Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Haddle V Garrison

Haddle V Garrison

Uploaded by

Mỹ Anh TrầnCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- NGIG Study Book Element 1 151122Document70 pagesNGIG Study Book Element 1 151122haroonraja579No ratings yet

- Law of Torts 2018 Sem 1Document62 pagesLaw of Torts 2018 Sem 1naveen kumarNo ratings yet

- 1 Mitsubishi CaseDocument2 pages1 Mitsubishi CaseAngela Louise SabaoanNo ratings yet

- Torts MapDocument11 pagesTorts MapWade LeesNo ratings yet

- 5 Paguia vs. Office of The President PDFDocument2 pages5 Paguia vs. Office of The President PDFGD BaltazarNo ratings yet

- Palm v. IledanDocument3 pagesPalm v. Iledanjulieanne07100% (1)

- Richardson v. Belcher, 404 U.S. 78 (1971)Document15 pagesRichardson v. Belcher, 404 U.S. 78 (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Morrell Watchman, 749 F.2d 616, 10th Cir. (1984)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Morrell Watchman, 749 F.2d 616, 10th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chuck C. Johnson v. Gawker: Opposition To anti-SLAPP (Do-Over)Document17 pagesChuck C. Johnson v. Gawker: Opposition To anti-SLAPP (Do-Over)Adam SteinbaughNo ratings yet

- John Scott Wedemeyer v. Pneudraulics, Inc., 11th Cir. (2013)Document8 pagesJohn Scott Wedemeyer v. Pneudraulics, Inc., 11th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- (G.R. No. 176278) Paguia vs. Office of The PresidentDocument2 pages(G.R. No. 176278) Paguia vs. Office of The PresidentRyan LeocarioNo ratings yet

- Palm-v-Iledan DigestDocument2 pagesPalm-v-Iledan DigestRolando Mauring ReubalNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument5 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Tort Final SummaryDocument5 pagesTort Final Summarysiwasna deoNo ratings yet

- CPC Solved PapersDocument31 pagesCPC Solved PapersAnil KumarNo ratings yet

- CASE DIGEST Quiao V Quiao GR 176556Document1 pageCASE DIGEST Quiao V Quiao GR 176556Nuj OtadidNo ratings yet

- US Vs ReyesDocument15 pagesUS Vs ReyesManelle Paula GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Olmeda v. Ortiz-Quinones, 434 F.3d 62, 1st Cir. (2006)Document7 pagesOlmeda v. Ortiz-Quinones, 434 F.3d 62, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Canon 21 Case DigestDocument6 pagesCanon 21 Case DigestDonna Grace Guyo100% (1)

- Octavio Jimenez-Nieves v. United States of America, 682 F.2d 1, 1st Cir. (1982)Document9 pagesOctavio Jimenez-Nieves v. United States of America, 682 F.2d 1, 1st Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Sample Motion2QuashDocument7 pagesSample Motion2QuashTodd Wetzelberger100% (2)

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- No. 91-4084, 974 F.2d 1345, 10th Cir. (1992)Document5 pagesNo. 91-4084, 974 F.2d 1345, 10th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Eugene Dupree v. United States, 264 F.2d 140, 3rd Cir. (1959)Document7 pagesEugene Dupree v. United States, 264 F.2d 140, 3rd Cir. (1959)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Bankr. L. Rep. P 72,478 Howard W. Jones, Trustee in Bankruptcy For James Steven Boyd, Teresa Irene Boyd v. Kelly Harrell, 858 F.2d 667, 11th Cir. (1988)Document5 pagesBankr. L. Rep. P 72,478 Howard W. Jones, Trustee in Bankruptcy For James Steven Boyd, Teresa Irene Boyd v. Kelly Harrell, 858 F.2d 667, 11th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wideman v. Watson, 10th Cir. (2015)Document8 pagesWideman v. Watson, 10th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Legeth Cases 1Document158 pagesLegeth Cases 1RenceNo ratings yet

- Galicto v. Aquino DIGESTDocument2 pagesGalicto v. Aquino DIGESTPolo Martinez100% (2)

