Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gotra 03

Gotra 03

Uploaded by

harsh garg0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

56 views17 pagesOriginal Title

Gotra.03

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

56 views17 pagesGotra 03

Gotra 03

Uploaded by

harsh gargCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 17

EK Te KINSHIP ORGANIZATION IN INDIA

“The study presents a few interesting poi

x Marriage rules ete., as revealed in 27 Jat fai

marriages

‘There was no marriage within the village. In al

were brought from outside the village and the

outside the village.

In this village 208 separate named villages are involved in the.

225 marriage transactions. If a girl was given or taken from a)

village other than their own, the expected number of separate

named villages would have been 225, but it is not so. Therefore

have to account for 17 marriages to make up the total of

noticed that in 9 cases two brides were brought.

‘the case of 5 families two

daughters were given in the same village; lastly in one family q

girl has been given in a village from which a bride was taken.

Though it seems that generally one daughter is given or taken

‘as a bride from a particular village, there is no taboo ai

or taking more than one bride from a single

regarding the

lies in which 225

CHAPTER IV

1e cases brides

Is were given

THE KINSHIP ORGANIZATION OF THE CENTRAL ZONE

L fhe central zone comprises the f¢ iguistic regi

“ 1e fol ic regions: (1)

Rajasthan where Rajasthani 2) Madhya Pradesh where

spoken, (3) Gujarat and Kathiawad where Gujarati and

athiawadi are spoken, (4) Maharashtra where Marathi is spoken

and (5) Orissa where Uriya is spoken.

whereas in 5 other cases two daughters were given in the same.

village.

It appears that the brides are given to

are generally different from the set of

girls are taken. However, there is one family

tion to this rule. In eight other villages a daughter was given

y whereas a bride was brought from the same v

KINSHIP ORGANIZATION OF THE CENTRAL ZONE. 165

ppich is the same as the marriage of a girl to her father’s sister's.

ps. In some regions this marriage Ts practised by only a few

2 in one preferred by the majority

este. "he and featne in the kinship organization of this

that many of the castes are divided into exogamous clans.

is that among some castes the exogamous clans are arran-

a hypergamous hierarchy, i.e, a girl in a lower clan can

harry @ man of a higher clan but a girl in a higher clan may not

parry a man ina lower clan. Of these three features, we have

een the existence of hypergamy in some of the castes in the

jorthern zone but there is reason to believe that the northern

imitation of the system followed by the Rajputs

‘northern India as conquerors from the 6th

164 KINSHIP ORGANIZATION IN INDIA

languages of the Dravidian family and also some areas whe

Austro-Asiatie languages are spoken.

Every one of the above regions contains

stages of assimil

the zone. There are som

Maharashtra who are A

dependent hunters while there are others like Bhils who are

different agriculturists and Kolams and Warlis who are skilled rig

growers. ‘The map above gives the names and locations of 4

various primitive tribes. How much of the present population

this zone is made up of these tribes we need not discuss in tig

present context but there is no doubt that that element must h;

been of great influence towards shaping the kinship pattern of th

None of the features enumerated above are found all over the

zone, nor all over a single region within the zone. ‘There is how-

r one region, i.e, Maharashtra which has the three features more

widely spread than all the other regions. ‘The kinship termino-

logy of Maharashtra though mainly Sanskritic in origin uses con-

cepts which are not found among other regions where Sanskritic

Hanguages are spoken and which can be understood only by a re-

ference to the kinship organization and kinship terms used in the

outhern zone.

Because of the wide variation of behaviour in the regions, they

are treated separately in this chapter. ,AMfadhya Pradesh is a south-

yard thrust of the Hindi speaking popilation of the Uttar Pradesh,

It follows the kinship pattern of the north and is therefore not

described here.

‘enced by all these but the influencés of the three zones on it are ng

uniform,/ This lack of uniformity is due to the history of the v:

ous regions within the zone as also to the topography of the zon

‘The northern zone is an alluvium formed by the rivers flowin

from the Himalayas into the Bay of Bengal. The massive barrie

of the Himalayas shuts it off in the north and from west to e

it is a uniform plain without any hills. ‘The only natural barri

are the tributaries of the river Ganga. ‘The central zone on th

other hand is traversed by different mountain systems from no1

to south (the Aravali and the Sahyadri) and from west to e

(the Vindhya and the Satpura) which have cut it up into separate

areas where intercommunication is possible only along certain

routes. The existence of forests and mountains has affected the”

migrations of people from north to south and has also affected the

settlements of the agricultural castes which are the backbone of the

northern, central and southern zones. ‘The semi-desert tract of

western Rajputana adds to the geographical complexity of this

It is not possible therefore to describe the regi

collectively as was done for the north and so afte

of the features of the kinship organization fou!

(1) Rajasthan

Rajasthan is divided into an eastern and a western portion

divided by the Aravali ranges. Western Rajasthan is a semi-desert

country where the peasant population is always on the brink of

famine and where scarcity of water Eastern Raj-

| asthan also suffers from water scarcity but the preserve it

from the sands blowing across the western desert, ‘There are a

few places which are still forested and a few fertile belts where

corn grows. In some favourable spots are beautiful man-made

4 very picturésque land showing some of the most ancient and

|| weathered surfaces on! the earth. It is a tract without much rain

|, cr forest except where it meets the central Indian forests of the

=

=

| lakes which support a considerable population. East or west it is !

a66 KINSHIP ORGANIZATION IN INDIA KINSHIP ORGANIZATION OF THE CENTRAL ZONE «167

‘Vindhyan ranges. ‘The population, whether fighters, merchants o

agriculturists, is ever on the move and has gone to the farthest

to make its fortunes. Most of the ruling hou

in India claim Rajput blood, and there is hardly a province where,

the Marwari trader does not have his shop and every year hung

reds of agriculturists wander out of their waterless tract to seq

work southwards into Gujarat or northwards into the Punjab ang

UP.

‘The major communities in Rajasthan are the Rajput, the J

and the Magwas! Banta. ‘The Jat is an agricultural arte of So

Punjab and Delhi and northern Rajasthan. People of this caste,

practise village exogamy and donot allow marriages of cousins,

‘The various Bania or Vaishya castes generally follow the northem

practices and the rule of four gotras and four jatis. “These have,

"elves Nagas are mentioned. The Nagas ruled around Mathura

and parts of U.P. and central India in the 4th century AD. One

‘of the sub-clans of the Nagas, calling itself Sind seems to have

yuled in some districts of Maharashtra and Andhra from the 10th

fo the 14th century.

‘All the clans have gotras, i., names of the rishis attached to™

them. These gotras do not seem to be of ancient origin, nor do

‘they seem to have a function as regards marriage." They seem to“

pave been borrowed from the Brahmins as so many other castes

have done.

As already pointed out the bansa (line) and the clans or ula are™)

arranged in a hypergamous structure in which the Sun-line is

higher than the Moon-line, which in turn is higher than the Fire-

‘The Serpent-line is lower than both the Sun and the Mo

v

already. lustrated while dealing with the northern zone. 's but what position it holds vis-d-vis the Fire-line is not quite ”

The re the fighters and the ruling caste in Rajasth dear.

They are org: into an elaborate system of hypergamous clang ‘A careful study of the names of the clans reveals that the Rajput |

super-clans called Bansa (Sanskrit —variéa) and gotras. The

rough scheme of this structure is as follows.* onan

ee a

folan® among Rajput clans.

L (2) the descendants of the Moon, (3) those belonging to the Fire)

and (4) those descended from the Naga, i.e., serpents.

‘The Sun-line or the Suryabansi trace their descent from the |

anciont house of Ayodhya in which, Rama, the hero of Ramayana |

was born. ‘The Moon-line of the Chandra-bansa claiming descent

from the moon, trace their ancestry to Shri Krshna or the Pandavas.

