Professional Documents

Culture Documents

M Marder Plant Attention

M Marder Plant Attention

Uploaded by

victor mella0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views5 pagesM.Marder.Plant.Attention

Original Title

M.Marder.Plant.Attention

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentM.Marder.Plant.Attention

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views5 pagesM Marder Plant Attention

M Marder Plant Attention

Uploaded by

victor mellaM.Marder.Plant.Attention

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 5

Autophagic Punctum

Plant Signaling & Behavior 8:5, e23902; May 2013; © 2013 Landes Bioscience

Plant intelligence and attention

Michael Marder

Department of Philosophy; The University of the Basque Country; UPV-EHU; Ikerbasque: Basque Foundation for Science; Vitoria-Gasteiz, Basque Country

T his article applies the phenomeno-

logical model of attention to plant

monitoring of environmental stimuli

Attention as Selectivity

Attention in general is not reducible

and signal perception. Three comple- to the mental concentration that usu-

mentary definitions of attention as ally distinguishes this attitude in human

selectivity, modulation and perdurance beings. Rather, a cross-species and cross-

are explained with reference to plant kingdoms definition of attention I propose

signaling and behaviors, including for- entails a disproportionate investment of

aging, ramet placement and abiotic physical or mental energy by an organism,

stress communication. Elements of ani- tissue, or cell into a particular activity or

mal and human attentive attitudes are into the reception of a singled-out stimu-

compared with plant attention at the lus or set of stimuli. Still falling short of a

levels of cognitive focus, context and non-anthropocentric theory of attention,

margin. It is argued that the concept of von Uexküll described how a relevant

attention holds the potential of becom- stimulus is noticed (gemerkt) by an animal

ing a cornerstone of plant intelligence subject, such that a portion of its envi-

studies. ronment is transformed into “perception

signs” (Merkzeichen).3 In the course of this

Introduction noticing, which stands for the most basic

stratum of attention (Aufmerksamkeit:

Studies of plant intelligence have tended sharing, in German, the grammatical root

to concentrate on memory as a bench- with “noticing”), the world is imbued with

mark of intelligent behavior.1,2 Although significance for the particular life-form in

memory has a bearing on all three question. Philosophically speaking, what-

modalities of time, including a remem- ever is so noticed corresponds to the non-

bered past event, the present of storage indifference of the cell or organism, whose

and the possibility of future retrieval, it survival often depends on registering the

is a marker of intelligence heavily biased perception signs appropriate to it and vital

toward the past. On the other hand, for its survival.

attention is a feature of intelligent con- For a vast majority of Western philoso-

duct in the present, whereby an organ- phers, plants are indifferent and insensate

ism selectively responds to ever-shifting beings.4,5 Vegetative intake of nutrients

stimuli in a way that allows it to maintain and exposure to sunlight are taken to be

Keywords: plant intelligence, adequate levels of adaptation to its envi- symbolic of a passive mode of living that

phenomenology, attention, selectivity, ronment. Before processing, evaluating does not pursue any objectives whatso-

intentionality, focus and communicating information, plants ever. Contrary to this bias, studies of plant

Submitted: 01/16/2013 must first attend to—or take note of— foraging behavior have revealed highly

the bits that are relevant to their optimal selective adaptational responses to patch-

Accepted: 02/06/2013

growth and development. Attention’s ily distributed subsoil resources. Clonal

Citation: Marder M. Plant intelligence and atten-

chronological precedence is matched in plants selectively allocate offspring ramets

tion; Plant Signal Behav 2013; 8: e23902;

http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/psb.23902 importance by its scope, insofar as atten- to the preferential patches of soil in the

Correspondence to: Michael Marder; tion accompanies all other components presence of multi-patch environmental

Email: michael.marder@gmail.com of intelligent conduct. heterogeneity.6 In environments with

www.landesbioscience.com Plant Signaling & Behavior e23902-1

homogeneous resource distribution, the that register blue and red/far-red light attentive focusing on varied events in its

presence of competition likewise solicited in the apical meristem’s chryptochromes environment.

a stronger root proliferation response and and phototropins, as well as in leaf phy-

“conferred a selective advantage to plants tochromes, respectively.15 Plant signaling Attention as Modulation

proliferating in the direction of the most consequently involves communication

recently acquired patch.” 7 Morphological from a focus of attention to other tis- Given the variability of environmental

plasticity in foraging behavior explains sues not directly affected by the stimu- circumstances, it is unreasonable to main-

the “different patterns of spacer pro- lus, or coordination among the multiple tain a constant focus on a single stimulus

duction and hence different patterns attentive foci, each of them singling out or group of stimuli. Attention implies as

in the placement of resource-acquiring a vital piece of information about envi- much fixity as movement or change9,11–13

structures.”8 ronmental conditions—often, by way of keeping the attentive organism attuned to