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Maggie Bell Heathcoat, As Administratrix For The Estate of Leonard James Heathcoat, Deceased v. Karl Potts, Kenneth Rhoden, Clyde Snoddy, 905 F.2d 367, 11th Cir. (1990)Document8 pagesMaggie Bell Heathcoat, As Administratrix For The Estate of Leonard James Heathcoat, Deceased v. Karl Potts, Kenneth Rhoden, Clyde Snoddy, 905 F.2d 367, 11th Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 729, Dockets 85-7619, 85-7821Document6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 729, Dockets 85-7619, 85-7821Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- (CRIMLAW) People vs. MarreroDocument1 page(CRIMLAW) People vs. MarreroAquino, JPNo ratings yet

- Canon 18 and JurisprudenceDocument5 pagesCanon 18 and JurisprudenceMelissa AdajarNo ratings yet

- 26 - Prof. Loanzon - Special Integration Lecture in The Bill of The Rights July 2023Document52 pages26 - Prof. Loanzon - Special Integration Lecture in The Bill of The Rights July 2023additional.memoryv.4.0No ratings yet

- Cases Feb 19Document20 pagesCases Feb 19Carty MarianoNo ratings yet

- 35.private Hospitals v. MedialdeaDocument2 pages35.private Hospitals v. MedialdeaFretzie Cata-al0% (1)

- Frank Durant v. David Husband Government of The Virgin Islands Contant Restaurant Association, Inc., D/B/A Old Mill and Sugars Night Club, Government of The Virgin Islands, 28 F.3d 12, 3rd Cir. (1994)Document7 pagesFrank Durant v. David Husband Government of The Virgin Islands Contant Restaurant Association, Inc., D/B/A Old Mill and Sugars Night Club, Government of The Virgin Islands, 28 F.3d 12, 3rd Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cortez v. Costes (AC 9119 12 March 2018)Document2 pagesCortez v. Costes (AC 9119 12 March 2018)Yaj GnuoyNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dennis Fitzgerald v. Codex Corporation, 882 F.2d 586, 1st Cir. (1989)Document6 pagesDennis Fitzgerald v. Codex Corporation, 882 F.2d 586, 1st Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- A. Aims of The Law of Tort: 1. N F L TDocument7 pagesA. Aims of The Law of Tort: 1. N F L TGaurav RaneNo ratings yet

- 18 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 1395, 18 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 8775 Douglas E. Cottrell v. Newspaper Agency Corporation, A Utah Corporation, 590 F.2d 836, 10th Cir. (1979)Document6 pages18 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 1395, 18 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 8775 Douglas E. Cottrell v. Newspaper Agency Corporation, A Utah Corporation, 590 F.2d 836, 10th Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument11 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gulf Life Insurance Company, A Florida Corporation v. Carl J. Arnold, An Individual Residing in The State of Tennessee, 809 F.2d 1520, 11th Cir. (1987)Document7 pagesGulf Life Insurance Company, A Florida Corporation v. Carl J. Arnold, An Individual Residing in The State of Tennessee, 809 F.2d 1520, 11th Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, First CircuitDocument15 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, First CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cristino Vs CADocument11 pagesCristino Vs CAQuennie Jane SaplagioNo ratings yet

- Harold H. N. Youngken v. United States, 407 F.2d 836, 3rd Cir. (1969)Document3 pagesHarold H. N. Youngken v. United States, 407 F.2d 836, 3rd Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- John Siy Lim v. Carmelito MontanoDocument1 pageJohn Siy Lim v. Carmelito Montanogoma21100% (1)

- Course Name: Family Law I Course Code: L-CT-0010 Programme: Bba. Llb/Ba LLB/LLB Session: Spring 2021 Maximum Marks: 50Document16 pagesCourse Name: Family Law I Course Code: L-CT-0010 Programme: Bba. Llb/Ba LLB/LLB Session: Spring 2021 Maximum Marks: 50Academic BunnyNo ratings yet

- Gerlach v. Rokita, No 23-1792 (7th Cir. Mar. 6, 2024)Document12 pagesGerlach v. Rokita, No 23-1792 (7th Cir. Mar. 6, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Lim VS MontanoDocument1 pageLim VS MontanoTrixie Jane NeriNo ratings yet