‘The families in the Fire-ine are supposed to have arisen out of the

fire of thé sage Vasishtha on the mountain Abu and the

Naga-line claim to be descendents of the famous Naga rulers like

‘Takshaka whose stories are given together with the Pandava story

jn Mahabharata. Each line is divided into numerous clans_and

sub-clans. ‘The major elans ean marry among one another but the |

subselans of one major clan do not intermarry. Thi

ansa has three major clans or Kula

quiet, Kachbawaha, and (C) the Rathod. Th

> The Moon-line, i.e., Chandrabansa is also divided into clans which

_ caste does not represent one homogeneous tribe. It seems to be

Central Asiatic tribes of Seythian origin and

some pastoral tribes of Indian Aryan origin. ‘The hypergamous

ial relationships. One is,

the fact of

being a hero and a ruler. . According to the popular theory the

Suryabansa_gave its daughters to Suryabansa Rajputs only while

it received daughters from the other lines. The Chandrabansa gave

daughters to Suryabansa and received from Agnibansa and

ibansa could give daughters to others but

me.

Nagabansa, while /

could receive from

Saryabansa

+ ¢ Candrabansa

I

{

the giving

(The arrows

daughters)

ladder. ‘This theoretical position is

strictly adhered to in practice inasmuch as one finds ex-

es find

and

hters among different Bonsas. What

it there is always a certain order of

| though ruling houses may give or take daughters occasion:

different clans, the number of clans from w rls are received

in marriage is always greater than those to which one gives

‘The Nagabansa or Serpent

few places, though in me

ws. KINSHIP ORGANIZATION IN INDIA KINSHIP ORGANIZATION OF THE CENTRAL ZONE 169

daughters in marriage, in the case of clans with a high status. The fff jumble origin could not ordinarily aspire to the hand of a girl of

ladder-like structure of the clans also established certain claims as J the highest clan. Such an occurrence led either to feuds or formed

regards marriage. A girl married into a higher family hoped to the theme for romantic songs.

bring another gir] of her pat

as a bride to the heir. The ‘in cases where a bride-price is not

bride’s family jealously guarded this privilege of providing brides i

guarded not merely higher social esteem but also material eains in in-

to a given family and so we have cases of one-way cross-cousin ect ways. Attention was drawn to the part played by the wife's

marriages in each generation as is illustrated in the ruling house prother in Sanskrit literature and among the northern people. The

of Jodhpur where a princess of the Bhati (Bhatti?) fa same role is again seen in Rajput history. A girl married into a

salmer has been given in marriage to a prince of Jodhpur for the t her relatives appointed to different posts,

last few generations. A perusal of the history of the Jodhpur clan wving an infant son, her father’s people be-

shows that a majority of the rulers of this State had a Bhati prin. [come very powerful and sometimes usurp the kingdom. ‘The sala

cess as one of their queens. This relationship is brought out in a } js here too a word of contempt. The dichotomy of relatives between

proverb which says that a_i i one’s own people and the wife's people, the father’s people and the

father’s sister (phat packhal bhatrijt jave). mother’s people is not diminished by the cross-cousin marriage,

cross-cousin marriage is not allowed among Rajputs. _A_w« but is sharpened in many cases because of it and because of the

does not marry her mother’s brother's son. This type Of marriage | status-problem it involves.

is supposed to lower the status of a gi During the early middle ages Rajputs spread all

A sketch has already been given illustrating the ladde are found today in large numbers in all the regions of the nor-

arrangement of the Rajput clans. The actual arrangement is not | thern and central zones. In each region they have taken brides

from local people and are thus considered to_be of mixed origin,

‘with the result that from Rajputana to Bihar the status of Rajput

Girls either marry into families on the same step or into those |} clans, whatever origin (the Sun, Moon or Fire) they may claim,

above them. How far up the social ladder a girl ean | becomes lower and lower the more easterly their rezion. The ‘\_

marry will depend on several things” Extraordinary beauty has | Rajputs of Bihar are lower in status than those of castern U.P., ¢

‘always helped women to go up the social ladder by marriage, but | who in turn are lower than those of western U.P. These oceupy 5

there are limits to this transaction. A man—even aking—could | a humbler position as against the clans in Rajputana who thus)

not raise a woman to this status unless she belonged to certain | stand above all Rajputs in the rest of h

well-recognized groups. He could never, for example, marry an

untouchable and the chances of other humble castes were remote, f ea beta) «

while those of Rajputs were the best. Anthropological literature on India is full of descriptions of

In theory the status of the child is the same as the status of the castes and sub-castes of India and everyone has noted the tendency

father ; in practice the status depends to some extent on the status s. But the reverse process has

of the mother too. A king with many wives has sons who have been going on in India. In such a process new folk-elements

Cee ee)

rom the East, the boy/

different status depending on the status of their mothers. In a | coming as conquerors or new settlers have absorbed original ele-

society where children died in great numbers there was always the | ments and later settlers and welded all into one loose caste group.

‘chance of the son of a woman of low status surviving others and The two most notable examples of such a process are the Rajputs

becoming the ruling prince and thus raising the prestige of his | of Rajasthan and the Marathas of Maharashtra. Both these are

mother’s group. fighting confederacies. As warriors they accepted daughters from

‘The question of status is discussed most expl the conquered group but did not give Thelrs in return. They thus

rature, but actually in a fighting community persoi ety.

sition of territory and legitimacy of birth gave a man enough status ithout cross-cousin

to aspire to the highest honour. Even so, however, a man of | marriage as it does in fact Northern Brahmin

170 KINSHIP ORGANIZATION IN INDIA

castes and among certain Gujarat castes and among Rajputs them.

selves. The cross-cousin marriage by which a man marries hi

mother’s brother's daughter is not a compulsory form of marriage

among Rajputs but it is quite frequent and is mentioned in many.

stories about the ruling houses of Rajasthan, Kathiawad and

Gujarat.

This type of marriage develops a relationship among “certain

families where one family gives daughters and the other receives

‘them. ‘The hypergamy is such that the givers are socially inferior

to the receivers. ‘The deg: inferiority may be so great that |

sometimes the groom does srsonally to the bride's village

for the marriage ceremony but sends hi

sword to represent him,

D. N. MasuMDAR notes that this urge to give daughters tito Migher

so great that among the far

s of the highest status

many girls have to remain spinsters as they cannot find grooms of

their own status without a dowry, Th inthis status groy

generally have more thanone wife. In the. tat yup on

are many bachelors who have to content them-

brother's widow or. who practise virtual poly-

andry.. ‘The marriage of a man to his mamd’s (mother’s brother’

daughter seems to be a result of the impact and subsequent

absorption of the northern people with some southern people, who

already had the practice of cross-cousin marriage. Possibly the

northern conquerors accepted brides from the southern people but

Tefused fo give their daughters in return and so we get the central

is found among

We also find

that throughout the south wherever only one type of eros:-cousin

mother’s i mamd is used also for

father be: term sasré. ‘This new usage of

‘t of a man to his mother’s brother's daughter) exists

i

}

i

KINSHIP ORGANIZATION OF THE CENTRAL ZONE am

the term mamo agrees well with the custom of the marriage of

man to his mother’s brother's daughter. The custom of levirate

Js found among many people of the lower castes. In Gujarat the

word diyar (husband's younger brother) is used as a term of abuse

of an obscene kind, Among almost all castes there is permissi

for a man to marry his wife's younger sister. The elder

‘on the other hand a tabooed relation and among some sections is

called pafld haw i.e. the mother-in-law to whom one gives a seat of

jronour (the pat). Some of the Gujarati terms are similar to the

Marathi terms. The terms for son’s and daughter's father-in-law

and mother-in-law are devahi and vevay (from Sanskrit vai

Zone who marries), and are like the Marathi terms vydhi and

‘sihig. ‘Though Gujarati has different terms for grandfather, the

word aj@ in the expression aj@-padva is the same as Marathi aja.

