others who have written widely on this issue, and Stephen Daniels considered it recently in

Geography (Daniels, 1992). But there are two aspects of the debate which relate to that

over localities. Firstly, there will in all likelihood be more than one 'sense' of any

particular place. In the Hackney of which Patrick Wright was writing the white working-

class has a very different notion of the area, different meeting places and routes through

it, even different understandings of what is its past, from either the ethnic-minority

communities or the gentrifying middle-classes. In Docklands the working class of the Isle

of Dogs thinks in terms of Millwall while the incoming yuppies compose images of status,

of pioneering, and of 'the Venice of the North'. Even in localities which appear seamless,

such as mining villages, a woman's sense of the place, for instance, is likely to be very

different from a man's. The sense of what is 'Britain' to a second-generation inhabitant of

Brixton is likely to be in contrast to that of denizens of the villages of the Cotswolds.

Moreover while sometimes those distinct senses of a place can happily coexist, through

mutual ignorance or through regular patterns of negotiation, sometimes they may be

contradictory and even erupt into conflict. In Hackney the memories of the white working

class, the images they bring to mind when thinking of how the place ought to be ('the real

Hackney'), are rudely interrupted by the unwanted arrival of new groups, both ethnic-

minority and middle-class. In Docklands the occasional bouts of spray-painting of

expensive cars are witness to the sharp end of a clear conflict not only about what is, but

about what should be, the identity of the area and its dominant sense of place.

Geography © 1993

This content downloaded from

147.52.231.39 on Sat, 11 Jun 2022 13:06:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

146 GEOGRAPHY

I ;iii. 1. Reminders of Fimpire in Ki

Further, and this is the second point, a sense of place - just as much as the

understanding of its economic or demographic structure or the 'objective' analysis of its

identity - can be in part constructed out of consciousness of the locality's place in the

world. When, on Saturday mornings I walk down Kilburn High Road to do my shopping,

the IRA graffiti and the Irish pubs, the Indian sari shop and the notices for Muslim

gatherings, as well as the constant snarl of traffic which tells that this is the main route

from the centre of London to the Ml, all make it impossible to think of Kilburn without

linking it in to centuries of the history of the British Empire and places half a world away

(Massey, 1991b) (Fig. 1). The very feel of Kilburn, my sense of it as a unique place, is in

part constructed precisely out of its global (as well as wider national) connections.

Moreover, such a sense of place, constructed through interaction rather than through

closure, is important to establish. For a sense of place which assumes it is unique and

eternal, and constructed only out of materials found in that place, can be a dangerous

thing. At one end of the spectrum, too coherent and final a sense of place can be used to

keep a community-care hostel out of a well-heeled suburb ("it really doesn't fit in with the

character of the place"). At the other it can lead to nationalist nostalgias and horrors such

as ethnic cleansing.

The challenge for geographers is to retain an appreciation, and an understanding of the

importance, of the uniqueness, of place while insisting always on that other side of the

coin, the necessary interdependence of any place with others.

Description and explanation

Among the criticisms which have been made of locality studies is the charge that

methodologically they rely solely on 'description'. The burden of the accusation is that no

theory is involved. There are many ways in which such a charge should be questioned.

Geography © 1993

This content downloaded from

147.52.231.39 on Sat, 11 Jun 2022 13:06:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

GEOGRAPHY 147

Most evidently, it is many

such thing as 'mere descri

theoretical content. It may w

that it may not even be reco

no such thing as a totally n

significant and of how phen

been developed into a fuller

forms which it can take. Th

precisely incorporates an un

different ways (Daniels, 199

no longer seriously tenable.

unselfconscious description

which it rests, the explanat

stake.

Any serious geographical en

explicit theorising. A simple

Theory and locality studies

Constructing a notion of lo

theoretical challenge. It mea

branches of systematic geogra

At the broad level, that of

world beyond, it is necessar

processes. To understand th

theories of location, to und

labour and broader patterns

the whole context of uneven

may be necessary to go back

(Ireland, maybe, as in the c

study the break-up of Em

migration within the Unite

necessary to be sensitive to b

and at an intra-national lev

words, behoves that we draw

its disposal.