- Rights of The Accused: Estrada v. Desierto (2001) Dumlao v. Comelec, 95 SCRA 392Document2 pagesRights of The Accused: Estrada v. Desierto (2001) Dumlao v. Comelec, 95 SCRA 392hanzky22No ratings yet

- Palm v. Atty. IledanDocument2 pagesPalm v. Atty. IledanCelidonio RemorozaNo ratings yet

- Reply2Opp RedactedDocument27 pagesReply2Opp Redactedhimself2462No ratings yet

- G.R. No. 79253 - United States of America v. ReyesDocument18 pagesG.R. No. 79253 - United States of America v. ReyesBluebells33No ratings yet

- Garcia vs. Drilon Case DigestDocument2 pagesGarcia vs. Drilon Case DigestGilbert John LacorteNo ratings yet

- Bing Tugas UasDocument122 pagesBing Tugas UasjasmineNo ratings yet

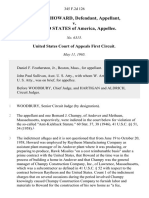

- Robert E. Howard v. United States, 345 F.2d 126, 1st Cir. (1965)Document5 pagesRobert E. Howard v. United States, 345 F.2d 126, 1st Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fifth CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fifth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Buck Doe, and Robert Doe Tays Doe Otis Doe Thomas Doe Joe Doe Charles Doe Dick Doe v. Elaine L. Chao, Secretary of Labor, 435 F.3d 492, 4th Cir. (2006)Document24 pagesBuck Doe, and Robert Doe Tays Doe Otis Doe Thomas Doe Joe Doe Charles Doe Dick Doe v. Elaine L. Chao, Secretary of Labor, 435 F.3d 492, 4th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- General Principles of Tortious LiabilityDocument7 pagesGeneral Principles of Tortious LiabilityIshan MitraNo ratings yet

- California Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandCalifornia Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Bias V Advantage International, Inc.Document2 pagesBias V Advantage International, Inc.Mỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Ashcroft V IqbalDocument3 pagesAshcroft V IqbalMỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Batson V KentuckyDocument2 pagesBatson V KentuckyMỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Fuentes Vs ShevinDocument2 pagesFuentes Vs ShevinMỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Hawkins VDocument3 pagesHawkins VMỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Goldberg VDocument2 pagesGoldberg VMỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Hamdi v. RumsfeldDocument3 pagesHamdi v. RumsfeldMỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Gideon v. WainwrightDocument2 pagesGideon v. WainwrightMỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Family Law NotesDocument20 pagesFamily Law Notessheila moraaNo ratings yet

- An Invitation To Public To Subscribe To Company's CapitalDocument44 pagesAn Invitation To Public To Subscribe To Company's CapitalRishabhJainNo ratings yet

- Joyce Berry v. United of Omaha, 719 F.2d 1127, 11th Cir. (1983)Document4 pagesJoyce Berry v. United of Omaha, 719 F.2d 1127, 11th Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 The Law On Obligations and ContractsDocument7 pagesChapter 1 The Law On Obligations and ContractsShekinah SolimanNo ratings yet

- Calalas Vs Court of Appeals 332 SCRA 356 May 31 2000 PDFDocument6 pagesCalalas Vs Court of Appeals 332 SCRA 356 May 31 2000 PDFBrenda de la GenteNo ratings yet

- Respondent Moot MemorialDocument12 pagesRespondent Moot MemorialKshitij Kashyap100% (2)

- Ielts Writing Task 2 Samples Over 45 High Quality Model Essays For Your Reference To Gain A High Band Score 8.0+ in 1 Week (Rachel Mitchell (Mitchell, Rachel) )Document69 pagesIelts Writing Task 2 Samples Over 45 High Quality Model Essays For Your Reference To Gain A High Band Score 8.0+ in 1 Week (Rachel Mitchell (Mitchell, Rachel) )Mari RamosNo ratings yet

- Adams v. Haw. Med. Service Ass'n, No. SCWC-15-396 (Haw. Sep. 30, 3019)Document25 pagesAdams v. Haw. Med. Service Ass'n, No. SCWC-15-396 (Haw. Sep. 30, 3019)RHTNo ratings yet