Instead of the northern word nanihal (the house of the mother’s

father) the Gujarati word is mosal (the house of the mother’s

brother). The word vir is used for brother in Gujarati and Rajas-

thani folk-songs. The expression médi jéyo vir is used for an

own brother. It means a brother born of the same mother.

Gujarat and Maharashtra have many folk-songs and folk-tales in

common, some of them almost identical. ‘The folk-songs and folk-

tales which tell of the mdmd’s house seem not to have been fre-

quent in Gujarat. Maharashtra shares them with Karnatak.

(2) Kathiawad and Gujarat®

‘Towards the south the hills of Rajasthan merge gradually into

s tract of undulating

‘the north Gujarat plail

dunes of yellow sandy loam, Thi

wherevei

its imu

loamy

Kutch by a shallow belt of land which is inundated in the floods

and which has a chain of salt lakes in the dry seasons of the year.

North-eastern Kathiawad is a flat plain and presents an arid ap-

salt-flats. The rest of Kathiawad contains the

mn and black soil of Maharashtra.

Ss coastal

\s a history of pros-

middle ages.

pastoral castes

ral castes. In dress, beat

KINSHIP ORGANIZATION IN INDIA

different from the surrounding population. Ahirs or Ayars are

foun thiawad and the borders of Gujarat, Rabari are found

espe in what was formerly the Baroda State and Bharwad

are found in the northern and central Gujarat, east of the Rabaris.

The Ahirs in historical times used to wander right up to the

borders of Sind. Castes bearing the names of Ahirs and follow.

ing pastoral pursuits are found in Maharashtra, Central India,

Utter Pradesh and Bihar. Ahir is a clan name among Marathas

and Rajputs. Probably they represent a wave of post-Christian

immigration into India of some Central Asiatic pastoral people,

Bharwad too seem to be a purely Gujarat caste. ‘The women of

these castes dress in a fashion which is akin to that of the people

of Rajasthan and consists of a skirt and a bodice with a wrap to

cover the head and shoulders. The other communities of Gujarat

like the Bania and Kanbi (the traders and the agriculturists)

Gress in an entirely different way. All the ruling houses of Kathin-

wad and Gujarat are of Rajput extraction. A small caste called

Kathi have given their name to Kathiawad, its ancient name being

‘Saurashtra. Besides these castes there are Kolis who are spread

throughout Kathiawad and Gujarat and the Dheds who are found

in Gujarat. Both these castes are very widespread in Maharashtra

‘also and very probably represent an old stratum of population in

these regions of the central zuue. ‘The Dhed Vankar are known

as Dhed in northern Maharashtra but their more common name is

Mahar. A glance at the map will show that Bhil are one of the

‘most numerous of the primitive tribes of this zone and have spread

through Rajasthan, Central India, Gujarat and Maharashtra. It

is thus found in four separate linguistic regions.

‘As regards kinship organization Kathiawad and Gujarat show

the northern practices as also the custom of cross-cousin marriage

Se eo

Besides these, Gujarat has certain customs pect

castes. The most important among these is that of periodic mar-

riages. Certain castes like the Bharwad allowed marriages once

a year; certain others, like the Kadva Kanbi, in the recent past

allowed marriages once every four, five, nine or twelve years.

hen the marriage year arrived, it was annotinced from

‘fants in arms got married on such occasions. Pregnant

went through the ceremony of marriage on behalf of the child they

were carrying. If the children of two such women happened to

be of the same sex the marriage was null and void, but if they were

5

KINSHIP ORGANIZATION OF THE CENTRAL ZONE

cof different sex the marriage was binding. Som

Suited pairs like a grown up man and an infant girl or a grown

up woman and an infant boy got married on such occasions. Later

‘on such marriages were dissolyed~and each partner could then

enter into a new alliance called(‘Nantra which did not require the

help of a priest or am jous time."

‘The custom of€virateJby which the widow either lives with or

marries the younger brother of her husband is found among the

jower castes of Gujarat. Folk-tales, proverbs and songs bear

ample testimony to this custom though people get angry at such

fan enquiry. The word bhabhi used for elder brother's wife is a

respectful term in modern times, but it was not so during

medieval times where it was taken as an insulting mode of add-

ress for a respectable woman. A story tells that a woman so

addressed by a king burnt herself and her curse destroyed the

e of the king.* In the stary the term biabhi is contrasted

rms Ben (sister) and md (mother) which are the proper

terms of address by a stranger to an unknown woman, Just as a

‘man must not use the term bhabhi for a woman so also the term

diyar is not used by a woman for a strangar except in abuse.

All over India, in all Ianguages there are songs about an old

man married to a very young girl. Even Rgveda has a fling at

such a match. Gujarat has its own quota of such songs, but be-

sides these it has songs about another sort of an ill-matched pair—

that of a grown up woman and an infant boy. In such songs the

women gathered at the village well are depicted as asking the bride

solicitously if her boy husband was sleeping in his cradle while she

came away to the village well, whether he had enough playthings

and whether he eried too much. When I first heard the songs? I

thought they referred to a social situation arising out of levirate,

whereby a widow passes on as wife to an infant brother of her

dead husband. Further enquiry however showed that such a mar-

riage on many occasions is the first marriage of a woman. I was

told by a reliable informant in Ahmedabad that in such a house-

born of the union are fathered on the little boy. When the boy

comes of age he marries a woman more suited to him, I have not

come across such a family, nor heard a song or a story depicting

the behaviour of kin in such a household. The custom of periodic

marriages is fast dying out and so it would be difficult to find such

Poussholds which, even in old days, must have been rather excep-

ional

v

v

ee

sa wainsyir ORGANIZATION IN INDIA

ja the Brahmins, the Banias, the Kanbis

1 ee Kashi es follow the northerit pattery of kine

snip ore i biit even among these there are certain practices

Seer scan to Tero ouihern origin. One such practice is the

SGuttom of Sending 9 girl ber father’s home for confinement,

esong Anavil Begins of south Gujarat this is an invariable

rule and it is found among ™any other eastes also, ‘The Brahmins

Indl the Banias are aided into innumerable sub-castes which are

soamall that it doce sot Sem possible to stick to the rule of

woe marrying clogs eatins. Enquiry showed that the marriage

Je one’s own patailinuaat Was not allowed but one could marry

2 Sross-cousin remoree bY Wo, preferably by three degrees (i.e,

the erand-children oe tue event erand-children of a brother and a

sistler can marry).

“Phere are however cher castes among whom cross-cousin

mattiage is allowed sad Who use the words mémajt and mamijt

Jax the wife's or freskend® father and mother. Among the Kathi,

the Ali, the Gadhaea c=" (8 minisrel cata) and the Garasia

(a lower type of the Rajput cast

Canto matty he monet’ brother's daughter.

wass told the proverb piitt pachhal bhatriji jave (a

the father’s sister ae pride into a house) both in Kathiawad and

Gujarat.

“The Koli and the Dhed Were the eastes and Bhil, a tribe, most

cut fo assess, Some appeared. to_allow both types of cross-cousin

jnairiage, ie, a man WY marry either the mother’s brother's

daaighter or the ‘tethe’s sister's daughter. Some allowed only the

first type while the ahet® flatly denied the existence of such a

‘stom and told are that they did not allow marriages among any

flood-relations. ‘Some of the Koli songs T heard refer to eross-

cousins as lovers, » Kolis 8F€ found all over the regi

occupations. They sad the Dhed and Bhil tend to imitate the

ial norms of tie Mgbet castes and the educated urbanized sec-

fons among these exto8 pattern their behaviour on that of the

higher castes. Sli bere 18 no doubt at all that these three castes

representing perhaps th!

tise er Pe maria

crrceiuehce aren gadifed in the use they are

H, thie centr

anid southern zones give® each of i

northern languages like Gujarati, Rajasthani, Nimadi and Hi

SHIP ORGANIZATION OF THE CENTRAL 20

variety than is found either in the northern er the south:

Rajasthan and Gujarat illustrate an area in which

castes follow the northern pattern with certain m¢

mother’s brother’s daughter.

origin and some terms, which are non-Sanskrit

Dravidian origin but may be of Central Asiatic der

Maharashtra on the other hand is-an area where

northern traits and the Dravidian southern traits almost hold 2

falance with perhaps a slight predominance for the former.