As these examples demonstrate, forag- parallel processing, as in the case of leaf the variations in its surroundings. In other

ing behaviors in plants are highly selec- photosensitivity. words, attention motivates a chain of

tive. They are accompanied by attention Attention individuates whatever falls focusing-defocusing-refocusing, in keep-

to numerous environmental factors, within its focus or foci by bringing the ing with the needs of the attentive subject

foremost among them resource availabil- stimulus into sharper relief against the at any given time, or, as in the case of non-

ity and the presence or absence of com- blurry background of the relatively sessile organisms, place. In the tripartite

petitors. Moreover, they help illustrate undifferentiated context, experienced as scheme of attention, these modulations are

the general phenomenological theory of “white noise.” For humans, this individu- expressed in the interchangeability of the

attention, usually restricted to human ation (or phenomenologically speaking, present focus and other, previously insig-

consciousness. According to this the- thematization) yields the objects of expe- nificant, points in the context wherein it

ory, the act of paying attention depends rience, along with the conscious directed- is situated.

upon three interrelated and dynamically ness (intentionality) toward these objects. Before the onset of abiotically-induced

structured elements: (1) focus or thema- Consciousness and its acts do not preexist stress, such as in drought conditions, plants

tization; (2) context; and (3) margins the attentive attitude but are co-orignary perceive cues emitted by their already-

or horizons.9–11 The first element (focus) with this attitude. Attentionality and damaged neighbors.2,17,21,22 In plant-plant

is a selective zeroing-in on a significant intentionality share the same functional communication, the foci of attention can

stimulus or set of stimuli. In the case and structural scope.9,20 therefore overlap, even if the contexts

of foraging, a stimulus plants focus on While it plays the role of putting into from which they stand out are different,

is the quality of the soil, which must focus and thereby singularizing crucial namely actual drought conditions in the

be assessed as a precondition for select- environmental inputs, the attention of one case and proximity to a stressed plant

ing a resource-rich patch. But, in order plants is objectless. Their unique sight in the other. Due to an identical focus, the

to attend to an appropriate stimulus, does not translate visual stimuli into pic- response to a communicated cue will also

the attentive subject must first single it tures but into instructions for growth or be the same as to the onset of drought.

out from a general field, or context, that reproduction.15 Plant attention is likewise Since plant attention is active, rather

surrounds it. If the stimulus is not sig- active, rather than contemplative, as it than merely contemplative, its stress-

nificant for the subject, it will remain feeds directly into the plants’ phenotypic related modulation results in behavioral

dissolved in the context, which ought plasticity and capacity for adaptation. To changes that often entail the activation

to be understood as the background individuate the foci of attention, it is not of stress-inducible genes—rd (responsive

“white noise.” Growth in homogeneous necessary to transform them into objects, to dehydration), erd (early responsive to

environments in the absence of competi- that is to say, forms that are cruder still dehydration), cor (cold regulated) and

tion resulted in a random rooting of the than the discernments and discrimina- kin (cold-inducible) in Arabidopsis—and

ramets of Leymus chinensis and Hierochloe tions of which plants are capable. Not subsequently, an extensive transcriptional

glabra.6 Under these conditions, neither only do plants distinguish between reprograming.23

of the species focused on any given patch mechanical and herbivore-induced dam- In accordance with their evolutionary

of the soil. While information about age but they also respond by releasing rationale, acts of attention put the attentive

resource density is still potentially useful, appropriate airborne volatiles or commu- organism on its guard, emphasizing with

it is relegated to the context of attention nicate through belowground stress cues, greater intensity some stimuli over others.

and is not brought into the focus of the indexed to the specific stress factor.16–19 External dangers and threats vary for dif-

attending organism. The more dire a threat, the more does ferent species and kingdoms, and so does

While a single-minded or unifocal the need arise for an attentive singling the attentive comportment that responds,

attentive comportment is said to absorb out of its source with the view to its miti- at times preemptively, to these. Although

the attentive subject, involuntary atten- gation or to altering a relevant facet of in Husserl’s phenomenology attentional

tion is dispersed throughout the sentient plant morphology and physiology so as to changes are taken to be signs of freedom—

body.12–14 Multifocal attention is simi- reduce the impact of the stressor.20 Plant “the free turning of the regard”9 —they

larly characteristic of the green plants behavior is a cumulative outcome of its in fact are determined by changes in the

e23902-2 Plant Signaling & Behavior Volume 8 Issue 5

environmental conditions of an attentive stimulus. In plants, mobility belongs in focus of attention, except that a single focal

organism. To be sure, phenomenological the domain of signaling and cell-to-cell point, with its limited action potential, is

freedom does not entail arbitrariness: the communication—the mobile hormonal insufficient as an investment of energy

attentive attitude is “wandering in a deter- signals that play an important role in the into the act of trap closure. A twenty-sec-

minate manner,”9 determined, that is, by control of shoot branching24 and plant ond delay between the respective stimula-

the temporal and spatial fluctuations in action potentials, resulting, for instance, tions of two sensory hairs allows for the

the subject’s life-world. In plants, these in a rapid transmission of oxidative and accumulation of an action potential strong

modulations are predominantly tempo- nitrosative stress signals between root and enough to shut the trap.3,15,32 In the pres-

ral, though the frontiers of growth do not shoot apices of Arabidopsis.26,28 As reac- ent moment of the second stimulation,

preclude a spatial “wandering,” which we tion times (and hence quick shifts from attention builds upon the short-term elec-

will explore in a subsequent section of the one focus within the context of attention trical memory of the first stimulation to

present study. to another) make a difference for the sur- complete the investment of energy with