- Ratanlal Dhirajlal Tort LawDocument230 pagesRatanlal Dhirajlal Tort LawsamriddhiNo ratings yet

- Tort Claims For Bullying, Harassment and Stress at WorkDocument39 pagesTort Claims For Bullying, Harassment and Stress at WorkclaireNo ratings yet

- Full Download Book Business Law Text and Cases PDFDocument41 pagesFull Download Book Business Law Text and Cases PDFwilliam.manning289100% (31)

- Dynamic Business Law 4th Edition Kubasek Test Bank DownloadDocument94 pagesDynamic Business Law 4th Edition Kubasek Test Bank DownloadEmily Edwards100% (21)

- Legal Methods Ii by Mwakisiki Mwakisiki-1 PDFDocument72 pagesLegal Methods Ii by Mwakisiki Mwakisiki-1 PDFMy3No ratings yet

- Pacis v. MoralesDocument12 pagesPacis v. MoralesAnjan RosarioNo ratings yet

- Business Law AppendixDocument28 pagesBusiness Law AppendixBara DanielNo ratings yet

- 33-Spouses Viloria v. Continental Airlines, Inc. G.R. No. 188288 January 16, 2012Document14 pages33-Spouses Viloria v. Continental Airlines, Inc. G.R. No. 188288 January 16, 2012Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- Command Line Tools License AgreementDocument7 pagesCommand Line Tools License AgreementMatt NNo ratings yet

- Job - RFQ-017 - Video DocumentaryDocument25 pagesJob - RFQ-017 - Video DocumentaryFaizanSulNo ratings yet

- Torts Midterms Reviewer Final PDFDocument9 pagesTorts Midterms Reviewer Final PDFDarla GreyNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Topics in Law in IndiaDocument8 pagesDissertation Topics in Law in IndiaCustomHandwritingPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Jurisdictional Issues in Internet DisputesDocument35 pagesJurisdictional Issues in Internet DisputesTalwant Singh100% (1)

- Halotech Business PlanDocument72 pagesHalotech Business PlanRob WesterlundNo ratings yet

- Health LawDocument72 pagesHealth Lawrichaconch2007100% (1)

- Schmidt V Driscoll HotelDocument1 pageSchmidt V Driscoll HotelMary Ann LeuterioNo ratings yet

- Restatements (2 & 3) of AgencyDocument15 pagesRestatements (2 & 3) of AgencyTaylor Ruffa100% (3)

- Acurite Atlas™: Instruction ManualDocument8 pagesAcurite Atlas™: Instruction Manualkeyshapower powerNo ratings yet

- Jenks SuitDocument25 pagesJenks SuitShorebeatNo ratings yet

Haddle V Garrison

Haddle V Garrison

Uploaded by

Mỹ Anh TrầnOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Haddle V Garrison

Haddle V Garrison

Uploaded by

Mỹ Anh TrầnCopyright:

Available Formats

Haddle v.

Garrison

Facts: Haddle worked for Healthmaster Home Health Care as an at-will employee.

He filed a case against his former employer and Garrison (defendant), a

Healthmaster officer, alleging that he was illegally fired to avoid his participation

in a criminal proceeding as a witness. The defendants filed a motion to dismiss the

plaintiff's claim for failure to provide a basis for relief. The court decided that the

statute under which he sought relief, 42 U.S.C. 1985(2), prohibited remedies for an

at-will employee, and granted the defendant's motion to dismiss. Haddle filed an

appeal with the court of appeals, which upheld the decision of the lower court. The

United States Supreme Court granted certiorari.

Issue: The question, in this case, was whether the Civil Rights claim under Section

1985 (2) requires a violation of a constitutionally protected property right to apply.

Rule: The heart of the offense addressed by 42 U.S.C.S. 1985(2) is not the loss of

property, but rather the intimidation or retaliation of witnesses in federal court

proceedings. The word "damaged in his person or property" expresses the harm

that a victim may experience as a result of an intimidation or retaliation plot.

Therefore, the fact that employment at will is not considered "property" for the

purposes of the Due Process Clause does not indicate that the loss of employment

at will cannot cause harm to the petitioner's person or property under 42 U.S.C.S.

1985. (2).

Application: This answer to the question of this case is no.