“Maharashtra, the country where the language spoken is Marathi,

Jies athwart the middle portion of India from the Arabian sea on

the west to the eastern forests and hills near Orissa on the east.

‘To the north of this area, though the languages spoken are ofli

there is a vast belt of broken mountain ranges (the Satpura and.

the Vindhya) and forests which harbour many primitive tribes

south-east, Maharashtra is bounded by plain fertile country and

populous areas where the two Dravidian languages Kannada and

‘Telugu are spoken. Inscriptions and records show that parts of

Maharashtra, Karnatak and Andhra were ruled by the Satavahana

by Chalukya kings for 250 years and by

ilar period as one kingdom or empire.

it was an area of cultural contacts

and this fact is reflected in the social i 's of Maharashtra,

In Maharashtra|the caste structure is a little different from

the southern or the northern Zone. The Marathas and

the Kunbis together form about for

per cent of the population.

‘The Marathas are supposed to be higher in status but a rich Kunbi

can reach the Maratha status as a proverb shows. The two groups

elves Kshatriya. In western Maharashtra all those who

were listed as Kunbi some fifty and twenty-five years ago now call

Maratha. In eastern and northern Maharashtra the

of itself as a fighting and a

eb height:

of most v

isa Maratha, There is no doubt

lated various ethnic strains and that

16 KINSHIP ORGANIZATION IN INDIA KINSHIP ORGANIZATION OF THE CENTRAL ZONE 17

though they go by one name there are various endogamous groups gem to have very little significance in ordinary life but each

within it. In spite of this however this class represents the cul. family worships its ‘Devaka’ at the time of marriage and no two

tural traits of Maharashtra and its practices and family-names are people having the same ‘Devaka’ can marry. Very few people

taken up by most of the lower castes. jgeom to carry the name of the ‘Devaka’ as their family name. ‘The

In northern Maharashtra (the basins of the rivers Tapi, Purna, para is not known to many people; it is however known to the

Vardha and Vainganga) there are many Kunbi castes each sub. xrs who look into these matters at the time of the marriage.

divided into exogamous clans. Some of these admit having the "ihe clans and the Devakas both play a part in marriage. They,

custom of levirate, some have a taboo on cousin marriage, while cle of "Devaka'-exogamy has already been stated. Those clans

some practise cross-cousin marriage. In central Maharashtra which have the same Devaka do not marry. The funetion of the

where the Marathas are the dominant caste, one type of cross. in marriage depends on the status of a clan. ‘The Maratha

clans are arranged in a hypergamous system. All those who are

supposed f0 be true Marathas belong to minety-six clans. The

n by Maratha writers however generally contain

inety-six names. Among these ninety-six there are

tus, ‘The highest ‘are called

~ These are the clans of Jadhav,

, Pawar, ee. The next division is “seven clans”

\des Bhosle and so on.

rule, while in southern Maharashtra there are instances of both

types of cross-cousin marriage, as also of uncle-niece marriage

among some castes.

The clan organization of the Marathas has some similarities

They have not the elaborate mythology

with that of the Rajputs.

but many clans

associated with the 01

logical origin of the Rajputs. Some of the names of the Marathas ‘The rule for marriage is that the five (the central circle p. 178)

are similar to the dynasti ingdoms after the &h can marry among themselves or can marry girls from the other }

century of this era. These Aud:. wr of north Konkan), fans but do not give their daughters to any one outside of the five(

Kadam (Kadamba of south Konkan), Shinde (Sind of Sinnar in dans. The ‘seven-clan’ di can marry among themselves, or

fasik District), Chalake (Chalukya). Against these are. such “can give their daughters to the “five-clan” or receive girls from all )

‘mes as Chavhan, Powar, Salunke which seem to be derived from the rest except “the five-clan” di

. Thus the hypergamous

‘the Rajput clan-names like Chauhan, Parmar, Solanki, ete, There ‘vlan arrangement is like that of the Rajputs and Khatris of north-

Gp some names which are also claimed to be names of ancient India. But the totemistic exogamous Devakas seem to have

dynasties the name Moré which some have derived from analogies only with the southern exogamous groupings described

Maurya, which seems to be a little far-fetched. This name seems fater. The difference between the Rajput arrangement and this

‘o belong to the third type of clan names which are very numer- {s that among the Rajputs the Suryabansa, the Chandrabansa, ete.,

ous. ‘These are names of animals, qualities or artefacts. Thus are exclusive of each other, while here each inner circle i

‘here are clans called Vagh (the tiger), Moré (the peacock), Kal- tontained in the larger circle. The five-clan are part of the

bhor (the black), Panghre (the white), Kudale (the picl n-clan and of the 96-clan. Not so the Bansa, except that they

Kurhage (the axe) etc. ‘There are many clan-names besides these. long to the samo Rajput caste. ‘They can be represented

‘There does not seem always to be any totemistic connection bet sually on a ladder but not as concentric circles. Like the Ttaiputs

‘ween the clan and the animal name it bears, though it is reported Marathas seem to be made up of various ethnic elements some

‘that sometimes the flesh of the animal is not eaten by the clan ring themselves to be higher in status than the others

which bears the name. ke the castes in the northern zone most of the communities

‘The rule of exogamy is however not dependent on the clan-name Maharashtra have no marriage taboo based on bilateral kinship,

but on the symbol connected with the clan. This symbol the own brothers and sisters, a person must .~

vaka’, Devaka may be any maternal cousin or the parallel paternal

apis — a kind of grass, Katyar — a In northern and central Maharashtra there is also a taboo

leaves of five particular trees, are some is

180 LINSHIP ORGANIZATION IN INDIA KINSHIP ORGANIZATION OF THE CENTRAL ZONE, 181

x]

ern times men seemed to care more for money than for status or

aimetimes in central Maharashtra and more frequently in south

faharashtra a man may marry his father’s sister’s daughter but

such occasions some expiatory rite is always performed at the

ime of marriage. On one such occasion a mingture replica of a

ne was made in gold, passed over the heads of (he groom and the

jde and given away to the officiating priest. \is was supposed

fo avert any evil resulting from such a marriage.

‘Exchange of girls as brides between two fajpilies is frowned

spon by all who have any pretention to status., It is taken as a. L-

“Gon of exiveme poverty In Maharaahies many’ Brahms wast

Yollow the same pattern as the non-Brahmins. All Brahmins

possess Gotras and a man, provided he marries;outside his gotra)

and pravara group, can marry his blood-relation on the mother’s

side, preferably the daughter of the mother’s brofher. They do not |

‘There is a belief among all Marathi-speaking people includi

even those who do not posses:

father’s sister's daughter some

Paecn nasa! a2 ‘is gi

eeper (a climbing vine) must not return.’