But some of the critics of locality studies accused them of being descriptive mainly on

the simple grounds that they are 'local', which is to say small-scale. This, however, is to

confuse the nature of theory. Theory and explanation does not only concern itself with the

big broad structures, of capital accumulation at the global level for instance or regionally

uneven development at the intra-national. Local, small-scale phenomena are equally

amenable to, and demanding of, theorising. The functioning of local labour markets and

housing markets, the dynamics of gender relations, the functioning of local households

and their dominant structures all require theorising at the specifically local as well as the

broader level, because it is at the local level that many of their most crucial processes

operate.

Explaining the unique

But if none of these criticisms of locality studies as a-theoretical hold water, (or should

not do so if locality studies are well carried out), the final charge is that in the end

particular, individual, places are not amenable to analysis precisely because they are

unique. The hey-day of regional science thinking within geography produced the aphorism

that "there is little one can do with the unique save contemplate it".

Geography (Ο 1993

This content downloaded from

147.52.231.39 on Sat, 11 Jun 2022 13:06:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

148 GEOGRAPHY

The current resurgence of in

One can, of course, contempl

some way towards explainin

indeed unique we would be in

So what are the sources of

address? They are numerous.

means that most broader soci

in fact occur unevenly over

places will be different. Mor

places are the product of the

broader geography than the

from the fact that nowhere

put together quite this set o

England and the rest of inne

together in space, in place, o

yuppies and the manual wor

both groups. This, indeed,

organisation of society has a

juxtapositions which occur in

another component thereby t

The uniqueness of place, of c

here in the sense of a histor

national and international co

differentiation which is part

the uneven articulation of th

histories. Finally, and most im

inexorable playing-out of str

results of human agency but

they have constructed as their

Places as exemplars

There is one more way in w

theoretical debates. This is w

more detail processes which a

as a laboratory for exploring

particular sets of forces or c

of writers (as well, for instanc

modern to a post-modern soc

clearly and in most abundan

times. Most places, if in less

sakes, but as specific exempla

part of the complexities of t

workings.

But what are localities?

The stress that has been laid here on the openness of localities, on their construction on

the basis of links to the outside rather than demarcation from it, inevitably raises the issue

of boundaries. Geographers seem to love drawing boundaries. And yet in principle this

approach to the notion of locality makes any form of boundary-drawing difficult. Rather,

places are best thought of as nets of social relations.

Geography © 1993

This content downloaded from

147.52.231.39 on Sat, 11 Jun 2022 13:06:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

GEOGRAPHY 149

Moreover, what may bes

housing market perhaps, or

the best for another - a stud

will not solve the problem,

may well have different geogr

Localities in the sense discu

being made, always contes

national identity it has recen

Paris, for example, surely

McDonald's outlet in Kyoto

The truth of the statement

be understood as following

an internally-coherent, pris

moulded, over time. This do

notion of conservation or pr

about the terms and nature

take account, not just of t

character was formed in i

organising to resist the comm

where the new residents wil

debate and politics. And deb

futures, are one of the geog

condensed.

NOTE

1. The research programme on The Changing Urban and Regional System, The Economic and Social R

Council. See, for instance, Cooke, 1989.

REFERENCES

Cooke, P. (ed.) (1989) Localities, the Changing studies",

Face of Environment and Planning A, 23, pp.

Urban Britain, London: Unwin Hyman. 267-281.

Daniels, S. (1992) "Place and the geographical Massey, D. (1991b) "A global sense of place",

imagination", Geography, 77, 4, pp. 310-322. Marxism Today, June, pp. 24-29.

Gregory, D. (1989) "The crisis of modernity? Human Open University (1985) Changing Britain, Changing

geography and critical social theory", in Peet, R. World: Geographical Perspectives, a second level

and Thrift, N. (eds.) New Models in Geography: the Geography Course, Milton Keynes: Open

Political Economy Perspective, vol. 2, London: University.

Unwin Hyman, pp. 348-385. Schiller, H.I. (1992) "Fast food, fast cars, fast political

Jackson, P. (1989) Maps of meaning: an Introduction torhetoric", Intermedia, 20, 4-5, pp. 21-22.

Cultural Geography, London: Unwin Hyman. Wright, P. (1985) On Living in an Old Country,

Massey, D. (1991a) "The political place of locality London: Verso.