It is not essential that a constitutionally protected property right or interest be

violated in order to file a Section 1985 claim under the Civil Rights Act (2). The

clause indicates that it is a crime for one or more individuals to conspire to hinder,

intimidate, or threaten another individual from attending and testifying during a

federal court trial. The Eleventh Circuit was of the conclusion that Haddle (P) had

suffered no harm since he had lost no compensable property interest as a result of

the termination of his at-will employment. This interpretation cannot be

incorporated into the relevant section or its corrective measures. Instead of material

damage, this provision addresses intimidation and retaliation against witnesses. In

this scenario, such conduct is permissible since, under tort law, the loss of

employment at-will is a compensable damage, much like breach of contract.

Consequently, Haddle's claim should not have been rejected on the basis that he

failed to establish a claim. Case was remanded after the judgement was overturned.

Conclusion: Under 42 U.S.C. 1985, the kind of harm described by the petitioner,

essentially third-party interference with at-will employment relationships, created a

cause for remedy. (2). Despite the fact that his employment contract was at-will, he

held extensive contract rights. The fact that employment at will is not considered

"property" for purposes of the Due Process Clause does not entail that the loss of

employment at will cannot "injure [petitioner] in his person or property" for

purposes of section 1985. (2). This kind of loss has been and is a compensable

injury under tort law, and there is no reason to depart from this precedent in this

instance. Insofar as the expression "damaged in his person or property"

corresponds to such tort principles, there is substantial support for the Court's

ruling.

Synthesis: The word "employment-at-will" is unclear, and at the time of this case,

just a handful of Supreme Court cases had addressed this problem. In this action,

the National Whistleblowers Association provided amicus, or unrequested

testimony and legal advice. The Supreme Court's decision to overturn this verdict

may have led to an increase in comparable federal court cases.

You might also like

- NGIG Study Book Element 1 151122Document70 pagesNGIG Study Book Element 1 151122haroonraja579No ratings yet

- Law of Torts 2018 Sem 1Document62 pagesLaw of Torts 2018 Sem 1naveen kumarNo ratings yet

- 1 Mitsubishi CaseDocument2 pages1 Mitsubishi CaseAngela Louise SabaoanNo ratings yet

- Torts MapDocument11 pagesTorts MapWade LeesNo ratings yet

- 5 Paguia vs. Office of The President PDFDocument2 pages5 Paguia vs. Office of The President PDFGD BaltazarNo ratings yet

- Palm v. IledanDocument3 pagesPalm v. Iledanjulieanne07100% (1)

- Richardson v. Belcher, 404 U.S. 78 (1971)Document15 pagesRichardson v. Belcher, 404 U.S. 78 (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Morrell Watchman, 749 F.2d 616, 10th Cir. (1984)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Morrell Watchman, 749 F.2d 616, 10th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chuck C. Johnson v. Gawker: Opposition To anti-SLAPP (Do-Over)Document17 pagesChuck C. Johnson v. Gawker: Opposition To anti-SLAPP (Do-Over)Adam SteinbaughNo ratings yet

- John Scott Wedemeyer v. Pneudraulics, Inc., 11th Cir. (2013)Document8 pagesJohn Scott Wedemeyer v. Pneudraulics, Inc., 11th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- (G.R. No. 176278) Paguia vs. Office of The PresidentDocument2 pages(G.R. No. 176278) Paguia vs. Office of The PresidentRyan LeocarioNo ratings yet

- Palm-v-Iledan DigestDocument2 pagesPalm-v-Iledan DigestRolando Mauring ReubalNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument5 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Tort Final SummaryDocument5 pagesTort Final Summarysiwasna deoNo ratings yet

- CPC Solved PapersDocument31 pagesCPC Solved PapersAnil KumarNo ratings yet

- CASE DIGEST Quiao V Quiao GR 176556Document1 pageCASE DIGEST Quiao V Quiao GR 176556Nuj OtadidNo ratings yet

- US Vs ReyesDocument15 pagesUS Vs ReyesManelle Paula GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Olmeda v. Ortiz-Quinones, 434 F.3d 62, 1st Cir. (2006)Document7 pagesOlmeda v. Ortiz-Quinones, 434 F.3d 62, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Canon 21 Case DigestDocument6 pagesCanon 21 Case DigestDonna Grace Guyo100% (1)