The open-ended morphology of a plant vival of an organism, the relative speed of a Ca 2+ influx at a threshold where it can

objectively expresses its acts of attention intercellular communication in plants is attain its intended foraging goal.15,33 The

over time, as its body plan is adjusted to crucial for their inclusion among atten- continuum of intelligence thus extends

environmental conditions, for instance tive subjects. If plants are “fast biosensors from the retention of short-term electri-

through the hormonal control of shoot for molecular recognition of the direction cal memory, through the monitoring of

branching.24 The decision on activating of light, monitoring the environment and further developments within the focus of

a particular axillary meristem is taken at detecting insect attacks,”27,30 then their attention, to the anticipation of prey—the

the intersection of local information pro- attentional modulations are on the par intended target of this deliberate behavior.

cessing and a global network of hormonal with sudden changes in environmental Only as a temporally coherent ensemble

signaling, attuned at the same time to the conditions that make up the concrete con- do the three behavioral modalities add up

external environmental factors and the text of their growth and development. to purpose-driven, intelligent conduct.

plant’s internal physiological and devel- What the example of Dionaea so clearly

opmental needs.24 The interplay between Attention as Perdurance conveys is that the practical success or fail-

these various levels of attention in plants is ure of attention does not depend on atten-

thus no less complex than in animals and Attention cannot be entirely isolated tion alone. The duration of attention is

humans, who permanently shift between from other characteristics of intelligent due to the memory, on which it draws in

attention to an external object and to their and deliberate behavior, and especially the temporal continuum extending toward

internal (mental and physical) states. from memory and anticipation. Following the future attainment of a goal. This is so

The rudimentary freedom of attention the insights of the phenomenology of time not only in the “sensitive” plants, Dionaea

is palpable in the reversibility of behaviors consciousness, experience is a continuum muscipula or Mimosa pudica, but also in

attributed to attentional modulations. of retention, attention and protention, every plant species that relies on monitor-

Along these lines, “foraging responses irradiating from the present back into the ing circadian rhythms to make decisions

are reversible over the long run” and, in organism’s past and future.29 The inclu- on the most appropriate flowering time.34–

some species such as H. glabara, can be sion of attention in this uninterrupted 36

The decreasing red to far-red (R:FR)

reversed very quickly, in tune with the chain testifies to its dialectical nature, light ratios that are responsible for the

fluctuations in environmental heteroge- combining the opposites of fixity and bud burst in Betula pendula37,38 evidence

neity.6 The modular architecture of roots movement, freedom and determinateness, a complex interaction of plant memory

and branches, seeking optimal growth, rapid reaction and lingering with whatever and attention, where the calculation of the

spatially reflects the modulations in the one attends to. ratios, as well as their storage and retrieval,

plants’ attention.7 The interactions among The starkest illustration of the idea are mediated by attention to the last far-

at least 15 environmental factors, to which that there are no acts of attention with- red and the first red lights of each photo-

this attention can turn, and the enormous out memory and anticipation is the Venus period. Attention as perdurance refers to

range of responses their combinations are flytrap, or Dionaea muscipula. If attention this interaction, oriented toward a future

responsible for25 further contribute to the betokens a disproportionate and fluctuat- goal (germination, flowering, etc.).

freedom of attention-laden behavior in ing investment of energy into vital areas of

plants. In phenomenological terms, these activity, then the Venus flytrap is the case- Attention at the Margin

factors and their interactions delineate the in-point of attention to its prey, in that

context of attention, within which foci “closing its trap requires a huge expense The last element in the tripartite phenom-

may shift (or wander) in a determinate of energy.”2,15,31 Described in phenom- enological model of attention, the mar-

manner. enological terms, the context of Dionaea’s gin outlines the limits of the context and

In animals and humans, the turning of attention includes everything around the determines the horizons of the field, within

attention signifies, in the first instance, the sensory hairs that detect the presence or which acts of attention unfold. The mar-

mobility of relevant body parts and sense absence of an insect on the plant’s lobes. gins of animal and human attention shift

organs, directed toward the newly salient The insect itself would be situated at the along with the mobile attentive subject

www.landesbioscience.com Plant Signaling & Behavior e23902-3

14. Merleau-Ponty M. Phenomenology of perception.

itself, whose dislocation to different parts While animal communication displays London & New York: Routledge 2002

of its environment defines the horizons of “eye-catching” movements, plant commu- 15. Chamovitz D. What a plant knows: a field guide to

the senses. New York: Scientific American / Farrar,

its experience. The margins of attention nication transpires mostly “out of sight,”46 Staus & Giroux 2012

of a sessile organism—whether a sessile in the release of volatile airborne sub- 16. Heil M, Ibarra-Laclette E, Adame-Álvarez RM,

animal or a plant—vary predominantly stances, in the transition zone of the root Martínez O, Ramirez-Chávez E, Molina-Torres J, et

al. How plants sense wounds: damaged-self recogni-

along the temporal axis, and this variation apex,47 and so forth. Despite these funda- tion is based on plant-derived elicitors and induces

is a behavioral feature that responds to mental differences, plant attention eluci- octadecanoid signaling. PLoS ONE 2012; 7:e30537;