Geography © 1993

This content downloaded from

147.52.231.39 on Sat, 11 Jun 2022 13:06:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- IHDS - Variables That Which Binds Us - 216p - 230805 - 153158Document216 pagesIHDS - Variables That Which Binds Us - 216p - 230805 - 153158Roberta100% (10)

- Topographical Stories: Studies in Landscape and ArchitectureFrom EverandTopographical Stories: Studies in Landscape and ArchitectureNo ratings yet

- Gieryn, Thomas F. (2000) A Space For Place in SociologyDocument35 pagesGieryn, Thomas F. (2000) A Space For Place in SociologyViviana GualdoniNo ratings yet

- Relational Thinking JonesDocument20 pagesRelational Thinking JonesLewis BlagogieNo ratings yet

- QW-451 Welding THK - June5Document17 pagesQW-451 Welding THK - June5Raj SNo ratings yet

- Gear 3Document16 pagesGear 3poncatoera100% (1)

- Electrical Technology Notes Btech 1st YearDocument193 pagesElectrical Technology Notes Btech 1st Yeardivya ratna100% (2)

- Locality Massey 1993Document9 pagesLocality Massey 1993Paco CuetzNo ratings yet

- Questions of LocalityDocument9 pagesQuestions of LocalitycanazoNo ratings yet

- Paasi 2000 Reoconstruindo Região PDFDocument9 pagesPaasi 2000 Reoconstruindo Região PDFLucivânia DageoNo ratings yet

- Land Terrain TerritoryDocument21 pagesLand Terrain TerritoryLucas EgurenNo ratings yet

- Mubi, A. (2010) On Territorology Towards A General Science of TerritoryDocument22 pagesMubi, A. (2010) On Territorology Towards A General Science of TerritoryAlba VásquezNo ratings yet

- JACKSON 2006 - Thinking GeographicallyDocument6 pagesJACKSON 2006 - Thinking GeographicallyfjtoroNo ratings yet

- Swedish Society For Anthropology and Geography, Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human GeographyDocument15 pagesSwedish Society For Anthropology and Geography, Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human GeographyIssam MatoussiNo ratings yet

- Painter - "Territory-Network"Document39 pagesPainter - "Territory-Network"c406400100% (1)

- Thinking Geographically: Space and PlaceDocument6 pagesThinking Geographically: Space and PlaceTyrese Dre ChettyNo ratings yet

- Theory, Culture & Society: On Territorology: Towards A General Science of TerritoryDocument22 pagesTheory, Culture & Society: On Territorology: Towards A General Science of TerritoryJeinni PuziolNo ratings yet

- Van Houtum y Van Naerssen, 2002 Bordering, Ordering and OtheringDocument13 pagesVan Houtum y Van Naerssen, 2002 Bordering, Ordering and OtheringPablo CaraballoNo ratings yet

- On Territorology Towards A General Science of TerrDocument23 pagesOn Territorology Towards A General Science of Terrca taNo ratings yet

- Lewthwaite EnvironmentalismDeterminismSearch 1966Document24 pagesLewthwaite EnvironmentalismDeterminismSearch 1966Henry Michael Rojas CornejoNo ratings yet

- Place As Historically Pred AllanDocument20 pagesPlace As Historically Pred AllanJhonny B MezaNo ratings yet

- SACK The Power of Place and SpaceDocument5 pagesSACK The Power of Place and SpaceJean BrumNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Geography: Perez, Angelica A. BS - Rem 3ADocument18 pagesThe Nature of Geography: Perez, Angelica A. BS - Rem 3AAngelica PerezNo ratings yet

- LEIDO Heise-LocalRockGlobal-2004Document28 pagesLEIDO Heise-LocalRockGlobal-2004Juan Camilo Lee PenagosNo ratings yet

- Cultural Geography The Busyness of Being More-Than-RepresentationalDocument13 pagesCultural Geography The Busyness of Being More-Than-RepresentationalDeyala TarawnehNo ratings yet

- Herzfeld-Spatial CleansingDocument23 pagesHerzfeld-Spatial CleansingsheyNo ratings yet

- Rapoport Culturallandscapes 1992Document16 pagesRapoport Culturallandscapes 1992Merry FaúndezNo ratings yet

- MUBI - On TerritorologyDocument21 pagesMUBI - On TerritorologyfjtoroNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 103.77.44.145 On Fri, 31 Jul 2020 08:05:47 UTCDocument15 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 103.77.44.145 On Fri, 31 Jul 2020 08:05:47 UTCDipsikha AcharyaNo ratings yet