- Octavio Jimenez-Nieves v. United States of America, 682 F.2d 1, 1st Cir. (1982)Document9 pagesOctavio Jimenez-Nieves v. United States of America, 682 F.2d 1, 1st Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Sample Motion2QuashDocument7 pagesSample Motion2QuashTodd Wetzelberger100% (2)

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- No. 91-4084, 974 F.2d 1345, 10th Cir. (1992)Document5 pagesNo. 91-4084, 974 F.2d 1345, 10th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Eugene Dupree v. United States, 264 F.2d 140, 3rd Cir. (1959)Document7 pagesEugene Dupree v. United States, 264 F.2d 140, 3rd Cir. (1959)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Bankr. L. Rep. P 72,478 Howard W. Jones, Trustee in Bankruptcy For James Steven Boyd, Teresa Irene Boyd v. Kelly Harrell, 858 F.2d 667, 11th Cir. (1988)Document5 pagesBankr. L. Rep. P 72,478 Howard W. Jones, Trustee in Bankruptcy For James Steven Boyd, Teresa Irene Boyd v. Kelly Harrell, 858 F.2d 667, 11th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wideman v. Watson, 10th Cir. (2015)Document8 pagesWideman v. Watson, 10th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Legeth Cases 1Document158 pagesLegeth Cases 1RenceNo ratings yet

- Galicto v. Aquino DIGESTDocument2 pagesGalicto v. Aquino DIGESTPolo Martinez100% (2)

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Maggie Bell Heathcoat, As Administratrix For The Estate of Leonard James Heathcoat, Deceased v. Karl Potts, Kenneth Rhoden, Clyde Snoddy, 905 F.2d 367, 11th Cir. (1990)Document8 pagesMaggie Bell Heathcoat, As Administratrix For The Estate of Leonard James Heathcoat, Deceased v. Karl Potts, Kenneth Rhoden, Clyde Snoddy, 905 F.2d 367, 11th Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 729, Dockets 85-7619, 85-7821Document6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 729, Dockets 85-7619, 85-7821Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- (CRIMLAW) People vs. MarreroDocument1 page(CRIMLAW) People vs. MarreroAquino, JPNo ratings yet

- Canon 18 and JurisprudenceDocument5 pagesCanon 18 and JurisprudenceMelissa AdajarNo ratings yet

- 26 - Prof. Loanzon - Special Integration Lecture in The Bill of The Rights July 2023Document52 pages26 - Prof. Loanzon - Special Integration Lecture in The Bill of The Rights July 2023additional.memoryv.4.0No ratings yet

- Cases Feb 19Document20 pagesCases Feb 19Carty MarianoNo ratings yet

- 35.private Hospitals v. MedialdeaDocument2 pages35.private Hospitals v. MedialdeaFretzie Cata-al0% (1)

- Frank Durant v. David Husband Government of The Virgin Islands Contant Restaurant Association, Inc., D/B/A Old Mill and Sugars Night Club, Government of The Virgin Islands, 28 F.3d 12, 3rd Cir. (1994)Document7 pagesFrank Durant v. David Husband Government of The Virgin Islands Contant Restaurant Association, Inc., D/B/A Old Mill and Sugars Night Club, Government of The Virgin Islands, 28 F.3d 12, 3rd Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cortez v. Costes (AC 9119 12 March 2018)Document2 pagesCortez v. Costes (AC 9119 12 March 2018)Yaj GnuoyNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dennis Fitzgerald v. Codex Corporation, 882 F.2d 586, 1st Cir. (1989)Document6 pagesDennis Fitzgerald v. Codex Corporation, 882 F.2d 586, 1st Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- A. Aims of The Law of Tort: 1. N F L TDocument7 pagesA. Aims of The Law of Tort: 1. N F L TGaurav RaneNo ratings yet