‘ho el given toa family aoa brides the creeper oF vine. Trg

daughter comes back as a bride into her father’s family, there {

if the creeper which is contrary to nature. The vi

regulate their marriage according to the consanguinity ‘taboos of

the north but on a system of clan exogamy where gotra takes the

fanetion of the clan. Such a cross-cousin marriage (a man

marrying his mother’s brother's daughter or a woman marrying

hr father’s sister's son) is or was upto recently the preferred type

‘of marriage among the Saraswat, the Karhada aud the Degastha

‘Revedi Brahmin castes of Maharashtra. :

‘The Chitpavan caste followed the gotra and pravara, rules and ?

did not allow marriage among people related within five genera-) ~

tions from the mother and seven from the father, Hovtever there

have been stray cases of cross-cousin martiage even among the

Chitpavans where a legal fiction was resorted to, to make the mar-

riage conform to the usual type. If the boy A is a cross-cousin

(father’s sister's son) of the girl B and a marriage is arranged,

then B is given in adoption to a man G who is in no way related

sither to the family of A or of B. By adoption then B becomes

tho daughter of a family who is not related consanguinally to A

and so can become his bride. In some recent marriages even this

expedient was not felt to be necessary.

‘The Madhyandina caste of Brahmins not only practises the usual

tile of gotra and pravara but insist that the pravara of the bride’s

nama must be different from the groom's mamd, ie., the groom's

maternal uncle. This eustom is analogous to thé northern rule of

come back. We have thus givers and receivers of girls even am

people who theoretically belong to the same status. Among

who are of the same atatus ultimately the circle of giving

closed by C or D or E giving daughters to A. We have thus.

iple of indirect exchange. But very often it leads to soci

to remain unmarried for failing to find a groom of equal status of

must marry below their grade and become members of a lower so:

cial group. In such marriages the married girl loses the usual,

contact with her parents’ home and is not treated as an honoured’!

guest.

‘These customs i

take money for a girl when she is given in marriage. Ifa man

marries his mother’s brother’s daughter the amount of money p:

to the bride's father is always smaller than when a man mai

an outsider. We may thus say that money moves in the direction |

‘opposite to the direction in which brides are given. Actually ho

ever in the higher Maratha society the custom of dowry

found and a man will marry a girl of a slightly lower status if she

brought a substantial dowry, so that the movement of money andl] four gotras whereby the bride’s a

brides is all in one direction. ‘The author has heard bitter com!§)) also belong to different f

plaints from high-born impoverished parents of girls that in moMft Tng to the mother’s gotra is not found among other Brahmin castes

182 KINSHIP ORGANIZATION IN INDIA

of Maharashtra. Researches show that very probably the Maay

~ yandina Brahmins are a later immigration into Maharashtra f

the northern zone

‘The Gujars in Khandesh (north-west Maharashtra) do not allo

cross-cousin matriage and follow northern customs. Recently!

however after much debating in the caste couneil permission

granted for one such marriage. One of the caste elders

“When all around you, other castes are indulging in such marriage

you cannot prevent it happening in one isolated caste. One canng

live in the sea and not get wet.”

"The difference in the marriage customs in different parts of Ml

‘Maharashtra and the very gradual spread of cross-cousin marriage

among most castes illustrate the process of cultural exchanges and |

cultural adjustments ang. the slow tempo of such changes in the

loosely knit caste society of India. This process can be studied,

assessed and mapped for a region in all the aspects of culture

like dress, utensils, social organization and language and makes a

very fascinating study in a culture-contact region like

rashtra, A glimpse at the linguistic aspect of this process

obtained when we deal with the kinship terminology in the Marat

language.

‘Thus we see that the preferred type of marriage in Maharasht

is that of a man with his mother's brother's daughter. It is fo

among the majority of castes: ‘The other type of the eross-cous

yimarriage in which a man marries his father’s sisver’s daughter

\not tolerated. It is supposed to result in misfortune and some ex-

iatory rites need to be performed when it does take place. ‘The

endogamous castes, other than the Marathas, do not possess @ pr

nounced hypergamous structure and do not give hypergamy as

reason for following such a practice; but the fact that Marathas

do possess such a system, and that they also form an influential

majority in the region seems to indicate that such a marriage and

the accompanying taboo against the other type of cross-cousin mar- |

riage rest on feelings of superiority and inferiority arising from |

such a system.

‘The Maratha system of exogamous clans, each with its totemic

symbol, have analogies only with the clan system of the southern

and may have been derived from them, the conquerin:

Je forming the higher groups while the conquered people a

a lower status. (The immigrants estal

a ruling class accepted daughters from the indigenous pop’

without however deigning to give theirs in return, thus for

| fer back to her husband’s house.

KINSHIP ORGANIZATION OF THE CENTRAL ZONE, 188

he system of cross-cousin marriage found in Maharashtra today.)

fhe custom of receiving daughters as far as possible from one

family and thus establishing certain rights and duties of sexual

{ehaviour is also a usual southern custom and it is possible that

fhe women brought as brides established this custom by bringing

Gaughters-in-law from their paternal family.

nthe family in Maharashtra is patrilineal and patrilocal but it

is toms unknown in north India, but which are found

in the south, In the north a bride comes back after

ceremony and lives with her parents till the gauna

ceremony.

father’s home only very occasionally for ceremonial _In

Maharashtra after the marriage a bride moves to and from her

father's house quite frequently before and after reaching puberty.

It is customary for a girl to come and stay with her parents during

her first pregnancy and delivery. A girl and her people are put

to great shame if she has no parental home to go to for her first

delivery. This misfortune forms the theme of a number of foll:-

es. Among most people a woman comes and lives. with her

parents for each pregnancy and delivery the

fas necessary as at the time of the first delivery. Each big feast-

day brings back the married wor

2 girl comes to her father’s hous:

ie husband's people who come

to fetch her are sent back again and again until the gifts they bring

ultimately satisfy the parents or the fear of the disapprobation of

the community, or a costly law suit makes them send back the bride

to her husband. In fact this type of conduct has resulted in al-

‘most 2 norm of social behaviour. A girl comes away or runs away

very often from the husband’s house, goes back reluctantly, only

to return in a few week's time. A woman settles contente’

her husband’s house only after she has given birth to a few

ren, though the slightest excuse sends her with her children on a

visit to the parents’ house. This behaviour of the bride is en-

couraged by-her parents, sometimes from motives of ext

sents from the boy’s parents. Except among the v

bride-price and if a man f

the wife and the bride-pri

to retain his wife he may lose both

The quarrels of the two parties and

form a considerable number of cases in the

rashtra.!?

184 KINSHIP ORGANIZATION IN INDIA

Curiously this behaviour of the wives is at variance with the.

usual norm for wifehood, but reflects the stresses and strains of @

region where two cultures have met. At least for India it seems

as if the phenomenon of preference for one type of marriage (that

of a man to his mother’s brother’s daughter) is due to culture con,

tact resulti the establishment of hypergamous caste groups,

It is found among the Rajputs and Marathas who have clans which,

are composed of different ethnic elements and which live in contact

with the southern regions which practise cross-cousin marriage,

The southern influence is more marked in the Maratha regi

than in Rajasthan and Kathiawad. The language is northern, i.e,

Sanskritic in origin but the structure of the kinship terms reveals

southern influences. Some kinship terms are literary and are used

by Brahmins and are purely Sanskritie, ‘There are others, more

colloquial and equally respectable, used both by Brahmins and non.

Brahmins, which can be explained and understood by reference to

the southern systems. ‘The Marathi language has a larger kinship

vocabulary than any other language either in the north or the south,

because of the double nomenclature for certain relations.

In the north the words for brother's wife are bhaujt or bhabhi

(elder brother's wife) and for husband’s sister nanad. In Marathi

‘the Sanskritie terms corresponding to the above are bhdvajaya and

nayand, ‘The term for elder brother's wife is vahint which, how.

ever, is used al brother’s When a man or

a. woman says 5 my vakint”, it is understood that

he refers to his elder brother's wife. If the reference is to a

younger brother’s wife one must say dhakti vahint, i.e, younger

‘vakini. The other word for nanand is vanse or vainse used as a

term of address or also as a term of reference.