PMID:22347382; http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/jour-

the changing needs of the organism, from dates the general functioning of attentive nal.pone.0030537

foraging to reproduction and defense. comportment in a dialectical combination 17. Falik O, Mordoch Y, Ben-Natan D, Vanunu M,

Indeed, the definition of plant behavior as of fixity and modulation. It sheds light on Goldstein O, Novoplansky A. Plant responsiveness

to root-root communication of stress cues. Ann Bot

“a response to an event or environmental the intimate relation between intentional- 2012; 110:271-80; PMID:22408186; http://dx.doi.

change during the course of the lifetime ity and the sphere of attention, as well as org/10.1093/aob/mcs045

of an individual”38–40 largely overlaps both between attention and memory put in the 18. Turlings TC, Loughrin JH, McCall PJ, Röse US,

Lewis WJ, Tumlinson JH. How caterpillar-dam-

with the temporal variations in the mar- service of goal-oriented behavior. Finally, aged plants protect themselves by attracting para-

gins of attention and with phenotypic it substantiates the tripartite model devel- sitic wasps. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995; 92:4169-

74; PMID:7753779; http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/

plasticity. oped by phenomenologists and confirms pnas.92.10.4169

Besides temporal shifts, the margins of its applicability to non-human, as well as 19. Paré PW, Tumlinson JH. Plant volatiles as a

plant attention also change in space. Leaf non-animal, life forms. defense against insect herbivores. Plant Physiol

1999; 121:325-32; PMID:10517823; http://dx.doi.

expansion and contraction, spacer length- org/10.1104/pp.121.2.325

ening and shortening, branching and Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest 20. Marder M. Plant intentionality and the phenomeno-

ramet production (among other aspects No potential conflicts of interest were logical framework of plant intelligence. Plant Signal

Behav 2012; 7:1365-72; PMID:22951403; http://

of plant growth) translate into variations disclosed. dx.doi.org/10.4161/psb.21954

in the spatial horizons of attention. Leaf 21. Falik O, Mordoch Y, Quansah L, Fait A, Novoplansky

expansion that increases the surface of References A. Rumor has it...: relay communication of stress

cues in plants. PLoS ONE 2011; 6:e23625;

these “iterated green antennae specialized 1. Karpiński S, Szechyńska-Hebda M. Secret life of

PMID:22073135; http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/jour-

plants: from memory to intelligence. Plant Signal

for trapping light energy, absorbing carbon Behav 2010; 5:1391-4; PMID:21051941; http://

nal.pone.0023625

22. Blum A. Plant breeding for water-limited environ-

dioxide, transpiring waterand monitoring dx.doi.org/10.4161/psb.5.11.13243

ments. New York: Springer 2010

2. Cvrcková F, Lipavská H, Zárský V. Plant intel-

the environment;”41 spacer lengthening in ligence: why, why not or where? Plant Signal Behav 23. Akpinar BA, Avsar B, Lucas SJ, Budak H. Plant abi-

resource-poor soils; 42 and the plasticity of 2009; 4:394-9; PMID:19816094; http://dx.doi. otic stress signaling. Plant Signal Behav 2012; 7:1450-

org/10.4161/psb.4.5.8276 5; PMID:22990453; http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/

shoot branching, regulated by networks psb.21894

3. von Uexküll J. A foray into the worlds of animals

of hormonal signals43 extend the context and humans. Minneapolis & London: University of 24. Leyser O. The control of shoot branching: an example

of plant information processing. Plant Cell Environ

of plant attention within its growing mar- Minneapolis Press 2010

2009; 32:694-703; PMID:19143993; http://dx.doi.

gins. In turn, the maximization of surface 4. McGinnis J. Avicenna. Oxford: Oxford University

org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01930.x

Press 2010

exposure facilitating a greater capture of 5. Hegel GWF. Hegel’s philosophy of nature: encyclo-

25. Trewavas A. Aspects of plant intelligence. Ann

Bot 2003; 92:1-20; PMID:12740212; http://dx.doi.

energy44 introduces more possible focal paedia of the philosophical sciences (1830). Oxford:

org/10.1093/aob/mcg101

Oxford University Press 2004

points into the expanding sphere of atten- 26. Baluška F, Volkmann D, Menzel D. Plant synapses:

6. Gao Y, Xing F, Jin Y, Nie D, Wang Y. Foraging

tion. Thus, while the margins of animal responses of clonal plants to multi-patch environ-

actin-based domains for cell-to-cell communication.