- 18 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 1395, 18 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 8775 Douglas E. Cottrell v. Newspaper Agency Corporation, A Utah Corporation, 590 F.2d 836, 10th Cir. (1979)Document6 pages18 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 1395, 18 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 8775 Douglas E. Cottrell v. Newspaper Agency Corporation, A Utah Corporation, 590 F.2d 836, 10th Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument11 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gulf Life Insurance Company, A Florida Corporation v. Carl J. Arnold, An Individual Residing in The State of Tennessee, 809 F.2d 1520, 11th Cir. (1987)Document7 pagesGulf Life Insurance Company, A Florida Corporation v. Carl J. Arnold, An Individual Residing in The State of Tennessee, 809 F.2d 1520, 11th Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, First CircuitDocument15 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, First CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cristino Vs CADocument11 pagesCristino Vs CAQuennie Jane SaplagioNo ratings yet

- Harold H. N. Youngken v. United States, 407 F.2d 836, 3rd Cir. (1969)Document3 pagesHarold H. N. Youngken v. United States, 407 F.2d 836, 3rd Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- John Siy Lim v. Carmelito MontanoDocument1 pageJohn Siy Lim v. Carmelito Montanogoma21100% (1)

- Course Name: Family Law I Course Code: L-CT-0010 Programme: Bba. Llb/Ba LLB/LLB Session: Spring 2021 Maximum Marks: 50Document16 pagesCourse Name: Family Law I Course Code: L-CT-0010 Programme: Bba. Llb/Ba LLB/LLB Session: Spring 2021 Maximum Marks: 50Academic BunnyNo ratings yet

- Gerlach v. Rokita, No 23-1792 (7th Cir. Mar. 6, 2024)Document12 pagesGerlach v. Rokita, No 23-1792 (7th Cir. Mar. 6, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Lim VS MontanoDocument1 pageLim VS MontanoTrixie Jane NeriNo ratings yet

- Rights of The Accused: Estrada v. Desierto (2001) Dumlao v. Comelec, 95 SCRA 392Document2 pagesRights of The Accused: Estrada v. Desierto (2001) Dumlao v. Comelec, 95 SCRA 392hanzky22No ratings yet

- Palm v. Atty. IledanDocument2 pagesPalm v. Atty. IledanCelidonio RemorozaNo ratings yet

- Reply2Opp RedactedDocument27 pagesReply2Opp Redactedhimself2462No ratings yet

- G.R. No. 79253 - United States of America v. ReyesDocument18 pagesG.R. No. 79253 - United States of America v. ReyesBluebells33No ratings yet

- Garcia vs. Drilon Case DigestDocument2 pagesGarcia vs. Drilon Case DigestGilbert John LacorteNo ratings yet

- Bing Tugas UasDocument122 pagesBing Tugas UasjasmineNo ratings yet

- Robert E. Howard v. United States, 345 F.2d 126, 1st Cir. (1965)Document5 pagesRobert E. Howard v. United States, 345 F.2d 126, 1st Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fifth CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fifth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Buck Doe, and Robert Doe Tays Doe Otis Doe Thomas Doe Joe Doe Charles Doe Dick Doe v. Elaine L. Chao, Secretary of Labor, 435 F.3d 492, 4th Cir. (2006)Document24 pagesBuck Doe, and Robert Doe Tays Doe Otis Doe Thomas Doe Joe Doe Charles Doe Dick Doe v. Elaine L. Chao, Secretary of Labor, 435 F.3d 492, 4th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- General Principles of Tortious LiabilityDocument7 pagesGeneral Principles of Tortious LiabilityIshan MitraNo ratings yet

- California Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandCalifornia Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Bias V Advantage International, Inc.Document2 pagesBias V Advantage International, Inc.Mỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Ashcroft V IqbalDocument3 pagesAshcroft V IqbalMỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Batson V KentuckyDocument2 pagesBatson V KentuckyMỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Fuentes Vs ShevinDocument2 pagesFuentes Vs ShevinMỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Hawkins VDocument3 pagesHawkins VMỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Goldberg VDocument2 pagesGoldberg VMỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Hamdi v. RumsfeldDocument3 pagesHamdi v. RumsfeldMỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Gideon v. WainwrightDocument2 pagesGideon v. WainwrightMỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Family Law NotesDocument20 pagesFamily Law Notessheila moraaNo ratings yet