- Church Man Disentangling Concept of DensityDocument24 pagesChurch Man Disentangling Concept of DensityyeseorikiNo ratings yet

- Michael Dear - The Postmodern Challenge: Reconstructing Human GeographyDocument14 pagesMichael Dear - The Postmodern Challenge: Reconstructing Human GeographyJoão VictorNo ratings yet

- APHG ReviewDocument108 pagesAPHG ReviewSuman PadhiNo ratings yet

- WILCOCK. EthnogeomorphologyDocument28 pagesWILCOCK. EthnogeomorphologyMarcos LeuNo ratings yet

- Harrison Et Al. - 2004 - Thinking Across The Divide Perspectives On The Conversations Between Physical and Human GeographyDocument8 pagesHarrison Et Al. - 2004 - Thinking Across The Divide Perspectives On The Conversations Between Physical and Human GeographyjenifaNo ratings yet

- A Space For Place in SociologyDocument35 pagesA Space For Place in Sociology12719789mNo ratings yet

- Goodchild 2008 ASSERTION AND AUTHORITY PDFDocument18 pagesGoodchild 2008 ASSERTION AND AUTHORITY PDFGustavo LuceroNo ratings yet

- Geography As The World Discipline Connecting Popul PDFDocument10 pagesGeography As The World Discipline Connecting Popul PDFRamesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Spatialities and Temporalities of The Global ElemeDocument19 pagesSpatialities and Temporalities of The Global ElemeCatarinaNo ratings yet

- Nature of GeographyDocument2 pagesNature of GeographyTariq UsmaniNo ratings yet

- Spatialities and Temporalities of The Global ElementsDocument19 pagesSpatialities and Temporalities of The Global ElementsETHAN YEO WEI CHENGNo ratings yet

- Geospatial Memory An Introduction PDFDocument31 pagesGeospatial Memory An Introduction PDFAna GuglielmucciNo ratings yet

- SHEPPARD - From Site To TerritoryDocument6 pagesSHEPPARD - From Site To TerritoryNikoloz TsagareishviliNo ratings yet

- Scale As Relation Musical Metaphors of Geographical ScaleDocument11 pagesScale As Relation Musical Metaphors of Geographical ScaleKaren TorresNo ratings yet

- Smith N - Gentrification and Uneven DevelopmentDocument18 pagesSmith N - Gentrification and Uneven DevelopmentnllanoNo ratings yet

- Certificate Physical and Human GeographyDocument21 pagesCertificate Physical and Human GeographysulemanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Archaeology and Spatial Analys PDFDocument17 pagesChapter 1 Archaeology and Spatial Analys PDFabdan syakurNo ratings yet

- The Regional Rootedness of Places: You Can Plan With That: Lineu Castello & Iára Regina CastelloDocument13 pagesThe Regional Rootedness of Places: You Can Plan With That: Lineu Castello & Iára Regina CastelloqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Warf 2000Document3 pagesWarf 2000Hesti PrawatiNo ratings yet

- Chapt16 PDFDocument33 pagesChapt16 PDFSandeep Kumar100% (1)

- 220 Landzelius Contested Representations Signification in The Built Environment PDFDocument24 pages220 Landzelius Contested Representations Signification in The Built Environment PDFJavier LuisNo ratings yet

- Moore 2017bDocument6 pagesMoore 2017bEurístides De la CruzNo ratings yet

- Aboriginal Territori OrganiozationDocument27 pagesAboriginal Territori OrganiozationasturgeaNo ratings yet

- BrattonDocument16 pagesBrattonkazumasaNo ratings yet

- Allen. 2011. Topological Twists Power's Shifting GeographiesDocument16 pagesAllen. 2011. Topological Twists Power's Shifting GeographiesGinés NavarroNo ratings yet

- ch02 PDFDocument10 pagesch02 PDFSamir FellousNo ratings yet

- Bradley J. Parker, Toward An Understanding of Borderland ProcessesDocument25 pagesBradley J. Parker, Toward An Understanding of Borderland ProcessesAnonymous hXQMt5No ratings yet

- Space and Spaciality in TheoryDocument21 pagesSpace and Spaciality in TheoryGuida RolNo ratings yet

- Rose 1994 Politics PlaceDocument16 pagesRose 1994 Politics PlacePaco CuetzNo ratings yet