Trends Plant Sci 2005; 10:106-11; PMID:15749467;

and human attention follow the shifting mental heterogeneity: spatial preference and temporal

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2005.01.002

reversibility. Plant and Soil 2012; 359:137-47; http://

horizons of these self-dislocating subjects, dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1148-0 27. Volkov AG, Ranatunga DRA. Plants as environ-

the margins of plant attention irradiate mental biosensors. Plant Signal Behav 2006; 1:105-

7. Croft SA, Hodge A, Pitchford J. Optimal root pro-

15; PMID:19521490; http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/

outward, both vertically and laterally, liferation strategies: the roles of nutrient heterogene-

psb.1.3.3000

ity, competition and mycorrhizal networks. Plant

encompassing new areas adjacent to their Soil 2012; 351:191-206; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/ 28. Fromm J, Lautner S. Electrical signals and their phys-

iological significance in plants. Plant Cell Environ

immediate environment. s11104-011-0943-3

2007; 30:249-57; PMID:17263772; http://dx.doi.

8. Hutchings MJ, de Kroon H. Foraging in plants: the

org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01614.x

role of morphological plasticity in resource acquisi-

Conclusions tion. Adv Ecol Res 1994; 25:159-238; http://dx.doi. 29. Husserl E. On the phenomenology of the conscious-

org/10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60215-9 ness of internal time (1893-1917). Dodrecht: Kluwer

1991

9. Husserl E. Ideas pertaining to a pure phenomenology

Phenomenology of attention enriches and to a phenomenological philosophy, first book. 30. Wayne R. The excitability of plant cells: with a spe-

the theoretical understanding of ways in Dordrecht: Kluwer 1983 cial emphasis on characean internodal cells. Bot Rev

1994; 60:265-367; PMID:11539934; http://dx.doi.

which plants perceive signals and monitor 10. Gurwitch A. Studies in phenomenology and psychol-

org/10.1007/BF02960261

ogy. Evanston: Northwestern University Press 1966

light, temperature and gravity gradients in 11. Arvidson PS. The sphere of attention: context and

31. Volkov AG, Adesina T, Markin VS, Jovanov E.

Kinetics and mechanism of Dionaea muscipula

their physical environments.45 The chal- margin. Dordrecht: Springer 2006)

trap closing. Plant Physiol 2007; 146:694-702;

lenge specific to the study of plant atten- 12. Marder M. What is living and what is dead in atten- PMID:18065564 ; http://dx.doi.org/10.1104/

tion? Research in Phenomenology 2009; 39:29-51;

tion is that frequently what plants attend http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156916408X389622

pp.107.108241

to does not coincide with the targets of 13. Marder M. Phenomenology of distraction, or

human attention. attention in the fissuring of time and space. Res

Phenomenol 2011; 396-419

e23902-4 Plant Signaling & Behavior Volume 8 Issue 5

32. Markin VS, Volkov AG, Jovanov E. Active move- 38. Karban R. Plant behaviour and communication. 44. Hallé F. In praise of plants. Cambridge: Timber Press

ments in plants: Mechanism of trap closure by Ecol Lett 2008; 11:727-39; PMID:18400016; http:// 2002

Dionaea muscipula Ellis. Plant Signal Behav dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01183.x 45. Baluška F, Mancuso S. Plant neurobiology: from

2008; 3:778-83; PMID:19513230; http://dx.doi. 39. Silvertown J, Gordon DM. A framework for plant sensory biology, via plant communication, to social

org/10.4161/psb.3.10.6041 behavior. Annual Review Ecology and Systematics plant behavior. Cogn Process 2009; 10(Suppl 1):3-7;

33. Hodick D, Sievers A. The action potential of Dionaea 1989; 20:349-66 ; http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/ PMID:18998182; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10339-

muscipula Ellis. Planta 1988; 174:8-18; http:// annurev.es.20.110189.002025 008-0239-6

dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00394867 40. Silvertown J. Plant phenotypic plasticity and non- 46. Gagliano M, Renton M, Duvdevani N, Timmins M,

34. Robertson McClung C. Circadian Rhythms in cognitive behaviour. Trends Ecol Evol 1998; 13:255- Mancuso S. Out of sight but not out of mind: alterna-

Plants. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant 6; PMID:21238291; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ tive means of communication in plants. PLoS ONE

Molecular Biology 2001; 52:139-62; http://dx.doi. S0169-5347(98)01398-6 2012; 7:e37382; PMID:22629387; http://dx.doi.

org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.139 41. Van Volkenburgh E. Leaf expansion – an integrating org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037382

35. Cashmore AR. Cryptochromes: enabling plants and plant behavior. Plant Cell Environ 1999; 22:1463-73; 47. Baluška F, Mancuso S. Plant neurobiology: From

animals to determine circadian time. Cell 2003; http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.1999.00514.x stimulus perception to adaptive behavior of plants,