- An Invitation To Public To Subscribe To Company's CapitalDocument44 pagesAn Invitation To Public To Subscribe To Company's CapitalRishabhJainNo ratings yet

- Joyce Berry v. United of Omaha, 719 F.2d 1127, 11th Cir. (1983)Document4 pagesJoyce Berry v. United of Omaha, 719 F.2d 1127, 11th Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 The Law On Obligations and ContractsDocument7 pagesChapter 1 The Law On Obligations and ContractsShekinah SolimanNo ratings yet

- Calalas Vs Court of Appeals 332 SCRA 356 May 31 2000 PDFDocument6 pagesCalalas Vs Court of Appeals 332 SCRA 356 May 31 2000 PDFBrenda de la GenteNo ratings yet

- Respondent Moot MemorialDocument12 pagesRespondent Moot MemorialKshitij Kashyap100% (2)

- Ielts Writing Task 2 Samples Over 45 High Quality Model Essays For Your Reference To Gain A High Band Score 8.0+ in 1 Week (Rachel Mitchell (Mitchell, Rachel) )Document69 pagesIelts Writing Task 2 Samples Over 45 High Quality Model Essays For Your Reference To Gain A High Band Score 8.0+ in 1 Week (Rachel Mitchell (Mitchell, Rachel) )Mari RamosNo ratings yet

- Adams v. Haw. Med. Service Ass'n, No. SCWC-15-396 (Haw. Sep. 30, 3019)Document25 pagesAdams v. Haw. Med. Service Ass'n, No. SCWC-15-396 (Haw. Sep. 30, 3019)RHTNo ratings yet

- Ratanlal Dhirajlal Tort LawDocument230 pagesRatanlal Dhirajlal Tort LawsamriddhiNo ratings yet

- Tort Claims For Bullying, Harassment and Stress at WorkDocument39 pagesTort Claims For Bullying, Harassment and Stress at WorkclaireNo ratings yet

- Full Download Book Business Law Text and Cases PDFDocument41 pagesFull Download Book Business Law Text and Cases PDFwilliam.manning289100% (31)

- Dynamic Business Law 4th Edition Kubasek Test Bank DownloadDocument94 pagesDynamic Business Law 4th Edition Kubasek Test Bank DownloadEmily Edwards100% (21)

- Legal Methods Ii by Mwakisiki Mwakisiki-1 PDFDocument72 pagesLegal Methods Ii by Mwakisiki Mwakisiki-1 PDFMy3No ratings yet

- Pacis v. MoralesDocument12 pagesPacis v. MoralesAnjan RosarioNo ratings yet

- Business Law AppendixDocument28 pagesBusiness Law AppendixBara DanielNo ratings yet

- 33-Spouses Viloria v. Continental Airlines, Inc. G.R. No. 188288 January 16, 2012Document14 pages33-Spouses Viloria v. Continental Airlines, Inc. G.R. No. 188288 January 16, 2012Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- Command Line Tools License AgreementDocument7 pagesCommand Line Tools License AgreementMatt NNo ratings yet

- Job - RFQ-017 - Video DocumentaryDocument25 pagesJob - RFQ-017 - Video DocumentaryFaizanSulNo ratings yet

- Torts Midterms Reviewer Final PDFDocument9 pagesTorts Midterms Reviewer Final PDFDarla GreyNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Topics in Law in IndiaDocument8 pagesDissertation Topics in Law in IndiaCustomHandwritingPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Jurisdictional Issues in Internet DisputesDocument35 pagesJurisdictional Issues in Internet DisputesTalwant Singh100% (1)

- Halotech Business PlanDocument72 pagesHalotech Business PlanRob WesterlundNo ratings yet

- Health LawDocument72 pagesHealth Lawrichaconch2007100% (1)

- Schmidt V Driscoll HotelDocument1 pageSchmidt V Driscoll HotelMary Ann LeuterioNo ratings yet

- Restatements (2 & 3) of AgencyDocument15 pagesRestatements (2 & 3) of AgencyTaylor Ruffa100% (3)

- Acurite Atlas™: Instruction ManualDocument8 pagesAcurite Atlas™: Instruction Manualkeyshapower powerNo ratings yet

- Jenks SuitDocument25 pagesJenks SuitShorebeatNo ratings yet