‘The words vahini and vainse are really the same words, with the

difference that a added to the word vahint to

turn it i ble ‘sa’ is quite

common in some regions of Maharashtra today and was apparently

more wide-spread in the 18th and 14th century as appears from

literary records of those centuries. Thus the word bap (father)

is often written as bapus in older literature and spoken at present

as bapus on the west coast. The words a (mother), béi (a-wo-

man) are also written as Gisd, baisd in old Marathi. “Sa” denotes

respect. Vahhini and vainse are the same words except that to show

respect to a relation of the husband the syllable sa is added when

talking to or about the husband’s sister. Vahini thus means both

“husband's sister” and “brother's It is thus a term of mu-

the fer

KINSHIP ORGANIZATION OF THE CENTRAL ZONE, 185

1 address by two women standing in either relation to each

‘er. Such terms are found in the Dravidian languages and this

je shows that Marathi has borrowed the mode from the south.

purely Sanskritic words bhavajaya and nayanda are never

way. Nor are the Marathi people aware that vahint

vf wo words vadhi (Sanskrit) + anni (elder brother's wife! —

‘g later Dravidian word formed on the analogy of Sanskrit feminine

words from the original annd—elder brother). “A woman who

isa vadhi (a bride) of the house being the elder brother's wife”

"jg thus the meaning of the word. Such a term cannot be applied

py two women to each other, u

change of girls between two fa

ss there was the custom of ex-

Such exchanges occur but

"rarely in Maharashtra.

In Marathi there are the usual Sanskritic words for the father-

inlaw and mother-in-law. The

these, other words mama or mamajé for father-i

‘or mavalana for mother-in-law are also in common use. The words

d and mimi are the usual words for the mother’s brother and

These words are applicable only for a man's parents-

inlaw inasmuch as he marries the maternal uncle's daughter but

‘they are in general use and are employed even among castes who

taboo strictly any kind of cousin-marriage. In Marathi the word

4tyé is used for the father’s sister and it is used also for husband's.

mother among the Marathas. The usage is suggestive of the actual

practice. The other word for atyd, which is also frequently used

is mavalaya which does not conform to marriage-practices at all.

The word mavalana is derived from the Sanskrit word matulani,

‘ine of the Sanskrit word

there is no custom of exchange marriage, the father’s sister can-

not really become the mother’s brother's wife and yet the word

‘mévalaya suggests such a usage.

186 KINSHIP ORGANIZATION IN INDIA

A and q are a brother and a sister who have married } and B, an

ther sister and brother. The son D of the man B and the woman,

has A for his maternal uncle and the woman b for his paterna]

aunt. But as b is the wife of A, she is to D (1) his father's sister

as also (2) the wife of the mother’s brother.

‘This type of marriage is frowned upon in Maharashtra and 59

the kinship terms are not conformable with the actual usage.

‘The third set of double terms refer to the cross-cousin;

conformity with the northorn languages and northern rage the

Marathi people use the words mame-bhaw, and mime-bahin, for

iren of the mother’s brother, i.

‘the brother and sister through Im the same way

the children of the father’s sister are te-bhaw and ate.

brother and sister through dte, ‘The other set of terms

as is used for these relatives among many Marathas and Kunbis

is: mehund and mekuni. ‘These are reciprocal terms and the rela.

tion between the children of a brother and a sister is said to be

that of mehume. ‘The words mekund, mehuni and mehwne are of

Sanskritic origin. ‘The Sanskrit word maithuna or maithunaka

becomes mehuna or mehunaga in Prakrt and mehupa or mehuné

in Marathi. The Sanskrit word mithuna is riot a kinship word

atall. It means ‘a pair’ and is used for any pair of the same sex or of

different sexes. In Mahabharata the twin brothers Nakula and

Sahadeva are called mithuna many times. The word is however

of birds, beasts, semi-divine

beings or human

without any kinshi

connotation for a married pair. ‘Thus, on

auspicious days it is customary to invite a meliina (ie, a mar-

ried couple) of the Brahmin caste for a meal, Thus the

word is not used for any pair, but for a human marrled couple

only. ‘The word mehiina is neuter. The word mehiiné and mehuni

on the other hand are masculine and feminine respe

have only a kinship connotation. ‘The words are appli

cross-cousins or to wife’s brother and

a pair”, and is a new word coined to meet a new social situation

unknown to north India, ie., that of cross-cousin marriage. * The

northern usage equates all cousins to brothers and sisters.

Marathi retains the northern terms but has two extra terms to

denote the new relationship.

In the same way the fourth pair of words are those used for

the wife's brother and sister. ‘The words sala and sdji are like

the mama. These terms —

the word meliiya is used .

KINSHIP ORGANIZATION OF THE CENTRAL ZONE 187

northern sala and sdfi derived from the old Sanskrit word syila

‘and syalikd. The other pair of words are mekund and mehuri

which we have already discussed above. The custom of using the

same words for cross-cousins and wife’s brothers and sisters seems

+40 be derived from the Dravidian south.

Some other peculiarities and modifications of the Marathi ter-

jology may now be discussed. The Marathi word for father

is bapa or bapu or baba which seems to be derived from the west-

em bappé and bépu and is not found in the Sanskrit literature.

‘The word for mother is di and those for grandfather and grand-

mother are dj@ and @ji, All these words are derived from the

Sanskrit word drya or aryaka. Arya becomes ayya and ajja in

Pali and Ardhamagadhi respectively. From the Prakrt ajja-a

(Gryaka) we have Marathi dja and ji the Marathi feminine form.

From ayya we would have a masculine form aya which is missing,

but we have the feminine dyt or ai for mother.

‘The words éja and 4jt seem originally to have stood for mother’s

father and mother’s mother. The father's father and mother even

now are called among many castes mhétara or- thorié b& and

mbatéri di which means the old or older father and mother. The

word ajo is used in Marathi always for a person's. mother's

father’s house. Ajo] in Sanskrit, would be rendered as arya (ajja)

+ kula (ula), ic., the family of the arya. One's father’s house is

one’s own and so needs no separate designation. Mother's parents

being respected affinal relations would, according to Sanskrit

usage, be called arya and their house is drya-kula. Now however,

the words aja and dji are used for grand-parents on both sides,

‘The parents’ great-grand-pai

panji. Panga is a-degree above of ni-pania is

a negative and the Khdpar of khépar-ponja means a potsherd as

symbol of something inauspicious. In Maharashtra it is sup-

posed to be inauspicious for a man to live long enough to see the

face of his great-great-grandson. The same sentiment is reflected

words for grandson, great-grandson and great-great-grand-

hich are nétt (Sanskrit naptr), parti: (Sanskrit pra-nap!

K-pantit or khépar-panti. i

imary kinship in the fath

With the Exo

the middle, close kinship in the father’

counted upto and including three ascending generations and three

descending generations. ‘This conception however is not elabo-

rated in kinship usage or ritual except on the occasion of offering

188, KINSHIP ORGANIZATION IN INDIA

Nipanja (great-great-grandfather)

Pays (great-grandfather)

ial grandtather)

Baph (father)

1

The Ego

I

Pat (son)

i

Nat (grandson)

I

Panatii (great-grandson)

Ni-panatii (great-great-grandson)

food to the ancestors. A man offers food to his father, grand.

father and great-grandfather by mentioning these relations by the

kinship terms and then he gives an omnibus offering for all those

who may be above these. This usage found in Sanskrit literature

may have found an expression in this type of terminology.

‘The word for father's brother is cwlata derived from Prakrt

culla + téo (the younger father) and must stand for father’s

younger brother. It is however used both for the elder and younger

brothers of the father. ‘The word kaka is also similarly used. The

words thorld bd and dhdkla ba (elder and younger father) are

also used sometimes.