- Marston HumanGeographywithout 2005Document18 pagesMarston HumanGeographywithout 2005Ambra Gatto BergamascoNo ratings yet

- Куба и ХаммонDocument27 pagesКуба и ХаммонАртём КотельниковNo ratings yet

- Delaney 93Document19 pagesDelaney 93Karla Flores PríncipeNo ratings yet

- Demeritt 2002Document25 pagesDemeritt 2002Janak TripathiNo ratings yet

- Design Anthropology PDFDocument1 pageDesign Anthropology PDFPatricia GallettiNo ratings yet

- Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating GazetteersFrom EverandPlacing Names: Enriching and Integrating GazetteersMerrick Lex BermanNo ratings yet

- Concept Note Asean Dengue Day 2019 Theme: "End Dengue: Starts With Me" Date: 15 June 2019 BackgroundDocument3 pagesConcept Note Asean Dengue Day 2019 Theme: "End Dengue: Starts With Me" Date: 15 June 2019 BackgroundJamalNo ratings yet

- Bocoran Metabolit Meningkat 1Document7 pagesBocoran Metabolit Meningkat 1nkustantoNo ratings yet

- Identification of Unknown White Compound FinalDocument5 pagesIdentification of Unknown White Compound FinalTimothy SilversNo ratings yet

- How Would You Characterize YourselfDocument2 pagesHow Would You Characterize YourselfCara Shelby Micah I. Magistrado95% (19)

- Accenture Data Scientist Interview QuestionsDocument13 pagesAccenture Data Scientist Interview QuestionsYogesh DosadNo ratings yet

- Victor Brochure VturnII-16 - 20 - 23 - 26 (20091230)Document16 pagesVictor Brochure VturnII-16 - 20 - 23 - 26 (20091230)atif jabbarNo ratings yet

- CV Julian PetrescuDocument2 pagesCV Julian PetrescuRazvan Julian Petrescu100% (1)

- DO 134 s2016 PDFDocument38 pagesDO 134 s2016 PDFBrian PaulNo ratings yet

- Project Report FormatDocument3 pagesProject Report FormatmaruthinmdcNo ratings yet

- Time ContactedDocument4 pagesTime ContactedDebashishDolonNo ratings yet

- Reciprocity Ring Solution Sheet 2020Document3 pagesReciprocity Ring Solution Sheet 2020Esphera Segurança do TrabalhoNo ratings yet

- 109 - Quiz 3Document21 pages109 - Quiz 3andreyorjuela jimenezNo ratings yet

- Forecast Time Series With R LanguageDocument98 pagesForecast Time Series With R Languageec04017No ratings yet

- Case Study On How AIS, FIS, KWS and OAS Are Being Used in An OrganisationDocument24 pagesCase Study On How AIS, FIS, KWS and OAS Are Being Used in An OrganisationKuldeep P ThakreNo ratings yet

- AI13-121 Update MTL HIMax MotherboardsDocument3 pagesAI13-121 Update MTL HIMax MotherboardsAndy Kong KingNo ratings yet

- NVIDIA Control Panel and System Monitor With ESA User GuideDocument45 pagesNVIDIA Control Panel and System Monitor With ESA User GuidePivaraNo ratings yet

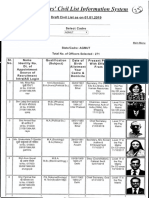

- IAS of Cers' Civil List Information SystemDocument28 pagesIAS of Cers' Civil List Information SystemMatthew HinesNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 8 Solution EmagnetDocument7 pagesTutorial 8 Solution Emagnethafiz azmanNo ratings yet

- Capstone Project PresentationDocument30 pagesCapstone Project PresentationRodel GodalleNo ratings yet

- Module-8 EQDocument16 pagesModule-8 EQJaggu JrzNo ratings yet

- Sama AjaxDocument17 pagesSama Ajaxernestohp7No ratings yet

- Legal PhilosophyDocument22 pagesLegal Philosophygentlejosh_316100% (2)

- Bio GeographyDocument12 pagesBio GeographyramchandakNo ratings yet

- Nari Gandhi 2016-17Document5 pagesNari Gandhi 2016-17John Anand KNo ratings yet

- Business Communication - Business LettersDocument36 pagesBusiness Communication - Business LettersAstro Ria100% (1)