114:537-43; PMID:13678578; http://dx.doi. 42. Oborny B. Spacer length in clonal plants and the via integrated chemical and electrical signaling.

org/10.1016/j.cell.2003.08.004 efficiency of resource capture in heterogeneous Plant Signal Behav 2009; 4:475-6; PMID:19816121;

36. Suárez-López P, Wheatley K, Robson F, Onouchi environments: A Monte Carlo simulation. Folia http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/psb.4.6.8870

H, Valverde F, Coupland G. CONSTANS medi- Geobot 1994; 29:139-58; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/

ates between the circadian clock and the con- BF02803791

trol of flowering in Arabidopsis. Nature 2001; 43. Domagalska MA, Leyser O. Signal integration in the

410:1116-20; PMID:11323677; http://dx.doi. control of shoot branching. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol

org/10.1038/35074138 2011; 12:211-21; PMID:21427763; http://dx.doi.

37. Linkosalo T, Lechowicz MJ. Twilight far-red org/10.1038/nrm3088

treatment advances leaf bud burst of silver birch

(Betula pendula). Tree Physiol 2006; 26:1249-56;

PMID:16815827; http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/tree-

phys/26.10.1249

www.landesbioscience.com Plant Signaling & Behavior e23902-5

You might also like

- Lenovo ThinkPad T480 01YR328 NM B501Document104 pagesLenovo ThinkPad T480 01YR328 NM B501rishi vaghelaNo ratings yet

- Misinterpretation of TasawwufDocument260 pagesMisinterpretation of TasawwufSpirituality Should Be LivedNo ratings yet

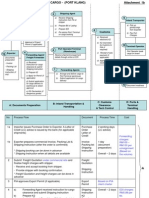

- Export + Import Process Flow - Break Bulk Cargo 27072010Document11 pagesExport + Import Process Flow - Break Bulk Cargo 27072010Ahmad Fauzi Mehat100% (1)

- References ASEAN2Document3 pagesReferences ASEAN2M IrwaniNo ratings yet

- DHIS Monthly Reporting Form (PHC Facilities)Document4 pagesDHIS Monthly Reporting Form (PHC Facilities)Usman89% (9)

- Extended Cognition in PlantsDocument6 pagesExtended Cognition in PlantsAlan Rodrigo Montes de Oca GonzálezNo ratings yet

- WhiskingDocument4 pagesWhiskingGabriel HerreraNo ratings yet

- Calvo Et Al - 2020 - Plants Are Intelligent, Here's How - Annals of BotanyDocument18 pagesCalvo Et Al - 2020 - Plants Are Intelligent, Here's How - Annals of BotanyCecilia NunezNo ratings yet

- Foraging CogntionDocument12 pagesForaging CogntionSamaksh ModiNo ratings yet

- The Neural Pathways Development and Functions ofDocument6 pagesThe Neural Pathways Development and Functions ofThatPotato FTWNo ratings yet

- Plants Neither Possess Nor Require ConsciousnessDocument11 pagesPlants Neither Possess Nor Require ConsciousnessAnonymous CatNo ratings yet

- Context-Dependent Control of Behavior in Drosophila PDFDocument9 pagesContext-Dependent Control of Behavior in Drosophila PDFMert GencNo ratings yet

- Plant Intelligence: An Alternative Point of ViewDocument7 pagesPlant Intelligence: An Alternative Point of ViewvalentinaaguilarNo ratings yet

- Taiz Et Al., TPS, 2019Document11 pagesTaiz Et Al., TPS, 2019Amanda AlbaNo ratings yet

- Baluska - Plant - NeurobiologyDocument7 pagesBaluska - Plant - NeurobiologyVictorGuimarães-MariussoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0959438818300813 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0959438818300813 MainLilianne Mbengani LaranjeiraNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Appetitive and Defensive Motivation: Goal-Directed or Goal-Determined?Document7 pagesNIH Public Access: Appetitive and Defensive Motivation: Goal-Directed or Goal-Determined?Fotocopiadora JesúsNo ratings yet

- BIOLOGYDocument2 pagesBIOLOGYrcly warioNo ratings yet

- Amygdala: Eyes Wide Open: Current Biology Vol 24 No 20 R1000Document3 pagesAmygdala: Eyes Wide Open: Current Biology Vol 24 No 20 R1000Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Neurocognitive Mechanisms of Anxiety: An Integrative AccountDocument10 pagesNeurocognitive Mechanisms of Anxiety: An Integrative AccountMarianaNo ratings yet

- A Functional Neuro-Anatomical Model of Human Attachment (NAMA) : Insights From First-And Second-Person Social NeuroscienceDocument41 pagesA Functional Neuro-Anatomical Model of Human Attachment (NAMA) : Insights From First-And Second-Person Social NeuroscienceSandra GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Calvo - Are Plants CognitiveDocument8 pagesCalvo - Are Plants CognitiveVictorGuimarães-MariussoNo ratings yet

- M Marder Ethical EatingDocument9 pagesM Marder Ethical EatingaxiomatizadorrNo ratings yet