The words mama, mami, Gtyé and mavalana are already dis-

|. Among some castes no one'word exists for atya’s husband,

some give the word mémé or mévald. Mother's sister is

‘méusi, the same word as northern mdusi. It is also used for

‘A man can and does many times marry

proverb ai meli ki

is but the ma

ries the younger sister of the mother.

‘The words for brother and sister are similar to those in the

North—bhdw and bhahin. ‘The Marathi people however use &

lot of nicknames for elder and younger brother and elder and

younger sister like dada, aynd, ndna,bapi, babi for brothers and

Dravidian custom of nomenclature which is discussed later,

‘The cousins are either called bhau and bakin or a distinction is

are called mehune. This has already been

ve. For relatives of the generation below one’s own,

in the northern zone as we have seen, there are terms for (i) own

son and daughter (puo-dhi), (ii) brother’s son and daughter

(Dhatija-bheija sister's son and daughter (bhanja-bhanjt),

(iv) husband's brother's son and daughter (jefhut, derut, jethuti,

deroti), (v) busband’s sister’s children (nandut ete.), (vi) wife's

brother's and sister's children (salut ete.). ‘The terms enumerated

under (i), (ii) and (iii) are the same whether the speaker is a

‘man or ian.

In Maharashtra one does not have so many terms and the type

of terms changes according as the speaker is a man or a

‘woman. For own son and daughter the terms are piit or lyok or

‘imulagé or mulagi. The same terms are used when a woman speaks

of her sister's children. ‘The words putenyd-putani are used when

a man speaks of his brother's children or a woman speaks of her

Ausband’s brother's children, When a man speaks of his sister's

children the words are bhded-bhaci." This system is a sort of a

compromise between the southern and northern systems. In a

purely classificatory system one would have expected only two

pairs of terms for

(a) children of the same sexed sibling, own children, hus-

band’s brother's children and wife's sister’s children,

and

(b) the children of the different sexed

ther's children and husband’s sister's

ing, wife's bro-

idren,

Marathi has not the northern system but has only certain ele.

ments of the southern system. It is thus a compromise system of

nomenclature for these relations.

For husband and wife there are various terms mostly of Sans-

Krit derivation and analogous to the northern terms. We have

already discussed the terms for spouse's parents, husband's sister

and wife’s brother. The terms for husband's brother are of inte-

190 KINSHIP ORGANIZATION IN INDIA

rest. In old Marathi literature there were two terms Dhdvd for

husband’s elder brother and dira for husband's younger brother,

The term bhava is used as bhdvasdend also and is analogous to

the northern term bhdsur. It is retained in the modern term

dhavoji. This term is used among Brahmins for husband’s elder ,

or younger brother. Among agriculturists it is used for that rela."

tion, as also for wife's elder brother or elder sister's husband, In

modern time the only word of reference is dira which means hus.

band’s brother generally. To the own name of the person some.

times the title bhavoji is attached (e.g. Laxman-bhdvoji). There

‘are no separate words for husband's elder brother's wife and

younger brother’s wife. They are both referred to as jéii and

called bai. Actually one does not directly address any of the people

of the husband's house if they are older than oneself. The younger

relatives may be addressed as vanse, bhdujt or Yamundbat ete, |

but that too rarely. Levirate is not allowed in most of Mahara.

shtra and with the disappearance of that custom the distinction

between husband's elder and younger brother and elder brother's

and younger brother's wife (both of whom are called vahint and

referred to as bhévajaya) has vanished in Maharashtra. Also,

instead of separate terms for husband’s elder brother’s son and

husband’s younger brother's son like jefhut and derut, we have

only one word gutanya and for daughter putani in Marathi.

‘The words sald and sali are used for wife’s brother and sister

respectively. For the younger relatives the terms mehund and

‘mehupi are also used for this pair. ‘The word mehunacér is used

relationship and possible marriage relationship between

es. The terms mehund-mehuni (but not sald-salt) are

an old term which has now gone out of general use but which

still used in parts of Berar, viz., akkad-sdsit. Tt is a term parallel

‘A woman must behave as towards a father-in-law

nd’s elder brother; he is her bhdva-sisra (bhava =

. In the same way a man's beha-

viour to his wife’s elder sister is very circumspect. She is an akka

(a Dravidian word meaning elder sister) who is at the same time

like a eds (mother-in-law). In older Marathi there is a word

bhatu or bhafwa. It is also found in a folk-song of eastern Mah:

stern Mal

der brother,

word among

‘a word in the

rashtra, This word is used in Berar and Nagpu

jong Gonds, anid refers to wi

" in-law’s house) are terms used oftenest hy women.

KINSHIP ORGANIZATION OF THE CENTRAL ZONE 191

th either and cannot derive it from any Sanskrit word except

artZ (husband, master). ‘The word for wife's sister’s husband

je similar to the northern word namely sddu or sddbhau. For

for's wife the Marathi word lerived from Sanskrit snus

;d in this respect there is similarity to the Sindhi and Panjabi

ww is javal a

son-in-law and daughter

vyahi (masculine) and vikiya (emine) derived from the

Genskrit word vivaha (marriage) and mean those connected by

marriage. In its connotation it is analogous to the words samdki

‘and samdhin of the north..

Like the north Maharashtra has a set of terms for parents’ house

and husband's house. Maher (mother’s house) and sasar (father-

Analogous to

the word nanihdl, Marathi has the word @jola. Women in their

parents’ house are called makervasin, those in their husband's

house are called sdsurvdsiz. The behaviour pattern for the two

are different, the differences being the same as noted for the north.

For people with whom one is related, as people of the pat

there is the word saga, which is contrasted with the kin by marriage

for which the word is soyard. ‘The plural term sage-soyare stands

for the whole kinship group. The word sagd is derived from the

Sanskrit word svaka (one’s own). The word soyaré seems to b

derived from the word svasuraka'* (belonging to the father

law). We have seen that the word svasura becomes sai

many northern languages. Sahura-d becomes saura-d and soyaré

in Marathi. In the Marathi expression sage-soyare we have again

the northern classification of kinship by blood and marriage

Whereno Bajastnan (oopepaliy the western part) presents to

the eye a dry region, eternally si from scarcity of water

with its bare granite hills fantas weathered by the action

2000-2500 feet and then there is an upland plate

smaller hills raise their heads, green in the north ai

in the south where the primitive tribes are doing int

192 KINSHIP ORGANIZATION IN INDIA

KINSHIP ORGANIZATION OF THE CENTRAL ZONE 193

culture and sowing niger (Verbesina sativa) seeds almost to the

tops of the hills. The many hills, the rapidly flowing and deep

rivers and many smaller streams have cut up the hilly area into

smaller regions and inter-communication between them is rather

ficult. The western Orissa hinterland of

joined to a fertile strip of coast-land where rice is gr

grown almost upto the western border of the province along the

river valleys in the north by the Kulta, Binzal, Chasa, Khandayat

and in the south by the Bhatra, Besides these agricultural castes

almost all the primitive and somi-primitive tribes grow rice or

cash crops like niger seed. In the whole of the jungle area there

are well-organized periodic markets called hét where men and

women of primitive tribes and agricultural castes come to sell the

produce of their fields and forests and buy sal loth, agricul.

tural implements, ete. 7

‘The Gonds, Uraons and the Kondhs speak Dravidian languages

and their kinship system can be best described along with that of

the Dravidian-speaking people. (Ch. Vand VI)

‘The Munda, the Bondo and some of the Saora speaking Mundari

languages and their kinship pattern is dealt with later in a sepa

rate chapter. (Ch, VII)

"The remaining group speaking Uria show the same type of caste

divieions as are found in the northern region with slightly different

‘The Brahmins seem to be immis fiom Uttar

pland forests for pasturage and do quite a considerable trading

jn cattle. They know the primitive tribes much more intimately

than any other people. Some anthropologists have depicted them

‘as the exploiters of the primitives and the e

jfe. It is a wrong picture to draw of this des

the social borders of two communities. A more objective study

needed for the understanding of the role of these people in an

‘area where so many separate ethnic elements live together. ‘The

‘coastal Pana themselves deny the practice of eross-cousin marriage,

{he highland Pana sometimes admitted the custom. It seems that

such a marriage is sometimes allowed but not preferred.