- Functions of Interoception From EnergyDocument10 pagesFunctions of Interoception From EnergyMirnaFloresNo ratings yet

- Metacognition in Multisensory PerceptionDocument12 pagesMetacognition in Multisensory Perceptioncuentafalsa123No ratings yet

- Cognição em PlantasDocument16 pagesCognição em PlantasMaria MorrisNo ratings yet

- Sistema Atencional de Reorientacion de La AtencionDocument35 pagesSistema Atencional de Reorientacion de La AtencionAlexandraNo ratings yet

- Principles of Minimal Cognition: Casting Cognition As Sensorimotor CoordinationDocument14 pagesPrinciples of Minimal Cognition: Casting Cognition As Sensorimotor CoordinationKeeri Nicolas Romero VargasNo ratings yet

- Attention and Consciousness Two Distinct Brain ProDocument8 pagesAttention and Consciousness Two Distinct Brain Prohllo2306No ratings yet

- 978 1 4419 1428 6 - 530 PDFDocument72 pages978 1 4419 1428 6 - 530 PDFCaro ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Social Cognition and The Human Brain: Ralph AdolphsDocument11 pagesSocial Cognition and The Human Brain: Ralph AdolphsAnyella CastilloNo ratings yet

- Assignment-4: Course Code: BM-515Document2 pagesAssignment-4: Course Code: BM-515Kaustav DeNo ratings yet

- Daniel Hutto - REC. Revolution Effected by ClarificationDocument15 pagesDaniel Hutto - REC. Revolution Effected by ClarificationChristian SanchezNo ratings yet

- A General Theory of Consciousness I Consciousness and Adaptation 2020Document17 pagesA General Theory of Consciousness I Consciousness and Adaptation 2020olivukovicNo ratings yet

- Face Ur Fears-Silva - Graff-2023-TICSDocument13 pagesFace Ur Fears-Silva - Graff-2023-TICSWinter Koidun FalgunNo ratings yet

- Sistema Inmunológico-El Séptimo SentidoDocument2 pagesSistema Inmunológico-El Séptimo SentidoMARIA FLAVIA MACEDO PÉREZNo ratings yet

- Treue 2009Document8 pagesTreue 2009Victor Flores BenitesNo ratings yet

- Plants People Planet - 2022 - Stagg - Plant Awareness Is Linked To Plant Relevance A Review of Educational andDocument14 pagesPlants People Planet - 2022 - Stagg - Plant Awareness Is Linked To Plant Relevance A Review of Educational andJessica LeãoNo ratings yet

- 00 Genetic Influences On Social CognitionDocument7 pages00 Genetic Influences On Social CognitionZeljko LekovicNo ratings yet

- Environmental Influence in The Brain, Human Welfare and Mental HealthDocument11 pagesEnvironmental Influence in The Brain, Human Welfare and Mental HealthericjimenezNo ratings yet

- Attention and Its Disorders: Darren R GitelmanDocument14 pagesAttention and Its Disorders: Darren R GitelmanPragnyaNidugondaNo ratings yet

- Naturalizing Consciousness A Theoretical Framework Edelman PNAS 2003Document5 pagesNaturalizing Consciousness A Theoretical Framework Edelman PNAS 2003hamletquiron100% (1)

- O M W, A, B N, M: Review ArticleDocument6 pagesO M W, A, B N, M: Review ArticleGustavo Anguita ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Dayan 2000Document6 pagesDayan 2000Aiden SevNo ratings yet

- 18 5 SteinmanDocument6 pages18 5 SteinmanPierre A. RodulfoNo ratings yet

- Empathy As A Driver of Prosocial Behaviour: Highly Conserved Neurobehavioural Mechanisms Across SpeciesDocument11 pagesEmpathy As A Driver of Prosocial Behaviour: Highly Conserved Neurobehavioural Mechanisms Across SpeciesMira MiereNo ratings yet

- Pessoa2010 Emotion Processing and The AmydgalaDocument10 pagesPessoa2010 Emotion Processing and The AmydgalaMaria CordeiroNo ratings yet

- Barsalou TICS 2005 Continuity Across SpeciesDocument3 pagesBarsalou TICS 2005 Continuity Across SpeciesMica Ballito de TroyaNo ratings yet

- Phenotypic Plasticity For Plant Development Function and Life HistoryDocument6 pagesPhenotypic Plasticity For Plant Development Function and Life Historyshazeen shoaibNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0149763421005157 MainDocument14 pages1 s2.0 S0149763421005157 MainsamuelglstorageNo ratings yet

- Rational Inattention in MiceDocument34 pagesRational Inattention in MicelunaNo ratings yet

- Attention and Its DisordersDocument15 pagesAttention and Its DisordersMarija PetrovicNo ratings yet

- XI BiologyDocument18 pagesXI Biology16p3041No ratings yet

- Decety Et Al 2015Document11 pagesDecety Et Al 2015AlexMouraNo ratings yet

- The Somatic Marker Hypothesis and The Possible Functions of The Prefrontal CortexDocument9 pagesThe Somatic Marker Hypothesis and The Possible Functions of The Prefrontal CortexMauricio Vega MontoyaNo ratings yet

- 20211110-Swecog-Cognition As A Result of Information Processing in Living Agent's MorphologyDocument32 pages20211110-Swecog-Cognition As A Result of Information Processing in Living Agent's MorphologyGordana Dodig-CrnkovicNo ratings yet

- Mental Perspective of The SelfDocument2 pagesMental Perspective of The SelfLovely May JardinNo ratings yet

- 2018 - The Gut Microbiome As A Driver of Individual Variation in Cognition and FunctionalDocument13 pages2018 - The Gut Microbiome As A Driver of Individual Variation in Cognition and FunctionalcortizmenNo ratings yet

- IC Human Behavior and VictimologyDocument9 pagesIC Human Behavior and VictimologyjazatairNo ratings yet

- Animal CommunicationDocument15 pagesAnimal CommunicationEloyNo ratings yet

- PD 005 0479a PDFDocument15 pagesPD 005 0479a PDFKeren MalchiNo ratings yet

- Dewaal 2017Document12 pagesDewaal 2017Maria CoelhoNo ratings yet

- Harlow59 PDFDocument12 pagesHarlow59 PDFJuan Carcausto100% (1)

- The Instinct of Workmanship and the State of the Industrial ArtsFrom EverandThe Instinct of Workmanship and the State of the Industrial ArtsNo ratings yet

- Anchored: How to Befriend Your Nervous System Using Polyvagal TheoryFrom EverandAnchored: How to Befriend Your Nervous System Using Polyvagal TheoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- Prenatal Diagnosis of Brainstem AnomaliesDocument34 pagesPrenatal Diagnosis of Brainstem AnomaliesVishnu priya kokkulaNo ratings yet

- HyperlipidemiaDocument29 pagesHyperlipidemiagowthamNo ratings yet

- MUSIC Quarter 3Document13 pagesMUSIC Quarter 3RaeNo ratings yet

- 31 Calculus II (MDS)Document45 pages31 Calculus II (MDS)Srinivas VamsiNo ratings yet

- Lightnng Protection As Per IEC 62305Document40 pagesLightnng Protection As Per IEC 62305Mahesh Chandra Manav100% (1)

- 20 Types of Pasta - TLE9Document2 pages20 Types of Pasta - TLE9Chloe RaniaNo ratings yet

- The Secrets of Ancient Rome's Buildings - History - Smithsonian Magazine PDFDocument2 pagesThe Secrets of Ancient Rome's Buildings - History - Smithsonian Magazine PDFMarlui Faith MaglambayanNo ratings yet

- Circut Diagram For GlucometerDocument22 pagesCircut Diagram For GlucometerSaranyaNo ratings yet

- EEE40003 Digital Signal and Image Processing: LAB 3: Discrete LTI SystemsDocument13 pagesEEE40003 Digital Signal and Image Processing: LAB 3: Discrete LTI SystemsKai JieNo ratings yet

- Objections Upon The Views of Ibn QudamaDocument4 pagesObjections Upon The Views of Ibn QudamaAHLUSSUNNAH WAL JAMAA"AH [ASHA:'IRAH & MATURIDIYAH]No ratings yet

- YantraDocument57 pagesYantraKristina BabicNo ratings yet

- Hotpoint Washing Machine Wmf740Document16 pagesHotpoint Washing Machine Wmf740furheavensakeNo ratings yet

- TAS Product Catalog 2020 01Document210 pagesTAS Product Catalog 2020 01ct0720054858No ratings yet

- 6 Biomechanical Basis of Extraction Space Closure - Pocket DentistryDocument5 pages6 Biomechanical Basis of Extraction Space Closure - Pocket DentistryParameswaran ManiNo ratings yet

- XV NATCOSEB First CircularDocument2 pagesXV NATCOSEB First CircularMn HbkNo ratings yet

- 1.8 Anchor Systems Indd 2009Document80 pages1.8 Anchor Systems Indd 2009ihpeter100% (1)

- The Bird CageDocument1 pageThe Bird CageNick BlueNo ratings yet

- Singer 291U1, U3Document46 pagesSinger 291U1, U3Datum VivelacriqueNo ratings yet

- Drugs For Chemical EngineeringDocument34 pagesDrugs For Chemical Engineeringshivakumar hrNo ratings yet

- Clean and GreenDocument9 pagesClean and GreenDanny Dancel100% (1)

- Total Width of The ACP PanelDocument8 pagesTotal Width of The ACP PanelARYA100% (1)

- Electromagnetic WavesDocument173 pagesElectromagnetic WavesatiqdhepNo ratings yet

- Selwood EngineDocument5 pagesSelwood EngineramjoceNo ratings yet

- Question Bank Final Year BDSDocument19 pagesQuestion Bank Final Year BDSPoonam K JayaprakashNo ratings yet

- Soal OkeDocument12 pagesSoal OkefredyNo ratings yet