Junior Tevirate is found among all poorer classes. ‘The Brah- \ ~

mins, Karans and Khandayats do not allow such practices, but a

‘more detailed study of families and folk-literature might reveal the

‘existence of the custom among some at least of the higher castes.

Like all northern terminologies Uria has separate terms for dif-

ferent uncles and aunts. Their children are called brothers and

ssisters through uncles and aunts. A distinction is made between

‘husband’s elder and younger brother, the elder is called dedsur and

0 equated to the father-in-law and the younger is referred to by the

sual term diyor or deur. In the same way a distinction is made

‘between the elder brother's wife and the younger brother's wife.

‘A woman does not speak or shuw hier face to the husband’s elder

brother, while she can cut the most obscene jokes with the hus-

band’s younger brother. A man can speak and joke with his elder

brother's wife but must not do so with the younger brother's wife.

Wife's elder sister is called ded-sasu and one must not speak with

her. One can joke with the younger sister sali and also marry her.

‘The kinship terms are given in the Table. ‘They are like Bengali

kinship terms. The term go is used sometimes as a term of ad-

dress for husband or wife. In Bengali there is a similar term ogo.

‘ther of these terms is of Sanskrit origin. In Marathi the word

90 or ago is used for calling the wife and the word gho or ghowd is

used on the west-coast of Maharashtra for husband. Whether all

‘these terms originate from one source I do not know."*

“Flage Femulations are like those of the

“The Avanyaka Brahmins found mostly

.sa are supposed sometimes to allow the marriage of a man

to his mother’s brother's daughter but I found no actual ease of

such a marriage.

‘Among other castes, eg, the Karans, who are the same as the

/ Kayasthas of the north, cousin marriage i owed.

~ “Among the agricultural castes some allow cross-cousin marriage,

while others do not. The coastal castes do not allow such a mar-

riage especially in the region north of Lake Chilka. On the other

hand most of the upland agricultural castes like the Binzal and the

‘To sum up, we find that in the central zone :

Kathiawad and Gujarat is region where only

languages are spoken though there are some non-

words in daily speech. The kinship pattern is

predominantly northern, though a few customs have simi-

castes. They buy cattle in

194 KINSHIP ORGANIZATION IN INDIA

larities with southern customs. Some groups practise o

type of cross-cousin marriage as a permissive form of mays

riage, ie, the marriage of a man to his mother’s brother's

daughter.

‘The hypergamy and one type of cross-cousin marriage seem

to be two aspects of one and the same social relationship aris

ing out of amalgamation of different ethnic elements through:

successive incursions and conquests. :

Maharashtra is a region where the overwhelming majority 9

speak a Sanskritic language. ‘There are however semis

ive people in the east, who speak Dravidian languages

Ge, Gondi and Kolami). The Marathi language has also

a considerable number of words of Dravidian

vocabulary since the earliest times. The major’

and tribes practise one type of cross-cousin marriage. Tn

central and northern Maharashtra there is a definite taboo on

the other type of marriage, though it occurs in south Maha

rashtra, In north Maharashtra junior levirate is all

among many castes. In central and south Maharashtra

not allowed. ‘The Marathas, the most numerous of the Mah

rashtra castes, show a hypergamous clan structure. It is

region most affected by southern practices and its ki

behaviour, kinship terms, folk-songs and literature all shot

that it is a region of cultural borrowings and cultural

synthesis.

More than one-fourth of the population of Orissa

population. Languages belonging to three major linguist

families in India are spoken in this region but as the regi

is cut up by rivers, hills and forests there is not evolved such

homogeneous ulture as in Maharashtra. Still all

ethnic groups are affected by one another and copy each other's

practices. ‘The Uriya-speaking groups generally show

northern pattern though many agriculturists allow cross- |

cousin marriage of one type only.

(2)

@)

‘though differing in its various areas, has

wstes practise one type

‘Thus the central zone,

one thing in common, viz., that many of

of cross-cousin marriage and have a definite taboo or aversion to

wards the other type of cross-cousin marriage. It forms in ‘many

ways a region of transition from the north to the south.

© Oza on the other hand shows

D putana,—Rajputina Ka Itihdea—, Ve

they are alittle younger than

| ae whole regions comprising of many vi

KINSHIP ORGANIZATION OF THE CENTRAL ZONE 195

REFERENCES

10 a region about which not much is

18 an area under the control of Indian

we there, though some excellent articles

© 2 For details of these clans and mythologies connected with them refer to

tiguitice

quitice of Rajasthan—JawEs Toso, and the Hindi book with

tory of Reajastana—GAURISHANKAR HIRACKAND OZA.

history differ as regards the function and antiquity

‘Mr. C.'V. Vatbya in hie book The History of

‘(Oriental Book Agency, Poons-2), arzuet

Bie. GAURISHARICAR

a haphazard fashion

vin Gotras (The History of Raj-

I, pp. 247-865, second Edition 1937,

‘at the Gotras are an ancient

fand have mo fanction analogous to

‘Ajmer)-

‘Caste Handbook for Indian Army,

Government of India Press, 1918, Caleuti

rites of Bonday Presidency, Vo .

+ According to Indian asrologeal practices there are certain pends of 8

ine whith tre tanned for marriage This So caled Stasi,

‘other which comes after very tweve sears which pti

for marvlages and is called’ Kenplgstar Dust the, Your before

Sinastha people try to rush oultanding marriages. And in the Kenvapst

year orthodox people try to perform the marriage of thelr deaghtors oie i

auspicious for marriages, Only fp

Geieat he Tene rns ve ees which hve eso riage

Sore an attempt fs made t pair in marriage every cngle emma

‘dual of whatever age. a es es

* Lea a

, pe 180; edi. py CHMAGANLAL VisvAnAnt Raval,

jarati Sabha, 1929. ug Gaee

faratha” ie used to denote persops

castes of Maharashtra. Tn" Saha:

ve aha denon este

as been ome controversy about the Shinde clan. ‘The wor

om. rngula) and Shinde (oom plural) ae someines aed tne

hildren and thelr progeny. Almost every caste has an infesior

‘npendage of such a subgroup called Lakivie or Shinde. The name Shinde

therefore does In many cases denote such an origin. "On the ater hone thane

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

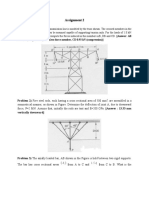

- Assignment 5Document2 pagesAssignment 5harsh gargNo ratings yet

- ME685 Homework3Document16 pagesME685 Homework3harsh gargNo ratings yet

- Energy 17Document15 pagesEnergy 17harsh gargNo ratings yet

- Me659a FCHDocument2 pagesMe659a FCHharsh gargNo ratings yet

- Quiz 4 SolutionsDocument8 pagesQuiz 4 Solutionsharsh gargNo ratings yet

- End Sem Y17Document7 pagesEnd Sem Y17harsh gargNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document2 pagesAssignment 2harsh gargNo ratings yet

- Gotra. 01Document7 pagesGotra. 01harsh gargNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 6Document8 pagesTutorial 6harsh gargNo ratings yet

- ESO 202 Course OutlineDocument2 pagesESO 202 Course Outlineharsh gargNo ratings yet

- Slides Combustion Set 6Document34 pagesSlides Combustion Set 6harsh gargNo ratings yet

- Screw Jack NoteDocument3 pagesScrew Jack Noteharsh gargNo ratings yet